Literature-Inspired Recipes vs. Active Learning Optimization: A Data-Driven Comparison for Accelerated Scientific Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between traditional literature-inspired methods and modern active learning (AL) optimization for discovery and development processes, with a focus on applications for researchers and drug...

Literature-Inspired Recipes vs. Active Learning Optimization: A Data-Driven Comparison for Accelerated Scientific Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between traditional literature-inspired methods and modern active learning (AL) optimization for discovery and development processes, with a focus on applications for researchers and drug development professionals. We explore the foundational principles of both approaches, detailing how literature-inspired methods leverage historical data and analogy, while AL uses iterative, data-driven feedback loops to guide experiments. The article examines methodological implementations across diverse fields, including materials science, drug discovery, and biotechnology, and provides a practical troubleshooting guide for common failure modes. Through comparative analysis of success rates, efficiency, and scalability, we validate the synergistic potential of combining both strategies to accelerate innovation, reduce costs, and overcome complex optimization challenges in biomedical research.

The Foundational Principles: Leveraging Historical Knowledge vs. Data-Driven Discovery

In the rapidly evolving fields of materials science and drug development, researchers face the constant challenge of accelerating the discovery and optimization of new compounds. Two distinct yet complementary computational approaches have emerged: literature-inspired recipes and active learning optimization. Literature-inspired recipes leverage vast historical knowledge from scientific publications to make intelligent initial guesses, mimicking how human researchers base new experiments on analogous prior work. In contrast, active learning employs algorithmic systems that iteratively design, execute, and interpret experiments based on incoming data, creating a closed-loop optimization process. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methodologies, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols, to inform researchers and drug development professionals in selecting appropriate strategies for their discovery pipelines.

Performance Comparison: Literature-Inspired Recipes vs. Active Learning

The table below summarizes quantitative performance data from published studies that implemented these approaches across different domains, including materials synthesis and biological optimization.

Table 1: Experimental Performance Comparison of Literature-Inspired Recipes and Active Learning

| Experimental Domain | Literature-Inspired Recipe Success | Active Learning Optimization Impact | Key Performance Metrics | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Materials Synthesis (A-Lab) | 35 of 41 novel compounds initially synthesized | Active learning improved yield for 9 targets, 6 of which had zero initial yield | 71% overall success rate; ~70% yield increase for specific targets (e.g., CaFe₂P₂O₉) | [1] |

| Fuel Cell Catalyst Discovery (CRESt) | Not the primary method | Explored 900+ chemistries, 3,500 tests over 3 months | 9.3-fold improvement in power density per dollar; record power density with 1/4 precious metals | [2] |

| Cell Culture Medium Optimization | Not the primary method | Significantly increased cellular NAD(P)H abundance (A450) | Successfully fine-tuned 29 medium components; both regular and time-saving modes effective | [3] |

| Protein Aggregation Formulation | Not the primary method | 60 iterative experiments via closed-loop system | Identified Pareto-optimal solutions for viscosity and turbidity; reduced required experiments | [4] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide clear methodological insights, this section details the experimental workflows and key algorithms used in the cited studies.

Protocol: Autonomous Materials Discovery with the A-Lab

The A-Lab represents a comprehensive implementation of both literature-inspired and active learning approaches for solid-state synthesis of inorganic powders [1].

Workflow Overview:

- Target Identification: Compounds are selected from computational databases (e.g., Materials Project) predicted to be stable or near-stable.

- Literature-Inspired Recipe Generation: Initial synthesis recipes are proposed by natural language processing models trained on a vast database of historical syntheses. A second model suggests heating temperatures.

- Robotic Execution: Robotic stations handle precursor dispensing, mixing in alumina crucibles, and loading into box furnaces for heating.

- Automated Characterization: Samples are ground robotically and analyzed via X-ray Diffraction (XRD).

- Phase Analysis: Machine learning models analyze XRD patterns to identify phases and determine yield (weight fraction of the target material).

- Active Learning Cycle: If the target yield is below a threshold (e.g., 50%), the ARROWS³ algorithm uses observed reaction data and thermodynamic computations to propose new, optimized synthesis routes with different precursors or conditions. This loop continues until success or recipe exhaustion.

Key Algorithm (ARROWS³): The active learning component is grounded in two hypotheses: (1) solid-state reactions often occur pairwise, and (2) intermediate phases with a small driving force for the final target should be avoided. The algorithm builds a knowledge base of observed pairwise reactions to predict and prioritize efficient synthesis pathways [1].

Protocol: Closed-Loop Formulation Optimization for Food Science

This protocol demonstrates a specialized active learning application for optimizing a liquid formulation containing whey protein isolate (WPI) and salts [4].

Workflow Overview:

- Initial Data Collection: 30 initial data points are collected by a robotic platform to build a preliminary dataset.

- Surrogate Model Training: A machine learning model (Thompson Sampling Efficient Multi-Objective Algorithm - TSEMO) is trained on the initial data to approximate the complex relationship between formulation components (protein, NaCl, CaClâ‚‚ concentration) and target properties (viscosity, turbidity).

- Iterative Experimentation:

- The TSEMO algorithm proposes new formulation recipes expected to improve the target objectives.

- The robotic platform automatically executes these recipes: dosing stock solutions, mixing, inducing aggregation, and measuring viscosity and turbidity.

- The new data is added to the training set.

- Pareto Optimization: Steps 2-3 are repeated (e.g., for 60 iterations) to identify a set of optimal solutions (Pareto front) that represent the best trade-offs between the multiple objectives.

Protocol: Active Learning for Cell Culture Medium

This protocol was designed to optimize a complex biological system with 29 different medium components for HeLa-S3 cell culture [3].

Workflow Overview:

- Baseline Data Acquisition: Cell culture is performed in 232 different medium combinations, and cell growth is assessed by measuring cellular NAD(P)H abundance (absorbance at 450nm, A450) as a proxy for viability and activity.

- Model Prediction and Validation:

- A Gradient-Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT) model is trained to predict A450 based on medium composition.

- The model proposes 18-19 new medium combinations predicted to improve growth.

- These are validated experimentally.

- Active Learning Loop: The new experimental data is added to the training set, and the process repeats, refining the model's accuracy and leading to progressively better medium formulations. A "time-saving" mode used data from 96 hours of culture to successfully predict outcomes normally requiring 168 hours.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The table below lists key materials and computational resources used in the featured experiments.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Autonomous Discovery Platforms

| Item Name | Function / Description | Example from Research |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Powders | Raw materials for solid-state synthesis; wide variety of inorganic oxides and phosphates. | Handled by A-Lab's robotic dispensing and mixing station [1]. |

| Alumina Crucibles | High-temperature containers for powder reactions during furnace heating. | Used in A-Lab's automated furnace station [1]. |

| Whey Protein Isolate (WPI) | Model protein for studying aggregation and formulation optimization. | Base component in robotic food formulation study (BiPRO 9500) [4]. |

| Stock Salt Solutions | To modify ionic strength and induce protein aggregation in liquid formulations. | Sodium chloride and calcium chloride solutions used in WPI aggregation [4]. |

| Cell Culture Media Components | 29 components (amino acids, vitamins, salts, etc.) to support cell growth. | Optimized for HeLa-S3 culture using active learning [3]. |

| CCK-8 Assay Kit | Colorimetric assay to measure cellular NAD(P)H abundance, indicating cell viability/metabolism. | Used for high-throughput evaluation of cell culture quality in active learning medium optimization [3]. |

| Ab Initio Computational Database | Database of computed material properties used for target selection and thermodynamic guidance. | The Materials Project database used by A-Lab and ARROWS³ algorithm [1]. |

| CDK2-IN-14-d3 | CDK2-IN-14-d3, MF:C21H25N5O4S, MW:446.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 4-Methylamphetamine, (-)- | 4-Methylamphetamine, (-)-, CAS:788775-45-1, MF:C10H15N, MW:149.23 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

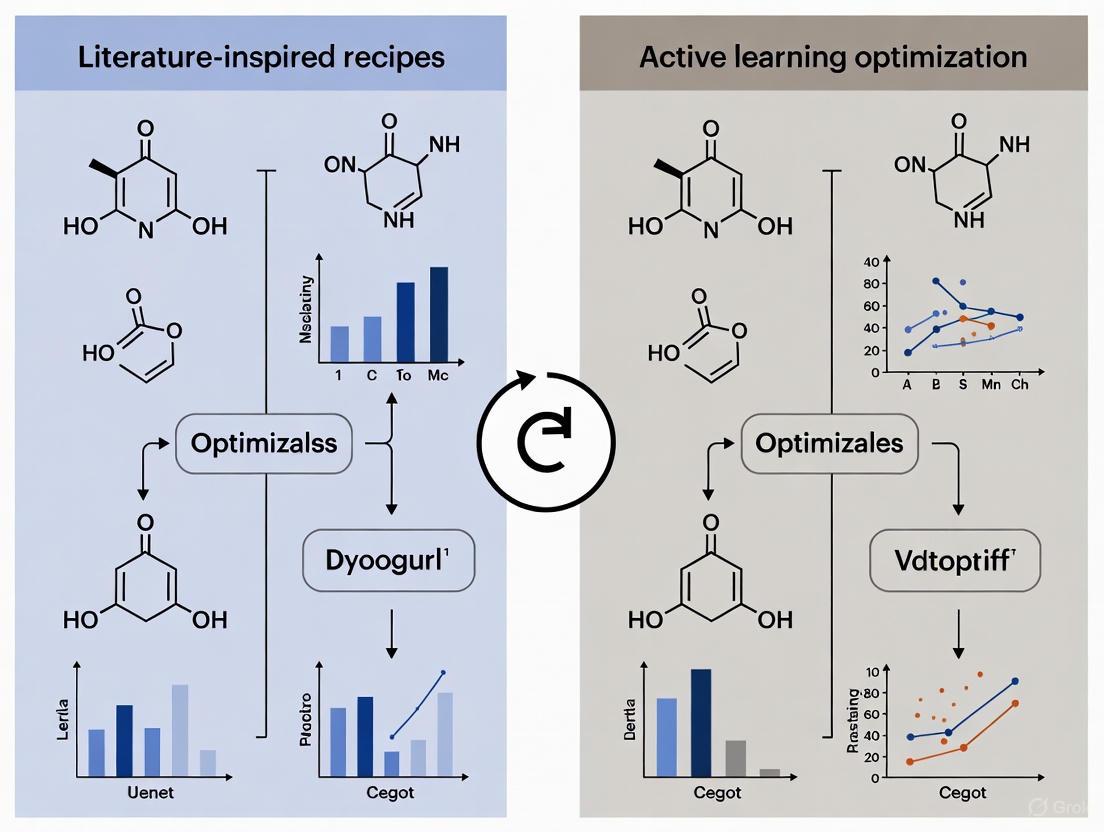

The following diagrams illustrate the logical structure and workflows of the two primary methodologies discussed.

Diagram 1: Literature-Inspired Recipe Workflow. This flowchart shows the iterative process of using historical data and natural language processing (NLP) to propose and test initial synthesis recipes. If initial attempts fail, the process of analyzing historical data for new analogies can be repeated.

Diagram 2: Active Learning Closed-Loop Optimization. This diagram visualizes the core active learning loop, where a surrogate model guides robotic experimentation. The data from each experiment updates the model, creating a cycle of continuous improvement until a stopping criterion is met.

In the pursuit of optimal solutions across scientific domains, from drug development to materials science, researchers often face a critical choice: to rely on established knowledge or to let data guide the exploration. On one hand, literature-inspired recipes leverage historical data and analogical reasoning, mimicking how human experts base new experiments on known successful precedents. On the other hand, active learning optimization employs iterative, data-driven feedback loops to intelligently navigate complex search spaces with minimal experimental cost. This guide objectively compares these approaches, examining their performance, experimental protocols, and applicability in modern research environments where efficiency in resource and time utilization is paramount.

The fundamental distinction lies in their operational philosophy. Literature-inspired methods excel when target problems closely resemble previously solved ones, effectively transferring domain knowledge. In contrast, active learning frameworks like Active Optimization (AO) are designed for scenarios with limited data, high-dimensional parameter spaces, and complex, non-convex genotype-phenotype landscapes where traditional optimizers struggle [5] [6]. These methods treat complex systems as 'black boxes' and use surrogate models to approximate the solution space, then iteratively select the most informative experiments to perform [6].

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Outcomes Across Domains

Extensive benchmarking across synthetic and real-world systems reveals distinct performance patterns between these approaches. The table below summarizes key comparative findings:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Literature-Inspired Recipes vs. Active Learning

| Metric | Literature-Inspired Recipes | Active Learning Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Success Rate (Novel Materials Synthesis) | 37% of tested recipes successful [1] | Optimized routes for 9 targets (6 with zero initial yield) [1] |

| Data Efficiency | Relies on existing literature data | Identifies optimal solutions with relatively small initial datasets (e.g., ~200 points) [6] |

| Handling of Epistasis/Non-linearity | Limited in highly non-linear landscapes [5] | Outperforms one-shot approaches in landscapes with high epistasis [5] |

| Dimensionality Limitations | Effective for lower-dimensional analogies | Successful in problems with up to 2,000 dimensions [6] |

| Adaptability to New Information | Static once designed | Dynamic; incorporates new data to refine predictions and escape local optima [6] |

Beyond these general metrics, specific case studies highlight the performance gap. In autonomous materials synthesis, the A-Lab successfully realized 41 of 58 novel target compounds. While literature-inspired recipes succeeded for 35 targets, active learning was crucial for optimizing synthesis routes for nine targets, six of which had completely failed using initial literature-based proposals [1]. In computational optimization, the DANTE (Deep Active Optimization) framework consistently identified superior solutions across varied disciplines, outperforming state-of-the-art methods by 10-20% in benchmark metrics while using the same number of data points [6].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Literature-Inspired Recipe Generation

The literature-inspired approach formalizes the human expert's process of reasoning by analogy:

- Target Analysis: The target material or problem is characterized by its key properties (e.g., chemical composition, structural type).

- Similarity Assessment: Machine learning models, often trained on vast literature databases using natural-language processing, assess "similarity" between the target and previously reported systems [1].

- Precursor/Parameter Selection: Based on the closest analogs found, initial synthesis recipes or experimental parameters are proposed. For materials synthesis, this includes selecting precursor compounds and a starting temperature predicted by a separate ML model trained on heating data [1].

- Static Experimentation: The proposed recipes are executed without an inherent feedback mechanism. Success depends heavily on the quality and relevance of the historical data.

Active Learning Optimization Loop

Active learning creates a closed-loop system that integrates prediction and experimentation. The following diagram illustrates the core workflow, exemplified by platforms like the A-Lab and algorithms like DANTE.

Diagram 1: Active Learning Workflow

The workflow consists of several key stages:

- Initialization: The process begins with a small initial dataset, either from historical data or a limited set of initial experiments [6].

- Model Training: A surrogate model (e.g., a deep neural network) is trained to approximate the complex relationship between input parameters and the output phenotype or property of interest. This model treats the system as a 'black box' [6].

- Candidate Selection & Prioritization: The trained model is used to search the vast parameter space for promising candidates. Advanced algorithms like DANTE employ a Neural-surrogate-guided Tree Exploration (NTE). The tree search uses a data-driven upper confidence bound (DUCB) to balance exploration (trying new regions) and exploitation (refining known good regions). Key mechanisms like conditional selection prevent value deterioration, and local backpropagation helps the algorithm escape local optima [6].

- Experimental Validation: The top-ranked candidates from the selection process are synthesized or tested in the real world (e.g., in a self-driving lab) [1].

- Database Update and Iteration: The results from the new experiments are added to the database. This iterative feedback loop closes as the enriched dataset is used to retrain and improve the surrogate model, guiding the next cycle of exploration [6] [1].

Successful implementation of these optimization strategies, particularly in experimental sciences, relies on a suite of computational and physical resources.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Active Learning

| Item | Function | Example Tools/Platforms |

|---|---|---|

| Surrogate Model | Approximates the complex, often non-linear genotype-phenotype landscape to predict outcomes. | Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) [6], Bayesian Models [5] |

| Acquisition Function | Guides the search by balancing exploration and exploitation to select the most informative next experiment. | Data-driven Upper Confidence Bound (DUCB) [6] |

| Ab Initio Database | Provides computed thermodynamic data and phase stability information for target identification and hypothesis generation. | The Materials Project [1] |

| Robotics & Automation | Executes physical experiments (e.g., dispensing, mixing, heating) reliably and reproducibly at high throughput. | Integrated robotic stations (A-Lab) [1] |

| Characterization Suite | Analyzes experimental outputs to determine success and quantify results (e.g., yield, phase purity). | X-ray Diffraction (XRD) with automated Rietveld refinement [1] |

| Reaction Database | A continuously updated knowledge base of observed reactions and intermediates to inform future recipe proposals. | Lab-specific pairwise reaction database [1] |

The comparative analysis demonstrates that literature-inspired recipes and active learning are not mutually exclusive but are powerfully complementary. Literature-based methods provide a strong, knowledge-driven starting point, while active learning offers a robust framework for optimization and discovery when precedents are lacking or ineffective.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the strategic implication is clear: an integrated workflow that uses literature-inspired reasoning for initial experimental design, followed by active learning for iterative optimization, can maximize efficiency and success rates. This hybrid approach leverages the vast wealth of historical knowledge while employing intelligent, adaptive algorithms to navigate the complexity and high-dimensionality of modern scientific challenges, ultimately accelerating the discovery of novel solutions.

In complex scientific fields like drug development and biomedicine, researchers are often faced with a fundamental choice: should they rely on established knowledge and historical data, or employ adaptive algorithms that can explore vast solution spaces autonomously? This guide objectively compares these two approaches—established knowledge-based methods (represented by literature-inspired recipes and pattern recognition from existing data) and adaptive algorithm-driven methods (exemplified by active learning frameworks)—across critical dimensions of research and development.

Established knowledge approaches leverage accumulated human expertise and documented patterns to create reliable starting points. In contrast, adaptive learning systems employ iterative cycles of machine learning prediction and experimental validation to navigate complex optimization landscapes with minimal initial data. The following analysis provides researchers with experimental data and comparative frameworks to determine when each methodology offers superior advantages.

Established Knowledge Approaches: Pattern Recognition and Historical Data

Core Methodology and Workflow

Established knowledge approaches rely on systematic analysis of existing information to identify patterns and formulate optimized solutions. These methods are particularly valuable when working with well-characterized systems or when seeking to formalize implicit domain expertise.

Network Analysis of Recipes: Researchers apply network science to analyze relationships within existing recipe databases, treating ingredients as nodes and their co-occurrences as edges. This approach reduces complexity by identifying fundamental laws and principles that govern successful formulations [7]. The process involves:

- Data Collection and Curation: Compiling large datasets of existing formulations (e.g., 2+ million recipes from aggregators like Yummly)

- Information Extraction: Parsing relevant components (ingredients, techniques) while filtering extraneous information

- Pattern Identification: Using quantitative analysis to discover statistically significant combinations and frequencies

- Recipe Formulation: Creating new combinations based on identified successful patterns [7]

Traditional Recipe Analysis: Before computational approaches, researchers employed qualitative analysis of recipes to understand cultural, economic, and socio-cultural phenomena. This methodology relies on expert interpretation of historical formulations and their contextual factors [7].

Experimental Evidence and Performance Metrics

Table: Performance of Established Knowledge Approaches in Various Domains

| Application Domain | Methodology | Key Findings | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food Recipe Development | Network Science | Identified Zipf-Mandelbrot distribution in ingredient usage; few ingredients (salt, water, sugar) are extremely popular while most are sparse [7] | Limited to combinations within existing data; cannot discover truly novel combinations outside historical patterns |

| Educational Resource Recommendation | Hybrid Recommendation (Collaborative Filtering + XGBoost) | Improved accuracy and diversity of learning material recommendations [8] | Requires substantial existing user interaction data |

| Course Selection Systems | Graph Theory + Data Mining | Provided practical solutions for course selection through accurate prediction methods [8] | Performance dependent on quality and completeness of historical data |

Adaptive Algorithm Approaches: Active Learning and Machine Learning

Core Methodology and Workflow

Adaptive algorithms, particularly active learning frameworks, employ an iterative feedback process that strategically selects valuable data points for experimental validation based on model-generated hypotheses. This approach is especially powerful when exploring large, complex solution spaces with limited initial data.

Diagram: Active Learning Workflow for Optimization. This iterative process combines machine learning with experimental validation to efficiently navigate complex solution spaces [9].

Active Learning Implementation Framework:

- Initial Model Training: Build preliminary machine learning model using limited labeled data

- Query Strategy Implementation: Apply selection functions (e.g., uncertainty sampling, diversity sampling) to identify most informative data points for experimental testing

- Experimental Validation: Conduct wet-lab experiments or simulations to obtain ground truth labels for selected data points

- Model Updating: Integrate newly labeled data into training set to improve model accuracy

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2-4 until predefined stopping criteria are met (performance plateau, resource exhaustion) [9]

Experimental Evidence and Performance Metrics

Table: Experimental Performance of Adaptive Learning in Scientific Optimization

| Application Domain | Algorithm | Performance Metrics | Compared to Established Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture Medium Optimization [3] | Gradient-Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT) | Significantly increased cellular NAD(P)H abundance; Prediction accuracy improved with each active learning round | Superior to traditional one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) and design of experiments (DOE) approaches |

| Nanomedicine Formulation [10] | Bayesian Optimization + Active Learning | Identified optimal nanoformulations with improved solubility, small uniform particle size, and stability from ~17 billion possible combinations | More efficient than systematic screening; reduced development time from months to weeks |

| Drug Discovery - Virtual Screening [9] | Various ML Algorithms + Active Learning | Accelerated high-throughput virtual screening; identified structurally diverse hits with desired properties | More efficient than random screening or traditional quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models |

| Educational Resource Recommendation [8] | Multimodal Fusion + Adaptive Learning | MAE = 0.01, MSE = 0.0053, Precision = 95.3%, Recall = 96.7% in predicting student needs | Outperformed collaborative filtering and knowledge graph approaches |

Direct Comparative Analysis: Key Differentiation Factors

Performance Across Optimization Scenarios

Table: Situational Advantages of Established Knowledge vs. Adaptive Algorithms

| Optimization Scenario | Established Knowledge Advantage | Adaptive Algorithm Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Data-Rich Environments | Excellent performance with comprehensive historical data [7] | Can leverage data but may provide diminishing returns |

| Data-Sparse Environments | Limited by incomplete or biased historical records | Superior performance; efficiently navigates spaces with minimal initial data [9] |

| Exploration of Novel Formulations | Limited to extrapolations from existing combinations | Excels at discovering non-intuitive, high-performing novel combinations [3] |

| Resource Constraints | Lower computational requirements; relies on curated knowledge | Higher computational requirements but reduces expensive experimental iterations [10] |

| Interpretability of Results | Highly interpretable; based on documented patterns and relationships | "Black box" challenges though white-box models like GBDT offer some interpretability [3] |

| Implementation Timeline | Faster initial implementation; slower refinement | Slower initial setup; faster convergence to optimized solutions [3] [10] |

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

Protocol 1: Validating Established Knowledge Approaches

- Data Collection: Compile comprehensive database of historical formulations (e.g., 584 freshwater fish recipes from 101 manuscript recipe books) [11] [7]

- Pattern Extraction: Apply network analysis to identify core components and successful combinations using tools like Python or R with Gephy, Visone, or Cytoscape

- Formulation Generation: Create new formulations based on identified patterns and statistical frequencies

- Experimental Testing: Validate formulated combinations through standardized assays (e.g., cell viability, solubility measurements)

- Performance Benchmarking: Compare against known benchmarks and random formulations

Protocol 2: Validating Adaptive Learning Approaches

- Initial Design Space Definition: Identify key variables and their ranges (e.g., 29 medium components with logarithmic concentration gradients) [3]

- Baseline Establishment: Test small set of initial conditions (e.g., 232 medium combinations) to establish baseline performance

- Active Learning Implementation:

- Employ GBDT or Bayesian optimization algorithms

- Implement query strategy (e.g., expected improvement, uncertainty sampling)

- Set iteration cycle (e.g., 18-19 new experiments per round)

- Experimental Validation: Conduct wet-lab experiments for selected conditions

- Model Updating and Iteration: Incorporate new data and repeat until performance plateaus (typically 3-4 rounds) [3]

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Optimization Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function in Established Knowledge Approaches | Function in Adaptive Learning Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| HeLa-S3 Cell Line [3] | Benchmark for comparing traditional vs. optimized media formulations | Primary experimental system for evaluating predicted medium combinations |

| Cellular NAD(P)H Assay (A450) [3] | Standard metric for evaluating cell culture performance based on historical benchmarks | Quantitative outcome measurement for active learning model training and validation |

| Recipe/Formulation Databases [7] | Primary source for pattern recognition and network analysis | Potential initial training data or benchmarking reference |

| Gradient-Boosting Decision Tree Algorithm [3] | Limited role; potentially for analyzing historical pattern predictive power | Core ML algorithm for predicting promising experimental conditions |

| Bayesian Optimization Framework [10] | Not typically used in established knowledge approaches | Core algorithm for navigating high-dimensional optimization spaces |

| Automated Experimentation Systems [10] | Limited application; primarily for validation | Essential for high-throughput experimental validation of algorithm-selected conditions |

Integration Strategies and Decision Framework

Hybrid Approach Implementation

The most effective optimization strategies often combine elements of both established knowledge and adaptive algorithms:

Diagram: Hybrid Knowledge-Algorithm Integration. This framework leverages historical knowledge to constrain search spaces while using adaptive algorithms for refinement [3] [7].

Decision Framework for Method Selection

Researchers should consider the following factors when selecting between established knowledge and adaptive algorithm approaches:

Data Availability: With extensive, high-quality historical data, established knowledge approaches are favorable. With limited data but capacity for experimental iteration, adaptive algorithms excel [9]

Solution Space Complexity: For well-understood systems with predictable relationships, established knowledge suffices. For high-dimensional, non-linear optimization problems (e.g., 29+ component media), adaptive algorithms are superior [3]

Innovation Requirements: When incremental improvements are sufficient, established knowledge approaches are efficient. When breakthrough innovations or non-intuitive solutions are needed, adaptive algorithms have demonstrated superior performance [3] [10]

Resource Constraints: Consider computational resources, experimental throughput, and domain expertise availability in selecting the appropriate methodology

Both established knowledge and adaptive algorithm approaches offer distinct advantages for optimization challenges in scientific research and development. Established knowledge methods provide interpretable, reliable solutions based on historical patterns, while adaptive algorithms excel at navigating complex, high-dimensional spaces with minimal initial data.

The emerging trend toward hybrid approaches that leverage historical knowledge to inform initial constraints while employing adaptive algorithms for refined optimization represents the most promising direction for future research. As active learning methodologies continue to advance and integrate with automated experimentation systems, their application across drug development, materials science, and biotechnology will undoubtedly expand, accelerating the pace of scientific discovery and optimization.

Methodologies in Action: Implementing AL and Literature-Based Strategies Across Fields

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics into scientific experimentation has given rise to autonomous laboratories, or self-driving labs, which are transforming the pace of materials discovery. A central question in this emerging field is how different AI-driven strategies compare in their ability to successfully synthesize novel materials. This guide objectively compares two predominant approaches within autonomous discovery: literature-inspired recipes and active learning optimization. The A-Lab, an autonomous laboratory for the solid-state synthesis of inorganic powders, serves as an ideal platform for this comparison, as it explicitly employs and tests both methodologies [1].

The core distinction between these approaches lies in their source of knowledge and adaptability. Literature-inspired recipes leverage existing human knowledge encoded in scientific publications, while active learning systems generate new knowledge through iterative, data-driven experimentation. Understanding the performance characteristics, strengths, and limitations of each method is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to implement autonomous discovery in their own work. This guide provides a detailed, data-driven comparison based on the experimental outcomes from the A-Lab, which successfully synthesized 41 of 58 target novel compounds over 17 days of continuous operation [1].

Experimental Performance Data: A Quantitative Comparison

The A-Lab's operation provided quantitative data on the performance of literature-inspired and active learning approaches. The table below summarizes the key outcomes for each method, offering a direct comparison of their efficacy.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Literature-Inspired Recipes vs. Active Learning Optimization

| Performance Metric | Literature-Inspired Recipes | Active Learning Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Total Successful Syntheses | 35 out of 41 successful targets [1] | Successfully optimized synthesis for 9 targets, 6 of which had zero initial yield [1] |

| Primary Function | Propose initial synthesis recipes based on historical data and analogy [1] | Improve failed recipes by proposing alternative reaction pathways [1] |

| Knowledge Source | Natural-language processing of text-mined synthesis literature [1] | Ab initio computed reaction energies and observed synthesis outcomes [1] |

| Success Rate Correlation | Higher success when reference materials are highly similar to the target [1] | Effective at overcoming low driving force reactions (<50 meV per atom) [1] |

| Key Advantage | Leverages accumulated human knowledge and established protocols | Discovers novel, optimized synthesis routes not evident from literature |

A critical finding from the A-Lab's operation was that while literature-inspired recipes provided a successful starting point for a majority of the targets, the overall success rate of 71% was only achievable through the complementary use of active learning. Active learning proved decisive in synthesizing materials that were initially out of reach for literature-based models, increasing the number of successfully obtained targets [1]. This demonstrates that a hybrid approach, which leverages the breadth of historical knowledge and the adaptive power of active learning, is highly effective for autonomous materials discovery.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear understanding of how the comparative data was generated, this section outlines the detailed experimental protocols for both the literature-inspired and active learning workflows as implemented in the A-Lab.

Protocol for Literature-Inspired Recipe Generation and Testing

The literature-based approach follows a structured workflow to translate published knowledge into actionable synthesis plans.

- Target Similarity Assessment: For a novel target compound, a machine learning model assesses its "similarity" to known materials. This model uses natural-language processing on a large database of syntheses extracted from the literature to identify analogous materials and reactions [1].

- Precursor Selection: Based on the similarity assessment, the system selects chemical precursors that have been historically used to synthesize analogous materials [1].

- Temperature Proposal: A second, separate machine learning model, trained on heating data from the literature, proposes an initial synthesis temperature for the solid-state reaction [1].

- Robotic Execution: The proposed recipe is executed autonomously by the A-Lab's robotic systems. Precursor powders are dispensed and mixed by a robotic arm before being transferred to an alumina crucible. The crucible is then loaded into a box furnace for heating [1].

- Product Characterization & Analysis: After cooling, the sample is ground into a fine powder and measured by X-ray diffraction (XRD). Probabilistic machine learning models analyze the XRD pattern to identify phases and determine the weight fraction of the target material. The success of a synthesis is defined as achieving a yield of >50% of the target phase [1].

Protocol for Active Learning Optimization (ARROWS3)

When a literature-inspired recipe fails, the A-Lab employs an active learning cycle called ARROWS3 to design improved synthesis routes.

- Hypothesis-Driven Pathway Design: The active learning algorithm is grounded in two core hypotheses:

- Database of Observed Reactions: The A-Lab continuously builds a database of pairwise reactions observed in its experiments. This allows it to infer the products of potential recipes without testing them, significantly reducing the experimental search space [1].

- Recipe Proposal: The algorithm uses ab initio computed formation energies from the Materials Project database to prioritize reaction pathways that avoid low-driving-force intermediates. It proposes alternative precursor combinations or reaction sequences that maximize the driving force toward the target compound [1].

- Iterative Experimentation: The newly proposed recipes are executed and characterized using the same robotic and analysis platform. The outcomes of these experiments are fed back into the active learning loop, further refining the algorithm's understanding and guiding subsequent iterations until a high-yield synthesis is achieved or all options are exhausted [1].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of the A-Lab, showcasing how literature-inspired synthesis and active learning optimization function together in a closed-loop system.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

The experimental protocols rely on a suite of specialized materials, software, and hardware. The table below details the essential components used in the A-Lab for autonomous materials discovery.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Autonomous Materials Discovery

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Specific Example / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Powders | Source of chemical elements for solid-state reactions; high purity is critical for reproducible synthesis. | Used as raw materials for synthesizing target oxides and phosphates; dispensed and mixed by robotics [1]. |

| Alumina Crucibles | Containment vessels for powder samples during high-temperature heating in box furnaces. | Withstand repeated heating cycles; used by the A-Lab to hold precursor mixtures during reactions [1]. |

| Ab Initio Databases | Computational data sources providing thermodynamic properties of materials to guide synthesis. | The Materials Project and Google DeepMind databases used for target stability screening and calculating reaction driving forces [1]. |

| Natural-Language Models (AI) | Machine learning models that parse and learn from the vast corpus of scientific literature. | Used to propose initial synthesis recipes based on analogy to historically reported procedures [1]. |

| Active Learning Algorithm (ARROWS3) | AI decision-making core that plans iterative experiments by integrating data and thermodynamics. | Proposes optimized synthesis routes when initial recipes fail, using observed reactions and computed energies [1]. |

| Robotic Arms & Automation | Physical systems that automate the manual tasks of sample preparation, heating, and transfer. | Enable 24/7 operation of the A-Lab, performing tasks from powder mixing to loading furnaces [1] [12]. |

| X-ray Diffractometer (XRD) | Primary characterization tool for identifying crystalline phases and quantifying their abundance in a sample. | Used after each synthesis to determine the success of a reaction and the yield of the target material [1]. |

| Trh hydrazide | Trh hydrazide, CAS:60548-59-6, MF:C16H23N7O4, MW:377.40 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| O-Demethyl muraglitazar | O-Demethyl muraglitazar, CAS:331742-23-5, MF:C28H26N2O7, MW:502.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The comparative data from the A-Lab presents a compelling case for a hybrid strategy in autonomous materials discovery. Literature-inspired recipes serve as a powerful and efficient starting point, successfully synthesizing the majority of targets when historical analogies are strong. However, their reliance on existing knowledge makes them inherently limited when confronting truly novel materials or stubborn synthetic challenges. Active learning optimization complements this by functioning as a dynamic and adaptive problem-solver, capable of diagnosing failures and discovering viable synthetic pathways that are non-obvious from the literature.

The most effective strategy, as demonstrated by the A-Lab's 71% success rate, is not to choose one over the other, but to integrate them into a single, closed-loop workflow. This synergy between accumulated human knowledge encoded in literature and the explorative power of AI-driven active learning represents the current state-of-the-art. It accelerates the discovery of novel materials by an order of magnitude faster than traditional manual research, paving the way for rapid advancements in fields ranging from drug development to energy storage [1] [12]. For research teams, the practical implication is to invest in platforms and methodologies that seamlessly combine both of these powerful approaches.

Active learning (AL), a machine learning paradigm that iteratively selects the most informative data points for evaluation, is emerging as a powerful tool to accelerate drug discovery. This guide compares the performance of traditional, literature-inspired methods against AL-driven optimization, providing objective experimental data and detailed protocols to inform research strategies.

Direct Comparison: Literature-Inspired vs. Active Learning Optimization

The choice between basing initial experiments on literature knowledge or deploying an active learning system represents a fundamental strategic decision. The table below summarizes a core comparative finding from a large-scale autonomous discovery campaign.

Table 1: Retrospective Comparison of Synthesis Success Rates

| Methodology | Number of Targets Attempted | Success Rate | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Literature-Inspired Recipes | 58 | 37% (35/95 targets) | Based on historical data and target similarity; effective for well-precedented chemistries. [1] |

| Active Learning Optimization | 9 (for which initial recipes failed) | 67% (6/9 targets) | Overcame initial failures by leveraging experimental data to avoid low-driving-force intermediates; optimized 9 targets, successfully obtaining 6. [1] |

The A-Lab, an autonomous laboratory for solid-state synthesis, demonstrated that while literature-inspired recipes are a valuable starting point, active learning is particularly powerful for solving challenging synthesis problems that initially fail. [1] This workflow allowed the lab to successfully synthesize 41 of 58 novel target compounds over 17 days.

Benchmarking AL Performance in Virtual Screening & Property Prediction

In computational drug discovery, AL strategies are benchmarked by how efficiently they reduce the number of experiments needed to build accurate models or find hit compounds.

Table 2: Performance of Active Learning Methods on Various Drug Discovery Tasks

| Application Area | Dataset | AL Method | Key Performance Result | Comparison Baseline |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solubility Prediction | Aqueous Solubility (9,982 molecules) [13] | COVDROP (Deep Batch AL) | Reached lower Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) more quickly. [13] | Outperformed k-means, BAIT, and random sampling. [13] |

| Affinity & ADMET Optimization | 10+ public & internal affinity/ADMET datasets [13] | COVDROP & COVLAP (Deep Batch AL) | Consistently led to the best model performance across datasets. [13] | Significant potential savings in experiments required to reach the same model performance. [13] |

| Virtual Screening | CDK2 and KRAS target spaces [14] | VAE with Nested AL Cycles | Generated novel, diverse molecules with high predicted affinity; for CDK2, 8 out of 9 synthesized molecules showed in vitro activity. [14] | Effectively explored novel chemical space beyond training data. [14] |

| Multi-Target Binding | Retrospective docking study [15] | Multiobjective AL | Improved retrieval of the top 0.04-0.4% binders from a dataset. [15] | Superior to greedy acquisition, due to better compute budget distribution. [15] |

A key challenge in batch active learning is selecting a diverse set of informative molecules. Advanced methods like COVDROP quantify prediction uncertainty and maximize the joint entropy of a selected batch, ensuring both high uncertainty and diversity to improve model performance efficiently. [13]

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear technical understanding, here are the detailed methodologies for two key studies cited in this guide.

Protocol 1: Autonomous Synthesis with the A-Lab

This protocol details the workflow for the solid-state synthesis of inorganic powders, as implemented by the A-Lab. [1]

- Target Identification: Stable target materials are identified from large-scale ab initio databases like the Materials Project.

- Initial Recipe Proposal: Up to five initial synthesis recipes are generated using ML models trained on historical literature data via natural language processing.

- Temperature Selection: A second ML model, trained on literature heating data, proposes a synthesis temperature.

- Robotic Execution:

- Preparation: Precursor powders are dispensed and mixed by a robotic arm and transferred to alumina crucibles.

- Heating: Crucibles are loaded into one of four box furnaces.

- Characterization: After cooling, samples are ground and analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD).

- Phase Analysis: XRD patterns are analyzed by probabilistic ML models to identify phases and their weight fractions, confirmed by automated Rietveld refinement.

- Active Learning Cycle: If the target yield is below 50%, the ARROWS³ algorithm uses observed reaction data and computed reaction energies from the Materials Project to propose new, optimized synthesis routes. This loop continues until success or recipe exhaustion.

Protocol 2: Generative AI with Nested Active Learning for Drug Design

This protocol describes a generative model workflow that integrates two nested AL cycles to design novel, drug-like molecules for specific targets like CDK2 and KRAS. [14]

- Initial Model Training: A Variational Autoencoder (VAE) is pre-trained on a general molecular dataset and then fine-tuned on a target-specific set.

- Molecule Generation: The VAE decoder is sampled to generate new molecular structures.

- Inner AL Cycle (Chemical Optimization):

- Generated molecules are evaluated by chemoinformatics oracles for drug-likeness, synthetic accessibility, and dissimilarity from the training set.

- Molecules passing these filters are added to a "temporal-specific" set.

- The VAE is fine-tuned on this set, steering generation toward desirable chemical properties.

- Outer AL Cycle (Affinity Optimization):

- After several inner cycles, molecules from the temporal set are evaluated by a physics-based affinity oracle (molecular docking simulations).

- Molecules with favorable docking scores are transferred to a "permanent-specific" set.

- The VAE is fine-tuned on this permanent set, directly optimizing for target binding.

- Candidate Selection: After multiple outer cycles, the best candidates from the permanent set undergo more intensive molecular simulations (e.g., binding free energy calculations) before final selection for synthesis.

The following diagram illustrates this nested workflow:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Platforms

Implementing the advanced protocols above requires a combination of computational tools, data resources, and robotic hardware.

Table 3: Key Reagents and Platforms for AL-Driven Discovery

| Item Name | Type | Primary Function in Workflow | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| A-Lab Platform [1] | Robotic Hardware & Software | Fully autonomous system for planning, executing, and analyzing solid-state synthesis experiments. | Synthesizing novel inorganic compounds without human intervention. [1] |

| Variational Autoencoder (VAE) [14] | Generative AI Model | Learns a continuous latent representation of molecular structure to generate novel, valid molecules. | Core of the generative AI workflow for de novo molecular design. [14] |

| Gradient-Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT) [3] | Machine Learning Model | A highly interpretable "white-box" ML model used to predict complex outcomes and identify feature importance. | Optimizing culture medium components by modeling their non-linear effects on cell growth. [3] |

| Materials Project Database [1] | Computational Data | A database of computed material properties used to identify stable, synthesizable target compounds. | Providing ab initio formation energies and phase stability data for the A-Lab. [1] |

| DeepChem Library [13] | Software Library | An open-source toolkit for deep learning in drug discovery, life sciences, and quantum chemistry. | Serving as a foundation for building and benchmarking deep learning models, including AL methods. [13] |

| ARROWS³ Algorithm [1] | Active Learning Software | An active learning algorithm that integrates computed reaction energies with experimental outcomes to predict optimal solid-state reaction pathways. | Proposing follow-up synthesis recipes when initial attempts fail in the A-Lab. [1] |

| Biotin-PEG3-TFP ester | Biotin-PEG3-TFP ester, MF:C25H33F4N3O7S, MW:595.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 4-Acetyl-3'-bromobiphenyl | 4-Acetyl-3'-bromobiphenyl, CAS:5730-89-2, MF:C14H11BrO, MW:275.14 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

→ Research Outlook and Challenges

While demonstrating significant promise, the application of active learning in more complex and clinical stages of drug development is still emerging. Current research successfully applies AL to preclinical stages like compound optimization, molecular generation, and virtual screening. [9] [16] [13] However, its direct use in optimizing clinical trial design or patient recruitment, as suggested by one study on educational interventions, [17] is not yet a widely documented application in the literature. Future development is needed to fully bridge this gap. Key challenges that remain for broader AL adoption include the seamless integration of advanced machine learning models, managing the inherent imbalance in biological data where active compounds are rare, and establishing robust, standardized AL frameworks for the unique demands of clinical-stage research. [9]

The optimization of complex formulations is a central challenge in food science and biotechnology. Traditional methods, which often rely on literature-derived recipes and iterative, one-factor-at-a-time experiments, are increasingly unable to keep pace with the demand for novel, sustainable, and high-performance products [18] [3] [4]. These conventional approaches are often too slow, expensive, and inefficient to adequately explore vast parameter spaces [18]. In response, Active Learning (AL), a subfield of machine learning, has emerged as a transformative methodology. This guide provides a comparative analysis of traditional literature-inspired methods and modern AL-driven optimization, presenting objective performance data and detailed experimental protocols to inform research and development strategies.

Understanding the Formulation Optimization Landscape

Formulation development in food and biotech involves combining components to achieve a product with specific target properties, such as texture, nutritional profile, metabolic yield, or stability. This process is inherently complex due to the non-linear interactions between ingredients and process parameters.

Literature-Inspired (Traditional) Approach: This method initiates the development process by identifying a known material or formulation that is similar to the desired target. For a new plant-based meat product, this involves selecting a target meat and cut, then choosing ingredients like plant proteins, fats, and binders based on published recipes and domain expertise [18]. The process then enters cycles of gradual improvement, where food scientists pilot production, probe texture, prepare samples, and survey consumers. A change to any parameter can cause significant and unpredictable variations in the final product, making this trial-and-error approach time-consuming, expensive, and inefficient, especially when considering the urgency of transforming our food system [18].

Active Learning (AL) Approach: AL is a machine learning framework designed for "expensive black-box optimization problems"—precisely the kind encountered in formulation science where experiments are costly and time-consuming. Instead of planning all experiments up-front, an AL algorithm iteratively selects the most informative experiments to perform. It starts with an initial dataset, builds a surrogate model (a computationally cheap approximation of the system), and uses an acquisition function to propose the next experiment that best balances exploration of the unknown parameter space and exploitation of promising regions [4]. The results from this experiment are added to the dataset, and the model is updated, creating a closed-loop system that rapidly converges on optimal formulations [19] [4].

The table below summarizes the core distinctions between these two paradigms.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of the Two Optimization Approaches

| Feature | Literature-Inspired (Traditional) Approach | Active Learning (AL) Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Core Philosophy | Analogy to known systems; gradual, sequential improvement | Data-driven, probabilistic exploration of parameter space |

| Experiment Selection | Based on domain expertise and historical precedent | Guided by a machine learning model to maximize information gain |

| Underlying Model | Heuristic, mental | Data-driven surrogate model (e.g., Gaussian Process Regression) |

| Key Strength | Leverages deep, established domain knowledge | High efficiency in navigating high-dimensional, complex spaces |

| Primary Limitation | Slow, costly, and prone to suboptimal local maxima | Requires an initial dataset; performance depends on model choice |

Comparative Analysis: Performance and Applications

The theoretical advantages of AL are borne out by its performance in real-world applications across food science and biotechnology. The following case studies and aggregated data demonstrate its superior efficiency and effectiveness.

Case Study 1: Optimizing Polymer Formulation Scale-Up

Scaling a lab-developed polymer formulation to production is a major bottleneck. Production-scale mixers impart different thermal and physical forces, often requiring multiple expensive trials to match the lab-scale product's properties.

Experimental Protocol: Researchers developed a customized AL tool using Bayesian optimization. The system integrated lab-scale data, historical scale-up data, and expert knowledge. A Gaussian process regression model learned the relationship between processing conditions and the resulting mechanical energy (a proxy for product properties). The AL algorithm then charted a course through processing conditions to find the parameters that matched the target mechanical energy with minimal experiments [20].

Results: The AL tool reduced the number of required production trials by over 50% compared to traditional methods. It was estimated that this approach could save approximately $90,000 per formulation by reducing the need for multiple production runs and shortening the time-to-market by several months [20].

Case Study 2: Accelerated Discovery of Novel Materials

The A-Lab, an autonomous laboratory for synthesizing novel inorganic powders, provides a stark contrast between literature-inspired and AL-driven discovery.

Experimental Protocol: Given a target material, the A-Lab first generated up to five initial synthesis recipes using a model trained on historical literature data, mimicking the human approach. If these recipes failed to produce a high yield, the system switched to its AL cycle, ARROWS3, which used active learning grounded in thermodynamics to propose improved recipes. Robotics executed the synthesis and characterization, with the results fed back into the loop [1].

Results: Over 17 days, the A-Lab successfully synthesized 41 of 58 novel target compounds. While 35 of these were synthesized using the initial literature-inspired recipes, the AL cycle was crucial for the remaining 6, successfully optimizing recipes that had initially failed. This highlights that literature knowledge provides a strong starting point, but AL is essential for overcoming subsequent barriers and achieving a high overall success rate (71%) [1].

Case Study 3: Optimizing a Food Bioprocess (Whey Protein Aggregation)

A fully automated closed-loop system was developed to optimize a liquid food formulation: the salt-induced cold-set aggregation of whey protein isolate (WPI).

Experimental Protocol: A milli-fluidic robotic platform handled dosing, mixing, and analysis. It was coupled with the Thompson Sampling Efficient Multi-Objective Optimization (TSEMO) algorithm. The system's objectives were to simultaneously optimize two continuous targets: viscosity and turbidity, by manipulating the concentrations of WPI, sodium chloride, and calcium chloride. The AL algorithm sequentially proposed new formulations to test based on all previous results [4].

Results: Starting from 30 initial data points, the AL system performed 60 iterative experiments autonomously over two runs. It successfully identified a Pareto front—a set of optimal solutions representing the best trade-offs between viscosity and turbidity. The study concluded that this methodology is a powerful, time-saving approach for optimizing complex food ingredients and products [4].

Table 2: Aggregated Quantitative Performance Comparison

| Application Domain | Traditional Approach Performance | Active Learning Approach Performance | Key Metric Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer Scale-Up [20] | Required 2-3 production runs | Achieved target in ≤1 run | >50% reduction in experiments; ~$90,000 saved/formulation |

| Novel Material Synthesis [1] | Literature-inspired success: 35/58 targets | AL-optimized success: 6/58 targets | AL enabled ~17% additional successes |

| Cell Culture Medium Optimization [3] | OFAT/DOE methods are time-consuming | Active learning fine-tuned 29 components | Significantly increased cellular NAD(P)H; optimized FBS reduction |

| Whey Protein Formulation [4] | Manual optimization is complex and slow | Closed-loop AL found Pareto front in 60 iterations | Fully autonomous optimization of multiple targets |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Models

To implement an AL-driven formulation optimization strategy, researchers require both computational and experimental tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for AL-Driven Formulation

| Item | Function in AL Workflow | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) Model | Serves as the surrogate model; predicts outcomes and quantifies uncertainty for new parameters. | Used to model drug dissolution profiles and polymer scale-up energy [19] [20]. |

| Thompson Sampling Efficient Multi-Objective Optimization (TSEMO) Algorithm | An acquisition function for multi-objective optimization; finds Pareto-optimal solutions. | Optimized whey protein formulation for viscosity and turbidity simultaneously [4]. |

| Automated Robotic Platform | Executes high-throughput, reproducible experiments (dosing, mixing, heating) based on AL proposals. | A-Lab for materials synthesis [1]; milli-fluidic platform for WPI [4]. |

| Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT) | A white-box ML model used for prediction and providing interpretable insights into parameter importance. | Optimized culture medium by fine-tuning 29 components [3]. |

| 6-Cyanonicotinimidamide | 6-Cyanonicotinimidamide, MF:C7H6N4, MW:146.15 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3-Methylheptanenitrile | 3-Methylheptanenitrile, CAS:75854-65-8, MF:C8H15N, MW:125.21 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow Visualization: Traditional vs. Active Learning

The fundamental difference between the two methodologies is encapsulated in their experimental workflows.

Diagram 1: Comparison of formulation optimization workflows. The AL workflow creates a closed, data-driven loop for efficient discovery.

The empirical data and case studies presented in this guide compellingly demonstrate that Active Learning represents a paradigm shift in formulation science for food and biotechnology. While literature-inspired recipes provide a valuable and often effective starting point, they are inherently limited by existing knowledge and inefficient experimentation. In contrast, AL frameworks excel at navigating complex, multi-dimensional parameter spaces, systematically reducing the number of experiments required to achieve superior results. The ability of AL to autonomously optimize for multiple objectives, such as maximizing yield while minimizing cost or improving one property without degrading another, makes it an indispensable tool for researchers and developers aiming to accelerate innovation and build more resilient and sustainable food and biotech systems.

The "Human-in-the-Loop" (HITL) paradigm represents a foundational framework in modern scientific research, strategically integrating human expertise with the computational power of Active Learning (AL) algorithms. In materials science and drug discovery, this approach bridges two complementary strengths: the robust pattern recognition and intuitive reasoning of domain experts, and the ability of AL systems to rapidly explore high-dimensional parameter spaces through iterative, data-driven experimentation. This integration is particularly valuable in environments characterized by limited data availability and high experimental costs, where purely human-driven approaches lack scalability and purely algorithmic methods risk converging on suboptimal solutions due to incomplete initial knowledge or unanticipated physical constraints.

Within this framework, two primary methodological approaches have emerged for initiating and guiding experimental campaigns: literature-inspired recipes and active learning optimization. Literature-inspired recipes leverage the vast repository of historical experimental knowledge encoded in scientific publications, using natural language processing and similarity metrics to propose initial synthesis conditions based on analogous, previously successful experiments. In contrast, active learning optimization employs algorithmic decision-making to select subsequent experiments based on real-time analysis of incoming data, continuously refining the experimental path toward desired objectives. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these approaches, examining their relative performance, optimal use cases, and implementation protocols through experimental data from diverse scientific domains.

Comparative Performance Analysis: Literature-Inspired vs. Active Learning Approaches

The effectiveness of literature-inspired versus active learning approaches varies significantly across domains, depending on factors such as search space complexity, data availability, and the well-established nature of the synthesis protocols. The table below summarizes key comparative findings from recent implementations across materials science and pharmaceutical research.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Literature-Inspired and Active Learning Approaches

| Domain/System | Literature-Inspired Success Rate | Active Learning Enhancement | Key Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Materials Synthesis (A-Lab) | 35/41 novel compounds initially synthesized | 6 additional compounds obtained via AL optimization | 71% overall success rate; 37% of 355 tested recipes produced targets | [1] |

| Cell Culture Optimization | Baseline using EMEM medium composition | Significant improvement in NAD(P)H abundance (A450) | Active learning fine-tuned 29 medium components; achieved improved growth with reduced FBS | [3] |

| ADMET Property Prediction | Not applicable (model-based optimization) | 70-80% time savings in qualitative extraction | COVDROP method superior to random sampling and other batch selection methods | [21] |

| Drug Discovery (Exscientia) | Historical industry benchmarks | ~70% faster design cycles; 10x fewer compounds synthesized | Clinical candidate achieved after synthesizing only 136 compounds vs. thousands typically | [22] |

The data reveals a consistent pattern: literature-inspired methods provide excellent starting points, successfully addressing a majority of synthesis targets, while active learning demonstrates particular strength in optimizing challenging cases and fine-tuning complex multi-parameter systems. The A-Lab implementation showcases this synergy, where initial literature-based attempts successfully synthesized many novel compounds, with active learning subsequently recovering additional targets that initially failed [1]. Similarly, in pharmaceutical development, the integration of AI and AL has demonstrated dramatic efficiency improvements, compressing discovery timelines from years to months and significantly reducing the number of compounds requiring synthesis and testing [22].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Literature-Inspired Synthesis for Novel Materials

The literature-inspired approach formalizes the intuitive process of human researchers who base new experiments on analogous prior work. The A-Lab's implementation provides a representative protocol for inorganic powder synthesis [1]:

- Step 1: Target Analysis – Compute decomposition energy and phase stability using ab initio databases (e.g., Materials Project). Filter targets for air stability.

- Step 2: Precursor Selection – Employ natural language processing models trained on historical synthesis literature to assess target similarity and propose precursor sets based on successful syntheses of analogous materials.

- Step 3: Temperature Optimization – Apply machine learning models trained on heating data from literature to recommend synthesis temperatures.

- Step 4: Robotic Execution – Transfer powders to alumina crucibles using automated dispensing and mixing systems.

- Step 5: Thermal Processing – Load crucibles into box furnaces using robotic arms, execute heating protocols.

- Step 6: Characterization & Analysis – Grind cooled samples into fine powders, acquire X-ray diffraction patterns, and determine phase fractions via probabilistic ML analysis and automated Rietveld refinement.

This methodology successfully synthesized 35 of 41 novel compounds in the A-Lab implementation, demonstrating the power of encoded historical knowledge for initial experimental design [1].

Protocol 2: Active Learning Optimization for Challenging Syntheses

When literature-inspired approaches fail to yield target materials, active learning provides an alternative optimization pathway. The ARROWS³ (Autonomous Reaction Route Optimization with Solid-State Synthesis) framework exemplifies this approach [1]:

- Step 1: Failure Analysis – Analyze unsuccessful synthesis products to identify intermediate phases formed during reaction.

- Step 2: Pathway Database Construction – Build and continuously expand a database of observed pairwise solid-state reactions from experimental results (88 unique pairwise reactions identified in A-Lab study).

- Step 3: Thermodynamic Prioritization – Compute driving forces for potential reaction pathways using formation energies from computational databases, prioritizing intermediates with large driving forces to form desired targets.

- Step 4: Recipe Selection – Propose alternative precursor sets or thermal profiles that avoid low-driving-force intermediates in favor of more thermodynamically favorable pathways.

- Step 5: Iterative Refinement – Execute proposed experiments, characterize products, and update reaction pathway database and models based on outcomes.

This approach successfully identified improved synthesis routes for nine targets in the A-Lab study, six of which had zero yield from initial literature-inspired recipes [1].

Protocol 3: Active Learning for Biochemical System Optimization

Active learning implementations for biological systems follow similar principles with adaptations for biochemical complexity. The cell culture medium optimization protocol demonstrates this approach [3]:

- Step 1: Initial Dataset Generation – Perform cell culture in a large variety of medium combinations (232 combinations in the referenced study) with component concentrations varied on a logarithmic scale.

- Step 2: Response Measurement – Quantify cellular NAD(P)H abundance via absorbance at 450 nm (A450) as a proxy for culture success using high-throughput chemical reaction assays (e.g., CCK-8).

- Step 3: Model Training – Implement Gradient-Boosted Decision Tree (GBDT) algorithm to learn relationships between medium components and cellular response.

- Step 4: Predictive Optimization – Use trained model to predict medium combinations likely to improve target response metrics.

- Step 5: Experimental Validation – Culture cells in algorithmically-proposed medium combinations and measure outcomes.

- Step 6: Model Refinement – Incorporate new experimental results into training dataset and iterate process.

This protocol successfully fine-tuned 29 medium components and identified formulations that significantly improved cell culture performance over standard EMEM medium, notably predicting reduced requirements for fetal bovine serum [3].

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

Literature-Inspired Synthesis Workflow

Active Learning Optimization Cycle

Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

The implementation of human-in-the-loop active learning systems requires specialized reagents, instrumentation, and computational infrastructure. The table below details key components referenced in the experimental studies.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Human-in-the-Loop Active Learning

| Category | Specific Examples | Function/Role in Workflow | Representative Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Databases | Materials Project, Google DeepMind stability data | Provide ab initio calculated phase stability and reaction energies for target selection and thermodynamic analysis | Target screening and decomposition energy calculation [1] |

| Literature Mining Tools | Natural language processing models trained on synthesis literature | Extract and codify historical synthesis knowledge for precursor selection and temperature prediction | Proposing initial synthesis recipes based on analogous materials [1] |

| Active Learning Algorithms | ARROWS³, GBDT, COVDROP, COVLAP | Guide iterative experiment selection by balancing exploration and exploitation based on incoming data | Optimizing synthesis pathways and culture medium composition [1] [3] [21] |

| Robotic Automation Systems | Automated powder handling, robotic arms, automated furnaces | Execute physical experiments with precision and reproducibility under software control | Solid-state synthesis and sample transfer in A-Lab [1] |

| Characterization Instruments | X-ray diffractometry, automated Rietveld refinement | Identify phase composition and quantify yield of synthesis products | Determining success/failure of synthesis experiments [1] |

| Cell Culture Assays | CCK-8, Multisizer, BioStudio-T, Haemocytometer | Quantify cell growth and viability for culture optimization | Measuring NAD(P)H abundance as indicator of culture success [3] |

| Pharmaceutical AI Platforms | Exscientia's Centaur Chemist, Insilico Medicine's Generative AI | Integrate multiple AI approaches for drug candidate design and optimization | Accelerating small-molecule drug discovery [22] |

The comparative analysis of literature-inspired recipes and active learning optimization reveals a powerful synergistic relationship rather than a competitive one. Literature-inspired approaches provide computationally efficient and often highly effective starting points by leveraging the collective knowledge of the scientific community, while active learning excels at optimizing challenging cases and exploring beyond historical precedents. The most successful implementations strategically combine both approaches, using literature-based methods for initial experimental design and reserving active learning for cases where conventional approaches fail or for fine-tuning complex multi-parameter systems.

Future developments in human-in-the-loop systems will likely focus on deeper integration of domain expertise throughout the active learning cycle, more sophisticated transfer learning between related material systems, and increased automation in hypothesis generation and experimental design. As these technologies mature, they promise to dramatically accelerate the discovery and optimization of novel materials and pharmaceutical compounds, while simultaneously building increasingly comprehensive databases of experimental knowledge to guide future scientific exploration.

Overcoming Barriers: A Troubleshooting Guide for Synthesis and Optimization Failures

In modern drug development, the transition from a promising therapeutic candidate to an effective, marketable product is fraught with specific, complex failure modes. Among the most pervasive are sluggish binding kinetics, unstable amorphous solid dispersions, and inaccuracies in computational predictions. Traditionally, the industry has relied on literature-inspired recipes—established formulation rules and documented chemical scaffolds—to navigate these challenges. However, the limitations of this retrospective approach are increasingly apparent. This guide objectively compares the performance of traditional, knowledge-based methods against emerging, data-driven strategies that leverage active learning optimization. By presenting quantitative data and detailed experimental protocols, we provide researchers and scientists with a framework for evaluating these paradigms across critical stages of drug development.

Failure Mode 1: Sluggish Binding Kinetics

The Challenge of Slow-Onset/Slow-Dissociation Inhibitors

Sluggish binding kinetics—referring to slow association and/or dissociation between a drug and its target—present a major challenge in lead optimization. While a long drug-target residence time (RT) can enhance efficacy and duration of action, its inadvertent occurrence can confound traditional potency assays (e.g., IC₅₀ determinations) that assume rapid equilibrium, leading to significant underestimation of a compound's true affinity [23]. Furthermore, for some targets, an excessively long RT can lead to prolonged off-target effects and toxicity, as evidenced by the antipsychotic drug haloperidol [24]. Classical pharmacological analysis, designed for moderate-affinity natural products, often fails under the conditions of modern drug discovery, which involve high target concentrations and miniaturized assay volumes. This infringement of classical assumptions means that the highest-affinity compounds, often the most valuable, are the most negatively impacted, adversely affecting decisions from lead optimization to human dose prediction [23].

Comparison of Analytical Approaches

The table below compares the performance of classical analysis methods against modern kinetic approaches for characterizing slow-binding inhibitors.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Methods for Analyzing Slow-Binding Kinetics

| Method Characteristic | Classical ICâ‚…â‚€ Analysis (e.g., Cheng-Prusoff) | Time-Dependent ICâ‚…â‚€ Shift Method | Apparent Rate Constant (kâ‚’bâ‚›) Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key Measured Output | Single ICâ‚…â‚€ value at assumed equilibrium | ICâ‚…â‚€ values at multiple pre-incubation times | Concentration-dependent kâ‚’bâ‚› from activity decay |

| Underlying Assumption | Rapid equilibrium binding; [Ligand] >> [Target] | Time-dependent change in apparent potency | Exponential decay of enzyme activity at fixed [I] |

| Handles Slow Kinetics? | No, leads to affinity underestimation | Yes, provides kᵢₙâ‚câ‚œ and Káµ¢ | Yes, provides kâ‚’â‚™, kâ‚’ff, and residence time |

| Throughput | High | Medium | Medium to High |

| Mechanistic Insight | Low, only equilibrium potency | Medium, classifies as covalent/time-dependent | High, distinguishes mechanism (1-step vs 2-step) |

| Experimental Complexity | Low | Medium | Medium |

Experimental Protocol: Rapid Kinetic Constant Determination

The following protocol, adapted from research on human histone deacetylase 8 (HDAC8), enables high-throughput categorization and kinetic profiling of slow-binding inhibitors and covalent inactivators [24].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a master mix of the target enzyme (e.g., HDAC8) in an appropriate assay buffer. Dispense the enzyme solution into a multi-well plate.