Active Machine Learning for Organic Reaction Optimization: Strategies, Applications, and Future Directions

This article provides a comprehensive overview of active machine learning (ML) for optimizing organic reaction conditions, a critical task in pharmaceutical development and fine chemical engineering.

Active Machine Learning for Organic Reaction Optimization: Strategies, Applications, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of active machine learning (ML) for optimizing organic reaction conditions, a critical task in pharmaceutical development and fine chemical engineering. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of active learning, which iteratively selects the most informative experiments to minimize costly data generation. The piece delves into core methodologies like Bayesian optimization and transfer learning, illustrating their application in self-driving laboratories and high-throughput experimentation. It further addresses persistent challenges such as data scarcity and molecular representation, while presenting validation case studies that demonstrate significant acceleration in identifying optimal conditions for reactions like Suzuki and Buchwald-Hartwig couplings, ultimately outlining future implications for biomedical research.

The Core Principles and Pressing Challenges of Reaction Optimization

The Scale of the Challenge in Organic Chemistry

The fundamental challenge in modern organic chemistry is navigating an almost infinite experimental space with traditional, resource-intensive methods. The convergence of laboratory automation and artificial intelligence is creating unprecedented opportunities for accelerating chemical discovery, yet it also generates data at a scale that surpasses human processing capacity [1].

The core of the problem lies in the fact that the outcome of a chemical reaction depends on a large and complex combination of factors, including catalysts, solvents, substrate concentrations, and temperature [2]. Conventional optimization strategies, such as the "one factor at a time" (OFAT) approach, are simplistic and often fail to identify optimal conditions because they ignore complex interactions between experimental parameters [2]. This inefficiency is compounded by the sheer volume of data modern laboratories produce; for instance, high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) laboratories can accumulate terabytes of recorded information over just a few years, within which many new chemical products remain undiscovered [3].

Table 1: Quantifying the Data and Experimental Scale in Chemical Research

| Aspect of Scale | Quantitative Measure | Implication for Research |

|---|---|---|

| Mass Spectrometry Data | >8 TB from 22,000 spectra [3] | Vast amounts of unexplored experimental data already exist, containing undiscovered reactions. |

| Commercial Reaction Databases | Up to 150 million reactions (e.g., SciFinderⁿ) [2] | Manual extraction of generalizable knowledge is impractical. |

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) | Single datasets containing 4,608+ reactions (e.g., Buchwald-Hartwig) [2] | Generates more data points than can be efficiently analyzed with traditional methods. |

| Reaction Condition Parameters | A large, complex combination (catalyst, solvent, concentration, temperature, etc.) [2] | Creates a multidimensional search space too vast for empirical exploration. |

Active Machine Learning as a Strategic Solution

Active machine learning (ML) has emerged as a powerful strategy to navigate this vast space efficiently. This approach uses algorithms to autonomously design, execute, and analyze experiments, dramatically increasing the speed and efficiency of chemical optimization [1]. A key differentiator of active learning is its data efficiency; tools like LabMate.ML can optimize organic synthesis conditions beginning with only 5-10 initial data points [4]. The algorithm then suggests new experimental protocols, incorporates the results, and iteratively improves its suggestions, often finding suitable conditions in just 1-10 additional experiments [4].

Two primary model types are employed to tackle different parts of the problem:

- Global Models: These exploit information from comprehensive databases (e.g., Reaxys, Open Reaction Database) to suggest general reaction conditions for a wide range of reaction types. They require large and diverse datasets for training [2].

- Local Models: These focus on a single reaction family and are typically used with HTE data to fine-tune specific parameters (e.g., substrate concentrations, additives) for yield optimization, often using methods like Bayesian optimization [2].

Table 2: Machine Learning Model Typologies for Reaction Optimization

| Model Type | Data Scope & Sources | Primary Function | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Model | Broad; millions of reactions from literature and patents [2]. | Recommend general conditions for new reactions in Computer-Aided Synthesis Planning (CASP). | Wide applicability across diverse chemistry. |

| Local Model | Narrow; reaction-specific datasets from High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) [2]. | Fine-tune specific parameters (e.g., concentrations, additives) to maximize yield/selectivity. | High precision for optimizing specific reactions; includes data on failed experiments. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing an Active Learning Workflow for Reaction Optimization

Application Note: This protocol describes the procedure for implementing an active machine learning cycle to optimize a catalytic organic reaction, such as a Buchwald-Hartwig amination, using a tool like LabMate.ML [4].

Materials:

- Reaction starting materials (aryl halide, amine)

- Candidate reagents: Palladium catalysts, ligands, bases, solvents

- Automated liquid handling system or equipment for parallel reaction setup

- Analytical instrument (e.g., UPLC, GC) for yield determination

- Computer with active ML software (e.g.,

LabMate.ML)

Procedure:

- Initial Dataset Generation (Initial Design):

- Use an automated platform to set up and run a small, diverse set of initial reactions (e.g., 5-10). Diversity should be achieved by varying key parameters such as catalyst, ligand, base, and solvent from a pre-defined list of candidates [2] [4].

- Quench the reactions after a set time and analyze the crude reaction mixtures to determine reaction yield for each condition.

Model Training and Prediction (Active Learning Cycle):

- Input the experimental results (conditions and corresponding yields) into the active ML platform.

- Execute the algorithm, which uses a model (e.g., Random Forest) to quantify the importance of different parameters and predict a set of promising, unexplored reaction conditions [4].

Experimental Validation (Iteration):

- Synthesize the top candidate condition(s) suggested by the model in the laboratory.

- Determine the yield of the reaction(s) and feed the result (both success and failure) back into the algorithm.

Convergence and Analysis:

- Repeat steps 2 and 3 until a predefined performance threshold is met (e.g., yield >90%) or the performance plateaus.

- Analyze the final model to extract insights into parameter importance, which may reveal novel, non-intuitive relationships between reaction parameters and outcomes [4].

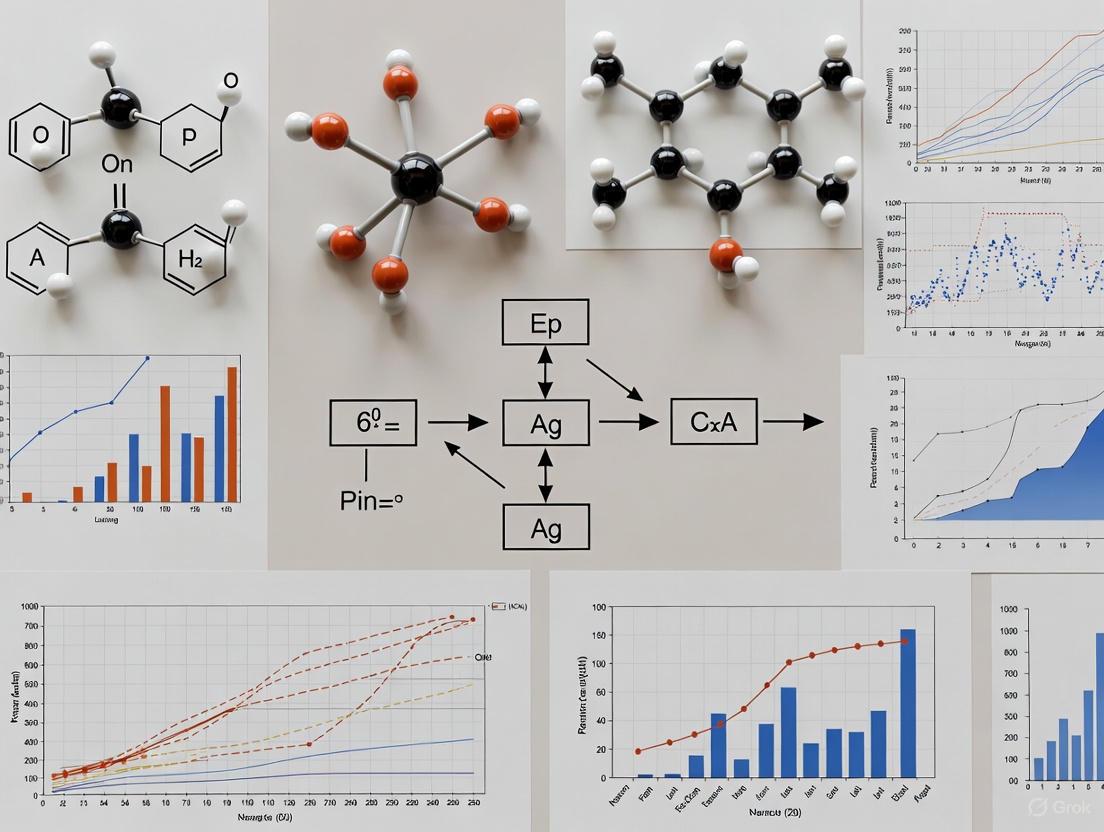

The following diagram illustrates the iterative workflow of this active learning process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of an active ML workflow relies on a suite of key reagents and computational resources.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Active ML-Driven Optimization

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Description | Example Use in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Platforms | Automated systems that rapidly test large numbers of reaction conditions in parallel [1]. | Generates the initial and iterative data required to train and inform the active learning model efficiently. |

| Active ML Software (e.g., LabMate.ML) | Algorithm that uses minimal initial data to suggest improved experimental protocols [4]. | The core engine of the optimization cycle; predicts the most informative conditions to test next. |

| Chemical Reaction Databases (e.g., Reaxys, ORD) | Large-scale, structured repositories of chemical reactions and associated conditions [2]. | Provides data for training global ML models that recommend general conditions for synthesis planning. |

| Diverse Catalyst & Ligand Libraries | A curated collection of catalysts and ligands, particularly for transition metal-catalyzed reactions. | Provides the chemical diversity needed for the algorithm to explore a wide and effective parameter space. |

| Solvent & Base Screening Sets | A selected array of solvents and bases with varied properties (polarity, acidity, etc.). | Enables the model to discover non-intuitive solvent-base interactions that impact yield and selectivity. |

A Paradigm of Human-AI Synergy

Ultimately, navigating the vast chemical space is not about replacing the chemist but augmenting their capabilities. The most successful strategies combine the rapid exploration capabilities of AI with the deep understanding of experienced chemists [1]. While AI can accelerate discovery and reveal novel relationships that defy human intuition [4], human expertise remains invaluable for selecting appropriate chemical descriptors, validating predictions, and guiding the overall research direction [1]. This synergy between human chemical intuition and artificial intelligence represents a new paradigm, poised to reshape organic chemistry research [1].

Active Machine Learning (Active ML) is an iterative, data-efficient paradigm that intelligently selects the most informative experiments to perform, thereby accelerating scientific discovery and optimization. In the context of organic chemistry, it represents a fundamental shift from traditional labor-intensive, trial-and-error approaches towards a closed-loop system where machine learning algorithms guide experimental design [5] [1]. This paradigm combines machine learning with experimental design to navigate complex, high-dimensional parameter spaces—such as reaction conditions, catalyst compositions, and synthesis parameters—with dramatically reduced experimental overhead [5] [6]. By prioritizing data acquisition where the model is most uncertain or where performance gains are most likely, Active ML achieves optimal outcomes with minimal experiments, making it particularly valuable for resource-intensive domains like drug development and catalyst design [6] [7].

Application Notes: Key Use Cases in Chemistry

The implementation of Active ML has led to groundbreaking improvements in various chemical research domains. The table below summarizes two prominent, high-impact applications.

Table 1: Quantitative Outcomes of Active ML Implementation in Chemical Research

| Application Area | Key Achievement | Experimental Efficiency | Performance Improvement | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Development for Higher Alcohol Synthesis | Identified optimal FeCoCuZr catalyst (Fe65Co19Cu5Zr11) | 86 experiments from ~5 billion combinations (>90% reduction in cost/environmental footprint) [6] | Achieved stable higher alcohol productivity of 1.1 gHA h⁻¹ gcat⁻¹, a 5-fold improvement over typical yields [6] | [6] |

| Suzuki-Miyaura Cross-Coupling Reaction Optimization | Exploration of an unreported reaction for α-Aryl N-heterocycles | Suitable conditions (ligand PAd3, solvent 1,4-dioxane) identified in only 15 runs [8] | Achieved an isolated yield of 67% [8] | [8] |

These case studies demonstrate the core strength of Active ML: its ability to efficiently navigate vast experimental spaces that are intractable for human researchers or traditional high-throughput screening alone. The catalyst development example highlights its power in optimizing complex, multi-component material systems [6], while the Suzuki-Miyaura coupling showcases its utility in rapidly optimizing conditions for novel organic transformations with minimal experimental runs [8].

Experimental Protocols

The power of Active ML is realized through a standardized, iterative workflow. The following protocol details the key stages for implementing a closed-loop optimization campaign for organic reaction conditions.

Core Workflow for Reaction Condition Optimization

The diagram below illustrates the continuous, closed-loop cycle that integrates computation and experimentation.

Detailed Protocol Steps

Step 1: Initial Data Collection

- Objective: Establish a baseline dataset for training the initial machine learning model.

- Procedure:

- Define the parameter space to be explored (e.g., temperature, solvent, catalyst, ligand, concentration) [7].

- If no prior data exists, use a space-filling design like Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) to generate 10-20 initial experimental conditions that broadly cover the defined space [9].

- Execute these initial experiments and record the outcome of interest (e.g., reaction yield, selectivity).

Step 2: Train the Machine Learning Model

- Objective: Create a surrogate model that predicts the outcome of untested conditions.

- Procedure:

- A common and effective choice is Gaussian Process (GP) Regression [6] [9]. The GP model provides a probabilistic prediction (mean and variance) for any point in the parameter space, quantifying its own uncertainty.

- Train the GP model using the collected experimental data, where the inputs are the reaction conditions and the output is the measured performance metric.

Step 3: Suggest New Experiments via an Acquisition Function

- Objective: Leverage the model to intelligently select the most promising conditions for the next round of experimentation.

- Procedure:

- Use an acquisition function to balance exploration (sampling where uncertainty is high) and exploitation (sampling where predicted performance is high) [6].

- The Expected Improvement (EI) function is widely used to find conditions expected to improve upon the current best [6].

- The Predictive Variance (PV) function can be used to prioritize exploring regions of high uncertainty [6].

- The algorithm typically suggests a batch of several candidate conditions (e.g., 3-6) for the next experimental cycle.

Step 4: Execute and Analyze Experiments

- Objective: Generate new, high-quality data to improve the model.

- Procedure:

Step 5: Iterate or Conclude

- Objective: Determine if the optimization goal has been met.

- Procedure:

- Add the new experimental results to the training dataset.

- Re-train the GP model with the updated, larger dataset.

- Repeat steps 2-4 until a performance target is met, performance plateaus, or the experimental budget is exhausted.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of an Active ML campaign relies on both computational and experimental components. The following table details the essential "reagents" for building such a system.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for an Active ML Framework

| Tool Category | Specific Tool/Technique | Function in the Active ML Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Core ML Algorithms | Gaussian Process (GP) Regression [6] [9] | Serves as the surrogate model for predicting reaction outcomes and quantifying uncertainty. |

| Bayesian Optimization (BO) [5] [9] | The overarching optimization framework that uses the GP to guide experiment selection. | |

| Acquisition Functions | Expected Improvement (EI) [6] | Identifies conditions most likely to outperform the current best result (exploitation). |

| Predictive Variance (PV) [6] | Identifies conditions in the least-explored regions of parameter space (exploration). | |

| Experimental Platforms | High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) [10] [7] | Enables rapid, parallel execution of suggested experiments, closing the automation loop. |

| Automated Batch/Self-Optimizing Flow Reactors [7] [1] | Provides the physical hardware for automated reaction execution and analysis. | |

| Enabling Software | Custom Python Scripts (e.g., with scikit-learn, GPy) [9] | Implements the ML and optimization logic; often custom-built for specific research needs. |

| Specialized LLMs (e.g., Chemma) [8] | Assists in tasks like condition generation and yield prediction, leveraging chemical knowledge. |

Advanced Implementation: Multi-Objective and Flexible Frameworks

Real-world optimization often involves balancing multiple, competing objectives. Advanced Active ML frameworks extend beyond single-target optimization.

Multi-Objective Optimization

In many synthetic applications, the goal is not only to maximize yield but also to improve other metrics such as selectivity, purity, or cost, or to minimize byproducts [6] [11]. Multi-objective Bayesian optimization can be employed to identify a set of Pareto-optimal conditions—conditions where one objective cannot be improved without worsening another [6]. For example, in higher alcohol synthesis, a trade-off was identified between maximizing productivity and minimizing selectivity of undesired CO₂ and CH₄, revealing a family of optimal solutions not immediately obvious to human experts [6].

Flexible Batch Bayesian Optimization

Practical laboratory hardware imposes constraints on experimentation. A key advancement is the development of flexible batch optimization algorithms that respect these constraints [9]. For instance, a liquid handler may prepare a 96-well plate (enabling 96 different compositions), but the system may only have three independent heating blocks (limiting temperature to 3 unique values per batch) [9]. Flexible frameworks use strategies like clustering or two-stage optimization to efficiently sample within these real-world hardware limitations, bridging the gap between idealized algorithms and practical implementation [9].

The Role of Human-AI Collaboration

A critical insight from recent research is that the most effective systems leverage human-AI synergy [1]. The role of Active ML is not to replace the chemist but to augment their intuition and expertise. Human decision-making remains invaluable for supervising the process, incorporating prior chemical knowledge, fine-tuning the algorithm's suggestions, and interpreting the final results to gain mechanistic insights [6] [1]. This collaborative model is the cornerstone of the next generation of chemical research.

In the pursuit of efficient organic reaction condition optimization, active machine learning (ML) promises to accelerate discovery through iterative experimental design. However, this paradigm faces two interconnected fundamental challenges: the scarcity and variable quality of experimental data, and the molecular representation bottleneck that limits how chemical structures are encoded for machine learning algorithms. Dataset scarcity manifests across multiple dimensions, including limited labeled examples for specific molecular properties, severe task imbalance in multi-task learning scenarios, and the high computational cost of generating quantum chemical data for transition states [12] [13] [14]. Concurrently, representing molecules in formats that capture essential structural and electronic features while remaining computationally tractable presents persistent difficulties, particularly when labeled data is limited [15] [16]. These challenges collectively constrain the real-world applicability of ML-guided optimization in organic synthesis, necessitating both methodological innovations and practical frameworks for experimental implementation.

Quantifying the Data Scarcity Landscape

The data scarcity challenge extends beyond simple volume limitations to encompass fundamental issues of distribution, quality, and accessibility across chemical domains. Table 1 systematically categorizes the dimensions of data scarcity and their impacts on reaction optimization.

Table 1: Dimensions and Impacts of Data Scarcity in Reaction Optimization

| Scarcity Dimension | Manifestation | Impact on ML Models | Exemplary Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Labeled Example Scarcity | Fewer than 30 labeled samples for specific molecular properties [13] | Models fail to generalize; overfitting to limited patterns | Accurate predictions demonstrated with only 29 labeled samples for sustainable aviation fuel properties [13] |

| Task Imbalance | Certain properties have far fewer labels than others in multi-task learning [13] | Negative transfer where updates from one task degrade another | Performance drops of up to 15.3% on ClinTox dataset without proper mitigation [13] |

| Transition State Data | Complex quantum calculations required; limited to small organic systems [14] | Inadequate sampling of reaction mechanism space | Current TS datasets cover only limited reaction types and chemical spaces [14] |

| Temporal Data Distribution | Measurement techniques and standards evolve over time [13] | Inflated performance estimates with random splits versus time splits | Models show reduced performance under time-split evaluations that mirror real-world scenarios [13] |

| Spatial Data Distribution | Molecular data clusters in distinct regions of latent space [13] | Reduced benefits of shared representations in multi-task learning | Data distribution mismatches hinder knowledge transfer across tasks [13] |

The fundamental challenge of molecular representation compounds these data scarcity issues. As noted in recent research, molecular representation techniques constitute the "primary bottleneck" in advancing localized reaction condition optimization [16]. This representation bottleneck manifests through limitations in capturing 3D geometric information, electronic properties, and dynamic conformational changes—all critical for predicting reaction outcomes.

Molecular Representation Modalities and Their Limitations

Molecular representation learning has catalyzed a paradigm shift from manually engineered descriptors to automated feature extraction using deep learning [15]. Table 2 compares the predominant molecular representation approaches and their specific limitations in low-data regimes.

Table 2: Molecular Representation Modalities and Limitations for Reaction Optimization

| Representation Type | Format | Advantages | Limitations in Low-Data Regimes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Descriptors | SMILES strings, molecular fingerprints [15] | Compact, easily computable, suitable for database searches | Struggle with capturing molecular complexity and interactions; fixed nature cannot adapt to dynamic behaviors [15] |

| Graph-Based Representations | Node-link diagrams, adjacency matrices [15] | Explicitly encode atomic connectivity and structural relationships | Require sufficient examples to learn meaningful features; may overlook spatial and electronic properties [15] [12] |

| 3D-Aware Representations | 3D graphs, energy density fields [15] | Capture spatial geometry critical for molecular interactions | Computationally expensive; limited by availability of 3D structural data [15] |

| Sequence-Based (LLMs) | SMILES as text sequences [8] | Leverage powerful language model architectures; can learn from reaction databases | May generate chemically invalid structures; require extensive pre-training data [8] |

| Multi-Modal Fusion | Integration of graphs, sequences, and quantum descriptors [15] | Comprehensive molecular characterization; complementary information | Increased model complexity; requires careful alignment across modalities [15] |

The limitations of these representations become particularly pronounced in few-shot learning scenarios, where models must generalize from minimal examples. In such cases, models face the dual challenges of cross-property generalization under distribution shifts and cross-molecule generalization under structural heterogeneity [12]. This means they must transfer knowledge across weakly correlated tasks with different data distributions while handling significant structural diversity in molecular inputs with limited training examples.

Experimental Protocols for Low-Data Regimes

Protocol 1: Adaptive Checkpointing with Specialization (ACS) for Multi-Task Learning

Purpose: To mitigate negative transfer in multi-task graph neural networks when dealing with severely imbalanced molecular property datasets [13].

Materials:

- Molecular dataset with multiple property annotations (e.g., ClinTox, SIDER, Tox21)

- Graph neural network architecture with message passing backbone

- Task-specific multi-layer perceptron (MLP) heads

Procedure:

- Architecture Setup: Implement a shared GNN backbone with task-specific MLP heads. The backbone learns general-purpose latent representations, while dedicated heads provide specialized capacity for each task.

- Training Configuration: Monitor validation loss for every task throughout training.

- Checkpointing Mechanism: Save model parameters whenever any task achieves a new minimum validation loss.

- Specialization: For each task, select the checkpointed backbone-head pair that achieved its optimal validation performance.

- Validation: Evaluate on held-out test sets using task-specific specialized models.

Applications: This protocol has demonstrated accurate predictions with as few as 29 labeled samples for sustainable aviation fuel properties, surpassing conventional multi-task learning and single-task approaches [13].

Protocol 2: Active Machine Learning with Minimal Experimental Data

Purpose: To optimize organic synthesis conditions using only 5-10 initial data points through active learning [4].

Materials:

- LabMate.ML software or equivalent active learning framework

- Random forest models or Bayesian optimization algorithms

- Experimental setup for target reaction

Procedure:

- Initialization: Collect 5-10 initial data points covering diverse reaction conditions.

- Model Training: Train random forest models on available data to learn condition-property relationships.

- Condition Suggestion: Use the model to suggest promising experimental conditions based on acquisition functions (e.g., expected improvement, upper confidence bound).

- Experimental Feedback: Execute suggested experiments and measure outcomes (e.g., yield, selectivity).

- Iterative Learning: Incorporate feedback into training data and repeat steps 2-4 until satisfactory performance is achieved.

- Model Analysis: Quantify parameter importance to extract chemical insights and novel relationships.

Applications: This protocol has successfully optimized various reaction types, including small-molecule, glyco, and protein chemistry, typically requiring only 1-10 additional experiments beyond initial data [4].

Protocol 3: Tera-Scale Mass Spectrometry Data Mining for Reaction Discovery

Purpose: To discover previously unknown organic reactions by analyzing existing high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) data without new experiments [3].

Materials:

- MEDUSA Search engine or equivalent infrastructure

- Tera-scale database of HRMS spectra (e.g., 8+ TB of 22,000 spectra)

- Isotopic distribution calculation algorithms

Procedure:

- Hypothesis Generation: Generate potential reaction pathways based on breakable bonds and fragment recombination using BRICS fragmentation or multimodal LLMs.

- Theoretical Pattern Calculation: Compute theoretical isotopic patterns for query ions based on chemical formulas and charges.

- Coarse Search: Identify candidate spectra containing the two most abundant isotopologue peaks using inverted indexes.

- Isotopic Distribution Search: Perform detailed isotopic distribution matching within candidate spectra using cosine similarity metrics.

- False Positive Filtering: Apply machine learning models to filter false matches based on isotopic distribution characteristics.

- Validation: Confirm discovered reactions through orthogonal methods like NMR or tandem MS.

Applications: This approach has identified previously undescribed transformations, such as heterocycle-vinyl coupling processes in Mizoroki-Heck reactions, from existing archival data [3].

Visualization of Methodological Approaches

Diagram 1: Interplay between data challenges, solutions, and molecular representations. The ACS protocol addresses limited labeled examples and task imbalance, while active learning and mass spectrometry mining target other scarcity dimensions through different representation strategies.

Diagram 2: Active machine learning workflow for reaction optimization with minimal data. The iterative loop between suggestion and experimental feedback enables efficient exploration of reaction condition space with limited initial data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Overcoming Data Challenges

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| MEDUSA Search Engine | Software Platform | Discovers unknown reactions from existing mass spectrometry data | Mining tera-scale HRMS databases (22,000+ spectra) for unreported transformations [3] |

| ACS Framework | Algorithmic Framework | Mitigates negative transfer in multi-task learning | Molecular property prediction with severe task imbalance (e.g., ClinTox dataset) [13] |

| LabMate.ML | Active Learning Software | Optimizes reactions with minimal experimental data | Condition optimization with only 5-10 initial data points across diverse chemistry types [4] |

| Chemma LLM | Fine-tuned Language Model | Assists in retrosynthesis and condition generation | Single-step retrosynthesis, yield prediction, and reaction optimization [8] |

| 3D Infomax | Representation Method | Enhances GNNs using 3D molecular geometries | Property prediction requiring spatial and conformational awareness [15] |

| Graph Neural Networks | Model Architecture | Learns molecular representations from graph structures | Few-shot molecular property prediction with structural heterogeneity [15] [12] |

| BRICS Fragmentation | Computational Method | Decomposes molecules into logical building blocks | Hypothesis generation for reaction discovery in mass spectrometry mining [3] |

Concluding Perspective: Integrated Approaches for Future Progress

The interdependent challenges of dataset scarcity and molecular representation bottlenecks require integrated solutions that leverage both algorithmic innovations and strategic experimental design. The methodologies outlined in this document—from adaptive checkpointing for multi-task learning to active ML frameworks for experimental optimization—provide actionable pathways for advancing organic reaction condition optimization despite fundamental data limitations. Future progress will likely hinge on developing more sophisticated molecular representations that better capture chemical intuition with less data, while simultaneously creating frameworks that maximize knowledge extraction from limited experimental observations. As these approaches mature, the synergy between human chemical expertise and machine intelligence will be essential for navigating the complex tradeoffs between data efficiency, representational power, and practical utility in synthetic chemistry.

In organic chemistry, the pursuit of optimal reaction conditions is often hindered by a fundamental challenge known as the "Completeness Trap"—the impractical belief that exhaustive screening of all possible parameter combinations is a feasible or efficient route to success. The chemical parameter space for even a simple reaction is astronomically large, growing exponentially with each additional variable [17]. Where a chemist might traditionally rely on a handful of relevant transformations and intuitive hypotheses to navigate this space, machine learning (ML) approaches often require orders of magnitude more data, creating a significant practical disconnect [18]. This Application Note frames the problem within the context of active machine learning, a subfield of AI that operates iteratively with minimal data, mirroring the chemist's own hypothesis-driven approach [18]. We detail protocols and tools that enable researchers to escape the Completeness Trap by replacing exhaustive screening with efficient, intelligent exploration.

The Problem: Exponentially Expanding Parameter Spaces

The core of the Completeness Trap is the combinatorial explosion of possible experiments when multiple reaction parameters are considered. A reaction parameter space consists of numerous categorical parameters (e.g., catalyst, solvent, ligand) and continuous parameters (e.g., temperature, concentration, reaction time) [17]. The following analysis illustrates the infeasibility of exhaustive screening.

Table 1: Combinatorial Explosion in a Hypothetical Reaction Optimization

| Number of Parameters | Values per Parameter | Total Experiments in Full Factorial Design |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | 5 | 125 (5³) |

| 5 | 5 | 3,125 (5⁵) |

| 8 | 5 | 390,625 (5⁸) |

| 10 | 5 | 9,765,625 (5¹⁰) |

As shown in Table 1, the parameter space grows exponentially. For a reaction with 10 parameters, each with just 5 possible values, nearly 10 million unique experiments would be required for a full factorial screen [17]. This is computationally and experimentally intractable. Real-world optimization campaigns must therefore employ strategies that do not rely on completeness.

The Strategic Solution: Active Machine Learning

Active machine learning provides a framework for escaping the Completeness Trap by strategically selecting the most informative experiments to perform. This creates a tight, iterative feedback loop between computation and experimentation, maximizing knowledge gain while minimizing resource expenditure.

Core Workflow and Protocol

The following protocol describes a generalized workflow for an active ML-guided reaction optimization campaign.

Protocol 1: Active ML-Guided Reaction Optimization

Objective: To efficiently identify optimal reaction conditions within a high-dimensional parameter space using an iterative, AI-guided process.

Materials:

- CIME4R or similar visual analytics platform [17]

- Bayesian Optimization software (e.g., EDBO [17])

- Standard laboratory equipment for synthesis and analysis (e.g., HPLC, NMR)

Procedure:

- Problem Formulation & Initialization:

- Define the parameter space, identifying all categorical and continuous variables to be optimized.

- Set the optimization objective(s) (e.g., maximize yield, improve selectivity).

- Select and run a small, diverse batch of initial experiments (5-10 data points) to seed the model [4].

Model Training & Prediction:

- Input the collected experimental data into the active ML model.

- The model (e.g., a Bayesian optimizer) processes the dataset and generates predictions and uncertainty estimates for all unexplored experiments in the parameter space [17].

Informed Decision Point:

- Use an acquisition function to balance exploration (testing in uncertain regions) and exploitation (refining known high-performing regions).

- Analyze model suggestions using a tool like CIME4R to understand the prediction rationale (e.g., via SHAP values) and calibrate trust [17].

- Select the next batch of experiments based on the AI's suggestions, potentially overruling based on expert intuition.

Iteration and Convergence:

- Execute the new batch of experiments in the laboratory.

- Augment the dataset with the new results.

- Repeat steps 2-4 until the optimization objective is met or resources are exhausted.

The logical relationships and workflow of this protocol are visualized in the following diagram.

Case Study & Performance Data

Active ML strategies have been validated in real-world optimization tasks. For instance, the software "LabMate.ML" was able to optimize organic synthesis conditions using only 5-10 initial data points, requiring just 1-10 additional experiments to find suitable conditions across nine different use cases. This performance was on par with or superior to the efforts of PhD-level chemists, who needed "at least as many experiments" to achieve the same result [4]. The quantitative efficiency gains are summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Optimization Approaches

| Optimization Method | Typical Experiments to Solution | Key Characteristics | Risk of Completeness Trap |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exhaustive Screening | 1,000 - 10,000,000+ | Theoretically comprehensive, practically infeasible | Very High |

| One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) | Medium-High | Simple, fails to capture interactions | Medium |

| Design of Experiment (DoE) | Medium | Statistically efficient, requires pre-defined design | Low-Medium |

| Active Machine Learning | 10 - 30 [4] | Iterative, data-efficient, adaptive | Very Low |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key components and tools essential for implementing an active ML workflow in reaction optimization.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Active ML-Guided Optimization

| Tool or Reagent | Function/Description | Role in Active ML Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Bayesian Optimization Algorithm | A probabilistic model that balances exploration and exploitation. | Core engine for predicting the next best experiments. [17] |

| Visual Analytics Platform (e.g., CIME4R) | An interactive web application for analyzing RO data and AI predictions. | Aids human-AI collaboration; helps visualize parameter spaces and model decisions. [17] |

| Reaction Database (e.g., USPTO, Reaxys) | Large, structured sources of published chemical reactions. | Can serve as a source domain for transfer learning or pre-training models. [18] |

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) | Technology for rapidly conducting numerous micro-scale experiments. | Accelerates the data generation feedback loop for the ML model. [19] |

| Solvent Selection Guide (e.g., CHEM21) | A metric ranking solvents by safety, health, and environmental (SHE) impact. | Informs the definition of a "good" outcome by integrating green chemistry principles. [20] |

The "Completeness Trap" is a pervasive illusion in chemical research. The exponential nature of chemical parameter spaces makes exhaustive screening a theoretical ideal but a practical impossibility. Active machine learning, especially when coupled with visual analytics tools that promote human-AI collaboration, offers a robust and efficient escape from this trap. By adopting the protocols and strategies outlined in this Application Note, researchers can systematically navigate vast experimental landscapes, leveraging both computational power and chemical intuition to accelerate discovery while conserving valuable resources.

Core Algorithms and Real-World Implementation in the Lab

In the field of organic chemistry and drug discovery, optimizing reaction conditions to maximize yield or other objectives is a fundamental yet resource-intensive process. Bayesian optimization (BO) has emerged as a powerful machine learning framework that efficiently balances exploration of unknown parameter spaces with exploitation of known promising regions. This balance is critical for reducing the number of experiments required in chemical reaction optimization, accelerating the development of synthetic routes for active pharmaceutical ingredients and other functional chemicals.

BO operates as a sequential design strategy that uses a probabilistic surrogate model, typically a Gaussian process, to approximate an unknown objective function (e.g., reaction yield). It combines this with an acquisition function that guides the selection of subsequent experiments by quantifying the trade-off between exploring uncertain regions and exploiting areas predicted to be high-performing. This approach is particularly valuable in chemical applications where experiments are costly and the parameter space is high-dimensional, enabling more efficient data-driven decisions compared to traditional optimization methods [21] [22].

Key Principles and Algorithmic Framework

Core Components of Bayesian Optimization

Bayesian optimization relies on two primary components working in tandem. First, the Gaussian process (GP) serves as a probabilistic surrogate model that provides a distribution over possible functions fitting the observed data. The GP not only predicts yields at untested reaction conditions but also quantifies the uncertainty of these predictions. Second, the acquisition function uses this probabilistic information to decide where to sample next. Common acquisition functions include Expected Improvement (EI), Probability of Improvement (PI), and Upper Confidence Bound (UCB), each implementing the exploration-exploitation balance differently [21].

The iterative BO process can be summarized as: (1) Build a surrogate model of the objective function using all available data; (2) Find the next experiment point by maximizing the acquisition function; (3) Evaluate the objective function at the proposed point (run the experiment); (4) Update the surrogate model with the new result; and (5) Repeat until convergence or resource exhaustion. This sequential approach has demonstrated superior efficiency in reaction optimization compared to human decision-making, both in average optimization efficiency and consistency [22].

Adaptation to Chemical Constraints

In drug discovery and reaction optimization, BO must accommodate specific constraints not present in standard optimization problems. These include categorical variables (e.g., catalyst type, solvent choice), safety considerations, material costs, and multi-objective optimization (e.g., balancing yield, purity, and cost). Advanced BO implementations address these challenges through specialized surrogate models and acquisition functions. For instance, Gryffin handles categorical variables informed by physical intuition, while Constrained Bayesian optimization incorporates known safety or feasibility boundaries directly into the optimization framework [21].

Table 1: Key Components of Bayesian Optimization in Chemistry

| Component | Function | Examples/Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| Surrogate Model | Approximates the unknown objective function; provides uncertainty estimates | Gaussian Processes, Random Forests |

| Acquisition Function | Balances exploration and exploitation to select next experiment | Expected Improvement, Upper Confidence Bound |

| Domain Handling | Manages chemical constraints and parameter types | Gryffin (categorical variables), Constrained BO |

| Transfer Learning | Incorporates prior knowledge from related systems | LLM-derived utility functions, historical data |

Application Notes: Implementing Bayesian Optimization

Dynamic Experiment Optimization (DynO) for Flow Chemistry

The DynO framework represents a recent advancement specifically designed for chemical reaction optimization in flow systems. This method leverages both Bayesian optimization and data-rich dynamic experimentation, making it particularly suitable for automated flow chemistry platforms. DynO incorporates simple stopping criteria that guide non-expert users in conducting fast and reagent-efficient optimization campaigns [23].

In silico comparisons demonstrate that DynO performs remarkably well in Euclidean design spaces, outperforming other algorithms like Dragonfly. The method has been experimentally validated using an ester hydrolysis reaction on an automated platform, showcasing its practical implementation simplicity. For flow chemistry applications, DynO efficiently explores continuous parameters such as flow rates, temperatures, and concentrations while managing the unique constraints of continuous reaction systems [23].

Integrating Large Language Models for Enhanced BO

Recent research has explored distilling quantitative insights from Large Language Models (LLMs) to enhance Bayesian optimization of chemical reactions. A survey-like prompting scheme combined with preference learning can infer a utility function that models prior chemical information embedded in LLMs over a chemical parameter space. Despite operating in a zero-shot setting, this utility function shows modest correlation to true experimental measurements (yield) [24].

When leveraged to focus BO efforts in promising regions of the parameter space, the LLM-derived utility function improves the yield of the initial BO query and enhances optimization in most datasets studied. This approach represents a significant step toward bridging the gap between the implicit chemistry knowledge embedded in LLMs and the principled optimization capabilities of BO methods, potentially accelerating reaction optimization in low-data regimes [24].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Bayesian Optimization Methods

| Method | Application Context | Key Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard BO | Palladium-catalyzed direct arylation | Outperforms human decision-making in efficiency and consistency | [22] |

| DynO | Ester hydrolysis in flow | Superior to Dragonfly algorithm in Euclidean spaces | [23] |

| LLM-Enhanced BO | Multiple reaction datasets | Improves initial query yield and enhances optimization in 4 of 6 datasets | [24] |

| Active Learning Protocol | Ultralarge chemical spaces | Recovers up to 98% of virtual hits while scanning only 5% of full space | [25] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Implementing Bayesian Optimization for Reaction Screening

Objective: Optimize reaction conditions (e.g., temperature, catalyst concentration, solvent ratio) to maximize yield using Bayesian optimization.

Materials and Equipment:

- Automated reaction platform (e.g., flow reactor system or automated batch reactor)

- Analytical instrumentation (e.g., HPLC, GC-MS, or NMR for yield quantification)

- Computer with Bayesian optimization software (e.g., EDBO, Phoenics, or Gryffin)

Procedure:

- Define Parameter Space: Identify key reaction parameters to optimize and their respective ranges (e.g., temperature: 25-100°C, catalyst loading: 1-5 mol%, reaction time: 1-24 hours).

- Select Objective Function: Define the primary optimization target (e.g., yield, conversion, or selectivity) and any constraints (e.g., impurity thresholds).

- Initialize with Design of Experiments: Run 5-10 initial experiments using Latin Hypercube Sampling or other space-filling designs to build initial surrogate model.

- Configure Bayesian Optimization:

- Choose Gaussian process surrogate model with Matérn kernel

- Select acquisition function (Expected Improvement recommended for beginners)

- Set convergence criteria (e.g., minimal improvement over 5 iterations)

- Iterative Optimization:

- Generate next experiment suggestion by maximizing acquisition function

- Execute suggested experiment in automated platform

- Analyze outcome and update dataset

- Re-fit surrogate model with new data point

- Validation: Confirm optimal conditions with triplicate experiments.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- For categorical variables (e.g., solvent or catalyst type), use specialized implementations like Gryffin

- If optimization stagnates, consider increasing exploration parameter in acquisition function

- For high-dimensional spaces (>10 parameters), consider using random forest instead of GP as surrogate model [23] [22]

Protocol: Active Learning for Reagent Selection from Ultralarge Chemical Spaces

Objective: Identify the most suitable commercial chemical reagents and one-step organic chemistry reactions for prioritizing target-specific hits from ultralarge chemical spaces.

Materials:

- Database of commercial chemical reagents

- Protein binding site structural information

- Computational resources for docking simulations

Procedure:

- Define Chemical Space: Establish the size and composition of the chemical space to be explored (e.g., 4.5 billion compounds).

- Implement Active Learning Protocol:

- Start from the sole three-dimensional structure of a protein binding site

- Use Bayesian optimization to propose commercial chemical reagents and one-step organic chemistry reactions

- Enumerate target-specific primary hits through iterative screening

- Iterative Screening:

- Select most promising reagent combinations based on acquisition function

- Perform docking-based evaluation of selected compounds

- Update model with performance data

- Repeat until hitting predefined performance threshold or budget

- Validation: Confirm hits through experimental testing or more rigorous computational methods.

This protocol has demonstrated efficiency in addressing chemical spaces of various sizes (from 670 million to 4.5 billion compounds), recovering up to 98% of virtual hits discovered by exhaustive docking-based approaches while scanning only 5% of the full chemical space [25].

Workflow Visualization

Bayesian Optimization Workflow for Reaction Optimization

Exploration-Exploitation Balance in Acquisition Functions

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Bayesian Optimization

| Reagent/Material | Function in Optimization | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Automated Flow Reactor Systems | Enables precise control and high-throughput experimentation | Essential for implementing DynO framework; allows dynamic parameter adjustment [23] |

| Commercial Chemical Reagent Databases | Source space for active learning approaches | Critical for ultralarge chemical space exploration; enables virtual screening [25] |

| Gaussian Process Software (GPyTorch, scikit-learn) | Implements surrogate modeling for BO | Provides probabilistic predictions with uncertainty estimates [21] |

| Bayesian Optimization Libraries (EDBO, Phoenics, Gryffin) | User-friendly implementation of BO algorithms | EDBO specifically designed for chemical applications [22] |

| Large Language Models (LLMs) | Source of prior chemical knowledge | Can be queried to derive utility functions for transfer learning [24] |

| High-Throughput Analytical Equipment (HPLC, GC-MS) | Rapid quantification of reaction outcomes | Essential for fast feedback in iterative BO loops [22] |

Bayesian optimization represents a paradigm shift in how chemists approach reaction optimization, offering a principled framework for balancing exploration of unknown chemical spaces with exploitation of promising regions. The methods and protocols outlined here provide researchers with practical tools for implementing BO in various contexts, from flow chemistry optimization to reagent selection from ultralarge chemical spaces. As Bayesian optimization continues to evolve through integration with emerging technologies like large language models and increasingly automated laboratory platforms, its role as a workhorse methodology in chemical research and drug discovery is poised to expand further, enabling more efficient and sustainable approaches to molecular design and synthesis.

The field of organic chemistry is undergoing a remarkable transformation driven by the convergence of laboratory automation and artificial intelligence. This integration is creating unprecedented opportunities for accelerating chemical discovery and optimization, particularly in the critical area of reaction condition optimization [1]. Rather than replacing human expertise, the most successful approaches combine the rapid exploration capabilities of AI with the deep chemical understanding of experienced chemists [1]. This human-in-the-loop paradigm represents a fundamental shift from traditional optimization methods that relied heavily on manual experimentation guided by chemical intuition alone, or design of experiments approaches where reaction variables were modified one at a time [7]. The emerging framework leverages adaptive experimentation systems where machine learning algorithms and human expertise interact synergistically throughout the optimization process, dramatically increasing the speed and efficiency of chemical optimization with respect to both economic and environmental objectives [1].

Core Workflow: Human-AI Collaborative Optimization

The integration of human expertise with AI-driven optimization follows a structured workflow that maximizes the strengths of both human intuition and machine intelligence. This collaborative process enables more efficient navigation of complex chemical spaces while maintaining the chemical insight essential for meaningful discovery.

Figure 1: Human-in-the-Loop Optimization Workflow. This diagram illustrates the iterative collaboration between chemist expertise and machine learning algorithms in reaction optimization.

The workflow begins with human chemists defining the reaction space and key parameters based on their chemical knowledge and research objectives [1] [7]. This initial guidance is crucial for establishing feasible boundaries for the optimization process. The AI system then suggests initial experimental conditions, which are executed through high-throughput experimentation (HTE) platforms [7]. As experimental data is collected and analyzed, both the human expert and machine learning model engage in a dynamic exchange: the chemist validates results and generates new hypotheses based on chemical principles, while the ML algorithm updates its predictions to suggest the next most informative experiments [1] [26]. This iterative cycle continues until optimal conditions are identified, with human oversight ensuring chemically meaningful outcomes throughout the process.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Active Transfer Learning for Reaction Optimization

Active transfer learning represents a powerful methodology that combines the efficiency of transfer learning with the adaptive capabilities of active learning, closely mimicking how expert chemists develop new reactions [26].

Purpose: To optimize reaction conditions for new substrate classes by leveraging prior chemical knowledge and minimizing experimental effort.

Principles: This approach operates on the premise that a model trained on established reaction data (source domain) can provide intelligent starting points for exploring new reaction spaces (target domain), followed by active learning to refine predictions based on new experimental data [26].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Source Model Development: Train a random forest classifier on high-throughput experimentation data from a related, well-established reaction class (e.g., Pd-catalyzed C-N coupling reactions) [26].

- Initial Condition Suggestion: Use the source model to predict promising reaction conditions for the new substrate class, focusing on combinations of electrophile, catalyst, base, and solvent common between source and target domains [26].

- Experimental Validation: Execute top-predicted conditions (typically 5-10 reactions) using HTE platforms and quantify reaction outcomes [4] [7].

- Model Retraining: Incorporate new experimental results into the training set and update the model using active learning strategies.

- Iterative Optimization: Repeat steps 3-4 until optimal conditions are identified, typically requiring 1-10 additional experiments [4].

Key Considerations:

- Model simplification using a small number of decision trees with limited depth is crucial for securing generalizability and interpretability [26].

- Binary classification (success/failure) often provides more robust predictions than continuous yield optimization in low-data regimes [26].

- The closest transferability occurs between mechanistically similar reactions (e.g., between different nitrogen-based nucleophiles) [26].

Protocol 2: Closed-Loop Self-Optimization with Human Oversight

Fully automated closed-loop systems represent the most advanced implementation of AI-driven optimization, while still incorporating crucial human oversight at key decision points [1] [7].

Purpose: To autonomously optimize chemical reactions with minimal human intervention while maintaining expert validation of chemically meaningful results.

Principles: Integration of HTE platforms with machine learning optimization algorithms creates a self-driving laboratory that can design, execute, and analyze experiments autonomously [1] [7].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- System Configuration: Human experts define optimization objectives (e.g., yield, selectivity, cost) and constraint boundaries [7].

- Workflow Automation: Program HTE platform to perform liquid handling, reaction execution, and analytical characterization in a fully integrated workflow [7].

- Algorithm Selection: Implement Bayesian optimization or other ML optimization algorithms to suggest experiment sequences based on previous results [1].

- Human Monitoring: Researchers periodically review optimization progress and algorithm decisions to ensure chemical合理性.

- Intervention Points: Predefine thresholds for human intervention when unexpected results occur or when moving between optimization phases.

Key Considerations:

- Commercial platforms (Chemspeed, Zinsser Analytic) enable robust implementation but require significant investment [7].

- Custom-built systems can be tailored to specific research needs and often provide greater flexibility [7].

- Human oversight remains critical for interpreting results and adjusting optimization objectives based on chemical insight [1].

Performance Metrics and Comparative Analysis

Quantitative assessment of human-in-the-loop strategies demonstrates their significant advantages over traditional approaches or fully autonomous systems. The following table summarizes key performance indicators across multiple optimization methodologies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Optimization Strategies

| Optimization Method | Typical Experiments Required | Success Rate | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional OVAT | 20-100+ [7] | Variable | Simple implementation, low technical barrier | Inefficient, misses interactions, time-consuming |

| Human-in-the-Loop Active Learning | 1-10 additional after initial training [4] | High in prospective cases [4] | Balances efficiency with chemical insight, interpretable models | Requires some initial data, expert time needed |

| Active Transfer Learning | 5-10 training points + iterative queries [26] | ROC-AUC 0.88-0.93 for similar mechanisms [26] | Leverages prior knowledge, effective for new substrate classes | Performance depends on source-target relationship |

| Fully Automated Closed-Loop | Varies by complexity | High for defined spaces | Maximum throughput, minimal human effort | High initial investment, limited chemical insight |

The performance data reveals that human-in-the-loop strategies achieve an optimal balance between experimental efficiency and chemically meaningful results. In direct comparisons, PhD-level chemists typically required at least as many experiments as active learning software to find suitable conditions, demonstrating the efficiency of these approaches [4]. The transfer learning component shows particularly strong performance when source and target domains are mechanistically related, with ROC-AUC scores of 0.88-0.93 for closely related nucleophile classes in Pd-catalyzed cross-couplings [26].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Successful implementation of human-in-the-loop optimization strategies requires specific computational tools and experimental platforms. The following table details key resources that enable this collaborative workflow.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Human-in-the-Loop Optimization

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Role | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active Learning Software | LabMate.ML [4] | Optimizes organic synthesis conditions through active machine learning | Desktop executable, minimal data requirements (5-10 points) |

| HTE Platforms | Chemspeed SWING, Zinsser Analytic [7] | High-throughput parallel reaction execution | Enables 192 reactions in 24 hours [7] |

| Custom Robotic Systems | Mobile robot by Burger et al. [7] | Links multiple experimental stations for complex workflows | 2-year development time, handles 10-dimensional parameter search [7] |

| Portable Synthesis Platforms | System by Manzano et al. [7] | 3D-printed reactors for flexible reaction execution | Lower throughput but adaptable to various syntheses [7] |

| Transfer Learning Frameworks | Random forest classifiers [26] | Applies knowledge from established reactions to new domains | Most effective for mechanistically similar reactions [26] |

The tool ecosystem spans from accessible desktop software like LabMate.ML to sophisticated integrated systems, making human-in-the-loop approaches implementable across different resource environments [4] [7]. The random forest classifiers commonly employed in these methods offer the additional advantage of interpretability, allowing researchers to understand which parameters drive the algorithm's predictions [4].

Case Study: Active Transfer Learning for Pd-Catalyzed Cross-Couplings

A concrete implementation from recent literature demonstrates the practical application and performance of human-in-the-loop strategies for challenging reaction optimization problems.

Figure 2: Active Transfer Learning Case Study. Workflow for transferring knowledge from benzamide to sulfonamide coupling reactions with high predictive accuracy.

In this documented case study, researchers addressed the challenge of optimizing Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling conditions for phenyl sulfonamide nucleophiles using prior knowledge from benzamide reactions [26]. The process began with a random forest classifier trained on approximately 100 high-throughput experimentation data points from the benzamide source domain. When this pre-trained model was directly applied to sulfonamide reactions, it achieved exceptional predictive performance (ROC-AUC = 0.928) due to the mechanistic similarity between these nitrogen-based nucleophiles [26]. For more challenging transfers between different reaction mechanisms (e.g., from benzamide to pinacol boronate esters), the initial transfer showed poor performance (ROC-AUC = 0.133) but was rescued through active learning cycles that refined the model with minimal additional data [26]. This case highlights how human expertise in selecting appropriate source domains combines with algorithmic efficiency to accelerate optimization.

Human-in-the-loop strategies represent a transformative approach to chemical reaction optimization that transcends the limitations of both purely human-driven and fully autonomous methods. By creating a synergistic partnership between chemical intuition and artificial intelligence, these approaches achieve unprecedented efficiency while maintaining the chemical insight essential for meaningful discovery. The documented success of active transfer learning and adaptive experimentation platforms across diverse reaction classes demonstrates the robustness of this paradigm [1] [4] [26]. As these methodologies continue to evolve, key challenges and opportunities emerge in areas such as integrating prior knowledge through transfer learning, improving uncertainty quantification to identify when human oversight is most needed, and developing more interpretable AI models to facilitate collaboration between human and machine intelligence [1]. The future of chemical optimization lies not in replacing human expertise but in creating thoughtfully designed frameworks that leverage both human and artificial intelligence, accelerating discovery while deepening our fundamental understanding of chemical processes [1].

Leveraging Prior Knowledge with Transfer Learning and Fine-Tuning

In the field of organic synthesis, the exploration of optimal reaction conditions is a fundamental yet resource-intensive process. Traditional approaches rely heavily on chemical intuition and iterative experimentation, which can be slow and may overlook optimal solutions. Machine learning (ML) offers powerful tools to accelerate this process. However, a significant challenge persists: ML models typically require large, high-quality datasets to make accurate predictions, which are seldom available at the early stages of developing a new reaction or exploring a new substrate class.

Transfer learning and fine-tuning present a paradigm shift, enabling models to leverage knowledge from existing, data-rich chemical domains (the source) to make accurate predictions in a new, data-sparse domain (the target). This approach closely mirrors the practice of expert chemists who apply knowledge from related, established reactions to plan initial experiments for a new transformation. This application note details the protocols and experimental frameworks for implementing these strategies within an active machine learning workflow for organic reaction condition optimization.

Transfer learning strategies in chemical ML can be broadly categorized based on the nature of the source data and the model architecture used. The table below summarizes the principal approaches validated in recent literature, highlighting their performance and data requirements.

Table 1: Overview of Transfer Learning Strategies for Chemical Reaction Optimization

| Strategy | Source Data | Target Task | Key Model | Reported Performance | Data Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain Adaptation [27] | Photocatalytic cross-coupling yields | [2+2] cycloaddition yield prediction | TrAdaBoost (Gradient Boosting) | Improved prediction accuracy vs. conventional ML | Effective with only 10 target data points |

| Fine-Tuning Pre-trained Models [28] | USPTO reaction SMILES; ChEMBL molecules | HOMO-LUMO gap prediction for organic materials | BERT (Transformer) | R² > 0.94 on 3 of 5 virtual screening tasks [28] | Leverages large public datasets for pretraining |

| Active Transfer Learning [26] | Pd-catalyzed C-N coupling data | Pd-catalyzed C-O/C-S coupling condition prediction | Simplified Random Forest | High ROC-AUC (>0.88) for related nucleophiles [26] | Effective with ~100 source data points |

| Virtual Database Pretraining [29] | Custom-tailored virtual molecules (topological indices) | Photocatalytic C-O bond formation yield | Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) | Improved predictive performance for real OPSs [29] | Uses cost-effective pretraining labels |

These strategies demonstrate that it is not always necessary to build a model from scratch. By strategically reusing knowledge, researchers can achieve high predictive performance with minimal target-domain experimental effort.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Domain Adaptation for Photocatalytic Reaction Yield Prediction

This protocol is adapted from studies that successfully transferred knowledge between different photocatalytic reactions, such as from cross-coupling to [2+2] cycloaddition, using a domain adaptation algorithm [27].

Workflow Diagram: Domain Adaptation for Photocatalysis

Materials and Reagents:

- Organic Photosensitizers (OPSs): A diverse library of 60-100 OPSs, including D-A-type, π–π-type, n–π-type, and cationic structures [27].

- Substrates: Relevant to the source (e.g., aryl halides) and target (e.g., alkenes) reactions.

- Solvents & Additives: Anhydrous, reagent-grade solvents (e.g., toluene, DMF) and necessary bases or other additives.

- Hardware/Software: High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) robotic platform for parallel synthesis; computing cluster for descriptor generation.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Source Data Curation: Collect a dataset of OPS structures and their corresponding product yields from a well-established source reaction (e.g., a Ni/photocatalytic C–O coupling) [27].

- Initial Target Data Generation: Conduct a small, diverse set of experiments (10-50 reactions) for the target reaction (e.g., [2+2] cycloaddition) using your HTE platform. Measure and record the yields [27] [4].

- Molecular Descriptor Calculation: For all OPSs in both source and target sets, compute a unified set of molecular descriptors.

- DFT Descriptors: Perform geometry optimization at the B3LYP-D3/6-31G(d) level. Calculate HOMO/LUMO energies (EHOMO, ELUMO), vertical excitation energies (E(S1), E(T1)), singlet-triplet splitting (ΔE_ST), oscillator strength (f(S1)), and difference in dipole moments (ΔDM) using TD-DFT/TDA at the M06-2X/6-31+G(d) level with a PCM solvation model [27].

- SMILES-based Descriptors: Generate descriptors using toolkits like RDKit (e.g., RDKit, MACCSKeys, Mordred, Morgan Fingerprint). Apply Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce dimensionality if necessary [27].

- Model Training with Domain Adaptation:

- Implement the TrAdaBoost.R2 algorithm, an instance-based domain adaptation method.

- Use the source domain data as the primary, large training set.

- Use the small target domain dataset to re-weight the instances from the source domain during the boosting process, effectively "steering" the model towards the target task [27].

- Iterative Active Learning:

- Use the trained model to predict yields for a new batch of untested OPSs.

- Select the top-performing candidates or those with high uncertainty for experimental validation.

- Run the suggested experiments on the HTE platform.

- Add the new experimental results to the target training set and update the model.

- Repeat until satisfactory performance is achieved.

Protocol 2: Fine-Tuning a BERT Model for Virtual Screening of Materials

This protocol leverages large language models (LLMs) pretrained on massive chemical datasets and fine-tunes them for specific property prediction tasks, such as the HOMO-LUMO gap of organic photovoltaic materials [28].

Workflow Diagram: Fine-Tuning BERT for Material Properties

Materials and Reagents:

- Datasets:

- Software: Python with deep learning libraries (PyTorch/TensorFlow), chemical informatics toolkits (RDKit), and the

rxnfportransformerslibraries for handling chemical BERT models.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Obtain SMILES strings for the source and target molecules.

- For the target task, split the data into training, validation, and test sets (e.g., 80/10/10). Ensure the training set is small (e.g., a few hundred to a few thousand points) to simulate a data-scarce scenario.

- Model Pretraining (Optional):

- If a suitable pretrained model is not available, you can pretrain a BERT model from scratch. This involves training the model on millions of SMILES strings using a Masked Language Modeling (MLM) objective, where the model learns to predict randomly masked tokens in the SMILES strings [28].

- Model Fine-Tuning:

- Load the pretrained BERT model.

- Replace the final output layer with a regression (or classification) head suitable for your target property (e.g., HOMO-LUMO gap).

- Train the entire model on your small, labeled target dataset. Use a low learning rate (e.g., 1e-5) to avoid catastrophic forgetting of the general chemical knowledge learned during pretraining.

- Use the validation set for early stopping to prevent overfitting.

- Model Evaluation and Deployment:

- Evaluate the final fine-tuned model on the held-out test set using metrics like R².

- The model can now be used for the virtual screening of new material candidates, prioritizing those with predicted optimal properties for synthesis and testing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of the above protocols relies on a combination of computational and experimental resources. The following table lists key solutions and materials.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Transfer Learning in Reaction Optimization

| Category | Item / Solution | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Data Sources | USPTO Database | Provides millions of reaction SMILES for pretraining language models on general chemical language [28]. | Fine-tuning BERT for property prediction [28]. |

| ChEMBL / ZINC | Large databases of drug-like small molecules for expanding model's knowledge of chemical space [28]. | Pretraining for virtual screening. | |

| In-House HTE Data | High-quality, consistent dataset from a specific reaction class; ideal as a source domain [26]. | Domain adaptation between related catalytic reactions [27]. | |

| Computational Descriptors | DFT-Calculated Properties | Quantum-mechanical descriptors (HOMO/LUMO, E(S1), E(T1)) provide physical insight into catalytic activity [27]. | Modeling photocatalytic behavior of organic photosensitizers [27]. |

| Topological Indices / Fingerprints | Cost-effective molecular descriptors (e.g., RDKit, Morgan FP) for pretraining or modeling [27] [29]. | Pretraining GCNs with virtual databases; baseline models [29]. | |

| Software & Algorithms | Domain Adaptation (TrAdaBoost) | ML algorithm that reweights source data to improve performance on a related target task [27]. | Transferring knowledge from cross-coupling to cycloaddition [27]. |

| Bayesian Optimization | Efficiently navigates high-dimensional search spaces by balancing exploration and exploitation [30]. | Active learning for reaction condition optimization [30]. | |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Learns directly from molecular graph structures, avoiding manual descriptor design [29] [31]. | GraphRXN for reaction yield prediction [31]. |

Integrating transfer learning and fine-tuning into the reaction optimization workflow represents a significant advancement in data-driven organic synthesis. The protocols outlined herein provide a clear roadmap for leveraging existing chemical knowledge, thereby reducing experimental costs and accelerating development timelines. By starting with models pre-equipped with chemical intuition, researchers can make their active learning loops more efficient and effective, ultimately enabling the faster discovery of optimal reaction conditions for complex transformations, including those in pharmaceutical process development.

Self-driving laboratories (SDLabs) represent a paradigm shift in chemical research and development, integrating artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, and cloud computing to create fully automated experimentation systems. These systems leverage active machine learning to guide experimental decisions, dramatically accelerating the optimization of organic reactions and materials discovery. This case study examines the implementation of a self-driving laboratory framework for organic reaction optimization, detailing the core architecture, experimental protocols, and performance benchmarks that demonstrate orders-of-magnitude improvements over traditional approaches.

The traditional process of reaction optimization in organic chemistry remains a time-consuming, resource-intensive endeavor characterized by iterative trial-and-error experimentation. Chemists often face the challenge of navigating high-dimensional parameter spaces involving reagents, solvents, catalysts, concentrations, and processing conditions such as temperature and pressure. Current state-of-the-art methods frequently neglect relevant inter-correlations between these parameters, leading to suboptimal conditions and extended development timelines [32]. Self-driving laboratories address these limitations by implementing closed-loop systems where machine learning algorithms analyze experimental outcomes and autonomously decide which experiments to perform next, effectively learning the landscape of chemical reactivity with unprecedented efficiency.

Core Architecture of a Self-Driving Laboratory

The operational framework of a self-driving laboratory integrates several technological components into a cohesive, automated workflow. This architecture enables the continuous execution of experimentation cycles with minimal human intervention.

System Workflow and Components

The following diagram illustrates the core closed-loop workflow of a self-driving laboratory:

Figure 1. Closed-loop workflow of a self-driving laboratory for reaction optimization. The system continuously iterates between machine learning-guided prediction and robotic experimentation.

The workflow begins with researchers defining the optimization objectives and parameter spaces. The machine learning model, typically employing Bayesian optimization, then suggests promising reaction conditions based on available data. These suggestions are executed through robotic experimentation systems, which synthesize and analyze reactions autonomously. Resulting data undergoes processing and feature extraction before performance evaluation against the predefined objectives. Based on these results, the model updates its understanding of the chemical landscape and suggests subsequent experiments, creating an iterative loop until optimal conditions are identified [32] [6].

Key Technological Components