Validating DFT Calculations with Experimental Spectroscopic Data for Metal Complexes: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on integrating Density Functional Theory (DFT) with experimental spectroscopy to validate the properties of metal complexes.

Validating DFT Calculations with Experimental Spectroscopic Data for Metal Complexes: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on integrating Density Functional Theory (DFT) with experimental spectroscopy to validate the properties of metal complexes. It covers foundational principles, practical methodological protocols, troubleshooting for common pitfalls, and robust validation strategies. By synthesizing insights from recent studies on antimicrobial complexes, antioxidant mechanisms, and catalytic centers, this guide aims to enhance the reliability of computational models in predicting geometric structures, electronic properties, and reactive sites, thereby accelerating the design of metallodrugs and functional materials.

The Essential Partnership: Understanding DFT and Spectroscopy for Metal Complex Characterization

Density Functional Theory (DFT) has established itself as the computational workhorse in quantum mechanics, bridging the gap between theoretical principles and predictive materials science. Its evolution from the foundational Hohenberg-Kohn theorems to sophisticated hybrid functionals has transformed computational chemistry and materials design, particularly for complex systems like metal complexes and biological molecules [1]. This guide examines DFT's performance across various methodological approaches, focusing on its critical validation through direct comparison with experimental spectroscopic data—the cornerstone of credible computational research in drug development and materials science.

Theoretical Framework and Functional Performance

DFT Fundamentals

DFT revolutionized quantum calculations by replacing the N-electron wavefunction with the electron density as the fundamental variable, significantly reducing computational complexity while incorporating electron correlation [1]. The Kohn-Sham approach implements this theory through a system of non-interacting electrons, with accuracy primarily dependent on the approximation used for the exchange-correlation functional [1].

Functional Comparison and Performance

The choice of functional profoundly impacts calculation accuracy. Different approximations balance computational cost with performance across various chemical properties:

Table 1: Comparison of DFT Functional Types and Their Applications

| Functional Type | Examples | Key Features | Optimal Applications | Known Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GGA | BP86, PBE | Good geometries, fast computation | Structural optimization, large systems | Less accurate for energetics, spectroscopy |

| Hybrid GGA | B3LYP, B3PW91 | 20-25% HF exchange; balanced performance | General purpose for transition metals | Charge transfer states, long-range interactions |

| Meta-GGA | TPSSh | Improved energetics | Transition metal systems | Varying performance for spectroscopic properties |

| Range-Separated Hybrid | CAM-B3LYP, ωB97XD | Distance-dependent HF exchange | Charge transfer, optical properties, NLO materials | Parameter-dependent performance |

| Double Hybrid | B2PLYP | Incorporates MP2 correlation | High-accuracy energetics | Computationally expensive |

Recent systematic evaluations reveal how functional selection impacts practical accuracy. For structural parameters, most functionals perform adequately, with GGA functionals often providing excellent geometries at lower computational cost [1]. However, for electronic and spectroscopic properties, hybrid functionals with exact exchange admixture typically outperform pure GGAs [2] [3].

Experimental Validation: Case Studies in Metal Complexes Research

Spectroscopic Characterization of Schiff Base Metal Complexes

A comprehensive study of trivalent metal complexes (Cr(III), Ru(III), Fe(III), Al(III), Ti(III)) with N,N,O-Schiff base ligands demonstrates DFT's predictive power when validated experimentally [4]. Researchers synthesized and characterized complexes using FT-IR, UV-Vis spectroscopy, and elemental analysis, then compared results with DFT calculations at the B3LYP/LANL2DZ level [4].

The experimental-computational workflow yielded exceptional agreement:

- Structural predictions: Optimized geometries proposed distorted octahedral structures around metal ions, consistent with experimental data [4]

- Electronic properties: Calculated HOMO-LUMO gaps revealed distinct reactivity profiles, with ΔE values ranging from 1.64 eV (Al(III)) to 3.68 eV (Ru(III)) [4]

- Antioxidant activity: DFT-calculated reactivity parameters correlated with experimental DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging assays (Ru(III) complex: IC₅₀ = 1.69 ± 2.68 µM for DPPH) [4]

- Biological activity: Molecular docking studies against bacterial DNA gyrase enzymes (2XCT, 5BOD, 5L3J) explained observed antimicrobial efficacy through predicted binding interactions [4]

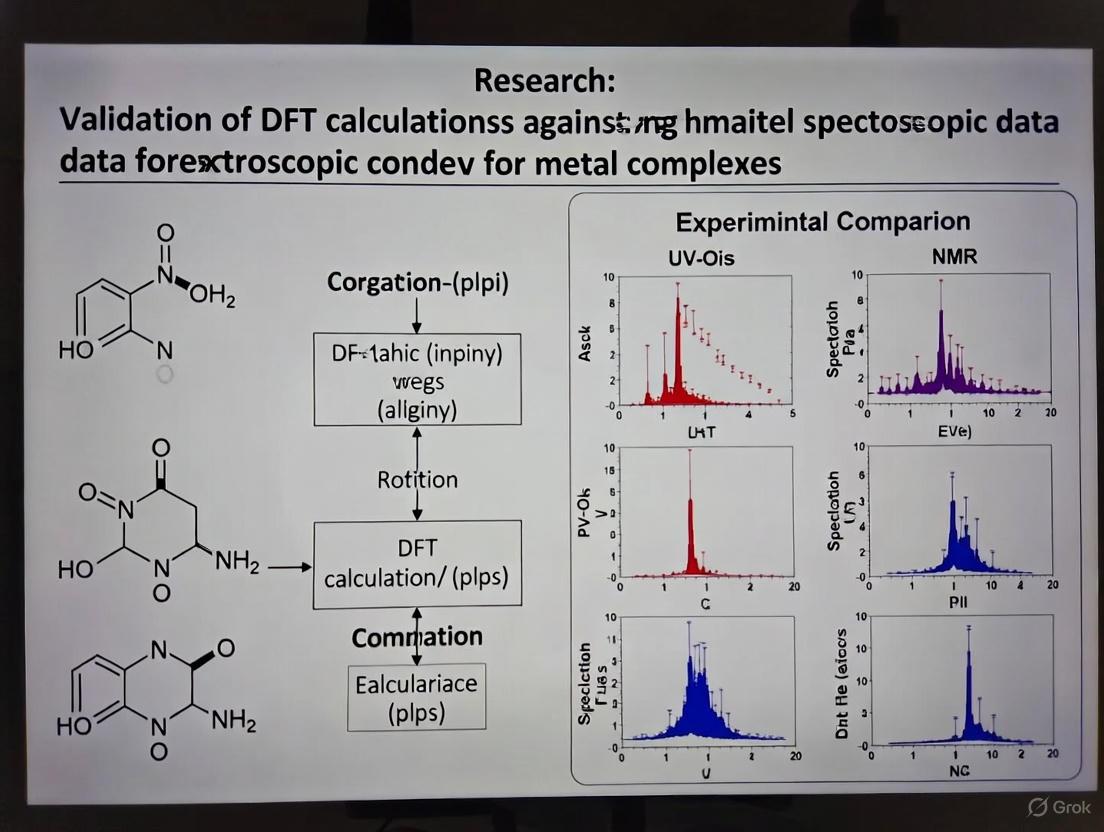

DFT-Experimental Validation Workflow: Integrating computational predictions with experimental verification for metal complexes research.

Advanced Spectroscopic Validation Protocols

Antioxidant Mechanism Elucidation

A combined experimental-theoretical approach elucidated the antioxidant mechanism of crocin, a natural carotenoid [5]. The protocol employed:

Experimental Component:

- UV-vis spectroscopy: Measured DPPH radical scavenging efficiency (32% within 60 minutes)

- NMR analysis: Detected merging of C5 and C14 proton doublets into singlets, indicating enhanced symmetry post-reaction

- Fluorescence spectroscopy: Monitored excited state interactions with DPPH radicals

Computational Component:

- DFT calculations: M062X/6-311+G(d,p) level with PCM solvation

- Electronic analysis: Minimal energy gap (0.12 eV) between crocin's LUMO and ·OH's HOMO supported electron-transfer mechanism

- Fukui function analysis: Localized nucleophilic active sites at C3 and C5

- Transition state calculations: Activation energies identified C3 as predominant reactive site (972.22 kcal/mol vs 973.00 kcal/mol for C5) [5]

This integrated approach demonstrated crocin eliminates free radicals via synergistic electron transfer and hydrogen bonding, with C3 exhibiting optimal activity [5].

Nonlinear Optical Material Development

Comprehensive DFT investigations guide the development of advanced materials with specific optical properties. For thiosemicarbazone Schiff base compounds, researchers compared B3LYP and HSEH1PBE functionals for predicting nonlinear optical (NLO) properties [3]. Experimental validation confirmed:

- HOMO-LUMO gaps: 2.57 eV (Compound 1, HSEH1PBE) and 2.45 eV (Compound 2, B3LYP)

- First-order hyperpolarizability: βtot values of 5.47×10⁻³⁰ esu (Compound 1) and 6.12×10⁻³⁰ esu (Compound 2)

- Structure-property relationships: Molecular electrostatic potential maps guided understanding of charge transfer interactions

- Pharmacological potential: Molecular docking against HMGCS2 enzyme revealed binding affinities of -6.7 kcal/mol and -7.3 kcal/mol, demonstrating dual applicability as drug candidates and NLO materials [3]

Methodological Protocols for DFT Validation

Standard Validation Workflow

Robust DFT validation requires systematic protocols integrating computational and experimental components:

Table 2: Standard Experimental-Computational Validation Protocol for Metal Complexes

| Step | Experimental Component | Computational Component | Validation Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Structure Elucidation | X-ray crystallography, EXAFS | Geometry optimization (B3LYP/6-311G(d,p)) | Bond lengths (≤2 pm), angles (≤2°) |

| 2. Electronic Properties | UV-Vis spectroscopy, cyclic voltammetry | TD-DFT, HOMO-LUMO calculations | Absorption maxima (±15 nm), band gaps (±0.1 eV) |

| 3. Vibrational Analysis | FT-IR, Raman spectroscopy | Frequency calculations, potential energy distribution | Peak positions (±10 cm⁻¹), intensity patterns |

| 4. Reactivity Assessment | Radical scavenging assays, kinetic studies | Fukui functions, molecular electrostatic potential | Reactivity trends, site-specific activity |

| 5. Biological Activity | Antimicrobial assays, enzyme inhibition | Molecular docking, binding energy calculations | Binding affinity correlations (±1 kcal/mol) |

Addressing Dispersion Interactions

Standard DFT functionals often poorly describe van der Waals interactions, crucial in biological systems and molecular crystals. Specialized corrections address this limitation:

- Empirical dispersion corrections (DFT-D): Grimme's approach adding atom-pairwise C₆/R⁶ terms [6]

- Dispersion-correcting potentials (DCP): Atom-centered potentials with Gaussian functions [7]

- Non-local functionals: vdW-DF series, VV10 [6]

For biochemical applications, the B3LYP-DCP method demonstrated remarkable accuracy, with mean absolute deviation of 0.50 kcal/mol for tripeptide isomer energies compared to CCSD(T) benchmarks [7]. These corrections enable realistic modeling of aromatic interactions, CH-π interactions, and hydrogen bonding in drug-biomolecule complexes [7].

Computational Methodology Decision Tree: Selecting appropriate DFT approaches based on system properties and target applications.

Computational Software and Analysis Tools

Successful DFT research requires specialized software tools integrated into coherent workflows:

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for DFT Research

| Tool Category | Specific Software | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Packages | Gaussian 09, Q-Chem | Perform DFT calculations | Geometry optimization, frequency analysis, TD-DFT [5] [8] |

| Visualization & Analysis | GaussView, Multiwfn | Results visualization, advanced analysis | Electron density maps, Fukui functions, NCI analysis [8] |

| Spectroscopic Prediction | VEDA | Vibrational frequency analysis | Potential energy distribution, spectral assignments [8] |

| Docking & Drug Design | AutoDock, MOE | Biomolecular docking studies | Protein-ligand interactions, binding affinity prediction [4] |

Basis Set Selection Guidelines

Basis set choice critically impacts DFT accuracy and computational efficiency:

- Main group elements: 6-311G(d,p) provides excellent balance for organic molecules and metal complexes [2]

- Transition metals: LANL2DZ with effective core potentials efficiently handles relativistic effects [4]

- Diffuse functions: aug-cc-pVDZ or 6-311++G(d,p) essential for anions and weak interactions [5]

- Solid-state systems: Plane-wave basis sets with pseudopotentials for periodic systems

Current Limitations and Future Directions

Despite its successes, DFT faces inherent limitations. Systematic errors persist in formation energy predictions, with MAE values of 0.076-0.133 eV/atom compared to experimental data [9]. Hybrid approaches combining artificial intelligence with DFT show promise, achieving MAE of 0.064 eV/atom on experimental test sets—surpassing pure DFT accuracy [9].

Future developments focus on:

- Machine learning-enhanced functionals: Improving accuracy while maintaining physical rigor [9]

- Advanced dispersion corrections: More sophisticated treatments of non-covalent interactions [6]

- High-throughput screening: Rapid materials discovery through automated computational workflows [9]

- Multiscale modeling: Bridging quantum mechanics with classical simulations for biological systems

DFT maintains its position as the computational workhorse in quantum mechanics through continuous methodological refinement and rigorous experimental validation. For metal complexes research and drug development, success depends on selecting appropriate functionals, applying necessary corrections for weak interactions, and systematically validating predictions against spectroscopic data. The integration of DFT with emerging machine learning approaches promises unprecedented accuracy, further solidifying its role as an indispensable tool in modern chemical research.

In the field of metal complexes research, the synergy between computational chemistry and experimental analysis has become indispensable for accurate molecular characterization. Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations provide powerful predictions of molecular properties, geometries, and electronic structures. However, these theoretical computations require rigorous validation against experimental data to ensure their reliability. Spectroscopic techniques serve as this critical bridge between theory and experiment, offering diverse methods for confirming computational predictions through empirical observation. Each major spectroscopic method—UV-Vis, IR, NMR, and EPR—interrogates different molecular properties and provides complementary evidence for verifying DFT-calculated parameters, from electronic transitions and vibrational modes to nuclear environments and unpaired electron systems. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these core spectroscopic techniques within the specific context of validating DFT calculations for metal complexes, with particular relevance to researchers in pharmaceutical development and materials science.

Fundamental Principles and Comparison of Techniques

Core Physical Principles

Each spectroscopic technique operates on distinct physical principles, probing different aspects of molecular structure and electronic configuration:

UV-Visible Spectroscopy measures the absorption of ultraviolet and visible light (190-900 nm), resulting from electronic transitions between molecular orbitals. These transitions typically involve the promotion of electrons from highest occupied molecular orbitals (HOMO) to lowest unoccupied molecular orbitals (LUMO) in chromophores, particularly conjugated systems and metal-ligand charge transfer complexes [10] [11].

Infrared Spectroscopy detects molecular vibrations when molecules absorb infrared radiation (typically 4000-400 cm⁻¹). The technique reveals information about functional groups and chemical bonds through their characteristic stretching and bending vibrations, with absorption occurring when the vibrational frequency matches the incident IR radiation frequency [10].

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy exploits the magnetic properties of certain atomic nuclei when placed in a strong magnetic field. NMR measures transitions between nuclear spin states induced by radiofrequency radiation (typically in the MHz range), providing detailed information about the local chemical environment, molecular structure, and dynamics [10] [11].

Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (also known as Electron Spin Resonance) detects the resonance absorption of microwave radiation by unpaired electrons in a magnetic field. Similar to NMR but focusing on electrons rather than nuclei, EPR provides information about paramagnetic centers, including free radicals, transition metal complexes, and defect sites in materials [12] [13].

Comparative Analysis of Spectroscopic Techniques

The table below provides a comprehensive comparison of the four spectroscopic techniques, highlighting their key characteristics and applications in metal complexes research:

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Core Spectroscopic Techniques

| Parameter | UV-Visible Spectroscopy | Infrared Spectroscopy | NMR Spectroscopy | EPR Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radiation Type | Ultraviolet/Visible light | Infrared light | Radio waves | Microwaves |

| Wavelength Range | 190-900 nm [11] | 700 nm - 1 mm [10] | - | - |

| Energy Transition | Electronic energy levels | Molecular vibrations | Nuclear spin states | Electron spin states |

| Primary Information | Chromophores, conjugated systems, charge transfer transitions | Functional groups, chemical bonds, molecular vibrations | Molecular structure, chemical environment, dynamics | Unpaired electrons, oxidation states, coordination environment |

| Sample Form | Liquid solutions (typically) [10] | Gases, liquids, solids [10] | Primarily liquids (solution NMR) [10] | Solids, frozen solutions, liquids |

| Key Parameters | Absorption maxima (λ_max), extinction coefficient (ε) | Wavenumber (cm⁻¹), absorption intensity | Chemical shift (ppm), coupling constants (J) | g-factor, hyperfine coupling constants |

| Detection Limit | ~10⁻⁶ M (for strong chromophores) | ~1% component identification | ~10⁻³ M (for ¹H NMR) | ~10⁻⁸ M for stable radicals |

| Quantitative Application | Concentration determination (Beer-Lambert Law) | Functional group quantification | Structure quantification, kinetics | Paramagnetic center concentration |

| Typical Experiment Time | Seconds to minutes | Minutes | Minutes to hours | Minutes to hours |

| Key Applications in Metal Complexes | d-d transitions, LMCT/MLCT bands, solvatochromism | Metal-ligand bonding, coordination geometry | Ligand conformation, dynamics, purity | Oxidation state, radical characterization |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Sample Preparation Requirements

Proper sample preparation is critical for obtaining high-quality spectroscopic data that can reliably validate DFT calculations:

UV-Visible Spectroscopy: Samples are typically prepared as solutions in spectroscopically suitable solvents placed in quartz or glass cuvettes with standard path lengths of 1 cm. The solvent must not absorb significantly in the spectral region of interest, and appropriate reference measurements with pure solvent are essential for baseline correction [11].

Infrared Spectroscopy: Various sampling techniques include transmission methods for KBr pellets of solid samples, attenuated total reflectance (ATR) requiring minimal sample preparation, and solution cells for liquid samples. The technique is particularly versatile for different sample states—gases, liquids, and solids [10].

NMR Spectroscopy: Samples are dissolved in deuterated solvents (CDCl₃, DMSO-d₆, etc.) to provide a lock signal and minimize interfering proton signals. NMR tubes with standard 5 mm outer diameter are used, often with an internal standard such as tetramethylsilane (TMS) for chemical shift referencing [11].

EPR Spectroscopy: Samples can be analyzed as solids, frozen solutions, or liquids. For quantitative studies, sample concentration must be optimized to avoid dipolar broadening, and careful sample positioning in the resonant cavity is essential for reproducible results [12] [13].

Data Collection Protocols

Standardized data collection protocols ensure reproducibility and reliability when comparing experimental results with DFT predictions:

UV-Visible Protocol for Metal Complexes:

- Prepare sample solution at appropriate concentration (typically 10⁻⁵-10⁻³ M)

- Record baseline with matched solvent in reference cuvette

- Scan from 800 nm to 190 nm (or instrument limit) with 1 nm resolution

- Use slow scan speed for better signal-to-noise ratio

- Repeat measurements at different concentrations to confirm Beer-Lambert behavior

IR Protocol for Coordination Compounds:

- Select appropriate sampling technique (ATR, transmission, or reflection)

- Acquire background spectrum without sample

- Collect sample spectrum with sufficient scans (typically 16-64) for acceptable S/N

- Use 4 cm⁻¹ resolution for most applications

- Examine key regions: metal-ligand vibrations (<600 cm⁻¹), fingerprint region (600-1500 cm⁻¹), and functional group region (>1500 cm⁻¹)

NMR Protocol for Structural Validation:

- Dissolve 2-10 mg sample in 0.6 mL deuterated solvent

- Insert internal standard if not present in solvent

- Lock, tune, and shim the spectrometer

- Collect ¹H NMR spectrum with sufficient digital resolution

- For metal complexes, acquire multinuclear NMR (³¹P, ¹⁹F, ¹³C) as needed

EPR Protocol for Paramagnetic Centers:

- Prepare sample with appropriate paramagnetic center concentration (~mM)

- Select microwave power to avoid saturation (typically 0.1-20 mW)

- Sweep magnetic field across resonance condition with appropriate modulation amplitude

- Record spectrum at optimal temperature (often 77K for improved resolution)

- Measure g-factor using reference standard such as DPPH (g = 2.0036) [13]

Validation of DFT Calculations with Experimental Data

Correlation Strategies and Metrics

Successful validation of DFT calculations requires systematic correlation between computed and experimental spectroscopic parameters:

UV-Vis Validation: Compare calculated electronic transition energies and oscillator strengths with experimental absorption maxima and intensities. Time-Dependent DFT (TD-DFT) calculations directly predict electronic spectra, allowing direct comparison with experimental λ_max values and band shapes. For metal complexes, specific transitions (d-d, LMCT, MLCT) provide critical validation of DFT-predicted orbital energies and compositions [4].

IR Validation: Match computed harmonic vibrational frequencies with experimental IR absorption bands. Scale factors (typically 0.96-0.98) are often applied to calculated frequencies to account for anharmonicity and computational limitations. Both frequency positions and relative intensities provide validation metrics, with metal-ligand vibrations being particularly diagnostic for coordination geometry [4].

NMR Validation: Compare calculated chemical shifts with experimental NMR spectra. DFT methods with specific functionals (e.g., WP04, B3LYP) and basis sets can predict ¹H and ¹³C chemical shifts with accuracy sufficient for structural assignment. Chemical shift deviations <0.2 ppm for ¹H and <5 ppm for ¹³C generally indicate good agreement between calculated and experimental structures.

EPR Validation: Match computed spin Hamiltonian parameters (g-tensors, A-tensors) with experimental EPR spectra. DFT calculations can predict g-values and hyperfine coupling constants for paramagnetic systems, providing direct validation of electronic structure descriptions for open-shell systems [12].

Case Study: Schiff Base Metal Complexes

A recent study on N,N,O-Schiff base trivalent metal complexes demonstrates the integrated validation approach [4]:

Table 2: Experimental and Computational Data for Schiff Base Metal Complexes

| Compound | Experimental UV-Vis λ_max (nm) | Calculated λ_max (TD-DFT) | Experimental IR ν(C=N) (cm⁻¹) | Calculated ν(C=N) | ΔE (eV) Experimental | ΔE (eV) Calculated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HL (Ligand) | 325, 275 | 328, 281 | 1625 | 1631 | 4.60 | 4.52 |

| Cr(III) Complex | 420, 320 | 415, 318 | 1605 | 1612 | 2.59 | 2.48 |

| Ru(III) Complex | 480, 350 | 485, 345 | 1598 | 1605 | 3.68 | 3.59 |

| Fe(III) Complex | 455, 325 | 450, 322 | 1602 | 1608 | 3.15 | 3.06 |

| Ti(III) Complex | 435, 310 | 430, 308 | 1595 | 1601 | 2.75 | 2.68 |

This case study demonstrates excellent correlation between experimental spectroscopic data and DFT calculations, validating both the methodology and the proposed structures. The bathochromic shifts in both experimental and calculated UV-Vis spectra confirm metal coordination, while the calculated HOMO-LUMO gaps (ΔE) closely match experimental values derived from UV-Vis edge absorption.

Workflow Integration and Data Interpretation

Integrated Validation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the systematic workflow for validating DFT calculations using multiple spectroscopic techniques:

Spectroscopic Validation Workflow for DFT Calculations

Troubleshooting Common Discrepancies

When discrepancies occur between calculated and experimental spectroscopic data, systematic troubleshooting is essential:

Systematic UV-Vis Deviations: Consistent overestimation or underestimation of transition energies often indicates inappropriate functional selection. Hybrid functionals (e.g., B3LYP, PBE0) typically perform better for charge transfer transitions, while range-separated functionals (e.g., CAM-B3LYP) improve accuracy for Rydberg transitions [4].

IR Frequency Scaling: Consistent offsets between calculated and experimental vibrational frequencies require application of scaling factors. Different scaling factors are needed for specific functional/basis set combinations and for different frequency regions (e.g., high-frequency X-H stretches vs. low-frequency metal-ligand vibrations).

NMR Solvent Effects: Differences between calculated (gas-phase) and experimental (solution) chemical shifts may result from solvent effects. Implicit solvation models (PCM, SMD) in calculations can significantly improve agreement for polar molecules and ions.

EPR Parameter Accuracy: Discrepancies in g-values and hyperfine couplings may indicate inadequate treatment of spin-orbit coupling or insufficient basis set flexibility near the metal center. Relativistic methods or specialized basis sets may be necessary for heavy metal complexes.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Spectroscopic Studies of Metal Complexes

| Reagent/Material | Specification Requirements | Primary Application | Handling Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Solvents (CDCl₃, DMSO-d₆) | 99.8% D minimum, with or without TMS | NMR spectroscopy for signal locking and referencing | Store under inert atmosphere; protect from moisture |

| DPPH Standard (Diphenyl-Picryl-Hydrazyl) | High-purity crystalline solid | EPR g-factor calibration and sensitivity testing | Protect from light; prepare fresh solutions |

| IR Sampling Accessories (ATR crystals, KBr) | Spectroscopic grade, anhydrous | Sample preparation for IR measurements | Store desiccated; clean crystals with appropriate solvents |

| UV-Vis Cuvettes | Quartz (UV range), glass (Vis range) | Sample containment for UV-Vis measurements | Meticulous cleaning; proper optical alignment |

| NMR Reference Standards (TMS, DSS) | High-purity, volatile or non-volatile | Chemical shift referencing in NMR | Use at appropriate concentrations; compatibility check |

| EPR Sample Tubes | High-purity quartz, specific diameters | Sample containment for EPR measurements | Correct positioning in cavity; avoid air bubbles |

| Inert Atmosphere Equipment (Glove boxes, septa) | Oxygen <1 ppm, moisture <1 ppm | Air-sensitive sample preparation | Regular atmosphere monitoring; proper sealing |

The integration of multiple spectroscopic techniques provides a powerful validation framework for DFT calculations in metal complexes research. Each method offers complementary information that collectively constrains the possible structural interpretations and confirms computational predictions. UV-Visible spectroscopy validates electronic structure, IR spectroscopy confirms bonding and functional groups, NMR provides detailed structural information for diamagnetic systems, and EPR characterizes paramagnetic centers. The continuing advancement in both spectroscopic instrumentation and computational methods promises even tighter integration between theory and experiment, enabling more reliable characterization of complex metal-containing systems with applications across pharmaceutical development, materials science, and catalysis research.

Density Functional Theory (DFT) has become an indispensable computational tool for researchers investigating metal complexes, particularly in pharmaceutical and materials science applications. The reliability of these calculations, however, hinges on rigorous validation against experimental data. This guide provides a structured comparison of validation methodologies focused on three fundamental properties: molecular geometry, electronic structure, and vibrational frequencies. By examining the performance of different computational approaches against experimental benchmarks, researchers can make informed decisions when studying metal-containing systems for drug development and other advanced applications.

Computational Methodologies and Basis Sets in DFT

The accuracy of DFT calculations depends significantly on the selected exchange-correlation functionals and basis sets. Different approaches offer distinct advantages for specific properties and systems.

Table 1: Common DFT Functionals and Basis Sets for Metal Complexes

| Computational Method | System Type | Strengths | Validation Performance | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) | Organic molecules, main group elements | Excellent for molecular geometry optimization | Superior for triclosan bond lengths (MAD: 0.0353 Å) | [14] |

| B3LYP/GENECP | Transition metal complexes | Mixed basis sets (e.g., 6-311G(d,p) for ligands, LANL2DZ for metals) | Accurate geometry and electronic structure for Cu(II)-PQMHC complex | [15] |

| M06-2X/6-311++G(d,p) | Systems with non-covalent interactions | High parameterization for dispersion forces | Best overall for structural prediction of triclosan | [14] |

| HSE06 | Solid-state materials, band gaps | Corrects GGA band gap underestimation | 50% improvement in band gap MAE (0.62 eV vs. 1.35 eV for PBE) | [16] |

| CAM-B3LYP | Excited states, electronic spectra | Long-range correction for charge transfer | Accurate electronic absorption spectra via TD-DFT | [15] |

| LSDA/6-311G | Vibrational frequency calculations | Computational efficiency | Best performance for predicting triclosan vibrational spectra | [14] |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Validating computational predictions requires robust experimental techniques that provide complementary structural and electronic information.

Structural Characterization Techniques

X-ray Diffraction (XRD): Single-crystal XRD provides the most definitive geometrical parameters, including bond lengths, bond angles, and coordination geometry. When single crystals are unavailable, powder XRD offers alternative structural insights, as demonstrated in the characterization of novel Schiff base metal complexes [17]. The experimental protocol involves mounting a crystal on a diffractometer, collecting reflection data, and solving the structure through direct methods and refinement.

Spectroscopic Methods: Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, particularly ¹H and ¹³C, provides information about the chemical environment and connectivity in organic ligands and their metal complexes. The Gauge Independent Atomic Orbital (GIAO) method enables computational prediction of NMR chemical shifts for direct comparison with experimental data [18].

Electronic Structure Characterization

Electronic Absorption Spectroscopy: UV-Vis spectroscopy measures electronic transitions between energy states. For metal complexes, this includes d-d transitions, charge transfer bands, and ligand-centered transitions. Time-Dependent DFT (TD-DFT) calculations simulate these excitations, with functionals like CAM-B3LYP providing enhanced accuracy for excited states [15].

Band Structure Analysis: For solid-state materials, experimental band gaps can be determined through optical absorption spectroscopy or photoelectron spectroscopy. These measurements benchmark the accuracy of DFT-predected electronic band structures and density of states, where hybrid functionals like HSE06 significantly outperform GGA functionals [16].

Vibrational Analysis

Fourier-Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy: Experimental IR spectra are recorded across the 400-4000 cm⁻¹ range, identifying characteristic functional group vibrations. For the calix[4]arene derivative, solid-phase FT-IR spectra provided the experimental benchmark for validating DFT-calculated harmonic vibrational frequencies and infrared intensities [18]. Wavenumber-linear scaling (WLS) methods correct for systematic overestimation of computed frequencies due to anharmonicity effects and basis set limitations [14].

Vibrational Circular Dichroism (VCD): VCD measures the differential absorption of left and right circularly polarized IR radiation by chiral molecules. This technique provides stereochemical information beyond conventional IR, though its intensity can be enhanced by low-lying electronic states in metal complexes, presenting both challenges and opportunities for theoretical simulation [19].

Quantitative Comparison of Computational vs. Experimental Data

Systematic validation requires quantitative metrics to assess computational accuracy across different molecular properties.

Table 2: Performance Metrics for DFT Validation

| Validation Property | Computational Method | Mean Absolute Deviation | System Studied | Key Finding | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Lengths | M06-2X/6-311++G(d,p) | 0.0353 Å | Triclosan | Superior to B3LYP, LSDA, PBEPBE, CAM-B3LYP | [14] |

| Formation Energies | HSE06 vs. PBEsol | 0.15 eV/atom | 7,024 inorganic materials | HSE06 provides lower formation energies | [16] |

| Band Gaps | HSE06 vs. PBEsol | MAD: 0.77 eV | 7,024 inorganic materials | HSE06 corrects GGA underestimation | [16] |

| Band Gaps (Exp.) | HSE06 vs. Experiment | MAE: 0.62 eV | 121 binary materials | >50% improvement over PBEsol (MAE: 1.35 eV) | [16] |

| Vibrational Frequencies | LSDA/6-311G | Best performance after scaling | Triclosan | Optimal for vibrational spectra prediction | [14] |

Research Reagent Solutions for Experimental Validation

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Metal Complex Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Specification | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| o-Vanillin | Precursor for tridentate Schiff base ligands | Sigma-Aldrich, 99% purity | [17] |

| 2-amino-4-chlorophenol | Amine component for Schiff base synthesis | TCI Chemicals | [17] |

| Transition Metal Salts | Metal center source for complexation | Cu(II), Co(II), Ni(II) chlorides (Merck, 97-98%) | [17] |

| Deuterated Solvents | NMR spectroscopy | CDCl₃ for conformational studies | [19] |

| Crystallization Solvents | Single crystal growth | Ethanol, diethyl ether, DMF (99% purity) | [15] |

| Silica Gel | Chromatographic purification | 60-120 mesh for column chromatography | [17] |

Workflow for DFT Validation in Metal Complex Research

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational and experimental workflow for validating DFT studies of metal complexes:

Advanced Applications and Special Considerations

Challenges in Chiral and Open-Shell Systems

Transition metal complexes with chiral ligands or open-shell electronic configurations present unique validation challenges. For Co(II)-salen-chxn complexes, VCD enhancement through low-lying electronic states creates intense monosignate bands that current DFT simulations struggle to reproduce accurately [19]. Similarly, spin state considerations are crucial, as different spin multiplicities (high-spin vs. low-spin) can lead to significantly different geometric and electronic structures that require careful computational treatment [19].

High-Throughput Database Validation

Large-scale materials databases built from hybrid functional DFT calculations, such as the 7,024-material database constructed using HSE06, provide valuable benchmarks for method validation [16]. These resources enable systematic assessment of computational accuracy across diverse chemical spaces and reveal functional-dependent trends in predicting properties like thermodynamic stability and electronic band gaps.

Validating DFT calculations for metal complexes requires a multifaceted approach comparing computational results with experimental data across geometric, electronic, and vibrational properties. The selection of appropriate functionals and basis sets remains system-dependent, with B3LYP/GENECP excelling for transition metal complexes, HSE06 providing superior electronic properties, and M06-2X/6-311++G(d,p) offering excellent structural predictions. As computational methods advance, integrating high-throughput databases and addressing challenges in chiral and open-shell systems will further enhance validation protocols, providing drug development researchers with increasingly reliable tools for metal complex characterization.

The Critical Role of Metal Complexes in Biomedicine and Catalysis

Metal complexes, characterized by a central metal ion bonded to organic or inorganic ligands, have evolved from fundamental chemical curiosities to indispensable tools in modern science and technology. Their unique electronic properties, diverse coordination geometries, and versatile reactivity profiles enable applications that are often unattainable with purely organic compounds [20]. In biomedicine, this translates to the development of novel therapeutic and diagnostic agents capable of interacting with biological systems through unique mechanisms of action. In catalysis, metal complexes drive chemical transformations with exceptional efficiency and selectivity, even within complex biological environments like living cells [21] [22]. The performance and potential of these complexes can be profoundly understood and predicted through a combination of experimental spectroscopic characterization and computational modeling, primarily using Density Functional Theory (DFT). This guide provides a comparative overview of the applications of metal complexes, detailing experimental data and methodologies central to research in this field.

Biomedical Applications of Metal Complexes

Metal complexes offer distinct advantages in biomedicine due to their ability to adopt specific three-dimensional geometries, undergo redox reactions, and engage in ligand exchange processes [20] [23]. These properties are harnessed for therapeutic effects against a range of diseases, from cancer to infectious diseases.

Anticancer Agents

Platinum-based drugs like cisplatin, carboplatin, and oxaliplatin are cornerstone treatments in oncology, demonstrating the profound impact of metal complexes in medicine [20] [23]. Their success has spurred the investigation of other metals, with recent studies highlighting the efficacy of non-platinum complexes, sometimes even against cisplatin-resistant cancer cells [23]. For instance, ruthenium-based complexes have been shown to effectively activate prodrugs inside cancer cells. A notable example is the Ru(IV) allyl complex (4, Fig. 2B) that catalyzes the uncaging of an N-Alloc protected doxorubicin prodrug (5) within HeLa cells, leading to a dramatic decrease in cell viability (to 2-7%), whereas the prodrug or catalyst alone showed no effect [21].

Table 1: Comparative Anticancer Activity of Selected Metal Complexes

| Complex | Metal | Target/Cell Line | Reported Activity | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cisplatin [23] | Pt(II) | Various Cancers | Clinical Efficacy | Standard of care; associated with side effects and resistance |

| Complex 4 [21] | Ru(IV) | HeLa mammalian cells | Catalytic prodrug activation | 20 μM catalyst with 100 μM prodrug reduced cell viability to 2% |

| Λ-OS1 [20] | Ru(II) | Glycogen synthase kinase 3α (GSK3α) | IC~50~ = 0.9 nM | 15- to >111,000-fold selectivity over 5 other protein kinases |

| Pd/Pt with mpo/dppf [24] | Pd(II), Pt(II) | Trypanosoma cruzi (parasite) | IC~50~ = 0.28 - 0.64 μM | 10-20x more active than reference drug Nifurtimox |

Antimicrobial and Antiparasitic Agents

The rise of drug-resistant pathogens has renewed interest in metal complexes as antimicrobial and antiparasitic agents. The inherent ability of metals to engage in multiple modes of action can help overcome existing resistance mechanisms [24]. Silver complexes, for example, have long been known for their broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity and are used in treating burns and wounds [25] [20].

Table 2: Comparative Antimicrobial and Antiparasitic Activity of Metal Complexes

| Complex | Metal | Target Pathogen | Reported Activity (IC~50~) | Selectivity Index (SI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [RuCp(PPh~3~)~2~(CTZ)]^+^ (1) [24] | Ru(II) | Trypanosoma cruzi | 0.25 μM | >7.6 (vs. mammalian cells) |

| Trypanosoma brucei | 0.6 μM | 3.2 (vs. mammalian cells) | ||

| Na mpo (Ligand for 2 & 3) [24] | - | Trypanosoma cruzi | 1.33 - 2.42 μM | Not Specified |

| [M(mpo)(dppf)]^+^ (M=Pd 2, Pt 3) [24] | Pd(II), Pt(II) | Trypanosoma cruzi | 0.28 - 0.64 μM | ~10-20 (vs. reference drug) |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 1.6 - 2.8 μM | Not Specified | ||

| 5MeOBM Ag(I) Complex [25] | Ag(I) | Various Bacteria/Fungi | (In vitro activity confirmed) | More effective than free ligand |

Catalytic Applications in Chemistry and Biology

Beyond their direct therapeutic action, metal complexes serve as powerful catalysts, enabling chemical reactions that are essential in synthetic chemistry and, more recently, within biological systems.

Intracellular Catalysis

The deployment of metal complexes as catalysts inside living cells represents a frontier in chemical biology. These catalysts can perform bio-orthogonal reactions, activating prodrugs or revealing fluorescent probes with spatial and temporal control [21]. Ruthenium complexes have been pioneers in this field. For example, the complex [Cp*Ru(cod)Cl] (1) was shown to catalyze the uncaging of an Alloc-protected rhodamine profluorophore (2) inside HeLa cells, leading to a 10-fold increase in fluorescence, a significant boost over the 3.5-fold increase observed in control experiments without the catalyst [21]. A key requirement for these reactions in a cellular environment is compatibility with aqueous media and the presence of biological nucleophiles like thiols, which can be essential for catalytic activity [21].

Synthetic Catalysis

Macromolecular Metal Complexes (MMCs) demonstrate high efficacy and reusability as catalysts in a wide array of chemical reactions. Their structural arrangement enhances stability and selectivity [22]. MMCs have been successfully employed as catalysts for:

- Polymerization and oligomerization of ethylene and vinyl monomers.

- Cross-coupling reactions (e.g., Heck and Suzuki reactions).

- Oxidation reactions (e.g., of cyclohexene, catechol, and ethylbenzene).

- Epoxidation of alkenes and styrene.

- Hydroxylation of alkanes and aryl-alkane [22].

Experimental and Computational Characterization

A critical aspect of modern research on metal complexes is the synergistic use of experimental characterization and computational modeling to understand their structure, properties, and reactivity.

Spectroscopic and Analytical Methods

A multi-technique approach is essential for fully characterizing metal complexes. The primary methods include:

- Elemental Analysis: Determines the chemical formula purity [25].

- NMR Spectroscopy: Probes the chemical environment of atoms, particularly hydrogen and carbon, in the ligand and complex [25].

- FT-IR Spectroscopy: Identifies functional groups and can confirm metal-ligand coordination by observing shifts in vibrational frequencies [25].

- UV-Vis Spectroscopy: Investigates electronic properties and optical characteristics [25].

- Mass Spectrometry: Confirms molecular mass and fragmentation patterns [25].

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD): The gold standard for determining solid-state molecular structure [22].

- Thermal Analysis (TGA/DTA): Assesses thermal stability and decomposition patterns [22].

- Cyclic Voltammetry: Elucidates redox properties [22].

Density Functional Theory (DFT) Calculations

DFT is a cornerstone computational method for modeling the structures and properties of metal complexes. It is used to:

- Optimize Molecular Geometry: Calculating the most stable structure and confirming it against experimental data (e.g., from XRD) [25].

- Predict Vibrational Frequencies: Simulating IR spectra and assigning vibrational modes [25].

- Analyze Electronic Structure: Calculating Frontier Molecular Orbitals (HOMO/LUMO) to determine chemical reactivity, hardness, and other quantum chemical parameters [25].

- Perform Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) Analysis: Understanding intramolecular interactions, hybridization, and bond nature [25].

- Model Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP): Visualizing charge distribution and identifying potential reactive sites [25].

- Predict NMR Chemical Shifts: Using methods like GIAO (Gauge-Independent Atomic Orbital) to compare with experimental NMR data [25].

A Case Study in Validation: 5-Methoxy-1H-benzo[d]imidazole Ag(I) Complex

A 2024 study provides a clear protocol for the synergistic use of experiment and DFT [25].

- Synthesis: The Ag(I) complex was prepared in a 2:1 (ligand:metal) molar ratio by reacting 5-methoxy-1H-benzo[d]imidazole (5MeOBM) with AgNO~3~ in ethanol at 50°C [25].

- Characterization:

- FT-IR: Experimental spectra showed a shift in the C=N stretching vibration of the imidazole ring upon complexation, indicating coordination through the nitrogen atom. This shift was paralleled in DFT-calculated vibrational frequencies [25].

- NMR: Experimental ^1^H NMR data correlated well with chemical shifts calculated using the GIAO method, confirming the molecular structure [25].

- UV-Vis and HOMO-LUMO: Experimental UV-Vis spectra were used in conjunction with DFT-calculated HOMO-LUMO energy levels to determine the energy gap (ΔE=4.475 eV for the complex), which is related to the complex's chemical stability and reactivity [25].

- Bioactivity Validation: The enhanced antimicrobial activity of the Ag(I) complex compared to the free ligand was confirmed through in vitro antimicrobial assays, demonstrating the functional payoff of the characterized structure [25].

DFT-Experimental Validation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Metal Complex Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Silver Nitrate (AgNO₃) [25] | Source of Ag(I) ions for complex synthesis | Synthesis of antimicrobial Ag(I)-benzimidazole complexes [25]. |

| Ruthenium Precursors (e.g., [Cp*Ru(cod)Cl]) [21] | Catalyst/precursor for bio-orthogonal catalysis | Intracellular uncaging of pro-fluorophores and prodrugs in living cells [21]. |

| Schiff Base Ligands [22] [23] | Versatile chelating ligands for diverse metal ions | Forming stable complexes with antimicrobial and catalytic properties. |

| Ferrocene Derivatives (e.g., dppf) [24] | Lipophilic, redox-active ligand to enhance cell membrane penetration | Incorporated into Pd(II)/Pt(II) complexes to boost activity against T. cruzi [24]. |

| 5-Methoxy-1H-benzo[d]imidazole [25] | A biologically active heterocyclic ligand | Studying enhanced bioactivity upon complexation with Ag(I) [25]. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) Codes (e.g., B3LYP) [25] [26] | Computational modeling of structure, energy, and properties | Predicting geometry, IR spectra, and HOMO-LUMO gaps for comparison with experiment [25]. |

Metal complexes continue to prove their critical value across biomedicine and catalysis. Their unique structural and electronic features enable the design of potent anticancer and antimicrobial agents, as well as sophisticated catalysts that can operate even within living systems. The fidelity of DFT calculations in predicting experimental outcomes has made the partnership between computation and experiment a fundamental paradigm in the field. Future progress will likely involve designing more sophisticated complexes that overcome challenges of toxicity and resistance, expanding the repertoire of metals used, and further refining computational models to accelerate the rational design of the next generation of metal-based tools and medicines.

In the field of metal complexes research, two seemingly distinct approaches—experimental spectroscopy and computational density functional theory (DFT)—have evolved from parallel paths into powerfully complementary tools. Experimental methods provide tangible data from the physical world, while computational modeling offers atomic-level insights and predictive power. When strategically combined, they form a validation cycle that accelerates discovery, particularly in developing new catalytic materials and pharmaceutical agents. This guide objectively compares the performance of these integrated approaches, demonstrating how researchers can leverage their combined strengths to obtain more reliable and insightful data than either method could provide alone.

The synergy is particularly evident in studying metal complexes of Schiff bases and similar ligands, which are crucial in biological systems and industrial applications. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding how to effectively bridge these methodologies is becoming essential practice. This article provides a detailed comparison of their capabilities, supported by experimental data and clear protocols for implementation.

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Data Generation

Synthesis of Metal Complexes

The foundational step involves synthesizing ligands and their corresponding metal complexes with precise characterization. The following protocol, adapted from recent studies, ensures reproducible results:

Ligand Synthesis: The Schiff base ligand H₂L is typically prepared by condensing salicylaldehyde with o-phenylenediamine in absolute ethanol under reflux conditions for 2-4 hours [27]. The product is purified through recrystallization from ethanol and characterized for purity before complexation.

Metal Complex Formation: For a Cu(II) complex with a pyranoquinoline-based semicarbazone ligand (PQMHC), an aqueous solution of LiOH·H₂O is added dropwise to a hot solution of the H₂L ligand. CuSO₄·5H₂O in ethanol is gradually added under continuous stirring at a 1:1 molar ratio. The reaction mixture is refluxed for 6 hours, during which a colored solid forms. The product is filtered, washed with ethanol and diethyl ether, and air-dried [15].

Purification and Storage: Complexes are purified using recrystallization from appropriate solvents like DMF/ethanol mixtures and stored in desiccators to prevent hydration or decomposition [28].

Spectroscopic Characterization Techniques

Experimental characterization employs multiple spectroscopic techniques to obtain comprehensive structural information:

FT-IR Spectroscopy: Samples are prepared as KBr pellets and analyzed across the 4000-400 cm⁻¹ range. Specific attention is paid to shifts in key vibrational frequencies, particularly the azomethine (C=N) stretch, which typically appears around 1658 cm⁻¹ in free ligands and shifts to lower frequencies (1597-1620 cm⁻¹) upon metal coordination [28].

Electronic Spectroscopy: UV-Vis spectra are recorded in DMSO or methanol solutions within the 200-800 nm range. Charge transfer bands and d-d transitions provide information about coordination geometry and electronic properties [4].

NMR Spectroscopy: For diamagnetic complexes, ¹H and ¹³C NMR spectra are recorded in DMSO-d⁶. The disappearance of the phenolic OH proton signal (typically around 13.12 ppm) and shifts in the azomethine proton signal provide evidence of metal coordination [28].

Single-Crystal X-ray Diffraction: Suitable crystals are selected and mounted on a Bruker APEX-II CCD diffractometer using MoKα radiation (λ = 0.71073) at 273.15 K. Structures are solved using Olex2 software with Charge Flipping for initial structure solution and refined with the NoSpherA2 method for enhanced accuracy of hydrogen atom positions [29].

Computational Methods

DFT calculations provide the theoretical framework for interpreting experimental results:

Geometry Optimization: Initial structures from crystallographic data are optimized using Gaussian 09 software with the B3LYP functional. For main group elements, the 6-311G(d,p) basis set is employed, while transition metals are handled with LANL2DZ effective core potentials [15] [27].

Electronic Property Calculations: Time-Dependent DFT (TD-DFT) calculations are performed at the CAM-B3LYP level to simulate electronic absorption spectra, accounting for solvation effects using the CPCM model [15] [29].

Wavefunction Analysis: Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) analysis and molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) maps are generated to understand charge distribution and reactive sites [15] [27].

Band Gap and Reactivity Descriptor Calculations: HOMO-LUMO energies are calculated to determine energy gaps (ΔE), which are correlated with stability and reactivity. Global reactivity descriptors (electronegativity, hardness, softness) are derived from frontier molecular orbital energies [4] [27].

Table 1: Key Characterization Techniques and Their Information Output

| Technique | Experimental Data Obtained | Structural Information Revealed |

|---|---|---|

| FT-IR | Vibrational frequencies | Coordination sites, binding mode |

| UV-Vis | Electronic transitions | Coordination geometry, band gaps |

| NMR | Chemical shifts, integration | Coordination environment, diamagnetic complexes |

| X-ray Diffraction | Atomic coordinates, bond lengths/angles | Precise molecular geometry, crystal packing |

| Elemental Analysis | Percentage of C, H, N elements | Complex stoichiometry, purity |

| Molar Conductance | Conductivity measurements | Electrolyte nature, counter ion position |

Comparative Performance Analysis: Experimental vs. Computational Approaches

Structural Determination Accuracy

The complementary nature of experimental and computational methods is particularly evident in structural determination, where each approach compensates for the limitations of the other.

X-ray crystallography provides the most authoritative experimental structural data, with the NoSpherA2 refinement method offering enhanced accuracy for hydrogen atom positioning [29]. However, this technique requires high-quality single crystals, which can be challenging to obtain for all complexes. Computational optimization using DFT methods like B3LYP/LANL2DZ provides reliable structural models that closely match experimental results, with typical metal-ligand bond length deviations of only 0.01-0.02 Å and bond angle deviations of 1-2 degrees [27].

For the SalophH₂ ligand system, experimental data confirms a planar geometry, while metal complexes display varied coordination geometries: Sr²⁺ and Mg²⁺ complexes adopt distorted octahedral geometries, Li⁺ and Ca²⁺ show trigonal bipyramidal coordination, and the Ni²⁺ complex displays square planar geometry—all successfully predicted by DFT calculations [27].

Electronic Properties and Spectral Matching

Electronic properties represent an area where the synergy between experimental and computational approaches is particularly powerful, with each method validating and explaining observations from the other.

Table 2: Experimental vs. Computational Electronic Property Analysis

| Compound | Experimental Band Gap (eV) | Computational Band Gap (eV) | Method/Basis Set | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PQMHC Ligand | 4.60 (UV-Vis) | 4.55 (DFT) | B3LYP/6-311G(d,p) | Semiconductor devices [15] |

| Cu(II)-PQMHC Complex | 2.75 (UV-Vis) | 2.70 (DFT) | B3LYP/GENECP | Optical materials [15] |

| Schiff Base (HL) | 4.60 (UV-Vis) | 4.52 (DFT) | B3LYP/LANL2DZ | Antioxidant applications [4] |

| Cr(III) Complex (C1) | 2.59 (UV-Vis) | 2.55 (DFT) | B3LYP/LANL2DZ | Antimicrobial agents [4] |

| Ti(III) Complex (C5) | 2.75 (UV-Vis) | 2.71 (DFT) | B3LYP/LANL2DZ | Photocatalytic applications [4] |

TD-DFT calculations using the CAM-B3LYP functional have demonstrated remarkable accuracy in reproducing experimental UV-Vis spectra. For N-phenyl-o-benzenedisulfonimide, TD-DFT correctly predicted the predominant π→π* transitions between benzene rings observed experimentally in both DMSO and chloroform solvents [29]. The combination of experimental and computational approaches provides a complete picture of electronic structures, with experimental data validating computational models, and computational methods explaining the electronic origins of observed spectral features.

Biological Activity Prediction

The combination of experimental and computational methods significantly enhances the prediction and understanding of biological activity in metal complexes.

Experimental assays provide direct evidence of biological efficacy. For instance, trivalent metal complexes of N,N,O-Schiff bases demonstrated excellent dose-dependent free radical scavenging activity, with Ru(III) and Ti(III) complexes showing IC₅₀ values of 1.69 ± 2.68 µM and 8.70 ± 2.78 µM for DPPH and ABTS radicals, respectively [4]. These complexes also exhibited higher antimicrobial activities compared to the free ligand against designated bacterial strains.

Computational methods complement these findings by providing mechanistic insights. DFT calculations reveal that complexes with smaller HOMO-LUMO gaps (like the Mg²⁺ complex at 1.64 eV) generally exhibit enhanced charge transfer properties, which often correlate with biological activity [27]. Molecular docking studies further explain structure-activity relationships by showing how complexes interact with biological targets like DNA gyrase enzymes through classical O—H⋯O and N—H⋯O hydrogen bonds, as well as hydrophobic contacts [4].

Essential Research Tools and Reagents

Successful integration of experimental and computational approaches requires specific reagents and computational resources. The following table details essential materials and their functions in metal complex research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Metal Complex Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Salicylaldehyde Derivatives | Ligand precursor for Schiff base formation | 5-chloro-salicylaldehyde for enhanced biological activity [28] |

| o-Phenylenediamine | Diamine component for tetradentate SalophH₂ ligand | Forms N₂O₂ donor set for metal coordination [27] |

| Metal Salts | Metal ion sources for complexation | CuSO₄·5H₂O, Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, La(NO₃)₃·6H₂O [15] [28] |

| DFT Software Packages | Quantum chemical calculations | Gaussian 09, VASP for geometry optimization and property prediction [27] [30] |

| Spectroscopic Solvents | Medium for spectral analysis | DMSO-d⁶ for NMR, ethanol for UV-Vis studies [28] |

| Basis Sets | Mathematical functions for electron distribution | 6-311G(d,p) for main elements, LANL2DZ for transition metals [15] [27] |

| X-ray Crystallography Equipment | Definitive structural determination | Bruker APEX-II CCD diffractometer with MoKα radiation [29] |

Advanced Integration: Machine Learning and High-Throughput Methods

The integration of computational and experimental approaches is evolving beyond simple validation cycles toward predictive frameworks incorporating machine learning (ML). Recent studies demonstrate that ML models trained on DFT+U results can accurately predict band gaps and lattice parameters of metal oxides at a fraction of the computational cost [30]. For rutile TiO₂, optimal (Up, Ud/f) pairs of (8 eV, 8 eV) were identified through extensive DFT+U calculations and successfully generalized using ML approaches [30].

Similarly, benchmarking studies of neural network potentials (NNPs) trained on large computational datasets like OMol25 show promising results in predicting charge-related properties such as reduction potentials, sometimes surpassing the accuracy of low-cost DFT methods for organometallic species [31]. These approaches represent the next frontier in computational-experimental integration, where machine learning models trained on validated computational data can rapidly screen new compounds before resource-intensive experimental synthesis.

The integration of computational and experimental approaches represents a paradigm shift in metal complex research, offering capabilities exceeding either method in isolation. Experimental spectroscopy provides essential validation of computational predictions, while DFT calculations offer atomic-level insights that explain experimental observations and guide new synthetic targets.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the strategic implementation of both approaches involves: (1) using initial computational screening to prioritize synthetic targets, (2) employing multiple experimental techniques to comprehensively characterize new complexes, (3) validating and refining computational models against experimental data, and (4) leveraging the validated models for predicting properties and activities of related compounds.

This synergistic approach significantly accelerates the development of new materials and pharmaceutical agents while providing deeper fundamental understanding of structure-property relationships. As both computational power and experimental techniques continue to advance, this integration will become increasingly central to research and development in metal complex chemistry and related fields.

From Theory to Practice: Protocols for Integrating DFT and Spectroscopy in Research

Density Functional Theory (DFT) serves as the cornerstone of modern computational chemistry, enabling researchers to predict the structure, reactivity, and electronic properties of molecules and materials. However, the accuracy of these predictions critically depends on the selection of appropriate exchange-correlation functionals and basis sets. This guide provides an objective comparison of computational methods based on recent benchmarking studies from authoritative sources like the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and other research institutions, with a specific focus on validating calculations against experimental spectroscopic data for metal complexes.

The challenge for researchers lies in navigating the vast landscape of available computational approaches without clear guidance on which methods perform best for specific chemical systems, particularly for transition metals which present unique difficulties due to their multiconfigurational nature and strong electron correlation effects. This guide synthesizes recent benchmarking data to help researchers make informed choices that balance computational cost with predictive accuracy, especially when working with experimental spectroscopic validation.

Performance Comparison of Computational Methods

Benchmarking Ground-State Geometries of Iron Complexes

A comprehensive 2025 benchmark study evaluated 16 computational methods for predicting ground-state geometries of mononuclear iron coordination complexes against experimental X-ray structures. The study encompassed 17 structurally diverse iron complexes with variations in oxidation state, coordination number, and ligand environments [32].

Table 1: Performance of Computational Methods for Iron Complex Geometries

| Computational Method | Type | Performance Ranking | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| TPSSh(D4) | Hybrid Meta-GGA | 1st (Best) | Superior accuracy for diverse iron coordination complexes |

| r²SCAN-3c | Composite Method | Competitive | Balanced performance for geometry optimization |

| PBEh-3c | Composite Method | Competitive | Good accuracy with computational efficiency |

| B3LYP/G(D4) | Hybrid GGA | Moderate | Widely used but outperformed by meta-hybrids |

| GFN1-xTB | Tight-Binding | Lower | Computational efficiency but reduced accuracy |

The meta-hybrid functional TPSSh(D4) demonstrated the best overall performance, establishing it as the preferred method for geometry optimizations of iron coordination complexes. The study found that higher rungs on Jacob's ladder do not necessarily deliver more robust results, with hybrid methods like TPSSh and B3LYP generally outperforming more computationally expensive alternatives [32].

Benchmarking UV-Vis Spectral Predictions for Iron Complexes

The same study conducted extensive benchmarking of 13 density functionals for predicting UV-Vis absorption spectra of iron complexes using time-dependent DFT (TD-DFT) calculations. Performance was evaluated based on both excitation energies and overall spectral shape similarity to experimental spectra [32].

Table 2: Performance of TD-DFT Functionals for Iron Complex UV-Vis Spectra

| Functional | Type | Excitation Energy Accuracy | Spectral Shape Reproduction | Overall Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O3LYP | Hybrid GGA | 1st (Best) | Moderate | Best for excitation energies |

| revM06-L | Meta-GGA | Moderate | 1st (Best) | Best for spectral shape |

| ωB97X | Range-Separated Hybrid | High | High | Balanced performance |

| CAM-B3LYP | Range-Separated Hybrid | High | High | Good for charge transfer |

| B3LYP/G | Hybrid GGA | Moderate | Moderate | Commonly used benchmark |

For excitation energies, the hybrid functional O3LYP provided the most accurate results with the lowest average energy shift. Meanwhile, the meta-GGA functional revM06-L demonstrated exceptional performance for reproducing the overall spectral shape, achieving the highest median similarity to experimental spectra. Range-separated functionals like ωB97X and CAM-B3LYP showed robust performance across both metrics, particularly important for systems with metal-ligand charge transfer (MLCT) character [32].

Alternative Methods for Charge-Related Properties

Beyond traditional DFT, recent studies have benchmarked neural network potentials (NNPs) against DFT and semiempirical methods for predicting charge-related properties like reduction potentials and electron affinities.

Table 3: Performance Comparison for Reduction Potential Prediction (Mean Absolute Error in V)

| Method | Main-Group Species (OROP) | Organometallic Species (OMROP) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| B97-3c | 0.260 | 0.414 | Consistent performer across systems |

| UMA-S (NNP) | 0.261 | 0.262 | Superior for organometallics |

| UMA-M (NNP) | 0.407 | 0.365 | Moderate performance |

| eSEN-S (NNP) | 0.505 | 0.312 | Excellent for organometallics only |

| GFN2-xTB | 0.303 | 0.733 | Poor for organometallic systems |

Surprisingly, certain OMol25-trained neural network potentials (particularly UMA-S) demonstrated accuracy comparable to or exceeding traditional DFT methods for predicting reduction potentials of organometallic species, despite not explicitly incorporating charge-based physics in their architecture. This suggests their potential as efficient alternatives for specific computational tasks involving transition metal complexes [31].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Benchmarking Workflow for Computational Methods

The validation of computational methods follows a systematic workflow that ensures direct comparability between theoretical predictions and experimental measurements. The benchmark study on iron complexes established a rigorous protocol that can be adapted for validating other metal complex systems [32].

Reference Data Collection and Processing

The benchmarking methodology begins with careful selection of experimental reference data. For the iron complexes study, 17 structurally diverse complexes were selected from the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD), with counterions and solvent molecules excluded to focus solely on the metal complex [32].

Experimental UV-Vis spectra were digitized from literature and converted from wavelength to energy units using the Jacobian transformation factor (hc/E²) to properly scale intensity. Spectra were then smoothed and interpolated to a standard 100 cm⁻¹ interval between points to enable direct comparison with computed spectra. This standardization process is crucial for ensuring fair and quantitative comparisons between theoretical and experimental results [32].

Spectral Comparison Methodology

For UV-Vis spectral predictions, the study employed a quantitative ranking analysis that considered both excitation energies and overall spectral shape. The computed spectra were processed using optimized Gaussian broadening parameters and energy shifts before comparison with experimental data. This approach addresses the challenge that computed excited-state properties cannot be directly compared with experimental measurements without appropriate spectral modeling [32].

The similarity between computed and experimental spectra was quantified using a rigorous metric that accounts for both the positions and relative intensities of absorption features. This methodology represents a significant advancement over qualitative comparisons or single-excitation energy evaluations that have limited reliability for assessing complete spectral profiles.

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools

This section details essential computational tools and resources referenced in the benchmarking studies that researchers can utilize for their own computational workflows.

Table 4: Essential Computational Resources for DFT Benchmarking

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| NIST CCCBDB | Database | Experimental reference data for benchmarking | Online [33] |

| Cambridge Structure Database | Database | Experimental crystallographic structures | Subscription |

| BenchQC | Toolkit | Benchmarking toolkit for quantum computations | Open Source [34] [35] |

| Qiskit Nature | Software | Quantum computation of electronic structure | Open Source [35] |

| Interatomic Potentials Repository | Database | Validated interatomic potentials | NIST Website [36] [37] |

The NIST Computational Chemistry Comparison and Benchmark Database (CCCBDB) provides extensive reference data for validating computational methods, containing carefully curated experimental results that serve as reliability benchmarks [33]. The Cambridge Structure Database remains an essential source for experimental crystallographic data used in geometry benchmarking studies [32].

For emerging quantum computing approaches, BenchQC offers a specialized benchmarking toolkit for evaluating variational quantum algorithms like the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) when applied to chemical systems. This toolkit systematically evaluates key parameters including classical optimizers, circuit types, basis sets, and noise models [34] [35].

The Interatomic Potentials Repository maintained by NIST provides validated potentials for molecular dynamics simulations, including recently developed machine learning interatomic potentials with DFT-level accuracy for specific metallic systems like α-Fe [36] [37].

The benchmarking studies conducted by NIST and other research institutions provide clear guidance for researchers selecting computational methods for metal complexes research. For ground-state geometry optimization of iron complexes, the meta-hybrid functional TPSSh(D4) delivers superior performance. For UV-Vis spectral predictions, the choice depends on the priority: O3LYP for excitation energy accuracy versus revM06-L for overall spectral shape reproduction.

The integration of rigorous benchmarking workflows, utilizing standardized reference data from sources like the NIST CCCBDB and Cambridge Structural Database, ensures that computational methods can be objectively validated against experimental measurements. As computational chemistry continues to evolve, with emerging approaches like neural network potentials and quantum computing algorithms, these benchmarking methodologies will remain essential for establishing reliability and guiding method selection in metal complexes research.

In modern drug development, accurately predicting the antioxidant activity of potential therapeutic compounds is crucial. Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations provide a powerful theoretical framework for modeling molecular interactions and predicting antioxidant behavior at the atomic level. However, the true test of these computational predictions lies in their validation against robust experimental data. This case study examines the antioxidant mechanisms of crocin, a primary bioactive compound in saffron, focusing specifically on its interaction with hydroxyl radicals (•OH). We explore how computational chemistry, particularly DFT, provides a theoretical foundation for understanding these mechanisms and how experimental spectroscopic techniques serve to confirm these predictions. The integration of these approaches provides a comprehensive validation framework essential for pharmaceutical development, where understanding precise molecular interactions guides the creation of more effective and targeted antioxidant-based therapies.

Crocin as a Model Antioxidant: Properties and Therapeutic Potential

Crocin, a water-soluble carotenoid, has garnered significant research interest due to its potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Numerous studies have demonstrated its therapeutic potential across various disease models. For instance, crocin administration has been shown to significantly alleviate anxiety and depressive-like behaviors in animal models, with biochemical analysis revealing that its mechanism involves improving the balance between oxidative stress and antioxidant biomarkers [38]. Furthermore, crocin protects cardiac cells and inhibits inflammation by modulating key molecular signaling pathways, including TLR4/PTEN/AKT/mTOR/NF-κB and microRNA (miR-21) [39]. Its protective effects extend to neutralizing excess free radicals and preventing their formation, positioning it as a multi-faceted antioxidant compound [40]. The extensive pharmacological profile of crocin, combined with its natural origin, makes it an ideal candidate for a case study on validating antioxidant mechanisms.

Computational Approaches: Predicting Antioxidant Activity with DFT

Fundamentals of DFT in Antioxidant Research

Density Functional Theory (DFT) is a computational quantum mechanical modeling method used to investigate the electronic structure of molecules. In antioxidant research, it helps predict how a molecule like crocin will interact with free radicals. DFT calculations can model various antioxidant mechanisms, including:

- Formal Hydrogen Atom Transfer (f-HAT)

- Single Electron Transfer (SET)

- Sequential Proton Loss Electron Transfer (SPLET)

- Radical Adduct Formation (RAF) [41] [42]

These computational approaches allow researchers to determine thermodynamic parameters such as bond dissociation energies (BDE) and ionization potentials (IP), which indicate how easily a molecule can donate a hydrogen atom or electron to neutralize a free radical. Kinetic calculations further provide theoretical rate constants for these reactions, offering a prediction of antioxidant efficacy before laboratory testing [41] [42].

Practical Application: Modeling Metal Complex Antioxidants

The predictive power of DFT extends to metal complexes, which often exhibit enhanced antioxidant activity compared to their free ligands. For example, studies on novel copper(II) complexes use B3LYP/GENECP level theory with mixed basis sets (6-311G(d, P) for light atoms and LANL2DZ for metals) to optimize molecular geometry and calculate electronic properties [15]. These calculations predict key characteristics such as:

- HOMO-LUMO energy gaps (indicating chemical stability and reactivity)

- Molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) maps (showing charge distribution)

- Natural bond orbital (NBO) analysis (revealing intramolecular interactions)

- Global and local chemical reactivity descriptors [15] [4] [43]

Similar computational approaches have been applied to trivalent metal complexes of Schiff base ligands, where DFT calculations successfully predicted that the metal complexes would be more stable than the free ligand and provided insights into their electronic transitions and nonlinear optical properties [4]. The table below summarizes key parameters derived from DFT studies of crocin and relevant metal complexes with antioxidant potential.

Table 1: Key Computational Parameters from DFT Studies of Antioxidant Compounds

| Compound | Calculation Method | HOMO-LUMO Gap (eV) | Predicted Mechanism | Global Reactivity Descriptors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crocin (theoretical) | M06-2X/6-311++G(d,p) | Data not specified in sources | HAT, SET, RAF | Data not specified in sources |

| Cu(II)-PQMHC Complex [15] | B3LYP/GENECP | Non-zero (specific value not provided) | Coordination via O₂N tridentate | High dipole moment, detailed NBO analysis |

| Schiff Base Metal Complexes [4] | B3LYP/LANL2DZ | 1.64 - 3.68 (varies by metal) | Radical scavenging | Varying chemical hardness/softness based on metal |

| Benzothiazole Metal Complexes [43] | B3LYP/TD-DFT | Small gaps indicating ICT | DNA binding, enzyme inhibition | High polarity, NLO properties |

Experimental Validation: Spectroscopic and Biochemical Assays

Spectroscopic Characterization of Antioxidant Compounds

Experimental validation of DFT predictions requires comprehensive spectroscopic characterization. For metal complexes, this typically includes:

- FT-IR Spectroscopy: Identifies functional groups and coordination sites

- Electronic Spectroscopy (UV-Vis): Determines electronic transitions and complex geometry

- Electron Spin Resonance (ESR): Provides information on unpaired electrons in metal complexes

- Thermal Analysis (TGA/DTA): Assesses thermal stability and decomposition patterns [15] [4] [43]

For example, in the study of a novel Cu(II)-pyranoquinoline complex, these techniques confirmed that the ligand behaves as an O₂N tridentate donor, coordinating through hydroxyl groups, azomethine nitrogen, and keto oxygen to form a square planar geometry—a finding that aligned with DFT-predicted optimized geometries [15].

Biochemical Assays for Antioxidant Activity