Unlocking Green Hydrogen: A Comprehensive Guide to Photocatalytic Water Splitting Mechanisms and Materials

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the basic mechanisms underlying photocatalytic hydrogen production, a promising pathway for converting solar energy into clean chemical fuel.

Unlocking Green Hydrogen: A Comprehensive Guide to Photocatalytic Water Splitting Mechanisms and Materials

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the basic mechanisms underlying photocatalytic hydrogen production, a promising pathway for converting solar energy into clean chemical fuel. Tailored for researchers and scientists, it explores the fundamental photophysical processes in semiconductors, details advanced material design strategies including heterojunctions and cocatalysts, and addresses critical performance bottlenecks such as charge recombination and photocorrosion. The content systematically compares photocatalytic efficiency against other hydrogen production methods, evaluates environmental impacts, and discusses the integration of emerging technologies like machine learning and photothermal effects to guide future research and development towards scalable, sustainable hydrogen energy solutions.

The Fundamental Principles of Solar-to-Hydrogen Conversion

The global energy crisis and environmental challenges have intensified the search for sustainable and clean energy sources. Hydrogen has emerged as a leading candidate for a next-generation energy carrier due to its high energy density and zero carbon emissions upon combustion [1] [2]. Photocatalytic water splitting, a process that uses semiconductor materials to convert solar energy into chemical energy stored in hydrogen, represents a visionary pathway to a sustainable hydrogen economy [3] [4]. This technology, inspired by natural photosynthesis, enables the direct production of hydrogen from water and sunlight, offering a promising solution to future energy demands [3].

The field was inaugurated in the early 1970s with the groundbreaking discovery of the Honda-Fujishima effect [3] [1]. Fujishima and Honda demonstrated that water could be split into hydrogen and oxygen using a titanium dioxide (TiOâ‚‚) electrode as a photoanode and a platinum counter electrode under UV light irradiation, with an external electrical bias [3]. This pioneering work proved that light energy could drive the chemical reaction of water splitting, laying the foundation for decades of subsequent research into photocatalytic and photoelectrochemical systems [5].

Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

Basic Thermodynamics and Band Structure Requirements

Photocatalytic overall water splitting is an uphill reaction accompanied by a large positive change in Gibbs free energy (ΔG° = 238 kJ molâ»Â¹) [1]. The overall reaction is: 2Hâ‚‚O → 2Hâ‚‚ + Oâ‚‚ [1].

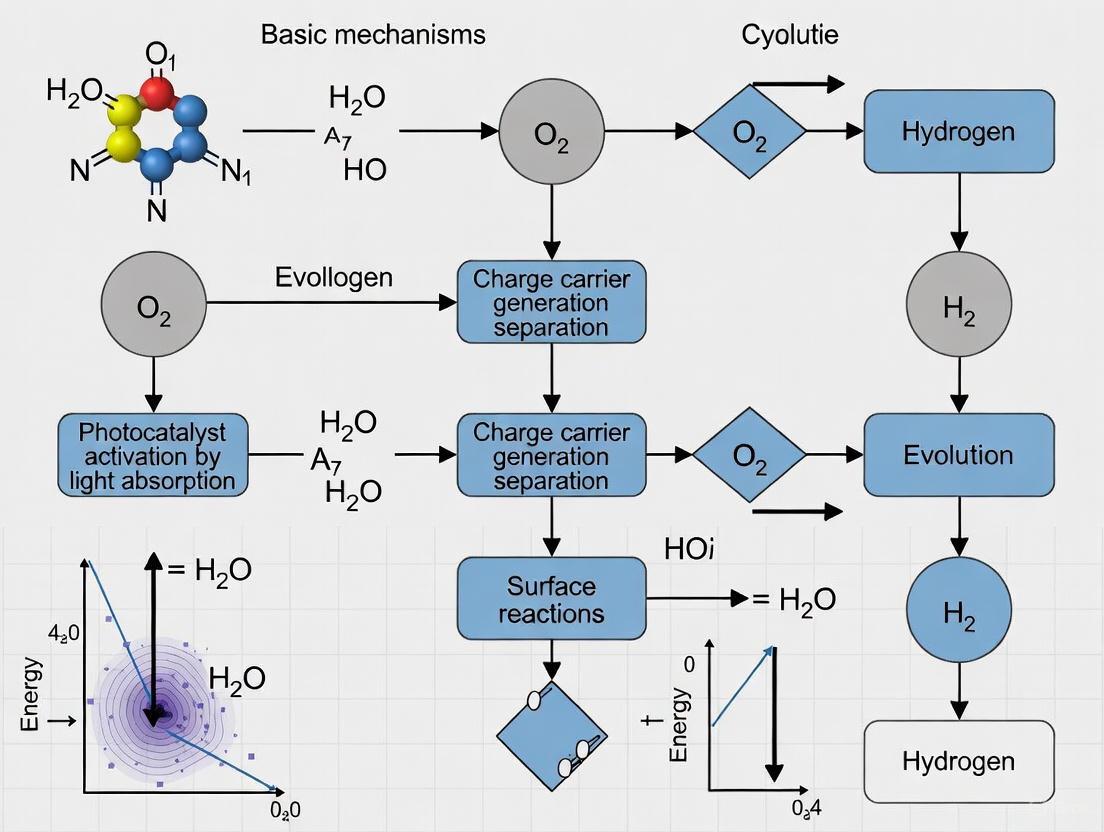

For this reaction to proceed, a semiconductor photocatalyst must meet specific electronic band structure requirements, as illustrated in the diagram below:

The fundamental steps in the photocatalytic water splitting process are as follows:

- Photon Absorption: When a semiconductor absorbs light with energy greater than or equal to its bandgap energy (E_g), electrons (eâ») are excited from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB), creating holes (hâº) in the valence band [3] [1].

- Charge Separation and Migration: The photogenerated electrons and holes separate and migrate to the surface of the photocatalyst [3].

- Surface Redox Reactions: The electrons reduce water to produce hydrogen (2H⺠+ 2e⻠→ Hâ‚‚), while the holes oxidize water to produce oxygen (2Hâ‚‚O + 4h⺠→ Oâ‚‚ + 4Hâº) [3] [2].

The theoretical minimum bandgap energy required to drive the overall water-splitting reaction is 1.23 eV, corresponding to a wavelength of about 1000 nm [1]. However, due to overpotentials and activation barriers, practical photocatalysts require a larger bandgap, typically > 3.0 eV for UV-active materials [6] [5].

Critical Processes and Efficiency Limitations

The overall efficiency of photocatalytic water splitting is governed by three main processes, each presenting specific challenges [3] [1]:

- Light Absorption: Efficient absorption of a broad spectrum of solar radiation, especially visible light (400-800 nm), which constitutes the majority of sunlight. Many stable semiconductors, like TiOâ‚‚, primarily absorb UV light, which accounts for only about 4-5% of the solar spectrum [3] [2] [5].

- Charge Separation and Migration: After generation, electron-hole pairs must separate and migrate to the catalyst surface without recombining. Crystal defects often act as recombination centers, reducing efficiency. High crystallinity and small particle size can mitigate this by reducing the migration distance for charge carriers [3] [1].

- Surface Chemical Reactions: The migrated charges must initiate redox reactions on the catalyst surface. The kinetics of these reactions, particularly the four-electron water oxidation reaction, are often slow. Co-catalysts (e.g., Pt, NiO, RuOâ‚‚) are typically loaded onto the photocatalyst surface to provide active sites and lower the activation energy for gas evolution [3] [1].

Evolution of Photocatalytic Systems

From One-Step to Z-Scheme Systems

Early photocatalytic systems aimed to achieve overall water splitting using a single photocatalyst in a one-step system [3]. However, the stringent requirements for such a material—a suitable band structure, stability, and efficient charge separation—have limited the number of successful single-component photocatalysts [3] [1].

To overcome these limitations, a two-step photoexcitation mechanism, known as the Z-scheme, was developed, inspired by natural photosynthesis in green plants [3]. This system uses two different photocatalysts: one for hydrogen evolution (Hâ‚‚ photocatalyst) and another for oxygen evolution (Oâ‚‚ photocatalyst), coupled by a reversible redox mediator (e.g., Fe³âº/Fe²⺠or IO₃â»/Iâ») in the solution [3]. The Z-scheme system lowers the energy requirement for each photocatalyst, allowing for the use of a wider range of visible-light-responsive semiconductors that possess either a sufficient water reduction or oxidation potential, but not both [3].

Photoelectrochemical vs. Particulate Systems

Two primary approaches exist for implementing water splitting:

- Photoelectrochemical (PEC) Water Splitting: This system uses separate semiconductor electrodes (photoanode and/or photocathode) immersed in an electrolyte, similar to the original Honda-Fujishima cell [3] [1]. The spatial separation of reaction sites can facilitate gas separation, but the requirement for conductive substrates and electrical connections can complicate large-scale application [3] [1].

- Particulate Photocatalytic Water Splitting: This approach uses micrometer-sized semiconductor powder suspended directly in water [1]. This system is simpler and more scalable, as the photocatalyst particles function as both light absorber and reactor. A major challenge is the prevention of the back-reaction (recombination of Hâ‚‚ and Oâ‚‚ into water) and the difficulty in separating the produced gas mixture [1].

Advanced Materials and Modern Strategies

Key Material Classes and Performance

Extensive research has been dedicated to developing efficient photocatalyst materials. The table below summarizes the hydrogen production performance of various modern photocatalysts as reported in recent literature.

Table 1: Performance of Selected Modern Photocatalysts for Hydrogen Production

| Photocatalyst | Co-catalyst | Light Source | Sacrificial Agent | Hâ‚‚ Production Rate | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag-La-CaTiO₃ | None | 1200 W Visible Lamp | None | 6246.09 μmol in 3 h | [7] |

| CdS/CoFeâ‚‚Oâ‚„ on AMS* | None | Light irradiation | None | 254.1 μmol hâ»Â¹ | [8] |

| Rh@Crâ‚‚O₃/SrTiO₃:Al | Rh@Crâ‚‚O₃ | Simulated sunlight | None | 351 μmol gâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹ | [9] |

| MnNbâ‚‚O₆-based composites | Not specified | Visible light | Possibly used | Up to 146 mmol hâ»Â¹ gâ»Â¹ | [6] |

| Pt-loaded CdS with Single-Atom Pt | Pt | Not specified | Not specified | 19.77 mmol gâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹ | [4] |

*AMS: Annealed Melamine Sponge (Gas-solid biphase system)

Strategic Enhancements for Efficiency

Recent advances have focused on sophisticated material engineering strategies to overcome the inherent limitations of semiconductor photocatalysts:

- Bandgap Engineering and Doping: Introducing impurity atoms (e.g., metals, nitrogen, sulfur) into a semiconductor lattice can narrow its bandgap, extending its light absorption into the visible region [4]. For example, codoping CaTiO₃ with Ag and La ions made the typically UV-active material responsive to visible light [7].

- Heterojunction Construction: Coupling two or more semiconductors with aligned band structures can significantly enhance charge separation. In a heterojunction, photogenerated electrons and holes move to different materials, reducing recombination. Z-scheme heterojunctions are particularly effective as they simultaneously maintain strong reduction and oxidation powers while enabling better charge separation [4].

- Morphology and Facet Engineering: Controlling the exposed crystal facets of a photocatalyst can create an internal electric field that drives the spatial separation of electrons and holes to different crystal faces [9]. For instance, SrTiO₃ crystals with specifically exposed {100} and {110}/{111} facets can naturally separate reduction and oxidation sites, enhancing overall water splitting efficiency [9].

- Co-catalyst Integration: Co-catalysts are crucial for providing active sites for gas evolution. Research has expanded beyond noble metals like Pt to include cheaper alternatives such as NiS and MoS₂ for the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) [4]. Core-shell co-catalysts like Rh@Cr₂O₃ are also used to prevent back-reactions on the H₂ evolution sites [9].

- Single-Atom Catalysts and Advanced Systems: The frontier of research involves single-atom catalysts, where isolated metal atoms are anchored on a support, maximizing atomic utilization and providing exceptional catalytic activity [4]. Furthermore, innovative reactor designs, such as transitioning from traditional solid-liquid-gas triphase systems to more efficient gas-solid biphase systems (where reaction occurs with water vapor instead of liquid water), have demonstrated enhanced mass transfer and solar energy utilization [8].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Their Functions

| Reagent/Material | Function in Photocatalytic Water Splitting |

|---|---|

| Pt, NiO, RuOâ‚‚, NiS, MoSâ‚‚ | Co-catalyst; provides active sites for hydrogen or oxygen evolution, lowers activation energy. |

| Methanol, Lactic Acid, Triethanolamine | Sacrificial electron donor (hole scavenger); consumes photogenerated holes to enhance Hâ‚‚ evolution. |

| AgNO₃, Na₂S-Na₂SO₃, Fe³⺠| Sacrificial electron acceptor; consumes photogenerated electrons to enhance O₂ evolution. |

| Redox Mediators (e.g., Fe³âº/Fe²âº, IO₃â»/Iâ») | Electron shuttle in Z-scheme systems; reversibly couples the Hâ‚‚-evolution and Oâ‚‚-evolution photocatalysts. |

| Annealed Melamine Sponge (AMS) | Photothermal substrate in immobilized systems; converts triphase to biphase system, enhancing efficiency. |

Experimental Protocols and Characterization

Synthesis of a Codoped Perovskite Photocatalyst (Ag-La-CaTiO₃)

The synthesis of advanced photocatalysts often involves precise wet-chemical methods. The following protocol for synthesizing Ag-La-CaTiO₃ via the sol-gel method is adapted from a recent study [7]:

- Solution Preparation: Add 3.033 mL of Titanium Tetraisopropoxide (TTIP) to 20 mL of absolute ethanol under vigorous stirring at room temperature for 30 minutes.

- Chelation: Add 5 mL of citric acid (acting as a chelating agent) to the TTIP solution with continuous stirring for another 30 minutes.

- Precursor Addition: Slowly add a mixed stoichiometric solution of Ca(NO₃)₂, La(NO₃)₂, and Ag(NO₃)₂ dropwise to the above mixture. Maintain stirring at 50°C until the solution becomes viscous.

- Gel Formation and Drying: Transfer the viscous yellow solution to an oven and dry at 50°C for 12 hours to obtain a xerogel.

- Calcination: Remove excess organic materials by burning the xerogel using a self-spread method. Subsequently, calcine the resulting powder at 850°C for 10 hours in a muffle furnace to obtain the crystalline Ag-La-CaTiO₃ photocatalyst.

Standardized Photocatalytic Activity Test

The experimental setup for evaluating photocatalytic water splitting typically involves a gas-closed circulation system. The core procedure is as follows [7]:

- Reactor Setup: Use a lab-made, airtight reaction cell connected to a gas circulation system and a gas chromatograph for analysis. The system should be air-free to allow accurate detection of oxygen.

- Reaction Mixture: Disperse a specified amount of photocatalyst (e.g., 500-800 mg) in 1000 mL of deionized water (or an aqueous solution with/without sacrificial agents) within the reaction cell.

- Light Irradiation: Irradiate the suspension using a suitable light source (e.g., a 1200 W metal halide lamp for visible light, a high-pressure mercury lamp for UV light, or a solar simulator). Use appropriate optical filters to select specific wavelength ranges.

- Gas Collection and Analysis: Continuously stir the mixture during irradiation. The evolved gases are collected, often by displacing water or using an inert carrier gas. The amount and composition of the gas (Hâ‚‚ and Oâ‚‚) are quantitatively analyzed using gas chromatography.

Essential Characterization Techniques

A suite of characterization techniques is employed to correlate the physicochemical properties of a photocatalyst with its performance [7]:

- UV-Vis/DRS Spectroscopy: Determines the light absorption range and estimates the bandgap energy of the material.

- X-Ray Diffraction (XRD): Identifies the crystal phase, structure, and average crystal size.

- Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM): Reveals the surface morphology and particle size.

- X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Analyzes the surface chemical composition and elemental oxidation states.

- Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) Surface Area Analysis: Measures the specific surface area and pore structure.

- Photoluminescence (PL) Spectroscopy: Probes the efficiency of charge carrier separation and recombination.

Current Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite significant progress, the widespread commercialization of photocatalytic water splitting faces several key challenges. The solar-to-hydrogen (STH) conversion efficiency of most systems remains below the practical target of 10% set by the U.S. Department of Energy, primarily due to insufficient visible light utilization and rapid charge recombination [9]. The scalability and cost of photocatalyst synthesis, especially those involving noble metal co-catalysts, present significant economic hurdles [4]. Furthermore, ensuring the long-term stability of photocatalysts against photo-corrosion, particularly for non-oxide materials, is crucial for durable operation [5].

Future research is pivoting toward integrated, system-level design. Key emerging directions include [4]:

- AI-Driven Catalyst Design: Using machine learning to predict optimal material compositions and properties, accelerating the discovery of high-performance photocatalysts.

- Tandem and Hybrid Systems: Combining photocatalysts with photovoltaic or electrochemical modules to more efficiently utilize the full solar spectrum and overcome the limitations of single-photon processes.

- Circular Design and Lifecycle Analysis: Developing photocatalysts with a focus on recyclability, low-toxicity synthesis, and reduced reliance on scarce elements to ensure environmental and economic sustainability.

The transition from laboratory discovery to real-world impact will require a shift in focus from purely academic metrics (e.g., quantum yield) to system-level metrics such as long-term stability under sunlight, cost per kilogram of Hâ‚‚ produced, and seamless integration with existing energy infrastructure [4].

Photocatalytic technology represents a transformative platform for solar energy utilization, offering a pathway to address global energy demands and environmental challenges through processes such as hydrogen production via water splitting [10] [11]. This technology, often termed "photosynthesis in the chemical sense," provides an environmentally friendly method for converting solar energy directly into chemical energy [12]. The fundamental process involves a semiconductor material that absorbs light energy and facilitates chemical reactions without being consumed itself. Within the specific context of hydrogen production research, understanding the precise mechanism of photocatalysis is paramount for developing more efficient materials and systems that can make green hydrogen a commercially viable energy carrier [13] [11].

The entire photocatalytic process is a cascade of sequentially coupled stages, from photon absorption to surface chemical reactions, operating across temporally disparate regimes spanning femtoseconds to seconds [14]. This in-depth technical guide provides a systematic breakdown of these core mechanisms, focusing specifically on their application in photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. We will explore the step-by-step process, material design strategies, and advanced characterization techniques that are driving innovation in this critical field of renewable energy research.

The Fundamental Steps of Photocatalysis

The photocatalytic mechanism occurs through a series of interconnected steps that can be broadly categorized into three primary stages: (1) light absorption and electron-hole pair generation, (2) charge separation and migration, and (3) surface redox reactions. Each step presents distinct challenges and opportunities for efficiency improvements, particularly in the context of hydrogen production through water splitting [15] [11].

The photocatalytic process initiates when a photocatalyst is exposed to light with energy equal to or greater than its bandgap energy. During this critical first step, photons are absorbed by the semiconductor material, promoting electrons (eâ») from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB). This excitation creates negatively charged electrons in the CB and leaves behind positively charged holes (hâº) in the VB, forming electron-hole pairs known as excitons [15].

The efficiency of this initial step is fundamentally governed by the electronic structure of the photocatalytic material. The bandgap energy—the energy difference between the valence and conduction bands—determines the range of the solar spectrum that can be harvested. As illustrated in Figure 1, a significant challenge in photocatalyst design lies in the inherent incompatibility between broad light absorption and strong redox capability. While a narrow bandgap is desirable for enhanced visible light absorption, it often comes at the expense of reduced redox driving force, which requires more negative conduction band and more positive valence band positions [11]. For effective overall water splitting, the conduction band must be more negative than the reduction potential for H₂ production (0 V vs. NHE at pH 7), while the valence band must be more positive than the oxidation potential for O₂ generation (1.23 V vs. NHE) [15].

Table 1: Bandgap Properties and Light Absorption Characteristics of Representative Photocatalysts

| Photocatalyst | Bandgap (eV) | Primary Absorption Range | CB Edge Potential (V vs. NHE, pH 7) | VB Edge Potential (V vs. NHE, pH 7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiOâ‚‚ (Anatase) | 3.2 | Ultraviolet | -0.5 | 2.7 |

| g-C₃N₄ | ~2.7 | Visible | ~-1.1 | ~1.6 |

| CdS | 2.4 | Visible | -0.8 | 1.6 |

| ZnO | 3.37 | Ultraviolet | -0.5 | 2.87 |

Step 2: Charge Separation and Migration

Following excitation, the photogenerated electron-hole pairs must separate into free charge carriers and migrate to the catalyst surface before they recombine. This represents one of the most critical efficiency-limiting steps in photocatalysis, as the rate of charge recombination is typically several orders of magnitude higher than that of charge separation [11]. Bulk charge recombination occurs within picoseconds, while charge migration to the surface requires hundreds of picoseconds. Similarly, surface charge recombination happens within tens of nanoseconds, whereas surface reactions require several microseconds to complete [11].

Multiple strategies have been developed to enhance charge separation efficiency:

- Ferroelectric materials generate inherent surface polarization that creates a strong internal electric field to facilitate bulk charge separation [11].

- Heterojunction construction establishes a built-in electric field (BIEF) at the interface between different semiconductors, promoting continuous charge flow driven by differences in work functions [11].

- Electron spin control through doping, defect engineering, or magnetic field application can promote charge separation via spin polarization effects [15].

- Morphological control and facet engineering reduce charge migration distances to the surface, decreasing recombination probabilities [12].

The success of this step determines the fraction of photogenerated charges that ultimately reach the catalyst surface available for redox reactions, with typically less than 1% of initially generated charges surviving recombination losses [14].

Step 3: Surface Redox Reactions

The final stage involves surface-reaching charges driving reduction and oxidation reactions with adsorbed species. For photocatalytic hydrogen production, the key reactions are the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) at reduction sites and the oxygen evolution reaction (OER) at oxidation sites [11]. The surface-reaching electrons reduce water protons to hydrogen gas (2H⺠+ 2e⻠→ Hâ‚‚), while holes oxidize water to oxygen gas (2Hâ‚‚O + 4h⺠→ Oâ‚‚ + 4Hâº) [15].

The kinetics of these surface reactions are critically dependent on the density of surface-reaching charges and the energy barriers of specific reaction steps. Microkinetic simulations reveal that while lowering activation energies for surface reactions shows minimal enhancement at experimentally observed charge concentrations (~10â»â¹ monolayer), sustaining a stable flux of photogenerated charges to the surface could elevate turnover frequency by up to five orders of magnitude [14]. This highlights the scarcity of surface-available charges as the fundamental bottleneck in photocatalytic energy conversion.

Surface engineering strategies focus on creating active sites with optimized adsorption/desorption behaviors for reaction intermediates. For hydrogen production, this involves simultaneously facilitating proton absorption and Hâ‚‚ desorption, which typically encounter conflicting energy barriers on single-component photocatalysts [11]. Interfacial electronic interactions in heterostructures can precisely modulate electronic density at active sites to lower these energy barriers and create dual-functional sites [11].

Figure 1: Photocatalytic Process Flow. The diagram illustrates the sequential steps of photocatalysis, competing recombination pathways, and final products.

Advanced Material Design for Enhanced Photocatalysis

Bandgap Engineering and Heterostructures

Material design plays a pivotal role in optimizing each step of the photocatalytic process. Bandgap engineering through elemental doping, defect creation, and solid solution formation enables the extension of light absorption into the visible spectrum [10] [15]. For instance, doping TiOâ‚‚ with metal or non-metal elements (e.g., N, S, Fe, Co) has proven effective in reducing its bandgap from 3.2 eV to visible-light-responsive ranges [15].

Heterostructure construction represents one of the most promising approaches to overcome the fundamental limitation of single-component photocatalysts. By creating interfaces between different semiconductors with mismatched band alignments, heterojunctions simultaneously broaden light absorption range and optimize redox capability while reducing charge recombination through built-in electric fields [11]. Common configurations include type-II heterojunctions and direct Z-scheme systems, with the latter often achieving higher redox potentials by preserving electrons and holes at higher energy states [12].

Table 2: Performance of Selected Photocatalytic Materials for Hydrogen Evolution

| Photocatalyst System | Co-catalyst | Light Source | Hâ‚‚ Production Rate | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1D/2D CoSâ‚.₀₉₇@ZIS | - | UV-Vis | 2,632.33 μmol gâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹ | [16] |

| MC-CN | Rh/Crâ‚‚O₃ | λ > 420 nm | 57 μmol gâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹ | [16] |

| Pt/ZnInâ‚‚Sâ‚„/BaTiO₃ | Pt | Visible + Ultrasound | 1,335.3 μmol gâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹ | [16] |

| CdS-based systems | Various | Visible | Varies widely (2,000-4,000 μmol gâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹ common) | [12] |

Emerging Strategies: Electron Spin Control and Surface Polarization

Recent advances have introduced innovative approaches for enhancing photocatalytic efficiency. Electron spin control has emerged as a promising strategy for optimizing photocatalysis through multiple mechanisms: tuning energy band structures to extend light absorption, promoting charge separation via spin polarization, and strengthening surface interaction by modulating electron spin states of active sites [15]. Manipulation techniques include doping design, defect engineering, magnetic field regulation, metal coordination modulation, and chiral-induced spin selectivity [15].

Surface modification to manipulate internal electron-hole distribution represents another significant advancement. Systematic investigations into substituent electronic properties in covalent organic frameworks (COFs) have demonstrated that molecular-level engineering can precisely control electron cloud redistribution to minimize carrier recombination [17]. For instance, introducing strong electron-withdrawing groups onto organic frameworks can improve effective separation of electrons and holes, extending the distance between electron-hole pairs and increasing active sites per unit volume [17].

Experimental Protocols and Characterization Techniques

Quantifying Surface-Reaching Charges

A critical challenge in photocatalytic research has been the quantitative assessment of surface-reaching charges, which are crucial for driving redox reactions but difficult to detect due to their scarcity under operational conditions. The adsorbate (methanol) surface elementary reaction kinetic analysis method has been developed to address this challenge [14]. This methodology employs methanol as a probe molecule to quantify surface-reaching photoholes in TiOâ‚‚-based materials through the following protocol:

Catalyst Preparation and Characterization: Synthesize well-defined TiOâ‚‚ nanocrystals with controlled facets ({001}, {100}, and {101}). Characterize crystallographic structure using XRD and surface properties through XPS and FTIR [14].

Methanol Adsorption Study: Conduct controlled methanol adsorption experiments to determine site-specific behaviors. Molecular adsorption primarily occurs at fivefold-coordinated Tiâµâº sites (CH₃OH(a)Ti5c), while dissociative adsorption generates methoxy species (CH₃O(a)) at defect sites including surface oxygen vacancies [14].

Photocatalytic Oxidation Kinetics: Perform methanol photo-oxidation under controlled illumination conditions with oxygen present. The reaction mechanism proceeds as follows:

- CH₃OH → CH₃Oâ» + Hâº

- TiOâ‚‚ + hν → eâ» + hâº

- Oâ‚‚ + e⻠→ O₂•â»

- CH₃OH + h⺠→ CH₃O• + Hâº

- CH₃O⻠+ h⺠→ CH₃O•

- CH₃O• → CHâ‚‚O•⻠+ Hâº

- CH₂O•⻠→ H₂CO + e⻠[14]

Kinetic Analysis: Measure formaldehyde production rates as a function of illumination intensity and methanol coverage. Apply Langmuir-Hinshelwood kinetics to extract surface hole concentrations [14].

This method has been validated across diverse TiOâ‚‚ materials, including defective TiOâ‚‚, transition metal-doped TiOâ‚‚, and noble metal-decorated TiOâ‚‚, providing critical insights into surface/interface design principles that enhance surface-reaching charge concentrations [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Semiconductor Photocatalysts | Light absorption and charge generation | TiO₂, g-C₃N₄, CdS, ZnIn₂S₄, metal oxides/sulfides |

| Co-catalysts | Enhance charge separation and provide active sites | Pt, Ni, NiS, Ru, noble metals, transition metal compounds |

| Sacrificial Reagents | Consume holes to improve electron availability for H₂ evolution | Methanol, triethanolamine, lactic acid, Na₂S/Na₂SO₃ |

| Electron Donors | Facilitate electron transfer in Z-scheme systems | Redox pairs (IO₃â»/Iâ», Fe³âº/Fe²âº), inorganic ions |

| Probe Molecules | Quantify surface-reaching charges and reaction mechanisms | Methanol (for hole quantification), specific organic dyes |

| Precursor Materials | Synthesis of tailored photocatalytic materials | Metal salts (nitrates, chlorides), thiourea, cyanamide, organic linkers for MOFs/COFs |

| Niobium--vanadium (1/2) | Niobium--vanadium (1/2), CAS:57455-59-1, MF:NbV2, MW:194.789 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2-Propanamine, N,N-dipropyl | 2-Propanamine, N,N-dipropyl, CAS:60021-89-8, MF:C9H21N, MW:143.27 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The photocatalytic reaction mechanism represents a sophisticated interplay of physical and chemical processes spanning multiple temporal and spatial scales. From ultrafast light absorption and charge generation events to nanosecond charge separation and microsecond-to-second surface reactions, each step presents distinct challenges and optimization opportunities [15] [14]. Within the context of hydrogen production research, understanding these fundamental mechanisms provides the foundation for developing advanced photocatalytic materials and systems capable of efficient solar-to-chemical energy conversion.

Current research continues to push the boundaries of photocatalytic efficiency through innovative approaches including electron spin control [15], precise surface engineering [17], multifunctional heterostructure design [11], and synergistic processes such as photothermal catalysis [12]. As characterization techniques advance, particularly in the quantitative assessment of surface-reaching charges [14], researchers gain deeper insights into the structure-function relationships governing photocatalytic performance. These developments are steadily bridging the gap between laboratory-scale demonstrations and the large-scale implementation of photocatalytic hydrogen production as a viable component of a sustainable energy future.

Photocatalytic water splitting is a promising technology for converting solar energy into green hydrogen fuel, a process that hinges on the precise electronic properties of semiconductor materials [18] [19]. This process mimics natural photosynthesis, using a solid-state photocatalyst to harvest light and drive the chemical reactions that dissociate water into hydrogen (Hâ‚‚) and oxygen (Oâ‚‚). The efficiency of this transformation is fundamentally governed by the semiconductor's band gap and the energetic positions of its band edges relative to water's redox potentials [20]. For researchers and scientists working in renewable energy and material design, a deep understanding of these core properties is essential for developing next-generation photocatalytic systems. This guide details the critical thermodynamic requirements and material characteristics necessary for efficient photocatalytic water splitting, providing a foundation for ongoing research and development.

Fundamental Thermodynamic and Electronic Requirements

The minimum thermodynamic energy required to split one water molecule into hydrogen and oxygen is a Gibbs free energy change (ΔGâ°) of 1.23 eV per electron transferred [20]. This sets the fundamental energy threshold for the reaction.

For a semiconductor to drive this reaction using light, its electronic structure must meet two primary criteria:

Band Gap Energy (E₉): The photon energy absorbed by the semiconductor must be sufficient to excite electrons from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB), creating electron-hole pairs. While the thermodynamic minimum is 1.23 eV, in practice, due to overpotentials and kinetic losses, the optimal band gap must be larger [18] [20]. Research indicates that for a reasonable solar conversion efficiency, the band gap should be less than 2.2 eV, yet greater than 1.8 eV to provide sufficient driving force for the reaction [20]. An excellent photocatalyst typically requires a bandgap greater than 1.8 eV [18]. Furthermore, to efficiently utilize visible light, the bandgap should ideally be smaller than 3.0 eV [18].

Band Edge Positions: The energy levels of the band edges must straddle the water redox potentials. Specifically:

- The Conduction Band Minimum (CBM) must be more negative (or at a higher energy) than the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) potential, Eâ°(Hâº/Hâ‚‚) = 0 V vs. NHE (Normal Hydrogen Electrode) at pH 0, which corresponds to -4.44 eV in an absolute vacuum scale [18].

- The Valence Band Maximum (VBM) must be more positive (or at a lower energy) than the oxygen evolution reaction (OER) potential, Eâ°(Oâ‚‚/Hâ‚‚O) = 1.23 V vs. NHE, or -5.67 eV absolute [18].

Table 1: Key Thermodynamic and Electronic Criteria for Water Splitting Photocatalysts

| Parameter | Symbol | Theoretical Value | Practical Consideration | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gibbs Free Energy | ΔGⰠ| 1.23 eV | Minimum energy input required per electron | [20] |

| Minimum Band Gap | E₉ | >1.23 eV | Must be >1.8 eV due to overpotentials and band bending | [18] [20] |

| Optimal Band Gap Range | E₉ | 1.8 - 2.2 eV | Balances visible light absorption and sufficient redox driving force | [20] |

| CBM Position | E_{CBM} | > -4.44 eV (absolute) | Must be higher (more negative) than Hâº/Hâ‚‚ reduction potential | [18] |

| VBM Position | E_{VBM} | < -5.67 eV (absolute) | Must be lower (more positive) than Hâ‚‚O/Oâ‚‚ oxidation potential | [18] |

Failure to meet any of these criteria will render a material inactive for overall water splitting, regardless of its other attractive properties, such as high light absorption or good charge carrier mobility.

Material Engineering and Performance of Representative Photocatalysts

A wide variety of semiconductor materials have been explored for photocatalytic water splitting, each with distinct advantages and limitations. Engineering their properties to meet the critical requirements is a central focus of research.

Key Material Classes and Band Structure Engineering

Two-Dimensional (2D) and Janus Materials: 2D materials like the ScTeI monolayer are investigated for their high surface area and unique electronic properties. The ScTeI monolayer, for instance, is predicted to have a direct band gap of 2.07 eV, which is within the visible light range, and its CBM and VBM are calculated to straddle the water redox potentials effectively [18]. The intrinsic built-in electric field in asymmetric Janus structures (e.g., I-Sc-Te) enhances the spatial separation of photogenerated electrons and holes, a key factor in improving photocatalytic efficiency [18].

Traditional Metal Oxides and Doping: Wide-bandgap semiconductors like anatase TiOâ‚‚ are historically important but primarily absorb UV light. Band structure engineering via co-doping is a common strategy to enhance their activity. For example, nonmetal-metal co-doping (e.g., (N, Ta) into TiOâ‚‚) can significantly raise the valence band edge and slightly increase the conduction band edge, narrowing the band gap from ~3.2 eV to 2.71 eV and shifting the absorption edge into the visible light region (457.6 nm) [21].

Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs): Organic semiconductors like COFs offer exceptional tunability at the molecular level. Studies on COF-OH-n series demonstrate that proton tautomerism, influenced by the number of β-ketoenamine linkages, can regulate the bandgap and band edge positions. COF-OH-3, with a bandgap of 2.28 eV and a suitable flat band potential of -0.62 V, achieved a high hydrogen evolution rate of 9.89 mmol gâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹, while other variants in the series with less optimal structures showed significantly lower performance [22].

Conjugated Organic Polymers: Organic polymer photocatalysts, such as those based on ITIC and BTIC units, can be designed for visible and even near-infrared (NIR) light activity. Engineering the π-linker between acceptor-donor-acceptor moieties (e.g., using difluorothiophene (ThF)) allows for tuning the bandgap, enhancing charge separation, and reducing recombination. PITIC-ThF polymer nanoparticles (Pdots) demonstrated remarkable hydrogen evolution rates of 279 µmol/h under visible light and 20.5 µmol/h under NIR light [23].

Niobate and Other Complex Oxides: Materials like Nb₃O₇(OH) are attractive for their chemical stability and energetic band positions. Doping with elements like Ta or Sb can effectively reduce its band gap (from 1.7 eV to ~1.2 eV), shift the optical absorption threshold into the visible region, and increase charge carrier mobility, enhancing its potential for visible-light-driven photocatalysis [24].

Table 2: Performance and Properties of Selected Photocatalytic Materials from Literature

| Material | Type | Band Gap (eV) | Key Feature / Strategy | Reported Performance (Hâ‚‚ Evolution Rate) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ScTeI Monolayer | 2D Janus | 2.07 (direct) | Built-in electric field, high carrier mobility anisotropy | Theoretical Solar-to-Hydrogen (STH) efficiency of 23.66% | [18] |

| (N, Ta)-co-doped TiOâ‚‚ | Doped Metal Oxide | 2.71 | Passivated co-doping narrows band gap | Absorption edge red-shifted to 457.6 nm (visible light) | [21] |

| COF-OH-3 | Covalent Organic Framework | 2.28 | Proton tautomerism for band tuning | 9.89 mmol gâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹ | [22] |

| PITIC-ThF Pdots | Conjugated Polymer | NIR-active | π-linker engineering (difluorothiophene) for charge separation | 279 µmol/h (visible); 20.5 µmol/h (NIR) | [23] |

| Ta-doped Nb₃O₇(OH) | Doped Niobate | 1.266 | Doping reduces gap, increases mobility | Promising potential for visible-light activity | [24] |

| CdO/Alâ‚‚SSe | Type-II Heterojunction | Tunable under strain | Strain engineering optimizes band alignment and gap | Enhanced visible light absorption predicted | [25] |

The Critical Role of Cocatalysts

Even with an ideal band structure, the recombination of charge carriers and slow surface reaction kinetics often limit efficiency. The use of cocatalysts is a pivotal strategy to overcome these challenges [19]. Cocatalysts are typically nanoparticles or single atoms deposited on the semiconductor surface that function as:

- Active Sites: Providing specific, low-energy pathways for the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) or oxygen evolution reaction (OER).

- Electron Sinks: Extracting photogenerated electrons from the semiconductor bulk, thereby reducing charge carrier recombination.

- Overpotential Reducers: Lowering the activation energy required for the redox reactions.

While noble metals (e.g., Pt, Au) are highly effective HER cocatalysts, research is increasingly focused on earth-abundant alternatives such as transition metal phosphides (Ni₂P), carbides (Mo₂C), dichalcogenides (MoS₂), and single-atom catalysts [19]. For instance, integrating Ni₂P with semiconductors like g-C₃N₄ has been shown to significantly enhance hydrogen evolution rates [19] [26].

Essential Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Advancements in this field are driven by robust experimental and computational protocols for synthesizing, modifying, and characterizing photocatalysts.

First-Principles Computational Analysis

Density Functional Theory (DFT) is a cornerstone for predicting the properties of new photocatalytic materials before synthesis. A standard computational workflow involves:

- Software and Code: Calculations are typically performed using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) [18] [26] [25].

- Exchange-Correlation Functional: The Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional within the Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) is commonly used for geometry optimization [18] [26]. For more accurate electronic property prediction (e.g., band gap), the Tran-Blaha modified Becke-Johnson (TB-mBJ) potential is often employed [24].

- Stability Verification:

- Phonon Spectrum Calculations: The absence of imaginary frequencies confirms the dynamic stability of the material's structure [18] [25].

- Ab initio Molecular Dynamics (AIMD) Simulations: Simulating the material at high temperatures (e.g., 300-500 K) for several picoseconds verifies its thermal stability [18] [26].

- Binding Energy/Formation Energy Calculation: A negative value indicates the structure is energetically favorable to form [18] [26].

- Property Calculation:

- Band Structure & Density of States (DOS): Used to determine the band gap (direct/indirect) and the atomic orbital contributions to the VB and CB [18] [24].

- Band Edge Alignment: The electrostatic potential is used to align the CBM and VBM with the vacuum level and the water redox potentials [18].

- Optical Properties: The complex dielectric function is calculated to determine the material's absorption coefficient and spectrum [24].

Experimental Synthesis and Evaluation Protocols

Experimental validation is crucial. A representative protocol for evaluating powdered photocatalysts is outlined below.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for photocatalyst development, from synthesis to performance testing.

Detailed Experimental Steps:

Photocatalyst Synthesis:

- Methods: Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) for 2D layers [18], wet-chemical synthesis for COFs [22] and g-C₃N₄ [20], Stille or Suzuki coupling for conjugated polymers [23], and solvothermal methods for metal oxides [24].

- Nanostructuring: Bulk polymers are often converted to polymer nanoparticles (Pdots) via a re-precipitation method to enhance water dispersity and reduce charge carrier diffusion length [23].

Material Characterization:

- Structural & Chemical: X-ray Diffraction (XRD) for crystallinity; Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy and X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) for functional groups and elemental composition.

- Morphological: Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) for visualizing morphology and nanostructure; BET analysis for specific surface area.

- Optoelectronic: UV-Vis Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy (DRS) to determine the band gap via Tauc plot; Photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy to assess charge carrier recombination; XPS Valence Band spectra to estimate the VBM position.

Photocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution Test:

- Reactor: A typical setup uses a Pyrex glass reactor with a top irradiation window, connected to a closed gas circulation system.

- Light Source: A 300 W Xe lamp is standard. Adjustable cut-off filters (e.g., λ > 420 nm for visible light, λ > 780 nm for NIR light) are used to select the excitation wavelength [23].

- Reaction Mixture: Typically, 10-50 mg of photocatalyst is dispersed in an aqueous solution (e.g., 100 mL) containing a sacrificial electron donor, such as triethanolamine (TEOA) or methanol, to consume the photogenerated holes and promote the HER [19] [23].

- Gas Analysis: The evolved gases are periodically sampled and quantified using gas chromatography (GC) equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD) and a molecular sieve column. Argon or Nitrogen is commonly used as a carrier gas.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Photocatalyst Research and Development

| Reagent/Material | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Sacrificial Agents | Electron donors that irreversibly consume photogenerated holes, enhancing electron availability for Hâ‚‚ evolution. | Triethanolamine (TEOA), Methanol, Ascorbic Acid used in performance testing [19] [23]. |

| Cocatalysts | Nanoparticles or single atoms loaded onto the semiconductor surface to provide active sites and facilitate charge separation. | Pt nanoparticles, Niâ‚‚P, MoSâ‚‚ for enhancing Hâ‚‚ evolution rates [19] [26]. |

| Precursor Salts | Source of metal and non-metal elements for the synthesis of inorganic or hybrid photocatalysts. | Niobium salts (for Nb₃O₇(OH)) [24], Cadmium salts (for CdO) [25]. |

| Organic Monomers | Building blocks for the synthesis of polymeric photocatalysts like COFs and conjugated polymers. | 2,4,6-tris(4-aminophenyl)-1,3,5-triazine and triformylbenzene derivatives for COF synthesis [22]. |

| π-linker Comonomers | Molecular units used to connect polymer building blocks, tuning conjugation, planarity, and charge transfer. | Phenyl (Ph), Thiophene (Th), Difluorothiophene (ThF) in ITIC/BTIC-based polymers [23]. |

| Surfactants | Amphiphilic molecules used to improve the dispersity of hydrophobic photocatalysts in aqueous solutions. | PS-PEG-COOH, Triton X-100 for forming stable polymer nanoparticle (Pdot) dispersions [23]. |

| Phosphine oxide, oxophenyl- | Phosphine Oxide, Oxophenyl-|CAS 55861-16-0 | Phosphine oxide, oxophenyl- is a reagent for synthesizing bioactive compounds and ligands. This product is for research use only (RUO). Not for personal use. |

| 2,5-Furandione, 3-pentyl- | 2,5-Furandione, 3-pentyl-|Research Chemical | Explore 2,5-Furandione, 3-pentyl- for industrial and scientific research. This reagent is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

The pursuit of efficient photocatalytic water splitting is a multidisciplinary endeavor centered on the precise control of semiconductor properties. The band gap and band edge positions are not merely parameters but the foundational design criteria that determine a material's thermodynamic feasibility. As evidenced by research on 2D Janus structures, doped metal oxides, COFs, and conjugated polymers, strategic engineering of these properties is paramount for activating visible-light response and achieving high solar-to-hydrogen conversion efficiencies. The integration of cocatalysts and the formation of heterojunctions further address kinetic limitations by enhancing charge separation and surface reaction rates. Continued advancement in computational prediction and sophisticated synthetic protocols, as detailed in this guide, provides a clear pathway for researchers to design and develop the next generation of high-performance photocatalysts for sustainable hydrogen production.

Photocatalytic hydrogen production represents a cornerstone in the quest for sustainable energy, directly converting solar energy into chemical fuel via water splitting. The fundamental process involves three critical steps: (1) light absorption by a semiconductor photocatalyst to generate electron-hole pairs, (2) charge separation and migration of these carriers to the catalyst surface, and (3) surface redox reactions for hydrogen evolution. Despite its conceptual elegance, the practical application is hampered by three intrinsic challenges that dictate the overall efficiency: rapid recombination of photogenerated charge carriers, limited light absorption capabilities of semiconductor materials, and slow surface reaction kinetics. These challenges are deeply interconnected; improvements in one area often impact the others, necessitating a holistic research approach. This guide delves into the core mechanisms of these limitations, presents current experimental methodologies for their investigation, and outlines advanced strategies being developed to overcome them, thereby framing the pathway toward more efficient solar hydrogen generation.

Challenge 1: Rapid Charge Carrier Recombination

The generation of electron-hole pairs upon photon absorption is futile if these charge carriers recombine before they can participate in surface reactions. This bulk and surface recombination represents a primary efficiency loss in photocatalysis.

Core Mechanisms and Quantitative Impact

Charge carrier recombination occurs through both radiative and non-radiative pathways, dissipating energy as heat or light. In pristine semiconductors like g-C3N4, this recombination is exceptionally fast, leading to poor photocatalytic performance for hydrogen generation despite favorable bandgap and visible light absorption [27]. The recombination rate is often modeled as a first-order kinetic process dependent on the density of trapped charges, competing directly with the desired charge transfer to substrates [28].

Experimental Analysis Protocols

Transient Absorption Spectroscopy (TAS) provides direct insight into charge carrier dynamics. This pump-probe technique involves:

- Pump Pulse: A short laser pulse (e.g., 355 nm, 150 ps) excites the photocatalyst, generating electron-hole pairs.

- Probe Pulse: A delayed white light continuum pulse monitors changes in absorption ((\Delta A)) at specific wavelengths, which are characteristic of photogenerated electrons (e.g., in the conduction band or trap states) and/or holes.

- Kinetic Tracing: The decay of (\Delta A) over time (from picoseconds to microseconds) is monitored. A multi-exponential function is typically fitted to the kinetic traces to extract lifetime components ((\tau1, \tau2, ...)), which represent the population decay of charge carriers due to recombination and trapping.

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) indirectly probes charge separation efficiency. The protocol involves:

- Electrode Preparation: Fabricating a working electrode by depositing a thin film of the photocatalyst onto a conductive substrate (e.g., FTO glass).

- Measurement: Applying a small AC voltage amplitude (e.g., 10 mV) over a frequency range (e.g., 0.1 Hz to 1 MHz) and measuring the current response in a suitable electrolyte.

- Data Analysis: The resulting Nyquist plot (Z'' vs. Z') is fitted with an equivalent circuit model. A smaller arc radius indicates lower electron transfer resistance, signifying more efficient charge separation and migration, as demonstrated in CdIn2S4/g-C3N4 heterostructures [27].

Advanced Mitigation Strategies

Heterojunction Engineering: Coupling two semiconductors with appropriate band alignment forces the spatial separation of electrons and holes.

- Type-II Heterojunction: Electrons migrate to the semiconductor with a lower conduction band, while holes move to the one with a higher valence band.

- Z-Scheme Heterojunction: Mimics natural photosynthesis, where electrons from the conduction band of one semiconductor recombine with holes from the valence band of another, leaving more reductive electrons and oxidative holes on the respective semiconductors.

The synthesis of CdIn2S4/g-C3N4 nanoheterostructures via a low-temperature precipitation method at 80°C resulted in a significant boost in Hâ‚‚ production (1062.1 μmol hâ»Â¹) compared to bare g-C3N4 (a 17-fold increase). Characterization confirmed the uniform distribution of CdIn2S4 floral microspheres on g-C3N4 sheets, which facilitates efficient electron transport across the interface [27].

Isotype Heterojunctions and Molecular Modification: Forming an isotype heterojunction between different morphologies or compositions of the same base material (e.g., g-C3N4) creates an internal electric field that drives charge separation. Further enhancement is achieved by modifying the carbon nitride structure with aromatic rings (e.g., benzene rings from N-phenylthiourea), which alters the electronic structure, enhances light absorption, and improves charge separation. This combined strategy yielded a photocatalyst with a hydrogen production rate 6.1 and 20 times higher than those of standard urea- and thiourea-based g-C3N4, respectively [29].

Table 1: Performance of Photocatalysts Engineered to Suppress Charge Recombination

| Photocatalyst | Synthesis Method | Hâ‚‚ Production Rate (μmol hâ»Â¹) | Enhancement Factor vs. Baseline | Key Characterization Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CdIn2S4/g-C3N4 (30% g-C3N4) | Low-temperature precipitation | 1062.1 | ~17x (bare g-C3N4) [27] | TEM (morphology), EIS (charge transfer) [27] |

| UTPh (g-C3N4 with benzene ring) | Thermal polycondensation | Specific rate not provided | 6.1x (U-g-C3N4), 20x (T-g-C3N4) [29] | DFT calculations, PL spectroscopy [29] |

| S–C3N4/ZnO hybrid | Not specified | Used for degradation | Enhanced degradation kinetics [30] | Scavenger studies confirmed charge separation [30] |

Challenge 2: Limited Light Absorption

A photocatalyst must efficiently harvest a significant portion of the solar spectrum to be practical. Many base semiconductors, like TiOâ‚‚ and ZnO, possess wide bandgaps (>3.0 eV), restricting their absorption to the ultraviolet region, which constitutes only about 5% of sunlight [31].

Core Mechanisms and Quantitative Impact

Light absorption is governed by the semiconductor's bandgap energy (Eð‘”) and its optical absorption coefficient. The inability to absorb visible light (constituting ~43% of solar energy) drastically limits the theoretical maximum solar-to-hydrogen efficiency. The atomic absorption cross-section of common semiconductors is low (~10â»Â¹â·â€“10â»Â¹â¶ cm²), meaning they capture photons poorly [31].

Experimental Analysis Protocols

Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy (DRS) & Bandgap Calculation: This is the standard method for determining the light absorption range and bandgap of powdered catalysts.

- Measurement: The photocatalyst powder is placed in a sample holder, and the instrument measures its diffuse reflectance (R) across a wavelength range (e.g., 200–800 nm).

- Data Transformation: The reflectance data is converted into the Kubelka-Munk function: ( F(R) = (1 - R)^2 / 2R ).

- Bandgap Determination: A Tauc plot is constructed by plotting ( [F(R) \cdot h\nu]^n ) versus the photon energy (( h\nu )), where ( n ) is 1/2 for direct bandgaps and 2 for indirect bandgaps. The bandgap is estimated by extrapolating the linear region of the plot to the x-axis. For instance, CdSe nanoparticles showed a bandgap of 2.55 eV via this method, confirming visible-light activity [32].

Advanced Mitigation Strategies

Bandgap Engineering via Doping and Composition Tuning: Introducing elemental dopants (metals/non-metals) or creating ternary compounds can create mid-gap states or shift the band edges to narrow the effective bandgap. For example, CdSe nanoparticles have a bandgap of ~2.55 eV, allowing them to function as potent visible-light photocatalysts, as utilized in the degradation of Methylene Blue [32].

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Enhancement: Decorating semiconductors with noble metal nanoparticles (Au, Ag) or certain metals like Bi, which exhibit SPR, dramatically enhances light absorption. SPR is the collective oscillation of conduction electrons upon interacting with light, creating intense localized electromagnetic fields and generating "hot electrons." The absorption cross-section of noble metals is 10â´â€“10âµ times greater than that of typical semiconductor atoms [31]. The SPR effect can be tuned from UV to near-infrared by modifying the size, shape, and aspect ratio of the metal nanoparticles, as demonstrated with Bi nanoparticles [31].

Synergistic Effects: Recent research explores coupling photocatalysis with other physical phenomena, such as piezoelectricity, to create internal fields that aid charge separation under mechanical stress, thereby improving the utilization of absorbed photons [33].

Table 2: Strategies for Enhancing Light Absorption in Photocatalysts

| Strategy | Mechanism | Example Material | Bandgap / Absorption Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ternary Chalcogenides | Intrinsic narrower bandgap and tunable composition for visible light absorption. | CdIn2S4 [27], CdSe [32] | CdSe: ~2.55 eV [32] |

| Elemental Doping | Introduces new energy levels within the bandgap, reducing the energy required for excitation. | S-doped g-C3N4 [30] | Absorbance extended further into visible region [30] |

| Plasmonic Enhancement | Metal nanoparticles act as light-harvesting antennas via SPR, generating hot electrons and enhancing the local electromagnetic field. | Au/TiOâ‚‚, Bi nanoparticles [31] | Tunable from UV to NIR (e.g., Bi nanoparticles) [31] |

| Molecular Modification | Modifying the electronic structure of polymers (like g-C3N4) with aromatic rings to extend the π-conjugation and redshift absorption. | Benzene-ring-modified g-C3N4 [29] | Enhanced visible light absorption [29] |

Challenge 3: Slow Surface Reaction Kinetics

Even when separated charges successfully reach the catalyst surface, the subsequent multi-step redox reactions can be sluggish, becoming the rate-limiting step. This is particularly true for the complex, multi-electron process of water reduction (2H⺠+ 2e⻠→ H₂).

Core Mechanisms and Kinetic Modeling

The surface reaction kinetics can be described by a holistic model considering the generation of reactive surface sites ((c_R^*)), their recombination, and the charge transfer to the substrate [28]. The general rate law is expressed as:

[r = \frac{\phi \cdot L{pa} \cdot k^* \cdot \theta \cdot c0}{\phi \cdot L{pa} + kr + k^* \cdot \theta \cdot c_0}]

where (\phi) is the quantum yield, (L{pa}) is the local volumetric rate of photon absorption, (k^*) is the normalized kinetic constant, (\theta) is the surface coverage, (c0) is the catalyst mass, and (k_r) is the recombination rate constant [28]. This model reveals two limiting regimes:

- Light-limited regime (( \phi L{pa} \ll kr + k^* \theta c_0 )): Reaction rate scales linearly with light intensity.

- Kinetic-limited regime (( \phi L{pa} \gg kr + k^* \theta c0 )): Reaction rate is independent of light intensity and governed by the intrinsic surface reaction rate ( k^* \theta c0 ) [28].

Experimental Analysis and Optimization Protocols

Kinetic and Thermodynamic Studies:

- Effect of Scavengers: Adding specific scavengers to the reaction mixture helps identify the primary reactive species. For example, the addition of isopropanol (scavenges •OH), EDTA-2Na (scavenges hâº), and benzoquinone (scavenges •Oâ‚‚â») during the degradation of Methylene Blue by CdSe revealed that photogenerated holes and hydroxyl radicals were the main active species [32].

- Reaction Order: The dependence of the reaction rate on substrate concentration is determined. The photocatalytic degradation of MB by CdSe nanoparticles followed a pseudo-first-order kinetic model [32].

- Thermodynamics: Parameters like activation energy (Ea), enthalpy (ΔH), and entropy (ΔS) of activation are calculated from experiments at different temperatures. For CdSe, the degradation of MB was found to be spontaneous and endothermic [32].

Response Surface Methodology (RSM): This statistical technique optimizes complex processes by modeling the interaction of multiple variables.

- Design: A Central Composite Design (CCD) is created with independent variables (e.g., pH, pollutant concentration, catalyst dosage, time).

- Experimentation: Experiments are run according to the design matrix.

- Modeling & Optimization: A quadratic polynomial model is generated via ANOVA to predict the response (e.g., degradation efficiency). This model is used to find the optimum conditions. For instance, RSM optimized the degradation of Methylene Blue using CdSe to ~92.8% at pH=8, [MB]=20 mgLâ»Â¹, dosage=0.02 g/50 mL, and time=20 min [32].

Advanced Mitigation Strategies

Co-catalyst Loading: Depositing small amounts of noble metals (Pt, Au) or non-precious metals (Ni, MoSâ‚‚) acts as a reaction hub, lowering the activation energy for Hâ‚‚ evolution by providing favorable adsorption sites for protons and facilitating electron transfer.

Surface Area and Morphology Control: Creating nanostructures with high surface area (e.g., porous networks, 2D nanosheets, 3D hierarchical structures) increases the density of active sites. The synthesized CdSe nanoparticles, for example, had a specific surface area of 26.71 m² gâ»Â¹, providing a high active surface for reactions [32].

Defect Engineering and Functionalization: Introducing surface defects (e.g., S-vacancies in CdIn2S4) or functional groups can act as specific trapping sites for reactants, enhancing surface coverage ((\theta)) and the reaction rate constant ((k^*)) [28].

Diagram 1: Kinetic Analysis Workflow for Surface Reactions

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Photocatalyst Research and Evaluation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Graphitic Carbon Nitride (g-C3N4) | Metal-free, visible-light-active semiconductor; serves as a base material for creating heterojunctions. | Bulk preparation by thermal polycondensation of melamine at 550°C [27]. |

| Ternary Chalcogenides (e.g., CdIn2S4, CdSe) | Visible-light absorbers with tunable band structures for forming heterojunctions or acting as primary catalysts. | CdIn2S4/g-C3N4 heterostructures for Hâ‚‚ production [27]; CdSe for dye degradation [32]. |

| Noble Metal Salts (e.g., H₂PtCl₆, HAuCl₄) | Precursors for depositing co-catalysts (Pt, Au) or plasmonic nanoparticles to enhance charge separation and surface reactions. | Pt-edged Au nanoprisms for direct H₂ production [31]. |

| Scavenger Compounds (Isopropanol, EDTA, Benzoquinone) | To quench specific reactive species (•OH, hâº, •Oâ‚‚â») and elucidate the dominant reaction mechanism in photocatalytic tests. | Mechanistic study for CdSe-mediated MB degradation [32]. |

| Sacrificial Agents (e.g., Methanol, Triethanolamine) | Electron donors that irreversibly consume photogenerated holes, thereby suppressing recombination and accelerating the half-reaction of Hâ‚‚ evolution. | Used in Hâ‚‚ production tests to evaluate reduction capability [27] [29]. |

| 3-Methylocta-2,6-dienal | 3-Methylocta-2,6-dienal|CAS 56522-83-9 | 3-Methylocta-2,6-dienal (CAS 56522-83-9) is a high-purity chemical for research. This product is For Research Use Only and not for human or veterinary diagnostics or therapeutic use. |

| Benzothiazole hydrochloride | Benzothiazole Hydrochloride|Research Chemical | High-purity Benzothiazole Hydrochloride for research. Explore applications in neuroscience, antimicrobial, and anticancer studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

The interconnected challenges of charge recombination, limited light absorption, and slow surface kinetics form the central triad of bottlenecks in photocatalytic hydrogen production. As detailed in this guide, a deep understanding of the underlying mechanisms, coupled with advanced characterization and kinetic modeling, is essential for progress. The most promising strategies involve integrated materials design, such as constructing heterojunctions for charge separation, employing bandgap engineering and plasmonics for broad-spectrum light harvesting, and engineering surfaces with co-catalysts for accelerated reaction rates. Future advancements will likely rely on interdisciplinary synergies—combining photocatalysis with other fields like piezoelectronics and thermocatalysis—and the increased use of AI-driven materials discovery and multi-scale reactor design to translate laboratory breakthroughs into scalable, economically viable technology for sustainable hydrogen production [33].

Advanced Materials and Reactor Designs for Enhanced Hydrogen Evolution

The escalating global energy crisis and environmental degradation underscore the urgent need for sustainable and clean energy sources. Hydrogen, with its high energy density of 122–143 MJ/kg and zero carbon emissions upon combustion, is widely regarded as a cornerstone of the future clean energy landscape [34] [35]. Among the various methods for hydrogen production, photocatalytic water splitting, which directly converts solar energy into chemical energy stored in hydrogen, presents a profoundly promising and environmentally friendly strategy [34] [36]. This process leverages semiconductor photocatalysts, which absorb photons with energy equal to or greater than their bandgap, exciting electrons from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB). This generates electron-hole pairs that drive the redox reactions of water: the reduction of protons to H₂ at the electron-rich sites and the oxidation of water to O₂ at the hole-rich sites [36] [35].

The fundamental challenge lies in developing photocatalysts that are highly efficient, stable, cost-effective, and responsive to visible light, which constitutes a significant portion of the solar spectrum. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of three core photocatalyst families central to advancing this field: Metal Oxides (exemplified by TiO₂ and CoO modifications), Metal Sulfides (such as CdS and MoS₂), and Metal-Free Semiconductors (notably g-C₃N₄). We will delve into their fundamental mechanisms, recent performance enhancements, and detailed experimental protocols, framing the discussion within the broader context of basic research on photocatalytic hydrogen production mechanisms.

Fundamental Mechanisms and Material Design

The overall efficiency of a photocatalyst is governed by a sequence of critical steps, and material design strategies aim to optimize each one. The process can be broken down into: 1) Photon Absorption, where the catalyst must absorb incident light to generate electron-hole pairs—this requires a bandgap ideally between 1.8 eV and 2.2 eV for optimal visible light utilization [35]; 2) Charge Separation and Migration, where the photogenerated electrons and holes must separate and move to the catalyst surface without recombining; and 3) Surface Redox Reactions, where the charges participate in the hydrogen and oxygen evolution reactions (HER and OER) [35]. The energy positions of the CB and VB are crucial; the CB minimum must be more negative than the Hâº/Hâ‚‚ reduction potential (0 V vs. NHE, pH=7), and the VB maximum must be more positive than the Hâ‚‚O/Oâ‚‚ oxidation potential (1.23 V vs. NHE, pH=7) [37].

A primary obstacle is the rapid recombination of photogenerated electron-hole pairs, which occurs on a timescale of femtoseconds, far faster than the surface redox reactions (picoseconds to nanoseconds) [37]. To address this, researchers have developed sophisticated material engineering strategies, which are visually summarized in the workflow below.

The following section provides a comparative analysis of the three photocatalyst families based on the design principles outlined above.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key Photocatalyst Families

| Photocatalyst Family | Representative Materials | Bandgap (eV) | Key Advantages | Inherent Challenges | Primary Enhancement Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Oxides | TiOâ‚‚, CoO-modified TiOâ‚‚ | ~3.2 (Anatase TiOâ‚‚) [36] | Excellent chemical stability, non-toxicity, low cost [36] [38] | Wide bandgap (UV-light only), rapid charge recombination [36] [38] | Doping (metal/non-metal), heterojunctions, co-catalyst loading (Ru, Co, Ni) [36] [38] |

| Metal Sulfides | CdS, MoSâ‚‚, ZnS | ~2.4 (CdS) [39] [34] | Narrow bandgap (visible light response), suitable band positions for reduction [34] [37] | Susceptibility to photocorrosion, high charge recombination rate [39] [34] [37] | Heterostructure building, cocatalyst loading, morphology control, introducing S vacancies [39] [34] |

| Metal-Free Semiconductors | g-C₃N₄ | ~2.7 [40] [41] [35] | Visible light response, metal-free, low cost, high thermal/chemical stability [40] [41] [35] | High charge carrier recombination, low surface area, insufficient quantum efficiency [40] [41] [35] | Elemental doping, nanostructure design, heterojunction construction, creating porous structures [41] [35] |

Metal Oxide Photocatalysts

Titanium Dioxide (TiOâ‚‚)

TiOâ‚‚ has been a benchmark photocatalyst since the pioneering work of Fujishima and Honda. Its anatase phase, with a bandgap of ~3.2 eV, is highly active but only under UV light, which accounts for a mere ~4% of the solar spectrum [36]. A prominent strategy to enhance its activity is the loading of metal co-catalysts, which serve as electron sinks and active sites for the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction (HER).

Experimental Protocol: Impregnation Loading of Co-catalysts on TiOâ‚‚ [38]

- Solution Preparation: Suspend 1 gram of TiO₂ nanoparticles (commercially available from suppliers like Acros Organics) in 3 mL of deionized water. To this suspension, add the required volume of an aqueous metal precursor solution (e.g., RuCl₃·2H₂O, Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, or Co(NO₃)₂·6H₂O) to achieve the target loading (e.g., 0.05–1 wt% for Ru, 0.1–1 wt% for Co or Ni).

- Impregnation and Drying: Stir the mixture vigorously with a glass rod and sonicate to ensure homogeneity. The suspension is then placed in an alumina crucible over a hot water bath with constant stirring until complete dryness is achieved.

- Reduction Treatment: Transfer the dried powder to a tube furnace. Purge the system with Argon gas (99.99%) at a flow rate of 100 mL/min for 15 minutes. Subsequently, switch the gas flow to Hydrogen (99.99%) at 10 mL/min and raise the furnace temperature to 200°C at a ramp rate of 10°C/min. Maintain this temperature for 1 hour under H₂ flow to reduce the metal ions to their zero-valent state.

- Cooling and Storage: Allow the furnace to cool naturally under the continued H₂ flow. The final catalyst, denoted as, for example, 0.1Ru–TiO₂ (Imp), can be stored in an inert atmosphere.

Performance Data: The hydrogen evolution rate (HER) is highly dependent on the co-catalyst. For instance, 0.1 wt% Ru–TiOâ‚‚ prepared via impregnation achieved an initial rate of 23.9 mmol hâ»Â¹ gâ»Â¹, outperforming 0.3 wt% Co–TiOâ‚‚ (16.55 mmol hâ»Â¹ gâ»Â¹) and 0.3 wt% Ni–TiOâ‚‚ (10.82 mmol hâ»Â¹ gâ»Â¹) under UV light using methanol as a sacrificial agent [38]. This demonstrates that transition metals like Co and Ni can serve as cost-effective alternatives to noble metals like Ru.

Cobalt Oxide (CoO) and Related Modifications

While less common as a standalone photocatalyst, cobalt, particularly in mixed-valence states (Co²âº/Co³âº), plays a critical role as a co-catalyst. In a Co-Ni/TiOâ‚‚ system, cobalt sites were found to act as hole traps, promoting the Oxygen Evolution Reaction (OER) and creating a synergistic effect with nickel, which served as an electron sink for the HER [42]. This dual functionality facilitated spatial charge separation, significantly suppressing recombination and leading to a high HER of 448 μmol hâ»Â¹ gâ»Â¹, substantially higher than single-metal-loaded or pristine TiOâ‚‚ [42].

Metal Sulfide Photocatalysts

Cadmium Sulfide (CdS) and Molybdenum Disulfide (MoSâ‚‚)

CdS possesses a favorable bandgap (~2.4 eV) for visible light absorption and suitable conduction band potential for proton reduction. However, it suffers from severe photocorrosion, where photogenerated holes oxidize S²⻠to SⰠ[39] [37]. Constructing heterostructures with MoS₂, a highly active co-catalyst for HER, is a widely successful strategy to mitigate this and enhance charge separation.

MoSâ‚‚ exists in semiconducting (2H) and metallic (1T) phases. The 1T phase exhibits superior conductivity and a higher density of active sites but is metastable. Heterostructures incorporating the 1T phase are therefore highly desirable [39].

Experimental Protocol: Two-Step Solvothermal Synthesis of CdS@1T/2H MoSâ‚‚ Nanorod Clusters [39]

- Synthesis of CdS Nanorod Clusters:

- Dissolve Cadmium nitrate tetrahydrate (Cd(NO₃)₂·4H₂O) and thiourea in a mole ratio of 1:3 in an aqueous solution of Ethylenediamine (EDA) (1:1 vol ratio).

- Transfer the homogeneous mixture to a Teflon-lined autoclave and heat at 180°C for 12 hours.

- Cool naturally, collect the resulting orange product (CdS nanorod clusters) via centrifugation, wash, and dry.

- Construction of CdS@1T/2H MoSâ‚‚ Heterostructure:

- Disperse 0.15 g of the as-prepared CdS in an ethanol aqueous solution by sonication for 10 min and vigorous stirring for 1 hour.

- Add appropriate amounts of ammonium tetrathiomolybdate ((NH₄)₂MoS₄) and thioacetamide (CH₃CSNH₂) as Mo and S sources, respectively, to the above suspension.

- Transfer the final mixture to an autoclave and conduct a second solvothermal reaction at 200°C for 24 hours.

- Collect the final product by centrifugation, wash thoroughly with water and ethanol, and dry.

Key Findings: The resulting material featured ultrathin 1T/2H MoSâ‚‚ nanosheets tightly wrapped around CdS nanorod clusters. The presence of rich sulfur vacancies and the metallic 1T-MoSâ‚‚ phase drastically promoted electron transport and separation at the intimate interface, leading to outstanding photocatalytic Hâ‚‚ production performance under visible light [39].

Table 2: Performance of Advanced Metal Sulfide and g-C₃N₄ Based Photocatalysts

| Photocatalyst | Co-catalyst/Modification | Light Source | Sacrificial Agent | Hydrogen Evolution Rate | Key Enhancement Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CdS Nanorod Clusters [39] | 1T/2H MoSâ‚‚ wrapping | Full-spectrum | Lactic Acid | Outstanding performance (specific value not provided) | Rich S-vacancies, metallic 1T phase, intimate heterojunction |

| g-C₃N₄ (Optimized) [35] | Elemental Doping & Nanostructuring | Visible Light | Not Specified | 104-fold increase vs. pristine | Enhanced charge separation, expanded surface area |

| g-C₃N₄ (Optimized) [35] | Heterostructure Construction | Visible Light | Not Specified | 100-fold increase vs. pristine | Improved charge carrier separation, preserved redox properties |

| TiOâ‚‚ [42] | Co and Ni co-loading | Simulated Solar | Not Specified | 448 μmol hâ»Â¹ gâ»Â¹ | Synergistic redox couples (Co²âº/Co³âº, Ni²âº/Ni³âº) for spatial charge separation |

Metal-Free Semiconductors: Graphitic Carbon Nitride (g-C₃N₄)

Graphitic carbon nitride (g-C₃N₄) is a metal-free polymer semiconductor that has generated significant interest due to its visible-light-responsive bandgap (~2.7 eV), high thermal and chemical stability, ease of synthesis, and composition from earth-abundant elements [40] [41] [35]. However, its pristine form suffers from a high recombination rate of photogenerated charge carriers and a relatively low surface area.

Enhancement Strategies and Performance: Sophisticated engineering strategies have led to remarkable improvements. Elemental doping (e.g., with P, S, B) can modify the electronic structure to improve charge separation. Nanostructure design, such as creating porous or hollow structures, can expand the surface area by a factor of 26 and extend the fluorescence lifetime of charge carriers by 50%, providing more active sites [35]. Most effectively, heterostructure construction with other semiconductors (e.g., ZnO, CdS, MoSâ‚‚, or metals) can form junctions that powerfully drive the spatial separation of electrons and holes, resulting in a dramatic hundredfold surge in hydrogen generation performance [41] [35]. The DOT script below visualizes this charge transfer process in a heterojunction system.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The experimental protocols and enhancement strategies discussed rely on a core set of chemical reagents and materials. The following table details these essential components and their functions in photocatalytic hydrogen production research.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Photocatalyst Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Precursors | Source of metal co-catalysts for loading onto semiconductors. | RuCl₃·2H₂O, Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, Co(NO₃)₂·6H₂O for loading on TiO₂ [38]. |

| Semiconductor Substrates | The primary photocatalyst material. | TiO₂ nanoparticles (commercially available) [38]; Synthesized CdS nanorods [39]; Synthesized g-C₃N₄ [35]. |

| Sulfur Sources | Reactants for the synthesis of metal sulfide photocatalysts. | Thiourea, thioacetamide (CH₃CSNH₂), ammonium tetrathiomolybdate ((NH₄)₂MoS₄) [39]. |

| Structure-Directing Agents | Used in solvothermal synthesis to control the morphology and structure of nanomaterials. | Ethylenediamine (EDA) for the synthesis of CdS nanorod clusters [39]. |

| Sacrificial Agents (Hole Scavengers) | Electron donors that consume photogenerated holes, thereby suppressing charge recombination and photocorrosion. | Methanol, lactic acid [39] [38]. |

| Inert Gases | To create an oxygen-free atmosphere, preventing unwanted oxidative side reactions and ensuring accurate Hâ‚‚ measurement. | Argon (Ar) gas for purging reaction systems [38]. |

| Reducing Gases | For the thermal reduction of metal precursors to their active metallic state during catalyst synthesis. | Hydrogen (Hâ‚‚) gas [38]. |

| 1,5-Dibromopent-2-ene | 1,5-Dibromopent-2-ene | |

| Pentanal, 2-methyl-, (R)- | Pentanal, 2-methyl-, (R)-, CAS:53531-14-9, MF:C6H12O, MW:100.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |