UV-Vis Spectroscopy for d-d Transition Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Octahedral Complex Characterization in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the theory, application, and validation of UV-Vis spectroscopy for analyzing d-d transitions in octahedral transition metal complexes.

UV-Vis Spectroscopy for d-d Transition Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Octahedral Complex Characterization in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the theory, application, and validation of UV-Vis spectroscopy for analyzing d-d transitions in octahedral transition metal complexes. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it bridges foundational concepts—such as the origin of color and ligand field theory—with practical methodologies for complex characterization, including recent advances in metal-azo dye complexes. The scope extends to crucial troubleshooting protocols for common experimental pitfalls and a comparative analysis of validation techniques to ensure data accuracy and reliability. By integrating foundational knowledge with applied and regulatory considerations, this resource aims to enhance the use of UV-Vis spectroscopy in the development of metal-based drugs and diagnostic agents.

Unlocking Color: The Foundation of d-d Transitions and Electronic Spectroscopy in Octahedral Complexes

Fundamental Principles of Electronic Transitions

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy is an analytical technique that measures the absorption of discrete wavelengths of ultraviolet or visible light by a sample. When applied to coordination compounds, this technique provides profound insights into their electronic structure, particularly for transition metal complexes with partially filled d-orbitals [1].

Types of Electronic Transitions in Coordination Compounds

Coordination compounds exhibit several types of electronic transitions, each with distinct characteristics and spectral signatures:

d-d Transitions: These occur between molecular orbitals that are predominantly metal-based in character—specifically, between the split d-orbitals in a transition metal complex. In octahedral complexes, these transitions happen between the t₂g and e_g orbitals across the crystal field splitting energy (Δ) [2]. These transitions are only possible in metal ions with d¹ to d⁹ configurations and typically appear as relatively weak bands in absorption spectra with molar absorptivity (ε) < 1,000 M⁻¹cm⁻¹ [2].

Charge Transfer (CT) Transitions: These involve electron movement between molecular orbitals with predominantly metal character and those with predominantly ligand character. Two subtypes exist:

- Ligand to Metal Charge Transfer (LMCT): Electron excitation from ligand-based orbitals to metal-based orbitals, occurring when metals are bound to π-donor ligands [2].

- Metal to Ligand Charge Transfer (MLCT): Electron excitation from metal-based orbitals to ligand-based orbitals, occurring with π-acceptor ligands [2]. Charge transfer transitions produce intense absorption bands with ε > 1,000 M⁻¹cm⁻¹ [2].

Table 1: Characteristics of Electronic Transitions in Coordination Compounds

| Transition Type | Origin | Spectral Intensity | Molar Absorptivity (ε) | Common Observing Complexes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| d-d | Metal-centered orbitals | Weak bands | Typically < 1,000 M⁻¹cm⁻¹ | Octahedral complexes of Cr³⁺, Co²⁺, Ni²⁺ |

| LMCT | Ligand to metal orbitals | Very intense bands | > 1,000 M⁻¹cm⁻¹ | Complexes with π-donor ligands (e.g., O²⁻, Cl⁻) |

| MLCT | Metal to ligand orbitals | Very intense bands | > 1,000 M⁻¹cm⁻¹ | Complexes with π-acceptor ligands (e.g., CO, CN⁻, bipyridine) |

Theoretical Framework for d-d Transitions

In transition metal complexes, the five degenerate d-orbitals split into different energy levels depending on the geometry and ligand field. In octahedral complexes, the d-orbitals split into two sets: the higher energy e_g orbitals (dx²-y² and dz²) and the lower energy t₂g orbitals (dxy, dxz, dyz) [3]. The energy separation between these sets is the crystal field splitting parameter (Δo) [3].

The color observed in transition metal complexes originates from the excitation of d-electrons from lower to higher energy levels. The specific wavelength required for this excitation corresponds to the energy difference between the orbitals, and the complementary color to the absorbed wavelength is emitted when the electron returns to the ground state [3].

Selection Rules and Spectral Characteristics

The intensity of electronic transitions is governed by quantum mechanical selection rules that determine the probability of specific electronic excitations.

Fundamental Selection Rules

Spin Selection Rule (ΔS = 0): Forbidden are transitions between states with different total spin quantum numbers. This rule prohibits transitions that change the spin multiplicity of the complex [4].

Laporte Selection Rule: In centrosymmetric molecules (those with an inversion center, such as octahedral complexes), transitions between orbitals of the same parity are forbidden. This specifically prohibits g→g and u→u transitions, making d-d transitions (g→g) formally Laporte-forbidden in perfect octahedral symmetry [4].

Table 2: Selection Rules Governing Electronic Transitions

| Selection Rule | Mathematical Formulation | Effect on d-d Transitions | Example of Forbidden Transition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spin Rule | ΔS = 0 | Forbids transitions between different spin states | Singlet to triplet transitions |

| Laporte Rule | g u (allowed) | Forbids d-d transitions in centrosymmetric complexes | t₂g → e_g in octahedral complexes |

Relaxation of Selection Rules

Despite these restrictions, d-d transitions are readily observed in octahedral complexes due to mechanisms that relax the selection rules:

Vibronic Coupling: Molecular vibrations cause temporary distortions that break the centrosymmetry of the complex, momentarily allowing formally forbidden transitions. This results in observable—but weak—d-d bands with molar absorptivities generally ≤ 100 M⁻¹cm⁻¹ [4].

Orbital Mixing: Interactions between metal d-orbitals and ligand orbitals can mix orbital characters, reducing the purely d-orbital nature of the transition [4].

Quantitative Analysis Using UV-Vis Spectroscopy

Beer-Lambert Law

UV-Vis spectrophotometers measure light absorption according to the Beer-Lambert Law [1]: A = εlc Where:

- A = Absorbance (unitless)

- ε = Molar absorptivity (M⁻¹cm⁻¹)

- l = Path length of the cuvette (cm)

- c = Concentration of the solution (M)

This relationship enables quantitative determination of analyte concentrations in solution when the molar absorptivity is known [1].

Instrumentation Components

Modern UV-Vis spectrophotometers consist of several key components [1]:

- Light Source: Typically a combination of deuterium lamp (UV region) and tungsten/halogen lamp (visible region).

- Wavelength Selector: Monochromators with diffraction gratings (typically 1200+ grooves/mm) isolate specific wavelengths.

- Sample Holder: Quartz cuvettes are essential for UV measurements as glass and plastic absorb UV light.

- Detector: Photomultiplier tubes (PMTs) or photodiodes convert transmitted light into electrical signals.

Experimental Protocols for d-d Transition Analysis

Sample Preparation Protocol

Materials Required:

- High-purity transition metal salt

- Appropriate ligand solution

- Solvent (typically water or organic solvent matching solubility)

- Quartz cuvettes (for UV measurements)

- Volumetric flasks and pipettes

Procedure:

- Prepare a stock solution of the transition metal complex at approximately 10⁻² M concentration.

- Prepare a series of dilutions (typically 10⁻³ to 10⁻⁵ M) to ensure absorbance values remain within the instrument's optimal range (A < 1).

- Transfer the sample to a quartz cuvette, ensuring the path is clear and free of bubbles.

- Prepare a reference blank containing only the solvent and ligands without the metal ion.

Instrument Calibration and Measurement

- Turn on the UV-Vis spectrophotometer and allow the lamps to warm up for 15-30 minutes.

- Set the wavelength range to encompass the expected d-d transitions (typically 400-800 nm for first-row transition metals).

- Place the reference blank in the sample holder and perform a baseline correction.

- Replace with the sample solution and initiate the scan.

- Record the absorption spectrum, noting the wavelengths of maximum absorption (λmax) for each observed band.

Data Analysis Protocol

- Identify the d-d transition bands by their characteristic weak intensity compared to possible charge-transfer bands.

- Calculate the crystal field splitting energy (Δo) for octahedral complexes using the relationship: Δo = hc/λ = 1/λ (in cm⁻¹) where λ is the wavelength of the absorption maximum.

- Calculate molar absorptivity for each band using the Beer-Lambert law.

- Compare the observed spectrum with predicted transitions based on the metal ion electronic configuration and coordination geometry.

Application in Pharmaceutical Research

UV-Vis spectroscopy serves as a critical tool in drug development, particularly in stability testing of pharmaceutical compounds containing transition metal complexes [5]. The technique allows researchers to:

- Quantify active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) containing coordination complexes

- Monitor degradation products that may alter the coordination sphere

- Assess drug stability under various environmental stressors (light, temperature, pH changes)

- Determine impurities that may coordinate with metal centers [5]

Early stability assessment using UV-Vis helps predict commercial viability of drug candidates containing metal complexes, guiding resource allocation in pharmaceutical development [5].

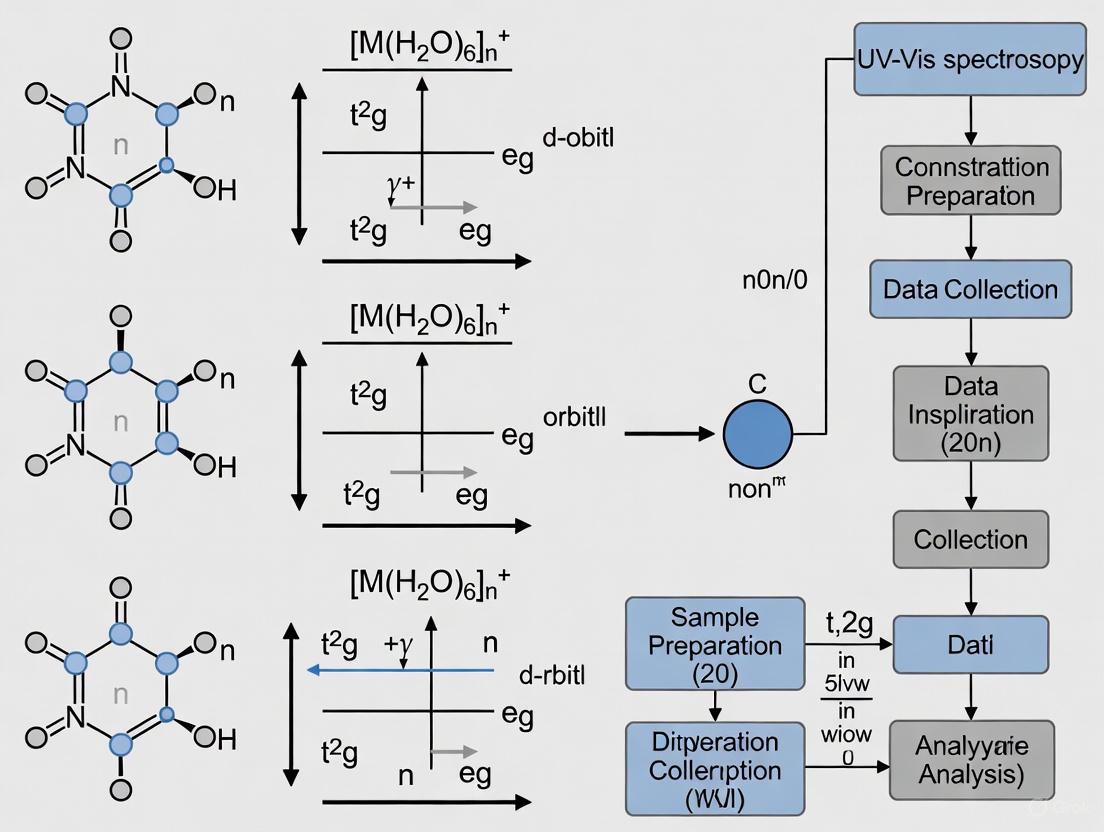

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

UV-Vis Instrument Workflow

d-Orbital Splitting and Transitions

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for d-d Transition Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Quartz Cuvettes | Sample holder for UV-Vis measurements | Essential for UV range; transparent down to 200 nm |

| Deuterium Lamp | UV light source (200-400 nm) | Requires warm-up time; limited lifetime |

| Tungsten/Halogen Lamp | Visible light source (350-800 nm) | Stable output; longer lifetime than deuterium lamps |

| Diffraction Grating | Wavelength selection in monochromator | 1200+ grooves/mm for optimal resolution |

| PMT Detector | Light detection and signal amplification | High sensitivity for low light levels |

| Standard Reference Materials | Instrument calibration and validation | Essential for quantitative accuracy |

| High-Purity Solvents | Sample preparation | Must be transparent in spectral region of interest |

| Nitrogen Purge System | Removal of oxygen for far-UV measurements | Prevents oxygen absorption below 200 nm |

Crystal Field Theory (CFT) provides a foundational model for understanding the electronic structures and resultant colors of transition-metal complexes. This theory posits that metal-ligand interactions are primarily electrostatic in nature, where electrons in the metal's d-orbitals experience repulsive forces from the electrons of the surrounding ligands [6]. The central focus of CFT is the effect of these interactions on the five valence d-orbitals, which are degenerate (of equal energy) in a free metal ion. In an octahedral complex, where a metal ion is surrounded by six ligands positioned at the corners of an octahedron, this degeneracy is removed. The negative charges from the ligands approach the metal ion directly along the Cartesian axes, leading to a characteristic splitting of the d-orbital energy levels [6]. This splitting is the origin of the crystal field stabilization energy (CFSE) and is directly responsible for the absorption of light in the visible spectrum, giving these complexes their characteristic colors [2] [6].

Theoretical Framework: d-Orbital Splitting and Electronic Transitions

The Octahedral Splitting Pattern

In an octahedral field, the five d-orbitals split into two distinct sets with different energies [6]:

- The e₉ set: This higher-energy set comprises the dx²-y² and dz² orbitals. These orbitals point directly toward the approaching ligands, resulting in greater electrostatic repulsion and higher energy.

- The t₂₉ set: This lower-energy set comprises the dxy, dxz, and dyz orbitals. These orbitals point between the axes, experiencing less repulsion from the ligands and thus stabilizing in energy.

The energy difference between these two sets is termed the crystal field splitting energy, denoted as Δₒ (where the subscript "o" stands for octahedral) [6]. The magnitude of Δₒ is not fixed; it depends critically on the identity of the metal ion (its oxidation state and position in the periodic table) and the chemical nature of the ligands. The total energy of the five d-orbitals remains unchanged by this splitting; the energy gain by the t₂₉ orbitals is exactly balanced by the energy loss of the e₉ orbitals [6].

d-d Transitions and UV-Vis Spectroscopy

The splitting of d-orbitals enables electronic transitions that can be probed using Ultraviolet-visible (UV-vis) spectroscopy. d-d transitions are electronic promotions of electrons between the metal-centered t₂₉ and e₉ molecular orbitals [2]. These transitions occur in the visible or near-UV region of the electromagnetic spectrum, which typically spans 200 to 800 nm (1.5 - 6.2 eV) [7]. When a complex absorbs light of a specific wavelength to excite an electron, the complementary color is perceived, which is the origin of color in these compounds. It is crucial to note that d-d transitions are only possible for metal ions with partially filled d-shells (d¹ to d⁹ configurations) [2]. Furthermore, these transitions are Laporte-forbidden, meaning they have relatively low transition probabilities. Consequently, d-d bands in a UV-vis spectrum appear as weak absorptions with molar absorptivity (ε) values typically less than 1,000 M⁻¹cm⁻¹ [2].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Electronic Transitions in Coordination Compounds

| Transition Type | Origin of Transition | Spectral Band Intensity (ε / M⁻¹cm⁻¹) | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| d-d Transition | Between metal-centered orbitals (t₂₉ → e₉) | Weak (ε < 1,000) | [Ti(H₂O)₆]³⁺, [Cu(NH₃)₄]²⁺ |

| Charge Transfer (CT) | Between orbitals of different molecular entities | Strong (ε > 1,000) | CrO₄²⁻ (LMCT), [Ru(bpy)₃]²⁺ (MLCT) |

Experimental Protocols for UV-Vis Analysis of d-d Transitions

UV-vis spectroscopy is a pivotal technique for quantifying d-d transitions and determining the crystal field splitting energy, Δₒ. The following protocol outlines the steps for a quantitative analysis of an octahedral transition metal complex in solution.

Instrument Calibration and Sample Preparation

- Instrument Warm-up: Power on the UV-vis spectrophotometer and allow the deuterium or tungsten lamp to stabilize for at least 15-30 minutes [7].

- System Zeroing: Fill a high-quality quartz cuvette (path length, b, typically 1 cm) with the pure solvent used for the sample (e.g., water, acetonitrile). Place this in the sample holder and run a baseline correction or "blank" measurement to zero the instrument for the solvent [7].

- Sample Solution Preparation: Accurately prepare a stock solution of the transition metal complex. The complex must be soluble and form a true solution, as suspensions of solid particles will scatter light and produce skewed data [7].

- Calibration Curve Construction (for quantitative analysis): a. Using volumetric flasks and digital pipettes for accuracy, prepare a series of at least three, but ideally five, standard solutions of known concentration from the stock solution [7]. b. The concentration range should bracket the expected concentration of your unknown sample, spaced relatively equally apart [7]. c. Measure the absorbance of each standard solution at the wavelength of maximum absorption (λmax) for the d-d transition band.

Data Acquisition and Analysis

- Sample Measurement: Introduce the sample solution of unknown concentration into a clean cuvette and acquire its full absorbance spectrum across the UV-vis range (e.g., 800-200 nm) [7].

- Determine λmax: Identify the wavelength of the peak maximum for the d-d transition band from the sample spectrum.

- Calculate Δₒ: The crystal field splitting energy is directly calculated from the absorption maximum using the equation: Δₒ = hc / λmax where h is Planck's constant, c is the speed of light, and λmax is in meters. Often, Δₒ is reported in wavenumbers (cm⁻¹), calculated as: Δₒ (cm⁻¹) = 10⁷ / λmax (nm)

- Quantitative Concentration Determination (if applicable): a. Construct a calibration curve by plotting the absorbance values of the standard solutions at λmax against their known concentrations [7]. b. The data should fit a linear trend described by the Beer-Lambert Law: A = εbc, where A is absorbance, ε is the molar absorptivity, b is the path length, and c is the concentration [7]. c. Determine the correlation coefficient (R²); an acceptable calibration has R² ≥ 0.9 [7]. A lower value may indicate human error in solution preparation or an instrument issue. d. Use the linear equation of the calibration curve to calculate the concentration of the unknown sample based on its measured absorbance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for d-d Transition Analysis

| Item Name | Function/Application | Critical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Transition Metal Salts | Source of the central metal ion for complex synthesis. | Salts like NiCl₂, CuSO₄, K₃[Fe(CN)₆]; purity >99% to avoid spectroscopic interference. |

| Ligand Solutions | To form the coordination complex with the metal ion. | e.g., 1,10-phenanthroline, ethylenediamine, cyanide salts; purity and concentration must be known. |

| Spectroscopic-Grade Solvents | To dissolve the complex for analysis without absorbing in the UV-vis range. | e.g., Acetonitrile, water (HPLC grade), hexanes; low UV cutoff. |

| Quartz Cuvettes | Holder for the sample solution during spectroscopic measurement. | Path length of 1 cm; transparent down to 200 nm (glass cuettes absorb UV light). |

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | Instrument for measuring light absorption by the sample. | Deuterium & tungsten lamps for full UV-vis range; monochromator or diode array detector [7]. |

Data Interpretation and Workflow Visualization

The following workflow diagram outlines the logical process from sample preparation to the determination of the crystal field splitting energy.

A critical step in data interpretation involves distinguishing d-d transitions from other electronic transitions. Charge transfer (CT) transitions occur between molecular orbitals that are primarily metal-based and those that are primarily ligand-based [2]. These transitions are fully allowed and consequently appear as very intense bands (ε > 1,000 M⁻¹cm⁻¹) in the UV-vis spectrum [2]. There are two types:

- Ligand-to-Metal Charge Transfer (LMCT): An electron is promoted from a ligand-based orbital to a metal-based orbital. Common with π-donor ligands.

- Metal-to-Ligand Charge Transfer (MLCT): An electron is promoted from a metal-based orbital to a ligand-based orbital. Common with π-acceptor ligands.

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between the crystal field splitting and the resulting spectroscopic transitions.

The analysis of d-d transitions through UV-vis spectroscopy, grounded in the principles of Crystal Field Theory, provides an indispensable tool for researchers investigating octahedral transition metal complexes. The precise measurement of the crystal field splitting energy, Δₒ, offers profound insights into the electronic structure of a complex, which in turn governs its magnetic properties, reactivity, and physiological function. In drug development, where metal complexes play roles as catalysts, structural elements, or active pharmaceutical ingredients, understanding these fundamental electronic properties is critical for rational design and optimization. The protocols and frameworks detailed in this application note provide a robust foundation for such advanced research and development efforts.

In the analysis of octahedral transition metal complexes using UV-Visible spectroscopy, understanding the intensity of absorption bands is paramount. The observed colors and absorption strengths are governed by fundamental quantum mechanical principles known as selection rules, which dictate the probability of electronic transitions between energy states. These rules provide the theoretical framework for interpreting spectroscopic data, particularly for the diagnostically important but often weak d-d transitions. The Laporte rule (or parity selection rule) states that in centrosymmetric molecules, electronic transitions that conserve parity are forbidden; specifically, transitions between states of the same symmetry (g → g or u → u) are electric dipole forbidden [8] [9]. This rule rigorously applies to atoms and molecules with an inversion centre, explaining why d-d transitions in perfectly octahedral complexes (where d orbitals are gerade) are formally forbidden yet appear weakly in experimental spectra.

Complementing the Laporte rule is the spin selection rule, which forbids transitions that involve a change in the spin multiplicity of the electronic state [8] [9]. According to this rule, singlet-to-singlet and triplet-to-triplet transitions are allowed, whereas singlet-to-triplet transitions are forbidden. Transitions that violate both the spin and Laporte selection rules result in exceptionally faint absorption bands, a characteristic feature of many octahedral Mn(II) and Fe(III) complexes [8]. The interplay between these rules and molecular symmetry forms the basis for predicting and interpreting the electronic spectra of coordination compounds, enabling researchers to extract valuable structural and electronic information from UV-Visible absorption measurements.

Theoretical Framework of Selection Rules

The Laporte Parity Rule

The Laporte selection rule is derived from the properties of the transition moment integral that governs the probability of an electronic transition. This integral takes the form ⟨ψₑ|H'|ψg⟩, where ψg and ψₑ are the wavefunctions of the ground and excited states respectively, and H' is the transition moment operator, typically the electric dipole operator [8]. The position operator (r) in the dipole moment operator is odd under parity (meaning it changes sign under inversion through the origin). For the transition moment integral to be non-zero, the integrand ψₑrψg must be even under parity. This condition is only satisfied when the ground and excited states have different parity (one gerade and one ungerade), making g→u or u→g transitions allowed, while g→g and u→u transitions are formally forbidden [8].

In atomic orbitals, s and d orbitals are gerade (symmetric under inversion), while p and f orbitals are ungerade (antisymmetric under inversion) [8]. Consequently, in atoms or centrosymmetric molecules such as perfect octahedral complexes, s→s, p→p, d→d, and f→f transitions are Laporte-forbidden. This rule most significantly impacts d-d transitions in transition metal complexes, which occur in the visible region and are of primary interest in coordination chemistry. It is crucial to recognize that the Laporte rule's strict application relies on the electric dipole approximation, which assumes the electromagnetic field's wavelength is much longer than the molecular dimensions. In reality, higher-order terms in the interaction Hamiltonian can permit weakly allowed transitions between states of the same parity [8].

The Spin Selection Rule

The spin selection rule dictates that electronic transitions must conserve spin angular momentum, forbidding transitions that involve a change in spin state [9]. In molecular term symbols, this translates to the requirement that ΔS = 0, meaning the spin multiplicity must remain constant during the transition. Thus, singlet-to-singlet (e.g., ¹A → ¹A) and triplet-to-triplet transitions are allowed, while singlet-to-triplet transitions (e.g., ¹A → ³A) are forbidden. This prohibition arises because the electric dipole operator does not act on electron spin, leaving the spin part of the wavefunction unchanged during the transition.

The spin rule has profound implications for transition metal complexes, particularly those with high-spin configurations. When both the Laporte and spin selection rules are violated, extinction coefficients become extremely small (ε < 1), making spectroscopic detection challenging. This combined effect explains why complexes like [Mn(H₂O)₆]²⁺ and [Fe(H₂O)₆]³⁺ exhibit such pale colors despite having partially filled d-orbitals [8] [10]. The faintness of these transitions necessitates higher sample concentrations or longer path lengths for reliable detection in experimental studies of octahedral complexes.

Mechanisms for Rule Relaxation

Although d-d transitions in octahedral complexes are formally forbidden by the Laporte rule, they are observed experimentally with weak but measurable intensities due to several mechanisms that relax these strict selection rules:

Vibronic Coupling: Asymmetric molecular vibrations temporarily disrupt the centrosymmetry of the complex, creating a vibronic state with mixed parity that provides a pathway for weakly allowed transitions [8]. This coupling between vibrational and electronic wavefunctions enables formally forbidden d-d transitions to gain intensity, typically resulting in extinction coefficients (ε) below 100 L mol⁻¹ cm⁻¹ [8].

Symmetry Lowering: Static molecular distortions from ideal Oh symmetry, whether through Jahn-Teller effects or asymmetric ligand substitution, can partially relax the Laporte rule [8]. For instance, the complex [Cr(NH₃)₅Cl]²⁺ possesses only C4v symmetry yet still maintains a centre of inversion, exhibiting weak d-d transitions (ε < 100) that demonstrate how subtle symmetry changes affect transition intensities without complete loss of centrosymmetry [8].

d-p Mixing: In non-centrosymmetric point groups such as tetrahedral (Td), the absence of an inversion centre permits mixing between d orbitals (gerade) and p orbitals (ungerade), creating molecular orbitals of mixed parity that allow stronger d-d transitions [8]. This explains why tetrahedral complexes like [CoCl₄]²⁻ exhibit significantly more intense absorptions (ε ≈ 600) compared to their octahedral analogues [8].

Table 1: Transition Types and Their Characteristic Intensities in UV-Visible Spectroscopy

| Transition Type | Selection Rule Status | Typical ε (L mol⁻¹ cm⁻¹) | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spin-forbidden, Laporte-forbidden | Violates both rules | ~0.1 | [Mn(H₂O)₆]²⁺ [10] |

| Spin-allowed, Laporte-forbidden | Violates parity rule only | 5-200 | [Co(H₂O)₆]²⁺ (ε ≈ 10) [8] |

| Spin-allowed, Laporte-allowed | Partially relaxed (vibronic) | < 100 | [Cr(NH₃)₅Cl]²⁺ [8] |

| Spin-allowed, Laporte-allowed | No inversion center | ~600 | [CoCl₄]²⁻ [8] |

| Charge Transfer | Fully allowed | > 1,000 | MLCT, LMCT [11] [2] |

Chromophores in Coordination Chemistry

d-d Transitions

d-d transitions represent electronic promotions between metal-centered orbitals that are primarily d-orbital in character, specifically between the crystal field splitting components (t₂g and e_g orbitals in octahedral geometry) [11] [2]. These transitions are only possible in complexes with partially filled d-shells (d¹ to d⁹ configurations) and provide direct information about the ligand field splitting parameter (Δₒ). In UV-visible spectra, d-d transitions typically appear as relatively weak, often broad bands with extinction coefficients generally below 1,000 L mol⁻¹ cm⁻¹, reflecting their formally forbidden nature [11] [2]. The broadening arises from vibrational fine structure and the rapid non-radiative decay pathways available to excited states in complex systems.

The energy and splitting patterns of d-d transitions serve as sensitive indicators of coordination geometry, oxidation state, and ligand identity. For a given metal ion, the spectral features change systematically with ligand field strength according to the spectrochemical series, enabling researchers to make informed assignments of complex structures. The weak intensity of these transitions, while challenging for detection, provides valuable diagnostic information about molecular symmetry and the extent to which selection rules are relaxed in real chemical systems.

Charge Transfer Transitions

In contrast to d-d transitions, charge transfer (CT) transitions involve electron promotion between molecular orbitals that are predominantly metal-centered to those that are predominantly ligand-centered, or vice versa [11] [2]. These transitions produce exceptionally intense absorption bands with extinction coefficients typically exceeding 1,000 L mol⁻¹ cm⁻¹, as they involve a substantial redistribution of electron density and are fully allowed by both Laporte and spin selection rules [11] [2]. There are two primary classes of charge transfer transitions relevant to coordination chemistry:

Ligand-to-Metal Charge Transfer (LMCT): These transitions occur when electrons are promoted from molecular orbitals primarily localized on the ligand to those primarily localized on the metal ion [11] [2]. LMCT transitions are typically observed in complexes with π-donor ligands (e.g., halides, OH⁻) and metals in high oxidation states that can readily accept electron density.

Metal-to-Ligand Charge Transfer (MLCT): These transitions involve electron promotion from metal-centered orbitals to ligand-centered orbitals [11] [2]. MLCT bands are characteristic of complexes with π-acceptor ligands (e.g., CO, CN⁻, bipyridine) and metals in low oxidation states that can readily donate electron density.

Charge transfer transitions often dominate UV-visible spectra due to their high intensities and frequently occur in the ultraviolet region, though they may extend into the visible region and impart intense colors to coordination compounds. Their diagnostic value lies in providing information about the relative energy levels of metal and ligand orbitals and the covalent character of metal-ligand bonding.

Table 2: Comparison of Electronic Transition Types in Transition Metal Complexes

| Feature | d-d Transitions | Charge Transfer Transitions |

|---|---|---|

| Orbital Origin | Metal-centered to metal-centered | Metal to ligand or ligand to metal |

| Selection Rules | Laporte-forbidden (weak) | Laporte-allowed (strong) |

| Extinction Coefficient (ε) | < 1,000 L mol⁻¹ cm⁻¹ | > 1,000 L mol⁻¹ cm⁻¹ |

| Band Width | Broad | Usually broad, sometimes sharp |

| Information Provided | Ligand field strength, geometry | Covalency, orbital energy alignment |

| Dependence on Symmetry | High (centrosymmetric complexes forbidden) | Low (always allowed) |

Experimental Protocols for d-d Transition Analysis

Sample Preparation and Measurement

The accurate characterization of d-d transitions in octahedral complexes requires careful sample preparation and spectroscopic measurement. The following protocol outlines a standardized approach for obtaining high-quality UV-visible spectra of transition metal complexes:

Solvent Selection: Choose spectroscopically transparent solvents that do not absorb in the spectral region of interest. Common choices for octahedral complexes include water, acetonitrile, and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), which have minimal absorption in the visible and near-UV regions [12]. For non-aqueous complexes, spectroscopic-grade hexane or dichloromethane may be employed. The solvent should not coordinate strongly enough to displace the ligands of interest or alter the complex geometry.

Sample Concentration Optimization: Prepare solutions with concentrations typically in the range of 1-50 mM for d-d transition analysis, as their weak extinction coefficients require higher concentrations for detection [8] [11]. For intense charge transfer bands that may appear in the same spectrum, dilute aliquots (0.01-0.1 mM) may be necessary to avoid detector saturation. Perform serial dilutions to identify optimal concentrations for different spectral regions if a single concentration yields saturated (A > 2) or weak (A < 0.1) absorptions.

Cuvette Selection and Handling: Use 1 cm pathlength quartz cuvettes for UV-visible measurements, as quartz provides transmission across the full spectral range (200-800 nm). Ensure cuvettes are meticulously cleaned with appropriate solvents and dried before use. For air-sensitive complexes, employ sealed or Schlenk-type cuvettes with septa for anaerobic measurements. Always handle cuvettes by their opaque sides to avoid fingerprints in the light path.

Spectrometer Parameters: Configure the spectrophotometer with a scan speed of 100-500 nm/min, data interval of 0.5-1 nm, and spectral bandwidth of 1-2 nm for optimal resolution of d-d bands. Perform baseline correction with a solvent-filled cuvette before sample measurement. For low-temperature studies, utilize a cryostat attachment and cool samples to 77K using liquid nitrogen to reduce vibrational broadening and enhance resolution of d-d transitions.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Once high-quality spectra are acquired, systematic analysis enables extraction of meaningful chemical information about the octahedral complex under investigation:

Baseline Correction and Normalization: Apply linear baseline correction to account for any instrumental drift or light scattering effects. Normalize spectra to concentration and pathlength using the Beer-Lambert law (A = εcl) to obtain molar absorptivity (ε) values, enabling quantitative comparison between different complexes.

Band Deconvolution: Employ Gaussian or Lorentzian fitting algorithms to deconvolute overlapping absorption bands, particularly important for d-d transitions which often appear as composite features due to Jahn-Teller distortions or low-symmetry components [8]. The number, position, and intensity of these component bands provide information about the electronic structure and symmetry of the complex.

Spectrochemical Series Determination: Identify the wavelength of maximum absorption (λmax) for each d-d transition and calculate the corresponding energy in wavenumbers (cm⁻¹ = 1/λmax). For simple octahedral complexes with a single d-d transition, this energy corresponds directly to the ligand field splitting parameter Δₒ. Plotting these energies against the position of ligands in the spectrochemical series validates assignments and may reveal deviations from ideal octahedral symmetry.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete experimental process from sample preparation to data interpretation:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful analysis of chromophores and selection rules in octahedral complexes requires specific laboratory reagents and materials. The following table details essential components of the research toolkit for these investigations:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for d-d Transition Analysis

| Item | Specification | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Transition Metal Salts | High-purity (>99%), anhydrous when required | Synthesis of octahedral complexes with defined metal centers (e.g., Co(II), Cr(III), Ni(II)) |

| Spectroscopic Solvents | UV-vis grade with low absorbance in region of interest | Sample preparation without interfering absorption bands (water, acetonitrile, DMSO) |

| Quartz Cuvettes | 1 cm pathlength, UV-vis compatible | Housing samples for spectroscopic measurement with full spectral range transmission |

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | Double-beam configuration, 200-800 nm range | Accurate measurement of absorption spectra with baseline correction capability |

| Ligand Series | Varying field strength (H₂O, NH₃, CN⁻, etc.) | Constructing spectrochemical series and investigating ligand effects on Δₒ |

| Cryostat Attachment | Liquid nitrogen cooled (77K capability) | Low-temperature measurements to reduce vibrational broadening |

| Software Packages | Spectral analysis with curve-fitting capability | Deconvolution of overlapping bands and quantitative intensity measurements |

Advanced Applications and Protocol Variations

Low-Temperature Spectroscopy

The implementation of low-temperature UV-visible spectroscopy at 77K using liquid nitrogen cryostats significantly enhances the resolution of d-d transitions by reducing thermal broadening effects [12]. This technique reveals vibrational fine structure that is obscured at room temperature and allows for more accurate determination of transition energies and intensities. The sharpening of spectral features enables better resolution of closely spaced transitions and provides evidence for Jahn-Teller distortions through the appearance of split bands that may be indistinguishable at higher temperatures. Low-temperature studies are particularly valuable for quantifying the extent of vibronic coupling by comparing band intensities between room temperature and cryogenic measurements.

Polarized Single-Crystal Spectroscopy

For complete characterization of transition dipole moments and symmetry assignments, polarized single-crystal spectroscopy provides the most definitive approach. By measuring absorption spectra with light polarized along different molecular axes within a single crystal, researchers can determine the symmetry properties of excited states and make unambiguous assignments of d-d transitions to specific electronic promotions. This technique is particularly powerful for distinguishing between transitions that are formally Laporte-forbidden but gain intensity through specific vibrational modes or symmetry lowering in the solid state. While requiring specialized instrumentation and high-quality single crystals, this approach yields the most detailed electronic structure information available from UV-visible spectroscopy.

Time-Resolved Studies

Time-resolved UV-visible spectroscopy extends static measurements to the temporal domain, enabling investigation of excited-state dynamics following d-d excitation. Using pulsed laser systems with nanosecond to femtosecond time resolution, researchers can track the relaxation pathways of electronically excited states, including energy transfer processes, intersystem crossing, and photochemical transformations. These studies provide direct insight into the fate of energy absorbed during "forbidden" transitions and help explain the relationship between transition probability and photochemical reactivity in coordination compounds. Time-resolved techniques are particularly valuable for investigating spin-forbidden transitions that may involve long-lived excited states with potential applications in photocatalysis and molecular devices.

The following diagram illustrates the symmetry relationships and transition probabilities governed by the selection rules discussed in this application note:

This application note provides a detailed framework for employing UV-Visible spectroscopy in the quantitative analysis of d-d transitions in octahedral coordination complexes. Within the context of advanced materials and drug development research, where such metal complexes are prevalent, the accurate interpretation of spectroscopic data is paramount. This guide details the core principles of the Beer-Lambert Law, defines its key parameters—absorbance and molar absorptivity—and presents standardized protocols for instrument calibration, sample preparation, and data analysis. Special emphasis is placed on the unique characteristics of d-d transitions, including their typically low intensity and the critical influence of the ligand field. The protocols and methodologies outlined herein are designed to equip researchers and scientists with the tools necessary for rigorous spectroscopic characterization, ensuring reliable and reproducible results in their investigations.

The Beer-Lambert Law

The Beer-Lambert Law (also known as Beer's Law) is the fundamental relationship that describes the attenuation of light as it passes through an absorbing substance [13]. It is an indispensable tool for the quantitative analysis of solutions in spectroscopic research. The law establishes a linear relationship between the absorbance (A) of a sample and the concentration (c) of the absorbing species, as well as the path length (l) the light travels through. The modern formulation of this law is expressed in Equation 1 [13] [14]:

A = ε * c * l (Equation 1)

In this equation, ε represents the molar absorption coefficient (also historically called molar absorptivity or molar extinction coefficient), c is the molar concentration of the analyte, and l is the path length of the light through the sample, typically measured in cm [13] [14]. Absorbance itself is a dimensionless quantity defined from the ratio of the incident light intensity (I₀) to the transmitted light intensity (I), as shown in Equation 2 [13] [15]:

A = log₁₀ (I₀ / I) (Equation 2)

The following diagram illustrates the core concepts and the logical workflow connecting the measurement to the final determination of concentration using the Beer-Lambert Law.

Distinguishing d-d and Charge Transfer Transitions

In the study of transition metal complexes, it is critical to differentiate between two primary types of electronic transitions observed in UV-Vis spectra, as they have distinct intensities and underlying mechanisms [2].

d-d Transitions: These occur between molecular orbitals that are primarily metal-based in character—specifically, between the split d-orbitals in a crystal field (e.g., from t₂g to e_g in an octahedral complex) [2]. These transitions are Laporte-forbidden and thus have characteristically low molar absorptivity values (ε < 1,000 M⁻¹cm⁻¹) [2]. The energy of these transitions provides direct insight into the crystal field splitting parameter (Δₒ).

Charge Transfer (CT) Transitions: These are electronic transitions between molecular orbitals that are predominantly localized on the metal to those localized on the ligand, or vice versa. They are categorized as:

- Ligand-to-Metal Charge Transfer (LMCT): Electron transition from a ligand-based orbital to a metal-based orbital.

- Metal-to-Ligand Charge Transfer (MLCT): Electron transition from a metal-based orbital to a ligand-based orbital. Charge transfer transitions are formally allowed and consequently exhibit very high intensity, with molar absorptivity values often exceeding 10,000 M⁻¹cm⁻¹ [2]. The intense purple color of permanganate (KMnO₄) is a classic example of an LMCT transition [16].

Table 1: Key Differences Between d-d and Charge Transfer Transitions

| Feature | d-d Transition | Charge Transfer Transition |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Transition between metal-centered d-orbitals | Electron transfer between metal and ligand orbitals |

| Selection Rule | Laporte-forbidden | Laporte-allowed |

| Typical Molar Absorptivity (ε) | < 1,000 M⁻¹cm⁻¹ [2] | > 10,000 M⁻¹cm⁻¹ [2] |

| Band Width | Relatively broad | Often broad, can be sharp |

| Dependence on Geometry | Strong (e.g., Octahedral vs. Tetrahedral) | Less direct dependence |

Key Parameters and Their Interpretation

Molar Absorptivity (ε)

The molar absorption coefficient (ε) is an intrinsic property of a chemical species at a given wavelength and under specific conditions (solvent, temperature, pH) [14] [17]. It is a measure of the probability of an electronic transition; a high ε value indicates a highly probable (allowed) transition. The IUPAC recommends the term "molar absorption coefficient" over older terms like "molar absorptivity" or "molar extinction coefficient," which are now discouraged [14] [17]. The SI unit for ε is m²/mol, but it is most commonly reported in practical research as M⁻¹cm⁻¹ (which is equivalent to 0.1 m²/mol) [14].

Absorbance (A) and Transmittance (T)

Absorbance (A) is the primary measured quantity in a UV-Vis experiment and is directly related to the concentration of the analyte via the Beer-Lambert Law [13]. Transmittance (T) is the ratio of the transmitted to the incident light intensity (I/I₀) and is often expressed as a percentage [15]. The relationship between absorbance and percent transmittance is logarithmic, as detailed in Table 2.

Table 2: Relationship Between Absorbance and Transmittance

| Absorbance (A) | Transmittance (T) | % Transmittance (%T) | Light Transmitted |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 100% | 100% |

| 0.1 | ~0.79 | ~79% | 79% |

| 0.3 | 0.5 | 50% | 50% |

| 1 | 0.1 | 10% | 10% [13] [15] |

| 2 | 0.01 | 1% | 1% [15] |

| 3 | 0.001 | 0.1% | 0.1% [15] |

For reliable quantitative analysis, it is recommended to maintain absorbance readings within the dynamic range of the instrument, typically between 0.1 and 1.0 [1]. Absorbance values significantly above 1 (meaning less than 10% transmittance) can lead to unreliable quantitation due to insufficient light reaching the detector [1].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Calibration Curve Method for Determining Unknown Concentration

This is the standard method for quantifying an analyte of known identity but unknown concentration in solution.

Workflow Overview:

Materials and Reagents:

- Solute: High-purity transition metal complex (e.g., [Ti(H₂O)₆]³⁺).

- Solvent: High-purity, UV-transparent solvent appropriate for the complex (e.g., water, acetonitrile). The solvent must not absorb significantly in the spectral region of interest.

- Volumetric Flasks: Class A, for accurate preparation of standard solutions.

- Cuvettes: Quartz, with a defined path length (e.g., 1.00 cm). Quartz is essential for UV light transmission [1]. Ensure cuvettes are clean and free of scratches.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Preparation of Standard Solutions:

- Accurately prepare a stock solution of the metal complex with a known, precise concentration.

- Using serial dilution, prepare at least five standard solutions of varying, known concentrations that bracket the expected concentration of the unknown sample [15]. This verifies the linearity of the Beer-Lambert Law for your system.

Spectroscopic Measurement:

- Zero the spectrophotometer using a blank cuvette filled only with the pure solvent.

- Measure the absorbance of each standard solution at its λ_max (wavelength of maximum absorbance). For d-d transitions, this will be in the visible region. Perform each measurement in triplicate.

Calibration Curve Construction:

- Plot the average absorbance (y-axis) against the corresponding known concentration (x-axis) for each standard.

- Perform linear regression analysis (y = mx + b) to obtain the best-fit line. The slope of this line is equal to εl.

Analysis of the Unknown:

- Measure the absorbance of the unknown sample at the same λ_max and under identical instrumental conditions.

- Use the equation of the calibration curve to calculate the concentration of the unknown: c_unknown = (A_unknown - b) / m.

Protocol 2: Determination of Molar Absorptivity (ε) for a Novel Complex

This protocol is used to characterize a newly synthesized or poorly documented coordination complex.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Prepare a Master Solution:

- Accurately weigh a known mass of the pure, dry complex.

- Dissolve it in a known volume of solvent to create a master solution of precise molar concentration (c_master).

Measure Absorbance and Path Length:

- Measure the absorbance (A) of the master solution at λ_max using a quartz cuvette of a known, precise path length (l). A standard path length is 1.000 cm.

Calculate Molar Absorptivity:

- Apply the Beer-Lambert Law directly to calculate ε: ε = A / (c * l).

- Report the value with units of M⁻¹cm⁻¹, and specify the solvent and wavelength (e.g., ε = 150 M⁻¹cm⁻¹ in H₂O at 510 nm).

Important Note: Relying on a single literature value for ε for quantitative analysis is not recommended. It is always preferable to determine ε experimentally under your specific laboratory conditions [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for UV-Vis Analysis of Coordination Complexes

| Item | Function & Importance | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Quartz Cuvettes | Sample holder for spectroscopic measurement. | Path length: 1.00 cm (standard). Quartz is mandatory for UV light transmission (below ~350 nm); glass or plastic cuvettes are unsuitable as they absorb UV light [1]. |

| High-Purity Solvents | To dissolve the analyte without interfering with the measurement. | Must be UV-transparent (spectrophotometric grade). Common choices include water, acetonitrile, and methanol. The solvent cutoff wavelength must be lower than the analyte's λ_max. |

| Volumetric Glassware | For accurate preparation of standard and sample solutions. | Class A certified for high precision and minimal tolerance. |

| Deuterium & Tungsten Lamps | Light sources in the spectrophotometer. | The deuterium lamp covers the UV range, and the tungsten/halogen lamp covers the visible range. The instrument automatically switches between them during a scan [1]. |

| Blank Solution | A reference to correct for solvent and cuvette absorbance. | Consists of the pure solvent used to prepare the sample, contained in an identical cuvette. Its signal is subtracted to report the true absorbance of the analyte [1]. |

Data Analysis and Troubleshooting

Calculating the Octahedral Splitting Energy (Δₒ)

For d-d transitions in octahedral complexes, the wavelength of maximum absorption (λ_max) is directly related to the crystal field splitting parameter, Δₒ. The energy of the transition is calculated using Equation 3, and subsequently, Δₒ is determined.

E = hc / λ_max (Equation 3)

Where:

- E is the energy of the transition (in Joules).

- h is Planck's constant (6.626 × 10⁻³⁴ J·s).

- c is the speed of light (3.00 × 10⁸ m/s).

- λ_max is the wavelength of maximum absorption (in meters).

Example Calculation: The [Ti(H₂O)₆]³⁺ complex absorbs light at 498 nm. The octahedral splitting energy is calculated as follows [16]:

- E = (6.626 × 10⁻³⁴ J·s) × (3.00 × 10⁸ m/s) / (498 × 10⁻⁹ m)

- E ≈ 3.99 × 10⁻¹⁹ J

- Δₒ = E ≈ 4.00 × 10⁻¹⁹ J (This value can also be converted to kJ/mol or cm⁻¹ for comparison with literature values).

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Table 4: Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Non-linear Calibration Curve | High analyte concentration, molecular association, instrumental limitations [18] [1]. | Dilute samples to ensure A < 1. Verify the linear range for your specific compound. |

| Negative Absorbance | The blank has a higher absorbance than the sample. | Ensure the blank is chemically identical to the sample solvent and that the cuvettes are perfectly matched and clean. |

| High Signal Noise | Insufficient light reaching the detector, dirty cuvettes, light scattering. | Use a shorter path length cuvette for concentrated samples, clean cuvettes properly, and filter samples if colloidal particles are present [1]. |

| Spectral Bands Are Too Weak | d-d transitions are inherently weak (forbidden); low concentration. | Confirm the complex is in the correct d-electron configuration (d¹ to d⁹). Increase the sample concentration or use a cuvette with a longer path length. |

| Deviation from Beer's Law | Chemical effects (e.g., polymerization, oxidation) or optical effects (stray light, fluorescence) [18]. | Verify the chemical stability of the complex over the measurement time. Use high-quality instrumentation and appropriate filters. |

Within the broader context of research on d-d transition analysis in octahedral complexes using UV-Vis spectroscopy, this study provides a consolidated reference on the spectral signatures of three common transition metal ions: Cu(II), Ni(II), and Fe(III). The analysis of d-d transitions is a cornerstone of inorganic chemistry, providing critical insights into the geometric and electronic structure of metal complexes, which is paramount for applications in catalysis, material science, and drug development [3]. The characteristic colors of transition metal complexes originate from the excitation of d-orbital electrons from a lower energy level to a higher one within the split d-orbitals of an octahedral ligand field [3]. The specific energies of these transitions are exquisitely sensitive to the metal's identity, oxidation state, and the nature of its surrounding ligands, making UV-Vis spectroscopy a powerful diagnostic tool [3] [19]. This application note summarizes key quantitative spectral data and provides detailed protocols for researchers to reliably obtain and interpret these signatures.

The spectral behavior of Cu(II), Ni(II), and Fe(III) in octahedral coordination environments is distinct, reflecting their unique electronic configurations (d⁹, d⁸, and d⁵, respectively). Table 1 consolidates key spectral characteristics for these ions based on experimental data, while Table 2 outlines the influence of experimental conditions on their spectra.

Table 1: Spectral Characteristics of Selected Octahedral Ions

| Metal Ion & Electronic Configuration | Example Complex | Observed Color | Absorption Wavelength (λmax) | Approximate Absorption Region | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu(II) (d⁹) | [Cu(H₂O)₆]²⁺ |

Pale blue | ~780 nm | Red region | [20] |

[Cu(NH₃)₄(H₂O)₂]²⁺ |

Dark blue | ~650 nm | Yellow-orange-red region | [20] | |

| Ni(II) (d⁸) | Ni²⁺ in aqueous perchlorate/triflate |

Not specified | ~400 nm, ~720 nm (at 150°C) | Visible to Near-IR | [21] |

NiCl⁺ complex |

Not specified | Systematic "red-shift" | Visible region | [21] | |

| Fe(III) (d⁵) | High-spin Fe(III)-CDO (Cys-bound) | Data from spectroscopy | Features characteristic of direct S-ligation | Not specified | [22] |

Table 2: Influence of Experimental Conditions on Spectral Data

| Factor | Effect on UV-Vis Spectrum | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Ligand Identity | Changes the crystal field splitting energy (Δ₀), causing a shift in λmax. Stronger field ligands increase Δ₀, leading to a shift to higher energy (shorter wavelength). | Replacing H₂O (weaker field) with NH₃ (stronger field) in Cu(II) complexes shifts λmax from 780 nm to 650 nm [20]. |

| Temperature | Can cause a "red-shift" (shift to longer wavelength) in absorption peaks due to changes in ligand field strength and complex stability. | Aqueous Ni²⁺ shows a red-shift with increasing temperature from 26°C to 250°C [21]. |

| Chloride Concentration | Formation of chloride complexes (e.g., NiCl⁺, NiCl₂(aq), NiCl₃⁻) leads to a systematic red-shift in the spectrum. | Spectra of nickel chloride solutions show a systematic red-shift with increasing chloride concentration [21]. |

Experimental Protocols

Sample Preparation

3.1.1 Synthesis of Bis(ethylenediamine) Copper(II) Complexes

- Objective: To prepare single crystals of octahedral

[Cu(en)₂(H₂O)₂]²⁺complex salts for structural and spectral analysis [19]. - Materials: Copper sulfate pentahydrate, sodium salt of the desired carboxylic acid (e.g., 2-phenoxybenzoic acid, diphenylacetic acid), ethylenediamine, methanol, water.

- Procedure:

- React copper sulfate pentahydrate with a two-molar equivalent of the sodium salt of the carboxylic acid in aqueous medium to form a precipitated copper(II) carboxylate.

- Separate the precipitated product and dissolve/suspend it in a methanol-water solution.

- Add ethylenediamine to the suspension and allow the mixture to stand for slow evaporation at room temperature.

- Collect the resulting single crystals after several days and dry them in air [19].

3.1.2 Preparation of Fe(III)-CDO for Spectroscopic Study

- Objective: To prepare substrate-bound Fe(III) cysteine dioxygenase (CDO) for characterizing its electronic structure.

- Materials: Purified CDO protein, HEPES buffer (25 mM, 200 mM NaCl, pH 7.5), cysteine or selenocysteine substrate.

- Procedure:

- Determine protein concentration spectrophotometrically (ε₂₈₀ = 25,300 M⁻¹cm⁻¹) and iron content via a colorimetric assay.

- Prepare the sample anaerobically with a final CDO concentration of ~1 mM (by Fe) in buffer.

- Add a two-fold excess of cysteine (or selenocysteine) to the anaerobic sample to form the substrate-bound complex [22].

UV-Vis Spectral Measurement

3.2.1 Data Acquisition for Solution Complexes

- Instrumentation: UV-Vis spectrophotometer (e.g., Cary 100 Bio, Varian Cary 5e).

- Procedure:

- Prepare a solution of the complex in an appropriate solvent (e.g., water, DMSO) at a concentration of ~1 × 10⁻³ M [23].

- Place the solution in a suitable cuvette (e.g., path length of 1 cm).

- Acquire the absorption spectrum across the UV-Vis range (e.g., 350-800 nm) [21].

- For temperature-dependent studies, use a high-temperature flow-through cell with precise temperature control (±0.5 °C) and collect spectra at desired temperatures [21].

3.2.2 Analysis of Spectral Data

- Beer-Lambert Law: Analyze the absorbance (A) using the equation

A = εlc, whereεis the molar absorptivity,lis the path length, andcis the concentration [3] [21]. - Complex Speciation: For systems in equilibrium, use the Beer-Lambert law in a multi-component form:

A/l = Σ [M_i] ε_i, where[M_i]andε_iare the concentration and molar absorptivity of the i-th species, respectively. This allows for the determination of formation constants for complexes like NiCl⁺ [21].

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

The process of synthesizing a complex and relating its molecular and electronic structure to its spectral output can be visualized as a workflow. Furthermore, the origin of the spectral signatures themselves is rooted in the electronic transitions within the metal center.

Research Workflow for Spectral Analysis

Electronic Transitions and Color

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Octahedral Complex Synthesis and Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Example Application / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Ethylenediamine (en) | A common bidentate N-donor ligand used to model protein-metal interactions and form stable chelate complexes. | Used to synthesize model copper(II) complexes like [Cu(en)₂(H₂O)₂]²⁺ [19]. |

| Schiff Base Ligands | A class of ligands with an azomethine group (-C=N-); versatile for creating complexes with diverse geometrical features and biological activity. | Used in synthesizing mixed-ligand V(III), Fe(III), and Ni(II) complexes for antimicrobial studies [23]. |

| 2-Amino-4-methylpyrimidine (AMPY) | A heterocyclic ligand; its derivatives are crucial for understanding metal ion binding in biological systems due to their presence in nucleic acids. | Serves as a co-ligand in mixed-ligand complexes with Schiff bases [23]. |

| Copper(II) Sulfate Pentahydrate | A common, versatile precursor for synthesizing a wide range of copper(II) complexes. | Starting material for the synthesis of copper(II) carboxylate and ethylenediamine complexes [19]. |

| High-Temperature Spectroscopic Cell | Allows for the acquisition of UV-Vis spectra under controlled, elevated temperatures and pressures. | Critical for studying metal speciation in hydrothermal fluids or molten salts [21] [24]. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | A computational method used to model and predict the geometric and electronic structure of metal complexes, supporting experimental spectral data. | Used to optimize structures and interpret electronic transitions in Cu(proline)₂ and Fe-CDO complexes [25] [22]. |

From Theory to Bench: Practical Protocols for Complex Characterization and Biomedical Applications

Purpose and Scope

This Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) outlines the detailed methodology for the preparation of metal complex samples and their subsequent measurement via Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy. This protocol is specifically designed for the analysis of d-d transitions in octahedral transition metal complexes, which is a fundamental technique in inorganic chemistry and pharmaceutical development research [3]. The procedures ensure consistent, reproducible results for quantifying electronic transitions, characterizing ligand field parameters, and determining complex stoichiometry.

The primary application within this context is the investigation of the electronic spectra of transition metal compounds and complexes, with a particular focus on how the splitting of d-orbitals in an octahedral field gives rise to characteristic absorption bands [3]. This protocol is essential for researchers and scientists engaged in the synthesis and characterization of novel metal-based compounds for analytical and therapeutic applications.

Theory and Principles

In UV-Vis spectroscopy, d-d transitions occur when an electron in a d-orbital of a transition metal ion is excited by light to a higher energy d-orbital [3]. In an octahedral complex, the degeneracy of the metal's d-orbitals is lifted, splitting them into lower-energy (t₂g) and higher-energy (e_g) sets. The energy difference between these sets is the ligand field splitting parameter, Δ₀ [3].

The wavelength of light absorbed corresponds to this energy gap and is influenced by the identity of the metal ion, its oxidation state, and the nature of the ligands [3]. The complimentary color observed is opposite the absorbed wavelength on the color wheel [12]. Furthermore, the intensity of d-d transitions is governed by selection rules; transitions that are spin-forbidden or symmetry-forbidden (in complexes with a center of inversion) typically have low molar absorptivity (ε) [3]. It is crucial to differentiate these d-d transitions from more intense charge transfer (CT) bands, which involve electron transfer between the metal and ligand orbitals [26].

Reagents and Materials

Table 1: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Transition Metal Salts (e.g., Cu(II), Co(II), Ni(II) chlorides or acetates) | The source of the metal ion for complex formation. The choice of metal and its oxidation state directly determines the d-electron configuration and the resulting d-d transition energies [27] [28]. |

| Schiff Base Ligands (e.g., derived from salicylaldehyde and amines) | Common chelating ligands that form stable complexes with transition metals. Their strong chromophore activity facilitates detection and their structure influences the ligand field strength [27] [28]. |

| Anhydrous Ethanol & Methanol | High-purity, anhydrous solvents are used for the synthesis and dissolution of complexes to prevent hydrolysis or unwanted side reactions [27] [28]. |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) & Dimethylformamide (DMF) | High-polarity, aprotic solvents commonly used to prepare stock solutions of metal complexes for spectroscopic analysis due to their excellent solvating power [27]. |

| Spectroscopic-Grade Solvents (e.g., Acetonitrile, Hexane) | Used for dilution and final sample preparation. High purity is required to avoid interfering absorbances in the UV region [12]. |

| Glacial Acetic Acid | Used as a catalytic agent in the synthesis of Schiff base ligands via condensation reactions [27] [28]. |

Equipment and Instrumentation

- UV-Vis Spectrophotometer (e.g., Shimadzu UV-2600) with matched quartz cuvettes (path length typically 1.0 cm)

- Analytical Balance (precision ±0.0001 g)

- Ultrasonic Bath

- Volumetric Flasks (Class A, various sizes)

- Micropipettes

- Filtration Assembly (0.45 μm or 0.2 μm syringe filters)

Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete end-to-end workflow for the preparation and measurement of metal complex samples, from synthesis to data analysis.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Synthesis of Metal Complexes (Representative Protocol)

This protocol is adapted from recent literature for synthesizing Schiff base metal complexes [27].

- Ligand Synthesis: Reflux an equimolar mixture of the aldehyde (e.g., 3–4-(diethylamino)-2-hydroxybenzaldehyde, 2 mmol) and the diamine (e.g., 4-nitrobenzene-1,2-diamine, 2 mmol) in 40 mL of ethanol with a few drops of glacial acetic acid as a catalyst for 2 hours [27].

- Complex Formation: To the warm ligand solution, add a solution of the metal salt (e.g., cobalt(II) acetate, 2 mmol) in a minimal volume of methanol (25 mL) dropwise with vigorous stirring.

- Isolation: Reflux the reaction mixture for 4 hours. Cool the mixture to room temperature, filter the resulting precipitate, wash thoroughly with ethanol, and dry in a vacuum desiccator [27].

Sample Preparation for UV-Vis Analysis

- Stock Solution Preparation: Accurately weigh 2.0 - 5.0 mg of the purified, dry metal complex. Transfer it to a 10 mL volumetric flask and dissolve in a suitable solvent (e.g., DMF or DMSO). Dilute to the mark with the same solvent and mix thoroughly to create a stock solution of known concentration (e.g., ~5 x 10⁻⁴ M).

- Working Solution Preparation: Using a micropipette, dilute an appropriate aliquot of the stock solution (e.g., 0.5 mL) with spectroscopic-grade solvent in a second volumetric flask to achieve the target concentration for measurement. The optimal absorbance range is 0.2 - 1.0.

- Filtration: Filter the working solution through a 0.45 μm or 0.2 μm syringe filter directly into a clean quartz cuvette to remove any particulate matter that could cause light scattering.

Instrument Operation and Measurement

- System Initialization: Power on the UV-Vis spectrophotometer and allow the lamp to warm up for the time specified by the manufacturer (typically 15-30 minutes).

- Baseline Correction: Fill a quartz cuvette with the pure solvent used for dilution. Place it in the sample holder and run a baseline correction (blank measurement) over the 200-800 nm wavelength range.

- Sample Measurement: Replace the blank cuvette with the cuvette containing the filtered sample solution. Run the absorbance scan from 200 to 800 nm. Record the spectrum, noting all absorption maxima (λ_max) and their corresponding absorbance values.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Quantitative Data Analysis

Molar absorptivity (ε) is a critical parameter for characterizing transition intensity. It is calculated using the Beer-Lambert Law [3]: A = ε * l * c Where:

- A = Measured Absorbance at λ_max

- ε = Molar Absorptivity (L·mol⁻¹·cm⁻¹)

- l = Pathlength of the cuvette (cm)

- c = Concentration of the complex (mol·L⁻¹)

Table 2: Exemplary UV-Vis Spectral Data for Selected Metal Complexes

| Metal Complex | Typical d-d Transition λ_max (nm) [3] | Approximate Molar Absorptivity (ε) [3] | Assigned Electronic Transition |

|---|---|---|---|

| [CrCl(NH₃)₅]²⁺ | ~400, ~575 | Low (ε < 100) | Partially forbidden d-d transitions |

| Co(II) Complexes | Multiple bands in 400-600 nm range | Low to Moderate | ⁴T₁g → ⁴T₂g, ⁴T₁g(F) → ⁴A₂g, etc. |

| Cu(II) Complexes | Broad band ~600-800 nm | Low (ε ~ 20-100) | ²E_g → ²T₂g |

Spectral Interpretation Guide

The following decision tree aids in the systematic interpretation of a UV-Vis spectrum from a transition metal complex.

- Identify Band Type: Differentiate between weak d-d transitions and intense Charge Transfer (CT) bands based on their molar absorptivity, as detailed in the diagram above [26] [3].

- Determine Ligand Field Strength: The energy of a d-d transition is directly related to the ligand field splitting parameter, Δ₀. Use the relationship Δ₀ = hc / λmax to calculate the splitting energy, where h is Planck's constant, c is the speed of light, and λmax is the wavelength of the absorption maximum.

- Correlate with Structure: Correlate the observed Δ₀ with the spectrochemical series to rank the field strength of the ligands in the complex. Strong-field ligands (e.g., CN⁻) produce larger Δ₀ (shorter λ_max) compared to weak-field ligands (e.g., H₂O).

Azo-dye metal complexes represent a significant class of coordination compounds in modern inorganic chemistry, particularly as models for understanding bidentate ligand coordination behavior. These complexes, characterized by the presence of one or more azo groups (-N=N-), provide excellent platforms for investigating octahedral geometry and electronic transitions through UV-Vis spectroscopy. The structural versatility of azo dyes allows them to coordinate with transition metals through various donor atoms, most commonly via the azo nitrogen and a neighboring oxygen atom from hydroxyl or carbonyl groups [29] [30]. This coordination pattern creates stable chelate rings that mimic biological metal-binding sites while offering tunable photophysical properties. Within the context of d-d transition analysis in octahedral complexes, azo-dye complexes serve as ideal model systems due to their distinct electronic spectra, predictable geometries, and synthetic accessibility [30] [31]. The investigation of these complexes bridges fundamental coordination chemistry with practical applications in sensing, medicine, and materials science, providing researchers with valuable insights into structure-property relationships.

Experimental Protocols

Synthesis of Azo-Dye Ligands

Diazotization and Diazo-Coupling Procedure

The synthesis of azo-dye ligands follows a well-established diazotization-coupling sequence that can be adapted for various aromatic amines and coupling agents [32] [33].

Step 1: Diazotization

- Dissolve 0.42 mmol of aromatic amine (e.g., 1,4-diaminoanthraquinone) in 20 mL of 1 M HCl with magnetic stirring for 5 minutes [32]

- Cool the mixture to 5°C in an ice bath to maintain reaction control

- Add sodium nitrite solution (30 mg in 5 mL deionized water) dropwise to the cooled amine solution

- Continue stirring for 30 minutes at maintained low temperature

- Monitor reaction progress using starch-iodide paper, which indicates excess nitrous acid through blue coloration

Step 2: Diazo-Coupling

- Prepare a solution of the coupling component (e.g., 8-hydroxyquinoline, 61 mg) in 1.5 mL of 1 M NaOH and 10 mL deionized water [32]

- Slowly add the cold diazonium salt solution to the coupling component with continuous stirring

- Adjust pH to approximately 2 using dilute HCl after 20 minutes of stirring

- Allow the reaction to proceed for 2.5 hours for complete coupling

- Isolate the resulting precipitate by vacuum filtration

- Neutralize to pH 7 with 0.1 M NaOH and wash thoroughly with deionized water

- Purify the crude product via column chromatography using silica gel with gradient elution (hexane/ethyl acetate → ethyl acetate/methanol)

This protocol yields functionalized azo dyes capable of bidentate coordination through adjacent nitrogen and oxygen donor atoms, with structural confirmation via ( ^1 \text{H} )-NMR, ( ^{13} \text{C} )-NMR, FT-IR, and mass spectrometry [32] [33].

Synthesis of Metal Complexes

General Complexation Methodology

The formation of metal complexes with azo-dye ligands follows a standardized reflux approach that ensures complete coordination [30] [33]:

- Prepare a 1 mmol sample of the synthesized azo dye dissolved in 20 mL of 95% ethanol

- Stir with 20 mL of 0.01 M alcoholic sodium hydroxide for 15 minutes to facilitate deprotonation

- Add a solution of metal salt (0.5 mmol in 20 mL of 1:1 ethyl alcohol-water mixture) dropwise over 5 minutes

- Reflux the reaction mixture for 2-4 hours with continuous stirring

- Allow the solution to cool slowly overnight to promote crystallization

- Collect precipitates by filtration, wash with cold ethanol, and dry under vacuum over anhydrous calcium chloride

This method typically produces complexes with 2:1 ligand-to-metal stoichiometry, as confirmed by elemental analysis and mass spectrometry [30] [33]. The choice of metal salt (chlorides, nitrates, or perchlorates) influences the counterions in the final complex and may affect solubility properties.

Characterization Techniques

Spectroscopic Analysis Protocol

UV-Vis Spectroscopy for d-d Transition Analysis:

- Prepare 10( ^{-3} ) M solutions of ligands and complexes in appropriate solvents (DMSO, methanol, or acetone)

- Record spectra between 250-800 nm using 1 cm pathlength quartz cuvettes

- Identify charge-transfer bands (typically 350-500 nm) and d-d transitions (500-800 nm) [30] [31]

- For octahedral complexes, expect two or three d-d transition bands corresponding to ( ^4\text{A}{2g} \rightarrow ^4\text{T}{2g} ), ( ^4\text{A}{2g} \rightarrow ^4\text{T}{1g}(\text{F}) ), and ( ^4\text{A}{2g} \rightarrow ^4\text{T}{1g}(\text{P}) ) for d( ^3 ) systems, or ( ^3\text{T}{1g} \rightarrow ^3\text{A}{2g} ), ( ^3\text{T}{1g} \rightarrow ^3\text{T}{2g} ), and ( ^3\text{T}{1g} \rightarrow ^3\text{T}{1g}(\text{P}) ) for d( ^8 ) systems

- Calculate crystal field splitting parameters (10Dq) and Racah parameters (B) from the recorded spectra

FT-IR Spectroscopy for Coordination Mode Determination:

- Prepare samples as KBr pellets (1-2% sample concentration)

- Record spectra in the 4000-400 cm( ^{-1} ) range

- Identify key shifts in vibrational frequencies upon complexation:

Magnetic Susceptibility Measurements:

- Use Gouy balance with Hg[Co(SCN)( _4 )] as calibration standard

- Measure magnetic moments at room temperature

- Interpret results for octahedral geometries:

Results and Discussion

Coordination Behavior and Structural Features

Azo-dye ligands typically exhibit bidentate coordination through the azo nitrogen and an adjacent oxygen donor atom, forming stable five- or six-membered chelate rings with metal centers. Structural analyses confirm that deprotonated phenolic oxygen atoms and azo nitrogen atoms serve as the primary coordination sites, with the ligand acting in an anionic fashion after deprotonation [29] [30]. This coordination mode creates distorted octahedral geometries for first-row transition metals when additional ligands (commonly water molecules) complete the coordination sphere.

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction studies of a novel trans-Pd(O,N)( _2 ) complex reveal a slightly distorted square-planar geometry around the Pd(II) center, with the deprotonated phenolic diazene form of the azo ligand coordinating through one nitrogen atom of the azo group and the ionic oxygen of the phenol [29]. Despite the square planar geometry of this Pd(II) complex, most first-row transition metals form octahedral complexes, particularly with a 2:1 ligand-to-metal ratio where each ligand occupies two coordination sites.

Table 1: Coordination Properties of Selected Azo-Dye Metal Complexes

| Complex | Coordination Mode | Geometry | Metal-Ligand Bonds | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Cu(CNN)( _2 )(H( _2 )O)( _2 )] | Bidentate (N, O) | Octahedral | Cu-N: ~471 cm( ^{-1} ), Cu-O: ~548 cm( ^{-1} ) | [30] |

| [Ni(CNN)( _2 )(H( _2 )O)( _2 )] | Bidentate (N, O) | Octahedral | Ni-N: ~467 cm( ^{-1} ), Ni-O: ~565 cm( ^{-1} ) | [30] |

| [Fe(CNN)( _2 )(H( _2 )O)Cl]·H( _2 )O | Bidentate (N, O) | Octahedral | Fe-N: ~468 cm( ^{-1} ), Fe-O: ~589 cm( ^{-1} ) | [30] |

| trans-Pd(O,N)( _2 ) | Bidentate (N, O) | Square planar | Pd-N, Pd-O confirmed by SC-XRD | [29] |

| [Zn(ANSR)( _2 )] | Bidentate (N, O) | Tetrahedral | Coordination via OH oxygen and azo nitrogen | [33] |

The formation of extensive hydrogen-bonding networks further stabilizes these complexes in the solid state. For instance, non-classical C-H···O hydrogen bonding creates edge-fused rings described as R( _2^2 )(24) and R( _2^2 )(12) synthons, leading to the development of a three-dimensional network with a linked parallel matrix [29]. Hirshfeld surface analysis confirms the presence of numerous hot spots on the complex surface, indicative of strong non-classical interactions that contribute to crystal packing and stability.

Electronic Spectra and d-d Transitions

UV-Vis spectroscopy provides crucial information about the electronic structure of azo-dye complexes, particularly regarding d-d transitions in octahedral coordination environments. The absorption spectra typically feature three distinct regions: intense intra-ligand transitions in the UV region, metal-to-ligand or ligand-to-metal charge transfer bands in the near-UV to visible region, and weaker d-d transitions in the visible to near-IR region [30] [31].

For octahedral Co(II) complexes (d( ^7 )), three spin-allowed transitions are expected: ( ^4\text{T}{1g} ) → ( ^4\text{T}{2g} ) (ν( 1 )), ( ^4\text{T}{1g} ) → ( ^4\text{A}{2g} ) (ν( _2 )), and ( ^4\text{T}{1g} ) → ( ^4\text{T}{1g})(P) (ν( _3 )). The ν( _3 )/ν( _2 ) ratio helps distinguish between octahedral and tetrahedral geometries, with values >2.0 indicating octahedral coordination. Ni(II) complexes (d( ^8 )) typically exhibit three spin-allowed transitions: ( ^3\text{A}{2g} ) → ( ^3\text{T}{2g} ) (ν( _1 )), ( ^3\text{A}{2g} ) → ( ^3\text{T}{1g} ) (ν( _2 )), and ( ^3\text{A}{2g} ) → ( ^3\text{T}_{1g})(P) (ν( _3 )), from which the crystal field splitting parameter (10Dq) and Racah parameter (B) can be calculated.

Table 2: Electronic Spectral Data and d-d Transitions of Azo-Dye Complexes