Revolutionizing Materials Science: Autonomous Robotics and AI in Solid-State Synthesis of Inorganic Powders

This article explores the transformative integration of robotics, artificial intelligence, and automated laboratories in the solid-state synthesis of inorganic powders.

Revolutionizing Materials Science: Autonomous Robotics and AI in Solid-State Synthesis of Inorganic Powders

Abstract

This article explores the transformative integration of robotics, artificial intelligence, and automated laboratories in the solid-state synthesis of inorganic powders. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it details how autonomous platforms like the A-Lab are accelerating materials discovery and optimization. The content covers foundational principles, core methodologies including AI-driven recipe generation and active learning, strategies for troubleshooting synthesis failures, and rigorous validation of these technologies against traditional methods. By synthesizing recent breakthroughs and real-world case studies, this review demonstrates how closed-loop, autonomous experimentation is bridging the gap between computational prediction and experimental realization, with profound implications for the development of advanced pharmaceuticals and functional materials.

The New Paradigm: Understanding Autonomous Solid-State Synthesis

The discovery and synthesis of novel functional materials are pivotal for addressing global challenges in clean energy, healthcare, and sustainable technologies. While computational methods have dramatically accelerated the prediction of promising materials, a significant gap persists between virtual screening and experimental realization. This disconnect is particularly pronounced in the solid-state synthesis of inorganic powders, where traditional trial-and-error approaches remain time-consuming and resource-intensive. The integration of robotics, artificial intelligence, and automated laboratories represents a paradigm shift in materials research, offering a pathway to bridge this computation-experiment divide. By creating closed-loop systems where computational predictions directly guide robotic experiments and experimental outcomes inform computational models, researchers can significantly accelerate the entire materials discovery pipeline from initial prediction to final synthesis.

Computational Foundations for Materials Discovery

Advanced computational methods form the critical first step in modern materials discovery workflows, enabling the identification of promising candidate materials before any experimental work begins.

Phase Stability and Reaction Energetics

The foundation of computational materials design rests on accurate prediction of phase stability. Large-scale ab initio calculations using density functional theory (DFT) provide essential data on formation energies and decomposition energies, allowing researchers to identify thermodynamically stable and metastable compounds [1]. The Materials Project and Google DeepMind have created extensive databases containing phase stability information for thousands of hypothetical and known materials, serving as invaluable resources for initial screening [1]. These databases enable researchers to construct convex hull diagrams that visually represent the thermodynamic stability of compounds relative to competing phases.

For electrocatalyst design focused on activating inert molecules like COâ‚‚, Nâ‚‚, and Oâ‚‚, computational approaches have evolved to incorporate complex interfacial phenomena under realistic operating conditions [2]. The computational hydrogen electrode model and constant electrode potential models allow for accurate predictions of reaction energetics at electrochemical interfaces, while ab initio thermodynamics extends these predictions to relevant temperature and pressure conditions [2].

Descriptor-Based Screening and Machine Learning

Descriptor-based screening methods underpinned by the Sabatier principle and volcano plot frameworks enable rapid identification of promising catalytic materials by correlating easily computable descriptors with catalytic activity [2]. These approaches allow researchers to screen thousands of candidate materials by computing simple metrics such as adsorption energies or electronic structure descriptors rather than calculating complete reaction pathways.

Machine learning techniques have further accelerated this screening process by creating surrogate models that predict materials properties orders of magnitude faster than traditional DFT calculations [3]. ML models trained on existing materials databases can identify complex patterns and relationships that are difficult to capture with conventional computational methods, enabling exploration of vast chemical spaces comprising millions of known and hypothetical materials [4].

Table 1: Computational Methods for Materials Discovery

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Key Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase Stability Analysis | Convex hull construction, Ab initio thermodynamics | Predicting synthesizable compounds, Identifying stable crystal structures | Limited to T=0K without extensions, Neglects kinetic barriers |

| Descriptor-Based Screening | Volcano plots, Scaling relations, Sabatier analysis | Electrocatalyst design, High-throughput materials screening | Requires known descriptor-property relationships, May miss unconventional materials |

| Machine Learning Approaches | Gradient boosting, Neural networks, Natural language processing | Property prediction, Synthesis condition optimization, Precursor selection | Requires large, high-quality datasets, Limited transferability across domains |

| Advanced Sampling | Ab initio molecular dynamics, Constant potential simulations | Electrochemical interfaces, Solvation effects, Finite-temperature behavior | Computationally expensive, Limited timescales |

Autonomous Laboratories: The A-Lab Case Study

The A-Lab represents a groundbreaking advancement in experimental materials science, demonstrating how integration of computation, robotics, and artificial intelligence can successfully bridge the computation-experiment gap for solid-state synthesis of inorganic powders.

System Architecture and Workflow

The A-Lab operates as an integrated system with three specialized stations for sample preparation, heating, and characterization, with robotic arms transferring samples and labware between them [1]. The preparation station dispenses and mixes precursor powders before transferring them into alumina crucibles. A robotic arm then loads these crucibles into one of four available box furnaces for heating. After synthesis and cooling, another robotic arm transfers samples to the characterization station, where they are ground into fine powder and measured by X-ray diffraction (XRD).

The operational workflow is controlled by decision-making agents that plan and interpret experiments. For each target compound, the system generates up to five initial synthesis recipes using machine learning models that assess target "similarity" through natural-language processing of a large database of syntheses extracted from the literature [1]. This approach mimics how human researchers base initial synthesis attempts on analogy to known related materials. Synthesis temperatures are proposed by a second ML model trained on heating data from the literature.

Performance and Outcomes

In a landmark demonstration, the A-Lab successfully synthesized 41 of 58 novel target compounds over 17 days of continuous operation, achieving a 71% success rate [1]. These materials spanned 33 elements and 41 structural prototypes, with 35 of the 41 successfully synthesized materials obtained using recipes proposed by ML models trained on literature data. The success rate could be improved to 74% with minor modifications to the decision-making algorithm and further to 78% with enhanced computational techniques [1].

Analysis revealed that literature-inspired recipes were more likely to succeed when reference materials were highly similar to the targets, confirming that target "similarity" provides a useful metric for selecting effective precursors [1]. However, precursor selection remains challenging even for thermodynamically stable materials, as only 37% of the 355 tested recipes produced their targets despite 71% of targets eventually being obtained.

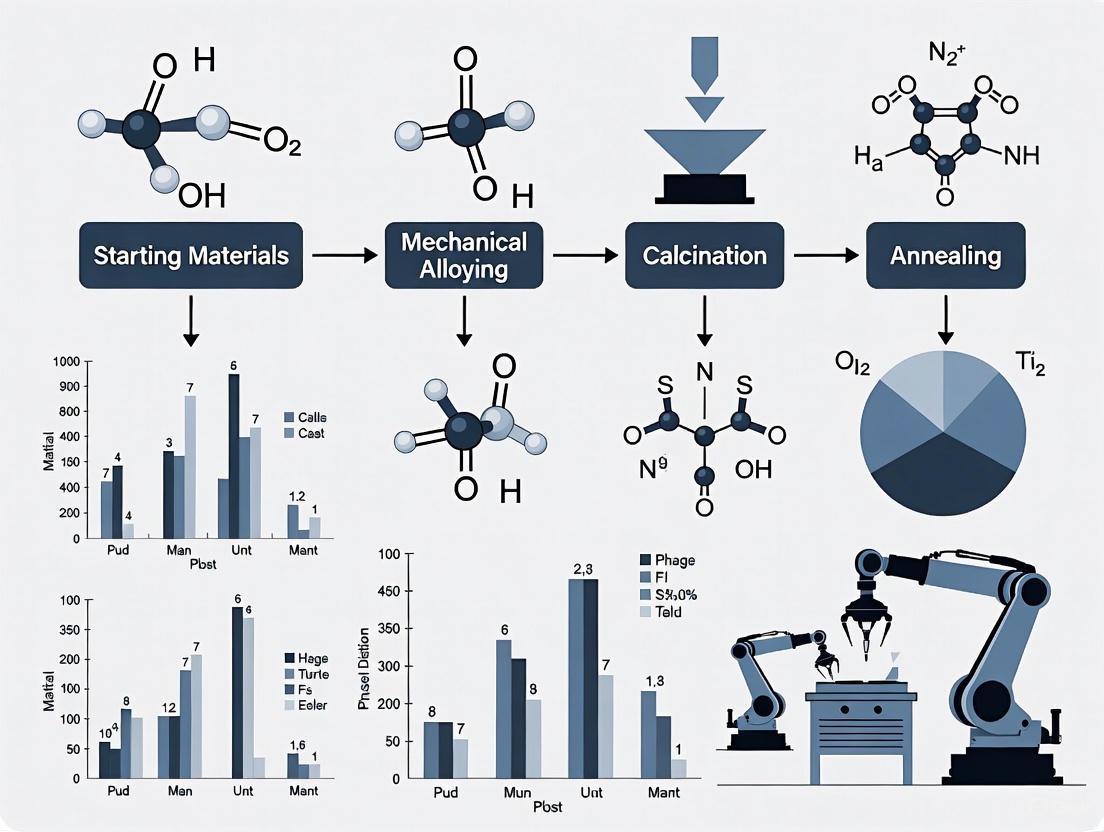

Diagram 1: A-Lab autonomous synthesis workflow. The system integrates computational screening, ML-based precursor selection, robotic synthesis, and active learning in a closed loop.

Active Learning and Optimization

When initial literature-inspired recipes failed to produce >50% target yield, the A-Lab employed an active learning cycle called Autonomous Reaction Route Optimization with Solid-State Synthesis (ARROWS3) [1]. This algorithm integrates ab initio computed reaction energies with observed synthesis outcomes to predict optimal solid-state reaction pathways.

The active learning approach identified improved synthesis routes for nine targets, six of which had zero yield from initial recipes [1]. The methodology is grounded in two key hypotheses: (1) solid-state reactions tend to occur between two phases at a time (pairwise reactions), and (2) intermediate phases that leave only a small driving force to form the target material should be avoided as they often require long reaction times and high temperatures [1].

The A-Lab continuously builds a database of pairwise reactions observed in experiments, which allows the products of some recipes to be inferred without testing. This knowledge of reaction pathways enables prioritization of intermediates with large driving forces to form the target, computed using formation energies from the Materials Project [1].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Solid-State Synthesis of Inorganic Powders

The solid-state synthesis of inorganic powders in automated systems like the A-Lab follows a standardized protocol with specific modifications for autonomous operation:

Precursor Preparation: Precursor powders are automatically dispensed using robotic powder handling systems. Precursors are selected based on ML recommendations from literature data or active learning algorithms, considering decomposition behavior and reactivity [1].

Mixing and Milling: Precursors are transferred to mixing containers and milled to ensure good reactivity between precursors. This step addresses challenges posed by different physical properties of precursor powders, including density, flow behavior, particle size, hardness, and compressibility [1].

Thermal Treatment: Mixed precursors are transferred to alumina crucibles and loaded into box furnaces using robotic arms. Heating profiles are applied based on ML recommendations from historical data, with temperatures typically ranging from 500°C to 1200°C depending on the material system [1].

Characterization and Analysis: Synthesized materials are ground into fine powders and characterized by X-ray diffraction. Phase and weight fractions of synthesis products are extracted from XRD patterns by probabilistic ML models trained on experimental structures from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database [1].

Machine Learning-Guided Synthesis Optimization

For multi-variable synthesis methods like chemical vapor deposition (CVD), machine learning models can quantitatively optimize synthesis parameters:

Data Collection: Synthesis data is collected from archived laboratory notebooks, typically containing hundreds of experimental data points with recorded parameters and outcomes [5]. For CVD-grown MoSâ‚‚, such datasets include parameters like gas flow rate, reaction temperature, reaction time, precursor distance, and boat configuration.

Feature Engineering: Initial feature sets are refined by eliminating fixed parameters and those with missing data. Pearson's correlation coefficients are calculated to quantify mutual information content between features, ensuring selected features have minimum redundancy [5].

Model Selection and Training: Multiple ML algorithms including XGBoost, support vector machines, Naïve Bayes, and multilayer perceptrons are evaluated using nested cross-validation to prevent overfitting [5]. The best-performing model is selected based on metrics like area under the receiver operating characteristic curve.

Interpretation and Optimization: SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis quantifies the importance of each synthesis parameter on experimental outcomes [5]. The trained model predicts success probabilities for unexplored parameter sets and recommends optimal conditions.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of automated synthesis platforms requires specific reagents, materials, and instrumentation tailored for robotic handling and high-throughput experimentation.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Automated Solid-State Synthesis

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Role | Considerations for Automation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precursor Materials | Metal oxides, Phosphates, Carbonate salts | Source of cation and anion components for target materials | Particle size distribution, Flow properties, Hygroscopicity |

| Reaction Vessels | Alumina crucibles, Quartz boats | Containment during thermal treatment | Robotic gripping compatibility, Thermal stability, Reusability |

| Characterization Consumables | XRD sample holders, Glass slides | Support for structural and morphological analysis | Compatibility with automated sample loading, Reusability |

| Robotic System Components | Solid dispensers, Liquid handlers, Robotic arms | Precise handling and transfer of materials | Precision, Payload capacity, Compatibility with labware |

| Analytical Instruments | X-ray diffractometers, Raman spectrometers | Structural characterization and phase identification | Automation compatibility, Data output standardization |

Analysis of Failure Modes and Synthesis Barriers

Despite advanced computational screening and robotic automation, significant barriers to successful synthesis remain. Analysis of the 17 unobtained targets in the A-Lab study revealed four primary categories of failure modes [1]:

Slow Reaction Kinetics: This affected 11 of the 17 failed targets, each containing reaction steps with low driving forces (<50 meV per atom) [1]. These kinetic limitations represent fundamental barriers that cannot be easily overcome by conventional optimization of synthesis parameters.

Precursor Volatility: Volatilization of precursor materials during thermal treatment prevented formation of desired phases in some targets, particularly those containing elements with high vapor pressures at synthesis temperatures [1].

Amorphization: Some synthesis reactions resulted in amorphous products rather than the desired crystalline phases, highlighting limitations in current computational methods for predicting glass-forming tendencies [1].

Computational Inaccuracy: In some cases, computational predictions of stability failed to align with experimental reality, emphasizing the need for improved accuracy in ab initio methods for certain material classes [1].

These failure modes provide direct and actionable suggestions for improving both computational screening techniques and experimental synthesis design. They highlight the importance of incorporating kinetic considerations alongside thermodynamic stability in computational predictions and the need for more sophisticated models that account for precursor chemistry and amorphous phase competition.

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

The integration of computation and experiment through robotic platforms represents a transformative approach to materials discovery, but several challenges and opportunities remain for further advancing the field.

Emerging Technologies and Methodologies

Future developments will likely focus on several key areas:

Improved Synthesisability Metrics: Moving beyond thermodynamic stability to develop more robust metrics that incorporate kinetic synthesizability, precursor compatibility, and reaction pathway analysis [4].

Enhanced Active Learning: Developing more sophisticated active learning algorithms that can navigate complex multi-objective optimization spaces encompassing yield, phase purity, and materials properties.

Multi-modal Characterization: Integrating complementary characterization techniques beyond XRD, such as electron microscopy and spectroscopic methods, to provide more comprehensive understanding of synthesis outcomes.

Closed-Loop Integration: Creating tighter feedback loops between computation and experiment, where not only synthesis outcomes but also functional properties are continuously fed back to improve computational models.

Concluding Remarks

The computation-experiment gap in materials discovery represents both a significant challenge and a tremendous opportunity. Autonomous laboratories like the A-Lab demonstrate that through thoughtful integration of computational screening, machine learning, robotics, and active learning, researchers can dramatically accelerate the discovery and synthesis of novel functional materials. As these technologies continue to mature and become more widely adopted, they promise to transform materials discovery from a slow, sequential process to a rapid, integrated one where computation and experiment work in concert to explore the vast landscape of possible materials. This acceleration is essential for addressing pressing global challenges in energy, sustainability, and healthcare that demand new materials with tailored properties and functions.

The Autonomous Laboratory (A-Lab) represents a transformative approach to materials research, specifically designed to close the significant gap between the computational prediction of novel materials and their experimental realization. Operating as a fully integrated, closed-loop system, the A-Lab leverages artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, and historical data to autonomously plan, execute, and interpret solid-state synthesis experiments for inorganic powders. This platform addresses a critical bottleneck in materials science; while high-throughput computations can identify thousands of promising candidates, traditional manual experimentation is too slow to validate them. The A-Lab operates on the principle of autonomy—the ability of an experimental agent to interpret data and make subsequent decisions based on that analysis with minimal human intervention. By integrating computations, machine learning, and automation into a continuous workflow, the A-Lab achieves a dramatic acceleration in the pace of materials discovery and development, operating 24/7 and processing 50 to 100 times more samples per day than a human researcher [1] [6]. Its design is particularly focused on solid-state synthesis, which, while more challenging to automate than liquid-handling systems, produces multigram quantities of powder samples that are directly suitable for manufacturing and device-level testing in technologies such as batteries, solar cells, and other clean energy applications [1] [6].

Technical Architecture and Workflow

The A-Lab's operational pipeline is a tightly integrated sequence of computational planning, robotic execution, and AI-driven analysis. The entire process is schematically represented in the workflow diagram below, which outlines the core closed-loop logic.

The process initiates with the selection of a target material. These targets are typically novel inorganic compounds identified through large-scale ab initio phase-stability calculations from databases like the Materials Project and Google DeepMind. To ensure compatibility with the A-Lab's open-air environment, targets are filtered to be air-stable, predicted not to react with Oâ‚‚, COâ‚‚, or Hâ‚‚O [1]. For each selected compound, the system generates initial synthesis recipes using machine learning models trained on vast historical data extracted from scientific literature. These models assess "target similarity" to known materials to propose effective precursor powders and synthesis temperatures, mimicking the analogy-based approach of a human chemist [1] [7].

The physical synthesis is carried out by a coordinated robotic system. This system consists of three main stations:

- A preparation station where robotic arms dispense and mix precursor powders from a library of nearly 200 starting materials into alumina crucibles [1] [6].

- A heating station where a robotic arm loads the crucibles into one of four (or up to eight) box furnaces for solid-state reaction [1] [6].

- A characterization station where another robotic arm transfers the cooled sample, which is ground into a fine powder and analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD) to determine its crystalline structure and phases [1].

The interpretation of the XRD data is performed by probabilistic machine learning models trained on experimental structures. For novel compounds with no known experimental pattern, the A-Lab uses simulated patterns derived from computed structures, which are corrected to minimize errors from density functional theory (DFT) calculations. The phases identified by ML are subsequently confirmed with automated Rietveld refinement to quantify the weight fractions of the reaction products [1]. This analytical result closes the loop. If the target material is synthesized with a yield greater than 50%, the experiment is deemed a success. If not, the system activates an active learning cycle to propose and test a refined synthesis recipe.

Active Learning and Optimization

The active learning module, specifically the ARROWS³ (Autonomous Reaction Route Optimization with Solid-State Synthesis) algorithm, is the core of the A-Lab's adaptive intelligence [1]. This component becomes active when initial, literature-inspired synthesis attempts fail to produce a high yield of the target material. ARROWS³ leverages two key hypotheses grounded in solid-state chemistry:

- Pairwise Reaction Tendency: Solid-state reactions often proceed through intermediate phases that form between two precursors at a time [1].

- Driving Force Principle: Intermediate phases that leave only a small thermodynamic driving force to form the final target should be avoided, as they often lead to kinetic traps and require prolonged reaction times or higher temperatures [1].

As the A-Lab conducts more experiments, it builds a growing database of observed pairwise reactions between solid precursors. This knowledge allows it to intelligently narrow the search space of possible synthesis routes. For instance, if a recipe is predicted to yield a set of intermediates already known to the database, the system can preclude testing that recipe at higher temperatures, as the remaining pathway is already understood. This can reduce the search space by up to 80% [1]. The algorithm then prioritizes alternative synthesis routes that feature intermediates with a larger computed driving force (derived from formation energies in the Materials Project) to form the desired target, thereby increasing the likelihood of a successful high-yield synthesis.

Key Experimental Protocols and Outcomes

Synthesis Campaign and Performance Data

In a landmark demonstration of its capabilities, the A-Lab was tasked with synthesizing 58 novel, computationally predicted inorganic compounds over a continuous 17-day period. The outcomes of this campaign are summarized in the table below, which provides quantitative data on its performance and the distribution of synthesis methods [1].

Table 1: A-Lab Experimental Outcomes from 17-Day Synthesis Campaign

| Metric | Value | Details/Context |

|---|---|---|

| Targets Attempted | 58 | Novel oxides and phosphates; 52 had no prior synthesis reports [1]. |

| Successfully Synthesized | 41 | Represents a 71% success rate for first-ever synthesis attempts [1]. |

| Obtained via Literature-Inspired Recipes | 35 of 41 | Initial recipes from ML models trained on historical data [1]. |

| Optimized via Active Learning (ARROWS³) | 6 of 41 | Targets where the active learning cycle identified a successful recipe after initial failure [1]. |

| Total Recipes Tested | 355 | Demonstrates that precursor selection is non-trivial, with only 37% of individual recipes producing the target [1]. |

| Potential Improved Success Rate | Up to 78% | Analysis suggests minor algorithmic and computational adjustments could increase success [1]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The operation of the A-Lab relies on a suite of specialized hardware, software, and materials. The following table details the key components that constitute the essential "toolkit" for this autonomous research platform.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for the A-Lab

| Category | Item / Component | Function / Description |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Materials | ~200 Inorganic Powders | A comprehensive library of solid-state precursor compounds used as starting ingredients for reactions [6]. |

| Laboratory Hardware | Alumina Crucibles | Reusable containers in which precursor powders are mixed and heated to high temperatures [1]. |

| Robotic & Automation Systems | 3 Robotic Arms | Perform sample and labware transfer between preparation, heating, and characterization stations [1] [6]. |

| 4-8 Box Furnaces | Heated environments for solid-state synthesis reactions; allow for parallel processing [1] [6]. | |

| Characterization Instrument | X-ray Diffractometer (XRD) | The primary analytical tool for identifying crystalline phases and quantifying yield in the synthesized powder [1]. |

| Computational Resources | Materials Project Database | Source of ab initio calculated formation energies and phase stability data for target selection and pathway analysis [1] [7]. |

| Natural Language Models | Train on historical literature data to propose initial synthesis recipes and precursors [1] [8]. | |

| Active Learning Algorithm (ARROWS³) | Uses thermodynamic data and observed reactions to optimize failed synthesis attempts [1]. | |

| Norfenefrine hydrochloride | Norfenefrine Hydrochloride | Norfenefrine hydrochloride is an α-adrenergic agonist for hypotension research. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

| 6'-O-beta-D-glucosylgentiopicroside | 6'-O-beta-D-glucosylgentiopicroside, CAS:115713-06-9, MF:C22H30O14, MW:518.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Analysis of Failure Modes and Future Directions

Despite its high success rate, the A-Lab did not obtain 17 of its 58 target materials. Analysis of these failures revealed four primary categories of obstacles, as detailed in the table below. Understanding these failure modes is crucial for guiding future improvements in both autonomous labs and computational screening methods [1].

Table 3: Analysis of Synthesis Failure Modes in the A-Lab

| Failure Mode | Prevalence | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Slow Reaction Kinetics | 11 of 17 failures | The most common issue, particularly affecting reactions with low driving forces (<50 meV per atom), where the reaction rate is too slow under tested conditions [1]. |

| Precursor Volatility | Not Specified | The loss of one or more precursor materials due to evaporation or decomposition before they can react to form the target phase [1]. |

| Amorphization | Not Specified | The formation of non-crystalline products, which cannot be detected or analyzed by standard X-ray diffraction techniques [1]. |

| Computational Inaccuracy | Not Specified | Instances where the predicted stability of the target material from DFT calculations does not align with experimental reality [1]. |

Future development of autonomous laboratories will focus on overcoming these constraints. Key directions include the integration of more advanced AI models, such as Large Language Models (LLMs) for planning and foundation models for cross-domain generalization [8]. To address data scarcity, the development of standardized data formats and the use of high-quality simulations will be essential. Furthermore, enhancing hardware modularity to accommodate a wider range of chemical tasks (e.g., integrating liquid handling for organic synthesis) and developing robust error-detection and fault-recovery protocols will be critical for expanding the scope and reliability of self-driving labs [8].

The solid-state synthesis of inorganic powders is a cornerstone in the discovery of novel materials for applications in energy storage, catalysis, and electronics. Traditional synthesis methods rely heavily on trial-and-error, a process that is time-consuming, labor-intensive, and often limits the exploration of complex chemical spaces. The integration of robotics, artificial intelligence (AI), and data integration is transforming this field, turning laboratories into automated factories for discovery. This whitepaper details the core technological components enabling the development of autonomous laboratories for the accelerated synthesis of novel inorganic materials, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a technical guide to this transformative paradigm.

Robotic Automation Systems

Robotic systems form the physical backbone of autonomous laboratories, executing synthetic procedures and handling materials with superhuman precision and endurance. In the context of solid-state synthesis, which involves handling and processing powders, this requires specialized automation solutions.

System Architectures and Workflows

Two predominant robotic architectures have emerged: integrated fixed systems and modular mobile systems.

- Integrated Fixed Systems: Platforms like the A-Lab employ a tightly integrated design where robotic arms transfer samples and labware between dedicated, co-located stations for powder preparation, heating, and characterization [1]. This configuration is optimized for high-throughput, continuous operation on a specific class of reactions—in this case, solid-state synthesis of inorganic powders.

- Modular Mobile Systems: An alternative approach uses free-roaming mobile robots to connect existing, standard laboratory instruments [9]. This paradigm offers greater flexibility, allowing robots to transport samples between a synthesizer (e.g., a Chemspeed ISynth), an X-ray diffractometer (XRD), and other characterization tools like nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrometers, without requiring extensive and permanent hardware integration [9]. This is particularly suited for exploratory chemistry where the required instrumentation may vary.

The workflow in a fixed system for solid-state synthesis, as demonstrated by the A-Lab, typically follows these steps [1]:

- Powder Dispensing and Mixing: A robotic station dispenses precise masses of precursor powders and mixes them to ensure homogeneity.

- Crucible Transfer: A robotic arm transfers the filled alumina crucibles to a box furnace.

- Heating: The sample is heated in the furnace according to a computationally derived temperature profile.

- Post-Reaction Characterization: After cooling, another robotic arm transfers the sample to a station where it is ground into a fine powder and its structure is analyzed by XRD.

Levels of Laboratory Automation

The progression of automation in a laboratory can be categorized into five levels, which help in assessing current capabilities and setting future goals [10]:

- A1: Assistive Automation: Individual tasks, such as liquid handling, are automated while humans handle the majority of the work.

- A2: Partial Automation: Robots perform multiple sequential steps, with humans responsible for setup and supervision.

- A3: Conditional Automation: Robots manage entire experimental processes, though human intervention is required when unexpected events arise.

- A4: High Automation: Robots execute experiments independently, setting up equipment and reacting to unusual conditions autonomously.

- A5: Full Automation: At this final stage, robots and AI systems operate with complete autonomy, including self-maintenance and safety management.

Most advanced autonomous laboratories, such as the A-Lab, currently operate at the A3 (Conditional Automation) level, with some aspects approaching A4 [1] [10].

Artificial Intelligence and Planning

Artificial intelligence serves as the cognitive center of the autonomous laboratory, making critical decisions about experimental design, execution, and analysis.

Target Selection and Initial Recipe Generation

The process begins with the selection of promising target materials, often identified from large-scale ab initio phase-stability databases like the Materials Project and Google DeepMind [1] [8]. These targets are typically stable or near-stable compounds predicted by density functional theory (DFT) calculations.

For a given target compound, the AI must then propose initial synthesis recipes. This is often achieved using machine learning models trained on vast historical datasets extracted from the scientific literature:

- Natural-Language Models: Models trained on text-mined synthesis data from numerous papers can assess target "similarity" to known compounds and propose effective precursors by analogy to literature procedures [1].

- Large Language Model (LLM) Agents: More recently, frameworks like LLM-RDF and Coscientist have used LLMs such as GPT-4 to power specialized agents [8] [11]. These agents can perform literature searches, extract detailed synthetic procedures, and design experiments based on natural language prompts from researchers.

Active Learning and Route Optimization

When initial synthesis recipes fail to produce a high target yield (>50%), active learning closes the loop by proposing improved follow-up recipes. The A-Lab's Autonomous Reaction Route Optimization with Solid-State Synthesis (ARROWS3) algorithm is a key example [1]. Its operation is based on two core hypotheses:

- Solid-state reactions tend to occur between two phases at a time (pairwise reactions).

- Intermediate phases that leave only a small driving force to form the target material should be avoided, as they often require long reaction times and high temperatures [1].

The system continuously builds a database of observed pairwise reactions, which allows it to infer the products of some recipes without testing them, thereby reducing the experimental search space by up to 80% [1]. It then prioritizes reaction pathways with a large thermodynamic driving force, computed using formation energies from the Materials Project, to overcome kinetic barriers.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of the A-Lab in Solid-State Synthesis [1]

| Metric | Value | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Operation Duration | 17 days | Continuous operation |

| Novel Targets Attempted | 58 | Oxides and phosphates |

| Successfully Synthesized | 41 compounds | 71% success rate |

| Synthesized via Literature Recipes | 35 compounds | ML-based precursor selection |

| Optimized via Active Learning | 9 targets | 6 had zero initial yield |

| Potential Improved Success Rate | 78% | With improved computational techniques |

The following diagram illustrates the closed-loop, autonomous workflow that integrates robotics, AI, and data analysis.

Data Integration and Analysis

The final core component is the seamless integration and interpretation of data, which enables the autonomous loop to function.

Automated Characterization and Analysis

A critical step is the rapid and accurate analysis of characterization data to determine the outcome of an experiment. For solid-state synthesis, powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) is the primary technique.

- Machine Learning-Powered Phase Analysis: In the A-Lab, XRD patterns are analyzed by probabilistic ML models trained on experimental structures from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [1]. For novel compounds with no experimental reports, diffraction patterns are simulated from computed structures and corrected for DFT errors.

- Automated Rietveld Refinement: The phases identified by ML are subsequently confirmed with automated Rietveld refinement to determine weight fractions with high reliability [1].

- Multi-Modal Data Integration: In modular platforms, orthogonal techniques like mass spectrometry (MS) and NMR spectroscopy are combined. A heuristic decision-maker can then assign a pass/fail grade to each reaction based on all available data streams, mimicking a human expert's decision-making process [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details essential materials and reagents used in automated solid-state synthesis and characterization experiments.

Table 2: Essential Materials for Robotic Solid-State Synthesis [1] [12] [13]

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Precursor Powders | High-purity inorganic powders (e.g., metal oxides, carbonates, phosphates) that serve as starting materials for solid-state reactions. Their physical properties (density, flow) are critical for automated handling [1]. |

| Alumina Crucibles | Chemically inert containers that hold powder samples during high-temperature reactions in box furnaces [1]. |

| Nano-Silica Glidants | Additives like Aerosil R972P or A200 used in "dry coating" to modify powder flowability by reducing interparticle cohesion, ensuring consistent dispensing in automated systems [13]. |

| Standard Reference Materials | Crystalline standards (e.g., NIST Si) used for instrument calibration and validation of automated XRD analysis protocols [1]. |

| Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) | Common pharmaceutical excipient used in powder flowability studies; serves as a model system for understanding and optimizing powder handling in automated platforms [12] [13]. |

| 4'-O-trans-p-Coumaroylmussaenoside | 4'-O-trans-p-Coumaroylmussaenoside, MF:C26H32O12, MW:536.5 g/mol |

| 22-Dehydroclerosterol glucoside | 22-Dehydroclerosterol glucoside, MF:C35H56O6, MW:572.8 g/mol |

Experimental Protocol: Active Learning Cycle for Synthesis Optimization

This protocol details the methodology for an autonomous cycle to optimize the synthesis of a novel inorganic material, based on the operation of the A-Lab [1].

- Objective: To synthesize a target inorganic compound as the majority phase (>50% yield) from precursor powders, using an AI-driven active learning loop.

- Materials: Precursor powders (e.g., carbonates, oxides), alumina crucibles, box furnaces, robotic powder handling system, X-ray diffractometer.

Procedure:

- Initial Recipe Proposal: For a novel target (e.g., CaFe2P2O9), generate up to five initial synthesis recipes using a natural-language model trained on historical literature. The model selects precursors based on chemical similarity to known compounds. A separate ML model proposes a synthesis temperature [1].

- Robotic Synthesis Execution: a. The robotic system dispenses and mixes the precursor powders by mass. b. A robotic arm transfers the mixed powder in an alumina crucible to a box furnace. c. The furnace heats the sample according to the proposed temperature profile [1].

- Automated Product Characterization: a. After cooling, the robot transfers the sample to a preparation station for grinding. b. The ground powder is characterized by XRD [1].

- AI-Powered Data Analysis: a. The XRD pattern is analyzed by a convolutional neural network to identify crystalline phases and estimate their weight fractions. The analysis is confirmed with automated Rietveld refinement [1]. b. The resulting phase composition and target yield are reported to the lab's management server.

- Decision and Iteration: a. IF the target yield is >50%, the experiment is concluded successfully. b. IF the target yield is <50%, the active learning algorithm (ARROWS3) is activated. The algorithm consults its database of observed pairwise reactions and uses thermodynamic data from the Materials Project to predict a new, improved synthesis route that avoids low-driving-force intermediates [1].

- Loop Closure: The new recipe is sent to the robotic synthesis system (return to Step 2), and the cycle repeats until the target is obtained or all recipe options are exhausted.

The integration of robotics, AI, and data integration is not merely an incremental improvement but a paradigm shift in the solid-state synthesis of inorganic materials. The core components detailed in this whitepaper—encompassing flexible robotic systems, intelligent AI planners for design and optimization, and robust data integration pipelines—enable the operation of autonomous laboratories that can execute the "design-make-test-analyze" cycle with unprecedented speed and scale. As these technologies mature and reach higher levels of automation, they hold the promise of dramatically accelerating the discovery of next-generation materials for pharmaceuticals, energy, and beyond.

The discovery and synthesis of novel inorganic materials are pivotal for advancing technologies in energy storage, computing, and sustainability. Traditional experimental methods are often slow, resource-intensive, and rely on serendipity. The integration of ab initio computational databases and robotic laboratories has revolutionized this process, enabling a data-driven, accelerated approach to materials discovery. Ab initio, or first-principles calculations, primarily using Density Functional Theory (DFT), allow researchers to predict the stability and properties of materials before any physical synthesis is attempted [14]. Two resources central to this modern paradigm are the Materials Project and Google DeepMind's GNoME database.

The Materials Project, established at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, is an open-access database that computes the properties of both known and predicted materials. It uses DFT calculations, as implemented in the Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package (VASP), to evaluate total energies and properties of compounds at 0 K and 0 atm, providing a foundational dataset for materials screening [15] [14]. In a significant expansion, Google DeepMind's GNoME (Graph Networks for Materials Exploration) tool has used deep learning to predict 2.2 million new crystal structures, of which 380,000 are classified as stable and have been added to the Materials Project [16] [17]. This collaboration provides an unprecedented resource for identifying promising synthesis targets, particularly for functional applications such as better batteries, superconductors, and carbon capture materials [17].

When framed within the context of robotic solid-state synthesis of inorganic powders, as exemplified by the A-Lab at Berkeley Lab, these databases shift the research paradigm. They provide the essential computational foundation for selecting targets and planning their synthesis with minimal human intervention, effectively bridging the gap between computational prediction and experimental realization [1] [6].

Core Database Fundamentals and Properties

Key Properties for Target Selection

Selecting a viable material for synthesis requires evaluating key computed properties that indicate thermodynamic stability and synthesizability. The following properties are fundamental to this process.

Table 1: Key Ab Initio Properties for Synthesis Target Selection

| Property | Description | Role in Target Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Formation Energy | The energy released when a compound is formed from its constituent elements in their standard states. | A negative value indicates that the compound is thermodynamically stable relative to its elements. It is a primary filter for stability [1]. |

| Decomposition Energy (Energy Above Hull) | The energy required for a material to decompose into the most stable set of other compounds on the phase diagram (the "convex hull") [1]. | The primary metric for thermodynamic stability. A value of 0 meV/atom means the material is on the convex hull and is stable. Values below 50 meV/atom are often considered potentially synthesizable (metastable) [1] [16]. |

| Distance to Known Materials | A measure of a material's similarity to previously synthesized compounds, often based on composition or crystal structure. | Helps assess synthetic feasibility. Targets with high similarity to known materials are more likely to have successful, literature-inspired synthesis recipes [1]. |

Database Characteristics and Scale

The scale and data composition of these databases directly influence the breadth of available targets.

Table 2: Scale and Characteristics of Major Ab Initio Databases

| Database | Primary Function | Key Outputs | Scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Materials Project | Provides computed properties of known and predicted inorganic materials using DFT [14]. | Crystal structures, formation and decomposition energies, band gaps, elastic properties, and more. | Contains hundreds of thousands of structures; integrated GNoME's 380,000 new stable materials [17]. |

| GNoME (Google DeepMind) | A deep learning tool that predicts the stability of novel crystal structures [16]. | Crystal structures and formation energy. | Discovered 2.2 million new crystals, identifying 380,000 as stable [16] [17]. |

| A-Lab Experimental Database | An autonomous lab that tests synthesis recipes and logs outcomes, building a database of successful and failed reactions [1]. | Experimentally verified synthesis recipes, observed reaction pathways (intermediates), and product yield data. | Identified 88 unique pairwise reactions during its initial campaign; successfully synthesized 41 novel compounds [1]. |

The Target Selection Workflow

The process of selecting targets for robotic synthesis is a multi-stage workflow that moves from computational screening to experimental planning. The following diagram illustrates this integrated pipeline.

Diagram 1: The integrated computational-experimental workflow for target selection and synthesis, as implemented in the A-Lab [1].

Stage 1: Computational Screening for Stability and Properties

The first stage involves using ab initio databases to filter for the most promising candidate materials.

- Identify Thermodynamically Stable Targets: The primary filter is the decomposition energy (energy above hull). The A-Lab, for instance, selected targets predicted to be on or very near (<10 meV/atom) the convex hull of stable phases from the Materials Project and a cross-referenced DeepMind database [1]. The GNoME project further refined this by defining the most promising 380,000 materials as those lying on the "final" convex hull, representing the new standard for stability [16].

- Assess Environmental Stability: For practical synthesis and handling, targets must be air-stable. The A-Lab screened out materials predicted to react with Oâ‚‚, COâ‚‚, or Hâ‚‚O [1].

- Screen for Functional Properties: Once stable candidates are identified, they are screened for specific application-driven properties. For example, GNoME has identified 52,000 new layered compounds similar to graphene for electronics and 528 potential lithium-ion conductors for improved batteries [16].

Stage 2: From Digital Target to Physical Synthesis

Once a target is selected digitally, the process shifts to planning its physical synthesis.

- AI-Generated Recipe Proposal: Initial synthesis recipes are generated using machine learning models trained on historical data from scientific literature. These models assess target similarity to known materials to propose effective precursor powders and a synthesis temperature [1].

- Active Learning for Recipe Optimization: If the initial recipes fail to produce a high yield (>50%), an active learning loop is initiated. The A-Lab uses the ARROWS³ algorithm, which integrates ab initio computed reaction energies with observed synthesis outcomes. It leverages two key hypotheses:

- Pairwise Reaction Preference: Solid-state reactions tend to occur between two phases at a time [1].

- Driving Force Maximization: Intermediate phases that leave only a small driving force (<50 meV/atom) to form the target should be avoided, as they often lead to kinetic bottlenecks [1]. The lab builds a database of observed pairwise reactions, which allows it to avoid redundant testing and prioritize reaction pathways with larger driving forces [1].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Autonomous Synthesis and Characterization in the A-Lab

The following methodology details the experimental protocol used by the A-Lab to synthesize and characterize a target material [1].

- Precursor Dispensing and Mixing: Robotic arms dispense and mix precursor powders from a library of approximately 200 starting ingredients based on the AI-proposed recipe. The mixed powders are transferred into alumina crucibles.

- Robotic Heating: A robotic arm loads the crucibles into one of four available box furnaces for heating. The heating profile (temperature and duration) is set by the AI model.

- Cooling and Sample Transfer: After the reaction is complete and the sample has cooled, a robotic arm transfers the crucible to the next station.

- Post-Synthesis Processing: The synthesized solid is ground into a fine powder by a robotic shaker to prepare it for analysis.

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD) Characterization: The powdered sample is measured by XRD.

- Machine Learning Analysis: The XRD pattern is analyzed by probabilistic ML models to identify phases and their weight fractions. The results are confirmed with automated Rietveld refinement.

- Data Feedback and Decision Making: The resulting phase composition and yield are reported to the lab's management server. If the target yield is insufficient, the active learning cycle proposes a modified recipe, and the process repeats.

Protocol: Validating Diffusivity in Amorphous Materials

For materials where ionic conductivity is a key property, such as solid electrolytes, Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics (AIMD) can be used to validate diffusivity before synthesis. The following protocol is derived from the creation of an amorphous materials database [18].

- Generate Amorphous Structure: Using a starting crystal structure, perform a molecular dynamics simulation at high temperature (e.g., 5000 K) to melt the material and destroy long-range order.

- Computational Quenching: Rapidly quench the molten structure to lower temperatures (e.g., 1000K, 1500K, 2000K) to "freeze" in a representative amorphous structure. This requires larger unit cells than typical DFT calculations to capture sufficient local environments.

- Calculate Ionic Diffusivity: Using AIMD trajectories at different temperatures, calculate the mean squared displacement (MSD) of the mobile ions (e.g., Liâº).

- Extract Diffusion Coefficient: The diffusion coefficient (D) is derived from the slope of the MSD versus time. The activation energy (Eâ‚) for diffusion can then be determined from an Arrhenius plot of D versus 1/T.

- Machine Learning Correlation: The resulting database of structures and diffusivities can be used to train machine learning models to rapidly predict Li-ion diffusivity based on composition and structural features, offering a cost-effective alternative to full AIMD calculations [18].

This section details the key hardware, software, and data resources that constitute the modern materials scientist's toolkit for autonomous discovery.

Table 3: Essential Resources for AI-Driven Materials Synthesis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function |

|---|---|---|

| A-Lab (Berkeley Lab) | Robotic Laboratory | A fully automated, closed-loop facility that uses robotics and AI to synthesize inorganic powders from precursor compounds, operating 24/7 [1] [6]. |

| Materials Project Database | Ab Initio Database | The core open-access database providing computed properties for hundreds of thousands of materials, essential for initial stability and property screening [17] [14]. |

| GNoME Database | Deep Learning Database | A massive expansion of stable crystal structures, significantly enlarging the pool of viable synthesis targets for clean energy and other technologies [16] [17]. |

| VASP (Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package) | Simulation Software | The primary software used for performing DFT calculations to evaluate total energies and properties of materials in the Materials Project [15]. |

| ARROWS³ Algorithm | Active Learning Software | An algorithm that uses computed reaction energies and experimental data to optimize solid-state synthesis routes by avoiding low-driving-force intermediates [1]. |

| Inorganic Powder Precursors | Research Reagent | The ~200 different solid-state powder starting materials used by the A-Lab for solid-state synthesis reactions [6]. |

The integration of ab initio databases from the Materials Project and Google DeepMind with robotic synthesis platforms like the A-Lab represents a transformative advancement in materials science. This synergy creates a closed-loop, data-driven pipeline that dramatically accelerates the discovery of novel inorganic materials. The workflow—from computational screening for stable targets based on decomposition energy, through AI-powered synthesis planning, to autonomous experimental execution and active learning—has proven highly effective, successfully synthesizing dozens of new compounds. This paradigm not only increases the rate of discovery but also systematically builds a knowledge base of synthesis pathways, continuously refining the process. As these databases grow and AI models become more sophisticated, this approach is poised to become the standard for developing the next generation of functional materials for energy, electronics, and beyond.

Inside the A-Lab: AI-Driven Workflows and Robotic Execution

The experimental realization of computationally predicted inorganic materials has long been hindered by slow, manual synthesis processes, creating a critical bottleneck in materials discovery. To close this gap, autonomous laboratories represent a paradigm shift, integrating robotics, artificial intelligence (AI), and historical data to accelerate research. A cornerstone of this approach is the use of natural language processing (NLP) and large language models (LLMs) to generate viable synthesis recipes by learning from the vast body of scientific literature [1] [8] [19]. This technical guide details the methodologies and protocols for employing these technologies within the context of the solid-state synthesis of inorganic powders using robotics, providing researchers with a framework for implementing autonomous discovery pipelines.

Core Concepts and Definitions

- Natural Language Processing (NLP): A field of AI that enables computers to understand, interpret, and generate human language. In materials science, it is used for automatic data extraction from scientific literature [19].

- Large Language Models (LLMs): Advanced NLP models, such as GPT and BERT, pre-trained on massive text corpora. They can be fine-tuned for specialized tasks like synthesizing information from materials science publications [19].

- Word Embeddings: Dense, low-dimensional vector representations of words that capture semantic and syntactic similarities. Models like Word2Vec and GloVe create these embeddings, allowing algorithms to assess material "similarity" for precursor selection [19].

- Autonomous Laboratory (Self-Driving Lab): A platform that integrates AI, robotic experimentation, and automation into a closed-loop cycle. It autonomously plans, executes, and analyzes experiments to discover or optimize materials with minimal human intervention [8].

- Active Learning: An ML paradigm where the algorithm optimally selects subsequent experiments based on previous results to improve outcomes rapidly. In synthesis, it is used to propose improved follow-up recipes when initial attempts fail [1].

The A-Lab: A Case Study in Autonomous Synthesis

The A-Lab, demonstrated by Szymanski et al., serves as a seminal proof-of-concept for a fully autonomous solid-state synthesis platform [1] [8]. Its workflow and performance metrics provide a concrete template for the field.

Workflow and Performance

Over 17 days of continuous operation, the A-Lab successfully synthesized 41 out of 58 novel, computationally predicted inorganic materials, achieving a 71% success rate [1]. The lab's performance demonstrates the effectiveness of integrating computations, historical knowledge, and robotics.

Table 1: A-Lab Experimental Outcomes Summary

| Metric | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Operation Duration | 17 days | Continuous, autonomous operation |

| Target Materials | 58 | Novel, air-stable inorganic powders identified via the Materials Project and Google DeepMind |

| Successfully Synthesized | 41 | Compounds obtained as majority phase from XRD analysis |

| Overall Success Rate | 71% | Percentage of targets successfully synthesized |

| Recipes from Literature-ML | 35 | Materials obtained using initial recipes from NLP models |

| Targets Optimized via Active Learning | 9 | Targets with yield improved by the ARROWS3 algorithm |

Key Technical Components

The A-Lab's success hinged on several integrated technical components [1] [8]:

- Target Selection: Novel, theoretically stable materials were selected from large-scale ab initio phase-stability databases (Materials Project, Google DeepMind).

- Robotic Synthesis: Three integrated stations handled powder preparation, heating in box furnaces, and characterization.

- Automated Characterization & Analysis: X-ray diffraction (XRD) was used for primary characterization, with ML models and automated Rietveld refinement providing phase identification and weight fractions.

- Closed-Loop Optimization: The active learning algorithm ARROWS3 used observed reaction data and thermodynamic driving forces to propose improved synthesis routes.

NLP and LLM Methodologies for Recipe Generation

The generation of initial synthesis recipes is a primary application of NLP and LLMs in autonomous discovery.

Information Extraction from Literature

Traditional NLP pipelines are used to automatically construct large-scale materials databases. This involves [19]:

- Named Entity Recognition (NER): Identifying and classifying key entities in text, such as material compounds, precursors, and properties.

- Relationship Extraction: Determining the relationships between entities, such as which precursors lead to a specific final material under what conditions (temperature, time).

These pipelines have been applied to extract compounds, synthesis processes, and parameters from decades of scientific publications, forming a structured knowledge base [19].

Recipe Generation via Language Models

The A-Lab utilized NLP models trained on historical synthesis data to generate its initial recipes [1]. The process involves:

- Training on Historical Data: Models are trained on a large database of solid-state syntheses extracted from the literature.

- Similarity Assessment: The model learns to assess "similarity" between a novel target material and known compounds, mimicking a human researcher's approach of basing new attempts on analogous known syntheses [1].

- Precursor and Temperature Selection: A model proposes precursor sets, while a second ML model, trained on heating data from the literature, proposes synthesis temperatures [1].

More recently, LLMs like GPT-4 have shown promise in planning chemical synthesis. They can be used directly for tasks such as [8] [19]:

- Prompt Engineering: Crafting precise instructions to guide the LLM to generate viable synthesis routes.

- Fine-tuning: Adapting a general-purpose LLM on a curated dataset of materials science literature to imbue it with specialized domain knowledge.

- Agents for Automation: LLM-based agents (e.g., Coscientist, ChemCrow) can be given tool-using capabilities to autonomously design, plan, and even control robotic systems to execute synthesis [8].

Experimental Protocols and Workflow

This section details the standard protocols for an autonomous synthesis campaign, as exemplified by the A-Lab.

The following diagram illustrates the integrated, closed-loop workflow of an autonomous laboratory for materials discovery.

Protocol 1: Generating Initial Synthesis Recipes with NLP

Objective: To produce one or more initial solid-state synthesis recipes for a novel target inorganic material using models trained on historical data.

Materials and Data Sources:

- Historical Synthesis Database: A large, text-mined corpus of solid-state synthesis procedures from peer-reviewed literature [1] [19].

- Target Material Formula: e.g., CaFe₂P₂O₉.

- Computational Stability Data: Formation energies and decomposition energies from sources like the Materials Project [1].

Methodology:

- Feature Encoding: Represent the target material in a machine-readable format, often using compositional descriptors or its text-based formula.

- Similarity Search: Use NLP-based similarity metrics (e.g., from word embeddings) to identify known materials in the database that are structurally or compositionally analogous to the target [1] [19].

- Precursor Selection: The ML model proposes precursor sets based on the precursors used for the identified analogous materials. The A-Lab generated up to five initial precursor sets per target [1].

- Condition Prediction: A separate regression model (e.g., trained on heating data) predicts an initial synthesis temperature for the proposed precursors [1].

- Output: A complete synthesis recipe specifying precursor identities, their ratios, and a recommended heating temperature.

Protocol 2: Active Learning-Driven Synthesis Optimization

Objective: To iteratively improve the yield of a target material when initial synthesis recipes fail.

Materials:

- Initial Synthesis Products: XRD patterns and phase analysis from failed attempts.

- Reaction Database: A growing database of observed pairwise solid-state reactions between precursors and intermediates [1].

- Thermodynamic Data: Ab initio computed reaction energies from the Materials Project [1].

Methodology (ARROWS3 Algorithm):

- Pathway Inference: Identify the reaction pathway from the initial experiment. The system recognizes intermediate phases formed during the synthesis.

- Driving Force Calculation: Compute the thermodynamic driving force (in meV/atom) to form the target from the observed intermediates using DFT-calculated formation energies.

- Hypothesis-Driven Recipe Design:

- Avoid Low-Driving Force Intermediates: Prioritize synthesis routes that avoid intermediates with a very small driving force (<50 meV/atom) to form the target, as these often lead to kinetic traps [1].

- Leverage Known Pairwise Reactions: Use the database of observed reactions to predict the products of new precursor combinations without testing them, thereby reducing the experimental search space [1].

- Iteration: The newly designed recipe is executed robotically, and the cycle repeats until the target is obtained with high yield or all possible recipes are exhausted.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Autonomous Solid-State Synthesis

| Category | Item/Component | Function in Autonomous Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Resources | Materials Project/DeepMind DB | Provides target materials and thermodynamic data for stability prediction and reaction driving force calculations [1]. |

| Data & Models | Historical Synthesis Text Corpus | Serves as the training data for NLP/LLM models to learn precursor selection and condition prediction [1] [19]. |

| Robotic Hardware | Powder Dispensing & Mixing Station | Automates the precise weighing and mixing of solid precursor powders, ensuring reproducibility [1]. |

| Automated Box Furnaces | Provides controlled high-temperature environment for solid-state reactions; multiple units enable high-throughput [1]. | |

| Characterization | Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD) | Primary technique for phase identification and quantification in synthesized powders [1] [20]. |

| Analysis Software | ML-based XRD Phase Analysis | Automatically identifies phases and estimates weight fractions from XRD patterns, enabling rapid feedback [1]. |

Protocol 3: Automated Phase Analysis via XRD and Machine Learning

Objective: To autonomously identify phases and quantify the yield of the target material from an XRD pattern.

Materials:

- XRD Pattern: Of the synthesized powder product.

- Reference Patterns: Simulated XRD patterns for the target and potential impurity phases, typically from computed structures (e.g., Materials Project) corrected for DFT error [1].

Methodology:

- Data Collection: The robotic system transfers the ground powder to the diffractometer for automated measurement.

- ML Pattern Analysis: Probabilistic ML models (e.g., convolutional neural networks) trained on experimental structures from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) are used to identify phases present in the pattern [1] [8].

- Quantitative Refinement: Automated Rietveld refinement is performed to confirm the identified phases and calculate precise weight fractions of all phases, including the target yield [1].

- Result Reporting: The calculated weight fraction of the target material is reported to the lab management server to inform the next experimental decision.

Technical Diagrams

NLP Processing Pipeline for Historical Texts

The following diagram outlines the process of using LLMs to generate ground-truth data for improving historical text analysis, a methodology applicable to processing older scientific literature.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant progress, several challenges remain in the widespread deployment of NLP-driven autonomous laboratories.

Key Challenges:

- Data Scarcity and Quality: AI model performance is highly dependent on diverse, high-quality data. Experimental data is often noisy, scarce, and inconsistently reported [8].

- Model Generalization: Most AI models and autonomous systems are specialized for specific reaction types or material systems and struggle to generalize to new domains [8].

- LLM Hallucination: LLMs can generate plausible but chemically incorrect information or references, potentially leading to failed experiments if not properly constrained [8].

- Hardware Integration: A lack of standardized, modular hardware architectures makes it difficult to create flexible platforms that can handle both solid-state and solution-based chemistry [8].

Future Outlook:

- Development of Foundation Models: Training large-scale models across different materials and reactions to improve generalization and transfer learning [8] [19].

- Robust Uncertainty Quantification: Embedding measures of uncertainty in AI predictions to improve decision-making and error handling [8].

- Standardized Data Formats: Community-wide adoption of standardized data formats for experimental data to improve model training and reproducibility [8].

- Advanced LLM Agents: Further development of hierarchical, tool-using LLM agents (e.g., ChemAgents) to more fully automate the entire research process [8].

The solid-state synthesis of inorganic materials, a cornerstone for developing new technologies from batteries to catalysts, has traditionally relied on manual, trial-and-error approaches. These methods are often slow, difficult to reproduce, and represent a significant bottleneck in materials discovery. The emergence of autonomous laboratories represents a paradigm shift, integrating automated robotic platforms with artificial intelligence (AI) to transform research [21]. These systems combine AI models, hardware, and software to execute experiments, interact with robotic systems, and manage data, thereby closing the critical predict-make-measure discovery loop [21]. This technical guide details the core components and methodologies for implementing robotic systems for the automated handling, mixing, and heating of powders, framing them within the broader context of accelerating solid-state materials synthesis.

Fundamental Elements of an Autonomous Laboratory

An autonomous laboratory for solid-state synthesis is an advanced robotic platform equipped with embodied intelligence. To achieve a fully closed-loop operation, several fundamental elements must work synergistically [21]:

- Chemical Science Databases: These databases serve as the backbone, managing and organizing diverse chemical data. They integrate multimodal data from proprietary databases (e.g., Reaxys, SciFinder) and open-access platforms (e.g., PubChem) into an AI-powered framework, providing essential support for experimental design and optimization [21].

- Large-Scale Intelligent Models: Interpretive predictive models and advanced algorithms are crucial for processing data, predicting outcomes, and informing decision-making. Common algorithms used in autonomous laboratories include Bayesian Optimization for minimizing experimental trials, Genetic Algorithms (GAs) for handling large variable spaces, and the SNOBFIT algorithm for combining local and global search strategies [21].

- Automated Experimental Platforms: These are the physical robotic systems that perform the tasks of a human researcher. They encompass hardware for powder handling, mixing, and heating, which will be explored in detail in subsequent sections.

- Integrated Management and Decision Systems: This software layer controls the robotic hardware, manages the experimental workflow, and integrates data from experiments and AI models to make autonomous decisions about subsequent experiments [21].

Robotic Systems for Powder Handling and Manipulation

Handling and manipulating powdered precursors is a primary challenge in solid-state synthesis automation. The unique dynamics of granular media require specialized end-effectors.

Challenges in Powder Manipulation

Powders can be free-flowing or cohesive, each presenting distinct challenges. Free-flowing particles are prone to segregation based on size, shape, and density, while cohesive materials can form agglomerates or lumps, complicating the mixing process [22]. Efficiently scooping nearly all powder from variously sized containers in a single action is critical for throughput and avoiding cross-contamination [23].

Specialized End-Effector Design

The SCU-Hand (Soft Conical Universal Robotic Hand) is a novel end-effector designed to address the challenge of scooping powders from containers of various sizes [23]. Its design principles are a model for creating effective tools for laboratory automation:

- Thinness: The end-effector must have a thin, sheet-like structure to slide easily under the powder without pushing it out of the container.

- Size Reconfiguration: The tool's size must be reconfigurable to accommodate different container geometries.

- Spill Prevention: A concave shape without gaps is ideal for securely holding powder and preventing spillage.

- Anisotropic Stiffness: The material must be flexible enough to deform and maintain contact with the container wall, yet stiff enough to resist buckling under friction during the scooping motion [23].

The SCU-Hand uses a flexible, conical structure that deforms to maintain consistent contact with the container, achieving a scooping performance of over 95% for containers ranging from 67 mm to 110 mm in diameter [23].

Automated Powder Mixing Methodologies

Achieving a homogeneous mixture of precursor powders is critical for the success of subsequent solid-state reactions.

Mixing Mechanisms and Equipment

The primary mechanism for powder mixing in solid-state synthesis is convection, where clumps of particles are shifted relative to one another by the action of the mixer, thereby improving spatial homogeneity [22]. Common laboratory mixers include:

- Tumbling Mixers: Such as V-blenders and double-cone blenders, which rely on the rotation of the container to induce mixing.

- Stirred Vessels: Which use an internal rotating blade or paddle to actively mix the powders.

Scale-up of mixing processes from development to production remains a significant challenge and often relies on manufacturer experience and empirical testing [22].

Integrated Robotic Mixing Systems

Advanced robotic systems integrate mixing directly into an automated workflow. For instance, one integrated solid-phase combinatorial chemistry system uses a 360° Robot Arm (RA) and a Liquid Handler (LH) with a heating/cooling rack to handle the mixing of solid beads and liquids for reactions like peptide synthesis [24]. This system automates tasks such as shaking beads and managing different washing solvents, which are essential for purification during the synthesis process [24].

Robotic Heating and Synthesis Optimization

The heating step, where solid-state reactions occur, is a focal point for AI-driven optimization in autonomous laboratories.

Precursor Selection Algorithms

The selection of optimal precursor powders is a critical step that greatly influences the yield and purity of the final product. The ARROWS3 (Autonomous Reaction Route Optimization with Solid-State Synthesis) algorithm has been developed to automate this process [25]. Unlike black-box optimization, ARROWS3 incorporates physical domain knowledge. It works by:

- Initially ranking precursor sets by their thermodynamic driving force (ΔG) to form the target.

- Proposing experiments across a temperature gradient to map reaction pathways.

- Identifying, via in-situ characterization (e.g., XRD), intermediates that consume the driving force.

- Re-prioritizing precursor sets that avoid these energy-trapping intermediates, thereby retaining a larger driving force (ΔG') for the target material [25].

This approach has been validated by successfully synthesizing target materials like YBa2Cu3O6.5 (YBCO) and metastable Na2Te3Mo3O16 with high purity, while requiring fewer experimental iterations than other methods [25].

Validation via Robotic Synthesis

The value of such algorithms is proven through high-throughput robotic validation. In one study, a new approach to precursor selection, based on analyzing pairwise reactions in phase diagrams, was tested [26]. The Samsung ASTRAL robotic lab synthesized 35 target materials through 224 separate reactions in a few weeks—a task that would manually take months or years. The new method achieved higher purity products for 32 of the 35 target materials, demonstrating the power of combining intelligent precursor selection with robotic synthesis [26].

Integrated Workflows and Data Management

The full power of automation is realized when all steps are integrated into a seamless, closed-loop workflow.

Autonomous Experimentation Workflow

A prime example of an integrated workflow is the Autonomous Robotic Experimentation (ARE) system developed for Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD) [20]. While focused on characterization, its workflow model is directly applicable to synthesis. The system uses a 6-axis robotic arm to automate the entire process from sample preparation to data analysis, illustrating the core closed-loop principle as shown in the diagram below.

Data Analysis and Feedback

A key feature of autonomous systems is the integration of automated data analysis. In the PXRD system, machine learning techniques are used to automatically interpret diffraction data [20]. The results of this analysis feed directly back into the control system, completing the loop and enabling the platform to make informed decisions about subsequent experiments without human intervention [20]. This iterative feedback is the engine of accelerated discovery.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Robotic Solid-State Synthesis

| Item | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Powders | Raw materials containing constituent elements for the target material. Selected based on reactivity and phase diagram analysis. | Synthesis of oxide materials (e.g., battery cathodes, catalysts) [26] [25]. |

| 2-Chlorotrityl Resin | A solid-phase support for combinatorial synthesis, enabling automated washing and separation. | Automated synthesis of nerve-targeting contrast agent libraries [24]. |

| Pd(OAc)₂ / P(o-Tol)₃ / TBAB | Catalytic system (Palladium acetate/Triorthotolylphosphine/Tetrabutylammonium bromide) for facilitating coupling reactions. | Used in a Heck reaction during automated synthesis on a robotic platform [24]. |

| Potassium tert-Butoxide (KOtBu) | A strong base used to drive specific chemical transformations. | Employed under microwave conditions in an automated synthesis sequence [24]. |

| Trifluoroacetic Acid (TFA) / DCM | Cleavage cocktail (20% TFA in Dichloromethane) to release synthesized molecules from solid support beads. | Final cleavage step in solid-phase combinatorial synthesis [24]. |

| Naphthyl-2-oxomethyl-succinyl-CoA | Naphthyl-2-oxomethyl-succinyl-CoA|Anaerobic Degradation | Research-grade Naphthyl-2-oxomethyl-succinyl-CoA for studying anaerobic microbial degradation of naphthalene. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Bunitrolol Hydrochloride | Bunitrolol Hydrochloride, CAS:23093-74-5, MF:C14H21ClN2O2, MW:284.78 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Quantitative Performance Data

The effectiveness of robotic systems is demonstrated through concrete, quantitative data on performance metrics such as time savings, yield, and purity.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of Automated Synthesis Systems

| System / Study Focus | Key Performance Metric | Result | Comparison to Manual Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integrated Robotic Chemistry System [24] | Synthesis time for 20 compounds | 72 hours | 120 hours for manual synthesis (40% time saving) |