Real-Time Insights: How Machine Learning is Revolutionizing In-Line XRD Analysis in Biomedical Research

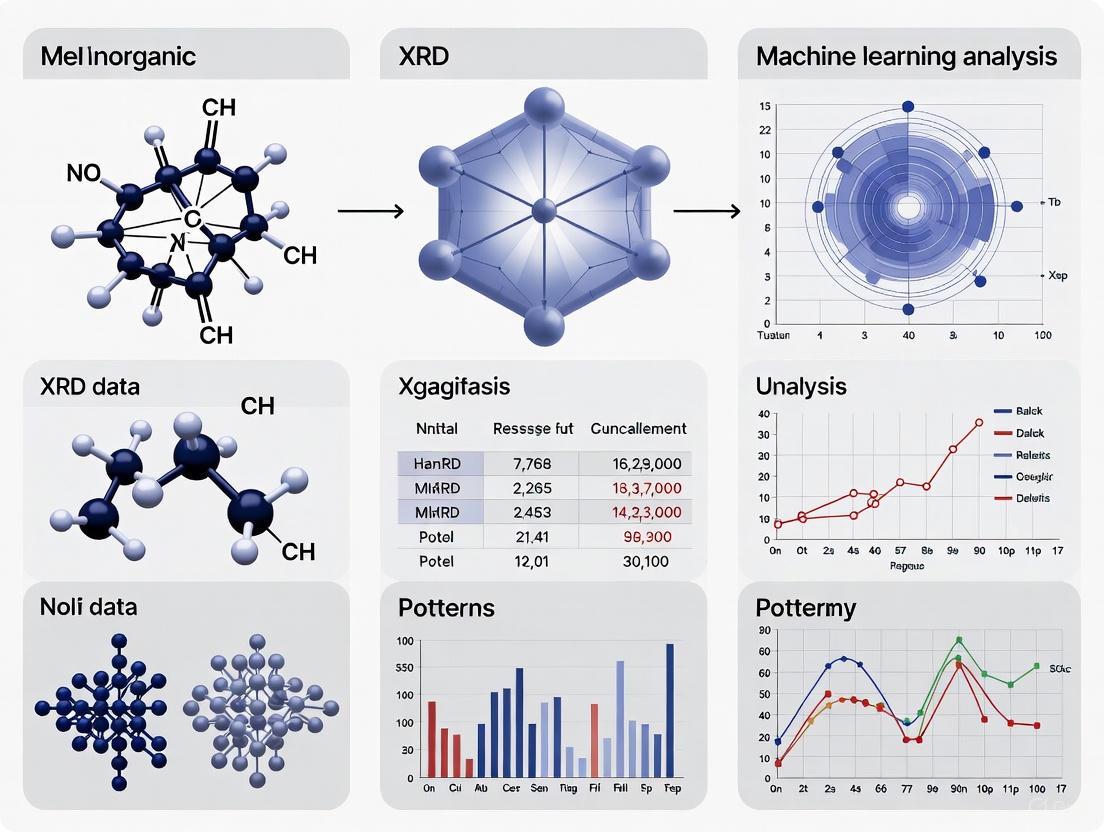

This article explores the transformative integration of machine learning (ML) for the in-line analysis of X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns, a critical technique in materials science and drug development.

Real-Time Insights: How Machine Learning is Revolutionizing In-Line XRD Analysis in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article explores the transformative integration of machine learning (ML) for the in-line analysis of X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns, a critical technique in materials science and drug development. It covers the foundational principles of XRD and the drivers for ML adoption, details specific algorithms and their applications in phase identification and quantification, addresses key challenges like data quality and model interpretability, and provides a comparative analysis of ML performance against traditional methods. Aimed at researchers and pharmaceutical professionals, this review synthesizes current advancements to demonstrate how real-time, ML-driven XRD analysis accelerates discovery, enhances quality control, and paves the way for personalized medicine.

The New Paradigm: Foundations of Machine Learning in XRD Analysis

X-ray diffraction (XRD) stands as one of the most powerful non-destructive analytical techniques for determining the structure of crystalline materials. By providing unparalleled insights into atomic and molecular arrangements, XRD has revolutionized materials characterization across scientific disciplines from solid-state chemistry to pharmaceutical development [1]. The technique's foundation rests on the simple but profound physical phenomenon of X-ray beams changing direction through interactions with atomic electrons, creating distinctive diffraction patterns that serve as unique fingerprints for material identification and structural analysis [1].

The integration of machine learning (ML) with XRD represents a paradigm shift in materials characterization, enabling automated interpretation of experimental results and adaptive experimentation [2] [3]. This synergy allows for real-time analysis and decision-making during data collection, dramatically accelerating the pace of materials discovery and optimization [3]. As ML algorithms become increasingly sophisticated, their application to XRD pattern analysis promises to transform how researchers extract meaningful structural information from crystalline materials, particularly in complex multi-phase systems common in pharmaceutical development and advanced materials research [2].

Core Principles of X-ray Diffraction

Fundamental Concepts

XRD analysis leverages the wave nature of X-rays, which are electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths (typically 0.1-10 nm) comparable to the spacing between atoms in crystal structures [1]. When monochromatic X-rays interact with a crystalline sample, they scatter in all directions from the electrons around atoms. However, constructive interference occurs only at specific angles where scattered waves remain in phase, generating the characteristic diffraction pattern from which structural information is derived [1] [4].

The essential requirements for XRD analysis include: (1) a monochromatic X-ray source, most commonly using copper (Cu Kα, λ = 1.54 Å) or molybdenum (Mo Kα, λ = 0.71 Å) targets; (2) a crystalline material with long-range periodic atomic arrangement to produce sharp diffraction peaks; and (3) precise geometric arrangement of the X-ray source, sample, and detector to accurately measure diffraction angles [1]. Modern diffractometers employ sophisticated goniometers and alignment systems to maintain these precise angular relationships throughout measurement.

Bragg's Law

The fundamental equation governing XRD was formulated by William Lawrence Bragg in 1913 and bears his name [1] [4]. Bragg's Law describes the conditions necessary for constructive interference of X-rays scattered by parallel crystal planes:

nλ = 2d sin θ

Where:

- n = order of diffraction (integer: 1, 2, 3...)

- λ = X-ray wavelength, typically 1.5418 Å for copper Kα radiation

- d = interplanar spacing, the perpendicular distance between parallel crystal planes

- θ = Bragg angle, the angle between the incident X-ray beam and crystal plane [1] [4] [5]

This relationship demonstrates that when X-rays strike a crystalline solid with periodic atomic arrangements, they can constructively interfere to produce diffracted beams at specific angles [4]. The path difference between X-rays scattered from parallel crystal planes must equal an integer multiple of the X-ray wavelength for constructive interference to occur [1].

Table 1: Key Applications of Bragg's Law in XRD Analysis

| Application | Description | Practical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| d-spacing determination | Calculate distances between crystal planes using diffraction angles | Essential for understanding crystal structures and identifying unknown phases |

| Unit cell dimension measurement | Precise determination of lattice parameters through multiple peak measurements | Critical for structural characterization and detecting subtle structural changes |

| Strain and stress analysis | Track d-spacing changes under mechanical or thermal stress | Enables residual stress measurement in manufactured components |

| Phase transformation monitoring | Observe d-spacing shifts during thermal or chemical treatment | Provides insights into material stability and transformation pathways |

The historical significance of Bragg's Law extends to landmark scientific discoveries, most notably the determination of DNA's double helix structure. Rosalind Franklin's XRD work at King's College London provided quantitative data from which Watson and Crick proposed their revolutionary DNA model. Franklin's analysis of "Photo 51" revealed the 3.4 Ã… spacing between consecutive base pairs, the 34 Ã… helical repeat distance for one complete turn, and the 20 Ã… diameter of the DNA double helix [1].

XRD Pattern Fundamentals

An XRD pattern displays diffraction intensity versus diffraction angle (2θ), where each peak corresponds to a specific set of parallel crystal planes characterized by Miller indices (hkl) [1]. This diffraction pattern serves as a unique fingerprint for each crystalline phase, enabling both identification and quantitative analysis.

Table 2: Information Contained in XRD Pattern Characteristics

| Pattern Feature | Structural Information | Analytical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Peak position | Determines d-spacing through Bragg's law; identifies lattice parameters | Phase identification; detection of structural changes due to composition, temperature, or pressure variations |

| Peak intensity | Indicates atomic arrangement and relative phase abundance | Quantitative phase analysis; information about preferred orientation effects |

| Peak width | Reveals crystal quality, crystallite size, and microstrain effects | Assessment of material quality; narrower peaks indicate large, well-formed crystals with minimal strain |

| Peak shape | Provides insights into crystal defects, stacking faults, and structural imperfections | Detection of compositional gradients or structural distortions |

The specific characteristics of an XRD pattern depend considerably on the nature of the sample. Single-crystal XRD produces a pattern of very defined, isolated spots on the detector, with each spot's location and intensity enabling calculation of the full atomic arrangement [1]. In contrast, powder XRD of microcrystalline samples produces concentric rings known as Debye rings, resulting from the random orientation of crystallites [1] [6]. For polycrystalline or powdered samples, the detector typically scans in one direction perpendicular to the Debye rings to gather peak intensity information, creating the standard diffractogram used for most analytical applications [1].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

XRD Instrumentation

A modern X-ray diffractometer consists of several essential components working in coordination to produce high-quality diffraction data [1] [6]:

XRD Instrument Workflow

The X-ray source generates monochromatic X-rays through electron bombardment of a metal target, with most common sources using copper (characteristic Kα radiation, λ = 1.5418 Å) or molybdenum targets [1] [6]. The incident beam optics, including Soller slits, monochromators, and focusing mirrors, condition the X-ray beam to control divergence and wavelength characteristics [1]. The sample stage holds the specimen and allows precise positioning and rotation during measurement, while the detector system captures diffracted X-rays—modern diffractometers typically employ position-sensitive detectors (PSDs) or area detectors that simultaneously collect data over a range of angles [1]. The goniometer serves as the precision mechanical system controlling angular relationships between X-ray source, sample, and detector, with modern systems achieving angular accuracy better than 0.001° [1].

XRD Techniques and Configurations

Different experimental configurations address specific analytical needs and sample types:

Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD): Ideal for polycrystalline or powdered samples, this most frequently used XRD technique produces patterns for phase identification, quantification, and lattice parameter determination [5]. The random orientation of crystallites in the sample causes X-rays to diffract in various directions, creating a characteristic pattern of concentric Debye rings [1] [6].

Single-crystal X-ray Diffraction (SCXRD): Used to determine detailed atomic structure by analyzing how X-rays are diffracted by a single crystal [5]. This technique is particularly valuable for studying three-dimensional atomic arrangements in molecules, including organic compounds and biological macromolecules like proteins [6] [5].

Grazing-Incidence X-ray Diffraction (GIXRD): Employed for studying thin films and surfaces by directing the X-ray beam at a shallow angle to the sample [5]. This configuration is particularly useful for analyzing coatings, surface layers, and nanomaterials where surface structure may differ from the bulk material [6] [5].

Small-Angle X-ray Scattering (SAXS): Used when scattering angles are small (typically less than 10°), enabling investigation of larger structural features with dimensions between 3 and 100 nm, such as nanoparticles, pores, or periodic structures in self-assembled systems [6].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful XRD analysis requires specific materials and reagents to ensure accurate and reproducible results:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for XRD Analysis

| Item | Function | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Standard reference materials | Instrument calibration and quantitative analysis | Certified crystalline powders (e.g., NIST standards) with known lattice parameters |

| Sample holders | Secure presentation of samples to X-ray beam | Low-background holders; zero-background silicon plates for minimal scattering |

| Sample preparation kits | Homogeneous powder preparation | Agate mortars and pestles for grinding; sieves for particle size control (<45 μm recommended) |

| X-ray tubes | Source of monochromatic X-rays | Copper (λ = 1.5418 Å) for general use; molybdenum (λ = 0.71 Å) for heavy elements |

| Calibration standards | Verify instrument alignment and performance | Corundum (Al₂O₃) or silicon powders for angle and intensity calibration |

Proper sample preparation is critical for obtaining high-quality XRD data. Samples should be ground to fine powders (<45 μm) to minimize micro-absorption effects, ensure reproducible peak intensities, and reduce preferred orientation [7]. Homogenization through careful mixing (typically 30 minutes in an agate mortar) ensures representative sampling, while uniform packing into sample holders prevents orientation biases [7].

Quantitative XRD Analysis Methods

Comparative Methodologies

Several analytical approaches have been developed for extracting quantitative information from XRD patterns, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

Table 4: Comparison of Quantitative XRD Analysis Methods

| Method | Principle | Accuracy | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Intensity Ratio (RIR) | Uses intensity of strongest diffraction peak with RIR values | Lower analytical accuracy; handy approach | Rapid screening; quality control |

| Rietveld Refinement | Fitting of experimental pattern by modifying parameters based on crystal structure model | High accuracy for non-clay samples; struggles with disordered structures | Complex crystalline materials; structure determination |

| Full Pattern Summation (FPS) | Summation of reference library patterns to match observed data | Wide applicability; appropriate for sediments | Complex mixtures; clay-containing samples |

The Rietveld method represents a particularly powerful approach for quantitative analysis, functioning as a process of refinement between observed and calculated patterns by partial least squares regression based on a crystal structure database [7]. This method determines the weight of each phase in a sample from the optimal value of the scale factor during refinement, with quality of fit assessed using standard agreement indices (Rp, Rwp, Rexp) and goodness of fit (GOF) metrics [7].

Recent research comparing these quantitative methods reveals that analytical accuracy is generally consistent for mixtures free from clay minerals. However, significant differences emerge for samples containing clay minerals, with the FPS method demonstrating wider applicability for sedimentary materials [7]. The uncertainty of a reliable quantitative XRD method should generally be less than ±50X−0.5 at the 95% confidence level, accounting for weighting errors, counting statistics, and instrument errors [7].

Machine Learning-Enhanced XRD Analysis

The integration of machine learning with XRD represents a transformative advancement in materials characterization. ML algorithms, particularly convolutional neural networks, can be trained to identify crystalline phases from XRD patterns with remarkable speed and accuracy [2] [3]. This capability enables the development of adaptive XRD systems where early experimental information guides subsequent measurements toward features that improve model confidence in phase identification [3].

Machine Learning-Driven XRD Workflow

The adaptive XRD approach integrates machine learning directly with the diffraction experiment, creating a closed-loop system where data collection and analysis inform each other in real time [3]. This methodology begins with a rapid initial scan over a limited angular range (typically 2θ = 10°-60°), which conserves measurement time while including sufficient peaks for preliminary phase prediction [3]. The ML algorithm then assesses its own confidence level, with values below a predetermined threshold (typically 50%) triggering additional data collection through either resampling of specific angular ranges with increased resolution or expansion of the angular range to detect additional peaks [3].

Class Activation Maps (CAMs) play a crucial role in guiding the resampling process by highlighting features in the XRD pattern that contribute most to the classification decisions made by the deep learning model [3]. Rather than resampling the most intense peaks, the algorithm prioritizes regions where the difference between CAMs of the most probable phases exceeds a defined threshold, focusing measurement effort on peaks that distinguish between structurally similar phases [3].

This ML-driven approach demonstrates particular value for detecting trace amounts of materials in multi-phase mixtures and identifying short-lived intermediate phases during in situ studies of dynamic processes like solid-state reactions [3]. By optimizing data collection to maximize information gain, adaptive XRD can achieve confident phase identification with significantly shorter measurement times compared to conventional approaches [3].

Applications in Pharmaceutical and Materials Research

Pharmaceutical Applications

XRD plays a crucial role in pharmaceutical development, particularly in polymorph identification and characterization. Different crystalline forms (polymorphs) of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) can exhibit significantly different solubility, stability, and bioavailability properties, making their identification and quantification essential for drug development and formulation [5]. XRD provides the definitive method for distinguishing between these polymorphic forms, enabling pharmaceutical scientists to ensure consistent product quality and performance [1] [5].

Non-ambient XRD analysis offers particular value for studying moisture influence on drug properties and monitoring phase transformations under various temperature and humidity conditions [2]. This capability is especially important for understanding drug behavior during storage and administration, where environmental factors may trigger undesirable polymorphic transitions that affect product efficacy and safety.

Advanced Materials Characterization

In materials science, XRD enables comprehensive characterization of crystalline phases, crystallite size, microstrain, and preferred orientation in diverse material systems [1] [5]. These structural parameters directly influence material properties and performance in applications ranging from electronics and energy storage to construction and aerospace [1].

The technique's non-destructive nature makes it particularly valuable for in situ and operando studies, where materials are characterized under realistic operating conditions. For battery materials, operando XRD tracks phase transformations during electrochemical cycling, providing mechanistic insights into performance degradation and failure mechanisms [3]. Similarly, in situ XRD monitors solid-state reactions in real time, capturing transient intermediate phases that often determine reaction pathways and final products [3].

The integration of ML with XRD analysis accelerates materials discovery by enabling high-throughput screening and automated interpretation of complex diffraction data [2] [3]. As these methodologies continue to develop, they promise to unlock new opportunities for adaptive experimentation and autonomous materials research, potentially revolutionizing how scientists approach materials design and optimization.

The advent of high-throughput synthesis and characterization methodologies has fundamentally transformed materials science, combinatorial chemistry, and pharmaceutical development. Central to this transformation is X-ray diffraction (XRD), a powerful non-destructive analytical technique that provides detailed information on the lattice structure and long-range order in crystalline materials [1]. However, current data generation capabilities through techniques such as in situ XRD far surpass human analytical capacities, potentially leading to significant loss of critical insights [8]. Modern beamlines and automated laboratories can generate terabytes of data in a single experiment, creating a "data deluge" that traditional analysis methods cannot handle efficiently [9]. This overwhelming volume of data has necessitated a paradigm shift from manual analysis to automated, intelligent systems capable of extracting meaningful information at scale and in real time.

The integration of machine learning (ML), particularly deep learning models, into XRD analysis represents a fundamental advancement in how researchers process and interpret structural information. While conventional analysis methods like Rietveld refinement provide theoretically accurate results, they require significant manual intervention, contextual insights from verified materials, and extensive processing time [8] [9]. The discrepancy between the rapid pace of data generation and the slow, expertise-dependent analysis has created a critical bottleneck in materials discovery pipelines. This application note examines how ML technologies are addressing these challenges, providing detailed protocols for implementation, and enabling new capabilities in high-throughput experimental environments.

The Data Challenge: Volume, Velocity, and Variety in XRD Data

Scale of the Data Generation Challenge

The data deluge in XRD is characterized by three key dimensions: volume, velocity, and variety. Advances in ultrafast synchronous X-ray diffraction and spectroscopy measurements now generate big datasets from millions of measurements, far exceeding what human experts can manually analyze [8]. Synchrotron facilities with fourth-generation beamlines and specialized laboratory diffractometers have dramatically increased options for high-throughput, in situ, and operando experiments [9]. A single combinatorial library can contain hundreds to thousands of compositionally varying samples, each requiring rapid structural characterization to establish composition-structure-property relationships [10]. This massive scale of data production makes human-only analysis impractical and incompatible with autonomous synthesis-characterization-analysis loops.

Limitations of Conventional Analysis Methods

Traditional XRD analysis methods face significant limitations in high-throughput environments. Rietveld refinement requires manual tuning and adjustments such as peak indexing and parameter initialization for trial-and-error iterations [8]. These parameters are initialized using known contextual knowledge such as expected material symmetries, beam source, crystal, temperature, and grain size. Automatic classifying software such as TREOR lacks the accuracy needed for reliable automated material characterization as it ultimately relies on human intervention [8]. Furthermore, initialization steps can be extremely difficult to establish with the presence of a small number of impurity phases that cause overlapping peaks with the main phase. These limitations become particularly problematic when characterizing materials with no available contextual knowledge, making classification even more difficult, time-consuming, and inaccurate.

Table 1: Comparison of XRD Analysis Methods in High-Throughput Environments

| Analysis Method | Throughput | Accuracy | Automation Level | Expertise Required |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manual Rietveld Refinement | Low (hours-days/sample) | High | Minimal | Expert crystallographer |

| Traditional Auto-indexing | Medium (minutes-hours/sample) | Medium | Partial | Experienced researcher |

| Machine Learning Classification | High (seconds/sample) | High | Full | Domain knowledge helpful |

| Deep Learning Phase Mapping | Very High (real-time potential) | High | Full | Minimal after training |

Machine Learning Solutions for XRD Analysis

Deep Learning for Crystal Structure Classification

Deep learning models have emerged as powerful tools for classifying crystal systems and space groups from XRD patterns. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) can overcome the limitations of rule-based methods because of their thousands of tunable parameters that are optimized using big data, allowing models to make predictions based on learned representations from the data [8]. For a model to correctly characterize materials and material transformations, the model must be generalized—having the ability to accurately classify a wide array of materials beyond the training data. Current research focuses on developing models robust enough to classify the crystal system (7-way classification) and space group (230-way classification) of materials encountered in cutting-edge material design [8].

Successful implementation requires sophisticated training strategies using augmented synthetic datasets comparable to real experimental XRD data. This enhances the model's ability to classify patterns irrespective of noise, small peak shifts due to atomic impurities, grain size, and pattern variations due to instrumental parameters [8]. Model architectures must be specifically designed and hyper-parameters tuned to develop models that best fit XRD analysis, with the explicit purpose of instilling scientific classification strategies based on real physics. Adaptation techniques can further teach models to account for experimental factors not captured in synthetic data.

Automated Phase Mapping in Combinatorial Libraries

Combinatorial libraries containing large numbers of compositionally varying samples enable rapid screening within specific composition spaces, facilitating identification of promising candidate materials with desired properties [10]. Correctly extracting information about constituent phases from high-throughput XRD data of these combinatorial libraries is a crucial step in establishing composition-structure-property relationships. Automated phase mapping algorithms must determine basic information including the number, identity, and fraction of present phases in all samples, while advanced information includes lattice change, texture information, and solid solution behavior [10].

Unsupervised optimization-based solvers can tackle the phase mapping challenge in high-throughput XRD datasets by integrating various material information, including first-principles calculated thermodynamic data, crystallography, XRD, and texture [10]. Encoding domain-specific knowledge as constraints into a loss function for optimization is key to successful automated phase mapping algorithms. These approaches demonstrate robust performance across multiple experimental datasets and contribute to the development of future automated characterization tools.

Table 2: Key ML Approaches for XRD Analysis and Their Applications

| ML Approach | Architecture | Primary Application | Reported Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crystal System Classification | Deep CNN | 7-class crystal system identification | ~98% on synthetic data [8] |

| Space Group Classification | Deep CNN | 230-class space group identification | State-of-the-art performance [8] |

| Automated Phase Mapping | Optimization-based neural networks | Constituent phase identification in combinatorial libraries | Robust performance across experimental datasets [10] |

| Pattern Demixing | Deep reasoning networks | Phase identification with scientific knowledge constraints | Experimentally validated [10] |

Experimental Protocols for ML-Enhanced XRD Analysis

Protocol: Developing a Generalized Deep Learning Model for XRD Classification

Purpose: To create a deep learning model capable of classifying crystal systems and space groups from XRD patterns with high accuracy and generalizability to experimental data.

Materials and Equipment:

- Computational resources (GPU recommended for training)

- Python programming environment with deep learning frameworks (TensorFlow, PyTorch)

- Crystallographic information files from databases (ICSD, COD)

- XRD simulation software for training data generation

Procedure:

- Data Collection and Curation: Collect a total of 204,654 crystallographic information files from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD). Remove incomplete or duplicated structures for a final count of approximately 171,006 entries [8].

- Synthetic Data Generation: Generate multiple synthetic datasets (7 recommended) with unique Caglioti parameters and noise implementations to represent patterns emerging from varying experimental conditions and crystal properties. Combine all synthetic datasets to create a large training dataset of approximately 1.2 million data points [8].

- Model Architecture Design: Implement convolutional neural network architectures specifically designed for XRD pattern analysis. Optimize model architecture to elicit classification based on Bragg's Law rather than relying solely on pattern recognition [8].

- Training Strategy: Employ expedited learning techniques to refine model expertise to experimental conditions. Use the mixed dataset approach, randomly sampled without replacement from multiple synthetic datasets [8].

- Model Evaluation: Evaluate models using three distinct evaluation datasets not engaged in training: experimental RRUFF dataset (908 entries), MP Dataset from Materials Project (2253 materials), and Lattice Augmented dataset with manually altered lattice constants [8].

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If model performance on experimental data is poor, increase the diversity of synthetic training data with more variations in experimental conditions.

- For class imbalance issues, employ weighted loss functions or oversampling techniques for underrepresented crystal classes.

- If model interpretations lack physical basis, incorporate physics-based constraints into the loss function.

Protocol: Automated Phase Mapping for Combinatorial Libraries

Purpose: To automatically identify constituent phases, their fractions, and lattice parameters in high-throughput XRD datasets from combinatorial libraries.

Materials and Equipment:

- High-throughput XRD dataset from combinatorial library

- Candidate phase information from ICDD and ICSD databases

- Thermodynamic data from first-principles calculations

- Computational resources for optimization

Procedure:

- Candidate Phase Identification: Collect all relevant candidate phases in the investigated chemistry system from ICDD and ICSD databases. Include only chemically plausible phases (e.g., oxides for libraries prepared under ambient conditions) [10].

- Thermodynamic Filtering: Eliminate highly thermodynamically unstable phases based on first-principles calculations (e.g., energy above convex hull >100 meV/atom) [10].

- Data Preprocessing: Perform background removal using the rolling ball algorithm on raw XRD data. Retain diffraction peaks from substrates during solving process rather than subtracting them prematurely [10].

- Loss Function Formulation: Create a weighted loss function with three components: LXRD (quantifies fitting quality using weighted profile R-factor), Lcomp (describes consistency between reconstructed and measured composition), and Lentropy (entropy-based regularization to mitigate overfitting) [10].

- Iterative Solving: Solve phase fractions of all constituent phases and peak shifts with an encoder-decoder structure by minimizing the loss. Begin with "easy" samples containing only one or two major phases before progressing to "difficult" samples at phase region boundaries with three or more major phases [10].

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If solutions lack "chemical reasonableness," increase weight of composition constraint in loss function.

- For difficult samples trapped in local minima, use solutions from similar compositions as initialization.

- If texture effects are significant, incorporate texture modeling into the pattern simulation.

Workflow Visualization: ML-Integrated XRD Analysis

ML-Integrated XRD Analysis Workflow

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for ML-Enhanced XRD Analysis

| Category | Specific Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crystallographic Databases | Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) | Source of ground-truth crystal structures for training | Synthetic data generation [8] |

| Crystallographic Databases | Crystallography Open Database (COD) | Open-access crystal structure repository | Model training and validation [9] |

| Experimental Data Repositories | RRUFF Project | Collection of experimentally verified XRD data | Model evaluation on real patterns [8] |

| Experimental Data Repositories | Materials Project | Computational and experimental materials data | Evaluation on novel material systems [8] |

| ML Frameworks | TensorFlow/PyTorch | Deep learning model development | Implementing custom architectures [8] [11] |

| XRD Simulation | pymatgen, XRD simulation tools | Synthetic pattern generation | Training data augmentation [8] |

| Optimization Tools | Scientific Python stack (SciPy, NumPy) | Loss function optimization | Phase mapping algorithms [10] |

Advanced Applications and Implementation Considerations

Neural Network Architecture for XRD Analysis

Deep Learning Architecture for XRD Classification

Implementation Challenges and Solutions

Successfully implementing ML solutions for high-throughput XRD analysis requires addressing several key challenges. Data quality and variability present significant hurdles, as experimental XRD patterns are affected by numerous factors including instrumental parameters, sample preparation, impurities, grain size, and preferred crystal orientation [8] [1]. Models must be robust to these variations while maintaining high classification accuracy. Integration of physical principles represents another critical challenge, as purely data-driven approaches may produce unphysical results. Encoding domain knowledge such as crystallographic constraints, thermodynamic stability, and composition rules into ML models is essential for generating scientifically valid solutions [10].

Interpretability and trust in model predictions remain crucial for widespread adoption in materials research. Unlike traditional analysis methods where experts can follow the reasoning process, deep learning models often function as "black boxes." Recent approaches address this by designing architectures that elicit classification based on Bragg's Law and using evaluation data to interpret model decision-making [8]. Computational efficiency must also be balanced with accuracy, particularly for real-time analysis applications. While complex models may offer superior performance, simplified architectures often provide better scalability for high-throughput environments.

The integration of machine learning with high-throughput X-ray diffraction analysis represents a transformative advancement in materials characterization, combinatorial chemistry, and pharmaceutical development. As high-throughput experimental methodologies continue to generate data at unprecedented scales, ML technologies provide the necessary tools to extract meaningful insights from this deluge of information. The protocols and methodologies outlined in this application note demonstrate robust approaches for implementing ML-enhanced XRD analysis, enabling researchers to overcome the limitations of traditional analysis methods. By leveraging deep learning for crystal structure classification, automated phase mapping, and real-time pattern analysis, research institutions and industrial laboratories can significantly accelerate their materials discovery and optimization pipelines. The continued development of physics-informed ML models, coupled with the growing availability of high-quality materials data, promises to further enhance the capabilities and applications of these powerful analytical tools.

The analysis of X-ray diffraction (XRD) data is undergoing a profound transformation, moving from traditional, labor-intensive methods toward fully automated, intelligent systems. For decades, Rietveld refinement has served as the cornerstone technique for determining crystal structures from powder XRD data, enabling researchers to extract detailed structural information through iterative fitting of whole diffraction patterns [12]. This method, while powerful, demands substantial expert knowledge, significant computational resources, and extensive manual intervention, creating bottlenecks in high-throughput materials discovery and characterization [13] [14]. The recent integration of machine learning (ML), particularly deep neural networks, is revolutionizing this field by enabling direct, rapid inference of crystal structures from diffraction patterns with minimal human input [13] [15] [14].

This methodological evolution is occurring within a broader context of increasingly automated materials research. The fourth-generation synchrotron radiation sources have significantly improved the resolution and sensitivity of XRD analysis, while advances in laboratory technology are driving greater automation and self-operation [15]. These developments have created an urgent need to modernize traditional analytical methods, positioning ML-powered XRD analysis as a critical enabler for next-generation materials discovery and characterization, particularly for applications requiring rapid iteration such as pharmaceutical development and functional materials design [15] [2].

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional and ML-Based XRD Analysis Methodologies

| Feature | Traditional Rietveld Approach | ML-Based Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Time Requirements | Hours to days for refinement [14] | Seconds to minutes for structure determination [13] |

| Expertise Demands | High (requires crystallographic expertise) [13] [12] | Low (automated end-to-end pipelines) [13] [14] |

| Automation Level | Manual intervention at multiple stages [13] | Fully automated structure solution [13] [14] |

| Data Requirements | Works with individual patterns | Requires large training datasets [16] [15] |

| Uncertainty Quantification | Statistical metrics from refinement [12] | Bayesian confidence estimates [15] |

Fundamental Principles: From Bragg's Law to Neural Networks

Traditional XRD Analysis Foundations

Traditional XRD analysis rests firmly on Bragg's Law (nλ = 2d·sinθ), which establishes the fundamental relationship between the diffraction angle (θ), the X-ray wavelength (λ), and the interplanar spacing (d) in crystalline materials [2]. This physical principle enables the determination of crystal structures by analyzing the positions and intensities of diffraction peaks in the measured pattern. The Rietveld refinement method, developed in 1969, leverages this foundation by using a non-linear least squares approach to minimize the difference between observed and calculated diffraction patterns [12]. This process iteratively adjusts structural parameters (atomic positions, thermal parameters, lattice constants) and profile parameters to achieve an optimal fit, typically requiring good initial estimates and considerable crystallographic expertise [12].

The traditional workflow encompasses three distinct stages: (1) unit cell determination through pattern indexing, (2) structure solution to obtain initial atomic coordinates, and (3) structure refinement to optimize the model against experimental data [13]. This multi-step process presents significant challenges, particularly for powder XRD data, where the compression of three-dimensional structural information into one-dimensional diffraction patterns causes loss of phase information and creates ambiguities in interpretation [16] [14]. These challenges are exacerbated by peak overlapping, preferred orientation effects, and the presence of impurities or defects [13] [2].

Machine Learning Fundamentals for XRD

Machine learning approaches to XRD analysis fundamentally reinterpret the structure determination problem as a pattern recognition task rather than a physical modeling problem. Instead of explicitly applying Bragg's Law and structure factor calculations, ML models learn the complex relationships between diffraction patterns and crystal structures through exposure to large datasets of paired examples (structures and their corresponding patterns) [13] [16]. This represents a shift from first-principles physics to data-driven inference, enabling the model to capture subtle correlations that might be difficult to formalize in explicit physical models.

The core advantage of ML approaches lies in their ability to perform end-to-end structure determination, bypassing the sequential, error-propagating workflow of traditional methods [13]. Modern architectures like PXRDGen integrate diffraction pattern encoding, structure generation, and refinement into a single, unified framework that operates in seconds rather than hours [13]. These systems typically employ contrastive learning to align the latent representations of XRD patterns and crystal structures, then use generative models (diffusion or flow-based) to produce atomically accurate structures conditioned on the encoded diffraction information [13].

Experimental Protocols & Application Notes

Traditional Rietveld Refinement Protocol

Materials & Software Requirements:

- High-quality powder XRD data (Cu Kα source, 5-90° 2θ range recommended)

- Rietveld refinement software (GSAS-II, FullProf, TOPAS, or powerxrd)

- Initial structural model with estimated lattice parameters and space group

- Computer with sufficient processing power for iterative refinement

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Data Preparation and Preprocessing

- Import raw XRD data and convert to appropriate format (XY pairs of intensity vs. 2θ)

- Apply background subtraction using automated algorithms or manual selection of background points [12]

- Remove Kα2 component if present using appropriate stripping algorithms

- Correct for sample displacement and other instrumental aberrations

Initial Parameter Estimation

- Determine initial lattice parameters from peak positions using indexing algorithms

- Identify possible space groups from systematic absences

- Input known structural fragments or similar structures as starting model

- Initialize profile parameters (U, V, W for Cagliotti polynomial) based on instrumental characteristics [12]

Sequential Refinement

- Begin by refining only scale factor parameters to match overall intensity [12]

- Progressively add lattice parameters (a, b, c, α, β, γ) to refinement [12]

- Incorporate profile parameters (U, V, W) and background terms [12]

- Finally, refine atomic coordinates and thermal parameters

- Monitor R-factors (Rp, Rwp) to track refinement progress and avoid overfitting

Validation and Quality Assessment

- Examine difference plot (Iobs - Icalc) for systematic errors

- Verify chemical reasonableness of bond lengths and angles

- Check for parameter correlations and stability

- Generate final report with crystallographic information file (CIF) for publication [17]

Troubleshooting Notes:

- If refinement diverges, return to previous stable model and refine parameters more gradually

- Apply constraints or restraints to maintain chemical reasonableness

- For problematic regions, consider excluding specific angular ranges temporarily

- Use regularization methods or parameter limits to prevent unphysical values [17]

ML-Based Structure Determination Protocol

Materials & Software Requirements:

- Pre-trained model (PXRDGen, DiffractGPT, or similar)

- XRD pattern in digital format (1D vector or 2D radial image)

- Chemical information (formula or element list) if required by model

- GPU acceleration recommended for rapid inference

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Data Preparation for ML Processing

- Convert raw XRD data to appropriate input format for target model

- For 1D inputs: Interpolate to standardized angular range (typically 5-90° 2θ) with fixed number of points (e.g., 1024 points) [16]

- For 2D inputs: Transform 1D pattern to radial image using mathematical transformation [16]

- Normalize intensity values to [0,1] range based on maximum intensity [16]

- Apply noise augmentation if required for robustness to experimental data

Model Loading and Configuration

- Load pre-trained weights for appropriate architecture (Transformer-based encoders generally outperform CNN for retrieval tasks) [13]

- Configure conditional generation parameters based on available information:

- Scenario A: No chemical information - structure from pattern only

- Scenario B: Element list available - constrained generation

- Scenario C: Exact formula known - most accurate prediction [14]

- Set sampling parameters (number of candidate structures to generate)

Structure Generation and Selection

- Execute forward pass through neural network to generate candidate structures

- For diffusion/flow models: Generate multiple samples (20 samples achieve 96% matching rate) [13]

- Rank candidates by similarity score between experimental and calculated pattern

- Select top candidate based on combined score including chemical feasibility

Validation and Uncertainty Quantification

Troubleshooting Notes:

- For poor predictions with known chemistry, verify formula input correctness

- If radial images produce artifacts, check transformation parameters [16]

- For experimental data, ensure preprocessing matches training data characteristics

- Consider ensemble methods with multiple models to improve robustness

Protocol for Hybrid Traditional-ML Approach

Materials & Software Requirements:

- ML model for initial structure solution

- Traditional refinement software for final optimization

- Data exchange format (CIF) for transferring structures between applications

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Rapid ML-Based Structure Solution

- Use ML model (PXRDGen or DiffractGPT) to generate initial structural model

- Generate multiple candidates (5-20 structures) and select best match

- Export top candidate as CIF file for further refinement

Validation and Refinement Using Traditional Methods

- Import ML-generated structure into refinement software (GSAS-II)

- Perform constrained Rietveld refinement starting from ML solution

- Use standard refinement protocols to optimize all parameters

- Validate final structure using established crystallographic metrics

Quality Assessment and Reporting

- Compare final R-values with ML-only solution

- Document time savings compared to traditional ab initio structure solution

- Generate publication-quality figures and CIF files

Data Presentation & Comparative Analysis

Table 2: Performance Metrics of ML Models for XRD Structure Determination

| Model | Architecture | Dataset | Accuracy/Match Rate | Inference Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PXRDGen | Diffusion/flow + Transformer encoder | MP-20 (inorganic) | 82% (1-sample), 96% (20-samples) [13] | Seconds [13] |

| DiffractGPT | Transformer (Mistral-based) | JARVIS-DFT (80k materials) | Varies with chemical information provided [14] | Fast training and inference [14] |

| B-VGGNet | Bayesian VGGNet | Perovskites (TER-generated) | 84% (simulated), 75% (experimental) [15] | Not specified |

| Computer Vision Models | ResNet, Swin Transformer | SIMPOD (467k structures) | Accuracy correlates with model complexity [16] | Not specified |

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions - Computational Tools for XRD Analysis

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| GSAS-II | Software suite | Rietveld refinement, PDF analysis, sequential fitting [17] | Open source |

| powerxrd | Python library | Basic Rietveld refinement for cubic systems [12] | Open source |

| SIMPOD | Benchmark dataset | 467,861 crystal structures with simulated XRD patterns [16] | Public dataset |

| PXRDGen | Neural network | End-to-end crystal structure determination [13] | Research code |

| DiffractGPT | Transformer model | Structure prediction from XRD patterns [14] | Research code |

| TOPAS | Refinement software | Whole powder pattern modeling, Rietveld refinement [11] | Commercial |

Workflow Visualization

Workflow Comparison for XRD Analysis - This diagram illustrates the fundamental differences between traditional, ML-based, and hybrid approaches to crystal structure determination from XRD data, highlighting the reduced complexity and manual intervention in ML-powered workflows.

PXRDGen Neural Network Architecture - This diagram details the architecture of PXRDGen, an end-to-end neural network that integrates diffraction pattern encoding with generative structure determination, achieving atomic-level accuracy in seconds.

Implementation in Pharmaceutical Development

The methodological shift from Rietveld to neural networks has particularly significant implications for pharmaceutical development, where polymorph identification and crystallinity assessment are critical for drug efficacy, stability, and intellectual property protection. Traditional XRD analysis in pharmaceutical contexts faces challenges in throughput and expertise requirements, creating bottlenecks in formulation development and quality control [2]. ML-powered approaches enable rapid screening of polymorphic forms and quantitative phase analysis with minimal expert intervention, accelerating the drug development pipeline.

For pharmaceutical applications, specialized protocols have been developed that leverage the strengths of both traditional and ML methods:

Pharmaceutical Polymorph Screening Protocol:

High-Throughput Data Acquisition

- Utilize automated sample changers for rapid data collection from multiple formulations

- Implement standardized measurement parameters (Cu Kα, 5-40° 2θ range for initial screening)

- Apply robotic systems for sample preparation and loading

ML-Assisted Phase Identification

- Use pre-trained models (B-VGGNet or similar) for rapid classification of polymorphs

- Apply Bayesian uncertainty quantification to flag ambiguous patterns for expert review [15]

- Leverate ensemble methods combining multiple architectures for improved robustness

Quantitative Phase Analysis

- Employ ML models trained on synthetic mixtures for initial concentration estimates

- Refine quantitative results using traditional Rietveld methods with ML-generated starting models

- Validate against known standards and orthogonal characterization methods

Regulatory Compliance and Documentation

- Maintain detailed audit trails of ML model versions and training data

- Document validation procedures and uncertainty estimates

- Generate comprehensive reports suitable for regulatory submissions

The implementation of ML methods in pharmaceutical XRD analysis addresses key industry needs for speed, reproducibility, and reduced operator dependency. However, regulatory considerations necessitate careful validation and documentation of ML-based methods, with particular emphasis on model interpretability and uncertainty quantification [15]. Techniques such as SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) analysis help elucidate the basis for ML predictions, identifying which features of the XRD pattern drive specific classifications and thereby building trust in the automated system [15].

Future Perspectives & Concluding Remarks

The ongoing shift from Rietveld refinement to neural network-based analysis represents more than just a technological upgrade—it constitutes a fundamental transformation in how crystalline materials are characterized and understood. Current research trends suggest several key directions for future development:

Integration with Multi-Modal Data Sources: Future systems will likely incorporate complementary characterization data (PDF analysis, spectroscopy, microscopy) alongside XRD patterns, enabling more robust structure determination and overcoming limitations of individual techniques [2] [17]. This multi-modal approach will be particularly valuable for complex pharmaceutical formulations where multiple polymorphs, amorphous content, and impurities coexist.

Real-Time Analysis and Closed-Loop Discovery: The speed of ML-based XRD analysis enables real-time feedback during materials synthesis and processing [2]. This capability supports closed-loop discovery systems where XRD characterization directly informs synthesis parameter adjustments, dramatically accelerating the development of novel materials with tailored properties.

Enhanced Interpretability and Physical Consistency: Future ML architectures will increasingly incorporate physical constraints and domain knowledge directly into model structures, ensuring that predictions adhere to fundamental crystallographic principles [15] [2]. Techniques that provide explicit uncertainty estimates and explanatory rationales will be essential for regulatory acceptance and scientific trust.

Democratization of Crystallographic Analysis: As ML tools become more accessible and user-friendly, advanced materials characterization capabilities will become available to non-specialists, potentially transforming materials discovery across diverse scientific and industrial contexts [14] [11].

The methodological evolution from Rietveld to neural networks represents a paradigm shift that addresses longstanding challenges in XRD analysis while opening new possibilities for accelerated materials discovery and characterization. By combining the physical grounding of traditional approaches with the speed and automation of modern ML, the field is poised to make significant contributions to pharmaceutical development, functional materials design, and fundamental materials science.

In pharmaceutical development, the crystalline structure of an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) is a critical quality attribute that directly influences the drug's solubility, bioavailability, stability, and efficacy [18] [19]. Polymorphism, the ability of a solid to exist in more than one crystal form, presents both a challenge and an opportunity for drug manufacturers. The unexpected appearance of a new, more stable polymorph can alter the product's performance, leading to significant regulatory and safety concerns, as historically witnessed with drugs like ritonavir [20]. X-ray Diffraction (XRD) has emerged as a premier technique for identifying and characterizing these polymorphic forms. This application note details how XRD, particularly when enhanced by modern machine learning (ML) analysis, provides robust protocols for polymorph screening and API characterization within a GMP-compliant framework, derisking the drug development process [9] [19].

The Role of XRD in Pharmaceutical Solid-State Analysis

XRD is a non-destructive analytical technique that provides detailed information about the crystal structure, phase composition, and crystallinity of a material. In the pharmaceutical industry, it is indispensable for:

- Polymorph Identification and Discrimination: Different polymorphs produce distinct XRD patterns, acting as a fingerprint for the solid form [18] [21].

- Crystallinity Assessment: The degree of crystallinity of an API, which impacts solubility and dissolution rate, can be quantified from XRD data [18] [22].

- Formulation Stability and Process Monitoring: XRD can detect and monitor solid-form transformations during manufacturing processes such as compression, granulation, or storage [18] [21].

- Regulatory Compliance: Health Canada, the FDA, and EMA require solid-state characterization data as part of new drug applications, for which XRD is a leading technique [18] [19].

The integration of machine learning with XRD analysis is transforming this field. ML models can automate phase identification, classify crystal symmetry, and predict crystal structures from XRD patterns, enabling higher-throughput analysis and uncovering subtle patterns that may be missed by conventional methods [15] [9] [20].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Polymorph Screening of an API Using a Benchtop XRD System

This protocol is designed for the comprehensive identification of polymorphic forms of a new chemical entity during early development.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Benchtop X-ray Diffractometer | Compact instrument (e.g., Malvern Panalytical Aeris) for routine laboratory analysis. |

| API Powder Sample | The active pharmaceutical ingredient to be screened, typically 100-500 mg. |

| Standard Sample Holder | A zero-background or low-background holder to minimize noise. |

| Crystallography Databases | Reference databases (e.g., CSD, COD) for pattern matching [16] [20]. |

Workflow Overview:

Methodology:

Sample Preparation:

- Gently grind the API powder to ensure a homogeneous particle size and minimize preferred orientation.

- Load the powder into the sample holder, taking care to create a flat, level surface.

Data Acquisition:

- Instrument: Benchtop XRD system (e.g., Malvern Panalytical Aeris).

- Parameters:

- X-ray Source: Cu Kα radiation (wavelength λ = 1.5406 Å).

- Voltage/Current: 40 kV, 15 mA.

- Scan Range (2θ): 5° to 40°.

- Step Size: 0.02°.

- Scan Speed: 0.5–2 seconds per step.

- Mount the sample holder and initiate the scan.

Data Analysis and Machine Learning Classification:

- Preprocessing: Perform background subtraction and smoothing on the raw diffraction pattern.

- Peak Identification: Automatically identify the position (2θ), intensity, and full width at half maximum (FWHM) of all significant peaks.

- ML-Enhanced Classification: Input the preprocessed pattern or derived features into a pre-trained machine learning model. For instance, a Bayesian-VGGNet model can be used to classify the crystal system or space group while also estimating prediction uncertainty, achieving up to 75% accuracy on experimental data [15]. This step helps automate the initial phase identification.

- Database Matching: Compare the processed XRD pattern against a database of known polymorphs (e.g., from the Cambridge Structural Database, CSD) to identify matches. The ML classification provides a shortlist of candidate structures to refine the search.

Reporting:

- Document the identified polymorphic form(s) and the confidence level of the ML classification.

- Report any unknown patterns that may indicate a novel polymorph.

Protocol 2: In-line XRD Monitoring of Compression-Induced Polymorphic Transitions

This protocol is designed for real-time monitoring of potential solid-state transformations during tablet compression, using a diamond anvil cell (DAC) to simulate tableting pressures [21].

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for In-line Monitoring

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Diamond Anvil Cell (DAC) | Device to apply high pressure to a micro-scale sample, simulating tableting. |

| In-line XRD/Raman System | Combined XRD and spectroscopic system for simultaneous structural and chemical analysis. |

| API Powder | The polymorphic form of the API to be tested. |

| Pressure Calibrant | A standard material (e.g., ruby) for determining pressure within the DAC. |

Workflow Overview:

Methodology:

Sample Loading and Setup:

- Load a micro-scale quantity (micrograms) of the API powder into the diamond anvil cell along with a minute piece of ruby for pressure calibration [21].

- Assemble the DAC and position it in the XRD instrument.

In-line Data Acquisition:

- Instrument: Synchrotron XRD source or laboratory instrument equipped with a DAC.

- Parameters:

- Wavelength: Synchrotron (e.g., λ = 0.485 Å) or Cu Kα (λ = 1.5406 Å).

- Detector: 2D area detector for rapid data collection.

- Begin data collection at ambient pressure to establish a baseline pattern.

Pressure Application and Real-time Analysis:

- Apply pressure to the DAC in incremental steps, covering the range of 0–5 GPa to simulate tableting pressures.

- At each pressure step, collect an XRD pattern with an acquisition time of 10–30 seconds.

- In real-time, use a convolutional neural network (CNN) trained on synthetic and experimental XRD patterns to classify the phase present at each pressure step. This model can identify the onset of a polymorphic transition by detecting changes in the pattern [9] [23].

Identification of Transition Point:

- The transition pressure is identified when the ML model's classification confidence shifts from the starting polymorph to a new form.

- Plot the phase abundance (as determined by the model) against applied pressure to visualize the transition.

Reporting:

- Report the critical pressure at which the polymorphic transition occurs.

- Identify the new polymorphic form that is generated under pressure.

Computational Validation and Machine Learning Integration

The robustness of XRD-based polymorph screening is greatly enhanced by computational crystal structure prediction (CSP) and dedicated ML models for XRD analysis.

Crystal Structure Prediction (CSP): A state-of-the-art CSP method combines systematic crystal packing search with a hierarchical energy ranking using machine learning force fields (MLFF) and periodic Density Functional Theory (DFT) [20]. This approach was validated on a large set of 66 molecules with 137 known polymorphs. The method successfully reproduced all experimentally known polymorphs, with the known structure ranked among the top 2 candidates for 26 out of 33 single-form molecules [20]. This demonstrates CSP's power to anticipate and derisk the appearance of new polymorphs.

Machine Learning for XRD Pattern Analysis: ML models are specifically trained to interpret XRD patterns.

- Model Architecture: A Bayesian-VGGNet model can be employed for crystal symmetry classification, achieving 84% accuracy on simulated spectra and 75% on external experimental data [15]. The Bayesian framework provides uncertainty estimates for each prediction, which is crucial for assessing reliability.

- Training Data: Models are trained on large, diverse datasets of simulated and experimental patterns. The SIMPOD database, for example, offers 467,861 simulated powder X-ray diffractograms from the Crystallography Open Database, facilitating the training of generalizable models [16]. Techniques like Template Element Replacement (TER) can further generate virtual structures to expand the chemical space for training, improving model accuracy and interpretability [15].

Table 3: Performance Metrics of ML Models in XRD Analysis

| Model/Task | Dataset | Key Performance Metric | Relevance to Pharma |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bayesian-VGGNet (Space Group Classification) [15] | SYN (Synthetic + Real Data) | 84% Accuracy (Simulated), 75% Accuracy (Experimental) | High-confidence automated phase identification |

| Computer Vision Models (Space Group Prediction) [16] | SIMPOD (467,861 patterns) | Top-5 Accuracy >90% (e.g., Swin Transformer V2) | Rapid screening of unknown phases |

| Crystal Structure Prediction (Polymorph Reproduction) [20] | 66 Molecules, 137 Polymorphs | Known polymorph ranked in top 2 for 79% of molecules | De-risks late-appearing polymorphs |

X-ray diffraction remains a cornerstone of solid-state characterization in biomedicine. Its value is exponentially increased when integrated with machine learning for automated, high-confidence analysis and with computational crystal structure prediction for proactive risk assessment.

For researchers implementing these protocols:

- For Routine QC Labs: Begin with robust benchtop XRD systems and implement pre-trained ML models for initial phase identification to standardize and accelerate analysis [18].

- For R&D and Pre-clinical Development: Integrate computational CSP studies early in the development lifecycle to identify potential polymorphic risks and guide experimental screening efforts [20].

- For Process Development: Employ in-line XRD monitoring, supported by real-time ML classification, to map the stability of the API polymorph under various processing conditions, ensuring consistent product quality [21].

This combined experimental and computational approach, centered on advanced XRD analysis, provides a powerful framework for ensuring the development of safe, effective, and stable pharmaceutical products.

ML in Action: Algorithms and Real-World Applications for In-Line Analysis

The transition from traditional, manual analysis of X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns to automated, intelligent systems represents a paradigm shift in materials characterization. This evolution spans a spectrum of machine learning approaches, from relatively simple shallow neural networks to sophisticated deep convolutional architectures, each offering distinct advantages for specific analytical challenges. The selection of an appropriate model architecture is paramount, as it directly influences analytical performance in terms of accuracy, computational efficiency, and generalizability to diverse material systems [2].

Traditional XRD analysis methods, including Rietveld refinement, often require significant expert intervention, manual parameter initialization, and are computationally intensive for large datasets [8] [24]. Machine learning approaches circumvent these limitations by learning directly from the diffraction patterns, enabling high-throughput analysis essential for modern materials discovery and pharmaceutical development [8] [18]. This document provides a structured framework for selecting, implementing, and validating machine learning models for XRD pattern analysis, with particular emphasis on the nuanced trade-offs between model complexity and performance.

Model Architectures in Practice

The landscape of models applied to XRD analysis is diverse, ranging from shallow networks to advanced transformers. The table below summarizes the key architectures, their characteristics, and demonstrated applications.

Table 1: Machine Learning Models for XRD Data Analysis

| Model Architecture | Typical Complexity & Depth | Key Characteristics | Reported XRD Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shallow Neural Network (SNN) | Low (1-3 hidden layers) | Fast training, lower computational demand, prone to underfitting complex patterns | Medical phantom classification [25], initial phase analysis |

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | Medium to High (10+ layers) | Automatic feature extraction from raw patterns, translation invariance, handles 1D/2D data | Crystal system & space group classification [8] [26], phase identification [24] |

| Dense Convolutional Network (DenseNet) | High (Dense layer connectivity) | Improved gradient flow, feature reuse, parameter efficiency | Grain orientation mapping from STEM diffraction [27] [28] |

| Swin Transformer | Very High (Attention mechanisms) | Captures long-range dependencies, highest accuracy on complex tasks, computationally intensive | State-of-the-art in orientation mapping and microstructure analysis [27] [28] |

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Empirical evaluations across numerous studies provide clear evidence of a performance-complexity trade-off. While simpler models offer computational efficiency, advanced architectures consistently achieve superior accuracy on challenging classification and quantification tasks.

Table 2: Reported Model Performance on Various XRD Tasks

| Task Description | Best Performing Model | Reported Performance Metric | Comparative Models & Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crystal System Classification | CNN [26] | 94.99% Accuracy [26] | Baseline models shown to be less accurate [8] |

| Space Group Classification | CNN [26] | 81.14% Accuracy [26] | Traditional rule-based methods require more human intervention [26] |

| Medical Phantom Classification | Shallow Neural Network [25] | 98.94% Accuracy, 0.999 AUC [25] | Outperformed SVM (97.36%), Rules-based (96.48%) [25] |

| Phase Quantification (4-phase system) | CNN (with custom loss) [24] | 0.5% error (synthetic), 6% error (experimental) [24] | Superior to traditional methods with manual phase ID [24] |

| Grain Orientation Mapping | Swin Transformer [27] [28] | Highest evaluation scores & intra-grain consistency [27] | Outperformed DenseNet and baseline CNN [27] [28] |

Experimental Protocol: A Step-by-Step Guide to Model Implementation

End-to-End Workflow for ML-Based XRD Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow, from data preparation to model deployment, for implementing a machine learning solution for XRD analysis.

Phase 1: Data Preparation and Preprocessing

Data Acquisition and Synthesis

- Experimental Data Collection: Utilize standard XRD instrumentation (e.g., Bruker D8 Advance, Malvern Panalytical Aeris) with consistent parameters (Cu Kα radiation, λ = 1.5406 Å, 2θ range of 5–90°) [16] [24]. For medical applications, specialized systems like fan-beam coded aperture imaging may be employed [25].

- Synthetic Data Generation: Generate large-scale training datasets from crystallographic information files (CIF) using simulation packages (e.g., Dans Diffraction) [16] [24]. Incorporate realistic variations including:

- Peak broadening via Caglioti parameters

- Statistical noise (Poisson, Gaussian)

- Varying crystallite size and microstrain

- Instrumental parameter variations [8]

Critical Preprocessing Steps

- Intensity Scaling: Apply sample-wise min-max scaling (normalization) to preserve relative intensity trends, which are crucial for phase identification [29].

- Data Representation: Convert 1D diffractograms to 2D radial images to leverage computer vision architectures, as demonstrated to improve performance in space group prediction [16].

- Data Augmentation: Introduce synthetic variations in peak position (via lattice parameter changes), intensity, and background to enhance model robustness [8].

- Dataset Partitioning: Implement structured splitting (e.g., 60/20/20 for training/validation/testing) ensuring no data leakage between splits. For generalizability testing, hold out entire material systems or experimental batches [8].

Phase 2: Model Selection and Training Protocol

Architecture-Specific Configurations

Shallow Neural Networks:

- Architecture: 1-3 fully connected hidden layers (128-512 neurons per layer)

- Input: Feature-engineered XRD data (e.g., peak positions, intensities) or flattened pattern

- Use Case: Baseline models or when training data is extremely limited [25]

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs):

- Architecture: Multiple convolutional layers with increasing filters (64→128→256) followed by fully connected layers

- Input: Raw 1D diffractogram or 2D radial image [16]

- Critical Layers: Convolutional layers (feature extraction), pooling layers (translation invariance), dropout (regularization) [26]

- Use Case: Standard choice for most classification tasks, offering balance of performance and efficiency [8]

Advanced Architectures (DenseNet, Swin Transformer):

- DenseNet: Dense connectivity pattern enabling feature reuse; optimal for gradient flow in very deep networks [27]

- Swin Transformer: Self-attention mechanisms capturing long-range dependencies in patterns; achieves state-of-the-art performance [27] [28]

- Use Case: Complex tasks requiring highest accuracy (e.g., orientation mapping, fine-grained space group discrimination) [27]

Training Procedures and Hyperparameters

Loss Function Selection:

- Classification: Categorical cross-entropy

- Quantification: Mean Squared Error or specialized loss functions (e.g., Dirichlet-based for proportion inference) [24]

- Regression: Mean Absolute Error for continuous outputs (e.g., lattice parameters)

Optimization Configuration:

- Optimizer: Adam or SGD with momentum

- Learning Rate: 1e-3 to 1e-5 (employ learning rate scheduling)

- Batch Size: 32-128 (dependent on available memory)

- Regularization: L2 weight decay, dropout, early stopping

Hyperparameter Optimization: Systematic search over key parameters including learning rate, network depth, filter sizes, and dropout rates [27]

Phase 3: Validation and Interpretation

Robust Validation Strategies

- Cross-Validation: Implement k-fold cross-validation (typically k=5) to assess model stability [16]

- Generalizability Testing: Evaluate on dedicated datasets representing:

- Statistical Metrics:

- Classification: Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score, Confusion Matrix

- Quantification: Mean Absolute Error, R² coefficient

- Overall: Area Under ROC Curve (AUC) [25]

Model Interpretation and Explainability

- Attention Visualization: For transformer architectures, visualize attention maps to identify which pattern regions influence decisions [27]

- Saliency Maps: For CNNs, generate gradient-based saliency maps highlighting influential regions in input patterns [8]

- Physical Consistency: Verify predictions align with crystallographic principles (e.g., Bragg's law, systematic absences) [8]

Table 3: Key Resources for ML-Driven XRD Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Database | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Public Databases | Crystallography Open Database (COD) [16] | Source of crystal structures for synthetic training data generation |

| Materials Project [8] | Repository of inorganic crystal structures and computed properties | |

| RRUFF Project [8] | Collection of experimentally verified mineral XRD data for validation | |

| Software & Libraries | Dans Diffraction [16] | Python package for simulating XRD patterns from CIF files |

| Profex/BGMN [24] | Rietveld refinement software for generating ground-truth labels | |

| PyTorch/TensorFlow [16] | Deep learning frameworks for model development and training | |

| H2O AutoML [16] | Automated machine learning for traditional model development | |

| Computational Resources | SIMPOD Dataset [16] | Pre-computed database of simulated powder XRD patterns |

| GPU Acceleration | Essential for training deep learning models in reasonable time |

The selection of an appropriate machine learning model for XRD analysis requires careful consideration of multiple factors, including dataset size, analytical task complexity, available computational resources, and performance requirements. Shallow neural networks provide a computationally efficient baseline for simple classification tasks, while convolutional neural networks offer robust performance for most standard applications including phase identification and crystal system classification. For the most challenging problems requiring the highest accuracy, such as fine-grained space group classification or orientation mapping, advanced architectures like DenseNets and Swin Transformers represent the current state-of-the-art, albeit with increased computational demands [27] [8] [28].

The field continues to evolve rapidly, with future directions pointing toward increased integration of physical constraints into model architectures, improved handling of experimental artifacts, and enhanced generalizability across diverse material systems. By following the protocols and guidelines outlined in this document, researchers can systematically implement machine learning solutions that accelerate materials characterization and drive innovation in pharmaceutical development and materials design.

Automated Phase Identification and Crystal System Classification

The accelerating demand for novel materials in technology and pharmaceutical development necessitates a paradigm shift from traditional, labor-intensive X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis toward intelligent, automated systems. Traditional XRD analysis requires significant expert interpretation for phase identification and crystal system classification, creating a critical bottleneck in high-throughput materials discovery pipelines [10] [2]. The integration of machine learning (ML) is transforming this landscape, enabling automated, rapid, and accurate extraction of structural information from XRD patterns [2].

This evolution is crucial for establishing robust composition-structure-property relationships, a foundational goal in materials science and drug development [10]. Automated phase mapping and classification systems are particularly vital for analyzing combinatorial libraries containing hundreds to thousands of compositionally varying samples, where manual analysis is impractical [10]. This document outlines cutting-edge computational frameworks and provides detailed protocols for implementing automated XRD analysis, contextualized within a broader thesis on in-line machine learning for materials research.

Current Methodologies in Automated XRD Analysis

Recent advances have produced diverse computational strategies for XRD analysis, ranging from unsupervised optimization to supervised deep learning. The table below summarizes the core functionalities and applications of prominent methodologies.

Table 1: Machine Learning Methodologies for Automated XRD Analysis

| Method Name | Type | Core Functionality | Reported Performance/Accuracy | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AutoMapper [10] | Unsupervised Optimization-Based Solver | Automated phase mapping integrating domain knowledge (thermodynamics, crystallography) | Robust performance across multiple experimental datasets (V–Nb–Mn oxide, Bi–Cu–V oxide, Li–Sr–Al oxide) | High-throughput phase mapping of combinatorial libraries |

| B-VGGNet with TER [15] | Supervised Deep Learning (Bayesian CNN) | Crystal structure & space group classification with uncertainty quantification | 84% accuracy on simulated spectra; 75% accuracy on external experimental data | Autonomous phase identification, confidence evaluation |

| PQ-Net [30] | Supervised Deep Learning (CNN) | Real-time quantification of phase parameters (fraction, lattice parameters) | Error 70% lower than Rietveld; computation speed >1000x faster | Quantitative phase analysis, microstructural characterization |

| XCA [10] | Supervised Ensemble Model | Probabilistic classification of present phases | Provides probability scores for phase presence | Phase identification in complex multi-phase samples |

| Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF) [10] | Unsupervised Matrix Factorization | Pattern demixing to identify constituent phases | Requires prior determination of the number of phases | Phase mapping, identifying lattice parameter changes |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows