Spatial Bias in High-Throughput Screening: A Complete Guide to Detection, Correction, and Data Quality Assurance

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on mitigating spatial bias in high-throughput wellplate experiments.

Spatial Bias in High-Throughput Screening: A Complete Guide to Detection, Correction, and Data Quality Assurance

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on mitigating spatial bias in high-throughput wellplate experiments. It explores the foundational concepts and significant impact of spatial bias on false positive and negative rates in drug discovery. The content details advanced methodological approaches for bias correction, including both additive and multiplicative models, and offers practical troubleshooting strategies for optimizing assay quality. Through a comparative analysis of validation techniques and performance metrics, the article equips scientists with the knowledge to implement robust spatial bias correction protocols, ultimately enhancing data reliability and the efficiency of hit identification in pharmaceutical research.

Understanding Spatial Bias: The Hidden Threat to High-Throughput Screening Data Quality

Defining Spatial Bias and Its Impact on Hit Selection in HTS

FAQs on Spatial Bias in High-Throughput Screening

What is spatial bias in high-throughput screening (HTS)?

Spatial bias is a systematic error that affects experimental high-throughput screens, producing over or under-estimation of true signals in specific well locations, rows, or columns within microtiter plates [1]. This non-random error negatively impacts the hit selection process by increasing false positive and false negative rates [1]. The bias can follow either an additive model (where a fixed value is added or subtracted from measurements) or a multiplicative model (where measurements are multiplied by a factor) [1] [2].

Multiple technical and procedural factors can introduce spatial bias into screening data [1]:

- Reagent evaporation leading to edge effects

- Cell decay over time

- Liquid handling errors and pipette malfunctioning

- Variation in incubation time

- Time drift during measurement of different wells or plates

- Reader effects from detection instruments

How does spatial bias impact hit selection?

Spatial bias significantly compromises data quality during hit identification [1]:

- Increased false positives: Biased measurements can be falsely identified as hits

- Increased false negatives: True active compounds may be missed

- Reduced reliability: Biased data decreases confidence in screening results

- Increased costs: Following false leads extends the drug discovery timeline

Spatial bias produces recognizable patterns, most commonly as row or column effects, with particularly pronounced impact on plate edges [1].

How can I detect spatial bias in my screening data?

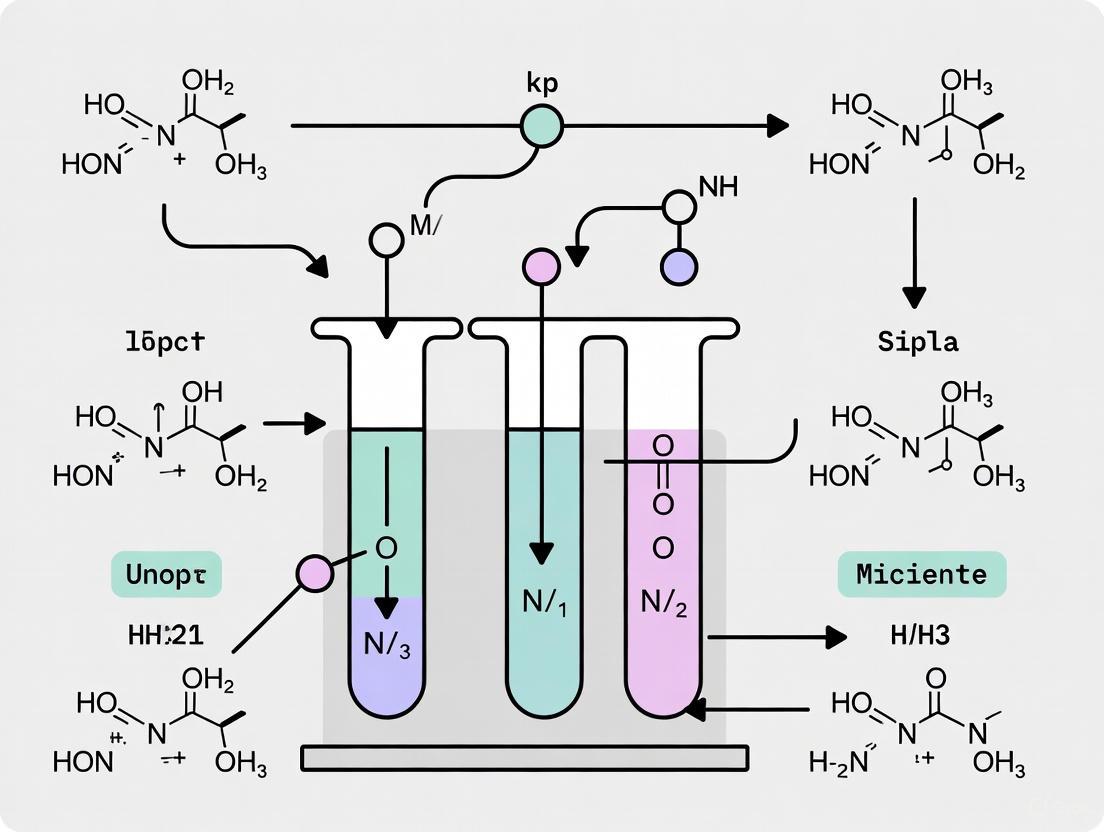

Detection involves both visual and statistical approaches. The following workflow outlines a comprehensive detection and correction process:

What methods are available for correcting spatial bias?

Several statistical methods can effectively correct spatial bias, with performance comparisons shown in the table below [1]:

| Method | Bias Type Addressed | Key Principle | Performance Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| No Correction | N/A | Uses raw, uncorrected data | Baseline for comparison |

| B-score | Additive | Uses median polish to remove row/column effects | Effective for additive bias only |

| Well Correction | Assay-specific | Removes systematic error from biased well locations | Addresses location-specific effects |

| PMP with Robust Z-scores | Additive & Multiplicative | Combines plate-specific correction with assay normalization | Highest hit detection rate, lowest false positives/negatives [1] |

The PMP algorithm with robust Z-scores consistently outperforms other methods, achieving higher true positive rates and lower combined false positive/negative counts across varying hit percentages and bias magnitudes [1].

Are there specialized tools for implementing bias correction?

Yes, the AssayCorrector program, implemented in R and available on CRAN, provides comprehensive spatial bias correction capabilities [2]. This tool can handle:

- Both additive and multiplicative spatial bias models

- Assay-specific and plate-specific bias patterns

- Data from multiple HTS technologies including homogeneous, cell-based, and gene expression screens [3]

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Spatial Bias Detection and Correction

Purpose: To identify and correct both additive and multiplicative spatial bias in HTS data.

Materials Needed:

- Raw HTS data in plate format

- Statistical software (R recommended)

- AssayCorrector package (available on CRAN)

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Format screening data to distinguish plates, rows, columns, and well measurements.

- Visual Assessment: Generate heatmaps for each plate to identify obvious spatial patterns.

- Statistical Testing: Apply both Mann-Whitney U test and Kolmogorov-Smirnov two-sample test with significance threshold α=0.01 or α=0.05 [1].

- Bias Classification: Determine whether bias follows additive or multiplicative model based on pattern characteristics.

- Bias Correction: Apply appropriate PMP algorithm (additive or multiplicative) followed by robust Z-score normalization [1].

- Validation: Compare pre- and post-correction hit lists to ensure biological signals are preserved while technical artifacts are removed.

Protocol 2: Performance Validation of Bias Correction Methods

Purpose: To evaluate the effectiveness of spatial bias correction in maintaining true hits while reducing false discoveries.

Procedure:

- Hit Selection: Apply μp − 3σp threshold to corrected data, where μp and σp are the mean and standard deviation per plate [1].

- Performance Metrics Calculation:

- True Positive Rate: Percentage of known active compounds correctly identified

- False Positive Count: Number of inactive compounds incorrectly classified as hits

- False Negative Count: Number of active compounds missed

- Comparative Analysis: Compare metrics across different correction methods (B-score, Well Correction, PMP with robust Z-scores).

- Optimization: Adjust significance thresholds based on desired balance between sensitivity and specificity.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Tool | Function in HTS Experiments | Application in Bias Mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| Micro-well Plates (96, 384, 1536-well) | Miniaturized format for compound screening | Understanding plate architecture is essential for identifying edge effects and spatial patterns [1] |

| Control Compounds | Reference points for assay performance | Help distinguish true biological effects from technical bias across plate locations |

| AssayCorrector Software | Statistical correction of spatial bias | Implements PMP algorithms and robust Z-scores for comprehensive bias removal [2] [3] |

| Robust Z-score Normalization | Data normalization method | Reduces assay-specific bias across multiple plates in a screen [1] |

| B-score Algorithm | Traditional spatial bias correction | Provides benchmark for comparing performance of newer methods [1] |

Advanced Bias Modeling

Recent research has developed more sophisticated models that account for interactions between row and column biases. These advanced approaches recognize that measurements in wells at the intersection of biased rows and columns require specialized correction based on the nature of bias interactions [3]. The field continues to evolve with:

- Two novel additive spatial bias models

- Two novel multiplicative spatial bias models

- Integrated procedures for detecting and removing complex bias patterns

These advancements are particularly valuable for next-generation screening technologies where traditional correction methods may be insufficient for maintaining data quality in hit selection [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Correcting Spatial Bias in HTS Data

Spatial bias is a systematic error that negatively impacts data quality and hit selection in high-throughput screening (HTS), leading to increased false positive and false negative rates [1]. This guide will help you identify and correct the most common forms of spatial bias.

Key Symptoms of Spatial Bias:

- Row or column effects, particularly on plate edges [1]

- Over or under-estimation of true signals in specific well locations [1]

- Increased well-to-well variability across the microplate [4]

- Unacceptably high plate rejection rates in screening runs [5]

Step-by-Step Diagnostic Protocol:

- Visual Inspection: Begin with visual assessment of raw data heatmaps for systematic patterns across rows, columns, or specific regions (especially plate peripheries) [1].

- Statistical Testing: Apply statistical methods like the Mann-Whitney U test and Kolmogorov-Smirnov two-sample test to objectively identify bias patterns. A significance threshold of α = 0.01 or α = 0.05 is recommended [1].

- Determine Bias Type: Classify the bias as either:

- Select Correction Method: Choose a correction algorithm based on the identified bias type. Research shows that using methods specifically designed for the bias type (additive or multiplicative PMP algorithms followed by robust Z-scores) yields the highest hit detection rate and the lowest false positive and false negative counts [1] [2].

Performance Comparison of Bias Correction Methods: The table below summarizes the effectiveness of different correction methods from simulation studies, showing true positive rates and total false results at 1% hit percentage and 1.8 SD bias magnitude [1].

| Correction Method | True Positive Rate (%) | Total False Positives & Negatives per Assay |

|---|---|---|

| No Correction | ~40% | ~1800 |

| B-score | ~65% | ~1100 |

| Well Correction | ~72% | ~850 |

| Additive/Multiplicative PMP + Robust Z-scores (α=0.05) | ~88% | ~450 |

Guide 2: Resolving Edge Effect in Cell-Based Assays

Edge effect causes significant variation in cell growth and assay measurements in the outermost wells of a microplate, primarily due to evaporation and subsequent concentration of media components [4].

Primary Causes:

- Evaporation: Water and media evaporate fastest from perimeter wells, leading to volume loss and concentration of salts and metabolites, which can alter cell physiology [4].

- Incubation Conditions: Low humidity (below 95%) in COâ‚‚ incubators dramatically increases evaporation [4].

- Direct Incubation: Placing newly seeded plates directly into a 37°C CO₂ incubator can cause an uneven cell distribution in peripheral wells [5].

Solutions and Best Practices:

- Optimize Incubation Protocol:

- Pre-incubation: A simple, effective technique is to pre-incubate newly seeded plates at room temperature in ambient air before transferring them to the 37°C CO₂ incubator. This has been shown to significantly reduce edge effect [5].

- Minimize Disturbance: Limit the frequency of removing plates from the incubator for inspection and avoid unnecessary door openings to maintain stable humidity and temperature [4].

- Use Specialized Microplates: Consider using microplates with an evaporation buffer zone, such as a moat filled with sterile water or 0.5% agarose surrounding the outer wells. These can reduce overall plate evaporation to less than 2% after seven days of incubation, compared to over 8% in standard plates [4].

- Maintain High Humidity: Always ensure incubators are set to at least 95% humidity. Evaporation is nearly four times higher at 80% humidity than at 90% [4].

Guide 3: Minimizing Bias from Liquid Handling

The method and timing of liquid handling, particularly for controls and standards, are critical sources of assay bias [6].

Common Sources of Liquid Handling Bias:

- Adding standards and controls at a different time than test samples [6].

- Using pre-made control/standard plates that are older and have been exposed to different conditions [6].

- Using different liquid handling equipment for samples versus controls [6].

- Poor placement of controls and standards, making them susceptible to edge effects [6].

Strategies for Mitigation:

- Ideal Workflow: Cherry-pick test samples and the top dose of the standard, then serialize both together in the same run. This ensures they are processed identically and simultaneously [6].

- Judicious Placement: Avoid placing controls and standards only in edge columns (e.g., columns 1 and 24). Use the flexibility of acoustic dispensers to distribute them across the plate in a serpentine pattern to avoid region-specific biases [6].

- Careful Management of Pre-made Plates: If using pre-made plates with controls and standards, be aware that they may introduce bias if they are made weeks in advance and stored differently from freshly serialized test samples [6].

- Rigorous Tracking: Use a Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) to track the handling and addition of controls and standards, providing a full audit trail [6].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common sources of spatial bias in HTS? The most prevalent sources include evaporation (leading to edge effects), errors in liquid handling (e.g., pipette malfunction), reagent evaporation, cell decay, variation in incubation time, time drift between measurements, and reader effects [1] [4].

Q2: How can I tell if my assay data is affected by spatial bias? You can identify spatial bias by plotting your data in heatmaps to look for clear spatial patterns, such as entire rows or columns with consistently higher or lower signals, or systematic effects on the plate edges. Statistical tests are also used for objective detection [1].

Q3: My cell-based assay has strong edge effects. What is the first thing I should check? Verify the humidity level in your CO₂ incubator and ensure it is maintained at a minimum of 95%. Also, review how often the incubator door is opened, as this disrupts the environment. Consider adopting a room-temperature pre-incubation step before placing plates in the 37°C incubator [4] [5].

Q4: What is the difference between additive and multiplicative spatial bias? Additive bias involves a constant value being added to or subtracted from the measurements in a specific pattern. Multiplicative bias involves the measurements in a specific pattern being multiplied by a factor, which often occurs in HTS/HCS technologies and requires different statistical methods for correction [1] [2].

Q5: Why is the placement of controls and standards so important? Controls and standards are used to validate that your assay is performing consistently. If they are only placed on the edge of the plate, they themselves become affected by edge effects, and you can no longer use them as a reliable benchmark for the test samples in the interior of the plate [6].

Data Presentation

Quantitative Impact of Spatial Bias and Correction Methods

Table 1: Evaporation Rates in Different Microplate Types This table compares the evaporation rates of various 96-well microplate formats after 4 and 7 days of incubation under simulated laboratory conditions (incubator opened 7 times daily). Data demonstrates the effectiveness of specialized plates with evaporation buffers [4].

| Microplate Type | Evaporation After 4 Days | Evaporation After 7 Days |

|---|---|---|

| Standard 96-well plate | ~5% | >8% |

| Plate with evaporation buffer (water) | <1% | ~2% |

| Plate with evaporation buffer (0.5% agarose) | <1% | ~2% |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Mitigating Spatial Bias Essential materials and computational tools used to identify and correct spatial bias in high-throughput experiments.

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Nunc Edge Plate (or similar) | Microplate with a perimeter buffer zone (moat) to reduce evaporation and edge effects [4]. |

| Controls and Standards | Well-characterized substances that provide a 0% and 100% effect range to measure assay consistency and calculate Z' factor [6]. |

| AssayCorrector Program | An R package available on CRAN for detecting and removing both additive and multiplicative spatial bias [2]. |

| Robust Z-score | A normalization method that uses the median and median absolute deviation, making it less sensitive to outliers from hits [1]. |

| B-score | A established plate-specific correction method that uses robust regression to remove row and column effects [1]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Pre-incubation Method to Reduce Edge Effect in Cell-Based Assays

This simple and inexpensive protocol significantly reduces edge effect by ensuring even cell distribution in peripheral wells [5].

- Seed the microplate with your cell suspension as per standard procedure.

- Instead of placing the plate directly into the COâ‚‚ incubator, leave the newly seeded plate at room temperature in ambient air.

- Allow the plate to pre-incubate at room temperature for a period sufficient for the cells to settle evenly. (The original study does not specify an exact duration, but this should be determined empirically).

- After pre-incubation, carefully transfer the plate to the humidified (≥95%) incubator at 37°C and 5% CO₂ for the remainder of the culture period.

- Minimize disturbances by limiting door openings and external inspections during incubation [4].

Protocol 2: A Normalization Workflow for Correcting Edge Effect in Colony Growth Analyses

This protocol is adapted from studies using high-density pinning arrays and provides a method to compensate for growth rate discrepancies across the plate, reducing false positives and negatives [7].

- Experimental Setup: Pin microbial cells (e.g., fission yeast) from a source plate onto solid agar assay plates using a robotic system (e.g., ROTOR HDA).

- Image Acquisition: Incubate the plates and capture images of colony growth at regular intervals (e.g., every two hours) using a dedicated scanner (e.g., PhenoBooth).

- Data Extraction: Use image analysis software (e.g., PhenoSuite) to generate quantitative colony size values for every position on the plate over time.

- Calculate Growth Rates: For each colony position, plot colony size against time and determine the growth rate during key linear phases (e.g., early and late growth).

- Apply Normalization: Create a normalization table based on the growth rates of control strains (e.g., wild-type) at different positions. Use this to normalize the growth data of test strains, compensating for location-based growth advantages or disadvantages.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in the bias identification and correction process.

In high-throughput screening (HTS), which allows researchers to rapidly conduct millions of chemical, genetic, or pharmacological experiments, spatial bias is a major challenge that threatens data integrity [1]. This systematic error manifests as over- or under-estimation of true signals in specific locations on a multi-well plate (e.g., in specific rows, columns, or particularly on plate edges) and is a significant source of false positives and false negatives [1].

False positives occur when an inactive compound is incorrectly identified as a "hit," while false negatives occur when a truly active compound is missed [8]. The consequences are profound: false positives waste resources on follow-up studies, while false negatives can cause the irretrievable loss of a promising therapeutic candidate [9]. This guide will help you identify, quantify, and correct for spatial bias to improve the quality of your HTS data.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is spatial bias and how does it lead to false results?

Spatial bias is a systematic error that causes measurements from certain locations on a multi-well plate to be consistently higher or lower than their true value [1]. Common sources include:

- Reagent evaporation: Often affects outer wells, leading to false negatives due to decreased reaction efficiency [1].

- Liquid handling errors: Malfunctioning pipettes can create column-specific patterns, causing both false positives and false negatives [1].

- Cell decay or variation in incubation time: Can create row or column-specific effects [1].

When bias affects one area of the plate more than another, it distorts the statistical distribution of the data. This miscalculation of the mean and standard deviation used for hit identification causes you to either set the bar for a hit too low (increasing false positives) or too high (increasing false negatives) [1].

2. Are all spatial biases the same?

No, and understanding the difference is critical for effective correction. Spatial bias can be classified as additive or multiplicative [1] [10].

- Additive Bias: A fixed value is added or subtracted from the well measurements, regardless of the signal's true strength.

- Multiplicative Bias: The true signal is multiplied by a factor, meaning the bias's effect is proportional to the signal itself.

Using the wrong model for correction can leave residual bias in your data. Furthermore, bias can be assay-specific (appearing across all plates in an assay) or plate-specific (unique to a single plate) [1].

3. What is the Z'-factor and how is it affected by bias?

The Z'-factor is a widely used metric for assessing the quality and robustness of an HTS assay. It measures the separation between the positive (max signal) and negative (min signal) controls, taking into account the variability of both signals [9].

Formula: Z' = 1 - [ 3*(σₚ + σₙ) / |μₚ - μₙ| ] ...where μₚ and σₚ are the mean and standard deviation of the positive control, and μₙ and σₙ are those of the negative control [9].

Spatial bias artificially inflates the standard deviations (σ) of your controls, which lowers the Z'-factor. A low Z'-factor reduces the assay's ability to reliably distinguish true hits from background noise, thereby increasing both false positive and false negative rates [9].

4. What are the best methods to correct for spatial bias?

Effective correction requires a two-step process:

- Detection: Use statistical tests and visualization to identify the presence and type of bias.

- Correction: Apply a statistical method that matches the identified bias model.

- For plate-specific additive bias, the B-score method is a traditional approach [1].

- For a more comprehensive method that can handle both additive and multiplicative plate-specific biases, the Partial Mean Polish (PMP) algorithm has been shown to be highly effective [1].

- For assay-specific bias (bias affecting the same well locations across all plates), the Well Correction method or using robust Z-scores is recommended [1].

A study comparing methods found that using additive/multiplicative PMP followed by robust Z-scores yielded the highest hit detection rate and the lowest false positive and false negative count [1].

Quantifying the Impact of Bias

The following table summarizes data from a simulation study that demonstrates how spatial bias degrades HTS performance. The study compared different correction methods against a "No Correction" baseline, showing that proper correction is essential [1].

Table 1: Performance of Bias Correction Methods in HTS Simulations

| Correction Method | True Positive Rate (Hit Detection) | Total False Positives & Negatives (per assay) | Key Principle |

|---|---|---|---|

| No Correction | Lowest | Highest (Baseline) | Highlights the risk of uncorrected data. |

| B-score [1] | Moderate | Moderate | Corrects for plate-specific additive spatial bias. |

| Well Correction [1] | Moderate | Moderate | Corrects for assay-specific bias (consistent well errors). |

| PMP + Robust Z-score [1] | Highest | Lowest | Corrects for both additive/multiplicative plate-specific and assay-specific biases. |

Note: Simulation conditions assumed a bias magnitude of 1.8 SD and a hit rate of 1%. The PMP (Partial Mean Polish) method combined with robust Z-scores consistently outperformed other methods [1].

Table 2: Estimated Prevalence of Spatial Bias in HTS (Based on ChemBank Data)

| Bias Type | Probability of Occurrence | Typical Manifestation |

|---|---|---|

| Assay-Specific Bias | 29% of well locations [1] | A consistent pattern of error across all plates in a single assay. |

| Plate-Specific Additive Bias | 41.8% of plates [1] | A fixed value added to specific rows/columns on a single plate. |

| Plate-Specific Multiplicative Bias | 30.8% of plates [1] | A proportional scaling of signals on a single plate. |

Experimental Protocols for Bias Identification and Correction

Protocol 1: Detecting Spatial Bias in Your HTS Dataset

This workflow helps you visualize and statistically confirm the presence of spatial bias.

Materials:

- Raw data from your HTS run, including plate layouts and well coordinates.

- Statistical software (e.g., R, Python) or specialized HTS analysis tools.

Procedure:

- Visual Inspection: Create a heatmap of the raw measurements from a single plate, with wells arranged in their actual row-column layout. Look for clear patterns, such as gradients from one edge to another or specific rows/columns with consistently high or low signals.

- Plate Uniformity Assessment: Run a dedicated plate uniformity study over multiple days using "Max," "Min," and "Mid" signal controls arranged in an interleaved format across the plate. This helps characterize signal variability and separation [11].

- Statistical Testing: Apply statistical tests to determine if the observed patterns are significant.

- Use the Mann-Whitney U test and Kolmogorov-Smirnov two-sample test to compare the distribution of signals from the edge wells versus the inner wells. A significant result (e.g., p-value < 0.05) indicates spatial bias [1].

- Advanced methods can further distinguish between additive and multiplicative bias models [10].

Protocol 2: Correcting for Spatial Bias Using the PMP Method

This protocol outlines the steps for a robust correction that handles both additive and multiplicative biases [1] [10].

Materials:

- HTS data organized by plate and well location.

- Software capable of running the PMP algorithm (e.g., the

AssayCorrectorprogram in R) [10].

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Organize your data so that each plate is a matrix of values with rows and columns.

- Bias Model Selection: For each plate, statistically determine whether an additive or multiplicative model is more appropriate. This can be done by comparing the residuals of both models and selecting the one with the best fit [1] [10].

- Apply Partial Mean Polish (PMP):

- For Additive Bias: The algorithm iteratively removes the median from each row and each column until the values stabilize, effectively "polishing" away the row and column effects.

- For Multiplicative Bias: The algorithm works on the log-transformed data, applying the same median polish, and then transforms the data back.

- Apply Assay-Wide Correction: After plate-specific biases are removed with PMP, calculate robust Z-scores (using the median and median absolute deviation) for the entire assay to correct for any persistent assay-specific bias [1].

- Re-evaluate Hit Selection: Use the corrected data and a defined threshold (e.g., μp - 3σp per plate) to select hits. You should now have a list with a lower rate of false positives and false negatives.

The following diagram illustrates this multi-step correction workflow:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for HTS Assay Validation

| Item | Function in HTS/Bias Mitigation |

|---|---|

| "Max" Signal Control | Provides the maximum assay signal (e.g., uninhibited enzyme activity, full agonist). Used with "Min" to calculate the Z'-factor and define the dynamic range [11]. |

| "Min" Signal Control | Provides the background or minimum assay signal (e.g., fully inhibited enzyme, vehicle control). Critical for establishing the signal window [11]. |

| "Mid" Signal Control | A control that generates a signal midway between Max and Min (e.g., ECâ‚…â‚€ concentration of an agonist). Helps assess variability across the assay's dynamic range [11]. |

| DMSO Compatibility-Tested Reagents | All assay reagents must be validated for stability and performance at the final DMSO concentration used for compound delivery to avoid solvent-induced artifacts [11]. |

| Stability-Validated Reagents | Reagents with known stability under storage and assay conditions are essential for ensuring consistent performance across long screening campaigns and avoiding time-drift bias [11]. |

| D,L-Sulforaphane Glutathione-d5 | D,L-Sulforaphane Glutathione-d5, MF:C16H28N4O7S3, MW:489.6 g/mol |

| Caerulein, desulfated tfa | Caerulein, desulfated tfa, MF:C60H74F3N13O20S, MW:1386.4 g/mol |

Visualizing the Data Analysis Pathway

The following diagram outlines the logical pathway for analyzing HTS data, from raw measurements to a finalized hit list, highlighting key decision points for bias correction.

Spatial bias presents a significant challenge in High-Throughput Screening (HTS), potentially leading to increased false positive and false negative rates during hit identification. Analysis of experimental small molecule assays from the ChemBank database reveals that screening data are widely affected by both assay-specific and plate-specific spatial biases. Implementing appropriate statistical correction methods is essential for improving data quality and ensuring reliable hit selection in drug discovery campaigns [1].

Table 1: Prevalence and Impact of Spatial Bias in HTS

| Aspect | Findings from ChemBank Data Analysis |

|---|---|

| Assays Affected | Widespread assay-specific and plate-specific spatial biases observed [1]. |

| Common Bias Models | Additive bias model, Multiplicative bias model [1]. |

| Primary Sources | Reagent evaporation, cell decay, liquid handling errors, pipette malfunction, incubation time variation, reader effects [1]. |

| Impact on Hit Selection | Can lead to increased false positive and false negative rates [1]. |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Bias Correction Methods

| Correction Method | Key Principle | Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|

| No Correction | - | Lowest hit detection rate; highest false positive/negative count [1]. |

| B-score | Plate-specific correction using median polish [1]. | Moderate performance [1]. |

| Well Correction | Assay-specific correction for systematic error from biased well locations [1]. | Moderate performance [1]. |

| PMP with Robust Z-scores | Corrects both plate-specific (additive/multiplicative) and assay-specific biases [1]. | Highest hit detection rate and lowest false positive/negative count [1]. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: What are the most common types of spatial bias encountered in HTS wellplate experiments?

Spatial bias in HTS typically manifests in two primary forms, often with distinct underlying models:

- Assay-Specific Bias: A consistent bias pattern that appears across all plates within a given assay. This requires a global correction strategy applied to the entire dataset [1].

- Plate-Specific Bias: A bias pattern unique to an individual plate. This can be further categorized:

- Additive Bias: A constant value is added to or subtracted from measurements in affected wells. It can be generated from a normal distribution ~N(0, C), where C is the bias magnitude [1].

- Multiplicative Bias: Measurements in affected wells are scaled by a factor, generated from a normal distribution ~N(1, C) [1].

These biases often originate from physical experimental conditions, including reagent evaporation (often causing edge effects), cell decay, liquid handling errors, pipette malfunctions, and variation in incubation or measurement times [1].

FAQ 2: How can I quickly check my HTS data for the presence of significant spatial bias?

A powerful method for identifying spatial patterns is Periodogram Analysis based on the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT). This technique decomposes the spatial data into its frequency components to detect periodic patterns that are difficult to see visually [12].

Protocol: Automatic Spatial Error Detection using DFT

- Prepare Data Array: For a single plate, format the measurement data into a matrix corresponding to the well locations (e.g., 16x24 for a 384-well plate). Subtract the plate average from each value so data represents deviations from the mean [12].

- Compute Periodogram: Calculate the DFT and then the periodogram. The periodogram shows the energy contained in each spatial frequency component. The formula for the periodogram at frequency i is:

periodogram_i = |dft_i - mean(dft)|² / Nwhere N is the number of frequencies [12]. - Statistical Test for Non-Randomness:

- Generate a distribution of maximum frequency-component amplitudes from 100 periodograms of random, non-correlated data.

- Compare the largest amplitude frequency component from your experimental plate's periodogram to this random distribution.

- A low p-value (e.g., < 0.05) indicates that the plate contains spatially correlated signal and is not random. Plates with p-values below 0.05 typically have noticeable systematic error [12].

This automated detection can be implemented in software like VisTa to provide real-time quality control during a screening campaign [12].

FAQ 3: My data shows a clear edge effect. What is the best method to correct for this before hit selection?

Edge effects are a common form of plate-specific spatial bias. The most effective strategy involves a two-stage correction process that addresses both plate-specific and assay-specific biases.

Protocol: Comprehensive Bias Correction Workflow

Apply Plate-Specific Correction:

- Determine Bias Model: Use statistical tests (e.g., Mann-Whitney U, Kolmogorov-Smirnov) on the plate data to decide if the bias is additive or multiplicative. Our cited study used significance thresholds of α=0.01 or α=0.05 for these tests [1].

- Execute PMP Algorithm: Apply the appropriate Plate Model Pattern (PMP) algorithm.

- This step removes the systematic row and column effects from each plate.

Apply Assay-Specific Correction:

- Calculate Robust Z-scores for the PMP-corrected data across the entire assay. This normalization step accounts for global, assay-wide biases affecting specific well locations [1].

Hit Identification:

- After the dual correction, hits can be selected using a per-plate threshold, such as

μ_p - 3σ_p, whereμ_pandσ_pare the mean and standard deviation of the corrected measurements in platep[1].

- After the dual correction, hits can be selected using a per-plate threshold, such as

Simulation studies show that this combined approach (PMP + Robust Z-scores) yields a higher true positive rate and a lower total count of false positives and false negatives compared to B-score or Well Correction methods alone [1].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

The following workflow integrates the key methodologies for diagnosing and correcting spatial bias in HTS data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item / Solution | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| ChemBank Database | A public repository of small-molecule screens providing access to thousands of experimental assays for analysis and method validation [1]. |

| High-Throughput Microplates | Miniaturized assay platforms (e.g., 384, 1536-well plates) enabling rapid screening of thousands of compounds. The 384-well format (16x24) is widely used [1]. |

| Robust Z-Score Normalization | A statistical method for assay-specific bias correction. It is robust to outliers and standardizes data across an entire assay [1]. |

| PMP (Plate Model Pattern) Algorithms | Computational methods, including both additive and multiplicative models, designed to correct for plate-specific spatial biases by modeling row and column effects [1]. |

| Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) | A signal processing algorithm used for periodogram analysis. It identifies and quantifies spatially correlated errors in array data by decomposing patterns into frequency components [12]. |

| VisTa Software | An example software tool that incorporates DFT for identifying, quantifying, and visualizing spatial patterns in microplate data for quality control [12]. |

| N-acetyl semax amidate | N-acetyl semax amidate, MF:C39H54N10O10S, MW:855.0 g/mol |

| Ephrin-A2-selective ysa-peptide | Ephrin-A2-selective ysa-peptide, MF:C59H86N12O19S2, MW:1331.5 g/mol |

The Economic and Timelines Impact of Uncorrected Bias on Drug Discovery Pipelines

Troubleshooting Guide: Spatial Bias in High-Throughput Screening

Common Problems and Solutions

Q: Our HTS campaigns are generating too many false positives, leading to costly follow-up studies on inactive compounds. What could be wrong?

A: This is a classic symptom of uncorrected spatial bias. Systematic errors from sources like reagent evaporation, liquid handling errors, or plate edge effects can create patterns that mimic true biological activity [1]. Implement statistical bias correction methods like B-score or the PMP algorithm with robust Z-scores, which have been shown to significantly reduce false positive rates [1].

Q: Why do our hit compounds frequently fail to show activity in confirmatory assays?

A: Uncorrected spatial bias can also increase false negatives—true active compounds whose signals are masked by systematic error [1]. This leads to promising candidates being overlooked early in the pipeline. Combining randomization in plate design with appropriate normalization methods improves reliability and accuracy of hit identification [13].

Q: How can we determine whether we're dealing with additive or multiplicative spatial bias in our screens?

A: Different HTS technologies generate different types of bias. Traditional correction methods often assume only additive bias, but multiplicative bias is also common [3]. Use specialized statistical procedures that can detect and correct both types, such as those implemented in the AssayCorrector program, which accounts for different types of bias interactions at row-column intersections [3].

Economic Impact Data

Table 1: Quantitative Impacts of Uncorrected Spatial Bias on Drug Discovery

| Impact Metric | Without Proper Bias Correction | With Effective Bias Correction |

|---|---|---|

| Hit Detection Rate | Decreases significantly as bias magnitude increases [1] | PMP algorithm with robust Z-scores yields highest detection rate [1] |

| False Positive/False Negative Count | Increases with bias magnitude [1] | Lowest across all methods when using advanced correction [1] |

| Financial Value in Late-Stage Development | Lower efficiency in predicting successful candidates [14] | Generates $763M-$1,365M additional value across six therapeutic areas [14] |

| True Positive Rate in Predictive Models | As low as 15% with biased data [14] | Up to 60% with debiased models [14] |

Experimental Protocol: Identifying and Correcting Spatial Bias

Methodology for Comprehensive Bias Detection and Correction

Plate Design and Setup

- Incorporate both positive and negative controls distributed across plates

- Include random placement of compounds when possible to identify spatial effects [13]

- Use appropriate replication to enable statistical detection of bias patterns

Data Quality Assessment

- Calculate quality metrics (Z-factor, SSMD) to measure differentiation between controls [15]

- Generate heat maps of plate measurements to visualize spatial patterns

- Test for both row and column effects using statistical tests

Bias Type Identification

Bias Correction Implementation

Hit Selection

HTS Bias Correction Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Bias Mitigation

| Tool/Reagent | Function in Bias Mitigation | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Microtiter Plates | Testing vessel for HTS experiments | Available in 96, 384, 1536, or 3456-well formats; proper plate design crucial for identifying spatial effects [15] |

| Positive/Negative Controls | Quality assessment and normalization reference | Essential for calculating Z-factor, SSMD; should be distributed across plates to detect spatial patterns [15] |

| AssayCorrector Program | Detects and corrects additive/multiplicative spatial bias | Implemented in R; handles data from multiple HTS technologies [3] |

| SIGHTS Excel Add-In | Conducts statistical analyses and diagnostic graphs | Enables extensive normalization and formal statistical testing [13] |

| Robust Z-score Normalization | Corrects for assay-specific spatial bias | Less sensitive to outliers than traditional Z-score; used after plate-specific correction [1] |

| B-score Method | Corrects for plate-specific spatial bias | Traditional row-column normalization; effective for certain bias types [1] |

| BDP R6G amine hydrochloride | BDP R6G amine hydrochloride, MF:C24H30BClF2N4O, MW:474.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| DL-Aspartic acid hemimagnesium salt | DL-Aspartic acid hemimagnesium salt, MF:C4H5MgNO4, MW:155.39 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Methodologies

Quantitative HTS (qHTS) Recent advances include quantitative HTS, which generates full concentration-response relationships for each compound, enabling assessment of structure-activity relationships and providing more reliable data through curve fitting [15].

Machine Learning for Bias Mitigation Novel approaches using deep reinforcement learning frameworks can mitigate unwanted biases while maintaining strong classification performance, achieving clinically effective screening while improving outcome fairness [16].

Impact of Uncorrected Bias

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: How much can proper bias correction improve our drug discovery efficiency?

A: Studies show that debiased models can improve true positive rates from 15% to 60% while maintaining strong classification performance [14]. The financial impact is substantial, with estimates showing debiased models generating $763 million to $1.365 billion in additional value across six major therapeutic areas due to more efficient late-stage development [14].

Q: Are some HTS technologies more prone to specific types of bias?

A: Yes, different technologies exhibit different bias patterns. Research analyzing ChemBank data has shown that homogeneous, microorganism, cell-based, and gene expression HTS technologies each have characteristic bias profiles, as do high-content screening technologies measuring area, intensity, and cell counts [3]. Understanding your specific technology's bias tendencies is crucial for selecting appropriate correction methods.

Q: What's the most overlooked aspect of spatial bias correction in HTS?

A: The interaction between different types of bias is frequently overlooked. Traditional methods assume simple additive or multiplicative models, but measurements in wells at the intersection of biased rows and columns depend on the nature of interaction between the involved biases [3]. Newer models accounting for these interactions provide more accurate correction.

Advanced Correction Methodologies: From B-Score to AI-Driven Solutions

High-throughput screening (HTS) technologies are powerful tools that allow researchers to quickly conduct millions of tests to identify relevant modifier genes, proteins, or compounds involved in specific biological pathways [17]. However, data generated by these technologies are prone to spatial bias across the multiwell plates used in experiments [3]. This systematic error can significantly impact measurement accuracy, leading to false positives or missed discoveries during the early stages of research projects [18].

Spatial bias manifests as consistent patterns of error across specific regions of well plates, often following row, column, or edge effects. Traditional correction methods like B-Score and Well Correction have been developed specifically to identify and mitigate these biases, ensuring that biological signals detected in screens reflect true activity rather than artifacts of plate positioning [3].

Understanding B-Score Normalization

What is B-Score Correction?

B-Score is a robust normalization method designed to correct spatial bias in high-throughput screening data. It operates on the principle that most features in a primary screen are inactive, allowing for robust estimates of row and column systematic-error effects [18].

How B-Score Works

The B-Score method uses a two-way median polish procedure to remove row and column effects from the raw data. Unlike mean-based approaches, it employs medians, making it more resistant to outliers that might be present in the data. This is particularly valuable in screens where strong active compounds could skew mean-based corrections.

Key steps in B-Score calculation:

- Row median correction: Calculate and remove median values for each row

- Column median correction: Calculate and remove median values for each column

- Iterative polishing: Repeat the process until residuals stabilize

- Median absolute deviation (MAD) scaling: Normalize the residuals using MAD instead of standard deviation

When to Use B-Score

B-Score performs optimally in standard primary screens where the majority of tested features (typically 90% or more) are expected to be inactive [18]. This method is particularly effective for:

- Primary compound library screens

- Genome-wide RNAi screens with expected low hit rates

- Phenotypic screens with most features showing neutral effects

Well Correction Methods

Control-Plate Regression (CPR)

Control-Plates containing the same feature in all wells provide well-by-well estimates of systematic error, which can then be removed from treatment plates [18]. The robust CPR method uses this approach to effectively handle screens containing large proportions of active features, where traditional methods might remove biological signal.

Additive and Multiplicative Bias Models

Traditional correction methods typically assume either simple additive or multiplicative spatial bias models [3]. However, these models don't always accurately correct measurements in wells located at the intersection of rows and columns affected by spatial bias, as the corrections don't account for bias interactions.

Novel spatial bias models now include:

- Additive bias models with different types of bias interactions

- Multiplicative bias models accounting for complex spatial patterns

- Hybrid approaches that combine elements of both

Experimental Protocols for Bias Correction

Protocol 1: B-Score Implementation

Materials Required:

- Raw measurement data from HTS experiment

- Statistical software with median polish functionality

- Plate layout metadata

Methodology:

- Data Preparation: Organize data by plate, preserving well position information

- Median Polish: Apply two-way median polish to remove row and column effects

- Residual Calculation: Compute residuals after median polish

- MAD Scaling: Normalize residuals using median absolute deviation

- B-Score Output: The final B-Scores represent bias-corrected values

Protocol 2: Control-Plate Regression Normalization

Materials Required:

- Experimental plates with test compounds

- Control plates with identical features in all wells

- AssayCorrector program (available in R) or equivalent software [3]

Methodology:

- Control Plate Processing: Measure systematic error patterns from control plates

- Pattern Mapping: Characterize spatial bias across well positions

- Regression Modeling: Develop correction models based on control plate data

- Bias Removal: Apply correction factors to experimental plates

- Validation: Verify correction effectiveness using control compounds

Troubleshooting Guide

Common Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Over-correction of signal | Too many active features in screen | Switch to CPR method; Use control plates for reference [18] |

| Incomplete bias removal | Complex bias interactions | Implement advanced models accounting for bias interactions [3] |

| Poor performance with high hit rates | Traditional methods assume mostly inactive features | Use quantitative HTS (qHTS) with multiple concentrations [17] |

| Edge effects persisting | Evaporation or temperature gradients | Use blank wells at plate edges; Implement spatial smoothing |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: How do I choose between B-Score and Well Correction methods? A: B-Score is ideal for primary screens with low hit rates, while Well Correction methods like CPR are better for screens with many active features or when control plates are available [18].

Q: Can these methods be applied to different HTS technologies? A: Yes, correction procedures can be applied to homogeneous, microorganism, cell-based, and gene expression HTS technologies, as well as high-content screening technologies [3].

Q: What software tools are available for implementing these corrections? A: The AssayCorrector program, implemented in R and available on CRAN, contains implementations of these methods [3]. Other options include specialized HTS analysis packages in Python and commercial software like Knime.

Q: How much can spatial bias affect my results? A: Systematic error can significantly lower measurement accuracy, leading to following up inactive features and failing to follow up active features [18]. In extreme cases, bias can completely obscure true biological signals.

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Materials for Spatial Bias Correction

| Reagent/Material | Function in Bias Correction |

|---|---|

| Control Plates | Well-by-well estimation of systematic error patterns [18] |

| Blank Wells | Assessment of background noise and positional effects |

| Reference Compounds | Validation of correction method performance |

| Standardized Assay Reagents | Minimize introduced variability from reagent sources |

| Quality Control Compounds | Monitor assay performance across plate positions |

Visualization of Correction Workflows

B-Score Correction Process

Spatial Bias Correction Decision Framework

Traditional correction methods like B-Score and Well Correction remain fundamental tools for mitigating spatial bias in high-throughput wellplate experiments. While B-Score offers robust performance for standard primary screens, Control-Plate Regression and advanced bias models address more complex scenarios with higher hit rates or interacting bias patterns [18] [3].

Proper implementation of these methods requires understanding their underlying assumptions, appropriate application contexts, and validation procedures. By systematically addressing spatial bias, researchers can significantly improve the accuracy and reliability of their high-throughput screening data, leading to more confident identification of true biological effects in drug development and basic research.

Implementing Additive and Multiplicative PMP Algorithms for Plate-Specific Bias

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is spatial bias and why is it a problem in High-Throughput Screening (HTS)? Spatial bias is a systematic error that negatively impacts the hit selection process in HTS. Various sources include reagent evaporation, cell decay, errors in liquid handling, pipette malfunctioning, variation in incubation time, time drift in measurement, and reader effects. This bias often appears as row or column effects, particularly on plate edges, and can lead to both increased false positive and false negative rates during hit identification [19].

What is the difference between additive and multiplicative spatial bias? Additive bias (often called the "mean error") measures how well the mean forecast and mean observation correspond, indicating over or under-forecast tendency. Multiplicative bias is better suited for data with a lower bound at zero (e.g., wind speed, significant wave height) or for causes of error that are multiplicative in nature. Measurements in wells at the intersection of affected rows and columns depend on the nature of interaction between the biases [10] [20].

When should I use the PMP algorithm for bias correction? The Partial Mean Polish (PMP) algorithm should be used when you need to correct for plate-specific spatial bias in high-throughput screening data. Research shows that using additive and multiplicative PMP algorithms together with robust Z-scores yields the highest hit detection rate and the lowest false positive and false negative total hit count compared to other methods like B-score and Well Correction [19].

My data still shows bias after correction. What could be wrong? First, verify whether you have correctly identified the bias type (additive or multiplicative) in your data. Second, ensure you are applying the appropriate statistical tests (Mann-Whitney U test and Kolmogorov-Smirnov two-sample test) with suitable significance thresholds (typically α=0.01 or α=0.05). Also, check for assay-specific biases that might require additional correction with robust Z-scores [19].

Can these algorithms handle different well plate formats? Yes, the methodology can be applied to various micro-well plate formats including 96, 384, 1536, or 3456-well plates. The algorithms are designed to work with the most widely-used plate formats in screening databases like ChemBank [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High False Positive/Negative Rates After Correction

Symptoms

- Hit detection rates remain unsatisfactory even after spatial bias correction

- Continued presence of spatial patterns in residual plots

- Inconsistent results across replicate plates

Possible Causes and Solutions

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Incorrect bias model selection | Test both additive and multiplicative models using statistical tests (Mann-Whitney U and Kolmogorov-Smirnov) to determine which better fits your data [19]. |

| Unaddressed assay-specific bias | Apply robust Z-score normalization in addition to plate-specific PMP correction to account for biases affecting entire assays [19]. |

| Insufficient iteration cycles | Increase the number of algorithm iterations, particularly for datasets with strong spatial patterns. Research indicates multiple iterations significantly improve correction [19]. |

Problem: Algorithm Convergence Issues

Symptoms

- Excessive processing time without completion

- Oscillating correction values between iterations

- Failure to produce stable results

Resolution Steps

- Reduce dataset size: Process fewer plates simultaneously to isolate problematic plates

- Adjust significance thresholds: Modify α values (0.01 or 0.05) for statistical tests to improve stability [19]

- Check input data quality: Ensure raw measurements don't contain extreme outliers that could disrupt the algorithm

- Verify plate formatting: Confirm well positions are correctly mapped to the expected plate geometry

Problem: Inconsistent Correction Across Plates

Symptoms

- Variable correction effectiveness across different plates in the same assay

- Some plates show over-correction while others show under-correction

- Unpredictable results when applying the same parameters to similar datasets

Troubleshooting Approach

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Quantitative Performance Comparison of Bias Correction Methods

Table 1: Performance comparison of bias correction methods with fixed bias magnitude (1.8 SD) and varying hit percentages [19]

| Hit Percentage | No Correction | B-score | Well Correction | PMP (α=0.01) | PMP (α=0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5% | 42% | 65% | 71% | 89% | 88% |

| 1.0% | 38% | 62% | 68% | 86% | 85% |

| 2.0% | 35% | 58% | 64% | 83% | 82% |

| 3.0% | 32% | 55% | 61% | 80% | 79% |

| 5.0% | 28% | 51% | 56% | 76% | 75% |

True positive rates shown for each method across varying hit percentages

Table 2: Performance with fixed hit percentage (1%) and varying bias magnitudes [19]

| Bias Magnitude | No Correction | B-score | Well Correction | PMP (α=0.01) | PMP (α=0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.6 SD | 45% | 70% | 75% | 92% | 91% |

| 1.2 SD | 41% | 66% | 72% | 89% | 88% |

| 1.8 SD | 38% | 62% | 68% | 86% | 85% |

| 2.4 SD | 34% | 58% | 64% | 82% | 81% |

| 3.0 SD | 30% | 54% | 59% | 78% | 77% |

True positive rates decrease as bias magnitude increases, but PMP methods maintain superior performance

Detailed Methodology for PMP Algorithm Implementation

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

Data Preparation and Quality Control

- Format data according to well plate specifications (96, 384, 1536-well formats)

- Identify and flag empty wells, control wells, and potential outliers

- Log-transform data if variance appears to increase with mean

Bias Type Identification

- Apply both Mann-Whitney U test and Kolmogorov-Smirnov two-sample test

- Use significance thresholds of α=0.01 or α=0.05 for hypothesis testing

- Determine whether additive or multiplicative model better fits each plate

Plate-Specific Bias Correction

- For additive bias: Apply additive PMP algorithm using the model: Measurement = Overall Mean + Row Effect + Column Effect + Residual [19]

- For multiplicative bias: Apply multiplicative PMP algorithm using the model: Measurement = Overall Mean × Row Effect × Column Effect × Residual [19]

- Iterate until convergence criteria are met (typically 5-10 iterations)

Assay-Specific Bias Correction

- Apply robust Z-score normalization to address biases affecting entire assays

- Use median and median absolute deviation for increased outlier resistance

Hit Identification

- Apply μp − 3σp threshold for each plate, where μp and σp are the mean and standard deviation of corrected measurements in plate p

- Validate hits through visual inspection of spatial patterns in corrected data

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key research reagent solutions for spatial bias correction experiments

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| AssayCorrector R Package | Implements additive and multiplicative PMP algorithms | Available on CRAN; includes statistical tests for bias type identification [10] |

| ChemBank Database | Source of experimental small molecule screening data | Provides 4,767 assays across HTS, HCS, and SMM technologies for method validation [19] |

| Robust Z-score Normalization | Corrects for assay-specific spatial biases | Uses median and MAD instead of mean and SD for outlier resistance [19] |

| B-score Method | Traditional plate-specific correction method | Useful for comparative performance assessment against PMP algorithms [19] |

| Well Correction Method | Assay-specific bias correction technique | Serves as baseline for evaluating PMP performance [19] |

| Statistical Test Suite | Mann-Whitney U and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests | Determines appropriate bias model with significance thresholds α=0.01 or 0.05 [19] |

| Isohexenyl-glutaconyl-CoA | Isohexenyl-glutaconyl-CoA, MF:C32H49N7O19P3S-, MW:960.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (S)-3-hydroxydodecanedioyl-CoA | (S)-3-hydroxydodecanedioyl-CoA, MF:C33H56N7O20P3S, MW:995.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Implementation Notes

Parameter Optimization Guidelines

- For high signal-to-noise data: Use α=0.01 for more stringent bias detection

- For low signal-to-noise data: Use α=0.05 to increase sensitivity for bias detection

- Optimal iterations: 5-10 cycles typically sufficient for convergence

- Edge effect handling: PMP algorithms specifically address common edge biases

Validation Framework

- Compare pre- and post-correction spatial patterns using heat maps

- Quantify reduction in row and column effect variances

- Verify biological consistency of identified hits

- Assess reproducibility across technical replicates

A Step-by-Step Guide to Robust Z-Score Normalization for Assay-Wide Bias

Why is correcting for spatial bias critical in High-Throughput Screening (HTS)?

Spatial bias is a major challenge in HTS, leading to increased false positives and false negatives. This systematic error can arise from various sources, including reagent evaporation, pipetting errors, cell decay, and plate reader effects [19]. If uncorrected, these biases can cause researchers to waste significant resources pursuing incorrect "hits" or overlooking truly active compounds, thereby increasing the cost and time required for drug discovery [19].

How does Robust Z-Score Normalization mitigate assay-wide spatial bias?

While plate-specific correction methods like B-score address biases within a single plate, assay-wide bias affects the same well locations across all plates in an experiment [19]. Robust Z-score normalization is a statistical technique used to correct for this assay-wide bias. It transforms the data from different plates to a common scale, allowing for valid cross-plate comparisons and hit identification.

The formula for Robust Z-score is: Robust Z-score = (X - Median) / MAD Where:

- X is the raw measurement from a well.

- Median is the median of all measurements on a plate (a robust measure of center).

- MAD is the Median Absolute Deviation, a robust measure of data spread [19].

This method is "robust" because it uses the median and MAD instead of the mean and standard deviation, making it less sensitive to outliers (which, in HTS, could be your true hits) [19].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the difference between additive and multiplicative spatial bias, and why does it matter for correction?

Spatial bias in HTS can follow different mathematical models, and using the wrong correction can leave residual error [19] [3].

- Additive Bias: The bias adds a fixed amount to the true signal, regardless of the signal's strength. This might be caused by a constant background signal or a baseline shift. Correction methods like B-score assume an additive model [19].

- Multiplicative Bias: The bias scales the true signal by a factor. This is often related to percentage effects, such as variations in incubation time or reagent concentration that proportionally affect the measurement [19].

Using a method that can identify and correct for both types of bias, such as the PMP (Plate Model Pattern) algorithm followed by robust Z-scores, is essential for comprehensive data quality improvement [19].

My hit rate seems abnormally high/low after normalization. What could be wrong?

An unexpected hit rate often points to an issue in the normalization workflow. The table below outlines common causes and solutions.

| Problem Description | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High false positive rate | Applying standard Z-score (using mean/SD) instead of Robust Z-score, allowing outliers to inflate the variance [21] [22]. | Switch to Robust Z-score normalization, which uses the median and MAD. |

| Persistent row/column patterns | Correcting only assay-wide bias but neglecting plate-specific spatial bias [19]. | Implement a two-step correction: First, apply a plate-specific method (e.g., additive/multiplicative PMP), then apply assay-wide Robust Z-score [19]. |

| Inconsistent results across assays | Using a single bias model (e.g., additive) when your data contains a mix of bias types [3]. | Use a statistical procedure that first identifies the dominant bias pattern (additive, multiplicative, or interactive) in each plate before correction [3]. |

How do I validate that my bias correction method is working effectively?

Validation should include both qualitative and quantitative assessments.

- Visual Inspection: Create heatmaps of raw and corrected data for individual plates. Successful correction should eliminate obvious spatial patterns like edge effects or gradients, resulting in a "random" speckle pattern [19].

- Performance Metrics: Use a positive control or spiked compounds with known activity. A good correction method should increase the true positive rate and decrease the total count of false positives and false negatives [19].

- Simulation Testing: As done in the foundational research, you can generate synthetic HTS data with known hits and bias rates to benchmark your correction pipeline's performance against other methods like B-score or Well Correction [19].

Should I use standard Z-score or Robust Z-score for my HTS data?

For HTS data, Robust Z-score is almost always the better choice. The following table compares the two methods.

| Feature | Standard Z-Score | Robust Z-Score |

|---|---|---|

| Central Tendency | Uses Mean (μ) | Uses Median |

| Data Spread | Uses Standard Deviation (σ) | Uses Median Absolute Deviation (MAD) |

| Sensitivity to Outliers | High - a single strong hit can drastically inflate σ, masking other hits [22]. | Low - the median and MAD are resistant to extreme values, providing a more stable normalization [19]. |

| Best For | Data with a normal distribution and no outliers. | HTS data, which is typically contaminated with outliers (true hits) and non-normal distributions [19]. |

Experimental Protocols

Step-by-Step Protocol for Implementing Robust Z-Score Normalization

This protocol details the calculation and application of robust Z-score normalization for correcting assay-wide bias.

Step 1: Pre-processing and Plate Layout Annotation

- Gather raw measurement data from all plates in the assay.

- Annotate the data with well positions (e.g., A01, B01), plate identifiers, and the type of content in each well (e.g., compound, positive control, negative control).

Step 2: Calculate Plate-Level Median and MAD

- For each plate p in the assay, calculate the median of all well measurements.

- Calculate the MAD for the plate:

- Find the absolute deviation of each well's measurement from the plate median:

Absolute Deviation = |X_i - Median_p| - The MAD is the median of these absolute deviations.

- Find the absolute deviation of each well's measurement from the plate median:

- A scaling factor (typically 1.4826) is often multiplied by the MAD to make it a consistent estimator for the standard deviation of a normal distribution:

Scaled MAD = MAD * 1.4826.

Step 3: Compute Robust Z-Score for Each Well

- For each well i on plate p, apply the robust Z-score formula:

Robust Z-score_i = (X_i - Median_p) / (Scaled MAD_p)

Step 4: Hit Identification Across the Assay

- The normalized robust Z-scores from all plates are now on a comparable scale.

- Apply a uniform threshold for hit selection across the entire assay. A common threshold is Robust Z-score ≤ -3 or ≥ 3, indicating a measurement that is 3 robust standard deviations away from the plate median [19].

The following workflow diagram illustrates this multi-step process and its role in a comprehensive spatial bias mitigation strategy.

Workflow for Comprehensive Spatial Bias Mitigation

This diagram outlines the logical sequence for a full spatial bias correction pipeline, positioning Robust Z-score normalization as the final step for addressing assay-wide effects.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key materials and tools referenced in this guide for implementing robust spatial bias correction.

| Item | Function in the Context of Bias Correction |

|---|---|

| Micro-well Plates | The physical platform for HTS experiments (e.g., 384, 1536-well). Spatial bias is directly tied to well location on these plates [19]. |

| Control Compounds | Known active and inactive compounds sparsely distributed across plates. They are critical for validating that correction methods maintain true signals while removing noise. |

| AssayCorrector (R package) | A specialized software tool mentioned in research that implements advanced procedures for detecting and removing both additive and multiplicative spatial biases [3]. |

| Statistical Software (R/Python) | Essential for implementing the computational steps of robust Z-score normalization, PMP algorithms, and generating diagnostic plots like heatmaps [19] [21]. |

| Positive/Negative Controls | Used for per-plate normalization and quality control. They help anchor the median and MAD calculations, ensuring the robust Z-score is biologically calibrated. |

| Acetyl sh-Heptapeptide-1 | Acetyl sh-Heptapeptide-1, CAS:1356845-72-1, MF:C36H49N7O18, MW:867.8 g/mol |

| (11Z)-Tetradecenoyl-CoA | (11Z)-Tetradecenoyl-CoA, MF:C35H56N7O17P3S-4, MW:971.8 g/mol |

Integrating Machine Learning for Automated Bias Pattern Recognition

Welcome to the Technical Support Center

This resource provides troubleshooting guides and frequently asked questions (FAQs) for researchers implementing machine learning (ML) to automate the detection and correction of spatial bias in high-throughput wellplate experiments. The guidance is framed within the broader thesis of making spatial bias mitigation more scalable and accurate through computational approaches.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is spatial bias in the context of high-throughput screening (HTS)? Spatial bias refers to systematic errors in data measurements that are dependent on the physical location of a well within a multi-well plate. These biases can follow either additive (e.g., a baseline signal shift) or multiplicative (e.g., a signal strength proportional to the true value) models. Traditional methods often fail to correct biases at the intersection of affected rows and columns, necessitating more advanced models that account for bias interactions [3].

FAQ 2: Why should I use machine learning for bias mitigation instead of traditional statistical methods? Traditional correction methods often assume simple bias models. Machine learning, particularly deep learning, excels at identifying complex, non-linear patterns in data without needing pre-defined models. This allows ML to uncover subtle spatial bias patterns that might be missed by conventional approaches, leading to more robust corrections and better generalization on new, unbiased data [23].

FAQ 3: What are the main types of bias that ML models can help address? In data analysis, two primary biases are:

- Background Bias: The model makes inferences based on contextual or background cues rather than the primary subject of interest [24].

- Foreground Bias: The model relies on the appearance of the subject itself, which can lead to spurious correlations if the training data is skewed [24]. ML debiasing techniques aim to reduce the model's dependency on these unwanted correlations.

FAQ 4: What is a typical high-level workflow for an ML-based debiasing project? A common and effective strategy involves two key steps [23]:

- Bias Identification: Using techniques like anomaly detection to identify which samples in your dataset are "bias-aligned" (follow the spurious correlation) and which are "bias-conflicting."

- Bias Mitigation: Using the identified samples to guide the debiasing process, for example, by upsampling bias-conflicting samples or using adversarial learning to make the model ignore the biased features.

FAQ 5: How can I check if my color palettes for data visualization are accessible? Adhering to accessibility standards like WCAG ensures your charts are readable by a wider audience. For graphics and chart elements, a minimum 3:1 contrast ratio with neighboring elements is recommended. All text should achieve a minimum 4.5:1 contrast ratio with its background [25]. You can use online tools like the WCAG Color Contrast Checker to validate your color choices.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Model Performance is Poor on New Wellplate Data

Problem: Your ML model, which performed well on your training data, shows a significant drop in accuracy when applied to new experimental data from a different wellplate run.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Overfitting to Spurious Correlations The model has learned incidental noise or spatial artifacts specific to your training plates instead of the true biological signal.

- Solution: Implement Adversarial Debiasing Use a framework like ALBAR (Adversarial Learning approach to mitigate Biases in Action Recognition), which employs an adversarial loss to force the model to ignore bias-aligned features. This encourages the model to learn more generalized features that are robust across different plates [24].

- Solution: Treat Bias as an Anomaly Frame the problem as an anomaly detection task. Since most of your data may be bias-aligned, use a method like a One-Class Support Vector Machine (OCSVM) to identify bias-conflicting samples as outliers. You can then upsample these samples during training to create a more balanced and robust model [23].

Issue 2: Ineffective Correction at Row-Column Intersections

Problem: After applying standard bias correction, wells located at the intersections of biased rows and columns still show significant errors.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Simple Additive/Multiplicative Model Failure Traditional models do not account for the interaction between row and column biases.

- Solution: Use Advanced Interaction Models

Implement novel spatial bias models that are specifically designed to account for different types of interactions between row and column effects. Tools like the

AssayCorrectorR package, available on CRAN, incorporate such advanced models for more accurate correction at these critical intersections [3].

Issue 3: Lack of Labeled Bias Data for Supervised Learning

Problem: You want to use ML to correct bias, but you do not have pre-existing labels that define which samples in your dataset are biased.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Unsupervised Learning Scenario This is a common and realistic scenario in many labs.

- Solution: Adopt Unsupervised Debiasing Techniques Focus on unsupervised debiasing methods. The two-step method of bias identification via anomaly detection followed by mitigation (e.g., data augmentation and upsampling) is a powerful state-of-the-art approach that does not require prior bias knowledge [23].

Protocol 1: Two-Step Unsupervised Debiasing via Anomaly Detection

This protocol is adapted from state-of-the-art research for scenarios where explicit bias labels are unavailable [23].

Step 1: Bias Identification with OCSVM

- Objective: Identify bias-conflicting samples in your wellplate data.

- Method: a. Train a preliminary (biased) model on your wellplate data. b. Extract feature representations from an intermediate layer of this model for all samples. c. Train a One-Class Support Vector Machine (OCSVM) on the feature representations of samples that are easily classified (assumed to be bias-aligned). d. Use the trained OCSVM to predict outliers. These outliers are your identified bias-conflicting samples.

Step 2: Model Debiasing via Data Augmentation

- Objective: Retrain a model that is robust to the identified biases.

- Method: a. Upsampling: Increase the representation of the identified bias-conflicting samples in your training dataset. b. Augmentation: Apply domain-specific data augmentation techniques (e.g., synthetic spatial distortions, signal variations) to the bias-conflicting samples to further reinforce their patterns. c. Retraining: Retrain your ML model on the newly balanced and augmented dataset.

Quantitative Data on Debiasing Performance

The following table summarizes the performance improvements achieved by a modern debiasing method on standard benchmark datasets. These values illustrate the potential gain in accuracy from implementing such techniques.

Table 1: Performance of Anomaly Detection-Based Debiasing Method [23]

| Dataset Type | Scenario | Average Accuracy (Before) | Average Accuracy (After) | Conflicting Accuracy (After) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synthetic | Controlled Bias | ~65% | ~85% | ~82% |

| Real-World (BAR) | Complex, Unstructured Bias | ~70% | ~80% | ~78% |

| Real-World (BFFHQ) | Complex, Unstructured Bias | ~72% | ~85% | ~81% |

- Average Accuracy: Measures overall model performance across all classes.

- Conflicting Accuracy: Focuses specifically on model performance on the challenging bias-conflicting samples.

Workflow Visualization

Diagram: Unsupervised Debiasing Workflow

This diagram illustrates the two-step protocol for mitigating bias without pre-existing labels.

Diagram: Spatial Bias Models in HTS

This diagram outlines the logical relationship between different types of spatial bias and the corresponding correction approaches.

The Scientist's Toolkit