Lattice Optimization with GGA Calculations: A Comprehensive Guide for Materials and Drug Discovery

This article provides a detailed exploration of lattice optimization using Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) calculations, a cornerstone of modern computational materials science and drug discovery.

Lattice Optimization with GGA Calculations: A Comprehensive Guide for Materials and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a detailed exploration of lattice optimization using Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) calculations, a cornerstone of modern computational materials science and drug discovery. Tailored for researchers and development professionals, the content covers foundational principles, practical methodological applications, advanced troubleshooting techniques, and robust validation protocols. By synthesizing insights from recent first-principles studies and software documentation, this guide serves as a vital resource for accurately predicting material properties, accelerating virtual screening in drug design, and optimizing computational workflows for enhanced reliability and performance.

Understanding GGA and Lattice Optimization: Core Principles and Significance

The Role of Density Functional Theory (DFT) in Modern Computational Science

Density-functional theory (DFT) has evolved into the major workhorse of modern computational chemistry, materials science, and physics [1] [2]. This quantum-mechanical method calculates the electronic structure of atoms, molecules, and solids, offering a favorable price/performance ratio compared to wave function-based methods [2]. The computational efficiency of DFT allows researchers to study larger and more relevant molecular systems with sufficient accuracy, expanding the predictive power of electronic structure theory [2]. In recent years, DFT has become particularly valuable in lattice optimization research using Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) functionals, enabling rational materials design and mechanistic understanding across energy storage, biomedical technologies, and advanced materials development [3] [4]. Despite its widespread adoption, DFT practitioners face numerous challenges in obtaining accurate and reliable results, necessitating robust troubleshooting protocols and methodological awareness.

Technical Support Center: DFT Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why do my DFT calculations show large variations in free energy when I rotate the molecule?

A: This problem typically stems from insufficient integration grid density. DFT calculations evaluate the density functional over a grid of points, and grids that are too sparse lack rotational invariance. Even functionals with low grid sensitivity for energies (like B3LYP) can exhibit significant variations (up to 5 kcal/mol) in free energy calculations depending on molecular orientation [5].

Solution: Use larger integration grids. A pruned (99,590) grid is recommended for most calculations, particularly for free energy computations and with modern meta-GGA functionals [5].

Q2: How can I prevent spurious low-frequency modes from affecting my thermochemical predictions?

A: Low-frequency vibrational modes can artificially inflate entropy calculations due to inverse proportionality between frequency and entropy contribution. These modes may result from incomplete optimization or be inherent to the system [5].

Solution: Apply the Cramer-Truhlar correction, where all non-transition state modes below 100 cmâ»Â¹ are raised to 100 cmâ»Â¹ for entropy calculations. This prevents quasi-translational or quasi-rotational modes from being incorrectly treated as low vibrational modes [5].

Q3: Why are my symmetry numbers neglected in entropy calculations?

A: Many computational chemistry programs do not automatically account for molecular symmetry in entropy calculations. High-symmetry species have fewer microstates, which lowers entropy and affects reaction thermochemistry [5].

Solution: Automatically detect point groups and symmetry numbers for all species. For example, the deprotonation of water requires a correction of RTln(2) (0.41 kcal/mol at room temperature) because water has a symmetry number of 2 while hydroxide has a symmetry number of 1 [5].

Q4: What should I do when my DFT+U calculations show occupation matrix abnormalities?

A: Occupation matrices displaying values greater than one or NaN results indicate problems with pseudopotential normalization or compiler issues [6].

Solution: Change the U_projection_type to norm_atomic to normalize occupations. For severe cases (occupations ~2.5), this approach yields more meaningful results, though forces and stresses may not be available without additional fixes [6].

Q5: Why does my geometry change significantly after applying DFT+U?

A: DFT+U, particularly with large U values, can over-correct delocalization error and lead to bond over-elongation [6].

Solution: Implement a structurally-consistent U procedure: calculate U at the DFT level, relax the structure with that U value, recompute U on the DFT+U structure, and iterate until consistency. For systems with significant covalency, consider adding an intersite "+V" term (DFT+U+V) [6].

Troubleshooting Common DFT Calculation Errors

Integration Grid Errors

Problem: Inaccurate energies, especially for modern functionals and free energy calculations. Diagnosis: Grid sensitivity issues particularly affect meta-GGA functionals (M06, M06-2X), B97-based functionals (wB97X-V, wB97M-V), and the SCAN family [5]. Solution: Implement the recommended grid settings in the table below:

Table 1: Integration Grid Recommendations for DFT Calculations

| Functional Type | Minimum Grid Size | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Simple GGA (B3LYP, PBE) | (50,194) | Low grid sensitivity for energies |

| Meta-GGA (M06, SCAN) | (99,590) | High grid sensitivity |

| Free Energy Calculations | (99,590) | Reduces rotational variance |

| General Purpose | (99,590) | Recommended default |

SCF Convergence Failure

Problem: Self-consistent field procedure fails to converge. Diagnosis: Chaotic behavior in electron density iteration, common in systems with metallic character or near-degeneracies [5]. Solution Protocol:

- Implement hybrid DIIS/ADIIS strategy

- Apply 0.1 Hartree level shift by default

- Use tight integral tolerance (10â»Â¹â´)

- Consider smearing occupational degrees of freedom for metallic systems

DFT+U Implementation Issues

Problem: "Pseudopotential not yet inserted" error. Diagnosis: Hubbard atom not recognized by code [6]. Solution Protocol:

- Verify element is conventional for Hubbard terms (transition metals, rare earths, H, C, N, O)

- Check pseudopotential PP_HEADER for proper element specification

- Confirm HubbardU(n) corresponds to correct species in ATOMICSPECIES namelist

Problem: Unphysical U values from linear-response calculations. Diagnosis: Common in systems with nearly full (d¹â°, high-spin dâµ) or nearly empty (dâ°) manifolds [6]. Solution Protocol:

- Verify tight convergence thresholds and diagonalization settings

- Check linearity of response data

- Calculate U at slightly different geometries to assess scatter

- Consider if DFT+U is appropriate for the electronic structure

Workflow Diagrams for DFT Troubleshooting

SCF Convergence Protocol

DFT+U Occupation Matrix Troubleshooting

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools for Lattice Optimization

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Lattice Optimization with GGA-DFT

| Tool Category | Specific Function | Application in Lattice Research |

|---|---|---|

| Integration Grids | Numerical integration of functionals | Critical for accurate energy and force calculations in periodic systems |

| Pseudopotentials | Represent core electrons | Determine accuracy for transition metals in oxide materials |

| Hubbard U Corrections | Address self-interaction error | Essential for correct electronic structure in correlated lattice materials |

| Dispersion Corrections | Capture van der Waals interactions | Necessary for layered materials and molecular adsorption on surfaces |

| Homogenization Methods | Compute effective properties | Connect atomic-scale calculations to macroscopic material behavior [4] |

Advanced Methodologies for Lattice Research

Data-Driven Lattice Optimization Framework

Recent advances integrate DFT with machine learning for accelerated materials discovery. A representative framework for lattice optimization includes:

- Parametric Modeling: Use subdivision (SubD) modeling with Catmull-Clark algorithm to parametrically describe lattice morphologies and skeletons [4].

- Representative Volume Elements (RVEs): Generate 3×3×3 lattice units to ensure stable macroscale mechanical behavior while minimizing computational cost [4].

- Homogenization Method: Apply periodic boundary conditions to RVEs to compute effective elastic properties [4].

- Machine Learning Pipeline: Implement two-tiered ML models where the first tier estimates relative density and the second tier predicts elastic modulus [4].

- Genetic Algorithm Optimization: Drive inverse design to achieve target mechanical properties under constraints [4].

Experimental Validation Protocol

For validation of lattice materials designed with GGA-DFT:

- Model Conversion: Export optimized lattice structures to .x_t and .stl formats for additive manufacturing and finite element analysis [4].

- Mechanical Testing: Compare predicted elastic moduli with experimental compression tests.

- Error Quantification: Assess difference between DFT-predicted properties (typically <10% error with proper methodology) and experimental measurements [4].

This comprehensive troubleshooting guide provides lattice optimization researchers with practical solutions to common DFT challenges, enabling more accurate and reliable computational materials design.

Core Concepts and Theoretical Foundation

What is the fundamental improvement of GGA over LDA? While the Local Density Approximation (LDA) calculates the exchange-correlation energy using only the local electron density at each point in space, GGA incorporates the gradient of the electron density, which provides information about how the density is changing in space [7]. This simple but crucial enhancement allows GGA to better describe real molecular and solid-state systems where electron density is rarely uniform.

In which scenarios does GGA typically outperform LDA? GGA has demonstrated significant improvements over LDA in several key areas [7]:

- Atomization energies: The mean absolute error for a set of 20 simple molecules was reduced from 31.4 kcal/mol in LDA to 7.9 kcal/mol in GGA.

- Magnetic materials: GGA correctly predicts that solid iron is a bcc ferromagnet, whereas LDA incorrectly gives an fcc non-magnetic structure.

- Lattice constants: GGA generally provides more accurate lattice constants than LDA, though it may overcorrect in some cases.

- Weak interactions: GGA provides more realistic binding energy curves for rare-gas dimers and hydrogen-bonded systems compared to LDA.

What are the limitations of GGA that researchers should be aware of? Despite its improvements, GGA has known limitations [7]. It can fail when the Kohn-Sham wavefunction is not a single Slater determinant, or when non-interacting energies are nearly degenerate. GGA also does not adequately describe so-called "strong correlation" as found in Mott-Hubbard insulators, and it often underestimates band gaps in semiconductors and insulators.

Practical Implementation and Convergence

What are the essential parameters to converge in a plane-wave GGA calculation? For plane-wave basis set calculations, two critical parameters must be converged to ensure accurate results [8]:

- Plane-wave energy cutoff: Determines the maximum kinetic energy of the plane waves in the basis set.

- k-point mesh: Defines the sampling of the Brillouin zone for integrating over electronic states.

Table 1: Example Convergence Parameters for Fe BCC Structure with GGA

| Parameter | Convergence Criterion | Optimal Value for Fe BCC | Functional Dependence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plane-Wave Cutoff | 400 eV | System-dependent | |

| k-point Grid | 9×9×9 | Lattice symmetry | |

| Energy Tolerance | 0.03 eV | Research requirements |

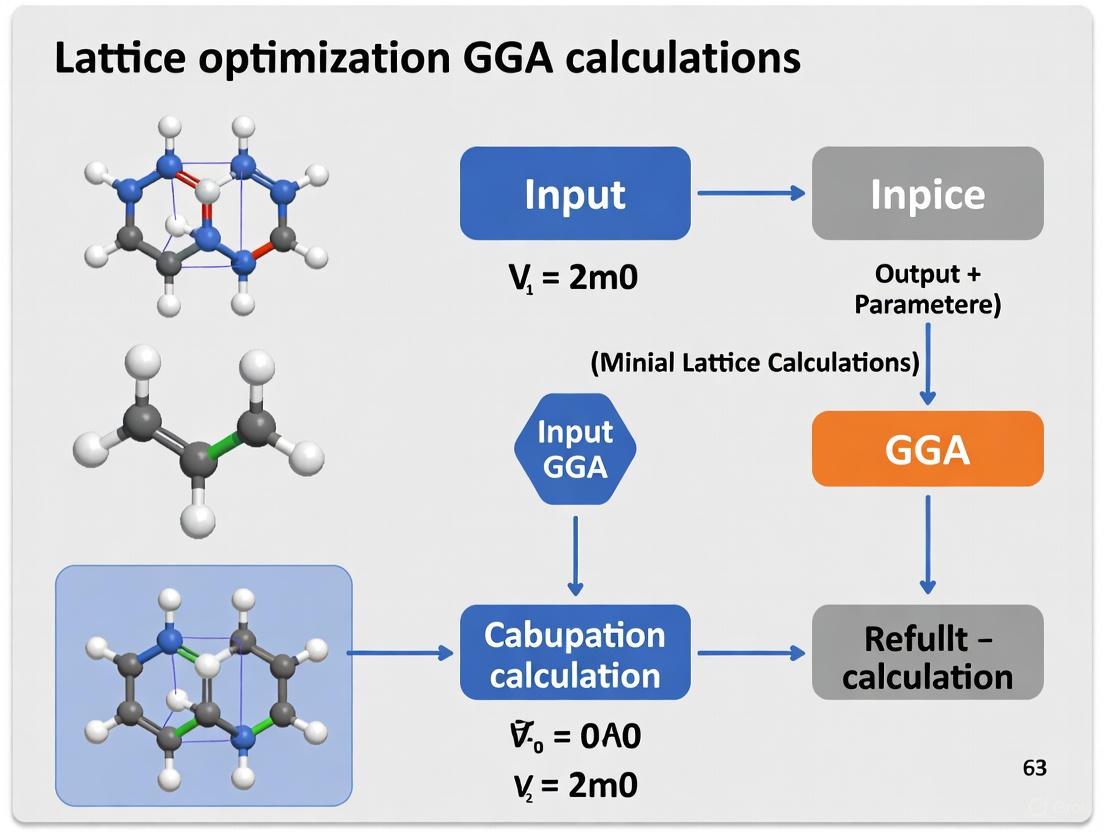

What workflow should I follow for a robust lattice parameter optimization? A systematic approach ensures reliable results. The diagram below illustrates a recommended workflow for determining optimal lattice parameters using GGA.

How do I implement this workflow in practice? Following the example of Fe BCC structure optimization [8]:

- K-point convergence: Perform this test at the smallest lattice parameter being investigated (e.g., 2.3 Ã…) with a high cutoff energy (e.g., 500 eV) to isolate the k-point dependence.

- Cutoff energy convergence: Use the experimental lattice parameter (e.g., 2.856 Å for Fe) and the converged k-point mesh (e.g., 9×9×9) to determine the appropriate cutoff.

- Energy calculations: Compute total energies for a range of lattice parameters (e.g., from 2.3 to 3.5 Ã… in intervals of 0.1 Ã…) using the converged parameters.

- Curve fitting: Fit a polynomial (typically 4th order) to the energy versus lattice parameter data and find the minimum to determine the optimal lattice parameter.

GGA Functionals and Methodologies

What are the key differences between popular GGA functionals like PBE and PW91? While both PBE (Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof) and PW91 are GGA functionals, PBE was developed as a simplification and refinement of PW91. In practice, they often yield very similar results for lattice parameters, as demonstrated in Fe BCC calculations where PBE gave 2.811 Ã… and PW91 gave 2.799 Ã…, both close to the experimental value of 2.856 Ã… [8]. The computational cost is also comparable between these functionals.

How do I set up a geometry optimization using GGA in different software packages? Different quantum chemistry packages have specific input requirements for GGA-based geometry optimizations:

Table 2: GGA Geometry Optimization Setup Across Computational Packages

| Software | Key Input Sections | Functional Selection | Accuracy Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| QuantumATK | SetLCAOCalculator, OptimizeGeometry |

HybridGGA.HSE06 (for insulators) |

Use Constrain space group to preserve symmetry [9] |

| CP2K | &MOTION (for GEO_OPT), &XC |

FUNCTIONAL PBE (in &XC) |

Set EPS_SCF and MAX_DR thresholds [10] |

| Gaussian | Route section (e.g., # OPT B3LYP/def2SVP) |

Directly in method (e.g., B3LYP, PBE1PBE) |

Default grid in G16 is UltraFine for better accuracy [11] |

When should I consider using constrained DFT (CDFT) with GGA? Constrained DFT is particularly useful in specific scenarios where standard GGA might delocalize electrons incorrectly [12]:

- Studying charge transfer phenomena and calculating electronic couplings

- Correcting spurious charge delocalization due to self-interaction error

- Parametrizing model Hamiltonians (e.g., the Heisenberg spin Hamiltonian) CDFT works by adding constraint potentials to the Kohn-Sham energy functional to enforce electron or spin density localization within specific regions of space.

Troubleshooting Common Computational Issues

Why is my geometry optimization not converging, and how can I fix it? Non-convergence in GGA-based geometry optimizations can stem from several sources:

- Insufficient SCF convergence: Tighten the EPS_SCF tolerance or try different SCF solvers (e.g., switching to OT in CP2K) [10].

- Poor initial structure: Consider pre-optimizing with a faster method or applying rational constraints to problematic atoms.

- Insufficient optimization steps: Increase the maximum number of optimization steps or try different optimization algorithms (BFGS vs. LBFGS).

How do I handle constraint convergence issues in CDFT-GGA calculations? For constrained DFT calculations using GGA functionals [12]:

- Use the

OUTER_SCFsection in CP2K withTYPE CDFT_CONSTRAINTand appropriate convergence thresholds (EPS_SCF) - Select appropriate optimizers (

NEWTON_LSoften works well) - Adjust the

STEP_SIZEparameter if the constraint Lagrangian multipliers oscillate - Ensure proper definition of atom groups and constraint types (charge or spin)

Why are my GGA-calculated band gaps smaller than experimental values? This is a known systematic error of standard GGA functionals [7]. GGA tends to underestimate band gaps in semiconductors and insulators. For more accurate band gaps, consider:

- Using hybrid functionals (e.g., HSE06) that mix a portion of exact Hartree-Fock exchange [9]

- Applying GW perturbation theory methods

- Using DFT+U approaches for strongly correlated systems

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for GGA Lattice Optimization Research

| Tool/Reagent | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Pseudopotentials | Represents core electrons and ionic potential | Essential for plane-wave calculations; choice affects accuracy (e.g., USPP, PAW) [8] |

| Basis Sets | Mathematical functions for electron orbitals | LCAO calculations require careful basis set selection (e.g., numerical, Gaussian) [9] |

| k-point Meshes | Samples the Brillouin zone | Critical for metallic systems; affects energy convergence [8] |

| Solvation Models | Implicitly models solvent effects | Required for surface and interface calculations (e.g., PCM, SMD) [13] |

| Population Analysis | Partitions electron density among atoms | Used in CDFT constraints and charge analysis (e.g., Becke, Hirshfeld) [12] |

| Retinamide, N,N-diethyl- | Retinamide, N,N-diethyl-|C24H37NO|Research Use Only | Retinamide, N,N-diethyl- (CID 11631762) is a synthetic retinamide for cancer and biochemistry research. This product is for Research Use Only and not for human or veterinary diagnostics or therapeutic use. |

| Ubistatin B | Ubistatin B, CAS:799764-66-2, MF:C34H22N6O12S4, MW:834.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Lattice optimization, often referred to as structural relaxation, is a fundamental computational procedure in materials science and solid-state physics aimed at determining the most stable atomic configuration of a crystal. This process yields the lowest-energy state (relaxed structure) by simultaneously adjusting both atomic coordinates and lattice vectors to find the minimum on the potential energy surface [14]. For researchers employing generalized gradient approximation (GGA) functionals in density functional theory (DFT) calculations, proper lattice optimization is crucial for obtaining accurate predictions of material properties, as variations in lattice parameters can substantially influence electronic structure, mechanical behavior, and other key characteristics [14] [15].

Traditional ab initio approaches to lattice optimization, particularly those based on density-functional theory (DFT), involve computationally intensive iterative procedures with two nested loops. The inner loop solves the Kohn-Sham equations to self-consistency for a fixed geometry, yielding total energy and atomic forces, while the outer loop moves atoms according to those forces and repeats the process until convergence criteria are met [14]. In GGA calculations specifically, the optimization must account for both atomic displacements and lattice deformations, as the cell geometry directly affects fundamental properties like electronic band structure and density [14] [15].

Fundamental Concepts: Troubleshooting FAQ

Why does my SCF (Self-Consistent Field) calculation fail to converge during lattice optimization?

SCF convergence failures represent one of the most common challenges in DFT calculations, particularly for metallic systems or slabs with complex electronic structures. Several strategies can address this issue:

Conservative mixing parameters: Reduce SCF mixing parameters to more conservative values:

Alternative convergence algorithms: Switch from the default DIIS method to MultiSecant or LIST methods:

Finite electronic temperature: Apply a small electronic temperature to improve convergence, particularly useful during initial geometry optimization steps when precise energies are less critical [16].

Basis set strategies: Begin optimization with a smaller basis set (e.g., SZ) that converges more easily, then restart the calculation with the target basis set from the preliminary converged result [16].

Why does my geometry optimization not converge even with converging SCF?

When SCF convergence is achieved but geometry optimization stalls, the issue typically lies in insufficient accuracy of the calculated forces and stresses:

Increase integration accuracy: Enhance numerical integration grids and radial points:

Verify k-point sampling: Ensure adequate k-space sampling, particularly for metallic systems or those with complex Fermi surfaces [16].

Check force thresholds: Confirm that force convergence thresholds are appropriate for your system; overly stringent criteria may prevent convergence [16].

Why does lattice optimization with GGA yield inaccurate lattice constants?

GGA functionals are known to exhibit systematic errors in predicting lattice parameters, primarily due to their inadequate treatment of long-range electron correlations:

Dispersion corrections: GGA struggles with systems exhibiting strong electron-electron interactions and does not account for long-range van der Waals forces, often leading to overestimation of lattice constants [15]. Incorporating dispersion corrections (DFT-D) significantly improves structural parameter predictions for layered materials and other systems where van der Waals interactions play an important role [15].

Functional selection: Different GGA functionals (PBE, PBEsol, etc.) exhibit varying performance for structural properties. PBEsol is specifically designed for solids and often provides better lattice parameters than standard PBE [15].

Integration grid density: For Gaussian basis set codes, using the UltraFine integration grid (Int=UltraFine) reduces numerical noise in force and stress calculations, leading to more reliable geometry convergence [17].

How do I handle "dependent basis" errors during optimization?

A "dependent basis" error indicates near-linear dependence in the Bloch basis set, threatening numerical stability:

Confinement: Apply spatial confinement to diffuse basis functions, particularly for highly coordinated atoms or slab systems [16].

Basis set pruning: Remove the most diffuse basis functions or select a more appropriate basis set designed for solid-state calculations [16].

Layer-specific treatments: In slab systems, use confinement only on inner layers while preserving standard basis sets on surface atoms to properly describe wavefunction decay into vacuum [16].

Why does my frequency calculation indicate non-convergence after successful optimization?

A structure that passes optimization convergence criteria but fails frequency convergence tests is not at a true stationary point:

Hessian discrepancies: This discrepancy arises because optimizations typically use approximate Hessians, while frequency calculations employ exact analytical second derivatives [17].

Restart strategy: Continue optimization from the final structure using the exact Hessian from the frequency calculation:

Integration grid effects: For DFT calculations, numerical noise from integration grids can prevent true convergence; using denser grids (Int=UltraFine) helps resolve this [17].

Workflow and Methodologies

Systematic Lattice Optimization Protocol

A robust approach to lattice optimization for general crystal structures follows an iterative cyclic procedure where parameters are optimized sequentially until all parameters converge within desired tolerances [18]:

- Isotropic volume optimization while maintaining initial shape ratios

- Lattice parameter ratio optimization (b/a, c/a) at constant volume

- Lattice angle optimization (α, β, γ) with fixed other parameters

- Repeat until all parameters stabilize within target accuracy

For hexagonal crystals, this simplifies to iterating between volume and c/a ratio optimization until both parameters converge [18].

Finite-Temperature Automation for Challenging Systems

For systems difficult to converge at the beginning of geometry optimization, automated protocols can progressively tighten convergence criteria:

This approach uses higher electronic temperature and looser SCF convergence in early optimization stages when forces are large, systematically tightening criteria as the geometry approaches convergence [16].

Workflow Visualization

Lattice Optimization Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools

Table 1: Essential Computational Tools for Lattice Optimization

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Lattice Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| DFT Codes | QUANTUM-ESPRESSO [15], WIEN2k [19], exciting [18] | Solves Kohn-Sham equations to compute total energy, forces, and stresses for crystal structures |

| Geometry Optimization Algorithms | BFGS, Conjugate Gradient, FIRE | Iteratively updates atomic positions and lattice vectors to minimize total energy |

| SCF Convergence Accelerators | DIIS [16], MultiSecant [16] | Accelerates convergence of the self-consistent field procedure |

| Basis Sets | Plane Waves, LAPW, Gaussian Type Orbitals | Provides basis for expanding Kohn-Sham wavefunctions with different accuracy/efficiency tradeoffs |

| Pseudopotentials | Norm-Conserving, Ultrasoft, PAW | Represents core electrons to reduce computational cost while maintaining accuracy |

| Structure Analysis Tools | sgroup [18], VESTA, ASE | Verifies crystal symmetry and analyzes optimized structures |

Advanced Approaches: Machine Learning Accelerated Optimization

Recent advances in machine learning offer alternative pathways for lattice optimization:

Iteration-free models: End-to-end graph neural networks like E3Relax directly map unrelaxed to relaxed structures by promoting both atoms and lattice vectors to graph nodes, enabling unified symmetry-preserving optimization in a single step [14].

Harmonic force field approximations: Methods like the Structure Beautification Algorithm (SBA) use chemistry-driven parameterization to construct surrogate harmonic potentials that can bypass expensive DFT relaxation in rigid systems, reducing computational costs by 30% or more in flexible systems [20].

Hybrid approaches: Machine learning models can generate high-quality initial configurations for traditional DFT optimization, significantly reducing the number of optimization steps required to reach convergence [14] [20].

GGA-Specific Considerations and Validation

Limitations of Standard GGA Functionals

When performing lattice optimization with GGA functionals, researchers should be aware of several systematic limitations:

Van der Waals interactions: Standard GGA does not account for long-range dispersion forces, leading to poor performance for layered materials, molecular crystals, and other systems where van der Waals interactions contribute significantly to cohesion [15].

Lattice constant overestimation: GGA typically overestimates lattice constants, while LDA underestimates them; DFT-D methods provide improved accuracy by adding empirical dispersion corrections [15].

Strongly correlated systems: GGA performs poorly for systems with strong electron correlations (e.g., transition metal oxides), where more advanced functionals (DFT+U, hybrid functionals) may be necessary [15].

Validation of Optimized Structures

After successful lattice optimization, several validation steps are essential:

Frequency calculations: Verify that the optimized structure is a true stationary point by confirming the absence of imaginary frequencies for minima [17].

Stress tensor examination: Check that all components of the stress tensor are near zero, confirming the structure is under no artificial stress [16].

Symmetry verification: Use tools like sgroup to verify that the optimized structure maintains the expected space group symmetry [18].

Property convergence: Confirm that key properties (e.g., band gap, magnetic moment) are converged with respect to further optimization steps.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why are my calculated equilibrium lattice constants significantly different from experimental values?

This is a common issue in GGA calculations. The Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) tends to overestimate bond lengths, leading to larger equilibrium lattice constants compared to experimental values. For example, in studies of molybdenum pnictides, GGA calculations systematically produce specific lattice constants that can be compared with experimental data [21]. To troubleshoot:

- Verify your pseudopotential choice: Softer potentials with minimal valence electrons may sacrifice accuracy for computational efficiency [22].

- Ensure complete convergence: Run multiple calculations with varying lattice parameters and fit the energy-volume curve using the Murnaghan equation of state to find the true minimum [21].

- Check k-point sampling: Insufficient k-points can lead to inaccurate energy comparisons between different lattice parameters.

2. How can I improve band gap accuracy in GGA calculations for semiconductor materials?

GGA is known to underestimate band gaps in semiconductors and insulators. While this is a fundamental limitation of the functional, you can address it through:

- Using more accurate pseudopotentials: For optical properties and band structure calculations, avoid soft potentials (_s) and consider harder variants or those specifically designed for excited-state properties [22].

- Implementing GGA+U: For systems with localized d or f electrons, adding a Hubbard U parameter can significantly improve band gap accuracy by correcting the excessive delocalization in standard GGA [21].

- Verification with all-electron methods: Compare results with all-electron calculations where computationally feasible to validate your pseudopotential approach [23].

3. What causes unphysical oscillations in my density of states (DOS) plots?

Unphysical oscillations or spikes in DOS typically indicate insufficient k-point sampling. Unlike band structures which follow specific paths in the Brillouin zone, DOS calculations require dense integration across the entire Brillouin zone. Implement these solutions:

- Increase the k-point mesh systematically until the DOS converges.

- Use the tetrahedron method for DOS integration rather than Gaussian smearing.

- Verify your energy cutoff: Too low cutoff can also cause irregularities in wavefunction representations [22].

4. My structural optimization fails to converge – what steps should I take?

Failed structural optimization can stem from multiple sources:

- Reduce the initial atomic displacements: Start with structures closer to the expected minimum.

- Adjust optimization algorithm: Switch between Conjugate Gradient (CG), Broyden, or FIRE algorithms. Broyden optimization has been shown to need about half the steps of CG in some systems [24].

- Loosen convergence criteria initially: Use higher force tolerances (e.g., 0.1 eV/Ã…) for preliminary optimizations before tightening.

- Check stress tensor components: For variable-cell optimizations, ensure both forces and stresses are converging [24].

5. How do I select the appropriate pseudopotential for my GGA calculation?

Pseudopotential choice critically impacts all GGA-calculated properties. Follow this systematic approach:

- Use the hardest potential feasible: For accurate results, prefer standard or hard (h) potentials over soft (s) variants, especially for magnetic properties or short bonds [22].

- Include semicore states when necessary: For transition metals and elements with shallow core states, use _pv or _sv potentials that treat semicore states as valence [25].

- Maintain consistency: Use the same pseudopotential type across all elements in your system when possible.

- Consult recommended POTCAR lists from established sources like the Materials Project [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inaccurate Metallic Behavior in Predicted Band Structures

Symptoms: Systems known to be metallic show spurious band gaps, or semiconductor band structures appear overly metallic.

Solution Protocol:

- Verify k-point sampling: Increase k-point density by 50-100% and recalculate. Metallic systems require dense sampling near the Fermi level.

- Check pseudopotential transferability: Use harder pseudopotentials or those with more valence electrons, particularly for d-electron systems [22].

- Examine partial DOS: Calculate projected DOS to identify which orbitals contribute states near the Fermi level.

- Implement tetrahedron method: For DOS calculations in metals, use the tetrahedron method with Blöchl corrections instead of Gaussian smearing.

Verification Method: Calculate the electronic density of states at a very high k-point density (e.g., 24×24×24 for cubic systems) and check that the DOS at Fermi level (N(E~F~)) converges to within 5%.

Problem: Poor Convergence in Variable-Cell Structural Optimizations

Symptoms: Oscillating lattice parameters, non-monotonic energy changes, or failure to reach force/stress tolerances.

Solution Protocol:

- Decouple atomic and lattice optimizations:

- First optimize atomic positions with fixed cell vectors

- Then perform variable-cell optimization starting from the pre-relaxed structure [24]

- Adjust optimization mass parameters: In quenched molecular dynamics approaches, tune the

ParrinelloRahmanMassparameter to better couple atomic and lattice degrees of freedom [24] - Use stepped convergence:

- Start with loose tolerances (e.g., 0.1 eV/Ã…, 0.5 GPa)

- Progressively tighten to final values (e.g., 0.01 eV/Ã…, 0.01 GPa)

- Switch algorithms: If conjugate gradients fail, try the FIRE algorithm or quenched molecular dynamics, which often show better convergence for difficult cases [24].

Verification Method: Monitor both energy and stress tensor components throughout optimization. A properly converging system should show generally decreasing energy magnitude and oscillatory but diminishing stresses.

Problem: Unphysical Magnetic Ground States in Transition Metal Compounds

Symptoms: Systems with known magnetic ordering (ferromagnetic, antiferromagnetic) converge to incorrect magnetic states or non-magnetic solutions.

Solution Protocol:

- Force initial magnetic moments: For transition metal compounds, initialize atomic moments to reasonable values (e.g., 3-5 μ~B~ for 3d metals)

- Use GGA+U for correlated systems: Implement DFT+U with appropriate U parameters (typically 3-6 eV for 3d transition metal compounds) [21]

- Compare magnetic configurations: Explicitly calculate and compare energies of ferromagnetic, antiferromagnetic, and non-magnetic states [21]

- Select appropriate pseudopotentials: Use _pv or _sv potentials that properly treat semicore states as valence for magnetic elements [25]

Verification Method: Calculate the energy difference between magnetic orderings (ΔE = E~FM~ - E~AFM~) with multiple U values to ensure the correct ground state is robust.

GGA Calculation Parameters and Performance

Table 1: Recommended Pseudopotential Types for Common Elements in GGA Calculations

| Element Type | Standard | For Magnetic Properties | For Optical Properties | Hard Potential | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Row (B-F) | Standard | Standard | Standard | _h | Hard potentials have extremely high cutoffs (~700 eV) [25] |

| Alkali Metals | _pv | _sv | _pv | _sv | _sv includes semicore states but increases computational cost [25] |

| Transition Metals | _pv | _sv | _pv | _sv | _sv essential for accurate magnetic moments [22] |

| Group IV (Si, Ge) | Standard | Standard | _d | _h | _d includes d-states in valence [25] |

Table 2: Convergence Thresholds for GGA Property Calculations

| Property | Force Tolerance | Energy Tolerance | Stress Tolerance | k-point Density | Typical System |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equilibrium Lattice | 0.01 eV/Ã… | 10^-5 eV | 0.1 GPa | 8-12 / Ã… | MoX (X=As, Sb, Bi) [21] |

| Band Structure | 0.02 eV/Ã… | 10^-5 eV | 0.5 GPa | 12-16 / Ã… | Semiconductor compounds |

| Density of States | 0.02 eV/Ã… | 10^-5 eV | 0.5 GPa | 16-24 / Ã… | Metallic systems |

| Full Magnetic | 0.01 eV/Ã… | 10^-6 eV | 0.1 GPa | 12-16 / Ã… | Transition metal compounds [21] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Equilibrium Lattice Constants

Based on: Volume optimization procedures for molybdenum pnictides [21]

Procedure:

- Initial Structure Setup

- Create initial crystal structure with estimated lattice parameters

- Select appropriate pseudopotentials (e.g., _pv for transition metals) [22]

- Set energy cutoff to at least 1.3× the maximum ENMAX in pseudopotentials

Energy-Vector Calculations

- Calculate total energy for 7-11 different volumes (typically ±10-15% of initial estimate)

- Use consistent k-point sampling across all volumes

- Employ symmetry-preserving lattice distortions

Equation of State Fitting

- Fit energy-volume data to Murnaghan equation of state [21]

- Extract equilibrium lattice constant from fit minimum

- Calculate bulk modulus as verification

Verification Calculation

- Perform single-point calculation at predicted equilibrium volume

- Confirm forces are minimal (< 0.01 eV/Ã…)

- Check stress tensor components are hydrostatic

Troubleshooting Note: If energy-volume curve shows multiple minima, increase k-point density and verify pseudopotential transferability.

Protocol 2: Band Structure and DOS Calculation Workflow

Based on: Electronic structure analysis of half-metallic ferromagnets [21]

Procedure:

- Converged Ground State

- Start from fully optimized geometry (forces < 0.01 eV/Ã…)

- Use high-density k-mesh for charge density convergence

Band Structure Calculation

- Select high-symmetry path through Brillouin zone

- Perform non-self-consistent calculation with fixed charge density

- Use at least 30-50 k-points between high-symmetry points

Density of States Calculation

- Use tetrahedron method for integration

- Employ 2× denser k-mesh than ground-state calculation

- Calculate projected DOS (PDOS) for orbital analysis

Analysis

- Identify direct/indirect band gaps from band structure

- Calculate band gap from DOS as E~g~ = E~CBM~ - E~VBM~

- Verify metallic systems show finite DOS at Fermi level

Validation Step: Compare integrated DOS with expected number of electrons - discrepancy indicates incomplete basis or k-sampling.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Computational Reagents for GGA Calculations

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Example Implementation | Critical Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Projector Augmented Wave (PAW) Pseudopotentials | Replace core electrons with effective potential [25] | VASP PAW_PBE library [25] | ENMAX (cutoff energy), valence electron configuration |

| Murnaghan Equation of State | Fitting energy-volume data for bulk properties [21] | WIEN2k, VASP lattice optimization | Equilibrium volume, bulk modulus, pressure derivative |

| Tetrahedron Method | Brillouin zone integration for DOS [21] | WIEN2k, VASP ISMEAR=-5 | Blöchl corrections for improved accuracy |

| GGA+U Framework | Corrects self-interaction error for localized electrons [21] | DFT+U in VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO | Hubbard U and J parameters |

| Conjugate Gradient Optimizer | Locates minimum energy structure [24] | Siesta MD.TypeOfRun CG | Force tolerance, step size, maximum iterations |

| Cadmium bis(isoundecanoate) | Cadmium bis(isoundecanoate) | Cadmium bis(isoundecanoate) is a chemical reagent for research use only (RUO). It is strictly for laboratory applications and not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Decyl 3-mercaptopropionate | Decyl 3-Mercaptopropionate CAS 45180-55-0 | Decyl 3-mercaptopropionate is a key chemical intermediate for research. This product is for professional lab use only and not for personal use. | Bench Chemicals |

Workflow Visualization

The Critical Importance of GGA in Materials Design and Virtual Drug Screening

In computational science, the Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) serves as a cornerstone for accurate property prediction in both materials design and drug discovery. For lattice optimization research, GGA provides enhanced accuracy over local density approximations by considering electron density gradients, enabling more reliable predictions of structural, electronic, and mechanical properties in complex systems. This technical framework supports two seemingly disparate fields: the design of advanced lattice materials with tailored mechanical properties, and the virtual screening of pharmaceutical compounds targeting specific biological receptors. In materials science, GGA functionals facilitate the prediction of elastic moduli and stability in perovskite crystals and metallic lattices [26] [4], while in drug discovery, they enable precise characterization of ligand-receptor interactions and binding affinities through structure-based virtual screening approaches [27]. This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting and methodological guidance for researchers navigating the computational challenges inherent in these advanced applications.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What specific advantages does GGA offer for lattice property predictions in metallic systems?

GGA significantly improves the accuracy of predicting elastic properties in lattice structures, especially for metallic alloys like AlSi10Mg used in additive manufacturing. Research demonstrates that GGA-driven calculations, when combined with machine learning optimization, can achieve up to 14% enhancement in mechanical properties compared to standard parameter approaches [28]. The key advantage lies in GGA's ability to better describe exchange-correlation energies in systems with rapidly changing electron densities, such as at surfaces and interfaces within complex lattice architectures.

Q2: How does GGA impact virtual screening accuracy in drug discovery pipelines?

In structure-based virtual screening (SBVS), GGA improves scoring function accuracy in molecular docking simulations by providing better descriptions of van der Waals interactions and hydrogen bonding networks [27]. This directly enhances the identification of true positive hits from compound libraries, potentially reducing false positive rates that commonly plague high-throughput screening campaigns. The improved electronic structure modeling helps prioritize compounds with higher likelihood of experimental success.

Q3: What are common convergence issues in GGA calculations for lattice optimization, and how can they be resolved?

Table: Common GGA Convergence Issues and Solutions

| Error Symptom | Probable Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| "Linear search skipped for unknown reason" [29] | Invalid Hessian matrix | Restart optimization with opt=calcFC to recalculate force constants |

| "Error imposing constraints" during restricted optimization [29] | Structural initial guesses incompatible with constraints | For QST2: Switch to TS(Berny) or QST3; For modredundant: Use smaller step sizes or modify initial geometry |

| "FormBX had a problem" / "Error in internal coordinate system" [29] | Linear atom arrangements in internal coordinates | Use opt=cartesian for initial steps, then return to default optimizer; Alternatively, re-optimize final structure |

| "Maximum iterations exceeded in RedStp" with NaN eigenvalues [29] | Frequency calculation bug | Take last optimized structure and resubmit for opt freq calculation |

Q4: How does GGA contribute to predicting stability in novel perovskite materials?

GGA functionals are crucial for Density Functional Theory (DFT) validation of newly designed perovskite materials, enabling accurate assessment of formation energies and thermodynamic stability [26]. When integrated with generative machine learning models like the Lattice-Constrained Materials Generative Model (LCMGM), GGA helps validate that generated candidates exhibit realistic lattice parameters and cohesive energies, filtering out structurally unfeasible candidates before experimental synthesis.

Q5: What role does GGA play in multi-scale lattice optimization frameworks?

In data-driven bi-directional design frameworks, GGA provides the quantum mechanical foundation for calculating base properties that inform machine learning models. These models then predict elastic moduli for complex lattice morphologies, achieving errors of less than 10% compared to finite element analysis [4]. GGA calculations thus serve as the physical basis for training data generation in multi-scale optimization workflows.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Machine Learning-Enhanced GGA Workflow for Lattice Materials

Purpose: To optimize process parameters for additive manufacturing of lattice structures using GGA-informed neural networks [28]

Workflow:

- Input Parameter Selection: Define laser power (W), scanning speed (mm/s), hatch spacing (µm), strut diameter (mm), and building angle (°)

- GGA Calculation Phase: Perform first-principles calculations to determine base material properties

- Neural Network Training: Train genetic algorithm-optimized backpropagation neural network with GGA-calculated properties as foundational inputs

- Property Prediction: Model predicts ultimate tensile strength (UTS) and elongation after fracture for lattice strut units

- Validation: Compare predicted vs. experimental mechanical performance with target of ≤10% error

Key Parameters:

- Laser mode: Continuous wave vs. pulsed laser processing

- Material: AlSi10Mg alloy system

- Target enhancement: Mechanical properties improvement over ideal parameters

Protocol: Structure-Based Virtual Screening with GGA-Optimized Geometries

Purpose: To identify potential drug candidates through molecular docking using GGA-optimized structures [27]

Workflow:

- Target Preparation: Obtain 3D structure of biological target (protein/enzyme/DNA) from PDB or homology modeling

- Ligand Library Preparation: Curate database of small molecules with calculated physicochemical descriptors (molecular weight, logP, H-bond donors/acceptors, rotatable bonds)

- Geometry Optimization: Employ GGA functionals to optimize ligand geometries and charge distributions

- Molecular Docking: Perform automated docking simulations using GGA-informed scoring functions

- Binding Affinity Prediction: Calculate binding energies and interaction patterns for top poses

- ADMET Filtering: Apply absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity filters to prioritize candidates

Validation: Experimental IC50 values for top candidates should correlate with computed binding affinities (R² > 0.7)

Virtual Screening Workflow with GGA Optimization

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for GGA-Enhanced Research

| Tool/Software | Application Domain | Key Function | GGA Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian [29] | Quantum Chemistry | Electronic structure calculations | Provides GGA functionals (e.g., BLYP, PBE) for molecular systems |

| VASP | Materials Science | Ab initio DFT simulations | Implements GGA for periodic systems and solid-state materials |

| AutoDock Vina [27] | Drug Discovery | Molecular docking | GGA-optimized force fields improve binding affinity predictions |

| pymatgen [26] | Materials Informatics | Crystal structure analysis | Processes GGA-calculated materials properties for ML training |

| Rhino7-Grasshopper [4] | Lattice Design | Parametric lattice modeling | Generates structures for GBA-based mechanical analysis |

| Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD) [26] | Materials Database | Curated materials data | Contains GGA-calculated formation energies and properties |

Advanced GGA Applications

Lattice-Constrained Generative Design

The Lattice-Constrained Materials Generative Model (LCMGM) represents a significant advancement in GGA-informed materials design, addressing the critical challenge of lattice reconstruction errors that often plague deep generative models [26]. This approach integrates GGA-validated candidate materials into a structured pipeline:

Lattice-Constrained Generative Materials Design

Key Innovation: By incorporating GGA-validated formation energies as stability constraints during the encoding phase, the LCMGM achieves improved training stability and higher geometrical conformity compared to baseline models like PGCGM and FTCP [26].

Bi-Directional Lattice Optimization Framework

The data-driven bi-directional framework enables simultaneous optimization of lattice skeleton and morphology through a sophisticated integration of GGA-informed properties and machine learning [4]:

Table: Two-Tiered ML Framework for Lattice Optimization

| Tier | Algorithm | Input Features | Target Output | GGA Integration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tier 1 | Polynomial Regression | Geometric parameters (Pâ‚,Pâ‚‚,P₃,...,Pâ‚™) | Relative Density (Ï) | GGA-calculated base material properties inform feature engineering |

| Tier 2 | Random Forest | Geometric parameters + Relative Density | Elastic Modulus (E) | Training data generated from GGA-validated homogenization methods |

Performance Metrics:

- Prediction accuracy: <10% error compared to finite element analysis

- Optimization improvement: Up to 25% enhancement in mechanical performance under identical density constraints

- Application scope: Cubic, monoclinic, orthorhombic, tetragonal, and trigonal crystal systems

Troubleshooting Complex GGA Workflows

Addressing Lattice Symmetry Breakdown

A common challenge in GGA-assisted materials design is unphysical symmetry breakdown in generated structures, particularly in perovskite systems [26]:

Problem: Generated materials exhibit low symmetry, unfeasible atomic coordination, and triclinic behavioral properties despite cubic targets.

Root Cause: Lattice reconstruction errors at the decoding phase of generative models.

Solutions:

- Implement symmetry-preserving loss functions during neural network training

- Incorporate space group affine transformative features for lattice constraint

- Apply post-generation symmetry analysis and filtering

- Utilize conventional cell representations rather than primitive cells for enhanced symmetry learning

Managing Computational Resource Constraints

GGA calculations are computationally demanding, creating bottlenecks in high-throughput screening applications:

Strategy 1 - Transfer Learning: Pre-train models on GGA data from smaller systems, then fine-tune for specific applications [4]

Strategy 2 - Multi-Fidelity Modeling: Combine high-accuracy GGA data with faster semi-empirical methods to expand training datasets

Strategy 3 - Active Learning: Iteratively select the most informative candidates for GGA calculation based on model uncertainty

Future Directions in GGA-Enhanced Research

The integration of GGA with emerging machine learning approaches continues to evolve, with several promising developments:

Hybrid Quantum Mechanics/Machine Learning (QM/ML): Deep generative models like VAEs and GANs are increasingly leveraging GGA-calculated properties as conditioning inputs, enabling exploration of chemically realistic materials spaces [26] [4].

Multi-Objective Optimization: Advanced genetic algorithms are being coupled with GGA-informed surrogate models to simultaneously optimize multiple target properties across materials and pharmaceutical domains.

Dynamic Workflow Orchestration: Next-generation research platforms are automating the interplay between GGA calculations and ML-guided candidate selection, significantly accelerating discovery cycles in both materials design and drug development.

Implementing GGA for Lattice Optimization: Methods and Real-World Applications

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Pseudopotentials and Basis Sets

Q1: What is the difference between pseudopotentials and all-electron approaches? Pseudopotentials approximate inner core electrons to reduce computational cost, freezing them at their optimized atomic configuration. In contrast, all-electron approaches explicitly treat all electrons in the system. The frozen core approximation generally has minimal impact on equilibrium geometries and valence electron properties but is typically insufficient for spectroscopic properties involving core electrons, which require all-electron methods [30].

Q2: Can Gaussian-type basis functions be used in all DFT codes? No. The choice of basis functions is code-dependent. For instance, the ADF code uses Slater-Type Orbitals (STOs), which provide more accurate behavior near the nucleus and at long range compared to Gaussian-type orbitals (GTOs). Consequently, fewer STOs are typically needed to achieve a given accuracy level [30]. Other codes, however, are designed to use GTOs.

Q3: Which basis set should I select for my GGA calculation? For geometry optimizations with GGA functionals, the Double Zeta plus single Polarization (DZP) basis set is a robust starting point. For more accurate spectroscopic properties, the Triple Zeta plus two Polarization (TZ2P) basis is recommended. If available, using frozen core basis sets is generally acceptable with GGA functionals [30]. The table below summarizes these recommendations.

Table 1: Basis Set Recommendations for GGA Calculations

| Basis Set | Description | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| DZP | Double Zeta + 1 Polarization function | Geometry optimization; good starting point [30] |

| TZ2P | Triple Zeta + 2 Polarization functions | Accurate spectroscopic properties [30] |

| QZ4P | Quadruple Zeta + 4 Polarization functions | Highest accuracy, near basis-set limit [30] |

| AUG | Includes diffuse functions | Anions and diffuse excitations [30] |

Self-Consistent Field (SCF) Convergence

Q4: My SCF calculation will not converge. What steps can I take? SCF convergence issues are common. The following systematic troubleshooting steps are recommended:

- Adjust Mixing Parameters: Decrease the mixing parameter

Electrons%mixing_betato stabilize the iterative process [31]. - Improve Initial Density Guess: For device calculations, using the

EquivalentBulkmethod to generate the initial electron density can provide a better starting point than the defaultNeutralAtommethod [32]. - Increase Electron Temperature: Raising the electron temperature (smearing) helps manage oscillations near the Fermi level, particularly in metals and small-gap semiconductors [32].

- Verify Numerical Parameters: Ensure the k-point sampling and plane-wave energy cutoff (

ecutwfc) are sufficiently converged. Inaccurate settings can lead to unphysical results that prevent convergence [32].

Q5: How do I systematically converge key numerical parameters like the plane-wave energy cutoff? Convergence testing is a critical step. A standard protocol, as demonstrated by the DREAMS framework for lattice constant calculations, involves a two-step process [33]:

- Converge

ecutwfc: Perform a series of single-point energy calculations with increasing values of the plane-wave energy cutoff while keeping the k-point mesh fixed. The energy is considered converged when the change per atom falls below a threshold (e.g., 1 meV/atom). - Converge k-points: Using the converged

ecutwfcvalue, perform another series of calculations with increasingly dense k-point meshes until the energy per atom again meets the convergence criterion.

Lattice Optimization and Properties

Q6: What is a standard workflow for a lattice optimization study using GGA? A robust lattice optimization workflow integrates DFT calculations with validation steps. The diagram below outlines this process, synthesizing protocols from multiple sources [34] [35] [33].

Q7: How does strain affect the electronic properties of perovskite materials? Applying strain by modifying lattice constants can significantly tune electronic properties. Research on APbBr₃ (A = K, Rb, Cs) perovskites shows that isotropic strain (changing all lattice vectors equally) and anisotropic strain (changing only one axis) can induce electronic phase transitions. Critical points, such as transitions to topological insulators, n-type semiconductors, and conductors, have been observed at specific strain levels, for example, around a 10% change in lattice constant [35]. The table below quantifies bandgap changes under strain for CsPbBr₃.

Table 2: Effect of Strain on CsPbBr₃ Perovskite Band Gap (GGA-PBE Calculations) [35]

| Strain Type | Strain Magnitude | Resulting Band Gap (eV) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimized Structure | 0% | 1.78 | Reference value [35] |

| Anisotropic (c-axis) | -15% | 1.62 | Band gap reduction [35] |

| Anisotropic (c-axis) | +15% | 1.90 | Band gap increase [35] |

| Isotropic | +10% | ~0 (Closing) | Transition to metallic state [35] |

Software and Tools

Q8: What tools can help non-specialists perform complex DFT workflows? Several platforms are designed to lower the barrier for performing automated, reproducible DFT calculations.

- AiiDAlab QE App: A web-based platform with a graphical interface that guides users through predefined computational protocols for properties like band structures, phonons, and spectroscopy using Quantum ESPRESSO. It automates input setup, execution, and result visualization [36].

- DREAMS Framework: A multi-agent system that uses large language models (LLMs) to autonomously plan and execute DFT studies, including structure generation, parameter convergence, and error handling. It has achieved expert-level accuracy in tasks like lattice constant prediction [33].

Q9: Are there automated methods for handling complex DFT errors? Yes. Advanced frameworks like DREAMS incorporate a dedicated convergence error-handling agent. This agent can diagnose common DFT errors (e.g., SCF convergence failure, symmetry-related issues) and dynamically adjust calculation parameters, such as the mixing beta or smearing, to resolve them, significantly reducing the need for manual intervention [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Their Functions in Lattice Optimization Research

| Tool / 'Reagent' | Function in Computational Experiment |

|---|---|

| Pseudopotential Libraries | Provide a description of core electrons and ion potentials, crucial for accuracy and efficiency (e.g., GGA-PBE consistent pseudopotentials) [35]. |

| Plane-Wave Basis Set | The set of functions used to expand the wavefunctions; its quality is controlled by the ecutwfc (energy cutoff) parameter [33]. |

| k-point Mesh | A grid for sampling the Brillouin Zone; essential for accurate numerical integration over electronic states [35]. |

| Exchange-Correlation Functional (GGA-PBE) | A specific approximation to the quantum mechanical exchange-correlation energy; defines the physical model in the DFT calculation [37] [35]. |

| Machine Learning Models (GBDT) | Used to rapidly predict material properties (e.g., lattice constant, substitution energy) from elemental features, accelerating screening [34]. |

| Workflow Management Systems (AiiDA) | Automate, manage, and ensure the provenance of complex, multi-step computational workflows [36]. |

| Tiomolibdic acid | Tiomolibdic acid, CAS:13818-85-4, MF:H2MoS4, MW:226.2 g/mol |

| Nepetidone | Nepetidone, CAS:104104-55-4, MF:C29H48O4, MW:460.7 g/mol |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: Why does my DFT calculation for a zinc-blende ternary alloy (e.g., BGaN or AlGaN) predict a band gap that is smaller than the expected experimental value?

- Answer: This is a common occurrence when using standard Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) functionals, such as PBE. GGA tends to underestimate band gaps due to the self-interaction error and inadequate description of the electronic exchange and correlation energies [38] [39] [40]. This error does not necessarily invalidate your calculation but should be accounted for when interpreting results.

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Confirm the Trend: GGA is often reliable for predicting trends in properties, such as how the band gap changes with alloy composition (e.g., in B(x)Ga({1-x})N or Al(x)Ga({1-x})N) [38]. Focus on the relative changes.

- Apply a Scissors Operator: For optical property calculations, you can apply a semi-empirical "scissors operator" to rigidly shift the conduction bands to align the fundamental band gap with experimental values before calculating properties like the dielectric function [40].

- Consider Hybrid Functionals: For more accurate absolute band gap values, use hybrid functionals (e.g., HSE06), which mix a portion of exact Hartree-Fock exchange with the GGA exchange. Be aware that this significantly increases computational cost [34].

FAQ 2: My lattice parameter optimization for a doped metal oxide (e.g., M:TiO(_2)) is not converging, or the results seem unphysical. What could be wrong?

- Answer: Convergence issues can stem from several sources, including insufficient k-point sampling, an insufficiently high plane-wave kinetic energy cutoff, or an inadequate force convergence criterion.

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Check k-points: Ensure you are using a sufficiently dense k-point mesh. A common baseline is a mesh of 1000 k-points per reciprocal atom, but this should be tested for convergence for your specific system [41].

- Increase Cutoff Energy: The plane-wave basis set must be truncated. Use a cutoff energy of at least 520 eV, and systematically increase it to ensure your total energy is converged to within a target tolerance (e.g., 1-5 meV/atom) [41].

- Tighten Convergence Criteria: For reliable ionic relaxation, set a strict energy difference criterion (e.g., (1 \times 10^{-8}) eV/atom) and a force convergence criterion (e.g., below 0.01 eV/Ã…) [34] [37].

FAQ 3: How can I efficiently screen multiple dopant elements in a host material (like TiO(_2)) for lattice parameter and stability without performing dozens of full DFT calculations?

- Answer: For high-throughput screening, you can combine a limited set of DFT calculations with machine learning (ML) models.

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Create a DFT Database: First, perform full DFT calculations for a small, chemically diverse set of dopants to compute key properties like lattice constants and substitution energies ((Es)) [34].

- Train an ML Model: Use these results to train a machine learning model. The Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT) algorithm has shown high accuracy in predicting lattice constants (RMSE ~0.032 Ã…) and substitution energies for doped TiO(2) [34].

- Screen and Validate: Use the trained ML model to predict properties for a much larger set of potential dopants, then validate the most promising candidates with a full DFT calculation.

Experimental and Computational Protocols

Protocol: First-Principles Calculation of Zinc-Blende Alloy Properties

This protocol outlines the methodology for investigating structural, electronic, and optical properties of zinc-blende ternary alloys like B(x)Ga({1-x})N and Al(x)Ga({1-x})N, as employed in foundational GGA studies [38].

1. System Setup:

- Code: Use a plane-wave DFT code such as Abinit [38] or VASP [37].

- Functional: Select the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) formulation of the GGA [38] [39] [37].

- Pseudopotentials: Employ Projector Augmented-Wave (PAW) or norm-conserving pseudopotentials. For example, use the following valence electron configurations [38]:

- B: (2s^2 2p^1)

- Ga: (3d^{10} 4s^2 4p^1)

- Al: (3s^2 3p^1)

- N: (2s^2 2p^3)

2. Convergence Tests:

- Plane-Wave Cutoff: Converge the total energy with respect to the kinetic energy cutoff. A typical starting point is 60 Ha (~816 eV) [38], but 520 eV is also a common standard [41].

- k-point Sampling: Use a (\Gamma)-centered Monkhorst-Pack k-point mesh. A density of 1000 k-points per reciprocal atom is a robust baseline, but a mesh of at least (7\times7\times4) for a unit cell has been used for similar systems [41] [40].

3. Calculation Workflow:

- Geometry Optimization: Fully relax the atomic positions and lattice vectors until the forces on all atoms are below a threshold of 0.005 eV/Ã… and the stress is below 0.05 GPa [38] [40].

- Self-Consistent Field (SCF): Perform an SCF calculation on the optimized structure with a tight energy convergence criterion (e.g., (2\times10^{-6}) eV/atom) [38] [40].

- Property Calculation:

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the diagram below.

Protocol: Synthesis and Characterization of Zn-Alloyed Perovskite NCs

This protocol describes the experimental synthesis and analysis of lead-reduced CsZn(x)Pb({1-x})X(_3) nanocrystals (NCs) for optoelectronic applications [42].

1. Synthesis of CsZn(x)Pb({1-x})X(_3) NCs:

- Method: Hot-injection method to control nucleation and growth.

- Precursors: Cesium precursor (e.g., Cs(2)CO(3)), lead precursor (e.g., PbX(2)), and zinc precursor (e.g., ZnX(2), where X = Cl, Br, I).

- Ligands: Use oleic acid and oleylamine as surface ligands to control growth and provide colloidal stability.

- Procedure: Inject the cesium precursor into a hot solution of the lead and zinc precursors in solvents like 1-octadecene. Quench the reaction after a specific time (seconds to minutes) to control NC size.

2. Structural and Morphological Characterization:

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD):

- Purpose: Confirm crystal structure (cubic perovskite) and observe lattice contraction due to Zn(^{2+}) alloying.

- Expected Result: A shift of diffraction peaks (e.g., the (200) plane) to higher 2θ angles with increasing Zn(^{2+}) content, indicating a smaller lattice parameter [42].

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM):

- Purpose: Analyze the size, size distribution, and morphology of the NCs.

- Expected Result: Monodisperse, cubic-shaped NCs, with no significant change in morphology upon Zn(^{2+}) alloying.

3. Optical Characterization:

- Photoluminescence (PL) Spectroscopy:

- Purpose: Measure the emission wavelength and quality.

- Expected Result: A blue-shift in the PL emission peak with higher Zn(^{2+}) concentration, due to lattice contraction and band gap increase, while maintaining a high Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) [42].

- UV-Vis Absorption Spectroscopy:

- Purpose: Determine the band gap of the NCs.

- Expected Result: The absorption onset and Tauc plot analysis will show an increase in the band gap with increasing Zn(^{2+}) content.

Data Presentation

Key Properties of Zinc-Blende Binary Compounds from GGA Calculations

The following table summarizes the typical results for the binary compounds that form the endpoints of B(x)Ga({1-x})N and Al(x)Ga({1-x})N ternary alloys, as obtained from well-converged GGA calculations [38].

Table 1: Calculated Structural and Electronic Properties of Zinc-Blende Binary Nitrides

| Compound | Lattice Constant (Ã…) | Bulk Modulus (GPa) | Band Gap (eV) | Band Gap Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BN | ~3.60 | ~400 | ~4.9 (Indirect) | Indirect [38] |

| AlN | ~4.38 | ~192 | ~4.3 (Indirect) | Indirect [38] |

| GaN | ~4.50 | ~172 | ~1.8 (Direct) | Direct [38] [40] |

Note: The band gap values are typical GGA predictions and are known to be underestimated compared to experiment.

Effect of Zn²⺠Alloying on Perovskite NC Properties

The table below quantifies the observed changes in key properties of CsPbBr(_3) NCs upon alloying with Zn(^{2+}), as determined experimentally [42].

Table 2: Experimental Trends in CsZn(x)Pb({1-x})Br(_3) Nanocrystal Properties

| Zn²⺠Content (x) | Lattice Parameter | PL Emission Wavelength | Band Gap (Eg) | PL Quantum Yield (PLQY) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0% (Pure CsPbBr(_3)) | a₀ | λ₀ | Eg₀ | >80% |

| 15% | Decreases | Blue-shifts | Increases | Maintained >80% |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Materials for Zinc-Blende Alloy DFT Studies and Zn-Alloyed Perovskite Synthesis

| Category | Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|---|

| Computational (DFT) | DFT Software (Abinit, VASP, CASTEP) | Performs the core quantum mechanical calculations to solve for electronic structure and total energy [38] [40] [37]. |

| GGA-PBE Functional | The exchange-correlation functional that determines how electron interactions are approximated; widely used for structural properties [38] [39] [37]. | |

| Pseudopotentials (PAW) | Represents the core electrons and nucleus, reducing the number of electrons explicitly calculated, thus saving computational cost [38] [41]. | |

| Experimental (Perovskite NCs) | Lead Halide (PbX₂) | The primary B-site cation source in the ABX₃ perovskite structure [42]. |

| Zinc Halide (ZnXâ‚‚) | The dopant precursor used to partially replace Pb²âº, reducing toxicity and tuning optical properties [42]. | |

| Cesium Carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) | The cesium (A-site) precursor for all-inorganic perovskite NCs [42]. | |

| Oleic Acid & Oleylamine | Surface ligands that control NC growth during synthesis and provide colloidal stability in non-polar solvents [42]. | |

| 1-Octadecene | A high-boiling-point, non-coordinating solvent used as the reaction medium for NC synthesis [42]. | |

| Iothalamic Acid I-125 | Iothalamic Acid I-125, CAS:97914-42-6, MF:C11H9I3N2O4, MW:607.91 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Zileuton, (R)- | Zileuton, (R)-, CAS:142606-21-1, MF:C11H12N2O2S, MW:236.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Structure-based virtual screening (SBVS) is a computational technique that has become essential in early-stage drug discovery for identifying novel lead compounds. SBVS utilizes the three-dimensional structure of a biological target to efficiently discover potential drug candidates, offering a more cost-effective and faster alternative to traditional high-throughput screening (HTS). The method aims to understand the molecular basis of disease by leveraging atomic-level details of ligand-target interactions [43].

The success of SBVS depends on accurate predictions of binding poses and affinities between small molecules and their protein targets. With advances in computational power and methodology, SBVS can now screen ultra-large chemical libraries containing billions of compounds, significantly expanding the explorable chemical space for drug discovery [44]. When properly implemented, SBVS can achieve hit rates significantly greater than conventional HTS, making it a valuable tool for pharmaceutical research [43].

Key Concepts and Terminology

Virtual Screening (VS): The computational process of screening libraries of small molecules to identify those most likely to bind to a drug target. SBVS specifically uses the 3D structural information of the target [43].

Druggability: The likelihood that a target can be effectively modulated by a small molecule drug, determined by factors like binding site properties and ligand affinity [43].

Docking: The computational method that predicts the preferred orientation of a small molecule (ligand) when bound to its target [43].

Scoring Function: A mathematical algorithm used to evaluate and rank the binding affinity between a ligand and target based on their predicted interaction [43] [45].

Lead Optimization: The process of progressively improving the pharmacological properties and potency of initial hit compounds [43].

SBVS Workflow and Methodology

Standard SBVS Protocol

The typical SBVS workflow consists of several sequential steps, each critical to the success of the screening campaign [43]:

Target Selection and Preparation: A therapeutically relevant protein target is selected, and its 3D structure is obtained through experimental methods (X-ray crystallography, NMR) or computational modeling [43].

Compound Library Preparation: Libraries of commercially available or synthesizable compounds are processed to assign proper tautomeric, stereoisomeric, and protonation states [43] [45].

Molecular Docking: Each compound in the library is computationally docked into the target's binding site to predict binding poses [43].

Scoring and Ranking: Docked compounds are evaluated using scoring functions and ranked based on predicted binding affinity [43] [45].

Post-processing and Selection: Top-ranked compounds undergo further analysis considering factors like chemical diversity, drug-likeness, and synthetic feasibility before experimental testing [43].

Workflow Visualization

Common Challenges and Troubleshooting Guide

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why do my docking results show poor enrichment of active compounds?

A: Poor enrichment often stems from inadequate consideration of target flexibility or suboptimal scoring function selection. Implement ensemble docking using multiple target conformations to account for protein flexibility. Consider using consensus scoring across multiple scoring functions or target-biased scoring functions optimized for specific protein classes [45] [44].

Q2: How can I improve the accuracy of binding affinity predictions?

A: Enhance accuracy by incorporating environmental factors like metal ions and water molecules in the binding site. For metalloproteins, specialized scoring terms that accurately describe metal-ligand interactions can double the success rate of correct pose prediction. Post-docking optimization with molecular dynamics simulations can further refine binding predictions [45].

Q3: What are the common causes of failed docking calculations?

A: Failed docking often results from improper protonation states of binding site residues, incorrect assignment of bond orders in co-crystallized ligands, or inadequate treatment of water-mediated ligand interactions. Use comprehensive protein preparation tools that optimize hydrogen bonding networks and assign proper ionization states [43].

Q4: How can I enhance the selectivity of discovered inhibitors?

A: To enhance selectivity, employ structure-based pharmacophore models that capture unique structural features of your target compared to related proteins. Shape-based clustering of binding sites across protein families can help design selective screening protocols. Additionally, consider dynamic pharmacophore models that incorporate protein flexibility [43].

Troubleshooting Common Technical Issues

Table 1: Common SBVS Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low hit rate in experimental validation | Poor library quality, inadequate target preparation, insufficient consideration of flexibility | Apply drug-like filters (Rule of 5), use focused libraries, employ ensemble docking, incorporate pharmacophore constraints [43] [45] |

| Inaccurate binding pose prediction | Limited sampling, inadequate scoring function, improper protonation states | Increase docking simulations, use consensus scoring, validate protonation states of binding site residues [43] [44] |

| Long computational times | Large library size, inefficient docking parameters, insufficient computational resources | Implement library pre-filtering, use hierarchical screening protocols, leverage GPU acceleration, apply active learning techniques [44] |

| Failure to account for key interactions | Neglected water-mediated interactions, improper treatment of metal ions | Use explicit water models, implement specialized potentials for metal coordination, analyze hydration sites [43] [45] |

Advanced Methodologies and Recent Advances

Accounting for Target Flexibility

Traditional rigid receptor docking often fails to accurately model the induced-fit phenomena upon ligand binding. Advanced methods to address target flexibility include:

- Ensemble Docking: Using multiple receptor conformations from crystallographic structures, molecular dynamics simulations, or normal mode analysis [45].

- 4D Docking: Incorporating multiple target conformers into a single docking simulation by merging 3D grids from optimally superimposed structures [45].

- Side-Chain Flexibility: Allowing flexibility of binding site side chains while keeping the backbone fixed during docking [44].

- Complete Flexible Docking: Implementing full receptor flexibility including limited backbone movement, as enabled by methods like RosettaVSH [44].

AI-Accelerated Virtual Screening

Recent advances integrate artificial intelligence with traditional physics-based methods to enhance screening efficiency and accuracy:

- Active Learning: Using neural networks trained during docking computations to intelligently select promising compounds for expensive docking calculations [44].