Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production from Water Splitting: Mechanisms, Materials, and Scalability for a Sustainable Energy Future

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of photocatalytic hydrogen production, a promising technology for converting solar energy into storable chemical fuel.

Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production from Water Splitting: Mechanisms, Materials, and Scalability for a Sustainable Energy Future

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of photocatalytic hydrogen production, a promising technology for converting solar energy into storable chemical fuel. Tailored for researchers and scientists, it explores the fundamental principles of water splitting, evaluates advanced photocatalytic materials from classical semiconductors to emerging metal-organic frameworks and high-entropy materials, and details innovative system designs that enhance efficiency and stability. Furthermore, it critically assesses performance metrics, scalability challenges, and the techno-economic potential essential for translating laboratory breakthroughs into viable industrial applications, thereby bridging fundamental research and practical implementation.

Understanding the Fundamentals: The Science Behind Photocatalytic Water Splitting

Photocatalytic water splitting presents a promising pathway for sustainable hydrogen production by converting solar energy into chemical fuel. This process mimics natural photosynthesis, using a light-absorbing semiconductor to drive the reduction and oxidation of water. The fundamental challenge lies in efficiently managing the photogenerated charge carriers to maximize the hydrogen evolution reaction while minimizing recombination losses. Recent advancements in material design and reaction engineering have significantly improved the efficiency and practicality of these systems, bringing them closer to commercial viability [1] [2]. This document outlines the core principles, experimental methodologies, and performance evaluation criteria essential for research in photocatalytic hydrogen production within the context of water splitting applications.

Fundamental Principles

The photocatalytic process begins when a semiconductor material absorbs photons with energy equal to or greater than its bandgap, promoting electrons from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB). This generates electron-hole (eâ»/hâº) pairs that drive the redox reactions necessary for water splitting. The excited electrons possess strong reducing capabilities, while the holes exhibit potent oxidizing properties [1] [3].

Efficient water splitting requires careful design of the photocatalyst to ensure three critical conditions: sufficient light absorption, effective charge separation, and surface reaction activity. The thermodynamic potential for water splitting is 1.23 eV, though practical photocatalysts require broader bandgaps to provide overpotential for the reactions [4]. The hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) occurs when electrons reduce protons (Hâº) to form hydrogen gas (Hâ‚‚), while the oxygen evolution reaction (OER) involves holes oxidizing water molecules to release oxygen [4].

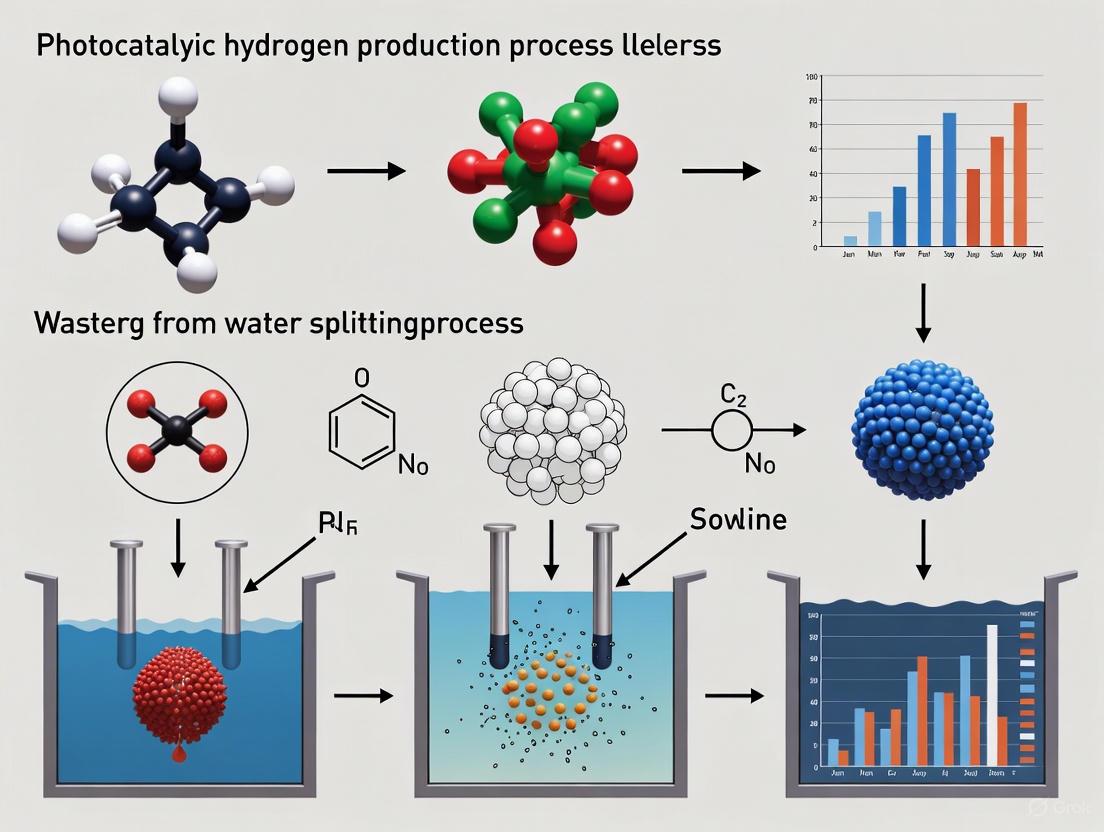

Figure 1: Fundamental processes in semiconductor photocatalysis, illustrating light absorption, charge separation, redox reactions, and recombination loss pathways.

Experimental Protocols

Synthesis of Al-Doped SrTiO₃ with Flux Treatment (RCSTOA Photocatalyst)

This protocol describes the preparation of Rh@Cr₂O₃/SrTiO₃:Al (RCSTOA) photocatalyst with controlled anisotropic facets through flux treatment, adapted from recent research demonstrating enhanced photocatalytic performance [5].

Materials and Equipment

- Precursors: Strontium carbonate (SrCO₃), titanium dioxide P25 (TiO₂), aluminum oxide (Al₂O₃)

- Flux agents: SrClâ‚‚, KCl, or NaCl (analytical grade)

- Co-catalyst precursors: Rhodium chloride (RhCl₃), chromium nitrate (Cr(NO₃)₃)

- Equipment: High-temperature muffle furnace, alumina crucibles, ball mill, ultrasonic bath, photodeposition system with light source

Step-by-Step Procedure

Precursor Preparation: Weigh stoichiometric amounts of SrCO₃, TiO₂ (P25), and Al₂O₃ to achieve 2 wt% Al doping in the final SrTiO₃ structure.

Flux Treatment:

- Mix the precursors thoroughly with selected flux agent (SrClâ‚‚, KCl, or NaCl) in a 1:10 mass ratio (precursor:flux).

- Transfer the mixture to an alumina crucible and heat in a muffle furnace at 1100°C for 4 hours with a heating rate of 5°C/min.

- Allow natural cooling to room temperature.

Purification:

- Wash the resulting product repeatedly with deionized water and ethanol to remove residual flux compounds.

- Dry the purified powder at 80°C for 12 hours.

Co-catalyst Deposition:

- Prepare aqueous solutions of RhCl₃ and Cr(NO₃)₃ to achieve 0.05-0.2 wt% metal loading.

- Use photodeposition or wet-impregnation method to load Rh onto the SrTiO₃:Al surface.

- Subsequently, deposit Cr₂O₃ through photodeposition under UV irradiation for 2 hours.

- Recover the final RCSTOA photocatalyst by centrifugation and dry at 80°C for characterization and testing.

Characterization and Validation

- XRD Analysis: Confirm cubic SrTiO₃ phase (JCPDS card no. 35-0734) with distinct diffraction peaks at 2θ = 22.77°, 32.36°, 39.94°, 46.50°, 52.32°, 57.78°, and 67.77°.

- SEM/TEM: Verify anisotropic facet exposure including (100), (110), and (111) high-index facets.

- UV-Vis Spectroscopy: Assess light absorption properties and band gap estimation.

Photocatalytic Water Splitting Performance Evaluation

This protocol standardizes the assessment of hydrogen production activity from overall water splitting under simulated solar illumination [5] [6].

Reaction Setup

- Reactor System: Use a gas-closed circulation system with a top-window Pyreactor.

- Light Source: 300 W Xenon lamp with AM 1.5G filter to simulate solar illumination.

- Catalyst Loading: 0.1 g photocatalyst dispersed in 100 mL water source (deionized water, artificial seawater, or tap water).

- Reaction Conditions: Maintain temperature at 25°C with continuous magnetic stirring.

Gas Analysis and Quantification

- Sampling: Extract 0.4 mL of gas from the reactor headspace at regular intervals (typically hourly).

- Chromatographic Analysis: Use gas chromatography (GC) with thermal conductivity detector (TCD) and molecular sieve columns.

- Quantification: Determine hydrogen concentration using calibration curves from standard gases.

- Control Experiments: Perform blank tests without catalyst or without light to confirm photocatalytic origin of hydrogen production.

Quantum Efficiency Calculations

Accurate determination of quantum efficiency is essential for comparing photocatalyst performance across different studies [7] [6].

Apparent Quantum Yield (AQY) Measurement

- Light Source: Monochromatic light (e.g., 380 nm) using appropriate bandpass filters.

- Calculation Formula:

- Photon Flux Determination: Use calibrated silicon photodiode or optical power meter to measure incident light intensity.

Solar-to-Hydrogen (STH) Efficiency Measurement

- Light Source: Standard AM 1.5G solar simulator (100 mW/cm²).

- Calculation Formula:

Where:

- rHâ‚‚: Hâ‚‚ production rate (μmol sâ»Â¹)

- ΔG°: Gibbs free energy change for water splitting (237 kJ/mol)

- Plight: Incident light power density (mW cmâ»Â²)

- S: Irradiated area (cm²)

Performance Data and Efficiency Metrics

Table 1: Performance comparison of representative photocatalyst systems for hydrogen production from water splitting

| Photocatalyst | Light Source | Hâ‚‚ Production Rate | AQY/STH | Reference/System |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rh@Crâ‚‚O₃/SrTiO₃:Al (SrClâ‚‚ flux) | Simulated sunlight | 351 μmol gâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹ (Hâ‚‚) | AQY = 19% @380 nm | [5] |

| 18-facet SrTiO₃ with Pt/Co₃Oâ‚„ | 365 nm | 30 μmol hâ»Â¹ (Hâ‚‚) | AQY = 0.81% | [5] |

| CdS/CoFeâ‚‚Oâ‚„ on AMS | Simulated sunlight | 254.1 μmol hâ»Â¹ | Not specified | [4] |

| Ag@C/SrTiO₃ | Simulated sunlight | 457.5 μmol gâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹ | Not specified | [8] |

| GaInN | Concentrated light | Not specified | STH = 9.2% | [8] |

Table 2: Key efficiency parameters in photocatalytic water splitting research [7]

| Parameter | Acronym | Definition | Calculation Formula |

|---|---|---|---|

| External Quantum Efficiency | EQE/IPCE | Ratio of electrons generated to incident photons | IPCE = (jph × h × c) / (e × Pmono × λ) × 100% |

| Internal Quantum Efficiency | IQE/APCE | Ratio of electrons generated to absorbed photons | APCE = IPCE / A |

| Applied Bias Photo-to-Current Efficiency | ABPE | Energy conversion efficiency deducting electrical contribution | ABPE = [jph × (Vredox - Vapp) × ηF] / Plight |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key research reagents and materials for photocatalytic hydrogen production experiments

| Material/Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SrTiO₃ (Strontium Titanate) | Primary photocatalyst | Perovskite structure with suitable band positions for overall water splitting [5] |

| TiOâ‚‚ (Titanium Dioxide) | Benchmark photocatalyst | UV-responsive, requires modification for visible light activity [1] [2] |

| ZnO (Zinc Oxide) | Alternative semiconductor | Wide bandgap (3.37 eV), primarily UV-active, easily modifiable through doping [3] |

| Co-catalysts (Pt, Rh, NiS, MoSâ‚‚) | Enhance surface reactions | Lower activation energy for hydrogen evolution reaction [5] [2] |

| Sacrificial Agents (Methanol, Na₂S/Na₂SO₃) | Hole scavengers | Enhance H₂ production by consuming photogenerated holes [8] |

| Flux Agents (SrClâ‚‚, KCl, NaCl) | Crystal growth modifiers | Control facet exposure and morphology during synthesis [5] |

| Dopants (Al³âº, Cu²âº) | Bandgap engineering | Modify electronic structure to enhance visible light absorption [5] |

| 2-Fluorocyclohexa-1,3-diene | 2-Fluorocyclohexa-1,3-diene|CAS 24210-87-5 | 2-Fluorocyclohexa-1,3-diene (C6H7F) is a fluorinated diene for research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Butyl octaneperoxoate | Butyl Octaneperoxoate|Research Grade|[Your Company] |

Advanced System Configurations

Recent innovations in photocatalytic system design have addressed fundamental limitations in traditional approaches. The development of immobilized photothermal-photocatalytic integrated systems represents a significant advancement, transforming the conventional solid-liquid-gas triphase system into a more efficient gas-solid biphasic configuration [4].

Figure 2: Evolution from conventional triphase to advanced biphasic photocatalytic systems, highlighting key limitations and advantages.

This innovative system configuration combines a photothermal substrate with high-performance photocatalysts, enabling a synergistic process of liquid water evaporation and steam-phase water splitting under light illumination without requiring additional energy input. The optimized system demonstrates remarkable hydrogen evolution rates (254.1 μmol hâ»Â¹), representing a significant leap forward compared to traditional triphase systems [4].

The photocatalytic process for hydrogen production continues to evolve from fundamental material discovery to integrated system engineering. The protocols and data presented herein provide a standardized framework for evaluating photocatalyst performance under conditions relevant to practical applications. As the field advances, focus must shift from laboratory metrics to system-level considerations including long-term stability, cost-effectiveness, and integration with existing energy infrastructure. The development of standardized testing protocols and efficiency accreditation will be crucial for meaningful comparison of photocatalyst performance and accelerating the transition to a renewable energy economy [6]. Future research directions should emphasize atomic-level catalyst design, machine-learning-accelerated discovery, and circular design principles to enhance sustainability and scalability [2].

Photocatalytic water splitting, a process that converts solar energy into chemical energy stored in hydrogen, is widely regarded as a promising pathway for sustainable energy production [9] [10]. Inspired by natural photosynthesis, this "artificial photosynthesis" approach uses semiconductor materials to capture light energy and catalyze water dissociation into hydrogen and oxygen [9]. Since the pioneering 1972 demonstration by Fujishima and Honda using TiOâ‚‚ electrodes, research has expanded significantly toward developing efficient particulate photocatalyst systems where powder materials dispersed in water enable direct solar-to-hydrogen conversion [9] [10].

The fundamental process relies on semiconductor photochemistry, where photon absorption creates electron-hole pairs that drive the hydrogen and oxygen evolution reactions [9]. Despite decades of research, the technology faces significant challenges in efficiency, stability, and cost-effectiveness [10]. This application note examines the core principles of semiconductor photochemistry—band gaps, charge carrier dynamics, and recombination pathways—within the context of photocatalytic hydrogen production, providing experimental protocols and analytical approaches for researchers in renewable energy and materials science.

Fundamental Principles

Semiconductor Band Structure and Energetic Requirements

The electronic band structure of a semiconductor comprises a filled valence band (VB), an empty conduction band (CB), and a forbidden energy region between them known as the band gap (E₉) [11]. When a photon with energy equal to or greater than the band gap strikes the semiconductor, it promotes an electron from the VB to the CB, creating an electron-hole pair [12].

For thermodynamically feasible water splitting, the semiconductor's band structure must satisfy specific energetic requirements [10]:

- The CB minimum must be more negative than the hydrogen evolution potential (0 V vs. NHE at pH 0, -0.41 V vs. NHE at pH 7)

- The VB maximum must be more positive than the oxygen evolution potential (1.23 V vs. NHE at pH 0, 0.82 V vs. NHE at pH 7)

- The minimum band gap required is 1.23 eV, though practical materials typically require 1.8-2.2 eV due to overpotentials [10]

Table 1: Band Positions and Band Gaps of Common Photocatalytic Materials

| Material | CB Edge (V vs. NHE) | VB Edge (V vs. NHE) | Band Gap (eV) | Light Absorption Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiOâ‚‚ (Anatase) | -0.3 | 2.9 | 3.2 | UV only |

| ZnO | -0.3 | 2.9 | 3.2 | UV only |

| CdS | -0.5 | 1.9 | 2.4 | Visible |

| BiVOâ‚„ | 0.1 | 2.5 | 2.4 | Visible |

| N-Doped TiOâ‚‚ | -0.3 | 2.5 | 2.8 | UV-Visible |

| Sc-Doped TiOâ‚‚ | -0.3 | ~2.7 | ~3.0 | Enhanced UV [13] |

Water splitting is an energetically uphill reaction with a standard Gibbs free energy change (ΔG°) of 237 kJ/mol (corresponding to 1.23 eV) [9]. The overall efficiency of solar-to-hydrogen conversion is determined by three sequential processes: (1) light absorption efficiency, (2) charge separation and migration efficiency, and (3) surface reaction efficiency [9].

Charge Carrier Dynamics and Recombination Pathways

Upon photoexcitation, the generated charge carriers undergo several competing processes [12]:

- Migration to the semiconductor surface

- Trapping at defect sites

- Recombination either in the bulk or at the surface

Charge recombination represents the principal efficiency loss mechanism in photocatalysis. Most photoinduced electrons and holes recombine within nanoseconds, dissipating energy as heat or photons [14]. As described in recent studies, recombination occurs through several pathways:

- Radiative recombination: Electron directly recombines with a hole, emitting a photon

- Defect-mediated recombination: Occurs through trap states within the band gap, often associated with vacancies or impurities [11]

- Auger recombination: Energy transferred to a third charge carrier

The presence of defects, particularly oxygen vacancies in metal oxides, significantly accelerates recombination by acting as electron traps that inhibit charge migration to active sites [14]. Recent research on TiOâ‚‚ has demonstrated that strategic doping can address these limitations by neutralizing oxygen vacancies and creating more directed charge transport pathways [13] [14].

Diagram 1: Charge Carrier Pathways in Photocatalytic Water Splitting. The diagram illustrates competing processes of charge migration to catalytic sites versus recombination pathways that reduce efficiency.

Band Gap Engineering Strategies

Extending the light absorption range of semiconductors while maintaining sufficient driving potential for water splitting represents a central challenge in photocatalyst design [12]. Various band gap engineering strategies have been developed to address this limitation.

Elemental Doping

Introducing foreign elements into the semiconductor lattice creates new energy states within the band gap, enabling visible light absorption [11] [12]. For TiOâ‚‚, nitrogen doping introduces N 2p states above the O 2p valence band maximum, reducing the effective band gap from 3.2 eV to approximately 2.8 eV [12]. Recent breakthrough research with scandium-doped TiOâ‚‚ demonstrates the multi-functional benefits of strategic doping: Sc ions effectively neutralize charge imbalances caused by oxygen vacancies, suppress electron trapping, and create directed pathways for charge transport, resulting in a 15-fold enhancement in hydrogen production efficiency [13] [14].

Defect Engineering

Controlled creation of specific defects can significantly alter electronic properties. Oxygen vacancies in TiO₂ create donor states below the conduction band, facilitating electron excitation with lower energy photons [11]. However, excessive vacancies act as recombination centers, highlighting the need for precise control [14]. In materials like SnWO₄, different vacancy types (Vₛₙ, VW, VO) introduce distinct defect states within the band gap, modifying both light absorption and charge separation characteristics [11].

Heterojunction Construction

Combining two or more semiconductors with aligned band structures enables enhanced charge separation through interfacial electron transfer [9] [11]. The S-scheme (step-scheme) heterojunction concept has emerged as particularly promising, where two semiconductors with staggered band structures form an interface that preserves the strongest redox potentials while facilitating recombination of less useful charge carriers [10]. In BiVOâ‚„/RGO heterostructures, the graphene component acts as an electron acceptor, reducing hole-electron recombination by approximately 60% and increasing photocurrent density by 3.8 times compared to pure BiVOâ‚„ [11].

Table 2: Band Gap Engineering Strategies and Their Effects

| Strategy | Mechanism | Advantages | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elemental Doping | Creates intragap states; Modifies band edges | Extends absorption range; Enhances conductivity | May introduce recombination centers; Thermal instability |

| Defect Engineering | Introduces vacancy/ interstitial states | Tailors optical absorption; Creates active sites | Difficult to control precisely; Can increase recombination |

| Heterojunction Construction | Enables interfacial charge transfer | Enhances charge separation; Combines complementary materials | Interface resistance; Lattice mismatch issues |

| Dye Sensitization | Injects electrons from sensitizer | Utilizes wide spectrum; Separates absorption/function | Sensitizer degradation; Poor interfacial binding |

| Morphology Control | Modifies quantum confinement; Increases surface area | Provides short migration paths; Multiple light reflection | Complex synthesis; Structural instability |

Advanced Characterization Techniques

Understanding charge carrier dynamics and recombination processes requires sophisticated time-resolved spectroscopic methods. Recent developments in characterization techniques provide unprecedented insight into photochemical processes.

Time-Resolved Spectroscopic Methods

The "bandgap energy excitation energy scanning - time-resolved mid-infrared photogenerated carrier detection spectrum" developed by researchers covers time ranges from femtoseconds to milliseconds, enabling systematic characterization of intermediate energy levels in photocatalytic semiconductors [15]. This approach has been applied to study defect states in TiOâ‚‚ polymorphs and the impact of boron doping on overall water splitting activity [15].

In ZnO and CdS microcrystals, femtosecond-scale measurements have revealed the formation of self-trapped polarons and hole polarons resulting from electron-phonon coupling [15]. These findings highlight the complex interplay between electronic excitations and lattice vibrations that influence charge carrier mobility and recombination.

Novel Light-Matter Interaction Theories

Recent research on layered semiconductors has revealed phenomena beyond traditional electric dipole approximation theory. When the phonon cavity mode displacement scale becomes comparable to the photon wavelength in layered materials, Raman-forbidden even-numbered interlayer breathing phonon modes become observable [16]. This phonon cavity and optical cavity coupling effect represents a significant advancement in understanding light-matter interactions in semiconductor materials [16].

Experimental Protocols

Synthesis of Scandium-Doped TiOâ‚‚ Photocatalyst

Principle: Incorporating Sc³⺠ions into the TiO₂ lattice to suppress oxygen vacancies and create directed charge transport pathways [13] [14].

Materials:

- Titanium precursor (titanium isopropoxide, titanium tetrachloride, or titanium butoxide)

- Scandium precursor (scandium chloride or scandium nitrate)

- Solvent (ethanol, isopropanol)

- pH modifiers (hydrochloric acid, ammonium hydroxide)

- Deionized water

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve titanium precursor (e.g., 10 mmol titanium isopropoxide) in 50 mL ethanol with stirring. In a separate container, dissolve scandium precursor (0.1-0.5 mol% relative to Ti) in 10 mL ethanol.

- Mixing: Slowly add the scandium solution to the titanium solution with vigorous stirring at room temperature.

- Hydrolysis: Add a controlled amount of deionized water (molar ratio Hâ‚‚O:Ti = 10:1) to initiate hydrolysis while maintaining continuous stirring.

- Aging: Allow the mixture to age for 12-24 hours at room temperature until a transparent sol forms.

- Gelation: Adjust pH to 3-4 using dilute HCl and heat to 40°C with stirring until gelation occurs.

- Drying: Dry the gel at 80°C for 12 hours to remove solvents.

- Calcination: Heat the dried powder in a muffle furnace with a programmed temperature ramp (2°C/min) to 450-500°C and maintain for 2-4 hours for crystallization.

Quality Control:

- Confirm Sc incorporation through ICP-OES analysis

- Verify crystallinity and phase purity by XRD (characteristic anatase peaks at 25.3°, 37.8°, 48.0°)

- Assess specific surface area by BET measurement (typically 80-120 m²/g)

Photocatalytic Water Splitting Performance Evaluation

Principle: Quantifying hydrogen production from water under simulated solar illumination to evaluate photocatalyst efficiency [9].

Materials:

- Photocatalyst powder (100-200 mg)

- Reaction cell with quartz window

- Water (deionized and degassed)

- Sacrificial reagents (if testing half-reactions: methanol for hole scavenging, AgNO₃ for electron scavenging)

- Light source (300W Xe lamp with AM 1.5 filter)

- Gas chromatograph (with TCD detector)

Procedure:

- Reactor Setup: Disperse photocatalyst powder in 100 mL deionized water in the reaction cell. For overall water splitting, use pure water; for hydrogen evolution half-reaction, add 10 vol% methanol as sacrificial agent.

- Degassing: Purge the system with argon for 30-60 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen.

- Illumination: Turn on the light source with intensity calibrated to 100 mW/cm² (1 sun).

- Gas Sampling: Periodically sample the headspace gas (typically every 30 minutes) using a gas-tight syringe.

- Analysis: Inject gas sample into GC equipped with molecular sieve column and TCD detector for Hâ‚‚ and Oâ‚‚ quantification.

- Control Experiments: Perform identical experiments in dark conditions and without catalyst to establish baseline.

Calculations:

- Hydrogen production rate: μmol/h

- Apparent quantum yield (AQY) at specific wavelength: AQY = (2 × number of evolved H₂ molecules / number of incident photons) × 100%

- Solar-to-hydrogen (STH) efficiency for overall water splitting: STH = (Energy output as H₂ / Energy of incident sunlight) × 100%

Diagram 2: Photocatalyst Evaluation Workflow. The experimental protocol for synthesizing and evaluating photocatalytic materials for water splitting, with typical timeframes for each step.

Time-Resolved Mid-Infrared Spectroscopy for Charge Carrier Analysis

Principle: Tracking photogenerated carrier dynamics across femtosecond to millisecond timescales to characterize recombination processes and trap states [15].

Materials:

- Photocatalyst sample (as pressed pellet or deposited as thin film)

- Tunable laser system (for bandgap excitation energy scanning)

- Mid-IR probe source

- Fast IR detector with time-correlated single photon counting capability

- Data acquisition system

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare uniform photocatalyst film on IR-transparent substrate (e.g., CaFâ‚‚ window).

- System Calibration: Align excitation and probe beams on sample with precise temporal overlap.

- Excitation Scanning: Sweep excitation energy across the material bandgap while monitoring mid-IR absorption.

- Time-Resolved Detection: Record transient IR absorption decays at characteristic frequencies with time resolution from femtoseconds to milliseconds.

- Data Analysis: Fit decay profiles to extract lifetime components and identify defect states.

Interpretation:

- Fast decays (ps-ns): Represent direct band-band recombination

- Intermediate decays (ns-μs): Indicate shallow trap-mediated recombination

- Slow decays (μs-ms): Correspond to detrapping and surface reaction processes

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Photocatalytic Water Splitting Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Examples & Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Semiconductor Precursors | Source of primary photocatalyst material | Titanium isopropoxide (TiOâ‚‚ precursor), Zinc acetate (ZnO precursor), Cadmium chloride (CdS precursor) |

| Dopant Sources | Modify band structure and electronic properties | Scandium chloride (for TiOâ‚‚ doping), Urea (nitrogen doping source), Boric acid (boron doping) |

| Sacrificial Reagents | Study half-reaction kinetics | Methanol (hole scavenger), Silver nitrate (electron scavenger), Triethanolamine (hole scavenger) |

| Co-catalysts | Enhance surface reaction kinetics | Chloroplatinic acid (Pt source for Hâ‚‚ evolution sites), Cobalt phosphate (Co-Pi for Oâ‚‚ evolution) |

| Structural Directing Agents | Control morphology and surface area | Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB), Pluronic triblock copolymers, Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) |

| Spectroscopic Probes | Characterize charge carrier dynamics | tert-Nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) for superoxide detection, Coumarin for hydroxyl radical detection |

| Reference Catalysts | Benchmark material performance | Degussa P25 TiO₂ (Evonik), Standard WO₃, Reference CdS samples |

Emerging Materials and Future Perspectives

Novel Semiconductor Platforms

Beyond traditional metal oxides, emerging materials show remarkable potential for photocatalytic water splitting:

Breathing Kagome Semiconductors: Two-dimensional breathing kagome structures like Ta₃SBr₇ exhibit unique electronic properties including nearly flat bands and Dirac cones, resulting in extraordinary exciton binding energies and valley-selective optical absorption [17]. These characteristics enable highly stable excitons with radiation lifetimes significantly longer than conventional 2D materials, suggesting promising applications in photocatalysis [17].

Layered Semiconductors: Materials such as WSâ‚‚ demonstrate phonon and optical cavity coupling effects that enable unusual electron-phonon interactions beyond traditional electric dipole approximations [16]. This new understanding of light-matter interactions provides fresh approaches for manipulating charge carrier dynamics in photocatalytic systems.

Efficiency Challenges and Research Directions

Despite significant progress, photocatalytic water splitting still faces efficiency challenges for practical implementation. Current best-performing systems typically achieve solar-to-hydrogen efficiencies of 1-2%, below the 6-10% threshold generally considered necessary for commercial viability [10].

Promising research directions include:

- Advanced heterojunction design with precisely controlled interfaces

- Multicomponent catalyst systems that separate light absorption, charge transport, and catalytic functions

- Nanostructure engineering to reduce charge carrier migration distances

- Dynamic spectroscopy to understand and mitigate recombination losses

- Theory-guided materials discovery combining machine learning with high-throughput screening

The integration of materials design, advanced characterization, and theoretical modeling provides a pathway toward overcoming current limitations in semiconductor photochemistry for sustainable hydrogen production.

Photocatalytic water splitting is a promising pathway for solar-to-chemical energy conversion, producing renewable hydrogen without carbon emissions. Within this field, two primary experimental pathways have been developed: direct overall water splitting (OWS) and sacrificial agent-assisted systems. Direct OWS accomplishes the complete decomposition of water into stoichiometric hydrogen and oxygen using only solar energy and a photocatalyst. In contrast, sacrificial agent systems incorporate chemical reagents that consume photogenerated holes, thereby enhancing hydrogen evolution kinetics while simplifying reaction requirements. This application note details the fundamental principles, experimental protocols, and key reagents for both pathways, providing researchers with practical guidance for implementing these systems.

Fundamental Principles and Comparative Analysis

Mechanism of Photocatalytic Water Splitting

The fundamental process of photocatalytic water splitting involves a semiconductor absorbing photons with energy equal to or greater than its bandgap, generating electron-hole pairs that drive redox reactions [4] [18]. The excited electrons reduce protons (Hâº) to hydrogen gas (Hâ‚‚), while the holes oxidize water molecules to oxygen gas (Oâ‚‚). Efficient water splitting requires the semiconductor's conduction band minimum to be more negative than the hydrogen evolution potential (Hâº/Hâ‚‚, 0 V vs. NHE at pH 0), and the valence band maximum to be more positive than the oxygen evolution potential (Hâ‚‚O/Oâ‚‚, +1.23 V vs. NHE) [19] [18]. A significant challenge is the rapid recombination of photogenerated electrons and holes, which occurs at rates orders of magnitude faster than the catalytic water splitting reactions, leading to substantial energy loss [19].

Table 1: Key Half-Reactions and Thermodynamic Requirements in Photocatalytic Water Splitting.

| Reaction | Equation | Potential (V vs. NHE, pH=0) |

|---|---|---|

| Photon Absorption | Semiconductor + â„ν → eâ»CB + hâºVB | Bandgap must be >1.23 eV |

| Water Oxidation (OER) | 2H₂O + 4h⺠→ O₂ + 4H⺠| +1.23 |

| Proton Reduction (HER) | 4H⺠+ 4e⻠→ 2H₂ | 0.00 |

| Overall Reaction | 2H₂O → 2H₂ + O₂ | ΔGⰠ= +237 kJ/mol |

Direct OWS is a single, thermodynamically demanding process where a photocatalyst uses light energy to split water into stoichiometric amounts of Hâ‚‚ and Oâ‚‚ (2:1 ratio) without any additives [20]. The primary challenge lies in the sluggish kinetics of the four-electron water oxidation reaction, which is more complex and demanding than the two-electron proton reduction [20] [19]. Furthermore, the simultaneous production of Hâ‚‚ and Oâ‚‚ in close proximity creates a potential explosion risk and often leads to inefficient separation and collection of the gases [18].

Sacrificial Agent-Assisted Systems

Sacrificial agent systems introduce electron donors (e.g., alcohols, organic acids, or sulfide/sulfite salts) that react irreversibly with photogenerated holes. This selectively enhances the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) by preventing hole accumulation and suppressing electron-hole recombination [21] [18]. While this approach significantly boosts Hâ‚‚ production rates and allows the use of a wider range of photocatalysts, it is not a sustainable method for overall water splitting. The sacrificial agents are consumed in the process, generating waste products and increasing operational costs [18].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Direct OWS and Sacrificial Agent Systems.

| Characteristic | Direct Overall Water Splitting | Sacrificial Agent System |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Complete water decomposition via photocatalysis | HER enhanced by hole scavengers; OER suppressed |

| Stoichiometry | 2Hâ‚‚ : 1Oâ‚‚ | Hâ‚‚ only; no stoichiometric Oâ‚‚ evolution |

| Thermodynamic Demand | High (≥1.23 eV bandgap, aligned bands) | Lower (HER catalyst sufficient) |

| Kinetic Challenge | Slow 4-electron OER kinetics | Fast hole scavenging; enhanced HER kinetics |

| Gas Output | Hâ‚‚/Oâ‚‚ mixture requiring separation | Pure Hâ‚‚ stream |

| Sustainability | Sustainable (Hâ‚‚O only input) | Unsustainable (sacrificial agent consumed) |

| Common Catalysts | Z-scheme systems (e.g., CdS/BiVOâ‚„), heterojunctions | CdS, TiOâ‚‚ modified with non-noble metals |

| Reported Hâ‚‚ Rate | ~254 µmol hâ»Â¹ (gas-solid biphase) [4] | 108-568 µmol hâ»Â¹ (with various agents) [20] [21] |

Experimental Protocols

This protocol outlines the procedure for constructing and operating a liquid-phase Z-scheme system using n-type CdS and BiVOâ‚„ with a [Fe(CN)₆]³â»/â´â» redox mediator for stoichiometric Hâ‚‚ and Oâ‚‚ production [20].

Materials and Equipment

- Photocatalysts: CdS nanoparticles, BiVOâ‚„ (decahedral, cobalt-directed facet asymmetry)

- Cocatalysts: Pt@CrOx (for CdS), Co₃O₄ (for BiVO₄)

- Redox Mediator: Potassium ferricyanide/ferrocyanide (K₃[Fe(CN)₆]/K₄[Fe(CN)₆])

- Reactor: Two-compartment photocatalytic reactor with a proton exchange membrane (PEM)

- Light Source: 300 W Xe lamp with a 420 nm cutoff filter or a 450 nm monochromatic light source

- Gas Chromatograph: Equipped with a TCD detector for Hâ‚‚ and Oâ‚‚ quantification

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Photocatalyst Preparation (CdS/Pt@CrOx): Synthesize CdS nanoparticles hydrothermally from Na₂S and Cd(NO₃)₂. Decorate with 0.4 wt% Pt nanoparticles via photodeposition from H₂PtCl₆. Subsequently, deposit a CrOx shell on the Pt nanoparticles by photodeposition from K₂CrO₄ solution (target Pt:CrOx mass ratio of 1:1) [20].

- Photocatalyst Preparation (BiVO₄-Co₃O₄): Synthesize decahedral BiVO₄ with cobalt-mediated facet engineering. Load Co₃O₄ nanoparticles as an OER cocatalyst [20].

- Stability Coating: Apply a protective TiOâ‚‚ coating on CdS and a SiOâ‚‚ coating on BiVOâ‚„ via a sol-gel method to suppress photocorrosion and redox mediator degradation [20].

- Reactor Setup: Place the CdS-based HER photocatalyst (50 mg) in one compartment of the reactor and the BiVO₄-based OER photocatalyst (50 mg) in the other. Fill both sides with an aqueous solution containing 2 mM K₃[Fe(CN)₆] and 2 mM K₄[Fe(CN)₆] as the electron mediator [20].

- Reaction Execution: Seal the reactor and purge with argon to remove air. Irradiate the system under visible light (λ ≥ 420 nm or at 450 nm) with constant magnetic stirring. Maintain the temperature at 25°C using a water cooling jacket.

- Product Analysis: Use gas-tight syringes to periodically sample the headspace (50 µL) from each compartment. Inject the sample into the GC for H₂ (from the HER compartment) and O₂ (from the OER compartment) quantification. Confirm stoichiometry via a H₂:O₂ ratio close to 2:1.

Visualization of the Z-Scheme Mechanism

The following diagram illustrates the electron transfer pathway in the CdS/BiVOâ‚„ Z-scheme system.

Protocol 2: Hydrogen Production Using a Biomass Sacrificial Agent

This protocol describes hydrogen production using a low-cost, non-noble metal catalyst (Cu(OH)₂–Ni(OH)₂/TiO₂) and treated biomass (corn straw) as a sacrificial agent [21].

Materials and Equipment

- Photocatalyst: Cu(OH)₂–Ni(OH)₂/TiO₂ with Cu:Ni molar ratio of 4:1

- Sacrificial Agent: Urea-treated corn straw

- Reactor: Pyrex top-irradiation reaction vessel connected to a closed gas circulation system

- Light Source: 300 W Xe lamp simulating solar spectrum

- Gas Chromatograph: Equipped with a TCD detector

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Biomass Treatment: Suspend crushed corn straw in a urea solution (concentration: 5-10 wt%). Heat the mixture at 80°C for 2 hours to remove lignin, disrupt the fiber structure, and introduce nitrogen-containing electron-donating groups. Wash and dry the treated biomass [21].

- Catalyst Synthesis: Prepare the Cu(OH)₂–Ni(OH)₂/TiO₂ composite catalyst via chemical deposition. Impregnate TiO₂ (P25) with aqueous solutions of copper and nickel nitrates to achieve a total metal hydroxide loading of 0.5 wt% and a Cu:Ni ratio of 4:1. Precipitate the hydroxides using a NaOH solution, followed by washing, drying, and calcining at 300°C for 2 hours [21].

- Reaction Setup: Add 100 mg of catalyst and 100 mg of treated corn straw to 150 mL of deionized water in the reaction vessel. Seal the system and evacuate to remove air.

- Reaction Execution: Irradiate the suspension with the Xe lamp while maintaining constant magnetic stirring. Use a cooling water jacket to keep the reaction at ambient temperature.

- Product Analysis: Measure the total volume of evolved gas using a gas burette. Analyze the gas composition periodically (e.g., every hour) by GC-TCD to determine hydrogen concentration and production rate. The typical expected yield is approximately 27 µmol Hâ‚‚ hâ»Â¹ under optimal conditions [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions and Materials for Photocatalytic Water Splitting Research.

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example/Chemical Formula |

|---|---|---|

| HER Photocatalysts | Absorbs light and reduces protons to Hâ‚‚. | CdS nanoparticles [20], CdS/CoFeâ‚‚Oâ‚„ heterojunction [4] |

| OER Photocatalysts | Absorbs light and oxidizes water to Oâ‚‚. | BiVOâ‚„ (cobalt-directed) [20], various metal oxides [19] |

| Non-Noble Metal Catalysts | Low-cost alternative for HER. | Cu(OH)₂–Ni(OH)₂/TiO₂ composite [21] |

| Redox Mediators | Shuttles electrons between OER and HER catalysts in Z-schemes. | [Fe(CN)₆]³â»/[Fe(CN)₆]â´â» pair [20], IO₃â»/Iâ» pair |

| Sacrificial Agents (Chemical) | Consumes holes to enhance HER kinetics. | Na₂S/Na₂SO₃ [18], methanol [18], triethanolamine (TEOA) [18] |

| Sacrificial Agents (Biomass) | Renewable, electron-donating hole scavengers. | Urea-treated corn straw [21], other processed biomass |

| Cocatalysts | Enhances charge separation and surface reaction kinetics. | Pt@CrOx (HER, suppresses back reaction) [20], Co₃O₄ (OER) [20] |

| Stability Coatings | Protects photocatalysts from corrosion/deactivation. | TiOâ‚‚ coating (on CdS) [20], SiOâ‚‚ coating (on BiVOâ‚„) [20] |

| Spiro[4.4]nona-1,3,7-triene | Spiro[4.4]nona-1,3,7-triene, CAS:24430-29-3, MF:C9H10, MW:118.18 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Gitorin | Gitorin|C29H44O10|For Research Use | Gitorin (C29H44O10) is a cardenolide for research. This product is For Research Use Only and is not intended for diagnostic or personal use. |

Direct overall water splitting and sacrificial agent systems represent two distinct philosophies in photocatalytic hydrogen production research. The choice between them involves a direct trade-off between sustainability and efficiency. Direct OWS, particularly via advanced Z-scheme systems, offers a truly sustainable and stoichiometric path to hydrogen and oxygen but faces significant challenges in efficiency, stability, and gas separation [20] [19]. Sacrificial agent systems, including those using renewable biomass, provide a powerful platform to achieve high hydrogen evolution rates, study HER catalysts, and valorize waste products, albeit at the cost of consuming reagents [21] [18].

The future of the field lies in addressing the fundamental limitations of both pathways. For direct OWS, this means developing more robust and efficient heterojunctions and Z-schemes with effective charge separation mechanisms [19]. For sacrificial systems, the focus should shift towards using truly sustainable, renewable, and low-cost electron donors. Ultimately, the insights gained from both approaches are invaluable for driving the development of photocatalytic technology toward scalable and economically viable solar hydrogen production.

The escalating global energy consumption and the environmental repercussions of finite fossil fuels have catalyzed intensive research into renewable alternatives [22]. Solar energy, being abundant and inexhaustible, presents a particularly promising pathway [23]. Among the various strategies for solar energy conversion, photocatalytic water splitting—the process of using light to decompose water into hydrogen (H₂) and oxygen (O₂)—has garnered significant attention as a method for producing clean, storable hydrogen fuel [22] [23].

A central challenge in this field is designing photocatalyst systems that simultaneously possess strong light absorption across the visible spectrum and potent redox capabilities, properties that are often mutually exclusive in single-component semiconductors [22] [23]. Z-scheme photocatalytic systems, which mimic the natural photosynthetic process found in plants, offer an ingenious solution to this dilemma [23]. By integrating two different semiconductors with a reversible electron mediator, these systems can achieve efficient spatial separation of photogenerated charge carriers while maintaining high reduction and oxidation powers, thereby enabling efficient overall water splitting [22].

This application note delineates the fundamental principles of Z-scheme systems, surveys the developmental trajectory from first to third-generation configurations, and provides detailed experimental protocols for constructing and characterizing both liquid-phase and solid-state Z-scheme systems. Designed for researchers and scientists engaged in renewable energy and materials science, this document aims to serve as a practical guide for implementing these advanced photocatalytic architectures.

Fundamental Principles and System Evolution

Operational Mechanism of Z-Scheme Systems

The fundamental mechanism of a Z-scheme photocatalytic system for overall water splitting involves the synergistic operation of two semiconductors: a Hydrogen Evolution Photocatalyst (HEP) and an Oxygen Evolution Photocatalyst (OEP) [22] [23]. The process can be broken down into several key stages, illustrated in the diagram below.

Diagram 1: Charge transfer mechanism in a Z-scheme system.

- Photoexcitation: Upon illumination by visible light, both the HEP and OEP absorb photons with energy equal to or greater than their respective bandgaps. This promotes electrons (eâ») from their Valence Bands (VB) to their Conduction Bands (CB), simultaneously generating holes (hâº) in the VBs [22].

- Charge Migration and Reaction: In the HEP, the photogenerated electrons in the CB migrate to the surface and reduce protons (Hâº) to hydrogen gas (Hâ‚‚). In the OEP, the photogenerated holes in the VB migrate to the surface and oxidize water (Hâ‚‚O) to oxygen gas (Oâ‚‚) and protons (Hâº) [23].

- Electron Mediation: The key to the Z-scheme is the recombination of electrons from the CB of the OEP with holes from the VB of the HEP via an electron mediator. This critical step prevents the accumulation of charge in one photocatalyst and allows the remaining electrons in the HEP and holes in the OEP to retain their high redox potential [22]. The electron transfer route—from the CB of the OEP, through the mediator, to the VB of the HEP—forms a "Z"-shaped pattern in the energy diagram, giving the system its name [22].

Generations of Z-Scheme Systems

Z-scheme systems have evolved through three distinct generations, primarily distinguished by the nature of the electron mediator [23]. The following table summarizes the key characteristics of each generation.

Table 1: Evolution of Z-Scheme Photocatalytic Systems

| Generation | Mediator Type | Example Mediators | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First (Liquid-Phase) | Soluble Redox Ionic Pairs [23] | IO₃â»/Iâ», Fe³âº/Fe²âº, [Fe(CN)₆]³â»/â´â» [20] |

Simple construction; Spatial separation of Hâ‚‚/Oâ‚‚ evolution [20] | Back-reactions; Light shielding by mediators; Gas separation required [23] |

| Second (Solid-State) | Conductive Solid Materials [24] | Reduced Graphene Oxide (RGO), Au, Ag [24] | Suppresses back-reactions; No light shielding [24] | Requires intimate physical contact between components [23] |

| Third (Direct Z-Scheme) | None (Direct Interface) [22] | N/A | Simplest structure; Most efficient interfacial charge transfer [22] | Demanding synthesis; Limited material pairs form effective interfaces [22] |

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

The following table catalogs key materials and reagents commonly employed in the construction of high-performance Z-scheme systems, as evidenced by recent literature.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Z-Scheme Water Splitting

| Material / Reagent | Function / Role | Specific Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Evolution Photocatalyst (HEP) | Absorbs light and catalyzes proton reduction to Hâ‚‚ [23]. | CdS: Broad visible-light absorption (~2.4 eV bandgap); requires cocatalysts for high activity [20]. Smâ‚‚Tiâ‚‚Oâ‚…Sâ‚‚ (STOS): Oxysulfide; harvests light up to 650 nm; superior stability vs. pure sulfides [24]. |

| Oxygen Evolution Photocatalyst (OEP) | Absorbs light and catalyzes water oxidation to Oâ‚‚ [23]. | BiVOâ‚„ (BVO): Well-established, visible-light-responsive OEP; can be facet-engineered for enhanced activity [20] [24]. |

| Electron Mediator | Shuttles electrons from the OEP to the HEP [22] [23]. | [Fe(CN)₆]³â»/â´â»: Liquid-phase mediator; enabled 10.2% AQY with CdS/BiVOâ‚„ [20]. Reduced Graphene Oxide (RGO): Solid mediator; excellent electron transfer capability in STOS/BiVOâ‚„ system [24]. |

| Cocatalysts | Enhances charge separation and provides active sites for surface redox reactions [20] [24]. | Pt@CrOâ‚“: Core-shell HER cocatalyst; promotes oxidation of mediator while suppressing back-reactions [20]. CoOâ‚“ / IrOâ‚‚: OER cocatalysts deposited on OEP surfaces to accelerate slow water oxidation kinetics [24]. |

| Protective Coatings | Improves photostability and suppresses corrosion or undesired side reactions [20]. | TiOâ‚‚ / SiOâ‚‚ Coatings: Applied to photocatalyst surfaces (e.g., on CdS or BiVOâ‚„) to inhibit photocorrosion and mediator degradation [20]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Construction of a Liquid-Phase Z-Scheme with [Fe(CN)₆]³â»/â´â» Mediator

This protocol outlines the synthesis of an efficient and stable n-type sulfide-based Z-scheme system, adapted from a recent high-performance study [20]. The experimental workflow is summarized in the diagram below.

Diagram 2: Workflow for liquid-phase Z-scheme assembly.

Synthesis of CdS Hydrogen Evolution Photocatalyst (HEP)

- Materials: Cadmium nitrate tetrahydrate (Cd(NO₃)₂·4H₂O), Sodium sulfide (Na₂S), Deionized water.

- Procedure:

- Dissolve 10 mmol of Cd(NO₃)₂·4H₂O and 20 mmol of Na₂S separately in 40 mL of deionized water each.

- Mix the two solutions rapidly under vigorous stirring at room temperature. A yellow precipitate of CdS will form immediately.

- Continue stirring for 1 hour for aging.

- Transfer the suspension to a 100 mL Teflon-lined autoclave and heat at 180°C for 12 hours.

- After cooling naturally, collect the product by centrifugation, wash thoroughly with deionized water and ethanol, and dry at 60°C in a vacuum oven [20].

Synthesis of Facet-Engineered BiVOâ‚„ Oxygen Evolution Photocatalyst (OEP)

- Materials: Bismuth nitrate pentahydrate (Bi(NO₃)₃·5H₂O), Ammonium metavanadate (NH₄VO₃), Cobalt acetate (Co(CH₃COO)₂), Nitric acid (HNO₃), Deionized water.

- Procedure:

- Dissolve 5 mmol of Bi(NO₃)₃·5H₂O in 10 mL of 4 M HNO₃ (Solution A).

- Dissolve 5 mmol of NH₄VO₃ in 40 mL of deionized water heated to 70°C (Solution B).

- Slowly add Solution A to Solution B under stirring. Adjust the pH to ~7 using aqueous ammonia.

- Add 0.5 mmol of Co(CH₃COO)₂ as a structure-directing agent.

- Transfer the mixture to a 100 mL autoclave and heat at 180°C for 6 hours.

- Collect the resulting yellow powder by centrifugation, wash, and dry at 60°C [20].

Deposition of Pt@CrOâ‚“ Core-Shell Cocatalyst on CdS

- Materials: Chloroplatinic acid (H₂PtCl₆), Potassium chromate (K₂CrO₄), Methanol, Deionized water.

- Procedure:

- Disperse 200 mg of as-synthesized CdS in 100 mL of a 10 vol% methanol aqueous solution.

- Add H₂PtCl₆ solution to achieve a 0.4 wt% Pt loading.

- Irradiate the suspension with a 300 W Xe lamp under magnetic stirring for 1 hour to photodeposit Pt nanoparticles.

- Add Kâ‚‚CrOâ‚„ solution (Pt:CrOâ‚“ mass ratio of 1:1) to the suspension.

- Continue irradiation for another 30 minutes to photodeposit the CrOâ‚“ shell onto the Pt nanoparticles, forming the core-shell Pt@CrOâ‚“ structure [20].

Application of Protective Oxide Coatings

- TiOâ‚‚ Coating on CdS: Use a sol-gel method to coat the Pt@CrOâ‚“/CdS particles with a thin, conformal layer of TiOâ‚‚. This layer is critical for suppressing the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) and photocorrosion [20].

- SiO₂ Coating on BiVO₄: Employ a Stöber method or similar to coat the Co₃O₄/BiVO₄ particles with a thin SiO₂ layer. This inhibits detrimental side reactions at the OEP/mediator interface [20].

Photocatalytic Water Splitting Reaction

- Reaction Setup: Use a top-irradiation reaction vessel connected to a closed gas circulation system.

- Procedure:

- Suspend 50 mg of Pt@CrOₓ/TiO₂/CdS (HEP) and 50 mg of Co₃O₄/SiO₂/BiVO₄ (OEP) in 100 mL of an aqueous solution containing 2 mM K₄[Fe(CN)₆] as the electron mediator.

- Evacuate the system thoroughly to remove air.

- Irradiate the suspension with a 300 W Xe lamp equipped with a cut-off filter (λ ≥ 420 nm).

- Analyze the evolved gases periodically using online gas chromatography (GC) to quantify Hâ‚‚ and Oâ‚‚ production [20].

Protocol 2: Construction of a Solid-State Z-Scheme with RGO Mediator

This protocol details the assembly of a solid-state Z-scheme using an oxysulfide HEP and an RGO electron mediator [24].

Synthesis and Modification of Smâ‚‚Tiâ‚‚Oâ‚…Sâ‚‚ (STOS) HEP

- Synthesis: Prepare high-crystallinity STOS via a solid-state reaction using a CaClâ‚‚/LiCl eutectic flux mixture, which yields large, plate-like single crystals [24].

- Surface Modification (Cr₂O₃/Pt/IrO₂ Loading):

- First, photodeposit IrOâ‚‚ nanoparticles (sub-1 nm size) as an OER cocatalyst.

- Subsequently, photodeposit Pt nanoparticles (2-4 nm) as an HER cocatalyst.

- Finally, photodeposit a layer of Cr₂O₃ over the Pt nanoparticles. This Cr₂O₃ layer is crucial for suppressing the backward reaction (H₂ and O₂ recombining to form water) [24].

Synthesis and Modification of BiVOâ‚„ (BVO) OEP

- Synthesis: Synthesize BVO via a hydrothermal method to ensure high crystallinity [24].

- Cocatalyst Loading (CoOâ‚“): Photodeposit CoOâ‚“ nanoparticles onto the BVO surface to enhance its intrinsic OER activity [24].

Assembly of the Solid-State Z-Scheme

- Materials: Graphene Oxide (GO) dispersion.

- Procedure:

- Mix the as-prepared CoOâ‚“/BVO powder with a GO dispersion in water.

- Irradiate the mixture with UV-Vis light. During irradiation, the CoOâ‚“/BVO acts as a photocatalyst to reduce GO to RGO, which deposits directly onto its surface, forming an RGO/CoOâ‚“/BVO composite.

- Physically mix the RGO/CoOₓ/BVO composite with the modified Cr₂O₃/Pt/IrO₂/STOS HEP powder. The RGO sheet acts as a solid-state electron mediator, facilitating charge transfer between the BVO OEP and the STOS HEP [24].

Photocatalytic Performance Evaluation

- Suspend 100 mg of the solid-state Z-scheme powder in pure water (no sacrificial agents or mediators).

- Evacuate the reaction system.

- Irradiate under visible light (λ ≥ 420 nm).

- Monitor stoichiometric Hâ‚‚ and Oâ‚‚ evolution (2:1 ratio) using GC. This system has demonstrated stability for over 100 hours [24].

Characterization and Data Analysis

Confirming the Z-scheme charge transfer mechanism, as opposed to a conventional Type-II heterojunction, is critical. The following table outlines key characterization techniques.

Table 3: Key Techniques for Characterizing Z-Scheme Mechanisms

| Method | Application & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Photodeposition | Spatial mapping of redox sites. E.g., Photodeposition of PbO₂ (from Pb²⺠oxidation) on the OEP and Pt (from PtCl₆²⻠reduction) on the HEP confirms spatially separated reduction and oxidation sites [22]. |

| Radical Trapping / ESR | Detecting reactive oxygen species (ROS). The presence of •OH radicals (from water oxidation by OEP holes) and the absence of O₂•⻠radicals (which would form if OEP electrons reduced O₂) corroborates the Z-scheme path [22]. |

| In-situ XPS | Directly observing electron flow. A shift in the core-level peaks of the HEP to higher binding energy (electron loss) and the OEP to lower binding energy (electron gain) under illumination provides direct evidence of interfacial electron transfer [22]. |

| Apparent Quantum Yield (AQY) | Quantifying efficiency at specific wavelengths. AQY is calculated to benchmark performance: AQY (%) = (Number of reacted electrons / Number of incident photons) × 100 = (2 × Number of evolved H₂ molecules × N_A) / (Incident photon flux × Time) × 100 (where N_A is Avogadro's constant) [20] [24]. |

Z-scheme photocatalytic systems represent a sophisticated and highly promising strategy for achieving efficient solar-driven hydrogen production via water splitting. By successfully mimicking the fundamental principles of natural photosynthesis, these systems overcome the inherent limitations of single-component photocatalysts. The ongoing evolution from liquid-phase to solid-state and direct Z-scheme configurations reflects a concerted effort to enhance charge transfer efficiency and system stability.

The experimental protocols detailed herein, centered on high-performance material combinations like CdS/BiVO₄ and STOS/BiVO₄, provide a practical roadmap for researchers. Key to success is the meticulous design of each component—the HEP, OEP, mediator, and cocatalysts—and their integration into a cohesive system. As research progresses, addressing challenges related to scalability, cost reduction, and further enhancement of long-term durability will be paramount for translating the exceptional potential of Z-scheme systems into practical, commercial technologies for renewable hydrogen production.

The escalating global energy demand, projected to nearly double from 17 terawatts in 2013 by 2050, coupled with the urgent need to reduce fossil fuel dependence, has positioned photocatalytic hydrogen production as a pivotal sustainable technology [25]. This process mimics natural photosynthesis by utilizing semiconductor materials to harness solar energy and split water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen, offering a renewable pathway to carbon-free energy [25]. The foundational discovery by Fujishima and Honda in the 1970s demonstrated this potential using titanium dioxide (TiO₂), establishing a paradigm that has guided research for decades [25]. The overall water splitting reaction is a thermodynamically uphill process with a Gibbs free energy change (ΔG°) of +237.13 kJ/mol, requiring photocatalysts that can efficiently absorb light and generate electron-hole pairs with sufficient potential to drive both hydrogen and oxygen evolution reactions [25]. While TiO₂ established the field's foundation, its inherent limitations spurred the development of advanced materials including graphitic carbon nitride (g-C₃N₄) and emerging nanostructures, each representing significant evolutionary milestones in photocatalyst design [25] [26].

Historical Foundation: Titanium Dioxide (TiOâ‚‚) and Its Limitations

TiOâ‚‚ emerged as the pioneering photocatalyst due to its robust photochemical stability, non-toxicity, and economic viability [25] [27]. The material functions through a well-established mechanism where photon absorption with energy equal to or greater than its bandgap (~3.2 eV for anatase phase) excites electrons from the valence band to the conduction band, creating electron-hole pairs that drive water reduction and oxidation reactions [25]. However, TiOâ‚‚ suffers from two critical limitations: its wide bandgap restricts light absorption to the ultraviolet region (representing only ~4% of the solar spectrum), and it exhibits rapid recombination of photogenerated charge carriers, resulting in low quantum efficiency [25] [27].

Table 1: Key Limitations and Engineering Strategies for TiOâ‚‚

| Limitation | Impact on Performance | Engineering Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Wide Bandgap (~3.2 eV) | Absorbs only UV light; limited to ~4% of solar spectrum [25]. | Doping with metals/non-metals to create intra-bandgap states [25] [2]. |

| Rapid Electron-Hole Recombination | Low quantum efficiency; reduced charge carriers for redox reactions [25]. | Heterojunction construction with narrow-gap semiconductors (e.g., CdS, BiVOâ‚„) [2] [27]. |

| Low Surface Area (Bulk Morphology) | Limited active sites for water adsorption and reaction [28]. | Nanostructuring to create nanoparticles, nanotubes, and mesoporous structures [29]. |

Researchers have developed sophisticated strategies to overcome these limitations. Doping with foreign elements like metals, nitrogen, or sulfur introduces intermediate energy levels within the bandgap, effectively narrowing the apparent bandgap and enhancing visible light absorption [25] [2]. Constructing heterojunctions by coupling TiO₂ with narrow bandgap semiconductors (e.g., CdS, g-C₃N₄) facilitates efficient charge separation through internal electric fields, significantly reducing recombination losses [2] [27]. Despite these improvements, the quest for more efficient visible-light-driven photocatalysts motivated the exploration of entirely new material systems, culminating in the rise of g-C₃N₄.

The Rise of Graphitic Carbon Nitride (g-C₃N₄)

Graphitic carbon nitride (g-C₃N₄) has emerged as a transformative metal-free polymeric photocatalyst, addressing several fundamental limitations of TiO₂. Its two-dimensional layered structure, moderate bandgap of approximately 2.7 eV (corresponding to an absorption edge of ~460 nm), and exceptional thermal/chemical stability have positioned it as a superior visible-light-responsive material [26] [30]. The material can be synthesized through straightforward thermal polycondensation of low-cost nitrogen-rich precursors such as urea, melamine, or dicyandiamide, making it economically attractive for large-scale applications [28] [27]. g-C₃N₄ maintains structural integrity up to approximately 600°C in air and demonstrates remarkable stability in both acidic and alkaline conditions, ensuring longevity during photocatalytic operation [27].

Despite its advantages, pristine g-C₃N₄ suffers from high charge carrier recombination rates and insufficient surface activity, limiting its photocatalytic efficiency [26] [30]. Consequently, researchers have developed extensive engineering strategies to unlock its full potential, leading to dramatic enhancements in hydrogen production performance.

Table 2: Performance Enhancement of g-C₃N₄ via Engineering Strategies

| Engineering Strategy | Specific Approach | Impact on Performance | Reported Hâ‚‚ Production Enhancement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elemental Doping | Non-metal (e.g., P, S) or metal (e.g., Fe, Cu) doping [26]. | Modifies electronic structure; improves charge separation [30]. | Up to 10â´-fold increase in Hâ‚‚ production rates [30]. |

| Nanostructure Design | Thermal, microwave, or chemical exfoliation into nanosheets [28]. | Increases surface area; shortens charge migration paths [28]. | Expanded surface area by 26x; 50% longer fluorescence lifetime [30]. |

| Heterostructure Construction | Forming composites (e.g., g-C₃N₄/ZnO, g-C₃N₄/CdS) [26] [28]. | Enhances charge separation; preserves redox properties [30]. | Hundredfold surge in H₂ generation performance [30]. |

Experimental Protocol: Synthesis and Exfoliation of g-C₃N₄ Nanosheets

Principle: This protocol describes the synthesis of bulk g-C₃N₄ via thermal polycondensation of urea, followed by exfoliation into ultrathin nanosheets using a combined microwave-thermal treatment. Exfoliation significantly enhances photocatalytic performance by increasing surface area, exposing active sites, and improving charge separation efficiency [28].

Materials:

- Urea (CO(NH₂)₂, ≥99%, Alfa Aesar)

- Ceramic crucible with lid

- Muffle furnace

- Microwave reactor

- Deionized water

Procedure:

- Bulk g-C₃N₄ Synthesis: Place 20 g of urea into a ceramic crucible and cover firmly with the lid. Transfer the crucible to a muffle furnace. Heat the furnace gradually to 550°C at a ramp rate of 5°C/min and maintain this temperature for 2 hours under air. After the thermal treatment, allow the furnace to cool naturally to room temperature. Collect the resulting light-yellow solid, which is bulk g-C₃N₄, and gently grind it into a fine powder using an agate mortar and pestle [28].

- Combined Microwave-Thermal Exfoliation: Weigh out 500 mg of the as-synthesized bulk g-C₃N₄ powder and transfer it to a microwave-safe container. Subject the powder to microwave irradiation at 800 W for 15 minutes. This rapid heating process causes the bulk material to expand and partially exfoliate. Subsequently, transfer the microwave-treated powder to a ceramic boat and place it in a tube furnace. Heat the sample to 500°C for 2 hours under ambient atmosphere to complete the exfoliation process, resulting in porous g-C₃N₄ nanosheets [28].

Characterization and Expected Outcomes:

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD): The characteristic (002) peak at ~27.5°, corresponding to interlayer stacking, will show significant broadening and a slight shift to a lower angle, confirming successful exfoliation and reduced layer thickness [28].

- Surface Area Analysis (BET): The exfoliated nanosheets will exhibit a substantially higher specific surface area (often exceeding 60 m²/g) compared to the bulk material (typically <10 m²/g), providing more active sites for the photocatalytic reaction [28].

- UV-Vis Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy: The exfoliated material may show a slight blue shift in the absorption edge and enhanced light absorption capabilities due to quantum confinement effects and improved light scattering [28].

Emerging Photocatalytic Materials and Paradigms

The evolution of photocatalysts extends beyond g-C₃N₄ to several novel material classes engineered for superior performance.

MNbâ‚‚O6 Niobates: Transition metal niobates (MNbâ‚‚O6, where M = Cu, Ni, Mn, Co) represent a class of emerging photocatalysts with tunable band structures (~2.0-3.0 eV), chemical robustness, and visible-light activity [27]. These materials typically crystallize in orthorhombic or monoclinic structures, and their band edges can be modulated by selecting different transition metal cations. Particularly promising are heterostructures combining MNbâ‚‚O6 with g-C₃Nâ‚„ or TiOâ‚‚, which have demonstrated hydrogen production rates as high as 146 mmol hâ»Â¹ gâ»Â¹ under visible light [27].

Single-Atom Catalysts (SACs): The frontier of photocatalytic research has advanced to the atomic level with Single-Atom Catalysts. These systems maximize atomic utilization by anchoring isolated metal atoms (e.g., Pt) to semiconducting substrates, providing highly uniform active sites that enhance charge separation and proton reduction kinetics. For instance, Pt single atoms supported on CdS nanoparticles have achieved exceptional hydrogen evolution rates of 19.77 mmol gâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹ [2].

Bio-inspired and AI-Designed Systems: Bio-inspired photocatalytic systems combine semiconductors with hydrogenase enzymes to mimic natural photosynthesis, achieving high selectivity and efficiency [2]. Concurrently, artificial intelligence and machine learning are revolutionizing catalyst discovery by predicting optimal band structures, surface terminations, and co-catalyst combinations before experimental synthesis, accelerating the development of next-generation materials [2] [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents for Photocatalyst Synthesis and Testing

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Urea (CO(NH₂)₂) | Low-cost, nitrogen-rich precursor for g-C₃N₄ synthesis [28]. | Thermal polycondensation at ~550°C to form bulk g-C₃N₄ [28]. |

| Platinum (Pt) Nanoclusters | Co-catalyst for the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction (HER) [26]. | Photo-deposition onto g-C₃N₄ or TiO₂ to enhance H₂ evolution kinetics [26] [2]. |

| Cadmium Sulfide (CdS) | Narrow bandgap semiconductor for constructing heterojunctions [2]. | Coupled with g-C₃N₄ or TiO₂ to form composites with enhanced visible light activity [2] [4]. |

| Ammonia (NH₃) | Source for nitrogen doping in TiO₂ bandgap engineering [25]. | Annealing TiO₂ in NH₃ atmosphere to create N-doped TiO₂ with visible light response [25]. |

| Sodium Sulfide (Naâ‚‚S) | Sacrificial agent in photocatalytic testing [29]. | Scavenges photogenerated holes, thereby suppressing charge recombination and enhancing Hâ‚‚ production rates [29]. |

| (3-Chlorophenyl)phosphane | (3-Chlorophenyl)phosphane, CAS:23415-73-8, MF:C6H6ClP, MW:144.54 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Aspirin glycine calcium | Aspirin glycine calcium, CAS:22194-39-4, MF:C11H11CaNO6, MW:293.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced System Engineering and Reaction Platforms

The evolution of photocatalysis encompasses not only material development but also revolutionary advances in reaction system engineering. Conventional photocatalytic water splitting typically involves dispersing photocatalyst powders in an aqueous solution, creating a solid-liquid-gas triphase system that suffers from low solar energy utilization efficiency and slow mass transfer of reactant/product gases [4].

A groundbreaking innovation addresses these limitations through an immobilized photothermal-photocatalytic integrated system. This system utilizes a photothermal substrate, such as an annealed melamine sponge (AMS), which efficiently converts sunlight, including underutilized near-infrared light (>50% of the solar spectrum), into heat. This heat locally generates water vapor at the catalyst interface, transforming the conventional triphase system into a more efficient gas-solid biphase system [4]. In this configuration, a high-performance photocatalyst like a CdS/CoFeâ‚‚Oâ‚„ p-n heterojunction is immobilized on the AMS substrate. This design enables a synergistic process of liquid water evaporation and vapor-phase water splitting, significantly reducing gas transport resistance and enhancing the overall reaction temperature. This innovative system has demonstrated a remarkable hydrogen evolution rate of 254.1 μmol hâ»Â¹, representing a substantial leap forward compared to traditional slurry systems [4].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the strategic evolution and key decision points in developing advanced photocatalytic systems, from material selection to system engineering.

The evolution of photocatalysts from TiO₂ to g-C₃N₄ and toward atomic-level designs reflects a concerted effort to master the complex interplay between light absorption, charge dynamics, and surface catalysis. This progression has been marked by key transitions: from wide to narrow bandgap materials, from bulk to nanostructured and two-dimensional morphologies, and from single-component systems to sophisticated heterojunctions and single-atom architectures [25] [26] [2]. The field is now transitioning from pure material innovation to integrated system-level design, where engineered photocatalysts must function as components within practical renewable energy systems [2] [4]. The ultimate challenge is no longer merely demonstrating scientific feasibility but achieving technological viability—meeting benchmarks for efficiency, stability, and cost-effectiveness that will enable sunlight to become a practical energy currency for a sustainable hydrogen economy [2].

Advanced Materials and Innovative Reactor Designs for Enhanced Hydrogen Evolution

The escalating global energy demand and the pressing need to transition away from fossil fuels have intensified research into sustainable hydrogen production via photocatalytic water splitting. This process, which converts solar energy directly into chemical energy stored in hydrogen bonds, represents a cornerstone of the future clean energy economy. The efficiency of this technology hinges on the development of advanced photocatalytic materials that can overcome fundamental challenges, including limited light absorption, rapid recombination of photogenerated charge carriers, and sluggish surface reaction kinetics. In response, the field has witnessed significant advancements through the strategic engineering of nanostructures, particularly heterojunctions, Z-scheme systems, and quantum dots (QDs). These material designs enhance light harvesting, promote efficient charge separation and transport, and provide abundant active sites for redox reactions, thereby pushing the boundaries of photocatalytic performance [32] [33] [34].

This article provides a detailed examination of these engineered nanostructures within the context of photocatalytic hydrogen production. It offers application notes on their operational principles and quantitative performance, alongside detailed experimental protocols for their synthesis and evaluation, serving as a practical resource for researchers and scientists in the field.

Application Notes and Performance Analysis

Heterojunctions and Z-Scheme Systems

Heterojunctions formed by coupling two or more semiconductors are a primary strategy for improving charge separation. The Z-scheme heterostructure, inspired by natural photosynthesis, is particularly effective. It not only achieves spatial separation of electrons and holes but also preserves the strongest redox ability within the system [32] [26]. In a direct Z-scheme, the internal electric field at the interface directs the recombination of useless electrons and holes, leaving powerful charge carriers for reactions.

Material Combinations and Performance: Recent studies have explored various material combinations. The strain-engineered HfS2/Ga2SSe direct Z-scheme heterostructure demonstrates a bandgap of 1.82 eV and exhibits excellent visible light absorption, achieving a theoretical solar-to-hydrogen (STH) efficiency of 31.09% [32]. Another system, a hollow CuZnInS/ZnNiP Z-scheme heterojunction derived from metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), was developed to enhance light absorption through multiple internal reflections and provide a high specific surface area for reactions [35]. Furthermore, modifying classic heterojunctions with carbon quantum dots (CQDs) has proven beneficial. For instance, a CQDs/g-C3N4/MoO3 Z-scheme photocatalyst exhibited a broad-spectrum response to visible light, outperforming its binary counterpart [36].

Quantitative Performance Data:

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Selected Heterojunction and Z-Scheme Photocatalysts

| Photocatalyst System | Bandgap (eV) | Hydrogen Evolution Rate | Apparent Quantum Efficiency/Solar-to-Hydrogen Efficiency | Key Feature | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HfS2/Ga2SSe | 1.82 | N/A | 31.09% (STH) | Strain-tunable performance | [32] |

| CuZnInS/ZnNiP | Component: CuZnInS ~1.60 | Significantly improved | N/A | MOF-derived hollow structure | [35] |

| CQDs/g-C3N4/MoO3 | N/A | N/A | Enhanced broad-spectrum visible light response | CQDs act as electron reservoirs & for up-conversion | [36] |

| ZnS/CdS Hybrid | N/A | Enhanced coupled redox activity | N/A | Type-I heterojunction for charge separation | [37] |

Quantum Dots (QDs) and Their Hybrids

Quantum dots are nanoscale semiconductor particles (typically 2-10 nm) whose electronic properties are dominated by quantum confinement effects. This effect allows for precise tuning of their bandgap and redox potentials simply by varying their size [33] [38]. They possess a high surface-to-volume ratio, providing abundant active sites, and can facilitate short charge transport distances.

Types and Roles: QDs used in photocatalysis include semiconductor QDs (e.g., CdS, CdSe, InP), metal QDs (e.g., Au, Pt, Ag), and carbon-based QDs (CQDs) [38]. They can function as the primary light absorber (photocatalyst) or as a cocatalyst to enhance the performance of a larger semiconductor.

- Primary Photocatalysts: Semiconductor QDs like CdS and CuZnInS are directly used for their strong light-harvesting capabilities [35] [38].

- Cocatalysts: Noble metal QDs (e.g., Pt) and CQDs are often deployed as cocatalysts. They act as electron sinks, suppressing charge recombination, lowering the overpotential for hydrogen evolution, and providing active sites for the surface reaction [38] [34]. CQDs additionally exhibit up-conversion photoluminescence, converting lower-energy light to higher-energy photons, thus widening the usable solar spectrum [38] [36].

Hybrid QD Systems: Combining different QDs can yield synergistic effects. A heterostructured ZnS-CdS hybrid forms a type-I band alignment, resulting in efficient separation and transfer of electron-hole pairs. This system demonstrated a 3.5-fold activity enhancement when supported on SiO2, which helps recycle scattered light [37].

Quantitative Performance Data:

Table 2: Performance Metrics and Functions of Various Quantum Dots

| Quantum Dot Type | Example Materials | Primary Function in Photocatalysis | Key Advantage | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semiconductor QDs | CdS, CdMnS, InP, CuInS2 | Primary light absorber / photocatalyst | Size-tunable bandgap & redox potentials | [33] [38] |

| Metal QDs | Pt, Au, Ag, Ni | Cocatalyst for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction (HER) | Electron sink; reduces overpotential; SPR effect | [38] [34] |

| Carbon QDs (CQDs) | Graphene QDs, Carbon nanodots | Cocatalyst / Photosensitizer | Electron acceptor/donor; up-conversion fluorescence | [39] [38] [36] |

| MXene QDs | Ti3C2 MXene QDs | Cocatalyst | High electrical conductivity; abundant active sites | [38] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Synthesis of a Hollow Z-Scheme Heterojunction (CuZnInS/ZnNiP)

This protocol outlines the synthesis of a MOF-derived hollow heterostructure, adapted from published procedures [35].

1. Synthesis of Hollow ZnNiP Spheres * Solution Preparation: Dissolve 1.18 mmol zinc nitrate hexahydrate, 0.51 mmol nickel nitrate hexahydrate, and 1.01 mmol terephthalic acid in a solvent mixture of 50 mL N,N-dimethylacetamide (DMAC) and 10 mL ethanol. * Solvothermal Reaction: Transfer the solution to a Teflon-lined autoclave and heat at 150°C for 12 hours. * Washing: After cooling, collect the resulting precipitate by centrifugation and wash several times with ethanol and deionized water. * Drying: Dry the collected product in an oven at 60°C for 12 hours to obtain the ZnNi-MOF precursor. * Phosphidation: Mix the ZnNi-MOF precursor with sodium hypophosphite (NaH2PO2) in a 1:10 mass ratio. Heat the mixture in a tube furnace at 400°C for 2 hours under a continuous argon flow. The resulting product is hollow ZnNiP spheres.

2. Decoration with CuZnInS QDs * Precursor Solution: Dissolve 0.2 mmol copper(II) chloride dihydrate, 0.2 mmol indium(III) chloride tetrahydrate, and 0.2 mmol zinc acetate dihydrate in 40 mL of deionized water. * Substrate Addition: Add the pre-synthesized hollow ZnNiP spheres (50 mg) to the solution and stir for 30 minutes to achieve adsorption of metal ions onto the surface. * Sulfurization: Rapidly inject 2 mL of an aqueous sodium sulfide (Na2S) solution (1.5 M) into the mixture. * Reaction and Collection: Stir the reaction mixture at 60°C for 2 hours. Finally, collect the CuZnInS/ZnNiP composite product by centrifugation, wash with water and ethanol, and dry at 60°C.

Workflow Diagram:

Protocol 2: Fabrication of a CQDs-Modified Z-Scheme Photocatalyst (CQDs/g-C3N4/MoO3)

This protocol details the modification of a binary heterojunction with carbon quantum dots to enhance its performance [36].