Strategies for Optimizing Charge Separation in Semiconductor Photocatalysts: From Mechanisms to Biomedical Applications

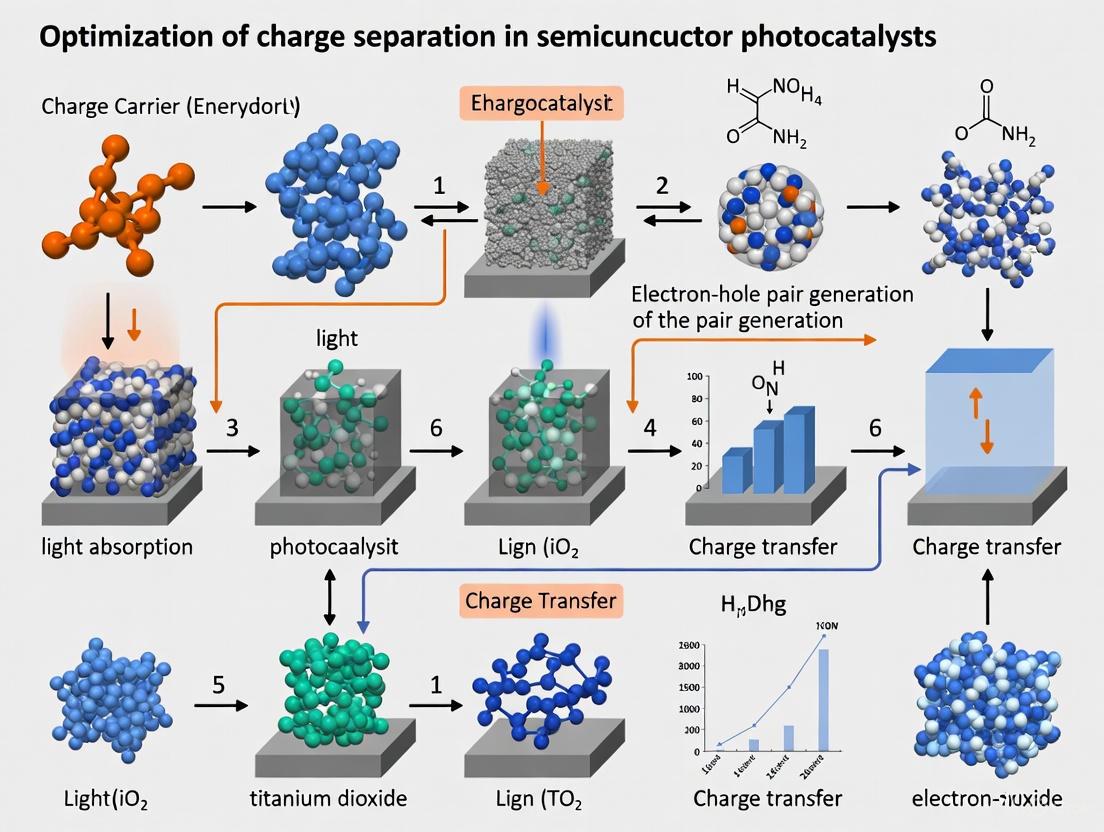

This article comprehensively reviews advanced strategies for enhancing charge separation in semiconductor photocatalysts, a critical factor determining photocatalytic efficiency.

Strategies for Optimizing Charge Separation in Semiconductor Photocatalysts: From Mechanisms to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article comprehensively reviews advanced strategies for enhancing charge separation in semiconductor photocatalysts, a critical factor determining photocatalytic efficiency. It covers the fundamental principles of charge carrier dynamics, explores cutting-edge heterojunction designs like non-covalent donor-acceptor composites and Z-scheme systems, and details optimization techniques including cocatalyst loading and doping. The content specifically addresses validation methods through advanced characterization and provides a comparative analysis of different approaches. Special emphasis is placed on applications relevant to biomedical and pharmaceutical research, including drug degradation and antimicrobial activity, offering researchers a scientific foundation for developing high-performance photocatalytic systems.

The Fundamental Challenge: Understanding Charge Carrier Dynamics and Recombination Pathways

The Critical Role of Charge Separation in Photocatalytic Efficiency

In semiconductor photocatalysis, the absorption of light generates electron-hole pairs. The efficient separation of these photogenerated charges is a critical determinant of overall photocatalytic performance, as it directly influences the number of charge carriers available to drive chemical reactions. Rapid recombination of these charges is a primary factor limiting the efficiency of photocatalytic processes, including hydrogen evolution and nitrogen reduction for ammonia synthesis.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Problems

FAQ 1: My photocatalyst shows low activity despite high purity materials. What could be the cause?

Low photocatalytic activity often stems from inefficient charge separation. This can be due to:

- Suboptimal Heterojunction Design: The energy band alignment between semiconductor components may not facilitate proper charge transfer. Constructing a Z-scheme heterostructure, as demonstrated in Zn-Ni₂P/g-C₃N₄ systems, can significantly improve charge separation by creating an interfacial electric field (IEF) that directs electron flow [1].

- High Bulk Recombination: Defects within the catalyst bulk can act as recombination centers. Strategies like doping (e.g., Zn doping in Niâ‚‚P) can modify the electronic structure and reduce recombination [1].

- Insufficient Active Sites: Even with successful charge separation, a lack of sites for the desired reaction (e.g., Hâ‚‚ evolution) will limit output. Loading cocatalysts like Niâ‚‚P provides active sites and can further enhance charge separation [1].

FAQ 2: How can I confirm that my material's activity is genuine and not a false positive?

False positives are a significant challenge, especially in reactions like photocatalytic nitrogen reduction where ammonia yields can be low.

- Control for Contaminants: Nitrogenous contaminants from feed gases, the experimental setup, or even the catalysts themselves can lead to false ammonia readings [2]. Implement rigorous purification of gases using acid traps or reduced copper catalysts and clean all equipment meticulously with deionized water [2].

- Conduct Rigorous Control Experiments: Always perform control experiments without light, without catalyst, and with an inert gas like Argon. The use of ¹âµNâ‚‚ isotope labeling is a definitive method to confirm that ammonia originates from dinitrogen reduction rather than contaminants [2].

- Report Original Data: To provide a clear view of potential contaminants, report photocatalyst activity as ammonia concentration versus time and include the unnormalized original data from control experiments [2].

FAQ 3: My photocatalyst deactivates quickly during repeated use. How can I improve its stability?

Deactivation can occur due to photocorrosion, poisoning, or structural changes.

- Identify Deactivation Sources: Common poisons include metal oxides/hydroxides (e.g., from Fe(III) ions in wastewater), polymeric aromatics from air pollutants, or precipitated carbon-containing materials that block active sites and UV light [3].

- Test for Longevity: A single activity measurement is only a snapshot. Probe the longevity of your material under accelerated conditions relevant to its application (e.g., accelerated weathering for outdoor coatings, repeated washing for fabrics) [3]. Some materials may even require an initial "break-in" period to reveal their optimal performance [3].

Quantitative Performance of Charge Separation Strategies

The table below summarizes key strategies for enhancing charge separation and their impact on photocatalytic performance.

Table 1: Strategies for Improving Charge Separation in Photocatalysts

| Strategy | Mechanism | Exemplary Material | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Z-Scheme Heterojunction | Mimics natural photosynthesis; enables spatial separation of electrons and holes while preserving strong redox ability [1]. | Zn-Niâ‚‚P/g-C₃Nâ‚„ | Hydrogen production rate: 1077 μmol gâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹ under visible light; stability up to 49 hours [1]. |

| Interfacial Electric Field (IEF) | Creates a built-in electric field at the heterojunction interface that drives the directional migration of photogenerated charges, preventing recombination [1]. | Zn-Ni₂P/g-C₃N₄ | IEF directed from Zn-Ni₂P to g-C₃N4, accelerating charge separation [1]. |

| Cocatalyst Loading | Serves as an electron sink and provides active reaction sites, thereby extracting charges from the semiconductor and facilitating surface reactions [1]. | Ni₂P, Pt | Zn-Ni₂P/g-C₃N₄ performance exceeded that of Pt/g-C₃N₄ [1]. |

| Doping Modification | Alters the electronic structure and band gap of the semiconductor, which can create internal trapping sites to reduce bulk electron-hole recombination [1]. | Zn-doped Niâ‚‚P | Zn doping led to an upshift of the p-band state density, favorable for H* adsorption in the HER [1]. |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Synthesis of a Z-Scheme Heterojunction Photocatalyst

This protocol outlines the synthesis of Zn-Ni₂P/g-C₃N₄, a model system for efficient charge separation [1].

- Synthesis of g-C₃N₄ Precursor: Typically, g-C₃N₄ nanosheets are prepared by the thermal polycondensation of nitrogen-rich precursors like melamine or urea.

- Preparation of NiZn-LDH/g-C₃N₄ Composite:

- Dissolve Zinc acetate (Zn(AC)₂·2H₂O, 0.1 mmol), Nickel chloride (NiCl₂·6H₂O, 0.45 mmol), and Urea (3 mmol) in 60 mL of a methanol-water solution (2:3 volume ratio) [1].

- Add a specific mass of g-C₃N₄ (e.g., 25-100 mg) to the solution and stir for 30 minutes.

- Transfer the solution to a 100 mL Teflon-lined autoclave and hydrothermally treat at 170°C for 17 hours.

- After cooling, collect the precipitate (NiZn/g-C₃N₄) by centrifugation, wash with water and ethanol, and dry at 60°C.

- Phosphidation to Form Zn-Ni₂P/g-C₃N₄:

- Place the obtained NiZn/g-C₃N₄ powder and a red phosphorus source in separate porcelain boats inside a tube furnace, with the phosphorus source positioned upstream.

- Heat under a constant Argon flow to a high temperature (e.g., 500°C) for a set time to convert the precursor into the final Zn-Ni₂P/g-C₃N₄ Z-scheme heterojunction [1].

Protocol 2: Standardized Activity Testing and Validation

Ensuring reliable and reproducible activity data is paramount.

- Photocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution Test:

- Disperse a known mass of photocatalyst (e.g., 50 mg) in an aqueous solution containing a sacrificial electron donor (e.g., methanol or triethanolamine).

- Seal the reaction system and evacuate to remove air.

- Irradiate the suspension with a visible-light source (e.g., a 300 W Xe lamp with a UV-cutoff filter).

- Use gas chromatography (GC) with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD) to quantify the evolved hydrogen gas at regular intervals [1].

- Validation Tests to Mitigate False Positives:

- Gas Purity: Purify feed gases (Nâ‚‚, Ar) by passing them through acid solutions (e.g., 0.05 M Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„) to remove ammonia and through KMnOâ‚„ alkaline solution or a reduced copper catalyst to eliminate NOx contaminants [2].

- System Cleanliness: Rigorously wash all reactor components, glassware, and tubing with fresh deionized water before experiments to remove ambient nitrogenous contaminants [2].

- Control Experiments: Always run dark controls (light off, catalyst present) and negative controls (light on, no catalyst) to establish a baseline. For Nâ‚‚ reduction, an Argon control is essential [2].

Visualization of Mechanisms and Workflows

Diagram 1: Charge Separation in a Z-Scheme Heterojunction

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Photocatalyst Optimization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Photocatalytic Charge Separation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| g-C₃N₄ | A popular, metal-free, 2D semiconductor substrate with a suitable bandgap for visible light response. Serves as a base for constructing heterojunctions [1]. | Often synthesized from low-cost precursors like urea or melamine. Its intrinsic charge separation is poor, making it an ideal model for modification [1]. |

| Transition Metal Phosphides (TMPs) | Act as highly effective cocatalysts and heterojunction components. They provide good electrical conductivity, metallic character, and abundant active sites for reactions like the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction (HER) [1]. | Niâ‚‚P and Zn-doped Niâ‚‚P are prominent examples. Their high work function facilitates the formation of an Interfacial Electric Field in heterostructures [1]. |

| Methylene Blue (MB) / Indicator Inks | Used for rapid, qualitative screening of photocatalytic activity, especially for self-cleaning function. The visible color change indicates electron reduction capability [3]. | A non-ISO but rapid test. Useful for initial screening of low-activity samples or for testing the uniformity of a photocatalytic film [3]. |

| 4-Chlorophenol | A model pollutant used in standardized tests (ISO) to quantify the activity of powder photocatalysts for water purification applications [3]. | Measures the degradation kinetics of a stable organic compound, providing a benchmark for oxidative activity. |

| Stearic Acid | A model organic contaminant used in standardized tests (ISO) to evaluate the self-cleaning performance of photocatalytic surfaces [3]. | The decrease in stearic acid layer thickness, measured by IR spectroscopy, correlates with photocatalytic oxidation efficiency. |

| Sm21 maleate | Sm21 maleate, CAS:155058-71-2, MF:C22H28ClNO7, MW:453.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| XV638 | XV638, CAS:183854-11-7, MF:C41H38N6O5S2, MW:758.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between bulk and surface recombination, and why does it matter for photocatalytic efficiency?

Bulk recombination occurs when photogenerated electrons and holes recombine inside the photocatalyst material before they can reach the surface to participate in chemical reactions. This process typically happens on a timescale of picoseconds, which is much faster than the hundreds of picoseconds required for charges to travel to the surface. Surface recombination occurs when charges that have successfully reached the surface recombine there instead of engaging in redox reactions. Bulk recombination is particularly detrimental as it represents the majority of charge carrier loss, severely limiting the availability of electrons and holes for catalytic applications such as hydrogen production or pollutant degradation [4].

Q2: What experimental strategies can I use to specifically suppress bulk recombination?

Constructing a Bulk Internal Electric Field (BIEF) is considered one of the most effective strategies. This built-in electric field provides a powerful driving force to mediate bulk charge transfer and separation, accelerating the movement of carriers toward the surface and reducing their chances of recombining internally. BIEF can be enhanced through various material engineering approaches including bulk heteroatom doping, vacancy engineering, ion intercalation, and crystal facet engineering, all of which increase the asymmetry of the crystal structure to strengthen this internal field [4].

Q3: How does creating a heterojunction between two semiconductors help reduce recombination?

Heterojunctions, particularly type-II and Z-scheme architectures, facilitate spatial separation of electrons and holes between different materials. In a direct Z-scheme system, for instance, electrons in the conduction band of one semiconductor combine with holes in the valence band of another at the interface. This selective recombination preserves the most reactive electrons and holes with the strongest redox potentials, thereby simultaneously enhancing charge separation and maintaining high catalytic activity. The formation of an internal electric field at the heterojunction interface further drives this directional charge separation [5] [6].

Q4: My photocatalyst shows good charge separation but poor surface reaction kinetics. What surface modifications can help?

Surface modification with cocatalysts can provide additional active sites and improve surface reaction kinetics. For instance, loading transition metal dichalcogenides like NiS₂ onto g-C₃N₄ creates more active sites for the oxygen reduction reaction. Additionally, covalent organic framework (COF) engineering through molecular-level surface functionalization can optimize electron cloud density distribution at the surface, which improves the separation efficiency of electron-hole pairs that reach the surface and increases the number of active sites per unit volume [7] [8].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Rapid Recombination of Photogenerated Carriers

Symptoms:

- Low quantum efficiency despite good light absorption

- Short charge carrier lifetimes measured by transient absorption spectroscopy

- Weak photoluminescence intensity indicating dominant non-radiative recombination

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Tests | Solution Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Strong bulk recombination | Time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL), Surface photovoltage (SPV) measurements [4] | Engineer Bulk Internal Electric Field (BIEF) through heteroatom doping or vacancy creation [4] |

| Ineffective charge separation at interface | Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), Photocurrent response measurements [6] | Construct type-II heterojunctions or Z-scheme systems for spatial charge separation [5] [6] |

| Poor surface active sites | Adsorption capacity tests, Reactive oxygen species (ROS) detection [6] | Decorate with cocatalysts (e.g., NiSâ‚‚) or create surface defects to provide more reaction sites [7] |

| Weak internal electric field | Kelvin probe force microscopy (KPFM), Band structure calculations [4] | Use ferroelectric/piezoelectric materials or crystallographic orientation control to enhance BIEF [4] |

Problem: Inefficient Solar Energy Conversion

Symptoms:

- Poor performance under visible light despite good UV activity

- Low solar-to-hydrogen efficiency

- Limited photocatalytic activity for target reactions

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Tests | Solution Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Large band gap material | UV-Vis diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (DRS), Tauc plot analysis [9] | Elemental doping or formation of solid solutions to narrow band gap [9] |

| Mismatched band alignment | X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), Valence band XPS [5] | Design S-scheme or Z-scheme heterojunctions to optimize redox potential [5] |

| Insufficient visible light absorption | UV-Vis DRS, Optical absorption coefficient calculation [10] | Develop 2D/2D heterostructures with enhanced light harvesting [7] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Constructing a 2D/2D Heterojunction with Reverse Barrier Layer

Objective: Create a NiS₂/g-C₃N₄ heterojunction with enhanced charge separation for H₂O₂ production [7].

Materials:

- Urea (precursor for g-C₃N₄)

- Nickel sulfide (NiSâ‚‚) cocatalyst

- Ethanol and deionized water

- Acetic acid (catalyst)

Procedure:

- Synthesize 2D g-C₃N₄: Thermal polymerize urea at 580°C in air, then stir the resulting product in pure water at room temperature for 24 hours and dry [7] [8].

- Prepare 2D NiS₂: Use hydrothermal method at 80°C for 6 hours [7].

- Form heterojunction: Employ electrostatic self-assembly by mixing the oppositely charged 2D CN and 2D NiSâ‚‚ components, leveraging their zeta potential values of approximately -19 mV and 2 mV respectively [7].

- Characterize: Use XRD to confirm structure, FTIR to verify chemical bonding, and XPS to analyze surface composition [7].

Key Parameters:

- The reverse barrier layer creates an internal electric field where the field force and band bending produce forces in the same direction upon photogenerated electron transfer [7].

- This configuration enables electrons on NiS₂ to reduce O₂ to form •O₂⻠radicals, which subsequently generate H₂O₂ [7].

Protocol 2: Quantitative Analysis of Charge Separation Efficiency

Objective: Quantitatively evaluate the effectiveness of charge separation strategies [4].

Materials:

- Photocatalyst samples

- Electrochemical workstation with standard three-electrode cell

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer

- Time-resolved fluorescence spectrometer

Procedure:

- Photoelectrochemical measurements:

Spectroscopic characterization:

Photocatalytic activity assessment:

Data Presentation

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Charge Separation Strategies

| Strategy | Material System | Charge Separation Efficiency Improvement | Quantum Efficiency (%) | Key Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reverse Barrier Layer | 2D/2D NiS₂/g-C₃N₄ [7] | Significant improvement in electron-hole separation | Not reported | Internal electric field and band bending synergy [7] |

| BIEF Engineering | Doped/Ferroelectric Materials [4] | Enhanced bulk charge separation | Varies by material | Spontaneous polarization-induced internal field [4] |

| Z-Scheme Heterojunction | Bi₂WO₆/ZnIn₂S₄ [6] | Efficient spatial charge separation | Not reported | Directional charge transfer across interface [6] |

| Surface Modification | CN-306 COF [8] | Enhanced electron-hole distribution | 7.27% (at 420 nm) | Optimized electron cloud density redistribution [8] |

| Type-II vdWHs | MoTeâ‚‚/Tlâ‚‚O [10] | Suppressed carrier recombination | ~2% (Power conversion) | Interlayer electric field-driven separation [10] |

Table 2: Characterization Techniques for Recombination Analysis

| Technique | Information Obtained | Applicability | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (TRPL) | Charge carrier lifetime, recombination kinetics [4] | Bulk and surface recombination | Requires specialized equipment |

| Surface Photovoltage (SPV) | Surface charge separation efficiency [4] | Surface and interface recombination | Semi-quantitative |

| Open-Circuit Photovoltage Decay | Charge separation and recombination dynamics [7] | Overall recombination assessment | Indirect measurement |

| Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) | Charge transfer resistance, interfacial properties [6] | Interface characterization | Complex data interpretation |

| Mott-Schottky Analysis | Band alignment, carrier concentration [5] | Heterojunction characterization | Requires specific conditions |

Visualization

Diagram 1: Charge Separation Pathways in Heterojunctions

Charge Separation Mechanisms

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Recombination Analysis

Recombination Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Material/Reagent | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Urea | Precursor for g-C₃N₄ synthesis [7] [8] | Thermal polymerization to create 2D carbon nitride base material [7] |

| Transition Metal Dichalcogenides (NiS₂) | Cocatalyst for active site provision [7] | Creating reverse barrier layer heterojunctions with g-C₃N₄ [7] |

| Terephthalaldehyde | Organic linker for COF formation [8] | Constructing covalent organic frameworks with enhanced charge separation [8] |

| Bismuth Tungstate (Bi₂WO₆) | Bi-based photocatalyst with narrow band gap [6] | Forming Z-scheme heterojunctions with ZnIn₂S₄ [6] |

| Zinc Indium Sulfide (ZnInâ‚‚Sâ‚„) | Ternary metal sulfide photocatalyst [6] | Creating staggered band alignment in heterostructures [6] |

| Ammonium Oxalate | Hole scavenger in photocatalytic reactions [6] | Trapping holes to study electron-driven reduction pathways [6] |

| AZ084 | AZ084|Potent CCR8 Antagonist For Research | AZ084 is a potent, selective, allosteric CCR8 antagonist (Ki=0.9 nM) for cancer and asthma research. This product is For Research Use Only, not for human consumption. |

| 6RK73 | 6RK73, MF:C13H17N5O2S, MW:307.37 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the fundamental roles of Band Gap Engineering and Internal Electric Fields in photocatalysis? Band gap engineering and internal electric fields (IEFs) are cornerstone principles for optimizing charge separation in semiconductor photocatalysts. Band gap engineering directly controls a material's light absorption capacity by adjusting the energy difference between its valence and conduction bands, ensuring optimal utilization of the solar spectrum. [11] Simultaneously, internally generated electric fields, which can arise from ferroelectric polarization, heterojunction interfaces, or facet junctions, provide a powerful driving force to physically separate photogenerated electrons and holes, thereby drastically reducing their recombination rate. [11] [12] The synergy between a well-designed band structure and a strong IEF is critical for achieving high photocatalytic efficiency. [13]

Q2: How can I consciously design a Z-scheme charge transfer pathway in a heterostructure? Conscious modulation of a Z-scheme pathway relies on two key factors: intimate interfacial contact and a well-defined internal electric field. Research on a ZnInâ‚‚Sâ‚„/MoSeâ‚‚ heterostructure demonstrates that forming atomic-level interfacial chemical bonds (e.g., Mo-S bonds) creates a direct "bridge" for charge transfer. [11] Furthermore, an internal electric field, established due to differences in work function between the two semiconductors, provides the directional driving force that steers electrons from the conduction band of one component to recombine with the holes in the valence band of the other. This preserves the most energetic charges for redox reactions. [11]

Q3: Why does my ferroelectric photocatalyst, which has a strong intrinsic polarization field, show poor activity? A strong bulk polarization field does not guarantee high surface reactivity. In ferroelectric materials like PbTiO₃, surface defects can trap charge carriers and become recombination centers. [12] For instance, Ti vacancy defects near the positively polarized facets of PbTiO₃ were found to trap electrons and promote recombination, severely impeding photocatalytic performance. This indicates that inefficient charge utilization at the surface, rather than a lack of charge separation in the bulk, is often the limiting factor. [12] Mitigating these surface defects is essential for translating efficient bulk separation into surface reactions.

Q4: What are some practical strategies to enhance the Internal Electric Field in a particulate photocatalyst? Several advanced strategies have proven effective:

- Constructing Inter-facet Junctions: Engineering crystals with specific exposed facets (e.g., {010} and {110} facets on BiVOâ‚„) creates a natural potential difference, forming an IEF that drives spatial charge separation. [14]

- Ferroelectric Polarization: Utilizing single-domain ferroelectric materials (e.g., PbTiO₃) provides a permanent, strong built-in electric field for charge separation. [12]

- Building S-Scheme Heterojunctions: Coupling two semiconductors with matched band structures and Fermi levels generates an IEF at their interface, which facilitates the desired Z-scheme-like charge transfer. [15] [11]

- Creating an Electron Transfer Layer (ETL): Modifying a surface with a specific ETL, as demonstrated with NaOH-etched BiVOâ‚„:Mo, can intensify the existing inter-facet IEF by over 10 times, leading to exceptional charge separation efficiency exceeding 90%. [14]

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem Phenomenon | Possible Root Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Proposed Solution & Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low photocatalytic efficiency despite good light absorption. | Severe bulk charge recombination due to insufficient driving force for separation. | Perform surface photovoltage spectroscopy or transient absorption spectroscopy to monitor charge lifetime. [16] | Solution: Introduce a stronger Internal Electric Field via heterojunction or ferroelectric engineering. [17] [12]Rationale: The IEF provides a directional force that actively pulls electrons and holes apart, reducing recombination. |

| Z-scheme heterostructure performs no better than a simple mixture. | Poor interfacial contact leading to inefficient charge transfer between components. | Conduct HRTEM to examine interface intimacy; use XPS to check for interfacial chemical bonds. [11] | Solution: Employ a defect-induced strategy to form atomic-level interfacial chemical bonds (e.g., Mo-S bonds). [11]Rationale: Chemical bonds act as atomic-scale "bridges," enabling rapid Z-scheme charge flux instead of random diffusion. |

| Ferroelectric photocatalyst shows low activity despite a monodomain structure. | Surface defects (e.g., vacancies) acting as charge traps and recombination centers. [12] | Use HR-STEM and Electron Energy Loss Spectroscopy (EELS) to analyze surface atomic structure and defect states. [12] | Solution: Selectively grow a passivation nanolayer (e.g., SrTiO₃ on PbTiO₃) to mitigate surface defects. [12]Rationale: The nanolayer eliminates trapping sites, creating an efficient electron transfer pathway and extending charge lifetime from microseconds to milliseconds. |

| Charge separation is inefficient in a visible-light oxide photocatalyst. | The intrinsic built-in electric field (e.g., from facet junctions) is too weak. | Use Kelvin Probe Force Microscopy (KPFM) to map the surface potential difference between different facets. [14] | Solution: Construct an Electron Transfer Layer (ETL) via surface etching/doping to enlarge the potential difference. [14]Rationale: The ETL intensifies the IEF by over 10 times, creating a cascade that drives exceptionally efficient spatial charge separation (>90%). |

Quantitative Data for Performance Comparison

Table 1: Performance metrics of selected photocatalytic systems employing band gap and IEF engineering.

| Photocatalytic System | Engineering Strategy | Key Performance Metric | Enhancement Factor vs. Baseline | Reference / Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZnO/MoSâ‚‚ Layered Heterostructure | Solution-phase heterostructure for physical charge separation. | 50% higher efficiency in rhodamine B degradation. | 1.5x vs. individual or physically mixed materials. | [18] |

| Sv-ZnInâ‚‚Sâ‚„/MoSeâ‚‚ Z-Scheme | Interfacial Mo-S bond & IEF modulation. | Hâ‚‚ evolution: 63.21 mmol·gâ»Â¹Â·hâ»Â¹; AQY @420nm: 76.48%. | ~18.8x higher Hâ‚‚ rate vs. pristine ZnInâ‚‚Sâ‚„. | [11] |

| PbTiO₃/SrTiO₃ Core/Shell | Surface defect passivation on a ferroelectric material. | Apparent Quantum Yield for overall water splitting @365nm. | 400x enhancement vs. unmodified PbTiO₃. | [12] |

| BiVOâ‚„:Mo with ETL | Electron Transfer Layer to intensify inter-facet IEF. | Charge separation efficiency @420nm: >90%. | IEF intensity enhanced by ~12x. | [14] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Objective: To create a well-defined 2D/2D heterostructure via a straightforward solution-based method for enhanced visible-light photocatalysis.

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Zinc Salt Precursor: e.g., Zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O).

- Molybdenum Source: Ammonium molybdate tetrahydrate ((NH₄)₆Mo₇O₂₄·4H₂O).

- Sulfur Source: Thiourea (CHâ‚„Nâ‚‚S).

- Reaction Solvent: Deionized water.

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Dispersion of Template: Begin by dispersing a pre-synthesized few-layer MoSâ‚‚ suspension in deionized water.

- Precursor Addition: Introduce the zinc salt precursor (e.g., Zn(NO₃)₂) into the suspension under constant stirring. The Zn²⺠ions are attracted to and stabilized on the surface of the MoS₂ layers.

- Hydroxide Formation: Slowly add a mild base (e.g., NaOH) to the solution. This induces the formation of a zinc hydroxide intermediate phase that nucleates epitaxially on the MoSâ‚‚ template.

- Hydrothermal Transformation: Transfer the mixture into a Teflon-lined autoclave and subject it to a controlled hydrothermal treatment (e.g., 120-180°C for several hours). This step facilitates the in-situ dehydration and transformation of the zinc hydroxide intermediate into two-dimensional ZnO layers.

- Product Isolation: After the reaction, allow the autoclave to cool naturally. Collect the resulting precipitate by centrifugation, and wash it thoroughly with water and ethanol to remove any ionic residues.

- Final Processing: Dry the final product, a layered ZnO/MoS₂ heterostructure, in an oven at 60-80°C.

Objective: To fabricate a direct Z-scheme Sv-ZnInâ‚‚Sâ‚„/MoSeâ‚‚ photocatalyst by utilizing sulfur vacancies (Sv) as anchoring sites for intimate Mo-S bond formation.

Key Reagent Solutions:

- ZIS Precursors: Zinc chloride (ZnCl₂), Indium chloride (InCl₃), and Thioacetamide (C₂H₅NS).

- Defect-Inducing Agent: Hydrazine Monohydrate (N₂H₄·H₂O) – crucial for creating S-vacancies and coordinatively unsaturated S atoms.

- MoSeâ‚‚ Precursors: Sodium molybdate (Naâ‚‚MoOâ‚„) and Selenium powder (Se).

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Synthesize Sv-Rich ZnIn₂S₄ (Sv-ZIS): Hydrothermally react Zn, In, and S precursors in the presence of N₂H₄·H₂O. The hydrazine selectively creates S-vacancies, resulting in a flower-like Sv-ZIS microsphere.

- Anchor Molybdenum: Disperse the as-synthesized Sv-ZIS in a solvent. Introduce a molybdenum source (e.g., Naâ‚‚MoOâ‚„). The coordinatively unsaturated S atoms at the vacancy sites will act as atomic anchors for Mo atoms, forming initial Mo-S bonds.

- In-situ Growth of MoSeâ‚‚: Add a Se source to the mixture. Under a second hydrothermal treatment, the pre-anchored Mo reacts with Se to in-situ grow MoSeâ‚‚ nanosheets directly on the Sv-ZIS surface, ensuring an intimate interface with covalent Mo-S bonds.

- Characterize the Interface: Confirm the successful formation of the heterostructure and the Mo-S bonds using HRTEM and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS).

- Validate the Z-Scheme Mechanism: Use Surface Photovoltage Spectroscopy (SPS) and DMPO spin-trapping Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) to provide direct evidence of the Z-scheme charge transfer path.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key reagents and materials for advanced photocatalyst synthesis and characterization.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrazine Monohydrate (N₂H₄·H₂O) | A defect-inducing agent that creates anion vacancies (e.g., S-vacancies) and generates coordinatively unsaturated atoms for subsequent heterostructure bonding. [11] | Creating S-vacancies in ZnIn₂S₄ to serve as anchors for MoSe₂ growth. [11] |

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) | An etching agent that selectively dissolves surface atoms, enabling the formation of an Electron Transfer Layer (ETL) and incorporation of modifying ions. [14] | Creating a complex defect-based ETL on BiVOâ‚„:Mo to intensify the internal electric field. [14] |

| Strontium Titanate (SrTiO₃) Precursors | A passivation layer material grown epitaxially on ferroelectric surfaces to mitigate charge-trapping surface defects. [12] | Coating PbTiO₃ to eliminate Ti-defect sites, enabling efficient electron transfer to cocatalysts. [12] |

| DMPO (5,5-Dimethyl-1-Pyrroline N-Oxide) | A spin-trapping agent used in Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) spectroscopy to detect and identify short-lived free radical intermediates generated during photocatalysis. [11] | Experimentally proving the Z-scheme mechanism by directly detecting the reactive radical species generated on specific semiconductor components. [11] |

| NCT02 | NCT02, CAS:790245-61-3, MF:C17H16N2O2S, MW:312.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| ANI-7 | ANI-7|Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Activator | ANI-7 is a potent AhR pathway activator that inhibits cancer cell growth. This product is for research use only (RUO) and not for human use. |

Thermodynamic and Kinetic Barriers in Photo-redox Reactions

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why does my photocatalytic reaction proceed slowly even with a thermodynamically favorable catalyst?

The reaction rate is governed by kinetic barriers, not just thermodynamic feasibility. The highest energy transition state controls the overall rate. In photoredox/nickel dual catalysis, for instance, the slowest step could be single-electron transfer, radical generation, or reductive elimination, depending on your specific substrates and conditions [19]. The measured redox potentials confirm thermodynamic viability, but the kinetics of bimolecular radical processes ultimately determine efficiency [19].

FAQ 2: Why is water removal critical in my photocatalytic system, and what methods are effective?

Water can hydrolyze sensitive intermediates, driving the reaction backward. Effective water removal via azeotropic distillation with a Dean-Stark apparatus is often essential, as molecular sieves or desiccants like Naâ‚‚SOâ‚„ may prove insufficient [20]. Physically removing water shifts equilibrium forward, providing both thermodynamic driving force and kinetic acceleration by preventing intermediate decomposition [20].

FAQ 3: How do I identify whether thermodynamics or kinetics limits my photoreaction efficiency?

Perform a thorough mechanistic investigation. Use cyclic voltammetry to establish thermodynamic feasibility of electron transfers [19]. Then apply kinetic analysis like Stern-Volmer studies or laser flash photolysis to identify rate-limiting steps [19]. For semiconductor photocatalysts, spatially resolve reactive sites using techniques like scanning photoelectrochemical microscopy (SPECM) to distinguish between charge separation kinetics and surface reaction thermodynamics [21].

FAQ 4: What strategies can overcome slow charge separation in semiconductor photocatalysts?

Design heterostructures with built-in interfacial electric fields (IEF). Z-scheme heterojunctions between materials with different work functions create IEFs that direct electron-hole separation [1]. For example, Zn-Ni₂P/g-C₃N₄ composites achieve 5.5-fold higher internal electric fields, dramatically improving charge separation and hydrogen evolution rates [1]. Doping and non-covalent coordination in donor-acceptor structures also create asymmetric electron distribution that facilitates charge separation [22].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Quantum Efficiency Despite Strong Light Absorption

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Rapid electron-hole recombination outpacing surface reactions.

- Solution: Engineer stronger interfacial electric fields via Z-scheme heterojunctions. The built-in electric field directionally separates charges [1].

- Experimental Protocol: Synthesize Zn-Ni₂P/g-C₃N₄ composites through hydrothermal reaction coupled with in-situ phosphating. Confirm IEF strength via work function measurements and DFT calculations [1].

Cause: Mismatch between exciton lifetime and reaction timescale.

- Solution: Select materials where strongly-bound excitons (like A-excitons in MoSâ‚‚) outperform weakly-bound ones. In MoSâ‚‚ monolayers, A-excitons show higher internal quantum efficiency than C-excitons [21].

- Experimental Protocol: Use scanning photoelectrochemical microscopy (SPECM) to spatially map quantum efficiency according to exciton type at different excitation wavelengths [21].

Cause: Poor charge transport to active sites.

- Solution: Optimize material morphology to enhance carrier mobility. In MoSâ‚‚ monolayers, photogenerated electrons can travel >80 microns while holes remain stationary [21].

- Experimental Protocol: Employ aligned-unaligned SPECM measurements to separately track electron and hole transport distances and identify charge transport bottlenecks [21].

Problem: Inconsistent Reaction Rates Across Different Experimental Setups

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Variations in water contamination affecting sensitive intermediates.

- Solution: Implement standardized azeotropic water removal using Dean-Stark apparatus rather than variable efficiency desiccants [20].

- Experimental Protocol: Fit water removal rate constants (k₆ ≈ 2.33×10â»â´ sâ»Â¹) in kinetic models to ensure >99.9% water removal (dryness <25 ppm) for consistent results [20].

Cause: Unidentified rate-determining steps that change with conditions.

- Solution: Construct comprehensive kinetic models incorporating all potential bottlenecks - chemical steps and physical processes like water removal [20].

- Experimental Protocol: Use previously reported DFT energy landscapes to build kinetic networks, then fit experimental data to identify whether dehydration, nucleophilic coupling, or physical separation processes limit rates under your specific conditions [20].

Problem: Poor Catalyst Stability or Rapid Deactivation

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Oxidation state instability in transition metal catalysts.

- Solution: Understand the complete oxidation state landscape. Nickel catalysts, for instance, can access Niâ°, Niá´µ, Niᴵᴵ, Niᴵᴵᴵ, and Niᴵⱽ states, each with different stabilities [19].

- Experimental Protocol: Employ EPR spectroscopy to detect paramagnetic intermediates and DFT calculations to map oxidation state stability under reaction conditions [19].

Cause: Spatial separation of oxidation and reduction sites causing charge buildup.

- Solution: Balance oxidation and reduction site distribution. In MoSâ‚‚ monolayers, oxidation occurs primarily at edges/corners while reduction happens across the basal plane [21].

- Experimental Protocol: Use SPECM in substrate generation-tip collection mode to spatially map oxidation (negative ΔI) and reduction (positive ΔI) sites separately, then optimize catalyst design accordingly [21].

Table 1: Performance Metrics for Photocatalytic Systems

| Photocatalytic System | Reaction Type | Key Performance Metric | Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zn-Niâ‚‚P/g-C₃Nâ‚„ Z-scheme | Hydrogen Evolution | Production Rate | 1077 μmol gâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹ | [1] |

| Stability Duration | 49 hours | [1] | ||

| NiO-UPDI donor-acceptor | Ciprofloxacin Degradation | Degradation Rate Constant | 0.553 hâ»Â¹ | [22] |

| MoSâ‚‚ Monolayer | Hydrogen Evolution | Detection Current (SPECM) | ~0.5 pA | [21] |

| Redox-Neutral Catalytic Mitsunobu | Esterification | Rate Constant for Water Removal | 2.33×10â»â´ sâ»Â¹ | [20] |

Table 2: Thermodynamic and Kinetic Parameters for Reaction Analysis

| Parameter Type | Specific Measurement | Application in Photo-redox Reactions | Reference Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermodynamic | Redox Potentials | Feasibility of single-electron transfer | Cyclic Voltammetry [19] |

| Kinetic | Quenching Rate Constants | Bimolecular electron transfer efficiency | Stern-Volmer Analysis [19] |

| Spatial Resolution | Quantum Efficiency Maps | Reactive site activity distribution | SPECM [21] |

| Energy Barriers | Transition State Energies | Rate-determining step identification | DFT Calculations [20] |

| Charge Separation | Internal Electric Field Strength | Electron-hole separation efficiency | Work Function Measurements [1] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: SPECM for Spatial Mapping of Photocatalytic Sites

Principle: Scanning photoelectrochemical microscopy (SPECM) enables spatial resolution of reactive sites with ~200 nm resolution and direct quantification of redox reactions under illumination [21].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Grow MoSâ‚‚ monolayers on SiOâ‚‚/Si substrates via chemical vapor deposition [21].

- Characterization: Verify monolayer properties through photoluminescence (PL) and Raman spectroscopy (Δpeak = Eâ‚‚g-Aâ‚g ≈ 19 cmâ»Â¹) [21].

- SPECM Setup: Configure in substrate generation-tip collection mode with ultramicroelectrode (UME) probe [21].

- Photo-oxidation Mapping: Use ferrocene dimethanol mediator, measure ΔI = I({}{\text{T,Light}}) - I({}{\text{T,Dark}}) [21].

- Photoreduction Mapping: Detect Hâ‚‚ evolution from water, map reduction efficiency across surface [21].

- Data Analysis: Identify highest photoactivity regions - typically corners for oxidation, basal plane for reduction in MoSâ‚‚ [21].

Protocol 2: Z-Scheme Heterojunction Construction with Enhanced IEF

Principle: Creating heterostructures between semiconductors with different work functions generates interfacial electric fields that accelerate charge separation [1].

Procedure:

- Synthesis of NiZn-LDH: Hydrothermal treatment of Zn(AC)₂·2H₂O, NiCl₂·6H₂O, and urea in methanol-water solution at 170°C for 17 hours [1].

- Composite Formation: Repeat synthesis with varying g-C₃N4 amounts (25-100 mg) to create NiZn/g-C₃N₄ with different ratios [1].

- Phosphidation: Convert to Zn-Ni₂P/g-C₃N₄ using phosphorous source in tube furnace [1].

- Characterization: Confirm Z-scheme structure, measure work function differences, calculate IEF strength via DFT [1].

- Performance Testing: Evaluate hydrogen evolution under visible light, optimize for maximum production rate [1].

Visualization Diagrams

Diagram 1: Charge Separation in Z-Scheme Heterojunction. The interfacial electric field (IEF) directionally separates photogenerated electrons and holes to different reaction sites.

Diagram 2: Kinetic Barriers in Catalytic Reactions. Multiple transition states (TS1, TS2) represent kinetic bottlenecks, while physical processes like water removal provide thermodynamic driving force.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Photo-redox Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dean-Stark Apparatus | Azeotropic Water Removal | Redox-neutral Mitsunobu reaction [20] | Critical for >99.9% water removal (24.6 ppm) |

| g-C₃N₄ Nanosheets | 2D Semiconductor Support | Z-scheme heterojunction construction [1] | Suitable band structure (~2.7 eV), high surface area |

| Transition Metal Phosphides (Niâ‚‚P) | Cocatalyst for HER | Hydrogen evolution reactions [1] | Narrow band gap, high work function, metallic character |

| Ferrocene Dimethanol (FcDM) | Redox Mediator for SPECM | Mapping oxidation sites [21] | Single electron outer-sphere mechanism |

| Ultramicroelectrode (UME) | Electrochemical Probe | SPECM measurements [21] | ~200 nm spatial resolution for quantum efficiency mapping |

| Zn-Doped Niâ‚‚P | Enhanced IEF Generation | Donor-acceptor composites [1] | Creates asymmetric electron distribution, strengthens dipoles |

| CD532 | CD532, CAS:1639009-81-6, MF:C26H25F3N8O, MW:522.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Cmpda | Cmpda, CAS:380607-77-2, MF:C16H28N2O4S2, MW:376.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Advanced Material Designs and Heterojunction Strategies for Enhanced Charge Separation

FAQs: Fundamentals and Material Selection

Q1: What are the fundamental differences between Type-II, Z-Scheme, and S-Scheme heterojunctions?

The core difference lies in their charge transfer pathways and the resulting redox capabilities.

- Type-II: Designed for optimal spatial charge separation. Electrons and holes migrate to different semiconductors, reducing their chance to recombine. However, this places the electrons at a lower (less negative) conduction band and the holes at a lower (less positive) valence band, which weakens their redox power [23].

- Z-Scheme: Designed to preserve strong redox power. This system mimics natural photosynthesis, combining the strong reduction potential of one semiconductor with the strong oxidation potential of another. This is achieved by recombining the less useful electrons and holes at the interface, leaving the most energetic charge carriers available for reactions [23] [24].

- S-Scheme: A modern refinement of the direct Z-Scheme. It provides a more detailed mechanistic explanation, emphasizing the role of an internal electric field (IEF), band bending, and Coulomb attraction in driving the selective recombination of less useful charges, thereby preserving the most powerful electrons and holes for catalysis [23] [25].

Table 1: Comparison of Heterojunction Charge Transfer Mechanisms and Outcomes.

| Heterojunction Type | Charge Transfer Pathway | Redox Capability | Key Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type-II | Electrons and holes move to different semiconductors spatially [23]. | Weakened | Sacrifices redox power for improved charge separation [23]. |

| Traditional Z-Scheme | Uses a liquid/solid mediator to recombine charges [24]. | Strong | Mediators can cause side reactions and light shielding [24]. |

| Direct Z-Scheme | Direct interfacial recombination without a mediator [23] [24]. | Strong | Requires high-quality interfaces; mechanism was debated [23] [24]. |

| S-Scheme | IEF and band bending drive selective charge recombination [23] [25]. | Strongest preserved | Can involve high contact resistance at the interface [23]. |

Q2: How do I choose between a Z-Scheme and an S-Scheme for my photocatalytic application?

The S-Scheme is now widely considered an optimized and mechanistically clarified version of the mediator-free direct Z-Scheme [23] [24]. If your goal is to achieve both superior charge separation and maintain maximum redox potential for demanding reactions like overall water splitting or COâ‚‚ reduction, designing an S-Scheme heterojunction is the recommended strategy. The S-Scheme framework provides clearer design principles, emphasizing the need for an oxidation photocatalyst (OP) with a low Fermi level and small work function, and a reduction photocatalyst (RP) with a high Fermi level and large work function to ensure a powerful internal electric field [23].

Q3: What are van der Waals (vdW) heterostructures and why are they beneficial?

Van der Waals heterostructures are constructed by stacking two-dimensional (2D) semiconductors through weak interlayer vdW forces, instead of requiring direct chemical bonding [24].

Benefits include:

- Overcoming Lattice Mismatch: They allow the combination of any two semiconductors without the stringent requirement of lattice matching, minimizing the formation of crystal defects [24].

- Preserving Intrinsic Properties: The weak vdW interaction helps maintain the original electronic properties of the individual components [24].

- Shortened Charge Migration Path: When built from 2D materials, photogenerated carriers are produced in atomically thin layers, drastically reducing the distance they must travel to reach the surface and participate in reactions [24].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Q4: My heterojunction shows poor photocatalytic activity. What could be the cause?

Poor activity often stems from inefficient charge separation or slow surface reaction kinetics.

- Insufficient Interface Contact: A primary cause is poor intimacy at the heterojunction interface. Without close contact, the internal electric field is weak, and charge carriers cannot efficiently transfer between components [23] [26].

- Solution: Employ in-situ growth methods to tightly anchor one component onto the other. For example, in-situ depositing MnWOâ‚„ nanoparticles onto Mnâ‚€.â‚…Cdâ‚€.â‚…S nanorods created an intimate and robust S-scheme interface [25].

- Rapid Bulk Recombination: Even with a good surface heterojunction, charge carriers may recombine within the bulk of the material before they can reach the surface [25].

- Solution: Engineer the bulk material to enhance charge separation. The creation of zinc blende/wurtzite superlattice interfaces inside Mnâ‚€.â‚…Cdâ‚€.â‚…S nanorods created homogeneous internal electric fields that drove ultrafast bulk charge separation [25].

- Lack of Active Sites: The surface may not have enough catalytic sites for the desired reaction (e.g., Hâ‚‚ evolution or COâ‚‚ reduction).

- Solution: Load cocatalysts like Pt, Ni, or Co₃O₄ onto the semiconductor surface. These act as electron sinks and lower the activation energy for surface reactions [27] [28].

Q5: How can I definitively prove the charge transfer mechanism in my heterojunction?

Verifying an S-scheme or Z-scheme pathway requires multiple complementary techniques to build conclusive evidence.

- In-situ Characterization: Use techniques like in-situ X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) under light illumination to observe shifts in core-level energy states, which provides direct evidence of band bending and electron flow driven by the internal electric field [25] [26].

- Radical Trapping Experiments: Conduct experiments to identify reactive species. In a true S-scheme, you should detect radicals generated by the highly positive holes in the OP (e.g., •OH from H₂O oxidation) and radicals generated by the highly negative electrons in the RP (e.g., •O₂⻠from O₂ reduction), confirming the preservation of strong redox potentials [23].

- Theoretical Calculations: Perform Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations to model the electronic structure, charge density difference, and work functions of the individual components and the heterojunction. This can theoretically predict the formation and direction of the internal electric field [26] [28].

- Ultrafast Spectroscopy: Techniques like transient absorption spectroscopy can track the flow and lifetime of photogenerated charges across the interface on picosecond timescales, directly visualizing the S-scheme charge transfer pathway [25].

Advanced Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Constructing a Direct Z-Scheme vdW Heterostructure for Water Splitting

This protocol outlines the synthesis of a non-lattice-matched heterostructure using weak van der Waals interactions.

- Material Selection: Choose two semiconductor materials with staggered band alignment (one with a more negative CB for H₂ evolution, e.g., PtS₂; another with a more positive VB for O₂ evolution, e.g., g-C₃N₄) [24].

- Exfoliation: Prepare single- or few-layer nanosheets of the selected semiconductors using techniques like liquid-phase exfoliation [24].

- Hybridization: Mix the dispersions of the two exfoliated nanomaterials. Use stirring, sonication, or self-assembly driven by electrostatic interactions to stack the layers and form the vdW heterostructure [24].

- Characterization: Confirm the successful formation and structure using:

- High-resolution TEM/HAADF-STEM: To observe the layered morphology and lattice fringes [25].

- Raman Spectroscopy: To detect the characteristic shifts that indicate interlayer coupling [24].

- UV-Vis Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy: To analyze the light absorption properties of the heterostructure [24].

Protocol 2: Engineering an S-Scheme Heterojunction with Enhanced Internal Electric Field

This protocol details the creation of a CdS/Co₃O₄ Z-scheme heterojunction with sulfur/oxygen dual vacancies to amplify the IEF [26].

- Create Defects: Synthesize defect-rich precursors. For example, generate sulfur vacancies in CdS (CdS-Sv) and oxygen vacancies in Co₃O₄ (Co₃O₄-Ov) through controlled calcination in inert/reducing atmospheres or chemical reduction methods [26].

- In-situ Growth: Couple the materials to form chemical bonds at the interface. Hydrothermally grow CdS-Sv nanoparticles onto Co₃O₄-Ov nanosheets (or vice-versa). This ensures intimate contact and creates atomic-scale channels for directional charge transfer [26].

- Verify the IEF and Mechanism:

- Use DFT calculations to simulate the charge density difference and plot the charge variation across the interface, which visually demonstrates the electron transfer direction and the formation of the IEF [26].

- Perform Kelvin Probe Force Microscopy (KPFM) to measure the surface potential difference and directly map the built-in electric field at the heterojunction interface [28].

- Conduct in-situ irradiated XPS to monitor the binding energy shifts of key elements (e.g., Cd, W) when the light is turned on, confirming the flow of electrons driven by the IEF [26].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Heterojunction Construction and Their Functions.

| Material / Reagent | Function in Heterojunction Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| g-C₃N₄ | A metal-free, stable polymer with a visible-light bandgap; often serves as the reduction photocatalyst (RP) in S-schemes [24] [28]. | PtS₂/g-C₃N₄ vdW heterostructure for water splitting [24]. |

| Mnâ‚€.â‚…Cdâ‚€.â‚…S Solid Solution | A tunable sulfide photocatalyst with excellent visible light absorption; can be engineered with internal superlattices [25]. | S-scheme heterojunction with MnWOâ‚„ for highly efficient Hâ‚‚ evolution [25]. |

| CdS-based Materials | A classic visible-light photocatalyst with a sufficiently negative CB for H₂ evolution; often modified to form heterojunctions [26]. | CdS-Sv/Co₃O₄-Ov Z-scheme for biomass conversion [26]. |

| TiO₂-based Materials | A benchmark UV-active photocatalyst; can be doped or modified to form heterojunctions for enhanced activity [24] [28]. | C,N-TiO₂/g-C₃N₄ direct Z-scheme [24]. |

| Defect Engineering Agents (e.g., NaBHâ‚„) | Chemical reductants used to create anion vacancies (S, O) in metal oxides/sulfides, which can modulate electronic structure and enhance IEF [26] [28]. | Creation of sulfur vacancies in CdS [26]. |

System Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the synergistic strategy of combining bulk and surface charge separation mechanisms, as demonstrated in a high-performance S-scheme system [25].

The following diagram details the charge transfer pathway in an S-scheme heterojunction, showing how strong redox capabilities are preserved [23] [25].

Within semiconductor photocatalyst research, achieving efficient spatial charge separation remains a fundamental challenge limiting overall energy conversion efficiency. Non-covalent donor-acceptor (D-A) composites present a promising strategy by creating organized molecular interfaces that facilitate directional electron transfer while maintaining structural flexibility. This technical framework examines the NiO-UPDI (urea perylene diimide) composite system, where a p-type semiconductor (NiO) and n-type organic semiconductor (UPDI) form non-covalent interfaces that enhance charge separation through complementary electronic properties.

The fundamental operating principle relies on creating type-II heterojunctions where the conduction and valence band alignment drives electron migration toward UPDI while holes transfer to NiO. This directional charge movement significantly reduces electron-hole recombination, extending carrier lifetime and enhancing photocatalytic activity. Unlike covalently-linked D-A systems requiring complex synthesis, non-covalent approaches like electrostatic self-assembly offer simpler fabrication while maintaining precise control over interfacial charge transfer processes.

Troubleshooting Guides: Experimental Challenges and Solutions

Poor Charge Separation Efficiency

Observed Symptoms: Low photocatalytic hydrogen evolution, high electron-hole recombination, minimal current response in photoelectrochemical measurements.

Material Stability and Degradation Issues

Observed Symptoms: Declining performance over reaction cycles, structural changes observed in TEM, leaching of components.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary advantage of non-covalent versus covalent D-A composites in the NiO-UPDI system?

Non-covalent approaches, particularly electrostatic self-assembly, offer simpler fabrication under mild conditions while maintaining effective charge separation. The ZnTCPP/C60-EDA system demonstrates this principle, achieving electron transfer through electrostatic interactions without complex covalent synthesis, resulting in hydrogen evolution rates of 113.5 μmol hâ»Â¹ [30]. The flexibility of non-covalent bonding allows for self-repairing interfaces and easier optimization of component ratios.

Q2: How does nitrogen doping enhance NiO performance in these composites?

Nitrogen doping serves multiple functions: it converts NiO from p-type to n-type character, enhances COâ‚‚ adsorption capacity, creates oxygen vacancies that serve as active sites, and significantly improves charge separation efficiency. In photocatalytic COâ‚‚ reduction, N-doped NiO achieves a CO yield of 235 μmol·gâ»Â¹Â·hâ»Â¹, which is 16.8 times higher than pristine p-type NiO [31].

Q3: What characterization techniques are essential for verifying successful non-covalent composite formation?

Key techniques include:

- Zeta potential measurements to confirm electrostatic compatibility between components [30]

- Femtosecond transient absorption (fsTA) spectroscopy to directly observe charge transfer dynamics and excited state lifetimes [29]

- TEM with elemental mapping to verify homogeneous distribution without phase separation [29]

- XPS analysis to identify chemical states and interfacial interactions [31]

- Photoelectrochemical measurements to quantify charge separation efficiency [31]

Q4: Why choose UPDI over other organic semiconductors for this composite system?

UPDI possesses several advantageous properties: a strong built-in electric field that promotes intramolecular charge transfer, high thermal and chemical stability due to covalent urea linkages, appropriate energy level alignment with NiO for efficient electron transfer, and excellent visible light absorption capability [29] [33]. The covalent urea linkages in UPDI prevent disintegration under alkaline conditions that plagues self-assembled PDI systems [33].

Q5: How can I optimize the NiO:UPDI ratio for specific photocatalytic applications?

The optimal ratio depends on the target application:

- For photocatalytic hydrogen evolution, ratios of 1:2 to 1:3 (NiO:UPDI) typically perform best, similar to the ZnTCPP/C60-EDA system [30]

- For COâ‚‚ reduction, higher NiO content (up to 1:1) may be beneficial due to the COâ‚‚ adsorption enhancement from N-doped NiO [31]

- For pollutant degradation, lower UPDI content (3:1 to 2:1) can provide better stability in complex water matrices [33] Systematic screening with 5-7 different ratios is recommended while monitoring both activity and stability.

Experimental Protocols

Synthesis of Nitrogen-Doped NiO via Molten-Salt Method

Principle: The molten-salt environment creates a uniform liquid medium that facilitates homogeneous nitrogen incorporation into the NiO lattice, converting it from p-type to n-type character with enhanced conductivity and COâ‚‚ adsorption capability [31].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Precursor Preparation: Combine 2g Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O with 0.3g urea (nitrogen source) and 10g KCl (molten salt medium) in an agate mortar. Grind for 20 minutes until homogeneous mixture is achieved.

- Thermal Treatment: Transfer mixture to alumina crucible and heat in muffle furnace at 400°C for 2 hours with heating rate of 5°C/min.

- Washing: Cool naturally to room temperature, then disperse resulting powder in deionized water. Centrifuge at 8000 rpm for 5 minutes. Repeat washing cycle 3 times to remove residual salts.

- Drying: Dry washed precipitate at 80°C for 12 hours in vacuum oven.

- Annealing: Calcine final product at 350°C for 1 hour in air to crystallize.

Critical Parameters:

- Urea:Ni ratio controls nitrogen doping level (optimize between 1:4 to 1:8)

- Heating rate ≤5°C/min ensures uniform thermal decomposition

- Final annealing temperature critical for crystallinity without nitrogen loss

UPDI Synthesis and Composite Formation

Principle: Urea-functionalized perylene diimide forms covalently-linked polymers with enhanced stability compared to self-assembled PDI, maintaining strong built-in electric fields for charge separation while resisting disintegration under alkaline conditions [29] [33].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- UPDI Synthesis:

- Combine 500mg 3,4,9,10-perylenetetracarboxylic dianhydride (PTCDA) with 5g urea and 50mg Zn(OAc)â‚‚ catalyst

- Heat at 180°C for 4 hours under nitrogen atmosphere with continuous stirring

- Cool to room temperature, crush resulting solid, and wash with hot water to remove excess urea

- Dry at 100°C overnight to obtain crystalline UPDI

- Composite Formation:

- Prepare separate dispersions of 100mg N-NiO in 50mL ethanol and 200mg UPDI in 50mL acetone

- Sonicate both dispersions for 30 minutes to achieve complete dispersion

- Slowly add N-NiO suspension to UPDI suspension dropwise over 20 minutes with vigorous stirring

- Continue stirring for 6 hours at room temperature to facilitate electrostatic self-assembly

- Collect composite by centrifugation at 9000 rpm for 10 minutes

- Dry under vacuum at 80°C for 12 hours

Quality Control Check:

- Verify composite formation by zeta potential measurement (should show intermediate value between components)

- Check homogeneity by TEM with elemental mapping

- Confirm interfacial interaction by FTIR peak shifts

Photocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution Test Protocol

Principle: Under visible light irradiation, the NiO-UPDI composite should exhibit enhanced hydrogen evolution compared to individual components due to improved charge separation at the donor-acceptor interface [30].

Standard Procedure:

- Reaction Setup:

- Disperse 20mg NiO-UPDI composite in 100mL aqueous solution containing 10 vol% triethanolamine as sacrificial electron donor

- Load 1 wt% Pt cocatalyst via in-situ photodeposition using H₂PtCl₆

- Seal system and purge with Nâ‚‚ for 30 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen

Photocatalytic Reaction:

- Illuminate with 300W Xe lamp equipped with 420nm cutoff filter

- Maintain reaction temperature at 25°C using water cooling jacket

- Continuously stir at 300 rpm to maintain suspension

Gas Analysis:

- Collect 0.5mL gas sample from headspace at 1-hour intervals

- Analyze Hâ‚‚ content using gas chromatography with TCD detector

- Calculate evolution rate using calibration curve from standard Hâ‚‚ mixtures

Expected Performance Metrics:

- Reference system: ZnTCPP/C60-EDA achieves 113.5 μmol hâ»Â¹ Hâ‚‚ evolution [30]

- Quality composite should achieve at least 2x activity of physical mixture

- Linear production over 5 hours indicates stability

Quantitative Performance Data

Visualization of Mechanisms and Workflows

Charge Separation Mechanism in NiO-UPDI Composites

Experimental Workflow for Composite Synthesis

Research Reagent Solutions

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: What are the primary reasons for modifying g-C3N4 with non-metal elements like Boron (B), Phosphorus (P), and Sulfur (S)?

Modifying g-C3N4 with non-metal elements is a key strategy to overcome its inherent limitations as a photocatalyst, specifically to enhance charge separation, which is the core focus of this thesis. Pristine g-C3N4 suffers from rapid recombination of photogenerated electron-hole pairs, which wastes solar energy and limits its catalytic efficiency [34] [35]. Non-metal doping directly addresses this by:

- Altering the Electronic Band Structure: Doping can reduce the bandgap of g-C3N4, extending its light absorption into the visible region and creating more photogenerated charges [34] [36]. For instance, carbon self-doping can activate n→π* electronic transitions, significantly redshifting light absorption [36].

- Promoting Charge Separation: Dopant atoms introduce defects that can trap charge carriers, slowing down their recombination and prolonging their lifetime. This enhances the availability of electrons and holes for surface reactions like CO2 reduction or H2 production [34] [37].

- Improving Electrical Conductivity: Elements like sulfur can enhance electron transfer across the π-conjugated framework, facilitating the movement of charges to the catalyst surface [34] [36].

FAQ 2: During synthesis, my doped g-C3N4 sample shows lower photocatalytic activity than the pristine material. What could be the cause?

This is a common issue often traced to suboptimal synthesis parameters. The primary factors to investigate are:

- Dopant Concentration: Excessive doping can create recombination centers that trap electrons and holes, causing them to recombine instead of separating. This defeats the purpose of modification [35]. It is crucial to systematically optimize the precursor ratios.

- Polymerization Temperature and Time: The crystallinity and degree of condensation of g-C3N4 are highly sensitive to the calcination conditions [38]. Incomplete polymerization at low temperatures yields materials with many uncondensed amino groups, which act as recombination sites. Conversely, excessively high temperatures can degrade the structure. For melamine-based precursors, a temperature of around 520-550°C is often effective [38].

- Precursor Homogeneity: For doping methods involving a mixture of precursors (e.g., urea and thiourea), ensure a homogeneous mixture before calcination. Inhomogeneous mixing can lead to uneven doping and poorly defined material properties [39].

FAQ 3: How can I experimentally confirm that non-metal doping has successfully improved charge separation in my g-C3N4 samples?

You can verify enhanced charge separation through a combination of spectroscopic and photoelectrochemical characterizations:

- Photoluminescence (PL) Spectroscopy: A significant decrease in PL intensity for the doped sample compared to pristine g-C3N4 strongly indicates suppressed electron-hole recombination [35] [38].

- Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (TRPL): This technique measures the lifetime of photogenerated charges. A prolonged average lifetime in doped samples is direct evidence of more efficient charge separation [35].

- Photoelectrochemical Tests: Transient photocurrent response and Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) are highly effective. Enhanced photocurrent and a smaller arc radius in the EIS Nyquist plot for the doped sample signify improved charge separation and transfer efficiency [36] [35].

- UV-Vis Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy (DRS): This confirms the successful modulation of the optical properties, such as a redshift in the absorption edge, indicating a narrowed bandgap [34] [38].

Quantitative Performance Data of Non-Metal Doped g-C3N4

The following table summarizes the enhanced photocatalytic performance of non-metal doped g-C3N4 for various reactions, as reported in recent literature. The data clearly demonstrates the efficacy of doping in improving activity.

Table 1: Photocatalytic Performance of Non-Metal Doped g-C3N4.

| Dopant Element | Precursor(s) Used | Photocatalytic Reaction | Performance Metric | Reported Enhancement Over Pristine g-C3N4 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sulfur (S) | Thiourea | COâ‚‚ Reduction to CHâ‚„ | CHâ‚„ Production Rate | 7.87 nmol/(mL·gâ‚‘â‚ₜ·h) | [34] |

| Oxygen (O) | Hydrogen Peroxide / Melamine | CO₂ Reduction to CH₃OH | CH₃OH Production Rate | 5-fold increase (0.88 vs. 0.17 μmol/g/h) | [34] |

| Carbon (C) & N-Defects | Urea & Uric Acid | Hâ‚‚ Evolution | Hâ‚‚ Production Rate | Significant enhancement (Specific rate not provided) | [36] |

| Sulfur (S) | Melamine & Thiourea | Dye Degradation (Methylene Blue) | Sonophotocatalytic Degradation Efficiency | 4 times faster than photocatalysis alone | [38] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Synthesis of S-Doped g-C3N4 for Enhanced CO2 Reduction

This protocol is adapted from research focused on improving electron transfer for photocatalytic applications [34].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Thiourea (≥99%): Serves as the single source for both carbon nitride and sulfur dopant.

- Ethanol (96%): Used for washing the synthesized polymer to remove unreacted species.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Precursor Preparation: Place 10 g of thiourea in a covered alumina crucible.

- Thermal Polycondensation: Heat the crucible in a muffle furnace to 600 °C at a ramp rate of approximately 10 °C per minute. Maintain this temperature for 2 hours.

- Product Recovery: After the furnace cools to room temperature naturally, collect the resulting solid. This is the bulk S-doped g-C3N4.

- Post-Synthesis Treatment: Wash the solid multiple times with ethanol and double-distilled water to remove any unreacted precursors or by-products.

- Drying: Dry the final product in an oven at 60 °C for 12 hours to obtain the S-doped g-C3N4 as a yellow powder.

Protocol 2: Synthesis of Carbon Self-Doped and Nitrogen-Defective g-C3N4 Nanosheets

This advanced protocol creates a dual-modified material with synergistic effects for superior charge separation [36].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Urea: Primary precursor for g-C3N4.

- Uric Acid: Source of carbon for self-doping.

- Deionized Water: Solvent for the self-assembly process.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Supramolecular Pre-assembly: Dissolve 20 g of urea and 200 mg of uric acid in 30 mL of deionized water. Sonicate the mixture at 60 °C for 1 hour to ensure a homogeneous dispersion.

- Solvent Evaporation: Transfer the solution to an oil bath and stir at 120 °C for 3 hours to completely evaporate the solvent, forming a supramolecular urea-uric acid complex.

- Initial Polymerization: Place the dried complex in a covered crucible and heat at 550 °C for 2 hours in a muffle furnace. The resulting powder is the carbon self-doped g-C3N4 (denoted CNuu-550).

- Thermal Exfoliation (Introducing N-Defects): Further heat a portion of the CNuu-550 powder at 640 °C for 30 minutes. This step simultaneously exfoliates the bulk material into ultrathin nanosheets and introduces nitrogen defects, creating the final optimized photocatalyst (CNuu-640).

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents and their specific functions in the synthesis and modification of g-C3N4 photocatalysts.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Non-Metal Doping of g-C3N4.

| Reagent | Function in Doping and Modification | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Urea | A common, low-cost nitrogen-rich precursor for synthesizing pristine g-C3N4. Also used in mixtures for co-doping [34] [39]. | Pyrolysis releases gases that create a porous structure, which can enhance surface area [34]. |

| Thiourea | Primary precursor for introducing Sulfur (S) dopant atoms into the g-C3N4 matrix during thermal polymerization [34] [38]. | The S atoms typically substitute corner-site N atoms, modulating the electronic structure and improving electron transfer [34]. |

| Boric Acid | A common precursor for introducing Boron (B) dopant atoms into the g-C3N4 framework [34]. | Boron doping is reported to alter the band gap position and widen photon absorption, boosting charge transfer efficiency [34]. |

| Ammonium Dihydrogen Phosphate | A precursor used for incorporating Phosphorus (P) into g-C3N4 [34]. | The addition of red phosphorus to g-C3N4 has been shown to substantially enhance charge carrier separation [34]. |

| Uric Acid | Used as a carbon source for carbon self-doping. It enables supramolecular pre-assembly with urea, leading to an extended π-conjugated system [36]. | This impurity-free modification enhances light absorption and creates conductive interlayer networks for better charge mobility [36]. |

| Melamine | A standard precursor for producing g-C3N4 with higher crystallinity compared to urea [38]. | Higher calcination temperatures (e.g., >500°C) are often used with melamine to achieve improved crystallinity and a suitable band gap [38]. |

Cocatalyst Loading for Selective Charge Extraction and Reaction Acceleration

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental role of a cocatalyst in semiconductor photocatalysis?

Cocatalysts are substances added in small quantities to a catalyst to improve its activity, selectivity, or stability [40]. In semiconductor photocatalysis, their primary roles are multifold:

- Promoting Charge Separation: They provide trapping sites for photogenerated electrons and/or holes, facilitating their separation and mitigating recombination [40] [41].

- Accelerating Surface Reaction Kinetics: Cocatalysts offer active sites with refined electronic structures that lower the activation energy for surface redox reactions, such as hydrogen evolution (HER) and oxygen evolution (OER) [40] [42].

- Suppressing Photocorrosion: By timely consumption of photogenerated charges, particularly holes, cocatalysts can protect the underlying semiconductor photocatalyst from oxidative degradation [40] [42].

FAQ 2: Why is dual-cocatalyst loading often more effective than single-cocatalyst loading?

Loading dual cocatalysts, one for reduction (e.g., for H₂ evolution) and one for oxidation (e.g., for O₂ evolution), can significantly enhance activity for overall water splitting [41]. This strategy effectively separates the reduction and oxidation active sites, which not only accelerates the respective half-reactions but also suppresses the reverse reaction of H₂ and O₂ recombining into water [42]. For instance, a system using Rh/Cr₂O₃ as a reduction cocatalyst and Co₃O₄ as an oxidation cocatalyst achieved a high solar-to-chemical conversion efficiency [40].

FAQ 3: My photocatalyst shows good charge separation but low overall activity. What could be the issue?

This often indicates a bottleneck in the surface reaction kinetics. While charge separation is necessary, the photogenerated carriers must be efficiently utilized in the redox reactions. This issue can be addressed by:

- Ensuring Cocatalyst Suitability: Verify that the loaded cocatalyst has appropriate energy band alignment with the semiconductor to extract the specific charge carrier (electron or hole) required for your target reaction [40].

- Optimizing Cocatalyst Dispersion and Loading: The cocatalyst should be highly dispersed to provide a maximum number of active sites. However, excessive loading can block light absorption by the semiconductor and/or act as charge recombination centers [42].

FAQ 4: How can I determine if my cocatalyst is effectively extracting electrons or holes?

The charge transfer pathway is governed by the energy band alignment at the semiconductor-cocatalyst interface [40].

- For electron-extracting cocatalysts (e.g., Pt, Ni), the Fermi level of the metal should be lower than the conduction band of the semiconductor to form a Schottky junction that promotes electron transfer from the semiconductor to the cocatalyst [40].

- For hole-extracting cocatalysts (e.g., IrO₂, Co₃O₄), an Ohmic junction or a staggered band alignment that favors hole migration from the semiconductor valence band to the cocatalyst is required [40]. Advanced characterization techniques like in-situ electron spin resonance (ESR) can directly track the flow of holes to molecular cocatalysts [43].

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem 1: Rapid Deactivation of Photocatalyst During Reaction

- Potential Cause: Photocorrosion, where the semiconductor itself is oxidized by the accumulated photogenerated holes.

- Solution:

- Load a suitable oxidation cocatalyst (e.g., IrOâ‚‚, RuOâ‚‚, CoOx) to rapidly consume holes [42] [41].

- For H₂ evolution cocatalysts like Pt, consider embedding them within a protective shell (e.g., Cr₂O₃) to prevent contact with oxygen and suppress the reverse reaction, thereby enhancing stability [42].

Problem 2: Low Quantum Efficiency Despite High Light Absorption

- Potential Cause: Severe bulk or surface recombination of photogenerated electron-hole pairs.

- Solution:

- Load Dual Cocatalysts: Implement separate reduction and oxidation cocatalysts to simultaneously extract electrons and holes, preventing their recombination [41].

- Optimize Interface Engineering: Employ a loading method that ensures an intimate interface (e.g., in-situ photodeposition or impregnation) between the cocatalyst and semiconductor to minimize interfacial charge transfer resistance [40] [42].

- Consider Homogeneous Cocatalysts: In some cases, molecular co-catalysts like trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) can act as efficient hole shuttles, maximizing contact areas with reactants and significantly boosting Hâ‚‚ evolution [43].

Problem 3: Inconsistent Cocatalyst Deposition and Poor Dispersion