Sol-Gel Synthesis of Metal Oxide Photocatalysts: A Comprehensive Guide from Fundamentals to Advanced Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the sol-gel method for synthesizing advanced metal oxide photocatalysts, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Sol-Gel Synthesis of Metal Oxide Photocatalysts: A Comprehensive Guide from Fundamentals to Advanced Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the sol-gel method for synthesizing advanced metal oxide photocatalysts, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of sol-gel chemistry and its advantages for creating tailored nanostructures. The scope extends to practical synthesis protocols, characterization techniques, and optimization strategies to overcome common challenges like electron-hole recombination and limited visible-light absorption. By presenting validation frameworks and comparative performance analysis of various metal oxide systems, including TiO2, ZnO, and their composites, this guide serves as a critical resource for developing efficient photocatalytic platforms for environmental remediation, drug discovery, and clinical applications.

Sol-Gel Chemistry and Metal Oxide Photocatalysis: Fundamental Principles and Design Opportunities

Fundamental Chemical Principles

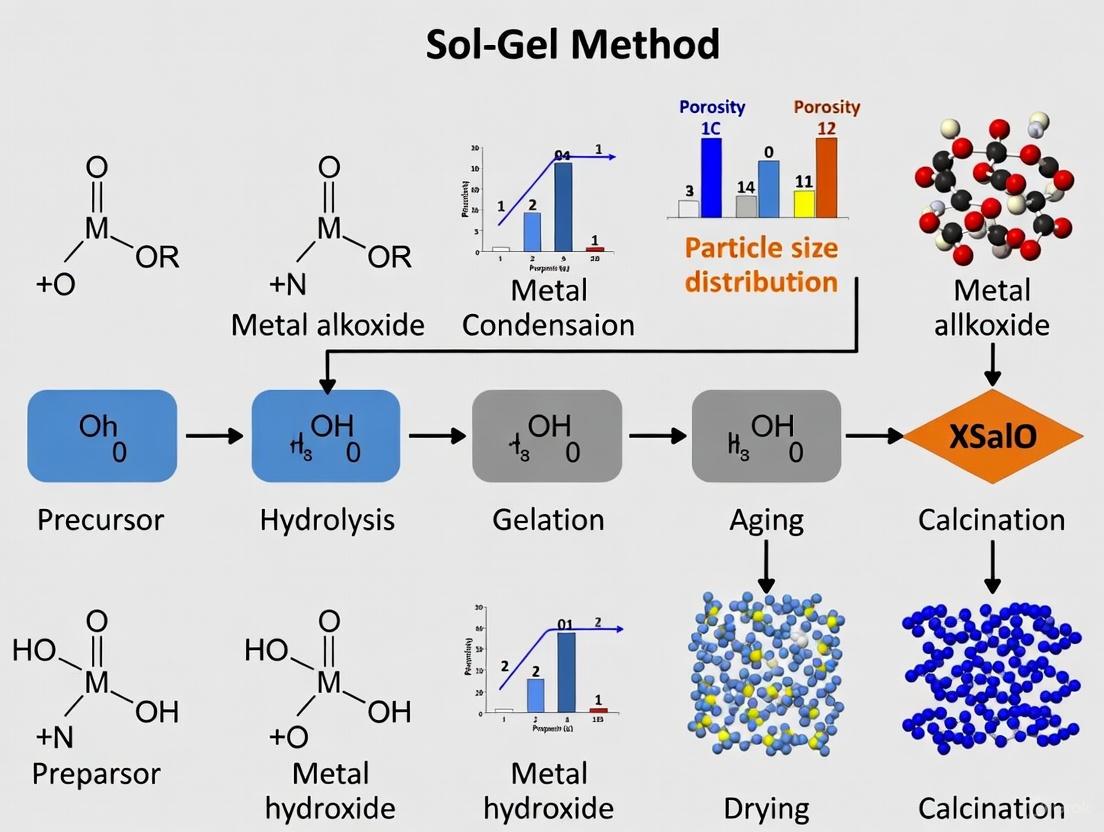

Sol-gel processing is a versatile wet-chemical method for fabricating metal oxide networks through a series of controlled hydrolysis and polycondensation reactions starting from molecular precursors [1] [2]. This bottom-up approach enables the transformation of a colloidal solution (sol) into an integrated solid network (gel) spanning various dimensionalities from discrete nanoparticles to continuous monolithic structures [2] [3].

The process fundamentally involves connecting metal centers through oxo (M-O-M) or hydroxo (M-OH-M) bridges, generating metal-oxo or metal-hydroxo polymers in solution [2]. The most commonly employed precursors are metal alkoxides, with tetraethylorthosilicate (TEOS) and titanium tetraisopropoxide (TTiP) being frequently used for silica and titania systems, respectively [1] [4].

Hydrolysis Mechanisms

Hydrolysis initiates the sol-gel process through nucleophilic attack of water molecules on metal alkoxide precursors. This reaction replaces alkoxide groups (OR) with hydroxyl groups (OH) [2] [5]:

General Hydrolysis Reaction: M(OR)₄ + H₂O → M(OR)₃(OH) + ROH

The rate and extent of hydrolysis are critically influenced by pH, water-to-precursor ratio, and the electronegativity of the metal center [5]. More electrophilic metal centers (e.g., Ti, Zn) undergo hydrolysis more readily than silicon, often necessitating modified precursors or reaction controls for multicomponent systems [4] [6].

Polycondensation Mechanisms

Following hydrolysis, polycondensation reactions create the metal oxide network through the formation of oxo-bridges, liberating water (aqua) or alcohol (alcoxo) as byproducts [1] [2]:

Water-Forming Condensation: M–OH + HO–M → M–O–M + H₂O

Alcohol-Forming Condensation: M–OR + HO–M → M–O–M + ROH

These condensation reactions proceed through SNâ‚‚-type nucleophilic substitution mechanisms, where the rate depends on the steric hindrance around the metal center and the catalyst employed [5]. The growing polymers eventually cross-link to form an extensive three-dimensional network, marking the gel point where the viscosity increases sharply and the system solidifies [1].

Table 1: Key Reactions in Sol-Gel Processing

| Reaction Type | General Equation | Products | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrolysis | M(OR)₄ + nH₂O → M(OR)₄₋ₙ(OH)ₙ + nROH | Partially hydrolyzed precursor, alcohol | pH, water concentration, catalyst type, metal electronegativity |

| Water-Forming Condensation | M–OH + HO–M → M–O–M + H₂O | Oxo-bridge, water | pH, temperature, metal reactivity |

| Alcohol-Forming Condensation | M–OR + HO–M → M–O–M + ROH | Oxo-bridge, alcohol | Steric hindrance of alkoxide group, catalyst |

Figure 1: Reaction pathway of sol-gel processing showing hydrolysis and polycondensation stages with byproduct formation.

Experimental Protocols for Photocatalyst Synthesis

TiOâ‚‚ Photocatalyst via Organic Sol-Gel Route

This protocol produces high-purity TiOâ‚‚ thin films with controlled crystallinity, optimized for photocatalytic applications [4].

Research Reagent Solutions:

Table 2: Essential Reagents for TiOâ‚‚ Photocatalyst Synthesis

| Reagent | Function | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Titanium(IV) tetraisopropoxide (TTiP) | Primary titanium precursor | ≥97.0% purity, moisture-sensitive |

| Anhydrous isopropanol (i-PrOH) | Solvent and reaction medium | 99.5%, extra dry over molecular sieves |

| Acetic acid glacial (HAc) | Chelating agent and catalyst | Aldehyde-free |

| Nitric acid 65% (HNO₃) | Catalyst for condensation | Suprapur grade |

| Deionized water (d-H₂O) | Hydrolysis agent | 18.2 MΩ·cm resistivity |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Solution Preparation: In an inert atmosphere glove box, mix titanium(IV) tetraisopropoxide (TTiP, 0.1 mol) with anhydrous isopropanol (0.4 mol) under vigorous stirring (300 rpm) [4].

Hydrolysis and Chelation: Slowly add acetic acid (0.06 mol per mol TTiP) to control hydrolysis rate. After 30 minutes, add a stoichiometric amount of water (0.4 mol) dropwise to complete hydrolysis. Continue stirring for 3 hours at 25°C until a clear sol forms [4] [5].

Aging and Coating: Age the sol for 24 hours at room temperature. Deposit thin films via dip-coating (withdrawal rate 3 cm/min) or spin-coating (3000 rpm for 30s) onto cleaned substrates [4].

Thermal Treatment: Dry coatings at 80°C for 1 hour, then calcine at 450-500°C for 2 hours (heating rate 5°C/min) to crystallize the anatase phase [4].

Critical Parameters:

- Water-to-precursor ratio: 4:1 (molar)

- pH: ~3-4 (acid-catalyzed)

- Aging time: 24 hours

- Calcination temperature: 450-500°C for anatase formation

ZnO-SiOâ‚‚ Nanocomposite via Aqueous Sol-Gel

This protocol creates homogeneous ZnO-SiOâ‚‚ nanocomposites with interfacial Zn-O-Si bonds, enhancing photocatalytic performance through improved charge separation [6].

Research Reagent Solutions:

Table 3: Essential Reagents for ZnO-SiOâ‚‚ Nanocomposite Synthesis

| Reagent | Function | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) | Silicon precursor for SiO₂ matrix | ≥99.0% purity |

| Zinc acetate dihydrate | Zinc oxide precursor | Crystallized ≥99.0% |

| Ethanol absolute | Solvent | Anhydrous |

| Acetic acid | Catalyst for silica network | Analytical grade |

| Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) | Precipitation agent for ZnO | 1 M solution in ethanol |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Silica Sol Preparation: Prepare a mixture with TEOS:EtOH:H₂O molar ratio of 1:10:4. Add acetic acid (0.05 mol per mol TEOS) as catalyst. Stir vigorously at 300 rpm for 3 hours at 25°C [6].

ZnO Nanoparticle Synthesis: Dissolve zinc acetate dihydrate (10 g in 100 mL ethanol). Gradually add 1 M NaOH solution until precipitation is complete. Age the suspension for 24 hours [6].

Nanocomposite Formation: Mix the zinc hydroxide precipitate with the silica sol in 10:90 (ZnO:SiOâ‚‚) mass ratio. Stir for 2 hours to ensure homogeneous distribution [6].

Gelation and Processing: Transfer the mixture to sealed containers and gel at 75°C for 18 hours. Dry the wet gel at 120°C, then anneal at 450-700°C for 4 hours to form crystalline ZnO within the amorphous SiO₂ matrix [6].

Critical Parameters:

- Ethanol-to-TEOS ratio: 10:1 (prevents premature gelation)

- Gelation temperature: 75°C

- Aging time: 18 hours

- Annealing temperature: 450-700°C (controls ZnO crystallinity)

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for ZnO-SiOâ‚‚ nanocomposite synthesis showing sequential stages from precursor preparation to final thermal processing.

Structural Control and Photocatalytic Performance

The photocatalytic efficiency of sol-gel derived metal oxides is profoundly influenced by the structural parameters controlled during synthesis [7] [8]. Key performance-determining factors include:

Crystalline Phase: TiOâ‚‚ exists primarily as anatase, rutile, or brookite phases. Anatase (band gap = 3.2 eV) demonstrates superior photocatalytic activity compared to rutile (band gap = 3.02 eV) due to its higher Fermi level and slower charge carrier recombination [9] [8].

Surface Area and Porosity: The sol-gel process creates materials with high surface areas (up to 850 m²/g) and controlled pore sizes (typically 20-100 Å), enhancing pollutant adsorption and active site accessibility [1] [4]. The drying method determines final porosity - supercritical drying produces aerogels with >90% porosity, while ambient pressure drying yields xerogels with more moderate surface areas [2].

Dopant Incorporation: Homogeneous distribution of transition metal (Fe, Mn) or noble metal (Ag, Pt) dopants at the molecular level enhances visible light absorption and electron-hole separation [9] [4]. Silver nanoparticles (1-3 wt%) in TiOâ‚‚ act as electron traps, reducing recombination and improving pharmaceutical degradation efficiency by ~40% compared to undoped TiOâ‚‚ [4].

Table 4: Structural Parameters and Their Influence on Photocatalytic Performance

| Structural Parameter | Control Methods | Impact on Photocatalysis |

|---|---|---|

| Crystalline Phase | Calcination temperature, precursors | Anatase TiO₂ (≤500°C) shows highest activity; mixed phases can enhance performance via heterojunctions |

| Specific Surface Area | Water-to-precursor ratio, aging time, drying method | Higher surface area (>100 m²/g) increases active sites and pollutant adsorption capacity |

| Pore Size Distribution | Template agents, catalyst type, solvent | Mesopores (20-500 Ã…) facilitate diffusion of organic pollutants to active sites |

| Dopant Distribution | Precursor chemistry, mixing sequence | Homogeneous doping extends light absorption to visible range and reduces electron-hole recombination |

| Particle Size | Hydrolysis rate, calcination conditions | Smaller nanoparticles (<50 nm) reduce charge carrier migration distance to surface |

Advanced Applications in Photocatalysis

Sol-gel derived metal oxide photocatalysts demonstrate exceptional performance in environmental remediation and energy applications [7] [8]:

Pharmaceutical Degradation: Silver-doped TiOâ‚‚ thin films prepared via organic sol-gel routes show remarkable efficiency in degrading 15 pharmaceutical compounds including antibiotics, endocrine disruptors, and analgesics in wastewater treatment [4]. The modified TiOâ‚‚ with Evonik P25 and Ag nanoparticles demonstrated superior degradation efficiency under UV illumination.

Volatile Organic Compound (VOC) Removal: TiO₂-based photocatalysts effectively mineralize VOCs like formaldehyde, benzene, and toluene in indoor air through photocatalytic oxidation, generating harmless CO₂ and H₂O as final products [9]. The hydroxyl radicals (•OH) generated on illuminated TiO₂ surfaces non-selectively oxidize diverse organic contaminants.

Hydrogen Production: ZnO-SiOâ‚‚ and doped TiOâ‚‚ nanocomposites facilitate photocatalytic water splitting under UV and visible light irradiation. The sol-gel method enables precise control of metal dopants that enhance charge separation and reduce overpotential for hydrogen evolution [7] [6].

The sol-gel process continues to enable sophisticated material architectures for advanced photocatalytic applications, with ongoing research focusing on visible-light activation, heterojunction engineering, and hybrid organic-inorganic systems to address global environmental and energy challenges.

The sol-gel method has emerged as a powerful and versatile synthetic route for the preparation of advanced metal oxide photocatalysts. This wet-chemical technique enables precise control over material architecture at the nanometric scale, offering significant advantages for environmental remediation and energy applications. Within the broader context of sol-gel research for photocatalyst development, three fundamental benefits distinguish this approach: exceptional compositional control, superior homogeneity, and low-temperature processing capabilities. These characteristics are critical for tailoring photocatalytic properties such as band gap energy, surface characteristics, and charge carrier dynamics, ultimately determining efficiency in applications like water treatment and air purification [10] [9]. This document details these advantages through quantitative data, experimental protocols, and material guidelines to support research and development efforts.

Key Advantages and Quantitative Data

The sol-gel process provides distinct, quantifiable benefits for photocatalyst development, as demonstrated by recent research. The table below summarizes key performance metrics and structural properties achievable through sol-gel synthesis.

Table 1: Key Advantages of the Sol-Gel Method for Photocatalyst Synthesis

| Advantage | Key Feature | Experimental Outcome / Quantitative Data | Impact on Photocatalytic Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compositional Control | Precise dopant incorporation [11] | Ni doping in TiOâ‚‚ reduced band gap from 3.11 eV (undoped) to 2.49 eV (0.20 wt.% Ni) [11]. | Enables visible-light absorption; enhances solar efficiency. |

| Homogeneity | Molecular-level mixing [10] | Synthesis of homogeneous, reproducible nanoparticles with easily tuned particle size [10]. | Improves charge carrier mobility; reduces recombination sites. |

| Low-Temperature Processing | Crystallization at ≤350°C [12] | Fabrication of crystalline BiFeO₃ and β-Bi₂O₃ films on flexible polyimide substrates [12]. | Enables use of temperature-sensitive substrates (polymers, textiles). |

Experimental Protocols

General Workflow for Sol-Gel Photocatalyst Synthesis

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for synthesizing metal oxide photocatalysts via the sol-gel method, highlighting stages where key advantages are manifested.

Detailed Protocol: Synthesis of Ni-Doped TiOâ‚‚ (Ni-TiOâ‚‚) for Paracetamol Degradation

This protocol details the synthesis of visible-light-active Ni-TiOâ‚‚ photocatalysts, demonstrating high compositional control and homogeneity for pharmaceutical pollutant removal [11].

Materials

- Titanium precursor: Titanium tetraisopropoxide (TTIP, Câ‚â‚‚H₂₈Oâ‚„Ti ≥ 97%)

- Dopant precursor: Nickel(II) acetate tetrahydrate (Ni(CO₂CH₃)₂·4H₂O ≥ 98%)

- Solvent: Isopropyl alcohol

- Catalyst/Stabilizer: Acetic acid (CH₃COOH, 99.7%)

- Target pollutant: Acetaminophen (Paracetamol, CH₃CONHC₆H₄OH)

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve the required amount of TTIP in half of the total isopropyl alcohol volume under vigorous magnetic stirring (300 rpm) to form Solution A [13].

- Dopant Incorporation: Dissolve nickel(II) acetate tetrahydrate in a mixture of the remaining isopropyl alcohol and acetic acid. Acetic acid acts as a catalyst and chelating agent to stabilize the precursor and control hydrolysis rates [11] [13].

- Mixing and Hydrolysis: Slowly add the nickel-containing solution (Solution B) dropwise to Solution A under continuous stirring. This step initiates the hydrolysis reaction:

M–OR + H₂O → M–OH + ROH[14]. - Condensation and Gelation: Continue stirring the mixture for 6-12 hours at room temperature until a stable, colloidal sol forms. Condensation reactions proceed as:

M–OH + HO–M → M–O–M + H₂OandM–OH + RO–M → M–O–M + ROH(where M = Ti or Ni), building the metal-oxygen network [10] [14]. - Aging and Drying: Age the gel for 24 hours at room temperature, then transfer to a drying oven at 100°C for 24 hours to remove the solvent and obtain a xerogel.

- Calcination: Calcine the dried xerogel in a muffle furnace at 400-500°C for 1-4 hours to crystallize the amorphous material into the desired anatase phase of Ni-TiO₂ and remove residual organics [11].

Photocatalytic Testing Protocol

- Reactor Setup: Use a slurry photoreactor equipped with a visible light source (λ ≥ 420 nm).

- Reaction Conditions: Suspend the Ni-TiOâ‚‚ catalyst (3 g Lâ»Â¹) in an aqueous solution of paracetamol (5 ppm). Maintain constant air bubbling to provide oxygen.

- Activity Assessment: Monitor degradation by measuring the reduction in Total Organic Carbon (TOC). Under optimal conditions, Ni(0.1%)-TiOâ‚‚ achieves 88% TOC removal after 180 minutes [11].

- Stability Testing: Recover the catalyst by centrifugation and reuse for multiple cycles. High-performance catalysts retain ~84% efficiency after five cycles [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table lists key reagents and their critical functions in sol-gel synthesis of metal oxide photocatalysts.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Sol-Gel Photocatalyst Synthesis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Precursors | Titanium tetraisopropoxide (TTIP), Metal acetates (e.g., Calcium, Cobalt, Europium acetate) [11] [14] | Source of metal oxide network; determines stoichiometry and phase purity. |

| Dopant Sources | Nickel(II) acetate tetrahydrate [11], Europium(III) acetate hydrate [14] | Introduces impurity levels to modify band gap; enhances visible-light absorption. |

| Solvents | Isopropyl Alcohol, Ethanol [13] [15] | Dissolves precursors; controls reaction medium viscosity. |

| Catalysts/Stabilizers | Acetic Acid, Hydrochloric Acid (HCl) [13] | Catalyzes hydrolysis/condensation; chelates metals to control reaction kinetics and prevent precipitation. |

| Structure-Directing Agents | Poly(vinyl alcohol) - PVA [14] | Polymer precursor that aids complexation and modifies final material morphology and porosity. |

| 1-Ethoxyheptane-1-peroxol | 1-Ethoxyheptane-1-peroxol | 1-Ethoxyheptane-1-peroxol is a specialty organic peroxide for research (RUO) as a radical initiator or oxidant. It is for laboratory use only and not for human consumption. |

| Stannane, butyltriiodo- | Stannane, butyltriiodo-, CAS:21941-99-1, MF:C4H9I3Sn, MW:556.54 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Low-Temperature Processing Strategies

Conventional calcination remains a critical step for crystallization. However, advanced strategies can further reduce thermal budgets, enabling direct integration with flexible substrates.

Table 3: Strategies for Low-Temperature Crystallization of Sol-Gel Photocatalysts

| Strategy | Mechanism | Protocol Summary | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| UV-Light Assistance [12] | Photochemical breaking of chemical bonds and formation of new ones; creates a high-densified amorphous network that crystallizes more easily. | Synthesize photosensitive precursor solutions (e.g., with β-diketonate complexes). Irradiate deposited layers with continuous UV-excimer lamps during processing. | Crystallization of ferroelectric BiFeO₃ and β-Bi₂O₃ films at temperatures ≤ 350°C on polyimide. |

| Photosensitive Precursors [12] | Utilizes Metal-to-Ligand Charge Transfer (MLCT) transitions in metal complexes under UV light to advance organic removal and network formation. | Use metal complexes (e.g., with N-methyldiethanolamine) with high UV absorption. Irradiate the solution-deposited layer. | Formation of crystalline β-Bi₂O₃ at 250°C. |

| Heterogeneous Photocatalysis of Precursors [12] | TiO₂ particles in the precursor solution act as internal photocatalysts, breaking down organic entities upon UV irradiation before film deposition. | Add TiO₂ particles to the precursor solution. Irradiate the suspension, then remove particles via centrifugation. Use the "pre-catalyzed" solution for deposition. | Low-temperature fabrication of crystalline BiFeO₃ films. |

Application Notes: Performance of Sol-Gel Synthesized Metal Oxide Photocatalysts

The performance of metal oxide photocatalysts is critically dependent on their band gap energy and charge carrier dynamics, which can be precisely tuned through sol-gel synthesis parameters and compositional engineering.

Quantitative Analysis of Band Gap Engineering and Photocatalytic Efficiency

Table 1: Band Gap Engineering and Photocatalytic Performance of Sol-Gel Derived Metal Oxides

| Photocatalyst Material | Synthesis Details | Band Gap (eV) | Surface Area (m²/g) | Photocatalytic Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-doped TiO₂ (0.25 wt%) | Sol-gel reflux method | 3.31 → 2.97 (tunable with In concentration) | 102.998 | 85% MB degradation in 8 h (UV) | [16] |

| ZnO (Ethanol solvent) | Modified sol-gel | Not specified | Not specified | 98% MB degradation in "brief duration" | [17] |

| 90TiO₂-10Fe₂O₃/PVP | Sol-gel method | Reduced vs. pure TiO₂ (exact value not specified) | Not specified | Enhanced TCH degradation under UV/solar light | [18] |

| BaTiâ‚…Oâ‚â‚ (PEG-200) | Sol-gel method | 3.61 | 9.78 | Complete MB degradation in 30 min (UV) | [19] |

| WO₃ (Reference) | Various methods | 2.6-2.8 | Not specified | Theoretical STH efficiency up to 4.8% | [20] |

Charge Carrier Dynamics Fundamentals

The efficiency of photocatalytic reactions is governed by charge carrier dynamics, which include:

- Charge Generation: Electron-hole pair creation upon photon absorption with energy exceeding the band gap [20]

- Charge Separation: Prevention of recombination through doping, heterojunctions, or morphology control [21]

- Charge Migration: Movement of carriers to surface reaction sites [22]

- Charge Utilization: Participation in surface redox reactions [7]

The slow kinetics of photogenerated holes and fast recombination of charge carriers represent significant challenges in metal oxide photocatalysts such as WO₃ [20]. Research indicates that transition metal oxides (TiO₂, ZnO, NiO) face fundamental questions regarding the nature of elementary electronic excitations and how these excitations evolve after being created [22].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Sol-Gel Synthesis of Indium-Doped TiOâ‚‚ Nanoparticles for Enhanced Photocatalysis

Objective: To synthesize indium-doped TiOâ‚‚ nanoparticles with controlled band gap and improved charge carrier separation for photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants.

Materials and Equipment

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment

| Category | Item | Specification | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precursors | Titanium tetraisopropoxide | 97% purity | Primary TiOâ‚‚ source |

| Indium(III) salt | Varying concentrations (0.25-0.75 wt%) | Dopant for band gap engineering | |

| Solvents | Absolute ethanol | Anhydrous | Solvent for hydrolysis |

| 1-Propanol | Laboratory grade | Alternative solvent for comparison | |

| 1,4-Butanediol | Laboratory grade | High-boiling point solvent | |

| Equipment | Reflux apparatus | Standard setup | Controlled hydrolysis & condensation |

| Muffle furnace | Up to 600°C | Calcination and crystallization | |

| Magnetic stirrer | With heating capability | Solution mixing and gel formation |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Solution Preparation

- Dissolve titanium tetraisopropoxide (TTIP) in 50 mL of selected solvent (ethanol, 1-propanol, or 1,4-butanediol) with magnetic stirring at 50°C for 30 minutes [17]

- Prepare indium dopant solution by dissolving appropriate mass of indium precursor in 25 mL of the same solvent to achieve target doping concentration (0.25, 0.50, or 0.75 wt%) [16]

Mixing and Gelation

- Slowly add indium solution to TTIP solution with continuous stirring at 70°C

- Continue stirring until viscous gel forms (typically 1-2 hours)

- Age the gel overnight at 80°C to complete hydrolysis and condensation reactions

Calcination and Crystallization

Characterization

Protocol: Photocatalytic Activity Assessment via Methylene Blue Degradation

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate photocatalytic performance of synthesized metal oxides through degradation of methylene blue (MB) under UV irradiation.

Materials and Setup

- Photocatalyst powder (100 mg)

- Methylene blue solution (5 mg/L, 100 mL) [17]

- UV light source (e.g., Philips TL 8W BLB lamps, λ = 365 nm) [17] [18]

- Magnetic stirrer with illumination chamber

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer for concentration monitoring

Experimental Procedure

Reaction Setup

Kinetic Monitoring

- Collect 3 mL aliquots at regular time intervals (0, 15, 30, 60, 120, 240, 480 minutes)

- Centrifuge aliquots to remove catalyst particles

- Measure absorbance of supernatant at λmax = 664 nm using UV-Vis spectrophotometer

- Calculate degradation percentage using formula: Degradation % = [(A₀ - Aₜ)/A₀] × 100 where A₀ = initial absorbance, Aₜ = absorbance at time t

Performance Validation

- Compare degradation kinetics with undoped TiOâ‚‚ reference

- Calculate apparent rate constant (k) from linear regression of ln(A₀/Aₜ) vs. time

- For optimal 0.25 wt% In-doped TiOâ‚‚, expect ~85% degradation after 8 hours UV irradiation [16]

Advanced Tuning Strategies for Enhanced Performance

Band Gap Engineering Approaches

Table 3: Band Gap Engineering Strategies for Metal Oxide Photocatalysts

| Strategy | Mechanism | Effect on Band Gap | Example System | Performance Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cation Doping | Incorporation of foreign cations into crystal lattice | Gradual decrease with dopant concentration | In-doped TiOâ‚‚ [16] | 85% MB degradation (8 h UV) |

| Composite Formation | Heterojunction interface engineering | Effective band gap narrowing through interface states | TiO₂-Fe₂O₃/PVP [18] | Enhanced tetracycline degradation |

| Solvent Selection | Control of nucleation vs. growth kinetics | Indirect effect through quantum confinement | BaTiâ‚…Oâ‚â‚ with PEG-200 [19] | Complete MB degradation (30 min UV) |

| Morphology Control | Surface area and active site optimization | Minor direct effect, major impact on carrier transport | ZnO with ethanol solvent [17] | 98% MB degradation in brief duration |

Charge Carrier Separation Enhancement

Advanced heterostructure design represents a powerful approach to improve charge carrier separation:

- Type-II Heterojunctions: Create spatial separation of electrons and holes across material interfaces [21]

- Z-Scheme Systems: Mimic natural photosynthesis for simultaneous high redox power and charge separation [23]

- Morphology Control: Low-dimensional nanostructures (2D sheets, 1D rods) shorten carrier migration paths to surfaces [23]

The construction of metal oxide-based composites with complementary materials (carbon-based structures, polymers, other semiconductors) creates synergistic effects that enhance photocatalytic activity through improved charge separation, broadened light absorption, and increased surface area [21].

Troubleshooting and Optimization Guidelines

Common Synthesis Challenges and Solutions

Problem: Rapid hydrolysis and precipitation Solution: Use higher boiling point solvents (e.g., 1,4-butanediol instead of ethanol) to slow reaction kinetics [17]

Problem: Poor crystallinity after calcination Solution: Optimize calcination temperature (500-600°C typically optimal for anatase phase) and duration [16] [18]

Problem: Agglomeration of nanoparticles Solution: Introduce capping agents (e.g., PVP) during synthesis to control particle growth and dispersion [18]

Performance Optimization Parameters

- Dopant Concentration: Optimize around 0.25-0.75 wt% for metal dopants; excessive doping creates recombination centers [16]

- Solvent Selection: Higher viscosity solvents (PEG-200) promote nucleation over growth, yielding higher surface areas [19]

- Calcination Temperature: Balance between crystallinity (higher T) and surface area (lower T) for optimal activity [18]

These application notes and protocols provide a comprehensive framework for designing, synthesizing, and evaluating advanced metal oxide photocatalysts with tailored band structures and enhanced charge carrier dynamics for superior photocatalytic performance.

Metal oxide semiconductors, particularly titanium dioxide (TiOâ‚‚), zinc oxide (ZnO), and silicon dioxide (SiOâ‚‚), represent a cornerstone of modern photocatalytic research for environmental and energy applications. Their efficacy stems from unique physicochemical properties, including high surface area, tunable band gaps, and exceptional thermal and chemical stability [24]. Among various synthesis techniques, the sol-gel method stands out for fabricating these nanomaterials and their complex mixed-oxide composites. This chemical solution process allows for precise atomic-level control over composition and structure, facilitating the creation of tailored materials with enhanced photocatalytic performance, improved charge separation, and extended functional lifetime [25] [26]. This document provides a detailed overview of these metal oxide systems, their synergistic effects in mixed configurations, and standardized protocols for their synthesis and evaluation, framed within the context of advanced sol-gel research.

Individual Metal Oxide Systems: Properties and Functions

Titanium Dioxide (TiOâ‚‚)

TiOâ‚‚ is one of the most widely investigated photocatalysts due to its strong oxidative power, chemical inertness, non-toxicity, and relative cost-effectiveness [27] [25]. It primarily exists in two crystalline phases relevant to photocatalysis: anatase (band gap ~3.2 eV) and rutile (band gap ~3.0 eV). Anatase is generally recognized for its superior photocatalytic activity [28]. A key limitation of pure TiOâ‚‚ is its large band gap, which restricts its photoactivation to ultraviolet (UV) light, and the rapid recombination of its photogenerated electron-hole pairs [29]. The sol-gel method enables the production of TiOâ‚‚ nanoparticles with high surface area and controlled crystallinity, making it indispensable for applications ranging from water splitting to pollutant degradation [25] [26].

Zinc Oxide (ZnO)

ZnO is an n-type semiconductor with a wide direct band gap of ~3.37 eV [30]. It offers high electron mobility, which is beneficial for transporting photogenerated charge carriers and can lead to higher photocatalytic efficiencies in certain reactions compared to TiOâ‚‚ [29]. Beyond photocatalysis, ZnO exhibits potent antibacterial activity, making it suitable for biomedical coatings and self-cleaning surfaces [30] [31]. Similar to TiOâ‚‚, its wide band gap confines its activity to UV light, and it can suffer from photocorrosion. Sol-gel synthesis allows for the creation of diverse ZnO nanostructures, from nanoparticles to nanorods, by simply varying parameters like precursor concentration and pH [30].

Silicon Dioxide (SiOâ‚‚)

SiO₂ is primarily known as an electrical insulator and is not an active photocatalyst itself. However, its role in composite systems is crucial. SiO₂ serves as an excellent support matrix or host for active metal oxides like TiO₂ and ZnO due to its high surface area, thermal stability, and chemical inertness [30] [32]. When integrated into a composite, SiO₂ inhibits the agglomeration of photocatalytic nanoparticles, enhances the material's adsorptive capacity, and improves the dispersion and adhesion of the active phase in coatings [30] [26]. Furthermore, the formation of chemical bonds (e.g., Ti–O–Si) at the interface can stabilize the composite and modify the electronic properties of the active photocatalyst [30] [32].

Mixed Metal Oxide Systems: Synergistic Enhancements

Combining individual metal oxides creates mixed oxide systems where synergistic effects lead to performance metrics surpassing those of the individual components. Key enhancements include increased surface area, suppressed electron-hole recombination, and extended light absorption into the visible range.

Table 1: Photocatalytic Performance of Selected Mixed Oxide Systems

| Composite System | Optimal Composition | Target Pollutant/Reaction | Reported Efficiency | Key Enhancement Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiO₂–SiO₂ [33] [32] | 85:15 (Ti:Si molar ratio) | Rhodamine B (RhB) dye | ~92% degradation in 6 h [33] | Increased surface area; formation of Ti–O–Si bonds; better nanoparticle dispersion. |

| W-TiOâ‚‚ [27] | 2 mol% W | Methylene Blue (MB) | Peak photocatalytic decomposition | Enhanced charge separation; visible light activation. |

| W-TiOâ‚‚ [27] | 15 mol% W | Methylene Blue (MB) | Most effective overall removal (adsorption + photocatalysis) | Maximal adsorption capacity synergy. |

| Ti–Fe Mixed Oxide [25] | 5 wt.% Fe | Hydrogen generation from water | Higher activity than pure TiO₂ | Fe³⺠acts as electron-hole sink, improving charge separation. |

| ZnO–SiO₂ [30] | 10:90 (Zn:Si) | (Material designed for H₂ sorption) | Increased specific surface area | SiO₂ matrix prevents ZnO aggregation. |

| TiOâ‚‚/ZnO/SiOâ‚‚ [29] | Nanocomposite | Removal of Pb(II) ions | Effective under visible light | Combined benefits of all three oxides; narrower band gap. |

Charge Separation and Visible Light Activation

The interface between two metal oxides can create a energy gradient that drives the separation of photogenerated electrons and holes. For instance, in W-TiOâ‚‚ systems, Wâ¶âº states can act as electron traps, reducing the recombination rate of charge carriers and thus enhancing photocatalytic efficiency [27]. Similarly, doping TiOâ‚‚ with Fe³⺠introduces new energy levels within the band gap, enabling the material to absorb photons from the visible portion of the solar spectrum [25]. This is a critical advancement for deploying photocatalysts under natural sunlight.

Experimental Protocols: Sol-Gel Synthesis and Characterization

This section provides detailed methodologies for the synthesis and evaluation of mixed oxide photocatalysts, based on published research.

Protocol 1: Synthesis of TiO₂–SiO₂ Nanocomposite

This protocol is adapted from the synthesis of highly active TiO₂–SiO₂ nanocomposites for dye degradation [33] [32].

Research Reagent Solutions: Table 2: Essential Reagents for TiO₂–SiO₂ Nanocomposite Synthesis

| Reagent | Function in Synthesis |

|---|---|

| Titanium(IV) Isopropoxide (TTIP) | Precursor for TiOâ‚‚ nanoparticles. |

| Tetraethyl Orthosilicate (TEOS) | Precursor for the SiOâ‚‚ matrix. |

| Ethanol (Câ‚‚Hâ‚…OH) | Solvent; provides homogenization between precursors and water. |

| Hydrochloric Acid (HCl, 0.5 M) | Acid catalyst for hydrolysis and condensation reactions. |

| Deionized Water | Reactant for hydrolysis of metal alkoxides. |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Preparation of SiOâ‚‚ Sol: Add 1 mol of TEOS to a solution of 30 mol of ethanol. Under constant stirring, add 3 mL of 0.5 M HCl dropwise. Continue stirring for 3 hours at room temperature [32].

- Preparation of TiOâ‚‚ Sol: In a separate vessel, add 1 mol of TTIP to a solution of 30 mol of isopropanol. Under constant stirring, add 3 mL of 0.5 M HCl dropwise. Continue stirring for 3 hours at room temperature [32].

- Mixing and Gelation: Combine the SiOâ‚‚ and TiOâ‚‚ sols in a 1:1 molar ratio (or as required for the target composition, e.g., 85:15 for TiOâ‚‚:SiOâ‚‚). Stir the mixture for 45 minutes at room temperature to form a homogeneous mixed oxide gel [33] [32].

- Aging and Drying: Allow the gel to age and dry naturally at room temperature until a solid "dry gel" is obtained. Crush this gel into a fine powder.

- Calcination: Subject the powder to calcination in a furnace at 600°C for 5 hours. This step removes residual organic solvents, stabilizes the material, and develops the crystalline anatase phase of TiO₂ [32].

Protocol 2: Synthesis of W-TiOâ‚‚ Nanopowder

This protocol outlines the synthesis of W-TiOâ‚‚ nanopowders with enhanced adsorption and photocatalytic properties [27].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Solution A (TTIP Solution): Dissolve Titanium Isopropoxide (TTIP) in 2-propanol under stirring at 500 rpm for 15 minutes to achieve a total precursor concentration (CTi + CW) of 0.3 mol/L.

- Solution B (Water/Alcohol): Mix the required amount of deionized water with 2-propanol separately, with a hydrolysis ratio of h = CH2O/(CTi + CW) = 1.25. Stir for 15 minutes.

- Hydrolysis and Nanoparticle Nucleation: Slowly add Solution B into Solution A under intense stirring. This triggers the hydrolysis of TTIP and the nucleation of titanium oxo-alkoxy nanoparticles.

- Doping with Tungsten: To incorporate tungsten, dissolve the required amount of Tungsten(VI) Chloride (WCl₆) in 2-propanol to create the doping solution. This can be added during the mixing stage to achieve the desired molar ratio (x = CW/(CW + CTi)).

- Drying and Calcination: Allow the colloidal solution to dry in a fume hood at room temperature for 5 days. Subsequently, dry the resulting amorphous powder in an oven at 85°C for 2 days. Finally, calcine the powder in a furnace at 450–600°C for 4 hours to crystallize the anatase phase.

Key Characterization Techniques

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD): Used to identify crystalline phases, estimate crystallite size using the Scherrer equation, and determine phase composition (e.g., anatase vs. rutile in TiOâ‚‚) [30] [32].

- UV-Vis Spectroscopy: Employed to study the electronic excitation behavior of the material and estimate the band gap energy via Tauc plots [33] [31].

- Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) & Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDX): Provide insights into surface morphology, particle size, and elemental composition/homogeneity [33] [30].

- Fourier-Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy: Identifies functional groups and confirms the formation of chemical bonds in composites, such as Ti–O–Si or Zn–O–Si [33] [30].

- Nitrogen Physisorption (BET): Measures the specific surface area, pore volume, and pore size distribution, which are critical for adsorption and catalytic activity [25].

Visualizing Synthesis and Charge Separation Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate the core workflows and mechanisms involved in mixed oxide photocatalysis.

Diagram 1: Generalized sol-gel synthesis workflow for mixed oxides.

Diagram 2: Enhanced charge separation mechanism in a W-TiOâ‚‚ mixed oxide.

The sol-gel method is a versatile and powerful chemical technique for synthesizing metal oxide photocatalysts, offering unparalleled control over material properties at the nanoscale. This bottom-up approach involves the transition of a solution system from a liquid "sol" into a solid "gel" phase, enabling precise manipulation of the final material's morphology, porosity, and surface characteristics [2] [34]. In photocatalytic applications, where performance is critically dependent on surface area, charge transport, and light absorption, the ability to engineer nanostructure through sol-gel chemistry provides a fundamental advantage [7] [21]. By carefully controlling synthesis parameters, researchers can tailor photocatalytic materials with enhanced activity for applications ranging from environmental remediation to energy conversion [35].

The connection between synthetic control and functional performance is paramount. Photocatalytic efficiency depends on a material's capacity to absorb light, generate charge carriers (electrons and holes), and facilitate their migration to the surface to drive chemical reactions without recombination [7]. Nanostructuring directly influences each of these processes; for instance, high surface area provides more active sites, controlled porosity affects molecular diffusion, and crystalline phase impacts electronic band structure [36] [37]. The sol-gel process, through its molecular-level mixing and low-temperature processing, allows for precise tuning of these structural parameters to overcome common limitations in photocatalysis, such as rapid electron-hole recombination and limited visible-light absorption [3] [21].

Key Parameters for Morphology Control in Sol-Gel Synthesis

The sol-gel technique provides multiple adjustable parameters that directly influence the morphology and, consequently, the photocatalytic performance of the resulting metal oxides. Understanding and controlling these parameters is essential for designing efficient photocatalysts.

Table 1: Key Sol-Gel Synthesis Parameters and Their Impact on Final Material Properties

| Control Parameter | Impact on Morphology & Structure | Effect on Photocatalytic Activity |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Type | Determines crystallite size, phase formation temperature, and grain morphology [38]. | Influences light absorption edge, charge carrier mobility, and surface defect chemistry [38] [34]. |

| Surfactant/Template | Directly controls porosity, specific surface area (BET), and particle shape (e.g., spherical, fibrous) [36]. | Higher surface area increases active sites; pore size affects reactant diffusion; morphology can enhance light harvesting [36]. |

| Catalyst (pH) | Affects the gel network structure (polymeric vs. particulate) and its density [2] [34]. | Alters the density of surface hydroxyl groups and the rate of electron-hole recombination [34]. |

| Annealing Temperature | Controls crystallinity, crystallite size, phase composition, and defect concentration (e.g., oxygen vacancies) [38] [37]. | Improved crystallinity typically reduces charge recombination; excessive temperature can reduce surface area [37]. |

| Sol Aging Duration | Influences the viscosity of the sol and the thickness and porosity of deposited films [35]. | Optimized aging leads to higher porosity and better accessibility to active sites, enhancing performance [35]. |

The relationship between these parameters and the resulting photocatalytic activity is often synergistic. For example, research on ZrO₂ thin films demonstrated that using zirconium acetate as a precursor, combined with an annealing temperature of 500°C and a film thickness of 940 nm, produced a material with superior optical and crystalline quality. This optimally structured film achieved a 94% photocatalytic degradation efficiency of methylene blue dye within 150 minutes, significantly outperforming films made from other zirconium sources like nitrate or chloride [38]. This highlights how the careful selection of a single precursor can dictate the structural and functional outcome.

Furthermore, the use of surfactants and templates represents a powerful strategy for morphological engineering. A study on TiO₂ anatase phase synthesis revealed that using sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) as an ionic surfactant resulted in a spherical morphology with a high specific surface area of 138.72 m²/g and a mesoporous structure. These morphological traits improved light absorption in the visible region and gave the material the highest photocatalytic activity for methylene blue degradation compared to samples prepared with other surfactants or no surfactant [36]. The ability to fine-tune such textural properties is a distinct advantage of the sol-gel method.

Experimental Protocols for Morphology-Controlled Synthesis

Protocol: Surfactant-Assisted Sol-Gel Synthesis of Mesoporous TiOâ‚‚

This protocol details the synthesis of high-surface-area, mesoporous TiOâ‚‚ using ionic and non-ionic surfactants, based on the methodology that demonstrated superior photocatalytic performance [36].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Titanium Alkoxide Precursor: Titanium isopropoxide (Ti(OCH(CH₃)₂)₄) or titanium butoxide (Ti(OC₄H₉)₄). Functions as the primary source of titanium ions.

- Anhydrous Ethanol: Serves as the solvent for the alkoxide precursor.

- Surfactant Solutions:

- SDS (Anionic): 0.1 M Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate in ethanol/water.

- CTAB (Cationic): 0.1 M Cetyltrimethylammonium Bromide in ethanol/water.

- PEG (Non-ionic): 5% w/v Polyethylene Glycol (MW ~10,000) in ethanol/water.

- Acid Catalyst: Dilute nitric acid (HNO₃) or acetic acid (CH₃COOH) to catalyze hydrolysis and condensation.

- Deionized Water: For hydrolysis of the metal alkoxide.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sol Preparation: In a dry beaker, dissolve 10 mmol of the titanium alkoxide in 50 mL of anhydrous ethanol under constant stirring. This forms the precursor solution.

- Surfactant Addition: To this solution, add 50 mL of the chosen surfactant solution (SDS, CTAB, or PEG). Stir the mixture for 1 hour at room temperature to ensure homogeneity.

- Catalyzed Hydrolysis: Slowly add a mixture of 5 mL of the acid catalyst and 5 mL of deionized water dropwise to the stirring solution. The molar ratio of water to alkoxide is critical and should typically be between 4:1 and 10:1.

- Gelation and Aging: Continue stirring for 2-4 hours until the solution becomes translucent and viscous, indicating gel formation. Cover the beaker with perforated parafilm and allow the gel to age at room temperature for 24-48 hours.

- Drying: Transfer the aged gel to an oven and dry at 80°C for 12 hours to remove the solvent, resulting in a xerogel.

- Calcination: Place the xerogel in a furnace and heat to 450-500°C at a ramp rate of 2°C/min. Maintain this temperature for 4 hours to remove the surfactant template completely, crystallize the TiO₂ into the anatase phase, and develop the desired mesoporous structure.

Protocol: Precursor-Dependent Synthesis of ZrOâ‚‚ Thin Films

This protocol outlines the formation of ZrOâ‚‚ thin films with tunable properties using different zirconium sources, a key factor in optimizing photocatalytic activity [38].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Zirconium Precursors:

- Zirconium(IV) Acetate: Leads to films with high optical and crystalline quality.

- Zirconium(IV) Oxynitrate: For comparison of nitrate-derived properties.

- Zirconium(IV) Oxychloride: For comparison of chloride-derived properties.

- Solvent: A mixture of ethanol and deionized water.

- Complexing Agent: Acetylacetone, which can be added to modify precursor reactivity and stabilize the sol.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sol Formulation: Dissolve 0.1 mol of the selected zirconium precursor in 100 mL of a 1:1 v/v ethanol/water solvent mixture. Stir vigorously until a clear solution is obtained.

- Sol Aging: Allow the sol to age for 24 hours at room temperature. This aging process allows for the initial development of the metal-oxo polymer network, which influences the final film's homogeneity and thickness [35].

- Substrate Preparation: Clean glass substrates sequentially in an ultrasonic bath with acetone, ethanol, and deionized water. Dry the substrates in a stream of nitrogen gas.

- Dip-Coating: Immerse the clean substrate into the aged sol and withdraw it at a controlled, constant rate (e.g., 2-5 cm/min). The withdrawal speed is a primary factor in determining the final film thickness.

- Drying and Pre-annealing: Immediately after deposition, dry the wet film at 100°C for 10 minutes on a hotplate to evaporate the solvent.

- Thermal Annealing: Transfer the film to a pre-heated furnace and anneal at 500°C for 1 hour. This step is crucial for developing the tetragonal crystalline phase of ZrO₂ and removing any residual organics, thereby establishing the final optical and photocatalytic properties [38].

Visualizing the Sol-Gel Morphology Control Pathway

The following workflow diagram illustrates the critical decision points in a sol-gel synthesis and how specific parameter choices lead to distinct material morphologies and photocatalytic outcomes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Sol-Gel Synthesis

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Sol-Gel Synthesis of Photocatalysts

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Precursors | Titanium isopropoxide, Zinc acetate, Zirconium(IV) acetate [38] [37] | Source of metal cations; the ligand type (alkoxide, acetate, chloride) governs reactivity, hydrolysis rate, and final grain morphology. |

| Solvents | Ethanol, Isopropanol, Diethylene glycol [37] | Dissolve precursors to form a homogeneous sol; the polarity and boiling point influence reaction kinetics and drying behavior. |

| Surfactants / Templates | SDS, CTAB, PEG, Pluronic polymers [36] | Structure-directing agents that self-assemble to create controlled pore sizes and high surface area, preventing particle agglomeration. |

| Catalysts | Nitric acid, Acetic acid, Ammonium hydroxide [2] [34] | Modify pH to control the relative rates of hydrolysis and condensation, determining gel network structure (polymeric or particulate). |

| Complexing Agents | Acetylacetone, Citric acid [34] | Chelate metal ions to moderate their reactivity, prevent precipitation, and promote atomic-scale homogeneity in multi-metal systems. |

| Urea, (p-hydroxyphenethyl)- | Urea, (p-hydroxyphenethyl)- | Urea, (p-hydroxyphenethyl)- is a chemical for research (RUO). It is not for human, veterinary, or household use. Explore its value as a urease inhibitor and antimicrobial agent. |

| Chloro(diethoxy)borane | Chloro(diethoxy)borane, CAS:20905-32-2, MF:C4H10BClO2, MW:136.39 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The sol-gel method stands as a profoundly effective technique for engineering the morphology of metal oxide photocatalysts. By manipulating a suite of interconnected parameters—including precursor chemistry, surfactant templating, catalysis conditions, and thermal treatment—researchers can exert precise control over critical structural properties such as specific surface area, porosity, crystallinity, and defect concentration. This tunability directly translates to enhanced photocatalytic performance by optimizing light absorption, charge carrier separation, and surface reaction kinetics. The provided protocols and data offer a foundational toolkit for designing sol-gel synthesized materials with tailored nanostructures for advanced photocatalytic applications, from environmental remediation to sustainable energy conversion.

Practical Synthesis Protocols and Advanced Material Architectures for Enhanced Photocatalysis

The sol-gel process is a versatile, solution-based chemical method for synthesizing metal oxide nanostructures at relatively low temperatures. This technique is particularly valuable in the field of photocatalysis, as it enables precise control over the composition, morphology, and textural properties of metal oxide materials, which directly influence their light absorption capacity, charge carrier separation, and surface reactivity [21] [5]. The process involves the transformation of a colloidal solution (sol) of precursor molecules into an integrated, three-dimensional network (gel) through a series of hydrolysis and condensation reactions [39] [5]. For photocatalytic applications, such as pollutant degradation and hydrogen production via water splitting, the sol-gel method facilitates the creation of high-purity, homogeneous, and porous metal oxide frameworks (e.g., TiOâ‚‚, ZnO) with high surface areas, which are critical for enhancing catalytic activity [21] [5]. The ability to dope these oxides with other metals or integrate them into composite structures at the molecular level further allows for the fine-tuning of their electronic band structure, thereby improving their responsiveness to visible light [21] [3].

Foundational Chemistry and Principles

The sol-gel process is governed by two primary classes of chemical reactions: hydrolysis and condensation. The sequence and kinetics of these reactions are critical for determining the structure of the resulting gel network and the final properties of the metal oxide material [5].

- Hydrolysis: This initial step involves the nucleophilic attack of a water molecule on a metal atom (M) in the precursor, leading to the replacement of an alkoxide group (OR) with a hydroxyl group (OH) [5].

M(OR)₄ + H₂O → M(OR)₃(OH) + ROH - Condensation: Following hydrolysis, the partially hydrolyzed species link together through polycondensation. This occurs via two main pathways:

- Oxolation:

M-OH + M-OR → M-O-M + ROH - Olation:

M-OH + M-OH → M-O-M + H₂OThese reactions proceed to form an extensive metal-oxygen-metal (M-O-M) network, characteristic of the final metal oxide [5].

- Oxolation:

The rates of these reactions are profoundly influenced by the pH of the solution, which dictates the nucleophilicity of the attacking species and the electrophilicity of the metal center [39] [5]. As visually summarized in the diagram below, the reaction pathway and resulting gel structure diverge significantly under acidic versus basic conditions.

Experimental Protocols

Precursor Selection and Solution Preparation

The selection of precursors is the first critical step in designing a sol-gel synthesis, as it determines the reactivity, purity, and homogeneity of the final metal oxide. The table below categorizes and compares common precursor types.

Table 1: Common Precursor Types in Sol-Gel Synthesis

| Precursor Type | Examples | Key Characteristics | Impact on Final Material |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Alkoxides | Titanium isopropoxide, Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) [39] | High reactivity, sensitive to moisture, produce high-purity oxides [39] | Excellent stoichiometry control, high homogeneity [5] |

| Metal Inorganic Salts | Bismuth nitrate [Bi(NO₃)₃·5Hâ‚‚O], Aluminum nitrate [40] [39] | Lower cost, less sensitive to handling, may require acid for dissolution [40] | Can introduce anionic impurities (e.g., NO₃â», Clâ»); requires careful calcination [40] |

| Chelated Complexes | Citric acid complexes, Acetylacetonate complexes [40] [5] | Modified reactivity, slower condensation, reduced precipitation [40] | Enhanced molecular-level mixing, finer particle size, prevents premature precipitation [40] [5] |

Protocol: Preparation of a Citrate-Modified Precursor Sol for Mixed Oxide Synthesis (e.g., BiBaO₃) [40]

- Dissolution of Metal Salts:

- In Beaker A, dissolve a stoichiometric amount of bismuth nitrate pentahydrate

[Bi(NO₃)₃·5H₂O]in 20 mL of distilled water. - In Beaker B, disperse a stoichiometric amount of barium carbonate

[BaCO₃]in 40 mL of dilute nitric acid[HNO₃]under continuous stirring until a clear solution of barium nitrate is formed and CO₂ evolution ceases.

- In Beaker A, dissolve a stoichiometric amount of bismuth nitrate pentahydrate

- Mixing and Complexation:

- Combine the solutions from Beakers A and B while stirring thoroughly.

- Heat the mixed solution to approximately 70°C while maintaining continuous stirring for 1 hour to ensure homogeneity.

- Add ethylene glycol and citric acid as complexing and gelling agents. A 1:1 molar ratio of the total metal ions to both citric acid and ethylene glycol is typically used.

- Sol Formation:

- Continue heating and stirring the mixture at 70-80°C for several hours (typically 3-5 hours) until a transparent, viscous sol is formed. The solution should remain clear without any visible precipitation.

Catalyst Use and Reaction Control

The type and concentration of the catalyst are powerful tools for directing the sol-gel process toward a desired material structure, as outlined in the reaction pathway diagram. The choice between acid and base catalysis directly affects the reaction kinetics and the morphology of the growing gel network [39] [5].

Table 2: Effect of Catalyst Type on Sol-Gel Kinetics and Gel Structure

| Parameter | Acid Catalysis (pH < 7) | Base Catalysis (pH > 7) |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrolysis Rate | Slower, more controlled [39] | Faster [39] |

| Condensation Mechanism | Favors olation (M-OH + M-OH) or reactions of protonated species, leading to linear polymers [5] | Favors oxolation (M-OR + M-OH), leading to highly branched clusters [5] |

| Primary Reactive Site | Protonated alkoxide group (M-ORHâº) [5] | Deprotonated hydroxyl group (M-Oâ») [5] |

| Resulting Gel Structure | Low-density polymer gel: Entangled linear chains, leading to finer pores and higher specific surface area [39] [5] | High-density particulate gel: Dense, colloidal aggregates of branched clusters, leading to larger pores and lower surface area [39] [5] |

| Typical Catalysts | HCl, HNO₃, Acetic acid [40] [39] | NH₄OH, NaOH [39] |

Protocol: Acid-Catalyzed Synthesis of Monolithic Silica [41] [39]

- Precursor Preparation: Dilute tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) in ethanol (e.g., 1:4 molar ratio TEOS:EtOH).

- Acidified Water Preparation: Mix a precise amount of distilled water (e.g., 4:1 molar ratio Hâ‚‚O:TEOS) with a mineral acid like HCl to achieve a pH of approximately 2.

- Catalyzed Hydrolysis: Slowly add the acidified water to the TEOS/ethanol solution under vigorous stirring. Maintain the reaction at room temperature for 1 hour to allow for controlled, complete hydrolysis.

- Gelation: After hydrolysis, the solution may be cast into a mold. Gelation under acidic conditions will proceed slowly, forming a transparent, monolithic wet gel over a period of hours to days.

Aging Conditions and Gel Modification

Aging is the process of allowing the newly formed gel to remain in its mother liquor for a specific duration. This step is crucial for strengthening the gel network and controlling its porosity through ongoing chemical reactions and physical processes [39].

- Syneresis: The spontaneous shrinkage of the gel and expulsion of liquid from its pores due to the formation of new chemical bonds, which increases the connectivity and mechanical strength of the network [39].

- Ostwald Ripening: A process where smaller, more soluble particles dissolve and re-deposit onto larger, more stable particles. This reduces the surface energy of the system, leading to a more uniform particle size distribution and thickening of gel necks between particles [39].

- Polycondensation: Aging allows further condensation reactions to occur, which strengthens the M-O-M network throughout the gel [39].

Protocol: Controlled Aging and Drying for High-Surface-Area Xerogels [39]

- Sealing and Aging: After gelation, seal the container to prevent solvent evaporation. Allow the gel to age at room temperature for 24-72 hours. For accelerated aging, the process can be conducted at an elevated temperature (e.g., 50-60°C) for a shorter duration (e.g., 6-12 hours).

- Solvent Exchange (Optional but Recommended): To reduce capillary stresses during drying and minimize cracking, slowly replace the pore liquid (e.g., water/ethanol) with a solvent of lower surface tension, such as acetone or hexane. This is done by immersing the aged gel in the new solvent for 12-24 hours, repeating if necessary.

- Drying: The solvent-filled gel is dried slowly at ambient pressure and temperature (xerogel formation) to produce a porous solid. For applications requiring ultra-high porosity, supercritical drying (producing an aerogel) is employed to avoid pore collapse by eliminating liquid-vapor interfaces [41] [39].

Heat Treatment (Calcination)

Calcination is the final thermal treatment step that converts the porous, amorphous xerogel into a crystalline metal oxide with tailored functional properties [39].

Protocol: Standard Calcination for Crystallization [39]

- Loading: Place the dried xerogel powder or monolith in a high-temperature stable crucible.

- Thermal Ramping: Transfer the crucible to a pre-programmed furnace. Heat the sample at a controlled ramp rate (e.g., 2-5°C per minute) to the target temperature. A slow ramp rate is critical to prevent violent combustion of residual organics and avoid cracking or foaming.

- Dwell Time: Maintain the sample at the target temperature (e.g., 400-800°C, depending on the metal oxide) for 2-6 hours. This ensures complete removal of organic species and residual solvents, and allows for full crystallization and growth of the desired crystal phase.

- Atmosphere Control: Perform calcination in a static air atmosphere for most applications. For metals prone to oxidation reduction states, a controlled (inert or reducing) atmosphere may be used to create oxygen vacancies, which can enhance photocatalytic activity [39].

- Cooling: Allow the sample to cool slowly to room temperature inside the turned-off furnace to minimize thermal stress.

The entire sol-gel workflow, from precursor preparation to final heat treatment, is summarized in the following diagram.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Sol-Gel Synthesis

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Example in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Alkoxides (e.g., TEOS, Ti(OiPr)â‚„) | Primary network formers; source of metal oxide upon hydrolysis and condensation [39] [5] | Titanium isopropoxide for TiOâ‚‚ photocatalyst synthesis [39] |

| Metal Salts (e.g., Nitrates, Chlorides) | Cost-effective alternative precursors; require calcination to remove anionic impurities [40] [39] | Bismuth nitrate for Bi-containing perovskites [40] |

| Solvents (e.g., Ethanol, 2-Methoxyethanol) | Dissolve precursors; medium for chemical reactions; control concentration and viscosity [42] [39] | Ethanol for diluting TEOS [39]; 2-Methoxyethanol as a dominant solvent for BiFeO₃ [42] |

| Mineral Acids/Bases (e.g., HCl, NH₄OH) | Catalysts that control pH, reaction rates, and the structure of the gel network [39] [5] | HCl for acid-catalyzed silica synthesis; HNO₃ for dissolving barium carbonate [40] [39] |

| Chelating Agents (e.g., Citric Acid, Acetylacetone) | Modify precursor reactivity; promote homogeneity in multi-component systems; prevent precipitation [42] [40] | Citric acid as a chelating agent in BiBaO₃ and BiFeO₃ synthesis [42] [40] |

| Drying Control Chemical Additives (DCCAs) (e.g., Formamide, Glycerol) | Reduce capillary pressure during drying by modifying surface tension, minimizing cracking of monoliths [41] | Used during the aging/drying step to produce crack-free monoliths [41] |

| Structure-Directing Agents (Templates) (e.g., Surfactants, Block Copolymers) | Create ordered mesoporous structures by self-assembly; removed during calcination to leave behind pores [5] | Used to create mesoporous TiOâ‚‚ with high surface area for photocatalysis [5] |

| Cyclotetradecane-1,2-dione | Cyclotetradecane-1,2-dione|C14H24O2|CAS 23427-68-1 | Cyclotetradecane-1,2-dione is a 14-membered macrocyclic dione for chemical and conformational research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| 3-Methyl-5-phenylbiuret | 3-Methyl-5-phenylbiuret|High-Purity Research Chemical | 3-Methyl-5-phenylbiuret for research applications. This compound is For Research Use Only (RUO), not for diagnostic or personal use. |

Concluding Remarks

The sol-gel method offers a powerful and versatile pathway for synthesizing advanced metal oxide photocatalysts. The precise control over each stage of the process—from the initial selection of precursors and catalysts to the careful management of aging and calcination conditions—enables researchers to engineer materials with specific compositional, structural, and textural properties. By adhering to the detailed protocols and principles outlined in this document, scientists can systematically develop and optimize sol-gel-derived photocatalysts, thereby advancing research in environmental remediation and sustainable energy generation.

The sol-gel process represents a versatile chemical technique for the fabrication of metal oxide networks through the transition of a solution system from a liquid "sol" into a solid "gel" phase. While conventional sol-gel methods provide excellent control over composition and homogeneity, recent advancements integrating hydrothermal and microwave assistance have significantly enhanced the capabilities of this synthesis route. These advanced fabrication techniques enable superior control over crystallinity, particle size, morphology, and photocatalytic performance of metal oxides, addressing key limitations of traditional approaches such as irregular crystallinity and prolonged processing times [43] [19] [44].

Within the context of metal oxide photocatalyst synthesis, these advanced sol-gel methods facilitate the creation of materials with tailored properties essential for efficient photocatalytic activity. The synergy between sol-gel chemistry and hydrothermal or microwave energy input has opened new avenues for designing novel photocatalytic materials with enhanced charge separation, reduced recombination losses, and improved quantum efficiency. This technical note provides detailed protocols and application guidelines for researchers developing advanced metal oxide photocatalysts through these innovative synthesis routes.

Hydrothermal-Assisted Sol-Gel Synthesis

Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

Hydrothermal-assisted sol-gel synthesis combines the molecular-level mixing advantages of conventional sol-gel processing with the crystallinity enhancement offered by hydrothermal treatment. This hybrid approach subjects the gel precursor to elevated temperatures and pressures in a sealed autoclave, creating conditions that promote enhanced crystallization kinetics and thermodynamic stability of the resulting metal oxides. The hydrothermal environment facilitates the dissolution and recrystallization processes, leading to the formation of highly crystalline phases at significantly lower temperatures compared to conventional calcination routes [45] [46].

The mechanism involves several sequential stages: (1) hydrolysis and condensation of metal precursors to form a colloidal sol, (2) gelation through polycondensation reactions, (3) hydrothermal crystallization under autogenous pressure, and (4) Ostwald ripening for crystal growth and morphology control. The elevated temperature and pressure conditions during hydrothermal treatment enhance the solubility and reactivity of the precursor species, promoting direct crystallization from the amorphous gel network. This process typically yields materials with higher phase purity, better-defined morphologies, and improved thermal stability compared to those obtained through conventional sol-gel routes followed by calcination [19].

Experimental Protocol: BaTiO₃ Nanoparticle Synthesis

Materials and Reagents:

- Barium acetate (C₄H₆BaO₄, ACS reagent, ≥99%)

- Titanium butoxide (Ti[O(CH₂)₃CH₃]₄, reagent grade, 97%)

- Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP, MW ≈ 40,000)

- Acetic acid (glacial, ≥99%)

- Ethanol absolute (≥99%)

- Sodium hydroxide (NaOH, reagent grade, ≥98%)

- Deionized water (resistivity ≥18 MΩ·cm)

Procedure:

- Precursor Solution Preparation: Dissolve 0.02 mol barium acetate in 40 mL deionized water with continuous stirring at 60°C. Add acetic acid dropwise until complete dissolution is achieved (final pH ≈ 4).

Titanium Solution Preparation: In a separate vessel, mix 0.02 mol titanium butoxide with 40 mL ethanol under nitrogen atmosphere. Add 2 g PVP as a capping agent and stir until complete dissolution.

Sol Formation: Slowly add the titanium solution to the barium solution with vigorous stirring (600 rpm) over 30 minutes. Maintain the temperature at 60°C and continue stirring for 2 hours to form a stable, transparent sol.

Gelation and Aging: Transfer the sol to a sealed container and age at 80°C for 24 hours to form a wet gel. The gel should exhibit a translucent, homogeneous appearance.

Hydrothermal Treatment: Transfer the gel to a Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave, filling 70-80% of its capacity. Conduct hydrothermal treatment at 180-220°C for 12-48 hours. The specific temperature and duration depend on the desired crystal size and phase composition [45].

Product Recovery: After natural cooling to room temperature, collect the precipitate by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 10 minutes. Wash sequentially with deionized water and ethanol three times each to remove impurities.

Drying: Dry the product at 80°C for 12 hours in a vacuum oven to obtain BaTiO₃ nanoparticles.

Post-annealing (Optional): For enhanced crystallinity, anneal the powder at 500-700°C for 2 hours in a muffle furnace (heating rate: 5°C/min) [45].

Critical Parameters and Optimization

The hydrothermal-assisted sol-gel process is highly dependent on several critical parameters that significantly influence the final material properties:

Temperature Effects: Crystallite size and phase composition show strong temperature dependence. For BaTiO₃ synthesis, temperatures between 180-200°C typically yield particles with mean sizes of 120-180 nm, while higher temperatures (220°C) produce larger crystals (300-600 nm) with a peak distribution at 480 nm [45].

Reaction Time: Optimal crystallization generally occurs between 12-24 hours. Shorter durations may result in incomplete crystallization, while extended periods can promote excessive particle growth and agglomeration.

pH Control: The acidity of the precursor solution significantly affects hydrolysis rates. A slightly acidic medium (pH ≈ 4) typically provides optimal conditions for barium titanate formation, controlling both reaction kinetics and final stoichiometry.

Solvent Selection: Solvent properties including boiling point, viscosity, and polarity directly influence particle morphology and surface area. High boiling point solvents with greater viscosity (e.g., PEG-200) slow evaporation, promote nucleation over crystal growth, and minimize agglomeration, resulting in higher surface area materials [19].

Table 1: Optimization Parameters for Hydrothermal-Assisted Sol-Gel Synthesis

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Influence on Product | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 180-220°C | Determines crystallite size and phase purity | Higher temperature → larger crystals |

| Time | 12-48 hours | Affects crystallinity and particle growth | Beyond 24h → minimal size increase |

| pH | 3-5 (acidic) | Controls hydrolysis and condensation rates | Affects stoichiometry in multi-component systems |

| Solvent Type | PEG, EG, Alcohols | Impacts morphology and surface area | High boiling point solvents reduce agglomeration |

| Filling Degree | 70-80% | Influences autogenous pressure | Critical for safety and reproducibility |

Characterization and Performance Evaluation

Comprehensive characterization of hydrothermally synthesized photocatalysts is essential for correlating synthetic parameters with functional properties:

Structural Analysis: X-ray diffraction (XRD) confirms phase formation and crystallinity. For BaTiO₃, the tetragonal phase is characterized by splitting of (002)/(200) peaks at 2θ ≈ 45°. Rietveld refinement provides quantitative phase analysis and crystal structure information [45].

Morphological Examination: Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) reveals particle size distribution, morphology, and degree of agglomeration. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) provides detailed information on crystal structure, lattice fringes, and defects.

Surface Area and Porosity: Nitrogen adsorption-desorption analysis determines specific surface area (BET method), pore size distribution, and total pore volume. BaTiO₃ synthesized via hydrothermal-assisted sol-gel typically exhibits surface areas of 10-50 m²/g, with mesoporous characteristics [19].

Optical Properties: UV-Vis diffuse reflectance spectroscopy determines band gap energy through Tauc plot analysis. BaTiO₃ typically shows a band gap of approximately 3.2-3.4 eV, suitable for UV-light-driven photocatalysis.

Photocatalytic Performance: Methylene blue (MB) degradation under UV light irradiation serves as a standard test for photocatalytic activity. BaTiO₃ synthesized using PEG-200 as solvent demonstrated complete MB degradation within 30 minutes, attributed to its high surface area (9.78 m²/g) and optimal pore structure [19].

Microwave-Assisted Sol-Gel Synthesis

Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

Microwave-assisted sol-gel synthesis utilizes microwave radiation as an energy source to drive the sol-gel process, offering significantly reduced reaction times, enhanced reaction kinetics, and improved product homogeneity compared to conventional heating methods. The fundamental principle involves the interaction of microwave electromagnetic radiation with polar molecules and charged particles in the reaction mixture, leading to rapid, volumetric heating through dipole rotation and ionic conduction mechanisms [43] [44].

The microwave effect extends beyond mere thermal acceleration, potentially influencing reaction pathways through specific non-thermal effects. The rapid and uniform heating minimizes thermal gradients, leading to more homogeneous nucleation and growth conditions. This results in narrower particle size distributions, controlled morphology, and in some cases, unique metastable phases not easily accessible through conventional heating methods. For photocatalyst synthesis, these characteristics translate to materials with enhanced surface activity and improved charge carrier dynamics [47] [44].

Experimental Protocol: Fe₂O₃@TiO₂ Core-Shell Nanocomposite Synthesis

Materials and Reagents:

- Iron (III) oxide nanoparticles (Fe₂O₃, 12-75 nm)

- Titanium tetra-n-butoxide (Ti(C₄H₉O)₄, reagent grade, ≥97%)

- Ethanol absolute (≥99%)

- Ammonia solution (NHâ‚„OH, 28%)

- Deionized water (resistivity ≥18 MΩ·cm)

Procedure:

- Core Dispersion Preparation: Disperse 0.5 g commercial Fe₂O₃ nanoparticles in 100 mL ethanol using ultrasonic bath treatment for 30 minutes to achieve a homogeneous suspension.

Titanium Precursor Solution: In a separate container, mix 0.1 mol titanium tetra-n-butoxide with 50 mL ethanol under continuous stirring. Add 5 mL deionized water dropwise to initiate partial hydrolysis.

Coating Process: Slowly add the titanium precursor solution to the Fe₂O₃ dispersion with vigorous mechanical stirring (800 rpm). Simultaneously, add ammonia solution (2 mL) to maintain pH ≈ 9, catalyzing the condensation reaction.

Microwave Irradiation: Transfer the reaction mixture to a microwave-compatible reaction vessel. Irradiate using a microwave synthesis system at 300 W, maintaining temperature at 80°C for 20-30 minutes. Use magnetic stirring (500 rpm) throughout the irradiation process to ensure uniform heating [43].

Product Recovery: After microwave treatment, cool the mixture to room temperature. Recover the product by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 15 minutes.

Washing and Purification: Wash the precipitate sequentially with deionized water and ethanol three times each to remove unreacted precursors and byproducts.

Drying and Annealing: Dry the product at 80°C for 12 hours in a vacuum oven. For enhanced crystallinity of the TiO₂ shell, anneal at 450°C for 2 hours in air (heating rate: 3°C/min) [43].

Advanced Protocol: Microwave-Assisted Vacuum Synthesis of TiOâ‚‚

For specialized applications requiring high crystallinity and controlled particle size, microwave-assisted vacuum synthesis offers distinct advantages:

Materials:

- Titanium tetraisopropoxide (Ti(O-iPr)â‚„, technical grade)

- Hydrochloric acid (HCl, 32% in water)

- Triton X-100 (laboratory grade)

- Isopropanol (technical grade)

- Bi-distilled water

Procedure:

- Acidic Mixture Preparation: Combine 77 mL of an acidic mixture containing HCl (3.100%), bi-distilled water (96.887%), and Triton X-100 (0.013%).

Precursor Addition: Add 25 mL Ti(O-iPr)â‚„ dropwise over 5 minutes to the acidic mixture under mechanical stirring (600 rpm).

Microwave-Vacuum Processing: Transfer the mixture to a modified microwave system equipped with vacuum distillation capability. Apply vacuum (approximately 10â»Â³ torr) and irradiate with microwave at maximum power of 500 W. Maintain temperature at 60-70°C for 25-40 minutes [44].

Product Collection: Depending on process duration, the product may be obtained as a thick white gel or dry powder. For powdered products, resuspend in bi-distilled water to achieve 6 wt% concentration of TiOâ‚‚.

Characterization: The resulting TiOâ‚‚ nanoparticles typically exhibit crystalline anatase phase with photocatalytic activity comparable to commercial standards [44].

Critical Parameters and Optimization

Microwave-assisted sol-gel synthesis requires careful control of several parameters to achieve reproducible results with desired properties:

Microwave Power and Irradiation Time: Optimal power levels (300-500 W) and irradiation times (20-40 minutes) depend on the specific material system. Excessive power or prolonged irradiation can lead to particle agglomeration and structural defects.

Temperature Control: Precise temperature monitoring is essential, as microwave heating can rapidly elevate temperatures beyond desired setpoints. Use vessels with integrated temperature sensors for real-time monitoring.

Pressure Conditions: Conventional microwave synthesis operates at atmospheric pressure, while advanced implementations may utilize vacuum or controlled pressure conditions to manipulate reaction kinetics and solvent evaporation rates [44].

Precursor Concentration and Solvent Selection: Higher precursor concentrations generally yield larger particles, while solvent polarity directly affects microwave absorption efficiency and heating rates.

Table 2: Optimization Parameters for Microwave-Assisted Sol-Gel Synthesis

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Influence on Product | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microwave Power | 300-500 W | Affects crystallization kinetics and particle size | Higher power → faster crystallization |

| Irradiation Time | 20-40 minutes | Determines crystallinity and phase purity | Material-dependent optimization required |

| Temperature | 60-80°C | Controls reaction rate and nucleation density | Critical for metastable phase formation |