Optimizing DFT Parameters for Metal Complexes: Best Practices for Accuracy in Drug Development and Materials Science

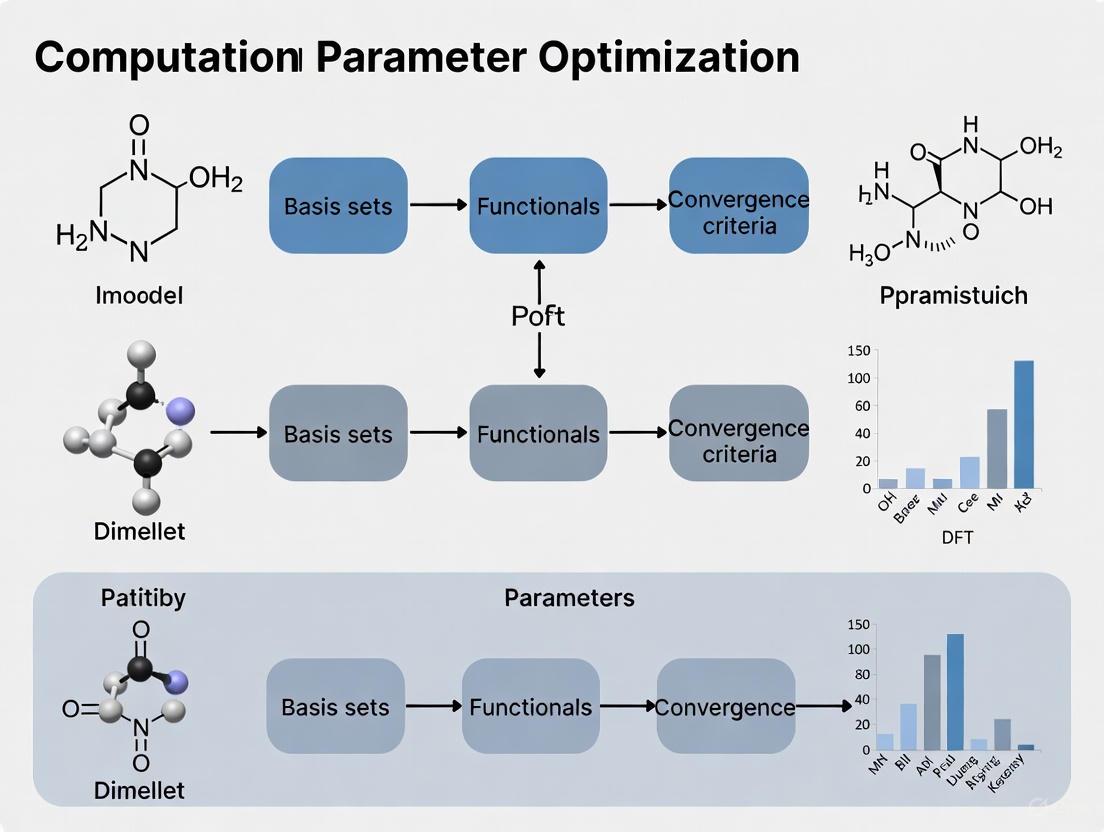

Density Functional Theory (DFT) is indispensable for studying metal complexes in catalysis, drug design, and materials science, but its predictive power hinges on the selection of computational parameters.

Optimizing DFT Parameters for Metal Complexes: Best Practices for Accuracy in Drug Development and Materials Science

Abstract

Density Functional Theory (DFT) is indispensable for studying metal complexes in catalysis, drug design, and materials science, but its predictive power hinges on the selection of computational parameters. This article provides a comprehensive, step-by-step guide for researchers and development professionals. It covers foundational principles for robust method selection, practical protocols for calculating key electronic and structural properties, strategies for troubleshooting common errors, and rigorous validation techniques. By integrating best practices from recent literature, this guide aims to enhance the reliability and efficiency of computational studies on metal-containing systems, bridging the gap between theoretical calculations and experimental application.

Laying the Groundwork: Core Principles and Parameter Selection for Robust DFT

A technical support guide for computational researchers studying metal complexes.

Troubleshooting Guides

My calculation crashes with an "error in cdiaghg or rdiaghg" or will not converge. What should I do?

This is a common SCF convergence issue that can have several causes and solutions [1]:

- Problem: The self-consistent field (SCF) process fails to converge, leading to error messages or infinite loops.

- Solutions:

- Employ advanced SCF strategies: Use a hybrid DIIS/ADIIS approach with a default 0.1 Hartree level shift and tight integral tolerance (10⁻¹⁴) [2].

- Change diagonalization algorithms: Switch to conjugate-gradient diagonalization (

diagonalization='cg'), which is slower but more robust than default algorithms [1]. - Adjust Davidson settings: Reduce the work space by setting

diago_david_ndim=2[1]. - Check system charge and multiplicity: Ensure the electronic state description matches your metal complex's expected oxidation state.

- Verify pseudopotential quality: Bad pseudopotentials with "ghost" states or non-positive charge density can cause convergence failures [1].

My calculated free energies seem incorrect, or I see large variations with molecular orientation. What's wrong?

This likely involves integration grid errors or incorrect treatment of low-frequency modes [2]:

Problem A: Inadequate integration grids

- Diagnosis: Modern functionals (mGGAs like M06, M06-2X, and B97-based functionals like wB97X-V) perform poorly on small default grids. Even "grid-insensitive" functionals like B3LYP show significant orientation-dependent free energy variations (up to 5 kcal/mol) with small grids [2].

- Solution: Use a (99,590) grid or equivalent for all DFT calculations, regardless of functional [2].

Problem B: Spurious low-frequency modes

- Diagnosis: Quasi-translational or quasi-rotational modes artificially inflate entropy corrections due to inverse proportionality between frequency and entropic contribution [2].

- Solution: Apply the Cramer-Truhlar correction, raising all non-transition state modes below 100 cm⁻¹ to 100 cm⁻¹ for entropy calculations [2].

My DFT+U calculation for metal oxides produces unrealistic band gaps or lattice parameters. How can I improve this?

The Hubbard U correction requires careful parameter selection [3] [4]:

- Problem: Standard DFT+U applying U only to metal d/f orbitals often yields inaccurate band gaps and structures for metal oxides.

- Solutions:

- Apply U to oxygen p-orbitals: Include Up for oxygen 2p orbitals alongside Ud/f for metals. Optimal (Up, Ud/f) pairs from research include [3]:

- Rutile TiO₂: (8 eV, 8 eV)

- Anatase TiO₂: (3 eV, 6 eV)

- c-CeO₂: (7 eV, 12 eV)

- Use structurally-consistent U: Calculate U at DFT level, relax structure with that U, recompute U on the DFT+U structure, and iterate until consistent [4].

- Consider DFT+U+V: For systems with significant covalency, add intersite "+V" terms to address fundamental incompleteness of DFT+U [4].

- Apply U to oxygen p-orbitals: Include Up for oxygen 2p orbitals alongside Ud/f for metals. Optimal (Up, Ud/f) pairs from research include [3]:

How do I handle symmetry-related errors in thermochemical calculations?

- Problem: Neglecting symmetry numbers in entropy calculations introduces systematic errors, particularly for reactions creating/destroying symmetry elements [2].

- Example: Deprotonation of water (C₂v, σ=2) to hydroxide (C∞v, σ=1) requires a ∆G⁰ correction of RTln(2) = 0.41 kcal/mol at room temperature [2].

- Solution: Automatically detect point groups and symmetry numbers for all species, applying appropriate entropy corrections. For manual calculation, identify rotational symmetry elements and calculate symmetry number (σ), then apply correction: ∆Gcorrected = ∆Gcalculated + RTln(σproducts/σreactants) [2].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for DFT Studies of Metal Complexes

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Standard XC Functionals | PBE, B3LYP, PBE0 [3] | General-purpose calculations with good cost-accuracy balance |

| Modern mGGA/Hybrid Functionals | M06, M06-2X, wB97X-V, wB97M-V, SCAN [2] | Improved accuracy for diverse properties but require careful setup |

| Neural Network Functionals | DM21 [5] | Potentially higher accuracy but may show oscillatory behavior in geometry optimization |

| DFT+U Methods | PBE+U, RPBE+U [3] | Treatment of strongly correlated electrons in transition metal complexes and metal oxides |

| Basis Sets | 6-31G [6], PAW pseudopotentials [3] | Balance between computational cost and accuracy |

| Software Packages | VASP [3], Gaussian, Q-Chem [2], Quantum ESPRESSO [4] | Implementation of DFT algorithms with varying capabilities |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Robust DFT Calculations for Metal Complexes

DFT Calculation Workflow

Step 1: Integration Grid Selection

- Always use a (99,590) grid or equivalent regardless of functional [2]

- Avoid default grids, especially with modern functionals (M06, SCAN, wB97X-V) which show high grid sensitivity [2]

Step 2: Functional and Basis Set Selection

- Choose functional based on target properties using best-practice recommendation matrices [7]

- Apply multi-level approaches for optimal balance of accuracy and efficiency [7]

Step 3: SCF Convergence

- Implement hybrid DIIS/ADIIS strategy with tight integral tolerance (10⁻¹⁴) [2]

- Apply 0.1 Hartree level shift by default to improve convergence [2]

Step 4: Frequency Analysis

- Project out translational/rotational modes before frequency calculation [2]

- Apply Cramer-Truhlar correction: raise frequencies < 100 cm⁻¹ to 100 cm⁻¹ for entropy calculations [2]

Step 5: Thermochemical Corrections

- Automatically detect point group and symmetry number for all species [2]

- Apply symmetry correction: ∆Gcorrected = ∆G + RTln(σproducts/σ_reactants) [2]

Protocol 2: DFT+U Parameterization for Metal Oxides

DFT+U Parameterization Workflow

Step 1: Choose U Calculation Method

- Linear Response: Computes U by introducing perturbative potential and measuring occupancy changes [3]

- Constrained RPA (cRPA): Distinguishes screening effects of localized vs. itinerant electrons [3]

- Constrained LDA (cLDA): Fixes orbital occupation numbers and observes energy differences [3]

Step 2: Apply U to Both Metal and Oxygen Orbitals

- Use optimal (Up, Ud/f) pairs specific to your metal oxide [3]: Table: Optimal Hubbard U Parameters for Common Metal Oxides

| Material | Up (eV) | Ud/f (eV) | Experimental Benchmark |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rutile TiO₂ | 8 | 8 | Band gap, lattice parameters |

| Anatase TiO₂ | 3 | 6 | Band gap, lattice parameters |

| c-ZnO | 6 | 12 | Band gap, lattice parameters |

| c-ZnO₂ | 10 | 10 | Band gap, lattice parameters |

| c-CeO₂ | 7 | 12 | Band gap, lattice parameters |

Step 3: Structural Consistency Cycle

- Calculate U at DFT level → Relax structure with this U → Recompute U on DFT+U structure → Repeat until convergence [4]

- This prevents bond over-elongation common with large U values [4]

Step 4: Machine Learning Enhancement (Optional)

- Train supervised ML models on DFT+U results for rapid prediction of optimal U values [3]

- Simple regression algorithms can accurately predict band gaps at fraction of computational cost [3]

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the most common mistakes in DFT studies of metal complexes?

The most prevalent issues include [2]:

- Using outdated default grids with modern functionals

- Neglecting symmetry corrections in thermochemical calculations

- Misinterpreting low-frequency modes as genuine vibrations

- Applying U corrections only to metal atoms in oxides, ignoring oxygen p-orbitals

- Comparing total energies from calculations with different U values

How do I choose between different DFT functionals for my metal complex study?

Follow best-practice recommendation matrices that consider [7]:

- Target properties: Energies, structures, spectroscopy, reactivity

- Metal type: Transition metals, lanthanides, main group

- System size: Small complexes vs. extended surfaces

- Multi-level approaches: Combine different methods for optimal efficiency/accuracy balance

My geometry optimization with neural network functionals (like DM21) shows oscillatory behavior. Why?

Neural network XC functionals can exhibit non-smooth behavior when calculating derivatives of exchange-correlation energy [5]. This causes oscillations in gradients affecting geometry optimization. Solutions include:

- Using traditional functionals for initial geometry optimization

- Implementing specialized smoothing algorithms

- Ensuring your system resembles training data composition [5]

When should I use DFT+U versus standard DFT for transition metal complexes?

- Studying metal oxides or strongly correlated systems

- Standard DFT produces qualitatively wrong electronic structures (e.g., metallic instead of insulating)

- Dealing with localized d or f electrons showing excessive delocalization error

- You need accurate band gaps for spectroscopic predictions

How can I efficiently determine optimal U values for new metal oxides?

Combine high-throughput DFT+U screening with machine learning [3]:

- Calculate band gaps and lattice parameters across (Up, Ud/f) parameter space

- Identify pairs that best match experimental values

- Train simple supervised ML models on these results

- Use ML predictions to guide calculations for related materials

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: When should I avoid using the B3LYP functional for transition metal complexes? B3LYP should be used with caution, or avoided, for several specific properties of transition metal complexes. It is known to overestimate metal-ligand bond lengths in lanthanide(III) complexes [8] and tends to overstabilize the high-spin state in open-shell 3d transition metal complexes, which can lead to incorrect spin splitting energies or even the wrong ground state spin state altogether [9]. For reaction energies and magnetic exchange coupling constants (J), its performance is often surpassed by other functionals [10] [9].

Q2: What are the main advantages of range-separated hybrids like CAM-B3LYP and ωB97X? Range-separated hybrid functionals are particularly advantageous for calculating properties that involve long-range charge transfer, such as nonlinear optical properties and charge-transfer excitation energies [11] [12]. They improve upon standard hybrids by correctly incorporating exact Hartree-Fock exchange at long electron-electron distances, which mitigates the spurious electron self-interaction error that plagues many other functionals. This makes them a better choice for calculating excitation energies and first hyperpolarizabilities in metal alkynyl complexes [11].

Q3: My calculations involve excited states with charge transfer character. What functional should I use? For charge-transfer excited states, range-separated hybrids like CAM-B3LYP and ωB97X generally provide a more accurate description than standard hybrid functionals [12]. However, these can sometimes overestimate vertical excitation energies (VEEs). Recent benchmarks suggest that empirically tuned versions like CAMh-B3LYP and ωhPBE0, which have a reduced long-range HF exchange (adjusted to 50%), can significantly improve accuracy for biochromophore models [12]. Furthermore, for intramolecular charge transfer states, time-independent, orbital-optimized DFT calculations (ΔSCF) with the CAM-B3LYP functional have been shown to provide excellent accuracy, with absolute errors typically around 0.15 eV [13].

Q4: Are there any recommended meta-GGA functionals for geometry optimization of metal complexes? Yes, meta-GGA and hybrid meta-GGA functionals often show superior performance for geometry optimization. For lanthanide(III) complexes, the meta-GGA functionals TPSS and the hybrid meta-GGA TPSSh have been shown to outperform B3LYP, providing more accurate metal-ligand bond distances [8]. A recent 2025 benchmark on Mn(I) and Re(I) carbonyl complexes also highlighted TPSSh and r2SCAN as top-performing functionals that offer a reliable balance of accuracy and efficiency for structures, vibrational properties, and energetics [14].

Q5: How important are dispersion corrections for my DFT calculations on metal complexes? Dispersion corrections are crucial for many applications. They account for weak intermolecular forces that are not naturally captured by standard density functionals. Omitting them can lead to significant errors in calculated structures and energies, particularly for non-covalent interactions. The use of modern dispersion corrections, such as D3(BJ) or D4, is highly recommended, as they can dramatically improve the performance of even standard functionals like B3LYP [14].

Troubleshooting Common Functional-Related Problems

Inaccurate Magnetic Exchange Coupling Constants (J-values)

- Problem: Calculated magnetic exchange coupling constants (J) for di-nuclear first-row transition metal complexes do not agree with experimental data.

- Investigation: Check the amount of Hartree-Fock (HF) exchange in your functional. Standard hybrid functionals with fixed HF admixture may not be optimal for this property.

- Solution: Consider using range-separated hybrid functionals with a low fraction of short-range HF exchange and no long-range HF exchange. The HSE family of functionals has been shown to perform better than B3LYP for this task [10]. Avoid the M11 Minnesota functional, which has been identified as giving high errors for J-value calculations [10].

Overestimation of Metal-Ligand Bond Lengths

- Problem: Geometry optimizations for lanthanide(III) complexes yield metal-ligand bonds that are noticeably longer than experimental or high-level computational benchmarks.

- Investigation: Verify the functional class. Standard hybrid-GGA functionals like B3LYP are known to cause this overestimation [8].

- Solution: Switch to a meta-GGA (e.g., TPSS) or a hybrid meta-GGA (e.g., TPSSh) functional for geometry optimization [8]. Additionally, ensure you are using an appropriate basis set (e.g., 6-31G(d), 6-311G(d,p), or cc-pVDZ for ligands) and consider the impact of the solvent environment using an implicit solvation model like IEFPCM, as this can significantly affect metal-nitrogen distances [8].

- Problem: TDDFT calculations severely underestimate or overestimate excitation energies for states with clear charge-transfer character.

- Investigation: Identify the charge-transfer character of the excited state and note the functional used. Standard hybrid functionals like B3LYP are notorious for underestimating charge-transfer excitation energies, while some range-separated hybrids may overcorrect and overestimate them [12].

- Solution: Employ a range-separated hybrid functional. If systematic overestimation persists with functionals like CAM-B3LYP or ωPBEh, consider using a modified functional with a lower fraction of long-range HF exchange (e.g., CAMh-B3LYP or ωhPBE0) [12]. For high-accuracy studies of intramolecular charge transfer, explore orbital-optimized DFT (ΔSCF) approaches with the CAM-B3LYP functional [13].

Failure of Self-Consistent Field (SCF) Convergence

- Problem: The SCF procedure fails to converge for a transition metal system, especially when using a novel functional.

- Investigation: This is a common issue, particularly with some machine-learned functionals like DM21 when applied to transition metal chemistry, but it can occur with any functional for challenging systems [15].

- Solution: Implement a graduated SCF convergence strategy:

- Strategy A: Use a level shift of 0.25 and a damping factor of 0.7.

- Strategy B: If A fails, increase the damping factor to 0.85.

- Strategy C: If B fails, increase the damping factor further to 0.92 [15]. For persistent cases, direct orbital optimization algorithms may be required, though they are not guaranteed to work [15].

Functional Performance Tables

Table 1: Performance of Select Density Functionals for Various Properties in Metal Complexes

| Functional | Class | Geometry Optimization | Magnetic Coupling (J) | Excitation Energies | NMR Chemical Shifts | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B3LYP | Hybrid GGA | Overestimates Ln-L bonds [8] | Moderate performance [10] | Underestimates CT states [12] | Performance varies with system [16] | Often a default; requires dispersion correction [9] |

| PBE0 | Hybrid GGA | Good for square-planar complexes [16] | Information Missing | Good for valence states [12] | Good with relativistic 2c approach [16] | A robust alternative to B3LYP |

| TPSSh | Hybrid Meta-GGA | Excellent for Ln & carbonyl complexes [8] [14] | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing | Top performer for structures; good accuracy/efficiency balance [14] |

| CAM-B3LYP | Range-Separated Hybrid | Information Missing | Information Missing | Good for CT states; can overestimate [12] | Information Missing | Recommended for charge-transfer and nonlinear optics [11] |

| ωB97X-D | Range-Separated Hybrid | Information Missing | Information Missing | Good performance [12] | Information Missing | Includes dispersion; good for excited states [12] |

| M06-2X | Hybrid Meta-GGA | Information Missing | Information Missing | Good accuracy [12] | Information Missing | High HF exchange; good for main-group thermochemistry |

Table 2: Benchmarking Results for Magnetic Exchange Coupling (Mean Absolute Error, cm⁻¹) [10]

| Functional | Type | MAE (cm⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|

| HSE06 | Range-Separated (Screened) | ~100 (Best performer) |

| B3LYP | Hybrid | ~150 |

| M11 | Range-Separated | >200 (Worst performer) |

Note: Lower MAE is better. Data adapted from benchmark on 11 di-nuclear Cu and V complexes.

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol: Benchmarking Functional Performance for Geometry Optimization

This protocol is adapted from studies assessing geometries of lanthanide complexes and metal carbonyls [8] [14].

- System Preparation: Select a set of 5-10 model complexes with high-quality experimental crystal structures (e.g., from the Cambridge Structural Database, CCDC).

- Computational Setup:

- Software: Use a standard quantum chemistry package (e.g., Gaussian, ORCA).

- Methodology: Test a panel of density functionals spanning different rungs of Jacob's Ladder. Include at least:

- A standard hybrid (e.g., B3LYP)

- A meta-GGA (e.g., TPSS)

- A hybrid meta-GGA (e.g., TPSSh, M06)

- A range-separated hybrid (e.g., CAM-B3LYP, ωB97X)

- Basis Sets: Use a consistent, medium-to-large basis set for all atoms (e.g., def2-TZVP for ligands; appropriate RECPs for metals).

- Dispersion: Apply consistent dispersion corrections (e.g., D3(BJ)) for all functionals.

- Solvation: Include an implicit solvation model (e.g., IEFPCM) if comparing to solution-phase data or structures.

- Execution: Perform full geometry optimizations for all model systems with each functional.

- Analysis: Calculate the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of key metal-ligand bond lengths and angles compared to the experimental reference structures. The functional yielding the lowest RMSD is the most accurate for your specific class of complexes.

Protocol: Calculating Magnetic Exchange Coupling Constants (J)

This protocol follows the methodology used to benchmark functionals for di-nuclear complexes [10].

- Structure Preparation: Obtain or optimize the molecular structure of the di-nuclear complex. It is recommended to reoptimize crystal structures computationally for consistency.

- Electronic Structure Calculation: Perform single-point energy calculations on the optimized structure for both the high-spin and broken-symmetry (BS) spin states.

- J-Value Calculation: Use the calculated energies in the Yamaguchi equation to compute the magnetic exchange coupling constant (J): J = (E_BS - E_HS) / [〈S²〉_HS - 〈S²〉_BS] where EBS and EHS are the energies of the broken-symmetry and high-spin states, respectively, and 〈S²〉 is the expectation value of the total spin angular momentum squared.

- Benchmarking: Compare the calculated J-values against experimental data. Functionals like the Scuserian HSE functionals, which have moderately low short-range HF exchange, have been shown to perform well in these benchmarks [10].

DFT Functional Selection Workflow for Metal Complexes

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational "Reagents" for DFT Studies of Metal Complexes

| Item | Function / Description | Example Choices |

|---|---|---|

| Core Functionals | Defines the exchange-correlation energy; primary determinant of accuracy. | B3LYP, PBE0, TPSSh, CAM-B3LYP, ωB97X-D [10] [8] [12] |

| Dispersion Corrections | Empirically accounts for long-range van der Waals interactions. | D3(BJ), D4 [14] |

| Relativistic Effective Core Potentials (RECPs) | Models core electrons for heavy atoms, incorporating relativistic effects. | Small-Core (SC) vs. Large-Core (LC) RECPs for Ln/Actinides [8] |

| Basis Sets | Set of mathematical functions to represent molecular orbitals. | def2-TZVP, 6-311G(d,p), cc-pVDZ; with diffuse fns for hyperpolarizabilities [11] [16] |

| Solvation Models | Approximates the effect of a solvent environment on the solute. | IEFPCM, SMD [8] |

| Relativistic Hamiltonians | Treats relativistic effects, crucial for heavy elements. | ZORA, DKH2, 4-Component [16] |

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What does the notation for basis sets like 6-31G* or def2-TZVP actually mean?

The notation describes the structure and quality of the basis set. For example, in 6-31G*, the "6-31G" indicates it is a split-valence double-zeta basis set, and the asterisk * signifies the addition of d-type polarization functions on heavy atoms (non-hydrogen) [17]. The def2-TZVP notation indicates a triple-zeta valence polarized basis set from the "def2" (default) family, which is systematically designed for high accuracy across the periodic table [18] [19].

2. My calculation with a large basis set is failing to converge. What should I do? SCF convergence failures with large, diffuse basis sets are often caused by linear dependencies in the basis. You can try the following troubleshooting steps:

- Use a smaller basis set for initial geometry optimizations: Optimize your molecular structure with a medium-sized basis set like

def2-SVPfirst, then use the optimized geometry for a single-point energy calculation with the largerdef2-TZVPbasis [19]. - Increase integration grid size: In DFT calculations, using a larger integration grid (e.g.,

Grid4orGrid5in ORCA) can improve stability [20]. - Apply a level shift: Applying a small level shift (e.g., 0.10 Hartree) can help accelerate SCF convergence [21].

3. How significant is Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE) for transition metal clusters, and how can I correct for it? BSSE can be a major source of error in calculating binding energies for transition metal clusters like copper. All-electron calculations on even moderate-sized clusters can have significant BSSE. The recommended solution is to use effective core potentials (ECPs) with a carefully chosen basis set, which reduces the number of basis functions and mitigates BSSE [22]. For accurate binding energies, the counterpoise correction method should be applied [22].

4. Is a double-zeta basis set ever sufficient for publication-quality results?

Double-zeta basis sets like 6-31G* or def2-SVP can be useful for initial geometry optimizations of organic and main-group systems and may provide reasonable structures [19]. However, for final energies and molecular properties (especially with post-HF methods), they are generally not sufficient and can introduce sizable errors [19] [21]. The community often recommends at least triple-zeta quality for results reasonably close to the basis set limit [21]. Specially optimized double-zeta basis sets like vDZP can, however, offer accuracy接近 (close to) triple-zeta levels for certain DFT functionals while remaining computationally efficient [21].

5. What is an "auxiliary basis set," and when do I need to specify one?

Auxiliary basis sets are used in Resolution of the Identity (RI) or Density Fitting (DF) approximations to significantly speed up the computation of two-electron integrals [18] [23]. They approximate products of atomic orbital basis functions. You must specify a matching auxiliary basis set when you use RI approximations in your calculations (e.g., def2/J for the RI-J approximation in ORCA) [18]. Using the correct auxiliary basis is crucial for maintaining accuracy while gaining a substantial computational speed-up.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Unacceptable Errors in Target Properties

- Symptoms: Calculated energies (e.g., binding energies, reaction barriers) or properties (e.g., hyperfine coupling constants) deviate significantly from experimental or high-level benchmark values.

- Potential Cause: Basis set incompleteness error (BSIE) – The basis set is too small to accurately describe the electron density.

- Solution:

- Systematically increase basis set size: Conduct a basis set convergence study. For example, progress from

def2-SVP→def2-TZVP→def2-QZVP[19]. - Use a balanced, polarized basis: Ensure your basis set includes polarization (d, f) and, if needed, diffuse functions. For properties like hyperfine coupling, specialized basis sets (e.g.,

EPR-II,EPR-III) are optimized for accuracy [17] [20]. - Consider modern alternatives: For DFT, the

vDZPbasis set can be an efficient alternative to conventional double-zeta basis sets, offering accuracy closer to triple-zeta levels for many functionals without the full computational cost [21].

- Systematically increase basis set size: Conduct a basis set convergence study. For example, progress from

Problem 2: Inaccurate Binding Energies for Metal Complexes

- Symptoms: Overly large or nonsensical binding energies in metal clusters or complexes.

- Potential Cause: Basis set superposition error (BSSE) – Fragments artificially "borrow" basis functions from neighboring atoms, overstating the stability of the complex. This is a critical issue for transition metal systems [22].

- Solution:

- Apply the counterpoise correction: This method corrects for BSSE by recalculating the monomer energies in the full basis set of the complex [22].

- Use pseudopotentials: For transition metals, replacing core electrons with an Effective Core Potential (ECP) like those in

SDDorLanL2DZbasis sets can dramatically reduce BSSE [17] [22].

Problem 3: Prohibitively Long Computation Times

- Symptoms: Calculations with desired methods and triple-zeta basis sets are too slow for the system size or project timeline.

- Potential Cause: The computational cost of a method often scales poorly with basis set size (e.g., O(N⁴) for HF).

- Solution:

- Employ RI approximations: Use the Resolution of the Identity (RI) technique for methods like DFT (RI-J, RI-JK) and MP2 (RI-MP2). This requires specifying an appropriate auxiliary basis set (e.g.,

def2/Jfor RI-J in ORCA), which can speed up calculations by a factor of 5-10 without significant accuracy loss [18] [23]. - Use a mixed-basis set approach: Apply a larger basis set (e.g.,

def2-TZVP) only to the atoms central to your investigation (e.g., the metal center in a complex) and a smaller basis set (e.g.,def2-SVP) to the surrounding ligands [19]. - Leverage efficient modern basis sets: Consider using the

vDZPbasis set, which is designed for computational efficiency while minimizing BSSE, offering a good balance for many DFT functionals [21].

- Employ RI approximations: Use the Resolution of the Identity (RI) technique for methods like DFT (RI-J, RI-JK) and MP2 (RI-MP2). This requires specifying an appropriate auxiliary basis set (e.g.,

Basis Set Comparison and Selection Protocol

The table below summarizes common basis sets and their typical use cases to help you make an informed selection.

Table 1: Guide to Common Gaussian-Type Orbital Basis Sets

| Basis Set | Zeta (ζ) Quality | Key Features | Recommended Use Cases | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STO-3G [17] | Minimal | Minimal number of functions; poor flexibility. | Quick preliminary tests on very large systems; not for final results. | Very Low |

| 6-31G* / def2-SVP [17] [19] | Double-Zeta | Split-valence; adds polarization functions. | Initial geometry optimizations; large systems where cost is prohibitive. | Low |

| vDZP [21] | Double-Zeta (Optimized) | Designed for low BSSE; uses ECPs; molecularly optimized. | Efficient and relatively accurate DFT calculations for main-group thermochemistry. | Low |

| 6-311G / def2-TZVP [17] [19] | Triple-Zeta | Higher flexibility in valence region; multiple polarization functions. | Default for most publication-quality DFT single-point energies, optimizations, and frequencies. | Medium |

| def2-QZVP [19] | Quadruple-Zeta | Approaches the basis set limit for many properties. | High-accuracy studies; benchmarking. | High |

| cc-pVXZ (X=D,T,Q,5) [17] | Correlation-Consistent | Systematically designed for post-HF (wavefunction) methods. | Gold standard for MP2, CCSD(T), and other correlated calculations. | Medium to Very High |

| SDD / LanL2DZ [17] | ECP + DZ | Uses Effective Core Potentials for heavier elements. | Calculations on atoms from the 3rd period and beyond (e.g., transition metals). | Low to Medium |

Experimental Protocol: Performing a Basis Set Convergence Study

To ensure your results are converged with respect to the basis set, follow this methodology:

- Geometry Optimization: Optimize the molecular geometry of your system using a medium-quality, polarized basis set like

def2-SVP[20]. - Single-Point Energy Calculations: Using the optimized geometry from Step 1, perform a series of single-point energy calculations with progressively larger basis sets. A standard path is:

def2-SVP→def2-TZVP→def2-QZVP- For wavefunction methods:

cc-pVDZ→cc-pVTZ→cc-pVQZ

- Analysis: Plot the property of interest (e.g., total energy, reaction energy, HFC) against the basis set level. The property is considered converged when the change from one level to the next is smaller than your desired accuracy threshold (e.g., 1 kJ/mol for energies).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational "Reagents" for DFT Studies of Metal Complexes

| Item / Keyword | Function / Description | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

| def2-TZVP [19] [20] | A balanced triple-zeta valence polarized basis set offering high accuracy for geometry and energy calculations on a wide range of elements. | Default orbital basis for production calculations on metal complexes. |

| def2/J & def2-TZVP/C [18] | Auxiliary basis sets for the RI approximation, used to accelerate Coulomb (J) and correlation energy calculations, respectively. | ! RI-J PBEO def2-TZVP def2/J ! RI-MP2 def2-TZVP def2-TZVP/C |

| Effective Core Potential (ECP) [17] [22] | Replaces core electrons with a potential, reducing computational cost and BSSE for heavy elements (e.g., transition metals). | Using the SDD basis set for a copper complex. |

| Counterpoise Correction [22] | A computational procedure to correct for Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE) in interaction energy calculations. | Correcting the binding energy of a substrate to a metal center. |

| Dispersion Correction (e.g., D3, D4) [21] | Adds empirical van der Waals interactions, which are often missing in standard DFT functionals but critical for non-covalent interactions. | ! B3LYP def2-TZVP D3 |

Workflow for Basis Set Selection

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow for selecting an appropriate basis set for your study on metal complexes, balancing accuracy and computational cost.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: How can I quickly determine if my metal complex is a single-reference or multi-reference system before running extensive calculations?

Perform an initial diagnostic check using qualitative chemical insight and low-cost computational methods. Systems with open-shell singlet states, metal centers in high-symmetry environments, or potential diradical character should be flagged as potential multi-reference systems. The benchmark study recommends using diagnostic calculations like 〈S²〉 evaluation and fractional occupation analysis to identify multi-reference character early in the research workflow [24].

FAQ 2: What are the practical consequences of misclassifying a multi-reference system as single-reference in DFT studies?

Misclassification leads to significant errors in predicting electronic properties, including spin-state energetics, redox potentials, and reaction barriers [24]. For the 40 multireference diradicals in the benchmark database, standard DFT functionals without proper multireference treatment produced inaccurate spin-flip gaps, potentially leading to incorrect conclusions about material properties and reactivity [24].

FAQ 3: Which computational methods provide reliable results for multireference systems when standard DFT fails?

For systems with confirmed multireference character, hierarchically correlated orbital functional theory (HCOFT) has shown excellent accuracy. Specifically, 1-HCOFT demonstrated remarkable performance for singlet diradicals with low basis set dependence, maintaining accuracy even with increasing system size [24]. MS-CASPT2 methods also provide reliable reference values for benchmark systems [24].

FAQ 4: What quantitative thresholds indicate strong multi-reference character in transition metal complexes?

While system-dependent, these computational indicators suggest significant multi-reference character:

Table: Quantitative Indicators of Multi-reference Character

| Diagnostic Metric | Threshold for Multi-reference Character | Computational Method |

|---|---|---|

| 〈S²〉 for singlet state | Significantly > 0 | DFT/TD-DFT |

| Spin-flip gap deviation | > 0.26 V RMSE from reference | ΔDFT with standard functionals |

| Fractional occupation | Natural orbital occupation deviating significantly from 2 or 0 | Natural Bond Orbital analysis |

FAQ 5: How does the choice of functional impact accuracy for single-reference versus multi-reference systems in spin-flip gap calculations?

For the single-reference subset (SFG-SR) containing 379 vertical gaps, hybrid functionals with carefully tuned Hartree-Fock exchange significantly outperformed semilocal functionals [24]. However, for the multireference subset (SFG-MR), only methods specifically designed for strong correlation, like 1-HCOFT, provided accurate results, as standard functionals failed regardless of Hartree-Fock exchange percentage [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent spin-state energetics in iron complex calculations

Symptoms: Large variation in predicted ground states depending on functional choice, unphysical spin contamination (〈S²〉 significantly deviating from expected values).

Solution Protocol:

- Run diagnostic calculations to quantify multi-reference character using 〈S²〉 expectation values and natural orbital occupation numbers [24].

- For confirmed multi-reference systems, implement strong-correlation methods: Begin with 1-HCOFT calculations for initial assessment [24].

- Validate with benchmark data by comparing your system's characteristics to the 419 vertical gaps in the SFG database [24].

- Select appropriate functional based on system character: Use optimized hybrid functionals for single-reference systems and specialized multireference methods for diradicals or open-shell singlets [24].

Experimental Protocol: Spin-Flip Gap Calculation Workflow

Problem: Poor prediction accuracy for redox potentials in iron complexes

Symptoms: Calculated redox potentials deviate significantly from experimental values, poor correlation across a series of related complexes.

Solution Protocol:

- Verify system character using the same diagnostic approach as for spin-state problems [24].

- For single-reference systems, apply the combined tight-binding DFT/standard DFT approach that achieved accurate redox potential prediction for 2,267 iron complexes [25].

- Implement graph neural network correction using the GNN framework that reduced errors to 0.26 V RMSE for redox potential prediction [25].

- Analyze ligand influence by examining how different ligand classes and local iron coordination environments systematically affect redox potential [25].

Experimental Protocol: Redox Potential Prediction Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for Reference Character Assessment

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| SFG Benchmark Database | Reference dataset of 419 vertical spin-flip gaps | Validation of computational methods for both single-reference (SFG-SR) and multi-reference (SFG-MR) systems [24] |

| 1-HCOFT Method | Hierarchically correlated orbital functional theory | Accurate treatment of multireference systems like diradicals with low basis set dependence [24] |

| ΔDFT with Optimized Hybrid Functionals | Energy difference approach with tuned Hartree-Fock exchange | Practical and accurate strategy for spin-flip gap prediction in single-reference systems [24] |

| GNN Framework for Redox Prediction | Graph neural network with automated graph generation | State-of-the-art prediction of redox potentials for iron complexes (0.26 V RMSE) [25] |

| Iron Complex Redox Dataset | Curated dataset of 2,267 iron complexes | Machine learning applications and understanding ligand influence on redox properties [25] |

Diagnostic Reference Tables

Table: Method Performance Across System Types

| Computational Method | Single-Reference Systems | Multi-Reference Systems | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Hybrid DFT | Excellent (with tuning) | Poor | Initial screening of single-reference systems |

| 1-HCOFT | Good | Excellent | Confirmed multireference systems [24] |

| ΔDFT Approach | Excellent | Limited | Spin-flip gaps in single-reference systems [24] |

| GNN Prediction | Excellent for redox | System-dependent | Large-scale screening of redox properties [25] |

Incorporating Dispersion Corrections and Accounting for Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE)

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: Why is my DFT-optimized geometry for a metal complex or a flexible organic molecule significantly different when I use a dispersion correction?

Dispersion corrections are essential for accurately modeling intermolecular and intramolecular non-covalent interactions. Standard local (LDA) or semi-local (GGA) functionals lack long-range correlation, which is the physical origin of dispersion (van der Waals) forces [26] [27]. Without these corrections, the minimal energy configuration for systems like layered materials (e.g., graphene) or flexible drug molecules may be incorrect, often resulting in unbound or overly separated fragments [26] [28]. When you apply a dispersion correction, it adds an empirical attraction that can drastically alter the optimized geometry to one that is more physically realistic. For instance, in intramolecular systems, dispersion corrections are crucial for accurately modeling the conformations of "soft" or long, flexible molecules where middle-to-long range correlation effects are significant [28]. Benchmark studies have confirmed that modern dispersion corrections like D3(BJ) significantly improve the accuracy of geometries for organic molecules and metal-containing complexes [28] [29].

FAQ 2: My binding or adsorption energy seems too favorable. Could this be an artifact, and how can I correct for it?

An artificially high binding affinity is a classic symptom of the Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE). In layered systems or molecule-surface interactions, BSSE creates an artificial attraction that can partly compensate for the lack of van der Waals forces, leading to underestimated bond distances or overestimated binding energies if left uncorrected [26]. BSSE arises from the incompleteness of the localized basis set; when two subunits (A and B) approach each other, the basis functions on one fragment become available to describe the other, artificially lowering the energy of the combined system [26] [30]. To remove this error, you must use the counterpoise (CP) correction protocol [26]. The corrected binding energy is calculated as:

- Ebinding(CP) = EAB(AB) - [EA(A~B~) + EB(~AB)]

- EAB(AB): Energy of the total complex

ABcalculated with its full basis set. - EA(A~B~): Energy of fragment

Acalculated in the presence of the ghost atoms of fragmentB(meaningB's basis functions are present at its positions, butBhas no nuclear charge or electrons). - E_B(~AB): Energy of fragment

Bcalculated in the presence of the ghost atoms of fragmentA[26] [30].

- EAB(AB): Energy of the total complex

FAQ 3: Which dispersion correction method should I use for my system containing metal complexes?

The choice of dispersion method can depend on your system's composition. Large-scale benchmarking on nearly 15,000 molecular complexes revealed that for most neutral systems, popular methods like XDM, D3BJ, D4, MBD, and MBD-NL perform similarly well [31]. However, critical differences emerge for specific cases. The study recommends caution when using MBD-based methods (MBD, MBD-NL) for complexes involving organic species and alkali or alkaline earth metal cations (e.g., modeling Li+ intercalation), as they can exhibit significant overbinding at compressed geometries [31]. For general use, including with platinum complexes, a method like PBE0-D3(BJ) has been identified as a top performer for geometry optimization [29]. Always test the sensitivity of your results to the choice of dispersion model, especially when working with charged species.

FAQ 4: How do I technically implement a counterpoise correction for a dimer system in a quantum chemistry code?

The general workflow involves using ghost atoms. These atoms carry the basis set (and potentially the numerical grid) of the original atom but possess zero nuclear charge and zero mass [32] [30]. The specific implementation can vary between software (e.g., DIRAC, ADF, Q-Chem), but the core principles are consistent:

- Identify Fragments: Define your system as two distinct fragments, A and B.

- Calculate E_AB(AB): Run a standard single-point energy (or geometry optimization) calculation on the full dimer

AB. - Calculate E_A(A~B~): Run a calculation for fragment

Ain the exact geometry it has in the dimer. The atoms of fragmentBare included in the input as ghost atoms with their full basis set. - Calculate E_B(~AB): Run a calculation for fragment

Bin the exact geometry it has in the dimer, with the atoms of fragmentAincluded as ghost atoms. - Compute the Corrected Energy: Use the three energies obtained in steps 2-4 in the counterpoise formula above to find the BSSE-corrected binding energy [32] [26].

Pitfall Alert: When using ghost atoms in DFT, ensure the numerical grid is consistent between the dimer and monomer-plus-ghost calculations to avoid errors. This may require manually importing the grid from the dimer calculation [32].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Geometry optimization of a molecule (e.g., BQR or Y6) curves unexpectedly when dispersion correction is enabled.

- Description: Without dispersion, the molecule optimizes to a linear/planar structure, but with Grimme's D3 correction, it adopts a curved (C-shaped) geometry [33].

- Diagnosis: The potential energy surface for the bending mode is very flat. Small differences in the treatment of mid-range dispersion by different functionals and damping functions can tip the balance between a linear and a curved minimum [33] [28].

- Solution Steps:

- Verify the Result: Perform a frequency calculation on the optimized curved structure. If the Hessian has many low or negative frequencies, the surface is flat, and the result may be sensitive to the computational setup [33].

- Test Alternative Dispersion Models:

- Use a Non-Empirical Functional: Try a functional like wB97X-V that is designed without an empirical dispersion correction and incorporates non-local correlation [33].

- Cross-Validate: Compare the results against a higher-level theory or experimental data (e.g., crystal structures) if available.

Problem: Unphysically high binding energy or too short intermolecular distance in a complex.

- Description: The calculated interaction between a drug molecule and a biopolymer (or between two graphene layers) is stronger than expected, with an underestimated equilibrium separation [26].

- Diagnosis: This is likely due to the combined or separate effects of missing dispersion corrections and uncorrected BSSE [26].

- Solution Steps:

- Apply a Dispersion Correction: Ensure a modern dispersion correction (e.g., D3(BJ)) is active in your calculation [34].

- Apply the Counterpoise Correction: Follow the ghost atom protocol outlined in the FAQs to calculate the BSSE and subtract it from your raw binding energy [26].

- Use a Larger Basis Set: BSSE decreases with larger, more complete basis sets. If computationally feasible, repeat the calculation with a triple-zeta basis set to minimize the inherent error.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Benchmarking DFT Methods for Geometry Optimization of Metal Complexes

This protocol is adapted from a systematic assessment of platinum complexes [29].

- System Preparation: Select a training set of well-characterized metal complexes (e.g., 14 Pt complexes with varying sizes, oxidation states, and ligands).

- Methodology Selection: Choose a range of methods to test:

- Functionals: BP86, PBE, B3LYP, PBE0, TPSSh.

- Basis Sets: def2-SVP, def2-TZVP, etc., for ligands; effective core potentials or all-electron relativistic methods for the metal.

- Dispersion Corrections: D3(BJ), TS-vdW, etc.

- Solvation Models: COSMO, SMD, PCM.

- Geometry Optimization: Perform a full geometry optimization for each complex using every method combination.

- Validation: Compare the optimized metrical parameters (bond lengths, angles) against reliable experimental reference data (e.g., X-ray crystal structures, EXAFS data).

- Analysis: Identify the best-performing method by calculating the mean absolute error (MAE) and root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) for the geometric parameters. The study found PBE0-D3(BJ)/def2-TZVP with ZORA and solvation to be optimal for Pt complexes [29].

Quantitative Comparison of Dispersion Correction Methods

The following table summarizes key findings from a large-scale benchmark of dispersion corrections on the DES15K database [31].

Table 1: Performance of Various Dispersion Corrections with the PBE0 Functional

| Dispersion Method | Recommended For | Performance Notes | Cautions |

|---|---|---|---|

| D3(BJ) | General use, neutral molecular complexes | Excellent performance for neutral systems; widely used and reliable. | Performance degrades for ionic complexes, but this is often a functional issue. |

| D4 | General use, neutral molecular complexes | Performance on par with D3(BJ). | Performance degrades for ionic complexes. |

| XDM | General use, neutral molecular complexes | Performance on par with D3(BJ) and D4. | Performance degrades for ionic complexes. |

| MBD/MBD-NL | Systems with strong many-body dispersion effects | Good performance for many neutral systems. | Not recommended for complexes with alkali/alkaline earth metal cations (e.g., Li+-graphite); can overbind significantly. |

| TS | N/A | Not the top performer in the DES15K benchmark [31]. | - |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Computational Reagents for Dispersion-Corrected DFT Studies

| Item / Method | Function | Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| Grimme's DFT-D3 | Adds a semi-empirical, atom-pairwise dispersion energy correction to the DFT total energy. | Correcting for missing van der Waals interactions in the adsorption of a drug (Bezafibrate) on a biopolymer (Pectin) [34]. |

| Becke-Johnson Damping (BJ) | A damping function used with D3 to improve accuracy for mid-range and short-range interactions. | Used with B3LYP for a more accurate description of hydrogen bonding and dispersion in drug-polymer complexes [34]. |

| Ghost Atoms | Atoms with basis sets but no nuclear charge or electrons, used to compute the BSSE. | Implementing the counterpoise correction for the binding energy of a helium dimer or graphene layers [32] [26]. |

| Polarizable Continuum Model (PCM) | Implicit solvation model to account for the effects of a solvent environment. | Modeling drug delivery in an aqueous biological environment [34]. |

| def2-TZVP Basis Set | A triple-zeta valence polarized basis set offering a good balance of accuracy and cost for geometry optimizations. | Identified as part of the optimal method for geometry optimization of platinum complexes [29]. |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow for deciding when and how to apply dispersion and BSSE corrections in a computational study.

Decision Workflow for Dispersion and BSSE

Practical Protocols: Calculating Structural, Electronic, and Reactivity Properties

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between an Ionic and a Variable Cell Relaxation?

An Ionic Relaxation (also called structural relaxation) optimizes the positions of atoms within a fixed, user-defined unit cell. The goal is to find the atomic configuration that minimizes the total energy, resulting in inter-atomic forces that are close to zero [35]. In contrast, a Variable Cell Relaxation (or cell relaxation) optimizes both the atomic positions and the dimensions (and potentially shape) of the unit cell itself. This process minimizes the enthalpy of the system to find the equilibrium structure where both the internal forces and the stress tensor components are negligible [35].

Q2: For my metal complex, should I use the experimental lattice parameters or perform a full Variable Cell Relaxation?

For a consistent computational study, performing a full Variable Cell Relaxation is generally recommended. While experimental lattice parameters are valuable, they do not necessarily represent the global minimum on the Density Functional Theory (DFT) potential energy surface [36]. Using a structure fully relaxed with your chosen computational protocol (functional, pseudopotential, etc.) ensures internal consistency for subsequent property calculations, such as phonon spectra or mechanical properties [36]. Using fixed experimental lattice constants can introduce non-negligible external pressure in the calculation, potentially leading to unreliable results for properties other than the band structure [36].

Q3: My geometry optimization is not converging. What are the key parameters to check?

You should investigate several key parameters, often related to the convergence criteria [37]:

- Check Convergence Thresholds: The standard convergence criteria might be too strict for your system. Consider using a lower

Qualitysetting (e.g.,BasicorNormal) for initial tests [37]. - Verify Maximum Iterations: Ensure the

MaxIterationslimit is not too low. The default is usually sufficient, but if your system is slow to converge, you may need to increase it [37]. - Assess Force Accuracy: Tight convergence criteria require highly accurate and noise-free forces from the underlying electronic structure calculation. For some computational engines, you may need to increase their numerical accuracy (e.g., plane-wave cutoff, k-point grid) to provide sufficiently precise gradients for the geometry optimizer [37].

Q4: My optimization converged to a saddle point (transition state) instead of a minimum. What can I do?

Some software packages offer an automatic restart feature for this specific issue. If the optimization converges to a transition state (indicated by an imaginary vibrational frequency), the calculation can be automatically restarted from a geometry slightly displaced along the softest mode. To use this, you typically need to:

- Enable PES (Potential Energy Surface) point characterization in the properties block.

- Set the maximum number of restarts (

MaxRestarts) to a value greater than zero. - Ensure that crystal symmetry is disabled (

UseSymmetry False), as the displacement often breaks symmetry [37].

Q5: When should I consider using constrained relaxation?

Constrained relaxation is a valuable strategy for large systems or specific scientific questions [35] [38]:

- Large Structures: For large metal complexes or supercells, a full relaxation of all atomic positions and cell parameters can be computationally prohibitive. In such cases, you can fix the cell size and shape and only relax the atomic positions [35].

- Targeted Studies: If you are modeling a single defect in a large supercell, you can significantly reduce computation time by fixing the positions of atoms beyond the 2nd nearest neighbors of the defect atom and only relaxing a local cluster [35].

- Simulating Specific Conditions: Constraints can be used to fix certain cell parameters (e.g., volume or shape) to simulate specific experimental conditions like uniaxial strain [38].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Optimization is Very Slow or Stagnates

- Potential Cause 1: Poor conditioning of the Hessian matrix for variable cell relaxations.

- Solution: Advanced optimizers use coordinate transformations to improve conditioning. Ensure you are using a modern algorithm designed for variable cell shape optimization [39].

- Potential Cause 2: The initial geometry is far from the minimum, or the system has a complex, "soft" potential energy surface.

- Solution:

- Loosen the convergence criteria (

Convergence%Quality Basic) for a preliminary optimization [37]. - Restart the optimization from the preliminary result using tighter criteria.

- For ionic relaxations, try a different optimization algorithm (e.g., FIRE or L-BFGS) which can be more efficient than conjugate gradients for certain systems [40].

- Loosen the convergence criteria (

- Solution:

- Potential Cause 3: Inaccurate forces due to under-converged electronic structure parameters.

- Solution: Increase the numerical quality in the electronic structure calculation (e.g.,

ecutwfc/ecutrhoin Quantum ESPRESSO,NumericalQualityin BAND) to provide more precise gradients to the geometry optimizer [37].

- Solution: Increase the numerical quality in the electronic structure calculation (e.g.,

Problem: Optimization Finished but Lattice Parameters are Inaccurate

- Potential Cause 1: The stress tensor convergence criterion was too loose.

- Solution: Tighten the stress convergence threshold. The

StressEnergyPerAtomparameter controls this; a smaller value leads to stricter convergence [37].

- Solution: Tighten the stress convergence threshold. The

- Potential Cause 2: The plane-wave basis set became inadequate after significant cell expansion.

- Solution: Use the

dilatmxkeyword (or equivalent) to book extra memory for the basis set to accommodate cell expansion during the relaxation process. For accurate results, a two-step process is recommended: a first run withchkdilatmx=0to get a better-but-inaccurate geometry, followed by a second, more accurate run from that geometry withchkdilatmx=1and adilatmxof about 1.05 [41].

- Solution: Use the

Problem: "Out of Memory" Error During Variable Cell Relaxation

- Potential Cause: The

dilatmxparameter is set too high, leading to an enormous plane-wave basis set.- Solution: The

dilatmxparameter directly controls the scaling of the plane-wave cutoff to account for cell expansion. A large value wastes CPU time and memory [41]. Use the two-step procedure mentioned above to find a suitable value without over-allocating resources.

- Solution: The

Convergence Criteria and Workflow Comparison

Table 1: Standard convergence quality settings for geometry optimization in the AMS package. The "Normal" profile is typically a good starting point [37].

| Quality Setting | Energy (Ha/atom) | Gradients (Ha/Å) | Step (Å) | Stress Energy Per Atom (Ha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VeryBasic | 10⁻³ | 10⁻¹ | 1 | 5×10⁻² |

| Basic | 10⁻⁴ | 10⁻² | 0.1 | 5×10⁻³ |

| Normal | 10⁻⁵ | 10⁻³ | 0.01 | 5×10⁻⁴ |

| Good | 10⁻⁶ | 10⁻⁴ | 0.001 | 5×10⁻⁵ |

| VeryGood | 10⁻⁷ | 10⁻⁵ | 0.0001 | 5×10⁻⁶ |

Table 2: Comparison of relaxation types and their typical use cases.

| Feature | Ionic Relaxation | Variable Cell Relaxation |

|---|---|---|

| Degrees of Freedom | Atomic positions only [35] | Atomic positions + Unit cell (vectors/angles) [35] |

| Target Quantity | Minimizes total energy [37] | Minimizes enthalpy (for given external pressure) [40] |

| Convergence Criteria | Forces on atoms, energy change, atomic step size [37] | Forces on atoms, energy change, stress tensor, cell step size [37] |

| Primary Use Case | Structure is known to be near equilibrium; finalizing atomic positions. | Finding the full equilibrium structure from an initial guess. |

| Computational Cost | Lower | Higher |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Variable-Cell Relaxation for a Metal Complex (using SSCHA/Quantum ESPRESSO as an example)

This protocol is adapted from a tutorial on variable cell relaxation of LaH₁₀ [42].

- Initial Structure Preparation: Obtain the initial crystal structure for your metal complex from a database or create it based on known symmetry.

- Calculator Setup: Configure the ab-initio calculator (e.g., Quantum ESPRESSO). Key parameters include:

- Pseudopotentials: Select appropriate pseudopotentials for the metal and ligand atoms.

- Wavefunction Cutoff (

ecutwfc): Set to a converged value (e.g., 35 Ry for preliminary tests). - Density Cutoff (

ecutrho): Typically 10xecutwfc. - k-point Grid: Choose a mesh that ensures Brillouin zone sampling is converged (e.g., 8x8x8 for a cubic cell).

- Other Parameters: Set energy convergence threshold (

conv_thr), smearing, and mixing parameters [42].

- Relaxation Object Configuration:

- Ensemble: Prepare an ensemble for the stochastic relaxation, specifying the initial dynamical matrix, temperature (T0 = 0 for ground state), and supercell.

- Minimizer: Set up the minimizer with steps for the dynamical matrix (

min_step_dyn) and structure (min_step_struc), and a meaningful factor for the stopping condition. - Relaxation Type: Choose the variable-cell relaxation method. You can perform a relaxation at fixed volume or with a target pressure [42].

relax.vc_relax(fix_volume=True, static_bulk_modulus=120)

- Execution and Monitoring: Run the relaxation. It is good practice to implement a custom function to monitor the space group symmetry after each minimization step to track structural evolution [42].

- Analysis: Upon convergence, analyze the final structure, energy, and stress.

Protocol 2: Two-Step Lattice Parameter Optimization (using ABINIT as an example)

This protocol is useful when the starting lattice parameters are poor or when dealing with large cell expansions [41].

- Step 1 - Inaccurate but Better Estimation:

- Set

chkdilatmx = 0to prevent the code from stopping if the cell expands beyond the initial basis set limit. - Set

dilatmxto a value larger than 1.0 (e.g., 1.15) to book a larger plane-wave basis. - Run the variable-cell relaxation. The resulting lattice parameters will be more accurate than the initial guess, but not fully converged with respect to the basis set.

- Set

- Step 2 - Accurate Refinement:

- Use the output structure from Step 1 as the new input.

- Set

chkdilatmx = 1(default) to enforce accurate rescaling. - Set

dilatmxto a value slightly above 1.0 (e.g., 1.05) to save computational resources. - Rerun the variable-cell relaxation. This will yield the final, accurate geometry.

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Decision workflow for choosing between ionic and variable-cell relaxation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Computational Reagents

Table 3: Key software and methodological "reagents" for geometry optimization workflows.

| Item | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| BFGS / L-BFGS | Quasi-Newton optimization algorithm for efficient convergence of ionic degrees of freedom [40] [38]. | Standard ionic relaxation of a molecular metal complex. |

| FIRE | Fast inertial relaxation engine; efficient quenched molecular dynamics algorithm [40]. | Relaxation of systems with rough potential energy surfaces. |

| Pfrommer et al. Method | A coordinate transformation that combines ionic and cell degrees of freedom into a single, well-conditioned vector for optimization [40]. | Robust variable-cell shape relaxation. |

| Conjugate Gradients (CG) | A widely used gradient-based minimization algorithm [40] [38]. | Cell parameter optimization and ionic steps in some codes. |

| SSCHA | Stochastic Self-Consistent Harmonic Approximation; used for quantum variable-cell relaxation including nuclear quantum effects [42]. | Accurate relaxation of high-pressure or quantum-anharmonic materials. |

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: My DFT calculation for a metal oxide composite fails to converge. What are the primary steps I should take? A failure to converge often relates to the complexity of the system's electronic structure or inappropriate initial geometry. For metal oxide composites like SiO₂/GO/Pb₃O₄/Bi₂O₃, follow this protocol [43]:

- Initial Geometry Check: Ensure your initial molecular model is chemically sensible. For composite structures, start by optimizing the geometry of smaller subunits before assembling the full model.

- SCF Procedure: Utilize the "stable" keyword in Gaussian 09 to check the stability of the wavefunction. If unstable, use a quadratic convergent SCF (QC) method or employ a larger integration grid (e.g.,

integral=ultrafine). - Convergence Criteria: The following criteria are recommended for geometry optimization [43]:

- Self-consistent field (SCF) energy convergence should be set to within 10⁻⁶ eV.

- The maximum force on atoms should be less than 10⁻⁴ eV/Å.

- The maximum displacement for atomic positions should be constrained to 10⁻³ Å.

FAQ 2: Which DFT functional and basis set are recommended for accurate HOMO-LUMO gap calculations in transition metal complexes? The choice depends on the specific metal and ligands. A reliable starting point is the B3LYP functional. For basis sets [43] [44]:

- For first-row transition metals (e.g., Fe²⁺, Ni²⁺, Cu²⁺, Zn²⁺), use an effective core potential (ECP) like LanL2DZ for the metal atom and 6-31+G(d,p) for light atoms (C, N, O, H) [44].

- For systems involving heavier metals (e.g., Pb, Bi) in composites, the SDD basis set is a reliable choice for all atoms [43].

- For purely organic systems like graphene oxide (GO) functionalized with benzoic acid, B3LYP/6-31g(d,p) provides a good balance of accuracy and efficiency [45].

FAQ 3: How can I calculate the Density of States (DOS) from my DFT calculation, and what software can I use? After obtaining the converged electronic structure from a software package like Gaussian 09, you can generate DOS plots. The general workflow is [43]:

- Perform a geometry optimization to find the ground-state structure.

- Run a frequency calculation to confirm a true minimum (no imaginary frequencies).

- Conduct a single-point energy calculation to obtain the detailed electronic eigenvalues.

- Use specialized software to project these eigenvalues onto a suitable energy range. Gauss Sum 3 is a recognized tool for generating these DOS plots [43]. The resulting curve visualizes the distribution of electronic states, showing occupied and unoccupied states.

FAQ 4: My calculated redox potentials do not match experimental values. What factors should I investigate? Discrepancies can arise from several sources:

- Solvation Model: Gas-phase calculations often differ significantly from experimental values measured in solution. Always include a solvation model, such as the Integral Equation Formalism Polarized Continuum Model (IEF-PCM), for redox potential calculations [44]. Select the appropriate solvent (e.g., water, DMF).

- Reference Electrode: Ensure you are using a consistent and correct thermodynamic cycle to reference your calculated energies to a standard electrode (e.g., SHE).

- Functional Limitations: Standard functionals like B3LYP can have systematic errors. Consider using hybrid meta-functionals or double-hybrid functionals for improved accuracy, though at a higher computational cost.

FAQ 5: Why were some articles on corannulene oligomers retracted, and what can I learn from this? A specific article on n-corannulene oligomers was retracted because an investigation found that numerous irrelevant citations were added to benefit the authors, and crucial data, specifically the Density of States (DOS) spectra, was stated to be in the supplemental data but was missing [46]. The lesson is to always scrutinize the data supporting a paper's conclusions, ensure all cited references are directly relevant, and maintain meticulous records of all computational data and analysis scripts.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Unrealistically Low HOMO-LUMO Bandgap A bandgap that seems too small or is zero for a system expected to be a semiconductor can indicate an incorrect electronic state or convergence error.

- Step 1: Verify Electronic State and Multiplicity Check if the calculation used the correct charge and spin multiplicity. An incorrect multiplicity can lead to a severely underestimated bandgap.

- Step 2: Perform a Stable Wavefunction Check

Use the

stablekeyword in Gaussian to ensure the solution is stable. If not, re-optimize the geometry using the stable wavefunction. - Step 3: Analyze the DOS Plot the Density of States (DOS) to confirm the HOMO-LUMO gap visually. The DOS for a composite like 3SiO₂/GO/Pb₃O₄/Bi₂O₃ should show unoccupied states emerging near the Fermi level, indicating a reduced but finite bandgap [43].

Issue: Unphysical Bonds or Geometry in Optimized Metal Complexes This often occurs due to inaccurate initial guesses or limitations of the chosen functional/basis set.

- Step 1: Re-initialize from a Better Structure Use crystallographic data or molecular mechanics to generate a more realistic starting geometry.

- Step 2: Verify Method Suitability Confirm that your chosen functional and basis set are appropriate for describing the metal-ligand bonds. For complexes with significant static correlation, a functional like TPSSh or M06-L might be more appropriate than B3LYP.

- Step 3: Conduct a QTAIM Analysis Perform a Quantum Theory of Atoms in Molecules (QTAIM) analysis using software like Multiwfn [44] [45]. This analysis calculates the electron density ρ(r) and its Laplacian ∇²ρ(r) at bond critical points (BCPs). A negative Laplacian indicates covalent character, while a positive value suggests electrostatic (ionic) interaction [44].

Issue: Calculation is Too Computationally Expensive for a Large Composite System

- Step 1: Employ a Multi-Layer Approach (ONIOM) Use the ONIOM method to treat a small, active region (e.g., the metal center and primary ligands) with a high-level method (e.g., B3LYP), and the larger, less critical environment (e.g., the graphene oxide sheet) with a lower-level method (e.g., PM6).

- Step 2: Optimize Basis Set Start with a smaller basis set (e.g., 6-31g(d)) for initial geometry optimizations and then perform a single-point energy calculation with a larger basis set (e.g., 6-31+g(d,p)) on the optimized geometry.

- Step 3: Leverage Parallel Computing Ensure your computational software (e.g., Gaussian 09) is configured to use multiple processors to speed up the calculation.

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Table 1: Calculated Electronic Properties for a SiO₂/GO/Pb₃O₄/Bi₂O₃ Composite [43]

| Model Molecule | Total Dipole Moment (Debye) | HOMO (eV) | LUMO (eV) | HOMO-LUMO Gap (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bi₂O₃ | Data not available in source | Data not available in source | Data not available in source | Data not available in source |

| 3SiO₂/GO/Pb₃O₄/Bi₂O₃ (Complex) | 35.1 | Data not available in source | Data not available in source | 0.158 |

| 3SiO₂/GO/Pb₃O₄/Bi₂O₃ (Weak) | Data not available in source | Data not available in source | Data not available in source | Data not available in source |

Table 2: Electronic Properties of Graphene Oxide (GO) and Benzoic Acid (BA) Complexes [45]

| Structure | Total Dipole Moment (Debye) | HOMO-LUMO Gap (eV) |

|---|---|---|

| GO | 4.119 | 2.939 |

| BA | 1.915 | 5.780 |

| GO/BA - OH interaction | 4.207 | 2.946 |

| GO/BA - COOH interaction | 4.893 | 2.910 |

| GO/2BA - OH and COOH | 2.686 | 2.910 |

Protocol: Detailed Workflow for DFT Study of a Metal-Composite Biosensor This protocol is based on the methodology used to study a SiO₂/GO/Pb₃O₄/Bi₂O₃ composite for glutamic acid biosensing [43].

System Preparation:

- Construct model molecules sequentially to mimic experimental steps: start with a SiO₂ substrate, add a GO layer, then integrate metal oxides (Pb₃O₄, Bi₂O₃).

- Define the type of interaction between components ("weak" physisorption or "complex" chemisorption).

Computational Setup (Using Gaussian 09):

- Method: Density Functional Theory (DFT).

- Functional: B3LYP.

- Basis Set: SDD for all atoms.

- Key Calculations: Geometry optimization, frequency, and single-point energy.

Property Calculation:

- Total Dipole Moment (TDM): Obtain directly from the output of the single-point calculation.

- HOMO-LUMO Gap: Calculate as ΔE = ELUMO - EHOMO.

- Reactivity Descriptors: Compute using the HOMO and LUMO energies:

- Ionization Potential (I) ≈ -EHOMO

- Electron Affinity (A) ≈ -ELUMO

- Chemical Potential (μ) = -(I + A)/2

- Chemical Hardness (η) = (I - A)/2

- Density of States (DOS): Use Gauss Sum 3 software to process the output file and generate DOS plots.

Analysis:

Mandatory Visualization

DFT Calculation Workflow for Electronic Properties

Reactivity Descriptors from HOMO-LUMO

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Parameters

| Item / Software | Function / Description | Example Use Case / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian 09 | A comprehensive software package for electronic structure modeling. | Used for geometry optimization, frequency, and single-point energy calculations [43] [44]. |

| B3LYP Functional | A hybrid density functional theory method. | Provides a good balance of accuracy and cost for organic systems and transition metal complexes [43] [45]. |

| SDD Basis Set | A basis set incorporating effective core potentials. | Recommended for systems involving heavier elements (e.g., Pb, Bi) [43]. |

| 6-31+G(d,p) Basis Set | A polarized and diffuse basis set for light atoms. | Often used with LanL2DZ for first-row transition metals [44]. |

| Gauss Sum | Software for analyzing the results of computational chemistry calculations. | Used specifically for generating Density of States (DOS) plots [43]. |

| Multiwfn | A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. | Used for conducting QTAIM and Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP) analysis [44] [45]. |

| IEF-PCM Model | A solvation model to simulate the effect of a solvent. | Critical for calculating redox potentials and simulating experimental conditions [44]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Parameter Selection and Methodology

Q1: How do I choose the right U value for my system? The optimal Hubbard U parameter is system-dependent. For metal oxides, a combination of Ud (for metal d-orbitals) and Up (for oxygen p-orbitals) is often necessary for accurate predictions of band gaps and lattice parameters [3]. The following table summarizes optimal (Up, Ud/f) pairs identified for common metal oxides [3]:

| Material | Structure | Up (eV) | Ud/f (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TiO₂ | Rutile | 8 | 8 |

| TiO₂ | Anatase | 3 | 6 |

| ZnO | Cubic | 6 | 12 |

| ZrO₂ | Cubic | 9 | 5 |

| CeO₂ | Cubic | 7 | 12 |

For non-oxide systems like CrI₃ monolayers, applying U to both the metal (Cr 3d) and ligand (I 5p) orbitals (e.g., Ud=3.5 eV, Up=2.0 eV) significantly improves agreement with hybrid functional calculations for electronic and magnetic properties [47].

Q2: What are the first-principles methods to compute U, and how do they compare? Several ab initio methods exist, each with strengths and weaknesses [3]:

| Method | Brief Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Linear Response (LR) | Computes U by applying a perturbative potential and measuring change in electronic occupancy [3]. | Can be computationally demanding as it requires supercell calculations to mitigate periodic interactions [3]. |

| Constrained Random Phase Approximation (cRPA) | Calculates effective U by distinguishing screening effects of localized and itinerant electrons [3]. | Computationally intensive [48]. |

| ACBN0 | A self-consistent, DFT-based approach that computes U and J values from the electron density [3]. | Determines site-specific U values within a single self-consistent field calculation [3]. |

| Bayesian Optimization (BO) | A machine learning approach that optimizes U to match a reference band structure (e.g., from HSE06) [48]. | Efficient; often lower cost than LR as it uses unit cell calculations. Accuracy depends on the reference [48]. |

Q3: When should I consider applying a Hubbard U correction to both metal and ligand orbitals? You should consider this approach when standard DFT+U (on metal sites only) fails to accurately reproduce key experimental properties or higher-level theoretical results. This combined correction has proven crucial for:

- Metal Oxides: Such as TiO₂, ZnO₂, CeO₂, and ZrO₂ for correct band gaps and lattice constants [3].

- Magnetic 2D Materials: Like CrI₃, for accurate electronic structure and magnetic anisotropy [47].

- Actinide Dioxides: Including UO₂, NpO₂, and PuO₂, where specific (U, J) pairs are needed for different functionals [49].

Troubleshooting Common Calculations

Q4: My geometry changes significantly after applying DFT+U. Is this normal, and how can I fix it? Yes, particularly with large U values, DFT+U can over-correct and cause excessive bond elongation [4]. Solutions include:

- Structurally-Consistent U Procedure: Relax the structure with an initial U value, then recompute U on this new structure, and iterate until U and the structure become consistent [4].

- Use DFT+U+V: For systems with significant covalency (e.g., metal oxides), an intersite "+V" term can help describe the hybridization better and prevent over-longation [4].

Q5: The electronic state I get with a high U value seems wrong. What happened? Open-shell systems often have multiple low-lying electronic states. The solution you converge to with one U value may not be the global minimum for another [4].

- Solution: Use the converged charge density from a calculation at one U value as the starting guess for a new calculation at the desired U value. You may need to manually promote occupation of different orbitals to explore various low-energy states [4].

Q6: I get an error that my "pseudopotential is not yet inserted." What does this mean? This means the code does not recognize the element you specified for the Hubbard correction [4].

- Check the element: Standard Hubbard atoms include transition metals, rare earths, and first-row elements like H, C, N, and O. If your element isn't on this list, you may need to modify the source code [4].

- Verify input: Ensure the