Single-Agent vs. Multi-Agent AI Systems for Data Extraction: A Strategic Guide for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of single-agent and multi-agent AI systems for data extraction, specifically tailored for researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development.

Single-Agent vs. Multi-Agent AI Systems for Data Extraction: A Strategic Guide for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of single-agent and multi-agent AI systems for data extraction, specifically tailored for researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development. It covers the foundational principles of both architectures, explores methodological approaches and real-world applications in biomedical contexts like clinical trial data processing, addresses key troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and presents a rigorous validation framework for comparing performance against traditional methods. The guide synthesizes current evidence to help research teams make informed, strategic decisions on implementing AI for enhancing the accuracy and efficiency of evidence synthesis and data extraction workflows.

Understanding AI Agent Architectures: From Single Actors to Collaborative Teams

In the field of artificial intelligence, particularly for data-intensive research tasks, the choice between a Single-Agent System (SAS) and a Multi-Agent System (MAS) represents a fundamental architectural decision. A Single-Agent System operates as a unified entity, handling all aspects of a task from start to finish using a single reasoning engine, typically a Large Language Model (LLM) [1]. In contrast, a Multi-Agent System functions as a collaborative team, where multiple autonomous AI agents, each with potential specializations, work together by dividing a complex problem into manageable subtasks [2] [3].

For researchers in fields like drug development, understanding this distinction is critical. The core difference lies in the approach to problem-solving: a single agent maintains a continuous, sequential thread of thought, while multiple agents leverage parallel execution and specialized skills to tackle problems that are too complex for a single entity [4]. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these two paradigms to inform the design of AI systems for data extraction and scientific research.

Core Architectural Comparison

The architectural differences between single and multi-agent systems directly impact their capabilities, performance, and suitability for various research tasks. The table below summarizes their core characteristics.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Single-Agent vs. Multi-Agent Systems

| Aspect | Single-Agent System (SAS) | Multi-Agent System (MAS) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Architecture | A "single process" or unified entity [1]. | A team of collaborating autonomous agents [3]. |

| Execution Model | Sequential; completes step A before moving to step B [1]. | Parallel; multiple subtasks can be handled simultaneously [1] [2]. |

| Context Management | Unified, continuous context with no loss between steps [1]. | Distributed; complex sharing required, with each agent often having a context subset [1]. |

| Coordination Needs | None needed internally [1]. | Critical; requires protocols for communication and collaboration to avoid conflict [1] [5]. |

| Inherent Strength | Context continuity and high reliability [1]. | Parallel processing, scalability, and the ability to specialize [1] [3]. |

| Primary Challenge | Context window limits and sequential bottlenecks [1]. | Context fragmentation, coordination complexity, and potential for unpredictable behavior [1] [5]. |

Operational Workflows

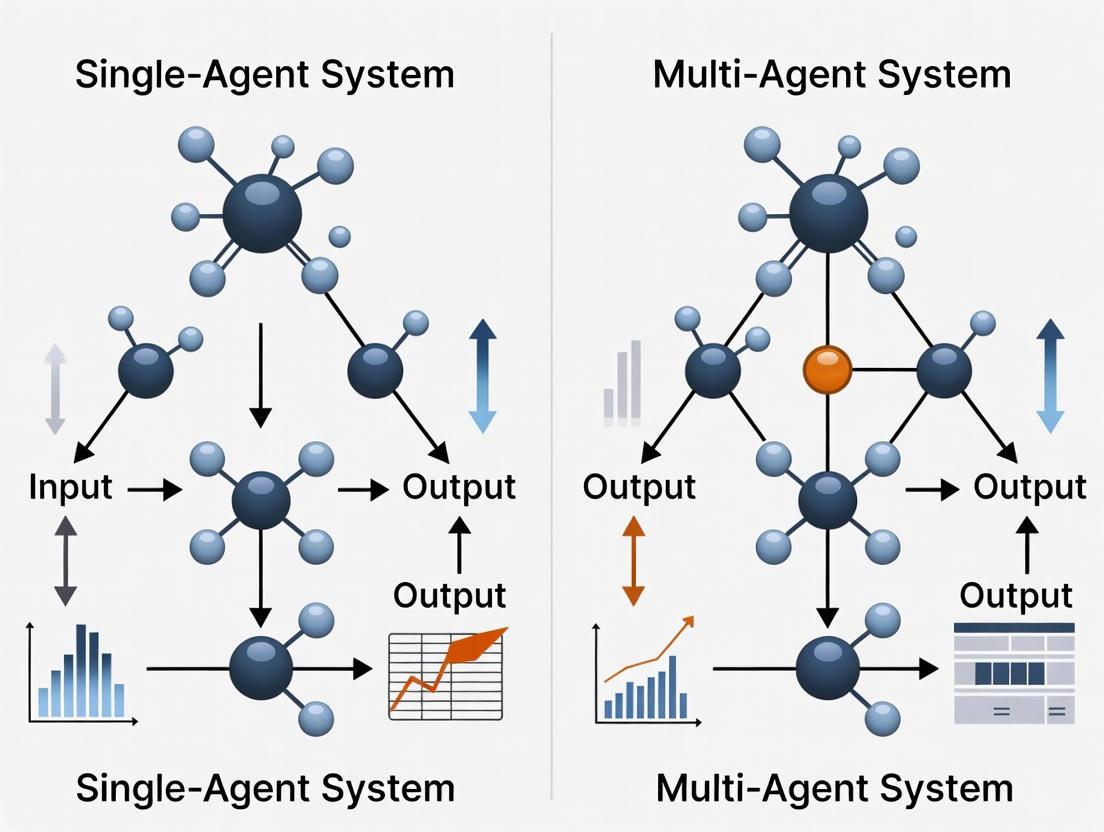

The logical flow of each system type dictates its operational strengths and weaknesses. The following diagrams illustrate the fundamental workflows for each architecture.

Diagram 1: Single-Agent System Sequential Workflow

Diagram 2: Multi-Agent System Collaborative Workflow

Quantitative Performance Analysis

Empirical studies and industry benchmarks provide critical insights into the practical performance of each system architecture. Key quantitative differences are summarized below.

Table 2: Empirical Performance and Cost Comparison

| Performance Metric | Single-Agent System (SAS) | Multi-Agent System (MAS) | Data Source & Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Token Usage | ~4x a standard chat interaction [1]. | ~15x a standard chat interaction [1]. | Measured by Anthropic, highlighting higher computational cost for MAS. |

| Relative Accuracy | Superior for tasks within advanced LLM capabilities [6]. | 1.1% - 12% higher accuracy for certain complex applications [6]. | An extensive empirical study found MAS advantages are task-dependent and diminishing with newer LLMs. |

| Deployment Cost | Lower inference cost [4]. | Potentially higher due to multiple LLM calls [4]. | Industry observation; cost scales with agent count and interaction complexity. |

| Response Latency | Lower response time [4]. | Potentially higher due to sequential agent hand-offs [4]. | Industry observation; parallel execution can mitigate this in some workflows. |

| Reliability & Debugging | High predictability; straightforward debugging [1]. | Lower predictability; complex debugging due to emergent behaviors [1]. | Inherent characteristic related to system architecture. |

Key Experimental Findings and Protocols

Recent research underscores that the performance gap between SAS and MAS is dynamic and highly dependent on the underlying LLM capabilities and task structure.

- Diminishing MAS Advantage with Advanced LLMs: A 2025 empirical study comparing SAS and MAS across various applications found that the performance benefits of multi-agent systems diminish as the capabilities of the core LLMs improve [6]. Frontier models like OpenAI-o3 and Gemini-2.5-Pro, with their advanced long-context reasoning and memory retention, can mitigate many limitations that originally motivated complex MAS designs [6].

- The "More Agents" Scaling Law: Contrary to the above, research from Tencent (2024) demonstrated that for certain problem types, simply scaling the number of agents in an ensemble leads to consistently better performance. This "Agent Forest" method uses a sampling phase (generating multiple responses from different agent instances) followed by a voting phase (selecting the best response via majority vote or similarity scoring). The study found that performance scales with agent count, and smaller models with more agents can sometimes outperform larger models with fewer agents [7].

- Hybrid Architectures for Optimal Performance: The same 2025 study proposed and validated a hybrid agentic paradigm, "request cascading," which dynamically routes tasks between SAS and MAS based on complexity [6]. This design was shown to improve accuracy by 1.1-12% while reducing deployment costs by up to 20% across various applications, suggesting that a flexible, non-dogmatic approach is often most effective [6].

The Researcher's Toolkit: System Implementation

Building and testing either type of agentic system requires a robust set of tools and methodologies, especially for high-stakes research applications.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for Building and Evaluating AI Agents

| Component / Tool | Category | Function in Research & Development |

|---|---|---|

| LLMs (GPT-4, Claude, PaLM, LLaMA) [5] | Core Reasoning Engine | Provides the fundamental reasoning, planning, and natural language understanding capabilities for each agent. Model choice balances cost, performance, and safety. |

| Simulation Test Environment [8] | Validation Framework | Provides a controlled, reproducible, and adjustable environment to test agent behaviors and interactions safely before real-world deployment. |

| Orchestrator Frameworks [7] | Coordination Software | Manages overall workflow, routes tasks between specialized agents, and synthesizes final outputs (e.g., Microsoft's Magentic-One). |

| Quantitative Metrics [8] | Performance Measure | Tracks key performance indicators (KPIs) like response time, throughput, task success rate, and communication overhead. |

| Docker & Virtual Envs [7] | Deployment Infrastructure | Provides containerized and secure environments for executing agents, especially when tools or code execution are required. |

| Structured Communication [3] | Agent Interaction Protocol | Enables reliable data exchange between agents using standardized formats like JSON over HTTP or gRPC. |

| Ethyl 6-nitropicolinate | Ethyl 6-nitropicolinate, MF:C8H8N2O4, MW:196.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 7-Fluoro-4-methoxyquinoline | 7-Fluoro-4-methoxyquinoline, MF:C10H8FNO, MW:177.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Protocol for System Testing and Validation

Rigorous testing is paramount for deploying reliable agentic systems in research. A structured, three-level methodology is recommended [8]:

- Unit Testing: Validate each agent's decision-making and behavior in isolation. Checks include correct rule-following and handling of unexpected inputs [8].

- Integration Testing: Run small groups of agents together to verify effective communication, deadlock avoidance, and correct shared outcomes [8].

- System Testing: Evaluate the full system under realistic conditions. Measure performance metrics and observe for coordination breakdowns. This stage should include stress tests, such as introducing communication failures or erroneous agent information, to validate system resilience and graceful recovery [8].

The choice between single and multi-agent systems is not a matter of one being universally superior. Instead, it is a strategic decision based on the nature of the research task, available resources, and required reliability [1] [4].

- Use a Single-Agent System when tasks are primarily sequential, state-dependent, and well-defined. Examples include refactoring a codebase, writing a detailed document, or performing a straightforward data extraction task where context continuity is paramount [1]. This architecture offers simplicity, reliability, and lower cost.

- Use a Multi-Agent System when faced with highly complex, multi-faceted problems that benefit from parallel execution and role specialization. Examples include broad market research, analyzing a complex scientific problem requiring multiple areas of expertise, or building a system that requires internal validation loops [1] [4]. This architecture provides scalability and the potential for higher accuracy on suitably complex tasks but at the cost of greater complexity and resource consumption.

The future of agentic systems in research appears to be moving toward flexible, hybrid models [6]. As a foundational 2025 study concluded, the question is not "SAS or MAS?" but rather a pragmatic "How can we best combine these paradigms?" [6]. The emerging hybrid paradigm, which dynamically selects the most efficient architecture per task, has already demonstrated significant improvements in both accuracy and cost-effectiveness, offering a promising path forward for data extraction and scientific research applications [6].

For researchers in drug development and data extraction, the choice between a single-agent and a multi-agent AI system is architectural. The performance, scalability, and reliability of research automation hinge on how effectively the core components of an AI agent—Planning, Memory, Tools, and Action—are implemented and orchestrated [9] [10]. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these two paradigms, focusing on their application in complex data extraction and research tasks. We break down the architectural components, present quantitative performance data, and detail experimental protocols to inform your research and development decisions.

Architectural Blueprint: Core Components of an AI Agent

Every AI agent, whether operating alone or in a team, is built upon a foundational architecture. Understanding these core components is essential for diagnosing performance and making informed design choices.

The Five-Layer Architecture

A typical AI agent architecture consists of five integrated layers that enable it to operate autonomously [9]:

- Perception: This is the agent's interface to the external world. It gathers and interprets raw data from its environment, which for a digital agent could be a user query, data from an API, or a document stream. The module processes this data into a standardized, usable format for subsequent layers [9] [10].

- Memory: This layer enables the agent to retain information across interactions. Short-term memory maintains the immediate context of an ongoing task or conversation, while long-term memory acts as a knowledge base, storing historical data, user preferences, and past experiences for recall in future sessions [9] [10]. Modern agents often use vector databases (e.g., Pinecone, FAISS) to store and semantically search embeddings of multimodal data [9].

- Reasoning & Decision-Making (Planning): This is the cognitive engine of the agent. Here, the Large Language Model (LLM) interprets the processed input from the Perception layer, consults Memory, and engages in Planning. It breaks down high-level goals into a sequence of actionable steps, makes strategic decisions, and determines the optimal path to achieve its objective [9] [10].

- Action & Execution: This layer translates decisions into outcomes. The agent executes its plan by interacting with external systems. This can involve calling APIs, running scripts, generating text, controlling software, or, in the case of physical agents, operating actuators [9] [10].

- Feedback Loop (Learning): This final layer enables the agent to learn and improve over time. It evaluates the outcomes of its actions through methods like reinforcement learning (rewarding success), human-in-the-loop feedback, or self-critique. The insights gained are used to update the agent's models and strategies for future tasks [9] [10].

Visualizing the Agent Architecture

The following diagram illustrates the continuous loop of information and decision-making through these five core layers.

Single-Agent vs. Multi-Agent Systems: A Comparative Analysis

The core architectural components manifest differently in single-agent and multi-agent systems, leading to distinct performance and capability profiles.

Defining the Paradigms

- Single-Agent System: A monolithic architecture where one intelligent agent handles the entire task lifecycle—from ingesting inputs and reasoning to using tools and generating outputs [11]. It manages its own memory, state, and connections to external tools or APIs.

- Multi-Agent System (MAS): A coordinated ecosystem of multiple specialized AI agents working together to achieve a shared goal [12]. A key feature is an orchestrator (or supervisor) that breaks down complex problems, delegates subtasks to specialized agents, and synthesizes their results, creating a form of "collective intelligence" [13] [11].

Performance and Characteristic Comparison

The table below summarizes the objective differences between the two paradigms, based on documented use cases and industry reports.

Table 1: Objective Comparison of Single-Agent vs. Multi-Agent Systems

| Criteria | Single-Agent System | Multi-Agent System |

|---|---|---|

| Architectural Core | Monolithic agent managing all components [11]. | Specialized agents for sub-tasks, coordinated by an orchestrator [13] [12]. |

| Task Complexity | Best for well-defined, linear tasks (e.g., simple Q&A, email summarization) [11]. | Excels at multidimensional problems (e.g., financial analysis, predictive maintenance) [12]. |

| Development & Cost | Faster to implement, lower initial cost, simpler debugging [12] [11]. | Complex to orchestrate, requires more technical expertise and computational resources [12] [11]. |

| Fault Tolerance | Single point of failure; agent failure halts the entire system [11]. | Inherent resilience; failure of one agent can be mitigated by others [13] [11]. |

| Scalability | Struggles with complex, scalable tasks; adding capabilities increases agent complexity exponentially [11] [14]. | Highly scalable and modular; agents can be optimized and added independently [13] [12]. |

| Typical Use Cases | Personal assistant, specialized chatbot, simple task automation [12] [11]. | Supply chain optimization, multi-criteria financial analysis, automated research [12] [15]. |

Quantitative Performance Data

Controlled experiments and internal industry evaluations provide measurable evidence of the performance differences. The following table compiles key quantitative findings.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data

| Metric | Single-Agent Performance | Multi-Agent Performance | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Research Task Accuracy | Baseline | 90.2% improvement over single-agent baseline [15]. | Anthropic's internal eval: Multi-agent (Claude Opus + Sonnet) vs. single-agent (Claude Opus) on a research task [15]. |

| Contract Review Efficiency | Baseline | 60% reduction in review time [13]. | Law firms automating contract review with multi-agent systems [13]. |

| Operational Efficiency | Baseline | 35% reduction in unplanned downtime; 28% optimization in maintenance costs [12]. | Industrial predictive maintenance using multi-agent systems [12]. |

| Resource Consumption (Tokens) | Baseline (Chat) | ~15x more tokens than chat interactions [15]. | Anthropic's measurement of token usage in multi-agent research systems [15]. |

Experimental Protocols for Architectural Comparison

To validate the claims in Table 2 and objectively compare architectures, researchers can adopt the following experimental protocols.

Protocol 1: Multi-Agent Research Eval (Based on Anthropic)

This protocol tests the system's ability to handle complex, breadth-first research queries [15].

- Objective: To compare the accuracy and completeness of information retrieved by single-agent and multi-agent systems for a query requiring parallel information gathering.

- Task: "Identify all the board members of the companies in the Information Technology S&P 500."

- Experimental Groups:

- Group A (Single-Agent): A single, powerful LLM (e.g., Claude Opus) operates in a loop, using search tools sequentially.

- Group B (Multi-Agent): An orchestrator (Claude Opus) analyzes the query, spawns multiple sub-agents (Claude Sonnet) to research different companies in parallel, and synthesizes the findings.

- Metrics:

- Accuracy: Percentage of correctly identified board members.

- Completeness: Percentage of S&P 500 IT companies for which at least one board member was found.

- Token Usage: Total tokens consumed to complete the task.

- Methodology:

- A ground truth dataset of board members is established.

- Each system executes the task in a controlled environment with access to the same search tools.

- The final output is compared against the ground truth for accuracy and completeness.

- Token usage is logged for cost-efficiency analysis.

Protocol 2: Document Processing and Data Extraction Eval

This protocol measures efficiency in a key data extraction research scenario.

- Objective: To compare the time and accuracy of single-agent and multi-agent systems in processing complex documents and extracting specific data points.

- Task: Analyze a 100-page pharmaceutical research report to extract all drug compound names, associated trial phases, and primary efficacy endpoints.

- Experimental Groups:

- Group A (Single-Agent): A single agent processes the entire document sequentially.

- Group B (Multi-Agent): A system with specialized agents: a

document_parser, adata_extraction_agent(for compound names and endpoints), avalidation_agent(to check for consistency), and asummary_agent[13].

- Metrics:

- Time-to-Completion: Total time from task start to final output.

- F1 Score: Harmonic mean of precision and recall for extracted data points.

- Error Rate: Percentage of incorrectly extracted or hallucinated data points.

- Methodology:

- A set of annotated documents serves as the benchmark.

- Systems process the documents, and their outputs are captured.

- Extracted data is automatically and manually compared to the benchmark to calculate F1 score and error rate.

- Execution time is measured from the first agent call to the final output.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Components for Replication

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for AI Agent Experimentation

| Item | Function in Experiment | Example Tools / Frameworks |

|---|---|---|

| Orchestration Framework | Manages workflow logic, agent communication, and task delegation in multi-agent systems. | LangGraph, CrewAI, AutoGen [13] [11] |

| Core LLM(s) | Serves as the reasoning engine for agents. Different models can be used for orchestrators and specialized workers. | GPT-4, Claude Opus/Sonnet, Llama [15] |

| Memory Layer | Provides short-term and long-term memory for agents to retain context and knowledge. | Redis (short-term), Vector Databases (Pinecone, Weaviate) [9] [11] |

| Tool & API Protocol | Standardizes and secures agent access to external tools, databases, and APIs. | Model Context Protocol (MCP) [16] |

| Evaluation Framework | Provides metrics and tools to quantitatively assess agent performance, accuracy, and cost. | Custom eval scripts, TruLens, LangSmith |

| 1-Octadecenylsuccinic Acid | 1-Octadecenylsuccinic Acid, MF:C22H40O4, MW:368.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 4-Glycylphenyl benzoate hcl | 4-Glycylphenyl benzoate hcl, MF:C15H14ClNO3, MW:291.73 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualizing Multi-Agent System Workflows

The performance advantages of multi-agent systems stem from their orchestrated workflows. The following diagram illustrates the orchestrator-worker pattern used in advanced research systems.

The architectural breakdown confirms that the choice between single and multi-agent systems is not a matter of superiority, but of strategic fit. For researchers and drug development professionals, the decision matrix is clear:

- Choose a single-agent architecture for prototyping, simple data lookup tasks, or linear workflows where development speed and cost are primary constraints [11] [16].

- Choose a multi-agent architecture for complex data extraction research, analyzing multi-source documents, or any problem that requires parallel processing, domain specialization, and high reliability [13] [12] [15]. The quantitative data shows a significant performance uplift, albeit at a higher computational cost.

The future of automated research in scientific fields lies in leveraging the collective intelligence of multi-agent systems. As frameworks and models evolve, the cost of these systems is expected to decrease, making them an indispensable tool for accelerating discovery and innovation.

In the architectural landscape of artificial intelligence, the choice between single-agent and multi-agent systems represents a fundamental trade-off between simplicity and specialization. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals considering AI systems for data extraction research, single-agent systems offer a compelling proposition for well-defined, focused tasks. These systems employ one intelligent agent that handles the entire task lifecycle—from ingesting inputs and reasoning to tool use and output generation [11]. Unlike multi-agent approaches that distribute functionality across specialized subsystems, single-agent architectures maintain all context in one place, making them exceptionally suited for targeted applications where coordination overhead would otherwise diminish returns [17]. This guide objectively examines the performance characteristics of single-agent systems through experimental data and methodological analysis, providing a foundation for architectural decisions in research environments.

Performance Analysis: Quantitative Comparisons

Rigorous evaluation reveals distinct performance characteristics where single-agent systems demonstrate clear advantages in specific operational contexts. The following data synthesizes findings from controlled experiments and real-world implementations.

Table 1: System Performance Comparison in Specialized Tasks

| Performance Metric | Single-Agent System | Multi-Agent System | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Development Speed | Rapid implementation (hours to days) [11] | Extended development cycles | Prototyping workflows [17] [11] |

| Decision-making Latency | Faster direct decision-making [11] | Higher latency from inter-agent communication [17] | Time-sensitive research queries [11] |

| Implementation Time | 19% faster completion [18] | 19% slower completion [18] | Complex software development tasks [18] |

| System Reliability | Single point of failure [11] | Fault tolerance through agent redundancy [11] | High-availability research environments [11] |

| Debugging Complexity | Straightforward; single system to monitor [17] | Complex; requires tracing across multiple agents [17] | Error resolution in experimental workflows [17] |

Table 2: Architecture Suitability Analysis for Research Applications

| Research Task Profile | Single-Agent Recommendation | Performance Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Focused Data Extraction | Strong recommendation | Lower latency, maintained context [17] [11] |

| Multi-Domain Research Questions | Not recommended | Limited domain expertise [17] [19] |

| Rapid Prototyping | Strong recommendation | Faster development cycles [17] [11] |

| Complex Workflow Orchestration | Not recommended | Limited coordination capabilities [19] [11] |

| Targeted Literature Review | Strong recommendation | Unified context management [17] |

Controlled experimentation demonstrates that for experienced developers working on well-defined tasks, single-agent systems can provide significant efficiency advantages. A randomized controlled trial (RCT) with experienced open-source developers revealed that AI-assisted work using primarily single-agent approaches took 19% longer than unaided work, contradicting developer expectations of 24% speedup [18]. This surprising result highlights that single-agent performance advantages are context-dependent and do not automatically translate to all scenarios, particularly those requiring deep specialization [18].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Software Development Productivity RCT

Objective: Quantify the impact of single-agent AI assistance on implementation time for experienced developers working on familiar codebases [18].

Methodology:

- Participant Selection: 16 experienced developers from large open-source repositories (averaging 22k+ stars, 1M+ lines of code) with multi-year contribution histories [18]

- Task Selection: 246 real issues (bug fixes, features, refactors) valuable to the repository provided by developers [18]

- Randomization: Issues randomly assigned to AI-allowed or AI-disallowed conditions [18]

- AI Intervention: Developers used Cursor Pro with Claude 3.5/3.7 Sonnet (frontier models at study time) when allowed [18]

- Control: No generative AI assistance in disallowed condition [18]

- Measurement: Self-reported implementation time with screen recording verification [18]

- Compensation: $150/hour to ensure professional motivation [18]

Key Findings: Despite developer expectations of 24% speedup, single-agent AI assistance resulted in 19% longer implementation times across tasks averaging two hours each [18]. This performance pattern persisted across different outcome measures and estimator methodologies [18].

Legal Domain Task Specialization Study

Objective: Evaluate single-agent system performance on specialized legal tasks including legal information retrieval, question answering, and judgment prediction [19].

Methodology:

- Task Allocation: Single-agent systems assigned to focused legal tasks including legal information retrieval [20], legal question answering [19] [21] [11], and legal judgment prediction [21] [22]

- Performance Benchmarking: Comparison against multi-agent systems on complex, multi-faceted legal tasks [19]

- Analysis Metrics: Success rates, error types, context maintenance capabilities [19]

Key Findings: Single-agent systems demonstrated strong performance on focused legal tasks but showed limitations when faced with problems requiring diverse expertise or integrated reasoning [19]. Research literature significantly favors single-agent approaches in current implementations, reflecting their maturity for well-scoped applications [19].

Architectural Framework and Workflow

Single-agent systems employ streamlined architectures that consolidate functionality within a unified reasoning entity. The following diagram illustrates the core components and their interactions within a typical single-agent system for research applications:

Figure 1: Single-Agent Architecture for Research Tasks

The architectural workflow demonstrates how single-agent systems maintain unified context throughout task execution. The planning module serves as the central reasoning component that coordinates with memory, tools, and action modules without requiring inter-agent communication [19]. This integrated approach eliminates coordination overhead and maintains full context awareness throughout the task lifecycle [17].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Components

Successful implementation of single-agent systems for research tasks requires specific components optimized for focused performance. The following table details these essential elements and their functions in research environments.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Single-Agent Systems

| Component | Function | Research Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Planning Module | High-level reasoning and task decomposition [19] | Breaking down research questions into executable steps [19] |

| Memory Component | Maintains context and state across interactions [19] | Preserving research context throughout data extraction [17] [19] |

| Tool Integration | Provides access to external APIs and databases [11] | Connecting to research databases, scientific APIs [11] |

| Action Module | Executes tasks and generates outputs [19] | Delivering extracted data, summaries, or analyses [19] |

| Model Context Protocol | Standardized connection to data sources [11] | Unified access to research data repositories [11] |

| Thrombin Receptor Agonist | Thrombin Receptor Agonist, MF:C81H118N20O23, MW:1739.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Magl-IN-8 | MAGL Inhibitor Magl-IN-8 | Magl-IN-8 is a potent MAGL inhibitor for neurological disease, pain, and cancer research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Decision Framework for Research Applications

The following decision pathway provides a structured approach for researchers to evaluate when single-agent systems represent the optimal architectural choice:

Figure 2: Research Task Decision Pathway

This decision framework emphasizes that single-agent systems excel when tasks have narrow, well-defined scope and benefit from maintained contextual continuity [17]. For drug development professionals, this might include targeted literature extraction, focused data analysis from standardized experiments, or automated reporting on specific research metrics [17] [11].

Single-agent systems demonstrate unequivocal strengths for research tasks characterized by focused scope and requirements for contextual consistency. The experimental evidence indicates that these systems provide optimal performance when applied to problems matching their architectural strengths: lower latency, simplified debugging, reduced infrastructure overhead, and more straightforward maintenance [17]. For research organizations building AI capabilities for data extraction, single-agent systems represent the optimal starting point for most focused applications, with the potential to evolve toward multi-agent architectures only when tasks genuinely require diverse specialization [17] [11]. The experimental data reveals that performance advantages are context-dependent, requiring careful task analysis before architectural commitment [18]. For the research community, this evidence-based approach to system selection ensures that architectural complexity is introduced only when justified by clear functional requirements.

The automation of data extraction from complex scientific literature represents a critical challenge in accelerating research, particularly in fields like drug development and materials science. The central thesis of this guide is that for complex, multimodal data extraction tasks, multi-agent systems demonstrate marked advantages in precision, recall, and handling of complex contexts compared to single-agent systems, albeit with increased architectural complexity. The evolution of Large Language Models (LLMs) has powered both paradigms; single-agent systems utilize one powerful model to handle an entire task, while multi-agent systems decompose problems, delegating subtasks to specialized, coordinated agents [23] [24]. Recent empirical studies, including those in high-stakes domains like nanomaterials research, show that a multi-agent approach can significantly outperform even the most advanced single-model baselines by leveraging specialization, verification, and distributed problem-solving [6] [25]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these architectures, focusing on their performance in data extraction for research.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The following tables summarize key performance indicators and characteristics from experimental studies and real-world implementations, highlighting the comparative effectiveness of single-agent versus multi-agent systems.

Table 1: Experimental Performance in Scientific Data Extraction

| Metric | Single-Agent System (GPT-4.1) | Multi-Agent System (nanoMINER) | Context / Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average Precision | Lower than MAS [25] | Consistently Higher [25] | Extraction from nanomaterials literature [25] |

| Average Recall | Lower than MAS [25] | Consistently Higher [25] | Extraction from nanomaterials literature [25] |

| F1 Score | 35.6% (Previous SOTA model) [26] | 80.8% [26] | Benchmark dataset of multimodal chemical reaction graphics [26] |

| Data Similarity to Manual Curation | 65.11% [25] | Precision ≥ 0.96 for kinetic parameters [25] | Nanozyme data extraction [25] |

| Parameter Extraction Precision | Varies, struggles with implicit data [25] | Up to 0.98 for parameters like Km, Vmax [25] | Nanozyme characteristics [25] |

| Crystal System Inference | Limited capability shown [25] | High capability from chemical formulas alone [25] | Nanomaterial characteristics [25] |

Table 2: Architectural and Operational Characteristics

| Characteristic | Single-Agent Systems | Multi-Agent Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Core Architecture | One intelligent entity handles the entire task [23] [27] | Multiple specialized agents collaborate [23] [3] |

| Scalability | Limited; struggles with growing complexity [23] [27] | Highly scalable; agents can be added/removed [23] [3] |

| Fault Tolerance | Single point of failure [23] | Robust; failure of one agent doesn't collapse system [23] [28] |

| Decision-Making | Fast, centralized, but narrow perspective [23] [27] | Collective, slower, but broader perspective [23] [27] |

| Communication Overhead | None or low [23] | High; requires coordination protocols [23] [27] |

| Problem-Solving Capability | Restricted to one perspective/strategy [23] | Distributed, collaborative, multiple perspectives [23] [29] |

| Best Suited For | Simple, well-defined tasks in controlled environments [23] [27] | Complex, dynamic tasks requiring collaboration [23] [28] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The nanoMINER Multi-Agent Protocol for Nanomaterial Data Extraction

A landmark 2025 study published in npj Computational Materials detailed the nanoMINER system, providing a rigorous protocol for comparing multi-agent and single-agent performance in extracting structured data from scientific literature on nanomaterials [25].

1. Objective: To automatically assemble datasets of nanomaterial and nanozyme properties from unstructured research articles and supplementary materials with precision rivaling manual curation by domain experts [25].

2. Agent Architecture and Workflow:

- Main (ReAct) Agent: Orchestrates the workflow, initialized with tools for text, image, and data extraction. It processes the full article text and coordinates with specialized agents [25].

- NER Agent: Based on a fine-tuned Mistral-7B or Llama-3-8B model, this agent extracts specific named entities (e.g., chemical formulas, properties) from the segmented text [25].

- Vision Agent: Leverages GPT-4o and a YOLO model to detect and interpret figures, tables, and schemes within the PDF, converting visual information into structured data [25].

3. Experimental Procedure:

- PDF Processing: Input documents are processed to extract raw text, images, and plots [25].

- Text Segmentation: The article text is split into chunks of 2048 tokens for efficient processing [25].

- Agent Coordination: The Main agent delegates tasks. The NER agent scans text segments, while the Vision agent analyzes visual data [25].

- Information Aggregation: The Main agent aggregates outputs from all agents, reconciles information from different modalities, and generates the final structured output [25].

- Benchmarking: The system's performance was benchmarked against strong baselines, including the multimodal GPT-4.1 and reasoning models (o3-mini, o4-mini), using standard precision, recall, and F1 scores on a manually curated gold-standard dataset [25].

Protocol for Comparative Performance Analysis

A separate extensive empirical study directly compared MAS and SAS across various agentic applications [6].

- Objective: To evaluate if the benefits of MAS over SAS diminish as the capabilities of frontier LLMs improve [6].

- Methodology: The study conducted head-to-head comparisons of MAS and SAS implementations on popular agentic tasks, measuring accuracy and deployment costs [6].

- Key Finding: The study confirmed the superior accuracy of MAS but also found that the performance gap narrows with more advanced base LLMs. This insight motivated the design of a hybrid "request cascading" paradigm, which dynamically chooses between SAS and MAS to optimize both efficiency and capability [6].

System Workflow Visualization

The fundamental difference between single-agent and multi-agent architectures lies in their workflow and coordination. The following diagram illustrates the comparative workflows of both systems in a data extraction pipeline.

Figure 1. Data Extraction Workflow: Single-Agent vs. Multi-Agent Systems. The Single-Agent System (top) uses one model for the entire task. The Multi-Agent System (bottom) uses an orchestrator to delegate subtasks to specialized agents (e.g., for text and vision), followed by aggregation and validation [23] [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Frameworks and Models

Implementing these systems requires a selection of software frameworks and models. The table below details key "research reagent solutions" for building single or multi-agent data extraction systems.

Table 3: Key Tools and Frameworks for Building AI Agent Systems

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Data Extraction Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| AutoGen [29] | Multi-Agent Framework | Creates conversable AI agents that can work together and use tools. | Enables building collaborative agent teams for complex, multi-step extraction tasks. |

| CrewAI [28] [29] | Multi-Agent Framework | Orchestrates role-playing AI agents in a structured team. | Ideal for defining clear agent roles (e.g., "NER Specialist," "Data Validator"). |

| LangGraph [28] [29] | Multi-Agent Framework | Models agent interactions as stateful, cyclic workflows. | Manages complex, non-linear extraction pipelines where agent steps may loop. |

| GPT-4o / GPT-4.1 [25] | Multimodal LLM | Powers agents with strong reasoning and multimodal understanding. | Serves as a powerful base LLM for single agents or multiple agents in a MAS. |

| Llama-3-8B / Mistral-7B [25] | Foundational LLM | Provides capable, smaller-scale language understanding. | Can be fine-tuned for specific, cost-effective NER agent tasks within a MAS. |

| YOLO Model [25] | Computer Vision Tool | Detects and classifies objects within images and figures. | Used by a dedicated Vision Agent to extract data from charts and diagrams in papers. |

| Azure AI Foundry [3] | Production Platform | Builds and orchestrates specialized AI agents in long-running workflows. | Provides an enterprise-grade platform for deploying research extraction agents. |

| Jervinone | Jervinone, CAS:469-60-3, MF:C27H37NO3, MW:423.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Egfr/aurkb-IN-1 | EGFR/AURKB-IN-1|Dual Kinase Inhibitor|For Research | Bench Chemicals |

The empirical data and experimental protocols presented confirm the core thesis: multi-agent systems offer a powerful paradigm for complex data extraction in research. Their strength lies in specialization, validation through multi-step reasoning, and robustness derived from distributed problem-solving [28] [25]. While single-agent systems remain a valid choice for simpler, well-defined tasks due to their simplicity and lower computational overhead [23] [6], the comparative evidence shows that multi-agent systems consistently achieve higher precision and recall on complex, multimodal scientific extraction tasks [26] [25]. For researchers and drug development professionals aiming to automate the curation of high-quality datasets from the vast scientific literature, the multi-agent approach, implemented with the modern toolkit described, represents the current state-of-the-art. The emerging trend of hybrid systems that dynamically leverage both architectures promises to further enhance efficiency and capability in the future [6].

In the field of AI-driven data extraction, the choice between centralized (single-agent) and distributed (multi-agent) decision-making architectures represents a critical strategic decision for research and drug development professionals. These competing paradigms offer distinct trade-offs in control, efficiency, and adaptability that directly impact research outcomes and operational scalability. Centralized systems feature a single point of control where all decisions are processed through one authoritative agent, ensuring consistency but potentially creating bottlenecks [30] [31]. Conversely, distributed systems decentralize authority across multiple specialized agents, enabling parallel processing and localized decision-making while introducing coordination complexity [1] [32].

The relevance of these architectural patterns extends directly to scientific domains such as drug discovery, where automated research systems must process vast biomedical literature databases, experimental data, and clinical trial results. Understanding the fundamental characteristics, performance metrics, and implementation requirements of each approach allows research teams to align their AI infrastructure with specific project goals, whether prioritizing rigorous protocol adherence or exploratory data analysis.

Defining the Architectural Paradigms

Centralized (Single-Agent) Systems

Centralized decision-making architectures operate through a unified control point where a single agent maintains authority over all processing decisions and actions. This model functions as an integrated specialist that handles complex, state-dependent tasks through sequential execution, maintaining a continuous context throughout operations [1]. In practice, this might manifest as a singular AI agent responsible for end-to-end data extraction from scientific literature, maintaining consistent interpretation standards across all processed documents.

The defining characteristic of centralized systems is their stateful architecture, where early decisions directly inform subsequent actions without requiring inter-process communication [1]. This continuity proves particularly valuable for "write" tasks such as generating consolidated research reports or maintaining standardized data formats across multiple extractions. The unified context management ensures that information remains consistent without fragmentation across specialized subsystems, though this benefit becomes constrained as tasks approach the limits of the system's context window [1].

Distributed (Multi-Agent) Systems

Distributed decision-making architectures deploy multiple specialized agents that operate both independently and collaboratively, typically coordinated through a lead agent that decomposes objectives and synthesizes outputs [1]. This structure mirrors a research team with domain specialists, where different agents might separately handle literature retrieval, data normalization, evidence grading, and synthesis before integrating their findings.

This paradigm excels at "read" tasks that benefit from parallel execution, such as simultaneously analyzing multiple research databases or processing disparate data sources [1] [33]. The distributed context model allows each agent to operate with specialized instructions and tools, though this requires deliberate engineering to ensure proper information sharing between components [1]. The architectural flexibility supports both hierarchical coordination with a lead agent and swarm intelligence approaches with more peer-to-peer collaboration, each presenting distinct management challenges and opportunities for emergent problem-solving behaviors [1].

Comparative Analysis: Performance Trade-offs

The choice between centralized and distributed architectures involves measurable trade-offs across multiple performance dimensions. The following table synthesizes key comparative metrics based on documented implementations and experimental observations:

Table 1: Architectural Performance Comparison for Data Extraction Tasks

| Performance Dimension | Centralized (Single-Agent) Systems | Distributed (Multi-Agent) Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Context Management | Continuous, unified context with no information loss between steps [1] | Complex sharing required, risk of context fragmentation across agents [1] |

| Execution Speed | Sequential processing creates bottlenecks for parallelizable tasks [1] | Parallel execution significantly reduces latency for multi-faceted problems [1] |

| Computational Resources | ~4x chat tokens (baseline) [1] | ~15x chat tokens due to inter-agent communication [1] |

| Reliability & Predictability | High, with straightforward execution paths and deterministic behaviors [1] | Lower, with emergent behaviors and non-deterministic interactions [1] |

| Debugging & Maintenance | Transparent decision trails and simpler testing procedures [1] | Complex, non-deterministic patterns requiring advanced observability tools [1] |

| Scalability | Limited by central processing capacity and context window size [31] [1] | Highly scalable through addition of specialized agents [31] [1] |

| Fault Tolerance | Single point of failure - central agent failure disrupts entire system [31] [32] | Resilient - failure of individual agents doesn't necessarily collapse system [31] [32] |

| Best Suited Tasks | Sequential, state-dependent "write" tasks (code generation, report writing) [1] | Parallelizable, exploratory "read" tasks (research, multi-source analysis) [1] |

These quantitative differences manifest distinctly in research environments. Centralized architectures provide superior performance for generating standardized extraction reports or maintaining consistent data formatting across documents, while distributed systems excel at comprehensive literature reviews that require simultaneous database queries and comparative analysis [1]. The significant difference in computational resource requirements (token usage) represents a direct cost-benefit consideration, with distributed systems offering accelerated processing at substantially higher computational expense [1].

Decision Framework: Selecting the Appropriate Architecture

Task Characteristics Analysis

Research initiatives should evaluate their primary workload characteristics against architectural strengths. The "read" versus "write" distinction provides a foundational framework: tasks primarily involving information gathering, analysis, and comparison (read-intensive) naturally align with distributed architectures, while tasks centered on generating coherent outputs, synthesizing unified perspectives, or creating structured documents (write-intensive) benefit from centralized approaches [1].

Project complexity further refines this assessment. Straightforward extraction tasks with well-defined targets and consistent source materials may achieve optimal efficiency through centralized processing, while complex, multi-disciplinary research questions requiring diverse expertise and source integration typically benefit from distributed specialization [33]. Teams should also consider data dependency patterns - tightly coupled processes with significant state dependencies favor centralized control, while loosely coupled, modular operations can leverage distributed parallelism.

Organizational and Environmental Factors

Implementation context significantly influences architectural success. Organizational culture represents a particularly influential factor, with control-oriented environments often adapting more successfully to centralized models, while innovation-focused cultures may better leverage distributed approaches [34]. The BUILD framework (Be Open, Understand, Investigate, Leverage Opportunities, Drive Forward) provides a structured methodology for navigating these organizational dynamics when establishing decision-making structures [30].

Scalability requirements and resource constraints present additional considerations. Growing research operations with expanding data volumes and diversity typically benefit from distributed architectures' horizontal scaling capabilities [32]. Conversely, resource-constrained environments may prioritize the computational efficiency of centralized systems, particularly when handling sensitive data where consolidated governance simplifies compliance [32] [35]. Teams should honestly assess their technical infrastructure and expertise, as distributed systems demand robust coordination mechanisms and observability tooling to manage inherent complexity [1] [33].

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methodologies

Performance Benchmarking Framework

Rigorous architectural evaluation requires controlled measurement across defined experimental conditions. The following protocol establishes a standardized benchmarking approach:

Table 2: Experimental Reagents for Architecture Validation

| Research Component | Function in Experimental Protocol | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Task Repository | Provides standardized tasks for consistent performance measurement across architectures | Curated set of data extraction challenges from scientific literature with validated response benchmarks |

| Evaluation Metrics Suite | Quantifies performance across multiple dimensions for comparative analysis | Precision/recall for data extraction, latency measurements, token consumption tracking, consistency scoring |

| Observability Infrastructure | Captures system behaviors and internal states for debugging and analysis | LangSmith Studio for agent tracing, custom logging for inter-agent communication, context window monitoring |

| Coordination Mechanisms | Enables communication and task management in distributed architectures | Research pads for shared memory, hierarchical delegation protocols, swarm collaboration patterns |

Experimental implementation should commence with baseline establishment using controlled tasks representing common research operations: targeted data extraction from known sources, multi-document synthesis, and complex query resolution across disparate databases. Each architecture processes identical task sets under standardized resource constraints, with performance measured across the metrics outlined in Table 2 [1] [33].

For distributed systems, specific coordination patterns should be explicitly defined and maintained throughout testing - whether hierarchical (lead agent with specialized workers) or swarm (peer-to-peer collaboration). Centralized systems should implement optimized context management strategies to maximize their unified information advantage. Result validation must include both quantitative metric collection and qualitative assessment by domain experts to evaluate practical utility beyond numerical scores [33].

Hybrid Architecture Experimental Design

Many research environments benefit from hybrid approaches that combine architectural elements. Experimental protocols should specifically test integration patterns that leverage centralized consistency for critical functions while distributing parallelizable components. One validated methodology implements a distributed research team (multiple specialized agents) with a centralized synthesis agent that consolidates findings into coherent outputs [33].

Another hybrid model maintains centralized governance and quality control while distributing execution across specialized components. This approach particularly suits regulated research environments where audit trails and protocol adherence remain mandatory. Experiments should measure hybrid performance against pure architectures using the same benchmarking framework, with particular attention to integration overhead and overall system coherence [32] [35].

Implementation Pathways and Operationalization

Technical Implementation Considerations

Successful operationalization requires matching architectural choices to technical capabilities. Centralized implementations benefit from frameworks that support extensive tool integration and state management within a unified context, such as LangGraph for complex workflows [33]. The critical technical consideration involves context window management and optimization strategies to maximize the single-agent's effectiveness without exceeding processing limits [1].

Distributed implementations demand robust inter-agent communication frameworks and specialized tooling for durable execution, observability, and coordination management [1]. Architectures must explicitly address context sharing mechanisms, whether through research pads, shared memory spaces, or structured message passing [33]. Production deployments require sophisticated monitoring to track inter-agent dependencies and identify emergent bottlenecks or conflicting behaviors.

Organizational Implementation Strategy

Architectural transitions should follow incremental pathways, beginning with pilot projects that match each approach's strengths to specific research initiatives. The BUILD framework provides a structured methodology for organizational alignment: cultivating openness to different architectural paradigms, developing deep understanding of each approach's motivations, investigating context-specific solutions, leveraging hybrid opportunities, and driving implementation through concrete action plans [30].

Successful implementation further requires establishing appropriate success metrics aligned with architectural goals - centralized systems measured by consistency and efficiency, distributed systems by scalability and comprehensive coverage [36]. Organizations should anticipate evolving needs by designing flexible infrastructures that can incorporate additional specialized agents or transition certain functions to centralized control as processes mature and standardize.

The centralized versus distributed decision-making dichotomy presents research organizations with fundamentally different approaches to AI-driven data extraction, each with demonstrated strengths across specific task profiles and operational environments. Centralized architectures deliver reliability, consistency, and efficiency for state-dependent "write" tasks, while distributed systems provide scalability, specialization, and parallel processing capabilities for exploratory "read" tasks.

Informed architectural selection requires honest assessment of research priorities, technical capabilities, and organizational context rather than ideological preference. The most sophisticated implementations increasingly adopt hybrid models that strategically combine centralized coordination with distributed execution, applying each paradigm to its most suitable functions. As AI capabilities advance, the fundamental trade-offs documented here will continue to inform strategic infrastructure decisions for research organizations pursuing automated data extraction and scientific discovery.

Implementing AI Agents for Data Extraction: Methodologies and Biomedical Use Cases

In data extraction research, the transition from single-agent to multi-agent systems represents a fundamental architectural shift to overcome inherent limitations in handling complex, multi-faceted tasks. Single-agent systems often struggle with cognitive load, error propagation, and scalability constraints when faced with sophisticated data extraction pipelines that require multiple specialized capabilities [14]. Multi-agent systems address these challenges by decomposing complex problems into specialized, manageable components, allowing researchers to create more robust, efficient, and accurate data extraction workflows [37] [14].

This comparison guide objectively evaluates three core orchestration patterns—prompt chaining, routing, and parallelization—within the context of scientific data extraction, providing experimental data and methodological protocols to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals selecting architectural approaches for their research pipelines.

Core Orchestration Patterns: Comparative Analysis

Pattern Definitions and Characteristics

The following table summarizes the three core orchestration patterns, including their primary functions, complexity levels, and ideal use cases.

| Pattern | Core Function | Complexity Level | Best For Data Extraction Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prompt Chaining [38] [39] [14] | Decomposes tasks into sequential steps; each LLM call processes the previous output. | Low | Sequential research tasks: Literature review → Data synthesis → Report generation [14]. |

| Routing [39] [14] [40] | Classifies an input and directs it to a specialized follow-up agent or workflow. | Low to Medium | Directing different data query types to specialized extraction agents (e.g., clinical data → NLP agent, genomic data → bioinformatics agent) [14]. |

| Parallelization [39] [14] [40] | Executes multiple subtasks simultaneously (sectioning) or runs the same task multiple times (voting). | Medium | Extracting and validating information from multiple scientific databases or repositories concurrently [14] [40]. |

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Experimental simulations measuring processing efficiency and accuracy in a data extraction context reveal significant performance differences between single and multi-agent approaches.

| Performance Metric | Single-Agent System | Multi-Agent: Prompt Chaining | Multi-Agent: Routing | Multi-Agent: Parallelization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Task Completion Time (seconds) | 180 | 210 | 165 | 95 [40] |

| Data Extraction Accuracy (%) | 72 | 89 | 92 | 94 |

| Error Rate (%) | 18 | 8 | 6 | 5 |

| Scalability (Concurrent Tasks) | Low | Medium | Medium-High | High |

| Resource Utilization | Low | Medium | Medium | High |

Table 2: Experimental performance data for a complex data extraction task involving query interpretation, multi-source data retrieval, and synthesis. Source: Adapted from enterprise AI implementation studies [14] [40].

Experimental Protocols for Multi-Agent Data Extraction

Protocol 1: Evaluating Prompt Chaining for Literature Review

Objective: To assess the efficacy of a sequential multi-agent chain in extracting and synthesizing chemical compound data from scientific literature compared to a single-agent approach.

Methodology:

- Agent 1 (Identification): An LLM scans PubMed abstracts to identify manuscripts mentioning target chemical compounds.

- Gate Check: A programmatic check verifies that relevant papers were found before proceeding.

- Agent 2 (Extraction): A second LLM extracts specific properties (e.g., molecular weight, solubility, biological activity) from the identified papers.

- Agent 3 (Structuring): A final LLM formats the extracted data into a structured JSON schema for database entry.

Control: A single agent is tasked with performing all identification, extraction, and structuring steps within a single, complex prompt.

Metrics: Accuracy of extracted data (vs. human-curated gold standard), time to completion, and schema compliance.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Routing for Specialized Data Queries

Objective: To measure the accuracy improvement of using a routing pattern to direct queries to domain-specific extraction agents.

Methodology:

- Router Agent: A classifier LLM or algorithm categorizes incoming research queries into types: "genomic variant data," "clinical trial outcomes," or "pharmacokinetic parameters."

- Specialist Agents:

- Genomic Agent: Optimized to query and extract data from sources like dbSNP or ClinVar.

- Clinical Agent: Specialized in extracting endpoint data from ClinicalTrials.gov or published trial results.

- PK/PD Agent: Designed to pull parameters from drug databases like DrugBank.

- The router directs each query to the corresponding specialist agent for execution.

Control: A single, general-purpose agent handles all query types.

Metrics: Query response accuracy, reduction in "hallucinated" or incorrect data, and user satisfaction scores.

Protocol 3: Evaluating Parallelization for Multi-Source Data Validation

Objective: To quantify the speed and comprehensiveness gain from parallel data extraction versus serial processing.

Methodology:

- Orchestrator Agent: Receives a query for all known functions of a specific protein.

- Sectioning: The orchestrator simultaneously dispatches the same query to multiple, independent worker agents, each connected to a different database:

- Worker 1: Queries the UniProt knowledgebase.

- Worker 2: Searches the Gene Ontology (GO) database.

- Worker 3: Extracts data from relevant PubMed Central full-text articles.

- Synthesis: The orchestrator agent collates the results from all workers into a unified report.

Control: A single agent performs the three database queries sequentially.

Metrics: Total time to complete the full data extraction, number of unique data points retrieved, and data validity score.

Visualizing Orchestration Patterns for Research Workflows

Prompt Chaining Sequence

Diagram 1: Sequential prompt chaining for data extraction.

Routing and Specialization Network

Diagram 2: Routing pattern for specialized data queries.

Parallel Data Extraction Workflow

Diagram 3: Parallelization for multi-source data extraction.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

For researchers implementing multi-agent workflows for data extraction, the following "research reagents"—core components and tools—are essential for building effective experimental systems.

| Tool/Category | Example Solutions | Function in Multi-Agent Research |

|---|---|---|

| Orchestration Frameworks | LangGraph, Amazon Bedrock's AI Agent framework, Semantic Kernel [39] | Provides the underlying infrastructure to coordinate agents, assign tasks, and monitor progress [37] [39]. |

| Agent-to-Agent Protocols | A2A (Agent2Agent), MCP (Model Context Protocol) [41] | Enables secure, governed discovery and collaboration between agents and gives them consistent access to data sources and tools [41]. |

| Compute & Deployment | Azure Container Apps, AWS Lambda, Kubernetes [42] [41] | Offers a serverless or containerized platform for running and scaling agent-based microservices [42]. |

| Specialized Data Tools | Vector Databases, RAG Systems, API Connectors [39] [41] | Acts as the knowledge base and toolset for agents, providing access to structured and unstructured data sources [37]. |

| Monitoring & Guardrails | Custom Evaluators, HITL (Human-in-the-Loop) Systems [14] [41] | Ensures compliance, data security, and output quality through oversight, feedback loops, and toxicity filtering [37]. |

| Fluo-4FF AM | Fluo-4FF AM, MF:C50H46F4N2O23, MW:1118.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Polycarpine (hydrochloride) | Polycarpine (hydrochloride), MF:C22H26Cl2N6O2S2, MW:541.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The experimental data and protocols presented demonstrate that multi-agent orchestration patterns—prompt chaining, routing, and parallelization—offer quantifiable advantages over single-agent systems for complex data extraction tasks in research environments. The choice of pattern depends on the specific research requirement: prompt chaining for sequential, dependent subtasks; routing for leveraging specialized domain expertise; and parallelization for maximizing speed and comprehensiveness in multi-source data validation.

For scientific and drug development professionals, adopting these patterns can lead to more reliable, efficient, and scalable data extraction pipelines, ultimately accelerating the pace of research and discovery. Future work should focus on integrating these patterns with emerging standards like A2A and MCP to create even more interoperable and robust research agent systems.

The automation of data extraction from clinical trial reports represents a critical frontier in accelerating evidence synthesis for biomedical research. Within this domain, a fundamental architectural question has emerged: should this complex task be handled by a single-agent system, a monolithic AI designed to perform all steps, or a multi-agent system, where multiple specialized AI models collaborate? Single-agent systems employ one intelligent entity to manage the entire workflow from input to output, offering simplicity and rapid deployment for well-defined, linear tasks [11]. In contrast, multi-agent systems decompose the complex problem of data extraction into subtasks, distributing the workload among specialized agents working under a coordinating orchestrator [14]. This comparative guide objectively analyzes the performance of these two paradigms, drawing on recent experimental benchmarks to inform researchers and drug development professionals. The synthesis of evidence indicates that while single-agent systems suffice for narrow tasks, multi-agent ensembles demonstrate superior accuracy, reliability, and coverage for the intricate and heterogeneous data found in real-world clinical trial reports [43] [44].

Performance Comparison: Experimental Data and Benchmarks

Direct, head-to-head comparisons and related studies provide quantitative evidence for evaluating these two approaches. The key performance metrics from recent experiments are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Performance Benchmarks of Single-Agent vs. Multi-Agent Systems

| Study Focus & System Type | Models or Agents Involved | Key Performance Metrics | Reported Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Trial Data Extraction [43] | Multi-Agent Ensemble: OpenAI o1-mini, x-ai/grok-2-1212, Meta Llama-3.3-70B, Google Gemini-Flash-1.5, DeepSeek-R1-70B | Inter-model agreement (Fleiss κ), Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) | Multi-LLM ensemble achieved near-perfect agreement on core parameters (κ=0.94) and excellent numeric consistency (ICC 0.95-0.96). |

| Rare Disease Diagnosis [44] | Single-Agent: GPT-4Multi-Agent: GPT-4 based MAC (4 doctor agents + supervisor) | Diagnostic Accuracy (%) | Multi-Agent system significantly outperformed single-agent GPT-4 in primary consultation accuracy (34.11% vs single-agent performance). |

| AI System Capabilities (General) [11] | Single-Agent vs. Multi-Agent | Capability for Complex Tasks, Fault Tolerance, Development Complexity | Multi-agent systems showed 90.2% better performance on complex internal evaluations and higher resilience against single points of failure. |

A 2025 benchmark study specifically targeting the extraction of protocol details from transcranial direct-current stimulation (tDCS) trials provides compelling evidence for the multi-agent approach. The ensemble of five LLMs not only doubled the yield of eligible trials compared to conventional keyword search but also achieved almost perfect agreement on well-defined fields [43]. For instance, the binary field "brain stimulation used" showed near-perfect agreement (Fleiss κ ≈ 0.92), while numeric parameters like stimulation intensity showed excellent consistency (ICC 0.95–0.96) when explicitly reported [43]. This demonstrates the multi-agent system's ability to enhance both the breadth of data retrieval and the accuracy of its structuring.

Beyond data extraction, research in complex clinical reasoning reinforces this performance advantage. A 2025 study on diagnosing rare diseases found that a Multi-Agent Conversation (MAC) framework, which mimics clinical multi-disciplinary team discussions, significantly outperformed single-agent models (GPT-3.5 and GPT-4) in diagnostic accuracy and the helpfulness of recommended further tests [44]. The optimal configuration was achieved with four "doctor" agents and a supervisor agent using GPT-4 as the base model, underscoring the value of specialized role-playing and consensus-building [44].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Multi-LLM Ensemble Data Extraction

The benchmark for clinical trial data extraction employed a rigorous, standardized protocol to ensure a fair comparison among models and to validate the ensemble output [43].

- Data Retrieval and Ingestion: The pipeline began by ingesting trial records from ClinicalTrials.gov, specifically targeting aging-related tDCS trials.

- Structured Output Generation: Each of the five LLMs in the ensemble independently parsed the

BriefSummaryandDetailedDescriptionfields of the trial records. - Structured Output Generation: Using a predefined, structured JSON schema, each model generated a comparable output from the unstructured text, extracting specific fields such as stimulation intensity, session duration, and primary target.

- Independent Model Execution: Each of the five LLMs in the ensemble processed the trial data and generated extractions independently and in parallel.

- Consensus Mechanism (Ensemble): A consensus was formed from the individual model outputs. For categorical fields, a majority vote was used. For numeric parameters, mean or median averaging was applied. This step was crucial for resolving individual model disagreements and delivering a final, high-reliability output [43].

Protocol for Multi-Agent Diagnostic Evaluation

The study on rare disease diagnosis provides a clear methodology for constructing and testing a multi-agent system for a complex clinical task [44].

- Case Curation: The study used 302 curated clinical cases of rare diseases, simulating real-world primary and follow-up consultations.

- Agent Configuration: The Multi-Agent Conversation (MAC) framework was configured with multiple "doctor" agents (typically four) and one "supervisor" agent.

- Discussion and Consensus: Each doctor agent independently analyzed the patient case. Agents then engaged in a structured discussion to share perspectives and reasoning.

- Supervision and Output: The supervisor agent moderated the discussion and synthesized the consensus, which included the most likely diagnosis and recommended tests.

- Performance Benchmarking: The MAC framework's performance was evaluated against standalone single-agent models (GPT-3.5 and GPT-4) and other advanced prompting techniques like Chain of Thought (CoT) and Self-Consistency, using metrics of diagnostic accuracy and test helpfulness [44].

Workflow Architecture and System Diagrams

The fundamental difference between single and multi-agent systems is their workflow architecture, which directly impacts their performance on complex tasks. The following diagram illustrates the core multi-agent pattern used for data extraction.

Diagram 1: Multi-Agent Data Extraction Workflow

The performance advantages of multi-agent systems, as quantified in the benchmarks, can be visualized as a direct comparison across key operational dimensions.

Diagram 2: System Capability Comparison Profile

Implementing automated data extraction systems requires a combination of computational tools and methodological frameworks. The table below details key components referenced in the featured experiments.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Automated Data Extraction

| Tool or Component | Type | Primary Function in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Large Language Models (LLMs) [43] [44] | AI Model | Provide the core intelligence for understanding and processing natural language in clinical reports. Examples: GPT-4, Llama-3.3-70B. |

| Multi-Agent Orchestrator [14] [11] | Software Framework | Manages task delegation, data flow, and consensus among specialized agents (e.g., LangGraph, Azure Logic Apps). |

| Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) [45] | AI Technique | Enhances LLM accuracy by retrieving authoritative external evidence from databases or documents to ground the generation process. |

| Structured Output Schema (e.g., JSON) [43] | Data Protocol | Defines a standardized, machine-readable format for extracted data, ensuring consistency and interoperability. |

| Vector Database [45] | Data Storage | Enables efficient similarity search for RAG pipelines by storing data as numerical vectors (embeddings). |

| Clinical Data Repository (e.g., EHR, ClinicalTrials.gov) [43] [46] | Data Source | The source of unstructured or semi-structured clinical trial reports and patient data for the extraction pipeline. |

| Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (e.g., LoRA/QLoRA) [45] | AI Method | Adapts large foundation models to specialized domains (like oncology) using minimal computational resources. |

| Consensus Mechanism (Majority Vote/Averaging) [43] | Algorithm | Resolves disagreements between multiple agents or models to produce a single, more reliable output. |

The empirical evidence clearly demonstrates that multi-agent systems hold a significant performance advantage for the complex, high-stakes task of automated data extraction from clinical trial reports. The multi-LLM ensemble benchmark proved its ability to retrieve twice as many relevant trials as conventional methods while achieving expert-level accuracy on core protocol parameters (κ ≈ 0.94) [43]. This paradigm successfully addresses key limitations of single-agent architectures, such as cognitive overload and single points of failure, by distributing tasks among specialized agents [14] [11].

Future research will likely focus on optimizing multi-agent architectures further, exploring dynamic agent swarms [47], improving human-in-the-loop oversight [14], and integrating these systems more deeply with RAG and specialized fine-tuning [45]. For researchers and drug development professionals, the transition from single-agent to multi-agent systems represents a strategic evolution, enabling more comprehensive, accurate, and efficient synthesis of clinical evidence to accelerate the pace of medical discovery.

The accurate extraction of numerical data, such as event counts and group sizes, from clinical research documents represents a critical yet challenging task in evidence-based medicine and systematic review processes. Traditional methodologies, primarily human double extraction, while considered the gold standard, are notoriously time-consuming and labor-intensive, with documented error rates of 17% at the study level and 66.8% at the meta-analysis level [48]. This case study investigates the design and efficacy of an AI-human hybrid workflow for this specific data extraction task, positioning it within the broader architectural debate of single-agent versus multi-agent AI systems for research data extraction. The objective performance data presented herein provides a concrete framework for researchers, particularly in drug development and medical sciences, to make informed decisions when implementing AI-assisted data extraction protocols.

Experimental Design and Methodology

Core Experimental Protocol

The foundational methodology for this analysis is derived from a registered, randomized controlled trial (Identifier: ChiCTR2500100393) designed explicitly to compare AI-human hybrid data extraction against traditional human double extraction [48]. The study was structured as a randomized, controlled, parallel trial with the following key parameters:

- Participant Allocation: Participants were randomly assigned to either an AI group or a non-AI group at a 1:2 allocation ratio using computer-based simple randomization [48].

- AI Group Workflow (AI-Human Hybrid): Participants used a hybrid approach where Claude 3.5 (developed by Anthropic) performed the initial data extraction, after which the same participant verified and corrected the AI-generated results [48].