Active Learning in Chemistry Optimization: Accelerating Discovery from Molecules to Materials

Active learning (AL) is transforming computational and experimental chemistry by creating intelligent, self-improving workflows that drastically reduce resource consumption.

Active Learning in Chemistry Optimization: Accelerating Discovery from Molecules to Materials

Abstract

Active learning (AL) is transforming computational and experimental chemistry by creating intelligent, self-improving workflows that drastically reduce resource consumption. This article explores how AL iteratively selects the most informative data points for evaluation, bridging generative AI, molecular simulations, and real-world laboratory validation. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, we detail foundational principles, methodological applications in drug design and materials science, strategies for overcoming implementation challenges, and rigorous benchmarks that validate AL's performance against traditional methods. The synthesis of these facets reveals a powerful paradigm shift, enabling efficient exploration of vast chemical spaces and accelerating the optimization of molecules and materials.

The Core Principles of Active Learning: Building Smarter Chemical Workflows

In the field of chemistry and drug development, where experimental data is often scarce, costly to acquire, and resource-intensive to generate, active learning (AL) has emerged as a transformative machine learning approach. Active learning strategically selects the most informative data points for labeling and model training, dramatically reducing the experimental burden required to develop high-performance predictive models [1] [2]. This methodology is particularly valuable for navigating vast chemical spaces—including reaction conditions, catalyst formulations, and material properties—that would be prohibitively expensive to explore exhaustively through traditional experimental approaches [3] [4].

At its core, active learning operates through an iterative, closed-loop process that integrates data-driven model predictions with targeted experimental validation. By treating expensive computational methods or laboratory experiments as an "oracle" that provides ground-truth labels, active learning frameworks can efficiently converge toward optimal solutions, whether for synthesizing novel compounds, optimizing reaction yields, or discovering high-performance materials [5] [6] [4]. This technical guide examines the components, implementation, and application of the active learning loop within chemistry optimization research, providing researchers with both theoretical foundations and practical methodologies.

The Active Learning Loop: Core Components and Workflow

The active learning loop is a cyclical process comprising several interconnected stages that work together to optimize the learning efficiency of machine learning models. Unlike traditional supervised learning that uses a static, pre-defined dataset, active learning dynamically selects which data points would be most valuable to label next, creating an adaptive learning system [1].

Component Breakdown

Initialization: The process begins with a small, often randomly selected, set of labeled data points. In chemical contexts, this may consist of known reaction yields, previously characterized material properties, or existing catalyst performance data [3] [5]. This initial dataset serves as the starting point for model training.

Model Training: A machine learning model (such as Gaussian Process Regression, Random Forest, or Neural Networks) is trained on the current labeled dataset. This model learns the relationship between input parameters (e.g., chemical compositions, reaction conditions) and target outputs (e.g., yield, mechanical properties, catalytic activity) [1] [2].

Query Strategy: An acquisition function uses the trained model to evaluate unlabeled data points and select the most informative ones for subsequent labeling. Common strategies include uncertainty sampling, diversity sampling, and expected improvement [1] [5].

Human-in-the-Loop/Oracle Consultation: The selected data points are presented to a human expert or an automated "oracle" for labeling. In chemical research, this typically involves performing targeted experiments or high-fidelity simulations to obtain the requested data [6] [4].

Model Update: The newly labeled data points are incorporated into the training set, and the model is retrained on this expanded dataset. The updated model benefits from the additional information and typically shows improved performance [1].

Iteration: Steps 3-5 are repeated iteratively until a stopping criterion is met, such as performance convergence, depletion of resources, or achievement of target metrics [1] [5].

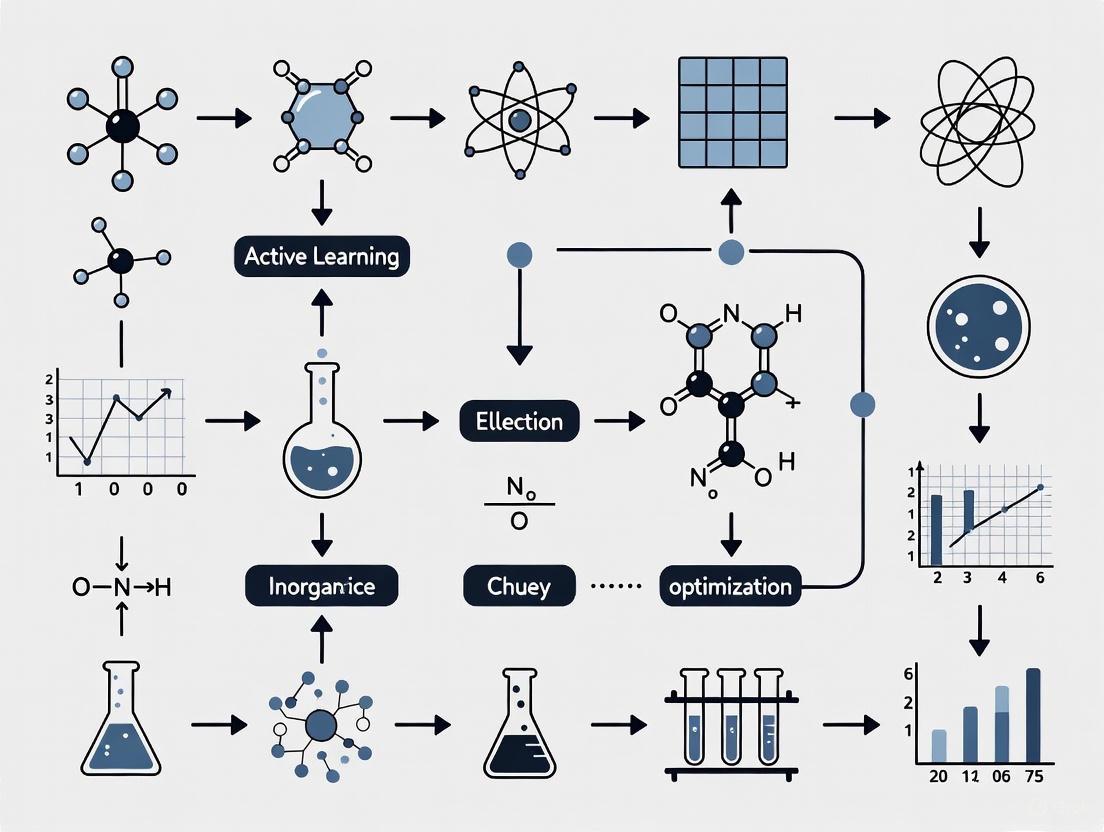

Visualizing the Active Learning Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete active learning loop as implemented in chemical optimization research:

Figure 1: Active Learning Loop in Chemical Research. This workflow demonstrates the iterative process of model training, data selection, and experimental validation used to efficiently explore chemical spaces.

Query Strategies: The Intelligence Behind Data Selection

Query strategies form the decision-making engine of active learning systems, determining which unlabeled data points would provide the maximum information gain to the model. Different strategies employ distinct philosophical approaches to data selection, each with particular advantages for chemical applications.

Uncertainty Sampling

Uncertainty sampling selects instances where the model is most uncertain about its predictions, typically targeting regions of the chemical space where the model has low confidence [1]. In classification tasks, this might involve selecting data points with predicted probabilities closest to 0.5. For regression tasks common in chemical optimization (e.g., predicting reaction yields or material properties), uncertainty is often quantified using the standard deviation of predictions from an ensemble of models or through Bayesian methods like Gaussian Processes [2].

Chemical Application Example: In optimizing reaction conditions for deoxyfluorination, uncertainty sampling would prioritize testing reactions where the yield prediction has high variance, thereby refining the model in previously unexplored regions of the condition space [3].

Diversity Sampling

Diversity sampling aims to select a representative set of data points that broadly covers the input space. This approach helps prevent the model from over-exploring specific regions and ensures comprehensive coverage of the chemical space [1]. Techniques include clustering-based selection or maximizing the minimum distance between selected points.

Chemical Application Example: When exploring a multi-component catalyst system like FeCoCuZr, diversity sampling ensures that different compositional regions are adequately represented in the training data, preventing premature convergence to local optima [4].

Hybrid and Advanced Strategies

Sophisticated AL implementations often combine multiple strategies to balance exploration (diversity) and exploitation (uncertainty). The Pareto Active Learning framework employs expected hypervolume improvement (EHVI) to simultaneously optimize multiple objectives, such as maximizing strength and ductility in material design [5]. Similarly, the SIFT algorithm for fine-tuning language models addresses redundancy in data selection by optimizing for overall information gain rather than just similarity [7].

Table 1: Query Strategies in Chemical Active Learning

| Strategy | Mechanism | Chemical Application Example | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uncertainty Sampling | Selects points with highest prediction uncertainty | Identifying ambiguous reaction conditions in deoxyfluorination [3] | Rapidly improves model in poorly understood regions |

| Diversity Sampling | Maximizes coverage of chemical space | Ensuring broad composition coverage in FeCoCuZr catalyst screening [4] | Prevents over-specialization and explores global space |

| Expected Improvement | Balances predicted performance and uncertainty | Optimizing laser power and scan speed in Ti-6Al-4V alloy manufacturing [5] | Directly targets performance improvement |

| Query-by-Committee | Selects points with highest disagreement among model ensemble | Materials property prediction with multiple ML algorithms [2] | Reduces model bias and variance |

| Multi-Objective EHVI | Optimizes Pareto front for multiple targets | Simultaneously maximizing strength and ductility in alloys [5] | Addresses competing objectives common in materials design |

Experimental Protocols in Chemical Active Learning

Implementing active learning in chemical research requires careful experimental design and execution. The following protocols outline key methodological considerations for successful AL deployment.

Dataset Construction and Feature Representation

Chemical active learning begins with defining the relevant chemical space and representing chemical entities in machine-readable formats.

Protocol: Feature Engineering for Chemical Reactions

- Reactant and Condition Encoding: Represent chemical reactions using concatenated one-hot encoded (OHE) vectors for each reactant type and condition parameter [3]. For example, a reaction with two reactants and three condition parameters would be represented as:

[ra1, ra2, ..., ca1, ca2, ca3]. - Descriptor Calculation: Alternatively, use chemical descriptors such as molecular fingerprints, electronic properties, or structural features when available.

- Data Normalization: Apply standard scaling to continuous parameters to ensure balanced influence across features with different units and scales.

Case Example: In deoxyfluorination reaction optimization, reactions were encoded using OHE vectors of length 37 (for reactants) + 4 (first condition parameter) + 5 (second condition parameter) = 46 dimensions [3].

Oracle Implementation and Experimental Validation

The "oracle" in chemical AL provides ground-truth labels through experimentation or high-fidelity simulation.

Protocol: High-Throughput Experimental Validation

- Batch Selection: Using the query strategy, select a batch of candidate experiments for each AL cycle. Batch sizes typically range from 2-6 experiments per cycle in resource-intensive chemical synthesis [5] [4].

- Automated Synthesis: For materials and catalyst optimization, employ automated synthesis platforms such as liquid-handling robots or high-throughput synthesis rigs.

- Characterization and Testing: Perform standardized characterization and performance testing. For catalytic systems, this includes activity, selectivity, and stability assessments under controlled conditions [4].

- Quality Control: Implement replicate experiments and control samples to ensure data reliability.

Case Example: In developing high-performance Ti-6Al-4V alloys, each AL iteration involved manufacturing two new alloy specimens with selected process parameters, followed by tensile testing to determine ultimate tensile strength and total elongation [5].

Model Training and Uncertainty Quantification

Accurate model predictions with reliable uncertainty estimates are essential for effective AL.

Protocol: Gaussian Process Regression for Chemical AL

- Kernel Selection: Choose appropriate covariance kernels based on the expected smoothness of the target property landscape. The Matérn kernel is often preferred for chemical applications.

- Hyperparameter Optimization: Maximize the marginal likelihood to optimize kernel hyperparameters.

- Predictive Distribution: For each unlabeled point ( x^* ), compute the predictive mean ( \mu(x^) ) and variance ( \sigma^2(x^) ).

- Acquisition Function Calculation: Use the predictive distribution to compute acquisition function values (e.g., expected improvement, upper confidence bound) for all candidates.

Case Example: In catalyst optimization for higher alcohol synthesis, Gaussian Process models with Bayesian optimization were trained using molar content values of four elements (Fe, Co, Cu, Zr) to predict space-time yields of higher alcohols (STYHA) [4].

Case Study: Optimizing High-Performance Ti-6Al-4V Alloys

The application of Pareto Active Learning to develop Ti-6Al-4V alloys with superior strength and ductility demonstrates the power of AL in materials science [5].

Experimental Design and Workflow

The research aimed to identify optimal laser powder bed fusion (LPBF) process parameters and heat-treatment conditions to overcome the traditional strength-ductility trade-off in additive manufacturing.

Initial Dataset and Parameter Space:

- Labeled Data: 119 combinations of LPBF parameters and post-heat treatment conditions from previous studies

- Unlabeled Pool: 296 unexplored combinations of laser power, scan speed, and heat treatment parameters

- Objectives: Maximize both Ultimate Tensile Strength (UTS) and Total Elongation (TE)

Active Learning Implementation:

- Surrogate Model: Gaussian Process Regressor (GPR) trained on initial 119 data points

- Acquisition Function: Expected Hypervolume Improvement (EHVI) to optimize the Pareto front between UTS and TE

- Batch Selection: 2 new experiments per AL cycle

- Validation: Tensile testing of manufactured specimens following standardized protocols

Table 2: Key Results from Ti-6Al-4V Active Learning Optimization

| Metric | Initial Best Performance | AL-Optimized Performance | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ultimate Tensile Strength | ~1100 MPa | 1190 MPa | 8.2% increase |

| Total Elongation | ~8% | 16.5% | 106% increase |

| Parameter Combinations Evaluated | 119 (pre-AL) | 18 (AL-guided) | 85% reduction in experimentation |

| Performance Balance | Strength-ductility trade-off | Simultaneous improvement | Overcoming traditional compromise |

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Ti-6Al-4V Alloy Active Learning Study

| Material/Reagent | Specification | Function in Study |

|---|---|---|

| Ti-6Al-4V Powder | Gas-atomized, 15-53 μm particle size | Primary alloy material for LPBF process |

| Argon Gas | High purity (99.998%) | Inert atmosphere during printing to prevent oxidation |

| Heat Treatment Furnace | Capable of 25-1050°C with controlled atmosphere | Post-processing to modify microstructure |

| Tensile Testing Machine | ASTM E8 standard | Mechanical property characterization |

| Metallographic Equipment | Polishing, etching, microscopy | Microstructural analysis and validation |

The AL framework successfully identified processing conditions that produced Ti-6Al-4V alloys with unprecedented combinations of strength (1190 MPa) and ductility (16.5% elongation), demonstrating that active learning can overcome fundamental materials trade-offs that have limited traditional development approaches [5].

Advanced Implementations and Computational Tools

As active learning adoption grows in chemical research, specialized computational tools and advanced implementations have emerged to address domain-specific challenges.

Parallel Active Learning (PAL)

The PAL framework addresses limitations of sequential AL implementations by enabling parallel, asynchronous execution of AL components [6].

Key Features of PAL:

- Modular Architecture: Five core kernels (prediction, generator, training, oracle, controller) operate asynchronously

- MPI-based Communication: Enables deployment on high-performance computing clusters

- Automated Workflow: Minimizes human intervention during execution

- Flexibility: Supports various ML models and uncertainty quantification methods

Chemical Application: PAL has been applied to develop machine-learned potentials for biomolecular systems, excited-state dynamics of molecules, and simulations of inorganic clusters, demonstrating substantially reduced computational overhead and improved scalability [6].

Integration with Automated Machine Learning (AutoML)

Combining AL with AutoML creates powerful frameworks for data-efficient chemical discovery, particularly when the optimal model architecture for a given problem is unknown [2].

Implementation Considerations:

- Model Flexibility: The AL strategy must remain effective even as the AutoML system switches between different model families (linear models, tree-based ensembles, neural networks)

- Uncertainty Quantification: Model-agnostic uncertainty estimation methods are required to maintain consistent acquisition function performance

- Benchmarking: Comprehensive evaluation of 17 AL strategies within AutoML revealed that uncertainty-driven (LCMD, Tree-based-R) and diversity-hybrid (RD-GS) strategies outperform geometry-only heuristics, particularly in early acquisition stages [2]

Active learning represents a paradigm shift in chemical and materials research, transforming the scientific discovery process from sequential experimentation to intelligent, data-driven exploration. By implementing the active learning loop—with appropriate query strategies, robust experimental validation, and iterative model refinement—researchers can dramatically reduce the time and resources required to optimize complex chemical systems.

The continued development of specialized tools like PAL for parallel execution [6], integration with AutoML for model selection [2], and multi-objective optimization frameworks [5] will further enhance the capability of active learning to tackle increasingly complex challenges in chemistry and drug development. As these methodologies mature, active learning is poised to become an indispensable component of the modern chemical researcher's toolkit, accelerating the discovery and optimization of novel molecules, materials, and synthetic pathways.

Uncertainty Quantification, Oracles, and Exploration Strategies in Chemical Optimization

Active learning (AL) has emerged as a transformative paradigm in chemical and materials research, enabling the rapid discovery of new molecules and materials by strategically guiding expensive experiments and computations. This guide details the three core technical components that underpin an effective active learning cycle: Uncertainty Quantification for model self-assessment, Oracles for property evaluation, and Exploration Strategies for navigating chemical space. Framed within a broader thesis on chemistry optimization, these components form an iterative, self-improving system that efficiently balances the trade-off between resource investment and information gain, thereby accelerating the transition from initial design to validated candidate.

Key Component 1: Uncertainty Quantification

Uncertainty Quantification (UQ) provides the critical self-assessment mechanism for the machine learning models used in active learning cycles. It informs the algorithm about the confidence of its predictions, guiding the selection of the most informative samples for oracle evaluation.

In the context of chemical optimization, uncertainty arises from several distinct sources, as defined in studies on machine-learned interatomic potentials [8]:

- Aleatoric uncertainty stems from inherent noise in the data. It is negligible when using deterministic data sources like consistent density functional theory (DFT) calculations.

- Epistemic uncertainty arises from a lack of data in certain regions of chemical space. It can be minimized by using large, diverse training datasets.

- Misspecification uncertainty occurs when the model itself is incapable of perfectly fitting the underlying data, even with optimal parameters. This is a dominant source of error when using underparameterized models or those with constrained complexity for performance reasons [8].

Techniques for Quantifying Uncertainty

Different UQ techniques are employed based on the model architecture and the primary source of uncertainty being targeted. The table below summarizes prominent UQ methods and their applications in chemical research.

Table 1: Uncertainty Quantification Techniques in Chemical Research

| Technique | Core Principle | Representative Application | Key Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ensemble Methods [8] | Trains multiple models (e.g., with different initializations); uses prediction variance as uncertainty. | Predicting formation energies and defect properties in tungsten with ML interatomic potentials. | Provides an effective sample of plausible parameters; robust for neural network-based models. |

| Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) [3] | Provides a natural posterior variance for predictions based on kernel similarity to training data. | Classifying reaction success in high-throughput synthesis campaigns. | Intrinsically well-suited for uncertainty qualification and active learning. |

| Misspecification-Aware UQ [8] | Quantifies error from model imperfection, where no single parameter set can fit all data. | Propagating errors to predict phase and defect properties in materials. | Crucial for underparameterized models; provides conservative, reliable error bounds. |

| LoUQAL Framework [9] | Leverages cheaper, low-fidelity quantum calculations to inform the UQ of higher-fidelity models. | Predicting excitation energies and ab initio potential energy surfaces. | Reduces the number of expensive iterations required for model training. |

| Robust UQ for SAR [10] | A simple, robust method designed to identify poorly predicted compounds in steep structure-activity relationship (SAR) regions. | Exploratory active learning for molecular activity prediction. | Addresses the challenge where similar structures have large property differences. |

Key Component 2: Oracles

Oracles are computational or experimental methods that provide ground-truth (or high-fidelity) evaluations of a proposed molecule or material's properties. They serve as the objective function for the optimization.

Types of Oracles and Their Fidelity-Cost Trade-Offs

The choice of oracle is a balance between computational cost and predictive accuracy. Multi-fidelity frameworks strategically combine oracles to optimize this trade-off [11].

Table 2: Oracle Types in Chemical and Drug Discovery Research

| Oracle Type | Typical Methods | Fidelity & Cost | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemoinformatic Oracles [12] | Drug-likeness (QED), Synthetic Accessibility (SA) filters, Structural similarity. | Low cost, Medium-High fidelity for their specific, rule-based tasks. | Initial filtering to ensure generated molecules are viable and novel. |

| Physics-based (Low-Fidelity) [12] [13] [11] | Molecular Docking (e.g., AutoDock), Hybrid ML/MM (Machine Learning/Molecular Mechanics). | Moderate cost, Low-Medium fidelity for binding affinity. | High-throughput screening of thousands to millions of molecules in early cycles. |

| Physics-based (High-Fidelity) [12] [11] | Absolute Binding Free Energy (ABFE) simulations, Molecular Dynamics (MD) with FEP. | High cost (hours to days per molecule), High fidelity. | Final-stage validation and ranking of top candidate compounds. |

| Experimental Oracles [5] [13] | High-throughput synthesis and characterization, Fluorescence-based bioassays, Tensile testing. | Very high cost, Highest fidelity (real-world data). | Ultimate validation of computationally discovered leads. |

The Multi-Fidelity Paradigm

Modern AL frameworks increasingly move beyond single oracles to multi-fidelity approaches. For example, the MF-LAL (Multi-Fidelity Latent space Active Learning) framework uses a hierarchical latent space to integrate data from low-fidelity (docking) and high-fidelity (binding free energy) oracles [11]. This allows the model to generate compounds optimized for the most accurate metric by first pre-screening with cheaper methods, dramatically improving efficiency.

Key Component 3: Exploration Strategies

Exploration Strategies, often implemented through acquisition functions, determine how the AL algorithm selects the next set of experiments or calculations. They manage the fundamental exploration-exploitation trade-off.

Common Acquisition Functions

- Exploitation: Selects points where the surrogate model predicts the best properties. This strategy risks getting stuck in local optima [14].

- Exploration: Selects points where the model's uncertainty is highest. This improves the model's global knowledge but may be inefficient for pure optimization [14].

- Expected Improvement (EI): Balances exploration and exploitation by favoring points likely to improve upon the current best solution.

- Expected Hypervolume Improvement (EHVI): A state-of-the-art method for multi-objective optimization. It measures the expected growth in the volume of the Pareto front, effectively balancing multiple competing properties like strength and ductility in alloys [5] [14].

Hybrid and Customized Strategies

Researchers often develop hybrid strategies tailored to their specific challenges:

- Combined Explore-Exploit: A linear combination of exploration and exploitation terms, weighted by a parameter

α[3]. - Sequential Strategy: The unified AL framework for photosensitizer design employs a strategy that first prioritizes chemical diversity (exploration) before focusing on target regions (exploitation) in later cycles [15].

- Knowledge-Based Acquisition: Incorporates domain knowledge, such as using protein-ligand interaction profiles (PLIP) from crystallographic data to score compound designs [13].

Integrated Experimental Protocols

This section details the methodology from two landmark studies that successfully integrated all three key components.

Protocol 1: Optimizing Drug Molecules for CDK2 and KRAS

This protocol from a Nature Communications Chemistry study [12] demonstrates a generative AI workflow with nested AL cycles for de novo drug design.

1. Data Representation and Initial Training:

- Represent molecules as tokenized SMILES strings converted into one-hot encoding vectors.

- Train a Variational Autoencoder (VAE) first on a general molecular dataset, then fine-tune it on a target-specific set (e.g., known CDK2 inhibitors).

2. Nested Active Learning Cycles:

- Inner AL Cycle (Cheminformatics Oracle):

- Generation: Sample the VAE to generate new molecules.

- Evaluation: Use cheminformatic oracles to evaluate drug-likeness, synthetic accessibility (SA), and novelty (dissimilarity from training set).

- Fine-tuning: Molecules passing thresholds are added to a temporal set used to fine-tune the VAE. This cycle repeats to refine chemical properties.

- Outer AL Cycle (Physics-based Oracle):

- Evaluation: After several inner cycles, evaluate molecules from the temporal set using a physics-based oracle (molecular docking).

- Fine-tuning: Molecules with favorable docking scores are promoted to a permanent set used to fine-tune the VAE. The process then returns to inner cycles.

3. Candidate Selection and Validation:

- Apply stringent filtration, including advanced molecular simulations (PELE, Absolute Binding Free Energy) to assess binding interactions.

- Synthesize top-ranking compounds and validate activity via in vitro bioassays. This protocol yielded 8 active CDK2 inhibitors, including one with nanomolar potency [12].

Protocol 2: Discovering Complementary Reaction Conditions

This protocol from Digital Discovery [3] uses AL to find small sets of reaction conditions that collectively cover a broad reactant space.

1. Problem Formulation and Dataset Construction:

- Define a reactant space (e.g., 37 substrates) and a condition space (e.g., 4 catalysts × 5 solvents).

- Construct a complete dataset of reaction yields for all reactant-condition combinations, using a binary "success" label (yield ≥ cutoff).

2. Active Learning Loop:

- Initialization: Select an initial batch of reactions using Latin Hypercube Sampling.

- Iteration Cycle:

- Experiment & Training: Perform experiments to determine success/failure; train a classifier (e.g., Gaussian Process Classifier or Random Forest) on all accumulated data.

- Prediction: Use the classifier to predict the probability of success (

ϕ_r,c) for all possible reactant-condition pairs. - Acquisition: Select the next batch of reactions using a combined acquisition function:

Combined_r,c = (α) * Explorer,c + (1-α) * Exploit_r,c- Where

Explorer,cfavors high uncertainty, andExploit_r,cfavors conditions that complement known successful conditions for difficult reactants.

- Evaluation: After each iteration, identify the best set of complementary conditions via combinatorial enumeration and calculate its coverage of the reactant space.

3. Outcome:

- The AL algorithm efficiently identifies a small set of 2-3 reaction conditions that together achieve high coverage (e.g., >60%) of the reactant space, significantly outperforming the use of any single general condition [3].

Visualizing Active Learning Workflows

Nested Active Learning for Drug Design

The following diagram illustrates the integrated, iterative workflow for generative molecular design, combining generative AI with active learning [12].

Multi-Fidelity Active Learning

The diagram below outlines the MF-LAL framework, which integrates oracles of varying cost and accuracy to efficiently generate high-fidelity candidates [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

This table catalogs key computational tools and resources that form the essential "reagents" for building an active learning pipeline for chemical optimization.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Active Learning |

|---|---|---|

| FEgrow [13] | Software Package | Builds and optimizes congeneric ligand series in protein binding pockets using hybrid ML/MM methods; automates library generation for AL. |

| Gaussian Process Regressor (GPR) [5] [3] | Surrogate Model | Serves as a probabilistic surrogate model providing native uncertainty estimates for acquisition functions like EHVI. |

| Variational Autoencoder (VAE) [12] | Generative Model | Learns a continuous latent representation of molecules, enabling generation of novel compounds and smooth property optimization. |

| ML-xTB Pipeline [15] | Quantum Chemistry Calculator | Provides rapid, DFT-level accuracy for calculating molecular properties (e.g., excitation energies), used as a cost-effective labeling oracle. |

| Enamine REAL Database [13] | Chemical Database | A vast source of purchasable compounds used to "seed" the chemical search space, ensuring synthetic tractability of designed molecules. |

| AutoDock [11] | Docking Software | A widely used, low-fidelity physics-based oracle for high-throughput virtual screening of protein-ligand binding affinity. |

| OpenMM [13] | Molecular Simulation Engine | Performs energy minimization and molecular dynamics simulations for pose optimization and binding free energy calculations. |

This technical guide explores the architecture of modular active learning (AL) systems, with a specific focus on the Parallel Active Learning (PAL) framework and its kernel-based design. Within chemistry optimization research, active learning enables more efficient molecular discovery by strategically selecting the most informative data points for experimental or computational validation. Traditional AL workflows often suffer from sequential execution and significant human intervention, limiting their scalability and efficiency. PAL addresses these limitations through a parallel, modular kernel architecture that facilitates simultaneous data generation, labeling, model training, and prediction. This whitepaper provides an in-depth analysis of PAL's architectural components, presents quantitative performance comparisons, details experimental protocols for chemical applications, and offers implementation guidelines for research teams. By examining PAL within the context of molecular optimization and drug discovery, we demonstrate how properly architected AL systems can dramatically accelerate research cycles while reducing computational costs.

Active learning represents a paradigm shift in computational chemistry and drug discovery, moving from passive model training to iterative, strategic data acquisition. In chemical optimization research, the primary challenge lies in the vastness of chemical space and the significant computational or experimental costs associated with evaluating molecular properties. Traditional machine learning approaches require large, representative datasets that are expensive to acquire, whereas active learning strategically selects the most informative molecules for evaluation, maximizing knowledge gain while minimizing resources [16].

The fundamental AL cycle in chemistry involves: (1) training an initial model on available data, (2) using the model to screen candidate molecules, (3) selecting candidates based on specific criteria (e.g., uncertainty, expected improvement), (4) obtaining ground-truth measurements for selected candidates, and (5) updating the model with new data. This cycle repeats until satisfactory performance is achieved or resources are exhausted. However, conventional implementations execute these steps sequentially, leading to substantial idle time for computational resources and researchers [17].

Active learning has demonstrated particular value in early-stage drug discovery projects where training data is limited and model exploitation might otherwise lead to analog identification with limited scaffold diversity [16]. By focusing on the most informative experiments, AL approaches enable more efficient exploration of chemical space while de-risking the optimization process.

PAL Architectural Framework

Core Kernel Architecture

PAL employs a sophisticated five-kernel architecture that enables parallel execution of AL components through efficient communication via Message Passing Interface (MPI). This design decouples the major functions of an active learning workflow, allowing them to operate concurrently and asynchronously [17] [18].

Table: PAL Kernel Functions and Responsibilities

| Kernel Name | Primary Function | Chemistry Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Prediction Kernel | Provides ML model inferences for generated inputs | Predicts energies and forces for molecular geometries |

| Generator Kernel | Explores target space by producing new data instances | Performs molecular dynamics steps or generates new molecular geometries |

| Oracle Kernel | Sources ground truth labels for selected instances | Executes quantum chemical calculations (e.g., DFT) for accurate energy/force labels |

| Training Kernel | Retrains ML models using newly labeled data | Updates machine-learned potentials with new quantum chemistry data |

| Controller Kernel | Manages workflow coordination and inter-kernel communication | Orchestrates the overall active learning process and resource allocation |

The kernel-based architecture creates a highly modular system where each component can be customized independently. This flexibility allows researchers to substitute different machine learning models, exploration strategies, or oracle implementations without redesigning the entire workflow [17]. The controller kernel manages communication between all components, aggregating predictions from multiple models, distributing results to generators, and routing data requiring labeling to the appropriate oracle processes.

Parallelization and Workflow Management

A key innovation in PAL is its parallel execution model, which addresses critical bottlenecks in traditional sequential AL implementations. Where conventional systems execute data generation, labeling, model training, and prediction in sequence, PAL enables these operations to occur simultaneously through its decoupled kernel design [17].

The diagram below illustrates PAL's parallel workflow and how its kernels interact to accelerate the active learning process:

This parallel architecture demonstrates significant performance improvements over sequential approaches. In molecular dynamics simulations using machine-learned potentials, PAL enables continuous exploration of configuration space while simultaneously labeling uncertain configurations and retraining models in the background. The generator kernel can propagate multiple molecular dynamics trajectories concurrently, while the prediction kernel provides energy and force calculations, and the oracle kernel computes quantum mechanical references for structures with high uncertainty [17].

Active Learning in Chemistry Optimization

Chemical Space Exploration Strategies

In chemistry optimization, active learning enables efficient navigation of high-dimensional molecular space through strategic experiment selection. The generator kernel in PAL-like systems produces new molecular candidates through various sampling strategies:

- Molecular Dynamics Simulations: Propagation of atomic trajectories using machine-learned potentials, with uncertainty quantification identifying configurations requiring quantum mechanical validation [17]

- Genetic Algorithms: Evolutionary operations (mutation, crossover) applied to molecular representations to generate novel candidates

- Monte Carlo Methods: Stochastic sampling of molecular space with acceptance criteria based on predicted properties or uncertainty measures

The controller kernel employs uncertainty quantification techniques to identify which generated structures require oracle validation. Common approaches include query-by-committee (where disagreement between ensemble models indicates uncertainty), Bayesian neural networks, and Gaussian process regression with built-in uncertainty estimates [17] [18].

Advanced Active Learning Variants

Beyond standard uncertainty sampling, specialized AL approaches have emerged for chemical applications. The ActiveDelta method leverages paired molecular representations to predict property improvements rather than absolute values [16]. This approach addresses limitations of standard exploitative active learning in low-data regimes common to early-stage drug discovery projects.

The diagram below illustrates how ActiveDelta differs from standard active learning in molecular optimization:

ActiveDelta implementations have demonstrated superior performance in identifying potent inhibitors across 99 Ki benchmarking datasets, achieving both higher potency and greater scaffold diversity compared to standard active learning approaches [16]. This pairing approach benefits from combinatorial data expansion, particularly valuable in the low-data regimes typical of early-stage discovery projects.

Quantitative Performance Analysis

Computational Efficiency Metrics

The parallel architecture of PAL demonstrates significant performance advantages over sequential active learning implementations. Benchmark studies across diverse chemical applications show substantial reductions in computational overhead and improved resource utilization [17].

Table: Performance Comparison of Sequential vs. Parallel Active Learning

| Metric | Sequential AL | PAL Architecture | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPU Utilization | 15-30% | 70-90% | 3-4x increase |

| Total Workflow Time | 100% (baseline) | 25-40% | 60-75% reduction |

| Data Generation Throughput | 1x | 3-5x | 3-5x increase |

| Model Retraining Frequency | After each AL cycle | Continuous in background | Near-real-time updates |

| Oracle Query Efficiency | 65-80% informative | 85-95% informative | 20-30% improvement |

These efficiency gains translate directly to accelerated research cycles in chemical optimization. In molecular dynamics applications, PAL achieves near-linear scaling on high-performance computing systems, enabling simultaneous exploration of multiple reaction pathways or conformational states [17].

Chemical Optimization Performance

In practical drug discovery applications, active learning frameworks have demonstrated remarkable efficiency in identifying optimized compounds. The ActiveDelta approach, when applied to 99 Ki benchmarking datasets with simulated time splits, showed consistent advantages over standard methods [16].

Table: ActiveDelta Performance in Molecular Potency Optimization

| Method | Most Potent Compounds Identified | Scaffold Diversity | Prediction Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| ActiveDelta Chemprop | 87.3 ± 4.2 | High | 0.81 ± 0.05 |

| Standard Chemprop | 72.1 ± 5.7 | Medium | 0.69 ± 0.07 |

| ActiveDelta XGBoost | 83.5 ± 3.9 | High | 0.78 ± 0.06 |

| Standard XGBoost | 70.8 ± 6.2 | Medium | 0.65 ± 0.08 |

| Random Forest | 68.3 ± 7.1 | Low | 0.62 ± 0.09 |

The performance advantage of ActiveDelta was particularly pronounced in early iterations with limited data, highlighting its value in the low-data regimes typical of project initiation [16]. This approach also identified more chemically diverse inhibitors in terms of Murcko scaffolds, reducing the risk of analog bias in optimization campaigns.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Implementation Framework for Chemical Applications

Implementing PAL for chemistry optimization requires careful configuration of each kernel component:

Prediction Kernel Configuration:

- Select appropriate machine learning architectures for chemical prediction tasks (e.g., message-passing neural networks for molecular properties, SchNet or NequIP for molecular energies and forces)

- Implement ensemble methods or Bayesian approaches for uncertainty quantification

- Configure model update frequency from training kernel (typically after specified training epochs)

Generator Kernel Setup:

- Implement molecular sampling strategies appropriate to the chemical space (e.g., molecular dynamics, genetic algorithms, Monte Carlo)

- Define criteria for trajectory management based on uncertainty signals from controller

- Configure parallel instance management for high-throughput exploration

Oracle Kernel Implementation:

- Interface with computational chemistry software (e.g., Gaussian, ORCA, Quantum ESPRESSO) for quantum mechanical calculations

- Or integrate with experimental data acquisition systems for wet-lab validation

- Implement error handling and recovery for failed calculations

Training Kernel Specification:

- Configure training parameters (learning rate, batch size, early stopping)

- Implement data management for expanding training sets

- Define model checkpointing and versioning protocols

Controller Kernel Orchestration:

- Implement uncertainty quantification algorithms (standard deviation, entropy, query-by-committee)

- Configure communication protocols between kernels

- Define convergence criteria for stopping the AL workflow

ActiveDelta Protocol for Potency Optimization

For drug discovery applications, the ActiveDelta methodology follows this detailed protocol:

Initial Dataset Preparation:

- Curate initial compound set with measured binding affinity (Ki) values

- Remove duplicate structures and standardize molecular representations

- Split data into initial training set (2 random compounds) and learning set (remaining compounds)

Molecular Representation:

- Generate molecular features (e.g., Morgan fingerprints with radius 2, 2048 bits)

- For deep learning approaches, use graph representations with atom and bond features

ActiveDelta Training:

- Create all possible pairwise combinations from training set

- Train model to predict property differences between paired compounds

- For Chemprop implementation: use two-molecule D-MPNN architecture with numberofmolecules=2

- For XGBoost implementation: concatenate fingerprint representations of molecule pairs

Iterative Selection:

- Identify the most potent compound in current training set

- Create pairs between this best compound and all compounds in learning set

- Use trained model to predict improvement for each pair

- Select the compound with highest predicted improvement

- Acquire experimental data for selected compound

- Add to training set and repeat from step 3

This protocol was validated across 99 Ki datasets with three independent replicates per dataset, demonstrating statistically significant improvements over standard active learning (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p<0.001) [16].

Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing advanced active learning frameworks requires specific computational tools and libraries. The following table details essential components for establishing PAL-like systems in chemical research environments.

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Active Learning Implementation

| Component | Representative Solutions | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active Learning Framework | PAL Library [17], DeepChem | Provides core infrastructure for parallel AL workflows | General chemical space exploration |

| Machine Learning Models | SchNet [17], NequIP [18], Chemprop [16] | Property prediction and uncertainty quantification | Molecular property prediction, force fields |

| Molecular Representations | RDKit, Mordred | Generates molecular features and descriptors | Compound screening and optimization |

| Quantum Chemistry Oracles | Gaussian, ORCA, DFTB+ | Provides ground-truth labels for electronic properties | Molecular dynamics with ML potentials |

| Parallelization Infrastructure | MPI for Python [17], Dask | Enables distributed computing across HPC resources | Large-scale chemical space exploration |

| Uncertainty Quantification | Ensemble methods, Bayesian neural networks | Identifies informative samples for labeling | Strategic experiment selection |

| Molecular Dynamics Engines | ASE, LAMMPS with ML plugin | Explores molecular configuration space | Conformational sampling, reaction discovery |

Modular architectural frameworks like PAL represent a significant advancement in active learning methodology for chemistry optimization research. By decoupling core components into specialized kernels and enabling parallel execution, these systems address critical bottlenecks in traditional sequential approaches. The PAL architecture demonstrates that properly designed computational frameworks can achieve substantial improvements in resource utilization, workflow efficiency, and overall research productivity.

In the context of chemical research and drug discovery, the kernel-based design provides the flexibility needed to adapt to diverse research scenarios—from molecular dynamics with machine-learned potentials to compound potency optimization. Specialized approaches like ActiveDelta further enhance the value of active learning by addressing specific challenges in molecular optimization, particularly in low-data regimes where conventional methods struggle.

The quantitative results presented in this whitepaper demonstrate that parallel active learning systems can reduce total workflow time by 60-75% while improving data quality and model performance. For research organizations engaged in molecular discovery and optimization, investment in these architectural frameworks offers the potential to dramatically accelerate research cycles while more efficiently utilizing computational and experimental resources.

As active learning continues to evolve, we anticipate further specialization of kernel components and tighter integration with experimental automation systems. The principles outlined in this guide provide a foundation for research teams to implement and extend these architectures, advancing both computational methodology and chemical discovery.

Active learning (AL) has emerged as a transformative paradigm in computational chemistry and drug discovery, enabling the iterative construction of accurate machine learning models while minimizing costly data acquisition. The core principle of AL involves strategically selecting the most informative data points for labeling, thereby enhancing model performance with optimal resource utilization. However, the implementation of AL in chemical research presents profound computational challenges. The exploration of complex chemical spaces, such as vast molecular conformations or intricate potential energy surfaces, requires an immense number of energy and force evaluations using quantum mechanical methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT), which are computationally prohibitive when executed sequentially. High-performance computing (HPC) resolves this bottleneck through parallel and distributed computing frameworks, transforming AL from a sequential process into a highly concurrent workflow. This enables simultaneous data generation, model training, and quantum mechanical labeling across thousands of processing units, reducing resource time from months to hours and making previously intractable chemical optimization problems feasible.

Architectural Frameworks for Parallel Active Learning

The integration of HPC with AL has led to the development of specialized software architectures designed to leverage parallel and distributed computing resources efficiently. These frameworks typically decompose the AL workflow into modular components that can operate asynchronously, coordinated by a central manager. The design ensures that computational resources are continuously engaged, avoiding idle time that would occur in sequential workflows where data generation, labeling, and model training happen one after another.

Table: Key Software Frameworks for Parallel Active Learning in Chemistry

| Framework Name | Core Parallelization Strategy | Primary Application Domain | Key HPC Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| PAL [6] | MPI-based kernels for prediction, generation, and training | Machine-learned potentials | Decoupled modules enabling simultaneous exploration, labeling, and training |

| aims-PAX [19] | Multi-trajectory sampling with parallel DFT calculations | Molecular dynamics & materials science | Automated, parallel exploration of configuration space |

| SDDF [20] | Volunteer computing across global personal computers | Molecular property prediction | CPU-only, distributed task distribution via a message broker |

| PALIRS [21] | Ensemble-based uncertainty quantification | Infrared spectra prediction | Parallel molecular dynamics at multiple temperatures |

The Kernel-Based Architecture of PAL

The PAL framework exemplifies a robust architecture for parallel AL. Its design centers on five specialized kernels that operate concurrently, communicating via the Message Passing Interface (MPI) standard for high efficiency on both shared- and distributed-memory systems [6]:

- Prediction Kernel: Hosts machine learning models that provide fast predictions of energies and forces during simulations.

- Generator Kernel: Runs multiple exploration processes (e.g., molecular dynamics steps) in parallel to propose new molecular configurations.

- Oracle Kernel: Manages parallelized quantum chemistry calculations to provide ground-truth labels for selected data points.

- Training Kernel: Handles the retraining of machine learning models as new data is incorporated.

- Controller Kernel: Orchestrates communication and data flow between all other kernels.

This modular design allows each component to be customized and scaled independently. For instance, multiple generator processes can run simultaneously to accelerate the exploration of chemical space, while multiple oracle processes can label data points in parallel, preventing the labeling step from becoming a bottleneck [6].

Workflow of an Integrated Parallel AL System

The following diagram illustrates the coordinated interaction between the major components in a parallel active learning system for molecular simulations, such as the one implemented in aims-PAX [19]:

Diagram: Parallel Active Learning Workflow for Molecular Simulations. The cycle of MD sampling, uncertainty-based selection, and parallel DFT labeling continues until model convergence.

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

The adoption of parallel and distributed AL frameworks has yielded dramatic improvements in computational efficiency across diverse chemical applications. Performance gains are typically measured in terms of the reduction in required quantum mechanical calculations, the speedup of AL cycle time, and the overall resource utilization.

Table: Performance Benchmarks of Parallel Active Learning Systems

| Application Domain | Computational Framework | Performance Gain | Key Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crystal Structure Search [22] | Neural Network Force Fields | Up to 100x reduction | Fewer DFT calculations required |

| Peptide & Perovskite MLFFs [19] | aims-PAX | 20x speedup; 100x reduction | AL cycle time; DFT calculations |

| Molecular Conformation Dataset [20] | SDDF Volunteer Computing | ~10 min/task | DFT calculation time per molecular conformation |

| IR Spectra Prediction [21] | PALIRS | 3 orders of magnitude faster than AIMD | MD simulation speed for spectra calculation |

Protocol for Benchmarking Parallel AL Efficiency

To objectively evaluate the performance of a parallel AL system, the following methodological protocol can be employed, drawing from the cited studies:

- System Setup: Select a target chemical system (e.g., a flexible peptide, a crystal composition like Si₁₆, or a set of organic molecules).

- Baseline Establishment: Perform a conventional, sequential AL process or a random sampling approach, measuring the total number of DFT calculations and the wall-clock time required to achieve a target accuracy (e.g., a mean absolute error in energy predictions below 1 meV/atom).

- Parallel AL Execution: Run the parallel AL workflow (e.g., using PAL or aims-PAX) on the same system. The key is to ensure all components—sampling, labeling, and training—are executed concurrently.

- In aims-PAX, this involves launching multiple independent molecular dynamics trajectories in parallel, each using the current ML potential to explore configuration space [19].

- Structures flagged as uncertain from any trajectory are collected in a central queue.

- A pool of worker processes consumes this queue, performing DFT calculations in parallel to label the structures.

- The training process is triggered asynchronously once a sufficient batch of new data is available.

- Metrics Collection:

- Computational Cost: Record the total number of DFT single-point calculations required for the model to converge.

- Wall-clock Speedup: Measure the total time from start to convergence, comparing it to the baseline.

- Resource Utilization: Monitor the usage of CPU/GPU resources across the cluster to evaluate the efficiency of the parallelization.

- Validation: The final model's accuracy is validated on a held-out test set of DFT calculations or by comparing its predictions of physical properties (e.g., IR spectra [21] or relative energies of crystal phases [22]) against reference data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Parallel AL

Implementing a successful parallel AL campaign requires a suite of software "reagents" and computational resources. The table below details the essential components.

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Parallel Active Learning

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Uncertainty Quantifier | Identifies regions of chemical space where the model is least confident, guiding data acquisition. | Ensemble of MACE models [21] [19]; Neural Network Force Field ensembles [22] |

| Parallel Sampler | Explores the chemical space (e.g., molecular geometries, compositions) concurrently. | Multi-trajectory Molecular Dynamics [19]; Random structure generation with PyXtal [22] |

| Distributed Oracle | Provides high-fidelity labels (e.g., energies, forces) for selected data points using quantum mechanics. | Parallel DFT in FHI-aims [19] or VASP; Volunteer computing for DFT [20] |

| Message Passing Interface | Enables high-speed communication and data exchange between processes in a distributed system. | MPI for Python (mpi4py) [6] |

| Machine Learning Potential | Fast, approximate model of the quantum mechanical potential energy surface. | MACE [19], SchNet [6], NequIP [6] |

| Workflow Manager | Orchestrates the execution and data flow between all other components. | Custom controller kernel [6]; Parsl [19] |

High-performance computing is not merely an accelerator but a fundamental enabler of modern active learning in chemical research. The parallel and distributed frameworks detailed herein—such as PAL, aims-PAX, and SDDF—deconstruct the sequential AL bottleneck by allowing for the simultaneous execution of sampling, labeling, and model training. The quantitative results are unambiguous: reductions of one to two orders of magnitude in the number of costly quantum calculations and speedups of over 20x in workflow completion time. As these frameworks continue to mature and integrate with emerging foundational models, they will further empower researchers and drug development professionals to navigate the breathtaking complexity of chemical space with unprecedented efficiency, ultimately accelerating the discovery of new materials and therapeutic agents.

Active Learning in Action: From Drug Discovery to Materials Informatics

The pursuit of novel therapeutic compounds is undergoing a paradigm shift, moving beyond traditional trial-and-error methods towards a more predictive, physics-informed science. At the heart of this transformation is the integration of generative artificial intelligence (AI) with physics-based computational oracles. This synergy aims to navigate the vast chemical space—estimated at 10^33 to 10^60 drug-like molecules—to design efficacious and synthesizable compounds [23]. While generative models can propose novel molecular structures, their true value is unlocked by guiding this generation with oracles that can predict a molecule's real-world behavior, such as its binding affinity to a biological target.

A critical enabler of this integration is active learning (AL), an iterative feedback process that strategically selects the most informative data points for computational or experimental evaluation. By embedding generative AI within an AL framework, researchers can create a self-improving cycle that simultaneously explores novel chemical regions while focusing resources on molecules with higher predicted affinity and better drug-like properties [12] [15]. This review explores the technical foundations, methodologies, and experimental protocols that define the state-of-the-art in physics-guided generative AI for drug design, framing its progress within the broader thesis of how active learning is revolutionizing optimization in chemical research.

The Generative AI and Active Learning Framework

Core Components of the Workflow

A typical integrated framework for de novo drug design consists of several key components that work in concert through an active learning loop.

- Generative Model: The engine that proposes new molecular structures. Common architectures include Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), and Diffusion Models [12] [23]. VAEs are often favored for their continuous latent space, which enables smooth interpolation and controlled generation [12].

- Molecular Representation: Molecules are typically represented as Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) strings or molecular graphs, which are then tokenized and converted into numerical vectors for the AI model [12].

- Physics-Based Oracles: These are computational methods used to evaluate the generated molecules. They span a range of accuracy and computational cost, creating a multi-fidelity environment [11].

- Active Learning Controller: This component manages the iterative cycle. It uses acquisition strategies to select which generated molecules to evaluate with the oracles, and then uses the results to refine the generative model [15].

The Active Learning Cycle in Practice

The active learning cycle operates through a structured, iterative process designed to maximize information gain while minimizing the use of expensive computational resources. The following Graphviz diagram visualizes a representative workflow integrating these components, inspired by recent literature [12] [11] [15]:

Active Learning-Driven Generative Workflow Figure 1: A unified active learning framework for generative drug design, showcasing the iterative feedback between molecular generation and multi-fidelity physics-based oracles.

The process can be broken down into the following key stages, which correspond to the workflow in Figure 1:

- Initialization: A generative model (e.g., a VAE) is pre-trained on a broad dataset of known drug-like molecules to learn fundamental chemical rules and valid structures [12].

- Generation: The trained model samples its latent space to generate a large and diverse pool of novel molecular candidates.

- Evaluation and Acquisition: The Active Learning controller selects a batch of molecules from the pool using a defined acquisition strategy. Common strategies include:

- Uncertainty Sampling: Selecting molecules for which the surrogate model's prediction is most uncertain.

- Expected Improvement: Choosing molecules predicted to significantly outperform current best candidates.

- Diversity Sampling: Ensuring the selected batch represents broad chemical space coverage [15]. These molecules are first evaluated with a faster, low-fidelity oracle like molecular docking.

- Multi-Fidelity Refinement: A promising subset of molecules that pass the initial screening is promoted to a more accurate, high-fidelity oracle, such as Absolute Binding Free Energy (ABFE) calculations [11].

- Feedback and Model Update: The results from the oracles are used to create a refined, target-specific dataset. This dataset is then used to fine-tune the generative model, biasing future generations toward regions of chemical space with more desirable properties [12]. This cycle repeats for a set number of iterations or until a performance criterion is met.

Physics-Based Oracles: A Multi-Fidelity Approach

The accuracy of a generative AI campaign is directly tied to the reliability of the oracles used to guide it. A multi-fidelity approach balances computational cost with predictive accuracy, creating a tiered evaluation system.

Table 1: Characteristics of Physics-Based Oracles Used in Active Learning

| Oracle Type | Typical Methods | Computational Cost | Predictive Accuracy | Primary Role in AL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemoinformatic | QED, SA Score, LogP | Low | Low | Initial filtering for drug-likeness and synthetic accessibility [12] |

| Low-Fidelity | Molecular Docking (AutoDock) | Medium | Low-Medium | High-throughput initial screening and prioritization [11] |

| High-Fidelity | Absolute Binding Free Energy (ABFE) | Very High | High | Final validation of a small subset of top candidates [11] |

| Advanced Sampling | Monte Carlo (PELE), Molecular Dynamics | High | High | Refining docking poses and assessing binding stability [12] |

The Oracle Hierarchy in Practice

- Low-Fidelity Oracles (e.g., Molecular Docking): Docking software like AutoDock quickly scores how well a small molecule fits into a protein's binding pocket [11]. While fast, it is a relatively poor predictor of actual biological activity, as it often oversimplifies solvent effects and protein flexibility [11].

- High-Fidelity Oracles (e.g., Binding Free Energy Calculations): Methods like Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations calculate the Absolute Binding Free Energy (ABFE), providing a more reliable estimate of binding affinity [11]. They are considered the gold standard for in silico affinity prediction but are prohibitively expensive for screening large libraries, with a single calculation potentially taking "hours to days on a powerful computer" [11].

- The Multi-Fidelity Solution: To overcome this cost-accuracy trade-off, frameworks like Multi-Fidelity Latent space Active Learning (MF-LAL) train surrogate models that integrate data from both low and high-fidelity oracles [11]. This allows the generative model to learn an inexpensive but accurate proxy for the high-fidelity oracle, dramatically improving the efficiency of the discovery process. One study reported that this approach can achieve a ~50% improvement in mean binding free energy of generated compounds compared to single-fidelity methods [11].

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Validating an integrated generative AI and active learning pipeline requires rigorous in silico benchmarks and, ultimately, synthesis and biological testing.

Case Study: VAE-AL Workflow for CDK2 and KRAS

A published workflow demonstrates a successful application using a VAE with two nested AL cycles [12]. The detailed methodology is as follows:

Data Preparation and Initial Training:

- Representation: Molecules were represented as SMILES strings, tokenized, and converted into one-hot encoding vectors.

- Training: The VAE was first trained on a general set of drug-like molecules, then fine-tuned on a target-specific set (e.g., known CDK2 inhibitors).

Nested Active Learning Cycles:

- Inner AL Cycle (Chemical Optimization):

- The trained VAE generates new molecules.

- Generated molecules are evaluated with chemoinformatic oracles for drug-likeness (QED), synthetic accessibility (SA), and novelty.

- Molecules passing these filters are added to a temporal-specific set, which is used to fine-tune the VAE.

- Outer AL Cycle (Affinity Optimization):

- After several inner cycles, molecules accumulated in the temporal set are evaluated with a physics-based oracle (molecular docking).

- Molecules with favorable docking scores are transferred to a permanent-specific set, which is used for the next round of VAE fine-tuning.

- These nested cycles run iteratively, progressively steering the generation toward chemically valid, synthesizable, and high-affinity molecules [12].

- Inner AL Cycle (Chemical Optimization):

Candidate Selection and Experimental Validation:

- Top-ranked candidates from the permanent set undergo more rigorous physics-based simulations, such as Monte Carlo simulations with PEL to refine binding poses and assess stability [12].

- The most promising candidates are selected for chemical synthesis and in vitro activity assays.

- Result: For the CDK2 program, this workflow led to the synthesis of 9 molecules, 8 of which showed in vitro activity, including one with nanomolar potency [12].

Protocol: Multi-Fidelity Latent Space Active Learning (MF-LAL)

The MF-LAL framework provides another validated protocol for integrating oracles of different fidelities [11]:

- Surrogate Model Training: A hierarchical model is trained to predict high-fidelity properties (e.g., ABFE) from low-fidelity data (e.g., docking scores) and molecular structures.

- Query Generation and Selection: The generative model produces new molecules. The AL algorithm selects queries based on the surrogate model's predictions and its associated uncertainty.

- Oracle Evaluation and Update: Selected molecules are evaluated with the appropriate oracle. Crucially, molecules promoted to the high-fidelity oracle are chosen based on their promising performance at the low-fidelity level and high uncertainty in the surrogate model's high-fidelity prediction.

- Iterative Refinement: The new high-fidelity data is used to update the surrogate and generative models, closing the active learning loop and improving the system's predictive power with each cycle [11].

Table 2: Experimental Results from Case Studies Applying Integrated AI and Physics-Based Methods

| Target Protein | Generative Model | Key Oracles | Experimental Outcome | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDK2 | VAE with Nested AL | Docking, PELE, ABFE | 8 out of 9 synthesized molecules showed in vitro activity; 1 with nanomolar potency. | [12] |

| KRAS | VAE with Nested AL | Docking, PELE, ABFE | 4 molecules identified with potential activity via in silico methods validated by CDK2 assays. | [12] |

| Two Disease-Relevant Proteins | MF-LAL (Multi-Fidelity) | Docking, Binding Free Energy | ~50% improvement in mean binding free energy of generated compounds vs. baselines. | [11] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Implementing the described workflows requires a suite of computational tools and resources. The table below details key components of the technology stack.

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for AI-Driven Drug Design

| Tool Category | Example Software/Libraries | Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Generative Modeling | PyTorch, TensorFlow, RDKit | Provides the foundation for building and training VAEs, GANs, and other generative architectures. |

| Cheminformatics | RDKit, Open Babel | Handles molecular representation, fingerprinting, and calculation of simple properties (QED, SA). |

| Docking (Low-Fidelity Oracle) | AutoDock Vina, GOLD, Glide | Performs rapid molecular docking to score protein-ligand interactions and predict binding poses. |

| Molecular Simulation (High-Fidelity Oracle) | GROMACS, AMBER, OpenMM, PELE | Runs Molecular Dynamics or Monte Carlo simulations for calculating binding free energies and assessing complex stability. |

| Multi-Fidelity & AL Frameworks | Custom implementations (e.g., MF-LAL) | Integrates data from multiple oracles and manages the active learning cycle and surrogate modeling. |

The integration of generative AI with physics-based oracles, orchestrated through active learning, represents a mature and powerful paradigm for de novo drug design. This approach directly addresses the core challenges of traditional methods by enabling the efficient exploration of vast chemical spaces while ensuring that generated molecules are grounded in physical reality. The technical frameworks and case studies reviewed here demonstrate that this synergy is no longer theoretical but is already yielding experimentally validated results, including novel scaffolds and compounds with nanomolar potency against challenging biological targets.

The future of this field lies in the continued refinement of its components: more robust generative models, increasingly accurate and efficient physics-based simulators, and more intelligent active learning strategies that can seamlessly incorporate human expert feedback. As these technologies mature, the vision of a fully automated, closed-loop drug discovery system—where AI designs molecules, robots synthesize them, and assays test them, with data flowing continuously back to improve the AI—moves closer to reality, promising to accelerate the delivery of new therapeutics to patients.

Optimizing Machine-Learned Potentials for Molecular Dynamics and IR Spectra

In the realm of computational chemistry, achieving high-fidelity simulations of molecular systems while managing prohibitive computational costs presents a fundamental challenge. This is particularly true for predicting infrared (IR) spectra, where traditional methods like density functional theory-based ab-initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) provide high accuracy but are severely limited by computational expense, restricting tractable system size and complexity [21]. The emergence of machine-learned interatomic potentials (MLIPs) has created a paradigm shift, offering the potential to accelerate simulations by several orders of magnitude. However, the development of accurate and reliable MLIPs hinges on the creation of high-quality training datasets that comprehensively capture the relevant configurational space of molecular systems. Active learning (AL) has arisen as a powerful solution to this data generation challenge, establishing itself as a core optimization methodology within modern computational chemistry research [21] [12] [16].

Active learning frameworks systematically address the inefficiencies of conventional exhaustive sampling methods by implementing intelligent, iterative data selection. These protocols enable a machine learning model to strategically query its own uncertainty, selecting the most informative data points for labeling and subsequent model retraining [16]. This approach minimizes redundant calculations and focuses computational resources on regions of the chemical space where the model's performance is poorest, thereby maximizing the informational value of each data point added to the training set. The resulting optimized MLIPs can then be deployed in efficient molecular dynamics (MD) simulations for accurate property prediction, including IR spectra. This technical guide explores the core architectures, quantitative performance, and detailed experimental protocols for optimizing machine-learned potentials, with a specific focus on their application within molecular dynamics and IR spectra prediction, all framed within the transformative context of active learning.

Core Active Learning Frameworks and Architectures

The implementation of active learning can vary significantly based on the specific scientific objective, be it exploring vast chemical spaces or exploiting known regions for optimization. This section details the primary AL frameworks and their underlying architectures.

The PALIRS Framework for IR Spectroscopy

The Python-based Active Learning Code for Infrared Spectroscopy (PALIRS) exemplifies a specialized AL framework designed for efficiently constructing training datasets to predict IR spectra [21] [24]. Its primary goal is to train an MLIP that can accurately describe energies and interatomic forces, which is later paired with a separate model for dipole moment predictions required for IR intensity calculations. PALIRS employs an uncertainty-based active learning strategy where an ensemble of models (e.g., three MACE models) approximates the prediction uncertainty for interatomic forces [21].

- Initialization: The process begins by training an initial MLIP on a small set of molecular geometries sampled along normal vibrational modes, obtained from DFT calculations.

- Iterative Refinement: The initial model is used to run machine learning-assisted molecular dynamics (MLMD) simulations at multiple temperatures (e.g., 300 K, 500 K, and 700 K) to ensure broad exploration of the configurational space.

- Acquisition Strategy: During these MLMD runs, molecular configurations exhibiting the highest uncertainty in force predictions are selected and their accurate energies and forces are computed using the reference DFT method.

- Model Update: These newly acquired, informative data points are added to the training set, and the MLIP is retrained. This cycle repeats—simulation, uncertainty-based acquisition, DFT calculation, retraining—until the model achieves a predefined level of accuracy across the relevant chemical space [21].

The following diagram illustrates this iterative, self-improving workflow:

Explorative vs. Exploitative Active Learning

While PALIRS uses uncertainty to explore the configurational space, other AL strategies are designed for exploitation, particularly in molecular optimization campaigns. Explorative active learning prioritizes data points where the model is most uncertain to improve overall model robustness and generalizability [16]. In contrast, exploitative active learning biases the selection towards molecules predicted to have the most favorable properties (e.g., highest potency, best docking score) to rapidly identify top candidates [12] [16].

A sophisticated variant known as ActiveDelta has been developed to enhance exploitative learning. Instead of predicting absolute molecular properties, ActiveDelta models are trained on paired molecular representations to directly predict property differences or improvements [16]. In this framework, the next compound selected for evaluation is the one predicted to offer the greatest improvement over the current best compound in the training set. This approach benefits from combinatorial data expansion through pairing and has been shown to outperform standard exploitative methods in identifying potent and chemically diverse inhibitors [16].

Quantitative Performance and Data Analysis

The efficacy of active learning in optimizing MLIPs is demonstrated through concrete, quantitative improvements in model accuracy and computational efficiency. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from relevant studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of Active Learning-Optimized Workflows

| Framework / Metric | Initial Training Set Size | Final Training Set Size | Key Performance Improvement | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PALIRS [21] | 2,085 structures | 16,067 structures | Accurately reproduced AIMD IR spectra at a fraction of the cost; good agreement with experimental peak positions and amplitudes. | High-throughput prediction enabled; MLMD simulations are orders of magnitude faster than AIMD. |

| ActiveDelta (Chemprop) [16] | 2 random datapoints per dataset | 100 selected datapoints | Identified a greater number of top 10% most potent inhibitors across 99 benchmark datasets compared to standard methods. | Achieved superior performance with fewer data points, reducing experimental burden in early-stage discovery. |

| VAE with AL Cycles [12] | Target-specific training set | Iteratively expanded via AL | For CDK2: Generated novel scaffolds; 9 molecules synthesized, 8 showed in vitro activity, 1 with nanomolar potency. | Efficiently explored novel chemical spaces tailored for specific targets, yielding high hit rates. |