Valence and Conduction Bands in Photocatalysis: Fundamentals, Engineering Strategies, and Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the critical role valence and conduction bands play in governing photocatalytic reactions.

Valence and Conduction Bands in Photocatalysis: Fundamentals, Engineering Strategies, and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the critical role valence and conduction bands play in governing photocatalytic reactions. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental principles of band theory, advanced band engineering methodologies, and solutions to common challenges like charge recombination. By synthesizing foundational concepts with the latest material innovations and validation techniques, this review serves as a strategic guide for optimizing photocatalytic systems, with a specific outlook on their potential implications in biomedical research and clinical applications.

Band Theory Fundamentals: How Energy Levels Govern Photocatalytic Activity

Band theory is the fundamental framework that describes the electronic structure of solids and their resulting electrical conductivity. It provides the foundational principles for understanding how materials behave as metals, semiconductors, or insulators. In the context of photocatalytic reactions, which are crucial for addressing global energy and environmental challenges such as water splitting for hydrogen production and pollutant degradation, band theory offers the critical parameters for designing efficient photocatalysts [1] [2]. The global energy demand is projected to be 35-60% higher in 2030 compared to 2010 levels, driving urgent need for sustainable technologies [1]. Semiconductor photocatalysis represents a promising green technology that directly converts solar energy into chemical energy, with the seminal work of Fujishima and Honda in 1972 demonstrating water splitting using titanium dioxide (TiOâ‚‚) electrodes under UV light [1] [2].

The central premise of band theory in photocatalysis research is that the electronic band structure of a semiconductor determines its capability to absorb light and drive chemical reactions. When light of appropriate energy strikes a semiconductor photocatalyst, it can promote electrons from the valence band to the conduction band, creating electron-hole pairs that subsequently migrate to the surface and participate in redox reactions [1] [2]. The efficiency of this process depends critically on the relationship between three fundamental concepts: the valence band, conduction band, and the band gap separating them. This relationship governs not only light absorption characteristics but also charge carrier generation, separation, transport, and eventual surface reactivity—all determining factors in photocatalytic efficiency [2].

Core Principles of Band Theory

Valence Band, Conduction Band, and Band Gap

In solid-state physics, the valence band represents the highest range of electron energies where electrons are normally present at absolute zero temperature. These electrons are bound to atoms and participate in chemical bonding but are not free to move through the material. Located above the valence band is the conduction band, which represents the lowest range of vacant electronic states where electrons can move freely and conduct electricity [3].

The crucial parameter separating these bands is the band gap (E_g)—an energy range in a solid where no electron states can exist due to the quantization of energy [3]. The size of this band gap fundamentally determines a material's electrical classification:

- Conductors (Metals): The valence and conduction bands overlap, allowing free electron flow even without external energy input [3].

- Semiconductors: A relatively small band gap (typically 0.1-3.0 eV) separates the valence and conduction bands. At absolute zero, semiconductors behave as insulators, but at room temperature, thermal energy can excite some electrons across the gap, enabling moderate conductivity [3].

- Insulators: A large band gap (typically >3.0 eV) prevents significant electron excitation at ordinary temperatures, resulting in minimal electrical conductivity [3].

For photocatalytic applications, semiconductors are particularly important because their band gap can be engineered to match the energy of visible light photons, making them ideal for solar-driven processes [4] [1].

Band Theory in Photocatalytic Mechanisms

In heterogeneous photocatalysis, the process begins when a semiconductor absorbs light with energy equal to or greater than its band gap, promoting an electron (eâ») from the valence band to the conduction band. This transition leaves behind a positively charged hole (hâº) in the valence band, creating an electron-hole pair [1] [2].

The photogenerated charge carriers then undergo several competitive processes:

- Charge separation: Electrons and holes move independently through the material

- Recombination: Electrons fall back into holes, dissipating energy as heat

- Surface reactions: Carriers reach the surface and drive redox reactions [2]

The holes in the valence band are powerful oxidants that can react with water to produce hydroxyl radicals (•OH), which are strong oxidizers capable of degrading organic pollutants. Meanwhile, the electrons in the conduction band are reductants that can react with oxygen to form superoxide ions (Oâ‚‚â») or reduce water to produce hydrogen gas [1].

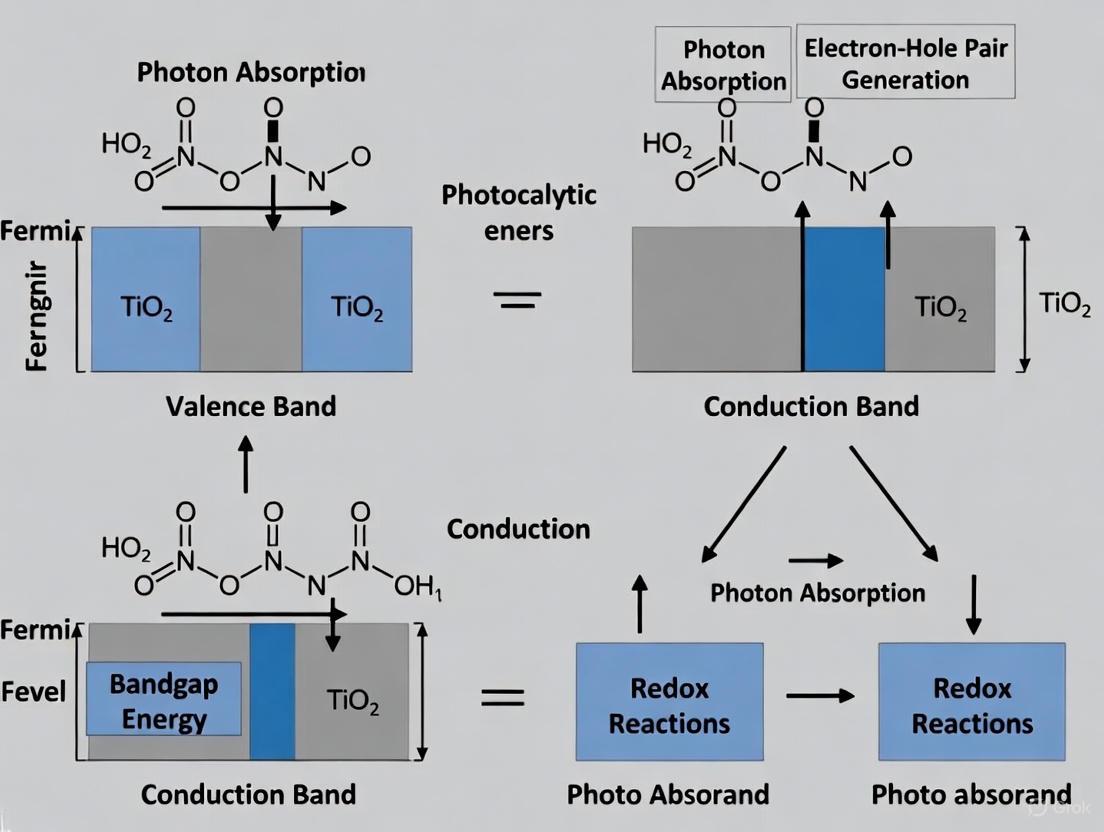

The following diagram illustrates this fundamental photocatalytic process and the central role of band structure:

Diagram 1: Fundamental photocatalytic process driven by band theory principles

Band Engineering for Enhanced Photocatalysis

Strategies for Band Structure Modification

A significant challenge in semiconductor photocatalysis is that many materials with appropriate band positions for redox reactions have band gaps that are too wide for efficient solar light absorption. For instance, TiO₂—one of the most studied photocatalysts—has a band gap of approximately 3.2 eV for the anatase phase, which restricts its light absorption to the UV region (only about 4% of the solar spectrum) [4] [2]. To address this limitation, researchers have developed several band engineering strategies:

Doping: Introducing specific impurity atoms into a semiconductor lattice can create intermediate energy states within the band gap, effectively reducing the energy required for electron excitation [4]. For TiOâ‚‚, nonmetal-metal co-doping has been predicted to narrow the band gap to about 2.72 eV, shifting the absorption edge to 457.6 nm in the visible range [4]. The (N, Ta) donor-acceptor combination is particularly promising, with a calculated band gap of 2.71 eV [4].

Nanostructuring: Quantum confinement effects in semiconductor nanoparticles can tune band gap properties. As particle size decreases below the effective Bohr radius of the exciton, the conduction and/or valence band edges shift to higher energy levels, increasing the band gap [3]. This size-dependent edge shifting provides a mechanism to control band structures for specific applications [3].

Composite Materials: Creating heterostructures between different semiconductors can facilitate charge separation across material interfaces, reducing recombination losses and enhancing photocatalytic efficiency [2].

Quantitative Analysis of Band Engineering

The effectiveness of band engineering strategies is evident in computational and experimental studies across various material systems. The table below summarizes band gap modifications achieved through different approaches:

Table 1: Band gap engineering in photocatalytic materials

| Material | Modification Strategy | Original Band Gap (eV) | Modified Band Gap (eV) | Absorption Shift | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anatase TiO₂ | (N, Ta) co-doping | 3.20 | 2.71 | UV → 457.6 nm (visible) | Raises VB edge significantly, increases CB edge by 0.24 eV | [4] |

| Nb₃O₇(OH) | Ta doping | 1.70 | 1.266 | UV/visible → enhanced visible | Relocates Fermi level, increases charge carrier mobility | [5] |

| Nb₃O₇(OH) | Sb doping | 1.70 | 1.203 | UV/visible → enhanced visible | Direct band behavior maintained, optical threshold shifts to visible region | [5] |

| Semiconductor Nanocrystals | Size reduction to quantum scale | Material-dependent | Size-dependent increase | Blue shift | Discrete optical transitions when restricted by exciton confinement | [3] |

Band engineering must balance multiple factors: while reducing the band gap extends light absorption into the visible region, it must not compromise the redox potential of the photogenerated charge carriers. The conduction band minimum must remain sufficiently negative to drive reduction reactions (such as hydrogen evolution), while the valence band maximum must remain sufficiently positive to drive oxidation reactions (such as water oxidation or pollutant degradation) [4] [2].

Computational and Experimental Methodologies

Theoretical Framework and Computational Approaches

Computational methods play a crucial role in band structure design and prediction of photocatalytic properties. Density Functional Theory (DFT) has emerged as the predominant approach for calculating electronic band structures of photocatalytic materials [2] [5]. The standard methodology involves:

Structural Optimization: The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) is commonly used for geometric optimization of crystal structures [5]. For instance, in studies of Nb₃O₇(OH), GGA provides precise functional for determining lattice parameters and internal coordinates [5].

Band Structure Calculations: The standard approach involves evaluating material band eigenstates across k-space, examining band dispersion along high-symmetry paths in the Brillouin zone [2]. Alternative methods include density of states (DOS) calculations, which integrate across k-space to determine valence and conduction band limits [2].

Band Gap Accuracy: Traditional DFT with GGA functionals notoriously underestimates band gaps due to electronic self-interaction error [2]. More advanced approaches include:

- Hybrid functionals (mixing Hartree-Fock exchange with DFT)

- Trans-Blaha modified Becke-Johnson approximation (TB-mBJ)

- Many-body perturbation theory (GW methods) [2] [5]

For example, in studying Ta/Sb-doped Nb₃O₇(OH), TB-mBJ with spin-orbit coupling provides more accurate electronic structure and optical properties compared to standard GGA [5].

Optical Properties Calculation: Programs like the OPTIC code implemented in WIEN2k can compute dielectric functions, reflectivity, and electron energy loss functions from the electronic band structure [5].

Experimental Characterization Techniques

Experimental validation of band structures employs several complementary techniques:

UV-Vis Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy: Measures the absorption edge of powdered semiconductors, allowing determination of the band gap energy through Tauc plot analysis [4] [5].

Photoelectron Spectroscopy: X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS) directly measure valence band positions and work functions [4].

Electrochemical Methods: Mott-Schottky analysis determines flat band potentials and semiconductor type (n-type or p-type), providing information about band edge positions relative to solution redox potentials [2].

Photoluminescence Spectroscopy: Probes charge carrier recombination processes, providing indirect information about band gap states and defect levels [1].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated computational and experimental approach to band structure design for photocatalysis:

Diagram 2: Integrated workflow for photocatalytic material development

Table 2: Essential research tools for band structure and photocatalytic studies

| Category | Specific Tool/Resource | Function in Research | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Codes | WIEN2k | Full-potential linearized augmented plane wave (FP-LAPW) method for electronic structure calculations | Band structure, density of states, and optical properties calculation [5] |

| BoltzTraP | Calculates transport properties based on Boltzmann semi-classical theory | Electrical conductivity, Seebeck coefficient, carrier mobility [5] | |

| OPTIC Program | Computes optical properties from electronic structure | Dielectric function, reflectivity, electron energy loss [5] | |

| Experimental Materials | Niobium oxide hydroxide (Nb₃O₇(OH)) | Photocatalyst substrate with favorable band positions | Base material for doping studies; pristine band gap ~1.7 eV [5] |

| Tantalum (Ta) / Antimony (Sb) | Dopant elements for band structure modification | Reduces band gap to ~1.27 eV (Ta) or ~1.20 eV (Sb) [5] | |

| TiOâ‚‚ (Anatase) | Benchmark photocatalyst | Reference material; band gap engineering via co-doping [4] | |

| Characterization Techniques | UV-Vis Spectrophotometry | Band gap determination via Tauc plot | Measuring absorption edge shifts after doping [5] |

| X-ray Diffraction (XRD) | Structural characterization and phase identification | Verifying crystal structure and dopant incorporation [5] |

Current Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite significant advances in band theory applications for photocatalysis, several challenges remain. A primary issue is the charge carrier recombination that competes with surface redox reactions. As illustrated in recent perspectives, the time scales for various processes in heterogeneous photocatalysis create fundamental limitations: electronic relaxation occurs in attosecond-femtosecond scales, while charge diffusion to surfaces occurs in picosecond scales, and photocatalytic reactions proceed on even longer time scales [2]. This asymmetry leads to substantial recombination losses before charges can participate in useful chemistry [2].

Future research directions focus on dynamic excited-state properties rather than static ground-state band structures. Nonadiabatic molecular dynamics simulations are emerging as powerful tools to describe the time evolution of photogenerated species and their propagation through crystalline structures, providing crucial information about charge carrier lifetimes [2]. Additionally, there is growing recognition that understanding photocatalytic mechanisms requires analysis of excited-state potential energy surfaces rather than conventional ground-state analysis [2].

The development of standardized computational frameworks for heterogeneous photocatalysis would accelerate progress. Such frameworks would integrate static and dynamic properties of relevant excited states with the chemistry of interest reactions, explicitly exploring the nature of charge carriers, excited-state potential energy surfaces, and their temporal evolution [2].

As computational power increases and methods refine, the ultimate goal remains the ab initio design of photocatalysts with tailored band structures that maximize solar energy conversion efficiency while maintaining sufficient redox power for target reactions. This approach promises to transform photocatalysis from largely empirical materials screening to rational design based on fundamental band theory principles.

Photocatalysis represents a promising pathway for addressing global energy shortages and environmental pollution by converting solar energy into chemical energy [6] [7]. This process, pioneered by Fujishima and Honda's groundbreaking work on TiOâ‚‚ electrodes, leverages semiconductor materials to drive chemical reactions using light energy [8] [9]. At the heart of this technology lies a sophisticated sequence of events beginning with photon absorption and culminating in surface redox reactions, with charge carrier generation serving as the critical initial step that enables all subsequent processes [8] [7].

The efficiency of photocatalytic systems depends fundamentally on the properties of the semiconductor materials employed, particularly their band structure, which governs both light absorption capability and the thermodynamic potential of generated charge carriers [9]. This technical guide examines the foundational principles of the photocatalytic process, with specific focus on the mechanisms of photon absorption and charge carrier generation, framed within contemporary research on valence and conduction band engineering.

Fundamental Principles of Semiconductor Photocatalysis

Band Structure and Energy Requirements

Semiconductor photocatalysts possess a characteristic electronic structure featuring a valence band (VB) filled with electrons, a conduction band (CB) that is largely empty, and a forbidden energy region between them known as the band gap (Eð‘”) [8] [9]. When a semiconductor absorbs photons with energy equal to or greater than its band gap energy, electrons are excited from the valence band to the conduction band, creating electron-hole pairs (eâ»cb and hâºvb) [8].

For photocatalytic water splitting, the semiconductor band structure must satisfy specific thermodynamic requirements. The conduction band minimum must be more negative than the redox potential of Hâº/Hâ‚‚ (0 V vs. NHE), while the valence band maximum must be more positive than the redox potential of Oâ‚‚/Hâ‚‚O (1.23 V vs. NHE) [9]. Considering kinetic overpotentials for oxygen and hydrogen evolution reactions, the actual band gap required for unassisted photocatalytic water splitting typically exceeds 1.5 eV [9].

Table 1: Band Gap Energies and Theoretical Efficiency Limits for Selected Photocatalysts

| Photocatalyst | Band Gap (eV) | Light Absorption Edge (nm) | Theoretical STH Efficiency Limit | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anatase TiOâ‚‚ | 3.2 [8] [9] | 388 [9] | ~1% [9] | UV-driven pollutant degradation [8] |

| Monoclinic WO₃ | 2.6 [9] | 477 [9] | ~6% [9] | Photoelectrochemical water oxidation [9] |

| α-Fe₂O₃ (Hematite) | 2.1 [9] | 590 [9] | ~15% [9] | Photoelectrochemical water splitting [9] |

| CaTiO₃ (Pristine) | 2.77 [10] | 448 [10] | - | Model perovskite photocatalyst [10] |

| S/Zr co-doped CaTiO₃ | 1.85-2.22 [10] | 560-670 [10] | Enhanced vs. pristine [10] | Visible-light water splitting [10] |

The Photocatalytic Process: A Stepwise Workflow

The fundamental photocatalytic process encompasses three primary stages: photon absorption and charge carrier generation, charge separation and migration, and surface redox reactions. The following diagram illustrates this complete workflow, with emphasis on the initial charge generation step that forms the foundation for all subsequent processes.

Diagram 1: Photocatalytic process workflow from photon absorption to surface reactions.

Photon Absorption and Charge Carrier Generation

The photocatalytic process initiates when a semiconductor absorbs photons with energy (hν) equal to or greater than its bandgap energy (Eð‘”), promoting electrons from the valence band to the conduction band [8]. This process can be represented by the fundamental equation:

TiOâ‚‚ + hν → TiOâ‚‚ (eâ»cb + hâºvb) [8]

The photogenerated charge carriers possess reductive and oxidative capacities determined by the conduction band and valence band potential of the semiconductor, respectively [8]. For TiOâ‚‚, the photogenerated holes demonstrate very high oxidative activity, enabling degradation of most organic contaminants present in water and air [8].

The timescales involved in charge carrier generation are exceptionally rapid. Interband transitions occur in the femtosecond (fs) timescale when photon energy exceeds the band gap energy [8]. Both electrons and holes then move randomly to the surface of the photocatalyst where they become trapped in the sub-picosecond time domain [8].

Band Engineering for Enhanced Light Absorption

A significant challenge in photocatalysis is that wide bandgap semiconductors like TiOâ‚‚ (3.2 eV) primarily absorb ultraviolet light, utilizing only approximately 4% of the solar spectrum [11] [6]. This limitation has stimulated extensive research into band engineering strategies to enhance visible light absorption.

Doping and heterojunction construction represent two prominent approaches for modifying band structures. For instance, doping Nb₃O₂(OH) with tantalum (Ta) or antimony (Sb) decreases the band gap from 1.7 eV (pristine) to 1.266 eV (Ta-doped) or 1.203 eV (Sb-doped), significantly enhancing visible light absorption [11]. Similarly, S/Zr co-doping in CaTiO₃ perovskite reduces the band gap from 2.77 eV to 1.85-2.22 eV while transforming the band structure from indirect to direct, further improving light absorption efficiency [10].

Quantum confinement effects provide another powerful strategy for band engineering. As demonstrated with WO₃ quantum dots, strict size control below 1.8 nm enables tuning of the conduction band edge from +0.18 VSHE to -0.10 VSHE, remarkably enhancing photoreduction of proton and molecular oxygen [12].

Table 2: Band Engineering Strategies and Their Effects on Photocatalytic Materials

| Strategy | Material System | Band Gap Modification | Effect on Photocatalytic Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elemental Doping | Ta/Sb-doped Nb₃O₇(OH) | Reduction from 1.7 eV to 1.203-1.266 eV [11] | Red-shift of optical threshold to visible region [11] |

| Co-doping | S/Zr-doped CaTiO₃ | Reduction from 2.77 eV to 1.85-2.22 eV [10] | Enhanced visible light absorption for hydrogen production [10] |

| Heterojunction Construction | Cuâ‚‚O/TiOâ‚‚/Cu | Band alignment favoring charge separation [6] | Hydrogen production rate of 279.53 μmol·gâ»Â¹Â·hâ»Â¹ (25× enhancement) [6] |

| Quantum Size Effect | WO₃ quantum dots (0.66-1.79 nm) | Band gap expansion from 2.87 eV to 3.45 eV with decreasing size [12] | Upshift of CBE enables photoreduction impossible with bulk WO₃ [12] |

| Valence State Control | Cuâ‚‚O/TiOâ‚‚ vs. Cuâ‚‚O/TiOâ‚‚/Cu | Variation of Cu valence states influences band positions [6] | Different product selectivity: Hâ‚‚ production vs. CO production [6] |

Experimental Protocols for Charge Generation Studies

Synthesis of Band-Engineered Quantum Dots

Objective: Precise size control of WO₃ quantum dots to engineer conduction band position through quantum confinement effects [12].

Materials:

- Template: Supermicroporous silicas (SMPSs) with controlled pore sizes

- Precursor: Tungsten-based precursor solution

- Solvents: Appropriate solvents for precursor preparation

Methodology:

- Pore Size Selection: Choose SMPSs with specific pore sizes to determine ultimate QD dimensions

- Precursor Impregnation: Control the amount of WO₃ precursor solution impregnated into SMPSs

- In-Situ Synthesis: Form WO₃ quantum dots within the confined spaces of SMPS pores

- Characterization: Verify successful synthesis and size distribution using:

- Field Emission Transmission Electron Microscopy (FE-TEM)

- Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDX)

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) to confirm tungsten(VI) species and exclude significant Wâµâº defects [12]

Key Parameters:

- Precise control of QD size between 0.66-1.79 nm through manipulation of SMPS pore size and precursor concentration [12]

- Confirmation of narrow size distribution through FE-TEM imaging [12]

- Absence of defect absorption in UV-Vis spectra indicating minimal surface defects [12]

Conduction Band Edge Determination

Objective: Experimental evaluation of conduction band edge (CBE) potential for quantum-confined structures [12].

Materials:

- Synthesized WO₃ quantum dots

- Phenol or derivatives for surface complexation

- Spectrophotometer with UV-Vis capability

- Photoemission yield spectroscopy in air (PYSA) equipment

Methodology:

- Surface Complexation: Form complexes between WO₃-QDs and phenol

- Optical Characterization: Record absorption spectra of Cn×m/phenol complexes

- Charge-Transfer Excitation Energy: Determine ECT from Tauc plots of the complexes

- HOMO Level Reference: Establish phenol HOMO level at 1.73 VSHE using PYSA [12]

- CBE Calculation: Apply the equation: ECBE = EHOMO(phenol) - ECT [12]

Validation:

- Correlation of estimated CBE values with theoretical predictions based on effective mass approximation [12]

- Calculation of electron and hole effective masses (me = 2.39m₀, mh = 3.83m₀ for WO₃) [12]

- Confirmation that CBE upshift exceeds valence band downshift in quantum-confined systems [12]

Advanced Characterization Techniques

Understanding charge carrier dynamics requires sophisticated characterization methods that probe processes across multiple timescales. The following diagram illustrates the relationship between various characterization techniques and the specific charge transfer processes they analyze.

Diagram 2: Characterization techniques for analyzing charge carrier dynamics.

Key Characterization Methods

Transient Absorption Spectroscopy (TAS): Probes charge carrier generation and early recombination dynamics on femtosecond to nanosecond timescales, providing critical information about initial charge separation efficiency [7].

Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (TRPL): Measures charge carrier recombination rates through luminescence decay profiles, with longer lifetimes indicating reduced recombination losses [7].

Intensity-Modulated Photocurrent/Voltage Spectroscopy (IMPS/IMVS): Analyzes charge transfer and recombination kinetics in the microsecond to second range, particularly useful for photoelectrochemical systems [7].

Kelvin Probe Force Microscopy (KPFM) and Spatially Resolved Surface Photovoltage (SRSPV): Enable visualization of charge separation processes with spatial resolution, revealing localized charge trapping and transport phenomena [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Photocatalytic Charge Generation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supermicroporous Silicas (SMPSs) | Template for quantum dot synthesis with controlled pore sizes [12] | Size-controlled synthesis of WO₃ quantum dots [12] | Tunable pore size, high surface area, thermal stability |

| Phenol and Derivatives | Surface complexation agents for band edge determination [12] | Experimental evaluation of conduction band edge position [12] | Charge-transfer excitation, known HOMO level (1.73 VSHE) [12] |

| DMPO (5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide) | Spin trap for radical detection in ESR spectroscopy [12] | Monitoring photoreduction of molecular oxygen via Oâ‚‚â» detection [12] | Forms stable spin adducts with superoxide radicals |

| Titanium Butoxide (Ti(OBu)â‚„) | Precursor for TiOâ‚‚ synthesis in heterojunction systems [6] | Preparation of Cuâ‚‚O/TiOâ‚‚ heterojunction photocatalysts [6] | Hydrolyzes to form TiOâ‚‚, compatible with various synthesis methods |

| Copper Acetate | Source of Cu ions for copper-based heterojunctions [6] | Synthesis of CT, CTC, and TC catalysts with different Cu valence states [6] | Transformable between Cu(I) and Cu(0) via redox processes |

| Fructose | Reducing agent in alkaline synthesis environments [6] | Mediating keto-enol tautomerism for Cu valence state control [6] | Undergoes tautomerism to glucose, which reduces copper species |

| 2,2,7-Trimethylnonane | 2,2,7-Trimethylnonane, CAS:62184-53-6, MF:C12H26, MW:170.33 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 5-Undecynoic acid, 4-oxo- | 5-Undecynoic acid, 4-oxo-, CAS:61307-46-8, MF:C11H16O3, MW:196.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The process of photon absorption and charge carrier generation represents the fundamental initiating event in semiconductor photocatalysis, establishing the foundation upon which all subsequent efficiency depends. Through strategic band engineering approaches—including elemental doping, heterojunction construction, quantum confinement, and valence state control—researchers can precisely tune both the light absorption characteristics and the redox potential of photogenerated charge carriers. Contemporary research continues to refine our understanding of charge carrier dynamics through advanced characterization techniques capable of probing processes across femtosecond to second timescales. As band engineering strategies become increasingly sophisticated and characterization methods more precise, the rational design of high-efficiency photocatalytic systems for solar energy conversion and environmental remediation continues to advance toward practical implementation.

Semiconductor photocatalysis has emerged as a promising technology for addressing global energy and environmental challenges, including solar water splitting and pollutant degradation [1] [13]. The effectiveness of these processes fundamentally depends on the electronic band structure of the semiconductor materials employed. The band structure dictates how a material interacts with light, generates charge carriers, and facilitates redox reactions at its surface [12]. For photocatalytic reactions to occur efficiently, photoexcited electrons in the conduction band and holes in the valence band must possess sufficient energy to drive reduction and oxidation reactions, respectively [12]. This technical guide examines the key band structure parameters—specifically band edge positions and band gap widths—and their thermodynamic significance in photocatalytic systems, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for material selection and design.

Core Band Structure Parameters

Band Gap Width and Photon Absorption

The band gap width represents the energy difference between the valence band maximum (VBM) and conduction band minimum (CBM). This parameter determines the minimum photon energy required for electron excitation and thus the portion of the solar spectrum a photocatalyst can utilize [13]. Table 1 summarizes experimental band gap values for selected photocatalytic materials.

Table 1: Band Gap Values of Selected Photocatalytic Materials

| Material | Band Gap (eV) | Light Absorption Range | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| NiSnO₃ sintered at 250°C | 3.38 | UV | [14] |

| NiSnO₃ sintered at 400°C | 2.90 | UV-Vis edge | [14] |

| Pristine Nb₃O₇(OH) | 1.7 | Visible | [5] |

| Ta-doped Nb₃O₇(OH) | 1.266 | Visible | [5] |

| Sb-doped Nb₃O₇(OH) | 1.203 | Visible | [5] |

| WO₃ Quantum Dots | 2.87-3.45 | UV-Vis | [12] |

| TiOâ‚‚ | ~3.0-3.2 | UV | [15] [16] |

Band gap engineering represents a crucial strategy for enhancing light absorption. Quantum confinement effects enable significant band gap tuning in nanoscale materials. For instance, WO₃ quantum dots smaller than 2 nm exhibit band gap expansion from 2.87 to 3.45 eV as particle size decreases [12]. Conversely, doping can reduce band gaps, as demonstrated by Ta and Sb doping in Nb₃O₇(OH), which decreases the band gap from 1.7 eV to 1.266 eV and 1.203 eV, respectively, red-shifting absorption into the visible region [5].

Band Edge Positions and Thermodynamic Requirements

The band edge positions relative to redox potentials determine the thermodynamic feasibility of photocatalytic reactions. The conduction band edge (CBE) must be more negative than the reduction potential of target species, while the valence band edge (VBE) must be more positive than the oxidation potential [12].

For overall water splitting, the thermodynamic minimum band gap requirement is 1.23 eV, corresponding to the water decomposition energy under standard conditions [13]. However, practical photocatalysts require additional overpotential to overcome activation energy barriers for the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) and oxygen evolution reaction (OER) [13]. Figure 1 illustrates these thermodynamic relationships.

Figure 1. Thermodynamic requirements for photocatalytic water splitting. The conduction band must be more negative than the Hâº/Hâ‚‚ redox potential (0 V vs NHE), and the valence band must be more positive than the Hâ‚‚O/Oâ‚‚ potential (+1.23 V vs NHE). The band gap must be ≥1.23 eV.

Experimental studies have demonstrated precise band edge engineering through size control. For WO₃ quantum dots, the CBE was tuned from +0.18 V to -0.10 V vs. SHE (Standard Hydrogen Electrode) by controlling particle size below 1.8 nm, enabling photocatalytic reduction reactions previously impossible with bulk WO₃ [12]. Table 2 provides band edge positions for selected materials.

Table 2: Band Edge Positions of Photocatalytic Materials

| Material | CBE (V vs. NHE) | VBE (V vs. NHE) | Band Gap (eV) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WO₃ QDs (0.66-1.79 nm) | +0.18 to -0.10 | Calculated from CBE + Eg | 2.87-3.45 | [12] |

| Wâ‚‚Oâ‚„-Zn₈Wâ‚â‚€O₃₆ termination | Meets HER requirement | Meets OER requirement | Not specified | [17] |

| Theoretical minimum | ≤ 0 | ≥ +1.23 | ≥ 1.23 | [13] |

Surface termination significantly influences band edge positions. For ZnWOâ‚„(100), the Wâ‚‚Oâ‚„-Zn₈Wâ‚â‚€O₃₆ termination exhibits band edges that simultaneously fulfill HER and OER requirements, unlike other surface terminations [17]. This highlights the critical importance of surface engineering alongside bulk band structure design.

Experimental Methods for Band Structure Analysis

Theoretical Calculation Methods

Computational approaches, particularly density functional theory (DFT), provide powerful tools for predicting band structures. The Trans-Blaha modified Becke-Johnson approximation (TB-mBJ) has proven effective for calculating accurate electronic structures, outperforming standard generalized gradient approximation (GGA) methods which typically underestimate band gaps [5].

DFT Calculation Protocol:

- Structure Optimization: Perform geometric optimization using GGA functionals until residual forces on each atom are less than 0.05 eV/Ã… [15]

- Electronic Calculations: Apply TB-mBJ potential for band structure and density of states calculations [5]

- Band Alignment: Calculate work functions and band edge positions relative to vacuum level [17]

- Optical Properties: Compute frequency-dependent dielectric function to derive absorption coefficients [5]

For doped systems, spin-orbit coupling should be included to properly handle d and f orbitals of dopant atoms. Supercell approaches with appropriate dopant concentrations (e.g., 4.16% for Ta/Sb-doped Nb₃O₇(OH)) effectively model doping effects [5].

Experimental Characterization Techniques

UV-Visible Spectroscopy:

- Purpose: Determine band gap energy via Tauc plot analysis [14]

- Protocol: Measure diffuse reflectance spectra, convert to absorption data, and plot (αhν)⿠versus photon energy (hν)

- For direct band gaps: n = 1/2 [14]

- Application: Used to determine band gap reduction from 3.38 to 2.90 eV in NiSnO₃ with increased sintering temperature [14]

Photoelectron Spectroscopy:

- Purpose: Experimentally determine band edge positions [12]

- Protocol: Form surface complexes with phenol derivatives, measure charge-transfer excitation energy (ECT)

- Calculation: ECBE = EHOMO(phenol) - ECT, where EHOMO(phenol) = 1.73 VSHE [12]

- Advantage: Provides direct experimental measurement of CBE, complementary to theoretical calculations

Photocatalytic Activity Testing:

- Purpose: Validate thermodynamic feasibility of band positions [12]

- Protocol: Evaluate proton reduction and molecular oxygen reduction under UV irradiation using sacrificial reagents

- Monitoring: Employ ESR spin trapping with DMPO to detect superoxide radicals [12]

- Correlation: Relate photocatalytic efficiency to engineered CBE positions

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Band Structure Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Phenol/Catechol Derivatives | Form charge-transfer complexes for experimental CBE determination | WO₃-QDs/phenol complexes for CBE measurement [12] |

| Sacrificial Reagents | Consume photogenerated carriers to isolate specific redox reactions | Ethanol used as hole scavenger in WO₃ QD studies [12] |

| Spin Trapping Agents | Detect reactive oxygen species generated in reduction reactions | DMPO (5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide) for O₂•⻠detection [12] |

| Template Materials | Control nanocrystal size and quantum confinement effects | Supermicroporous silicas (SMPSs) for WO₃ QD synthesis [12] |

| Dopant Precursors | Modify band gaps and band edge positions through composition engineering | Ta and Sb precursors for Nb₃O₇(OH) doping [5] |

| 7-Methyloct-2-YN-1-OL | 7-Methyloct-2-yn-1-ol | |

| 3-(Bromomethyl)selenophene | 3-(Bromomethyl)selenophene|Research Chemical | 3-(Bromomethyl)selenophene is a key synthetic intermediate for research applications in organic electronics and materials science. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Band structure parameters—particularly band gap width and band edge positions—serve as fundamental determinants of photocatalytic activity. The precise engineering of these parameters through size control, doping, and surface termination enables the optimization of materials for specific photocatalytic applications. Experimental validation of band positions remains crucial, as theoretical predictions require correlation with measured photocatalytic performance. The continued development of sophisticated characterization techniques and computational methods will further enhance our ability to design photocatalysts with optimally tuned band structures for efficient solar energy conversion.

The escalating global energy demand and environmental degradation have driven intensive research into photocatalytic processes that convert solar energy into chemical fuels. Two of the most promising applications are photocatalytic water splitting for hydrogen production and carbon dioxide (CO2) reduction to valuable hydrocarbons. These processes rely on semiconductor materials that can absorb light and generate electron-hole pairs to drive redox reactions. The effectiveness of any semiconductor photocatalyst is fundamentally governed by its band alignment—the energy position of its valence band (VB) and conduction band (CB) relative to the redox potentials of the target reactions.

Photocatalysis operates on the principle that when a semiconductor absorbs photons with energy greater than its band gap, electrons are excited from the VB to the CB, leaving holes in the VB. These photogenerated charge carriers then migrate to the surface and participate in reduction and oxidation reactions. For a photocatalytic reaction to proceed spontaneously, the CB minimum must be more negative than the reduction potential of the target species, while the VB maximum must be more positive than the oxidation potential. This thermodynamic requirement forms the cornerstone of band alignment engineering in photocatalyst design [18] [19].

This technical guide examines the fundamental band alignment requirements for water splitting and CO2 reduction, explores strategies for engineering optimal band structures, and details experimental methodologies for characterizing and validating photocatalyst performance.

Fundamental Band Alignment Requirements

Thermodynamic Potentials for Key Reactions

The table below summarizes the essential redox potentials relative to the normal hydrogen electrode (NHE) at pH 0. These potentials define the minimum energy requirements for the conduction and valence bands of a photocatalyst.

Table 1: Standard Redox Potentials for Photocatalytic Reactions

| Reaction | Equation | Potential vs. NHE (V) | Band Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water Splitting (HER) | 2H⺠+ 2e⻠→ H₂ | 0 | CB more negative than 0 |

| Water Splitting (OER) | 2H₂O + 4h⺠→ O₂ + 4H⺠| +1.23 | VB more positive than +1.23 |

| CO₂ to CO | CO₂ + 2H⺠+ 2e⻠→ CO + H₂O | -0.53 | CB more negative than -0.53 |

| CO₂ to CH₄ | CO₂ + 8H⺠+ 8e⻠→ CH₄ + 2H₂O | -0.24 | CB more negative than -0.24 |

| CO₂ to HCOOH | CO₂ + 2H⺠+ 2e⻠→ HCOOH | -0.61 | CB more negative than -0.61 |

To drive the complete water splitting reaction without an external bias, a photocatalyst must possess a minimum band gap of 1.23 eV, in addition to satisfying the band edge positions outlined above. However, in practice, due to overpotentials and kinetic barriers, efficient photocatalysts typically require a band gap greater than 2.0 eV [19]. The band alignment for COâ‚‚ reduction is more complex due to the variety of possible products, each with distinct reduction potentials. The desired product dictates the precise CB energy level required [19].

Visualizing Band Alignment Requirements

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental band alignment requirements for a semiconductor material to be thermodynamically capable of driving both water splitting and CO2 reduction reactions.

Strategies for Engineering Band Alignment

Doping for Band Gap Tuning and Band Edge Shifting

Introducing foreign elements into a semiconductor lattice is a primary method for modifying its electronic structure. Doping can reduce the band gap to enhance visible light absorption and/or shift the band edge positions to achieve better alignment with redox potentials.

Table 2: Doping Strategies for Band Engineering

| Material | Dopant | Effect on Band Structure | Result on Photocatalytic Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2D Mg(OH)â‚‚ | S, N, P | Band gap reduction from 4.82 eV to 3.86 eV (S), 3.79 eV (N), and 2.69 eV (P) [20]. | Extends light absorption into the visible range. |

| 2D Mg(OH)â‚‚ | F, Cl, SOâ‚„, POâ‚„ | Shifts valence band lower than Oâ‚‚/Hâ‚‚O oxidation potential [20]. | Renders band structure appropriate for water splitting. |

| Nb₃O₇(OH) | Ta, Sb | Band gap reduction from 1.7 eV to 1.266 eV (Ta) and 1.203 eV (Sb), with CB and VB relocation [21]. | Enhances visible-light activity and charge carrier mobility. |

The effectiveness of doping stems from the introduction of new energy levels within the band gap or the modification of the density of states of the constituent elements. For instance, in Mg(OH)â‚‚, anion doping is particularly effective because the VB maximum is primarily composed of O 2p orbitals. Replacing oxygen with elements like nitrogen creates higher-energy N 2p states above the O 2p VB maximum, thereby reducing the band gap [20].

Heterojunction Construction for Charge Separation

Combining two or more semiconductors to form a heterojunction is a powerful strategy to not only engineer band alignment but also to significantly enhance the separation of photogenerated electrons and holes, which is critical for high quantum efficiency [22].

The two most relevant heterojunction types for photocatalysis are:

- Type-II Heterojunction: The band edges are "staggered." The CB of Semiconductor B is higher (more negative) than that of Semiconductor A, while the VB of Semiconductor A is lower (more positive) than that of Semiconductor B. This alignment creates a built-in electric field that drives electrons to Semiconductor B and holes to Semiconductor A, resulting in spatial charge separation [22].

- S-Scheme Heterojunction: This is a more recent and advanced concept. It typically combines an oxidation photocatalyst (OP) with a reduction photocatalyst (RP). The internal electric field at the interface promotes the recombination of less useful electrons in the RP's CB with holes in the OP's VB. This leaves the most powerful photogenerated electrons (in the OP's CB) and holes (in the RP's VB) to participate in surface redox reactions. This mechanism preserves stronger redox potentials than a Type-II system [23].

The following diagram illustrates the charge transfer mechanisms in these two key heterojunction types.

Experimental Protocols for Characterization and Validation

Band Gap and Band Edge Determination

Accurately determining the band gap and absolute band edge positions is crucial for validating a material's potential for a specific photocatalytic reaction.

- UV-Vis-NIR Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy (DRS): This is the standard technique for determining the optical band gap of a powdered semiconductor. The data is typically converted to Kubelka-Munk units, and the band gap (Eg) is estimated using the Tauc plot method by plotting (F(R) * hν)^n vs. hν, where n depends on the nature of the optical transition (n=1/2 for direct and n=2 for indirect band gaps) [16].

- Mott-Schottky Analysis: This electrochemical impedance technique is performed on a working electrode made from the photocatalyst material. It is the primary method for determining the flat-band potential (Efb) of a semiconductor. For n-type semiconductors, the conduction band minimum (ECB) is typically very close (about -0.1 to -0.2 V) to Efb. For p-type semiconductors, the valence band maximum (EVB) is similarly close to Efb. The band edges can be calculated using the relationship: EVB = ECB + Eg [19].

- X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): A combined XPS and UV-Vis method can be used to determine the absolute band edge positions. The valence band spectrum from XPS provides the energy difference between the VB maximum and the Fermi level (EVB - EF). The Fermi level can be referenced using a known standard (like Au 4f). The conduction band minimum can then be calculated as ECB = EVB + E_g [20].

Photocatalytic Performance Testing

Standardized testing protocols are essential for reliably comparing the performance of different photocatalysts.

Water Splitting Test (Hâ‚‚ Evolution):

- Setup: A top-irradiation or inner-irradiation reaction vessel connected to a closed-gas circulation system.

- Procedure: Disperse 50-100 mg of photocatalyst powder in an aqueous solution (100 mL) containing a sacrificial electron donor (e.g., 10 vol% methanol or 0.1 M Na₂S/0.1 M Na₂SO₃). Evacuate the system to remove dissolved air.

- Irradiation: Use a Xe lamp (typically 300-500 W) with appropriate cut-off filters to control the wavelength (e.g., λ > 420 nm for visible light). Circulate cooling water to maintain ambient temperature.

- Analysis: The evolved gases (Hâ‚‚ and Oâ‚‚ for overall water splitting, or only Hâ‚‚ with sacrificial agents) are analyzed periodically by online gas chromatography (GC) equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD) [18] [16].

COâ‚‚ Reduction Test:

- Setup: Similar to the water splitting setup, but with provisions for introducing COâ‚‚.

- Procedure: Disperse the photocatalyst in ultra-pure water in the reactor. Purity the water and reactor by repeated evacuation and purging with high-purity COâ‚‚. Finally, introduce COâ‚‚ gas to a set pressure (typically 1 atm).

- Irradiation: Use a Xe lamp with desired cut-off filters.

- Analysis: Analyze the gas phase (for products like CO, CH₄, C₂H₄) using GC-TCD/GC-FID. Analyze the liquid phase (for products like HCOOH, CH₃OH) using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [19] [23].

- Control: Conduct an isotopic experiment using ¹³CO₂ to confirm the carbon source of the products is CO₂ and not residual carbon on the catalyst.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Photocatalysis Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) | Crystalline, porous organic polymer semiconductors for H₂ evolution, CO₂ reduction, and H₂O₂ production [18]. | Pre-designable structure, high surface area, π-conjugated system, functional modulability. |

| Earth-Abundant Light Absorbers (e.g., BiVO₄, Cu₂O, α-Fe₂O₃, g-C₃N₄) | Low-cost, scalable alternatives to rare/toxic semiconductors (e.g., III-V groups) for photoelectrodes [19]. | Suitable band gaps for visible light, composed of abundant elements, variable stability. |

| Sacrificial Agents (e.g., Triethanolamine (TEOA), Methanol, Na₂S/Na₂SO₃) | Electron donors (hole scavengers) used in half-reaction tests to evaluate the reduction capability of a photocatalyst [18]. | Consumes photogenerated holes, thereby suppressing charge recombination and backward reactions. |

| Co-catalysts (e.g., Pt, Ni, CoOâ‚“, NiOOH) | Nanoparticles loaded onto the photocatalyst surface to act as active sites for surface redox reactions [19]. | Lowers activation energy, enhances reaction kinetics, and in some cases aids charge separation. |

| Non-Noble Metal Cocatalysts | Sustainable and cost-effective alternative to Pt for hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) [19]. | Based on Fe, Co, Ni, Mo, W, and their compounds (sulfides, phosphides). |

| 10-Hydroxydec-6-en-2-one | 10-Hydroxydec-6-en-2-one, CAS:61448-23-5, MF:C10H18O2, MW:170.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 5,5-Dichloro-1,3-dioxane | 5,5-Dichloro-1,3-dioxane | 5,5-Dichloro-1,3-dioxane is a chemical building block for antimicrobial and synthetic chemistry research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

The precise engineering of band alignment is a fundamental and non-negotiable aspect of developing efficient photocatalysts for water splitting and COâ‚‚ reduction. While the thermodynamic principles are well-established, the challenge lies in designing materials that simultaneously satisfy band edge requirements, possess a suitable narrow band gap for visible light absorption, and exhibit high charge separation efficiency and long-term stability. Strategies such as doping and heterojunction construction, particularly advanced concepts like S-scheme heterojunctions, provide a robust pathway to tailor the electronic structure of semiconductors. Continued advancement in precise synthetic control, coupled with sophisticated characterization techniques and theoretical modeling, is essential to bridge the gap between laboratory proof-of-concept and the large-scale, practical application of solar-driven fuel production.

Comparative Analysis of Band Structures in Common Photocatalysts (e.g., TiO2, g-C3N4)

The efficacy of semiconductor-based photocatalysis is fundamentally governed by the electronic band structure of the catalytic material. The energy difference between the valence band (VB) and the conduction band (CB), known as the band gap, along with the absolute positions of these bands, determines a photocatalyst's capacity to harvest light and drive redox reactions. This analysis provides a detailed comparison of the band structures of two predominant photocatalysts—titanium dioxide (TiO₂) and graphitic carbon nitride (g-C₃N₄)—framed within the critical context of how valence and conduction band energetics dictate photocatalytic activity and mechanisms.

Fundamental Band Structure Properties

The photocatalytic process initiates when a photon with energy greater than or equal to the semiconductor's band gap is absorbed, promoting an electron from the VB to the CB. This creates a positively charged hole in the VB. The subsequent separation and migration of these charge carriers to the surface facilitate reduction and oxidation reactions, respectively [1]. The band edge positions relative to the redox potentials of target reactions are therefore paramount.

Table 1: Fundamental Band Structure Properties of Common Photocatalysts

| Photocatalyst | Crystal Structure | Band Gap (eV) | Valence Band Position (eV vs. NHE) | Conduction Band Position (eV vs. NHE) | Primary Optical Transition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiO₂ (Anatase) | Tetragonal | ~3.20 [24] | ~3.00 [25] | ~-0.20 [25] | O 2p → Ti 3d |

| g-C₃N₄ | Hexagonal (Graphitic) | ~2.70 [26] [27] | +1.60 [26] | -1.10 [26] | π → π* (and n → π*) |

The inherent wide band gap of anatase TiO₂ (~3.2 eV) restricts its light absorption to the ultraviolet (UV) region, which constitutes only about 5% of the solar spectrum [24]. In contrast, g-C₃N₄, with a band gap of approximately 2.7 eV, possesses a inherent visible light response [26] [27]. The VB and CB positions of g-C₃N₄ are suitably straddled for water splitting and the generation of reactive oxygen species, making it a compelling visible-light-driven photocatalyst.

Band Gap Engineering and Modulation Strategies

A primary focus of contemporary research is the engineering of photocatalyst band structures to enhance visible light absorption and improve charge separation efficiency.

Doping and Defect Engineering in TiOâ‚‚

Elemental Doping: Introducing foreign elements into the TiOâ‚‚ lattice is a prevalent method for band gap modulation.

- Cationic Doping (Metals): Doping with metals like Al³⺠can induce oxygen vacancies and alter phase stability. For instance, Al³âº/Sâ¶âº co-doping in TiOâ‚‚ has been shown to reduce the band gap from 3.23 eV to as low as 1.98 eV, significantly enhancing visible light absorption. This co-doping facilitates a phase transition from anatase to rutile, further influencing the electronic structure [28].

- Anionic Doping (Non-Metals): Nitrogen (N) is one of the most studied anionic dopants for TiOâ‚‚. N-doping can occur via substitutional or interstitial modes, leading to the formation of localized N 2p states above the O 2p VB maximum. This effectively narrows the band gap and extends absorption into the visible region up to 550 nm [25]. Other non-metals like sulfur (S) have also been employed, with their larger ionic radii creating distinct lattice distortions and band gap modifications [28].

Table 2: Band Gap Modulation in TiOâ‚‚ via Doping

| Doping Strategy | Example | Resulting Band Gap (eV) | Key Structural/Optical Changes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Co-doping | Al³âº/Sâ¶âº co-doped TiOâ‚‚ | 1.98 - 3.23 (tunable) [28] | Increased rutile phase content; redshift in absorption; introduction of oxygen vacancies. |

| Non-Metal Doping | N-doped TiOâ‚‚ (N-TiOâ‚‚) | ~2.50 - 3.00 (tunable) [25] | Absorption edge extended to ~500-550 nm; formation of N 2p states above O 2p VB. |

| Single Metal Doping | Cu-doped TiOâ‚‚ | 2.28 - 3.09 (tunable) [24] | Lattice deformation; formation of oxygen vacancies and impurity states. |

Morphological and Quantum Effects: Controlling the nanoscale dimensions of photocatalysts can also tune the band structure via quantum confinement effects. For example, the conduction band edge of WO₃ quantum dots was experimentally shown to upshift as the particle size decreased below 2 nm, enabling photocatalytic reductions that are not feasible with bulk WO₃ [12]. Similar principles apply to TiO₂, where a high surface area promotes quantum confinement and enhances surface reaction kinetics [24].

Structural and Electronic Tuning of g-C₃N₄

Pore Structure Engineering: Modifying the porosity of g-C₃N₄ is an effective strategy to increase its specific surface area, providing more active sites and facilitating charge/mass transport. Synthesis methods include:

- Hard-Template Method: Yields uniform, tunable pores but requires additional steps for template removal [27].

- Soft-Template Method: Templates decompose during thermal condensation, simplifying the process but offering less control over pore regularity [27].

- Template-Free Method: The simplest approach, involving direct thermal condensation of nitrogen-rich precursors or exfoliation of bulk g-C₃N₄, though with limited improvement in specific surface area [27].

Elemental Doping and Functionalization: Doping with elements like potassium (Kâº) can redshift the Ï€-Ï€* electronic transitions in g-C₃Nâ‚„ by enhancing the planar delocalization of Ï€ electrons. Furthermore, creating a gradient band energy structure through controlled K⺠doping can significantly improve the separation efficiency of photogenerated charge carriers and their mobility to the surface [29]. Activating the inactive n-Ï€* electronic transitions by breaking the symmetrical planar structure of the heptazine units also contributes to enhanced visible light response [29].

Experimental Protocols for Band Structure Analysis

The following section outlines standard methodologies for synthesizing and characterizing the band structure of modified photocatalysts.

Objective: To prepare Al and S co-doped TiOâ‚‚ nanoparticles with enhanced visible-light photocatalytic activity.

Protocol:

- Precursor Preparation: Dissolve 2 g of titanium(III) chloride hexahydrate (TiCl₃·6H₂O) in 50 mL of deionized water and stir for 30 minutes. In a separate beaker, dissolve 0.5 g of sodium hydroxide (NaOH) in 20 mL of deionized water.

- Mixing: Add the NaOH solution dropwise to the TiCl₃ solution under magnetic stirring. Allow the mixture to stand for 10 minutes before resuming vigorous stirring for 50 minutes to ensure homogeneity.

- Hydrothermal Reaction: Transfer the resulting solution into a 100 mL Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave. Heat the autoclave in an oven at 150°C for 24 hours.

- Washing and Drying: After reaction, cool the autoclave to room temperature. Centrifuge the resultant solution and wash the precipitate repeatedly with deionized water until the supernatant reaches pH 7. Dry the obtained pure TiO₂ nanoparticles at 60°C for 24 hours.

- Doping Introduction: For Al/S co-doping, mix Aluminum nitrate nonahydrate (Al(NO₃)₃·9H₂O) and sodium sulfate (Na₂SO₄) with TiCl₃·6H₂O in deionized water. Adjust the pH to ~9 using ammonium hydroxide to facilitate uniform precipitation.

- Calcination: Dry the gel at 100°C for 12 hours, then calcine it at 500°C for 3 hours in air to achieve crystallinity and dopant incorporation. Use a controlled heating rate of 5°C/min.

Objective: To incorporate nitrogen into the TiOâ‚‚ lattice to create a visible-light-responsive photocatalyst.

Protocol:

- Dry Methods (Sputtering): Utilize a high-vacuum chamber for sputtering a titanium target in an atmosphere of N₂/Ar or NH₃. Alternatively, oxidize pre-formed TiN at elevated temperatures.

- Wet Methods: Employ sol-gel, hydrothermal, or solvothermal processes using nitrogen-containing precursors such as urea or thiourea.

- Post-Treatment: Anneal the as-prepared materials in an ammonia or nitrogen atmosphere at temperatures typically ranging from 400°C to 600°C to facilitate nitrogen incorporation.

Determination of Band Gap and Band Edge Positions

Band Gap via UV-Vis Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy (DRS):

- Measure the diffuse reflectance spectrum of the powdered photocatalyst.

- Convert the reflectance data to the Kubelka-Munk function, F(R).

- Plot (F(R)*hν)⿠vs. hν (photon energy), where n = 1/2 for direct band gaps and n = 2 for indirect band gaps.

- Extrapolate the linear region of the plot to (F(R)*hν)⿠= 0 to determine the band gap energy [24].

Conduction Band Edge (CBE) Estimation via Surface Complexation:

- Form a surface complex between the semiconductor (e.g., WO₃ quantum dots) and an organic molecule with a known HOMO level, such as phenol.

- Measure the charge-transfer excitation energy (E_CT) from the absorption spectrum of the complex.

- Calculate the CBE using the equation:

E_CBE = E_HOMO(phenol) - E_CT[12]. The HOMO of phenol can be determined experimentally by techniques like photoemission yield spectroscopy in air (PYSA).

Charge Transfer Mechanisms and Heterojunction Design

Engineering heterojunctions between different semiconductors is a powerful strategy to spatially separate photogenerated electron-hole pairs, thereby inhibiting their recombination.

This diagram illustrates the charge transfer pathway in a Type-II heterojunction, a common and effective design. In such a system, the conduction and valence bands of the two semiconductors are staggered. Under light irradiation, photogenerated electrons migrate to the semiconductor with the more positive CB, while holes migrate to the semiconductor with the more negative VB. This spatial separation significantly reduces the probability of charge carrier recombination [26]. g-C₃N₄ is frequently integrated into such heterostructures with other semiconductors, including TiO₂, to enhance its photocatalytic performance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Photocatalyst Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Titanium Precursors (e.g., TiCl₃, Ti alkoxides) | Source of Ti for constructing the TiO₂ lattice. | Sol-gel or hydrothermal synthesis of TiO₂ nanoparticles [28] [25]. |

| Nitrogen-Rich Precursors (e.g., Urea, Melamine, Thiourea) | Source of C and N for thermal condensation into g-C₃N₄. | Thermal synthesis of bulk g-C₃N₄ [26] [27]. |

| Dopant Precursors (e.g., Al(NO₃)₃, NH₄OH, Thiourea) | Introduce foreign elements (Al, N, S) into host lattice to modify band structure. | Metal/non-metal doping of TiO₂ or g-C₃N₄ for band gap narrowing [28] [25]. |

| Structural Templates (e.g., SiO₂ nanoparticles, surfactants) | Create controlled porosity and high surface area during synthesis. | Hard- or soft-template synthesis of mesoporous g-C₃N₄ [27]. |

| Sacrificial Reagents (e.g., Methanol, Triethanolamine) | Electron donors that consume photogenerated holes, thereby enhancing reduction efficiency. | Photocatalytic hydrogen evolution experiments [29]. |

| Spin Trapping Agents (e.g., DMPO - 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide) | Trap short-lived radical intermediates (e.g., •OOH) for detection by Electron Spin Resonance (ESR). | Mechanistic studies to confirm reactive oxygen species generation [12]. |

| 3-Butyl-1,3-oxazinan-2-one | 3-Butyl-1,3-oxazinan-2-one | 3-Butyl-1,3-oxazinan-2-one (C8H15NO2) is a versatile oxazinanone scaffold for antimicrobial and anticancer research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| 3-Methoxy-2,4-dimethylfuran | 3-Methoxy-2,4-dimethylfuran|High-Purity Reference Standard | 3-Methoxy-2,4-dimethylfuran: A high-purity chemical for research use only (RUO). Explore its applications in organic synthesis and fragrance development. Not for human or veterinary use. |

The strategic engineering of band structures in TiO₂ and g-C₃N₄ is pivotal for advancing photocatalytic technology. While TiO₂ requires significant modification through doping and nanostructuring to function under visible light, g-C₃N₄ offers an inherently visible-light-active platform that can be further optimized. The choice between these materials, or their combination in heterostructures, depends on the specific redox potentials required for the target application. Future research will continue to leverage detailed band structure analysis and advanced material design to develop next-generation photocatalysts with optimized light absorption and charge separation capabilities.

Band Engineering in Action: Strategies to Tailor Materials for Enhanced Performance

Band gap engineering represents a cornerstone of modern materials science, pivotal for enhancing the efficiency of photocatalytic reactions. The strategic narrowing of a semiconductor's band gap allows for greater utilization of the solar spectrum, particularly visible light, which is a key determinant in the efficacy of photoelectrochemical cells and environmental remediation applications. This technical guide delves into the deliberate manipulation of valence and conduction band positions through elemental doping, examining two prominent material systems: Ta/Sb-doped Nb3O7(OH) and Cu-modified TiO2. By synthesizing insights from recent computational and experimental studies, this review provides a structured framework for researchers aiming to design advanced photocatalytic materials with tailored electronic structures for specific applications in energy and drug development contexts.

Theoretical Foundations: Band Structure and Photocatalysis

The Role of Valence and Conduction Bands in Photocatalysis

In semiconductor photocatalysis, the energy difference between the valence band (VB) and conduction band (CB) - the band gap - dictates the minimum photon energy required to excite an electron, creating reactive electron-hole pairs. The positions of these bands relative to redox potentials further determines the thermodynamic feasibility of catalytic reactions. For water splitting, the CB must be more negative than the Hâº/Hâ‚‚ reduction potential (0 V vs. NHE), while the VB must be more positive than the Hâ‚‚O/Oâ‚‚ oxidation potential (1.23 V vs. NHE). Doping modulates these band positions through introduced states, lattice strain, and altered orbital hybridization, enabling both improved light absorption and maintained redox power [21] [30].

Ta/Sb-Doped Nb3O7(OH): A Computational Perspective

Material System and Doping Strategy

Niobium oxide hydroxide (Nb3O7(OH)) has emerged as an attractive photocatalytic substrate due to its inherent chemical stability, suitable band positions, and abundant active sites. Recent computational studies have systematically investigated the band structure engineering of this material through doping with tantalum (Ta) and antimony (Sb), which serve as strategic isovalent and aliovalent substitutes, respectively, for niobium atoms [21].

Computational Methodology and Protocols

First-Principles Calculations: The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) was employed for structural optimization of all systems. Electronic and optical properties were calculated using the Trans-Blaha modified Becke-Johnson approximation (TB-mBJ), recognized for providing accurate band gap predictions. For the doped systems containing Ta and Sb, spin-orbit coupling was incorporated to properly account for the f and d orbitals, respectively [21].

Band Structure Analysis: The band structures, density of states, and orbital contributions were calculated using the WIEN2k code. Optical properties including the dielectric function, reflectivity, and electron energy loss function were determined with the OPTIC program [21].

Band Gap Narrowing and Electronic Structure Modifications

Doping induces significant relocation of both valence band maximum and conduction band minimum positions, effectively reducing the band gap from 1.7 eV in pristine Nb3O7(OH) to 1.266 eV with Ta doping and 1.203 eV with Sb doping. This substantial narrowing represents a reduction of approximately 25-30%, shifting the optical absorption threshold into the visible light region [21].

Table 1: Band Gap Modification in Doped Nb3O7(OH)

| Material System | Band Gap (eV) | Reduction vs. Pristine | Band Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pristine Nb3O7(OH) | 1.700 | Baseline | Direct |

| Ta-doped Nb3O7(OH) | 1.266 | 25.5% | Direct |

| Sb-doped Nb3O7(OH) | 1.203 | 29.2% | Direct |

Partial density of states analysis reveals that O p orbitals dominate the valence band, while Nb d orbitals primarily constitute the conduction band in the pristine material. Upon doping, Ta d and Sb d orbitals contribute significantly to the conduction band, modifying the electronic density and enabling lower energy transitions [21].

Transport and Optical Properties

The calculated effective mass and electrical conductivity indicate enhanced charge carrier mobility in doped systems. This improvement facilitates better separation and transport of photogenerated carriers, crucial for photocatalytic efficiency. Optical characterization demonstrates a clear red-shift in absorption edges for doped systems, confirming their enhanced visible-light responsiveness [21].

Cu-Doped TiO2: Experimental Approaches and Modifications

Material System and Synthesis Protocols

Titanium dioxide (TiOâ‚‚), particularly in the anatase phase, has been extensively studied for photocatalytic applications despite its inherent wide band gap (~3.2 eV) that limits visible light absorption. Copper doping has emerged as a prominent strategy to address this limitation through various synthesis approaches [31].

Sol-Gel Dip-Coating Synthesis: A representative experimental protocol involves dissolving tetraethyl-orthotitanate in a solution of ethanol, water, and nitric acid, followed by stirring for 1 hour and aging for 24 hours. Cu-doping is achieved by adding copper salts (e.g., Cu(NO₃)₂) to the precursor solution with concentrations typically ranging from 2-10 mol%. Film deposition is performed on glass substrates using a dip-coater at controlled withdrawal speeds (e.g., 1 mm/s), with subsequent thermal treatment to achieve crystallinity [31].

Hydrothermal Synthesis: For nanoparticle synthesis, Ti precursors such as TiCl₃·6H₂O are mixed with deionized water, followed by addition of NaOH solution under stirring. The resulting solution is transferred to a Teflon-lined autoclave and reacted at 150°C for 24 hours. Copper doping is introduced by including copper salts in the initial mixture [28].

Structural and Optical Characterization

X-ray diffraction patterns of Cu-doped TiOâ‚‚ films confirm maintenance of the anatase phase at lower Cu concentrations (<8 mol%), with no separate Cu oxide phases detected, suggesting incorporation into the TiOâ‚‚ lattice or formation of clusters below XRD detection limits. Rietveld refinements reveal lattice parameter changes indicating successful doping [31].

Optical analysis through UV-Vis spectroscopy shows significant modulation of the absorption edge. The band gap reduction follows a quantifiable relationship with Cu concentration, though the exact values depend on synthesis parameters and dopant distribution.

Table 2: Band Gap Engineering in Doped TiOâ‚‚ Systems

| Material System | Band Gap (eV) | Synthesis Method | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pure TiOâ‚‚ | 3.122 | Sol-gel dip-coating | Baseline [24] |

| 5 mol% Cu-doped TiO₂ (600°C) | 2.510 | Sol-gel | 19.6% reduction [24] |

| 5 mol% Cu-doped TiO₂ (700°C) | 2.430 | Sol-gel | 22.2% reduction [24] |

| Al/S co-doped TiOâ‚‚ (X4) | 1.980 | Hydrothermal | 38.7% reduction [28] |

| B-doped A-TiOâ‚‚/R-TiOâ‚‚ | Tunable | Calcination | Z-scheme heterojunction [32] |

Photocatalytic Performance Assessment

The photocatalytic activity of Cu-doped TiOâ‚‚ thin films is typically evaluated through degradation of organic dyes such as methylene blue (MB) under UV or visible light irradiation. Studies indicate that Cu-doping does not universally enhance photocatalytic activity; excessive Cu can form recombination centers (CuO, Cuâ‚‚O phases) that promote electron-hole recombination, thereby reducing quantum efficiency. The optimal dopant concentration balances band gap narrowing with minimized recombination [31].

Comparative Analysis of Doping Strategies

Mechanisms of Band Gap Narrowing

The two material systems exemplify distinct mechanisms of band gap engineering:

In Ta/Sb-doped Nb3O7(OH), doping primarily shifts both valence and conduction band positions, maintaining direct band behavior while reducing the transition energy. The Fermi level relocation facilitates electron excitation at lower energies [21].

In Cu-doped TiOâ‚‚, the band gap reduction occurs through introduction of intra-band gap states and lattice deformation, creating impurity levels within the forbidden gap that enable visible light absorption. The formation of oxygen vacancies further contributes to enhanced visible light responsiveness [31] [28].

Charge Carrier Dynamics

Both strategies aim to improve charge separation and mobility. Ta/Sb doping in Nb3O7(OH) demonstrates enhanced electrical conductivity and reduced effective mass, promoting carrier transport [21]. For Cu-doped TiOâ‚‚, the metal centers can act as both electron traps and recombination sites, depending on concentration and distribution, highlighting the importance of optimized doping parameters [31].

Advanced Engineering Strategies

Heterostructure Design

Beyond single-element doping, heterostructure engineering offers enhanced band gap control. The construction of type-II heterojunctions, such as Câ‚‚N/MSeâ‚‚ (M = Mo, W) interfaces, creates built-in electric fields that efficiently separate photogenerated carriers while maintaining strong redox potentials [33]. Similarly, boron-doped anatase/rutile TiOâ‚‚ phase junctions form direct Z-scheme heterostructures that synergistically optimize charge separation and visible light absorption [32].

Machine Learning Approaches

Recent advances incorporate machine learning for band gap prediction in doped TiO₂ systems. Gaussian process regression models utilizing lattice parameters and surface area as descriptors achieve exceptional accuracy (R² = 99.99%) in predicting band gaps, enabling high-throughput screening of doping strategies without resource-intensive computations [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Band Gap Engineering Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Tetraethyl-orthotitanate | TiOâ‚‚ precursor | Sol-gel synthesis of TiOâ‚‚ thin films [31] |

| Niobium oxide hydroxide | Photocatalyst substrate | Ta/Sb doping studies [21] |

| Tantalum pentachloride | Dopant source | Ta doping of Nb3O7(OH) [21] |

| Antimony trichloride | Dopant source | Sb doping of Nb3O7(OH) [21] |

| Copper nitrate | Dopant source | Cu doping of TiOâ‚‚ [31] |

| Boric acid | Dopant source | B doping of TiOâ‚‚ for phase junction control [32] |

| Aluminum chloride | Dopant source | Al doping of TiOâ‚‚ for co-doping studies [28] |

| Thiourea | Sulfur source | S doping of TiOâ‚‚ for co-doping studies [28] |

| Methylene blue | Photocatalytic activity probe | Degradation studies [31] |

| Rhodamine B | Photocatalytic activity probe | Degradation studies [34] |

| GTP gamma-4-azidoanilide | GTP gamma-4-azidoanilide, CAS:60869-76-3, MF:C16H20N9O13P3, MW:639.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Oxetane;heptadecahydrate | Oxetane;heptadecahydrate, CAS:60734-82-9, MF:C3H40O18, MW:364.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The strategic doping of semiconductor materials represents a powerful approach for band gap engineering and enhanced photocatalytic performance. Ta/Sb-doped Nb3O7(OH) demonstrates precise band structure control through computational design, achieving significant band gap reductions to approximately 1.2-1.3 eV while maintaining favorable charge transport properties. Cu-doped TiOâ‚‚ illustrates the complexities of experimental implementation, where optimal doping concentrations balance visible light absorption against potential recombination losses. Emerging strategies including heterostructure design and machine learning prediction offer accelerated development pathways for next-generation photocatalytic materials. These approaches enable researchers to systematically tailor valence and conduction band positions for specific applications in environmental remediation, energy conversion, and pharmaceutical development contexts.

The imperative to address global energy shortages and environmental pollution has propelled photocatalysis to the forefront of sustainable technology research. This technology harnesses solar energy to drive chemical reactions for hydrogen production, CO2 reduction, and pollutant degradation [35]. The efficacy of any photocatalytic system fundamentally depends on the semiconductor's ability to absorb light and generate charge carriers—electrons and holes—that migrate to the surface to initiate redox reactions. A paramount challenge, however, lies in the innate tendency of these photogenerated electrons and holes to recombine, dissipating their energy as heat and drastically reducing photocatalytic efficiency [35] [36].

Single semiconductor materials, such as titanium dioxide (TiO2) and zinc oxide (ZnO), often possess inappropriate bandgap energies or rapid charge recombination rates, limiting their practical application [37] [35]. Heterojunction construction represents a powerful strategy to overcome these limitations. By forming a controlled interface between two semiconductors with distinct electronic structures, it is possible to engineer a built-in electric field that directs the spatial separation of electrons and holes, thereby inhibiting recombination [22]. This interface engineering is fundamentally governed by the alignment of valence and conduction bands at the junction, which dictates the pathway and efficiency of charge transfer. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of two exemplary heterojunction systems—Cu2O/TiO2 and ZnS-ZnO—detailing their construction, charge transfer mechanisms, and performance in key photocatalytic applications.

Theoretical Foundations of Heterojunctions

Band Alignment Types and Charge Transfer Mechanisms

The photocatalytic performance of a heterojunction is predominantly determined by the type of band alignment at the interface, which governs the direction of charge carrier migration.

Type-II Heterojunction (Staggered Alignment): In this classic configuration, the conduction band (CB) and valence band (VB) of one semiconductor are both staggered at higher energies than those of the other. Upon light irradiation, photogenerated electrons tend to migrate to the lower-lying CB, while holes transfer to the higher-lying VB. This results in the spatial separation of charge carriers across the two materials [35] [38]. While this effectively suppresses recombination, a significant trade-off exists: the electrons and holes accumulate in energy states with reduced redox potentials, which can thermodynamically weaken their driving force for surface reactions [22] [36].