Inorganic Crystal Structure Determination by X-ray Diffraction: From Foundational Principles to AI-Driven Advances

This article provides a comprehensive overview of inorganic crystal structure determination using X-ray diffraction, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Inorganic Crystal Structure Determination by X-ray Diffraction: From Foundational Principles to AI-Driven Advances

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of inorganic crystal structure determination using X-ray diffraction, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of crystallography, details both traditional and cutting-edge methodologies like the AI-powered PXRDGen and XDXD models, and addresses key challenges such as peak overlap and light atom localization. The content also covers critical validation protocols to ensure structural accuracy and compares different analytical techniques. By synthesizing the latest advancements, this guide serves as a vital resource for accelerating materials discovery and innovation in biomedical research.

The Bedrock of Crystallography: Core Principles of Inorganic Structure Analysis

Bragg's Law and the Fundamentals of X-ray Diffraction

Core Principles and Theoretical Foundation

X-ray Diffraction (XRD) is a powerful non-destructive analytical technique that provides unparalleled insights into the atomic and molecular structure of crystalline materials [1]. The technique relies on the fundamental principle that when a monochromatic X-ray beam interacts with a crystalline material, it is diffracted by the periodic lattice of atoms in specific, predictable directions [2]. This phenomenon occurs because the wavelength of X-rays (approximately 0.1-10 nm) is comparable to the spacing between atoms in crystal structures, allowing them to interact constructively with the atomic planes [1].

Bragg's Law: The Cornerstone of XRD

The entire framework of XRD analysis is built upon Bragg's Law, formulated in 1913 by Sir William Henry Bragg and his son Sir William Lawrence Bragg, who later received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1915 for this foundational work [2]. Bragg's Law mathematically describes the condition under which constructive interference of X-rays occurs when they interact with parallel crystal planes [1] [3].

The law is expressed by the equation: nλ = 2d sinθ [1]

Where:

- n = order of diffraction (an integer: 1, 2, 3...)

- λ = wavelength of the incident X-ray beam (typically 1.5418 Å for copper Kα radiation)

- d = interplanar spacing (the perpendicular distance between parallel crystal planes)

- θ = Bragg angle (the angle between the incident X-ray beam and the crystal plane)

This relationship establishes that diffraction occurs only when the path difference between X-rays scattered from parallel crystal planes equals an integer multiple of the X-ray wavelength [1]. Each set of planes, characterized by their Miller indices (hkl), will produce a diffraction peak at a specific angle 2θ where this condition is satisfied [1].

XRD Instrumentation and Experimental Methodology

The X-Ray Diffractometer

A modern X-ray diffractometer consists of several essential components that work in coordination to measure diffraction patterns [1] [2]:

- X-ray Source: Generates monochromatic X-rays through electron bombardment of a metal target, most commonly copper (Cu Kα, λ = 1.5418 Å) or molybdenum (Mo Kα, λ = 0.71 Å) [1].

- Incident Beam Optics: Conditions the X-ray beam using Soller slits for controlling beam divergence, monochromators for wavelength selection, and focusing mirrors for beam concentration [1].

- Sample Stage: Holds the specimen and allows precise positioning and rotation during measurement, providing accurate angular positioning potentially with environmental controls [1].

- Detector System: Records the diffracted radiation using position-sensitive detectors (PSDs) or area detectors that simultaneously collect data over a range of angles [1] [4].

- Goniometer: A precision mechanical system controlling angular relationships between X-ray source, sample, and detector with angular accuracy better than 0.001° [1].

The instrument operates by directing X-rays at the sample while rotating both sample and detector according to θ-2θ geometry, ensuring the detector captures diffracted beams at the correct angle for constructive interference [1].

Experimental Workflow for XRD Analysis

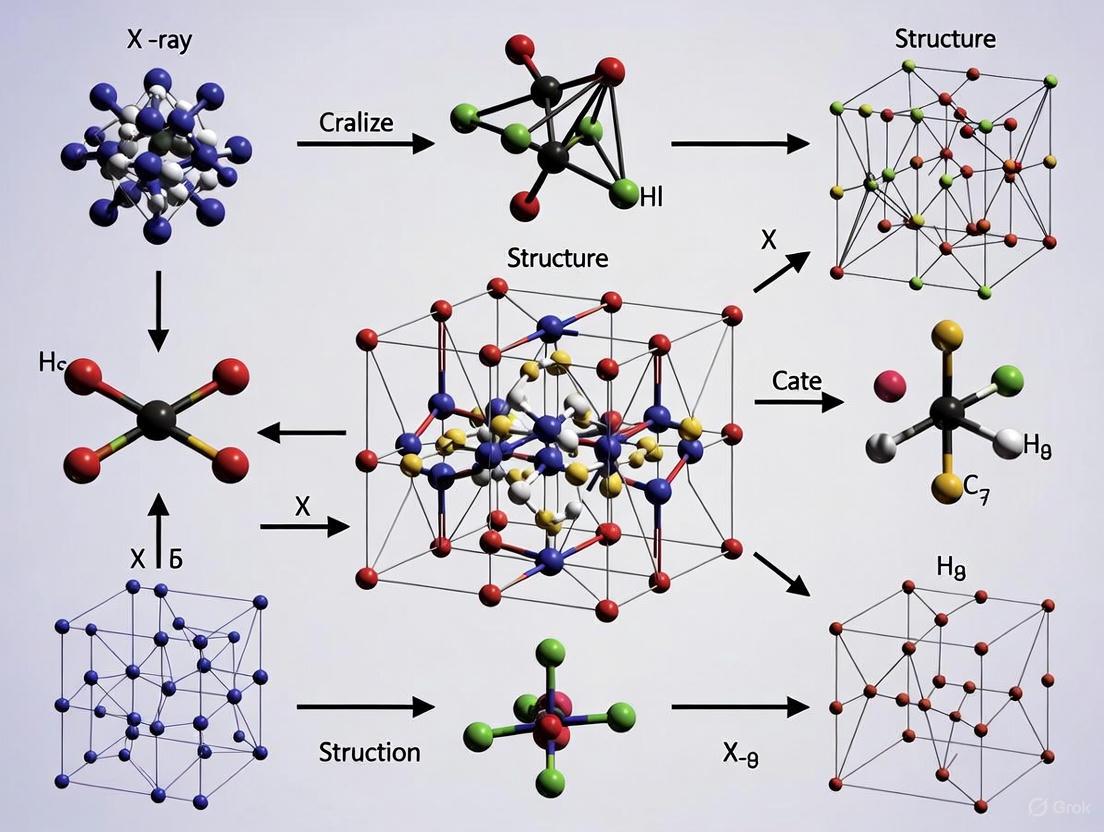

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for XRD analysis from sample preparation to data interpretation:

XRD Experimental Workflow

Sample Preparation Protocol

For powder XRD analysis, the sample must be finely ground to a homogeneous powder (typically <10 μm particle size) to ensure a random orientation of crystallites [1]. The powder is then mounted on a glass slide or in a capillary, with care taken to create a flat, uniform surface to minimize preferred orientation effects that can alter relative peak intensities [1].

Data Collection Parameters

Standard data collection parameters for routine phase analysis include [4]:

- Angular Range: 5-80° 2θ for most applications

- Step Size: 0.01-0.02° 2θ

- Counting Time: 0.5-2 seconds per step

- X-ray Source: Cu Kα radiation at 40 kV and 40 mA

For specialized applications like retained austenite quantification or residual stress measurement, specific standardized protocols must be followed according to international standards such as ASTM E915 and EN UNI 15305 [2].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for XRD Analysis

| Item | Function | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| X-ray Tubes | Generate monochromatic X-rays | Copper (Cu Kα, λ=1.5418 Å) for most applications; Molybdenum for heavy elements [1] |

| Sample Holders | Mount powdered specimens | Glass slides for flat plate; Capillaries for random orientation [1] |

| Certified Reference Materials | Instrument calibration and quantification | NIST standards for peak position and intensity calibration [2] |

| Single Crystal Substrates | Mount single crystal samples | Micromount loops and capillaries [1] |

| Incident Beam Optics | Condition X-ray beam | Soller slits, monochromators, focusing mirrors [1] |

XRD Data Interpretation and Analysis

Understanding XRD Patterns

An XRD pattern displays diffraction intensity versus diffraction angle (2θ), where each peak corresponds to a specific set of parallel crystal planes characterized by Miller indices (hkl) [1]. The diffraction pattern serves as a unique fingerprint for each crystalline phase, enabling identification and quantitative analysis [1].

The key characteristics of XRD patterns provide comprehensive structural information [1]:

- Peak Position: Determined by the angular position that directly relates to d-spacing through Bragg's law; used to determine lattice parameters and identify phases.

- Peak Intensity: The height or integrated area indicates the atomic arrangement within the crystal structure and relative abundance of different phases.

- Peak Width: Reveals crystal quality, including crystallite size and microstrain effects; narrow peaks indicate large, well-formed crystals.

- Peak Shape: Provides insights into crystal defects, stacking faults, and other structural imperfections.

Phase Identification and Quantitative Analysis

Phase identification is performed by comparing the measured diffraction pattern with reference patterns in international databases such as the Powder Diffraction File (PDF-2) or the Crystallography Open Database (COD) [2]. Modern analysis software automates this comparison process for rapid and precise phase identification [2].

For quantitative phase analysis, several methodologies are employed:

- Reference Intensity Ratio (RIR) Method: Uses known intensity ratios between phases for quantification.

- Rietveld Refinement: A full-pattern fitting method that provides the most accurate quantitative results by refining structural parameters against the entire diffraction pattern [4].

Table 2: Key Applications of Bragg's Law in XRD Analysis

| Application | Methodology | Information Obtained |

|---|---|---|

| Phase Identification | Matching d-spacings and intensities to reference patterns | Crystalline phases present in the sample [3] |

| Lattice Parameter Determination | Precise measurement of peak positions | Unit cell dimensions and crystal system [1] |

| Crystallite Size Analysis | Analysis of peak broadening using Scherrer equation | Average crystallite size and size distribution [2] |

| Residual Stress Measurement | Tracking d-spacing changes under stress | Strain and residual stress in materials [1] |

| Thin Film Characterization | Grazing Incidence XRD (GIXRD) | Crystal orientation, internal stress, and coating quality [2] |

Advanced Applications in Inorganic Crystal Structure Determination

Residual Stress and Strain Analysis

Residual stress analysis is essential to ensure the reliability of mechanical components, steel structures, and materials subjected to welding, heat treatment, or plastic deformation [2]. XRD enables non-destructive measurement of these stresses by comparing lattice spacing variations with those of a stress-free reference [2]. This application is particularly valuable in metallurgy and materials engineering for assessing component lifetime and performance.

The relationship between strain and diffraction peak shift is derived from Bragg's law:

ε = (d - d₀)/d₀ = -cotθ × (θ - θ₀)

Where ε is the strain, d is the strained lattice spacing, d₀ is the unstrained lattice spacing, θ is the diffraction angle for the strained material, and θ₀ is the diffraction angle for the unstrained reference material.

Retained Austenite Analysis in Steels

Retained austenite is a metastable phase that can persist in steels after heat or mechanical treatment, significantly affecting properties such as hardness, fatigue strength, and dimensional stability [2]. XRD is the reference technique for quantifying retained austenite, distinguishing martensitic, ferritic, and austenitic phases with high precision [2]. This application is critical in steel production and heat treatment validation.

Thin Film and Coating Characterization

Using techniques like Grazing Incidence XRD (GIXRD), it is possible to characterize coatings and thin films with nanometric precision [2]. The analysis reveals information on crystal orientation, internal stress, and coating quality, which is essential for advanced materials development in electronics and functional coatings [2].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships in XRD structural determination and its connection to material properties:

XRD Structural Determination Logic

In-situ and Operando XRD Studies

Modern XRD instrumentation enables in-situ and operando studies of materials under non-ambient conditions, including high and low temperatures, controlled atmospheres, and under applied stress [4]. These advanced applications allow researchers to monitor phase transitions and structural changes in real-time, providing crucial insights into material behavior under realistic operating conditions.

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

XRD technology is undergoing rapid evolution, driven by the demand for compact, automated, and intelligent instruments [2]. According to market analysis, the global XRD market is expected to exceed $1 billion by 2033, driven by miniaturization, automation, and AI-powered software solutions [2].

Key innovations shaping the future of XRD include:

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: AI approaches are achieving over 90% accuracy in determining crystal phases and space groups from XRD data, eliminating the need for manual tuning [3]. Machine learning algorithms are also being applied to predict crystal size and microstrain from XRD data using Gaussian peak shape analysis [3].

Advanced Detector Technology: Two-dimensional detectors enable quick collection of low-noise data, facilitating in-situ analysis of structural variations including phase transitions [3].

Laboratory-based 3D Micro-beam XRD: Recent research introduces the Lab-3DμXRD method, enabling three-dimensional, non-destructive material characterization directly in laboratory environments [2].

Integrated Workflows: The combination of robotics and AI-driven workflows are shaping the next generation of diffractometry—faster, smarter, and more accessible than ever before [2].

These technological advances continue to expand the applications of Bragg's Law and XRD analysis across scientific disciplines, from fundamental materials research to industrial quality control and pharmaceutical development. As instrumentation becomes more sophisticated and accessible, XRD remains an indispensable tool for inorganic crystal structure determination in research and industrial applications alike.

Understanding Unit Cells, Lattice Parameters, and Space Groups

The determination of inorganic crystal structures via X-ray diffraction research relies upon three foundational pillars: the unit cell, lattice parameters, and space groups. These concepts form the essential language through which the long-range periodic order of crystalline materials is described and quantified. The unit cell represents the simplest repeating volume that fully captures the crystal's symmetry and, when translated in three dimensions, generates the entire crystal lattice [5]. This fundamental building block is defined by its lattice parameters—the three edge lengths (a, b, c) and three interaxial angles (α, β, γ) that collectively specify its size and shape [6]. The specific values and relationships between these parameters determine the crystal system to which a material belongs, of which there are seven fundamental types [6].

The third critical component, space groups, provides a complete description of the crystal's internal symmetry by combining the translational symmetry of the Bravais lattice with the point group symmetry of atomic arrangements, along with possible screw axes and glide planes [7]. There exist exactly 230 three-dimensional space groups in classical crystallography, each defined by a specific set of symmetry operations [7]. The Hermann-Maguin notation system uses four symbols to uniquely specify each space group, beginning with a letter (P, I, R, F, A, B, or C) representing the Bravais lattice type, followed by symbols denoting the point group symmetries [7]. For inorganic crystal structure determination, precise understanding of the interrelationship between these three concepts is paramount, as the space group directly dictates the unique crystallographic positions within the unit cell and the resulting X-ray diffraction pattern [7].

Quantitative Framework of Crystal Systems

The classification of crystals into seven systems is governed by the specific relationships between their lattice parameters and angles, which directly correspond to increasing levels of symmetry. This systematic categorization enables researchers to quickly narrow down possible structures when analyzing X-ray diffraction data. The following table summarizes the defining characteristics of each crystal system:

Table 1: The Seven Crystal Systems and Their Defining Lattice Parameter Relationships

| Crystal System | Lattice Parameter Relationships | Angle Relationships | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triclinic | a ≠b ≠c | α ≠β ≠γ ≠90° | K₂S₂O₈ |

| Monoclinic | a ≠b ≠c | α = γ = 90° ≠β | β-Sulfur, Selenium |

| Orthorhombic | a ≠b ≠c | α = β = γ = 90° | α-Sulfur, Iodine |

| Tetragonal | a = b ≠c | α = β = γ = 90° | White Tin, Zircon |

| Trigonal | a = b = c | α = β = γ ≠90° | Calcite, Cinnabar |

| Hexagonal | a = b ≠c | α = β = 90°, γ = 120° | Graphite, Zinc |

| Cubic | a = b = c | α = β = γ = 90° | Diamond, NaCl, Cu |

For commonly encountered crystal structures, specific shorthand designations are often used. For instance, face-centered cubic (fcc) crystals like copper and aluminium belong to space group F M 3 M, while body-centered cubic (bcc) materials like iron and tungsten fall under space group I M 3 M [8] [7]. The hexagonal close-packed (hcp) structure, observed in magnesium and zinc, corresponds to space group P 6₃/M M C [7]. These conventions streamline communication among crystallographers and materials scientists.

Experimental Protocols for Crystal Structure Determination

Protein Crystallization and Sample Preparation

The process of determining biological macromolecule structures begins with protein crystallization, widely considered the rate-limiting step in most protein crystallographic work [6]. A reliable source of pure, homogeneous, and soluble protein is prerequisite, with typical protein concentrations ranging from 5 to 20 mg/mL. The crystallization process employs vapor diffusion methods (sitting drop or hanging drop) where 1-2 μL of protein solution is mixed with an equal volume of precipitant solution and equilibrated against a reservoir containing 500-1000 μL of precipitant solution [6]. Commercial sparse matrix screens systematically vary key parameters including precipitant type and concentration (e.g., polyethylene glycol, ammonium sulfate), buffer identity and pH, temperature, and additives. Successful crystallization typically yields crystals with minimum dimensions of 0.1 mm to provide sufficient crystal lattice volume for X-ray exposure [6]. Before data collection, crystals must be verified to contain the target macromolecule rather than precipitant salts through techniques such as polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis or test X-ray diffraction exposure.

X-Ray Diffraction Data Collection

Once suitable crystals are obtained and mounted on a goniometer head, X-ray diffraction data collection proceeds with the following protocol. The X-ray source can be either a laboratory-scale generator (producing characteristic copper Kα radiation at λ = 1.5418 Å) or a synchrotron beamline providing tunable, intense X-ray beams [6]. The crystal-to-detector distance is calibrated to capture diffraction spots up to the desired resolution, typically 1.5-3.0 Å for initial characterization, with higher resolution required for atomic-level detail (carbon-carbon bonds are approximately 1.5 Å) [6]. Modern data collection employs charge-coupled device (CCD) detectors or hybrid pixel array detectors that offer rapid readout times (seconds) and high sensitivity, a significant advancement over traditional X-ray film which required exposure times of 30-40 minutes at synchrotrons and many hours with laboratory sources [6]. For complete data sets, crystals are rotated through a specified angular range (as little as 35° for high-symmetry cubic crystals up to 180° for lower-symmetry monoclinic crystals) while collecting multiple diffraction images [6]. Cryogenic protection (100 K nitrogen stream) is standard practice to mitigate radiation damage during data collection.

Data Processing and Structure Solution

Following data collection, the resulting diffraction images are processed through a standard workflow to determine the crystal structure. The protocol begins with data integration using software packages like XDS or HKL-2000 to convert spot positions and intensities into a list of structure factor amplitudes (Fₒ) with associated uncertainties (σ(Fₒ)) [5] [6]. Subsequent scaling and merging of symmetry-equivalent reflections yields a unique set of structure factors. Initial analysis of the diffraction pattern reveals the unit cell dimensions and space group symmetry based on systematic absences [6]. The central challenge, known as the phase problem, arises because experimental measurements capture only the amplitude of diffracted waves while losing their phase information [5] [9]. Traditional approaches to solving the phase problem include:

- Molecular Replacement: Utilizes a known homologous structure as a search model [9]

- Direct Methods: Applies probabilistic relationships between structure factor amplitudes to derive initial phase estimates, effective primarily at high resolutions (<1.2 Ã…) [9]

- Anomalous Dispersion: Exploits wavelength-specific scattering from heavy atoms

Once initial phases are obtained, electron density maps are calculated and iteratively improved through alternating cycles of model building and refinement until the atomic model optimally fits both the experimental data and expected geometric constraints [5] [6].

Figure 1: Protein Crystallography Workflow

Advanced Computational Methods in Structure Determination

Deep Learning Approaches for Low-Resolution Data

Recent advances in artificial intelligence have produced transformative computational methods for crystal structure determination, particularly when dealing with challenging low-resolution X-ray diffraction data. The XDXD framework represents a breakthrough as the first end-to-end deep learning model that predicts complete atomic structures directly from single-crystal X-ray diffraction data limited to 2.0 Ã… resolution [9]. This system employs a diffusion-based generative model conditioned on experimental diffraction patterns to produce chemically plausible crystal structures, bypassing the traditional need for manual electron density map interpretation [9]. When evaluated on 24,000 experimental structures from the Crystallography Open Database, XDXD achieved a 70.4% match rate with a root-mean-square error below 0.05, demonstrating remarkable accuracy even for systems containing 160-200 non-hydrogen atoms [9].

For powder X-ray diffraction data, where peak overlap presents significant analytical challenges, the PXRDGen system combines contrastive learning with generative models to achieve unprecedented accuracy [10]. This architecture integrates a pre-trained XRD encoder, a crystal structure generation module based on diffusion or flow models, and automated Rietveld refinement [10]. On the MP-20 dataset of inorganic materials, PXRDGen reached record match rates of 82% with a single sample and 96% with 20 samples, with root-mean-square errors approaching the precision limits of traditional Rietveld refinement [10]. These AI-driven methods effectively address longstanding challenges in crystallography, including localization of light atoms and differentiation of neighboring elements in the periodic table.

Database-Free Structure Creation Methods

For cases where database search fails to identify matching structures, the Evolv&Morph approach provides an innovative solution by combining evolutionary algorithms with crystal morphing to directly create structures reproducing target XRD patterns [11]. This method operates without prior knowledge from crystal structure databases, instead generating enormous numbers of candidate structures and selecting those maximizing the cosine similarity between their simulated XRD patterns and the target pattern [11]. The process applies Bayesian optimization to guide the morphing between structures, progressively improving the similarity score. For sixteen different crystal structure systems—twelve with simulated XRD patterns and four with experimental powder patterns—Evolv&Morph successfully created structures with cosine similarities of 99% for simulated targets and >96% for experimental patterns [11]. This demonstrates particular value for characterizing novel materials where database matches are unavailable.

Figure 2: AI-Driven Structure Determination

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful crystal structure determination requires carefully selected reagents and materials throughout the experimental workflow. The following table details key components of the crystallographer's toolkit:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Crystallography

| Category | Specific Examples | Function & Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Precipitants | Polyethylene glycol (PEG), Ammonium sulfate, 2-Methyl-2,4-pentanediol (MPD) | Induce protein crystallization by excluding water from solvation shell |

| Buffers | HEPES, Tris, Citrate, Phosphate buffers | Maintain specific pH environment optimal for crystal growth |

| Salts & Additives | Sodium chloride, Magnesium chloride, Lithium sulfate, Detergents | Modulate electrostatic interactions and improve crystal order |

| Cryoprotectants | Glycerol, Ethylene glycol, Sugars, Paratone-N oil | Prevent ice formation during cryocooling for data collection |

| Crystallization Plates | 24-well sitting drop plates, 96-well sparse matrix screens | Enable high-throughput crystallization condition screening |

| Sample Mounting | Cryoloops, Micromounts, Capillary tubes | Secure crystals during X-ray exposure while minimizing background scattering |

| X-Ray Sources | Rotating anode generators, Synchrotron beamlines | Provide high-intensity X-ray illumination for diffraction experiments |

| Detectors | CCD detectors, Hybrid pixel array detectors | Record diffraction patterns with high sensitivity and dynamic range |

The selection and optimization of these reagents profoundly impacts success rates in crystal structure determination projects. Commercial sparse matrix screens systematically combine these components to efficiently explore crystallization space, while specialized additives (e.g., divalent cations, heavy atoms) can be introduced to improve crystal quality or facilitate phasing [6].

The precise determination of inorganic crystal structures through X-ray diffraction research remains foundational to advances in materials science, pharmaceutical development, and molecular biology. The interrelationship between unit cells, lattice parameters, and space groups provides the theoretical framework for interpreting diffraction data and understanding atomic-scale organization in crystalline materials. While traditional crystallographic methods continue to yield vital structural insights, emerging computational approaches—particularly deep learning models and database-free structure creation—are dramatically accelerating and automating structure solution. These advanced protocols enable researchers to tackle increasingly challenging systems, from complex inorganic materials to biological macromolecules, pushing the boundaries of atomic-resolution structure determination. As these methodologies continue to evolve, they promise to unlock structural insights from previously intractable samples, further cementing X-ray crystallography's role as an indispensable tool for scientific discovery.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) stands as a cornerstone technique for determining the atomic-scale structure of crystalline materials, providing indispensable insights across scientific and industrial disciplines. Within inorganic chemistry and materials science, the choice between its two primary implementations—single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) and powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD)—is critical and is dictated by sample properties and the specific structural information required. SCXRD provides the most definitive structural picture, enabling researchers to obtain unit cell parameters, space group, and full atomic coordinates from a single crystal [12]. In contrast, PXRD analyzes polycrystalline powders containing countless randomly oriented microcrystals, making it widely applicable but structurally less direct due to the loss of orientational information [1] [13]. This application note delineates the principles, capabilities, and protocols for these techniques, contextualized within inorganic crystal structure determination, to guide researchers and development professionals in selecting and implementing the appropriate methodology.

Comparative Technique Analysis

The following table summarizes the core characteristics and capabilities of SCXRD and PXRD, highlighting their respective advantages and limitations.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Single-Crystal and Powder X-Ray Diffraction

| Feature | Single-Crystal XRD (SCXRD) | Powder XRD (PXRD) |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Requirement | A single, high-quality crystal of sufficient size (typically > 10-50 µm) [12] | Polycrystalline powder (microcrystals randomly oriented) [1] |

| Primary Output | Complete 3D atomic model (electron density map) [12] | 1D diffraction pattern (Intensity vs. 2θ) [1] |

| Structural Information | Full atomic coordinates, bond lengths/angles, thermal parameters, absolute configuration, disorder modeling [12] [14] | Phase identification, lattice parameters, crystallite size, strain, quantitative phase analysis [1] |

| Key Advantage | "Gold standard" for unambiguous, comprehensive structure determination [12] | High applicability; no need for single crystal growth; rapid phase analysis [1] [10] |

| Primary Limitation | Difficulty of growing a suitable single crystal [12] | Overlap of diffraction peaks (reflections) causes information loss, complicating structure solution [13] [10] |

| Typical Speed for Structure Solution | Fast: under a day with modern equipment/software [12] | Traditionally slow and labor-intensive; accelerated by new AI methods (seconds to minutes) [10] |

| Handling of Polymorphs | Can unambiguously define polymorphs and hydrates/solvates by revealing packing motifs [12] | Can identify mixtures of polymorphs and detect trace levels of alternate forms via pattern comparison [12] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Single-Crystal X-Ray Diffraction Analysis

The following workflow outlines the definitive method for determining a complete inorganic crystal structure.

Procedure Steps:

- Crystal Selection & Mounting: Select a single, well-formed crystal of the target inorganic compound under a microscope. The crystal must be of sufficient size (typically > 10-50 µm) and quality. Mount the selected crystal on a thin capillary loop using a viscous oil or directly on a fixed mount, ensuring it is centered [12] [14].

- Data Collection: Place the mounted crystal on the goniometer of a modern single-crystal diffractometer. The instrument will automatically center the crystal. Collect a full set of diffraction images by rotating the crystal through various angles (ω, φ, χ) while exposed to a monochromatic X-ray beam (e.g., Mo Kα or Cu Kα). The exposure time and rotation width are optimized for data completeness and resolution [12] [14].

- Data Reduction: Software processes the collected diffraction images to identify Bragg reflections, index them, and determine the unit cell parameters and Bravais lattice. Integrated intensities and estimated uncertainties for each reflection are obtained, resulting in a file of structure factor amplitudes (|F|) [14].

- Structure Solution: Using the reduced data, the phase problem is solved to generate an initial electron density map. For inorganic structures with heavy atoms, Patterson methods (e.g., SHELXT) are often effective. For lighter atom structures, Direct Methods (e.g., in SHELXT or OLEX2) may be employed. This step yields approximate positions for most, if not all, non-hydrogen atoms [14].

- Structure Refinement: The initial atomic model is refined against all collected diffraction data using a least-squares algorithm (e.g., SHELXL or OLEX2 refinemenet suite). Atomic coordinates, displacement parameters (Uiso/Ueq), and site occupancy factors are adjusted iteratively to minimize the discrepancy factor (R1). Anisotropic displacement parameters are typically used for all non-hydrogen atoms. The final model includes crystallographic data tables and a validated CIF (Crystallographic Information File) [12] [14].

- Validation & Reporting: The final structure is validated using checkCIF/IVT to ensure geometric and thermodynamic reasonableness. The CIF is deposited in a database (e.g., Cambridge Structural Database, ICSD), and a formal report, including tables of atomic coordinates, bond lengths, angles, and structure visualizations, is generated [14].

Protocol for Powder X-Ray Diffraction Analysis

This protocol covers both routine phase analysis and the more complex process of ab initio structure determination, highlighting the role of modern AI methods.

Procedure Steps:

- Powder Preparation: Grind the bulk inorganic sample into a fine, homogeneous powder using an agate mortar and pestle to minimize crystallite size effects and ensure a random distribution of orientations. Pack the powder uniformly into a sample holder (e.g., a flat plate or capillary), taking care to minimize preferred orientation, which can distort relative peak intensities [1].

- Data Collection: Load the prepared sample into a powder diffractometer. The instrument scans the sample through a range of Bragg angles (2θ), typically from 5° to 80° or higher, using monochromatic Cu Kα radiation. Modern diffractometers use position-sensitive detectors to collect data rapidly [1].

- Path A: Phase Analysis

- Pattern Processing: The raw data is processed by smoothing, subtracting the background, and identifying the position (2θ), intensity, and full width at half maximum (FWHM) of all diffraction peaks [1].

- Pattern Matching: The processed pattern is compared against a database of known reference patterns, such as the Powder Diffraction File (PDF). A successful match confirms the identity of the crystalline phases present. Quantitative phase analysis can be performed using the Rietveld method if the crystal structures of all components are known [12] [1].

- Path B: Structure Solution

- Indexing & Space Group Determination: The positions of the first 20-40 peaks are used by indexing software (e.g., TOPAS) to determine the unit cell parameters. Subsequent analysis of systematic absences in the pattern allows for the determination of the space group. Machine learning models can also predict space groups and cell parameters directly from the pattern [10] [15] [16].

- Structure Solution: This is the most challenging step. Traditional methods involve global optimization algorithms (e.g., simulated annealing, genetic algorithms) to find atomic positions that best match the observed intensities. Recently, end-to-end deep learning models like PXRDGen and CrystalNet have demonstrated the ability to solve structures directly from the PXRD pattern and chemical formula in seconds, achieving high accuracy [13] [10].

- Rietveld Refinement: The initial structural model is refined against the entire experimental powder pattern (not just extracted intensities). Structural parameters (atomic coordinates, occupancies), profile parameters, and microstructural parameters (crystallite size, strain) are adjusted to achieve the best possible fit between the calculated and observed patterns [10] [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents, Materials, and Software for XRD Analysis

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| High-Quality Inorganic Samples | The target material for analysis. Purity is critical for successful structure determination. |

| Agate Mortar and Pestle | For grinding and homogenizing bulk samples into fine powders for PXRD. |

| Silicon/Silicon Powder Standard | Used for instrument alignment and calibration in both SCXRD and PXRD. |

| Loop & Viscous Oil (e.g., Paratone-N) | For mounting and cryo-cooling single crystals on the diffractometer. |

| Capillaries & Flat Sample Holders | For mounting powder samples in PXRD experiments. |

| Crystallography Software (e.g., SHELX, OLEX2) | Industry-standard suite for SCXRD structure solution and refinement [14]. |

| Powder Analysis Software (e.g., TOPAS, HighScore) | Software for PXRD data processing, phase identification, and Rietveld refinement. |

| AI-Powered Structure Solution Tools (e.g., PXRDGen, CrystalNet) | Next-generation deep learning models for solving crystal structures directly from PXRD data [13] [10]. |

| Reference Databases (e.g., PDF, ICSD, CSD) | Essential for phase identification in PXRD and for comparing solved structures. |

| Bace1-IN-9 | Bace1-IN-9|BACE1 Inhibitor|Research Compound |

| Pitavastatin-d4 (sodium) | Pitavastatin-d4 (sodium), MF:C25H23FNNaO4, MW:447.5 g/mol |

SCXRD and PXRD are complementary techniques that form the bedrock of inorganic crystal structure determination. SCXRD remains the unequivocal "gold standard" for obtaining a complete, high-resolution atomic model when a suitable crystal is available, providing definitive data for research publications and intellectual property claims [12]. PXRD, while historically limited in its ability to solve novel structures, is indispensable for phase identification, quantification, and materials characterization in the absence of single crystals. The advent of artificial intelligence is dramatically reshaping the PXRD landscape, with models like PXRDGen and CrystalNet demonstrating that atomic-level structure determination from powder data alone is not only feasible but can be highly accurate and rapid [13] [10]. This advancement promises to automate a traditionally labor-intensive process, making robust crystal structure determination more accessible and accelerating discovery in inorganic chemistry and drug development.

The Critical Role of Crystallography in Materials Science and Drug Development

X-ray crystallography is a foundational analytical technique for determining the three-dimensional arrangement of atoms within crystalline substances. By analyzing the diffraction patterns produced when X-rays interact with a crystal, researchers can elucidate atomic-scale structures that are critical for understanding material properties and biological function [17]. This capability makes crystallography indispensable across scientific disciplines, from inorganic chemistry to pharmaceutical development. The technique's power lies in its ability to provide precise atomic coordinates, bond lengths, and bond angles, enabling researchers to establish structure-property relationships that drive innovation in materials design and drug discovery [18] [5].

Within inorganic chemistry, X-ray crystallography has been fundamental in developing key structural concepts, revealing bonding geometries, and explaining the unusual electronic or elastic properties of materials [17] [5]. Similarly, in pharmaceutical research, crystallography provides the structural basis for understanding drug-receptor interactions and enables structure-based drug design [6]. This article details the experimental protocols and applications of X-ray crystallography within the context of inorganic crystal structure determination, providing researchers with practical methodologies for advancing their work in materials science and drug development.

Core Principles of X-Ray Crystallography

X-ray crystallography is based on the principle that the regularly spaced atoms in a crystal lattice act as a diffraction grating for incident X-rays, producing a regular pattern of scattered radiation [17]. When X-rays strike a crystal, atoms scatter the incident radiation, and the scattered waves interact with one another through constructive and destructive interference. Constructive interference occurs only when the conditions of Bragg's Law are satisfied: nλ = 2d sinθ, where λ is the wavelength of the incident X-ray beam, d is the distance between crystal planes, θ is the angle of incidence, and n is an integer representing the order of diffraction [17] [18].

The fundamental repeating unit in any crystal is the unit cell, defined by six parameters: three side lengths (a, b, c) and three angles between them (α, β, γ) [17]. These parameters determine the crystal system, of which there are seven possible geometric shapes: triclinic, monoclinic, orthorhombic, tetragonal, trigonal, hexagonal, and cubic [6]. The specific arrangement of atoms within the unit cell, combined with the crystal system, generates a unique diffraction pattern that serves as a fingerprint for the crystalline material [17].

Table 1: The Seven Crystal Systems and Their Defining Parameters

| Crystal System | Defining Parameters | Bravais Lattices |

|---|---|---|

| Triclinic | a ≠b ≠c; α ≠β ≠γ ≠90° | Primitive |

| Monoclinic | a ≠b ≠c; α = γ = 90°, β ≠90° | Primitive, Base-centered |

| Orthorhombic | a ≠b ≠c; α = β = γ = 90° | Primitive, Base-centered, Body-centered, Face-centered |

| Tetragonal | a = b ≠c; α = β = γ = 90° | Primitive, Body-centered |

| Trigonal | a = b = c; α = β = γ ≠90° | Primitive |

| Hexagonal | a = b ≠c; α = β = 90°, γ = 120° | Primitive |

| Cubic | a = b = c; α = β = γ = 90° | Primitive, Body-centered, Face-centered |

Experimental Protocols for Inorganic Crystal Structure Determination

Sample Preparation and Crystallization

The initial and often most critical step in X-ray crystallography is obtaining high-quality single crystals of sufficient size for analysis. For inorganic compounds, common crystallization techniques include:

- Slow Evaporation: A solution of the compound is allowed to evaporate slowly at constant temperature, gradually increasing saturation until crystals form [18].

- Slow Cooling: A saturated solution at elevated temperature is slowly cooled, reducing solubility and promoting crystal growth [18].

- Vapor Diffusion: A solvent system in which the compound is insoluble is allowed to diffuse slowly into a solution of the compound, gradually reducing solubility [6].

- Crystallization from Melt: For high-temperature materials, the pure compound is melted and then slowly cooled below its melting point to form crystals.

For diffraction analysis, crystals typically need to be a minimum of 0.1-0.3 mm in their longest dimension to provide sufficient crystal lattice volume for exposure to the X-ray beam [6]. Before data collection, crystal quality should be verified through microscopic examination to ensure uniformity and lack of defects.

Data Collection Methods

Once suitable crystals are obtained, they must be properly mounted and aligned for data collection:

Crystal Mounting: Crystals can be mounted in a capillary tube at room temperature or cryo-cooled in a stream of liquid nitrogen at approximately 100 K [6]. Cryo-cooling reduces radiation damage during data collection, potentially allowing complete data sets to be collected from a single crystal.

X-ray Sources: Data can be collected using laboratory X-ray generators (producing X-rays via electrons striking a copper anode) or synchrotron sources, which provide more intense beams with higher quality optics [6]. Synchrotrons offer advantages for challenging crystallographic problems due to their intense, tunable X-ray beams.

Detection Systems: Modern crystallography primarily uses imaging plate detectors or charged-coupled device (CCD) detectors, which offer high sensitivity and rapid readout times compared to traditional X-ray film [6].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete structure determination process for inorganic compounds:

Diagram 1: Workflow for inorganic crystal structure determination.

Data Analysis and Structure Solution

Data processing involves converting raw diffraction images into a set of structure factors that can be used to determine the electron density within the crystal:

Data Reduction: Correcting for instrumental effects, absorption, and other experimental artifacts [18].

Unit Cell Determination: Calculating the dimensions of the repeating unit in the crystal from the spacing and symmetry of diffraction spots [6].

Space Group Determination: Identifying the crystal's space group from the systematic absences in the diffraction pattern [6].

Structure Solution: Using techniques such as direct methods, Patterson methods, or charge flipping to obtain an initial model of the atomic positions [18].

Structure Refinement: Iteratively improving the model against the experimental data using least-squares refinement until the agreement between observed and calculated structure factors is optimized [18].

Table 2: Key Crystallographic Databases for Inorganic Compounds

| Database Name | Content Focus | Number of Entries | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) | Inorganic crystal structures including pure elements, minerals, metals, and intermetallic compounds | >130,000 entries | Subscription |

| Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) | Organic and metal-organic structures | >300,000 entries | Subscription |

| American Mineralogist Crystal Structure Database | Mineral structures published in major mineralogy journals | Comprehensive mineral coverage | Free |

| Reciprocal Net | Molecular structures stored by research crystallographers | Varies | Free (Purdue member) |

Applications in Materials Science

X-ray crystallography plays a transformative role in materials science by enabling researchers to correlate atomic-scale structure with macroscopic material properties. Key applications include:

Structure-Property Relationships

By determining precise atomic arrangements, researchers can understand and predict material behavior. For example, crystallography has revealed how the arrangement of atoms in high-temperature superconductors influences their superconducting properties [18]. Similarly, studies of zeolites and other porous materials have shown how their complex frameworks of silicon and aluminum atoms determine their catalytic and molecular sieve properties [18].

Materials Engineering and Design

The ability to determine crystal structures enables the rational design of new materials with tailored properties. Materials engineers use crystallographic data to modify material performance by manipulating crystal structures through doping, defect engineering, or creating composite structures [17]. This approach has led to advances in battery materials, photovoltaic cells, and thermoelectric materials.

Nanomaterial Characterization

X-ray crystallography has been adapted to study nanostructured materials, providing information about nanoparticle size, shape, and composition [18]. While traditional single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) requires larger crystals, complementary techniques like powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) and electron crystallography (EC) can be applied to nanocrystalline materials that are too small for conventional SCXRD [19].

The relationship between crystallographic analysis and materials development is illustrated below:

Diagram 2: Crystallography applications in materials science.

Applications in Drug Development

In pharmaceutical research, X-ray crystallography provides critical structural information that drives drug discovery and development:

Structure-Based Drug Design

The determination of three-dimensional protein structures, particularly with bound substrates or inhibitors, enables rational drug design [6]. Researchers can identify active sites, understand molecular recognition, and design novel compounds with optimized binding characteristics. This approach has revolutionized modern drug discovery, reducing the time and cost of bringing new therapeutics to market.

Protein-Ligand Interactions

Crystallography allows precise mapping of intermolecular interactions between drug candidates and their biological targets [6]. By visualizing hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, and van der Waals contacts, researchers can explain structure-activity relationships and guide medicinal chemistry optimization.

Polymorph Screening

Pharmaceutical compounds can exist in multiple crystalline forms (polymorphs) with different physical properties that affect drug stability, bioavailability, and manufacturability. X-ray powder diffraction is routinely used to identify and characterize polymorphs during drug development to ensure consistent product quality [17].

Table 3: Key Crystallographic Databases for Biological Macromolecules

| Database Name | Content Focus | Number of Entries | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | 3D structures of proteins, nucleic acids, and complex assemblies | >200,000 entries | Free |

| Biological Macromolecule Crystallization Database (BMCD) | Crystallization conditions for macromolecules | Comprehensive | Free |

| Nucleic Acid Database (NDB) | Structural information about nucleic acids | ~5,000 structures | Free |

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful crystallographic studies require specific materials and reagents throughout the experimental workflow:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for X-Ray Crystallography

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Inorganic Compounds | Sample synthesis and crystallization | ≥99.9% purity, stoichiometrically defined |

| Crystallization Reagents | Promoting crystal growth | Precipitants (PEGs, salts), buffers, additives |

| Cryoprotectants | Preventing ice formation during cryo-cooling | Glycerol, paraffin oil, various cryoprotective solutions |

| Mounting Tools | Crystal manipulation and mounting | MicroLoops, capillaries, magnetic caps |

| X-Ray Transparent Tapes | Securing samples during data collection | Low-absorption adhesives |

| Calibration Standards | Verifying instrument performance | Silicon powder, corundum standards |

Advanced Techniques and Future Directions

The field of X-ray crystallography continues to evolve with technological advancements:

Complementary Methods for Complex Structures

For crystals that are too small for conventional SCXRD or too complex for PXRD, electron crystallography (EC) provides a valuable complementary approach [19]. Recent developments in three-dimensional electron diffraction techniques, such as automated electron diffraction tomography (ADT) and rotation electron diffraction (RED), have enabled structure determination from nanocrystals [19].

Time-Resolved Crystallography

Using advanced X-ray sources like X-ray free electron lasers (XFELs), researchers can now study short-lived intermediate states in chemical and biological processes, providing insights into reaction mechanisms [19].

Combined Approaches

Increasingly, complex structural problems require the integration of multiple techniques. Combining X-ray diffraction with electron microscopy, spectroscopy, and computational methods provides a more comprehensive understanding of material properties [19].

The following diagram illustrates how different techniques complement each other for solving complex structural problems:

Diagram 3: Complementary structure-solving techniques.

Modern Methodologies: From Traditional Refinement to AI-Powered Structure Solution

Rietveld Refinement for Powder Diffraction Data

Rietveld refinement is a powerful computational technique for characterizing crystalline materials from powder diffraction data. First described by Hugo Rietveld, this method represents a full pattern fitting approach where a theoretical line profile is iteratively adjusted until it closely matches the measured experimental profile. Unlike traditional methods that analyze individual peaks in isolation, Rietveld refinement simultaneously analyzes the entire diffraction pattern, enabling the extraction of detailed structural and microstructural information. This methodology has become indispensable across numerous scientific disciplines involving crystalline materials, including materials science, chemistry, geology, and pharmaceutical development [20].

The fundamental principle underlying Rietveld refinement is the calculation of a complete powder diffraction pattern based on a structural model, which includes crystallographic parameters, peak shape descriptions, and background characteristics. This calculated pattern is then compared to the observed experimental data, and the differences between them are minimized through a least-squares refinement process. The method's versatility allows researchers to determine not only phase composition but also detailed structural parameters, anisotropic characteristics, crystallite size, microstrain, and atomic displacement parameters [20]. For inorganic crystal structure determination, Rietveld refinement provides a comprehensive approach to solving complex structural problems that are common in materials research.

Theoretical Foundation

Fundamental Principles

The Rietveld method operates on the premise that every point, y{i}(obs), in the observed powder diffraction pattern can be expressed as a function of the Bragg angle, *θ*{i}, and represents a combination of contributions from Bragg reflections from all crystalline phases plus a background intensity. The calculated intensity, y_{i}(calc), at each point i is given by:

y{i}(calc) = *y*{i}(bkg) + S Σ K |F{K}|² *Φ* (2*θ*{i} - 2θ{K}) *P*{K} A

where y{i}(bkg) is the background intensity, *S* is the scale factor, *K* represents the Miller indices (*hkl*) for Bragg reflections, *F*{K} is the structure factor, Φ is the reflection profile function, P{K} is the preferred orientation function, and *A* is the absorption factor. The structure factor *F*{K} is fundamentally related to the atomic arrangement within the crystal structure and is calculated as:

F{K} = Σ *f*{j} exp[2πi(hx{j} + *ky*{j} + lz{j})] exp[-*B*{j}(sinθ/λ)²]

where f{j} is the atomic scattering factor, (*x*{j}, y{j}, *z*{j}) are the fractional coordinates of atom j in the unit cell, and B_{j} is its temperature factor [20].

The refinement process systematically varies parameters in the calculated pattern to minimize the difference between the observed and calculated profiles. This is achieved by minimizing the residual function:

R = Σ w{i} [*y*{i}(obs) - y_{i}(calc)]²

where w{i} is the statistical weight, typically taken as 1/*y*{i}(obs). The quality of the refinement is assessed using various agreement indices, including the profile R-factor (R{p}), weighted profile R-factor (*R*{wp}), expected R-factor (R_{exp}), and the goodness-of-fit (GOF) indicator [20].

Quantitative Phase Analysis

The Rietveld method has revolutionized quantitative phase analysis (QPA) of crystalline mixtures by providing a "standardless" approach that uses crystal structure descriptions of each component to calculate their respective diffraction patterns. The weight fraction (W_{k}) of phase k in a multiphase mixture is determined using the equation:

W{k} = (*s*{k}Z{k}*M*{k}V{k}) / Σ (*s*{i}Z{i}*M*{i}V_{i})

where s is the Rietveld scale factor, Z is the number of formula units per unit cell, M is the mass of the formula unit, and V is the unit-cell volume [20]. This approach has been successfully applied to various challenging systems, including inorganic crystalline phases, organic compounds, and mixtures containing amorphous content [21].

The accuracy of Rietveld quantitative phase analysis depends on several factors, including radiation choice, sample preparation, and data collection strategies. Comparative studies have demonstrated that high-energy Mo Kα1 radiation often yields slightly more accurate analyses than conventional Cu Kα1 radiation, despite the latter's approximately ten times higher diffraction intensity. This improved accuracy with Mo radiation is attributed to the larger irradiated volume (approximately 100 mm³ for Mo transmission geometry versus 2 mm³ for Cu reflection geometry) and reduced systematic errors associated with higher energy radiation [21].

Current Methodologies and Advances

Traditional Approaches and Considerations

Traditional Rietveld refinement requires careful attention to numerous experimental and computational factors to ensure accurate results. Sample preparation is particularly critical, as the reproducibility of peak intensity measurements is governed by particle statistics. This can be improved by using short-wavelength radiation, continuous sample spinning during data collection, and careful milling to reduce particle size without inducing amorphization or excessive peak broadening [21].

The choice of radiation source significantly impacts refinement quality. As highlighted in Table 1, different radiation types offer distinct advantages and limitations for specific applications. For inorganic materials with high absorption coefficients, Mo Kα1 radiation often provides superior results due to deeper penetration and reduced microabsorption effects, despite its lower diffraction power compared to Cu Kα1 radiation [21].

Table 1: Comparison of X-ray Radiation Sources for Rietveld Refinement

| Radiation Type | Wavelength (Ã…) | Irradiated Volume | Relative Intensity | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu Kα1 | 1.5406 | ~2 mm³ (reflection) | 10.2× (reference) | General purpose, organic materials |

| Mo Kα1 | 0.7093 | ~100 mm³ (transmission) | 1× | Inorganic materials, high absorption |

| Synchrotron | Variable (e.g., 0.4959-0.7744) | Variable | Extremely high | High-resolution, complex structures |

The limits of detection and quantification represent important considerations in Rietveld QPA. For well-crystallized inorganic phases using laboratory powder diffraction, the limit of quantification (LoQ) is approximately 0.10 wt% in stable fits with good precision. However, at this concentration level, accuracy remains poor with relative errors approaching 100%. Only contents higher than 1.0 wt% typically yield analyses with relative errors below 20%. The limit of detection (LoD) is approximately 0.2 wt% for Cu radiation and 0.3 wt% for Mo radiation under similar recording conditions [21].

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Advances

Recent advancements in artificial intelligence have revolutionized powder diffraction crystal structure determination, addressing longstanding challenges in the field. The PXRDGen neural network represents a breakthrough approach that integrates pretrained XRD encoders with generative models to determine crystal structures with atomic accuracy (Table 2) [10].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of AI-Based Structure Determination Methods

| Method | One-Sample Match Rate | Twenty-Sample Match Rate | Key Features | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PXRDGen (Transformer encoder) | 82% | 96% | Conditional structure generation, Rietveld refinement | Inorganic materials, MP-20 dataset |

| PXRDGen (CNN encoder) | Higher than Transformer | N/A | Flexible pretraining parameters | Broad crystalline materials |

| CrystalNet | Not specified | Not specified | Variational query-based network | Cubic and trigonal systems |

| XtalNet | Not specified | Not specified | Contrastive learning, diffusion models | Complex MOF materials |

PXRDGen employs an end-to-end neural network architecture that learns joint structural distributions from experimentally stable crystals and their corresponding powder X-ray diffraction patterns. The system comprises three key modules: a pretrained XRD encoder that aligns PXRD patterns with crystal structures using contrastive learning, a crystal structure generation module that produces atomic coordinates conditioned on PXRD features and chemical formulas, and a Rietveld refinement module that ensures optimal alignment between predicted structures and experimental data [10].

This AI-driven approach effectively tackles key challenges in powder XRD analysis, including the resolution of overlapping peaks, localization of light atoms (such as hydrogen or lithium), and differentiation of neighboring elements. Evaluation on the MP-20 inorganic dataset (containing experimentally stable inorganic materials with 20 or fewer atoms per primitive cell) demonstrates that PXRDGen achieves root mean square errors generally less than 0.01, approaching the precision limits of traditional Rietveld refinement but with significantly reduced human intervention and processing time [10].

Experimental Protocols

Sample Preparation and Data Collection

Proper sample preparation is crucial for obtaining high-quality powder diffraction data suitable for Rietveld refinement. The following protocol outlines the essential steps:

Sample Grinding and Homogenization: Gently grind the sample using an agate mortar and pestle for approximately 20 minutes to ensure homogeneity. Avoid excessive grinding that may induce amorphous phases or alter crystallite size distribution [21].

Particle Size Control: Achieve optimal particle statistics by reducing particle size to the 1-10 micrometer range. Verify appropriate sizing through microscopic examination or by monitoring peak broadening in preliminary diffraction patterns.

Sample Loading: For reflection geometry (typically used with Cu Kα radiation), pack the powdered sample into a flat holder to ensure a smooth surface and minimize preferred orientation. For transmission geometry (often used with Mo Kα radiation), load the sample into a thin-walled capillary [21].

Data Collection Parameters:

- Cu Kα Radiation: Set voltage to 40 kV, current to 40 mA, step size to 0.02° 2θ, and counting time to 2-10 seconds per step depending on sample characteristics.

- Mo Kα Radiation: Use voltage of 50 kV, current of 40 mA, step size of 0.01° 2θ, and longer counting times (10-30 seconds per step) to compensate for lower diffraction intensity [21].

Angular Range: Collect data across a sufficient angular range (e.g., 5-80° 2θ for Cu Kα, 2-50° 2θ for Mo Kα) to ensure adequate reflection coverage for reliable refinement.

Standard Measurement: Include a measurement of a certified standard material (such as NIST SRM 674b or LaB₆) under identical conditions for subsequent instrumental broadening correction [20].

Rietveld Refinement Workflow

The following step-by-step protocol describes the Rietveld refinement process for inorganic crystal structure determination:

Figure 1: Rietveld Refinement Workflow for Inorganic Materials

Data Preparation: Import the raw diffraction data into the refinement software. Perform background subtraction, typically using a Chebyshev polynomial function with 5-12 coefficients. Apply corrections for instrumental aberrations if necessary [20].

Initial Model Establishment: Obtain crystal structure models for all identified phases in the sample from crystallographic databases such as the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) or Crystallography Open Database (COD). For complex systems, begin with a single dominant phase and progressively add minor phases [20].

Preliminary Refinement: Initiate refinement with the following sequence of parameters:

- Scale factors for each phase

- Zero-point shift correction

- Unit cell parameters for each phase

- Sample displacement errors

At this stage, hold profile parameters and structural parameters at their initial values [20].

Profile Parameter Refinement: Introduce peak shape parameters into the refinement process:

- Gaussian (U, V, W) and Lorentzian (X, Y) components of profile coefficients

- Preferred orientation parameters using March-Dollase or spherical harmonic functions

- Background polynomial coefficients

- Specimen transparency and roughness parameters [20]

Structural Parameter Refinement: Once the profile matches satisfactorily, begin refining structural parameters:

- Atomic coordinates (starting with heaviest atoms)

- Isotropic temperature factors

- Site occupancy factors for mixed occupancy sites

- Anisotropic displacement parameters for well-ordered structures [20]

Microstructural Analysis: For materials with broadened diffraction peaks, refine crystallite size and microstrain parameters using appropriate models (e.g., Thompson-Cox-Hastings pseudo-Voigt function). Note that accurate microstructural analysis requires prior instrumental broadening correction using standard reference materials [20].

Validation and Assessment: Critically evaluate the refinement quality through:

- Visual inspection of the difference plot

- Analysis of agreement indices (R-factors and GOF)

- Verification of chemical plausibility (bond lengths, angles, thermal parameters)

- Statistical analysis of parameter uncertainties [20]

Export Results: Document the final refinement parameters, quantitative phase composition, structural data, and microstructural characteristics for reporting and further analysis.

Accuracy Assessment and Troubleshooting

Assessing the quality of Rietveld refinement requires careful analysis of multiple indicators. The key agreement indices include:

- Profile R-factor (R{p}) = Σ|*y*{i}(obs) - y{i}(calc)| / Σ|*y*{i}(obs)|

- Weighted profile R-factor (R{wp}) = [Σ*w*{i}(y{i}(obs) - *y*{i}(calc))² / Σw{i}(*y*{i}(obs))²]^{1/2}

- Expected R-factor (R{exp}) = [(*N* - *P*) / Σ*w*{i}(y_{i}(obs))²]^{1/2}

- Goodness-of-fit (GOF) = (R{wp} / *R*{exp})²

where N is the number of observations and P is the number of refined parameters. Ideally, GOF should approach 1.0, with values below 4.0 generally considered acceptable for phase analysis [20].

Common refinement issues and their solutions include:

- High Background: Increase polynomial background coefficients or implement more sophisticated background models.

- Systematic Peak Shift: Refine zero-point error and specimen displacement parameters.

- Peak Asymmetry: Implement appropriate asymmetry correction functions.

- Poor Fit at Low Angles: Check for beam spillover, sample transparency, or primary beam divergence effects.

- Unexplained Peaks: Consider the presence of unidentified minor phases or impurities.

- Unphysical Structural Parameters: Verify the initial structural model and constraint strategies.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Software and Databases

Table 3: Essential Resources for Rietveld Refinement

| Resource | Type | Key Function | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| TOPAS | Software | Whole pattern fitting, Rietveld refinement, microstructure analysis | Commercial |

| EXPO | Software | Structure solution and refinement from powder data | Free |

| GSAS-II | Software | Comprehensive Rietveld analysis package | Free |

| FullProf | Software | Pattern matching, structure refinement, magnetic structures | Free |

| ICDD PDF-5+ | Database | Reference diffraction patterns for phase identification | Commercial |

| ICSD | Database | Inorganic crystal structure data | Commercial |

| COD | Database | Open-access crystal structure database | Free |

| JADE Pro | Software | XRD pattern processing, quantification, and interpretation | Commercial |

| AChE/BChE-IN-4 | AChE/BChE-IN-4|Dual Cholinesterase Inhibitor for Research | AChE/BChE-IN-4 is a dual acetyl- and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitor for Alzheimer's disease research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Cortisone-d2 | Cortisone-d2, MF:C21H28O5, MW:362.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Rietveld Refinement Experiments

| Material/Standard | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| NIST SRM 674b (CeOâ‚‚) | Instrumental broadening calibration | Crystallite size and strain analysis |

| LaB₆ (NIST SRM 660c) | Peak position and shape calibration | Instrument alignment and resolution assessment |

| Silicon Powder | Zero-angle and unit cell standard | Accuracy verification of diffraction angles |

| α-Al₂O₃ (Corundum) | Quantitative analysis standard | Reference material for phase quantification |

| Agate Mortar and Pestle | Sample homogenization | Particle size reduction and mixing |

| Sample Holders (Flat plate) | Sample presentation for reflection geometry | Standard measurement configuration |

| Capillary Tubes | Sample containment for transmission geometry | Measurements with Mo Kα radiation |

| Microcrystalline Cellulose | Diluent for low-absorbing samples | Reduction of absorption effects in organic materials |

Rietveld refinement has evolved from a specialized structural analysis technique to a comprehensive methodology for powder diffraction data analysis. The integration of artificial intelligence, as demonstrated by systems like PXRDGen, represents a paradigm shift in how researchers approach crystal structure determination from powder data. These AI-driven methods achieve remarkable accuracy with minimal human intervention, potentially reducing structure solution time from days to seconds while maintaining precision approaching traditional Rietveld refinement [10].

For inorganic crystal structure determination, the careful selection of experimental parameters—particularly radiation type—combined with rigorous sample preparation and systematic refinement strategies remains essential for obtaining accurate results. The continued development of computational approaches, combined with established experimental protocols, ensures that Rietveld refinement will maintain its critical role in advancing materials research across scientific disciplines. As the field progresses, the integration of multimodal data sources and increasingly sophisticated computational methods promises to further enhance the power and accessibility of this indispensable technique for characterizing crystalline materials.

Overcoming the Phase Problem in Low-Resolution Data

The determination of inorganic crystal structures via X-ray diffraction (XRD) is fundamental to advancements in materials science, chemistry, and drug development. The central challenge in this process is the phase problem: while diffraction experiments measure the amplitudes of structure factors, the phase information is lost during measurement [22]. This loss renders the direct calculation of electron density maps impossible. The problem is particularly acute for low-resolution data (typically worse than 1.5-2.0 Ã…), which is common for complex inorganic materials, nano-crystals, or systems that are difficult to crystallize perfectly.

Traditional methods for phase determination, such as direct methods, require high-resolution data (better than 1.2 Ã…) and are often inadequate for larger unit cells or complex symmetries [9]. Experimental phasing through isomorphous replacement or anomalous scattering requires additional experiments and often heavy-atom derivatives, which can be non-trivial to obtain [23]. This application note outlines modern computational and experimental strategies designed to overcome these limitations, enabling robust structure determination from low-resolution diffraction data.

AI-Driven End-to-End Structure Determination

Recent breakthroughs in deep learning are reshaping the approach to the phase problem by bypassing traditional phasing and model-building steps altogether. These methods learn to directly map diffraction data to atomic models.

The XDXD Framework

The XDXD (X-ray Diffusion for structure Determination) framework is the first end-to-end deep learning model that predicts a complete atomic crystal structure directly from a single-crystal XRD pattern and chemical composition [9].

- Architecture: The model employs a diffusion-based generative architecture. It consists of an XRD encoder (based on transformer layers) that processes the diffraction signal, and a Diffraction-Conditioned Structure Predictor (DCSP) that iteratively refines atomic coordinates from random noise, conditioned on the diffraction data embeddings [9].

- Handling Data Uncertainty: To simulate experimental noise, the model is trained with random signal dropout, where 0-10% of diffraction signals are randomly removed [9].

- Performance: Evaluated on a benchmark of 24,000 experimental structures from the Crystallography Open Database (COD) with data limited to 2.0 Ã… resolution, XDXD achieves a 70.4% match rate with a root-mean-square error (RMSE) below 0.05. Its performance scales with complexity, maintaining a ~40% match rate even for systems with 160-200 atoms per unit cell [9].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of the XDXD Model on Low-Resolution (2.0 Ã…) Data

| Number of Non-Hydrogen Atoms (per unit cell) | Match Rate (%) | Typical RMSE |

|---|---|---|

| 0 - 40 | ~90 (estimated) | Low (<0.05) |

| 40 - 80 | ~80 (estimated) | Moderate |

| 80 - 120 | ~65 (estimated) | Moderate |

| 120 - 160 | ~50 (estimated) | Slightly Higher |

| 160 - 200 | ~40 | Slightly Higher |

The PXRDGen Framework for Powder Data

For powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) data, which suffers from peak overlap and reduced information content, the PXRDGen model provides a state-of-the-art solution [10].

- Architecture: PXRDGen integrates a pre-trained XRD encoder, a crystal structure generation module (using diffusion or flow-based models), and an integrated Rietveld refinement module. The XRD encoder uses contrastive learning to align the latent space of PXRD patterns with crystal structures [10].

- Performance: On the MP-20 dataset of inorganic materials, PXRDGen achieves record-breaking match rates of 82% (1-sample) and 96% (20-samples) for valid compounds. The RMSE for atomic coordinates is generally less than 0.01, approaching the precision limits of Rietveld refinement [10].

The workflow for these AI-based structure determination methods is summarized below.

Advanced Computational & Experimental Protocols

Ab Initio Phasing via Solvent Flatness Constraint

For high-solvent-content crystals (solvent fraction >70%), a powerful ab initio phasing protocol exists that treats phasing as a constraint satisfaction problem [24].

- Principle: The method relies on the solvent flatness constraint—the concept that the solvent region in a protein crystal is largely featureless. When the solvent volume fraction is sufficiently high, this constraint provides enough redundancy to uniquely determine the electron density using only the diffraction amplitudes [24].

- Algorithm: The Difference Map algorithm, an iterative projection algorithm (IPA), is used. It iterates between real space (applying constraints like solvent flatness and positivity) and Fourier space (enforcing agreement with measured amplitudes). This algorithm has superior global convergence properties compared to conventional iterative density modification [24].

- Workflow:

- Low-Resolution Envelope Determination: The molecular envelope is first approximated using only the lowest-resolution data.

- Full-Resolution Phase Determination: All available data are used for phase determination, with the molecular envelope continuously updated.

- Clustering and Consensus: Multiple runs with random starting phases are performed. A clustering procedure identifies consistent results, which are averaged to produce a consensus solution [24].

- Application Scope: This method has been successfully demonstrated on 42 known structures with solvent fractions of 0.60–0.85. It works robustly at intermediate resolutions (1.9–3.5 Å) but is most reliable with solvent fractions greater than 0.70 [24].

Directed Soaking for Experimental Phasing

For systems where computational phasing is challenging, a robust experimental method called "directed soaking" can be employed to obtain high-quality experimental phases [23].

- Principle: This strategy rationally engineers a specific high-affinity binding site for a heavy-atom compound directly into the RNA helix. This replaces the traditional "soak and pray" method with a reliable and predictable derivatization technique [23].

- Key Reagent: The method utilizes the G·U wobble pair motif, which creates a pocket in the RNA major groove that selectively binds trivalent cations like cobalt(III) hexammine, iridium(III) hexammine, or osmium(III) hexammine [23].

- Protocol:

- Design and Insertion: An optimal version of the G·U motif, identified through crystallographic analysis, is inserted into the RNA helix of interest.

- Crystallization and Soaking: The RNA is crystallized, and the crystal is soaked in a solution containing the hexammine complex.

- Data Collection and Phasing: The bound heavy atom provides a strong anomalous signal, enabling phasing via Single-wavelength Anomalous Diffraction (SAD) or Multi-wavelength Anomalous Dispersion (MAD), even with in-house copper Kα radiation [23].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Directed Soaking

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Cobalt(III) Hexammine | Trivalent cation; binds specifically to engineered G·U motif; provides strong anomalous scattering signal for SAD/MAD [23]. |

| Engineered G·U Wobble Pair Motif | RNA structural element; creates a high-affinity, high-occupancy cation binding site for rational derivatization [23]. |

| Crystallization Chassis | A stable, well-characterized RNA/protein complex used to systematically test and crystallize different motif variants [23]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Software and Computational Tools

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function in Low-Resolution Structure Determination |

|---|---|---|

| XDXD | End-to-End Deep Learning Model | Directly generates complete atomic models from single-crystal XRD data and composition [9]. |

| PXRDGen | End-to-End Deep Learning Model | Solves and refines crystal structures directly from PXRD data, handling peak overlap and light atoms [10]. |

| Difference Map Algorithm | Iterative Projection Algorithm | Enables ab initio phasing for high-solvent-content crystals using constraints like solvent flatness [24]. |

| Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) | Deep Learning Architecture | Identifies constituent phases in complex multiphase inorganic compounds from their powder XRD patterns [25]. |

| Lapatinib impurity 18-d4 | Lapatinib Impurity 18-d4|Stable Isotope| | Lapatinib Impurity 18-d4 is a deuterium-labeled internal standard for precise LC-MS quantification of Lapatinib. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Lycbx | Lycbx, MF:C33H42K2N6O11S3, MW:873.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |