Tailor-Made Sensors in Synthesis Robots: Revolutionizing Automated Chemical Research and Drug Discovery

This article explores the transformative integration of custom-designed sensors into automated synthesis platforms, a key innovation accelerating research in chemistry and pharmaceuticals.

Tailor-Made Sensors in Synthesis Robots: Revolutionizing Automated Chemical Research and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the transformative integration of custom-designed sensors into automated synthesis platforms, a key innovation accelerating research in chemistry and pharmaceuticals. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive guide from foundational principles to advanced applications. We cover the core motivations for moving beyond off-the-shelf components, detail methodologies for sensor implementation and data integration, and address critical challenges in optimization and troubleshooting. Furthermore, the article presents rigorous validation frameworks and comparative analyses against traditional methods, illustrating how these tailored systems enhance reproducibility, enable real-time reaction control, and pave the way for fully autonomous, self-optimizing laboratories.

Beyond Off-the-Shelf: The Foundational Need for Custom Sensors in Automated Synthesis

In modern research, particularly within the field of automated synthesis, the implementation of tailor-made sensors is revolutionizing high-throughput experimentation by enabling precise, automated, and online reaction monitoring. These custom-fabricated sensing solutions address a critical gap where standard analytical devices are too large, too expensive, or simply not designed for integration into automated platforms like synthesis robots. This application note details the journey from constructing low-cost, in-house photometers to developing sophisticated, professionally integrated sensor suites, providing researchers with the protocols and frameworks necessary to enhance their automated synthesis workflows.

Defining the Tailor-Made Sensor Spectrum

Tailor-made sensors encompass a broad range of devices, from academic, self-built prototypes to industry-developed custom modules. Their defining characteristic is their design, which is specifically adapted to fit unique experimental constraints and requirements that off-the-shelf products cannot meet.

Table 1: Comparison of Tailor-Made Sensor Approaches

| Feature | Low-Cost, Self-Produced Sensors | Commercially Customized Sensor Suites |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Low-budget, rapid prototyping and integration for specific experimental needs [1] | Optimized, robust, and scalable performance for commercial or demanding applications [2] [3] |

| Development Time | Short to medium (e.g., days to weeks for assembly and programming) [1] | Medium to long (e.g., months, involving specification, prototyping, and production phases) [2] [3] |

| Cost | Low (utilizing cost-effective components like single-board computers) [1] [4] | High (covering R&D, specialized manufacturing, and quality control) [2] [5] |

| Example Components | Raspberry Pi, custom adapter board, LED, photodetector [1] | Custom opto-semiconductor devices, proprietary optical couplers, specialized flow cells [2] [5] |

| Key Advantage | High flexibility and adaptability for academic research and proof-of-concept studies [1] | High reliability, performance validation, and long-term support for industrial processes [3] [5] |

The quantitative data from key studies demonstrates the performance and characteristics of materials used in tailor-made sensors.

Table 2: Key Polymer Materials for Photonic Sensor Platforms [4]

| Polymer Material | Typical Refractive Index | Transparency Range | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| PMMA (Polymethyl methacrylate) | 1.48–1.50 | Visible to near-infrared | Excellent optical clarity, low cost, ease of processing (e.g., NIL) |

| SU-8 | ~1.57 | UV to near-infrared | High-aspect-ratio structures, excellent mechanical stability after cross-linking |

| Polyimides | 1.65–1.70 | Visible to near-infrared | Outstanding thermal stability and chemical resistance |

| COC (Cyclic Olefin Copolymer) | ~1.53 | Visible to near-infrared | Low moisture absorption, low birefringence, biocompatible |

| PDMS (Polydimethylsiloxane) | ~1.41 | Visible to near-infrared | Highly flexible, elastomeric, biocompatible, conformal contact |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Integration of a Low-Cost Photometer for Online RAFT Polymerization Monitoring

This protocol describes the setup used to monitor the UV-induced cleavage of a RAFT end-group, demonstrating the integration of a self-produced photometer into a synthesis robot [1] [6].

1. Photometer Assembly and Integration:

- Hardware: Construct the photometer around a Raspberry Pi single-board computer running LabPi software. The core optical components are a blue LED (468 nm) light source and a TSL2561T light sensor from AMS [1].

- Cuvette: Use a semi-micro quartz glass cuvette (max volume 1.4 mL) for measurements [1].

- Robot Integration: Implement the photometer and a modified UV chamber into a Chemspeed SWING XL automated parallel synthesizer. The robot's overhead arm, equipped with a 4-needle head (4-NH), is used for automated liquid handling and sampling [1] [6].

2. Polymer Synthesis (Precursor to Monitoring):

- Reagents: Prepare solutions of the initiator (AIBN), chain-transfer agent (CPDB), and monomer (e.g., PEGMEMA or MMA) in dried DMF [1].

- Reaction Conditions: Use a [M]:[CTA]:[I] ratio of 50:1:0.25 for PEGMEMA and 200:1:0.25 for MMA. Degas the reaction mixture with nitrogen for 30 minutes and conduct solution polymerizations at 70 °C for 17 hours [1].

- Purification: Purify the resulting polymers (e.g., PMMA, poly(PEGMEMA)) via dialysis in THF and dry in vacuo [1].

3. Automated Sampling and Online Monitoring:

- Process: The synthesis robot automatically withdraws samples from the reaction vessel and transfers them to the modified UV chamber for irradiation [1].

- Measurement: After UV exposure, the robot transfers the sample to the quartz cuvette in the self-built photometer.

- Data Collection: The LabPi software records the absorbance data, enabling the construction of reaction kinetic profiles. The system revealed a 20-minute initiation time for poly(PEGMEMA) degradation, whereas PMMA was converted immediately [1] [6].

4. Validation with SEC:

- Validate the photometric results by characterizing all samples using Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) with UV and RI detectors to confirm the molar mass shift during the reaction [1].

Protocol: A Phased Approach for Commercial Custom Sensor Development

For applications requiring high reliability and volume production, a structured development process with a specialized manufacturer is recommended [3] [7].

Phase 1: Design and Specification

- Initial Engagement: Hold an engineer-to-engineer discussion to detail sensor requirements, including the physical environment, measurement range, accuracy, connectivity, and lifecycle needs [3] [7].

- Feasibility Analysis: The manufacturer performs a virtual analysis using Finite-Element Analysis (FEA) and CAD models to determine if an existing part can be turned into an active sensor or if a new sensor must be designed [3].

- Proposal: The manufacturer provides a solution outline, including a development plan, risk analysis, test protocols, and cost estimates for prototypes and series production [3].

Phase 2: Prototyping and Testing

- Rapid Prototyping: The manufacturer builds functional test samples within weeks using techniques like 3D printing and rapid prototyping [3].

- Validation Testing: Jointly defined test protocols are executed. This includes design validation (DV) under specific environmental conditions, loads, and other operational stresses. The sensor's performance is rigorously evaluated against the initial specifications [3] [7].

Phase 3: Production and Supply

- Lean Manufacturing: Upon prototype approval, transition to series production in ISO-accredited facilities utilizing lean manufacturing and automation for quality and scalability [3].

- Quality Assurance: Implement detailed control plans and capability studies. The manufacturer often supports the Production Part Approval Process (PPAP) [3].

- Supply Chain Management: The manufacturer manages inventory, forecasting, and logistics to ensure timely delivery of sensors, often supported by global production facilities [3].

Workflow and System Integration Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for a Tailor-Made Photometric Sensing Platform

| Item | Function / Role | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Board Computer | Serves as the core controller and data processor for the custom sensor. | Raspberry Pi 3 model B+ [1] |

| Adapter Board & Sensor Modules | Provides interface and connectivity for various sensor types (temperature, pH, photometer). | LabPi adapter board and modules [1] |

| Light Source & Detector | The core optical components for photometric measurements. | 468 nm LED (Everlight) and TSL2561T sensor (AMS) [1] |

| Measurement Cuvette | Holds the sample for consistent optical analysis. | Semi-micro quartz glass cuvette (1.4 mL max volume) [1] |

| Software Platform | Operates the sensor, collects data, and provides a user interface. | LabPi software (v0.23) [1] |

| Automated Synthesizer | The platform for performing and automating chemical reactions and sampling. | Chemspeed SWING XL with 4-needle head (4-NH) [1] [6] |

| Validation Instrumentation | Independent, high-fidelity technique to validate the results from the tailor-made sensor. | Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) with UV/RI detectors [1] |

| N-Nonylbenzene-2,3,4,5,6-D5 | N-Nonylbenzene-2,3,4,5,6-D5, MF:C15H24, MW:209.38 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| N2-Phenoxyacetylguanosine | N2-Phenoxyacetylguanosine, CAS:119824-66-7, MF:C18H19N5O7, MW:417.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The integration of robotic systems into research and industrial laboratories has revolutionized workflows, enabling unprecedented throughput and reproducibility. However, standard robotic platforms often function as isolated automation islands, limited by a lack of integrated, real-time analytical capabilities. This gap constrains their ability to make intelligent, adaptive decisions during experimental processes. The implementation of tailor-made sensors directly into synthesis robots represents a paradigm shift, transforming them from automated executors into intelligent, closed-loop systems capable of self-optimization and in-line monitoring [8] [1]. This application note details how custom sensor solutions are addressing the core limitations of standard robotic systems, with a specific focus on applications in chemical synthesis and materials research, providing researchers with detailed protocols and implementation frameworks.

Key Limitations and Sensor-Driven Solutions

Standard robotic systems face several intrinsic limitations that can be systematically addressed through the strategic implementation of custom sensors. The table below summarizes the primary constraints and their corresponding sensor-based solutions.

Table 1: Key Limitations of Standard Robotic Systems and Corresponding Sensor-Driven Solutions

| Key Limitation | Impact on Research | Tailor-Made Sensor Solution | Resulting Enhancement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of Real-Time Process Monitoring | Inability to track reaction progress or material changes in-situ; requires manual, offline sampling. | Integration of low-cost, miniaturized photometers [1], conductivity, pH, and gas sensors into the robotic workspace. | Enables online characterization and automated reaction monitoring, providing immediate kinetic data [1]. |

| Operation in Unstructured Environments | Difficulty adapting to unpredictable conditions or object variations, limiting application scope. | Deployment of advanced perception systems (AI-enabled vision, LiDAR, tactile sensors) for object recognition and navigation [9] [10]. | Improves dexterity and allows robots to handle complex objects and navigate dynamic environments [10]. |

| Inflexible, Pre-Programmed Control | Robots cannot adapt to unexpected outcomes or optimize processes in real-time. | Combination of in-situ sensor data with adaptive control algorithms (e.g., Reinforcement Learning, Model Predictive Control) [10]. | Facilitates adaptive control and learning, allowing the system to respond to sensor feedback and self-optimize [10]. |

| Limited Human-Robot Collaboration | Safety concerns and lack of intuitive interaction hinder effective human-robot teamwork. | Use of force/torque sensors, proximity detectors, and vision systems for safe interaction and intention recognition [9] [10]. | Creates a safe and effective collaborative workspace where robots can respond to human gestures and actions [10]. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementation of a Tailor-Made Photometer for Online Reaction Monitoring

This protocol details the methodology for integrating a custom-built photometer into a synthesis robot to monitor a photo-induced polymer end-group degradation reaction, based on the work of Liebscher et al. [1].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Automated Synthesizer | Platform for performing automated, parallelized, and miniaturized reactions. | Chemspeed SWING XL or equivalent, with an overhead robotic arm and liquid handling tools [1]. |

| Single-Board Computer | The core controller for data acquisition from the tailor-made sensors. | Raspberry Pi running specialized software (e.g., LabPi) [1]. |

| Tailor-Made Photometer | In-situ sensor for monitoring optical density/reactance during reactions. | A self-produced device with a 468 nm LED light source and a TSL2561T light sensor, housed in a 3D-printed enclosure [1]. |

| UV Chamber | Provides controlled UV irradiation for photo-induced reactions. | UVACUBE 100 or similar, modified for automated sampling [1]. |

| RAFT Polymers | Model compounds for demonstrating end-group degradation. | e.g., Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) or Poly(ethylene glycol) ether methyl methacrylate (poly(PEGMEMA)) synthesized via RAFT polymerization [1]. |

| Semimicro Cuvette | Sample holder for photometric measurement. | Quartz glass cuvette with a max volume of 1.4 mL [1]. |

Step-by-Step Workflow

Step 1: Sensor System Assembly and Integration

- Construct the photometer by mounting the LED and sensor on a custom adapter board facing a cuvette holder.

- House the assembly in a 3D-printed enclosure (using PETG or PLA filament) to ensure stability and exclude ambient light.

- Connect the photometer to the single-board computer (Raspberry Pi) and install the control software (e.g., LabPi).

- Physically integrate the photometer assembly and the modified UV chamber into the workspace of the synthesis robot, ensuring the robotic arm can access all key components [1].

Step 2: System Calibration and Workflow Programming

- Calibrate the photometer using standard solutions to establish a baseline and linear response range.

- On the synthesis robot's software, program the automated workflow. This includes:

PICK_UP_4NH: The robot arm picks up the 4-needle head (4-NH) tool.ASPIRATE_SAMPLE: Aspirate a defined volume of the reaction mixture from the vial.DISPENSE_TO_CUVETTE: Dispense the sample into the quartz cuvette in the photometer.MEASURE_ABSORBANCE: Trigger the LabPi system to record the absorbance.RETURN_SAMPLE: Transfer the sample back to the reaction vial.MOVE_TO_UV: Move the reaction vial to the UV chamber for a defined irradiation period.LOOP: Repeat the sampling and measurement cycle at programmed time intervals [1].

Step 3: Automated Reaction Execution and Monitoring

- Place the reaction vessel (e.g., containing the RAFT polymer solution) into a designated position on the synthesizer deck.

- Start the automated protocol. The robot will execute the sequence without user intervention.

- The system will periodically measure the absorbance, which decreases as the colored dithioester end-group degrades under UV light, building a kinetic profile of the reaction [1].

Step 4: Data Analysis and Validation

- Upon completion, export the time-stamped absorbance data from the LabPi software for analysis.

- Validate the photometric results against a standard characterization technique, such as Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) with UV and RI detectors, to confirm the correlation between absorbance loss and molar mass changes [1].

Visualization of the Automated Workflow

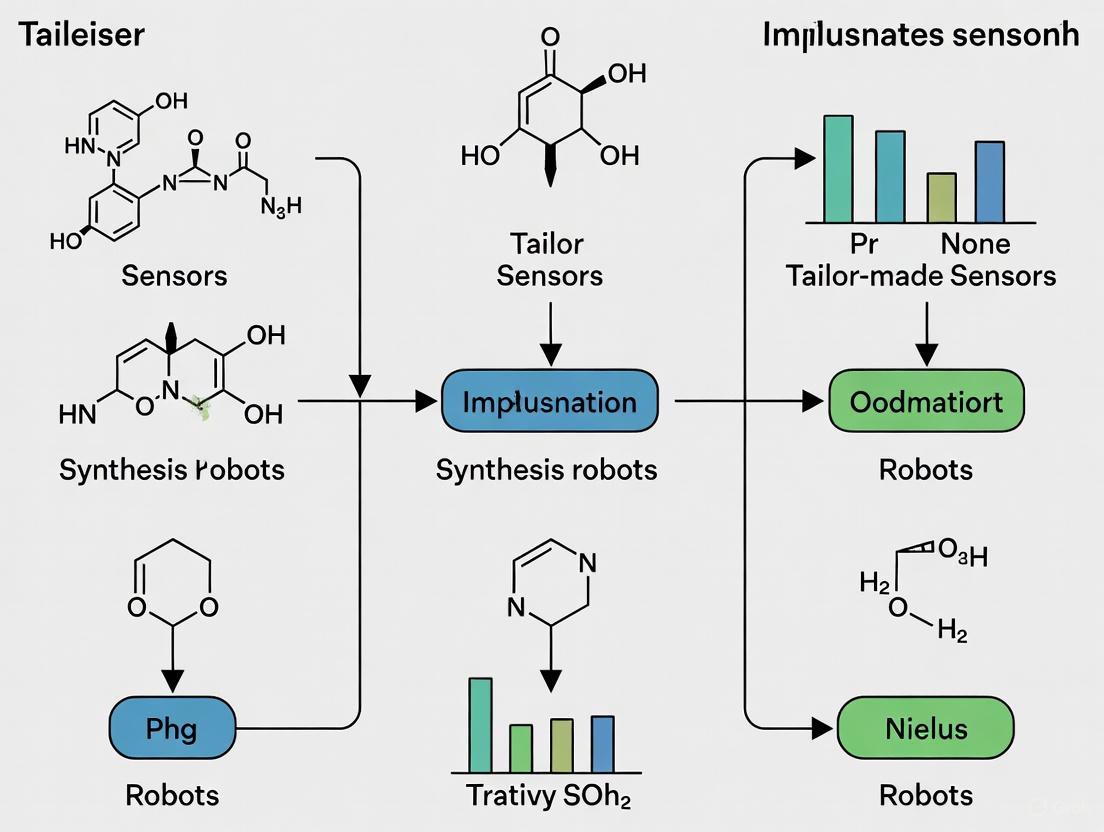

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and core components of the automated monitoring system.

Diagram 1: Automated reaction monitoring workflow. The robotic arm shuttles the sample between the UV chamber for reaction and the photometer for analysis, with a control computer managing the cycle and data acquisition until reaction completion.

The Broader Context: Material Intelligence and Advanced Sensing

The integration of sensors is a foundational step towards the concept of "material intelligence," where AI and robotics converge to create autonomous systems for materials discovery [8]. This extends beyond chemical synthesis. In life sciences, wearable polymer sensors for biochemical and physical sensing are enabling real-time health monitoring and personalized medicine, generating vast datasets for drug development [11] [12]. The common thread is the use of sensory data to close the control loop, whether for a single synthesis robot or a complex health monitoring system.

The following diagram conceptualizes this closed-loop, intelligent system.

Diagram 2: The sensory feedback control loop. Sensors monitor the process, data is processed (often with AI at the edge), an intelligent engine makes decisions, and the robotic actuator carries out commands, creating an adaptive system.

Application Notes and Future Perspectives

The implementation of tailor-made sensors is a key driver in overcoming the fundamental limitations of standard robotic systems. This approach transforms static automation into dynamic, intelligent experimentation. For researchers, this means:

- Accelerated Discovery: Real-time feedback drastically reduces optimization cycles [1].

- Enhanced Data Quality: In-line monitoring provides richer, higher-frequency kinetic data compared to discrete offline sampling [1].

- System Robustness: The ability to adapt to uncertainties makes robotic platforms viable for more complex, real-world applications [10].

Future advancements will be propelled by the further integration of AI-enabled smart sensors that perform edge computing, allowing for even faster, localized decision-making [9]. The focus will also expand to include the sustainability of sensor systems, encouraging the use of biodegradable polymers and designs for recyclability [11]. For drug development professionals, these evolving capabilities promise not only faster compound synthesis but also the integration of rich, real-time biological and physiological data from advanced wearable sensors, paving the way for more predictive models and personalized therapeutic solutions [13] [12].

The integration of tailor-made sensors into robotic synthesis platforms represents a paradigm shift in chemical research, enabling autonomous, data-rich, and self-optimizing experimentation. These systems move beyond simple task automation to provide real-time feedback control, allowing for dynamic process execution and self-correction in response to changing reaction conditions [14]. The core sensor modalities—color, temperature, pH, conductivity, and vision systems—form the perceptual foundation of these advanced platforms. By mimicking and extending human sensory capabilities, they generate continuous data streams that capture critical process parameters, thereby ensuring safety, improving reliability, and accelerating discovery and optimization cycles in fields such as drug development [14] [15].

The implementation of these sensors is a key enabler for the concept of chemputation—a universal abstraction of chemical synthesis where procedures are encoded in a dynamic programming language, allowing hardware-agnostic execution of complex chemical workflows [14]. This approach, coupled with robust sensor data, is critical for closing the loop in autonomous experimentation, where the outcomes of one experiment inform the parameters of the next without human intervention.

Core Sensor Modalities: Functions and Applications

The following table summarizes the key sensor modalities, their primary functions, and specific applications in automated synthesis environments.

Table 1: Core Sensor Modalities in Automated Synthesis Robots

| Sensor Modality | Primary Measurand | Key Function in Synthesis | Exemplary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Color Sensor | RGB values, Absorbance | Tracks reaction progression via color changes; monitors concentration. | End-point detection in a nitrile synthesis indicated by discoloration [14]. |

| Temperature Sensor | Reaction/Environment Temperature | Monitors exothermic/endothermic events; ensures safe thermal management. | Preventing thermal runaway during slow addition of an oxidant [14]. |

| pH Sensor | Hydrogen Ion Concentration | Monitors and controls acidity/basicity, critical for reaction rate and pathway. | Process state monitoring and fingerprinting for validation [14]. |

| Conductivity Sensor | Ionic Strength of Solution | Tracks the formation or consumption of ionic species. | Fingerprinting process stages and monitoring reagent addition [14]. |

| Vision System | Visual Phenomena (Turbidity, Precipitate) | Provides flexible, image-based condition monitoring and failure detection. | Detecting critical liquid handling failures (e.g., syringe breakage) [14]. |

Quantitative Sensor Performance and Specifications

The selection and integration of sensors require a careful balance of performance, size, and cost. The following table provides quantitative data and specifications for a typical implementation of low-cost sensors in a synthesis robot, as demonstrated in recent research.

Table 2: Performance Specifications and Implementation Details of Integrated Sensors

| Sensor Type | Measured Parameter/Performance | Implementation Context & Cost |

|---|---|---|

| Photometer (Color) | Wavelength: 468 nm (Blue LED) [15]. | Integrated into a synthesis robot (Chemspeed SWING XL) for online characterization; self-produced, low-cost [15]. |

| Temperature | Monitored internal reaction temperature to prevent exceeding a set maximum (e.g., during exothermic oxidation) [14]. | Part of a low-cost sensor suite connected to a custom SensorHub (Arduino module) on the Chemputer platform [14]. |

| Liquid Sensor | Binary output (0/1) for transfer consistency; used in challenging steps like filtration [14]. | Part of a low-cost sensor suite for process fingerprinting [14]. |

| Vision System | Multi-scale template matching and structural similarity for anomaly detection [14]. | Used for vision-based condition monitoring to detect hardware failures [14]. |

| Environmental Sensor | Ambient Temperature, Pressure, Humidity [14]. | Used to identify potential reproducibility issues across experiments [14]. |

Experimental Protocols for Sensor-Enabled Synthesis

Protocol: Closed-Loop Optimization of a Reaction Using In-Line Spectroscopy

This protocol details the setup and execution for the autonomous optimization of a chemical reaction, such as the Van Leusen oxazole synthesis or a manganese-catalysed epoxidation, using in-line analytical instruments for feedback [14].

I. Primary Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core closed-loop optimization cycle.

II. Step-by-Step Procedure

Initial Setup:

- Software Configuration: Load the dynamic χDL (XDL) procedure translated from a literature protocol into the ChemputationOptimizer software [14].

- Hardware Configuration: Provide the corresponding hardware graph that defines the robotic platform's components and connections.

- Algorithm Selection: In the configuration file, select a suitable optimization algorithm (e.g., from the Summit or Olympus frameworks) [14].

- Parameter Definition: Specify the reaction parameters to be optimized (e.g., temperature, stoichiometry, concentration) and the target objective (e.g., yield, purity).

Iterative Optimization Cycle:

- Step 1 - Procedure Execution: The robotic platform autonomously executes the synthesis procedure (e.g., reagent addition, stirring, temperature control) as defined by the XDL code [14].

- Step 2 - Automated Sampling & Analysis: The system uses integrated liquid handling to sample the reaction mixture. The sample is automatically transferred to an in-line analytical instrument (e.g., HPLC, Raman, or NMR spectrometer) [14].

- Step 3 - Data Processing: The raw spectral data is processed (e.g., peak picking, baseline correction) to quantify the reaction outcome (e.g., product yield) [14].

- Step 4 - Decision Making: The optimization algorithm analyzes the result and suggests a new set of input conditions predicted to improve the outcome.

- Step 5 - Procedure Update: The original XDL procedure is dynamically updated with the new set of parameters.

- Step 6 - Loop Termination: The cycle (Steps 1-5) repeats until a predetermined target is achieved or a maximum number of iterations (e.g., 25-50) is completed [14].

Data Management:

- All experimental procedures, parameters, raw spectral data, and processed results are automatically saved in a database for verification and future reference [14].

Protocol: Self-Correcting Synthesis with Low-Cost Sensors

This protocol describes the use of low-cost sensors (temperature, color) for real-time process control and safety monitoring, using examples like temperature-controlled oxidation and color-monitored nitrile formation [14].

I. Primary Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the dynamic control process for a temperature-monitored exothermic reaction.

II. Step-by-Step Procedure for Temperature-Controlled Oxidation

- Sensor Integration: Connect a temperature probe to the custom SensorHub (e.g., an Arduino module integrated into the Chemputer IP network) [14].

- Reaction Setup: Charge the reaction vessel with the substrate and place it in the reactor with temperature control.

- Dynamic Procedure Definition: Program the synthesis sequence using dynamic XDL steps, which include conditional logic for the

AbstractDynamicStepbase class. This defines the control flow based on real-time sensor data [14]. - Execution with Feedback Control:

- Initiate the slow addition of the oxidant (e.g., hydrogen peroxide).

- The temperature sensor continuously monitors the internal reaction temperature.

- The dynamic XDL step evaluates the temperature reading. If the temperature approaches a pre-defined safety threshold (e.g., 5°C below the maximum allowed), the step returns a command to pause the reagent addition.

- Once the temperature stabilizes and decreases, the dynamic step returns a command to resume addition.

- This loop continues until the entire volume of oxidant is added safely, preventing thermal runaway on a 25-gram scale [14].

III. Procedure for Color-Monitored End-Point Detection

- Sensor Integration: Install a color (RGBC) sensor to monitor the reaction mixture.

- Reaction Setup: Charge the vessel with the starting materials (e.g., aldehyde, ammonia, iodine).

- Dynamic Procedure Definition: Program the reaction step as a dynamic monitoring step, where the continuation condition is based on the color sensor reading.

- Execution with Feedback Control:

- Start the reaction (e.g., by heating or stirring).

- The color sensor tracks the discoloration of the reaction mixture, which indicates consumption of a key reagent like iodine [14].

- The dynamic step continuously assesses the color data. The reaction proceeds until the sensor detects a target color value, indicating completion.

- The system then dynamically proceeds to the next step in the synthesis (e.g., workup). This eliminates the need for predetermined, fixed reaction times [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key hardware, software, and reagents essential for implementing the sensor modalities and protocols described in this document.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item Name | Type | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Chemputer Platform | Robotic Hardware | A chemical processing unit that executes synthesis procedures based on the chemputation abstraction, allowing for hardware-agnostic automation [14]. |

| SensorHub | Hardware Interface | A custom-designed board (e.g., based on Arduino) that consolidates various low-cost sensors and connects them to the network for centralized data acquisition [14]. |

| LabPi / Self-Produced Photometer | Analytical Sensor | A low-cost, small-footprint photometer system for in-line UV-Vis characterization, enabling automated reaction monitoring inside a synthesis robot [15]. |

| Dynamic χDL (XDL) | Programming Language | An extension of the χDL language that allows for dynamic, conditional execution of synthesis steps based on real-time sensor input, enabling self-correction [14]. |

| AnalyticalLabware Python Package | Software Library | A standalone package for controlling various analytical instruments (HPLC, Raman, NMR) and processing spectral data, integrated into the Chemputer workflow [14]. |

| Hydrogen Peroxide | Chemical Reagent | An oxidant used in demonstrations of temperature-sensor-controlled reactions to prevent thermal runaway during exothermic additions [14]. |

| Iodine | Chemical Reagent | A reagent used in color-sensor-monitored reactions (e.g., nitrile formation), where its consumption is indicated by a visible discoloration [14]. |

| C12 NBD Galactosylceramide | C12 NBD Galactosylceramide, CAS:474942-98-8, MF:C42H71N5O11, MW:822 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Tetraethylammonium perchlorate | Tetraethylammonium perchlorate, CAS:2567-83-1, MF:C8H20ClNO4, MW:229.70 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The integration of tailor-made sensors into automated synthesis robots represents a paradigm shift in experimental science, enabling a closed-loop workflow where real-time data acquisition directly informs process control. This transition from automated to truly autonomous experimentation hinges on the ability to make decisions based on live analytical data, a process that fundamentally differs from simple automation where human researchers remain the decision-makers [16]. The implementation of custom sensors addresses critical bottlenecks in high-throughput experimentation by enabling automated online reaction monitoring, thereby providing the immediate feedback necessary for adaptive behaviors in dynamic processes [1]. This document outlines the application notes and protocols for implementing such systems, with a specific focus on the hardware and software architecture required for real-time data acquisition and feedback control within the context of synthesis robotics.

Technical Background and Workflow Architecture

The core of this workflow revolution lies in a hierarchical processing pipeline that transforms raw sensor data into adaptive behaviors. This pipeline typically involves three critical stages: data acquisition from integrated sensors, filtering and integration of multimodal data streams, and algorithmic decision-making that maps processed data to control actions [17]. For instance, in wire arc additive manufacturing (WAAM) processes, this pipeline enables the detection of defects like porosity and cracking through real-time analysis of optical, acoustic, and thermal signatures [18].

The integration of multiple sensing modalities is particularly crucial for capturing the complexity inherent in many chemical and material synthesis processes. Unlike single-sensor approaches that may miss critical process nuances, multimodal data fusion significantly enhances defect detection and process understanding [18] [19]. In exploratory chemical synthesis, for example, combining orthogonal analytical techniques such as UPLC-MS and NMR spectroscopy provides a characterization standard comparable to manual experimentation, allowing autonomous systems to navigate complex reaction spaces with confidence [16].

Table 1: Core Stages in Real-Time Data Processing for Adaptive Synthesis

| Processing Stage | Key Function | Representative Technologies |

|---|---|---|

| Data Acquisition | Continuous gathering of environmental and process parameters | Cameras, lidar, accelerometers, tactile sensors, custom photometers [17] [1] |

| Filtering/Integration | Smoothing inconsistencies and combining multiple data sources | Kalman filters, sensor fusion algorithms, multimodal data fusion [17] [18] |

| Decision-Making | Mapping cleaned data to control actions | PID controllers, reinforcement learning models, heuristic decision-makers [17] [16] |

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of this integrated workflow, from sensor data acquisition to process feedback.

Application Note: Implementing a Tailor-Made Photometer in a Synthesis Robot

Experimental Objective and Setup

This application note details a documented case study for implementing a small, low-cost, self-produced photometer into a Chemspeed SWING XL automated parallel synthesizer [1]. The primary objective was to enable automated online characterization of photoinduced RAFT end-group degradation, a post-polymerization modification process. The system's key achievement was establishing a closed-loop workflow where reaction progress could be monitored in real-time without manual intervention, dramatically increasing experimental throughput and consistency.

The hardware core was the LabPi digital measuring system, comprising a single-board computer (Raspberry Pi), a custom adapter board, and modular sensor components [1]. This system was selected for its small footprint, critical for the limited space inside synthesis robots, and its cost-effectiveness compared to commercial alternatives. The photometer module specifically used a blue LED (468 nm) and a light sensor (AMS TSL2561T) with measurements performed in a semi-micro quartz glass cuvette. A modified UV chamber (UVACUBE 100) was integrated to facilitate the photochemical reactions and automated sampling.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function/Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| LabPi System | Low-cost, modular data acquisition system based on Raspberry Pi [1] | Enables custom sensor integration and data processing in synthesis robots |

| RAFT Agents | Chain-transfer agents (e.g., 2-cyano-2-propylbenzodithioat) for controlled radical polymerization [1] | Provides polymers with specific end-groups for subsequent modification studies |

| Poly(PEGMEMA) | Poly(ethylene glycol) ether methyl methacrylate polymer (Mn = 500 g molâ»Â¹) [1] | A model polymer for studying UV-induced end-group degradation kinetics |

| Custom Photometer | Self-produced sensor with 468 nm LED and TSL2561T light sensor [1] | Allows for automated, in-situ monitoring of reaction progress via absorbance changes |

| Chemspeed SWING XL | Automated parallel synthesizer with overhead robot arm [1] | Serves as the primary robotic platform for executing and monitoring synthetic workflows |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Sensor Integration and Workflow Configuration

- Hardware Installation: Mount the self-produced photometer and the modified UV chamber within the operational envelope of the synthesis robot's overhead robot arm. Ensure the 4-needle head (4-NH) tool can access all critical components for liquid handling.

- System Interfacing: Connect the photometer module to the Raspberry Pi running the LabPi software (Version 0.23). Validate the communication and data logging functionality.

- Workflow Programming: Develop and upload the automated control script to the Chemspeed platform. The script must coordinate the timing of liquid transfers, UV irradiation, and photometric measurements.

The integrated workflow, managed by the host control software, orchestrates the physical actions and data acquisition as follows.

Polymer Synthesis and Automated Monitoring

- Polymer Synthesis: Synthesize the precursor polymers via RAFT polymerization. For poly(PEGMEMA) (P1), use a monomer-to-RAFT-agent-to-initiator ratio ([M]:[CTA]:[I]) of 50:1:0.25 in DMF. Degas the reaction mixture by flushing with nitrogen for 30 minutes and conduct the polymerization at 70°C for 17 hours [1].

- Automated Sampling and Analysis:

- The synthesis robot's arm automatically collects an aliquot from the reaction vessel.

- The aliquot is transferred to the UV chamber for a defined period of irradiation.

- After irradiation, the robot transfers the sample to the integrated photometer's cuvette for absorbance measurement at 468 nm.

- The LabPi system records the absorbance value, which correlates with the concentration of the light-absorbing dithioester end-group.

- Data Interpretation and Feedback: The collected absorbance data is processed by the control software. A significant decrease in absorbance indicates successful end-group degradation. This real-time data can be used to make heuristic decisions, such as determining the optimal irradiation time for complete conversion or identifying reaction failures for automatic termination.

Results and Performance Data

The implemented system successfully monitored the kinetics of the RAFT end-group degradation. The quantitative data revealed distinctly different reaction profiles for the two polymers studied [1]. This highlights the system's capability to capture nuanced chemical information in real-time.

Table 3: Kinetic Data from Automated RAFT End-Group Degradation Monitoring

| Polymer | Key Observation from Real-Time Data | Implication for Process Control |

|---|---|---|

| Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) | Immediate decrease in absorbance upon UV exposure [1] | Process can be designed for short, rapid reaction cycles. |

| Poly(ethylene glycol) ether methyl methacrylate (Poly(PEGMEMA)) | Long initiation time (~20 minutes) required before significant degradation observed [1] | Process must account for a delay before the main reaction commences to avoid under-processing. |

General Protocol for Integrating Tailor-Made Sensors

Sensor Selection and Design Phase

- Define the Measurand: Clearly identify the physical or chemical parameter to be monitored (e.g., absorbance, temperature, pressure, conductivity) [1].

- Assess Constraints: Evaluate the synthesis robot's internal space, available power, data communication ports, and chemical compatibility. The sensor footprint is often the primary limiting factor [1].

- Select a Transduction Mechanism: Choose a sensing principle that balances accuracy, cost, and ease of integration. For lunar applications, this involves using locally available materials like aluminium for potentiometers or quartz for piezoelectric sensors [20].

System Integration and Data Fusion Phase

- Hardware Integration: Physically mount the sensor and ensure it is accessible by the robot's manipulation tools. For electrical sensors, establish a connection to a data acquisition system (e.g., Raspberry Pi, Arduino) [1].

- Software Development: Write drivers for the sensor and integrate it into the robot's main control software. This often involves creating custom Python scripts for data acquisition and instrument control [16].

- Implement Data Fusion: When using multiple sensors, employ algorithms (e.g., Kalman filters) to combine these data streams into a coherent and accurate state estimation. This is crucial for reliable decision-making in complex processes like WAAM [17] [18].

Closed-Loop Control Implementation

- Develop a Decision-Maker: Implement a control logic, which can range from simple heuristics defined by domain experts [16] to sophisticated machine learning models like convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for image-based monitoring [18].

- Establish the Control Loop: Ensure the output of the decision-maker is fed back to the synthesis robot's actuators to modify the process parameters (e.g., temperature, reagent flow) in real-time, completing the autonomous cycle [17] [16].

The implementation of tailor-made sensors in synthesis robots represents a frontier in automated drug development and materials research. This integration faces a fundamental challenge: the hardware-software gap that separates custom physical sensing devices from the computational systems that must process their data. Single-board computers (SBCs) have emerged as pivotal tools in bridging this divide, serving as the central nervous system for next-generation automated synthesis platforms.

The global SBC market, valued at USD 3.01 billion in 2023 and projected to reach USD 4.47 billion by 2032, reflects the growing adoption of these compact computing solutions across research and industrial applications [21]. This growth is largely driven by the expansion of industrial automation and IoT technologies, both central to modern laboratory automation systems. SBCs provide the ideal platform for sensor integration due to their balance of computational capability, physical input/output interfaces, and software flexibility within compact form factors.

SBC Ecosystem and Selection Criteria for Sensor Integration

SBC Market and Processor Landscape

Selecting the appropriate SBC requires understanding the available processor architectures and their suitability for sensor integration tasks. The market offers several processor families, each with distinct advantages for research applications.

Table 1: Single-Board Computer Processor Architectures and Characteristics

| Processor Type | Architecture | Key Advantages | Typical Applications in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| X86 [21] | Complex Instruction Set Computing (CISC) | Broad software compatibility; runs Windows and Linux; high performance for complex computations | Data-intensive processing; legacy instrument integration |

| ARM [21] | Reduced Instruction Set Computing (RISC) | Low power consumption; cost-effective; minimal heat generation | Portable sensor platforms; continuous monitoring systems |

| ATOM [22] | CISC (Intel) | Balance of performance and power efficiency | Embedded laboratory equipment; mid-range automation tasks |

| PowerPC [22] | RISC | High reliability; deterministic performance | Mission-critical synthesis control systems |

Interface Standardization Challenges

The SBC ecosystem faces significant interface standardization challenges, with multiple de facto standards having emerged organically rather than through coordinated design efforts [23]. The Raspberry Pi 40-pin header has become a common interface for Linux-capable boards, though its pin arrangement is suboptimal due to the platform's evolution from a simple educational tool to an industrial workhorse [23]. Similarly, Arduino shield interfaces organized I/O lines logically but required widely-spaced headers that consume substantial space [23].

For synthesis robotics applications, the selection of an SBC with appropriate physical interfaces is critical. Standard 2.54mm pin headers provide the best balance of accessibility, cost, and connector availability [23]. The ideal SBC interface for sensor integration would group digital GPIO, analog inputs, and standard communication protocols (SPI, I2C, UART) sequentially while providing clean power sources at multiple voltages.

Implementation Framework: Custom Sensor Integration with SBCs

Hardware-Software-Wetware Codesign Principle

A transformative approach for synthesis robotics is the hardware-software-wetware codesign paradigm, where biological systems (wetware), automation hardware, and control software are developed through an integrated methodology [24]. In this framework, SBCs act as the unifying element that translates high-level experimental specifications into physical operations while simultaneously acquiring sensor data from the chemical or biological processes.

This codesign approach enables researchers to create "genetic compilers" that transform experimental specifications into executable protocols running on automated synthesis platforms [24]. The SBC functions as the central controller that manages this translation process while ensuring data acquisition from custom sensors monitors reaction progress and conditions.

SBC Operating System Selection: Android vs. Linux

The choice between operating systems represents a significant consideration for sensor integration projects. While Linux has traditionally dominated scientific applications, Android SBCs are gaining traction in specific use cases.

Table 2: Android vs. Linux SBCs for Sensor Integration Applications

| Feature | Android SBC [25] | Linux SBC [25] |

|---|---|---|

| User Interface Development | Rapid development with Android Studio; rich UI support | More coding-intensive; typically uses Qt or LVGL |

| Multimedia Support | Excellent with built-in APIs and hardware acceleration | Good but requires additional configuration |

| Boot Speed | Slower (10-20 seconds) | Faster (2-5 seconds) |

| Developer Community | Massive mobile developer pool | Smaller, more specialized in embedded systems |

| Stability | Mature with Android 11+; reliable OTA updates | Traditionally strong in system-level stability |

| Sensor Integration | Standardized sensor APIs; simplified data acquisition | Direct hardware access; flexible driver development |

For synthesis robotics, Linux SBCs typically provide advantages due to their faster boot times, system stability, and direct hardware access capabilities. However, Android SBCs may be preferable for applications requiring sophisticated touch interfaces for operator interaction or when leveraging existing Android-compatible sensor hardware.

Experimental Protocols for Sensor Integration

Protocol 1: Capacitive Tactile Sensor Integration for Synthesis Monitoring

Purpose: To integrate soft capacitive tactile sensors with SBCs for real-time monitoring of physical interactions in synthesis robots.

Background: Capacitive tactile sensors provide valuable feedback in automated synthesis systems, enabling detection of physical contacts, material properties assessment, and process verification [26]. These sensors are particularly valuable for monitoring mechanical interactions in solid-phase synthesis, crystallization processes, or handling of delicate materials.

Materials:

- Single-board computer (Raspberry Pi 4 or similar with SPI interface)

- Custom capacitive tactile sensor array [26]

- SPI analog-to-digital converter (MCP3008 or similar)

- 3.3V to 5V logic level shifter (if required)

- Python libraries: spidev, numpy, matplotlib

- Flexible printed circuit cabling

Methodology:

- Sensor Physical Integration:

- Mount the capacitive tactile sensor on the synthesis robot's end effector or reaction vessel interface

- Route flexible cabling to minimize movement interference and electromagnetic noise

- Implement strain relief at sensor connection points

Electrical Interface:

- Connect sensor output to SPI ADC using the following pin mapping:

- SBC MOSI → ADC DI

- SBC MISO → ADC DO

- SBC SCLK → ADC CLK

- SBC CE0 → ADC CS/SHDN

- Provide stable 3.3V power supply with appropriate decoupling capacitors

- Implement reference voltage filtering for ADC

- Connect sensor output to SPI ADC using the following pin mapping:

Software Implementation:

Data Interpretation:

- Establish baseline capacitance values for non-contact state

- Implement threshold detection for contact events

- Correlate capacitance patterns with physical process outcomes

- Log tactile data alongside other synthesis parameters

Validation:

- Verify sensor response using standardized calibration weights

- Confirm reproducibility across multiple synthesis cycles

- Correlate sensor readings with visual inspection of interactions

Protocol 2: Polymer-Based Wearable Sensor Integration for Bioprocess Monitoring

Purpose: To interface polymer-based wearable chemical sensors with SBCs for real-time monitoring of bioreactor conditions or in vitro synthesis environments.

Background: Wearable polymer sensors provide flexible, conformable sensing platforms for biochemical monitoring [11]. These sensors can be adapted to bioreactor surfaces or integrated into flow systems to monitor reaction progress, metabolite production, or environmental conditions.

Materials:

- ARM-based SBC (preferably with Bluetooth Low Energy capability)

- Polymer-based chemical sensor [11]

- Signal conditioning circuit (instrumentation amplifier, filter)

- ADC interface (built-in or external)

- Python libraries: pySerial, matplotlib, scipy

Methodology:

- Sensor Preparation:

- Select appropriate polymer sensor based on target analyte (conductive polymers for biochemical sensing)

- Characterize sensor response curve to target analyte in controlled conditions

- Encapsulate sensor elements for protection from liquid medium while maintaining analyte permeability

Electronic Interface:

- Design signal conditioning circuit appropriate for sensor type:

- Piezoresistive sensors: Wheatstone bridge configuration

- Chemical sensors: potentiostatic circuits for electrochemical detection

- Implement appropriate filtering for noise reduction

- Calibrate sensor output against known standards

- Design signal conditioning circuit appropriate for sensor type:

Data Acquisition Software:

Process Integration:

- Correlate sensor readings with offline analytical measurements (HPLC, MS)

- Establish control algorithms for process adjustment based on sensor data

- Implement data logging integrated with overall synthesis documentation

Validation:

- Compare sensor readings with reference analytical methods

- Establish sensor stability over extended operation periods

- Verify sensor specificity in complex reaction mixtures

Visualization: Sensor Integration Architecture

The following diagram illustrates the information flow and system architecture for SBC-based custom sensor integration in synthesis robotics:

Diagram 1: SBC-Based Sensor Integration Architecture for Synthesis Robotics

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Components for SBC-Sensor Integration

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for SBC-Sensor Integration

| Component | Function | Example Products/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| ARM-based SBC [21] | Central computation and control unit for sensor data processing | Raspberry Pi 4, NVIDIA Jetson Nano, Rockchip-based boards |

| Capacitive Tactile Sensor [26] | Measures physical interactions and contact forces in synthesis processes | Custom soft capacitive sensors with elastomeric dielectric layers |

| Polymer-Based Chemical Sensors [11] | Detects specific analytes or environmental conditions in reaction mixtures | Conductive polymer composites, molecularly imprinted polymers |

| Analog-to-Digital Converter | Converts continuous analog sensor signals to digital values for SBC processing | MCP3008 (8-channel, 10-bit, SPI interface), ADS1115 (16-bit, I2C interface) |

| Signal Conditioning Circuits | Amplifies, filters, and prepares sensor signals for accurate measurement | Instrumentation amplifiers, active filters, voltage references |

| Communication Protocol Libraries | Enables data exchange between SBC and sensors | Python spidev (SPI), smbus2 (I2C), pySerial (UART) |

| Data Visualization Tools | Presents sensor data in interpretable formats for researchers | Matplotlib, Plotly, Grafana dashboards |

| DL-Alanine (Standard) | DL-Alanine (Standard), CAS:25840-83-9, MF:C3H7NO2, MW:89.09 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 1H,1H,2H,2H-Perfluorodecanesulfonic acid | 1H,1H,2H,2H-Perfluorodecanesulfonic acid, CAS:39108-34-4, MF:C8F17CH2CH2SO3H, MW:528.18 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The integration of single-board computers with custom interfaces represents a transformative approach for implementing tailor-made sensors in synthesis robotics. This hardware-software bridge enables researchers to create highly adaptive, data-rich experimental platforms that can accelerate discovery in drug development and materials science.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on several key areas. The ongoing miniaturization of electronic components will enable even more compact SBCs with greater processing power for sensor data analysis [21]. The emergence of standardized interface protocols could simplify the integration of diverse sensor types [23]. Additionally, the growing maturity of Android-based SBCs provides alternative development pathways for applications requiring sophisticated user interfaces [25].

Most importantly, the hardware-software-wetware codesign paradigm [24] points toward a future where biological specifications, sensor systems, and robotic platforms are developed concurrently rather than sequentially. This approach, enabled by the flexible interface capabilities of modern SBCs, will ultimately yield more efficient and effective automated synthesis systems for research and development.

From Concept to Lab Bench: Methodologies for Implementing Custom Sensors in Research Robots

The integration of automated synthesizers has revolutionized chemical research by enabling high-throughput experimentation. A critical challenge remains the implementation of online characterization tools that fit the spatial and financial constraints of most laboratories. This application note provides a detailed protocol for constructing and implementing a low-cost, self-produced photometer within a synthesis robot. This approach, framed within broader thesis research on tailor-made sensors, enables automated sampling and real-time reaction monitoring, transforming a standard automated synthesizer into a more autonomous discovery platform [15] [6]. We demonstrate its application in monitoring the UV-induced end-group degradation of polymers, a key reaction in polymer chemistry.

The Self-Produced Photometer: Assembly and Configuration

This section details the construction of a low-cost photometer, with core components selected for performance, affordability, and compatibility with standard data acquisition systems.

Core Components and Assembly

The photometer is built around a single-board computer and modular sensor components. The key items are listed in Table 1.

Table 1: Key Components of the Low-Cost Photometer

| Component Category | Specific Example / Specification | Function / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Board Computer | Raspberry Pi 3 Model B+ [15] | Runs the operating system and LabPi control software. |

| Photometer Sensor | TSL2591 breakout board [27] | Measures light intensity with high precision; I2C address 0x29. |

| Light Source | 5 mm Blue LED (468 nm) [15] | Provides a monochromatic light source for absorption measurements. |

| Cuvette | Semimicro quartz glass cuvette (1.4 mL max volume) [15] | Holds the sample for analysis; quartz allows for a broad range of wavelengths. |

| Software | LabPi software (Version 0.23) [15] | Python-based program for operating the sensor and recording data. |

The physical housing for the photometer can be constructed from laser-cut 3 mm acrylic sheets, designed with grooves and tongues for glue-free assembly [27]. The assembly involves:

- Sensor Mounting: Solder a header to the TSL2591 breakout board and connect cables to the Ground, Vin (3.3V), SDA, and SCL ports. Fix the sensor to a holding plate using 2.5M screws, ensuring the sensor chip is aligned with a rectangular hole in the plate for the light path [27].

- LED Assembly: Place a 5 mm LED of the desired wavelength (e.g., 468 nm) into a stacked holder element. Use an appropriate series resistor (e.g., 60 Ω for certain LEDs) to control the voltage. Connect the cables, with the longer wire to positive and the shorter to ground [15] [27].

- Final Assembly: Mount the sensor and LED units onto the inner walls of the laser-cut acrylic housing. Ensure the LED and sensor are precisely aligned on opposite sides of the cuvette chamber. Connect all cables to the corresponding ports on the Raspberry Pi.

Software and Data Acquisition

The system operates on the Raspberry Pi OS. The I2C communication protocol must be activated to allow the Raspberry Pi to communicate with the photometer sensor [27]. After installing the LabPi software, the photometer can be calibrated and controlled. The software allows for continuous data logging, recording the light intensity transmitted through the sample, which can be used to calculate absorbance.

System Integration with a Synthesis Robot

For autonomous operation, the self-built photometer must be physically installed and digitally integrated into a synthesis robot workflow.

Physical Integration and Workflow Automation

The compact size of the self-produced photometer is a key advantage, allowing it to be placed within the limited free space inside an automated synthesizer, such as a Chemspeed SWING XL or ISynth model [15] [16]. The integration workflow, which enables autonomous reaction monitoring, is illustrated below.

The synthesizer's robotic arm, equipped with a needle head for liquid handling, is programmed to automatically withdraw aliquots from the reaction vessel at set time points. The sample is transferred to the quartz cuvette housed within the photometer for analysis [15]. This process eliminates the need for manual sampling and enables real-time kinetic studies.

Application Example: Monitoring RAFT End-Group Degradation

To validate the system, it was used to monitor the UV-induced cleavage of the trithiocarbonate end-group from two different polymers: poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) and poly(ethylene glycol) ether methyl methacrylate (poly(PEGMEMA)) [15] [6]. The loss of the colored end-group results in a decrease in absorbance at 468 nm, which is directly measured by the photometer.

Experimental Protocol:

- Polymer Synthesis: Synthesize the precursor polymers via reversible addition–fragmentation chain-transfer (RAFT) polymerization.

- Reagents: Methyl methacrylate (MMA) or PEGMEMA monomer, chain-transfer agent (e.g., 2-cyano-2-propylbenzodithioate), initiator (e.g., AIBN), and dimethylformamide (DMF) solvent [15].

- Procedure: Prepare a reaction mixture with a monomer-to-CTA-to-initiator ratio of 200:1:0.25 in a round-bottom flask. Degas by flushing with nitrogen for 30 min. Conduct solution polymerization at 70 °C for 17 h. Purify the resulting polymer via dialysis [15].

- Photometric Monitoring:

- Setup: Place a solution of the RAFT polymer (e.g., 5 mg/mL) in a suitable solvent into a reaction vial inside the synthesis robot. Position the vial under a UV chamber (e.g., UVACUBE 100) for irradiation [15].

- Automated Analysis: Program the robot to periodically withdraw a sample, transfer it to the photometer's cuvette, and record the absorbance at 468 nm.

- Kinetic Analysis: The collected data reveals reaction kinetics, showing, for instance, an immediate decrease in absorbance for PMMA versus a 20-minute initiation time for poly(PEGMEMA) [15] [6].

Validation and Performance

The data obtained from the low-cost photometer must be validated against established analytical techniques to confirm its reliability.

Orthogonal Characterization

In the referenced study, all samples measured by the self-produced photometer were also analyzed using size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) equipped with both UV and refractive index (RI) detectors [15]. This orthogonal validation confirmed the accuracy of the photometer's readings and allowed for correlation of end-group loss with changes in molar mass.

Performance Characteristics

The performance of such low-cost photometers is suitable for many laboratory monitoring applications. Quantitative performance data from a similar portable photometer system is shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of a Low-Cost Photometric System

| Parameter | Reported Performance | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Linearity | High linearity demonstrated [28] | Validation against laboratory UV-vis spectrophotometry. |

| Detection Limits | Phosphate: 0.016 mg Lâ»Â¹; Iron: 0.020 mg Lâ»Â¹ [28] | Based on field tests for water quality analysis. |

| Accuracy (Recovery %) | 95 ± 3 % to 107 ± 3 % [28] | Comparison with standard methods like ion chromatography. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for RAFT Polymerization and Monitoring

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Chain Transfer Agent (CTA) | Controls the radical polymerization, yielding polymers with low dispersity and a characteristic colored end-group. |

| Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) | A common thermal initiator to start the RAFT polymerization process. |

| Dimethylformamide (DMF) | Anhydrous solvent used for the polymerization reaction. |

| UV Chamber | Provides the UV light source required to initiate the cleavage of the RAFT end-group. |

| Piboserod hydrochloride | Piboserod hydrochloride, CAS:178273-87-5, MF:C22H32ClN3O2, MW:406.0 g/mol |

| Mesulergine hydrochloride | Mesulergine hydrochloride, CAS:72786-12-0, MF:C18H27ClN4O2S, MW:399.0 g/mol |

This application note provides a comprehensive blueprint for implementing a low-cost, self-produced photometer within an automated synthesis environment. By following the detailed protocols for construction, integration, and validation, researchers can significantly enhance their high-throughput experimentation capabilities, enabling automated, real-time monitoring of chemical reactions. This approach aligns with the growing trend of developing tailor-made, modular sensors to create more intelligent and autonomous research platforms [15] [16].

Reversible Addition-Fragmentation Chain Transfer (RAFT) polymerization is a pivotal form of controlled radical polymerization, enabling the synthesis of polymers with predefined molecular weights, narrow dispersity, and complex architectures [29]. However, the real-time monitoring of RAFT kinetics presents a significant challenge, requiring precise analytical techniques that are often difficult to integrate into automated synthesis workflows [30]. This application note details a novel approach in which a low-cost, self-produced LabPi digital measuring station is successfully implemented within a Chemspeed SWING XL automated synthesizer to enable online characterization of photoinduced RAFT end-group degradation [15]. This case study, framed within broader research on tailor-made sensors for synthesis robots, demonstrates how this integrated system provides automated, high-throughput experimentation capabilities, revealing distinct kinetic profiles for different polymer types that are validated against size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues the essential materials and reagents used in the featured experimental workflow, along with their specific functions [15].

Table 1: Key Research Reagents and Materials

| Item Name | Function/Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Poly(PEGMEMA) (Mn = 500 g molâ»Â¹) | Model polymer for RAFT end-group degradation studies | Sigma Aldrich (Merck KGaA) |

| Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) | Model polymer for RAFT end-group degradation studies | Synthesized in-house via RAFT |

| 2-cyano-2-propylbenzodithioat (CPDB) | Chain-transfer agent (RAFT agent) | Sigma Aldrich (Merck KGaA) |

| Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) | Thermal radical initiator | Sigma Aldrich (Merck KGaA) |

| Dimethylformamide (DMF) | Dry, anhydrous solvent for polymerizations | Acros Organics (Thermo Fisher Scientific) |

| Tetrahydrofuran (THF) | Solvent for dialysis and SEC | VWR |

| S,S-dibenzyl trithiocarbonate | Example of a trithiocarbonate-type RAFT agent | Fujifilm Wako [31] |

| Spiperone hydrochloride | Spiperone hydrochloride, CAS:2022-29-9, MF:C23H27ClFN3O2, MW:431.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Xanthine amine congener | Xanthine amine congener, CAS:96865-92-8, MF:C21H28N6O4, MW:428.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

System Integration & Workflow

The core of this case study is the seamless integration of a custom sensor into a commercial automated synthesizer, creating a closed-loop system for synthesis and analysis.

The LabPi Measuring Station

The LabPi system is a modular, digital measuring station built around a Raspberry Pi single-board computer and a custom adapter board that supports various sensor modules [15] [32]. For this application, the key sensor is a photometer equipped with a blue light-emitting diode (LED) emitting at 468 nm and a corresponding light sensor (AMS TSL2561T). The system uses a semimicro-quartz glass cuvette with a maximum volume of 1.4 mL and is operated via the LabPi software platform [15].

Integration with the Synthesis Robot

The LabPi photometer was physically implemented inside the Chemspeed SWING XL synthesizer. A modified UV chamber (UVACUBE 100) was incorporated to facilitate the photoinduced reactions. The synthesizer's overhead robotic arm, equipped with a 4-needle head (4-NH) for liquid handling, was programmed to automatically draw samples from the reaction vessels and transfer them to the LabPi's cuvette for analysis [15]. This integration enables automated, periodic sampling and online characterization without human intervention.

Experimental Workflow Logic

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence of the automated synthesis and monitoring workflow.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Synthesis of Precursor Polymers (P1 & P2)

Two polymers were synthesized as substrates for the end-group degradation study [15].

- Reagent Preparation: In a round bottom flask, prepare solutions of the initiator (AIBN), chain-transfer agent (CPDB), and monomer in dry DMF. The studied molar ratios were:

- P1 (poly(PEGMEMA)): [M]:[CTA]:[I] = 50:1:0.25

- P2 (PMMA): [M]:[CTA]:[I] = 200:1:0.25

- Degassing: Seal the reaction vessel with a septum and degas the mixture by purging with nitrogen gas for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Polymerization: Place the flask in a preheated oil bath at 70 °C and allow the reaction to proceed for 17 hours.

- Purification: Purify the resulting polymers via dialysis in THF, exchanging the solvent five times over 60 hours. Finally, dry the polymers in vacuo.

- Characterization: Verify the polymer structure and purity using (^1)H NMR and determine the initial molecular weight and dispersity using SEC.

Automated Kinetics Monitoring Protocol

This protocol details the automated setup for monitoring the UV-induced cleavage of the RAFT end-group [15].

- System Initialization: Power on the Chemspeed SWING XL synthesizer and the integrated LabPi system. Ensure the LabPi software is running and the photometer baseline is stable.

- Sample Loading: Using the synthesizer's robotic arm, prepare solutions of the purified polymers (P1 or P2) in an appropriate solvent and load them into reaction vessels within the synthesizer.

- UV Chamber Modification: Integrate a UVACUBE 100 chamber equipped with a mercury lamp into the synthesizer's workspace. Position the reaction vessels so they can be shuttled in and out of the UV chamber by the robot arm.

- Programming the Workflow: Program the Chemspeed robot to execute the following loop: a. Transfer a reaction vessel to the UV chamber and initiate irradiation. b. At defined time intervals (e.g., every 5 minutes), the robot arm automatically withdraws a small aliquot from the reaction vessel. c. The aliquot is dispensed into the quartz cuvette of the LabPi photometer. d. The photometer measures the absorbance at 468 nm. e. The data is automatically recorded and timestamped by the Raspberry Pi. f. The cuvette is cleaned automatically in preparation for the next sample.

- Termination: The monitoring cycle continues until a predetermined endpoint, such as no significant change in absorbance over multiple cycles, is reached.

Data Analysis and Validation

- Kinetic Analysis: Plot the photometer absorbance data against time to generate kinetic profiles for the end-group degradation.

- SEC Validation: After the automated run, manually characterize all photometric samples using SEC with dual UV and RI detectors. This confirms the photometer results and allows for investigation of the molar mass shift during the reaction [15].

Results & Data Analysis

The integrated LabPi system successfully provided quantitative kinetic data, revealing distinct behaviors for the two polymers under investigation.

Kinetic Profiles from Photometry

The automated sampling and photometric analysis clearly differentiated the reaction kinetics of poly(PEGMEMA) and PMMA.

Table 2: Summary of Kinetic Results from LabPi Photometry

| Polymer | Observed Kinetic Profile | Key Kinetic Parameter |

|---|---|---|

| Poly(PEGMEMA) (P1) | Long initiation period followed by degradation | Initiation time ≈ 20 minutes |

| PMMA (P2) | Immediate commencement of degradation | No observable initiation time |

The data indicates that the RAFT end-group of PMMA is immediately susceptible to UV cleavage, whereas the end-group of poly(PEGMEMA) requires a 20-minute initiation period before degradation begins in earnest [15].

Analytical Validation

The results obtained from the low-cost LabPi sensor were corroborated by traditional offline analytics. SEC analysis with both UV and RI detectors confirmed the degradation trend observed by the photometer and provided additional data on the concomitant shift in molar mass, validating the accuracy and reliability of the integrated online system [15].

System Architecture Diagram

The diagram below illustrates the physical and data integration of the various components within the automated platform.

Discussion & Outlook

This case study demonstrates that low-cost, self-produced sensors like the LabPi platform can be effectively integrated into commercial synthesis robots to enable sophisticated online reaction monitoring. This approach significantly enhances the capability for high-throughput experimentation (HTE) by providing real-time kinetic data, reducing the need for manual sampling and offline analysis [15]. The findings align with broader trends in laboratory automation, where mobile robots are being used to bridge standalone instruments into cohesive, autonomous workflows [16] and where custom light-emitting systems are being developed for precise spatial and temporal control of photopolymerizations [33].

The success of this integrated system opens the door for more complex autonomous operations. Future work could focus on implementing feedback control, where the kinetic data from the LabPi sensor is used by the synthesis robot to automatically adjust reaction parameters—such as UV irradiation time or temperature—in real-time to achieve a desired endpoint. Such advancements, part of the growing field of "self-driving labs," promise to dramatically accelerate the discovery and optimization of new polymeric materials [16] [33].

The integration of in-line spectroscopy with automated synthesis robots represents a paradigm shift in chemical research and development. This synergy creates a closed-loop system capable of both executing and intelligently optimizing chemical processes in real-time. By embedding analytical techniques such as HPLC, Raman, and NMR directly into the synthetic workflow, researchers can transition from static, pre-programmed protocols to dynamic, self-correcting, and adaptive experimentation [34]. This is particularly transformative for the pharmaceutical industry, where it accelerates the critical Design-Make-Test-Analyse (DMTA) cycle by providing immediate feedback on reaction outcomes [35]. Within the broader context of implementing tailor-made sensors in synthesis robots, this integration moves beyond simple process monitoring to achieve genuine autonomous process control, enabling the safe scale-up of exothermic reactions, the discovery of new chemical entities, and the rapid optimization of complex reaction conditions with minimal human intervention [34] [16].

Technological Foundations

The effective coupling of spectroscopy with synthesis robots relies on a cohesive ecosystem of hardware, software, and data management.

Core Hardware Components

The hardware architecture typically centers on an automated synthesis platform, such as a Chemspeed ISynth or a Chemputer system, which performs the physical manipulations of the chemical process [34] [16]. These platforms are physically or digitally connected to a suite of analytical instruments:

- In-line HPLC (High-Performance Liquid Chromatography): Often coupled with mass spectrometry (MS) or diode-array detection (DAD), it provides quantitative data on reaction conversion, yield, and impurity profiles [34] [36].

- In-line Raman Spectroscopy: A non-invasive technique that uses a probe immersed in the reaction mixture to provide real-time vibrational data on molecular composition and concentration, ideal for tracking key intermediates and endpoints [34] [37] [38].

- In-line NMR (Nuclear Magnetic Resonance): Benchtop NMR spectrometers offer structural elucidation capabilities, confirming product identity and isomeric composition directly from the reaction stream [34] [16].

Notably, a modular approach using mobile robots for sample transportation allows these analytical instruments to be shared resources within a laboratory, operating alongside human researchers without requiring extensive, permanent hardware integration [16].

Software and Data Integration

The true power of this integration is unlocked by sophisticated software that orchestrates the entire workflow. A dynamic programming language, such as χDL (XDL) for the Chemputer, defines not just a sequence of steps but also incorporates conditional logic based on real-time sensor input [34]. This enables self-correcting procedure execution.

Software packages like AnalyticalLabware provide a unified interface for controlling diverse analytical instruments from various manufacturers, standardizing data acquisition, and pre-processing spectral data (e.g., peak picking, baseline correction) [34]. Finally, optimization algorithms—ranging from Bayesian optimization to heuristic decision-makers—process the analytical results to suggest the next set of reaction conditions, thereby closing the loop [34] [16]. This entire data pipeline adheres to FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable), ensuring that every protocol and its resulting data can be reproduced and verified [35].

Application Notes: Key Use Cases and Quantitative Outcomes

The integrated platform has demonstrated significant value across a range of complex chemical challenges. The table below summarizes key experimental outcomes and performance metrics.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of Integrated Spectroscopy-Robot Systems in Reaction Optimization and Discovery

| Application / Reaction Type | Integrated Analytical Techniques | Key Performance Metrics | Reported Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Van Leusen Oxazole & Manganese-catalysed Epoxidation [34] | In-line HPLC, Raman, NMR | 25-50 optimization iterations | Up to 50% yield improvement over baseline conditions |

| Multi-step Structural Diversification [16] | UPLC-MS, Benchtop NMR | Binary pass/fail grading of orthogonal data | Autonomous identification and scale-up of successful substrates for library synthesis |

| Supramolecular Host-Guest Chemistry [16] | UPLC-MS, Benchtop NMR | Heuristic analysis of complex product mixtures | Successful discovery and functional assay of self-assembled structures |

| Real-time Product Quality Monitoring [37] | In-line Raman Spectroscopy | Data collection every 38 seconds | Accurate measurement of protein aggregation and fragmentation during bioprocessing |

| Explorative Trifluoromethylation [34] | In-line HPLC, Raman, NMR | Experimental discovery pipeline | Discovery of new molecules from a selected chemical space |

Protocol: Closed-Loop Reaction Optimization

This protocol outlines the procedure for autonomously optimizing a chemical reaction, such as the Van Leusen oxazole synthesis or a manganese-catalysed epoxidation [34].

Step 1: Initial Setup and Parameter Definition

- Translate Literature Procedure: Convert a literature-based synthetic procedure into a dynamic χDL (or equivalent) script, defining the reaction steps, variable parameters (e.g., temperature, stoichiometry, concentration), and the analytical sampling routine [34].

- Configure Hardware Graph: Map all physical components (synthesis robot, HPLC, Raman probe, NMR spectrometer) and their connections within the control software [34].

- Define Optimization Goal and Algorithm: Specify the objective (e.g., maximize yield, minimize impurities) and select an optimization algorithm (e.g., from the Summit or Olympus frameworks) [34].