Validating Metal Oxidation States: A Multi-Technique Framework for Materials and Drug Development

Accurate determination of metal oxidation states is critical for understanding material properties, catalytic activity, and the biological interactions of metal-containing compounds in drug development.

Validating Metal Oxidation States: A Multi-Technique Framework for Materials and Drug Development

Abstract

Accurate determination of metal oxidation states is critical for understanding material properties, catalytic activity, and the biological interactions of metal-containing compounds in drug development. This article provides a comprehensive framework for validating oxidation states using a suite of complementary techniques. It covers the fundamental principles of oxidation state assignment, details both established and emerging computational and experimental methodologies, and offers strategies for troubleshooting discrepancies. By synthesizing insights from computational chemistry, machine learning, crystallography, and spectroscopy (including XPS), this guide empowers researchers to confidently characterize complex and dynamic systems, from battery materials to metal-organic frameworks and metallodrugs.

The Critical Role of Oxidation States in Material and Biological Function

The oxidation state (OS) is a fundamental concept in chemistry that represents the hypothetical charge of an atom if all its bonds were purely ionic. This formalism describes the degree of oxidation—or electron loss—of an atom within a chemical compound. Despite its conceptual nature, OS serves as an indispensable tool for understanding redox reactions, predicting chemical behavior, and systematizing inorganic nomenclature [1]. The concept originated with Antoine Lavoisier, who initially defined oxidation as reactions involving oxygen, though the definition later expanded to include any reaction involving electron loss regardless of oxygen participation [2].

A significant challenge arises from the fact that oxidation states represent a chemical formalism rather than a direct physical observable. As explicitly stated in chemical literature, "It is a serious mistake to think that our oxidation state system provides a quantitative description of actual electron densities" [3]. This distinction between chemical intuition and physical reality creates a crucial bridge that must be spanned through complementary validation techniques, particularly for complex systems such as transition metals in biological cofactors or battery materials where accurate OS assignment is critical for understanding function [4] [5].

Theoretical Foundations and Assignment Rules

Conventional Rule-Based Assignment

The traditional approach to determining oxidation states relies on a set of hierarchically applied rules derived from periodic trends and electronegativity considerations [6] [3] [1]:

- The oxidation state of an uncombined element is always zero [6] [1].

- For monatomic ions, the oxidation state equals the ionic charge [1].

- Alkali metals consistently exhibit a +1 oxidation state, while alkaline earth metals display a +2 state [6] [3].

- Fluorine always maintains a -1 oxidation state, while other halogens typically do as well, except when bonded to oxygen or lighter halogens [3] [1].

- Hydrogen is typically assigned +1, except in metal hydrides where it takes a -1 state [6] [3].

- Oxygen generally assumes a -2 state, except in peroxides (-1) or when bonded to fluorine [6] [3].

- The sum of oxidation states must equal the overall charge of the molecule or ion [6] [3] [1].

For transition metals, which frequently exhibit multiple oxidation states, these rules require careful application. Elements like vanadium can display multiple states (+2, +3, +4, +5), with each step involving the loss of an additional electron [6]. The d-block electronic configuration influences these variable states, as partially filled d-orbitals can accommodate electron loss from both s and d orbitals [7].

Quantum Mechanical Challenges

From a quantum mechanical perspective, oxidation states present a significant challenge because electron density is global rather than atomically partitioned [8]. As noted by Yin and Xiao, "The oxidation state (OS) is an essential chemical concept that embodies chemical intuition but cannot be computed with well-defined physical laws" [8]. This fundamental limitation means that quantum mechanical calculations require additional approximations and corrections to align with chemical intuition.

Standard density functional theory (DFT) calculations suffer from self-interaction errors that cause unphysical electron delocalization, particularly problematic for systems with strongly localized d or f electrons [5]. Advanced approaches like DFT+U+V (incorporating both on-site U and inter-site V Hubbard corrections) have shown improved capability to describe redox processes and provide more accurate oxidation state assignments in materials such as transition-metal oxides and battery cathode materials [5].

Experimental Determination Techniques

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

XPS serves as a powerful technique for oxidation state analysis on solid surfaces by measuring the binding energies of core electrons, which shift depending on the atomic charge state [9].

Table 1: XPS Analysis of Molybdenum Sulfide Powder

| Element | Binding State | Oxidation State | Atomic % | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mo | MoS₂ | +4 | 13.9 | Major phase |

| Mo | MoO₃ | +6 | 1.2 | ~7.9% of total Mo |

| S | S²⁻ (in MoS₂) | -2 | 26.3 | Sulfidic form |

| O | - | - | 3.7 | Surface contamination |

| C | - | - | 54.9 | Surface contamination |

In the representative study of molybdenum sulfide lubricant powder, XPS quantification revealed that approximately 7.9% of molybdenum existed as Mo(VI) in MoO₃ alongside the primary Mo(IV)S₂ phase, demonstrating the method's capability to identify and quantify mixed oxidation states in complex materials [9].

Spatially Resolved Anomalous Dispersion (SpReAD) Refinement

For metalloproteins, SpReAD refinement provides a sophisticated approach to determine oxidation states of individual metal centers within crystal structures by exploiting the energy dependence of anomalous scattering [4]. This method reconstructs element-specific absorption spectra for individual metal sites by collecting diffraction data at multiple energies across an absorption edge, typically in 2eV steps [4].

The experimental workflow for SpReAD analysis requires careful attention to radiation damage, as high X-ray doses can cause photoreduction and alter oxidation states during data collection [4]. In a study of sulerythrin, a ruberythrin-like protein containing a binuclear metal center, SpReAD analysis revealed different oxidation states between the two iron ions in crystals treated with H₂O₂, demonstrating the method's unique capability to discriminate oxidation states at individual metal sites within multinuclear centers [4].

X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS)

While not explicitly detailed in the search results, X-ray Absorption Near Edge Structure (XANES) and Extended X-ray Absorption Fine Structure (EXAFS) are mentioned as complementary methods for oxidation state analysis, particularly useful for determining the average oxidation state of specific elements in complex systems [4].

Computational Approaches and Data-Driven Methods

The TOSS Framework

The Tsinghua Oxidation States in Solids (TOSS) framework represents a novel data-driven paradigm for determining oxidation states in crystal structures [8]. This approach employs Bayesian maximum a posteriori probability estimation to abstract distance thresholds and coordination environments from large datasets of crystal structures, effectively "learning" chemical intuition from structural data [8].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of OS Determination Methods

| Method | Principle | Application Scope | Accuracy | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOSS | Data-driven Bayesian MAP | Inorganic crystals | 96.09% | Limited to structures in training domain |

| GCN Model | Graph convolutional networks | Inorganic crystals | 97.24% | Black-box prediction |

| BVM | Bond valence parameters | Crystals with parameters | Variable | Parameter availability |

| SpReAD | Anomalous dispersion | Metalloprotein crystals | Site-specific | Radiation damage concerns |

| XPS | Core electron binding | Solid surfaces | Surface-sensitive | Limited to surfaces |

When applied to over 250,000 high-confidence crystal structures, TOSS achieved 96.09% accuracy against human-curated reference data, while a graph convolutional network (GCN) model trained on TOSS results reached 97.24% accuracy [8]. This demonstrates the powerful synergy between data-driven methods and machine learning in oxidation state assignment.

First-Principles Approaches

Sit et al. developed a novel theoretical approach for unambiguous oxidation state determination from quantum-mechanical calculations that separates metal-ligand orbital mixing from actual d-orbital occupation [10]. This method, applied to transition-metal complexes and materials using DFT+U, provides a more rigorous foundation for oxidation state assignment from first principles [10].

Recent advances combine these approaches with machine learning potentials, treating atoms with different oxidation states as distinct species during training [5]. This "redox-aware" machine learning strategy has shown promise for modeling complex electrochemical processes in battery materials where accurate description of oxidation state evolution is crucial [5].

Experimental Protocols

SpReAD Refinement Protocol for Metalloproteins

The SpReAD methodology requires meticulous experimental design and execution [4]:

Sample Preparation: Metalloprotein crystals must be grown and cryocooled under controlled conditions matching the physiological or relevant experimental environment. For the sulerythrin study, crystals were grown under anoxic conditions using vapor diffusion in sitting drops [4].

Data Collection: X-ray diffraction data must be collected at multiple energies (typically 10-20 points) across the absorption edge of the element of interest, with careful dose control to minimize radiation damage. The reported sulerythrin experiment used 2eV steps across the iron K-edge [4].

Structure Refinement: Conventional refinement is performed against data collected at each energy to obtain Δf″ values for individual metal atoms.

Spectra Reconstruction: The refined Δf″ values are used to reconstruct absorption spectra for each metal site.

Oxidation State Assignment: The relative positions of inflection points in these site-specific spectra indicate oxidation states, calibrated against reference compounds with known oxidation states.

Critical considerations include rigorous radiation dose management and the use of controlled environments to preserve biological relevance during data collection [4].

XPS Analysis Protocol for Solid Materials

XPS analysis for oxidation state determination follows a standardized workflow [9]:

Sample Preparation: Powder or solid samples are typically mounted on adhesive tapes or holders without chemical treatment that might alter oxidation states.

Data Acquisition:

- First, an overview spectrum (0-1100 eV binding energy) identifies all elements present.

- High-resolution spectra are then collected for elements of interest using appropriate X-ray sources and pass energies.

Spectral Analysis:

- Peaks are fitted with appropriate background subtraction and line shapes.

- Chemical shifts are referenced to adventitious carbon (C 1s at 284.8 eV).

- Oxidation states are assigned based on established binding energy databases.

Quantification: The relative areas of peaks corresponding to different oxidation states are used to calculate their proportions, as demonstrated in the molybdenum sulfide study [9].

Integrated Workflow for Oxidation State Validation

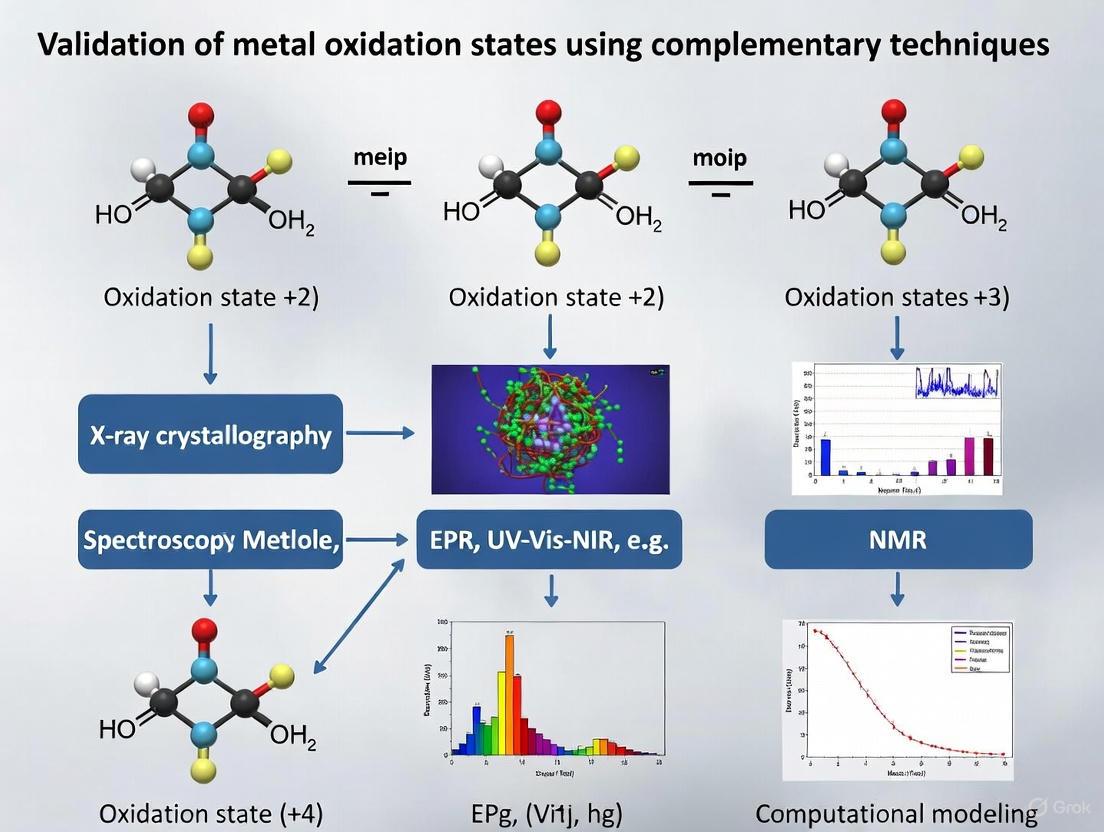

The complex nature of oxidation states in real systems often requires a complementary approach combining multiple techniques. The following workflow diagram illustrates the relationship between different determination methods:

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Oxidation State Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Strep-Tactin resin | Affinity chromatography | Protein purification for metalloprotein crystallography [4] |

| Anoxic chamber | Controlled atmosphere | Sample preparation for oxygen-sensitive compounds [4] |

| Crystallization screens | Crystal growth | Metalloprotein crystallization for SpReAD [4] |

| Reference compounds | Calibration standards | XPS and XANES quantification [4] [9] |

| X-ray sources | Electron excitation | XPS analysis of surface oxidation states [9] |

| Synchrotron beamtime | Tunable X-ray source | SpReAD and XAS experiments [4] |

The determination of oxidation states represents an interface between chemical intuition and physical measurement, requiring complementary approaches for robust validation. While conventional rules provide initial assignments, advanced techniques like SpReAD refinement, XPS, and data-driven methods like TOSS offer increasingly sophisticated approaches for ambiguous cases. The integration of first-principles calculations with machine learning, as demonstrated by redox-aware potentials, points toward a future where oxidation state evolution can be tracked dynamically in complex operating environments like battery electrodes or catalytic cycles. For researchers, the selection of appropriate methods depends on the specific system—with SpReAD offering site-specific resolution in proteins, XPS providing surface-sensitive analysis of materials, and computational approaches enabling high-throughput screening of hypothetical compounds. As these techniques continue to mature, they strengthen the critical bridge between the formal concept of oxidation state and its manifestation in real chemical systems.

Accurately determining the oxidation states of metals is a fundamental challenge in materials science and chemistry. The oxidation state of an element dictates its chemical behavior, influencing everything from the efficiency of an electrocatalyst to the stability of a battery electrode and the mechanism of a pharmaceutical drug. Relying on a single analytical technique, however, can lead to an incomplete or misleading picture. This guide compares the performance of various validation techniques, underscoring through experimental data how a multi-faceted approach is critical for research reliability and technological advancement.

The Critical Role of Oxidation State Validation

The oxidation state of a metal atom refers to its charge after the ionic approximation of its heteronuclear bonds [5]. While a simple concept, its accurate determination from first principles is challenging. Standard computational methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT) are often plagued by self-interaction errors, which cause unphysical delocalization of electrons and misrepresent the true oxidation states in materials with strongly localized electrons, such as transition-metal oxides [5]. This is not merely an academic concern; an incorrect assignment can lead to flawed interpretations of a material's properties or a drug's biochemical pathway.

Validation through complementary techniques provides a corrective lens. For instance, DFT+U+V, an advanced computational method, can provide a more reliable description of redox reactions, but its predictions still require experimental verification [5]. The following sections demonstrate how this principle of cross-validation is applied across different fields to achieve robust, reliable results.

Comparative Analysis of Validation Techniques

The table below summarizes the performance and application of various techniques used for validating metal oxidation states and their functional implications.

Table 1: Comparison of Oxidation State Validation and Application Techniques

| Field/Technique | Key Performance Metrics | Advantages | Limitations / Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Materials (DFT+U+V) [5] | Accurately tracks adiabatic evolution of OS; enables development of redox-aware machine-learning potentials. | Mitigates self-interaction errors; provides atomic-level insight; good for predictive modeling. | Computationally expensive; requires careful parameterization; results need experimental validation. |

| Electrocatalysis (In Situ/Operando Characterization) [11] | Identifies true active phases; monitors dynamic atomic rearrangement (e.g., Ni to NiOOH); links structural change to activity. | Probes catalysts under working conditions; captures transient intermediates and reversible changes. | Requires sophisticated, often synchrotron-based equipment; data interpretation can be complex. |

| Battery Diagnostics (Physics-Informed Neural Networks - PINNs) [12] | Predicts internal health parameters ~1000x faster than traditional physics models; quantifies physical degradation mechanisms. | Enables rapid, non-destructive diagnostics; integrates physical laws for scientific rigor. | Transition from simulation to real-world data validation is ongoing; model refinement for diverse systems is needed. |

| Drug Analysis (Electrochemical Sensors) [13] | High sensitivity (µM to fM); rapid response (seconds to minutes); can probe redox mechanisms of drugs. | Simple, cost-effective; compatible with complex biological matrices; can be deployed as wearable devices. | Susceptible to matrix interference; limited shelf life; signal drift requires frequent calibration. |

| Chemical Analysis (Formaldehyde Clock System) [14] | Identifies Fe(VI), Fe(III), Fe(II) based on their differential effect on a reaction's induction period. | Simple operation, fast analysis, and low cost; useful for qualitative distinction. | Limited quantitative application; concentration range limited (2.0×10⁻⁴ − 1.2×10⁻³ mol L⁻¹). |

| Structural Validation (NMR Crystallography) [15] | Validates crystal structures by comparing experimental vs. calculated NMR chemical shifts (using Machine Learning like ShiftML). | Provides atomic-level resolution for powdered solids; high sensitivity to local atomic environment. | Requires expertise in solid-state NMR; machine learning models depend on the quality of training data. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol for Electrocatalyst Reconstruction Validation

Understanding the dynamic surface changes of electrocatalysts requires a rigorous workflow combining in situ characterization and electrochemical analysis.

Core Workflow:

Key Experimental Steps:

- Pre-catalyst Synthesis and Baseline Characterization: Synthesize the pristine catalyst (e.g., Ni(OH)₂, Co₃O₄, or metal sulfides). Characterize its initial state using ex situ techniques like Powder X-Ray Diffraction (PXRD) for crystal structure, Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) for morphology, and X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) for initial surface composition and oxidation state [11].

- In Situ/Operando Characterization: Subject the catalyst to relevant electrochemical conditions (e.g., Oxygen Evolution Reaction (OER) at 1.0-1.5 V vs. RHE) while simultaneously collecting data. Key techniques include:

- X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS): Probes local electronic structure and coordination environment of metal atoms, directly tracking oxidation state changes (e.g., Ni²⁺ to Ni³⁺/⁴⁺) [11].

- In Situ Raman Spectroscopy: Identifies the formation of new chemical species and phases on the catalyst surface in real-time (e.g., detection of NiOOH) [11].

- Post-mortem Analysis: After testing, the catalyst is removed and re-analyzed with techniques like TEM and XPS to identify permanent, irreversible changes to the structure and composition.

- Data Correlation: The data from all stages is correlated with electrochemical performance metrics (activity, stability) to unequivocally link the reconstructed surface phase (the "true catalyst") to its function [11].

Protocol for Battery Electrode Activation and Diagnostics

Validating the effectiveness of electrode treatments and diagnosing health states are key for battery development.

Core Workflow:

Key Experimental Steps:

- Electrode Activation and Physical Validation: As demonstrated in vanadium redox flow batteries, graphite felt electrodes can be thermally activated. A systematic study involves testing different temperatures (300-500°C) and durations (3-24 hours). The optimal condition (e.g., 400°C for 7 hours) is validated by measuring an increase in oxygen-containing functional groups on the surface (using XPS) which enhances electrode activity [16].

- Electrochemical Performance Testing: Assembled batteries are cycled through charge/discharge tests. Key metrics include energy efficiency, voltage efficiency, capacity retention, and internal resistance. The improved performance of activated electrodes is quantitatively measured (e.g., energy efficiency increased by 3.67-5.94%) [16].

- AI-Driven Diagnostic Validation: A Physics-Informed Neural Network (PINN) can be employed as a surrogate for complex physical battery models. The PINN is trained on voltage/current data and uses underlying physical laws to rapidly predict internal state-of-health parameters, such as lithium inventory and electrode kinetics, offering a non-destructive method for diagnosing degradation and validating the effectiveness of the electrode activation [12].

Protocol for Drug Redox Mechanism and Analysis

Probing the redox behavior of metal-containing drugs or pharmaceutical pollutants is essential for understanding their mechanism and environmental impact.

Core Workflow:

Key Experimental Steps:

- Electrochemical Detection: Techniques like cyclic voltammetry (CV) or differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) are used to study the drug's redox behavior. The drug is dissolved in a suitable electrolyte (often mimicking physiological conditions) and its oxidation/reduction peaks are measured. This provides information on the redox potential and the nature of electron transfer processes [13].

- Linking Redox Behavior to Adverse Effects: The redox characteristics of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) can be linked to their propensity to generate Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), which cause oxidative stress. Electrochemical data can help predict the nature and severity of side effects, such as gastrointestinal or cardiovascular complications, by revealing how easily the drug undergoes redox cycling [13].

- Validation with Complementary Techniques: The identity of drug molecules and their metabolites is confirmed using techniques like LC-MS (Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry). Furthermore, for solid drugs, NMR Crystallography—which combines solid-state NMR with computational methods like machine learning (ShiftML) and X-ray diffraction data—is used to definitively validate the crystal structure, including the atomic environment around metal centers if present [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Featured Experiments

| Item | Function / Application | Field |

|---|---|---|

| Graphite Felt Electrodes | High-surface-area electrode for redox reactions; requires activation (e.g., thermal) to improve performance. | Battery Science [16] |

| Transition Metal Oxide/Sulfide Precursors | (e.g., Ni(OH)₂, Co₃O₄, MoS₂). Starting materials for pre-catalysts that reconstruct under operational conditions. | Electrocatalysis [11] |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Disposable, miniaturized platforms for electrochemical detection; ideal for rapid, on-site drug analysis. | Pharmaceutical Analysis [17] |

| Formaldehyde Clock System Reagents | (HCHO, NaHSO₃, Na₂SO₃). A chemical system used to qualitatively distinguish between different oxidation states of metals like iron based on reaction kinetics. | Analytical Chemistry [14] |

| Magic Angle Spinning (MAS) NMR Probe | Essential hardware for solid-state NMR; ultra-fast MAS (>100 kHz) enables high-resolution ¹H-detected NMR for crystal structure validation. | NMR Crystallography [15] |

The consistent theme across electrocatalysis, battery science, and pharmaceutical research is that reliance on a single method is insufficient for definitive conclusions about metal oxidation states. Validation through a complementary suite of techniques—whether combining computation with operando spectroscopy, electrochemistry with AI, or voltammetry with crystallography—is what transforms a preliminary finding into a robust scientific result. This rigorous, multi-technique approach is foundational to developing more efficient catalysts, longer-lasting batteries, and safer pharmaceuticals.

Common Pitfalls and the Need for a Multi-Technique Approach

Accurately determining metal oxidation states is fundamental to research in catalysis, energy storage, and materials science. Relying on a single analytical technique, however, often leads to misinterpretation and incomplete characterization. This guide outlines common experimental pitfalls and demonstrates how a multi-technique approach provides robust validation, using comparative experimental data to illustrate key principles.

Common Pitfalls in Single-Technique Analysis

Using a single analytical method to determine metal oxidation states introduces significant risks. The following table summarizes frequent challenges and their consequences.

| Pitfall | Consequence | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Improper Calibration and Energy Offsets | Incorrect alignment between experimental data and reference spectra, leading to misidentification of oxidation states. [18] | In XAS and EELS, fluctuations in temperature or stray magnetic fields can cause energy shifts, requiring reference standards measured in the same session for reliable calibration. [18] |

| Overlooking Sample/Thickness Effects | Spectral fine structures can change with sample thickness, altering key intensity ratios and leading to false conclusions. [18] | In EELS analysis of Mn, the L2/L3 intensity ratio increases with sample thickness, rendering reference-free ratio methods unreliable. [18] |

| Inadequate Forcefield Selection in Modeling | Computational models may predict unrealistic or energetically unfavorable structures, contradicting experimental findings. [19] | MD/MC simulations using the ReaxFF forcefield for Pt nanoparticles predicted detached Pt6O8 clusters; however, these species were deemed implausible after comparison with higher-fidelity MACE-MP-0 and DFT calculations. [19] |

| Ignoring Measurement Error and Statistical Power | Underpowered studies or those ignoring error can produce false positive/negative results or overestimate effect sizes. [20] | A "too-small-for-purpose" sample size causes overfitting and a lack of statistical power, while disregarding measurement error can lead to the "noisy data fallacy." [20] |

The Multi-Technique Solution: An Integrated Workflow

A synergistic approach that combines computational, electrochemical, and spectroscopic methods mitigates the limitations of any single technique. The following workflow for characterizing oxidation states in metal nanoparticles integrates these complementary strategies.

Comparative Experimental Data from Multi-Technique Studies

Case Study 1: Platinum Nanoparticle Oxidation

A 2025 study combined computational and experimental techniques to investigate the oxidation of a realistic 353-atom Pt nanoparticle. The table below summarizes the purpose and findings of each technique, highlighting their complementary nature. [19]

| Technique | Purpose in the Study | Key Outcome / Finding |

|---|---|---|

| ReaxFF/MD-MC Simulations | To simulate the oxidation process and predict oxide structures at high oxygen partial pressure. | Predicted significant oxidation with oxygen penetrating the nanoparticle core and forming Pt6O8 clusters. |

| MACE-MP-0 & DFT | To provide higher-accuracy validation of the energetics and structures predicted by ReaxFF. | Revealed poor agreement in binding energies with ReaxFF, casting doubt on the plausibility of the predicted Pt6O8 species. |

| X-ray Diffraction (XRD) | To measure coordination numbers and bond distances for comparison with simulated structures. | Showed partial agreement with simulations in terms of coordination numbers and bond distances. |

| Extended X-ray Absorption Fine Structure (EXAFS) | To analyze local coordination environment and bond lengths. | Provided experimental data on coordination numbers and bond distances that partially aligned with simulations. |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | To provide structural information on particle size and morphology. | Used for 3D experimental reconstruction of the initial Pt nanoparticle structure used in simulations. |

Case Study 2: Manganese Oxidation State Decomposition

A 2023 study developed a deep learning model, MnEdgeNet, to decompose mixed Mn oxidation states from XAS and EELS L2,3 edge data, directly addressing pitfalls of traditional linear combination analysis. [18]

| Technique | Challenge / Pitfall | Multi-Technique / Model Solution |

|---|---|---|

| XAS & EELS L2,3 Edge Analysis | Traditional linear combination analysis requires reference spectra from the same instrument/session to avoid errors from energy calibration offsets and instrumental broadening. [18] | A deep learning model was trained on a synthetic library of 1.2 million spectra, incorporating physics-informed variations like energy offset and plural scattering, making it calibration- and reference-free. [18] |

| EELS Specificity | Spectral fine structures change with sample thickness due to plural scattering (the "thickness effect"), altering the L2/L3 ratio and leading to inaccurate decomposition. [18] | The training library explicitly included a forward model for plural scattering, making the final model robust against thickness effects (up to t/λ = 1). [18] |

| Validation | -- | The model was quantitatively validated on experimental Mn3O4 (Mn2+, Mn3+) data not used in training, achieving high accuracy and demonstrating real-world applicability. [18] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility, here are detailed methodologies for key techniques discussed.

This protocol describes the integrated computational workflow for simulating platinum nanoparticle oxidation.

1. System Preparation:

- Begin with an experimentally reconstructed nanoparticle structure (e.g., a 353-atom Pt nanoparticle from STEM data [19]).

- Grand-Canonical Monte Carlo/Molecular Dynamics (MC-MD): Perform hybrid MC-MD simulations using a forcefield (e.g., ReaxFF) in the LAMMPS software. Set the oxygen chemical potential based on the desired partial pressure (e.g., from 10-25 to 1.0 atm at 350 K). Continue until acceptance rates for addition/deletion moves stabilize.

2. Configuration Sampling and Relaxation:

- Extract multiple geometries (e.g., 32 configurations) from the high-pressure simulation at evenly spaced oxygen coverages.

- Subject each geometry to a further NVT-MD simulation (e.g., 100 ns at 350 K) without MC moves to allow structural relaxation and amplify features like oxide clusters.

- Select the most stable configuration from the final segment of each trajectory (e.g., the last 1 ns) for optimization.

3. High-Fidelity Optimization and Electronic Structure Analysis:

- Optimize the selected relaxed geometries using both the original forcefield (e.g., ReaxFF) and a higher-accuracy universal model (e.g., MACE-MP-0).

- Perform Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations on the optimized structures using linear-scaling DFT software (e.g., ONETEP) with a PBE functional. This step provides the final electronic structure and validates the energetics predicted by the forcefields.

This protocol outlines a multi-technique electrochemical approach to evaluate corrosion inhibitors for mild steel.

1. Sample and Solution Preparation:

- Working Electrode: Use mild steel specimens (e.g., composition: 2.00 wt.% Mg, 0.50 wt.% Fe, 0.50 wt.% Mn...). Embed in epoxy resin to expose a defined surface area (e.g., 1.0 cm2).

- Surface Preparation: Polish the exposed surface successively with emery papers (e.g., grades 100 to 2000), degrease with ethanol, and dry with compressed air.

- Electrolyte: Prepare a 1.0 M HCl solution by diluting concentrated acid with deionized water.

- Inhibitors: Dissolve the compounds under investigation (e.g., a benzimidazole-thiophene ligand and its Zn/Cu complexes) in the electrolyte at the desired concentration (e.g., 1 × 10-3 M).

2. Electrochemical Measurement Sequence:

- Employ a standard three-electrode cell: mild steel as the working electrode, a platinum counter electrode, and an Ag/AgCl reference electrode.

- Stabilization: Immerse the working electrode in the test solution at open circuit potential (OCP) for 60 minutes at 298 K to reach a steady state.

- Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): Record spectra in a frequency range from 100 kHz to 100 mHz with a 10 mV amplitude.

- Potentiodynamic Polarization (PDP): Obtain curves with a sweep rate of 1 mV/s in a potential range from -250 mV to +250 mV vs. Ecorr.

- Linear Polarization Resistance (LPR): Record data at a scan rate of 1 mV/s from -25 mV to +25 mV around Ecorr.

3. Surface Analysis:

- After electrochemical testing, analyze the electrode surface using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) to observe morphology and elemental composition.

- Use X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) with an Al Kα source to characterize the chemical states of elements within the protective film formed by the inhibitor.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function / Role in Research |

|---|---|

| Reference Materials (e.g., MnO, Mn2O3, MnO2) | Essential for calibrating XAS and EELS measurements to establish a baseline for specific oxidation states (Mn2+, Mn3+, Mn4+). [18] |

| Experimentally Reconstructed Nanoparticles | Provides a realistic, non-idealized starting structure for computational studies, leading to more accurate simulations of properties like oxidation behavior. [19] |

| High-Accuracy Forcefields (e.g., MACE-MP-0) | Machine learning-potentials offering higher fidelity predictions of energetics and structures compared to traditional forcefields like ReaxFF, crucial for validating computational findings. [19] |

| Heterocyclic Organic Ligands (e.g., with N, S atoms) | Serve as effective corrosion inhibitors or complexing agents; their high electron density facilitates strong adsorption onto metal surfaces. [21] |

| Organometallic Complexes (e.g., Zn/Cu with organic ligands) | Can exhibit synergistic corrosion inhibition, where the metal center and organic ligand work together to enhance protective film formation and performance. [21] |

The path to reliable oxidation state characterization is fraught with pitfalls, from instrumental miscalibration and sample effects to inadequate statistical power and flawed computational models. As the comparative data and protocols in this guide demonstrate, no single technique is infallible. A thoughtfully designed, multi-technique workflow that cross-validates findings between computational simulation, electrochemical analysis, and multiple spectroscopic methods is not merely beneficial—it is essential for producing robust, reproducible, and conclusive scientific results.

A Toolkit for Oxidation State Analysis: From Computation to Experiment

In both inorganic chemistry and materials science, the formal oxidation state (OS) of a metal is a fundamental concept that provides critical insight into chemical reactivity, catalytic behavior, and material properties. Despite its conceptual importance, the oxidation state lacks a rigorous quantum mechanical definition, as electron density in compounds is global and cannot be precisely partitioned using first principles alone [8]. This theoretical ambiguity necessitates robust methods for OS assignment that combine computational predictions with experimental validation. The accurate determination of oxidation states is particularly crucial for transition metals, which commonly exhibit multiple oxidation states that directly influence their chemical functionality [7]. Within this context, complementary validation approaches have emerged as essential for verifying computational predictions, forming a foundational thesis that integrated methodologies provide the most reliable OS assignments in complex solid-state systems and molecular structures.

Model Comparison: Methodologies and Performance

The landscape of computational OS prediction is diverse, encompassing approaches from first-principles calculations to purely data-driven algorithms. The table below provides a systematic comparison of three distinct modeling approaches.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Oxidation State Prediction Models

| Model | Computational Approach | Primary Input Data | Key Advantages | Reported Accuracy | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOSS | Data-driven paradigm using Bayesian maximum a posteriori probability (MAP) and distance distributions [8] | Crystal structures | High interpretability through emergent distance thresholds; 96.09% accuracy on curated ICSD dataset [8] | 96.09% (TOSS), 97.24% (TOSS-GCN) on benchmark ICSD dataset [8] | Requires large datasets for optimal performance |

| BERTOS | Composition-based machine learning model [8] | Chemical composition only | Rapid prediction without need for structural data [8] | Information not available in search results | Lacks structural sensitivity for complex bonding environments |

| DFT+U | Ab initio DFT with Hubbard correction for strongly correlated electrons [22] | First-principles electronic structure calculation | Directly models electronic properties; captures localized electrons [22] | Dependent on U parameter choice and method to avoid metastable states [22] | Computationally intensive; susceptible to metastable states [22] |

As evidenced in Table 1, each modeling approach offers distinct advantages that suit different application scenarios. TOSS excels in providing chemically intuitive OS assignments derived from structural data, while BERTOS offers speed for high-throughput screening, and DFT+U provides fundamental electronic insights despite its computational demands.

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

TOSS Workflow and Implementation

The TOSS methodology employs a sophisticated two-loop structure to determine oxidation states from crystal structures:

Dataset Preparation and Preprocessing: The initial stage involves curating a large dataset of crystal structures. In the referenced implementation, structures from the Materials Project and Open Quantum Materials Database were combined and preprocessed using the "Get Structures" and "Pre-Set Features" modules [8].

Distance Threshold Abstraction: In the first looping structure, TOSS abstracts distance thresholds—defined as the longest bond length counted as coordination between element pairs—by "learning" over all atomic structures in the dataset repeatedly until convergence. These thresholds are initialized at 1.5 times the sum of Pyykkö's single-bond covalent radii but evolve to dataset-emergent values independent of initial guesses [8].

Oxidation State Determination: The second looping structure implements a "practicing" phase over all atomic structures to determine OSs by minimizing a loss function for each structure based on Bayesian maximum a posteriori probability (MAP) and distance distributions across the entire dataset [8].

Local Coordination Analysis: For each atomic site, a sphere is defined using the distance to its nearest neighbor multiplied by a tolerance parameter (t values from 1.1 to 1.25 in steps of 0.01). Within this sphere, the coordination environment is determined using the abstracted thresholds [8].

Model Validation: The TOSS implementation was benchmarked against a curated ICSD dataset with human-assigned OS labels, achieving 96.09% accuracy, while its GCN-based derivative reached 97.24% accuracy [8].

Complementary Experimental Validation Techniques

Computational OS predictions require experimental validation to confirm their accuracy, with several techniques serving as reference standards:

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): This surface-sensitive technique quantitatively determines oxidation states by measuring the kinetic energy of emitted electrons to obtain element-specific binding energies. Different oxidation states produce characteristic binding energy shifts, enabling discrimination between species like MoS₂ and MoO₃ [9]. One significant limitation is that the X-ray irradiation may reduce high oxidation states, potentially compromising accuracy [14].

Bond Valence Sum (BVS) Method: This approach calculates oxidation states from experimentally determined bond lengths in crystal structures. The method uses both chemical connectivity and bond-length data via ligand donor group templates and bond-valence sums, successfully validating +1, +2, and +3 oxidation states in copper complexes with approximately 99% reliability in compatible structures [23].

Chemical Clock Reactions: An innovative approach uses formaldehyde clock systems (HCHO-NaHSO₃-Na₂SO₃) to distinguish oxidation states based on their differential effects on induction periods. For iron species, K₂FeO₄ decreases the induction period, FeCl₃ increases it, while FeCl₂ has no effect on induction but reduces the pH jump slope, enabling discrimination in the concentration range of 2.0×10⁻⁴−1.2×10⁻³ mol L⁻¹ [14].

Integrated Workflow for Oxidation State Determination

The complementary relationship between computational prediction and experimental validation can be visualized through the following workflow:

Computational and Experimental Oxidation State Workflow

This diagram illustrates the integrated approach where computational models generate initial predictions that are subsequently verified through multiple experimental techniques to achieve validated oxidation state assignments.

Research Reagent Solutions for Oxidation State Analysis

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Oxidation State Determination

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Formaldehyde Clock System (HCHO-NaHSO₃-Na₂SO₃) | pH-based discrimination of oxidation states via induction period modulation [14] | Qualitative identification of Fe(VI), Fe(III), and Fe(II) species |

| X-ray Photoelectron Spectrometer | Quantitative determination of elemental oxidation states via binding energy measurements [9] | Surface analysis of oxidation states in solid materials |

| Reference Crystalline Structures | Provides benchmark data with human-validated oxidation states [8] | Validation of computational prediction algorithms |

| Bond Valence Parameters | Empirical relationships between bond lengths and oxidation states [8] | Oxidation state assignment from crystallographic data |

The comparative analysis of DFT+U+V, BERTOS, and TOSS models reveals a sophisticated landscape of computational approaches for oxidation state prediction, each with distinct strengths and limitations. TOSS demonstrates exceptional accuracy in structural OS assignment through its innovative data-driven paradigm, while BERTOS offers rapid composition-based screening, and DFT+U provides fundamental electronic structure insights. The broader thesis of oxidation state validation is fundamentally strengthened by complementary techniques, where computational predictions and experimental measurements converge to provide reliable OS assignments. This integrated approach enables researchers to navigate the complex electronic landscapes of transition metal compounds with greater confidence, ultimately accelerating materials discovery and catalyst development through more accurate structural-property relationships.

Validating metal oxidation states is a fundamental challenge in inorganic chemistry and materials science, crucial for understanding the properties of catalysts, battery materials, and pharmaceuticals. Among the most widely used computational approaches for this task are the Bond Valence Method (BVM) and Local Coordination Environment (LCE) analysis. While BVM leverages the empirical relationship between bond lengths and bond valence to estimate oxidation states, LCE analysis determines oxidation states by statistically comparing a site's local environment to large crystallographic databases. This guide provides an objective comparison of these complementary techniques, supporting researchers in selecting the appropriate method for validating metal oxidation states in solid-state materials.

Theoretical Foundations

Bond Valence Method (BVM)

The Bond Valence Method is based on the principle that the sum of the bond valences around an atom equals its atomic valence, which is equivalent to its oxidation state [24]. The most common form of the relationship between bond valence and bond length was established by Brown & Altermatt [24]:

[ s{ij} = \exp\left(\frac{R0 - R_{ij}}{B}\right) ]

Where:

- ( s_{ij} ) is the bond valence between atoms i and j (in valence units, v.u.)

- ( R_{ij} ) is the observed bond length (in Ångströms)

- ( R_0 ) is a fitted parameter representing the bond length corresponding to a unit valence

- ( B ) is a universal "softness" parameter, often fixed at 0.37 Å [24]

The bond valence sum (BVS) for a cation is then calculated as:

[ Vi = \sumj s_{ij} ]

This sum should equal the formal oxidation state of the cation according to the valence-sum rule [24].

Local Coordination Environment Analysis

Local Coordination Environment analysis determines oxidation states through data-driven paradigms that examine the complete local surroundings of a metal center. Unlike BVM, which relies primarily on bond lengths, LCE analysis considers multiple geometric and chemical factors, including:

- Bond length distributions to all neighboring atoms

- Coordination numbers and polyhedron geometry

- Chemical identity of coordinating atoms

- Statistical patterns learned from large crystallographic databases [8]

Advanced implementations like the Tsinghua Oxidation States in Solids (TOSS) algorithm employ Bayesian maximum a posteriori probability to determine the most probable oxidation state by minimizing a loss function based on distance distributions across an entire dataset [8].

Methodological Comparison

Experimental Protocols

Bond Valence Method Protocol

Required Input Data:

- Crystallographic coordinates (CIF format preferred)

- Bond valence parameters (( R_0 ) and ( B )) for relevant atom pairs

Procedure:

- Identify Coordination Environment: Determine all bonds between the central metal atom and surrounding ligands within the first coordination shell [25].

- Measure Bond Lengths: Calculate all metal-ligand distances from the crystal structure.

- Calculate Bond Valences: Apply the Brown & Altermatt equation to compute individual bond valences.

- Sum Bond Valences: Add all bond valences to obtain the Bond Valence Sum.

- Compare to Oxidation State: Check agreement between BVS and expected oxidation state.

Validation: A successful application typically shows a deviation of <0.1-0.2 valence units from the expected oxidation state [24].

Local Coordination Environment Analysis Protocol

Required Input Data:

- Crystallographic coordinates

- Access to a large database of known structures (e.g., ICSD, Materials Project)

- Pre-trained models for coordination environment classification

Procedure (TOSS Algorithm Example):

- Structure Preprocessing: Standardize crystal structure representation and identify unique atomic sites [8].

- Local Environment Analysis: For each atomic site, define a sphere using the distance to its nearest neighbor multiplied by a tolerance parameter (typically 1.1 to 1.25) [8].

- Threshold Determination: Abstract distance thresholds for each element pair by "learning" over all atomic structures in the dataset [8].

- Constituent Identification: Within the sphere, determine the coordination environment based on converged thresholds.

- Oxidation State Assignment: Determine oxidation states by "practicing" over all atomic structures to minimize a loss function for each structure based on Bayesian maximum a posteriori probability and distance distributions [8].

Performance Metrics and Comparative Data

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of BVM and LCE Analysis Techniques

| Parameter | Bond Valence Method | Local Coordination Environment Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Empirical bond length-bond valence relationship | Statistical analysis of coordination patterns in large datasets |

| Primary Input | Bond lengths, bond valence parameters | Complete crystal structure, reference database |

| Accuracy | RMSD: 0.128-0.174 v.u. for best parameters [24] | 96.09-97.24% accuracy vs. human-assigned labels [8] |

| Key Limitations | Limited by available bond valence parameters; transferability issues for unusual oxidation states [8] | Requires large reference datasets; performance depends on database quality |

| Computational Demand | Low; simple calculations | High; requires significant processing for large datasets |

| Best Applications | Single-structure analysis; materials with established parameters | High-throughput screening; novel materials with unusual coordination |

Table 2: Performance of BVM Parameter Derivation Methods

| Method | Weighted RMSD (v.u.) | Error per Unit Charge | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed B (B=0.37 Å) | 0.139 | 6.7% | Simple, widely implemented [24] |

| Graphical Method | 0.161 | 8.0% | Visual fitting, less precise [24] |

| GRG Method | 0.128 | 6.1% | Optimized generalized reduced gradient; most accurate [24] |

Applications in Materials Research

Structural Validation and Plausibility Testing

Both BVM and LCE analysis serve as powerful tools for validating crystal structures and identifying potentially erroneous determinations. The Bond Valence Method is particularly effective for rapid plausibility checks of proposed structures, especially when using bond-softness sensitive parameters that account for the polarizability of ions [25]. Recent advances in bond valence parameters, such as the softNC1 parameter set, significantly improve performance for bonds involving soft anions by systematically adapting parameters to bond softness [25].

Oxidation State Determination in Complex Systems

Local Coordination Environment analysis excels in determining oxidation states in complex systems where traditional BVM may struggle, including:

- Mixed-valence compounds: Where metal centers exist in multiple oxidation states

- Novel materials: With unusual coordination environments or oxidation states

- High-throughput screening: Rapid classification of oxidation states across large materials databases [8]

The TOSS algorithm demonstrates how data-driven approaches can achieve high accuracy (96.09%) by leveraging emergent patterns across thousands of structures, effectively capturing chemical intuition in a computational framework [8].

Specialized Applications

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Oxidation State Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| softNC1 Parameters | Bond-softness sensitive parameters for BVM | Improved plausibility checks for crystal structures [25] |

| TOSS Algorithm | Data-driven oxidation state assignment | High-throughput oxidation state determination [8] |

| ICSD Database | Curated crystal structure repository | Reference data for both BVM and LCE analysis [24] [8] |

| Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) | Machine learning model for OS prediction | Alternative to TOSS with 97.24% accuracy [8] |

Integrated Workflow and Decision Framework

When to Use Each Method

Choose Bond Valence Method when:

- Analyzing materials with established bond valence parameters

- Performing rapid, single-structure plausibility checks

- Working with systems where coordination environments are well-defined

- Seeking computationally lightweight approaches [24]

Choose Local Coordination Environment Analysis when:

- Validating oxidation states in novel materials with unusual coordination

- Processing large datasets for high-throughput screening

- Analyzing mixed-valence compounds

- Dealing with systems where bond valence parameters are unavailable or unreliable [8]

Synergistic Applications

For the most robust oxidation state validation, particularly in research contexts requiring high confidence, researchers should employ both techniques synergistically:

- Primary Screening: Use LCE analysis for initial oxidation state assignment, particularly for novel materials

- Detailed Validation: Apply BVM with optimized parameters (e.g., GRG-derived or softNC1) for specific metal sites

- Cross-Validation: Compare results from both methods to identify discrepancies that may indicate structural issues or unusual bonding

This combined approach leverages the statistical power of data-driven LCE analysis with the chemical intuition embedded in the Bond Valence Method, providing comprehensive oxidation state validation for diverse research applications.

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) stands as a cornerstone technique for surface chemical analysis, particularly for determining elemental composition and chemical oxidation states. The technique operates on the principle of irradiating a solid surface in a vacuum with X-rays, causing the emission of photoelectrons whose kinetic energy is measured and converted to binding energy—a characteristic value for each element and its chemical environment [26]. The surface sensitivity of XPS, typically probing the outermost 1-10 nm of a material, makes it indispensable for studying surface reactions, corrosion, catalysis, and lubrication where surface oxidation states dictate material behavior [26]. This guide provides a comparative assessment of XPS against complementary techniques for validating metal oxidation states, with particular focus on experimental methodologies, limitations, and data interpretation challenges encountered in practical research settings.

The fundamental premise for oxidation state analysis rests on "chemical shifts"—changes in core electron binding energies that occur with variations in ionic and covalent bonding environments [26]. For transition metals specifically, these shifts manifest as distinct peaks in high-resolution spectra, enabling researchers to distinguish between different oxidation states through careful peak fitting and reference to standard materials [26]. However, recent research has revealed significant limitations to this established approach, particularly when analyzing nanomaterials where quantum confinement effects and reduced dimensionality alter the expected correlation between binding energy and oxidation state [27].

Comparative Performance Analysis: XPS vs. Complementary Techniques

Technical Comparison of Analytical Methods

Table 1: Comparison of Techniques for Metal Oxidation State Analysis

| Technique | Analytical Depth | Oxidation State Sensitivity | Quantification Capability | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XPS | 1-10 nm [26] | High for most elements [26] | Semi-quantitative (atomic %); Linear fitting possible with standards [26] | Vacuum required; Surface damage possible; Complex peak fitting for transition metals [26] |

| qNMR | Bulk technique [28] | Limited to specific functional groups [28] | Highly accurate and traceable for surface groups [28] | Requires extraction/dissolution; Not surface-specific [28] |

| TGA | Bulk technique [28] | Indirect through mass changes | Quantitative for surface groups [28] | Destructive; Requires complementary techniques for structural info [28] |

| ICP-MS | Bulk technique [28] | Elemental composition only | Highly accurate for elemental composition [28] | Destructive; Not surface-specific [28] |

Quantitative Performance Data for Iron Oxidation States

Table 2: XPS Analysis of Mixed Iron Oxidation State Sample [26]

| Oxidation State | Relative Percentage | Experimental Error |

|---|---|---|

| Fe(0) | 28% | ±2% |

| Fe(II) | 41% | ±5% |

| Fe(III) | 32% | ±6% |

The data in Table 2 demonstrates XPS capability for quantifying mixed oxidation states in iron samples, with varying precision across different states. The analysis was performed using reference spectra from standards as basis functions for linear peak fitting, avoiding the need for complex analytical functions to describe peak shapes [26]. This approach highlights both the quantitative potential of XPS and the importance of appropriate reference materials for accurate speciation.

Experimental Protocols for Oxidation State Validation

Standard Preparation Methodology

Preparation of reliable standards forms the foundation of accurate XPS oxidation state analysis. For iron oxidation state analysis, researchers have employed the following standardized approaches [26]:

- Fe(0) Standard: Iron foil cleaned by argon ion sputtering to remove surface oxides

- Fe(II) Standard: Iron oxide film heated under vacuum to achieve specific stoichiometry

- Fe(III) Standard: High-purity Fe₂O₃ powder (99.9995+%)

These standards produce distinct spectral features including chemical shifts, asymmetric peaks, spin-orbit coupling, multiplet splitting, and shake-up satellites that serve as fingerprints for each oxidation state [26]. When analyzing unknown samples, linear combinations of these reference spectra enable quantification of mixed oxidation states as demonstrated in Table 2.

XPS Data Collection and Analysis Protocol

Comprehensive XPS analysis follows a systematic workflow to ensure reliable data collection and interpretation [28] [29]:

- Sample Preparation: Minimal preparation required beyond mounting; compatible with powder or solid forms [28]

- Data Acquisition: Collect both survey scans (for elemental composition) and high-resolution regional scans (for chemical state analysis) [28]

- Background Subtraction: Remove inelastic backgrounds using established methods (e.g., Tougaard method) [26]

- Peak Fitting: Use reference spectra from standards as basis functions rather than purely analytical approaches to avoid highly correlated parameters [26]

- Quantification: Calculate relative atomic percentages from peak areas with sensitivity factors

Recent research proposes a "constant signal, variable time" (CSVT) approach as an alternative to traditional "variable signal, constant time" spectral collection, potentially offering better visual comparisons and more rigorous statistical analysis through paired t-tests [30]. Though currently a theoretical concept, this innovation highlights the ongoing evolution of XPS methodology.

In Situ Experimental Design

For oxidation state studies requiring environmental control, in situ XPS methodologies provide crucial insights. For example, tracking oxidation state changes during heating can reveal reduction/oxidation mechanisms [26]:

- An Fe(110) single crystal oxidized with ~4,000 L of pure oxygen in a vacuum chamber

- Subsequent heating to 800°C while collecting sequential XPS spectra

- Analysis of peak position and structure changes throughout the thermal treatment

- Quantification of relative oxidation state proportions versus temperature

This approach demonstrated near-complete reduction to iron metal at elevated temperatures, highlighting the dynamic nature of surface oxidation states under different conditions [26].

Figure 1: XPS Oxidation State Analysis Workflow. This diagram outlines the standardized protocol for validating metal oxidation states using XPS, highlighting key steps from sample preparation through multi-technique validation.

Critical Limitations and Methodological Considerations

Sub-Nanoscale Breakdown of Traditional Interpretation

A significant limitation of conventional XPS interpretation emerges at the sub-nanoscale, where the established correlation between binding energy and oxidation state can break down completely. Research on size-selected Ag₇ and Ag₁₁ clusters supported on graphene revealed anomalous Ag 3d₅/₂ core level shifts upon increasing oxygen coverage [27]. Unlike bulk materials, ultra-thin films, and surface oxides where binding energy typically increases with oxidation state, these nanoclusters exhibited a negative core level shift trend that reverted only at the highest Ag(III) oxidation state [27].

This phenomenon is attributed to quantum size effects and the unique electronic structure of zero-dimensional materials, where reduced coordination and quantum confinement significantly alter initial and final state effects [27]. The practical implication is profound: researchers analyzing nanomaterials cannot automatically extrapolate from bulk material reference data and must develop cluster-specific standards for accurate oxidation state assignment.

Common Analytical Errors and Quality Control

Despite established protocols, numerous errors persist in XPS data collection, analysis, and reporting [29]. Common issues include:

- Improper Background Handling: Incorrect background subtraction can significantly alter peak shapes and ratios

- Peak Fitting Problems: Overfitting, use of inappropriate line shapes, and failure to respect chemical constraints

- Insufficient Reporting: Missing critical instrument parameters that prevent experimental reproducibility

- Surface Damage: X-ray induced sample damage that alters oxidation states during measurement

Quality control measures should include validation with reference materials when available, consistency checks between survey and high-resolution scans, and correlation with complementary techniques when possible [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for XPS Oxidation State Analysis

| Material/Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Metal Foils (e.g., Iron foil) | Primary standards for zero-valent state [26] | Must be cleaned by argon ion sputtering before use [26] |

| Metal Oxide Powders (e.g., Fe₂O₃, 99.9995+%) | Reference standards for specific oxidation states [26] | Purity critical; surface contamination can affect results [26] |

| Aminopropyl Triethoxy Silane (APTES) | Surface functionalization for nanoparticle studies [28] | Introduces nitrogen marker for XPS quantification of surface groups [28] |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | Polymer coating for nanoparticle stabilization [28] | Contains unique elements (N, O) for XPS tracking of surface coverage [28] |

| Stearic Acid | Surface coating for functionalized nanoparticles [28] | Provides distinct carbon signature in XPS for coating quantification [28] |

| Argon Gas Supply | Surface cleaning via ion sputtering | Essential for preparing standard surfaces and depth profiling |

Integrated Validation Strategy: Correlative Microscopy Approach

Given the limitations of individual techniques, a correlative approach combining XPS with complementary methods provides the most robust validation of metal oxidation states. The integrated workflow should include:

- XPS Primary Analysis: Initial surface composition and oxidation state assessment

- qNMR Cross-Validation: Quantitative functional group analysis for organic coatings [28]

- TEM Size Characterization: Critical for nanoparticle studies where size affects electronic structure [27] [28]

- Bulk Composition Verification: ICP-MS for total elemental composition [28]

This multi-technique approach is particularly crucial for commercial nanomaterials where supplier specifications are often incomplete or unreliable, and surface composition may differ significantly from bulk properties [28]. Studies have revealed substantial impurities and oxidation state variations in commercially available metal oxide nanoparticles, highlighting the importance of comprehensive characterization for both applications development and environmental health studies [28].

Figure 2: Multi-Technique Validation Strategy. This diagram illustrates the correlative approach essential for robust oxidation state validation, combining surface-sensitive (XPS), bulk (ICP-MS, TGA), and structural (TEM) techniques with quantitative NMR.

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy remains an indispensable tool for surface-specific oxidation state analysis, but its effective application requires careful attention to methodological details, recognition of its limitations particularly at the nanoscale, and correlation with complementary analytical techniques. The comparative data and experimental protocols presented here provide a framework for researchers to design rigorous oxidation state validation studies, while the identified limitations highlight areas where conventional interpretation methods may require revision. As nanomaterials continue to gain importance across scientific and technological fields, the nuanced application of XPS in conjunction with other techniques will be essential for accurate materials characterization.

Leveraging Machine Learning Potentials for Redox-Aware Property Prediction

The accurate prediction and validation of metal oxidation states represents a cornerstone in the development of advanced materials, particularly for energy storage, catalysis, and drug development. Oxidation states (OS) are defined as the charges on atoms due to electrons gained or lost upon applying an ionic approximation to their bonds, serving as fundamental attributes that explain redox reactions, chemical bonding, and material properties [31]. The evolution of oxidation states follows redox reactions, electrolysis, and other crucial electrochemical processes that underpin contemporary technologies [5] [32]. Despite their importance, accurately describing redox reactions remains challenging for first-principles calculations due to self-interaction errors that cause unphysical electron delocalization, particularly in systems with strongly localized d or f electrons [5]. This comprehensive analysis compares emerging machine learning approaches for redox-aware property prediction, providing researchers with validated methodologies for oxidation state validation in complex material systems.

Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Approaches for Redox Property Prediction

Table 1: Comparison of Machine Learning Approaches for Redox-Aware Property Prediction

| Methodology | Key Features | Accuracy Performance | Computational Efficiency | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ML-Augmented First-Principles Calculations [33] [34] | Combines ML force fields with thermodynamic integration; uses Δ-machine learning for free energy refinement | Predicts Fe³⁺/Fe²⁺: 0.92 V (expt: 0.77 V); Cu²⁺/Cu⁺: 0.26 V (expt: 0.15 V); Ag²⁺/Ag⁺: 1.99 V (expt: 1.98 V) [33] [34] | High computational cost for hybrid functionals; ML force fields improve sampling efficiency | High-accuracy redox potential prediction for metal ions in solution; battery and electrocatalyst design |

| Redox-Aware Machine Learning Potentials [5] [32] | Treats atoms with different oxidation states as distinct species; utilizes equivariant neural networks (NequIP, MACE) | Accurately reproduces adiabatic ground state and oxidation state patterns from DFT+U+V [5] | First-principles accuracy at classical force field cost; minimal training data requirements | Transition metal oxides; battery cathode materials (e.g., LixMnPO4); finite-temperature MD simulations |

| Composition-Based Deep Learning (BERTOS) [31] | Transformer language model for OS prediction from chemical composition alone | 96.82% accuracy for all-element prediction; 97.61% accuracy for oxide materials [31] | Rapid screening without structural information; enables high-throughput composition design | Large-scale screening of hypothetical materials; charge-neutrality verification; generative material discovery |

| Redox Potential Prediction (OxPot) [35] | Combines DFT-calculated EHOMO with experimental correlation; various ML algorithms | R² = 0.977 for EHOMO vs. experimental Eox correlation; RMSE = 0.064 [35] | High-throughput capability for large chemical libraries; fast predictions at fraction of DFT cost | Organic molecule screening for redox flow batteries; electrolyte design; photovoltaics |

Table 2: Experimental Validation Performance of Formaldehyde Clock System for Iron Oxidation State Identification [14]

| Analyte | Effect on Induction Period | Effect on pH Jump Slope | Linear Concentration Range (mol L⁻¹) | Identification Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K₂FeO₄ (Fe(VI)) | Decrease | Not specified | 2.0 × 10⁻⁴ to 1.2 × 10⁻³ | Redox reaction with NaHSO₃/Na₂SO₃ |

| FeCl₃ (Fe(III)) | Increase | Not specified | 2.0 × 10⁻⁴ to 1.2 × 10⁻³ | Interaction with clock system components |

| FeCl₂ (Fe(II)) | No effect | Reduction | 2.0 × 10⁻⁴ to 1.2 × 10⁻³ | Indirect effect on system kinetics |

Experimental Protocols for Oxidation State Validation

Formaldehyde Clock System for Iron Oxidation State Identification

The formaldehyde clock system provides a straightforward experimental method for distinguishing between different iron oxidation states through their distinctive effects on reaction kinetics [14]. The detailed methodology encompasses the following steps:

Reagent Preparation: Prepare 0.12 mol L⁻¹ sodium bisulfite (NaHSO₃) and 0.012 mol L⁻¹ sodium sulfite (Na₂SO₃) mixed solution in distilled water. Separately, prepare 0.18 mol L⁻¹ formaldehyde (HCHO) solution using distilled water as the solvent.

System Assembly: Combine 10 mL distilled water, 18 mL of the NaHSO₃/Na₂SO₃ mixed solution, and 12 mL of 0.18 mol L⁻¹ HCHO solution sequentially in a 50 mL batch reactor. The final concentrations in the system will be [HCHO] = 0.054 mol L⁻¹ and [NaHSO₃/Na₂SO₃] = 0.054/0.0054 mol L⁻¹.

Kinetic Monitoring: Immerse a pH electrode (type E-201-C) into the reaction mixture with continuous homogenization using a magnetic stirrer at 530 rpm. Connect the electrode to a potential/temperature/pH comprehensive tester (type ZHFX-595) and record pH versus time data using an eight-channel chemical signal acquisition system.

Analyte Introduction: Introduce iron species (K₂FeO₄, FeCl₃, or FeCl₂) at concentrations ranging from 2.0 × 10⁻⁴ to 1.2 × 10⁻³ mol L⁻¹ into the clock system. Monitor changes in the induction period and pH jump characteristics.

Data Interpretation: Identify iron oxidation states based on their characteristic effects: decreased induction period for Fe(VI), increased induction period for Fe(III), and no effect on induction period but reduced pH jump slope for Fe(II) [14].

Experimental Workflow for Iron Oxidation State Identification Using Formaldehyde Clock System

Machine Learning-Aided First-Principles Calculation of Redox Potentials

The integration of machine learning with first-principles calculations enables high-accuracy prediction of redox potentials through a multi-step refinement process [33] [34]:

System Setup: Construct simulation cells containing the redox-active species (e.g., Fe³⁺, Fe²⁺) solvated in water molecules. For transition metal cations, use approximately 64 water molecules to ensure proper solvation.

Free Energy Calculation: Employ thermodynamic integration (TI) to compute the free energy difference between oxidized and reduced states using the formula: ΔA = ∫₀¹ ⟨∂H/∂λ⟩λ dλ, where λ couples the oxidized (λ=0) and reduced (λ=1) states.

Machine Learning Force Fields: Utilize ML force fields for efficient statistical sampling over broad phase space during thermodynamic integration, significantly reducing computational cost compared to direct hybrid functional calculations.

Multi-Step Refinement: Apply Δ-machine learning to refine free energy calculations from ML force fields to semi-local functionals, and subsequently from semi-local to hybrid functionals (e.g., PBE0 with 25% exact exchange).

Reference Potential Alignment: Use the O 1s level of water as an internal reference point instead of the vacuum level to establish an absolute potential scale, correcting for finite-size errors in periodic boundary condition calculations.

Validation: Compare predicted redox potentials against experimental values for benchmark systems (Fe³⁺/Fe²⁺, Cu²⁺/Cu⁺, Ag²⁺/Ag⁺) to validate methodology before application to unknown systems.

Research Reagent Solutions for Redox Property Analysis

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Redox Property Prediction

| Reagent/Software Tool | Function/Purpose | Application Context | Key Features/Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formaldehyde Clock System [14] | Identification of iron oxidation states (Fe(VI), Fe(III), Fe(II)) | Experimental validation of oxidation states in aqueous systems | Simple operation, low cost, fast analysis (minutes), distinguishes multiple oxidation states |

| DFT+U+V Methodology [5] [32] | First-principles calculation with extended Hubbard functionals | Accurate description of redox reactions in transition metal oxides | Mitigates self-interaction errors, provides sharp "digital" changes in oxidation states, material-specific parameters |

| BERTOS Model [31] | Composition-based oxidation state prediction | High-throughput screening of hypothetical material compositions | 96.82% prediction accuracy, requires only chemical composition, no structural information needed |

| OxPot Dataset [35] | Redox potential prediction for organic molecules | Screening organic electrolytes for energy storage applications | Contains 15,238 organic molecules, strong EHOMO to Eox correlation (R²=0.977), aqueous phase focus |

| RedCat Workflow [36] | Automated discovery of redox-active organic electrolytes | Screening large molecular databases for battery applications | Integrates similarity filtering, property prediction, and commercial availability assessment |

The validation of metal oxidation states requires a complementary approach combining computational predictions with experimental verification. Machine learning potentials for redox-aware property prediction have demonstrated remarkable accuracy, with composition-based models achieving 96.82% accuracy for oxidation state assignment [31] and ML-augmented first-principles calculations predicting redox potentials within 0.11 V RMSE of experimental values [33] [34]. For researchers pursuing drug development or materials design, the strategic integration of multiple validation techniques—from the simple formaldehyde clock system for initial screening to sophisticated ML-potentials for detailed mechanism studies—provides a robust framework for redox property characterization. The experimental protocols and comparative performance data presented herein offer a foundation for selecting appropriate methodologies based on specific research requirements, balancing accuracy, computational cost, and experimental complexity.

Resolving Discrepancies and Optimizing Analysis in Complex Systems

Addressing Self-Interaction Errors in DFT for Accurate Redox Description

The accurate computational description of redox processes is fundamental to advancements in energy storage, catalysis, and drug development. Density Functional Theory (DFT) is a cornerstone method for modeling electronic structures; however, its standard approximations suffer from self-interaction errors (SIEs), which lead to an unphysical delocalization of electrons [37] [5]. This flaw severely compromises the accurate prediction of key redox properties, including oxidation states (OS) and redox potentials, particularly in systems with strongly localized d or f electrons, such as transition metal complexes and oxides prevalent in battery materials and metallodrugs [37] [5] [38]. For researchers validating metal oxidation states, recognizing and mitigating SIEs is not merely an academic exercise but a critical step in ensuring computational models yield reliable, experimentally verifiable data. This guide provides a comparative analysis of leading strategies to overcome SIEs, equipping scientists with the knowledge to select the optimal approach for their specific redox-related challenges.

Self-Interaction Errors and Their Impact on Redox Properties

The SIE arises because the electron in a standard DFT calculation incorrectly interacts with itself. This error is particularly pronounced in local and semi-local exchange-correlation functionals (e.g., LDA and GGA). In redox-active systems, the consequences are manifold:

- Unphysical Electron Delocalization: SIEs prevent the correct localization of electrons on transition metal centers, blurring the distinct electronic configurations associated with different oxidation states [37] [5]. For instance, in Li-ion cathode materials like Li(x)MnPO(4), standard DFT may fail to produce the sharp, "digital" changes in the Mn oxidation state that occur during (de)intercalation [37] [5].

- Inaccurate Redox Potentials: The spurious electron delocalization stabilizes charged states (oxidized or reduced forms) more than their neutral counterparts, leading to systematic errors in calculated redox potentials [38].