New Frontiers in Solid-State Materials Chemistry: Designing Next-Generation Inorganic Compounds

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest advancements and emerging trends in the solid-state chemistry of new inorganic compounds.

New Frontiers in Solid-State Materials Chemistry: Designing Next-Generation Inorganic Compounds

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest advancements and emerging trends in the solid-state chemistry of new inorganic compounds. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of novel material families, including mixed-anion systems and inorganic fluorides. It delves into innovative synthesis methodologies, from AI-driven discovery to low-temperature routes, and addresses key challenges in optimization and stability. By critically evaluating characterization techniques and comparing material performance for applications such as energy storage, electronics, and biomedicine, this review serves as a strategic guide for the rational design and development of advanced functional materials.

Discovering Novel Inorganic Solid-State Compounds: From Fundamental Chemistry to Emerging Material Families

The discipline of solid-state chemistry is fundamentally governed by the intricate and interdependent relationships between synthesis pathways, atomic-level structure, and macroscopic properties of inorganic compounds. This paradigm posits that the physical properties of a solid are a direct consequence of its internal structure, which is, in turn, dictated by the synthesis method employed [1]. The discovery of a material with the optimal combination of properties can instigate a paradigm shift in technology, as evidenced by the development of lithium-ion batteries, perovskite solar cells, and novel forms of carbon [1]. The primary objective of research in this field is to manipulate these relationships through precise control over chemical bonding, electron-electron interactions, dopant concentrations, and defect engineering to tailor materials for specific applications [2]. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of this landscape, framing the discussion within the context of pioneering new inorganic compounds and providing methodologies for systematic investigation.

Foundational Concepts and Relationships

The core principle of solid-state materials chemistry is that the synthesis route determines the atomic and electronic structure, which ultimately defines the observed physicochemical properties [1]. This relationship is not linear but a complex feedback loop, where characterization of properties can inform structural analysis, which then guides the refinement of synthesis protocols.

The "tool-box" available to the solid-state scientist is vast, enabling manipulation at multiple levels [1]:

- Composition: Varying the elemental constituents.

- Atomic Stacking: Controlling the arrangement of atoms in the crystal lattice.

- Anionic and/or Cationic Substitutions: Introducing dopants to alter electronic characteristics.

- Stoichiometry: Managing the balance of elements, including the creation of controlled non-stoichiometry.

- Nature and Competition of Chemical Bonds: Influencing the fundamental forces holding the structure together.

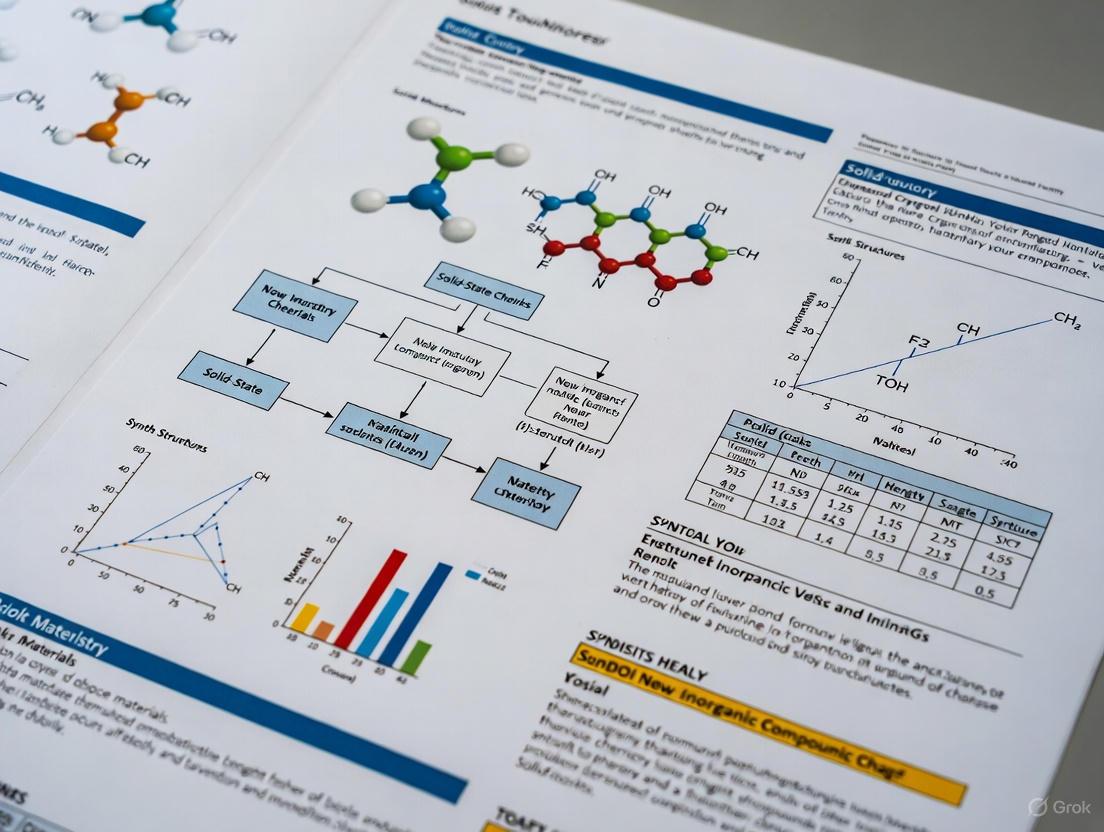

These manipulations are performed with the explicit goal of inducing specific functional properties, such as high-Tc superconductivity, multiferroism, ferroelectricity, insulator-metal transitions, and ionic conduction [1]. The relationships between these core concepts form a continuous R&D cycle, visualized in the following workflow.

Synthesis and Processing Methodologies

The synthesis of solid-state materials encompasses a wide spectrum of techniques, each imparting distinct structural characteristics and, consequently, unique properties to the final product. The choice of synthesis route is critical for achieving the desired phase purity, crystallinity, morphology, and defect structure.

Key Synthesis Protocols

Protocol 1: Conventional High-Temperature Solid-State Reaction

- Objective: To produce polycrystalline ceramic samples through direct reaction of solid precursor powders.

- Materials: High-purity precursor oxides, carbonates, or other salts; mortars and pestles (agate or alumina); high-temperature furnaces; alumina or platinum crucibles.

- Procedure:

- Weighing & Mixing: Precisely weigh starting reagents according to the target stoichiometry. Mechanically mix using a mortar and pestle or a ball mill for 30-60 minutes to achieve homogeneity.

- Calcination: Transfer the mixture to a suitable crucible and heat in a furnace at an intermediate temperature (e.g., 800-1000°C) for 10-20 hours to initiate reaction and decompose carbonates/nitrates.

- Grinding & Pelletizing: Carefully remove the calcined powder, regrind to ensure uniformity, and press into pellets using a uniaxial or isostatic press at pressures of 1-5 tons to improve interparticle contact.

- Sintering: Fire the pellets at the final high temperature (e.g., 1200-1500°C, material-dependent) for 24-48 hours with one or more intermediate regrinding steps to ensure complete reaction and homogeneity.

- Critical Parameters: Heating/cooling rates, atmosphere (air, oxygen, argon), and maximum temperature. Phase purity must be verified after each thermal treatment using X-ray diffraction (XRD).

Protocol 2: Sol-Gel (Chimie Douce) Synthesis

- Objective: To produce homogeneous, high-purity materials, including nanoparticles and thin films, at lower temperatures.

- Materials: Metal alkoxides or inorganic salts (e.g., nitrates), solvent (e.g., ethanol), water, catalyst (acid or base), magnetic stirrer with hotplate.

- Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve the metal precursor in the solvent under vigorous stirring.

- Hydrolysis: Slowly add a controlled amount of water (with or without a catalyst) to the solution to initiate hydrolysis of the metal alkoxide, forming M-OH bonds.

- Condensation: Allow the solution to stir for several hours to promote condensation reactions (formation of M-O-M bonds), leading to the formation of a colloidal suspension (sol).

- Gelation: Continue the process until the viscosity significantly increases, forming a wet gel.

- Ageing & Drying: Age the gel for 24 hours, then dry at elevated temperatures (e.g., 80-120°C) to remove solvents, resulting in a xerogel.

- Calcination: Finally, heat the xerogel to crystallize the desired phase.

- Critical Parameters: pH, water-to-precursor ratio, temperature, and concentration. This method allows excellent control over composition and is ideal for doping and creating hybrid materials.

Other advanced synthesis techniques include hydrothermal/solvothermal synthesis, chemical vapor deposition (CVD) for thin films, spark plasma sintering for dense ceramics, and electrochemical synthesis [1].

Advanced Characterization Techniques for Structure-Property Elucidation

A comprehensive understanding of the structure-property relationship necessitates the application of a suite of characterization techniques that probe the material at various length scales.

Table 1: Key Characterization Techniques in Solid-State Chemistry

| Technique | Structural Information Obtained | Property Correlation | Sample Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray Diffraction (XRD) [1] | Crystal structure, phase purity, lattice parameters, crystallite size. | Relates crystal symmetry and phase to functional properties like conductivity and magnetism. | Powder (ideally < 10 µm) or solid crystalline specimen. |

| PDF Total Scattering Analysis [1] | Local atomic structure, short-range order, defects in crystalline and amorphous materials. | Correlates local distortions with properties like ionic conduction and catalytic activity. | Powder. |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) [1] | Real-space imaging of atomic arrangements, crystal defects, and nanoscale morphology. | Directly links atomic-scale defects and interfaces to macroscopic behavior. | Electron-transparent thin specimen (< 100 nm). |

| X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (EXAFS/XANES) [1] | Local coordination environment, oxidation state, and bond distances around a specific element. | Essential for understanding catalytic sites, battery materials, and magnetic centers. | Can be powder, solid, or liquid. |

| Solid-State NMR [1] | Local chemical environment, coordination number, and dynamics for NMR-active nuclei. | Probes cation environments and ion mobility in glasses, ceramics, and battery materials. | Powder. |

| Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) | Elemental composition, chemical state, and electronic structure of the surface. | Correlates surface chemistry with properties like catalytic activity and interfacial reactions. | Solid, ultra-high vacuum compatible. |

The workflow for characterizing a new solid-state material typically integrates multiple techniques to build a complete picture from the atomic to the macroscopic scale, as shown in the following diagnostic pathway.

Computational and Theoretical Modeling Approaches

Computational methods have become indispensable for predicting properties, understanding experimental data, and guiding the synthesis of new materials. The integration of computation with experiment accelerates the discovery process.

First-Principles and Machine Learning Methods

Density Functional Theory (DFT) is a cornerstone for calculating electronic structure, enabling predictions of structural stability, electronic band gaps, density of states, and Fermi surfaces [1]. These calculations help interpret UV-Vis and EELS spectra and rationalize magnetic and optical properties based on chemical bonding.

Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) modeling is an analytical approach that correlates numerical descriptors of a molecule or crystal with its physical properties [3] [4]. In chemical graph theory, topological indices—graph-invariant numerical metrics derived from molecular structure—are used as descriptors in QSPR models to predict properties like molar reactivity, polar surface area, and molecular weight without costly experiments [4]. The general workflow for QSPR model development and application is standardized.

Machine Learning (ML) is now used to mine existing materials data and identify novel design principles [2] [5]. Tools like QSPRpred provide a flexible, open-source Python API for building reproducible QSPR models that serialize both the model and the required data pre-processing steps, facilitating deployment and transferability [6].

Table 2: Computational Modeling Tools for Solid-State Chemistry

| Computational Method | Primary Function | Representative Application | Key Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) [1] | Electronic structure calculation. | Predicting stability and band gap of a new inorganic phosphor. | Total energy, band structure, density of states. |

| QSPR Modeling [6] [4] | Statistical correlation of structure and property. | Predicting aqueous solubility of a drug-like molecule or activity of a catalyst. | Predictive regression or classification model. |

| COSMO-RS [3] | Prediction of thermodynamic properties. | Screening ionic liquids or deep eutectic solvents for solubility and toxicity. | Chemical potentials, activity coefficients. |

| The Materials Project [7] | Database of computed material properties. | High-throughput search for new battery electrode materials. | Computed phase diagrams, voltage profiles, etc. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The experimental and computational research in solid-state chemistry relies on a suite of essential reagents, instruments, and software tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Solid-State Chemistry

| Reagent/Instrument | Function/Purpose | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Precursors | Source of metal cations and anions for synthesis. | Oxides (e.g., TiO₂, ZrO₂), Carbonates (e.g., Li₂CO₃), Nitrates (e.g., Fe(NO₃)₃·9H₂O); purity ≥ 99.9% is often critical. |

| Metal Alkoxides | Molecular precursors for sol-gel synthesis. | Titanium isopropoxide (Ti(O^iPr)â‚„), Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS, Si(OEt)â‚„); handling requires inert atmosphere. |

| Alumina/Platinum Crucibles | Containers for high-temperature reactions. | Alumina (Al₂O₃) for most general uses; Platinum for reactive or high-purity systems. |

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [7] | Repository of known crystal structures for reference and analysis. | Critical for phase identification via XRD; contains crystal structure data of inorganic compounds from 1913-present. |

| NIST Chemistry WebBook [7] | Source of thermochemical, thermophysical, and ion energetics data. | Provides critically evaluated reference data for pure compounds and reactive intermediates. |

| QSPRpred Software [6] | Open-source Python toolkit for building QSPR models. | Enables data set analysis, model creation, and deployment with integrated serialization for reproducibility. |

| The Materials Project [7] | Web-based resource for computed material properties. | Used for screening materials for specific applications (e.g., batteries, catalysts) via high-throughput DFT data. |

| Acridinium, 9,10-dimethyl- | Acridinium, 9,10-dimethyl-|High-Purity Reagent | |

| N-Acetylglycyl-D-alanine | N-Acetylglycyl-D-alanine | High-purity N-Acetylglycyl-D-alanine for research applications. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Application-Oriented Property Targeting and Case Studies

The ultimate goal of understanding synthesis-structure-property relationships is the rational design of materials for targeted applications. Key application areas driving current research include:

Energy Materials

- Beyond Li-ion Battery Materials: Research is encouraged on the synthesis and fundamental investigation of next-generation battery materials, such as sodium-ion, magnesium-ion, and solid-state electrolytes [5]. The focus is on understanding ionic conduction mechanisms and interface-related phenomena through structure-property studies.

- Thermoelectric Materials: These materials convert waste heat to electricity. Property optimization involves engineering electronic structure for high electrical conductivity while introducing phonon-scattering centers to minimize thermal conductivity, often through nanostructuring [1].

- Photovoltaics: Perovskite solar cells are a prime example where the crystal structure of hybrid organic-inorganic halide perovskites directly leads to exceptional light absorption and charge carrier mobility [1].

Environmental and Sustainable Materials

- Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs): These porous, crystalline solids are designed for catalysis, gas storage (Hâ‚‚, CHâ‚„), and COâ‚‚ capture [1]. Their properties are tailored by modifying the metal clusters and organic linkers during synthesis.

- Environmental Remediation Sorbents: Materials are developed for industrial cleanup and nuclear waste management, requiring precise control over pore size and surface chemistry to target specific contaminants [1].

Quantum and Electronic Materials

- Materials for Quantum Technologies: This includes the design of 2D materials, heterostructures, and magnetic materials where quantum phenomena emerge from specific atomic arrangements [1]. Synthesis efforts focus on creating high-quality, defect-controlled interfaces.

- Multiferroics and Magnetoelectrics: These materials exhibit coupled magnetic and electric orders. The property goal is achieved by synthesizing complex oxides with specific non-centrosymmetric crystal structures that allow such cross-coupling [1].

The solid-state landscape is defined by the deep and causal connections between synthesis, structure, and properties. Mastering this relationship is the key to innovating next-generation technologies. Future progress will be fueled by the integration of advanced computational methods like machine learning with high-fidelity experimental synthesis and characterization [2] [5]. Emerging frontiers include the exploration of mixed-anion compounds (e.g., oxyfluorides, oxynitrides) to finely tune electronic properties, the design of hierarchical architectures across multiple length scales, and an intensified focus on sustainability throughout the material lifecycle [1] [8]. As these trends converge, the solid-state materials chemistry community is poised to continue its vital role in addressing global challenges in energy, information technology, and environmental sustainability.

Inorganic solid-state chemistry serves as a cornerstone for developing materials with tailored functionalities, directly addressing societal demands for advanced sustainable technologies [1]. Within this field, mixed-anion compounds—solids containing more than one type of anion—represent a rapidly growing research frontier [9] [10]. These materials leverage the distinct chemical characteristics of different anions (e.g., oxide, sulfide, halide, nitride, carbodiimide) within a single structure to achieve electronic and optical properties often unattainable in single-anion systems [11] [10]. The presence of multiple anions introduces an additional degree of freedom for materials design, enabling precise tuning of band gaps, band energies, carrier mobilities, and magnetic exchange interactions [11] [10]. This strategy, often termed anion engineering, is pivotal for innovations in energy conversion and storage, photovoltaics, photocatalysis, and quantum materials [12] [13]. This review details the synthesis, characterization, and electronic structure control of mixed-anion compounds, framing the discussion within the broader context of solid-state materials chemistry research on new inorganic compounds.

Fundamental Concepts and Significance of Anion Engineering

The electronic properties of a solid-state material are fundamentally governed by its composition and atomic-level structure. In mixed-anion compounds, the deliberate incorporation of anions with different sizes, electronegativities, and polarizabilities disrupts the local symmetry and creates unique bonding environments for cation centers [11] [13]. This heteroanionic coordination allows for a finer manipulation of the crystal and electronic structure than is possible with cation substitution alone.

A key principle in this field is the isolobal relationship between anions, where different anions or anionic groups can fulfill similar structural roles. A prominent example is the (NCN)^2- carbodiimide unit, which is considered isolobal to chalcogenide anions (O^2-, S^2-), enabling the design of carbodiimide-based analogs of known oxide and sulfide structures [14]. The electron distribution within such a unit is highly sensitive to the nature of the surrounding metal cations, influenced by Pearson's Hard and Soft Acid-Base (HSAB) principle [14].

The primary electronic parameter controlled via anion engineering is the electronic band gap. For instance, incorporating more polarizable anions (e.g., I^- or Se^2-) alongside O^2- typically leads to a narrowing of the band gap by elevating the valence band maximum through the introduction of higher-energy anion p-states [13]. This is critically important for designing materials such as visible-light-absorbing photocatalysts and solar absorbers, where optimal band gaps are required for harnessing solar energy efficiently [12] [13]. Furthermore, anion engineering can induce reduced dimensionality, creating natural quantum wells or layers that lead to anisotropic charge transport and unique phenomena like giant second-harmonic generation (SHG) [13].

Synthesis and Experimental Methodologies

The synthesis of mixed-anion compounds presents unique challenges, as conventional high-temperature solid-state reactions can lead to phase separation rather than the desired homogeneous multi-anion phase [11] [5]. Consequently, targeted synthetic approaches are essential. The following sections detail prominent methodologies, with specific experimental protocols for two representative compounds.

Ceramic Method (Solid-State Synthesis)

The ceramic method involves the direct reaction of solid precursors at elevated temperatures and is a workhorse for synthesizing thermodynamically stable mixed-anion compounds.

Case Study: Synthesis of Pb_8O_4I_6(CN_2) [14]

- Principle: Homogenization and reaction of precursor powders via mechanical grinding and subsequent heating.

- Reaction Stoichiometry:

3PbI_2 + 4PbO + Pb(CN_2) → Pb_8O_4I_6(CN_2) - Detailed Protocol:

- Preparative Procedures: The starting materials

PbI_2,PbO, andPb(CN_2)are combined in a 3:4:1 molar ratio. - Homogenization: The mixture is mechanically ground using a mortar and pestle inside an inert atmosphere glovebox to ensure a homogeneous mixture and intimate particle contact.

- Thermal Treatment: The ground powder is subjected to elevated temperatures (specific temperature not provided in source) in a sealed container to initiate the solid-state reaction.

- Product Isolation: The reaction yields

Pb_8O_4I_6(CN_2)as a dark yellow, air-stable powder. A minor side-phase of elemental lead may be detected.

- Preparative Procedures: The starting materials

- Characterization: Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) confirms phase purity and stability under ambient air. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) on single crystals verifies the Pb:I ratio as approximately 8:6.

Low-Temperature Solid-State Synthesis

For compounds containing volatile elements or metastable phases, low-temperature synthesis is crucial to prevent decomposition.

Case Study: Synthesis of A_2BaTaS_4Cl (A = K, Rb, Cs) [11]

- Principle: Reaction of precursors at temperatures below their melting or decomposition points, often using sealed containers to control vapor pressure.

- Detailed Protocol:

- Preparative Procedures: Precursors

A_2S_x,BaS,ACl,Tametal, andSare combined in a stoichiometric ratio inside anN_2-filled glovebox. - Homogenization: Materials are homogenized with a mortar and pestle.

- Container Preparation: The mixture is charged into an aluminum-lined, carbon-coated fused silica tube to prevent reaction with the tube walls.

- Thermal Treatment: The sealed tube is heated in a programmable furnace to 575 °C at a rate of 45 °C per hour, held at this temperature for 24 hours, and then cooled to room temperature at 10 °C per hour.

- Post-Synthesis Processing: The resulting orange-yellow powder is washed with anhydrous dimethylformamide (DMF) to remove excess

A_2S_x, yielding a whitish-yellow powder.

- Preparative Procedures: Precursors

- Characterization: PXRD confirms phase formation, often alongside minor secondary phases. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction is used for definitive structural determination.

Single Crystal Growth

Single crystals, essential for determining complex crystal structures, are often grown via similar solid-state methods but with modified thermal profiles to encourage crystal nucleation and growth over rapid powder formation [11]. For the A_2BaMS_4Cl family, this involves heating stoichiometric mixtures to a higher temperature of 750 °C with a faster ramp rate of 60 °C per hour, followed by slow cooling [11].

The following workflow diagram summarizes the two primary synthetic pathways for obtaining mixed-anion compounds, from precursor preparation to final characterization.

Structural Diversity and Electronic Properties

Mixed-anion compounds exhibit remarkable structural diversity, which directly underpins their tunable electronic properties. The table below summarizes the crystal structures and key electronic properties of several recently reported mixed-anion compounds.

Table 1: Structural and Electronic Properties of Selected Mixed-Anion Compounds

| Compound | Crystal System / Space Group | Key Structural Features | Band Gap (eV) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Pb_8O_4I_6(CN_2) |

Monoclinic, C2/c |

Heterocubane-type [Pb_4O_4] units interconnected by iodide bridges and (NCN)^2- units. |

n-type semiconductor | [14] |

K_2BaTaS_4Cl |

Tetragonal, I4/mcm |

Isolated [TaS_4]^(3-) tetrahedra encapsulated in a K/Ba-Cl ionic cage. |

~3.0 | [11] |

K_2BaNbS_4Cl |

Tetragonal, I4/mcm |

Isolated [NbS_4]^(3-) tetrahedra encapsulated in a K/Ba-Cl ionic cage. |

~2.5 | [11] |

Bi_2O_2Se |

Tetragonal, I4/mmm |

Layered structure with [Bi_2O_2]^(2+) layers and Se atoms. |

(Indirect) | [13] |

BiOCl |

Tetragonal, P4/nmm |

Layered structure with [Bi_2O_2]^(2+) layers interleaved with double Cl atom layers. |

(Wide gap) | [13] |

NbOI_2 |

Monoclinic, C2 |

Low-symmetry layered structure with van der Waals gaps. | (Narrow gap) | [13] |

Structural Motifs and Property Relationships:

- Discrete Units in 3D Frameworks: Compounds like

A_2BaTaS_4Clfeature isolated[MS_4]tetrahedra (M = Nb, Ta) separated by alkali/alkaline-earth metal and halide ions. This structural isolation contributes to their wide, insulating band gaps. The difference in band gap between the Ta (~3.0 eV) and Nb (~2.5 eV) compounds reflects the lower energy of the Nb 4d orbitals compared to the Ta 5d orbitals [11]. - Complex Clusters and Frameworks: The structure of

Pb_8O_4I_6(CN_2)is built around a heterocubane-type[Pb_4O_4]unit, a motif known in Pb-O chemistry where the stereochemically active6s^2lone pair onPb^(2+)influences the local coordination geometry. These clusters are interconnected by iodide anions and linear(NCN)^2-carbodiimide units, creating a complex 3D network that results in semiconducting behavior [14]. - Layered Oxycompounds: Materials like

Bi_2O_2Se,BiOCl, andNbOI_2possess naturally layered structures, often held together by weak van der Waals or electrostatic forces between the layers. This layered nature facilitates the exfoliation of bulk crystals into monolayers or few-layer nanosheets, which is highly advantageous for nanoelectronics [13]. The mixture of anions within and between the layers allows for exceptional property tuning. For example:Bi_2O_2Seexhibits an ultra-high electron mobility (up to 28,900 cm² Vâ»Â¹ sâ»Â¹ at low temperatures), making it a promising candidate for high-speed electronics [13].NbOI_2demonstrates a giant and tunable second-harmonic generation (SHG) response, surpassing the performance of most known 2D nonlinear optical materials [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The synthesis and characterization of mixed-anion compounds require a carefully selected set of precursors and analytical tools. The following table details key reagents and their functions in the featured experiments.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Mixed-Anion Compound Synthesis

| Material / Reagent | Function in Synthesis | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Oxides (e.g., PbO) | Source of oxide (O^(2-)) anions; often a primary cation source. |

Ceramic synthesis of Pb_8O_4I_6(CN_2) [14]. |

| Metal Halides (e.g., PbIâ‚‚, ACl) | Source of halide anions (Iâ», Clâ»); can also act as a flux to enhance crystal growth. |

Precursor in Pb_8O_4I_6(CN_2) and A_2BaTaS_4Cl syntheses [14] [11]. |

| Metal Chalcogenides (e.g., Aâ‚‚Sâ‚“, BaS) | Source of chalcogenide anions (S^(2-)); provides the chalcogenide framework. |

Low-temperature synthesis of A_2BaTaS_4Cl [11]. |

| Metal Carbodiimides (e.g., Pb(CNâ‚‚)) | Source of the linear (NCN)^(2-) anion, which acts as a bridging ligand. |

Incorporating the carbodiimide unit in Pb_8O_4I_6(CN_2) [14]. |

| Elemental Metals (e.g., Ta, Nb) | Source of the transition metal cation in its elemental state for controlled reaction. | Synthesis of A_2BaTaS_4Cl and K_2BaNbS_4Cl [11]. |

| Elemental Chalcogens (e.g., S) | Provides stoichiometric balance of chalcogen in the reaction mixture. | Synthesis of A_2BaTaS_4Cl [11]. |

| Anhydrous Solvents (e.g., DMF) | Post-synthesis washing agent to remove soluble byproducts (e.g., excess Aâ‚‚Sâ‚“). | Purification of A_2BaTaS_4Cl powders [11]. |

| Sealed Silica Tubes | Reaction vessel to maintain an inert atmosphere and contain volatile reactants. | Essential for all low-temperature syntheses involving sulfides or halides [11]. |

| 6-Methylhept-1-en-3-yne | 6-Methylhept-1-en-3-yne, CAS:28339-57-3, MF:C8H12, MW:108.18 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 4-Azido-2-chloroaniline | 4-Azido-2-chloroaniline, CAS:33315-36-5, MF:C6H5ClN4, MW:168.58 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Mixed-anion compounds represent a vibrant and expanding frontier in solid-state chemistry, offering a powerful strategy for designing materials with precisely controlled electronic structures. Through anion engineering, researchers can manipulate key properties such as band gaps, charge carrier mobility, and nonlinear optical responses in ways that are not feasible with single-anion systems. The continued discovery of new materials—from complex 3D frameworks like Pb_8O_4I_6(CN_2) to low-dimensional systems like Bi_2O_2Se—underscores the structural and functional richness of this class of compounds.

Future research will likely focus on overcoming synthetic challenges to access even more complex and metastable phases, potentially through advanced techniques like electrochemical methods or soft chemistry routes [12] [1]. The integration of computational and machine-learning approaches is poised to play a greater role in predicting new stable compounds with desired structures and properties [12] [5]. As characterization techniques and theoretical understanding advance, the rational design of mixed-anion compounds will further accelerate, solidifying their role in enabling next-generation technologies for sustainable energy, advanced electronics, and quantum information science.

Solid-state chemistry of inorganic fluorides gained significant importance in the second half of the 20th century, establishing fundamental relationships between structural networks and their resultant physical properties [15]. The discovery in the 1960s of series of AxMF3 fluorides with structures analogous to tungsten oxide bronzes marked a pivotal advancement, launching extensive investigations into compounds based on Al, Ga, and transition metals with structures derived from ReO3, hexagonal tungsten bronze (HTB), tetragonal tungsten bronzes (TTB), defect pyrochlore, and perovskite frameworks [15] [16]. These materials were initially studied for their magnetic properties, but research has since expanded to encompass diverse applications including positive electrodes in Li-ion batteries, UV absorbers, and multiferroic components [15].

The exceptional electronic properties of elemental fluorine (F2) underlie many of the outstanding characteristics exhibited by these fluoride materials [15] [16]. Today, solid-state inorganic fluorides have reached nano-sized dimensions as components in numerous advanced technologies, including Li batteries, all solid-state fluorine batteries, micro- and nano-photonics, fluorescent probes, solid-state lasers, nonlinear optics, and superhydrophobic coatings [15]. This review examines the structural chemistry of AxMF3 fluorides from their initial discovery to recent investigations of their physico-chemical properties, with particular emphasis on materials derived from ReO3, perovskite, defect-pyrochlore, and tungsten bronze structural types.

Structural Networks in Inorganic Fluorides

Fundamental Structural Types

Inorganic fluorides exhibit diverse structural networks based on corner-sharing MF6 octahedra with remarkable versatility in their connectivity patterns. These structural families share fundamental relationships, often described as derivatives of simple parent structures.

Table 1: Fundamental Structural Types in Inorganic Fluorides

| Structural Type | General Formula | Structural Features | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| ReO₃-type | MF₃ | Corner-sharing octahedra forming 3D network with vacant A-sites | ReO₃, WO₃, AlF₃, ScF₃ [17] |

| Perovskite | AMF₃ | MF₆ octahedra with A-cations occupying cuboctahedral cavities | KNiF₃, NaMgF₃ [17] |

| Hexagonal Tungsten Bronze (HTB) | Aâ‚“MF₃ | Hexagonal tunnels containing A-cations | Aâ‚“M²âºâ‚“M³âºâ‚â‚â‚‹â‚“â‚ŽF₃ (A = Cs, Rb; M²⺠= Co, Ni, Zn; M³⺠= V) [15] |

| Tetragonal Tungsten Bronze (TTB) | AₓMF₃ | Complex framework with triangular, square and pentagonal channels | KₓAlF₃, RbₓFeF₃ [15] |

| Defect Pyrochlore | Aâ‚“Mâ‚‚F₇ | Network of corner-sharing octahedra with vacancies | CsMn²âºMn³âºF₆ [18] |

The ReO₃-type structure represents the simplest framework, consisting of a three-dimensional network of corner-sharing MF6 octahedra with no A-site cations, resulting in the composition MF₃ [17]. This structure is characterized by its openness, with significant empty space in the lattice. The perovskite structure (AMF₃) can be described as a derivative of the ReO₃ type where the A-site cavities are occupied by cations [17]. The structural relationship can be understood as AMF₃ = A + MF₃ (ReO₃-type), highlighting how perovskite structures build upon the fundamental ReO₃ framework by filling the vacant sites.

Tungsten bronze derivatives represent more complex structural variations. The hexagonal tungsten bronze (HTB) structure features hexagonal tunnels that can accommodate various A-cations, with general formula Aâ‚“MF₃ [15]. The tetragonal tungsten bronze (TTB) structure provides an even more complex framework with multiple channel types [15]. Recent research has successfully synthesized quaternary HTB fluorides, Aâ‚“M²âºâ‚“M³âºâ‚â‚â‚‹â‚“â‚ŽF₃ (where A = Cs and Rb; M²⺠= Co²âº, Ni²âº, and Zn²âº; and M³⺠= V³âº), via mild hydrothermal routes [18]. These compounds demonstrate the versatility of HTB frameworks in accommodating diverse metal cations while maintaining structural integrity.

The defect pyrochlore structure represents another important structural family, characterized by a network of corner-sharing octahedra with specific cation ordering patterns. An illustrative example is CsMn²âºMn³âºF₆, which exhibits charge ordering of Mn²⺠and Mn³⺠sites and displays interesting magnetic behavior including canted antiferromagnetism with a hard ferromagnetic component [18].

Structural Relationships and Derivative Formation

The structural families of inorganic fluorides exhibit intimate relationships, often through simple structural operations. The following diagram illustrates these relationships and the experimental approaches to synthesize these materials:

These structural relationships enable precise control over material properties through chemical modifications. The flexibility of these frameworks allows for extensive cation and anion substitutions, enabling tuning of electronic, magnetic, and optical properties for specific applications.

Experimental Protocols and Synthesis Methodologies

Synthesis of Tungsten Bronze Fluorides

The synthesis of complex tungsten bronze fluorides requires specialized approaches to achieve the desired structural ordering and composition control.

Mild Hydrothermal Synthesis of HTB Fluorides

The synthesis of quaternary hexagonal tungsten bronze (HTB) fluorides with formula Aâ‚“M²âºâ‚“M³âºâ‚â‚â‚‹â‚“â‚ŽF₃ (where A = Cs, Rb; M²⺠= Co²âº, Ni²âº, Zn²âº; M³⺠= V³âº) employs a carefully controlled hydrothermal method [18]:

Precursor Preparation: Dissolve appropriate molar ratios of transition metal salts (chlorides or fluorides) in deionized water. For vanadium-containing systems, use VCl₃ as the V³⺠source.

Cation Mixing: Combine the transition metal solutions in stoichiometric ratios corresponding to the target composition, maintaining constant stirring to ensure homogeneity.

Alkali Addition: Add concentrated hydrofluoric acid (HF) solution to the mixture, followed by the introduction of cesium or rubidium fluoride salts as the A-site cation source.

Reaction Vessel Loading: Transfer the reaction mixture to a Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave, filling to approximately 70-80% capacity to maintain appropriate pressure conditions.

Hydrothermal Treatment: Heat the autoclave to temperatures between 160-200°C for 24-72 hours under autogenous pressure. The specific temperature and time depend on the composition target.

Product Recovery: After gradual cooling to room temperature, collect the crystalline products by vacuum filtration, wash repeatedly with deionized water and ethanol to remove residual salts, and dry at 80°C under vacuum.

This method enables the incorporation of multiple transition metals with controlled oxidation states and ordering within the HTB framework, which is crucial for tailoring magnetic properties.

Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of HTB-Type Compounds

Microwave-assisted synthesis provides an alternative route for stabilizing iron-based fluoride compounds with HTB-type structure [18]:

Prepare a solution of iron(III) fluoride (FeF₃) in diluted hydrofluoric acid.

Add the structure-directing agents (cesium or rubonium salts) to the solution.

Transfer the mixture to microwave-compatible vessels.

Apply microwave irradiation at controlled power levels (typically 100-300W) for short durations (5-30 minutes) at temperatures of 150-200°C.

Rapidly quench the reaction to room temperature and isolate the products.

This method is particularly effective for producing compounds with partial hydroxide substitution, such as FeF₂.₂(OH)₀.₈·(H₂O)₀.₃₃, which demonstrates anionic vacancies that enhance electrochemical performance in lithium cells [18].

Synthesis of Defect Pyrochlore Fluorides

The synthesis of defect pyrochlore fluorides like CsMn²âºMn³âºF₆ employs a chloride reduction method under mild hydrothermal conditions [18]:

Redox Control: Utilize the chloride reduction pathway for Mn³⺠in the presence of CsCl, which serves both as a chloride source and reducing agent.

Precursor Mixture: Combine manganese(II) fluoride and manganese(III) fluoride in stoichiometric ratios in hydrofluoric acid solution.

Cesium Incorporation: Add cesium chloride to the reaction mixture, which provides both the A-site cation and the chloride reductant.

Hydrothermal Crystallization: Heat the mixture at 180°C for 48 hours in a Teflon-lined autoclave.

Crystallographic Analysis: Characterize the resulting crystals by powder neutron diffraction to confirm the charge-ordered structure of Mn²⺠and Mn³⺠sites.

This method demonstrates the importance of controlled redox chemistry in achieving specific cation ordering patterns within the defect pyrochlore structure, which directly influences the magnetic behavior of the material.

Table 2: Synthesis Methods for Inorganic Fluoride Materials

| Synthesis Method | Temperature Range | Key Advantages | Typical Products | Structural Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ceramic Method | High temperature (>600°C) | Simple setup, high crystallinity | Simple perovskites, ReO₃-types | Limited, often multiphase |

| Hydrothermal Synthesis | 150-250°C | Metastable phases, good crystals | HTB, TTB, pyrochlore fluorides | Excellent cation ordering |

| Microwave-Assisted | 150-250°C | Rapid synthesis, nanoscale products | Nanoparticles, substituted phases | Good size control |

| Chimie Douce (Soft Chemistry) | Room temperature - 150°C | Energy efficient, metastable phases | Intercalation compounds, defect-rich | Moderate crystallinity |

Properties and Applications

Magnetic Properties

Inorganic fluorides with tungsten bronze and perovskite-derived structures exhibit diverse magnetic behaviors that stem from their structural frameworks and cation ordering:

HTB Fluoride Magnetism: Quaternary HTB fluorides of composition Aâ‚“M²âºâ‚“M³âºâ‚â‚â‚‹â‚“â‚ŽF₃ (A = Cs, Rb; M²⺠= Co²âº, Ni²âº, Zn²âº; M³⺠= V³âº) display complex magnetic interactions due to the presence of multiple transition metals in specific crystallographic sites [18]. The magnetic properties are highly sensitive to the M²âº/M³⺠ratio and the specific identity of the transition metals, enabling tuning of magnetic transitions.

Defect Pyrochlore Magnetism: CsMn²âºMn³âºF₆ exhibits a canted antiferromagnetic structure with a hard ferromagnetic component, as determined by powder neutron diffraction [18]. The material undergoes successive long-range ordering of the Mn²⺠and Mn³⺠sites at different temperatures, demonstrating the complex magnetic behavior possible in these frameworks.

Multiferroic Behavior: Compounds in the K₃M³ᴵM²ᴵᴵFâ‚â‚… system, particularly K₃Feâ‚…Fâ‚â‚…, exhibit multiferroic properties with coupled magnetic and electric ordering [18]. These materials show magnetic transitions with slow magnetic dynamics, making them interesting for multifunctional devices.

Electrochemical Applications

Fluoride-based materials with open structural frameworks have demonstrated significant potential in electrochemical energy storage:

Positive Electrodes in Li-ion Batteries: Fluoride compounds with HTB and related structures serve as promising positive electrode materials due to their structural stability and reversible lithium intercalation capability [15]. The open channels in these frameworks facilitate lithium ion transport while maintaining structural integrity during charge-discharge cycles.

All Solid-State Fluorine Batteries: Nano-sized fluoride materials are being developed for advanced all solid-state fluorine battery systems [15] [16]. The high electronegativity of fluorine contributes to high operating voltages in these systems.

Anionic Vacancy Engineering: Mixed anion iron-based fluoride compounds with HTB structure, such as FeF₂.₂(OH)₀.₈·(H₂O)₀.₃₃, demonstrate enhanced electrochemical performance attributable to the presence of anionic vacancies that facilitate ion transport [18].

Optical and Photonic Properties

The unique electronic structures of fluoride materials enable various optical applications:

Luminescent Materials: Lanthanide-containing fluoride frameworks exhibit strong luminescent properties suitable for solid-state lasers, up- or down-conversion fluorescent probes, and nonlinear optics [15]. The EuBMOF and TbBMOF materials demonstrate how lanthanide ions in metal-organic frameworks can create solid-state luminescent sensors for fluoride detection [19].

UV Absorbers: Specific fluoride compositions with appropriate band gaps serve as effective UV absorbers in various optical applications [15].

Nonlinear Optics: The non-centrosymmetric structures of certain tungsten bronze fluorides make them candidates for nonlinear optical applications, including frequency doubling [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Fluoride Materials Synthesis

| Reagent/Chemical | Function in Research | Application Examples | Safety Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anhydrous HF | Fluorinating agent, mineralizer | Hydrothermal synthesis, fluorination reactions | Extreme toxicity, specialized equipment required |

| Metal Fluoride Salts | Metal cation sources | Precursors for solid-state synthesis | Some are hygroscopic, store in dry environment |

| Alkali Metal Fluorides | A-site cations in structures | CsF, RbF for tungsten bronze synthesis | Toxic if ingested, use in fume hood |

| Transition Metal Chlorides | Metal precursors for hydrothermal synthesis | MnCl₂, VCl₃ for reduction reactions | Some are moisture-sensitive, corrosive |

| Hydrochloric Acid | pH adjustment, cleaning | Autoclave cleaning, solution pH control | Corrosive, use appropriate PPE |

| Organic Solvents | Washing, purification | Ethanol, acetone for product washing | Flammable, use in well-ventilated areas |

| Structure-Directing Agents | Template for specific structures | Quaternary ammonium salts for porous frameworks | Varied toxicity, consult SDS |

| 2-Bromo-1,1-diethoxyoctane | 2-Bromo-1,1-diethoxyoctane, CAS:33861-21-1, MF:C12H25BrO2, MW:281.23 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 2-(Decyloxy)benzaldehyde | 2-(Decyloxy)benzaldehyde|C17H26O2|262.39 g/mol | Bench Chemicals |

Advanced Characterization Techniques

Understanding the structure-property relationships in inorganic fluorides requires sophisticated characterization methodologies:

In-situ/Operando Methods: Techniques such as PDF total scattering analysis, EXAFS, and SAXS allow researchers to monitor changes in cationic environments during synthesis or electrochemical operation [1]. These methods provide real-time insight into structural evolution under working conditions.

Spectroscopic Characterization: Moessbauer spectroscopy, NMR, and ESR spectroscopies enable determination of oxidation states and local environments around metal centers [1]. For fluoride materials, ¹â¹F NMR is particularly valuable for probing anion environments.

Microscopy Techniques: Advanced microscopy methods including TEM, AFM, and fluorescence microscopy provide detailed information about material morphology and interface structures [1]. These techniques are essential for correlating nanoscale features with macroscopic properties.

Magnetic Characterization: SQUID magnetometry enables detailed investigation of magnetic properties, including zero-field cooled and field cooled magnetization measurements to determine magnetic transition temperatures [18].

Inorganic fluorides with structures derived from tungsten bronze and perovskite types represent a versatile class of materials with exceptional structural diversity and tunable properties. The fundamental relationships between ReO₃, perovskite, HTB, TTB, and defect pyrochlore frameworks provide a rich playground for materials design. These materials continue to enable advances in numerous technological domains, from energy storage to quantum materials, demonstrating the enduring importance of fundamental solid-state chemistry research in addressing contemporary technological challenges.

Solid-state chemistry, the study of the preparation, structure, and properties of solid materials, serves as the foundational discipline for developing new inorganic compounds that address grand challenges in energy, materials, and catalysis [20]. Within this field, oxides, sulfides, and halides represent three critical material families whose distinct chemical properties and structural versatility enable their functional roles across transformative technologies. These inorganic compounds, characterized by their ionic bonding and crystalline structures, provide the essential platform for innovations in energy storage, electronics, and environmental applications [21]. The systematic design of these materials relies on understanding the profound connections between their atomic-scale composition, microscopic structure, and macroscopic functional properties—relationships that form the core of modern solid-state chemistry research [20].

The investigation of these material families aligns with broader thesis research on solid-state materials chemistry by demonstrating how targeted synthesis and structural control can yield compounds with tailored functionalities. As the scientific community continues to push the boundaries of inorganic synthesis, materials such as highly fluorinated coordination polymers for CO2 separation [20], rock-salt structured thermoelectrics [20], and advanced solid electrolytes [22] exemplify the innovative directions within the field. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical examination of oxide, sulfide, and halide material systems, their functional roles in modern technology, and the experimental methodologies essential for their development and characterization.

Material Family Fundamentals: Composition, Structure, and Properties

The chemical diversity and structural adaptability of oxides, sulfides, and halides stem from their fundamental compositional elements and bonding characteristics. Oxide minerals have oxygen (O²â») as their anion but exclude those with oxygen complexes such as carbonate (CO₃²â»), sulphate (SO₄²â»), and silicate (SiOâ‚„â´â») [23]. Sulfide minerals feature the S²⻠anion, which combines with metal cations to form compounds with significant electronic conductivity and catalytic properties [23]. Halide minerals contain anions from the halogen column of the periodic table (Cl, F, Br, etc.) and often display distinctive ionic conductivity and optical characteristics [23].

The systematic nomenclature for these inorganic compounds follows IUPAC conventions where the cation (metal) is always named first with its name unchanged, while the anion (nonmetal) is written after the cation, modified to end in –ide [24]. For transition metals with multiple possible oxidation states, Roman numerals in parentheses denote the specific charge, such as iron(II) oxide (FeO) versus iron(III) oxide (Fe₂O₃) [24]. This precise naming convention enables unambiguous communication of chemical composition throughout materials science research.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Key Inorganic Material Families

| Material Family | Anion Type | Chemical Bonding | Representative Examples | Characteristic Properties |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxides | O²⻠| Ionic to covalent | Hematite (Fe₂O₃), Corundum (Al₂O₃), LiCoO₂ | High mechanical/chemical stability, wide band gaps, diverse magnetic behavior |

| Sulfides | S²⻠| More covalent | Pyrite (FeS₂), Galena (PbS), Li₃PS₄ | Narrower band gaps, high ionic conductivity, catalytic activity |

| Halides | Fâ», Clâ», Brâ», Iâ» | Primarily ionic | Fluorite (CaFâ‚‚), Halite (NaCl), LiPSâ‚…Cl | Soft mechanical properties, high ion mobility, optical transparency |

The functional properties of these material families derive fundamentally from their electronic structures and bonding characteristics. Oxides typically exhibit a wide range of electronic behavior—from insulators like Al₂O₃ to superconductors like YBa₂Cu₃O₇—based on the transition metal cations and their coordination environments [25]. Sulfides often demonstrate narrower band gaps and greater polarizability due to the more diffuse nature of sulfur orbitals, enabling applications in photovoltaics and catalysis [26]. Halides, with their strongly ionic bonding and relatively simple crystal structures, frequently serve as model systems for understanding ion transport mechanisms and designing solid electrolytes [22].

Technological Applications and Functional Roles

Energy Storage and Battery Technologies

Solid-state batteries represent one of the most technologically significant applications for oxide, sulfide, and halide materials, where they function as solid electrolytes that replace flammable liquid alternatives [22]. Each material family offers distinct advantages and challenges for this application, driving extensive research into their optimization and implementation.

Table 2: Solid Electrolyte Material Families for All-Solid-State Batteries

| Material Family | Representative Compounds | Ionic Conductivity (S cmâ»Â¹) | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxides | Li₇La₃Zrâ‚‚Oâ‚â‚‚ (garnet), NASICON-type | ~10â»Â³ to 10â»â´ | Excellent chemical stability, wide electrochemical window, high safety | High sintering temperatures (>700°C), brittle, grain boundary resistance |

| Sulfides | Li₃PSâ‚„, Liâ‚â‚€GePâ‚‚Sâ‚â‚‚, argyrodites (LiPSâ‚…Cl) | ~10â»Â² to 10â»Â³ | High ionic conductivity, good processability, low temperature processing | Air sensitivity, releases toxic Hâ‚‚S, limited electrochemical stability |

| Halides | Li₃YCl₆, Li₃YBr₆ | ~10â»Â³ | Good oxidative stability, compatible with high-voltage cathodes | Sensitivity to moisture, incompatibility with lithium metal anodes |

Oxide-based solid electrolytes like garnet-type Li₇La₃Zrâ‚‚Oâ‚â‚‚ (LLZO) and NASICON-type structures excel in their exceptional chemical stability against electrode materials and safety characteristics, making them suitable for high-voltage battery systems [26]. Their high mechanical stability provides an additional advantage in preventing lithium dendrite formation [22]. However, their technological implementation faces challenges related to high-temperature processing requirements and interfacial resistance arising from rigid grain boundaries [26].

Sulfide electrolytes demonstrate superior ionic conductivity approaching that of liquid electrolytes, attributed to the higher polarizability of sulfur ions and the resulting lower activation barriers for lithium-ion migration [26]. Their mechanical softness enables better interfacial contact with electrode materials under moderate pressure, facilitating ion transport across interfaces [22]. Nevertheless, their extreme sensitivity to moisture and potential generation of toxic Hâ‚‚S gas necessitate stringent manufacturing controls [22].

Halide electrolytes represent an emerging category with promising oxidative stability and compatibility with high-voltage cathode materials [22]. While their current technological readiness level lags behind oxides and sulfides, recent research has demonstrated halide systems with respectable ionic conductivity and good processability [22]. Their primary limitations include hygroscopic tendencies and challenges in forming stable interfaces with lithium metal anodes [26].

Environmental and Separation Technologies

The application of inorganic materials in environmental technologies highlights the functional versatility of oxide, sulfide, and halide compounds. Highly fluorinated non-porous coordination polymers, for instance, demonstrate exceptional COâ‚‚ selectivity through a unique dissolution-like uptake process rather than conventional pore-based adsorption [20]. The dynamic perfluoroalkyl regions within these crystalline materials enable strong interactions with COâ‚‚ while excluding other gases like methane, offering promising pathways for carbon capture and gas separation technologies [20].

Sulfide minerals also find significant application in environmental remediation, particularly through their interactions with heavy metals. The surface reactivity of sulfide materials enables effective sequestration of toxic metal species from contaminated water systems. Meanwhile, oxide-based photocatalysts such as TiOâ‚‚ continue to serve as workhorse materials for photocatalytic water treatment and air purification, leveraging their favorable band gaps and surface properties to degrade organic pollutants [20].

Electronic, Magnetic, and Optical Applications

The diverse electronic and magnetic properties of oxide materials have established their fundamental role in modern electronics. Magnetic oxides like magnetite (Fe₃O₄) and hematite (Fe₂O₃) serve as critical components in data storage, sensors, and medical applications [23]. Complex oxide systems exhibiting multiferroic behavior—where ferroelectric and magnetic ordering coexist—enable next-generation memory devices with coupled electrical and magnetic control [20].

Sulfide materials contribute significantly to optoelectronic technologies, with their typically narrower band gaps compared to oxides making them suitable for photodetectors and photovoltaic applications. The structural flexibility of sulfide frameworks allows for precise tuning of their electronic properties through composition modification, as demonstrated in solid solutions like LiMnSbTe₃ with embedded van der Waals-like gaps that enhance thermoelectric performance [20].

Halide compounds have emerged as frontrunners in photonic applications, particularly with the rise of metal halide perovskites for photovoltaic and light-emitting devices. Their exceptional optical properties, including high absorption coefficients and tunable emission wavelengths, stem from the electronic configuration of halide ions and their interaction with metal cations in the crystal lattice [20]. Beyond perovskites, halide materials like fluorite (CaFâ‚‚) continue to serve essential roles in optical systems as lenses and windows due to their broad transmission ranges and low refractive indices [25].

Experimental Methodologies and Characterization Techniques

Synthesis Protocols

Solid-State Reaction Method

The conventional solid-state reaction approach represents the most widely employed technique for polycrystalline ceramic oxide and sulfide synthesis. The standard protocol involves:

- Precursor Preparation: High-purity starting materials (typically metal carbonates, oxides, or sulfides) are precisely weighed according to stoichiometric calculations, with careful attention to hygroscopic compounds that may require drying before use.

- Mechanical Milling: The powder mixture undergoes intensive grinding using ball milling or mortar and pestle to achieve homogeneous mixing and reduce particle size to the micrometer scale, thereby enhancing reaction kinetics by maximizing contact surfaces.

- Calcination Process: The mixed powders are subjected to heat treatment in controlled atmosphere furnaces (air, nitrogen, or argon) at temperatures typically ranging from 500°C to 1500°C, depending on material system. Multiple heating cycles with intermediate regrinding steps are often necessary to ensure complete reaction and phase purity.

- Product Characterization: Phase identification via X-ray diffraction (XRD) confirms formation of the desired compound, while scanning electron microscopy (SEM) evaluates morphology and particle size distribution.

For air-sensitive sulfide and halide materials, all synthesis steps must be performed in oxygen- and moisture-controlled environments such as glove boxes (<0.1 ppm Oâ‚‚ and Hâ‚‚O) or using sealed quartz ampoules evacuated to 10â»Â³ torr before heating [26].

Solution-Based Synthesis Routes

Solution processing methods offer advantages for achieving enhanced homogeneity and reduced synthesis temperatures:

- Coprecipitation Technique: Metal salt solutions (typically nitrates or chlorides) are mixed in stoichiometric ratios and added dropwise to a precipitating agent (e.g., oxalic acid or ammonium carbonate) under constant stirring. The resulting precipitate is filtered, washed, dried, and subsequently calcined at moderate temperatures.

- Sol-Gel Processing: Metal alkoxide precursors undergo hydrolysis and polycondensation reactions to form a colloidal suspension (sol) that evolves into a gel network. Careful control of pH, temperature, and reactant concentrations enables molecular-level mixing of cations. The gel is dried and thermally treated to obtain the final crystalline material.

- Hydrothermal/Solvothermal Synthesis: Precursor mixtures are heated in sealed autoclaves above the boiling point of the solvent (typically water or organic solvents), creating autogenous pressure that facilitates crystallization at temperatures significantly lower than solid-state methods.

Thin Film Deposition

For device applications, thin film fabrication employs specialized techniques:

- Pulsed Laser Deposition (PLD): A high-power laser ablates a stoichiometric target material, creating a plasma plume that deposits onto a heated single-crystal substrate under controlled oxygen pressure, enabling epitaxial growth of complex oxide films.

- Sputtering: Radio-frequency (RF) or direct-current (DC) magnetron sputtering using compound targets facilitates the deposition of uniform sulfide and oxide films over large areas.

- Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD): Volatile metal-organic precursors transport constituent elements to heated substrates where surface reactions yield crystalline films, particularly effective for halide perovskite deposition.

Materials Characterization Framework

The comprehensive characterization of inorganic solid-state materials requires a multidisciplinary approach correlating structural, compositional, and functional properties:

Diagram 1: Materials Characterization Workflow

Structural Characterization

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD): Fundamental technique for phase identification and crystal structure determination using Rietveld refinement analysis. High-temperature XRD chambers enable in situ investigation of phase transitions and thermal expansion behavior.

- Electron Microscopy: Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) provides atomic-resolution imaging and selected-area electron diffraction for local structure analysis, while scanning electron microscopy (SEM) reveals morphological features, grain sizes, and distribution of phases.

- Surface Analysis: X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) determines elemental composition and oxidation states at material surfaces, critical for understanding interfacial phenomena in battery and catalytic applications.

Functional Property Assessment

- Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): The primary method for determining ionic conductivity of solid electrolyte materials across frequency ranges from mHz to MHz, enabling deconvolution of bulk, grain boundary, and electrode contributions to total resistance.

- DC Polarization Measurements: Electronic conductivity quantification using blocking electrodes (e.g., sputtered platinum) with applied constant voltage, confirming the predominantly ionic nature of conduction (transference number approaching 1) [26].

- Cyclic Voltammetry: Determination of electrochemical stability windows by scanning electrode potential and monitoring current response, identifying oxidation and reduction limits critical for battery electrolyte operation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Solid-State Inorganic Synthesis

| Category | Specific Materials | Research Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precursor Compounds | Li₂CO₃, LiOH·H₂O, transition metal oxides (Co₃O₄, Fe₂O₃), metal sulfides (P₂S₅, GeS₂) | Source of cationic and anionic components | High purity (>99.9%) essential; stoichiometry calculations must account for hydration states and carbonate content |

| Atmosphere Control | Argon gas purifiers, oxygen/getter systems, molecular sieves | Maintain controlled synthesis environments | Critical for air-sensitive sulfides and halides; Oâ‚‚/Hâ‚‚O levels <0.1 ppm in glove boxes |

| Sintering Aids | LiF, Li₃BO₃, glass frits | Enhance densification at lower temperatures | Reduce sintering temperatures by 100-200°C; must consider interfacial reactivity |

| Characterization Standards | Silicon powder (XRD calibration), conductivity standard materials | Instrument calibration and method validation | Ensure quantitative accuracy in structural and electrical measurements |

| 1,2,3-Triisocyanatobenzene | 1,2,3-Triisocyanatobenzene, CAS:29060-61-5, MF:C9H3N3O3, MW:201.14 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Thiirane, phenyl-, (R)- | Thiirane, phenyl-, (R)-, CAS:33877-15-5, MF:C8H8S, MW:136.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Emerging Research Directions and Future Perspectives

The field of solid-state materials chemistry continues to evolve through several emerging research paradigms that redefine the potential applications of oxide, sulfide, and halide compounds. The discovery and development of dynamic non-porous materials represents one such frontier, where highly fluorinated coordination polymers demonstrate selective COâ‚‚ uptake through transient porosity rather than static pore structures [20]. This mechanism, resembling dissolution processes in perfluoroalkanes, offers new design principles for separation materials that challenge conventional porous material paradigms.

The integration of computational screening and machine learning approaches has dramatically accelerated the identification of promising new compositions within these material families. High-throughput first-principles calculations enable prediction of phase stability, ionic conductivity, and electrochemical stability before synthetic investment, guiding experimental efforts toward the most viable candidates [26]. These computational tools are particularly valuable for exploring complex multi-component systems and identifying doping strategies to enhance material performance.

Advanced interface engineering constitutes another critical research direction, especially for solid-state battery applications where interfacial resistance often limits overall device performance. Novel coating strategies, including atomic layer deposition of protective layers and the development of functional interlayers, aim to stabilize the electrode-electrolyte interface against chemical degradation and space-charge layer effects [26]. For sulfide electrolytes, interface engineering focuses on suppressing the formation of resistive decomposition products, while oxide electrolyte research emphasizes reducing grain boundary resistance through tailored sintering aids and processing conditions.

The exploration of multifunctional material systems that combine ionic conduction with additional properties such as ferroelectricity, magnetism, or luminescence opens pathways toward novel device architectures. Materials like crystalline red phosphorus with controlled phase transitions [20] and helical polymer metal-organic framework hybrids that enhance spin polarization [20] exemplify this trend toward complexity and functional integration. These advanced materials, often fabricated through kinetically-limited deposition methods that access metastable structures [20], represent the cutting edge of solid-state chemistry research.

As these research directions mature, the continued development of oxide, sulfide, and halide materials will undoubtedly address critical technological challenges in energy storage, environmental sustainability, and electronic devices. The interdisciplinary nature of this research—spanning chemistry, materials science, physics, and engineering—ensures that advances in fundamental understanding will rapidly translate to technological innovation across multiple sectors.

Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) represent a revolutionary class of crystalline porous hybrid materials composed of metal ions or clusters connected by organic linkers, forming highly ordered, extended nanoporous networks with exceptional surface areas. [27] [28] These materials are quintessential nanomaterials whose pore sizes can be precisely engineered from the nanometer to sub-nanometer scale, embodying the core nanoscience principle of controlled matter manipulation at the smallest possible scale. [28] The modular and reticular nature of MOFs provides unparalleled synthetic flexibility, allowing researchers to fine-tune chemical and physical properties by selecting specific metal nodes and organic linkers. [28] This enables precise control over pore size, shape, and chemical functionality, permitting frameworks to be tailored for interactions with specific sorbate molecules or active catalytic sites. [28]

Among MOF varieties, lanthanide-based systems (Ln-MOFs) offer particular advantages due to the higher coordination numbers of Ln(III) ions compared to transition metals, often resulting in enhanced porosity and favorable characteristics like large structural diversity, tailorable designs, high thermal stability, and immense chemical stability. [29] Hybrid MOF systems, which incorporate additional materials such as carbon-based compounds, other MOFs, or metallic particles, have emerged as particularly promising candidates for enhancing performance in gas storage and catalysis. [30] These advanced architectures are transitioning from laboratory curiosities to industrially viable materials, driven by extensive community efforts to enhance their functionality and stability, alongside breakthroughs in large-scale manufacturing. [28]

Synthesis Methodologies and Advanced Protocols

The energy required for MOF synthesis, facilitating linkage between primary building units (PBUs) and secondary building units (SBUs), can be provided through various synthesis approaches yielding contrasting structures and features. [30] The table below summarizes the key advantages and disadvantages of predominant synthesis methods.

Table 1: Comparison of MOF Synthesis Methods

| Synthesis Method | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solvothermal/Hydrothermal | Produces well-formed MOFs with controlled size and single crystals | Requires longer synthesis times (up to 24h); often uses organic solvents | Widely applicable for various MOFs including UIO, MIL, and NU series [30] |

| Non-Solvothermal (Ambient) | Energy-efficient; occurs at room temperature | Crystal shape and purity influenced by reaction temperature | MOF-5, MOF-74, HKUST-1, ZIF-7 [30] |

| Microwave-Assisted | Extremely fast (as little as 5 minutes); rapid heating | Specialized equipment required | MOF-303 for water harvesting [30] |

| Electchemical | Allows for continuous production; good film formation | Limited to electrically conductive substrates | Thin films and specific composite structures [27] |

| Mechanochemical | Solvent-free or minimal solvent; environmentally friendly | Can result in amorphous phases or impurities | Green synthesis approaches [27] |

| Resonant Acoustic Mixing (RAM) | Promising emerging technology | Still under development for MOFs | Emerging scale-up production [30] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Solvothermal Synthesis of NU-100

Principle: This method utilizes an organic solvent in a sealed vessel at elevated temperatures and autogenous pressure to facilitate the reaction between metal clusters and organic linkers, promoting crystal growth. [30]

Materials:

- Metal Precursor: ZrOCl₂·8H₂O (provides zirconium clusters)

- Organic Linker: 1,3,6,8-tetrakis(p-benzoic acid)pyrene (Hâ‚„TBAPy) or similar polytopic carboxylic acid

- Solvent: N,N-Diethylformamide (DEF) or Dimethylformamide (DMF)

- Modulator: Benzoic acid or acetic acid (to control crystal growth)

- Equipment: PTFE-lined stainless steel autoclave, laboratory oven, vacuum desiccator, centrifuge

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve the zirconium salt (e.g., 0.2 mmol) and the organic linker Hâ‚„TBAPy (0.05 mmol) in 20 mL of DEF in a glass vial under stirring.

- Modulator Addition: Add a significant excess of benzoic acid (e.g., 10 mmol) as a modulating agent to control nucleation and crystal size.

- Reaction Vessel Transfer: Transfer the homogeneous solution to a PTFE-lined autoclave and seal it tightly.

- Thermal Reaction: Place the autoclave in a preheated oven at 100-120°C for 24-48 hours to carry out the crystallization process.

- Cooling and Product Collection: After the reaction time, turn off the oven and allow it to cool naturally to room temperature.

- Washing and Activation: Collect the resulting crystals by centrifugation. Wash the crystals with fresh DMF (3 times) and then with acetone (3 times) to remove unreacted species and solvent molecules from the pores. Finally, activate the MOF by heating under vacuum (150°C for 12-24 hours) to remove all guest molecules, yielding the porous, activated NU-100. [30]

Advanced Protocol: Integration of Metal-Sulfur Active Sites

Principle: A multi-step post-synthetic modification to create highly active metal-sulfur sites within stable MOF structures, mimicking enzyme active sites for enhanced catalytic performance, particularly in hydrogenation reactions. [31]

Materials:

- MOF Host: A stable MOF with metal-chloride bonds, such as Zr-based NU-1000 or similar.

- Sulfurization Agent: Sodium sulfide (Naâ‚‚S) or hydrogen sulfide (Hâ‚‚S) gas.

- Intermediate Reagent: A base like NaOH for hydroxide intermediate formation.

- Solvents: Anhydrous N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) and methanol.

- Characterization Equipment: Single crystal X-ray diffractometer, electron diffraction analyzer.

Procedure:

- Hydroxide Installation: Activate the MOF (e.g., 100 mg) and suspend it in a 0.1M NaOH solution in DMF. Heat the mixture at 60°C for 6 hours to convert metal-chloride bonds to metal-hydroxide bonds. Wash thoroughly with DMF and methanol.

- Sulfur Conversion: Suspend the hydroxide-form MOF in a 0.1M Na₂S solution in a DMF/methanol mixture. Heat the suspension at 60°C for 12-24 hours to convert the metal-hydroxide sites to metal-sulfide sites.

- Washing and Activation: Wash the resulting sulfur-integrated MOF extensively with methanol and DMF to remove any unbound sulfur species. Activate the material under vacuum at 100°C for 12 hours.

- Structural Validation: Confirm the preservation of the framework structure and successful integration of sulfur sites using advanced structural and spectroscopic tools, including single crystal X-ray diffraction and electron diffraction analysis. [31]

Performance in Gas Storage and Catalysis

The application of MOFs in gas storage and catalysis represents one of their most promising technological pathways. Performance is highly dependent on the specific MOF structure, its surface area, pore functionality, and the incorporation of hybrid components.

Table 2: MOF Performance in Hydrogen Storage and Catalysis

| Material / System | Application | Performance Metrics | Conditions | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NU-100 [30] | H₂ Storage | Excess capacity: 9.05 wt% (gravimetric) | -196°C, 7 MPa | Highest reported H₂ storage capacity; correlates with ultra-high surface area |

| MOF-5 / MOF-177 [30] | H₂ Storage | Typical capacities: 2.4 to 7.0 wt% | -196°C | Classic examples demonstrating the relationship between surface area and capacity |

| MOF-Carbon Hybrids [30] | H₂ Storage | Improved thermal conductivity & cycling stability | Ambient to -196°C | Hybrids address limitations of pure MOFs (e.g., poor thermal conductivity) |

| Sulfur-integrated MOF [31] | Hydrogenation Catalysis | Significantly outperformed non-sulfur counterparts | Not specified | Metal-sulfur sites enable more efficient hydrogen activation; lower energy barriers |

| Ti-doped MOF [27] | Photocatalytic Hâ‚‚ Evolution | 40% increase in Hâ‚‚ evolution rate | Light irradiation | Demonstrates impact of heteroatom doping on enhancing catalytic activity |

| Ni-MOF Composites [27] | General Catalysis / Conductivity | Fivefold increase in electronic conductivity | Ambient | Improved conductivity addresses a key limitation in MOFs for electrocatalysis |

The search for higher hydrogen storage capacity must balance gravimetric and volumetric uptake. While absolute gravimetric Hâ‚‚ capacities can reach values as high as 120 mg Hâ‚‚ per g (12 wt%), volumetric Hâ‚‚ capacities peak around 40 kg Hâ‚‚ per m³ because increasing pore volume often results in reduced particle density. [30] Furthermore, while high surface area is crucial, the trend does not strictly follow Chahine's heuristic rule of 1 wt% Hâ‚‚ per 500 m² gâ»Â¹ of surface area, indicating the importance of other factors like pore size distribution and adsorbent-sorbate interactions. [30]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful research and development in MOFs for gas storage and catalysis requires a carefully selected suite of chemical reagents and characterization tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for MOF Development

| Reagent / Material Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research & Development |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Ion Precursors | Cr³âº, Fe³âº, Co²âº, Zn²⺠salts; Ln(III) salts (e.g., Tb³âº, Eu³âº) [30] [29] | Form the primary building units (PBUs) or metal nodes of the framework, defining coordination geometry. |

| Organic Linkers | Fumaric acid, succinic acid, terephthalic acid (BDC), 1,3,5-Benzenetricarboxylic acid (BTC) [30] | Bridge metal nodes to form the extended porous structure; determine pore size and functionality. |

| Solvents | N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF), Diethylformamide (DEF), Water, Acetonitrile [30] | Medium for solvothermal/non-solvothermal synthesis; influence reaction kinetics and crystal growth. |

| Modulators | Benzoic acid, Acetic acid, Trifluoroacetic acid [30] | Competitive coordination agents that control crystal growth kinetics and size, improving crystallinity. |

| Hybrid Component Additives | Carbon nanotubes, Graphene oxide, Conductive polymers, Metal nanoparticles [30] [27] | Impart new functionalities (e.g., conductivity, catalytic sites) to create superior MOF hybrid composites. |

| Post-Synthetic Modifiers | Naâ‚‚S, NaOH, Various alkyl amines [31] | Chemically alter the framework after formation to install new active sites (e.g., metal-sulfur sites). |

| Characterization Tools | Single Crystal X-ray Diffraction, Gas Sorption Analyzer, Electron Diffraction, DFT Calculations [31] | Confirm structure, porosity, and validate experimental findings with computational insights. |

| Phosphorothious acid | Phosphorothious acid, CAS:25758-73-0, MF:H3O2PS, MW:98.06 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Cycloheptane;titanium | Cycloheptane;titanium|Reagent for Research | Cycloheptane;titanium reagent for research (RUO). Explore its applications in organic synthesis and catalysis. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

MOF Synthesis and Post-Synthetic Modification Pathway

MOF Synthesis and Modification Workflow - This diagram illustrates the fundamental pathway from chemical precursors to functional MOF materials, including the critical step of post-synthetic modification for enhanced performance.

MOF Hybrid System Enhancement Mechanism

MOF Hybrid Enhancement Mechanism - This diagram maps the common limitations of base MOF materials to their corresponding hybrid solutions and the resulting performance benefits for practical applications.