Synthesis and Biomedical Applications of Inorganic Cluster Supramolecular Compounds: From Design Principles to Advanced Therapeutics

This comprehensive review explores the synthesis, functionalization, and burgeoning biomedical applications of inorganic cluster supramolecular compounds (ICSs).

Synthesis and Biomedical Applications of Inorganic Cluster Supramolecular Compounds: From Design Principles to Advanced Therapeutics

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the synthesis, functionalization, and burgeoning biomedical applications of inorganic cluster supramolecular compounds (ICSs). Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it delves into the foundational design principles of these architectures, including metallacages and coordination complexes, established through coordination chemistry and self-assembly. The article details advanced synthetic methodologies and characterization techniques, highlighting their application in anticancer drug development, targeted drug delivery, bioimaging, and catalysis. It further addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for stability and reproducibility. Finally, a comparative analysis validates ICSs against traditional materials, evaluating their performance, biocompatibility, and clinical potential to inform future therapeutic innovation.

Core Concepts and Design Principles of Inorganic Cluster Supramolecules

Inorganic Cluster Supramolecular Compounds (ICSs) represent a advanced class of structures formed via coordination-driven self-assembly between metal-containing nodes and organic ligands. These compounds, also broadly classified as Supramolecular Coordination Complexes (SCCs), occupy a strategic position in modern chemistry, bridging the gap between classical supramolecular chemistry and coordination chemistry [1] [2]. The field has evolved significantly since the early discoveries of crown ethers by Pedersen, cryptands by Lehn, and spherands by Cram, which established the fundamental principles of molecular recognition through non-covalent interactions [3] [2]. The integration of metal-ligand coordination bonds, with energies intermediate (15-50 kcal/mol) between covalent bonds (60-120 kcal/mol) and weak non-covalent interactions (0.5-10 kcal/mol), provides the unique combination of structural stability and dynamic reversibility that characterizes ICSs [2]. This dynamic reversibility allows for self-correction during assembly, leading to discrete, thermodynamically stable architectures with precise spatial control [2].

The significance of ICSs extends across multiple disciplines, from catalysis and sensing to materials science and biomedicine [1] [4]. Their structural precision, tunable cavities, and capacity for molecular recognition make them particularly valuable for pharmaceutical applications, where they can function as novel anticancer agents, drug delivery vehicles, theranostic agents, and biosensors [1] [4] [5]. The rational design of these structures leverages the predictable nature of metal-ligand coordination spheres and the geometric preferences of metal ions to create finite two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) architectures with defined shapes and sizes [2].

Structural Classification and Fundamental Characteristics

ICSs can be systematically classified based on their dimensionality and structural features. The primary categories include metallacages (3D structures), helicates (chiral helical structures), and metallacycles (2D cyclic structures).

Metallacages

Metallacages are three-dimensional supramolecular structures that feature an internal cavity accessible to guest encapsulation [1] [6]. These structures belong to the broader class of metallocavitands and exploit host-guest chemistry for various functions and applications [1]. The internal cavity volume can range significantly, with some structures demonstrating flexibility to adapt from 69 ų to 87 ų to accommodate different guest molecules [7]. This adaptability enables metallacages to function as "molecular flasks" that can isolate and stabilize reactive intermediates or facilitate unusual chemical transformations [2]. The host-guest chemistry of 3D self-assembled structures within the metallacages family can be exploited to design novel drug delivery systems for anticancer chemotherapeutics [1] [6].

Helicates

Helicates are chiral supramolecular structures typically formed by two or more organic strands wrapping around metal centers in a helical fashion [8]. The helical structure is governed by the configuration of organic strands at the metal centers, often resulting from interactions between planar chiral building blocks [8]. These structures have been studied extensively for their molecular recognition properties of nucleic acid structures, with possible applications in therapy [1]. Helicates can undergo stereochemical inversion through various mechanisms, such as the Bailar twist, transitioning between enantiomers (ΔΔ⇋ΛΛ) via mesocate intermediates [7]. Recent advancements include the construction of double helicates using planar chiral [2.2]paracyclophane (PCP) derivatives, where the helical structure is dominated by the 3D planar chiral units rather than the metal-coordination centers [8].

Metallacycles

Metallacycles are two-dimensional cyclic structures formed through coordination-driven self-assembly [2]. These structures include various polygons such as squares, rectangles, triangles, and hexagons, with sizes scalable to nanoscopic dimensions [9] [2]. The Fujita group reported 'Pd48L96', the largest discrete self-assembled edge-directed polyhedron, demonstrating the remarkable scalability of these structures [1] [6]. Metallacycles can be designed to incorporate photochromic units like diarylethene, enabling light-triggered reversible structural transformations with potential applications in molecular switches, smart soft materials, and photodynamic therapy [9].

Table 1: Key Structural Features of Major ICS Classes

| ICS Class | Dimensionality | Key Characteristics | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metallacages | 3D | Internal cavity for guest encapsulation, structural flexibility | [Pd6L8] cages, Pillarplexes |

| Helicates | 1D/2D/3D | Chiral helical structures, stereochemical inversion | Double helicates, [Ga2(3)3] helicates |

| Metallacycles | 2D | Cyclic polygons, photoresponsive properties | Molecular squares, triangles, hexagons |

Design Principles and Synthesis Methodologies

The construction of ICSs follows several well-established design principles that leverage the directional nature of metal-ligand coordination bonds.

Directional Bonding Approach

The directional bonding approach represents a fundamental strategy for constructing ICSs, relying on structurally rigid complementary precursor units with predefined bite angles [2]. This method involves combining donor building blocks (organic ligands with specific angular orientations) and acceptor units (metal-containing subunits with fixed coordination angles) in precise stoichiometric ratios [2]. The symmetry and number of binding sites within each precursor unit dictate the final architecture's shape. For instance, molecular squares can be designed through multiple pathways: combining four 90° angular units with four 180° linear units, or a 2:2 assembly of two different 90° angular units [2]. Similarly, 3D polyhedral architectures require combinations of angular and linear subunits with multidentate precursors featuring more than two binding sites [2].

Symmetry Interaction and Molecular Paneling Approaches

The symmetry interaction approach, pioneered by Raymond and others, utilizes the inherent symmetry of building blocks to direct the self-assembly process [2]. This method considers the point group symmetry of both organic ligands and metal complexes to predict the resulting supramolecular architecture. The molecular paneling approach, developed by Fujita and referred to as the "paneling method," employs planar multidentate ligand molecules that form the faces of supramolecular polyhedra upon coordination to convergently oriented metal nodes [1] [6]. This face-directed method contrasts with edge-directed approaches that use banana-shaped ligands to form the edges of SCCs [1].

Subcomponent Self-Assembly

Nitschke introduced the concept of "subcomponent self-assembly," where the actual linker forms in situ through reactions such as imine formation from aldehydes and amines [1] [6]. This approach allows for covalent post-assembly modifications of the SCCs, adding another layer of functionality and complexity [1]. The dynamic covalent chemistry involved in subcomponent self-assembly enables error-checking and self-correction during the formation process, leading to highly defined structures.

Table 2: Quantitative Data on Selected ICS Structures

| ICS Structure | Cavity Volume (ų) | Photoconversion Yield (%) | Energy Transfer Efficiency (%) | Cytotoxicity (IC50) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu2(1o)2 Metallacycle [9] | N/A | ~90 | N/A | N/A |

| Diarylethene Hexagon 6 [9] | N/A | ~100 (vs. 88 for ligand) | N/A | N/A |

| [Fe4(6)6]8+ Tetrahedron [7] | 69-87 (flexible) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| PCP-TPy1/2 Double Helicates [8] | N/A | N/A | Up to 89.3 | N/A |

Experimental Protocols and Characterization Techniques

General Synthesis Procedure for Coordination-Driven Self-Assembly

The synthesis of ICSs typically follows a straightforward procedure involving the combination of metal acceptor and organic donor building blocks in appropriate solvents [9] [8]. A representative protocol for constructing double helicates, as described for PCP-TPy systems, involves stirring diplatinum(II) complexes with complementary dipyridyl ligands in mixed solvents of dichloromethane and acetone at 60°C overnight [8]. These reactions typically proceed in nearly quantitative yields, demonstrating the efficiency and robustness of coordination-driven self-assembly. The preparation process of SCCs usually progresses from synthesizing simple small-molecule components to assembling metallacycles/metallacages, predominantly conducted in organic solvents [5]. For biomedical applications, additional steps are often required to enhance water solubility, either through chemical modification with hydrophilic groups or encapsulation within nanocarriers featuring hydrophilic surfaces [5].

Structural Characterization Techniques

Comprehensive characterization of ICSs requires multiple analytical techniques to confirm structure, purity, and composition:

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: Multidimensional NMR techniques (¹H, ³¹P, DOSY) provide crucial information about molecular structure, symmetry, and purity [9] [8]. Coordination-induced chemical shifts in ¹H NMR (Δδ = 0.02-0.37 ppm for pyridyl protons) and ³¹P NMR (upfield shifts of approximately 4-5 ppm) serve as indicators of successful metal-ligand coordination [8]. DOSY NMR confirms that all proton signals possess the same diffusion coefficient, verifying the formation of discrete assemblies rather than mixtures [8].

Mass Spectrometry: Electrospray Ionization Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry (ESI-TOF-MS) enables the determination of molecular mass and identification of charge states through characteristic peaks corresponding to [M-nPF₆â»]â¿âº species [9] [8]. This technique is particularly valuable for confirming the composition of large supramolecular architectures.

X-ray Crystallography: Single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) provides unambiguous structural information at atomic resolution, allowing precise determination of cavity sizes, molecular geometries, and conformational details [9] [7]. SCXRD has been instrumental in characterizing structures ranging from simple metallacycles to complex metallacages and helicates.

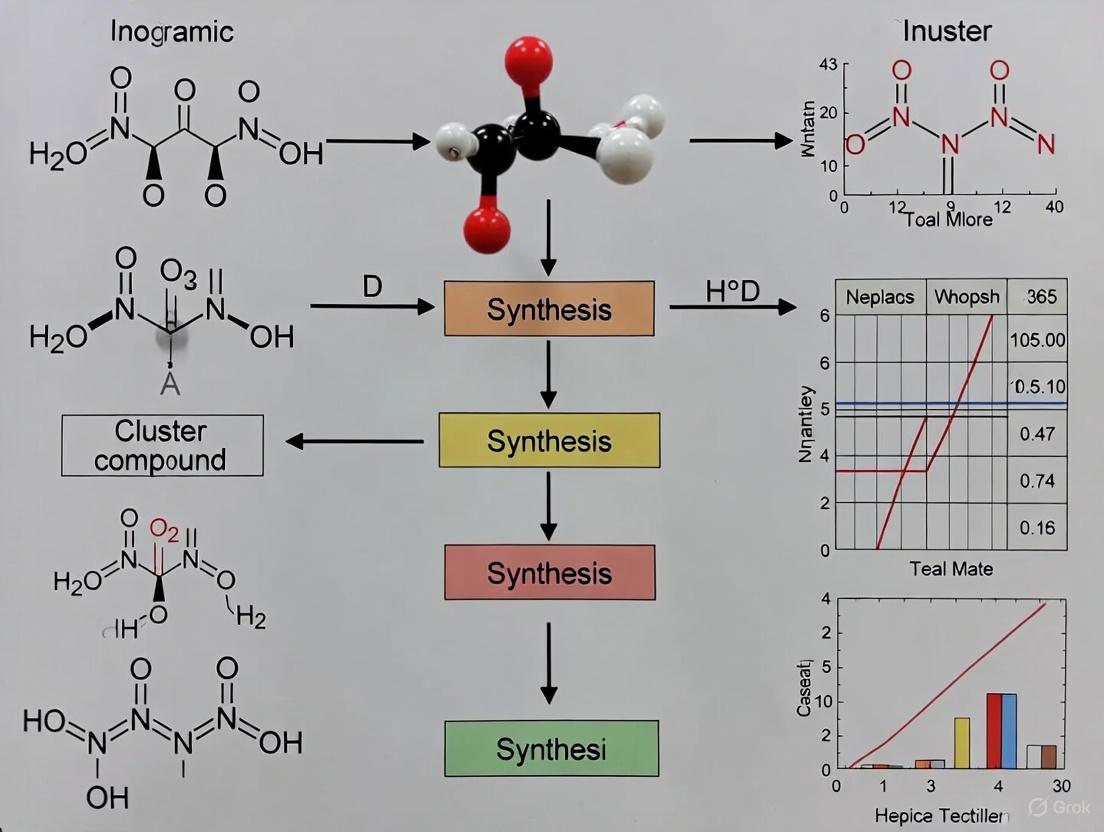

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for ICS Research

Biomedical Applications and Therapeutic Potential

ICSs demonstrate significant potential in biomedical applications, particularly in cancer therapy, diagnostic imaging, and drug delivery systems.

Anticancer Therapeutics

Supramolecular metal-based structures have emerged as novel anticancer agents with mechanisms of action distinct from classical small molecules [1] [6]. These compounds often exhibit cytotoxicity against human cancer cells comparable to or exceeding that of established chemotherapeutics like cisplatin [4]. For example, [Pdâ‚‚Lâ‚„]â´âº metallacages featuring bis-quinoline and bis-isoquinoline-based ligands demonstrated enhanced cytotoxicity against cancer cell lines compared to related pyridyl-based systems [4]. The antiproliferative effects of a self-assembled hexagonal Pd(II) macrocycle against a panel of cancer cell lines were found to be comparable to cisplatin [4]. The robustness and modular composition of supramolecular metal-based structures allow for the incorporation of different functionalities to enable active tumor targeting and stimuli-responsiveness [1].

Drug Delivery Systems

The host-guest chemistry of 3D metallacages can be exploited to design novel drug delivery systems for anticancer chemotherapeutics [1] [6]. Metallacages feature internal cavities accessible to guest encapsulation, making them ideal for drug delivery applications [1]. Hydrophobic Pt(II)-organic cages can be formulated using nanoprecipitation techniques to enhance their bioavailability [4]. Encapsulation strategies can also reduce the toxicity of therapeutic agents; for instance, Q[10] encapsulation enhanced the pharmacokinetics of Ru(II) complexes, potentially enabling their use as antimicrobial agents [4]. The inherent flexibility of MOCs allows them to adapt their internal cavity to better accommodate guest molecules, exhibiting behavior analogous to the induced-fit mechanism of enzymes [7].

Theranostic Agents

ICSs constitute ideal scaffolds for developing multimodal theranostic agents that combine therapeutic and diagnostic capabilities [1] [6]. The modular composition of supramolecular metal-based structures allows for the incorporation of imaging functionalities alongside therapeutic components [1]. Photoactive cages and capsules in which either the metal ion complexation or the bridging ligand are endowed with luminescence properties can be exploited for designing novel imaging agents, as well as for sensing and photoactivation in biological systems [1] [6]. Systems incorporating aggregation-induced emission (AIE) units like tetraphenylethylene (TPE) can overcome aggregation-caused quenching (ACQ) and the heavy atom effect on fluorescence imaging, facilitating the construction of efficient theranostic platforms [5].

Current Challenges and Research Directions

Despite the significant progress in ICS research, several challenges remain to be addressed before widespread clinical translation can be realized.

Water Solubility and Biocompatibility

The inherent hydrophobicity of many ICSs poses challenges for biomedical applications in aqueous physiological environments [5]. Most SCCs are constructed from hydrophobic components in organic solvents, leading to rapid aggregation and precipitation in biological systems [5]. Two primary strategies have been employed to enhance water solubility: (1) encapsulating hydrophobic ICSs within nanocarriers featuring hydrophilic surfaces, and (2) chemically modifying ICSs with hydrophilic groups or long chains to confer water solubility [5]. The surface charge, size, and chemical composition of these nanocarriers significantly influence their therapeutic efficacy, with optimal sizes typically ranging from 10-200 nm to leverage the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect in tumor tissues [5].

Biosafety and Toxicity Concerns

The self-assembly of ICSs often involves heavy metal ions, raising concerns about potential toxicity and side effects during treatment [5]. Enhancing circulation stability and minimizing adverse effects are crucial for clinical translation [5]. Strategies to improve biosafety include developing stimuli-responsive systems that release therapeutic payloads specifically at target sites, functionalizing ICS surfaces with targeting moieties to enhance cellular selectivity, and exploring less toxic metal ions in coordination frameworks [5]. Research on silver and gold N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) pillarplexes has shown promising antimicrobial and anticancer properties with differential bioactivity between the metal variants [4].

Structural Complexity and Functionalization

The construction of increasingly complex ICSs with precise functionality remains a synthetic challenge. Future research directions include the development of more sophisticated functionalization strategies, incorporation of stimuli-responsive elements for controlled guest release, and creation of hierarchical structures with multiple compartments for complex chemical transformations [9] [7]. The integration of ICSs with other materials, such as polymers, nanoparticles, and surfaces, will expand their application potential in targeted drug delivery, sensing, and catalysis [5].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for ICS Construction

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in ICS Construction |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Acceptors | Pd(II), Pt(II), Cu(I), Fe(II), Ag(I) complexes | Provide structural nodes with specific coordination geometries |

| Organic Donors | Pyridyl-based ligands, catecholates, N-heterocyclic carbenes | Serve as linkers with defined angles and directions |

| Functional Ligands | Diarylethene, BODIPY, tetraphenylethylene (TPE) | Impart photoresponsive, fluorescent, or AIE properties |

| Solvent Systems | Dichloromethane, acetone, THF/water mixtures | Mediate self-assembly process and influence morphology |

| Counterions | PF₆â», OTfâ» | Provide charge balance and influence solubility |

Diagram 2: Challenges and Strategies in ICS Development

Inorganic Cluster Supramolecular Compounds represent a rapidly advancing field with significant potential in biomedical applications. The precise control over structure and functionality afforded by coordination-driven self-assembly enables the design of sophisticated materials with tailored properties for drug delivery, cancer therapy, diagnostic imaging, and theranostics. While challenges related to water solubility, biocompatibility, and toxicity remain active areas of investigation, the unique characteristics of ICSs—including their structural precision, host-guest capabilities, and dynamic behavior—position them as promising candidates for next-generation pharmaceutical development. As research continues to address current limitations and explore new structural paradigms, ICSs are poised to make substantial contributions to advanced therapeutics and personalized medicine.

The field of supramolecular chemistry concerns chemical systems composed of discrete molecular components organized via non-covalent interactions, with metal-ligand coordination representing a particularly powerful subset due to its directionality and predictability [10]. Coordination-driven self-assembly has emerged as a foundational methodology for constructing sophisticated architectures from molecular building blocks, enabling the creation of both discrete supramolecular coordination complexes (SCCs) and extended metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) [11]. These metal-organic materials (MOMs) share the common design principle of metal nodes connected by organic ligands, yet diverge in their final structures and applications [11]. Understanding the fundamental bonding interactions and assembly pathways is crucial for advancing the rational design of inorganic cluster supramolecular compounds with tailored properties for applications ranging from catalysis to drug delivery [12].

This technical guide examines the core principles governing metal-ligand coordination and self-assembly pathways within the context of inorganic cluster supramolecular compound synthesis. We explore the historical foundations, quantitative bonding parameters, experimental methodologies, and characterization techniques essential for researchers engaged in the design and implementation of these complex systems.

Fundamental Principles of Metal-Ligand Coordination

Historical Development and Key Concepts

The theoretical foundation for modern coordination chemistry was established by Alfred Werner in 1893 with his description of octahedral transition metal complexes, which explained how metal ions form bonds beyond what was necessary for charge neutrality [11]. This work originated the understanding that metal ions possess preferred coordination geometries that enable rational synthetic methodologies for installing specific ligands [11].

Supramolecular coordination chemistry gained significant momentum with pioneering work on molecular recognition in the 1960s by Pedersen, who discovered crown ethers capable of selectively chelating metal ions [11] [10]. This was followed by Lehn's development of cryptands and Cram's work on selective host-guest complexes, for which they shared the 1987 Nobel Prize in Chemistry [10]. These early investigations established that non-covalent interactions – including hydrogen bonding, metal coordination, hydrophobic forces, van der Waals forces, π-π interactions, and electrostatic effects – govern the spatial organization of molecular components into larger architectures [10].

The directional nature of metal-ligand coordination bonds provides a significant advantage over other non-covalent interactions for constructing well-defined architectures. The kinetic lability of these bonds enables self-correction during assembly, while the geometric preferences of metal ions (e.g., linear, square planar, tetrahedral, octahedral) allow for predictable structural outcomes when combined with appropriately designed organic ligands [11] [13].

Key Coordination Geometries and Their Structural Outcomes

Table 1: Common Metal Coordination Geometries in Supramolecular Assembly

| Metal Coordination Geometry | Typical Metal Ions | Ligand Arrangement | Resulting Architecture |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear | Pt(II), Pd(II), Au(I) | 180° between ligands | Linear chains, macrocycles |

| Square Planar | Pt(II), Pd(II), Ni(II) | 90° between ligands | Squares, grids, 2D layers |

| Tetrahedral | Cu(I), Zn(II), Cd(II) | 109.5° between ligands | Tetrahedra, diamondoid networks |

| Octahedral | Fe(II), Ru(II), Co(III) | 90° between ligands | Trigonal prisms, cubes, 3D networks |

The selection of metal ion and organic ligand directly determines the structural outcome of the self-assembly process. Early work by Fujita and Stang in the 1990s demonstrated the rational design of supramolecular squares using Pd and Pt ions with linear bridging ligands [11]. This foundational approach has since been extended to create increasingly complex architectures, including polygons, polyhedra, prisms, and extended frameworks [11].

Self-Assembly Pathways in Supramolecular Systems

Thermodynamic versus Kinetic Control

Self-assembly processes in supramolecular systems can proceed under thermodynamic or kinetic control, significantly impacting the reaction pathway and final product [13]. Thermodynamically controlled assemblies utilize reversible metal-ligand bonds that allow the system to explore multiple configurations before settling into the global energy minimum, which typically represents the most stable structure [13]. In contrast, kinetically controlled assemblies may form metastable intermediates that persist due to high activation energies for rearrangement.

The dynamic nature of metal-ligand coordination is essential for self-correction during assembly. Labile metal-ligand interactions enable initially formed, random oligomeric structures to rearrange into the thermodynamically favored product [13]. This spontaneous error-checking mechanism represents a significant advantage for constructing complex architectures with high fidelity.

Studies of helicate formation demonstrate that self-assembly often proceeds through a stepwise mechanism involving several kinetic intermediates [13]. These intermediates may possess altered coordination geometries or include coordinated solvent molecules that are eventually displaced during the structural self-correction process. In some systems, the addition of external agents such as guest molecules can trigger supramolecular transformations from one structure to another over extended time periods, providing insight into assembly mechanisms [13].

Cooperativity in Assembly Processes

Cooperativity represents a fundamental principle in supramolecular assembly where the integration of constituent components creates emergent properties not present in the individual building blocks [13]. This phenomenon significantly impacts the stability and dynamic behavior of the resulting architectures.

Research on tris-catecholato complexes demonstrates this principle clearly. While mononuclear tris-catecholato complexes racemize rapidly via a trigonal twist mechanism, linking two such complexes in a helicate slows racemization by a factor of 100 due to mechanical coupling between metal centers [13]. This cooperative effect becomes even more pronounced in tetrahedral M₄L₆ structures, where racemization is not observed despite evidence of dynamic ligand and guest exchange [13]. Similar studies on Co²⺠benzimidazole complexes found the racemization rate of dinuclear helicates to be six orders of magnitude slower than their mononuclear analogs [13].

Table 2: Quantitative Studies of Cooperativity in Supramolecular Assemblies

| Assembly Type | Structural Feature | Dynamic Process | Rate Change vs. Monomer |

|---|---|---|---|

| M₂L₃ helicate | Two linked tris-catecholate complexes | Racemization | 100× slower |

| M₄L₆ tetrahedron | Four linked tris-catecholate complexes | Racemization | Not observed |

| Coâ‚‚L₃ helicate | Dinuclear benzimidazole complex | Racemization (dissociative mechanism) | 10â¶Ã— slower |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Design and Synthesis of Building Blocks

The construction of supramolecular architectures requires careful design of molecular building blocks with specific geometric and electronic properties. Linear metal-organic ligands with specific sequences can be designed to facilitate the self-assembly of metallo-supramolecules with increasing complexity [14]. These building blocks typically consist of organic ligands with multiple binding sites oriented with specific angularity and metal ions with well-defined coordination preferences [11].

Recent advances have demonstrated the synthesis of linear building blocks through coordination between terpyridine ligands and Ru(II), creating metal-organic ligands with high stability [14]. Subsequent self-assembly with weaker coordinating but highly reversible metal ions such as Zn(II), Fe(II), and Cd(II) enables the formation of discrete 2D fractal architectures ranging from simpler structures (C1, 3,360 Da) to highly complex systems (C5, 38,066 Da) with precisely controlled shapes and sizes [14].

Three primary synthetic approaches for preparing terpyridine-Ru(II) metal-organic ligands have been developed:

- End-capping approach based on coordination with Ru(III) complexes followed by reduction

- Suzuki coupling reaction on terpyridine-Ru(II) complexes

- Sonogashira coupling reaction on terpyridine-Ru(II) complexes with TMS protection and deprotection steps [14]

The Sonogashira approach particularly enables the synthesis of longer asymmetric metal-organic building blocks with rigid linkages, reminiscent of protection and deprotection strategies in peptide synthesis [14].

Characterization Techniques for Supramolecular Assemblies

Rigorous characterization of supramolecular assemblies presents significant challenges due to their large size, complex connectivity, and dynamic behavior [13]. Multiple complementary techniques are typically required to unambiguously determine structure and assembly properties.

Mass spectrometry techniques, particularly electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) and traveling wave ion mobility-mass spectrometry (TWIM-MS), provide essential information about molecular weight, composition, and isomeric purity [14]. ESI-MS can reveal continuous charge states with well-resolved isotope patterns consistent with theoretical distributions, while TWIM-MS with narrow drift time distribution confirms the absence of isomeric structures [14].

Multi-dimensional NMR spectroscopy, including ¹H, COSY, and NOESY experiments, offers insights into molecular symmetry and structural features [14]. For instance, in zinc-coordinated terpyridine assemblies, characteristic downfield shifts of 3',5' protons and upfield shifts of 6,6" protons confirm successful metal coordination [14]. Similarly, ¹â¹F NMR can reveal symmetry information through discrete chemical environments [14].

Table 3: Characterization Techniques for Supramolecular Assemblies

| Technique | Information Obtained | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|

| ESI-MS | Molecular weight, composition | Continuous charge states, isotope patterns |

| TWIM-MS | Structural isomers, shape | Drift time distribution |

| ¹H NMR | Molecular symmetry, ligand environment | Characteristic proton shifts |

| ¹â¹F NMR | Symmetry, chemical environments | Discrete sets of peaks |

| 2D COSY/NOESY | Spatial relationships, connectivity | Through-bond and through-space correlations |

Visualization of Assembly Pathways and Workflows

Coordination-Driven Self-Assembly Process

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental pathway for coordination-driven self-assembly of supramolecular architectures:

Characterization Workflow for Supramolecular Assemblies

The comprehensive characterization of supramolecular assemblies requires a multi-technique approach as depicted below:

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents in Supramolecular Coordination Chemistry

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Assembly | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Salts | Cd(NO₃)₂, Zn(II) salts, Fe(II) salts, Pt(II) complexes, Pd(II) complexes | Geometric nodes with specific coordination preferences | Variable coordination geometry, lability, oxidation state |

| Nitrogen-based Ligands | 4,4'-bipyridine, terpyridine, phenanthroline | Linear or angular spacers between metal nodes | Rigidity, binding affinity, angularity |

| Carboxylate-based Ligands | Terephthalate, trimesic acid, 1,3,5-benzenetricarboxylic acid | Bridging ligands for extended frameworks | Multiple binding modes, charge balance |

| Macrocyclic Hosts | Cucurbiturils, cyclodextrins, calixarenes | Molecular recognition elements | Preorganized cavities, host-guest chemistry |

| Template Molecules | Chloride ions, organic cations, neutral aromatics | Structure-directing agents | Complementary size/shape to assembly cavity |

| Solvent Systems | CHCl₃/MeOH mixtures, aqueous ethanol, DMF | Medium for self-assembly process | Polarity, coordinating ability, solubility |

The rational design of supramolecular architectures through metal-ligand coordination and self-assembly pathways represents a sophisticated synthetic methodology at the interface of inorganic and supramolecular chemistry. Fundamental understanding of coordination geometries, thermodynamic versus kinetic control, cooperativity effects, and characterization techniques enables researchers to construct complex functional systems with precision. The continued development of this field promises advanced materials for biomedical applications, catalysis, sensing, and molecular electronics, driven by increasingly sophisticated design principles and experimental methodologies. As the field progresses, integration of biological inspiration with synthetic expertise will likely yield ever more complex and functional supramolecular systems.

The rational design of inorganic cluster supramolecular compounds hinges on the precise selection and combination of two fundamental components: transition metal nodes and multidentate organic linkers. These building blocks dictate the structural topology, stability, and functional properties of the resulting frameworks, which find applications in catalysis, drug delivery, bioimaging, and theranostics. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of these core components, detailing their classifications, properties, and the experimental methodologies that enable the synthesis of advanced supramolecular architectures. Framed within current research on inorganic cluster supramolecular chemistry, this whitepaper serves as a foundational resource for researchers and drug development professionals engaged in the design of functional coordination complexes.

Inorganic cluster supramolecular compounds are a class of materials constructed from metal-based nodes connected by organic linkers via coordination bonds. The field represents a convergence of coordination chemistry and supramolecular science, focusing on the design of discrete or extended architectures with defined geometries and properties. [6] The robustness and modular nature of these structures allow for the incorporation of diverse functionalities, making them ideal scaffolds for developing multimodal theranostic agents and novel drug delivery systems. [6] The design principles are largely governed by the "node-and-linker" approach, where the coordination geometry of the metal cluster (node) and the binding topology of the organic ligand (linker) determine the overall structure and, consequently, the material's functional characteristics. [15] [16]

Transition metal clusters, particularly octahedral clusters of molybdenum or rhenium, offer unique photophysical and redox properties, while multidentate organic linkers provide the structural directionality and chemical functionality. [17] [18] The synergy between these components enables the creation of materials with tailored properties for specific applications, from photodynamic therapy to catalysis. [17] [19] This guide systematically outlines the key building blocks, their classifications, and the experimental protocols for their assembly, providing a comprehensive resource for synthesis research in this rapidly evolving field.

Transition Metal Nodes: Structural and Functional Cores

Transition metal nodes, often referred to as Secondary Building Units (SBUs), are inorganic clusters that serve as the structural vertices of supramolecular frameworks. These nodes can range from single metal ions to polynuclear metal clusters, with their specific coordination geometry dictating the overall topology of the resulting network. [15]

Classification and Properties of Metal Nodes

Table 1: Key Classes of Transition Metal Cluster Nodes and Their Characteristics

| Cluster Type | Composition | Key Structural Features | Photophysical Properties | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Octahedral Halide Clusters | [M6L14]n- (M = Mo, W; L = halogen) [17] | Nanometer-sized metallic Mo(II) aggregates; 8 inner ligands, 6 labile apical ligands [17] | Red/NIR phosphorescence; high singlet oxygen quantum yields (e.g., [Mo6I8(CF3COO)6]2- ISC: 1.7 ps) [17] | Photodynamic/Radiodynamic Therapy [17] |

| Octahedral Cyano Clusters | [M6L14]n- (M = Mo, Re; L = chalcogen) [18] | [M6L14]n- units, 1< n <8 [18] | Highly emissive in red-NIR (PLQY up to 0.23) [18] | Luminescent dyes in Liquid Crystals [18] |

| Zirconium-based SBUs | e.g., Zr6O4(OH)4 (in UiO-66) [19] | 6 Zr atoms in an octahedron; high connectivity | High chemical and thermal stability | Catalysis, Drug Delivery [19] |

| Paddle-wheel SBUs | e.g., Cu2(RCOO)4 | Dinuclear cluster with four bridging linkers | Open metal sites after activation | Gas storage, Separation |

A prominent class of nodes is the octahedral molybdenum cluster. For instance, the [Mo6I8]n+ core consists of six molybdenum atoms forming an octahedron, stabilized by eight strongly bonded inner iodide ligands and six labile apical ligands that can be functionalized. [17] These clusters display attractive photophysical properties, including excitation by UV-blue light, ultrafast intersystem crossing (e.g., 1.7 ps for [Mo6I8(CF3COO)6]2-), and long-lived triplet states (hundreds of µs) in solids. [17] Their phosphorescence in the red/near-IR region, with large Stokes shifts and high quantum yields, makes them excellent photosensitizers for producing singlet oxygen (O2(1Δg)), a key mediator in photodynamic therapy (PDT) and antimicrobial photoinactivation. [17]

The electronic properties of these metal clusters, such as the energy of their triplet states (approximately 1.9 eV for Mo6 clusters), must be higher than the energy required to excite molecular oxygen to its singlet state (0.98 eV) for efficient energy transfer and singlet oxygen production. [17] Their inorganic nature also makes them less prone to photobleaching compared to organic dyes like porphyrins, and they do not experience self-quenching of excited states at high concentrations, enhancing their utility in solid-state applications or as concentrated agents. [17]

Multidentate Organic Linkers: Architectural Spacers

Organic linkers are multidentate bridging ligands that connect metal nodes, defining the framework's geometry, pore size, and chemical environment. The flexibility, length, and functional groups of the linker directly influence the structural and chemical properties of the final supramolecular compound. [20]

Linker Classification and Functionalization

Table 2: Classification of Multidentate Organic Linkers for Supramolecular Compounds

| Linker Class | Functional Group | Coordination Mode & Characteristics | Impact on Framework Properties | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carboxylate Linkers | -COOâ» | Chelates/bridges metal ions; strong coordination; H-bond donor/acceptor [20] | High surface area, uniform pores, high crystallinity [20] | Gas adsorption, Catalysis, Metal removal [20] |

| Nitrogen-based Linkers | Heterocyclic N (e.g., pyridyl, imidazole) | Directional coordination; tunable electronic properties [20] | Tunable pore chemistry, structural diversity [20] | Molecular sieving, Catalysis, Pollutant capture [20] |

| Phosphorous-based Linkers | -PO3H / -PO3â» | Forms strong P-O-M bonds [20] | High chemical/thermal stability; polar porosity [20] | Proton conduction, Luminescent sensing [20] |

| Sulfonic Acid Linkers | -SO3H | Strong Brønsted acid site; polar, electron-rich [20] | Hydrophilicity; acidic catalysis in pores [20] | Acid-catalyzed reactions [20] |

| Flexible Multidentate Linkers | Mixed N/O donors (e.g., pyrazole-carboxylate) | Adaptable conformation; variable binding modes [21] | Structural dynamism; formation of low-dimension structures (e.g., 1D chains) [21] | Luminescent materials [21] |

Carboxylate-based linkers are among the most extensively used due to their strong coordination to metal ions and ability to form rigid, highly porous frameworks. [20] For example, 1,4-benzenedicarboxylic acid (terephthalic acid, H2bdc) is a fundamental linker in iconic MOFs like MOF-5. [15] The rigidity of the aromatic backbone in such linkers is key to achieving permanent porosity.

Nitrogen-based linkers, particularly heterocyclic types like pyridyl, imidazole, and their derivatives, offer different coordination geometries and electronic characteristics compared to carboxylates. [20] They are classified into heterocyclic azine N-based linkers (e.g., pyrazine, bipyridyl), heterocyclic-azole N-based linkers (e.g., imidazole, triazole), noncyclic N-based linkers, and ionic N-based linkers. [20] The choice of nitrogen linker significantly influences the framework's stability, pore environment, and application suitability. [20]

The functionalization of linker backbones allows for the fine-tuning of host-guest chemistry within the framework's pores. For instance, sulfonic acid groups can introduce strong Brønsted acidity for catalysis, while hydroxy groups can enhance CO2 capture and facilitate proton conduction. [20] Fluorinated linkers impart hydrophobicity and stability, and their highly polar C-F bonds can improve interactions with gases like CO2. [20]

Experimental Protocols for Synthesis and Characterization

The synthesis of supramolecular compounds based on transition metal clusters and organic linkers requires careful control of reaction conditions to achieve the desired crystalline products.

Synthetic Methodologies

Solvothermal Synthesis: This is the most common method for growing high-quality single crystals suitable for structure determination by X-ray crystallography. [15] It typically involves dissolving the metal salt and organic linker in a suitable solvent (e.g., N,N-diethylformamide, water, acetonitrile) in a sealed vessel and heating the mixture to temperatures above the solvent's boiling point for several hours to days. [15] The elevated temperature and pressure enhance the solubility and reactivity of the precursors, facilitating slow and controlled crystal growth. For example, the synthesis of complex [Cu(L1)(2,2–bipy)]2n·3nH2O (1) was achieved by reacting the flexible ligand 1,1´-methylenebis(5-methyl-pyrazole-4-carboxylic acid) (H2L1) and coligand 2,2'-bipyridyl with Cu(OAc)2·H2O under specific, though undisclosed, reaction conditions. [21]

Microwave-Assisted Synthesis: This technique uses microwave irradiation to rapidly nucleate MOF crystals, reducing synthesis times from days to minutes or seconds. [15] It often yields smaller, more uniform crystals (micron-scale) compared to conventional solvothermal methods and is useful for high-throughput screening. [15]

Mechanochemical Synthesis: A solvent-free approach that involves grinding metal precursors and organic linkers using a ball mill. [15] This method is scalable and environmentally friendly, producing materials like Cu3(BTC)2 in quantitative yield. The morphology of the solvent-free synthesized product can be identical to the industrially produced material (e.g., Basolite C300). [15] The addition of small amounts of ethanol can reduce structural defects. [15]

Electrophoretic Deposition (EPD) for Film Formation: For applications requiring thin films, such as coatings for medical devices, EPD can be employed. Kirakci et al. demonstrated the electrophoretic deposition of layers of octahedral molybdenum cluster complexes onto surfaces, creating coatings effective for mitigating pathogenic bacterial biofilms under blue light. [17]

Post-Synthetic Functionalization and Nanocarrier Encapsulation

To enhance the stability, dispersibility, and biodistribution of cluster complexes for biological applications, post-synthetic modifications are often employed:

- PEGylation: Attaching poly(ethylene glycol) chains to cluster complexes improves their hydrophilicity and biocompatibility. For instance, a PEGylated molybdenum-iodine nanocluster showed promise as a radiodynamic agent against prostatic adenocarcinoma. [17]

- Polymer Nanocarriers: Encapsulating clusters in biocompatible polymers like poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) or copolymers based on N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide (HPMA) protects them from hydrolysis and improves their pharmacokinetic profile while preserving their photophysical properties. [17]

- Surface Decoration with Targeting Ligands: Apical ligands can be designed to include functional groups that target specific cellular components. Kirakci et al. developed a cell membrane-targeting molybdenum-iodine nanocluster through rational ligand design, which enhanced its photodynamic activity. [17]

Key Characterization Techniques

- Single-Crystal X-ray Diffraction (SCXRD): The definitive technique for determining the precise three-dimensional atomic structure, topology, and porosity of crystalline supramolecular compounds. [15]

- Photophysical Characterization:

- Luminescence Quantum Yield: Measures the efficiency of photon emission.

- Lifetime Measurements: Determines the duration of excited states (e.g., triplet state lifetime).

- Singlet Oxygen Quantum Yield: A critical parameter for photosensitizers, measured using chemical traps or direct detection of the O2(1Δg) phosphorescence at 1270 nm. [17]

- Thermal Analysis (TGA): Assesses the thermal stability of the framework and the removal of solvent molecules from the pores.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Supramolecular Compound Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Salts | Source of metal ions/clusters | Cu(OAc)2·H2O [21], ZrCl4, MoCl2 |

| Carboxylate Linkers | Primary bridging ligands for framework construction | 1,4-benzenedicarboxylic acid (H2BDC) [15], 1,3,5-benzenetricarboxylic acid (H3BTC) |

| Nitrogen-based Linkers | Provide directional coordination and tunable functionality | 2,2'-bipyridyl (2,2-bipy) [21], 4,4'-bipyridine, imidazole derivatives |

| Solvents | Medium for solvothermal synthesis; influences crystal growth | N,N-Diethylformamide (DEF), Water, Acetonitrile [15] |

| Modulators | Competitive coordinating agents to control crystal growth | Acetic acid, Trifluoroacetic acid |

| Functionalization Reagents | Post-synthetic modification of clusters or linkers | PEG derivatives [17], Chitosan [17], Targeting peptides |

| Nanocarriers | Improve biocompatibility and biodistribution for biological apps | PLGA [17], HPMA copolymer [17] |

| Stannane, butyltriiodo- | Stannane, butyltriiodo-, CAS:21941-99-1, MF:C4H9I3Sn, MW:556.54 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Urea, (p-hydroxyphenethyl)- | Urea, (p-hydroxyphenethyl)- | Urea, (p-hydroxyphenethyl)- is a chemical for research (RUO). It is not for human, veterinary, or household use. Explore its value as a urease inhibitor and antimicrobial agent. |

Workflow and Property Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the choice of building blocks, the synthesis process, the resulting structural properties, and the eventual applications of the supramolecular compounds.

In the field of inorganic cluster supramolecular compound synthesis, architectural control is a fundamental objective, determining the physical properties and ultimate application of the materials formed. This control is exercised primarily through two interdependent elements: the coordination geometry of the metal nodes and the molecular design of the organic linkers. The metal nodes, with their specific coordination preferences dictated by electronic structure and the nature of the coordinating atoms, act as the vertices of the final structure. The organic linkers, through their length, functionality, and directional bonding character, define the edges and dictate the spatial arrangement of these vertices. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to the principles and methodologies for achieving precise architectural control in the synthesis of supramolecular assemblies, with a specific focus on systems involving inorganic clusters.

Fundamentals of Coordination Geometry

The geometry around a metal center is a primary determinant of the final network topology in supramolecular assemblies. The coordination geometry is influenced by the metal ion's character, oxidation state, and the chemical nature of the ligands provided by the organic linkers.

Table 1: Common Metal Center Coordination Geometries and Their Structural Influence

| Metal Ion Example | Coordination Number | Geometry | Ideal Bond Angle | Representative Cluster Topology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu(I), Ag(I) [22] | 2 | Linear | 180° | Chains, 1D networks |

| Cu(II), Pt(II) [22] | 4 | Square Planar | 90° | 2D grid layers |

| Zn(II), Cd(II) | 4 | Tetrahedral | 109.5° | Diamondoid, 3D networks |

| Cu(II) | 4 + 2 | Jahn-Teller Distorted Octahedral | Axial: ~180°; Equatorial: ~90° | Paddlewheel units in MOFs |

| Zr(IV) | 6, 8, 12 | Octahedral, Square Antiprismatic | Varies | High-connectivity, stable frameworks |

The use of organometallic complexes as primary linkers, rather than simple organic molecules, represents an advanced strategy for architectural control. For instance, metalated quinonoid complexes, such as [Cp*M(ηâ´-benzoquinone)] (where Cp* = Câ‚…Meâ‚…, M = Rh, Ir), can act as supramolecular building blocks [22]. These units possess their own intrinsic coordination preferences from the Cp*M moiety and can further coordinate through their oxygen or sulfur atoms to secondary metal ions (e.g., Cu(I), Ag(I), Pt(II)) [22]. This creates a hierarchical assembly process where the coordination geometry at both the organometallic core and the secondary metal node directs the formation of complex supramolecular architectures.

Linker Design Strategies

The organic linker is the architectural blueprint in supramolecular assembly. Its design directly controls the network's metrics, topology, and chemical functionality.

Core Structure and Metrics

- Length and Rigidity: The length of the linker dictates the pore size and volume in the resulting framework. Short, rigid linkers (e.g., benzenedicarboxylate) produce dense structures with small pores, while elongated, rigid linkers (e.g., biphenyldicarboxylate, terphenyldicarboxylate) generate more open frameworks with large pores and low density [23].

- Geometry and Symmetry: The angular relationship between the coordinating groups on the linker is critical. Linear ditopic linkers tend to form simpler structures, while non-linear, trigonal, or tetrahedral linkers promote the formation of complex, often interpenetrated, 3D networks.

Functionalization for Enhanced Control

- Pre-Synthetic Functionalization: Introducing functional groups (-NH₂, -OH, -CH₃, halogens) to the linker backbone prior to synthesis can be used to fine-tune the electronic properties of the framework, introduce hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity, and create specific binding sites for guest molecules. Schiff base ligands, formed by condensing amines with carbonyls, are a versatile class of linkers that offer a high degree of functionalization and can adopt specific tautomeric forms (enol or keto) that influence the supramolecular assembly [24].

- Supramolecular Interactions: Beyond coordinate covalent bonds, linker design can harness weaker supramolecular interactions to stabilize the overall structure. Hydrogen bonding, π-π stacking, and van der Waals forces can guide the assembly process and impart stimuli-responsive behavior [22] [24]. For example, benzene-1,3,5-tricarboxamide (BTA) derivatives interact via a directional 3-fold hydrogen bond array, which can be used to drive the assembly of colloidal particles [25].

Experimental Protocols for Synthesis and Characterization

Achieving architectural control requires precise and reproducible synthetic and analytical methodologies.

Synthesis of Supramolecular Coordination Networks

The following protocol, adapted from procedures for synthesizing networks with organometallic linkers and supramolecular colloids, outlines a general solvothermal approach [22] [25].

Objective: To synthesize a supramolecular coordination network using an organometallic quinonoid linker and a secondary metal ion.

Materials:

- Organometallic linker (e.g.,

[Cp*Ir(ηâ´-benzoquinone)]) - Secondary metal salt (e.g., Cu(I) or Ag(I) triflate)

- Anhydrous, degassed solvent (e.g., dichloromethane, acetonitrile)

- Inert atmosphere glove box or Schlenk line

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: In an inert atmosphere, prepare separate solutions of the organometallic linker (0.05 mmol in 5 mL solvent) and the secondary metal salt (0.05 mmol in 5 mL solvent).

- Layering and Diffusion: Carefully layer the metal salt solution over the linker solution in a thin tube. Seal the tube.

- Slow Diffusion: Allow the solutions to diffuse slowly at room temperature or a controlled temperature (e.g., 4°C) for several days to weeks.

- Crystal Harvesting: After crystal formation, decant the mother liquor and wash the crystals with a small amount of fresh, cold solvent. Dry the crystals under a stream of inert gas or under vacuum.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages of this synthesis and the subsequent characterization process.

Characterization Techniques for Architectural Verification

Rigorous characterization is essential to confirm that the synthesized structure matches the designed architecture.

- Single-Crystal X-ray Diffraction (SCXRD): The definitive technique for determining molecular and supramolecular structure. It provides precise atomic coordinates, allowing for the determination of coordination geometry, linker conformation, and overall network topology [24].

- Spectroscopic Analysis:

- FTIR Spectroscopy: Used to confirm the presence of specific functional groups (e.g., C=O, N-H) and the occurrence of coordination through shifts in characteristic absorption bands [24].

- NMR Spectroscopy: Particularly useful for characterizing the organic linkers and monitoring the formation of Schiff bases or other covalent bonds prior to network assembly. Solid-state NMR can probe the local environment within the framework [24].

- Hirshfeld Surface Analysis: A computational technique based on SCXRD data used to quantify and visualize intermolecular interactions (e.g., H-bonding, π-π contacts, C-H...π interactions) within the crystal packing, providing deep insight into the supramolecular assembly [24].

- Elemental Analysis (CHN): Corroborates the bulk composition of the synthesized compound, ensuring it aligns with the expected formula derived from the reaction stoichiometry [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Supramolecular Compound Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function & Role in Architectural Control |

|---|---|

| Metal Salts (e.g., Cu(CF₃SO₃)₂, AgNO₃, Zn(NO₃)₂) | Source of metal ions that act as structural nodes; the choice of metal and counter-ion influences coordination geometry and network solubility [22]. |

Organometallic Linkers (e.g., [Cp*M(ηâ´-benzoquinone)] M=Rh, Ir) |

Function as pre-designed, stable spacers with defined coordination vectors, generating novel architectures not accessible with purely organic linkers [22]. |

| Functionalized Organic Linkers (e.g., Schiff bases, BTA derivatives) | Provide structural metrics (length, angle) and introduce specific intermolecular interaction sites (H-bonding) to guide and stabilize assembly [25] [24]. |

| Anhydrous, Degassed Solvents (e.g., CHâ‚‚Clâ‚‚, MeCN, DMF) | Reaction medium; purity is critical for preventing hydrolysis or oxidation of sensitive metal precursors and linkers, ensuring reproducible crystal growth [22] [25]. |

| Silica-based Colloids | Functionalizable substrates for creating supramolecular colloids; their surface can be grafted with moieties like BTA to study and control particle-level assembly [25]. |

| Photo-labile Protecting Groups (e.g., o-nitrobenzyl (NVOC)) | Used to block specific interactions (e.g., H-bonding) on linkers or colloids. Controlled deprotection with UV light triggers on-demand assembly, providing temporal control [25]. |

| 3-Methyl-5-phenylbiuret | 3-Methyl-5-phenylbiuret|High-Purity Research Chemical |

| 1,2,4-Triazine, 5-phenyl- | 1,2,4-Triazine, 5-phenyl-, CAS:18162-28-2, MF:C9H7N3, MW:157.17 g/mol |

Precise architectural control in inorganic cluster supramolecular compounds is not a singular achievement but the result of a holistic design strategy. It requires the synergistic integration of metal node engineering—exploiting specific coordination geometries—and sophisticated linker design—controlling metrics, functionality, and supramolecular recognition. The experimental protocols, centered on controlled synthesis and multi-technique characterization, are essential for verifying architectural outcomes and understanding assembly mechanisms. As the field progresses, the incorporation of stimuli-responsive and mechanically interlocked components will further enhance our ability to create dynamic, functional supramolecular materials with bespoke architectures for advanced applications in catalysis, drug delivery, and sensing.

Metallacages represent a prominent class of three-dimensional supramolecular architectures formed via coordination-driven self-assembly of metal acceptors and organic ligands. [26] [27] These structures have emerged as powerful hosts in supramolecular chemistry due to their well-defined cavities, tunable sizes and shapes, and unique electronic properties. The integration of metal centers and organic components creates hybrid materials that combine advantages of both inorganic and organic systems, including structural robustness, rich photophysical properties, and synthetic versatility. [28] [29] The development of metallacage-based host-guest systems represents a growing frontier in inorganic cluster supramolecular chemistry, with particular relevance to applications in molecular recognition, drug delivery, and catalysis. [29] [27]

Host-guest chemistry within metallacage cavities is governed by multiple complementary interactions, including π-π stacking, hydrophobic effects, hydrogen bonding, and van der Waals forces. [28] [30] The confined nanospaces within these structures mimic enzyme binding pockets, enabling selective encapsulation of guest molecules through complementary size, shape, and functionality. [29] This review comprehensively examines the fundamental principles, quantitative binding relationships, experimental methodologies, and emerging applications of host-guest systems based on metallacage cavities, with particular emphasis on recent advances in the field.

Fundamental Principles and Design Strategies

Structural Design and Self-Assembly Principles

The construction of metallacages relies on directional bonding approaches where metal centers with specific coordination geometries connect organic ligands to form discrete, three-dimensional structures. [29] The most common design strategy utilizes cis-protected square planar metal complexes (particularly Pt(II) and Pd(II)) which provide 90° turns that promote cage closure. [29] [27] These metal centers typically coordinate to pyridyl donors on the organic ligands, forming stable metal-ligand bonds that define the cage architecture.

The geometry of the resulting metallacage is determined by the combination of metal coordination geometry and ligand topology. For instance, tetratopic porphyrin-based ligands combined with Pt(II) corners can form box-like structures, while tritopic ligands may generate triangular or tetrahedral architectures. [28] [29] The symmetry interaction model provides a complementary framework for predicting assembly outcomes, particularly for systems involving higher-symmetry components. [29] This approach considers the point group symmetries of both the metal corners and organic ligands to determine the most stable assembly product.

A key advancement in metallacage design has been the development of multicomponent self-assembly strategies, where multiple different organic ligands are incorporated into a single structure. [28] This approach enables finer control over cavity size, shape, and functionality, allowing for customization of host-guest properties. For example, porphyrin-based metallacages can be constructed using tetrapyridyl porphyrin faces connected by tetracarboxylic pillars via platinum(II) coordination bonds, resulting in box-shaped structures with ideal dimensions for encapsulating planar aromatic guests. [28]

Molecular Recognition in Confined Cavities

The molecular recognition properties of metallacage cavities arise from their confined nanospaces and specific interior functionalities. The host-guest binding can be described by the equilibrium H + G ⇌ HG, where the association constant (K) quantifies the binding strength. [30] These interactions are typically fast-exchange processes on the NMR timescale, allowing for detailed thermodynamic and kinetic analysis. [26] [28]

Multiple factors contribute to guest encapsulation in metallacages:

- Size and Shape Complementarity: The guest must sterically fit within the cage cavity. For instance, metallacages with dimensions of approximately 14.9 × 12.0 × 8.3 ų are ideal for hosting planar polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. [28]

- Electronic Complementarity: π-π interactions between electron-rich cage interiors and aromatic guests significantly enhance binding affinity. [28]

- Solvent Effects: Hydrophobic effects drive the encapsulation of non-polar guests from aqueous solutions, while solvophobic effects operate in organic solvents. [26]

- Secondary Interactions: Hydrogen bonding, dipole-dipole interactions, and van der Waals forces provide additional stabilization. [31]

The confined environment of metallacage cavities can significantly alter guest properties, including enhanced stability, modified reactivity, and changed spectroscopic signatures. [30] This confinement effect mimics enzymatic binding pockets and enables applications in stabilization of reactive species and control of chemical reactions.

Quantitative Host-Guest Binding Data

Table 1: Experimentally Determined Association Constants for Metallacage-Guest Complexes

| Metallacage System | Guest Molecule | Association Constant (Kâ‚) | Experimental Conditions | Primary Interactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDI-based Metallacage 4 [26] | Pyrene (G1) | (2.63 ± 0.05) × 10³ Mâ»Â¹ | CD₃CN, NMR Titration | Ï€-Ï€ Stacking, Hydrophobic |

| PDI-based Metallacage 4 [26] | Coronene (G2) | (1.41 ± 0.07) × 10â´ Mâ»Â¹ | CD₃CN, NMR Titration | Ï€-Ï€ Stacking, Hydrophobic |

| Porphyrin-based Metallacage 4 [28] | Coronene (G6) | 2.37 × 10â· Mâ»Â¹ | CH₃CN/CHCl₃ (9:1) | Ï€-Ï€ Stacking, Charge Transfer |

| PDI-based Metallacage 4 [26] | Alizarin Red S (G3) | Significant upfield shifts in ¹H NMR | CD₃CN | Host-Guest Complexation |

| PDI-based Metallacage 4 [26] | Methyl Orange (G4) | Significant upfield shifts in ¹H NMR | CD₃CN | Host-Guest Complexation |

Table 2: Structural Parameters of Representative Metallacages and Their Cavities

| Metallacage | Dimensions | Cavity Volume | Metal-Ligand Bonds | Structural Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDI-based Metallacage 4 [26] | 1.65 × 1.41 × 0.98 nm³ | ~1.1 nm³ | Eight Pt(II)-coordination bonds | Two PDI faces, Two tetracarboxylic pillars, Dihedral angle: 41.9° |

| Porphyrin-based Metallacage 4 [28] | 14.9 × 12.0 × 8.3 ų | ~1.48 nm³ | Eight Pt atoms with N-Pt-O angles of 82.3-83.5° | Two porphyrin panels, Parallel orientation, Distance between panels: 8.1 Å |

| Porphyrin-based Box [28] | Not specified | Not specified | Pt(II)-pyridyl/ carboxylate | Two large windows for guest entry, Nanochannel formation in solid state |

The quantitative data presented in Tables 1 and 2 reveal several important trends in metallacage host-guest chemistry. First, binding affinity correlates strongly with guest size and planarity, with larger, more planar aromatic systems (e.g., coronene) exhibiting significantly higher association constants than smaller analogues (e.g., pyrene). [26] [28] Second, metallacages with porphyrin panels generally show higher binding affinities than those with PDI faces, likely due to enhanced π-π interactions with aromatic guests. Third, the structural parameters of the cage cavity directly determine the size range of guests that can be effectively encapsulated.

Experimental Methodologies

Synthesis and Characterization of Metallacages

The preparation of metallacages typically involves self-assembly under mild conditions to preserve the metal-coordination bonds. Recent advances have demonstrated the efficacy of photo-induced copolymerization for creating metallacage-crosslinked networks while maintaining cage integrity. [26]

Protocol 1: General Procedure for Metallacage Synthesis via Self-Assembly [26] [28]

- Ligand Preparation: Synthesize and purify organic ligands (e.g., tetrapyridyl PDI or porphyrin derivatives) following standard organic synthesis techniques.

- Metal Precursor Preparation: Prepare cis-protected metal complexes (e.g., cis-(PEt₃)₂Pt(OTf)₂) and characterize by ³¹P NMR spectroscopy.

- Self-Assembly Reaction: Combine organic ligands and metal precursors in appropriate stoichiometric ratios (typically 1:1 or 2:1 ligand:metal) in anhydrous, degassed solvents (e.g., acetonitrile, DMF).

- Reaction Conditions: Stir the reaction mixture at room temperature or elevated temperatures (40-80°C) for 4-48 hours under inert atmosphere.

- Purification: Precipitate the product by slow vapor diffusion of non-solvents (e.g., toluene, i-propyl ether) into the reaction solution.

- Characterization: Validate cage formation using multinuclear NMR (¹H, ³¹P), ESI-TOF mass spectrometry, and X-ray crystallography when possible.

Protocol 2: Photo-induced Copolymerization for Metallacage-Crosslinked Networks [26]

- Monomer Preparation: Dissolve acrylate-functionalized metallacages and butyl methacrylate monomers in appropriate solvent (e.g., DMF, acetonitrile).

- Photoinitiator Addition: Add photoinitiators (e.g., Irgacure 2959) at 0.1-1 mol% relative to total monomers.

- UV Irradiation: Expose the mixture to UV light (λ = 365 nm) for specified durations (typically 5-30 minutes).

- Network Formation: Monitor gelation and continue irradiation until free-standing films form.

- Post-processing: Wash networks extensively with solvent to remove unreacted components and characterize by swelling experiments, electron microscopy, and spectroscopic techniques.

Host-Guest Binding Studies

Protocol 3: Determination of Association Constants by NMR Titration [26] [30]

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a concentrated stock solution of the metallacage host in deuterated solvent (e.g., CD₃CN).

- Titration Series: Add incremental amounts of guest solution to constant concentration host solutions in NMR tubes.

- NMR Acquisition: Record ¹H NMR spectra after each addition at constant temperature.

- Data Analysis: Monitor chemical shift changes (Δδ) of host and/or guest protons. Fit the binding isotherm to appropriate models (1:1 or 1:2 binding) using non-linear regression analysis.

- Validation: Perform Job's plot analysis to confirm binding stoichiometry.

Protocol 4: Host-Guest Complexation for Planar Dyes [26]

- Guest Selection: Select appropriate planar dyes (e.g., alizarin red S, methyl orange, methylene blue, rhodamine B).

- Complexation: Add excess guest (2-10 equivalents) to metallacage solution in suitable solvent.

- NMR Monitoring: Record ¹H NMR spectra and observe upfield chemical shifts of guest protons due to shielding effects of the cage.

- Control Experiments: Monitor ³¹P NMR spectra to confirm cage stability during complexation.

- Association Constant Determination: For stable complexes, perform quantitative titration as in Protocol 3.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Metallacage Host-Guest Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| cis-(PEt₃)₂Pt(OTf)₂ [26] [28] | Metal acceptor for coordination-driven self-assembly | Square planar geometry, protected cis sites, moisture-sensitive | Pt(II) corners for box-shaped metallacages |

| Tetrapyridyl PDI Ligands [26] | Electron-deficient face for metallacage construction | Strong visible absorption, fluorescence, planar structure | Component of photoresponsive metallacages |

| Tetrapyridyl Porphyrin Ligands [28] | Photosensitizing face for metallacage assembly | Strong Soret band, singlet oxygen generation, redox activity | Component of porphyrin-based metallacages |

| Tetracarboxylic Pillar Ligands [26] [28] | Structural pillars connecting cage faces | Variable lengths, functionalizable with polymerizable groups | Control cavity size and functionality |

| Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons [26] [28] | Model guests for binding studies | Planar, varying sizes, strong π-π interactions | Pyrene, coronene, perylene derivatives |

| Planar Dyes [26] | Charged guests for complexation studies | Ionic, visible absorption, industrial relevance | Alizarin red S, methyl orange, methylene blue |

| Deuterated Solvents [26] [28] | Medium for NMR characterization | Isotopically pure, minimal water content | CD₃CN, CDCl₃, DMSO-d₆ |

| Diethenyl ethanedioate | Diethenyl Ethanedioate|C6H6O4|Research Chemical | Research-grade Diethenyl Ethanedioate (C6H6O4). This product is For Research Use Only (RUO) and is not intended for personal use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Cobalt--dysprosium (1/3) | Cobalt--dysprosium (1/3), CAS:12200-33-8, MF:CoDy3, MW:546.43 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Applications and Functional Systems

Metallacages functionalized through host-guest chemistry have enabled diverse applications, particularly in environmental remediation and stimuli-responsive systems. PDI-based metallacage-crosslinked networks demonstrate excellent capabilities for photocatalytic water decontamination, effectively eliminating organic pollutants and bacterial contaminants through singlet oxygen generation. [26] These materials can be reused multiple times without significant loss of activity, making them practical for environmental applications.

Porphyrin-based metallacages exhibit remarkable singlet oxygen generation capabilities, enabling the development of photooxidation-responsive host-guest systems. [28] These systems can oxidize encapsulated anthracene derivatives to their endoperoxides, triggering guest release. By selecting anthracene guests whose endoperoxides can revert upon heating, fully reversible encapsulation-release systems can be constructed for controlled delivery applications. [28]

The future development of metallacage-based host-guest systems will likely focus on increasing complexity and functionality, including low-symmetry cages with anisotropic cavities, environmentally responsive systems, and integration with other materials. [29] Computational approaches are increasingly valuable for predicting host-guest compatibility and guiding synthetic efforts. [29] As these systems mature, they hold significant promise for advanced applications in drug delivery, chemical sensing, and green chemistry.

Visualizing Metallacage Assembly and Host-Guest Chemistry

Diagram 1: Metallacage assembly and host-guest chemistry workflow. The process begins with self-assembly of metal acceptors and organic ligands to form 3D metallacages with defined cavities, followed by encapsulation of guest molecules, leading to functional applications.

Diagram 2: Molecular recognition principles in metallacage host-guest chemistry. Multiple complementary factors contribute to selective guest encapsulation within metallacage cavities.

Synthetic Strategies and Emerging Biomedical Applications

Precursor-based synthesis, particularly through calcination, represents a foundational methodology in the fabrication of advanced catalytic nanomaterials. This approach leverages molecular-level control to dictate the structural, morphological, and compositional properties of the final inorganic material, enabling precise tuning of catalytic performance. The process fundamentally involves the thermal transformation of molecular or supramolecular precursors—often inorganic complexes or organic-inorganic hybrids—into target metal oxide nanomaterials under controlled atmospheres [32] [33]. Within the broader context of inorganic cluster supramolecular compound research, this methodology bridges the gap between molecular chemistry and materials science, allowing the transfer of structural information from the precursor to the functional nanomaterial [34].

The calcination pathway offers distinct advantages for catalytic applications, including control over phase composition, surface area, particle size, and porosity—all critical parameters governing catalytic activity, selectivity, and stability. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of precursor-based synthesis routes, with a specific focus on calcination processes for developing advanced catalytic nanomaterials, drawing upon recent advances in supramolecular and nanomaterial chemistry.

Fundamental Principles of Precursor Transformation

The thermal decomposition of precursors during calcination follows complex solid-state reaction pathways influenced by multiple parameters. Understanding these fundamentals is essential for rational design of catalytic nanomaterials.

Precursor Selection and Design

Precursor compounds serve as molecular reservoirs that define the stoichiometry and spatial distribution of elements in the final material. The selection of precursor classes includes:

- Inorganic Salts: Metal nitrates, chlorides, and ammonium salts that decompose to metal oxides with release of gaseous byproducts [32].

- Metal-Organic Complexes: Carboxylates (oxalates, citrates, malonates) and other coordination compounds where organic ligands control metal coordination geometry [33].

- Supramolecular Assemblies: Organic-inorganic hybrid structures where molecular components guide the assembly of inorganic clusters through non-covalent interactions [34].

The decomposition pathway of any precursor is governed by the characteristics of the organic moiety, the gaseous atmosphere (inert, reducing, or oxidizing), and the thermal profile employed during calcination [33].

Calcination Thermodynamics and Kinetics

The transformation from precursor to metal oxide involves complex thermodynamic and kinetic processes:

- Decomposition Mechanisms: Sequential or concurrent loss of volatile components (Hâ‚‚O, COâ‚‚, NOâ‚“) through nucleation and growth processes.

- Phase Transformation: Thermal energy overcomes kinetic barriers to crystalline phase formation, with specific temperatures stabilizing polymorphic forms [32].

- Particle Growth and Sintering: Oswald ripening and coalescence processes that determine final particle size distribution and surface area.

For zirconia nanomaterials, for instance, calcination temperature directly controls crystalline phase: pure monoclinic phase is stable up to 1100°C, tetragonal phase forms between 1100–2370°C, and cubic phase exists above 2370°C [32]. Stabilization of typically high-temperature phases at room temperature can be achieved through precursor design and controlled calcination.

Table 1: Classification of Precursor Types for Nanomaterial Synthesis

| Precursor Category | Specific Examples | Decomposition Products | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Salts | ZrOCl₂·8H₂O, ZrCl₄, Co(NO₃)₂ | ZrO₂, Co₃O₄ | Low cost, simple processing |

| Carboxylate Complexes | Cobalt oxalate, citrate, malonate | Co₃O₄, CoO, metallic Co | Controlled stoichiometry, mixed metal capability |

| Alkoxides | Zr(C₅H₇O₂)₄ | ZrO₂ | High purity, low decomposition temperatures |

| Supramolecular Hybrids | {[L][HgI₄]}, {[L][CoCl₃]₂} | Metal oxides, chalcogenides | Molecular-level structure control |

Experimental Methodologies

Precursor Synthesis Protocols

Solution-Based Precursor Preparation

Oxalate Route for Cobalt-Based Nanomaterials:

- Dissolve cobalt acetate tetrahydrate (2.5 g) in ethanol (50 mL) at 35–40°C with continuous stirring.

- Add oxalic acid (1.5 g) dissolved in ethanol (20 mL) dropwise to form a thick gel.

- Age the gel for 12 hours, then dry at 80°C for 24 hours to obtain cobalt oxalate precursor [33].

Citrate-Based Sol-Gel Method:

- Prepare aqueous solutions of cobalt nitrate (1 M) and citric acid (1.5 M).

- Mix solutions in 1:1.2 molar ratio (metal:citrate) with continuous stirring.

- Evaporate at 80°C to form viscous gel, then dry at 120°C to obtain porous precursor [33].

Supramolecular Hybrid Synthesis

Organic-Inorganic Hybrid Template Synthesis:

- React 1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane (DABCO) with 1,2-bis(2-chloroethoxy)ethane to form organic cationic template L·Cl₂ [34].

- Dissolve template (0.5 mmol) in acetonitrile (10 mL).

- Add metal salt (0.5 mmol) and stir for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Allow slow solvent volatilization over 7-10 days to form single crystals suitable for structural characterization [34].

Calcination Parameters and Equipment

Calcination transforms precursors to active nanomaterials through controlled thermal treatment:

Standard Calcination Protocol:

- Load precursor powder into appropriate crucible (alumina, quartz, or platinum).

- Place in furnace with controlled atmosphere capability.

- Ramp temperature at 2–10°C/min to target temperature (typically 400–800°C).

- Hold at target temperature for 2–6 hours for complete decomposition and crystallization.

- Cool to room temperature at 1–5°C/min to preserve desired phase composition.

Atmosphere Control:

- Oxidizing Conditions: Static air or oxygen flow for metal oxide formation.

- Inert Conditions: Nitrogen or argon for reduced metal phases or preventing oxidation.

- Reducing Conditions: Hydrogen-containing atmospheres for metallic nanoparticles.

Table 2: Optimization of Calcination Parameters for Selected Nanomaterials

| Target Material | Precursor | Optimal Calcination Temperature | Atmosphere | Holding Time | Resulting Properties |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co₃O₄ nanoparticles | Cobalt oxalate dihydrate | 500°C | Static air | 2 hours | Spinel structure, 20-30 nm size [33] |

| ZrO₂ nanoparticles | Zirconium oxychloride | 400°C | Air | 2 hours | Mixed phase (monoclinic/tetragonal), 8-10 nm size [32] |

| CoO nanoparticles | Cobalt oxalate | 500°C | Air | 4 hours | Rock salt structure, anisotropic morphology [33] |

| CoFe₂O₄ spinel | Oxalate precursor | 600°C | Air | 5 hours | Ferrimagnetic, 15-25 nm size [33] |

Characterization of Calcined Nanomaterials