Mastering Precursor Volatility: A Comprehensive Guide for Advanced Inorganic Synthesis in Materials Science and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive examination of precursor volatility management in inorganic synthesis, addressing critical challenges faced by researchers and development professionals.

Mastering Precursor Volatility: A Comprehensive Guide for Advanced Inorganic Synthesis in Materials Science and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of precursor volatility management in inorganic synthesis, addressing critical challenges faced by researchers and development professionals. Covering foundational principles derived from chemical vapor deposition and atomic layer deposition technologies, the guide explores theoretical frameworks governing vapor pressure and thermal stability. It details practical methodological approaches for handling volatile and reactive precursors, including specialized equipment and safety protocols. The content further addresses systematic troubleshooting for common failure modes like sluggish kinetics and precursor decomposition, while highlighting validation techniques and comparative analyses of precursor classes. By integrating traditional methods with emerging computational and autonomous technologies, this resource aims to accelerate the synthesis of novel functional materials for biomedical and industrial applications.

Understanding Precursor Volatility: Fundamental Principles and Chemical Concepts

In the precise world of inorganic synthesis, particularly for applications in semiconductor devices, catalysis, and advanced materials, volatility refers to the ability of a solid or liquid precursor to transition into the vapor phase at practical temperatures and pressures without significant decomposition. This property is fundamental to gas-phase deposition techniques like Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) and Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD), where precursors must be transported via the vapor phase to a substrate surface to form thin films, coatings, or nanoparticles. The controlled application of volatile compounds enables the creation of materials with exacting specifications for modern technologies, from microprocessors to medical devices.

Effective volatility is a delicate balance. A precursor must possess sufficient vapor pressure for efficient transport yet maintain adequate thermal stability to prevent premature decomposition during vaporization. It must then cleanly decompose or react at the substrate surface to yield the desired material, ideally without incorporating impurities. This guide addresses the common challenges researchers face in managing precursor volatility and provides practical solutions for optimizing synthesis outcomes, framed within the broader context of handling precursor volatility in inorganic synthesis research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Volatility

Q1: What defines an "ideal" volatile precursor for CVD or ALD processes? An ideal precursor for CVD and ALD processes possesses a balanced combination of several key properties [1] [2]:

- Sufficient Volatility: The precursor should vaporize at a practical and controllable temperature, typically at pressures below 1 Torr.

- Thermal Stability: It must not decompose during the vaporization and transport process, maintaining a "temperature window" between its vaporization and decomposition points.

- High Reactivity: The precursor should cleanly and efficiently react on the substrate surface to form the desired material.

- Synthetic Accessibility & Storage Stability: It should be readily synthesized in high purity and remain stable during storage.

- Low Toxicity: Safe handling is a critical practical consideration.

- Clean Conversion: The decomposition should yield only the target material and volatile by-products, avoiding the incorporation of impurities.

Q2: Why is silver particularly challenging to work with in CVD/ALD, and what precursor strategies exist? Silver chemistry presents specific challenges due to the low charge density of the silver cation and its ease of reduction to metallic form, even under the influence of light [2]. This inherent instability makes designing robust silver precursors difficult. Research has therefore focused on developing specific classes of volatile silver complexes. The most promising strategies involve [1] [2]:

- β-Diketonates: Compounds like (hfac)Ag(1,5-COD) are commonly used.

- N-Heterocyclic Carbene Complexes: These can offer improved stability.

- Phosphine Complexes: Such as Ag(fod)(PEt3), which has been used in plasma-enhanced ALD.

- Perfluorocarboxylates: Another class explored for their volatility.

Q3: What are the common signs of precursor decomposition during vaporization? Precursor degradation during the vaporization step is a common failure point. Key indicators include [3]:

- Visible Changes: The appearance of discoloration (darkening) or the formation of a non-volatile residue in the precursor vessel or in supply lines.

- Process Instability: Unstable vapor pressure readings or fluctuating mass flow rates during delivery.

- Product Contamination: The final deposited film or coating shows poor purity, high carbon content, or unsatisfactory electrical/optical properties.

Q4: How can I troubleshoot low or inconsistent deposition rates? Low or erratic deposition rates often stem from issues with precursor delivery. A systematic troubleshooting approach is recommended [2]:

- Verify Vaporization: Confirm that the precursor boat or bubbler is maintained at the correct, stable temperature to ensure consistent vapor pressure.

- Check for Decomposition: Inspect the precursor source and delivery lines for signs of residue, which would indicate thermal breakdown and a blocked flow path.

- Confirm Carrier Gas Flow: Ensure the carrier gas flow rate is stable and appropriate for the precursor's volatility.

- Assess Reactor Conditions: Verify that the substrate temperature and reactor pressure are within the optimal "process window" for the specific precursor chemistry.

Q5: What methods can be used for precursors with inherently low volatility? For precursors that lack sufficient volatility for conventional CVD, several alternative introduction methods have been developed [2]:

- Direct Liquid Injection (DLI): The precursor is dissolved in a suitable solvent and injected as a liquid into a vaporizer, which rapidly turns the mixture into a vapor.

- Aerosol-Assisted CVD (AA-CVD): A precursor solution is atomized into a fine aerosol, which is then transported to the hot substrate.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Volatility-Related Issues

Table: Troubleshooting Common Volatility-Related Problems in Inorganic Synthesis.

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Vapor Pressure | Precursor temperature too low; Inherently low-volatility material; Precursor degradation over time. | Optimize vaporization temperature; Switch to a more volatile analogue (e.g., fluorinated ligands); Use DLI or AA-CVD methods [2]. |

| Precursor Decomposition | Vaporization temperature is too high; The precursor is thermally unstable; Localized overheating in the source. | Lower the vaporization temperature; Use a temperature gradient; Explore a different precursor class with higher thermal stability [1]. |

| Inconsistent Deposition | Fluctuating source temperature; Unstable carrier gas flow; Condensation in delivery lines. | Ensure precise temperature control for the precursor; Use mass flow controllers for gas; Heat all delivery lines to prevent cold spots. |

| Poor Film Purity | Premature gas-phase reactions; Incomplete precursor ligand removal; Incorporation of impurity atoms. | Adjust substrate temperature and reactor pressure; Use a more reactive co-reagent (in ALD); Ensure higher precursor purity and optimize reaction conditions [2]. |

Experimental Protocols for Handling Volatile Precursors

Protocol 1: Synthesis Verification and Reproducibility

To ensure a synthesis procedure is robust and can be reliably reproduced by other researchers, as per the standards of publications like Inorganic Syntheses, follow this methodology [3]:

- Independent Checking: The detailed synthesis procedure must be submitted to an independent laboratory for verification. The checkers will attempt to reproduce the synthesis exactly as written.

- Assessment Criteria: The checking report must confirm:

- The synthesis proceeds smoothly, yielding a product with purity and yield close to what was reported.

- The procedure is described with sufficient detail to be followed by someone new to the area without encountering difficulties.

- All hazardous steps are clearly identified with adequate safety procedures specified.

- Documentation: The final published procedure will include an estimate of the time required, a warning of all potential hazards, and clear criteria for judging the purity of the final product.

Protocol 2: In-Situ Tracking of Volatile Products

Understanding the evolution of volatile by-products is key to elucidating pyrolysis and solid-state reaction mechanisms. This protocol outlines an approach for in-situ tracking, adapted from advanced pyrolysis studies [4]:

- Sample Preparation: For complex materials like sewage sludge, separate and extract major organic components (e.g., proteins, polysaccharides, humic acids) to study their individual pyrolysis behaviors.

- Coupled Thermal Analysis: Use Thermogravimetry (TG) to monitor mass loss (char formation) as a function of temperature. Couple the TG directly to a Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectrometer to identify and quantify gaseous products evolved at different temperature stages.

- Signal Deconvolution and Analysis: Apply a Gaussian model to deconvolute overlapping mass loss events and determine the kinetic parameters (activation energy, pre-exponential factor) for each stage of the solid-state reaction. Use Two-Dimensional Correlation Spectroscopy (2D-COS) on the FTIR data to determine the sequence of volatile species release.

- Validation with Mass Spectrometry: Use in-situ photoionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (SPI-TOF-MS) to validate the IR results and accurately identify molecules with similar IR signals. This provides a quantitative profile of volatile intermediates.

Workflow: Tracking Solid-State Reactions and Volatile Fate

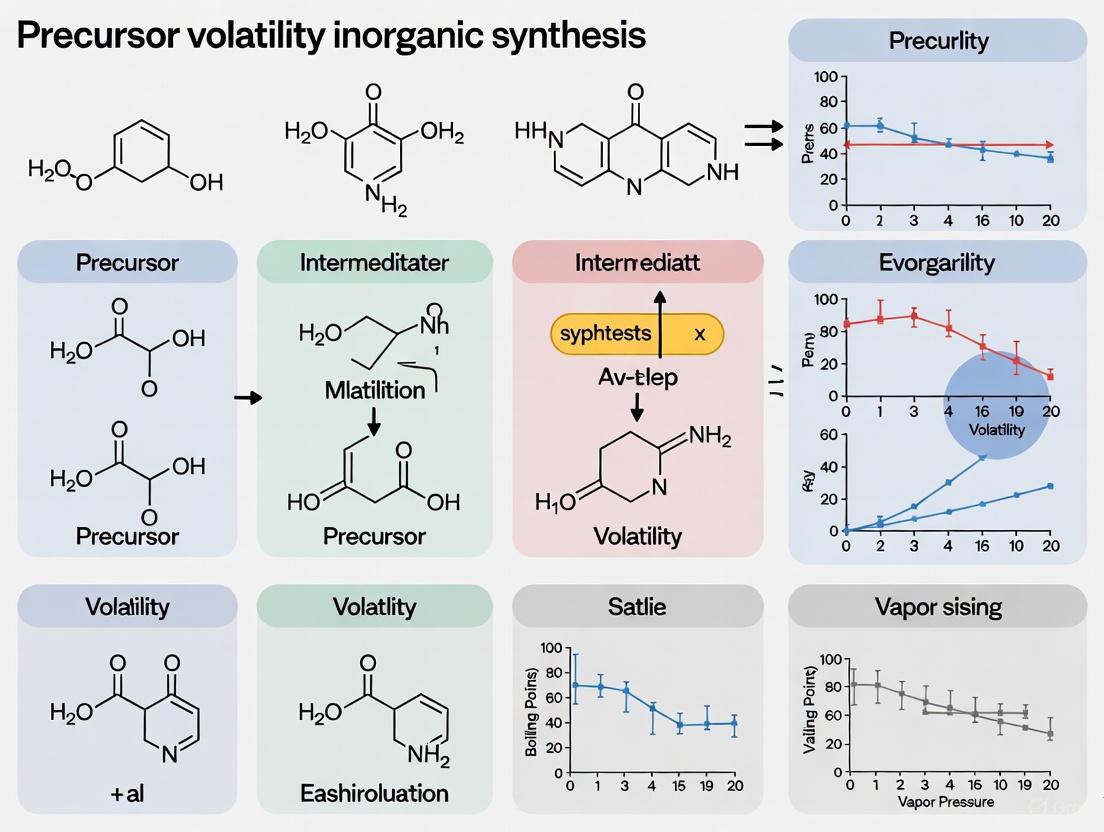

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental workflow for correlating solid-state reactions with the evolution of volatile products.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Volatile Precursor Synthesis and CVD/ALD.

| Item | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Silver β-Diketonates(e.g., (hfac)Ag(1,5-COD)) | Volatile precursor for depositing silver thin films and nanoparticles via CVD/ALD [1] [2]. | Moderate volatility, relatively stable, but can be sensitive to light and prone to reduction. |

| N-Heterocyclic Carbene (NHC) Complexes | A modern class of precursors for silver and other metals, designed for improved stability [2]. | High thermal stability, tunable volatility through ligand modification. |

| Phosphine Complexes(e.g., Ag(fod)(PEt3)) | Used in plasma-enhanced ALD (PE-ALD) processes for silver [1]. | Volatile and reactive in the presence of plasma, allowing lower deposition temperatures. |

| Inert Atmosphere Equipment(Gloveboxes, Schlenk lines) | For handling air- and moisture-sensitive precursors to prevent decomposition before use. | Maintains high purity (e.g., Nâ‚‚ or Ar gas environment), essential for reproducible results. |

| Temperature-Controlled Precursor Vessels | To vaporize solid or liquid precursors at a precise, constant temperature in CVD/ALD systems. | Prevents thermal decomposition and ensures consistent vapor pressure for uniform deposition. |

| Xeruborbactam Isoboxil | Xeruborbactam Isoboxil, CAS:2708983-65-5, MF:C15H16BFO6, MW:322.09 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Seco-DUBA hydrochloride | Seco-DUBA hydrochloride, MF:C29H24Cl2N4O4, MW:563.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

In inorganic synthesis and vapor-phase deposition processes, the precise handling of precursors hinges on a fundamental understanding of two distinct types of stability: thermodynamic and kinetic.

Thermodynamic stability describes the inherent, equilibrium state of a substance—its lowest free energy state under a given set of conditions. For vapor-phase precursors, this is quantified by vapor pressure, which is the pressure exerted by a vapor in thermodynamic equilibrium with its condensed phases (liquid or solid) at a given temperature [5]. A substance with high vapor pressure is termed volatile, indicating a thermodynamic drive to exist in the vapor phase.

Kinetic stability, in contrast, is concerned with the rate at which a system moves toward its thermodynamic equilibrium. It is governed by the activation energy of the processes involved, such as evaporation or decomposition [6]. A kinetically stable precursor might be thermodynamically volatile but will not evaporate or decompose rapidly if the energy barrier for these processes is high. In practice, this means a precursor can be handled without significant loss or degradation over a practical timescale, even if it is not in its most stable state.

Mastering the interplay between these principles is essential for overcoming central challenges in precursor design and handling, including preventing premature decomposition, ensuring consistent vapor delivery, and extending the functional lifetime of reactive compounds.

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Fundamental Concepts

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between thermodynamic and kinetic stability in the context of precursor design?

| Aspect | Thermodynamic Stability | Kinetic Stability |

|---|---|---|

| Governs | Final, equilibrium state of a system [7] | Speed (rate) at which a reaction occurs [7] |

| Key Parameter | Free energy change (ΔG) [7] | Activation energy (Ea) [6] |

| Primary Concern for Precursors | Volatility and vapor pressure at equilibrium [5] | Resistance to decomposition during vaporization and delivery [8] |

| Analogy | Depth of a valley on a potential energy surface [6] | Height of the hill separating one valley from another [6] |

| Product Favored | The most stable (lowest energy) product [7] | The fastest-formed product [7] |

Q2: Why does my precursor sometimes decompose before vaporizing, and how can I prevent this?

This is a classic problem of kinetic instability. The precursor has sufficient thermal energy to overcome the activation energy barrier for decomposition before it can overcome the (higher) barrier for controlled evaporation.

- Problem: The vaporization temperature is too close to or exceeds the precursor's decomposition temperature.

- Solution:

- Lower the Vaporization Temperature: Reduce the system pressure to lower the boiling point of the precursor [9].

- Use a Liquid Precursor System: Liquid precursors, such as those developed for molybdenum (e.g.,

MoCl3(thd)(THF)andMoCl2(thd)2), can offer more consistent vapor pressure and reduce the risk of thermal stress compared to solid precursors that require sublimation [10]. - Employ a Controlled Evaporation & Mixing (CEM) System: This technology injects a precisely metered liquid droplet stream into a carrier gas, enabling rapid evaporation at a lower bulk temperature than traditional bubblers, thereby minimizing thermal exposure [9].

Vapor Pressure & Delivery Control

Q3: My vapor delivery rate is unstable, even with precise temperature control. What could be wrong?

Traditional bubbler systems are highly sensitive to fluctuations in process conditions. As shown in the table below, several factors beyond temperature can disrupt stable delivery [8] [9].

- Problem: Instability in carrier gas flow rate, system pressure, or liquid level in a bubbler.

- Solution: Implement a closed-loop control system.

| Factor | Effect on Vapor Delivery | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Carrier Gas Flow Rate | Fluctuations cause variable saturation levels in a bubbler [9]. | Use a mass flow controller (MFC) for the carrier gas [9]. |

| Total System Pressure | Changes directly affect vapor pressure and saturation equilibrium [8]. | Implement pressure-based vapor concentration control (VCC) [8]. |

| Liquid Level in Bubbler | Decreasing level alters the surface area and can affect saturation efficiency. | Switch to a direct injection system (CEM) that is independent of liquid level [9]. |

| Bubbler Temperature | A change of just 1°C can cause a ~7% change in precursor concentration [8]. | Use a VCC module with integrated concentration monitoring and control [8]. |

Q4: How can I accurately predict the volatility of a novel precursor before I synthesize it?

Traditional first-principles calculation of volatility is computationally challenging due to the fine balance of interatomic forces involved [11].

- Problem: Lack of experimental vapor pressure data for novel or proposed precursor molecules.

- Solution: Leverage machine learning (ML) models. Schrödinger, for example, has developed ML models trained on organometallic complexes that can predict evaporation/sublimation temperature at a given vapor pressure with an average accuracy of ±9°C [11]. This allows for high-throughput computational screening of candidate molecules.

Condensation & Handling

Q5: I keep experiencing condensation in my vapor delivery lines. How do I prevent this?

Condensation occurs when the vapor temperature falls below its dew point at the local system pressure.

- Problem: Temperature gradients in the delivery line or incorrect pressure management.

- Solution: The fundamental rule is to keep the temperature in all downstream components (lines, valves, chambers) higher than the temperature inside the evaporation unit (e.g., CEM or bubbler) and above the dew point [9]. Alternatively, without changing temperature, ensure the pressure downstream is always lower than the pressure inside the evaporation unit [9].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Assessing Precursor Kinetic Stability via Isothermal Thermo-Gravimetric Analysis (TGA)

Objective: To determine the temperature-dependent decomposition rate of a volatile precursor, distinguishing its evaporation from its decomposition.

Materials:

- Thermogravimetric Analyzer (TGA)

- High-purity nitrogen carrier gas

- Sample pans

- Precursor sample

Procedure:

- Calibration: Calibrate the TGA balance and temperature according to the manufacturer's specifications.

- Loading: Load a small, precisely weighed sample (1-5 mg) of the precursor into an open sample pan.

- Atmosphere Control: Purge the TGA furnace with a constant flow of inert nitrogen gas (e.g., 50 mL/min) to remove air and transport evolved vapors.

- Ramp Experiment: Perform an initial temperature ramp (e.g., 10°C/min) from room temperature to 400°C to identify the onset temperatures for both evaporation and decomposition.

- Isothermal Holds: Based on the ramp data, select at least three temperatures where decomposition is suspected. For each temperature, load a fresh sample and equilibrate the TGA at the target temperature. Monitor the mass loss over time for 60-120 minutes.

- Data Analysis: For each isothermal hold, plot the remaining mass fraction versus time. Fit the data to a kinetic model (e.g., a first-order rate law for decomposition). The rate constant (k) at each temperature can be extracted.

Interpretation: A sample that is kinetically stable will show a rapid mass loss due to evaporation, followed by a plateau with minimal further mass loss. A kinetically unstable sample will show a continuous, slower mass loss after the initial evaporation, indicative of ongoing decomposition. The extracted rate constants can be used in the Arrhenius equation to predict decomposition rates at storage or operating temperatures [12].

Protocol: Implementing Flow-Based Vapor Concentration Control (VCC)

Objective: To achieve stable and precise molar delivery of a precursor vapor by controlling the dilution ratio of a saturated vapor stream.

Materials:

- Saturated vapor source (e.g., temperature-controlled bubbler or saturator)

- Two high-accuracy Mass Flow Controllers (MFCs)

- Heated gas lines and mixing chamber

- Pressure sensors

- System control software

Procedure:

- Saturation: Generate a stream of carrier gas fully saturated with precursor vapor by bubbling a controlled gas flow (MFC1) through a temperature-stabilized precursor reservoir [8] [9].

- Dilution: A second MFC (MFC2) is used to supply a pure, heated dilution gas stream.

- Mixing: The saturated vapor stream and the dilution gas stream are combined in a heated mixing chamber to ensure homogeneity [9].

- Concentration Calculation: The molar concentration of the precursor in the final gas mixture is calculated based on the known vapor pressure at the bubbler temperature and the ratio of the two gas flows. The concentration C is given by: ( C = \frac{Q{saturated} \times P{vapor}(T) / P{total}}{Q{saturated} + Q{dilution}} ) Where ( Q ) are the volumetric flow rates, ( P{vapor}(T) ) is the temperature-dependent vapor pressure, and ( P_{total} ) is the total pressure [8].

- Control: The system software adjusts MFC2 to maintain a set concentration, compensating for any drift in the saturation of the primary stream.

Advantages: This method directly controls the molar flow rate of the precursor, making it highly stable and less sensitive to small temperature fluctuations in the bubbler compared to pressure-based control alone [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Equipment for Vapor Pressure and Stability Management

| Tool / Solution | Primary Function | Key Application in Precursor Handling |

|---|---|---|

| Controlled Evaporation & Mixing (CEM) System [9] | Precisely evaporates a metered liquid flow and mixes it with a carrier gas. | Provides stable, repeatable vapor delivery independent of liquid level and pressure fluctuations; ideal for liquid precursors. |

| Vapor Concentration Control (VCC) Module [8] | Integrates a pressure valve and gas concentration monitor (e.g., NDIR) for closed-loop control. | Actively maintains a constant precursor concentration in the vapor stream, compensating for temperature drift. |

| Mass Flow Controller (MFC) [9] | Precisely measures and controls the flow rate of a gas. | Foundational component for carrier and dilution gas control in CEM, VCC, and bubbler systems. |

| Online Vapor Pressure Analyzer (e.g., RVP-4) [5] | Directly measures the vapor pressure of petroleum products and other liquids inline. | Critical for quality control and process optimization in handling volatile hydrocarbon streams and solvents. |

| Machine Learning Volatility Model [11] | Predicts evaporation/sublimation temperature of organometallic complexes from chemical structure. | Enables in silico screening and design of novel precursors with optimized volatility before synthesis. |

| MC-betaglucuronide-MMAE-1 | MC-betaglucuronide-MMAE-1, CAS:1703778-92-0, MF:C66H98N8O20, MW:1323.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Interleukin II (60-70) | Interleukin II (60-70), MF:C68H104N14O14S, MW:1373.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow & Conceptual Diagrams

Precursor Stability Decision Workflow

Vapor Control System Architecture

FAQs on Volatility and Ligand Design

What is volatility in the context of inorganic precursors? Volatility describes how readily a substance vaporizes. For chemical vapor deposition (CVD) and atomic layer deposition (ALD) techniques, precursors must be volatile enough to be delivered as a vapor to the reaction chamber without decomposing from excessive heating [13] [11].

How does ligand structure directly influence a complex's volatility? The molecular design dictates volatility through two primary factors:

- Intermolecular Forces: Bulky, fluorinated ligands reduce intermolecular interactions by creating steric hindrance and lowering surface energy, enhancing volatility [14] [13].

- Molecular Weight and Symmetry: While lower molecular mass can aid volatility, molecular symmetry often has a more significant impact by enabling efficient packing in the solid state or a lower-energy vapor phase [13].

What are heteroleptic complexes, and why are they promising for precursor design? Heteroleptic complexes contain a central metal atom bound to two or more different types of ligands. This design allows a chemist to fine-tune the precursor's properties strategically. For instance, one ligand can provide thermal stability, while another can enhance volatility or control the reactivity during deposition [14] [10].

What is the specific advantage of using beta-diketonate ligands like 'ptac' or 'tmhd'?

Beta-diketonates are bidentate chelating ligands (they bind to the metal with two atoms). Their key advantage lies in their substitutable terminal groups. Incorporating bulky alkyl groups (e.g., in tmhd) or fluorine atoms (e.g., in ptac) increases volatility by shielding the metal center and reducing intermolecular interactions [14].

Can you give an example of ligand structure improving thermal properties?

Research on Li-Ni heteroleptic complexes shows that using the acacen Schiff base ligand with lithium β-diketonates like ptac results in stable, volatile compounds suitable as single-source precursors (SSPs). The combination of different ligands stabilizes the diverse coordination environments of lithium and nickel, delivering both stability and volatility [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Precursor Exhibits Low Volatility or Decomposes Upon Heating

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Excessive intermolecular interaction | Perform Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA). A slow, gradual weight loss over a wide temperature range suggests strong intermolecular forces. | Redesign ligands to include bulkier, sterically-hindering groups (e.g., tert-butyl) or introduce fluorinated groups (e.g., -CF3) to reduce intermolecular attraction [14]. |

| Precursor is oligomeric/polymeric | Determine molecular structure via X-ray crystallography or assess molecular weight in solution. | Synthesize heteroleptic complexes where different ligands are chosen to saturate the metal's coordination sphere, thereby breaking up polymeric networks and creating discrete, volatile molecules [14]. |

| Thermal lability of ligands | Use techniques like Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) to detect exothermic decomposition events. | Replace thermally sensitive ligands with more robust alternatives, such as moving from a salen-type ligand to an acacen derivative, which are known to be more volatile and potentially more stable [14]. |

Problem: Inconsistent Thin Film Composition from a Single-Source Precursor (SSP)

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Ligand exchange or precursor dissociation | Use in-situ mass spectrometry to monitor the vapor phase during heating. Different species indicate dissociation. | Employ chelating ligands that form stable, rigid coordination complexes with the metal ions, minimizing ligand rearrangement or loss before deposition [14]. |

| Incompatible thermal behavior of metal centers | Perform simultaneous TGA-DSC to see if vaporization is a single, clean event. Multiple endotherms suggest segregation. | Develop heterobimetallic complexes where ligands are specifically matched to each metal's coordination needs, ensuring the molecule vaporizes as a single unit [14]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Measurements

Protocol: Assessing Volatility via Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

Purpose: To determine the temperature at which a precursor vaporizes and to check for thermal decomposition.

Materials:

- Thermogravimetric Analyzer

- High-purity alumina or platinum sample pans

- Inert gas supply (e.g., N2 or Ar)

- Sample of the precursor complex

Procedure:

- Calibration: Calibrate the TGA instrument for temperature and weight according to the manufacturer's guidelines.

- Loading: Tare a clean sample pan. Precisely weigh 5-10 mg of the solid or liquid precursor into the pan.

- Parameters: Place the pan in the TGA furnace. Purge the system with an inert gas (e.g., N2) at a constant flow rate (e.g., 50 mL/min).

- Temperature Program: Run a dynamic heating program from room temperature to 400-500°C at a controlled ramp rate (e.g., 5-10°C/min).

- Data Analysis: Plot weight % versus temperature. The onset temperature of rapid weight loss indicates volatility. A single, sharp step is ideal. A residual mass at high temperature suggests decomposition.

Protocol: Synthesis of a Heteroleptic Li-Ni Complex

Purpose: To synthesize a volatile, heterometallic single-source precursor via cocrystallization [14].

Materials:

- Ni(acacen) complex (metalloligand)

- Lithium beta-diketonate (e.g., Li(ptac))

- Anhydrous, deoxygenated organic solvent (e.g., THF or acetonitrile)

- Schlenk line or glovebox for air-free manipulations

- Glassware for vacuum sublimation

Procedure:

- Purification: Purify the starting monometallic complexes, Ni(acacen) and Li(ptac), separately by vacuum sublimation [14].

- Reaction: In an inert atmosphere, dissolve stoichiometric amounts of the purified Ni(acacen) and Li(ptac) in a minimum amount of organic solvent.

- Cocrystallization: Gently concentrate the solution under reduced pressure or allow slow evaporation at low temperature to promote cocrystallization.

- Isolation: Collect the resulting crystalline solid.

- Characterization: Confirm the molecular structure of the heteroleptic complex [Ni(acacen)Li(ptac)] using techniques like NMR spectroscopy, FT-IR, and single-crystal X-ray diffraction. Assess its purity and volatility via TGA.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key ligands and reagents used in the design of volatile precursors, based on the cited research.

| Reagent/Ligand | Function in Precursor Design | Key Structural Feature |

|---|---|---|

| Schiff Bases (e.g., acacen) | Acts as a stabilizing "metalloligand" for the transition metal ion (e.g., Ni²âº), forming one part of a heteroleptic complex [14]. | Tetradentate chelating ligand; the acacen variant is noted to provide higher volatility than salen analogues [14]. |

| β-diketonates (e.g., tmhd, ptac) | Serves as a ligand for the alkali metal (e.g., Liâº) in heterometallic complexes. The terminal groups are critical for tuning volatility [14] [10]. | Bulky alkyl groups (tmhd) or fluorine atoms (ptac) shield the metal core and reduce intermolecular interactions. |

| Lithium β-diketonates (e.g., Li(tmhd)) | The source of lithium in heterobimetallic precursors. Cocrystallizes with transition metal complexes to form a single molecule [14]. | The anionic β-diketonate ligand coordinates to Liâº, while the entire unit assembles with the transition metal complex. |

| Molybdenum Chloride (MoClâ‚…) | A common, commercially available starting material for synthesizing more complex molybdenum precursors [10]. | High Lewis acidity; undergoes ligand exchange reactions to form liquid, volatile heteroleptic complexes. |

Ligand Design and Volatility Relationship Diagram

The diagram below visualizes the logical relationship between ligand properties, design strategies, and the resulting precursor performance.

Ligand Design Impact on Performance

Quantitative Data on Precursor Performance

The table below summarizes thermal property data for selected metal-organic precursors from the research, illustrating the impact of ligand structure.

| Precursor Complex | Ligand Types & Key Features | Volatility / Thermal Data (from TGA) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| [Ni(acacen)Li(ptac)] [14] | Schiff Base (acacen) + Fluorinated β-diketonate (ptac) |

Stable and volatile; sublimation reported for similar complexes at 180–220°C (at 10â»Â² Torr) [14]. | Fluorination and heteroleptic design yield a suitable Single-Source Precursor (SSP). |

| [Ni(acacen)Li(tmhd)] [14] | Schiff Base (acacen) + Bulky Alkyl β-diketonate (tmhd) |

Data reported; compound is stable and volatile [14]. | Bulky alkyl groups effectively enhance volatility. |

| MoCl₂(thd)₂ [10] | Heteroleptic; Two bulky alkyl β-diketonates (thd) |

Exists as a liquid at room temperature; exhibits excellent volatility and thermal stability [10]. | Liquid state and constant vapor pressure are achieved via ligand design. |

| MoClâ‚… (for comparison) [10] | Homoleptic Chloride | Solid at room temperature; can suffer from heterogeneous sublimation [10]. | Highlights the improvement gained by using designed organic ligands. |

FAQs: Addressing Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ 1: What are the primary causes of low precursor delivery in vapor deposition processes and how can this be mitigated? Low precursor delivery is predominantly caused by insufficient volatility or thermal decomposition during vaporization. A precursor might have an inherently low vapor pressure or may decompose before it can effectively vaporize, leading to inconsistent delivery and flawed film deposition. To mitigate this, select or design precursors with high volatility and thermal stability. Strategies include using liquid precursors (e.g., MoCl₂(thd)₂) over solid ones, as they offer more consistent vapor pressure and are less prone to decomposition during vaporization [10]. Furthermore, machine learning models can now predict evaporation temperatures for organometallic complexes with an accuracy of ±9°C, allowing for the computational screening of precursors with optimal volatility before experimental synthesis [11].

FAQ 2: Why does my solid-state synthesis reaction fail to produce the target material, and how can I troubleshoot the pathway? Failed solid-state synthesis often results from sluggish reaction kinetics or the formation of stable intermediate phases that consume the driving force to form the target. To troubleshoot, analyze the reaction pathway. Techniques like X-ray diffraction (XRD) can identify stable intermediate phases that act as kinetic barriers [15]. An active-learning approach can then propose improved synthesis routes by prioritizing precursor combinations that avoid these intermediates or form intermediates with a larger thermodynamic driving force (e.g., >50 meV per atom) to proceed to the final target [15].

FAQ 3: How do I determine the thermal stability of a new compound or mixture to assess its processing risks? Thermal stability is best determined through calorimetric techniques. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) measures mass loss as a function of temperature, identifying decomposition onset temperatures [16]. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) detects exothermic or endothermic events, such as decomposition energy (ΔHd) [17]. For a complete hazard assessment under worst-case scenarios, Adiabatic Rate Calorimetry (ARC) can be used to determine key safety parameters like the time to maximum rate under adiabatic conditions (TMRad) and adiabatic temperature rise (ΔTad) [17].

FAQ 4: What does a bond dissociation energy (BDE) value tell me, and how should I interpret different values for the same bond in different molecules? Bond Dissociation Energy (BDE) is the standard enthalpy change required to break a chemical bond via homolysis, producing two radical fragments [18]. It is a direct measure of bond strength. However, BDE is not an intrinsic property of a bond type alone; it is highly dependent on the molecular context. For example, the C=C BDE is 174 kcal/mol in ethylene but only 79 kcal/mol in ketene because the products of ketene cleavage (CO and methylene) are much more stable [18]. Therefore, when comparing BDEs, one must account for the stability of the resulting radical species and the overall molecular environment.

Data Tables: Key Quantitative Comparisons

This table provides average values for common bonds; the exact BDE can vary with molecular context.

| Bond | Type | Bond-dissociation Enthalpy (kcal/mol) | Bond-dissociation Enthalpy (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| H–H | Single | 103 | 431 |

| C–C | Single (in alkane) | 83-90 | 347-377 |

| C=C | Double | 174 (in ethylene) | 728 (in ethylene) |

| C≡C | Triple | 230 (in acetylene) | 962 (in acetylene) |

| C–H | Single | 99 (average in CH₄) | 414 (average in CH₄) |

| C–F | Single (in CH₃F) | 115 | 481 |

| Si–F | Single (in H₃Si–F) | 152 | 636 |

| O–H | Single (in water) | 110.3 (average) | 461.5 (average) |

| N≡N | Triple | 226 | 945 |

T₀: Exothermic onset temperature; ΔHd: Heat of decomposition.

| Compound / Parameter | Decomposition Onset (Tâ‚€) | Heat of Decomposition (ΔHd) | Activation Energy (Eâ‚) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TMCH (1,1-di-tert-butyl peroxy-3,3,5-trimethyl cyclohexane) | Varies with heating rate [17] | Measured via DSC & ARC [17] | - |

| Ciprofloxacin (CIP) | 280 °C [16] | - | 58.09 kJ/mol (KAS model) [16] |

| Ibuprofen (IBU) | 152 °C [16] | - | 11.37 kJ/mol (KAS model) [16] |

| CIP + IBU Mixture | 157 °C [16] | - | 41.09 kJ/mol (KAS model) [16] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determination of Thermal Stability and Decomposition Kinetics via TGA/DSC

Objective: To characterize the thermal stability, degradation steps, and kinetic parameters of a compound.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Place approximately 5 mg of the sample into a platinum crucible [16].

- Atmosphere Control: Purge the furnace with an inert gas like argon for at least 15 minutes to create an oxygen-free environment [16].

- Programmed Heating: Heat the sample from room temperature to a target temperature (e.g., 700°C) at multiple, controlled heating rates (e.g., 2, 6, 8, 10, 16 °C/min) [17] [16].

- Data Collection:

- Kinetic Analysis: Analyze the TGA data using model-fitting (e.g., Coats-Redfern) and/or model-free (e.g., Kissinger-Akahira-Sunose (KAS), Flynn-Wall-Ozawa (FWO)) methods to determine kinetic parameters like activation energy (Eâ‚) and reaction order [16].

Protocol 2: Synthesis of Volatile Liquid Precursors for Vapor Deposition

Objective: To synthesize a liquid molybdenum precursor with high volatility and thermal stability for thin-film deposition [10].

Methodology (for MoClâ‚‚(thd)â‚‚):

- Reaction Setup: Perform all manipulations under a dry, inert atmosphere (e.g., argon) using Schlenk techniques or a glovebox [10].

- Precursor Dissolution: Dissolve solid MoCl₅ in tetrahydrofuran (THF) at 0°C to control exothermic solvation [10].

- Ligand Exchange: Slowly add two equivalents of lithium 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-3,5-heptanedionate (Li-thd) to the cooled MoClâ‚… solution with stirring [10].

- Product Isolation: After completing the reaction, remove the solvent under reduced pressure. Purify the resulting liquid product via distillation or other suitable methods [10].

- Characterization: Characterize the product using Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, and TGA to confirm structure, purity, and volatility [10].

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Thermal Analysis and Vapor Deposition

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Alumina (Al₂O₃) Crucibles | Inert containers for holding powder samples during high-temperature synthesis or TGA/DSC experiments [15]. |

| Lithium 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-3,5-heptanedionate (Li-thd) | A key chelating ligand used in the synthesis of volatile metal-organic precursors (e.g., for Mo) for CVD/ALD, improving volatility and thermal stability [10]. |

| Argon (Ar) Gas | An inert atmosphere used to purge furnaces and reaction vessels, preventing oxidation or other unwanted side reactions during thermal analysis and precursor synthesis [16] [10]. |

| Tetrahydrofuran (THF) | A common anhydrous solvent used in air-sensitive synthesis, such as the preparation of organometallic precursors [10]. |

| MoClâ‚… | A common solid starting material for synthesizing more complex and volatile molybdenum precursors for thin-film deposition [10]. |

| 1a,1b-dihomo Prostaglandin E2 | 1a,1b-dihomo Prostaglandin E2, MF:C22H36O5, MW:380.5 g/mol |

| eeAChE-IN-3 | eeAChE-IN-3, MF:C18H25N3O4, MW:347.4 g/mol |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: My computational model shows a material is stable, but experimental synthesis fails due to precursor decomposition. What's wrong? A: This common issue often stems from the modeling approach overlooking precursor volatility and reaction kinetics. Standard Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations typically focus on bulk material stability but may miss fine thermodynamic balances governing precursor behavior. We recommend using machine learning models specifically trained on organometallic precursor data, which can predict evaporation or sublimation temperatures with ±9°C accuracy, helping select precursors that remain stable during vaporization [11].

Q: How can I accurately model triangular Fe(III) centers in MOFs when standard DFT gives distorted structures? A: Standard DFT often assumes ferromagnetic high-spin configurations, overlooking spin-frustration effects. The true ground state is an antiferromagnetic M = 6 state that requires flip-spin DFT methods. By explicitly accounting for spin-frustration, you can recover correct structures and rationalize temperature-dependent binding behavior, which significantly impacts predictions of stability and reactivity [19].

Q: What computational approaches help overcome sluggish reaction kinetics in solid-state synthesis? A: When reactions have low driving forces (<50 meV per atom), consider active learning approaches that integrate computed reaction energies with experimental outcomes. The A-Lab framework successfully uses this method to identify alternative synthesis routes with improved driving forces. For example, avoiding intermediates with small driving forces (8 meV per atom) and selecting pathways with larger forces (77 meV per atom) can increase target yields by approximately 70% [15].

Q: How can I balance computational accuracy with efficiency when screening precursor molecules? A: Implement a multi-scale approach: use fast machine learning models for initial screening of hundreds of complexes (seconds per calculation), then apply higher-level DFT methods for promising candidates. Semiempirical quantum methods like GFN2-xTB offer broad applicability with significantly reduced computational cost, making them valuable for large-scale screening and geometry optimization [20] [11].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Machine Learning Prediction of Precursor Volatility

Purpose: To accurately predict evaporation/sublimation temperatures for inorganic and organometallic complexes to inform synthesis planning.

Materials:

- Chemical structures of precursor complexes

- Access to trained machine learning models (Random Forest or Neural Networks)

- Chemoinformatic descriptors and fingerprints

Procedure:

- Data Collection: Collate and digitize precursor information from literature sources, including structural features and experimental volatility data [11].

- Feature Engineering: Calculate molecular descriptors and fingerprints that capture relevant structural properties influencing volatility.

- Model Training: Apply machine learning algorithms to establish structure-volatility relationships using historical experimental data.

- Prediction: Use trained model to compute evaporation/sublimation temperatures for new precursor candidates.

- Validation: Compare predictions with experimental measurements where available; expected accuracy should reach ±9°C (approximately 3% of absolute temperature).

Applications: This protocol enables rapid screening of hundreds of structural modifications computationally before committing to experimental synthesis and testing [11].

Protocol 2: Active Learning for Synthesis Optimization

Purpose: To autonomously optimize solid-state synthesis recipes for novel inorganic materials.

Materials:

- Target material composition

- Potential precursor sets

- Robotic synthesis and characterization platform

- Access to ab initio phase-stability data

Procedure:

- Initial Recipe Generation: Propose up to five initial synthesis recipes using ML models trained on literature data through natural-language processing [15].

- Temperature Selection: Determine optimal synthesis temperature using ML models trained on heating data from literature [15].

- Experimental Execution: Perform synthesis using automated robotics for powder dispensing, mixing, and heating in box furnaces.

- Characterization: Analyze products using X-ray diffraction with automated phase identification and weight fraction analysis.

- Active Learning: If yield is below 50%, use ARROWS3 algorithm to propose improved recipes based on observed reaction pathways and computed reaction energies.

- Iteration: Continue until target is obtained as majority phase or all recipe options are exhausted.

Key Principle: The system prioritizes reaction pathways that avoid intermediate phases with small driving forces to form the target, instead selecting routes with larger thermodynamic driving forces [15].

Research Reagent Solutions

Key Computational Tools and Methods

| Tool/Method | Function | Application in Stability-Reactivity Trade-off |

|---|---|---|

| Flip-spin DFT | Models spin-frustration in triangular metal centers | Correctly identifies ground states in MOFs with Fe(III) nodes; prevents structural distortions [19] |

| Machine Learning Volatility Models | Predicts evaporation/sublimation temperatures | Screens precursor candidates for vapor-phase deposition; avoids thermal decomposition [11] |

| Active Learning (ARROWS3) | Optimizes solid-state synthesis routes | Identifies reaction pathways with sufficient driving forces; overcomes kinetic barriers [15] |

| Hybrid QM/MM | Combines quantum and molecular mechanics | Models complex environments like biomolecular systems and solvated phases [20] |

| Fragment Molecular Orbital (FMO) | Enables localized quantum treatments | Handles large systems like enzymatic reactions and ligand binding [20] |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Computational Synthesis Workflow

Diagram 2: Precursor Volatility Prediction

Diagram 3: Spin-Frustration Modeling

Practical Strategies for Volatility Management: Protocols, Equipment, and Workflow Integration

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Bubbler Systems

| Problem Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution | Prevention Tip |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent precursor delivery rate | Carrier gas flow rate fluctuations; Temperature instability in bubbler bath. | Check mass flow controller (MFC) calibration; Stabilize bath temperature & check thermoregulator. | Use a temperature-controlled bath with high thermal stability. |

| Decreasing evaporation rate over time | Precursor depletion in bubbler; Cooling of liquid due to heat of vaporization. | Refill or replace bubbler; Use a bubbler with construction materials of high specific heat. | Monitor precursor level; Ensure bubbler design has high thermal conductivity [21]. |

| Two-phase flow (liquid aerosol carryover) | Gas flow rate too high; Gas inlet tube submerged too deeply. | Reduce carrier gas flow rate; Adjust gas inlet tube to be just below liquid surface. | Optimize and validate carrier gas flow rates for your specific precursor. |

| Clogging of gas lines | Precursor condensation in delivery lines; Precursor decomposition. | Heat delivery lines above precursor condensation point; Verify precursor stability at operating temps. | Fully heat-trace and insulate all delivery lines between bubbler and reactor. |

| Crystallization of solid precursors | Precursor melting point is too high; Temperature is too low. | Use a hotter heating jacket to melt precursor & keep lines hot; Consider a different precursor. | Select precursors with suitably low melting points for bubbler use. |

Troubleshooting Vaporizer Systems

| Problem Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution | Prevention Tip |

|---|---|---|---|

| "Bumping" or sudden violent boiling | Rapid pressure drop or superheating; Incompatible solvent (e.g., DMSO, DMF). | Apply vacuum gradually; Lower vaporizer bath temperature [22]. | For prone solvents, use a system designed for ambient pressure evaporation [22]. |

| Poor vaporization efficiency for high-boiling solvents | Insufficient thermal energy input; Low vapor pressure of solvent. | Increase vaporizer temperature; Switch to a system designed for high-boiling solvents [22]. | Understand the vapor pressure profile of your solvent relative to temperature [21]. |

| Precursor decomposition | Temperature set too high; Residence time in vaporizer too long. | Lower the vaporizer temperature; Increase carrier gas flow to reduce residence time. | Determine the thermal decomposition temperature of your precursor and operate well below it. |

| Leaks or loss of vacuum | Failed O-rings or seals; Improperly seated components. | Inspect and replace O-rings; Ensure all fittings are properly seated and tightened [22]. | Perform regular preventive maintenance and leak checks on the entire system. |

| Carryover of droplets into reactor | Incomplete vaporization; Splashing due to "bumping". | Ensure adequate heat input; Use a vaporizer with baffles or wicks to increase surface area [21]. | Do not exceed the recommended fill volume for the vaporization chamber. |

Troubleshooting Direct Liquid Injection (DLI) Systems

| Problem Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution | Prevention Tip |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unstable liquid flow | Bubbles in syringe or lines; Viscosity changes with temperature. | Prime lines to remove bubbles; Use syringe heater to maintain constant viscosity. | Degas solutions before filling syringe; Use a temperature-controlled syringe holder. |

| Precursor deposition/clogging in injector | Vaporization occurring too slowly; Reactor pressure back-streaming. | Ensure vaporizer is at correct temperature; Use an inert gas shroud to protect the injector. | Use a high-temperature vaporizer capable of instantaneously flash-vaporizing the droplet stream. |

| Inaccurate liquid flow rate | Syringe pump calibration drift; Incorrect syringe size selected in software. | Re-calibrate syringe pump; Verify syringe size setting in pump control software. | Perform regular calibration checks of the syringe pump, especially for low flow rates. |

| Pulsating flow from pump | Stepper motor resolution is too coarse for low flow rates. | Dilute precursor to allow for higher flow rates; Use a pump with finer resolution. | Select a syringe pump designed for highly precise, pulseless flow at µL/min rates. |

| Needle seat leakage | Damaged or worn needle; Particulate matter on seat. | Inspect and replace needle; Flush and clean system. | Use high-purity, particle-free solutions; Follow manufacturer's maintenance schedule. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the most critical factor for maintaining a stable evaporation rate from a bubbler? The most critical factor is temperature stability. The vapor pressure of a precursor, which dictates its evaporation rate, is highly dependent on its temperature [21]. Any fluctuation will directly alter the output concentration. Furthermore, as the liquid evaporates, it cools down (latent heat of vaporization), which can lower the vapor pressure over time. Using a bath with high-precision temperature control and a bubbler constructed from materials with high specific heat and thermal conductivity helps to minimize this effect and maintain a consistent rate [21].

Q2: When should I consider an alternative to a standard rotary evaporator for solvent removal? You should consider an alternative when working with high-boiling point solvents (like DMSO or water), sensitive compounds that can be damaged by heat or vacuum, or when you experience persistent problems with bumping and sample loss [22]. In these cases, systems like the Smart Evaporator, which uses a controlled vortex at ambient pressure, can be a valuable complement to your rotary evaporator, as they eliminate the risk of bumping by design [22].

Q3: My DLI system keeps clogging. What are the primary causes? Clogging in a DLI system typically stems from two issues:

- Incomplete/Vaporization: If the liquid droplets are not fully and instantaneously vaporized upon entering the hot zone, the precursor can deposit and build up on the injector tip or walls, eventually leading to a clog.

- Precursor Decomposition: If the temperature of the vaporizer is too high, the precursor can thermally decompose into non-volatile solid residues that coat and block the injector. Optimizing the vaporizer temperature and ensuring a well-designed mixing zone with a pre-heated carrier gas are key to preventing clogs.

Q4: How can I safely handle precursors that are peroxide-formers? Peroxide-forming chemicals, like many ethers, require special care as the peroxides can be explosively unstable [23].

- Purchase & Storage: Buy minimum quantities, date containers upon opening, and store under an inert atmosphere (argon or nitrogen) away from light and heat [23].

- Testing: Test for peroxides every 3 months using test strips. If hazardous levels are found, either treat to remove peroxides or dispose of the chemical properly [23].

- Distillation: Avoid distillation if possible. If necessary, test for peroxides first, add a reducing agent (e.g., sodium/benzophenone), do not carry to dryness, and use a safety shield [23].

Q5: What are the key safety precautions for general chemical handling in the lab? Always follow these fundamental principles [24]:

- Plan Ahead: Determine potential hazards before starting an experiment.

- Minimize Exposure: Use engineering controls (like fume hoods) and personal protective equipment (PPE) to prevent skin contact and inhalation.

- Do Not Underestimate Risks: Assume mixtures are more toxic than their most toxic component. Treat substances of unknown toxicity as toxic.

- Be Prepared for Accidents: Know the location of safety equipment and how to respond to spills or exposures. Never work alone [24] [23].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Workflow for Precursor Delivery System Selection and Operation

This diagram outlines the logical decision-making process for selecting and safely operating a precursor delivery system.

Protocol: Establishing a Stable Bubbler Delivery System

Objective: To reliably deliver a consistent concentration of a volatile liquid precursor to a reaction chamber using a bubbler.

Materials:

- Purified precursor liquid

- Carrier gas source (e.g., Nâ‚‚, Ar) with Mass Flow Controller (MFC)

- Temperature-controlled oil or aluminum bath

- Bubbler assembly with frit and temperature sensor

- Heated and insulated gas delivery lines

- Tool for analyzing output concentration (e.g., QCM, FTIR)

Methodology:

- Setup: Fill the bubbler with the precursor liquid, ensuring not to overfill. Assemble the system, ensuring all connections are gas-tight.

- Stabilization: Set the carrier gas flow rate based on your desired precursor molar flow. Turn on the temperature-controlled bath and set it to the desired temperature. Crucially, allow the bath and bubbler to thermally equilibrate for at least 30-60 minutes before introducing carrier gas. This ensures the precursor is at the setpoint temperature [21].

- Conditioning: Open the carrier gas valve to the predetermined flow rate and allow the system to run until the output stabilizes. This can be monitored with an in-situ analysis tool.

- Verification: Periodically check the precursor consumption and the stability of the process output (e.g., film growth rate, QCM frequency) to confirm the delivery rate is constant.

- Shutdown: When finished, turn off the carrier gas flow first, then lower the bath temperature.

Protocol: Optimizing a Direct Liquid Injection (DLI) System

Objective: To achieve precise, pulsed-free delivery and complete vaporization of a liquid precursor solution into a reactor.

Materials:

- Precursor solution (degassed)

- High-precision syringe pump

- DLI vaporizer (high-temperature, low dead-volume)

- Heated syringe and transfer lines

- Inert gas shroud line

- Reactor with pressure control

Methodology:

- Preparation: Load a gas-tight syringe with the degassed precursor solution. Mount it securely in the pump. Set the pump to the desired flow rate and ensure the correct syringe diameter is selected in the software.

- Heating: Power on the DLI vaporizer and set it to a temperature high enough to fully and instantaneously flash-vaporize the liquid droplet stream but below the precursor's decomposition temperature. Turn on heating for the syringe and transfer lines to prevent condensation and viscosity changes.

- Flow Stabilization: With the reactor under vacuum and the carrier/shroud gases flowing, start the syringe pump. Observe the pressure in the vaporizer/manifold for stability, which indicates proper vaporization.

- Optimization: If pulsation is observed or clogging occurs, adjust parameters. This may include slightly increasing the vaporizer temperature, ensuring the shroud gas is active, or verifying the syringe pump calibration.

- Termination: To stop, halt the syringe pump first. Continue flowing carrier/shroud gas for a few minutes to clear the injector of any residual vapor. Then, shut down the heaters and gases.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Mass Flow Controller (MFC) | Precisely measures and controls the flow rate of carrier gases. | Essential for maintaining a consistent molar flow of precursor in bubbler and vaporizer systems. |

| Temperature-Controlled Bath | Maintains a stable, precise temperature for bubblers. | Look for high stability; required because vapor pressure is temperature-dependent [21]. |

| High-Precision Syringe Pump | Delays a precise, continuous, or pulsed flow of liquid for DLI systems. | Critical for accurate dosing; resolution is key for low flow rates and small sample volumes. |

| Flash Vaporizer | Instantaneously vaporizes liquid droplets from a DLI injector. | Must have low dead-volume, rapid heating response, and temperature control to prevent decomposition. |

| Quantofix Peroxide Test Strips | Detects and semi-quantifies peroxide levels in solvents [23]. | Safety Essential: For regularly testing peroxidizable chemicals like diethyl ether and tetrahydrofuran. |

| Ceramic Spatulas | For handling solid peroxides and other shock-sensitive materials. | Safety Essential: Metal spatulas can catalyze explosive decomposition of peroxides [23]. |

| Anhydrous Magnesium Sulfate (MgSOâ‚„) | A common drying agent to remove water from organic solutions. | Can be used to dry solvents prior to evaporation to prevent droplet formation in the rotavap [25]. |

| Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) | Minimum: Lab coat, safety glasses, appropriate gloves. Enhanced: Face shield, chemical apron. | Safety glasses with side shields are the minimum; chemical splash goggles or face shields are needed for splash risks [24]. |

| VB1080 | VB1080, MF:C27H27N3O3, MW:441.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| PSTi8 | PSTi8, MF:C98H155N29O41S, MW:2427.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Safety-Centered Handling Protocols for Pyrophoric, Toxic, and Air-Sensitive Precursors

Fundamental Concepts and Hazards

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the common examples of pyrophoric and air-sensitive materials encountered in inorganic synthesis? Pyrophoric materials react violently upon exposure to air or moisture. Common examples include [26]:

- Organo-metallic reagents: Such as Grignard reagents and alkyllithium compounds (e.g., butyllithium).

- Alkali earth elements: Sodium, potassium, and cesium.

- Finely divided metals: Raney nickel, aluminum powder, and zinc dust.

- Metal hydrides: Sodium hydride and lithium aluminum hydride.

- Gases: Arsine, diborane, and phosphine.

Q2: What are oxidizing chemicals and why are they particularly hazardous? Oxidizing chemicals spontaneously evolve oxygen at room temperature or promote combustion [27]. This class includes peroxides, perchlorates, chlorates, and nitrates. They are hazardous because they can form explosive mixtures when combined with combustible, organic, or easily oxidized materials [27].

Q3: What is the primary engineering control for handling these sensitive precursors? A properly functioning fume hood is essential. For procedures involving pyrophorics or reactions with risk of explosion, the sash should be lowered as far as possible, ideally to 18 inches or less, to provide a physical barrier and contain potential splashes or violent reactions [26] [27]. Using a glovebox is the recommended method for handling pyrophoric materials whenever possible [26].

Experimental Protocols and Troubleshooting

Workflow for Handling Air-Sensitive Reagents

The following diagram outlines the critical decision points and procedures for safely working with air-sensitive reagents.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Q4: During a transfer, my cannula became blocked. What should I do?

- Problem: Blocked cannula.

- Immediate Action: Do not attempt to clear it by applying excessive gas pressure. Close any valves on your Schlenk line to isolate the system.

- Solution: Under the protection of inert gas, carefully disconnect the blocked cannula and replace it with a new, dry one. Ensure your reagent is free of particulates that could cause blockages by cannulating from the top of the solution, not the bottom sediment.

Q5: I suspect a small spill of a pyrophoric reagent has occurred in the fume hood. What are the first steps?

- Problem: Small spill of pyrophoric material.

- Immediate Action: If you can do so safely, contain the spill by covering it with powdered lime, which is hygroscopic and can slow the reaction with air and humidity [26]. A Met-L-X fire extinguisher is also appropriate for fires involving these materials [26].

- Critical Safety Note: Do not attempt to clean up the spill yourself [26]. Evacuate the immediate area, alert personnel in the lab, and contact emergency services (e.g., Public Safety) immediately [26].

Q6: After opening a sure-seal bottle, the septum appears degraded. Is it still safe to use?

- Problem: Degraded transfer septum.

- Action: Do not use. A compromised septum can allow air and moisture to enter the container, potentially causing the reagent to decompose or ignite. You must replace the container or transfer the contents to a new, properly sealed vessel under an inert atmosphere. Always visually inspect septa for degradation before use [26].

Emergency Procedures and Material Compatibility

Essential Safety Equipment and Responses

Q7: What personal protective equipment (PPE) is mandatory for handling pyrophoric chemicals? Leather, closed-toe shoes are preferred [26]. A face shield and chemical splash goggles are required for full facial protection [26]. Wear a cloth lab coat (not plastic, which can melt) and gloves made of a material resistant to the specific reagent [26]. Fire-resistant outer gloves are recommended [26].

Q8: My clothing has been contaminated with a pyrophoric liquid. What is the correct response?

- Stop, Drop, and Roll if you are not within a few feet of a safety shower [26].

- Immediately go to the safety shower and pull the handle [26].

- Remove contaminated clothing while under the shower to ensure copious amounts of water flush away the reactive material and absorbed heat [26]. If you have significant amounts of dry reactive compound on you, you may brush off the bulk before entering the shower, but only if it is not already reacting [26].

Q9: What type of fire extinguisher is appropriate for a pyrophoric chemical fire? Standard ABC or COâ‚‚ extinguishers can cause some pyrophorics to react more vigorously and are not recommended [26]. A Met-L-X extinguisher (rated for metal fires) or powdered lime should be available in the lab for controlling fires involving pyrophoric materials [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Materials for Handling Air-Sensitive and Pyrophoric Reagents

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Double-tipped Needle (Cannula) | Allows for safe transfer of liquid reagents between sealed containers under a positive pressure of inert gas, preventing exposure to air [26]. |

| Gas-tight Syringe | Used for withdrawing smaller quantities (<50 mL) of liquid reagent from sealed containers when an inert gas source is provided to displace the volume [26]. |

| Inert Gas Source (Nâ‚‚ or Ar) | Used to purge air from apparatus and maintain an inert atmosphere during reactions and transfers. Note: Nitrogen is not suitable for all materials; consult Safety Data Sheets (SDS) [26]. |

| Mineral Oil Bubbler | Incorporated into gas lines to prevent backflow of air into the reaction apparatus and to allow monitoring of gas flow rates [26]. |

| Septum | Secured with vacuum grease to fittings, these provide air-tight seals for withdrawal and addition ports on reaction vessels and reagent bottles [26]. |

| Powdered Lime / Met-L-X Extinguisher | Used to cover spills and slow reactions with air/humidity (lime) or extinguish fires (Met-L-X). ABC/COâ‚‚ extinguishers can worsen pyrophoric fires [26]. |

| BRD6989 | BRD6989, MF:C16H16N4, MW:264.32 g/mol |

| PROTAC SOS1 degrader-10 | PROTAC SOS1 degrader-10, MF:C51H63F3N10O6, MW:969.1 g/mol |

Material Compatibility and Storage

Table 2: Storage and Handling Requirements for Hazardous Precursors

| Chemical Category | Temperature | Environment | Key Segregation Rules |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pyrophoric Materials [26] | Room Temperature | Inert atmosphere, under solvent or oil | Segregate from water, oxidizing agents, and flammable materials. |

| Oxidizing Chemicals [27] | Cool, Dry Location | Well-ventilated area, preferably in a cool cabinet | Must be stored separately from combustible, organic, and easily oxidized materials. |

| General Chemicals [28] | Per SDS | Cool, dry, well-ventilated area | Ensure all containers are clearly labeled. Never remove chemicals from the laboratory [28]. |

Q10: How should we store oxidizing chemicals in a shared laboratory space? Oxidizers must be stored in a cool and dry location and must be segregated from all other chemicals in the laboratory [27]. Use a dedicated cabinet or secondary container to physically separate them from combustible, organic, or flammable materials. Minimize the quantities of strong oxidizers stored in the lab [27].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Issues and Solutions for Managing Precursor Volatility

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Possible Cause | Solution | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal Decomposition | Precursor degrades before vaporization in CVD/ALD processes. | Thermal stability of precursor is lower than its volatilization temperature. | Broaden the "temperature window" between vaporization and decomposition; consider alternative precursor classes (e.g., nickel xanthates). [29] [2] | |

| Unintended solid-phase intermediates form during powder synthesis. | Low driving force (<50 meV per atom) for reaction kinetics, leading to sluggish reactions and failure to form target crystalline phase. [15] | Use active learning algorithms (e.g., A-Lab's ARROWS3) to identify alternative precursor sets that avoid low-driving-force intermediates. [15] | ||

| Pressure Control | Reactions do not proceed under solvent-/catalyst-free conditions at ambient pressure. | Insufficient activation energy for the reaction to occur without traditional harsh conditions. [30] | Apply High Hydrostatic Pressure (HHP) (e.g., 3.8 kbar) to lower the activation volume and drive the reaction. [30] | |

| Optimization Challenges | Inefficient exploration of multi-variable synthesis parameter space (e.g., temperature, time, concentration). | Traditional trial-and-error is resource-intensive and slow. | Implement flexible Batch Bayesian Optimization (BBO) frameworks on high-throughput robotic platforms to efficiently identify optimal conditions. [31] | |

| Precursor Properties | Difficulty in obtaining continuous, conformal thin films or nanoparticles with controlled properties. | Precursor lacks balanced volatility, thermal stability, and reactivity. [2] | Select or design volatile silver complexes (e.g., for CVD/ALD) with tailored ligands; use aerosol-assisted or direct liquid injection MOCVD to mitigate volatility requirements. [2] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are practical strategies for balancing precursor volatility with thermal stability in vapor deposition processes?

Achieving this balance is a central challenge in CVD and ALD. The core strategy is to select or design precursors with a wide "temperature window"—a significant gap between the temperature required for vaporization and the onset of thermal decomposition. [2] For instance, in silver CVD/ALD, this can involve using specific volatile coordination compounds. If a precursor's thermal stability is inherently low, hardware modifications can help. Techniques like Aerosol-Assisted (AA-)MOCVD or Direct Liquid Injection (DLI-)MOCVD allow for the introduction of precursors in solution form, reducing the demand for high volatility and enabling the use of a broader range of precursors. [2] Furthermore, alternative activation methods such as plasma-enhanced (PE-)MOCVD can facilitate decomposition at lower temperatures, preserving the precursor during vapor transport. [2]

Q2: Can you provide an example of an autonomous experimental protocol for optimizing synthesis conditions?

Recent research demonstrates closed-loop autonomous workflows for optimizing chemical reactions. The following protocol, adapted from work on optimizing a sulfonation reaction for redox flow batteries, outlines such a process: [31]

Define Search Space: Identify the key reaction parameters (variables) and their boundaries. For example:

- Reaction Time: 30.0–600 min

- Temperature: 20.0–170.0 °C

- Sulfonating Agent Concentration: 75.0–100.0%

- Analyte Concentration: 33.0–100 mg mLâ»Â¹

- Output: Reaction yield, as determined by HPLC analysis. [31]

Initial Sampling: Use a space-filling design like Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) to generate an initial set of 15-20 distinct experimental conditions within the 4D parameter space. [31]

Hardware-Aware Adjustment: Adapt the algorithmically generated conditions to match hardware constraints. For example, if the system has only three heating blocks, cluster the LHS-generated temperatures to three centroid values and reassign conditions accordingly. [31]

High-Throughput Execution & Characterization: Execute the batch of experiments using a robotic liquid handling and synthesis platform. Transfer the resulting samples to an automated characterization station (e.g., HPLC) to measure the reaction yield. [31]

Model and Plan Next Experiments: Use the collected data (conditions and yields) to train a Gaussian Process Regression model as a surrogate for the reaction landscape. Employ an acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement) on this model to suggest the next batch of promising experimental conditions that balance exploration and exploitation. [31]

Iterate to Convergence: Repeat steps 3-5 until a predetermined optimization goal is met (e.g., yield >90%) or the budget of experiments is exhausted. This closed-loop system efficiently hones in on optimal parameters. [31]

Q3: How can high pressure be used to prevent decomposition in solvent-free synthesis?

High Hydrostatic Pressure (HHP) is a powerful non-thermal activation method that can drive reactions under exceptionally mild and green conditions. The mechanism is based on a reduction in activation volume (ΔV‡); applying high pressure (e.g., 2-4 kbar) favors reaction pathways that occupy a smaller volume in the transition state. [30] This allows reactions to proceed efficiently at room temperature without solvents or catalysts, conditions under which they would otherwise not occur or proceed very slowly. For example, the cyclization of o-phenylenediamine and acetone to form 1,3-dihydro-2,2-dimethylbenzimidazole yields 0% at ambient pressure after 10 hours. However, under 3.8 kbar of HHP for 10 hours, the same reaction proceeds cleanly with a 90% yield, effectively preventing side reactions and decomposition pathways that might occur under forced thermal conditions. [30]

Q4: What are the decomposition pathways for common single-source precursors, and how does temperature influence them?

The thermal decomposition of single-source precursors is a complex process that can be significantly influenced by the precursor's molecular structure. A detailed study on nickel xanthates revealed a two-step mechanism that diverges from the simple Chugaev elimination. [29] The process begins with an alkyl transfer between xanthate ligands, forming a symmetric intermediate. This is followed by a Chugaev-like elimination step that produces the nickel sulfide (NiS), carbonyl sulfide (COS), and an alkene. [29] The identity of the alkyl group on the xanthate ligand profoundly impacts the decomposition pathway and the resulting byproducts. Temperature control is critical not only for the decomposition but also for the phase of the final product. For nickel xanthates, low temperatures initially produce α-NiS. At higher temperatures, a phase transformation to β-NiS occurs, and the specific ligand determines whether pure phases or mixed phases are obtained. [29] This underscores the need for precise thermal profiling to achieve the desired material composition and phase.

Experimental Workflows and Pathways

Workflow for an Autonomous Synthesis Laboratory

The following diagram illustrates the integrated digital-physical workflow of a self-driving lab, as demonstrated by the A-Lab for inorganic powders and other platforms for organic molecules. [15] [31]

Optimizing Reaction Pathways to Avoid Decomposition

The A-Lab used active learning to navigate solid-state reaction pathways and avoid intermediates with low driving forces that hinder target formation. The logic below visualizes this decision-making process. [15]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Materials for Managing Volatility and Decomposition

| Item | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Source Precursors (e.g., Nickel Xanthates) | Provide pre-formed metal-chalcogen bonds, enabling lower decomposition temperatures and controlled stoichiometry for metal sulfides. [29] | The alkyl chain length and branching on the ligand tune solubility, volatility, and the specific decomposition pathway. [29] |

| Volatile Silver Complexes (for CVD/ALD) | Act as precursors for depositing silver thin films and nanoparticles in gas-phase processes. [2] | Must balance sufficient volatility, thermal stability, and clean decomposition to metallic silver without inorganic impurities. [2] |

| High Hydrostatic Pressure (HHP) Reactor | Enables solvent- and catalyst-free synthesis by reducing activation volume, driving reactions at room temperature that would otherwise require harsh conditions. [30] | Uses water as a pressure-transmitting fluid. Effective in the 2-4 kbar range for various cyclizations and esterifications. [30] |

| Bayesian Optimization Algorithm | A machine learning decision-making method that efficiently optimizes high-dimensional synthesis parameters (T, t, conc.) with minimal experiments. [31] | Particularly powerful when integrated with high-throughput experimentation (HTE) platforms as Batch BO (BBO). [31] |

| Active Learning Agent (e.g., ARROWS3) | Uses computational thermodynamics and experimental data to propose improved solid-state synthesis recipes and avoid kinetic traps. [15] | Relies on ab initio computed reaction energies and a growing database of observed pairwise reactions between solid phases. [15] |

| Hpk1-IN-47 | Hpk1-IN-47, MF:C26H27N5O, MW:425.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Tp508 | Tp508, MF:C97H146N28O36S, MW:2312.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Inert Atmosphere Glove Boxes

Problem: Oxygen (Oâ‚‚) and/or Moisture (Hâ‚‚O) levels are continuously increasing inside the glove box.

| Observation | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| A continuous increase in Oâ‚‚ and Hâ‚‚O levels when sealed [32] | Leak in the system (gloves, O-rings, seals, window) [32] | 1. Perform an automated leak test [32].2. Visually inspect gloves and O-ring seals for tears [32].3. Check all bolts around the window are tight [32].4. Spray exterior with soapy water and circulate nitrogen; look for bubbles [32]. | Replace torn gloves or damaged seals. Temporarily cover small glove tears with black electrical tape [32]. |