Mastering TRAH SCF for Challenging Inorganic Complexes: A Comprehensive Guide for Computational Chemists

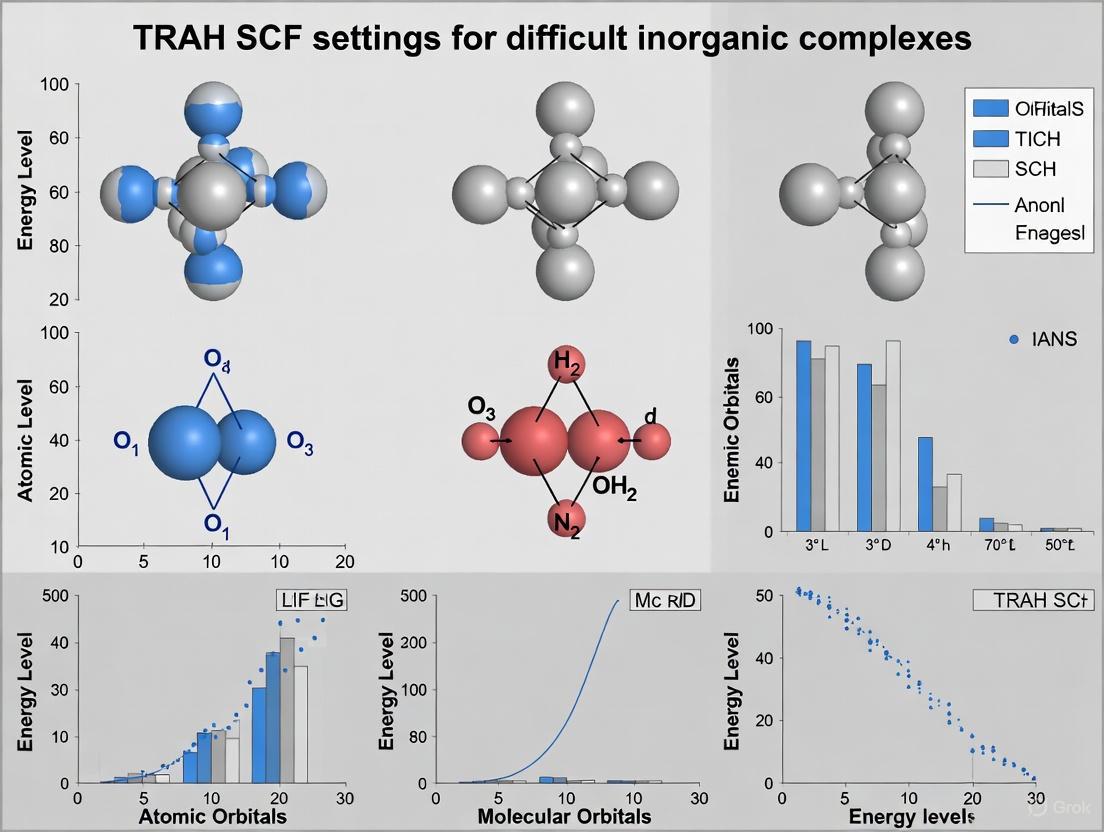

This article provides a complete guide to utilizing the Trust Region Augmented Hessian (TRAH) SCF algorithm in ORCA for achieving robust convergence in difficult inorganic and organometallic systems.

Mastering TRAH SCF for Challenging Inorganic Complexes: A Comprehensive Guide for Computational Chemists

Abstract

This article provides a complete guide to utilizing the Trust Region Augmented Hessian (TRAH) SCF algorithm in ORCA for achieving robust convergence in difficult inorganic and organometallic systems. Covering foundational principles to advanced troubleshooting, it addresses the unique challenges posed by open-shell transition metals, lanthanides, actinides, and metal clusters. The content delivers practical methodologies for configuring AutoTRAH parameters, optimizing convergence tolerances, and integrating with complementary SCF strategies. Researchers will gain actionable insights for validating electronic structures and applying these techniques to biologically relevant metal complexes in drug development and biomedical research.

Understanding SCF Convergence Challenges in Inorganic Chemistry

The Critical Nature of SCF Convergence in Transition Metal Complexes

Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence represents a fundamental challenge in the electronic structure calculations of transition metal complexes. These systems, characterized by open-shell configurations, near-degenerate states, and significant static correlation, frequently defy convergence with standard algorithms [1]. The reliability of subsequent computational analyses—from geometry optimizations to prediction of spectroscopic properties—hinges upon achieving a fully converged SCF solution. Within the context of advanced SCF methodologies, the Trust Region Augmented Hessian (TRAH) approach has emerged as a robust second-order convergence algorithm particularly suited for problematic inorganic systems where conventional methods falter [1]. This application note details the critical aspects of SCF convergence and provides structured protocols for employing TRAH-based techniques to ensure computational reliability for challenging transition metal complexes.

The SCF Convergence Challenge in Transition Metal Chemistry

Fundamental Obstacles

Transition metal complexes introduce specific complications for SCF procedures:

- Open-shell character: Unpaired electrons lead to multiple spin states and potential symmetry breaking [1].

- Static correlation: Near-degeneracy of electronic configurations necessitates multi-reference approaches, complicating single-determinant methods [2].

- Metal-ligand bonding: Complex bonding scenarios involving significant charge transfer create challenging potential energy surfaces [3].

- Dense orbital manifolds: The presence of d- and f-orbitals creates high density of states with small HOMO-LUMO gaps [2].

Consequences of Poor Convergence

Erroneous SCF convergence directly impacts computational predictions:

- Elastic constants may show unacceptable deviations exceeding 20% with loose criteria [4].

- Reaction barrier heights become unreliable for catalytic cycle prediction.

- Molecular properties including spin densities and vibrational frequencies show pathological behavior [1].

- Subsequent correlated calculations (MP2, CCSD, CASPT2) build upon flawed reference wavefunctions [2].

Quantitative SCF Convergence Criteria

Standard Tolerance Settings

Table 1: Standard SCF Convergence Tolerance Settings in ORCA [5]

| Criterion | Loose | Medium | Strong | Tight | VeryTight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TolE (Energy Change) | 1e-5 | 1e-6 | 3e-7 | 1e-8 | 1e-9 |

| TolMaxP (Max Density) | 1e-3 | 1e-5 | 3e-6 | 1e-7 | 1e-8 |

| TolRMSP (RMS Density) | 1e-4 | 1e-6 | 1e-7 | 5e-9 | 1e-9 |

| TolErr (DIIS Error) | 5e-4 | 1e-5 | 3e-6 | 5e-7 | 1e-8 |

| TolG (Orbital Gradient) | 1e-4 | 5e-5 | 2e-5 | 1e-5 | 2e-6 |

Recommended Tolerances for Transition Metals

For transition metal complexes, TightSCF settings or stricter are generally recommended [5]:

TRAH-SCF Methodology

Algorithm Fundamentals

The Trust Region Augmented Hessian (TRAH) approach represents a superior second-order convergence algorithm that automatically activates in ORCA when standard DIIS procedures struggle [1]. Unlike first-order methods, TRAH utilizes approximate second derivatives to generate more reliable step directions, particularly valuable when the energy hypersurface contains multiple minima or saddle points.

Table 2: TRAH-SCF Control Parameters for Pathological Cases

| Parameter | Default | Aggressive | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| AutoTRAHTOl | 1.125 | 1.5 | Orbital gradient threshold for TRAH activation |

| AutoTRAHIter | 20 | 15 | Iterations before interpolation |

| AutoTRAHNInter | 10 | 15 | Iterations used in interpolation |

| MaxIter | 125 | 500-1500 | Maximum SCF iterations |

TRAH Activation Protocol

Experimental Protocols for Challenging Systems

Protocol 1: Standard TRAH-SCF for Open-Shell Complexes

Application: High-spin transition metal complexes, radical species

Procedure:

- Initial Calculation Setup

- Employ

! TightSCFkeyword for appropriate tolerances [5] - Use

! TRAHto explicitly enable the trust-region algorithm - For open-shell systems, specify

! UKSand appropriate spin multiplicity

- Employ

TRAH Parameter Optimization

Convergence Monitoring

- Monitor orbital gradient norms for TRAH activation

- Verify all convergence criteria (TolE, TolMaxP, TolRMSP) are satisfied

- Perform stability analysis upon convergence

Protocol 2: Multi-Layer Approach for Pathological Cases

Application: Metal clusters, multi-metallic systems, strongly correlated materials [2]

Procedure:

- Initial Approximation

- Begin with BP86/def2-SVP or HF/def2-SVP for preliminary convergence [1]

- Use

! SlowConvor! VerySlowConvfor enhanced damping - Employ level-shifting if oscillations persist:

Shift 0.1 ErrOff 0.1

Wavefunction Transfer

- Utilize

! MOReadto transfer orbitals to higher-level calculation - Specify orbital file:

%moinp "previous_calc.gbw"

- Utilize

Final TRAH Refinement

- Activate TRAH with aggressive settings

- Implement large DIIS subspace:

DIISMaxEq 15-40[1] - Consider frequent Fock builds:

directresetfreq 1-5for numerical stability

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for SCF Convergence

| Tool/Technique | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| TRAH-SCF | Robust second-order convergence | Primary algorithm for difficult cases [1] |

| DIISMaxEq (15-40) | Expanded DIIS subspace | Pathological systems with slow convergence [1] |

| DirectResetFreq (1-15) | Fock matrix rebuild frequency | Reduces numerical noise in difficult cases [1] |

| MORead | Orbital transfer from preliminary calculation | Provides improved initial guess [1] |

| Stability Analysis | Verifies solution is true minimum | Essential for open-shell singlets [5] |

| Level Shifting (0.05-0.2) | Artificial orbital energy separation | Suppresses oscillations in early iterations [1] |

Case Study: Mn₂Si₁₂ Cluster

System Characterization

The Mn₂Si₁₂ cluster exemplifies challenges in transition metal computational chemistry [2]:

- Strong static correlation in both Mn-Si bonds ('in-out correlation') and Mn-Mn interactions ('up-down correlation')

- Multiconfigurational character necessitating advanced active space approaches

- High-symmetry (C₆ᵥ) complications requiring careful orbital partitioning

TRAH-SCF Implementation

Computational Recipe:

Troubleshooting Guide

Common Failure Modes and Solutions

Table 4: SCF Convergence Failure Diagnosis and Resolution

| Symptom | Probable Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Large initial oscillations | Inadequate damping, poor initial guess | Enable ! SlowConv, use PModel guess, or level shifting [1] |

| Convergence trailing near completion | DIIS extrapolation issues | Activate SOSCF with SOSCFStart 0.00033 or switch to TRAH [1] |

| TRAH slow convergence | Excessive second-order steps | Adjust AutoTRAHTOl to 1.5, increase AutoTRAHIter [1] |

| "HUGE, UNRELIABLE STEP" in SOSCF | Numerical instability in orbital optimization | Disable SOSCF with ! NOSOSCF or implement stricter damping [1] |

| Persistent non-convergence | Linear dependence, numerical noise | Increase grid size, use directresetfreq 1, remove linear dependencies [1] |

SCF convergence in transition metal complexes remains a critical challenge with direct implications for computational reliability. The TRAH algorithm represents a significant advancement in addressing these difficulties through robust second-order convergence methodology. By implementing the protocols, tolerance settings, and troubleshooting strategies outlined in this application note, computational researchers can achieve reliable SCF convergence even for the most challenging inorganic systems. Proper attention to convergence criteria and algorithm selection ensures subsequent property calculations and spectroscopic predictions build upon a firm theoretical foundation.

Theoretical Foundation of the TRAH Algorithm

The Trust Region Augmented Hessian (TRAH) algorithm represents a significant advancement in self-consistent field (SCF) convergence methodology, particularly for challenging electronic structure systems. Implemented in ORCA since version 5.0, TRAH functions as a robust second-order converger that automatically activates when the conventional DIIS-based SCF procedures encounter difficulties. Unlike first-order methods that may oscillate or converge slowly for problematic systems, TRAH employs a more sophisticated mathematical approach that guarantees convergence to a true local minimum on the orbital rotation surface, though not necessarily the global minimum [5] [6]. This characteristic is particularly valuable for ensuring the physical meaningfulness of the obtained solution.

The algorithm operates within a trust region framework, which carefully controls the step size during orbital optimization to prevent unstable updates that can derail convergence. When the regular DIIS-SCF procedure struggles to converge – a common occurrence with open-shell transition metal complexes and other electronically challenging systems – ORCA automatically switches to the TRAH algorithm [1]. This transition ensures that calculations proceed toward a physically valid solution rather than oscillating indefinitely or diverging. The mathematical rigor of the second-order approach makes TRAH particularly effective for systems with near-degenerate orbital energies, multireference character, or complex spin coupling, which often plague conventional SCF methods.

Implementation and Activation Protocols

Automatic TRAH Activation Parameters

ORCA's implementation of TRAH features sophisticated automatic activation mechanisms that trigger the algorithm when convergence problems are detected. The default settings provide a balance between efficiency and robustness, but researchers can fine-tune these parameters for specific systems:

Table 1: AutoTRAH Configuration Parameters for Difficult Systems

| Parameter | Default Value | Recommended Range | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

AutoTRAH |

true |

true/false |

Enables automatic TRAH activation |

AutoTRAHTol |

1.125 | 1.1-1.3 | Threshold for TRAH activation (lower values trigger earlier) |

AutoTRAHIter |

20 | 15-30 | Iteration count before interpolation begins |

AutoTRAHNInter |

10 | 5-20 | Number of interpolation iterations |

The activation threshold (AutoTRAHTol) determines how quickly ORCA switches to TRAH when convergence problems are detected. For particularly problematic systems, such as iron-sulfur clusters or antiferromagnetically coupled dinuclear complexes, reducing this value to 1.1 can trigger TRAH activation earlier in the process, potentially saving computational time [1]. The AutoTRAHIter parameter controls how many iterations are performed before interpolation methods engage, while AutoTRAHNInter determines the granularity of the interpolation process.

Manual TRAH Control

For maximum control over the convergence process, researchers can explicitly enforce TRAH usage or disable it entirely. The !TRAH keyword forces ORCA to use the Trust Region Augmented Hessian method from the beginning of the SCF procedure, bypassing the initial DIIS iterations entirely [5]. This approach can be beneficial when prior knowledge indicates that a system will be difficult to converge. Conversely, the !NoTRAH keyword disables the algorithm completely, which may be desirable for benchmarking or for systems where TRAH unexpectedly slows down convergence [1].

Configuration and Convergence Criteria

Convergence Tolerance Settings

Proper configuration of convergence tolerances is essential for balancing computational efficiency with accuracy requirements. TRAH adheres to the same convergence criteria as standard SCF methods, but its second-order nature often enables it to achieve tighter convergence more reliably. The following table summarizes key tolerance parameters:

Table 2: SCF Convergence Tolerance Criteria for TRAH Calculations

| Criterion | LooseSCF | NormalSCF | TightSCF | VeryTightSCF | Physical Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

TolE |

1e-5 | 1e-6 | 1e-8 | 1e-9 | Energy change between cycles |

TolRMSP |

1e-4 | 1e-6 | 5e-9 | 1e-9 | RMS density change |

TolMaxP |

1e-3 | 1e-5 | 1e-7 | 1e-8 | Maximum density change |

TolErr |

5e-4 | 1e-5 | 5e-7 | 1e-8 | DIIS error convergence |

TolG |

1e-4 | 5e-5 | 1e-5 | 2e-6 | Orbital gradient convergence |

TolX |

1e-4 | 5e-5 | 1e-5 | 2e-6 | Orbital rotation angle |

For transition metal complexes and other challenging inorganic systems, !TightSCF convergence criteria are often recommended as they provide high accuracy without being computationally prohibitive [5] [6]. The TolE parameter (energy change tolerance) of 1e-8 Hartree and TolRMSP (RMS density change) of 5e-9 in TightSCF settings ensure that the electronic structure is fully relaxed, which is particularly important for calculating reliable molecular properties and spectroscopic parameters [5].

Advanced SCF Configuration

The ConvCheckMode parameter determines how strictly convergence criteria are applied and is particularly relevant for TRAH calculations:

ConvCheckMode 0: All convergence criteria must be satisfied (most rigorous)ConvCheckMode 1: Calculation stops if any single criterion is met (not recommended for production work)ConvCheckMode 2: Default setting; checks change in total energy and one-electron energy [5]

For TRAH calculations targeting difficult inorganic complexes, ConvCheckMode 0 ensures the highest quality results, as it requires all convergence metrics to be satisfied simultaneously. Additionally, the ConvForced flag can be set to enforce complete SCF convergence before proceeding to subsequent calculation stages, which is particularly important for property calculations and spectroscopic predictions [1].

Practical Application to Challenging Inorganic Systems

Protocol for Open-Shell Transition Metal Complexes

Open-shell transition metal complexes represent one of the most challenging classes of systems for SCF convergence due to their high density of near-degenerate states and complex electron correlation effects. The following step-by-step protocol optimizes TRAH for these systems:

Initial System Assessment: Check spin contamination by examining the 〈S²〉 expectation value and analyze unrestricted corresponding orbitals (UCO) to verify the physical reasonableness of the solution [6].

Guess Orbital Generation: Employ the

!MOReadkeyword to import orbitals from a converged calculation of a similar geometry or electronic state. Alternatively, use!PAtom,!Hueckel, or!HCoreas alternative initial guesses when the defaultPModelguess fails [1].TRAH Configuration:

Fallback Strategy: If TRAH convergence remains problematic, employ the

!SlowConvor!VerySlowConvkeywords with increased damping, possibly combined with level-shifting techniques [1].

Protocol for Multinuclear Metal Clusters

Multinuclear metal clusters, such as iron-sulfur proteins and polynuclear transition metal complexes, present exceptional challenges due to their complex spin coupling and delocalized electronic structures:

Gradual Convergence Approach: Begin with a reduced basis set (e.g., def2-SVP) and lower convergence criteria (

!LooseSCF) to generate initial orbitals, then refine with larger basis sets and tighter criteria [1].Enhanced TRAH Configuration:

Electronic State Manipulation: Converge a one- or two-electron oxidized/reduced state (preferably closed-shell) and use these orbitals as the starting point for the target electronic state via the

!MOReadkeyword [1].Stability Analysis: After convergence, perform SCF stability analysis to verify that the solution represents a true minimum rather than a saddle point on the orbital rotation surface [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential TRAH Computational Reagents

Table 3: Key Computational Resources for TRAH-SCF Methodology

| Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

!TRAH |

ORCA Keyword | Enables Trust Region Augmented Hessian algorithm | Primary TRAH activation for difficult convergence cases |

!NoTRAH |

ORCA Keyword | Disables TRAH algorithm | Benchmarking or when TRAH underperforms |

AutoTRAHTol |

Numerical Parameter | Controls sensitivity for automatic TRAH activation | Fine-tuning automatic switching (lower values = earlier activation) |

!MORead |

Initial Guess Strategy | Reads orbitals from previous calculation | Providing improved starting orbitals for challenging systems |

!SlowConv |

Convergence Aid | Increases damping for oscillating systems | Stabilizing initial SCF iterations before TRAH activation |

DIISMaxEq |

DIIS Parameter | Increases number of remembered Fock matrices (default=5) | Difficult cases requiring more DIIS history (set to 15-40) [1] |

directresetfreq |

Numerical Precision | Controls Fock matrix rebuild frequency (default=15) | Reducing numerical noise (set to 1-5 for problematic cases) [1] |

!TightSCF |

Convergence Level | Sets tighter convergence tolerances | High-accuracy production calculations |

Troubleshooting and Performance Optimization

Diagnostic Workflow for TRAH Convergence Issues

When TRAH encounters convergence difficulties, a systematic diagnostic approach is essential:

Performance Optimization Strategies

While TRAH provides superior convergence robustness, it typically requires more computational resources per iteration than standard DIIS. Several strategies can optimize this trade-off:

Delayed TRAH Activation: For systems where initial DIIS convergence is rapid but later stages stagnate, set

AutoTRAHTolto higher values (1.2-1.3) to allow more DIIS iterations before TRAH activation [1].Hybrid DIIS-TRAH Protocol: Leverage the efficiency of DIIS for initial convergence and the robustness of TRAH for final refinement. This approach maximizes computational efficiency while maintaining convergence reliability.

Orbital Pre-convergence: For exceptionally difficult systems, pre-converge a related electronic state or simplified geometry using faster methods, then use these orbitals as the starting point for the target TRAH calculation.

Integral Direct Methods: When using direct SCF methods, ensure that the integral accuracy (controlled by

ThreshandTCutparameters) exceeds the SCF convergence criteria, as insufficient integral precision will prevent convergence regardless of the algorithm employed [5].

The Trust Region Augmented Hessian algorithm represents a substantial advancement in SCF convergence technology, particularly for challenging inorganic complexes that defy conventional DIIS-based approaches. Its robust second-order optimization framework guarantees convergence to true local minima on the orbital rotation surface, ensuring physically meaningful solutions for electronically complex systems. When properly configured with appropriate convergence criteria and activation parameters, TRAH enables researchers to tackle previously intractable systems including open-shell transition metal complexes, multinuclear clusters, and systems with strong static correlation. The integration of TRAH into computational workflows for inorganic chemistry and drug development involving metalloenzymes provides a powerful tool for reliable electronic structure determination of the most challenging molecular systems.

Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence presents significant challenges in computational inorganic chemistry, particularly when studying systems with open-shell configurations, metallic character, or complex electronic structures. These systems, which include many transition metal complexes, organometallics, and solid-state materials, often exhibit small HOMO-LUMO gaps, near-degenerate electronic states, and strong electron correlation effects that complicate the convergence of quantum chemical calculations. Within the context of developing TRAH (Trust-Region Augmented Hessian) SCF settings for difficult inorganic complexes, understanding these failure scenarios is fundamental to developing robust computational protocols. The physical origins of these convergence problems often stem from intrinsic electronic properties rather than purely numerical issues, requiring physically-informed solutions that go beyond standard algorithmic adjustments.

Physical and Numerical Roots of SCF Failures

Fundamental Electronic Structure Challenges

The convergence behavior of the SCF procedure is intimately connected to the electronic structure of the system under investigation. Several physically meaningful scenarios can lead to convergence failures:

Small HOMO-LUMO Gap: Systems with small energy separation between highest occupied and lowest unoccupied molecular orbitals present fundamental challenges. When the HOMO-LUMO gap becomes too small, even minor fluctuations in the SCF procedure can cause electrons to oscillate between near-degenerate frontier orbitals, preventing convergence. This oscillation manifests as large changes in the density matrix and correspondingly large energy fluctuations (typically 10⁻⁴ to 1 Hartree) between cycles. Metallic systems or those with nearly degenerate electronic states are particularly susceptible to this issue [7].

Charge Sloshing: In systems with high polarizability (inversely related to HOMO-LUMO gap), small errors in the Kohn-Sham potential can induce large distortions in the electron density. These distortions can create even larger errors in subsequent iterations, leading to a diverging SCF process. This "charge sloshing" phenomenon typically produces oscillating SCF energies with moderate amplitude and qualitatively correct orbital occupation patterns that nevertheless fail to converge [7].

Incorrect Initial Guess and Symmetry Constraints: Poor initial density guesses, particularly for systems with unusual charge or spin states or metal centers, can steer the SCF toward unphysical solutions. Additionally, imposing incorrectly high symmetry constraints can artificially create zero HOMO-LUMO gaps, preventing convergence even when the underlying electronic structure would be manageable with proper symmetry treatment [7].

Numerical Precision and Basis Set Issues

Beyond physical electronic structure challenges, numerical and technical considerations can also impede SCF convergence:

Basis Set Linear Dependence: When basis functions become nearly linearly dependent, the overlap matrix develops very small eigenvalues that jeopardize numerical stability. This problem is particularly prevalent in systems with diffuse basis functions or closely-spaced atoms, and manifests as wildly oscillating or unrealistically low SCF energies with qualitatively wrong occupation patterns [8] [7].

Numerical Grid and Integration Errors: Insufficiently accurate numerical integration grids can introduce noise into the SCF procedure. This typically produces energy oscillations with very small magnitude (<10⁻⁴ Hartree) despite qualitatively correct orbital occupations. Heavy elements often require higher-quality integration grids for stable convergence [8] [7].

Table 1: Diagnostic Signatures of Common SCF Failure Modes

| Failure Mechanism | Energy Oscillation Amplitude | Orbital Occupation Pattern | Typical System Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small HOMO-LUMO Gap | 10⁻⁴ to 1 Hartree | Obviously wrong, oscillating | Metallic systems, near-degenerate states |

| Charge Sloshing | 10⁻⁴ to 10⁻² Hartree | Qualitatively correct but oscillating | Highly polarizable systems, small-gap insulators |

| Basis Set Linear Dependence | >1 Hartree | Qualitatively wrong | Diffuse basis sets, closely-spaced atoms |

| Numerical Noise | <10⁻⁴ Hartree | Qualitatively correct | Heavy elements, insufficient integration grids |

Protocol for Systematic SCF Troubleshooting

Initial Diagnostic Workflow

A systematic approach to diagnosing and addressing SCF convergence issues begins with careful analysis of the output and calculation behavior. The following workflow provides a logical diagnostic procedure:

Initial Assessment and Conservative Parameter Adjustment

When facing SCF convergence issues, beginning with conservative parameter adjustments provides a stable foundation:

- Reduce SCF Mixing Parameters: Decrease the mixing parameter to more conservative values to dampen oscillations: Simultaneously, consider reducing the DIIS subspace dimension:

Convergence Degenerate Default ! Improved handling of near-degenerate states End [8]

NumericalQuality Good

RadialDefaults NR 10000 ! More radial points End [8] ```Specialized Solutions for Specific Failure Scenarios

Addressing Metallic State Convergence

Inorganic systems with metallic character or those that pass through metallic states during SCF iterations present particular challenges. These systems often benefit from electronic smearing techniques and specialized SCF algorithms:

Electronic Smearing: Applying a finite electronic temperature spreads orbital occupations, preventing oscillations between nearly degenerate states:

For geometry optimizations, this can be automated to use higher temperatures initially and lower temperatures as convergence approaches [8].

Alternative SCF Algorithms: The MultiSecant method provides a robust alternative to DIIS at similar computational cost:

For particularly stubborn cases, the LISTi method may be effective despite increased cost per iteration [8].

Level Shifting (LEVSHIFT): Artificial separation of occupied and virtual orbitals can prevent convergence to unphysical metallic states in inherently insulating systems [9].

Handling Open-Shell and Strongly Correlated Systems

Open-shell systems, particularly those containing transition metals or actinides, exhibit complex electronic structures with significant multireference character. Specialized approaches are required for these challenging cases:

Initial Guess Strategy: For open-shell transition metal complexes, initial guesses derived from atomic potentials may be insufficient. Consider fragment-based initial guesses or initial calculations with reduced basis sets to generate improved starting densities [7].

Basis Set Management: For systems with near-linear dependence in the basis set, apply confinement to reduce diffuseness of basis functions:

Alternatively, consider removing the most diffuse basis functions, particularly for highly coordinated atoms [8].

Stepwise Convergence Protocol: Begin with a minimal basis set (SZ) to establish initial convergence, then restart with larger basis sets using the converged density as starting point [8].

Table 2: Specialized Solution Matrix for SCF Failure Scenarios

| Failure Scenario | Primary Solution | Alternative Approach | Key Parameters to Adjust |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metallic State Convergence | Electronic Smearing | MultiSecant Algorithm | ElectronicTemperature, SCF%Method |

| Small HOMO-LUMO Gap | Level Shifting | Reduced Mixing | LEVSHIFT, SCF%Mixing |

| Charge Sloshing | Conservative DIIS | LISTi Method | Diis%Dimix, Diis%Variant |

| Basis Set Linear Dependence | Confinement | Basis Set Truncation | Confinement%Radius |

| Numerical Noise | Enhanced Grids | Tightened Thresholds | NumericalQuality, RadialDefaults%NR |

| Open-Shell Convergence | Improved Initial Guess | Stepwise Protocol | Initial guess strategy |

Advanced TRAH-Specific Implementation Strategies

Within the context of developing TRAH SCF settings for difficult inorganic complexes, several advanced strategies show particular promise:

Adaptive Convergence Criteria: Implement geometry-dependent convergence criteria that tighten as the optimization progresses:

This approach applies looser criteria during initial geometric distortions and tighter criteria near convergence [8].

State-Tracking Algorithms: For systems with near-degenerate electronic states, implement algorithms that track state identity across SCF iterations to prevent root flipping and ensure consistency.

Hybrid Smearing Protocols: Combine electronic temperature approaches with adaptive level shifting to maintain state identity while preventing metallic state convergence.

Case Studies and Experimental Validation

Case Study: Actinide Metallocene Complexes

Computational studies of bent actinide metallocenes (An(COTbig)₂, where An = Th, U, Np, Pu) illustrate the challenges in modeling complex f-element systems with strong electron correlation effects. These systems feature significant 5f orbital participation in bonding and complex electronic structures that challenge standard SCF procedures [10].

Successful Computational Protocol:

- Functional Selection: Employ hybrid functionals (PBE0) with sufficient exact exchange to properly capture multireference character

- Stable Initial Guess: Utilize fragment-based initial guesses from simplified molecular models

- Conservative Convergence: Apply reduced mixing parameters (SCF%Mixing = 0.05-0.1) with DIIS subspace management

- Enhanced Numerical Integration: Implement high-quality integration grids (NumericalQuality Good) to properly capture f-orbital electron density

Case Study: Transition Metal Redox Properties

Accurate prediction of reduction potentials and electron affinities for transition metal complexes represents a stringent test of SCF stability and accuracy. Recent benchmarking studies comparing neural network potentials, density functional theory, and semiempirical methods reveal the importance of robust SCF procedures for charge-related properties [11].

Optimal Protocol for Redox Properties:

- Consistent Structure Preparation: Geometry optimization at consistent theory level for both oxidized and reduced states

- Solvation Treatment: Implicit solvation models (CPCM-X) applied consistently across redox couples

- Convergence Assurance: Application of moderate electronic smearing (kT = 0.001-0.01 Hartree) to ensure stable convergence

- Validation: Comparison with experimental redox potentials to identify systematic biases

Research Reagent Solutions for Electronic Structure Studies

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Challenging Inorganic Systems

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| LIBXC Functional Library | Exchange-correlation functionals | GGA calculations requiring analytical stress |

| DIIS Algorithm | SCF convergence acceleration | Standard convergence acceleration |

| MultiSecant Method | Alternative SCF convergence | Systems where DIIS fails |

| LISTi Method | Enhanced convergence variant | Problematic cases with charge sloshing |

| CPCM-X Solvation Model | Implicit solvation treatment | Reduction potential calculations |

| Numerical Atomic Orbitals | Basis set for core electron description | Systems requiring full electron treatment |

| Confinement Potentials | Basis set range control | Systems with linear dependence issues |

Successfully managing SCF convergence in challenging inorganic systems requires both understanding the physical origins of convergence failures and implementing targeted technical solutions. The protocols outlined herein provide a systematic approach to diagnosing and addressing the most common failure scenarios encountered with open-shell systems, metallic states, and complex electronic structures.

For researchers implementing TRAH SCF settings for difficult inorganic complexes, the following prioritized implementation strategy is recommended:

- Begin with Conservative Defaults: Initiate calculations with reduced mixing parameters (0.05-0.1) and explicit degenerate state handling

- Implement Diagnostic Monitoring: Carefully monitor SCF energy oscillation patterns and orbital occupations to identify failure mechanisms early

- Apply Scenario-Specific Solutions: Implement targeted solutions based on diagnostic outcomes rather than generic approaches

- Validate with Stepwise Protocol: For particularly challenging systems, employ a stepwise approach beginning with minimal basis sets and simplified models

This structured approach to SCF convergence facilitates more reliable computational studies of complex inorganic systems, enabling accurate prediction of electronic properties, redox behavior, and spectroscopic characteristics across a broad range of scientifically and technologically important materials.

How TRAH Differs from Traditional DIIS for Problematic Systems

Achieving self-consistent field (SCF) convergence represents a fundamental challenge in computational chemistry calculations, particularly for problematic systems such as open-shell transition metal complexes and inorganic clusters [1]. The SCF procedure seeks to solve the Hartree-Fock or Kohn-Sham equations iteratively, with convergence difficulties arising from complex electronic structures, near-degenerate orbital energies, and strong electron correlation effects [6]. Traditional approaches, primarily the Direct Inversion of the Iterative Subspace (DIIS) method, have served as the cornerstone for SCF convergence for decades. However, DIIS often exhibits limitations for pathological cases, including oscillatory behavior, slow convergence, or complete failure to converge [1].

The Trust Region Augmented Hessian (TRAH) algorithm represents a significant advancement in SCF convergence technology, particularly implemented in quantum chemistry packages like ORCA [1]. This application note examines the fundamental differences between TRAH and traditional DIIS approaches, providing quantitative comparisons, detailed protocols, and practical guidance for researchers investigating difficult inorganic complexes. Understanding these methodological distinctions is crucial for computational chemists and drug development professionals working with challenging electronic structures, as proper algorithm selection can dramatically impact computational efficiency and reliability.

Fundamental Algorithmic Differences: TRAH vs. DIIS

Theoretical Foundations and Implementation

The TRAH and DIIS algorithms approach the SCF convergence problem from fundamentally different perspectives. DIIS operates as an extrapolation method that minimizes the error vector between successive Fock or Kohn-Sham matrices, utilizing information from previous iterations to predict improved density matrices [1]. While highly effective for well-behaved systems, DIIS relies heavily on the quality of initial guesses and can diverge when faced with strong orbital mixing or near-degeneracies. In contrast, TRAH implements a second-order convergence strategy that constructs and diagonalizes an augmented Hessian matrix within a trusted region, effectively navigating complex potential energy surfaces by following the exact energy landscape rather than extrapolating from previous points [1].

The mathematical framework of TRAH ensures more robust convergence for problematic systems by directly minimizing the total energy with respect to orbital rotations. This approach naturally handles cases where the orbital gradient is large and the Hessian matrix contains significant off-diagonal elements. ORCA's implementation features an auto-TRAH mechanism that automatically activates the TRAH algorithm when the standard DIIS-based SCF converger encounters difficulties, providing a seamless transition between methods based on convergence behavior [1].

Performance Characteristics and System Dependence

Table 1: Algorithm Characteristics Comparison

| Feature | Traditional DIIS | TRAH |

|---|---|---|

| Algorithm Type | First-order extrapolation | Second-order direct minimization |

| Computational Cost | Lower per iteration | Higher per iteration |

| Memory Requirements | Moderate | Higher |

| Convergence Reliability | Excellent for well-behaved systems | Superior for difficult cases |

| Handling of Near-Degeneracies | Poor | Excellent |

| Initial Guess Dependence | High | Moderate |

| Auto-activation in ORCA | Default initial method | Activates when DIIS struggles |

The performance characteristics of each algorithm demonstrate clear trade-offs. Traditional DIIS exhibits lower computational cost per iteration and has served as the default method for closed-shell organic molecules where convergence is typically straightforward [1]. TRAH, while more computationally expensive per iteration, provides superior convergence reliability for challenging systems including open-shell transition metal compounds, metal clusters, and systems with diffuse basis functions [1]. This reliability translates to better overall efficiency for problematic cases where DIIS would require extensive manual tuning or might fail entirely.

Quantitative Performance Analysis

Convergence Metrics and Efficiency

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics for SCF Algorithms

| Performance Metric | DIIS | TRAH |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Iteration Count | Highly variable | More consistent |

| Iteration Time Ratio | 1.0 (reference) | 1.5-3.0x |

| Success Rate (Simple Systems) | >95% | >98% |

| Success Rate (Complex TM Systems) | 40-70% | 85-95% |

| Orbital Gradient Tolerance | 1e-5 (TightSCF) | 1e-5 (TightSCF) |

| Energy Convergence Tolerance | 1e-8 (TightSCF) | 1e-8 (TightSCF) |

The quantitative comparison reveals TRAH's significant advantage for challenging systems. While TRAH iterations are computationally more expensive, the algorithm typically achieves convergence in fewer iterations for problematic cases, offsetting the per-iteration cost premium. For particularly difficult systems such as iron-sulfur clusters, TRAH often represents the only practical path to convergence without extensive manual intervention [1]. The robust nature of TRAH also reduces researcher time spent on convergence troubleshooting, representing an additional efficiency gain not captured in raw computational metrics.

System-Specific Performance Profiles

Performance characteristics vary substantially based on system composition and electronic structure. For closed-shell organic molecules with minimal multireference character, DIIS typically converges rapidly and represents the most efficient option [1]. Open-shell transition metal complexes exhibit intermediate behavior, with DIIS often struggling with convergence while TRAH provides reliable performance. For truly pathological systems such as metal clusters, particularly those with multiple metal centers and significant spin polarization, TRAH frequently becomes the only viable option [1]. Systems with large basis sets or diffuse functions also benefit from TRAH's robust handling of linear dependence and near-degeneracy issues.

Computational Workflow and Decision Framework

SCF Algorithm Selection Workflow

Protocol: Standard SCF Convergence Procedure

Objective: Achieve SCF convergence for inorganic complexes using an efficient hierarchical approach.

Materials and Software:

- ORCA quantum chemistry package (version 5.0 or higher)

- Molecular structure file

- Appropriate basis set and functional selection

Procedure:

- Initial Calculation Setup

- Begin with default DIIS-SOSCF algorithm

- Use appropriate functional (e.g., B3LYP, PBE0, TPSSh) for inorganic complexes

- Select basis set matched to system requirements

- For open-shell systems, employ unrestricted formalism

Convergence Monitoring

- Monitor SCF iterations for progress

- Identify oscillatory behavior or stagnation

- Allow auto-TRAH to activate automatically when needed (default in ORCA 5.0+)

Manual Intervention Protocol

- If automatic convergence fails, manually specify TRAH algorithm using

!TRAHkeyword - For extreme cases, implement specialized TRAH parameters:

- If automatic convergence fails, manually specify TRAH algorithm using

Validation and Verification

- Confirm convergence meets desired tolerances

- Verify physical reasonableness of molecular orbitals

- For open-shell systems, check spin contamination values

Protocol: Advanced TRAH Configuration for Pathological Systems

Objective: Overcome severe convergence challenges in complex inorganic clusters.

Materials and Software:

- ORCA with specialized SCF configuration

- High-performance computing resources

- Molecular model building software

Procedure:

- Direct TRAH Activation

- Bypass DIIS entirely using

!TRAHkeyword - Combine with convergence aids:

- Bypass DIIS entirely using

Parameter Optimization

- Adjust trust region parameters for specific system types

- Modify iteration limits for exceptionally difficult cases

- Fine-tune integral screening thresholds

Convergence Acceleration Techniques

- Utilize molecular orbital read from preliminary calculation:

- Employ alternative initial guesses (

PAtom,Hueckel, orHCore) - Converge oxidized/reduced state orbitals as starting point

Diagnostic and Verification Steps

- Perform SCF stability analysis

- Examine orbital rotation gradients

- Verify convergence across multiple criteria

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for SCF Convergence

| Tool/Keyword | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| ORCA TRAH Implementation | Second-order SCF convergence | Primary algorithm for difficult systems |

| DIIS-SOSCF Combination | First-order extrapolation with orbital optimization | Default for well-behaved systems |

| !SlowConv/!VerySlowConv | Increases damping for oscillatory cases | Systems with large initial fluctuations |

| !KDIIS | Alternative DIIS implementation | Sometimes faster convergence |

| AutoTRAH Parameters | Controls automatic TRAH activation | Fine-tuning automatic algorithm switching |

| MORead | Provides initial orbital guess | Overcoming poor initial guesses |

| SCF Stability Analysis | Checks solution stability | Identifying false convergence |

Troubleshooting and Optimization Guidelines

Common Convergence Issues and Solutions

Problem: Persistent oscillations in early SCF iterations. Solution: Implement

!SlowConvkeyword with TRAH to increase damping factors.Problem: TRAH convergence unacceptably slow. Solution: Adjust

AutoTRAHTOlparameter to delay TRAH activation, allowing DIIS more attempts for simpler convergence.Problem: Suspected false convergence or unstable solution. Solution: Perform SCF stability analysis; consider alternative initial guesses or molecular symmetry breaking.

Problem: Excessive memory usage with TRAH for large systems. Solution: Utilize direct SCF capabilities; adjust

DirectResetFreqparameter to balance memory and performance.

Performance Optimization Strategies

Optimizing SCF convergence requires balancing computational cost with reliability. For high-throughput screening of similar inorganic complexes, invest initial effort in identifying optimal algorithm settings, then apply consistently across the series. For single complex investigation, begin with defaults and escalate to TRAH only as needed. When working with metal clusters or multinuclear complexes, start directly with TRAH to avoid convergence frustrations. Consider computational resource allocation when selecting algorithms—TRAH's higher per-iteration cost may be justified by guaranteed convergence for production calculations.

The Trust Region Augmented Hessian algorithm represents a significant advancement over traditional DIIS for handling problematic SCF convergence in inorganic complexes. While DIIS remains efficient for routine applications, TRAH provides robust convergence capabilities for challenging systems including open-shell transition metal complexes, metal clusters, and systems with strong electron correlation. The hierarchical approach implemented in ORCA—defaulting to DIIS but automatically activating TRAH when needed—provides an optimal balance of efficiency and reliability.

Future developments in SCF convergence technology will likely focus on adaptive algorithm selection, machine learning-assisted initial guess generation, and improved parallelization of second-order methods. For researchers investigating difficult inorganic complexes, mastering both TRAH and DIIS methodologies, along with understanding their complementary strengths, remains essential for efficient and reliable computational investigations.

Identifying When to Activate TRAH in Your Calculations

The Trust Region Augmented Hessian (TRAH) algorithm is a robust second-order convergence method implemented in quantum chemistry packages like ORCA for achieving Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence in challenging molecular systems. SCF convergence is a fundamental challenge in electronic structure calculations, as total execution time increases linearly with the number of iterations [5] [6]. For routine organic molecules and simple complexes, traditional DIIS (Direct Inversion in the Iterative Subspace) algorithms typically provide efficient convergence. However, for difficult inorganic complexes—particularly open-shell transition metal systems, metal clusters, and radical species—standard algorithms often fail, necessitating advanced methods like TRAH [1].

TRAH provides superior convergence characteristics for several reasons. As a second-order method, it utilizes both gradient and Hessian (second derivative) information to navigate the complex energy surface of challenging electronic structures. This approach is particularly valuable for systems with multiple local minima, small HOMO-LUMO gaps, or significant spin contamination, where first-order methods like DIIS may oscillate or converge to unphysical solutions [1]. The implementation in ORCA automatically activates TRAH when the regular DIIS-based SCF converger struggles to converge, providing a safety net for difficult calculations [1].

When to Activate TRAH: Key Indicators

Automatic Activation Triggers

ORCA's default SCF procedure will automatically activate TRAH when specific convergence problems are detected [1]. The algorithm monitors these key indicators to determine when escalation to a more robust method is necessary:

- Slow Convergence with DIIS: When the DIIS algorithm shows slow progress with minimal energy or density change over multiple iterations.

- Oscillatory Behavior: When the SCF energy oscillates between values without settling toward convergence.

- Persistent Large Gradients: When the orbital gradient remains large despite multiple DIIS iterations.

- Stalled Convergence: When the calculation approaches convergence but fails to achieve the required thresholds within a reasonable number of cycles.

System-Specific Indicators for Manual Activation

For certain classes of systems known to be problematic, researchers should consider manually activating TRAH from the beginning of calculations. The following table summarizes key molecular characteristics that warrant TRAH activation:

Table 1: System Characteristics Warranting TRAH Activation

| System Characteristic | Examples | Convergence Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Open-Shell Transition Metal Complexes | Fe-S clusters, Mn catalases, Cu oxidases | Multiple close-lying electronic states, strong spin contamination [1] |

| Systems with Small HOMO-LUMO Gaps | Metal clusters, conjugated radicals, near-degenerate systems | Instability in density matrix updates, oscillatory behavior [12] |

| Multireference Character | Cr and Mo complexes, lanthanide compounds | Broken symmetry solutions, difficulty identifying correct ground state [6] |

| Large, Flexible Systems with Diffuse Functions | Anionic systems with augmented basis sets | Linear dependence issues, numerical instability in integral evaluation [1] |

TRAH Control Parameters and Configuration

Core TRAH Parameters

TRAH behavior can be fine-tuned through specific parameters in the ORCA SCF block. These parameters control when TRAH activates and how it behaves during the convergence process:

Table 2: Key TRAH Control Parameters in ORCA

| Parameter | Default Value | Description | Recommended Adjustment |

|---|---|---|---|

AutoTRAH |

true |

Enables automatic TRAH activation | Set to false for full manual control |

AutoTRAHTol |

1.125 |

Threshold for automatic TRAH activation | Decrease (e.g., 1.5) for earlier activation |

AutoTRAHIter |

20 |

Iterations before interpolation used | Increase for more stable convergence |

AutoTRAHNInter |

10 |

Number of interpolation iterations | Increase for difficult cases |

Manual TRAH Activation Protocol

For complete manual control over TRAH, use the following protocol:

- Disable automatic TRAH activation:

! NoAutoTRAH - Force TRAH usage from the first iteration:

! TRAH - Configure specific TRAH parameters in the SCF block:

TRAH Workflow and Decision Protocol

The following diagram illustrates the complete decision protocol for TRAH activation, from initial calculation setup to troubleshooting pathological cases:

Complementary SCF Convergence Techniques

When TRAH requires supplementation, several proven techniques can enhance convergence for difficult inorganic complexes:

Initial Guess Strategies

The initial Fock matrix and molecular orbitals significantly impact SCF convergence trajectory. For challenging systems, consider these advanced guess strategies:

- Fragment/Atom Guess (

PAtom): Uses superposition of atomic densities, often more reliable than default for transition metals [12]. - Hückel Guess (

Hueckel): Parameter-free Hückel method based on atomic calculations, effective for systems with conjugation [12]. - Orbital Reading (

MORead): Converge a simpler calculation (e.g., BP86/def2-SVP) and use orbitals as guess for target calculation [1].

Convergence Acceleration Parameters

When TRAH alone is insufficient, these parameters can resolve specific convergence pathologies:

Table 3: Supplemental SCF Convergence Parameters

| Parameter | Application | Typical Values | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

DIISMaxEq |

Oscillating systems | 15-40 (default: 5) | Increases DIIS subspace size [1] |

LevelShift |

Small-gap systems | 0.1-0.5 | Increases HOMO-LUMO gap [12] |

Damp |

Initial oscillations | 0.3-0.7 | Dampens density updates [12] |

DirectResetFreq |

Numerical noise | 1-15 (default: 15) | Rebuilds Fock matrix [1] |

Experimental Protocol for Pathological Cases

For truly pathological systems that resist standard TRAH approaches, implement this comprehensive protocol:

Phase 1: System Preparation and Initialization

- Geometry Validation: Verify molecular geometry合理性 using molecular mechanics or quick HF optimization.

- Basis Set Selection: Start with moderate basis sets (def2-SVP) before progressing to larger basis sets.

- Initial Guess Selection: Apply system-specific initial guess:

Phase 2: Staged Convergence Approach

- Stage 1 - Conservative Settings: Begin with damped DIIS to establish convergence trajectory:

- Stage 2 - TRAH Activation: If Stage 1 fails after 30-40 iterations, activate TRAH:

- Stage 3 - Aggressive Settings: For persistent failures, implement maximum stabilization:

Phase 3: Post-Convergence Validation

- Stability Analysis: Perform SCF stability check to verify true minimum:

- Spin Analysis: Check 〈S²〉 expectation value for unreasonable spin contamination.

- Orbital Inspection: Examine UCO (unrestricted corresponding orbitals) overlaps and visualize frontier orbitals [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Computational Tools for TRAH SCF Convergence

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| TRAH Algorithm | Second-order SCF convergence | Primary method for difficult convergence cases [1] |

| DIISMaxEq | DIIS subspace expansion | Reduces oscillation in systems with multiple solutions [1] |

| LevelShift | Virtual orbital energy shift | Stabilizes small HOMO-LUMO gap systems [12] |

| MORead | Orbital initial guess | Transfer converged orbitals from simpler calculations [1] |

| Stability Analysis | Wavefunction stability check | Verify solution is true minimum, not saddle point [6] |

| SlowConv/VerySlowConv | Damping parameters | Control large initial density fluctuations [1] |

| UCO Analysis | Orbital overlap examination | Diagnose spin contamination in open-shell systems [6] |

Implementing TRAH SCF: Practical Setup and Workflow Strategies

Trust-Region Augmented Hessian (TRAH) is a robust, second-order convergence algorithm implemented in the ORCA electronic structure package to solve self-consistent field (SCF) equations for molecular systems with challenging electronic structures. Conventional DIIS (Direct Inversion in the Iterative Subspace) algorithms often struggle with open-shell transition metal complexes, metal clusters, and other inorganic systems characterized by near-degenerate orbital energies and strong correlation effects. The TRAH-SCF method exploits the full electronic augmented Hessian in combination with a trust-region approach to ensure smooth, reliable convergence towards a local energy minimum, making it particularly suited for difficult cases in inorganic chemistry and drug development research involving metalloenzymes or catalytic centers [13].

Essential TRAH Input Parameters and Syntax

Configuring TRAH-SCF in ORCA primarily involves the %scf input block. The following parameters control the activation, timing, and behavior of the TRAH algorithm.

Core TRAH Activation and Control Parameters

Table 1: Essential TRAH Configuration Parameters in the ORCA %scf Block

| Parameter | Default Value | Recommended Setting | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

AutoTRAH |

true (ORCA 5.0+) |

true |

Enables automatic activation of TRAH upon detection of SCF convergence difficulties [1]. |

AutoTRAHTOl |

1.125 |

1.0 - 1.125 |

Orbital gradient threshold for automatic TRAH activation. Lower values delay activation [1]. |

AutoTRAHIter |

20 |

15 - 25 |

Number of iterations before interpolation is used within TRAH [1]. |

AutoTRAHNInter |

10 |

10 - 20 |

Number of iterations used in the interpolation procedure [1]. |

TRAHMaxIter |

Not Specified | 50 - 100 |

Maximum number of iterations allowed for the TRAH solver. |

TRAHGrid |

3 |

4 - 5 |

Integration grid size for Fock builds in TRAH; higher for increased accuracy. |

Basic and Advanced Input Syntax

The simplest way to use TRAH is to rely on ORCA's automatic algorithm switching, which is the default behavior since ORCA 5.0. A minimal input file for a single-point energy calculation is shown below:

For more control, especially in pathological cases, parameters can be explicitly defined:

To disable TRAH and revert to traditional DIIS/SOSCF algorithms, the ! NoTrah simple keyword can be used [1].

TRAH-SCF Configuration and Convergence Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and decision process for configuring and executing a TRAH-SCF calculation in ORCA, from input preparation to analysis of results.

Experimental Protocol for TRAH-SCF on Difficult Inorganic Complexes

System Preparation and Initialization

- Molecular Geometry: Obtain initial coordinates from crystallographic data (e.g., .cif file) or a pre-optimized structure. For open-shell systems, ensure reasonable initial spin states and antiferromagnetic coupling patterns where applicable.

- Coordinate Input: Use the standard

* xyz <charge> <multiplicity>*format in ORCA. For high-spin transition metal complexes, carefully select the correct spin multiplicity (2S+1). - Method Selection: Choose an appropriate density functional (e.g., B3LYP, PBE0, TPSSh) and basis set. For transition metals, employ at least a triple-zeta quality basis set (e.g.,

def2-TZVP) with appropriate relativistic effective core potentials (ECPs) for heavy elements [1].

TRAH-SCF Calculation Setup

- Input File Creation: Create a plain text input file (e.g.,

complex_TRAH.inp). - Keyword Specification: Begin with simple keywords defining the method, basis set, and SCF convergence level.

! TightSCFis often recommended for transition metal complexes [5]. - SCF Block Configuration: Implement the

%scfblock with the parameters from Table 1. The following protocol uses robust settings for a challenging Fe-S cluster:

- Job Execution: Run the calculation using the ORCA executable:

orca complex_TRAH.inp > complex_TRAH.out.

Post-Calculation Analysis

- Convergence Verification: Inspect the output file for the

* SCF CONVERGED *message and confirm theFINAL SINGLE POINT ENERGYline does not contain the(SCF not fully converged!)warning [1]. - Stability Analysis: Perform an SCF stability check to ensure the solution found is a true local minimum and not a saddle point, especially for open-shell singlets and broken-symmetry solutions [5].

- Orbital Examination: Visually inspect the converged molecular orbitals (using tools like IboView or ORCA's built-in orbplot utility) to confirm the electronic structure is physically meaningful.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Materials and Resources for TRAH-SCF Studies

| Item | Specification/Example | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure Code | ORCA (version 5.0 or later) | Primary software platform featuring the robust TRAH-SCF implementation [1] [13]. |

| Density Functional | B3LYP, PBE0, TPSSh, BP86 | Exchange-correlation functionals for DFT calculations on transition metal complexes; choice depends on required accuracy for properties like spin-state energetics. |

| Basis Set | def2-TZVP, def2-QZVP, ma-def2-TZVP | Gaussian-type orbital basis sets for expanding molecular orbitals; triple-zeta quality is standard, with augmented versions for anion/anionic species [1]. |

| Auxiliary Basis Set | def2/J, def2-TZVP/C | Density fitting (RI-J) auxiliary basis for Coulomb integral approximation, significantly speeding up SCF iterations [14]. |

| Initial Guess Orbitals | PModel (default), PAtom, HCore | Algorithms to generate initial molecular orbitals; switching from the default PModel to PAtom or HCore can improve initial guess for metals [1]. |

| Molecular Visualization | Avogadro, ChemCraft, IboView | Software for building molecular structures and visualizing converged orbitals and electron densities. |

Troubleshooting and Optimization Guidelines

- Slow TRAH Convergence: If TRAH is activated but converges slowly, consider tightening

AutoTRAHTOlto trigger it earlier or increasingMaxIter. Also, verify the integration grid size (Gridin ORCA) is sufficient [1]. - Handling Numerical Noise: For systems with large basis sets or diffuse functions, set

directresetfreq 1to rebuild the Fock matrix every iteration, eliminating accumulation of numerical errors, albeit at a higher computational cost [1]. - Alternative Algorithms: If TRAH fails or is prohibitively expensive, consider using the

! KDIIS SOSCFcombination, potentially with a delayed SOSCF start (SOSCFStart 0.00033in the%scfblock) [1]. - Orbital Guess Strategies: For persistent failures, converge a simpler method (e.g., BP86/def2-SVP) or a closed-shell ion and use its orbitals as a guess via

! MOReadand the%moinp "gbw_file"directive [1].

Leveraging AutoTRAH for Adaptive Convergence Control

Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence represents a fundamental challenge in electronic structure theory, particularly for difficult inorganic complexes such as open-shell transition metal systems and metal clusters. The total execution time of a quantum chemical calculation increases linearly with the number of SCF iterations, making convergence efficiency critical to computational performance. Traditional SCF convergence accelerators, such as DIIS (Direct Inversion in the Iterative Subspace), often struggle with these challenging systems, exhibiting oscillatory behavior or complete failure to converge. The Trust Region Augmented Hessian (TRAH) approach, implemented as a robust second-order converger in ORCA, provides a more reliable but computationally more expensive alternative to conventional methods.

AutoTRAH represents an evolutionary advancement in SCF convergence technology by introducing adaptive control mechanisms that automatically determine when TRAH should be activated. Since ORCA 5.0, this hybrid approach has become the default strategy, combining the efficiency of traditional DIIS-based methods with the robustness of TRAH for problematic cases. The algorithm intelligently monitors convergence behavior during the initial SCF iterations and activates TRAH only when necessary, thus optimizing the trade-off between computational cost and reliability. For researchers investigating difficult inorganic complexes, particularly in pharmaceutical development where metal-containing enzymes and catalysts are prevalent, understanding and properly configuring AutoTRAH is essential for obtaining physically meaningful results in a reasonable timeframe.

AutoTRAH Parameters and Configuration

Core AutoTRAH Control Parameters

The adaptive behavior of AutoTRAH is governed by a set of key parameters that determine when and how the second-order convergence algorithm engages. These parameters can be fine-tuned through the ORCA input block structure to optimize performance for specific classes of inorganic complexes. The primary control parameters are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Core AutoTRAH Control Parameters and Their Functions

| Parameter | Default Value | Function | Recommended Range |

|---|---|---|---|

AutoTRAH |

true |

Enables or disables the AutoTRAH adaptive algorithm | Boolean (true/false) |

AutoTRAHTOl |

1.125 |

Threshold for orbital gradient to activate TRAH | 1.0 - 1.5 (lower = more sensitive) |

AutoTRAHIter |

20 |

Number of iterations before interpolation is used | 10 - 30 |

AutoTRAHNInter |

10 |

Number of iterations used in interpolation | 5 - 20 |

The AutoTRAHTOl parameter represents the most critical adjustment point for system-specific tuning. This threshold determines the orbital gradient level at which TRAH activation occurs, effectively setting the sensitivity of the adaptive algorithm. For particularly problematic systems such as iron-sulfur clusters or high-spin cobalt complexes, lowering this value to 1.0 can ensure earlier TRAH intervention, potentially preventing convergence failures. Conversely, for systems that exhibit slow but stable convergence, increasing this threshold to approximately 1.5 can maintain DIIS efficiency while preserving TRAH as a safety net.

Integration with SCF Convergence Tolerances

AutoTRAH functions within the broader context of SCF convergence tolerances, which define the target precision for the wavefunction. ORCA provides a hierarchical system of convergence criteria through simple keywords or detailed %scf block parameters, as detailed in Table 2. When AutoTRAH is active, these tolerances determine the convergence completion criteria, while the AutoTRAH parameters control the pathway to achieve them.

Table 2: SCF Convergence Tolerances for Electronic Structure Calculations

| Convergence Level | TolE (Energy) | TolRMSP (Density) | TolMaxP (Max Density) | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

LooseSCF |

1e-5 |

1e-4 |

1e-3 |

Preliminary geometry optimizations |

NormalSCF |

1e-6 |

1e-6 |

1e-5 |

Standard single-point calculations |

TightSCF |

1e-8 |

5e-9 |

1e-7 |

Transition metal complexes, frequency calculations |

VeryTightSCF |

1e-9 |

1e-9 |

1e-8 |

High-precision spectroscopy, property calculations |

For inorganic complexes exhibiting significant multireference character or strong correlation effects, the TightSCF criteria are generally recommended as they provide sufficient precision without excessive computational overhead. The combination of TightSCF tolerances with properly configured AutoTRAH parameters represents the optimal balance for most challenging transition metal systems in pharmaceutical research contexts, including metalloenzyme active sites and organometallic catalysts.

Configuration Protocols for AutoTRAH

Basic AutoTRAH Implementation

The simplest implementation of AutoTRAH leverages the default settings, which have been optimized for broad applicability across diverse chemical systems. For initial investigations of new inorganic complexes, the following input structure represents the recommended starting point:

This configuration activates the adaptive TRAH algorithm with default thresholds while setting convergence tolerances to appropriate values for transition metal complexes. The TightSCF keyword implicitly sets the integral accuracy thresholds to levels compatible with the desired density and energy convergence, which is critical because SCF convergence cannot be achieved if the integral error exceeds the convergence criteria.

Advanced AutoTRAH Tuning for Pathological Cases

For particularly challenging systems such as metal clusters, antiferromagnetically coupled dimers, or complexes with significant spin contamination, more aggressive AutoTRAH tuning may be necessary. The following protocol has proven effective for iron-sulfur clusters and other computationally problematic systems:

The SlowConv keyword introduces additional damping parameters that stabilize the initial SCF iterations, which is particularly valuable for systems exhibiting large fluctuations in the early stages of convergence. Increasing DIISMaxEq expands the number of Fock matrices retained for DIIS extrapolation, providing better convergence acceleration before TRAH activation. The MaxIter parameter is increased to accommodate the potentially slower convergence trajectory of pathological systems.

Disabling AutoTRAH for Performance-Critical Applications

In certain high-throughput screening applications or during preliminary stages of drug development, computational efficiency may take precedence over convergence robustness. In such cases, AutoTRAH can be disabled in favor of traditional convergence accelerators:

The KDIIS+SOSCF combination provides an effective alternative convergence pathway that may be sufficient for less problematic systems. The SOSCFStart parameter delays the onset of the Second-Order SCF algorithm until a tighter orbital gradient is achieved, which improves stability for open-shell transition metal complexes.

Experimental Workflows and Diagnostic Procedures

AutoTRAH-Enabled SCF Convergence Workflow

The integration of AutoTRAH into standard computational protocols follows a logical progression that balances efficiency with reliability. The workflow, depicted in Figure 1, begins with standard DIIS acceleration and only engages the more computationally intensive TRAH algorithm when convergence problems are detected.

Figure 1: AutoTRAH Adaptive Convergence Workflow

The adaptive nature of this workflow ensures that computational resources are allocated efficiently, with TRAH engagement occurring only after traditional methods demonstrate insufficient progress. The monitoring phase tracks key convergence metrics, including the orbital gradient, energy change between cycles, and density matrix changes, comparing them against the AutoTRAHTOl threshold to determine if TRAH activation is warranted.

Diagnostic Protocol for SCF Convergence Problems

When faced with SCF convergence failures, a systematic diagnostic approach is essential for identifying the root cause and implementing an appropriate solution. The protocol outlined in Figure 2 provides a logical framework for troubleshooting problematic inorganic complexes.

Figure 2: SCF Convergence Diagnostic Protocol

The diagnostic protocol begins with fundamental checks of molecular geometry, as unreasonable bond lengths or angles can prevent convergence even with optimal algorithmic settings. The initial orbital guess is then evaluated, with alternative guess operators (PAtom, Hueckel, or HCore) potentially providing a more stable starting point. For severely problematic cases, converging a simpler computational method (such as BP86/def2-SVP) and reading the orbitals as a guess for the target method can break convergence deadlocks.

Case Studies and Applications

Iron-Sulfur Cluster Convergence

Iron-sulfur clusters represent one of the most challenging classes of systems for SCF convergence due to their high spin states, metal-metal interactions, and delocalized electronic structures. For a typical [4Fe-4S] cluster, the following AutoTRAH configuration has demonstrated robust convergence:

The increased DIISMaxEq value (25 versus the default of 5) provides a larger historical basis for DIIS extrapolation, which is particularly valuable for systems with complex potential energy surfaces. The directresetfreq parameter controls how frequently the full Fock matrix is recalculated versus using incremental updates, with intermediate values (5-10) reducing numerical noise that can impede convergence.

Open-Shell Transition Metal Complexes

For mononuclear open-shell transition metal complexes commonly encountered in pharmaceutical research, such as manganese or cobalt coordination compounds, a less aggressive AutoTRAH approach is typically sufficient:

The combination of AutoTRAH with SOSCF provides multiple layers of convergence acceleration, with SOSCF activating at a tighter orbital gradient threshold (0.00033 versus the default 0.0033) to ensure stability for open-shell systems. This configuration has proven particularly effective for metalloporphyrins and other biologically relevant metal complexes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful application of AutoTRAH methodology requires understanding both the computational algorithms and the practical tools available for implementation and diagnostics. Table 3 summarizes the key components of the computational chemist's toolkit for addressing SCF convergence challenges in inorganic complexes.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for SCF Convergence Challenges

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| AutoTRAH Algorithm | Convergence Accelerator | Adaptive second-order convergence | Primary solution for oscillating or stagnant convergence |

| MORead | Orbital Manipulation | Reads orbitals from previous calculation | Providing improved initial guess from converged simpler method |

| Stability Analysis | Diagnostic Tool | Checks if solution is a true minimum | Post-convergence verification, especially for open-shell singlets |

| SlowConv/VerySlowConv | Damping Protocol | Increases damping to control oscillations | Systems with large initial density fluctuations |

| KDIIS+SOSCF | Alternative Algorithm | Efficient convergence pathway | Performance-sensitive applications with less problematic systems |

| TightSCF | Precision Standard | Defines convergence tolerances | Transition metal complexes requiring high precision |

Each tool in this repertoire addresses specific aspects of the SCF convergence problem, with AutoTRAH serving as the centerpiece for adaptive control in challenging cases. The MORead functionality is particularly valuable in protocol-driven research, as it enables a stepwise approach where a computationally inexpensive method (BP86/def2-SVP) is converged first, with its orbitals subsequently used to initiate more advanced (and expensive) calculations.

The AutoTRAH algorithm represents a significant advancement in addressing the persistent challenge of SCF convergence for difficult inorganic complexes. By providing adaptive control over the engagement of second-order convergence methods, it effectively balances computational efficiency with robustness, making it particularly valuable for pharmaceutical researchers investigating metalloenzymes, metal-based catalysts, and other transition metal systems. The protocols and configurations presented herein provide a comprehensive framework for implementing AutoTRAH in both standard and pathological cases, while the diagnostic procedures facilitate systematic troubleshooting when convergence issues arise. As computational chemistry continues to expand its role in drug development, mastering these advanced SCF convergence techniques becomes increasingly essential for producing reliable, physically meaningful results in a resource-efficient manner.

Optimizing Convergence Tolerances for Transition Metal Systems

Within the broader research on Trust Radius Augmented Hessian (TRAH) SCF settings for difficult inorganic complexes, optimizing convergence tolerances is a critical step for achieving reliable results. Transition metal systems, particularly open-shell compounds, are notoriously challenging for self-consistent field (SCF) convergence due to localized d- and f-electrons, small HOMO-LUMO gaps, and complex potential energy surfaces [1] [15]. This application note provides detailed protocols for systematically adjusting convergence parameters and algorithms to efficiently handle these problematic cases, with a focus on practical implementation within modern computational frameworks.

Background and Significance

The Challenge of Transition Metal Systems

Transition metal complexes present unique challenges for quantum chemical calculations. Metallic bonding character and the presence of near-degenerate electronic states lead to complex potential energy surfaces that are difficult to describe with standard algorithms [16]. The many-body interactions in d-block elements, particularly early transition metals, result in sharper densities of states near the Fermi level, creating harder-to-learn surfaces that challenge both SCF procedures and machine-learned force field development [16].

Electronic structure analysis reveals that metal-metal bonding in complexes often involves unique orbital interactions, such as the 6dx2-y2-ndx2-y2 interactions observed in uranium-group metal complexes, which require precise convergence to properly characterize [17]. The inherent multi-reference character and small energy gaps between electronic states in these systems necessitate robust convergence protocols.

Quantitative Convergence Criteria

Standard Convergence Tolerance Presets

Table 1: Standard Geometry Optimization Convergence Criteria (Atomic Units)

| Preset | GMAX (Max Gradient) | GRMS (RMS Gradient) | XMAX (Max Step) | XRMS (RMS Step) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOOSE | 0.00450 | 0.00300 | 0.01800 | 0.01200 |

| DEFAULT | 0.00045 | 0.00030 | 0.00180 | 0.00120 |

| TIGHT | 0.000015 | 0.00001 | 0.00006 | 0.00004 |

These criteria, implemented in packages like NWChem, provide standardized settings for geometry convergence [18]. The coordinate system used (Z-matrix, redundant internals, or Cartesian) can affect convergence rates, though Cartesian step criteria (XMAX, XRMS) ensure consistent final geometries across different coordinate systems.

SCF Convergence Parameters

Table 2: Key SCF Convergence Parameters for Transition Metal Systems

| Parameter | Standard Value | Transition Metal Recommendation | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| MaxIter | 125 | 500-1500 | Maximum SCF cycles |

| DIISMaxEq | 5 | 15-40 | Fock matrices in DIIS extrapolation |

| directresetfreq | 15 | 1-15 | Fock matrix rebuild frequency |

| AutoTRAHTOl | 1.125 | 1.125 | TRAH activation threshold |

| SOSCFStart | 0.0033 | 0.00033 | Orbital gradient for SOSCF startup |

For truly pathological systems like metal clusters, extremely high MaxIter values (1500) combined with expanded DIISMaxEq (15-40) and frequent Fock matrix rebuilds (directresetfreq = 1) may be necessary, though these significantly increase computational cost [1].

Experimental Protocols

Systematic Workflow for SCF Convergence

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for addressing SCF convergence issues in transition metal systems: