Machine Learning for Solid-State Synthesis: From Data Challenges to Autonomous Recipe Generation

This article explores the transformative role of machine learning (ML) in overcoming the longstanding bottleneck of predictive solid-state synthesis.

Machine Learning for Solid-State Synthesis: From Data Challenges to Autonomous Recipe Generation

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of machine learning (ML) in overcoming the longstanding bottleneck of predictive solid-state synthesis. It details the journey from foundational data acquisition via text-mining of scientific literature to the development of advanced models for recipe prediction and validation. The content covers critical challenges such as data quality, model generalizability, and the integration of ML into autonomous laboratories. Aimed at researchers and scientists, this review synthesizes current methodologies, troubleshooting strategies, and comparative analyses of different ML approaches, providing a comprehensive roadmap for leveraging artificial intelligence to accelerate the discovery and synthesis of novel materials, with significant implications for advanced drug development and biomedical applications.

The Data Foundation: Text-Mining and Challenges in Building Synthesis Knowledge Bases

The Synthesis Bottleneck in Computational Materials Discovery

The field of computational materials discovery has undergone a revolutionary transformation, powered by artificial intelligence and machine learning. Today, a single researcher can leverage machine learning tools to generate thousands of predicted candidate compounds with desired properties in mere hours, dramatically accelerating the initial stages of materials identification [1] [2]. This capability represents a fundamental shift from traditional trial-and-error approaches toward data-driven rational design. Sophisticated computational methods including generative neural networks, density functional theory (DFT) simulations, and active learning strategies can now screen enormous chemical spaces to identify promising candidate materials for applications ranging from semiconductor manufacturing to energy storage and conversion technologies [1] [3] [4].

However, a critical bottleneck emerges at the intersection of computational prediction and physical realization: materials synthesis. The challenging transition from digital prediction to physical material underscores a fundamental limitation in current materials discovery pipelines. As noted by Newfound Materials, "most of these predicted materials will never be successfully made in the lab" despite their promising computational profiles [2]. This synthesis bottleneck represents the most significant barrier to realizing the full potential of computational materials design, necessitating a concerted focus on understanding and addressing the challenges inherent in predicting and executing successful synthesis pathways.

Defining the Synthesis Bottleneck

The Fundamental Challenge: Synthesizability Versus Stability

The core of the synthesis bottleneck lies in the critical distinction between thermodynamic stability and synthesizability. While computational tools have become increasingly adept at predicting whether a material is thermodynamically stable, this property alone does not guarantee that the material can be practically synthesized [2]. As one analysis notes, "thermodynamically stable ≠synthesizable" – a fundamental limitation that plagues many computational predictions [2].

Synthesizing a chemical compound is fundamentally a pathway problem rather than an endpoint evaluation. Using an apt analogy, "Synthesizing a chemical compound is like crossing a mountain range; you can't simply go straight over the top. You need a viable path" [2]. The most direct thermodynamic route may be inaccessible due to kinetic barriers, competing phases, or precursor limitations, requiring more nuanced synthetic pathways that computational models often fail to anticipate.

This challenge is exemplified by materials such as bismuth ferrite (BiFeO₃), a promising multiferroic material that proves exceptionally difficult to synthesize without impurities like Biâ‚‚Feâ‚„O₉ or Biâ‚‚â‚…FeO₃₉ [2]. Similarly, LLZO (Li₇La₃Zrâ‚‚Oâ‚â‚‚), a leading solid-state battery electrolyte, requires high-temperature synthesis (~1000°C) that volatilizes lithium and promotes impurity formation [2]. In both cases, thermodynamic stability does not translate to straightforward synthesizability, creating a barrier between computational prediction and practical realization.

Quantitative Evidence of the Bottleneck

Recent benchmarking studies have quantified the impact of design space quality on materials discovery success, revealing the critical importance of synthesizability in practical discovery campaigns. The concept of "design space quality" has been formalized through metrics such as the Fraction of Improved Candidates (FIC), which measures the fraction of candidates in a design space that perform better than the best training candidate [5].

Table 1: Relationship Between Design Space Quality and Discovery Success

| Fraction of Improved Candidates (FIC) | Average Iterations to Find Improved Candidate | Likelihood of Discovery Success |

|---|---|---|

| Low (e.g., <0.01) | High variance, many iterations required | Low |

| Medium (e.g., 0.01-0.1) | Moderate number of iterations | Moderate |

| High (e.g., >0.1) | Few iterations required | High |

Sequential learning success has been shown to be highly sensitive to FIC values, with low-FIC design spaces requiring substantially more iterations to find improved candidates [5]. This relationship underscores the importance of focusing computational efforts on design spaces with viable synthetic pathways, rather than merely thermodynamically stable compounds.

Further benchmarking of sequential learning algorithms for experimental materials discovery revealed wildly variable performance, with acceleration factors ranging from "up to a factor of 20 compared to random acquisition in specific scenarios" to "substantial deceleration compared to random acquisition methods" in unfavorable cases [6]. This variability often stems from synthesizability constraints not captured in purely computational evaluations.

Root Causes of the Synthesis Bottleneck

The Data Scarcity Problem

The primary root cause of the synthesis bottleneck is a fundamental data scarcity problem for synthesis recipes compared to materials structures and properties. While extensive databases exist for computed material properties, with initiatives like the Materials Project containing approximately 200,000 entries, no equivalent comprehensive database exists for synthesis protocols [2].

This data disparity stems from both technical and cultural challenges. From a technical perspective, simulating synthesis is "fundamentally more complicated than simulating an atomic structure" as reaction pathways involve numerous factors including "time, temperature, atmosphere, pressure, defects, and grain boundaries" across vast spatiotemporal scales [2]. The computational cost of simulating these complex processes far exceeds current capabilities, as "our best supercomputers today can only simulate 10^8 atoms simultaneously over a few picoseconds" – insufficient for modeling realistic synthesis conditions [2].

Culturally, the materials science publication ecosystem systematically under-reports negative results and methodological variations. As noted by Newfound Materials, "failed synthesis attempts ('negative results') are almost never published" and "the scope of all chemical reactions tested is surprisingly narrow" due to researchers' tendency to stick with established, 'good enough' synthetic routes rather than exploring innovative alternatives [2]. This publication bias creates critical gaps in training data for machine learning models attempting to predict synthesis pathways.

Limitations of Literature-Based Data Mining

Initial efforts to address the synthesis data gap have focused on mining the extensive materials science literature. Notable projects have attempted to extract synthesis recipes from published papers, such as one effort that scraped "32,000 synthesis recipes from the materials science literature" [2]. However, these approaches face significant limitations in both data quality and coverage.

The recently introduced Open Materials Guide (OMG) dataset, comprising 17K expert-verified synthesis recipes, represents a step forward but still reveals the limitations of existing data [7]. Analysis of previous datasets showed that "over 92% of records lacked essential synthesis parameters (e.g., heating temperature, duration, mixing media)" and were narrowly focused on a few common synthesis techniques rather than covering the full spectrum of methods used in real-world materials innovation [7].

Table 2: Synthesis Data Availability Challenges

| Data Challenge | Impact on ML Models | Potential Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Missing failed experiments | Models lack negative training examples | Institutional negative result repositories |

| Incomplete parameter reporting | Critical synthesis factors omitted from models | Standardized reporting protocols |

| Narrow technique focus | Limited generalizability across methods | Diversified data collection |

| Copyright restrictions | Limited data sharing and collaboration | Open-access mandates and repositories |

| Inconsistent terminology | Entity resolution challenges | Unified ontologies and vocabularies |

Furthermore, human bias in chemical experiment planning has been shown to "even lead to less successful outcomes than those of randomly selected experiments" in some cases, suggesting that "centuries of scientific intuition can do more harm than good" when it comes to exploring synthetic possibilities [2]. This bias becomes embedded in literature-mined datasets, limiting the diversity of approaches that machine learning models can learn from.

Emerging Solutions and Methodologies

AI-Driven Synthesis Prediction Frameworks

Novel computational frameworks are emerging to specifically address the synthesis bottleneck. These approaches move beyond traditional property prediction to tackle the unique challenges of synthesis pathway modeling. The AlchemyBench benchmark provides an end-to-end framework for evaluating synthesis prediction models across multiple facets, including raw materials and equipment prediction, synthesis procedure generation, and characterization outcome forecasting [7].

These frameworks employ diverse methodological approaches:

Reaction Network Modeling: Some platforms, like the approach described by Newfound Materials, take "a reaction network-based approach, generating hundreds of thousands of reaction pathways for any inorganic compound of interest" [2]. These networks include both conventional routes starting from common precursors and unconventional pathways beginning with rarely tested intermediate phases, potentially revealing "low-barrier synthesis routes, like finding a shortcut around the mountain rather than going over it" [2].

Large Language Model Applications: The development of the LLM-as-a-Judge framework demonstrates how large language models can be leveraged to automate the evaluation of synthesis predictions, showing "strong statistical agreement with expert assessments" while providing scalability beyond manual expert evaluation [7]. This approach is particularly valuable given the scarcity of domain experts available for manual recipe validation.

Multi-Task Learning: By framing synthesis prediction as multiple interrelated tasks – including precursor selection, condition optimization, and outcome prediction – these models can leverage shared representations across tasks, mitigating data scarcity for any single aspect of the synthesis problem [7].

Integrated Workflow Design

Addressing the synthesis bottleneck requires integrated workflows that connect computational prediction with experimental validation. The traditional sequential process of computation → prediction → synthesis is being replaced by iterative cycles where synthesis outcomes inform model refinement.

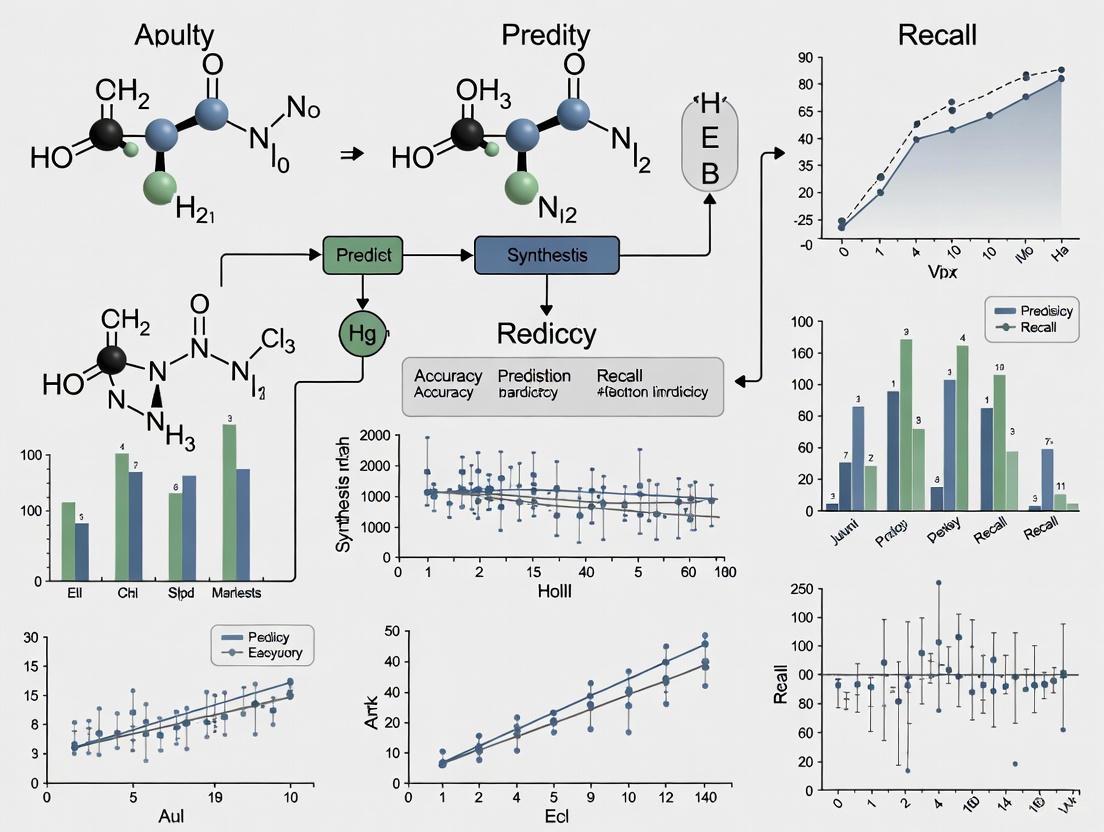

The following diagram illustrates this integrated approach:

This integrated workflow embodies the "closed loop" discovery process described in recent perspectives, where "AI, automation and improvements to deployment technologies can move towards a community-driven, closed loop process" [4]. Within this framework, Bayesian optimization methods enable "dynamic candidate prioritization," allowing researchers to "selectively spend computational budget, and thus use more accurate models on a smaller amount of data" while balancing exploration of new chemical spaces with exploitation of known promising regions [4].

Table 3: Essential Resources for Synthesis-Focused Materials Discovery

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Databases | Materials Project [3], OMG [7] | Provide foundational data for structure-property relationships and synthesis conditions |

| Synthesis Prediction Models | MatterGen [2], AlchemyBench [7] | Generate novel candidate materials and predict viable synthesis pathways |

| Automated Experimentation | Robotic materials synthesis platforms [4] | Enable high-throughput experimental validation and data generation |

| Natural Language Processing | IBM DeepSearch [4], ChemDataExtractor [4] | Extract structured synthesis information from unstructured literature |

| Sequential Learning Frameworks | Bayesian optimization [4], Active learning [5] | Intelligently guide experimental campaigns to maximize information gain |

Experimental Protocols for Synthesis-Focused Discovery

Sequential Learning for Experimental Optimization

Sequential learning (also referred to as active learning) provides a methodological framework for efficiently navigating complex synthesis spaces. The following protocol outlines a standardized approach for sequential learning in materials discovery:

Initialization Phase:

- Define Search Space: Establish the boundaries of the compositional or synthetic parameter space to be explored, typically represented as a 6-dimensional composition vector for multi-element systems [6].

- Collect Initial Data: Assemble existing experimental data or generate initial data points through diverse sampling strategies to ensure representative coverage.

- Train Initial Model: Develop a baseline machine learning model (e.g., Random Forest, Gaussian Process) using available data to establish initial structure-property relationships [6].

Iterative Learning Phase:

- Candidate Prioritization: Use an acquisition function (e.g., expected improvement, upper confidence bound) to identify the most promising candidates for experimental testing based on the current model [4].

- Parallel Experimental Synthesis: Execute synthesis and characterization of prioritized candidates, ideally using automated platforms to increase throughput. For metal oxide systems, this may involve "inkjet printing of elemental precursors" followed by "calcination at 400°C for 10 hours" and subsequent electrochemical characterization [6].

- Model Retraining: Incorporate new experimental results into the training dataset and update the predictive model.

- Convergence Checking: Evaluate whether performance targets have been met or whether additional iterations are likely to yield significant improvements.

This protocol has demonstrated "up to a factor of 20" acceleration compared to random acquisition in specific scenarios, though performance is highly dependent on the quality of the design space and appropriateness of the machine learning model for the specific research goal [6].

Synthesis Route Generation and Evaluation

For generating novel synthesis pathways, the following experimental methodology provides a structured approach:

Data Curation:

- Literature Extraction: Apply natural language processing tools to extract synthesis protocols from scientific literature, using systems like the IBM DeepSearch platform which "leverages state-of-the-art AI models to convert documents from PDF to structured file format JSON" [4].

- Structured Representation: Convert unstructured recipe information into standardized components including target material description, raw materials with quantities, equipment specifications, step-by-step procedures, and characterization methods [7].

- Expert Validation: Engage domain experts to evaluate extracted recipes for "completeness, correctness, and coherence" using standardized rating scales, with calculation of inter-rater reliability to ensure consistency [7].

Pathway Generation:

- Reaction Network Expansion: Enumerate possible synthesis pathways using known precursor combinations and reaction types, considering both conventional and unconventional routes.

- Thermodynamic Modeling: Evaluate predicted reaction outcomes using computational thermodynamics to identify potentially viable pathways.

- Machine-Learned Filtering: Apply trained models to prioritize routes with higher predicted success probabilities based on learned patterns from existing data.

This methodology enables systematic exploration beyond human intuition-driven approaches, potentially revealing synthetic pathways that might otherwise be overlooked.

Future Perspectives and Research Directions

Overcoming the synthesis bottleneck requires advances across multiple fronts, from data infrastructure to algorithmic innovation. Three key research directions emerge as particularly critical:

Comprehensive Data Ecosystems: Future progress depends on developing more comprehensive synthesis data repositories that systematically capture both successful and failed attempts across diverse synthetic methodologies. This will require cultural shifts in how researchers report experiments and technical advances in automated data capture from laboratory instrumentation.

Multi-Scale Modeling Integration: Addressing the synthesis challenge requires integrating models across time and length scales – from quantum mechanical calculations of reaction barriers to mesoscale models of phase evolution – to develop a more complete picture of synthesis pathways. Recent work on machine-learned potentials that "enable access to quantum-chemical-like accuracies at a fraction of the cost" represents an important step in this direction [4].

Autonomous Experimental Platforms: The full potential of AI-guided materials discovery will be realized through tighter integration with autonomous synthesis and characterization platforms. As noted in recent perspectives, "the integration of AI-driven robotic laboratories and high-throughput computing has established a fully automated pipeline for rapid synthesis and experimental validation, drastically reducing the time and cost of material discovery" [8].

The following diagram illustrates the envisioned future of integrated materials discovery:

As these research directions advance, the synthesis bottleneck in computational materials discovery will progressively narrow, ultimately fulfilling the promise of truly accelerated materials design and realization for addressing critical technological challenges.

Natural Language Processing for Extracting Synthesis Recipes from Literature

The discovery and development of new materials play a crucial role in technological advancement, from renewable energy solutions to next-generation electronics. While computational methods have dramatically accelerated the prediction of novel, stable materials, synthesizing these predicted compounds remains a significant bottleneck in the materials discovery pipeline [9] [2]. The challenge lies in the fact that thermodynamic stability does not guarantee synthesizability, and computational predictions typically provide no guidance on practical synthesis parameters such as precursors, temperatures, or reaction times [10].

Fortunately, the scientific literature contains a vast repository of experimental knowledge in the form of published synthesis procedures. Between 2016 and 2019, researchers undertook ambitious efforts to text-mine synthesis recipes from scientific publications, resulting in datasets of 31,782 solid-state synthesis recipes and 35,675 solution-based synthesis recipes [9] [10]. This article provides a comprehensive technical examination of the natural language processing (NLP) methodologies developed to extract these synthesis recipes, the challenges encountered, and the resulting applications within the broader context of machine learning for solid-state synthesis recipe generation.

Natural Language Processing Pipeline for Synthesis Extraction

The process of converting unstructured synthesis descriptions from scientific literature into structured, codified recipes requires a sophisticated NLP pipeline. The overall workflow involves multiple sequential steps, each addressing specific technical challenges [10].

Table 1: Key Stages in the NLP Pipeline for Synthesis Extraction

| Pipeline Stage | Primary Challenge | Technical Approach | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Literature Procurement | Publisher format variability | Secure full-text permissions from major publishers; focus on post-2000 HTML/XML content | Corpus of 4,204,170 papers with 6,218,136 experimental paragraphs |

| Synthesis Paragraph Identification | Locating synthesis descriptions within papers | Probabilistic assignment based on keyword frequency in paragraphs | 188,198 inorganic synthesis paragraphs (53,538 solid-state) |

| Target & Precursor Extraction | Context-dependent material roles | BiLSTM-CRF model with chemical compounds replaced by |

Labeled targets, precursors, and reaction media |

| Synthesis Operations Classification | Synonym variability for similar processes | Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) for topic modeling | Categorized operations (mixing, heating, drying, etc.) with parameters |

| Recipe Compilation & Reaction Balancing | Combining extracted elements into coherent recipes | JSON schema development; reaction balancing with atmospheric gases | 15,144 solid-state recipes with balanced chemical reactions |

Full-Text Literature Procurement and Synthesis Identification

The initial stage involves gathering a comprehensive corpus of materials science literature. Early text-mining efforts secured full-text permissions from major scientific publishers including Springer, Wiley, Elsevier, the Royal Society of Chemistry, and several professional societies [10]. To avoid complications with optical character recognition errors, the pipeline focused exclusively on publications after 2000 that were available in HTML or XML formats.

Identifying which paragraphs within a scientific paper contain synthesis procedures presents a notable challenge, as the location of experimental sections varies across publishers and article types. Researchers addressed this using a probabilistic classification approach based on keyword frequency. Paragraphs containing terminology commonly associated with inorganic materials synthesis ("calcined," "annealed," "sintered") received higher probability scores for being classified as synthesis descriptions [10].

Materials Entity Recognition and Role Classification

Perhaps the most technically challenging aspect of the pipeline involves correctly identifying chemical compounds and determining their specific roles within a synthesis procedure. The same material can serve different functions in different contexts—for instance, TiOâ‚‚ may be a target material in nanoparticle synthesis, but a precursor for ternary oxides like Liâ‚„Tiâ‚…Oâ‚â‚‚ [10].

To address this, researchers implemented a Bi-Directional Long Short-Term Memory network with a Conditional Random Field layer (BiLSTM-CRF). This approach first replaces all chemical compounds with a generic <MAT> tag, then uses contextual sentence clues to classify each tag as a target material, precursor, or other reaction component (atmospheres, solvents, etc.) [10]. For example, in the sentence "a spinel-type cathode material <MAT> was prepared from high-purity precursors <MAT>, <MAT> and <MAT>, at 700 °C for 24 h in <MAT>," the model learns to identify the first <MAT> as the target, the next three as precursors, and the final one as reaction media.

The BiLSTM-CRF model was trained on a manually annotated dataset of 834 solid-state synthesis paragraphs, enabling it to learn the linguistic patterns that distinguish material roles based on their context within synthesis descriptions [10].

Synthesis Operations Extraction Using Topic Modeling

Materials scientists describe similar synthetic operations using varied terminology—"calcined," "fired," "heated," and "baked" all refer to essentially the same thermal treatment process. To systematically identify and categorize these operations, researchers employed Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA), a topic modeling technique that clusters keywords into topics corresponding to specific materials synthesis operations [10].

Through this approach, the pipeline classified sentence tokens into six operation categories: mixing, heating, drying, shaping, quenching, or not an operation. For each operation type, the system extracted relevant parameters (temperatures, times, atmospheres) associated with the operation. The pipeline was initially trained on a manually labeled set of 100 solid-state synthesis paragraphs containing 664 sentences [10].

A Markov chain representation of these experimental operations enabled the reconstruction of synthesis flowcharts from the extracted data, providing a visual representation of the procedural sequence [10].

Recipe Compilation and Reaction Balancing

The final pipeline stage combines all extracted elements into structured JSON recipes with balanced chemical reactions. This involves computationally balancing the identified precursors and target materials, often requiring the inclusion of volatile atmospheric gases (Oâ‚‚, Nâ‚‚, COâ‚‚) to achieve stoichiometric balance [10].

The overall extraction yield of the complete pipeline was approximately 28%, meaning that of the 53,538 solid-state synthesis paragraphs identified, only 15,144 produced balanced chemical reactions [10]. Manual validation of 100 randomly selected paragraphs classified as solid-state synthesis revealed that 30 contained insufficient information for complete recipe extraction, highlighting the challenge of incomplete reporting in experimental sections [10].

NLP Pipeline: The workflow transforms unstructured text into structured synthesis recipes through sequential stages, with decreasing data volume at each step due to extraction challenges [10].

Quantitative Assessment of Extracted Synthesis Data

The text-mining efforts yielded substantial datasets of synthesis recipes, yet comprehensive analysis reveals significant limitations in their utility for machine learning applications. When evaluated against the "4 Vs" of data science—volume, variety, veracity, and velocity—the datasets exhibit critical shortcomings [9].

Table 2: Text-Mined Synthesis Dataset Composition and Limitations

| Dataset Characteristic | Solid-State Synthesis | Solution-Based Synthesis | Limitations and Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Recipes Extracted | 31,782 recipes | 35,675 recipes | Limited volume compared to combinatorial space |

| Precursor Diversity | Limited diversity for common materials | Not quantified | Human bias toward conventional precursors |

| Reaction Temperature Range | Concentrated in common ranges (e.g., 700-900°C) | Not specified | Insufficient exploration of parameter space |

| Extraction Yield | 28% (15,144 from 53,538 paragraphs) | Not specified | Reporting incompleteness affects data quality |

| Failure Documentation | Nearly absent | Nearly absent | Lacks crucial negative results data |

| Temporal Coverage | Post-2000 literature only | Post-2000 literature only | Missing historical synthesis knowledge |

The volume of extracted recipes, while substantial, pales in comparison to the virtually infinite combinatorial space of possible synthesis reactions. For example, testing just binary reactions between 1,000 compounds would require approximately 500,000 experiments [2]. The variety in the datasets is constrained by anthropogenic biases—scientists tend to use familiar precursors and avoid unconventional "wacky" synthesis routes [2]. In the case of barium titanate (BaTiO₃) synthesis, 144 of 164 recipe entries used the same precursors (BaCO₃ + TiO₂), despite this route requiring high temperatures and long heating times and proceeding through intermediates [2].

Veracity concerns emerge from both text-mining technical challenges and reporting practices in scientific literature. The 28% extraction yield indicates significant information loss in the pipeline, while the near-total absence of failed synthesis attempts ("negative results") in literature creates a fundamental skew in the dataset [9] [2]. The velocity at which new synthesis knowledge enters the dataset is limited by both publication timelines and the effort required for text-mining updates [9].

Applications and Limitations in Predictive Synthesis

Machine Learning Applications

The primary motivation behind creating large-scale synthesis recipe datasets has been to train machine learning models for predictive synthesis. The envisioned application follows the success of retrosynthesis prediction in organic chemistry, where deep neural networks have demonstrated remarkable performance when trained on large reaction databases such as SciFinder and Reaxys [10].

In practice, however, machine learning models trained on these text-mined datasets have shown limited utility in guiding the predictive synthesis of novel materials [9]. The models successfully capture how chemists have historically thought about materials synthesis but offer few substantially new insights for synthesizing novel compounds [10]. This limitation stems fundamentally from the dataset characteristics outlined in Table 2—the biases and gaps in the training data constrain the models' predictive capabilities for truly novel synthesis challenges.

Anomalous Recipe Analysis and Knowledge Discovery

Paradoxically, the most valuable scientific insights emerged not from the conventional recipes that dominate the dataset, but from the anomalous recipes that defy conventional synthesis intuition [9]. These unusual synthesis approaches are rare in the literature and thus have minimal influence on regression or classification models, but their manual examination led researchers to new mechanistic hypotheses about how solid-state reactions proceed [9].

This discovery process exemplifies how large historical datasets can yield value through hypothesis generation rather than direct model training. By identifying outliers that contradict established understanding, researchers can formulate new mechanistic theories about materials formation, which can then be validated through targeted experimentation [9]. This approach has led to high-visibility follow-up studies that experimentally validated hypothesized mechanisms gleaned from text-mined literature data [10].

Data Utilization Pathways: Conventional recipes train models that capture historical practice but offer limited novel insights, while analysis of rare anomalous recipes leads to novel hypotheses and experimental validation [9] [10].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Data Annotation for Model Training

The development of effective NLP models for synthesis extraction required carefully designed manual annotation protocols. For the Materials Entity Recognition task, researchers manually annotated targets, precursors, and other reaction media in 834 solid-state synthesis paragraphs to create training data for the BiLSTM-CRF model [10]. This annotation process required materials science expertise to correctly identify material roles based on contextual clues.

For synthesis operations classification, the manual annotation encompassed 100 solid-state synthesis paragraphs containing 664 sentences [10]. Each sentence token was labeled as belonging to one of six categories: mixing, heating, drying, shaping, quenching, or not an operation. This annotated dataset enabled the LDA topic model to learn the vocabulary associations for different synthesis operations.

Integration with Computational Thermodynamics

A significant technical achievement in the recipe compilation stage was the integration of extracted synthesis information with computational thermodynamics data from the Materials Project [10]. By computing the reaction energetics of extracted precursors and targets using DFT-calculated bulk energies, researchers could potentially identify thermodynamic drivers for synthesis reactions.

This integration required developing algorithms to automatically balance chemical reactions, including the addition of volatile atmospheric gases when necessary. The ability to compute reaction energies for text-mined synthesis recipes created opportunities to correlate synthesis conditions with thermodynamic parameters, potentially revealing patterns in how synthesis temperature relates to reaction energetics [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Data Resources for Synthesis Extraction Research

| Resource Name | Type | Function and Application | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Text-Mined Synthesis Dataset | Structured database | 31,782 solid-state synthesis recipes for training ML models | Available via GitHub: CederGroupHub/text-mined-synthesis_public [11] |

| BiLSTM-CRF Model | Neural network architecture | Materials Entity Recognition and role classification in synthesis paragraphs | Custom implementation described in original publications [10] |

| Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) | Topic modeling algorithm | Clustering synonymous synthesis operations into standardized categories | Standard NLP libraries (e.g., Gensim) with custom modifications [10] |

| Materials Project API | Computational materials database | Provides thermodynamic data for reaction balancing and energy calculations | Public REST API available at materialsproject.org [10] |

| Solid-State Synthesis Paragraphs | Labeled corpus | Training and evaluation data for NLP model development | Manually annotated set of 834 synthesis paragraphs [10] |

| 1-Methyl-2-pentyl-4(1H)-quinolinone | 1-Methyl-2-pentyl-4(1H)-quinolinone | High Purity | 1-Methyl-2-pentyl-4(1H)-quinolinone for research. A key quinolinone scaffold for biochemical studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| 10-Aminodecanoic acid | 10-Aminodecanoic Acid|CAS 13108-19-5|Research Chemical | Bench Chemicals |

Future Directions and Emerging Approaches

Recent advances in artificial intelligence, particularly the emergence of large language models (LLMs), offer promising avenues for addressing limitations in earlier text-mining approaches. Modern LLMs demonstrate enhanced capabilities in understanding scientific context and processing complex technical language, potentially overcoming some challenges in materials entity recognition and role classification [12].

The development of autonomous laboratories represents another frontier where text-mined synthesis knowledge can be operationalized. Systems such as A-Lab integrate NLP-based recipe generation with robotic synthesis and characterization, creating closed-loop cycles where text-mined knowledge informs actual experimental execution [12]. In one demonstration, A-Lab successfully synthesized 41 of 58 computationally predicted inorganic materials over 17 days of continuous operation by leveraging natural language models trained on literature data for synthesis planning [12].

LLM-based agent systems like Coscientist and ChemCrow further expand these capabilities by enabling autonomous design, planning, and execution of chemical experiments [12]. These systems augment LLMs with tool-using capabilities that allow them to search literature, plan synthetic routes, and control laboratory instrumentation. However, significant challenges remain, including the tendency of LLMs to generate plausible but incorrect chemical information and their limited ability to indicate uncertainty levels [12].

Future progress will likely require the development of standardized experimental data formats to improve data quality and interoperability, along with foundation models specifically trained across diverse materials and reaction types [12]. Transfer learning and meta-learning approaches may help adapt models to new synthesis domains with limited data, while standardized hardware interfaces could enhance the modularity and generalizability of autonomous synthesis platforms [12].

Natural language processing technologies have enabled the extraction of structured synthesis recipes from unstructured scientific literature at unprecedented scales, yielding datasets of tens of thousands of solid-state and solution-based synthesis procedures. The technical pipeline for this extraction involves sophisticated NLP approaches including BiLSTM-CRF networks for materials entity recognition and latent Dirichlet allocation for synthesis operations classification.

While these text-mined datasets have demonstrated limited utility for training machine learning models that can reliably predict synthesis routes for novel materials, they have provided significant value through anomaly detection and hypothesis generation. The analysis of unusual synthesis recipes that defy conventional wisdom has led to new mechanistic insights that were subsequently validated experimentally.

As NLP technologies continue to advance, particularly with the emergence of large language models, the potential for extracting and utilizing synthesis knowledge from literature continues to expand. When integrated with autonomous laboratory systems, these text-mining approaches contribute to an emerging infrastructure for data-driven materials synthesis that may ultimately overcome the critical synthesis bottleneck in computational materials discovery.

The integration of machine learning (ML) into solid-state synthesis represents a paradigm shift in materials discovery. While computational models can generate millions of theoretically promising crystal structures, a significant gap remains between in silico predictions and their realization in the laboratory [13]. This gap is dominated by three core technical challenges: accurately predicting which theoretically stable structures are synthesizable, identifying suitable chemical precursors for these target materials, and classifying the appropriate synthesis actions or methods required. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to the advanced computational frameworks, particularly large language models (LLMs), that are overcoming these hurdles, thereby accelerating the development of automated, data-driven synthesis recipe generation.

Technical Hurdle 1: Predicting Synthesizable Crystal Structures

The Synthesizability Prediction Challenge

Conventional approaches to screening synthesizable materials often rely on thermodynamic stability metrics, such as energy above the convex hull calculated via density functional theory (DFT). However, these methods exhibit limited accuracy, as many structures with favorable formation energies remain unsynthesized, while various metastable structures are successfully synthesized [13]. This discrepancy highlights the complex kinetic and pathway-dependent nature of solid-state synthesis, which traditional metrics fail to capture.

CSLLM: A Large Language Model Framework

The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Models (CSLLM) framework addresses this challenge by leveraging specialized LLMs fine-tuned on comprehensive materials data [13]. The framework decomposes the synthesis prediction problem into three distinct tasks, each handled by a dedicated model:

- Synthesizability LLM: Predicts whether an arbitrary 3D crystal structure is synthesizable.

- Method LLM: Classifies the probable synthetic pathway (e.g., solid-state or solution-based).

- Precursor LLM: Identifies suitable chemical precursors for the target material.

Dataset Construction and Model Training

The development of a robust synthesizability prediction model requires a balanced and comprehensive dataset of both synthesizable and non-synthesizable crystal structures.

- Positive Data: 70,120 synthesizable crystal structures were curated from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD), containing no more than 40 atoms and seven different elements, with disordered structures excluded [13].

- Negative Data: 80,000 non-synthesizable structures were identified by applying a pre-trained Positive-Unlabeled (PU) learning model to a pool of 1,401,562 theoretical structures from various computational databases. Structures with a CLscore below 0.1 were selected as negative examples [13].

To enable LLM processing, a concise text representation termed "material string" was developed. This format efficiently encodes essential crystal information—space group, lattice parameters, and atomic species with their Wyckoff positions—making it analogous to SMILES notation for molecules [13]. The LLMs were then fine-tuned on this dataset, achieving state-of-the-art performance as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Synthesizability Prediction Methods

| Method | Accuracy | Key Metric |

|---|---|---|

| CSLLM (Synthesizability LLM) [13] | 98.6% | Classification Accuracy |

| Thermodynamic Stability (Energy above hull ≥0.1 eV/atom) [13] | 74.1% | Formation Energy |

| Kinetic Stability (Lowest phonon frequency ≥ -0.1 THz) [13] | 82.2% | Phonon Frequency |

| Teacher-Student Dual Neural Network [13] | 92.9% | Classification Accuracy |

Diagram 1: CSLLM framework for synthesis prediction.

Technical Hurdle 2: Precursor Identification and Action Classification

Predicting Synthesis Pathways and Precursors

Once a target material is deemed synthesizable, the subsequent challenges are identifying viable chemical precursors and classifying the correct synthesis method. The CSLLM framework's Method LLM and Precursor LLM are specifically designed for these tasks [13]. The Method LLM classifies the most likely synthesis technique (e.g., solid-state vs. solution-based) with high accuracy. The Precursor LLM identifies specific precursor compounds, a task complicated by the need to consider chemical compatibility, reaction thermodynamics, and experimental feasibility.

The AlchemyBench Benchmark and LLM-as-a-Judge

Concurrently, the development of the Open Materials Guide (OMG) dataset and the AlchemyBench benchmark provides a robust foundation for evaluating model performance on these tasks [7]. The OMG dataset comprises 17,667 high-quality, expert-verified synthesis recipes extracted from open-access literature, covering over ten distinct synthesis techniques.

Table 2: Key Tasks in the AlchemyBench Benchmark

| Task Name | Input | Output | Evaluation Goal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raw Materials Inference | Target material, synthesis method | Precursor compounds & quantities | Identify necessary chemical precursors and their amounts. |

| Equipment Recommendation | Synthesis procedure | Required apparatus | Predict tools and equipment needed for the reaction. |

| Procedure Generation | Target material, precursors | Step-by-step instructions | Generate a sequence of actionable synthesis steps. |

| Characterization Forecasting | Target material, synthesis method | Recommended characterization techniques | Propose methods to verify the resulting material's properties. |

To enable scalable and cost-effective evaluation of model outputs for these tasks, an LLM-as-a-Judge framework was developed. This approach uses a powerful LLM to automatically assess the quality of generated synthesis recipes, demonstrating strong statistical agreement with human expert assessments [7]. This framework is vital for the rapid iteration and validation of new models in this domain.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

End-to-End Synthesis Prediction Protocol

The following detailed protocol, illustrated in Diagram 2, outlines the steps for using the CSLLM framework to predict synthesizability and precursors for a theoretical crystal structure.

- Input Preparation: Convert the candidate crystal structure into the "material string" text representation, which includes space group, lattice parameters (a, b, c, α, β, γ), and a list of atomic species with their Wyckoff positions [13].

- Synthesizability Assessment: Input the material string into the Synthesizability LLM. The model returns a binary classification (synthesizable/non-synthesizable) and a confidence score. A confidence threshold of >95% is recommended for high-reliability screening [13].

- Method and Precursor Prediction: For structures classified as synthesizable, pass the material string sequentially to the Method LLM and the Precursor LLM.

- The Method LLM outputs a probability distribution over possible synthesis methods (e.g., solid-state, hydrothermal).

- The Precursor LLM outputs a ranked list of suggested precursor compounds, typically focusing on common binary and ternary compounds for solid-state reactions [13].

- Validation and Analysis: Cross-reference the suggested precursors with phase diagram data to check for known reactive intermediates. Calculate the theoretical reaction energy using DFT, if possible, to assess thermodynamic favorability [13].

- Recipe Generation: Combine the outputs into a structured synthesis recipe, specifying the target material, recommended method, precursors, and any preliminary conditions.

Diagram 2: End-to-end synthesis prediction workflow.

Protocol for Benchmarking Model Performance

To rigorously evaluate a new model for synthesis prediction, such as a custom LLM, against the state of the art, the following benchmarking protocol using AlchemyBench is recommended [7]:

- Dataset Partitioning: Use the OMG dataset, partitioning it into training, validation, and test sets (e.g., 80/10/10 split) while ensuring no data leakage between splits.

- Task-Specific Fine-Tuning: Fine-tune the candidate model on the training set for the specific tasks of interest: raw materials inference, equipment recommendation, procedure generation, and characterization forecasting.

- LLM-as-a-Judge Evaluation: On the held-out test set, use the established LLM-as-a-Judge framework to evaluate the model's outputs. This involves:

- Prompting the judge LLM with the model's prediction and the ground-truth expert recipe.

- The judge LLM scores the prediction on criteria like completeness, correctness, and coherence using a defined Likert scale [7].

- Expert Validation: To validate the automated judge, a subset of the model's predictions (e.g., 50-100) should be manually assessed by domain experts. Calculate the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) to measure agreement between the LLM judge and human experts [7].

- Performance Comparison: Compare the model's scores against the benchmark performances published for CSLLM and other reference models on identical tasks and metrics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

The computational experiments and frameworks described in this guide rely on a suite of data, software, and model resources. The following table details these essential components.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Specifications / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ICSD (Inorganic Crystal Structure Database) [13] | Source of synthesizable (positive) crystal structures for model training. | Contains experimentally validated structures. Filter for ordered structures with ≤40 atoms. |

| OMG (Open Materials Guide) Dataset [7] | A benchmark dataset of 17K+ expert-verified synthesis recipes for training and evaluation. | Covers >10 synthesis methods. Free from copyright restrictions for research use. |

| Material String Representation [13] | A concise text format for representing crystal structures to enable LLM processing. | Encodes space group, lattice parameters, and atomic Wyckoff positions. |

| Pre-trained PU Learning Model [13] | Used to generate negative (non-synthesizable) training examples from theoretical databases. | Outputs a CLscore; scores <0.1 indicate high non-synthesizability confidence. |

| CSLLM Framework [13] | A suite of three fine-tuned LLMs for end-to-end synthesis and precursor prediction. | Provides a user-friendly interface for predicting synthesizability from CIF files. |

| AlchemyBench Benchmark [7] | An end-to-end evaluation framework for synthesis prediction models. | Includes the LLM-as-a-Judge framework for automated, expert-aligned assessment. |

| (2-Hydroxyethoxy)acetic acid | (2-Hydroxyethoxy)acetic acid, CAS:13382-47-3, MF:C4H8O4, MW:120.10 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3-Hydroxypentadecanoic acid | 3-Hydroxypentadecanoic acid, CAS:32602-70-3, MF:C15H30O3, MW:258.40 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The application of machine learning (ML) to predict solid-state synthesis recipes represents a paradigm shift in materials discovery. However, the effectiveness of these models is intrinsically tied to the quality of the training data, which is predominantly sourced from published literature via text-mining. This technical guide critically examines the journey of text-mined data through the lens of the "4 Vs" framework—Volume, Velocity, Variety, and Veracity—within the context of solid-state synthesis research. We analyze the specific technical challenges at each stage of the data lifecycle, from procurement to model training, and present structured quantitative data on the limitations of existing datasets. Furthermore, the guide details emerging methodologies, including LLM-driven data extraction and the LLM-as-a-Judge evaluation framework, which aim to surmount these challenges. The insights provided herein are intended to equip researchers and scientists with a rigorous understanding of the data landscape, thereby enabling the development of more robust and reliable ML models for predictive synthesis.

The vision of computationally accelerated materials discovery is contingent upon solving the predictive synthesis problem; that is, moving beyond identifying what to make to determining how to make it [10]. High-throughput computational searches and convex-hull stability analyses can pinpoint promising novel materials, but they offer no guidance on precursor selection, reaction temperatures, or synthesis pathways [10]. Text-mining the vast corpus of published solid-state synthesis recipes has emerged as a promising strategy to build the knowledge base needed to train ML models for this task.

However, historical efforts to create such databases have followed a "hype cycle," often leading to a "valley of disillusionment" when the derived models fail to generalize for novel materials [10]. This failure can frequently be traced to fundamental shortcomings in the underlying datasets, which can be systematically diagnosed using the "4 Vs" of data science. This guide provides an in-depth analysis of these challenges, framed within the critical domain of solid-state synthesis recipe generation, and outlines the experimental protocols and modern tools being developed to address them.

The "4 Vs" Framework: A Critical Analysis for Text-Mined Synthesis Data

The "4 Vs" framework provides a structured lens to evaluate the suitability of a dataset for machine learning. The following sections break down each "V" with specific, quantifiable challenges encountered in text-mining solid-state synthesis literature.

Volume: The Challenge of Data Scarcity and Extraction Yield

In big data, Volume typically refers to the colossal scales of data available, often measured in zettabytes [14]. However, in the niche domain of solid-state synthesis, the challenge of volume is not one of abundance but of accessible, high-quality, and extractable data.

Large-scale text-mining initiatives have procured millions of scientific papers, but the final yield of usable synthesis recipes is surprisingly low. One effort scanned 4.2 million papers, identifying 535,38 paragraphs related to solid-state synthesis. After processing, only 15,144—a mere 28% extraction yield—resulted in a balanced chemical reaction [10]. This attrition is due to technical hurdles in parsing older PDFs, identifying relevant paragraphs, and, most critically, extracting balanced reactions from unstructured text.

The volume of data is further limited by anthropogenic biases; the scientific literature reflects a narrow subset of all possible chemical spaces that chemists have chosen to explore, leading to a data landscape with significant gaps [10]. While a dataset of thousands of recipes may seem substantial, its utility for training robust ML models is constrained by this lack of comprehensive coverage.

Table 1: Attrition in Text-Mining Volume from a Large-Scale Study

| Data Processing Stage | Count | Attrition Rate | Primary Reason for Attrition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Papers Procured | 4,204,170 | - | - |

| Paragraphs in Experimental Sections | 6,218,136 | - | - |

| Inorganic Synthesis Paragraphs | 188,198 | ~97% | Paragraph classification |

| Solid-State Synthesis Paragraphs | 53,538 | ~72% | Specific synthesis type classification |

| Paragraphs with Balanced Chemical Reactions | 15,144 | ~72% | Extraction errors, inability to balance reactions |

Variety: Navigating Diverse Data Formats and Content

Variety encompasses the different types and formats of data, which range from structured databases to unstructured text, images, and videos [15] [14]. In synthesis text-mining, variety manifests in two primary dimensions: data format and synthesis content.

- Format Variety: Recipes are embedded in unstructured text, requiring Natural Language Processing (NLP) to convert them into a structured format (e.g., JSON) suitable for ML. This involves handling a plethora of challenges, including synonyms (e.g., "calcined," "fired," "heated"), material representations (e.g.,

Pb(Zr0.5Ti0.5)O3,PZT), and the intermingling of procedural steps with ancillary information [10]. - Content Variety: The domain encompasses a wide range of synthesis techniques (solid-state, sol-gel, hydrothermal, chemical vapor deposition, etc.). Early datasets were often narrowly focused on one or two methods, limiting their utility for holistic prediction [7]. Furthermore, within a single recipe, the variety of information that must be extracted is vast, including target materials, precursors, equipment, step-by-step procedures, and characterization results.

This high variety necessitates sophisticated, multi-stage NLP pipelines. The inability to perfectly parse this diversity results in a loss of information and introduces noise, ultimately reducing the variety present in the final, structured dataset.

Table 2: Types of Variety in Synthesis Data and Associated NLP Challenges

| Category of Variety | Examples | NLP/Text-Mining Challenge |

|---|---|---|

| Data Format | Unstructured text, HTML/XML, scanned PDFs | PDF parsing, layout understanding, text normalization |

| Material Representation | LiCoO2, PZT, A_xB_1-xC_2-δ |

Entity recognition, handling abbreviations, parsing solid-solutions |

| Synthesis Operations | "calcined," "sintered," "ground," "fired" | Synonym clustering (e.g., via Latent Dirichlet Allocation), parameter linking |

| Synthesis Techniques | Solid-state, hydrothermal, CVD, sol-gel | Broad coverage in dataset construction, technique-specific parsing rules |

Veracity: The Critical Issue of Data Trustworthiness

Veracity refers to the quality, accuracy, and trustworthiness of the data [15] [16]. For text-mined synthesis data, veracity is arguably the most critical and challenging "V." Poor data veracity can lead to ML models that learn incorrect relationships, ultimately producing unreliable and misleading predictions.

The sources of low veracity are multifold:

- Text-Mining Errors: Early datasets were plagued by extraction inaccuracies. A critical analysis found that over 92% of records in one dataset lacked essential synthesis parameters like heating temperature or duration [7]. Common errors include missing reagents, incorrect reaction temperatures, and misordered procedural steps.

- Reporting Ambiguity: Scientific papers often omit "obvious" steps or precise details, relying on expert knowledge that is not captured by text-mining algorithms.

- Data Contamination: The original literature may contain unintentional errors or irreproducible results, which are then propagated into the mined dataset.

The consequences are significant. As noted in a retrospective analysis, "if the underlying data isn't complete or trustworthy, the insights derived from it aren't very useful" [16]. Ensuring veracity requires a combination of improved NLP techniques and rigorous, expert-led validation.

Velocity: The Dynamics of Data Generation and Relevance

Velocity describes the speed at which data is generated and processed [15] [14]. For synthesis data, velocity has two key aspects: data in motion and data relevance over time.

- Data in Motion: The rate at which new synthesis recipes are published is high. A system must be able to ingest and process this continuous stream of new information to keep a knowledge base current.

- Data Relevance: The value of a data point can decay over time, a concept known as "recency" [16]. In fast-moving sub-fields, a synthesis recipe from a decade ago may be obsolete due to technological advances. Furthermore, infrastructure changes (tech refreshes, decommissioning of equipment) can make older performance data less relevant [16].

While the public literature does not update in milliseconds like a social media feed, the slow velocity of curating high-quality, text-mined datasets means they often lag behind the current state of synthetic knowledge, limiting their ability to guide cutting-edge research.

Experimental Protocols: From Text to Structured Data

This section details the methodologies used to construct text-mined synthesis databases, highlighting both traditional and modern approaches.

Traditional Text-Mining and NLP Pipeline

The foundational work in this field involved multi-step NLP pipelines, as exemplified by the efforts of Huo et al. and Kononova et al. [10]. The workflow is complex and involves several discrete stages, as visualized below.

Detailed Methodology:

- Full-Text Literature Procurement: Securing permissions and downloading full-text papers from major publishers (e.g., Springer, Wiley, Elsevier). A key limitation was the exclusion of older, scanned PDFs which are difficult to parse [10].

- Identify Synthesis Paragraphs: Using probabilistic models to scan manuscripts and identify paragraphs that contain synthesis procedures based on keyword frequency (e.g., "annealed," "sintered") [10].

- Extract Targets and Precursors: A critical and challenging step. Researchers replaced all chemical compounds with a

<MAT>tag and used a Bi-directional Long Short-Term Memory neural network with a Conditional Random Field layer (BiLSTM-CRF) to label each tag as a target, precursor, or other based on sentence context. This model was trained on 834 manually annotated solid-state synthesis paragraphs [10]. - Construct Synthesis Operations: Using Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) to cluster synonyms into topics representing core synthesis operations (mixing, heating, drying, etc.). This allowed for the extraction of relevant parameters (time, temperature, atmosphere) associated with each operation [10].

- Compile Synthesis Recipes and Reactions: All extracted information was combined into a JSON database. A final, crucial step was attempting to balance the chemical reaction for the identified precursors and target, often requiring the inclusion of volatile gases, with DFT-calculated energies used to validate feasibility [10].

Modern LLM-Driven Data Extraction

More recent efforts leverage Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-4 to overcome the limitations of traditional pipelines. The methodology for the Open Materials Guide (OMG) dataset is illustrative [7].

Detailed Methodology:

- Data Retrieval: Using the Semantic Scholar API with 60 domain-specific search terms to retrieve ~28,685 open-access articles from a pool of 400,000 results.

- PDF to Structured Text: Converting PDFs into structured Markdown using tools like PyMuPDFLLM.

- LLM-Powered Annotation: Employing a multi-stage LLM (e.g., GPT-4o) process to:

- Categorize articles based on the presence of synthesis protocols.

- Segment confirmed synthesis text into five key components:

- X: A summary of the target material, synthesis method, and application.

- YM: Raw materials, including quantitative details.

- YE: Equipment specifications.

- YP: Step-by-step procedural instructions.

- YC: Characterization methods and results.

- Quality Verification: A panel of domain experts manually reviews a sample of the extracted recipes against criteria of Completeness, Correctness, and Coherence using a 5-point Likert scale. Statistical measures like the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) are used to gauge inter-rater reliability [7].

The LLM-as-a-Judge Evaluation Framework

To scale evaluation, researchers have proposed an "LLM-as-a-Judge" framework. This involves using a powerful LLM to automatically assess the quality of synthesis predictions generated by other models. The process involves creating detailed evaluation criteria and prompts that guide the judge-LLM to score outputs. Studies have demonstrated "strong statistical agreement between LLM-based assessments and expert judgments," offering a path toward scalable and cost-effective benchmarking of synthesis prediction models [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Solutions

This section catalogs key resources, from datasets to software, that are essential for research in this field.

Table 3: Essential Resources for Text-Mining and ML in Solid-State Synthesis

| Resource Name | Type | Function & Description |

|---|---|---|

| Open Materials Guide (OMG) | Dataset | A curated dataset of ~17K expert-verified synthesis recipes from open-access literature, covering 10+ synthesis techniques. Serves as a high-quality benchmark [7]. |

| AlchemyBench | Benchmark | An end-to-end evaluation framework for synthesis prediction tasks, including raw material/equipment prediction and procedure generation [7]. |

| LLM-as-a-Judge | Framework | A methodology using Large Language Models (e.g., GPT-4) to automatically and scalably evaluate synthesized recipes, reducing reliance on costly expert reviews [7]. |

| BiLSTM-CRF Model | Algorithm | A neural network architecture used for named entity recognition to identify and classify targets and precursors in text [10]. |

| Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) | Algorithm | A topic modeling technique used to cluster synonyms and identify synthesis operations (e.g., heating, mixing) within procedural text [10]. |

| PyMuPDFLLM | Software Tool | A library for converting PDF documents into structured Markdown text, which is crucial for processing scientific literature [7]. |

| 14-Deoxy-17-hydroxyandrographolide | 14-Deoxy-17-hydroxyandrographolide, MF:C20H32O5, MW:352.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ethyl 2-oxocyclohexanecarboxylate | Ethyl 2-oxocyclohexanecarboxylate, CAS:1655-07-8, MF:C9H14O3, MW:170.21 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The path to fully automated materials discovery is paved with data. This guide has delineated the significant hurdles that the "4 Vs" pose for text-mined solid-state synthesis data: the surprisingly limited Volume of high-quality extracts, the daunting Variety of formats and content, the critical Veracity problems that undermine model trust, and the slow Velocity of dataset curation. While traditional NLP pipelines have laid the groundwork, they often result in datasets that are insufficient for training robust predictive models. The future of the field lies in the adoption of modern approaches, including LLM-driven data extraction to improve accuracy and coverage, and the LLM-as-a-Judge framework to enable scalable evaluation. By consciously addressing the "4 Vs" challenge with these advanced tools, the research community can build the high-fidelity data foundation necessary to realize the promise of machine-learning-driven synthesis.

In the domain of solid-state materials synthesis, the conventional research and development pipeline has historically prioritized the analysis of successful experiments. However, a paradigm shift is underway, driven by the integration of machine learning and autonomous laboratories, which recognizes that failed synthesis attempts and anomalous outcomes constitute a rich, untapped source of mechanistic insight. The systematic analysis of these "outlier recipes"—procedures that fail to yield the target material or produce unexpected intermediates—can illuminate the complex reaction pathways and kinetic traps that govern solid-state transformations [17] [18]. This whitepaper delineates how the methodical investigation of anomalies, powered by advanced computational frameworks and high-throughput experimentation, is advancing a new era of data-driven synthesis science where every experimental outcome, success or failure, contributes to the refinement of mechanistic hypotheses and the acceleration of materials discovery.

The Scientific and Practical Value of Synthesis Anomalies

The Data Deficit in Conventional Synthesis Science

Traditional materials science has been hampered by a pervasive publication bias, wherein only positive results—successful syntheses of target materials—are routinely reported and documented. This creates a significant knowledge gap, as the data from failed experiments, which often contain critical information about reaction barriers and phase stability, are lost to the broader research community [17]. This "data deficit" fundamentally limits the development of predictive models for solid-state synthesis. Without comprehensive datasets that include both positive and negative outcomes, machine learning algorithms lack the necessary information to understand the full parameter space of synthesis, including the conditions and precursor choices that lead to failure.

Anomalies as Probes of Mechanistic Pathways

Synthesis anomalies serve as powerful natural experiments that probe the underlying free energy landscape and kinetic pathways of solid-state reactions. An unexpected phase forming instead of a target, or a reaction that fails to proceed despite a favorable thermodynamic driving force, provides direct evidence of metastable intermediates and kinetic competition [17] [18]. For instance, the formation of a highly stable intermediate phase can consume the available driving force, preventing the nucleation of the target material [17]. Analyzing the conditions that lead to such outcomes allows researchers to formulate and test specific hypotheses about which pairwise reactions are most favorable, how nucleation barriers vary with precursor chemistry, and which kinetic traps are most prevalent in a given chemical space.

Table 1: Categories of Synthesis Anomalies and Their Mechanistic Implications

| Anomaly Category | Description | Potential Mechanistic Insight |

|---|---|---|

| Phase Competition | Formation of unexpected, stable byproduct phases instead of the target. | Reveals low-energy decomposition pathways or kinetic preferences for certain crystal structures [18]. |

| Inert Intermediates | Reaction pathway stalls at a persistent intermediate phase. | Indicates a high kinetic barrier for the conversion of the intermediate to the target, or a particularly stable intermediate configuration [17]. |

| Sluggish Kinetics | Reaction does not proceed to completion within expected timeframes. | Suggests a small thermodynamic driving force (<50 meV per atom) or a high nucleation barrier for the target phase [18]. |

| Precursor Volatility | Loss of volatile precursor components during heating. | Highlights incompatibility between precursor properties and thermal profiles, necessitating alternative precursor choices or modified heating schedules [18]. |

| Amorphization | Formation of amorphous domains instead of crystalline products. | Points to low atomic mobility or complex reaction pathways that frustrate crystalline nucleation [18]. |

Computational Frameworks for Anomaly-Driven Discovery

The ARROWS3 Algorithm: Active Learning from Failure

The ARROWS3 (Autonomous Reaction Route Optimization with Solid-State Synthesis) algorithm exemplifies the principled integration of anomaly analysis into synthesis planning [17]. Its logical workflow is designed to actively learn from failed experiments and dynamically update its precursor recommendations. The algorithm begins with an initial ranking of precursor sets based on the computed thermodynamic driving force (ΔG) to form the target material. These top-ranked precursors are then tested experimentally across a range of temperatures. When a synthesis fails, X-ray diffraction (XRD) data is used to identify the intermediate phases that formed instead of the target.

ARROWS3's core innovation lies in its subsequent step: it analyzes these intermediates to determine which specific pairwise reactions occurred and calculates the remaining driving force (ΔG′) to form the target from these intermediates. Precursor sets that lead to intermediates with a small ΔG′ are deprioritized, as they represent kinetic traps. The algorithm then proposes new precursor combinations predicted to avoid these traps and maintain a large driving force through to the target-forming step. This creates a closed-loop learning cycle where anomalies directly inform and improve the next round of experimentation.

Diagram 1: ARROWS3 active learning from anomalies.

Performance Validation: Case Study on YBCO Synthesis

The efficacy of the ARROWS3 framework was rigorously validated on a benchmark dataset created for the synthesis of YBa₂Cu₃O₆.₅ (YBCO) [17]. This comprehensive dataset was specifically constructed to include both positive and negative results, comprising 188 individual synthesis experiments using 47 different precursor combinations across a temperature range of 600–900 °C. Within this dataset, only 10 experiments (5.3%) yielded pure YBCO without detectable impurities, while a further 83 experiments (44.1%) produced YBCO alongside byproducts. The remaining 95 experiments (50.5%) failed entirely to produce the target, representing a rich set of anomalies for analysis.

When deployed on this benchmark, ARROWS3 successfully identified all effective precursor sets for YBCO while requiring fewer experimental iterations compared to black-box optimization algorithms like Bayesian optimization or genetic algorithms [17]. This performance highlights a critical principle: by explicitly learning from the mechanistic clues in failed syntheses, algorithms can navigate the complex synthesis landscape more efficiently than methods that treat the process as an opaque optimization problem.

Table 2: Quantitative Outcomes from the YBCO Synthesis Benchmark Dataset [17]

| Experiment Outcome | Number of Experiments | Percentage of Total | Key Insight for Optimization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pure YBCO | 10 | 5.3% | Validated successful precursor sets and conditions. |

| Partial YBCO Yield | 83 | 44.1% | Identified competing phases and kinetic traps. |

| Failed Synthesis | 95 | 50.5% | Revealed inert intermediates and unfavorable reaction pathways. |

| Total Experiments | 188 | 100% | Provided a complete dataset for training and validation. |

Experimental Protocols for Anomaly Detection and Analysis

High-Throughput Anomaly Generation and Characterization

The A-Lab, an autonomous materials discovery platform, provides a robust protocol for the large-scale generation and analysis of synthesis data, including anomalies [18]. Its integrated workflow combines robotics with machine learning to execute and learn from hundreds of synthesis experiments.

Protocol: Autonomous Synthesis and Analysis Cycle

- Target Selection & Recipe Proposal: The cycle begins with a target material predicted to be stable by ab initio data (e.g., from the Materials Project). Up to five initial synthesis recipes are proposed by a natural-language processing model trained on historical literature, which identifies analogies to known materials [18].

- Robotic Execution:

- Sample Preparation: Precursor powders are dispensed and mixed by a robotic arm in an alumina crucible.

- Heating: The crucible is transferred to a box furnace and heated according to the proposed temperature profile.

- Characterization: After cooling, the sample is robotically ground into a fine powder, and its X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern is measured.

- Phase Identification & Anomaly Detection: The XRD pattern is analyzed by machine learning models to identify the present phases and their weight fractions. This step is critical for detecting anomalies—a result is flagged as anomalous if the target phase is absent or is not the majority phase.

- Active Learning & Iteration (ARROWS3): If the initial recipe fails (anomaly detected), the ARROWS3 algorithm is invoked. It uses the identified impurity phases to map the reaction pathway and propose a new, optimized recipe that avoids the observed kinetic traps [18]. This loop continues until the target is synthesized or all candidate recipes are exhausted.

Diagram 2: A-Lab autonomous synthesis and anomaly analysis.

Advanced Characterization for Mechanistic Insight

Beyond standard XRD, advanced characterization techniques provide deeper insights into the microstructural anomalies that occur during synthesis.

- In-situ High-Energy XRD: This protocol involves tracking the structural evolution of a reaction in real-time as it is heated. The high flux and penetration of synchrotron X-rays allow for the detection of transient intermediates and the quantification of reaction kinetics [19].

- Microstrain Analysis: As demonstrated in the solid-state synthesis of LiCoOâ‚‚, ex-situ high-resolution XRD can be used to quantify residual microstrains in the crystal lattice [19]. This microstrain often originates at heterogeneous phase boundaries during incomplete reactions and serves as a highly sensitive indicator of synthesis "completeness" and the presence of subtle anomalies not visible in standard phase analysis. Higher microstrain correlates with more defects and poorer electrochemical performance, linking an anomalous synthetic characteristic directly to a functional property [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The experimental and computational research outlined in this whitepaper relies on a suite of key reagents, instruments, and algorithms. The following table details these essential components and their functions in the context of anomaly-driven synthesis research.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Anomaly-Driven Synthesis Research

| Tool Name / Category | Specific Examples / Types | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Powders | Y₂O₃, BaCO₃, CuO; Li₂CO₃, Co₃O₄; various carbonates, oxides, and phosphates. | Fundamental starting materials for solid-state reactions. Different precursor choices directly influence reaction pathways and the propensity to form anomalous intermediates [17] [18]. |

| Computational Databases | Materials Project, Google DeepMind phase data. | Sources of ab initio thermodynamic data (e.g., formation energies, decomposition energies) used to calculate initial reaction driving forces (ΔG) and stability predictions for target materials [18]. |

| Autonomous Laboratory Hardware | Robotic arms (e.g., Franka Emika Panda), automated furnaces, powder dispensing and grinding stations. | Robotics enable high-throughput, reproducible execution of synthesis and characterization protocols, generating the large, consistent datasets required for anomaly analysis [18]. |

| Characterization Instruments | X-ray Diffractometer (XRD), in-situ synchrotron HE-XRD, benchtop NMR. | Used for phase identification and quantification. Critical for detecting and diagnosing anomalies by identifying unexpected crystalline phases or quantifying structural defects like microstrain [18] [19]. |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | ARROWS3, NLP-based recipe proposers, XRD phase analysis models (e.g., XRD-AutoAnalyzer). | Core intelligence for proposing initial experiments, analyzing outcomes, identifying anomalies, and formulating new mechanistic hypotheses for subsequent testing [17] [18]. |

| 1-Tert-butyl-3-ethoxybenzene | 1-Tert-butyl-3-ethoxybenzene, MF:C12H18O, MW:178.27 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Methyl 3-hydroxyoctadecanoate | Methyl 3-Hydroxyoctadecanoate|Research Compound | Explore Methyl 3-hydroxyoctadecanoate for antibiofilm research. This compound inhibitsS. epidermidisbiofilm formation. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |