Understanding Negative Frequencies in Phonon Spectra: Causes, Implications, and Solutions for Materials Research

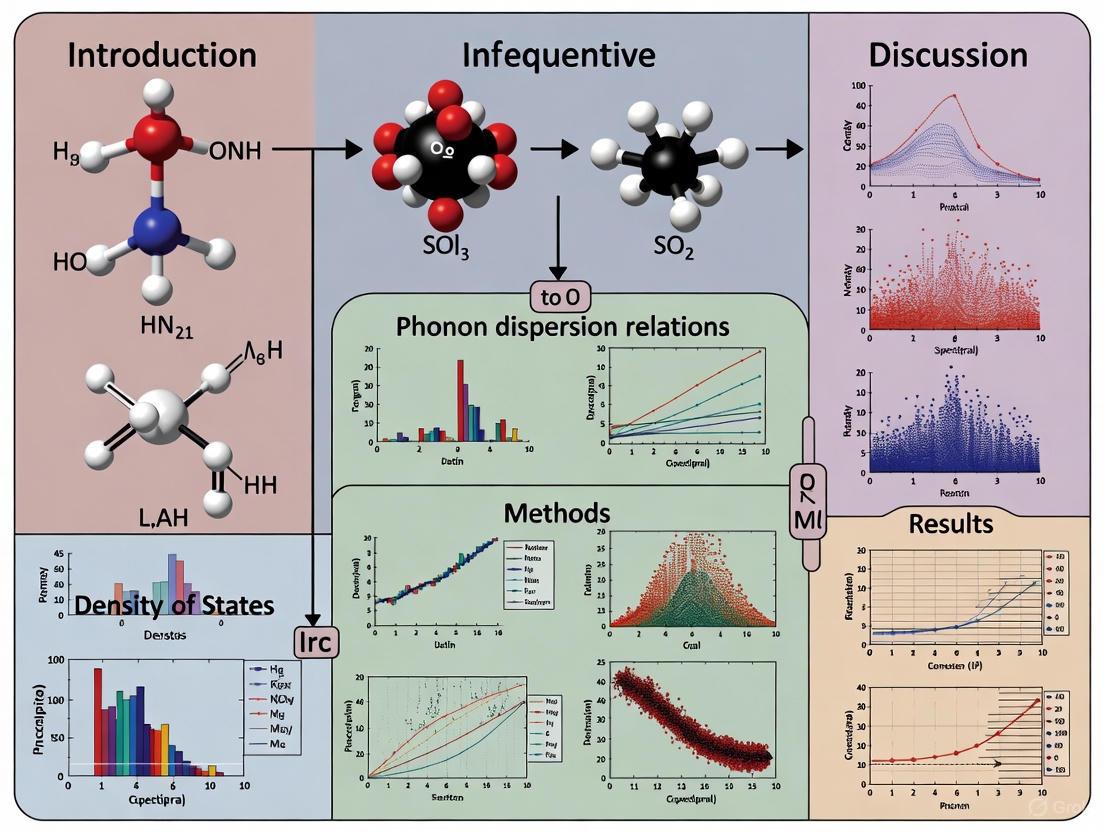

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of negative frequencies (imaginary phonon modes) in phonon spectra, a phenomenon critical for assessing material stability and properties.

Understanding Negative Frequencies in Phonon Spectra: Causes, Implications, and Solutions for Materials Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of negative frequencies (imaginary phonon modes) in phonon spectra, a phenomenon critical for assessing material stability and properties. We explore the fundamental physical causes, including structural instabilities and numerical artifacts, and detail advanced computational methodologies from density functional perturbation theory (DFPT) to machine learning potentials for accurate phonon prediction. The content covers practical troubleshooting strategies for resolving unphysical negative frequencies and outlines rigorous validation protocols through comparison with experimental data like Raman and IR spectroscopy. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review connects theoretical insights with practical applications in material design and biomedical research.

Unstable Lattices and Imaginary Modes: The Fundamental Physics of Negative Phonon Frequencies

In computational materials science, the appearance of negative frequencies (often reported as imaginary frequencies) in phonon spectra is a significant finding. While sometimes dismissed as a numerical artifact, they most frequently serve as a critical indicator of structural instability. This guide provides researchers with a clear framework to diagnose the root causes of this issue and implement effective solutions.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing the Root Cause of Negative Frequencies

| Observation | Most Likely Cause | Supporting Evidence | Secondary Checks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative bands in the phonon spectrum, particularly at or near the Gamma point ( [1]). | Unrelaxed residual stress in the structure. The system is at a saddle point and can gain energy by relaxing further ( [1]). | A preceding geometry optimization converged based on forces but not on stress. | Check the optimization log; confirm that stress tensor components are not converged to the desired tolerance. | |

| Isolated small negative frequencies for acoustic modes very close to the Γ-point (e.g., | q | < 0.05) ( [2]). | Numerical precision issue, often linked to an insufficiently dense k-point or q-point grid ( [2]). | Verify the breaking of the Acoustic Sum Rule (ASR); a large breaking signals poor convergence ( [2]). |

| Widespread negative frequencies across multiple wavevectors ( [2]). | A real structural instability, indicating the calculated structure is not a local minimum on the potential energy surface ( [2]). | The negative frequencies are large in magnitude and persist after thorough optimization and convergence tests. | Analyze the phonon eigenvectors to identify the atomic displacements associated with the unstable mode. | |

| Negative frequencies that disappear when calculations are performed at higher temperatures ( [3]). | Anharmonic effects that are not captured in the standard harmonic approximation used in the phonon calculation ( [3]). | The instability is temperature-dependent. | Confirm that the simulation parameters (e.g., TMAX, DT) are appropriate for capturing the system's behavior at the relevant temperature ( [3]). |

Guide 2: Resolving Negative Frequencies

| Problem | Solution Protocol | Key Parameters to Adjust | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unrelaxed Residual Stress | Perform a stress-relaxed geometry optimization ( [1]). | 1. Set a maximum stress tolerance (e.g., 0.0001 eV/ų) [1].2. Uncheck fixed lattice constraints to allow cell vectors to relax. | The negative bands disappear from the phonon spectrum, confirming a stable structure. |

| Numerical Precision Issues | Improve the convergence of key parameters ( [2]). | 1. Increase the density of the k-point and q-point grids.2. Increase the plane-wave cutoff energy.3. Explicitly impose the Acoustic Sum Rule (ASR) during calculation. | Small, spurious negative frequencies near the Γ-point are eliminated. |

| Anharmonic Effects | Incorporate temperature-dependent parameters ( [3]). | Adjust temperature parameters in anharmonic calculations (e.g., in SCPH, set TMAX and DT to appropriate values) ( [3]). |

The phonon spectrum becomes stable at the temperature of interest. |

Diagram: Diagnostic workflow for negative frequencies in phonon spectra.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What exactly does a "negative frequency" in a phonon spectrum represent? In the harmonic approximation used for standard phonon calculations, the calculated frequency is proportional to the square root of the eigenvalue of the dynamical matrix. A negative frequency (often reported as an imaginary frequency, iω) signifies that this eigenvalue is negative, which points to a curvature of the potential energy surface that is negative along the corresponding vibrational mode. This indicates that the atomic structure is unstable and can distort along that particular mode to reach a lower energy state ( [1] [2]).

Q2: I have performed a force optimization on my structure. Why do I still have negative frequencies? A force-only optimization ensures that the atoms are at positions where the net force is zero, but it does not guarantee that the cell's stress is minimized. Your structure may still be under significant internal stress, placing it at a saddle point. The solution is to perform a second optimization that includes stress relaxation, allowing the cell vectors to change to release this stress ( [1]).

Q3: When can I ignore small negative frequencies? Small, isolated negative frequencies (e.g., < 10 cmâ»Â¹) that appear only for acoustic modes very close to the Brillouin zone center (Γ-point) are often a numerical artifact. They can result from incomplete convergence of the k-point grid or a slight breaking of the Acoustic Sum Rule (ASR). You should first try to improve the numerical precision of your calculation before concluding there is a physical instability ( [2]).

Q4: My system is known to be stable, but my calculation shows negative frequencies. What is wrong? The most likely culprit is the calculation methodology itself. First, verify that your structure is fully optimized with respect to both forces and stress. Then, systematically check the convergence of key computational parameters, especially the k-point grid density and the plane-wave energy cutoff. Using under-converged parameters is a common source of spurious instabilities ( [2]).

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Stress-Relaxed Geometry Optimization for Stable Phonons

This protocol is essential when negative frequencies are caused by unrelaxed residual stress in the system ( [1]).

Methodology:

- Initial Configuration: Begin with your atomic structure.

- Calculator Setup: Select an appropriate computational engine (e.g., ForceField, DFT, or Semi-Empirical) and potential/functional.

- Optimization Block: In the optimization script, define the

OptimizeGeometrytask with the following critical adjustments:- Set a stringent maximum force tolerance (e.g., 0.01 eV/Ã…).

- Set a maximum stress tolerance (e.g., 0.0001 eV/ų).

- Ensure the cell is allowed to relax in the necessary directions by unconstraining the corresponding lattice vectors.

- Phonon Analysis: Sequentially add the

PhononBandstructureandPhononDensityOfStatesanalysis objects to the script. - Execution and Validation: Run the calculation. A successful run will yield a phonon band structure without negative bands.

Diagram: Workflow for stress-relaxed geometry optimization.

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Phonon Calculation with DFPT

This protocol, based on high-throughput Density Functional Perturbation Theory (DFPT), is used for large-scale screening and requires careful attention to numerical settings to avoid artifacts ( [2]).

Methodology:

- DFPT Calculation: The interatomic force constants in reciprocal space are calculated using DFPT on a regular grid of q-points.

- Sum Rule Imposition: The Acoustic Sum Rule (ASR) and Charge Neutrality Sum Rule (CNSR) are explicitly imposed during the Fourier interpolation process to correct for potential numerical drift and ensure physical results.

- Convergence Validation: The calculation's reliability is estimated by checking the breaking of the ASR and CNSR before imposition. A large breaking indicates a need for a higher plane-wave cutoff or denser q-point grid.

- Instability Flagging: The database automatically flags materials with likely real instabilities (widespread negative frequencies) versus those with potential numerical issues (small negatives near Γ).

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational "reagents" and parameters essential for stable and accurate phonon calculations.

| Item/Parameter | Function & Explanation | Usage Note |

|---|---|---|

| Stress Tensor Tolerance | A target value (e.g., maximum stress = 0.0001 eV/ų) that, when met, indicates the crystal lattice has relaxed to a low-stress state, crucial for eliminating stress-induced negative frequencies ( [1]). |

Must be explicitly set in the optimization block. Force-only optimization is insufficient. |

| k-point / q-point Grid Density | Defines the sampling resolution in reciprocal space. An insufficiently dense grid is a common source of small, spurious negative frequencies near the Γ-point ( [2]). | Use a Γ-centered grid with a density of ~1500 points per reciprocal atom as a starting point ( [2]). |

| Acoustic Sum Rule (ASR) | A physical rule that requires the sum of force constants for acoustic modes at Γ to be zero. Its imposition corrects numerical errors that can cause these modes to be non-zero ( [2]). | Ensure this option is enabled in your phonon calculation parameters. A large ASR breaking before imposition signals poor convergence. |

| Temperature Parameters (TMAX, DT) | In anharmonic calculations, these parameters control the temperature range for sampling the potential energy surface. Proper setting can resolve instabilities arising from anharmonic effects ( [3]). | Adjust based on the physical temperature of interest for your system. |

| Dipotassium hydroquinone | Dipotassium Hydroquinone|4554-13-6|Research Chemical | Dipotassium hydroquinone (CAS 4554-13-6) is a high-reactivity salt for organic synthesis and polymer research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Einecs 299-216-8 | Einecs 299-216-8, CAS:93857-83-1, MF:C33H39N3O6S2, MW:637.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions

What does a "negative frequency" in a phonon spectrum mean? In computational materials science, a negative frequency (often reported as an imaginary frequency) results from solving the dynamical matrix for a crystal structure and obtaining a negative eigenvalue. This indicates that the atomic configuration is not in a true energy minimum and is unstable. The corresponding vibrational mode shows a path along which atoms will spontaneously displace to lower the system's total energy, often initiating a phase transition [2].

My DFPT calculation shows small negative frequencies near the Γ-point. Is this a real instability? Not necessarily. Small negative frequencies for acoustic modes very close to the Brillouin zone center (Γ-point) can often be a numerical artifact rather than a sign of a real structural instability. They can be associated with insufficient convergence with respect to parameters like the k-point or q-point grid density. In such cases, recalculating with a denser grid is recommended. A real instability is typically characterized by significant imaginary frequencies over broader regions of the Brillouin zone [2].

How do I distinguish a computational artifact from a real physical instability? Our database employs specific flags to help identify potential numerical issues. A key indicator is the presence of negative frequencies only in the very small wavevector region (e.g., 0 < |q| < 0.05 in fractional coordinates). Materials exhibiting likely real instabilities will show negative (imaginary) frequencies across larger portions of the high-symmetry lines [2].

What are the Acoustic Sum Rule (ASR) and Charge Neutrality Sum Rule (CNSR), and why are they important? The Acoustic Sum Rule (ASR) arises from the invariance of total energy with respect to crystal translation and requires that the acoustic modes at the Γ-point be zero. The Charge Neutrality Sum Rule (CNSR) ensures that the Born effective charges in a unit cell sum to zero. Significant breaking of these rules after calculation can indicate a lack of numerical convergence, for instance, with respect to the plane-wave cutoff energy. These rules are often explicitly imposed during data processing to improve the physical correctness of the results [2].

Can I still use results from a calculation that has broken sum rules or small imaginary frequencies? Yes, with caution. For large-scale screening purposes, results obtained after imposing the ASR and CNSR can still provide useful and accurate information away from problematic q-point regions. However, for definitive analysis of a specific material's stability, achieving full numerical convergence is essential [2].

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Phonon Calculation Issues

This guide outlines a systematic approach to diagnosing and resolving common problems in Density Functional Perturbation Theory (DFPT) phonon calculations.

Phase 1: Understand and Reproduce the Problem

- Identify the Symptom: Precisely characterize the issue. Is it the presence of imaginary frequencies? If so, note their magnitude and location in the Brillouin zone. Are there error messages related to convergence or symmetry?

- Gather Data: Collect all relevant computational files: the input structure, calculation parameters (INCAR, PWSCF, etc.), output logs, and the generated phonon band structure.

- Reproduce the Issue: Verify the problem by checking the calculation on a standardized test system if possible. Ensure the issue is reproducible and not a one-time computational error.

Phase 2: Isolate the Root Cause

Simplify the problem by systematically checking parameters. Change only one variable at a time to pinpoint the exact cause.

- Check for Imaginary Frequencies: The presence of imaginary frequencies suggests a structural instability. Your initial task is to determine if this is physical or numerical.

- Verify k-point and q-point Grids: A grid density that is too low is a common cause of spurious instabilities, especially near the Γ-point. Consult literature or high-throughput frameworks for recommended grid densities for your material [2].

- Assess Plane-Wave Cutoff Energy: Check if the kinetic energy cutoff is sufficient. A low cutoff can lead to poor convergence of forces and the dynamical matrix.

- Examine Sum Rule Breaking: Evaluate the breaking of the Acoustic Sum Rule (ASR) and Charge Neutrality Sum Rule (CNSR). A large breaking can signal a lack of convergence. For example, a flag is raised if the largest acoustic mode at Γ is >30 cmâ»Â¹ before imposing the ASR, or if the CNSR breaking is >0.2 [2].

Phase 3: Implement a Solution and Document

Based on the isolated cause, implement the appropriate fix.

- For Numerical Instabilities: Increase the k-point/q-point grid density or the plane-wave cutoff energy and rerun the calculation.

- For Physical Instabilities: If the instability persists with well-converged parameters, it is likely physical. Follow the atomic displacements of the unstable mode to find the lower-symmetry, stable phase of the material.

- Document the Resolution: Record the problem, root cause, and successful solution in your lab notes or a shared database. This creates a valuable resource for future troubleshooting and helps prevent recurring issues [4].

Phonon Calculation Diagnostics and Convergence Criteria

The following table summarizes key numerical indicators that help diagnose the quality and reliability of a phonon calculation [2].

| Diagnostic Indicator | Description | Acceptable Threshold | Corrective Action | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imaginary Frequencies near Γ-point | Small negative acoustic modes very close to | q | =0. | Only in region 0< | q | <0.05 | Increase k-point and q-point grid density. |

| Acoustic Sum Rule (ASR) Breaking | The degree to which acoustic modes at Γ are non-zero before rule imposition. | Largest acoustic mode < 30 cmâ»Â¹ | Increase plane-wave cutoff energy; ensure proper DFT structural relaxation. | ||||

| Charge Neutrality Sum Rule (CNSR) Breaking | The deviation of the sum of Born effective charges from zero. | max < 0.2 | Increase plane-wave cutoff energy. | ||||

| Real Imaginary Modes | Significant imaginary frequencies over broader regions of the Brillouin zone. | Any significant value | Likely a physical instability. Displace structure along the soft mode to find a stable phase. |

Workflow for Analyzing Phonon Instabilities

The diagram below outlines the logical workflow for diagnosing and responding to imaginary frequencies in phonon spectra.

This table details key computational resources and data used in high-throughput phonon studies [2].

| Resource / Material | Function / Description | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| ABINIT Software Package | An open-source software suite for DFT and DFPT calculations. | Used to perform first-principles calculations of electronic structure and lattice dynamics (phonons). |

| PseudoDojo Pseudopotentials | A table of curated, high-quality norm-conserving pseudopotentials. | Provides the effective potentials for electron-ion interactions, crucial for accurate and efficient plane-wave calculations. |

| Materials Project (MP) Database | A free database of computed material properties for over 150,000 inorganic compounds. | Provides initial crystal structures and serves as a platform for sharing computed data, including phonon spectra. |

| Phonon Database (e.g., phonondb.mtl.kyoto-u.ac.jp) | A repository of pre-calculated phonon band structures and density of states. | Allows researchers to validate their own results and access phonon data without performing new calculations. |

| DFPT (Density Functional Perturbation Theory) | An efficient method for computing second-order derivatives of the total energy. | The core theoretical and computational framework for calculating phonon frequencies, Born effective charges, and dielectric tensors. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the Acoustic Sum Rules (ASR) and why are they important? The Acoustic Sum Rules (ASR) are mathematical constraints imposed on the interatomic force constants (IFCs) in a phonon calculation. They arise from the fundamental physical requirement of translational invariance; translating an entire infinite crystal by a small displacement should not change its internal energy or generate forces on the atoms. This leads to the condition that the three acoustic phonon modes at the Brillouin zone center (the Gamma point, q=0) must have zero frequency. The ASR ensures the conservation of total crystal momentum and is essential for obtaining physically meaningful phonon spectra [5] [6] [7].

2. I am not getting zero frequencies for my acoustic modes at Gamma. Why? This is a common issue in ab initio phonon calculations. The violation of the ASR is typically not a physical effect but an artifact of numerical approximations. The primary reasons include:

- Discreteness of the FFT grid: The use of a finite Fast-Fourier-Transform (FFT) grid is a major, irreducible source of ASR violation [5].

- Insufficient convergence: Inadequate convergence of key parameters, such as the threshold for self-consistency in the phonon calculation (

tr2_ph) or the ground-state electronic convergence (conv_thr), can significantly impact the quality of the dynamical matrix [5]. - Insufficient k-point sampling: A sparse grid of k-points in the electronic calculation can lead to inaccuracies in the force constants and the Born effective charges, breaking the sum rules [8]. If the non-zero acoustic frequencies are small, imposing the ASR on the dynamical matrix in post-processing usually yields excellent results [5] [7].

3. Why do I get negative (imaginary) phonon frequencies? Negative frequencies, representing imaginary phonon energies (ω² < 0), can signal two distinct scenarios:

- A numerical artifact: Poor convergence (of the SCF calculation, k-points, or FFT grid) or an imperfectly optimized atomic geometry can cause spurious imaginary frequencies. This is often the case for acoustic modes at Gamma or rotational modes of molecules [5] [7].

- A real physical instability: Imaginary frequencies at wavevectors other than Gamma can indicate a structural or dynamical instability, meaning the assumed atomic structure is not a true minimum on the potential energy surface and may undergo a phase transition [5] [6].

4. How can I enforce the Acoustic Sum Rule in my calculations? Most computational packages provide options to impose the ASR. The specific method depends on the code:

- In Quantum ESPRESSO: You can set the input variable

asr = .true.in theph.xinput file to enforce the sum rule on the dynamical matrix [7]. Alternatively, thedynmat.xtool can be used in post-processing with theasr='simple'option [8]. - In CASTEP: The keyword

phonon_sum_rule : TRUEcan be added to the parameter file to enforce the ASR [9]. - In ASE: The

acousticmethod of thePhononsclass can be called to restore the acoustic sum rule on the force constant matrix [10].

5. What are the rotational invariance conditions and why do they matter for low-dimensional materials? Beyond translational invariance, a crystal's potential energy should also be invariant under an infinitesimal rigid rotation, leading to the Born-Huang rotational invariance conditions. These conditions link the first-order and second-order IFCs [6]. They are particularly critical for low-dimensional (1D, 2D) materials. If rotational invariance is violated in the calculation, the flexural (out-of-plane) acoustic (ZA) phonon mode in 2D materials may display an incorrect linear dispersion at long wavelengths, instead of the physically correct quadratic dispersion. Ensuring both translational and rotational invariances is therefore essential for accurate phonon properties in low-dimensional systems [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Non-Zero Acoustic Modes at the Gamma Point

Problem: After a phonon calculation, the frequencies of the three acoustic modes at the Gamma point are not zero but have small, non-physical values.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Check convergence: Verify that your ground-state self-consistent field (SCF) calculation is tightly converged with respect to the plane-wave energy cutoff (

ecutwfc) and k-point grid [8]. - Check geometry: Confirm that your atomic positions are fully optimized, with forces on all atoms below a strict threshold (e.g., 10â»â¶ Ha/Bohr) [2].

- Inspect output: Look for warnings or large deviations from the ASR in your output files before any post-imposition.

Resolution Protocol:

- Impose ASR in the calculation: Activate the built-in ASR correction in your phonon code (e.g., in

ph.xor CASTEP) [9] [7]. - Post-process imposition: If your code does not impose the ASR during the main calculation, use a post-processing tool (e.g.,

dynmat.xin QE) to enforce it on the calculated dynamical matrix [8]. - Re-run with stricter parameters: If the problem persists, re-run your calculation with a denser FFT grid, a finer k-point sampling, and tighter convergence thresholds for both the SCF (

conv_thr) and phonon (tr2_ph) calculations [5] [8].

Issue 2: Appearance of Imaginary Frequencies

Problem: The phonon spectrum contains one or more modes with imaginary (negative) frequencies.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Locate the instability: Determine if the imaginary frequencies occur at the Gamma point or at other wavevectors. Gamma-point imaginary modes are more likely to be numerical artifacts, while those at other q-points may indicate a real instability [5].

- Check for rotational modes: For an isolated molecule, imaginary frequencies corresponding to rotational modes are common numerical artifacts and are difficult to eliminate completely [7].

- Verify structural optimization: Ensure the input structure is a true equilibrium configuration by re-examining the geometry optimization. An unoptimized structure is a common cause of imaginary modes.

Resolution Protocol:

- If a numerical artifact is suspected:

- If a physical instability is confirmed:

- The imaginary frequencies indicate that the current structure is unstable. You may need to investigate a different crystal structure or phase.

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Standard Workflow for Robust Gamma-Point Phonon Calculation

This protocol ensures a well-converged phonon calculation at the Gamma point, minimizing numerical errors related to sum rules.

Step 1: Rigorous Ground-State Calculation

- Method: Perform a self-consistent (SCF) calculation with

pw.x. - Key Parameters:

- Use a high plane-wave energy cutoff (

ecutwfc). Increasingecutrho(the charge density cutoff) can also help alleviate issues with acoustic modes [7]. - Employ a dense k-point grid for Brillouin zone sampling. A spacing of

0.07 Ã…â»Â¹or finer is often a good starting point [9]. - Converge the total energy and forces to very tight thresholds (e.g.,

conv_thr = 1.0d-10for energy, and all forces below10â»â¶ Ha/Bohr) [2] [8].

- Use a high plane-wave energy cutoff (

Step 2: Phonon Calculation with DFPT

- Method: Use

ph.xto perform a Density-Functional Perturbation Theory (DFPT) calculation at q=(0,0,0). - Key Parameters:

Step 3: Analysis and Validation

- Method: Analyze the output and dynamical matrix.

- Key Actions:

- Check the output for the frequencies of the acoustic modes. They should be very close to zero.

- Use a tool like

dynmat.xto visualize the normal modes and confirm the acoustic modes correspond to pure translations [8].

The logical flow and key decision points for a robust phonon calculation are summarized in the diagram below.

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Phonon Database Validation

Large-scale phonon calculations, as performed for materials databases, require automated procedures to ensure data quality. The methodology from the Materials Project provides a robust framework [2].

Step 1: Systematic Calculation with DFPT

- Software: ABINIT software package.

- Functional: PBEsol generalized gradient approximation (GGA).

- Pseudopotentials: Norm-conserving pseudopotentials from PseudoDojo.

- k-point and q-point sampling: Equivalent grids with a density of ~1500 points per reciprocal atom.

Step 2: Imposition of Invariance Conditions

- ASR and CNSR: The acoustic sum rule (ASR) and charge neutrality sum rule (CNSR) for Born effective charges are explicitly imposed during the Fourier interpolation of the dynamical matrix [2].

Step 3: Data Quality Flagging

- Flags are set to identify potentially problematic calculations:

- Flag 1: Acoustic mode at Γ > 30 cmâ»Â¹ before ASR imposition.

- Flag 2: Breaking of the CNSR (sum of Born charges > 0.2).

- Flag 3: Presence of negative frequencies very close to Γ (|q| < 0.05), which often indicates poor convergence rather than a real instability [2].

Table 1: Convergence Parameters for Phonon Calculations

This table summarizes key numerical parameters that critically influence the quality of phonon spectra and the adherence to sum rules.

| Parameter | Description | Recommended Value / Action | Impact on Sum Rules |

|---|---|---|---|

ecutwfc / cut_off_energy |

Plane-wave energy cutoff | System-dependent; test for convergence. | Higher values reduce FFT grid-related ASR violation [5]. |

kpoints_mp_spacing |

k-point grid density | ~0.07 Ã…â»Â¹ or finer [9]. | Affects accuracy of IFCs, Born charges, and dielectric tensor [8]. |

conv_thr (SCF) |

Electronic energy convergence | 1.0d-10 or tighter. |

Poor convergence leads to inaccurate forces and IFCs [8]. |

tr2_ph |

Phonon self-consistency threshold | 1.0d-12 to 1.0d-15 [7]. |

Directly affects the accuracy of the computed dynamical matrix [5]. |

asr |

Acoustic Sum Rule imposition | Set to true or 'simple'. |

Actively enforces translational invariance, setting acoustic modes to zero [9] [7]. |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools

This table details essential software and computational "reagents" used in the field for calculating and analyzing phonon spectra.

| Item / Software | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum ESPRESSO | Suite for ab initio electronic structure and phonon calculations (DFPT) [5] [8]. | Uses pw.x for SCF and ph.x for DFPT. The dynmat.x tool is used for post-processing. |

| CASTEP | Ab initio materials simulation code using DFT. | Supports both DFPT and finite-displacement methods for phonons. Can enforce ASR via input keyword [9]. |

| ABINIT | Software suite for ab initio calculations. | Used for high-throughput DFPT phonon calculations, as in the Materials Project database [2]. |

| ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment) | Python library for atomistic simulations. | Contains Phonons class for calculating phonons via the finite-displacement method. Includes an acoustic() method to enforce ASR [10]. |

| Finite-Displacement Method | An alternative to DFPT for phonons. | Involves calculating forces from small atomic displacements to build the force constant matrix. Can suffer from supercell-size errors [10]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why does the text in my computational workflow diagram appear blurry or unreadable when I export it?

This is almost always caused by insufficient color contrast between the text color (fontcolor) and the background color (fillcolor) of the node or the graph itself [11] [12]. When colors are too similar, the text loses definition. This is especially common when diagrams created for light backgrounds are viewed on dark backgrounds, or vice-versa.

Q2: How can I quickly fix contrast issues in my Graphviz diagrams?

Explicitly set the fontcolor and fillcolor attributes for your nodes, edges, and graph to ensure high contrast. A good rule is to use light-colored text on dark backgrounds and dark-colored text on light backgrounds [12]. For example, use fontcolor="white" and fillcolor="#202124" for a dark node.

Q3: What are the official minimum contrast ratios for accessibility? For standard text, the minimum contrast ratio should be at least 4.5:1. For large-scale text (at least 18 point or 14 point bold), the minimum is 3:1 [13] [14]. The enhanced (Level AAA) requirement is 7:1 for normal text and 4.5:1 for large text [13].

Q4: Which output format is best for preserving text and diagram quality? For the best results, use vector-based formats like SVG or PDF [11] [12]. These formats are resolution-independent, meaning your diagrams and text will remain sharp and clear at any zoom level, unlike pixel-based formats like PNG which can become blurry when scaled.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Fuzzy Text in Diagrams

Problem: Text labels in your visualized computational pathway or phonon spectrum graph are fuzzy, indistinct, or difficult to read.

Solution: Manually define high-contrast colors using the approved palette.

- Identify Low-Contrast Elements: Check all nodes, edges, and the graph background for color combinations that are too similar.

- Apply Explicit Colors: In your DOT script, define the

fontcolor,fillcolor, andbgcolorattributes. Do not rely on default settings. - Use a Contrast Checker: Employ online color contrast tools to verify your color pairs meet the 4.5:1 ratio.

- Choose the Right Format: Generate your diagram in SVG format for on-screen viewing and analysis.

Example Correction: The following DOT code creates a clear, high-contrast diagram suitable for both light and dark mode presentations.

Diagram Title: Phonon Spectrum Analysis Workflow

Guide 2: Diagnosing Instabilities in Spectral Analysis

Problem: Your phonon spectrum calculations show unexpected negative frequencies, and you need to determine if they are physical phenomena or numerical errors.

Solution: Follow a systematic protocol to isolate the cause.

Experimental Protocol:

- Vary Computational Parameters:

- Change the energy cutoff and k-point grid density.

- A real physical instability will persist across different parameters, while a numerical artifact will diminish or disappear with higher precision [11].

- Inspect the Force Constants:

- Examine the dynamical matrix for unphysical values, such as unreasonably large or discontinuous force constants, which suggest numerical errors.

- Check for Convergence:

- Ensure all properties (energy, forces, stress) are fully converged with respect to the key parameters listed in the table below.

- Compare with Alternative Methods:

- Validate your results using a different computational code or method where possible.

The logic of this diagnostic process is summarized in the following workflow:

Diagram Title: Negative Frequency Diagnosis Logic

Quantitative Data for Computational Experiments

Table 1: Convergence Thresholds for Phonon Calculation Parameters

| Parameter | Recommended Starting Value | Convergence Threshold | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plane-Wave Energy Cutoff | 50 eV | Total energy change < 1 meV/atom | Determines basis set size and accuracy of wavefunction representation. |

| k-point Grid Density | 4x4x4 | Force change < 0.01 eV/Ã… | Samples the Brillouin zone to ensure accurate integration. |

| Supercell Size | 2x2x2 | Phonon frequency change < 0.1 THz | Used for finite-displacement method to capture force constants. |

| Force Convergence | 0.1 eV/Ã… | 0.01 eV/Ã… | Ensures atomic positions are relaxed to the ground state before phonon calculation. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Phonon Spectrum Research

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| DFT Code (e.g., VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO) | Performs first-principles calculations to obtain the electronic ground state and interatomic forces. |

| Phonopy Software | Post-processes force constants from DFT to calculate phonon dispersion spectra and density of states. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Provides the computational power required for large-scale DFT and phonon calculations. |

| Visualization Tool (e.g., VESTA, Matplotlib) | Generates plots and diagrams for analyzing phonon spectra, force constants, and crystal structures. |

| Epiisopodophyllotoxin | Epiisopodophyllotoxin |

| Einecs 282-346-4 | Einecs 282-346-4, CAS:84176-80-7, MF:C42H38Cl2N10O7S2, MW:929.9 g/mol |

Computational Strategies for Predicting and Analyzing Phonon Spectra

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Computational Solutions

Table 1: Key Computational Tools and Parameters for DFPT Phonon Calculations

| Item | Function / Purpose | Implementation Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DFPT Code | Solves perturbed Kohn-Sham equations to compute second-order force constants and response properties. | VASP (IBRION=7 or 8) [15], ABINIT [16] [17], Quantum ESPRESSO [18], RESCU [19] |

| Post-Processing Tool | Analyzes force constants to compute phonon band structure, density of states (DOS), and thermodynamic properties. | Phonopy [20], Anaddb (in ABINIT) [16] [21] |

| Exchange-Correlation Functional | Approximates electron-electron exchange and correlation effects in the DFT Hamiltonian. | PBEsol GGA recommended for accurate phonon frequencies [17] |

| Pseudopotential Library | Represents core electrons and ionic potential, defining chemical identity and accuracy. | PseudoDojo [17] |

| k-point & q-point Grids | Sample the Brillouin zone; convergence is critical to avoid unphysical negative frequencies [18] [17]. | Typical density: ~1500 points per reciprocal atom [17] |

| Einecs 300-951-4 | Einecs 300-951-4, CAS:93965-04-9, MF:C44H61N15O12S2, MW:1056.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Apatinib metabolite M1-1 | Apatinib Metabolite M1-1 | Apatinib metabolite M1-1 (E-3-hydroxy-apatinib) is a key active metabolite for studying drug-drug interactions and CYP450 enzyme inhibition. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common causes of negative frequencies in my phonon spectrum, and how can I fix them?

Negative (imaginary) frequencies in a phonon spectrum often indicate a structural instability or a numerical problem in the calculation. The most common causes and their solutions are outlined below.

Cause 1: Inadequate k-point or q-point sampling.

- Explanation: Using a q-point mesh that is too coarse can lead to poor convergence and unphysical negative frequencies, particularly for acoustic modes near the Γ-point [18] [17].

- Solution: Systematically increase the density of the q-point grid until the phonon frequencies converge. A recommended starting point is a grid density of approximately 1500 points per reciprocal atom [17].

Cause 2: Breaking of the Acoustic Sum Rule (ASR).

- Explanation: The ASR requires that the acoustic modes at the Γ-point have zero frequency. Numerical errors can break this rule, leading to small imaginary frequencies [17].

- Solution: Impose the ASR during post-processing. In ABINIT, this is done automatically by

anaddbwhen creating the phonon band structure [21]. A significant breaking of the ASR (e.g., acoustic modes > 30 cmâ»Â¹) can also signal insufficient plane-wave cutoff convergence [17].

Cause 3: Incorrect or broken crystal symmetry.

- Explanation: If the crystal structure used in the phonon calculation lacks the correct symmetry, it can lead to incorrect force constants and spurious instabilities [20].

- Solution: Before the DFPT run, carefully relax the atomic positions and lattice constants, then enforce the expected symmetry. Manually edit the

POSCAR/CONTCARfile to round off tiny deviations (e.g., -0.00001249 → 0.00000000) and perform a final relaxation with symmetry enforced (ISYM=2in VASP) and fixed lattice constants (ISIF=2) [20].

Cause 4: A genuine physical instability.

- Explanation: The calculation may be correct, revealing a true dynamical instability in the structure, suggesting a phase transition to a different crystal structure [17].

- Solution: Investigate the mode eigenvectors to understand the nature of the instability. The calculation might need to be performed on a different, lower-symmetry phase of the material.

Q2: My DFPT calculation is not converging. What can I do?

If the self-consistent cycle for a DFPT perturbation is not converging, try the following steps:

- Restart from wavefunctions: Use the

ird1wfandget1wftags (in ABINIT) to restart the calculation from the first-order wavefunction files, which can improve stability [21]. - Tighten SCF thresholds: Use tighter convergence criteria for the ground state calculation (e.g.,

EDIFF = 1.0E-8in VASP) to provide a high-quality starting point for the DFPT [20]. - Increase SCF steps: Increase the maximum number of steps (

NSTEPin ABINIT,NSWin VASP) for the DFPT cycle itself.

Q3: Should I use IBRION=7 or IBRION=8 in VASP for DFPT phonons?

The choice depends on your system and computational resources.

IBRION=8: Uses symmetry to reduce the number of required displacements. This is generally faster for small, high-symmetry systems. However, it does not supportNCORE/NPARparallelization and may incorrectly handle symmetries in systems with vacuum (e.g., monolayers) [20].IBRION=7: Displaces all atoms in all Cartesian directions. While this involves more displacements, it allows for efficientNCORE/NPARparallelization. This often makes it faster and more reliable for larger cells or low-symmetry systems, including monolayers [20].

Recommendation: For monolayers or when running on many cores, IBRION=7 is typically the better choice [20].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Negative Frequencies in Phonon Spectrum

This guide provides a systematic protocol for diagnosing and resolving the issue of unphysical negative frequencies.

Diagram 1: Diagnostic workflow for negative frequencies.

Experimental Protocol:

Initial Diagnosis:

- Check the Location: Are the negative frequencies only for acoustic modes very close to the Γ-point (|q| < 0.05)? If yes, this is likely a numerical issue with the ASR [17]. Are they present across the entire Brillouin Zone? This may indicate a physical instability.

- Inspect Output Logs: Look for warnings about the breaking of sum rules.

Remedial Actions:

- For ASR Violation:

- Procedure: In your post-processing step, ensure the ASR is applied. For example, in ABINIT, this is handled by

anaddb[21]. In Phonopy, symmetry tolerance can be adjusted. - Validation: After imposition, re-plot the phonon spectrum. The acoustic branches at Γ should be at zero frequency.

- Procedure: In your post-processing step, ensure the ASR is applied. For example, in ABINIT, this is handled by

- For q-grid Non-Convergence:

- Procedure: Perform a convergence test. Run phonon calculations with successively denser q-point grids (e.g., 4x4x4, 6x6x6, 8x8x8). Use consistent computational parameters.

- Validation: The phonon frequencies, particularly where negatives appeared, should stabilize. A grid producing ~1500 points per reciprocal atom is often sufficient [17].

- For Symmetry Issues:

- Procedure: As a pre-DFPT step, create a symmetrically perfect structure.

- Relax the structure with

ISIF=3andISYM=0to find the approximate equilibrium geometry [20]. - Manually edit the resulting

CONTCARfile, setting very small lattice vector components and atomic coordinates to zero [20]. - Perform a final relaxation with fixed lattice constants (

ISIF=2) and symmetry enforced (ISYM=2) [20]. Use this final structure for the DFPT calculation.

- Relax the structure with

- Validation: The output should confirm the correct space group symmetry before the DFPT run begins.

- Procedure: As a pre-DFPT step, create a symmetrically perfect structure.

- For ASR Violation:

Problem: DFPT Calculation is Too Slow or Fails on Large Supercells

For large systems, the computational cost of DFPT can become prohibitive with conventional solvers.

Solution: Leverage advanced solvers like the Chebyshev filtered subspace iteration (CFSI) method, as implemented in codes like RESCU. This method scales efficiently with system size and is optimized for large supercells [19].

Experimental Protocol & Validation:

- Reference Calculation: Perform a DFPT phonon DOS calculation on a conventional unit cell (e.g., 8 atoms for diamond) using a conventional solver and a very dense q-point grid for convergence. This establishes the reference DOS [19].

- Large-Scale Calculation: Perform a single Γ-point DFPT calculation on a large supercell (e.g., 216 atoms for diamond) using the PCFSI method [19].

- Validation: Compare the phonon DOS from the large supercell with the reference DOS. A sufficiently large supercell (e.g., 216 atoms) will recover the DOS of the q-converged small cell, validating the accuracy of the approach while demonstrating its computational efficiency [19].

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Computational Efficiency for Diamond Phonon DOS [19]

| Supercell Size | Computational Method | Key Outcome | Relative Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8 atoms | Conventional Solver (dense q-grid) | Reference, converged DOS | Baseline (slow) |

| 64 atoms | PCFSI Solver (Γ-point only) | DOS with minor discrepancies | Challenging on single node |

| 216 atoms | PCFSI Solver (Γ-point only) | DOS matches reference | Feasible, ~30 mins/displacement on 48 CPUs |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary causes of negative frequencies (imaginary modes) in my ML-predicted phonon spectra?

Negative frequencies in phonon spectra often stem from two main sources:

- Real Dynamical Instabilities: These indicate a genuine structural instability, meaning the calculated structure is not a true ground state and may be prone to transitioning to a different phase [2].

- Numerical Artifacts: These are errors introduced by the calculation process itself. Common causes include:

- Insufficient training data for the Machine Learning Interatomic Potential (MLIP), particularly for certain atomic environments or elements [22].

- Poor convergence with respect to parameters like the plane-wave cutoff or the k-point grid used in the underlying DFT calculations [2].

- Inadequate treatment of long-range interactions in polar materials, which requires correct incorporation of Born effective charges and dielectric tensors [2].

Q2: My MLIP phonon frequencies show significant deviation from DFT benchmarks. How can I improve accuracy?

Improving accuracy requires a focus on the quality and diversity of the training data:

- Enhance Training Dataset: Ensure your dataset is diverse and comprehensive. One effective method is to use a subset of supercell structures where all atoms are randomly perturbed (with displacements of 0.01 to 0.05 Ã…). This generates rich force information with fewer DFT calculations [22].

- Increase Data Quantity and Quality: The accuracy of an MLIP is directly linked to the amount and quality of its training data. Expanding the dataset to cover a wider range of structural motifs and elemental compositions can significantly close the gap with DFT results [22].

- Model Selection: Employ state-of-the-art MLIP architectures like MACE (Multi-Atomic Cluster Expansion), which have demonstrated high accuracy in predicting harmonic phonon properties across diverse materials [22].

Q3: What are the key metrics to validate the reliability of a phonon spectrum generated using an MLIP?

To ensure reliability, check the following quantitative and qualitative metrics against a held-out test set or known experimental data:

| Metric | Description | Target Value (Example) |

|---|---|---|

| Phonon Frequency MAE | Mean Absolute Error of vibrational frequencies across the full dispersion [22]. | e.g., ~0.18 THz [22] |

| Free Energy MAE | MAE of vibrational Helmholtz free energy at a specific temperature [22]. | e.g., ~2.19 meV/atom at 300K [22] |

| Dynamical Stability Accuracy | Classification accuracy for predicting material dynamical stability (presence/absence of imaginary modes) [22]. | e.g., >86% [22] |

| Sum Rule Breaking | Deviation from the acoustic sum rule (ASR) and charge neutrality sum rule (CNSR) after interpolation [2]. | As close to zero as possible; large deviations indicate poor convergence [2]. |

Q4: For high-throughput screening, how can I efficiently generate a training dataset for an MLIP?

Traditional phonon calculations are computationally expensive. An efficient, data-driven alternative is:

- Strategy: Instead of generating many supercells with a single displaced atom (the finite-difference method), create a smaller set of supercells where all atoms are randomly perturbed. This efficiently samples the potential energy surface.

- Data Efficiency: Studies suggest that using as few as six randomly perturbed structures per material can achieve a good balance between computational cost and prediction accuracy when used to train a universal MLIP [22].

- Universal Potentials: Train a single, universal MLIP (like MACE) on a diverse dataset spanning many materials and elements. The model learns common structural features, reducing the number of required calculations per new material [22].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Persistent Imaginary Modes at the Gamma Point (Γ)

Imaginary modes exclusively near the Γ point are often a numerical artifact, not a real instability [2].

Diagnosis and Resolution Workflow:

- Impose Sum Rules: Enforce the Acoustic Sum Rule (ASR) and Charge Neutrality Sum Rule (CNSR) during the force constant interpolation process. Most software packages have options to do this [2].

- Use Denser Grids: Ensure the k-point and q-point grids used in your DFT and DFPT calculations are sufficiently dense. A convergence test is recommended [2].

- Increase Cutoff Energy: A small breaking of the ASR can signal a lack of convergence with respect to the plane-wave cutoff energy. Increasing the cutoff can resolve this [2].

Issue: Low Accuracy in Predicted Thermodynamic Properties (e.g., Free Energy)

Inaccurate thermodynamic integrals from the phonon density of states (DOS) point to broader inaccuracies across the spectrum.

Resolution Steps:

- Audit Training Data: Verify that your MLIP's training set includes materials with similar bonding environments and contains the elements present in your system of interest [22].

- Benchmark Against DFT: Calculate vibrational free energies for a small set of materials using both fully converged DFT and your MLIP. The mean absolute error (MAE) should be on the order of a few meV/atom for the model to be reliable for thermodynamic studies [22].

- Refine the MLIP: If accuracy is insufficient, consider refining the potential by adding more targeted training data, especially for regions of the spectrum or material types where it performs poorly [22].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Phonon Workflow using Universal ML Potentials

This protocol outlines the steps for a high-throughput screening of phonon properties using a pre-trained universal MLIP [22].

Workflow Diagram:

Detailed Steps:

- Dataset Curation: Assemble a diverse set of crystal structures encompassing the chemical space of interest. For a universal potential, this should include many elements and structure types [22].

- Efficient DFT Data Generation: For each material, generate a small number of supercells (e.g., ~6) with all atoms randomly perturbed (displacements of 0.01-0.05 Ã…). Perform DFT calculations to obtain the energies and forces for these structures [22].

- MLIP Training: Train a state-of-the-art MLIP model like MACE on the collected dataset of structures and forces. The model learns the underlying potential energy surface [22].

- Phonon Property Prediction: Use the trained MLIP within a lattice dynamics code (e.g., using the finite-displacement method) to calculate the interatomic force constants, phonon dispersions, and DOS.

- Validation: Rigorously validate the model's predictions for phonon frequencies, free energy, and dynamical stability against a held-out test set of DFT calculations [22].

Protocol 2: Correcting for Imaginary Modes in Polar Materials

This protocol addresses the specific case of imaginary modes caused by incorrect handling of long-range dipole-dipole interactions [2].

Detailed Steps:

- Identify Polar Materials: Determine if your material is polar (non-centrosymmetric).

- Calculate Dielectric Properties: Use Density Functional Perturbation Theory (DFPT) to compute the Born effective charges (({Z}^*)) and the electronic part of the dielectric tensor (({\varepsilon}^\infty)) [2].

- Incorporate in Non-Analytical Correction: Apply the non-analytical term correction (NAC) to the dynamical matrix for wavevectors near the Gamma point ((q \rightarrow 0)). This accounts for the splitting between Longitudinal Optical (LO) and Transverse Optical (TO) modes and can eliminate spurious imaginary modes [2]. Most modern DFPT and phonon codes include an option to apply this correction if the dielectric tensors and Born charges are provided.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential computational tools and data for high-throughput phonon prediction.

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function |

|---|---|---|

| MACE (Multi-Atomic Cluster Expansion) [22] | Machine Learning Interatomic Potential | A state-of-the-art MLIP architecture for highly accurate learning of potential energy surfaces and force predictions for diverse materials. |

| DFT (Density Functional Theory) [2] | First-Principles Calculation | The foundational quantum mechanical method used to generate high-fidelity training data (energies and forces) for MLIPs. |

| DFPT (Density Functional Perturbation Theory) [2] | First-Principles Calculation | An efficient approach for directly calculating second-order derivatives (force constants, Born charges, dielectric tensors) for phonons. |

| ABINIT [2] | Software Package | A comprehensive suite for performing DFT and DFPT calculations; used to generate the dataset for 1,521 semiconductors in one major study [2]. |

| High-Throughput Phonon Database [2] | Computational Data | Curated datasets of pre-calculated phonon properties (e.g., for 1,521 semiconductors) used for training, validation, and benchmarking of new models [2]. |

| Random Supercell Perturbations [22] | Computational Methodology | A data-efficient strategy for generating training structures by applying small random displacements to all atoms in a supercell. |

| Einecs 278-843-0 | Einecs 278-843-0, CAS:78111-51-0, MF:C66H63Cl2N9O17P2, MW:1387.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| trans-Barthrin | trans-Barthrin | High-purity trans-Barthrin, a synthetic pyrethroid. For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for diagnostic, therapeutic, or personal use. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core method for predicting phonons using an equivariant neural network? The method involves using an E(3)-equivariant graph neural network to learn a potential energy model from atomic structures. Phonon modes are predicted by directly evaluating the second derivative Hessian matrices of this learned energy model. The model is first trained on energy and force data (zeroth and first-order derivatives), and the Hessian (the second-order derivative) is then used to derive the vibrational properties [23] [24].

Q2: Why might my phonon spectrum show unphysical negative frequencies? Negative frequencies in a phonon spectrum typically indicate one of two main issues [25]:

- Non-equilibrium Geometry: The atomic structure is not at a local energy minimum. The forces on the atoms are not zero, violating the harmonic approximation.

- Insufficient Numerical Accuracy: This can be caused by several factors:

- A step size that is too large in the finite-difference calculation of force constants.

- Inadequate numerical integration settings.

- Poor k-point sampling in the Brillouin zone.

- Errors in the density fit.

Q3: How does using Hessian data improve the energy model? Using the Hessian as a higher-order type of training data can improve the accuracy of the energy model beyond what is achievable with only energy and force data. This approach also creates a direct link to experimental observations, as vibrational properties can be measured via techniques like IR/Raman spectroscopy. This allows for the potential fine-tuning of energy models using experimental data, correcting for approximations in the simulated training data [23].

Q4: What are the advantages of this approach over traditional finite-difference methods? Traditional methods require building large supercells and enumerating many independent atomic displacement patterns, which is computationally expensive. The neural network approach directly calculates the Hessian, which naturally preserves the relevant crystalline symmetries and acoustic sum rules due to its equivariant architecture. This avoids the need for band structure unfolding and manual imposition of symmetry constraints [23].

Q5: Can this method analyze the symmetry properties of phonon modes? Yes. For molecules, the method can derive symmetry constraints for infrared (IR) and Raman active modes by analyzing the irreducible representations of the predicted phonon modes. This is crucial for connecting predictions with experimental spectroscopy results [23] [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Negative Frequencies in Phonon Spectrum

Problem: The calculated phonon spectrum contains negative (imaginary) frequencies, indicating a structural or numerical problem.

Diagnosis and Solutions: Table: Diagnosing Causes of Negative Frequencies

| Cause | Description | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Non-equilibrium Geometry | Atomic structure is not fully relaxed; residual forces remain. | Perform a more rigorous geometry optimization until the maximum force on all atoms is below a strict threshold (e.g., 1.0e-6 eV/Ã…). Ensure the structure is at a true local minimum [25]. |

| Large Numerical Step Size | Using a too-large displacement step in force constant calculations introduces errors. | Reduce the displacement step size used for numerical differentiation. For the neural network method, ensure the automatic differentiation for Hessian calculation is numerically stable [25]. |

| Poor Training Data | The underlying energy model is inaccurate due to insufficient or low-quality training data. | Retrain the equivariant network with more accurate or a larger volume of energy and force data. Consider including Hessian data in the training to better capture the local energy landscape [23]. |

| General Accuracy Issues | Numerical integration, k-space sampling, or fit errors propagate into the Hessian. | Improve the overall numerical accuracy of the calculation. Check convergence with respect to key parameters [25]. |

Issue 2: Energy Model Does Not Converge During Training

Problem: The training process of the equivariant graph neural network fails to converge to a low error on energy and force predictions.

Recommended Actions:

- Data Quality Check: Verify the quality and consistency of your training dataset (energies and forces).

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Adjust conservative training parameters, such as reducing the learning rate or changing the optimizer.

- Progressive Training: Start training the model on a smaller, simpler system or with a smaller basis set to achieve initial convergence, then use this pre-trained model as a starting point for the full system [25].

Issue 3: Phonon Predictions Violate Physical Symmetries

Problem: The predicted phonon spectrum does not respect the known crystallographic symmetries or acoustic sum rules (ASR).

Solution: This issue is largely mitigated by the use of an E(3)-equivariant architecture, which is designed to inherently preserve translational and rotational symmetries. If minor violations occur, they may be due to numerical precision. The use of an equivariant network avoids the need for manual imposition of symmetry constraints [23].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Workflow for Phonon Prediction from an Equivariant Neural Network

Diagram Title: Phonon Prediction Workflow

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Data Collection: Assemble a dataset of atomic structures with their corresponding DFT-calculated total energies and atomic forces.

- Model Training: Train an E(3)-equivariant graph neural network (e.g., based on architectures like NequIP or MACE) to predict the total energy of a structure. Forces are used as training labels, typically obtained via automatic differentiation of the energy with respect to atomic coordinates.

- Geometry Optimization: Use the trained energy model to relax the atomic structure to its equilibrium state, where forces on all atoms are negligible.

- Hessian Calculation: At the equilibrium geometry, calculate the full Hessian matrix (the second derivative of the energy with respect to atomic coordinates) using automatic differentiation through the trained network.

- Dynamical Matrix: Translate the real-space Hessian into a momentum-space dynamical matrix for a set of q-points in the Brillouin Zone.

- Phonon Calculation: Diagonalize the dynamical matrix at each q-point to obtain the phonon frequencies and eigenvectors. These results can be used to plot the phonon dispersion and density of states [23].

Protocol 2: Diagnosing Negative Frequencies

Diagram Title: Negative Frequency Diagnosis Path

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Components for Phonon Calculations with Equivariant Neural Networks

| Item | Function | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| E(3)-Equivariant GNN Architecture | Core model that respects Euclidean symmetries; maps atomic structure to potential energy. | NequIP, MACE, e3nn, Allegro. Essential for correct physical predictions [23]. |

| Energy & Force Training Dataset | Data used to train the neural network potential. | Typically from ab-initio (DFT) calculations. Higher quality data leads to more reliable phonons [23]. |

| Automatic Differentiation Engine | Software tool to compute Hessian matrix from the trained energy model. | Frameworks like JAX, PyTorch, or TensorFlow enable efficient computation of second-order derivatives [23]. |

| Geometry Optimization Algorithm | Finds the local energy minimum structure where phonon calculations are valid. | L-BFGS, FIRE. Critical to eliminate imaginary frequencies from residual forces [25]. |

| Symmetry Analysis Tool | Determines irreducible representations of phonon modes for IR/Raman activity. | Used for post-processing predictions to connect with experimental observables [23]. |

| Pirlindole lactate | Pirlindole Lactate | Pirlindole lactate is a selective, reversible MAO-A inhibitor (RIMA) for depression and fibromyalgia research. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

| 7-Angeloylplatynecine | 7-Angeloylplatynecine | 7-Angeloylplatynecine for Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic, therapeutic, or personal use. This high-purity compound supports analytical research and phytochemical studies. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What do "negative frequencies" in my phonon spectrum calculation actually mean? In computational phonon analysis, a "negative frequency" is a mathematical indication of a structural instability. It arises when the curvature of the potential energy surface is negative along the vibrational mode described by the corresponding eigenvector. Physically, this signifies that the atomic configuration is not at a true energy minimum (like being at a saddle point) and that displacing the atoms in this specific mode would lower the system's energy, potentially leading to a phase transition or a different structural arrangement. Computationally, these are often reported as imaginary frequencies (the square root of a negative eigenvalue), but are sometimes displayed as "negative" by convention [26].

Q2: Why are my phonon calculations for a large MOF supercell failing or producing many imaginary frequencies? This is a common challenge with complex frameworks and can stem from several interrelated issues [27] [2]:

- Insufficient Structural Relaxation: The initial geometry of the large supercell may not be fully relaxed. Even tiny residual forces on atoms can lead to significant imaginary frequencies. Ensure strict convergence criteria for geometry optimization (e.g., forces below 1 meV/Ã…) [2].

- Numerical Precision and Convergence: The calculation parameters, such as the plane-wave energy cutoff and k-point grid density for sampling the Brillouin zone, might be insufficient for the large system. A lack of convergence can manifest as small imaginary frequencies, particularly for acoustic modes near the gamma point (Γ) [2].

- Real Physical Instability: The imaginary frequencies might reflect a genuine soft mode in the material, indicating a dynamic instability at the calculated level of theory. This is a physically meaningful result, but it requires careful validation against known experimental data or higher-level calculations.

Q3: How can Machine Learning (ML) potentials help with large-scale MOF dynamics? Traditional ab initio phonon calculations with methods like Density Functional Perturbation Theory (DFPT) are computationally prohibitive for very large systems. ML potentials offer a solution by [28]:

- Surrogate Modeling: Training an ML model on high-quality, small-scale DFT calculations to learn the complex relationship between atomic coordinates and the potential energy surface.

- Scalability: Once trained, the ML potential can evaluate energies and forces for systems containing thousands of atoms at a fraction of the computational cost of a full DFT calculation, enabling phonon studies of large MOF supercells, interfaces, or composites.

Q4: What are the key steps to create a reliable ML potential for MOFs? Building a robust ML potential requires a meticulous workflow [28]:

- Dataset Generation: Perform hundreds to thousands of DFT single-point calculations on a variety of atomic configurations of the MOF, including small displacements from equilibrium, strained volumes, and high-temperature snapshots from molecular dynamics.

- Feature Selection (Descriptor Engineering): Choose appropriate descriptors that uniquely represent the atomic environments. Common choices include atom-centered symmetry functions, smooth overlap of atomic positions (SOAP), or moment tensors.

- Model Training: Train an ML model (e.g., Neural Network, Gaussian Approximation Potential) to map the atomic descriptors to the DFT-calculated energies and forces.

- Validation and Testing: Rigorously test the potential on a held-out dataset not used in training, ensuring it accurately reproduces DFT-level energies, forces, and, crucially, phonon frequencies.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Addressing Imaginary Frequencies in MOF Phonon Spectra

Imaginary frequencies are a major roadblock. The following workflow helps systematically diagnose and address the issue.

Table 1: Common Causes and Solutions for Imaginary Frequencies

| Cause Category | Specific Issue | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Numerical Precision | Insufficient k-point grid | Increase k-point density, use a Γ-centered grid [2]. |

| Low plane-wave cutoff | Systematically increase the kinetic energy cutoff until phonon frequencies converge [2]. | |

| Structural Issues | Incomplete geometry relaxation | Tighten force and stress convergence criteria (e.g., to 10â»â¶ Ha/Bohr) [2]. |

| Incorrect MOF phase or impurities | Validate the synthesized MOF phase with PXRD; polymorphism is common in MOFs like the Zr-terephthalate system [27]. | |

| Physical Reality | Genuine soft mode | Confirm with a different functional (e.g., hybrid HSE) or the GW method. Analyze the mode's eigenvector for structural insight [29]. |

Guide 2: Implementing an ML Potential Workflow for MOF Phonons

This guide outlines the protocol for using ML potentials to overcome system size limitations.

Key Experimental Protocol: High-Throughput Dataset Generation for ML Potentials

The quality of the training data is paramount. The following methodology, inspired by high-throughput screening approaches, is recommended [28] [2]:

System Preparation:

- Start with a fully optimized primitive or conventional cell of the MOF using a high-quality DFT setup (e.g., PBEsol functional, strict convergence criteria) [2].

- Construct a 2x2x2 or 3x3x3 supercell, ensuring it is large enough to capture relevant interactions.

Configuration Sampling:

- Finite Displacements: Randomly displace all atoms in the supercell by small amounts (e.g., 0.01-0.05 Ã…) from their equilibrium positions. Generate hundreds of such configurations.

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Snapshots: Run a short ab initio MD simulation at an elevated temperature (e.g., 300-500 K) and extract snapshots at regular intervals. This samples anharmonic regions of the potential energy surface.

- Strained Configurations: Apply small strains to the supercell lattice vectors to sample different volumes and shapes.

High-Throughput DFT Calculations:

Data Curation:

- Assemble the data into a structured database. Each entry should link the atomic configuration (element and position) to its corresponding energy and force vector.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for MOF and Phonon Research

| Item / Software | Primary Function | Relevance to MOF Phonons & ML |

|---|---|---|

| ABINIT | A comprehensive DFT suite. | Used for high-throughput DFPT phonon calculations; forms the foundation for generating training data in databases like the Materials Project [30] [2]. |

| CASTEP | A DFT code for materials modeling. | Enables phonon calculations using both DFPT and the finite-displacement method, the latter being crucial for metals and systems with ultrasoft pseudopotentials [31]. |

| Phonopy | A universal phonon analysis tool. | Post-processes force constants from DFT calculations to produce phonon dispersion curves, density of states, and thermodynamic properties. Directly outputs and handles "negative" frequencies [26]. |

| MLIP Packages (e.g., PANNA, QUIP) | Software for constructing ML interatomic potentials. | Provides the algorithms and frameworks to transform DFT datasets into functional ML potentials for large-scale molecular dynamics and lattice dynamics simulations [28]. |

| Materials Project (MP) | An open online database of computed materials properties. | Hosts a vast collection of pre-computed phonon band structures and densities of states for thousands of materials, serving as a valuable validation resource [30] [2]. |

| PseudoDojo | A curated table of pseudopotentials. | Provides high-quality, rigorously tested norm-conserving and ultrasoft pseudopotentials, which are critical for the accuracy and convergence of DFT/DFPT calculations [2]. |

| (-)-Salsoline hydrochloride | (-)-Salsoline hydrochloride, CAS:881-26-5, MF:C11H16ClNO2, MW:229.70 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (+)-Cathinone | (+)-Cathinone Hydrochloride | High-purity (+)-Cathinone for neuroscience research. A key psychoactive alkaloid from Khat. For research use only. Not for human consumption. |

Resolving Unphysical Negative Frequencies: A Practical Troubleshooting Guide

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Why do I get negative frequencies in my phonon spectrum calculation?

Negative frequencies (imaginary phonon modes) are a common issue and typically indicate that your system is not at a minimum energy configuration. The two most likely causes are:

- Insufficient Geometry Optimization: The atomic positions and cell parameters were not fully relaxed to the ground state. This requires converging forces and stresses to very tight tolerances (e.g., forces < 10â»â¶ Ha/Bohr) [32] [2].

- Inadequate Convergence of DFT Parameters: The phonon calculation is sensitive to the underlying electronic structure. Using an unconverged k-point grid for the self-consistent field (SCF) calculation or an insufficient plane-wave energy cutoff can lead to unphysical forces and negative frequencies [25] [33].

2. How are k-points and q-points related in phonon calculations?

They play distinct but interconnected roles:

- k-points sample the Brillouin zone for the electronic wavefunctions in the initial DFT calculation. A dense k-point grid is needed to accurately converge the total energy, electron density, and forces [34] [35].

- q-points sample the Brillouin zone for the phononic perturbations. In DFPT, the dynamical matrix is explicitly calculated on a coarse grid of q-points [36]. The quality of this coarse grid determines how well the interatomic force constants are represented. A well-converged k-point grid for the electronic problem is a prerequisite for accurate force constants and subsequent phonon frequencies on the q-point grid [37].

3. What is the difference between a coarse and a fine q-point grid?

In phonon calculations, you typically deal with two q-grids:

- Coarse q-grid: This is the grid on which the dynamical matrices are explicitly calculated (e.g., using DFPT or finite-differences). You must converge your phonon properties with respect to this grid [36].

- Fine q-grid: After obtaining the force constants, a much denser fine grid is used for Fourier interpolation to calculate a smooth phonon density of states (DOS) or band structure without the prohibitive cost of explicit calculations at every point [36].

4. My SCF calculation won't converge. What can I do?

SCF convergence problems can often be resolved by:

- Using more conservative mixing parameters (e.g., reducing

mixing_beta) [25]. - Switching to a different SCF algorithm, such as the MultiSecant or LIST methods [25].

- Employing a finite electronic temperature at the start of a geometry optimization and gradually reducing it as the optimization proceeds [25].

- Ensuring the k-point grid is not too sparse, as a single k-point can sometimes cause convergence issues [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Systematic k-point Convergence for Accurate Geometries

A robust geometry optimization requires a converged k-point grid.

- Objective: Determine the k-point density at which the lattice parameter (or other properties) changes within a desired tolerance.

- Protocol:

- Start with a coarse k-point grid (e.g., 3x3x3).

- Perform a full volume relaxation (

IBRION=2,ISIF=3in VASP) for each sequentially denser grid (4x4x4, 6x6x6, etc.) [34]. - For each calculation, extract the target property (e.g., lattice constant, total energy).

- Plot the property value against the k-point mesh density. The property is considered converged when its change with increasing k-point density falls below a predefined threshold (e.g., 0.001 eV/atom for energy) [35].

- Troubleshooting:

- For systems with anisotropic lattice vectors, use a grid of non-uniform density, with more points along directions with shorter reciprocal lattice vectors [36].

- If the property oscillates significantly, continue the convergence test until a clear plateau is observed.

Guide 2: Converging Phonon Frequencies and Resolving Negative Modes

This guide addresses the core thesis topic of diagnosing and fixing negative phonon frequencies.

- Objective: Obtain a phonon spectrum free of unphysical imaginary frequencies resulting from numerical inaccuracies.

- Pre-requisite Check: Ensure your initial structure is fully optimized with high accuracy.

- Force Convergence: Tighten the force convergence criterion during ionic relaxation (e.g., to

1.0e-8Ry/Bohr in Quantum ESPRESSO) [32]. The forces must be converged below the numerical noise level. - SCF Convergence: Use a tight SCF convergence threshold (e.g.,

conv_thr = 1.0d-10in Quantum ESPRESSO) to reduce noise in the forces [32].

- Force Convergence: Tighten the force convergence criterion during ionic relaxation (e.g., to

- Protocol for q-point Convergence:

- Converge the Coarse Grid: Perform DFPT calculations on a series of increasingly dense q-point grids (e.g., 2x2x2, 4x4x4, 6x6x6). A density of around 1500 points per reciprocal atom is often a good starting point [2].

- Fix Coarse Grid, Converge Fine Grid: Once the coarse grid is converged, use it to generate a phonon DOS on a fine interpolated grid. Increase the density of this fine grid until the DOS profile no longer changes [36].

- Validation Checks:

- Acoustic Sum Rule (ASR): At the gamma point (q=0), the acoustic modes should be zero. A significant deviation (e.g., >30 cmâ»Â¹) indicates poor convergence or the need to impose the ASR [2].

- Charge Neutrality Sum Rule (CNSR: The sum of the Born effective charges over all atoms in the cell should be close to zero for each direction. A large deviation can signal inadequate convergence [2].

Quantitative Data for Convergence

Table 1: Recommended Convergence Criteria for DFPT Calculations

| Parameter | Convergence Criterion | Purpose/Note |

|---|---|---|

| k-point Density | ~1500 points/reciprocal atom [2] | Found sufficient for phonons in high-throughput studies of semiconductors. |

| Energy Convergence | 0.001 eV/cell [35] | A common tolerance for total energy in high-throughput k-point convergence. |

| Force Convergence | < 10â»â¶ Ha/Bohr (~0.00027 eV/Ã…) [2] | Essential for geometry optimization prior to phonons to avoid imaginary frequencies. |

| Stress Convergence | < 10â»â´ Ha/Bohr³ [2] | For reliable cell parameter optimization. |

| SCF Convergence | 1.0d-10 Ry [32] | Tight threshold to ensure accurate forces for phonons. |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Negative Frequencies

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Large imaginary frequencies throughout the Brillouin Zone | Structure not in a local energy minimum [32]. | Re-run geometry optimization with tighter force convergence. |

| Small imaginary frequencies (< 0-50 cmâ»Â¹) near Γ-point | Inadequate k-point or q-point sampling [2]; Numerical noise. | Increase k-point grid for SCF; Increase q-point grid for DFPT; Impose Acoustic Sum Rule (ASR). |

| Isolated imaginary modes | Possible genuine crystal instability (soft mode). | Investigate the mode's eigenvector to determine if it corresponds to a known phase transition. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Computational Reagents

Table 3: Key Input Parameters and Their Functions

| Item | Function in Calculation |

|---|---|