Harnessing Light: Mechanisms and Innovations in Metal Oxide Photocatalysts for Advanced Applications

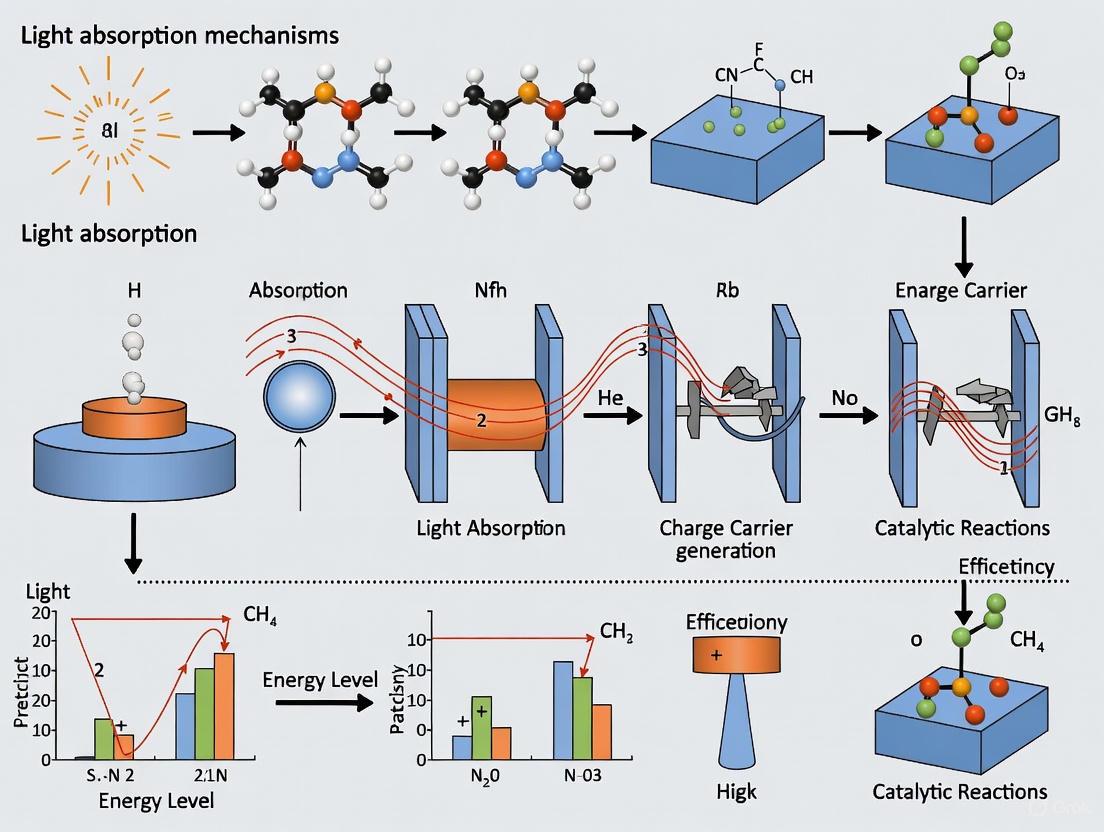

This article provides a comprehensive examination of light absorption mechanisms in metal oxide photocatalysts, tailored for researchers and scientists in material science and drug development.

Harnessing Light: Mechanisms and Innovations in Metal Oxide Photocatalysts for Advanced Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of light absorption mechanisms in metal oxide photocatalysts, tailored for researchers and scientists in material science and drug development. It explores the foundational principles of photocatalysis, including band theory and charge carrier dynamics. The scope extends to advanced material design strategies such as doping and heterojunction construction, tackles prevalent challenges like electron-hole recombination, and evaluates cutting-edge validation techniques including machine learning and computational fluid dynamics. By synthesizing insights across these four core intents, this review serves as a strategic guide for the rational design of high-performance photocatalytic systems with enhanced light absorption capabilities for biomedical and environmental applications.

The Photocatalytic Blueprint: Fundamental Light Absorption and Electronic Processes in Metal Oxides

Photocatalysis is a light-driven process where a semiconductor material, known as a photocatalyst, absorbs photons to generate electron-hole pairs that accelerate chemical reactions without being consumed itself [1]. This technology has emerged as a promising solution for addressing global environmental and energy challenges, including water purification, air detoxification, and renewable fuel production [2]. The process harnesses solar energy to activate chemical transformations, offering a sustainable pathway for both environmental remediation and energy storage [3].

Metal oxide semiconductors have garnered significant research attention due to their favorable properties for photocatalytic applications. These materials, including titanium dioxide (TiO₂), zinc oxide (ZnO), tungsten trioxide (WO₃), and various bismuth-based oxides, offer excellent stability, abundance, cost-effectiveness, and tunable electronic structures that can be tailored for specific redox reactions [2]. The fundamental principle of metal oxide photocatalysis lies in the generation of electron-hole pairs upon light absorption, which then migrate to the surface to participate in reduction and oxidation reactions with adsorbed species [2] [1].

Table 1: Fundamental Photocatalytic Processes in Metal Oxides

| Process Stage | Description | Governing Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Photon Absorption | Electron excitation from valence to conduction band | Bandgap energy, light intensity and wavelength |

| Charge Separation | Generation of electron-hole (eâ»-hâº) pairs | Semiconductor electronic structure, crystal defects |

| Charge Migration | Movement of carriers to catalyst surface | Crystal structure, morphology, particle size |

| Surface Reactions | Redox reactions with adsorbed species | Surface area, active sites, adsorbate concentration |

Mechanisms of Metal Oxide Photocatalysis

The photocatalytic mechanism in metal oxides follows a well-defined sequence of events initiated by light absorption. When a photon with energy equal to or greater than the material's bandgap is absorbed, it promotes an electron (eâ») from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB), creating a positively charged hole (hâº) in the valence band [1]. This separation of charge creates an electron-hole pair, or exciton, which must then migrate to the surface of the photocatalyst before recombination occurs.

Once at the surface, these charge carriers participate in redox reactions with adsorbed species. The photogenerated electrons typically reduce molecular oxygen (Oâ‚‚) to superoxide radicals (•Oâ‚‚â»), while the holes oxidize water (Hâ‚‚O) or hydroxide ions (OHâ») to generate hydroxyl radicals (•OH) [1]. These highly reactive oxygen species then non-selectively attack and degrade organic pollutants, eventually mineralizing them to carbon dioxide, water, and inorganic salts [4].

Diagram 1: Photocatalytic Mechanism in Metal Oxides

The efficiency of this process depends critically on the relationship between the semiconductor's band structure and the redox potentials of the target reactions. For a photocatalytic reaction to proceed thermodynamically, the conduction band minimum must be more negative than the reduction potential of the reaction, while the valence band maximum must be more positive than the oxidation potential [1]. This energy alignment ensures the photogenerated carriers possess sufficient energy to drive the desired redox processes.

Critical Material Properties and Design Strategies

Essential Photocatalyst Characteristics

The photocatalytic performance of metal oxides is governed by several interconnected material properties that must be carefully optimized:

Suitable Bandgap: The energy difference between valence and conduction bands determines the range of light absorption. While smaller bandgaps enable visible light absorption, they must still provide sufficient redox potential for water splitting or pollutant degradation [1]. Metal oxides typically exhibit bandgaps ranging from 2.0 eV (e.g., Fe₂O₃) to 3.4 eV (e.g., NiO) [4].

High Surface Area: Nanoscale dimensions significantly enhance photocatalytic activity by providing more active sites and reducing the distance charge carriers must travel to reach the surface [1]. Quantum size effects in nanomaterials also increase redox potential by discretizing energy levels [1].

Morphological Control: Crystal size, shape, porosity, and surface functionalization dictate key physicochemical parameters such as charge carrier mobility, adsorption capacity, and light scattering properties [2].

Stability: Photocatalysts must resist photocorrosion during operation. Strategies to enhance stability include crystal structure modification, doping, hybridization with other semiconductors, and optimization of reaction conditions [1].

Bandgap Engineering Strategies

Overcoming the inherent limitations of pristine metal oxides has driven extensive research into bandgap engineering and material modifications:

Doping: Introducing transition metals (e.g., Fe, Cu, Co) or non-metals (e.g., N, C, S) into the oxide lattice creates intermediate energy levels that reduce the effective bandgap and extend light absorption into the visible spectrum [2] [5].

Heterojunction Construction: Combining two or more semiconductors with aligned band structures enhances charge separation through internal electric fields. Particularly effective are Z-scheme heterojunctions that mimic natural photosynthesis by facilitating vectorial electron transfer between components [3].

Nanocomposite Formation: Integrating metal oxides with complementary materials such as carbon nanostructures, polymers, or metal sulfides creates synergistic effects that improve charge separation, broaden light absorption through sensitization, and increase surface area [4].

Defect Engineering: Controlled creation of oxygen vacancies or other defects modulates the electronic structure and introduces active sites that enhance adsorption and reaction kinetics [2] [4].

Table 2: Performance of Engineered Metal Oxide Photocatalysts

| Photocatalyst System | Modification Strategy | Application | Performance Metric | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiOâ‚‚/CuO | Heterojunction composite | Imazapyr degradation | Highest photonic efficiency | [5] |

| MNbâ‚‚O₆/g-C₃Nâ‚„ | Z-scheme heterostructure | Water splitting (Hâ‚‚ production) | 146 mmol hâ»Â¹ gâ»Â¹ | [6] |

| La-based perovskites | Bandgap engineering | Solar water splitting | Ideal bandgap (1.38-2.98 eV) | [7] |

| CdS QDs/ZnO | Quantum dot sensitization | Photocurrent generation | 100× higher efficiency | [8] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Synthesis of Metal Oxide Photocatalysts

Various synthesis methods enable precise control over the structural and morphological properties of metal oxide photocatalysts:

Sol-Gel Processing: This versatile method involves hydrolysis and polycondensation of metal precursors to form colloidal suspensions (sols) that evolve into integrated networks (gels). The process allows excellent control over composition, porosity, and particle size at low temperatures [2].

Hydrothermal/Solvothermal Synthesis: Crystallization from aqueous or non-aqueous solutions under elevated temperature and pressure conditions enables morphology control and high crystallinity without requiring post-annealing [2] [6].

Green/Bio-inspired Synthesis: Environmentally benign approaches using plant extracts, microorganisms, or biomolecular templates offer sustainable pathways for nanoparticle synthesis with controlled sizes and shapes [2].

Photocatalytic Performance Evaluation

Standardized protocols are essential for reliable assessment of photocatalytic activity:

Pollutant Degradation Assay: Typically performed using model organic contaminants (e.g., herbicides like Imazapyr, organic dyes) in aqueous solutions under controlled irradiation. The degradation efficiency is monitored through UV-Vis spectroscopy or HPLC analysis to track pollutant concentration over time [5].

Water Splitting Measurement: Photocatalytic hydrogen evolution is quantified using gas chromatography to measure gases produced from water splitting under irradiation. Sacrificial reagents (e.g., methanol, Na₂S/Na₂SO₃) are often employed to consume photogenerated holes and enhance electron availability for proton reduction [4] [1].

Quantum Efficiency Calculation: The apparent quantum yield (AQY) is determined using monochromatic light and calculated as: AQY = (Number of reacted electrons / Number of incident photons) × 100 [5].

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Photocatalyst Development

Advanced Material Architectures

Nanocomposite Systems

The integration of metal oxides with complementary materials has emerged as a powerful strategy to overcome limitations of single-component systems:

Metal Oxide Heterostructures: Combining TiO₂ with secondary metal oxides (ZrO₂, ZnO, Ta₂O₅, SnO, Fe₂O₃, CuO) creates interfaces that enhance charge separation through energy level alignment. Studies demonstrate the photocatalytic activity follows the order: TiO₂/CuO > TiO₂/SnO > TiO₂/ZnO > TiO₂/Ta₂O₅ > TiO₂/ZrO₂ > TiO₂/Fe₂O₃ > pristine TiO₂ [5].

Carbon-Metal Oxide Composites: Graphene, carbon nanotubes, or graphitic carbon nitride combined with metal oxides improve electrical conductivity, provide high surface area support, and enhance adsorption capacity. The carbon phase also acts as an electron acceptor, reducing charge recombination [4].

Quantum Dot-Sensitized Systems: Semiconductor quantum dots (e.g., CdS, PbS) attached to metal oxide scaffolds (TiOâ‚‚, ZnO) extend light absorption into the visible range through sensitization and enable multiple exciton generation effects [8].

Emerging Material Classes

Recent research has identified several promising material families with enhanced photocatalytic properties:

MNb₂O₆ Niobates: Transition metal niobates with the general formula MNb₂O₆ (M = Cu, Ni, Mg, Zn, Co, Fe, Mn) exhibit tunable band structures, chemical robustness, and visible-light activity. These materials typically display orthorhombic or monoclinic crystal structures with bandgaps ranging from ~2.0 to 3.0 eV, making them promising for solar water splitting [6].

Perovskite Oxides: ABO₃-type perovskites like La-based oxides (LaZO₃) offer tunable bandgaps (1.38-2.98 eV) with band edges well-aligned with water redox potentials. Their favorable electron-hole mobility ratios (D = 1.19-4.73) enable efficient charge transport and reduced carrier recombination [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Photocatalysis Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Titanium Dioxide (TiOâ‚‚) | Benchmark photocatalyst | Available in anatase, rutile, or mixed phases; Hombikat UV-100 is common commercial standard |

| Metal Oxide Precursors | Synthesis of photocatalysts | Titanium isopropoxide, zinc acetate, zirconium oxychloride for sol-gel and hydrothermal methods |

| Sacrificial Reagents | Enhance charge separation | Methanol, ethanol, Na₂S/Na₂SO₃, EDTA; consume holes to improve electron availability |

| Pollutant Models | Performance evaluation | Imazapyr, methylene blue, rhodamine B; represent environmental contaminants |

| Co-catalysts | Enhance surface reactions | Pt, Au, Ag nanoparticles; facilitate Hâ‚‚ evolution or oxidation kinetics |

| pH Buffers | Control reaction conditions | Phosphate, carbonate, or borate buffers; maintain optimal pH for specific applications |

| DBCO-PEG13-NHS ester | DBCO-PEG13-NHS ester, MF:C52H75N3O19, MW:1046.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 5-Formyl-2'-O-methyluridine | 5-Formyl-2'-O-methyluridine|Research Chemical | Explore 5-Formyl-2'-O-methyluridine for RNA research. This modified nucleoside is used in oligonucleotide studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

Photocatalysis represents a sophisticated intersection of materials science, surface chemistry, and photophysics that enables the direct conversion of solar energy into chemical potential. Metal oxides serve as the foundational platform for these technologies due to their tunable electronic structures, stability, and diverse morphological possibilities. Current research focuses on developing integrated material systems through heterojunction engineering, defect control, and nanoscale architecture to optimize light absorption, charge separation, and surface reaction kinetics.

The future trajectory of photocatalysis research will likely involve multifunctional systems capable of simultaneous energy production and environmental remediation, advanced Z-scheme configurations that mimic natural photosynthesis with high efficiency, and the integration of computational materials design with experimental synthesis to accelerate discovery. As these technologies mature from laboratory demonstrations to practical applications, considerations of scalability, long-term stability, and economic viability will become increasingly central to research directions. The continued refinement of metal oxide photocatalysts holds significant promise for contributing to sustainable energy and environmental solutions.

Band theory is the foundational theoretical model in solid-state physics that describes the states of electrons in solid materials, which can possess energy only within specific, allowed ranges [9]. This theory explains why materials exhibit vastly different electrical properties, classifying them as metals, semiconductors, or insulators based on their electronic band structure. In the context of metal oxide photocatalysts, understanding band theory is not merely academic; it provides the essential framework for designing materials that efficiently harness solar energy for environmental remediation and renewable fuel production [2] [4]. The precise arrangement of energy bands—particularly the valence band, conduction band, and the bandgap between them—directly determines a material's capability to absorb light and initiate photocatalytic reactions that can address pressing global challenges related to energy and pollution.

The evolution of band theory has enabled scientists to systematically engineer materials with tailored electronic properties. When individual atoms are brought together to form a solid, their discrete atomic energy levels interact and broaden into continuous bands of allowed energy states [9]. The valence band represents the highest range of electron energies where electrons are normally present at absolute zero temperature, while the conduction band constitutes the lowest range of vacant electronic states available for electrons to move freely through the material [10]. The transition from atomic orbitals to electronic bands is particularly crucial for metal oxides, where the interplay between metal and oxygen ions creates diverse electronic structures that can be precisely tuned for specific photocatalytic applications [4].

Fundamental Concepts: Valence Band, Conduction Band, and Band Gap

Valence Band

The valence band is the highest energy band populated by electrons at absolute zero temperature [10]. These electrons are primarily involved in chemical bonding between atoms and are not free to move throughout the crystal lattice. In metal oxides, the valence band typically consists primarily of oxygen 2p orbitals, which have significant electronegativity and hold electrons tightly [4]. For example, in nickel oxide (NiO), the valence band originates mainly from oxygen 2p orbitals, creating a stable electronic configuration that requires substantial energy to disrupt [4]. The energy level at the top of the valence band represents the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) in the solid-state system and serves as a reference point for determining the material's Fermi level and work function.

Conduction Band

The conduction band is the lowest energy band that is vacant or partially filled at absolute zero temperature [10]. When electrons gain sufficient energy to jump from the valence band to the conduction band, they become delocalized and can move freely throughout the material, enabling electrical conductivity. In metal oxides, the conduction band generally comprises empty d-orbitals of the transition metal cations [4]. In the case of NiO, the conduction band originates mainly from nickel 3d orbitals [4]. The energy level at the bottom of the conduction band represents the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) in the solid-state system. The position of the conduction band minimum relative to the vacuum level determines the reducing power of photogenerated electrons in photocatalytic systems.

Band Gap

The band gap represents the forbidden energy range between the top of the valence band and the bottom of the conduction band where no electron states can exist due to the quantization of energy [10]. This critical parameter determines the electrical conductivity and optical properties of materials. According to band theory, solids can be categorized based on their band gap characteristics:

- Metals: Conductors with no band gap or overlapping bands [10] [9]

- Semiconductors: Materials with relatively narrow forbidden gaps (typically 0.1-2.0 eV) that can be crossed by electrons with thermal or light energy [9]

- Insulators: Materials with wide forbidden energy gaps (several electron volts) that cannot be easily crossed [9]

The band gap energy (Eg) serves as the minimum photon energy required to excite an electron from the valence band to the conduction band, creating an electron-hole pair that can participate in photocatalytic reactions [10] [4].

Table 1: Band Gap Classification of Materials and Their Properties

| Material Type | Band Gap Range | Electrical Conductivity | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conductors | No band gap | Very high | Copper, Silver, Gold |

| Semiconductors | Narrow (∼1 eV) | Intermediate, tunable | Silicon, Germanium, TiO₂, ZnO |

| Insulators | Wide (>4 eV) | Very low | Diamond, Quartz, Al₂O₃ |

Band Theory in the Context of Metal Oxide Photocatalysts

Electronic Structure of Metal Oxides

Metal oxides exhibit a diverse range of optical, structural, and electronic properties that make them particularly suitable for photocatalytic applications [4]. Their electronic structures arise from the complex interplay between metal and oxygen ions, influenced by the metal's oxidation state, coordination geometry, and crystal structure. Metal oxides display various structural configurations, from simple rock salt (e.g., MgO) to complex perovskite (e.g., SrTiO₃) and layered structures (e.g., MoO₃) [4]. This structural diversity significantly impacts their electronic band structure and optical properties. Closely packed structures often lead to wide band gaps and transparent/insulating behavior, while open structures with transition metals can exhibit smaller band gaps, resulting in semiconducting or metallic conductivity [4].

Transition metal oxides frequently absorb visible light and exhibit characteristic colors due to partially filled d-orbitals and phenomena like d-d transitions, charge transfer transitions, and plasmon resonances [4]. For instance, NiO is optically renowned for its characteristic deep green color, which arises from electronic transitions within the visible range [4]. Its absorption spectrum exhibits pronounced absorption in the ultraviolet (UV) region, extending into the visible range, attributed to charge transfer transitions between the valence band (oxygen 2p orbitals) to the conduction band (nickel 3d orbitals) [4]. The bandgap energy of NiO typically resides around 3.4-4.0 eV, classifying it as a wide-bandgap material suitable for applications in the UV region [4].

Band Edge Shifts in Semiconductor Nanoparticles

The edge shifting of size-dependent conduction and valence bands represents a significant phenomenon studied in semiconductor nanocrystals [10]. When semiconductor nanocrystal size is restricted below the effective Bohr radius of the nanocrystal, quantum confinement effects become pronounced. The conduction and/or valence band edges shift to higher energy levels under this radius limit due to discrete optical transitions when the semiconductor nanocrystal is confined by the exciton [10]. As a result of this edge shifting, the effective band gap increases, providing a powerful strategy for tuning the optical and electronic properties of metal oxide photocatalysts. This size-dependent edge shifting of conduction and valence bands provides valuable information regarding the size or concentration of semiconductor nanoparticles and their band structures, enabling precise engineering of photocatalytic materials for specific applications [10].

Table 2: Selected Metal Oxides and Their Band Gap Properties

| Metal Oxide | Band Gap (eV) | Crystal Structure | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| TiOâ‚‚ | 3.0-3.2 [2] | Anatase, Rutile, Brookite | Photocatalysis, UV protection |

| ZnO | ~3.3 [2] | Wurtzite | Sensors, Transparent electrodes |

| WO₃ | 2.6-2.8 [2] | Monoclinic, Tetragonal | Electrochromic devices, Photocatalysis |

| NiO | 3.4-4.0 [4] | Rock salt | p-type semiconductor, Catalysis |

| BiVOâ‚„ | ~2.4 [2] | Monoclinic, Tetragonal | Visible-light photocatalysis |

Light Absorption Mechanisms in Metal Oxide Photocatalysts

Fundamental Photocatalytic Process

Photocatalysis using metal oxides is a prominent research domain within environmental remediation, energy conversion, and green chemistry [2]. The fundamental principle of metal oxide photocatalysis lies in the generation of electron-hole pairs upon light absorption [2]. When a photon with energy equal to or greater than the material's band gap strikes the semiconductor, it promotes an electron from the valence band to the conduction band, creating a highly reactive electron-hole pair [4]. This process leaves behind a positive hole in the valence band that can oxidize donor molecules, while the excited electron in the conduction band can reduce acceptor molecules [4].

The photocatalytic process typically involves three essential steps: (i) light absorption, (ii) charge separation and migration, and (iii) surface reactions [11]. In the initial stage, when a photocatalyst is illuminated with solar energy that matches or exceeds its band gap energy, it results in the creation of electron-hole pairs (eâ»/hâº) [11]. This entails electrons being excited from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB), leaving holes in the VB. The efficiency of this process depends critically on the relationship between the photon energy and the band gap energy of the metal oxide.

Charge Carrier Dynamics and Band Engineering

The electrical conductivity of non-metals is determined by the susceptibility of electrons to be excited from the valence band to the conduction band [10]. In semiconductors, some conductivity exists due to thermal excitation, where some electrons acquire sufficient energy to jump the band gap in one go [10]. Once in the conduction band, these electrons can conduct electricity, as can the holes they leave behind in the valence band. The hole is an empty state that allows electrons in the valence band some degree of freedom [10].

However, pristine metal oxides often face limitations such as nanoparticle agglomeration, rapid electron-hole recombination, limited visible light absorption, and low charge carrier mobility, which hinder their photocatalytic performance [4]. To overcome these challenges, researchers employ various band engineering strategies, including doping, creating heterojunctions, surface functionalization, and morphology control [4]. Combining metal oxides with other materials (semiconductors, carbonaceous nanomaterials, noble metals, or polymers) creates synergistic effects that enhance photocatalytic activity through improved charge separation, broadened light absorption, increased surface area, and enhanced stability [4].

Diagram 1: Band Theory and Photocatalytic Process in Metal Oxides - This diagram illustrates the fundamental process of electron excitation across the band gap upon photon absorption, leading to charge separation and subsequent redox reactions in photocatalytic metal oxides.

Experimental Protocols for Band Structure Analysis

Methodology for Band Gap Determination

The accurate determination of band gap energy is crucial for characterizing metal oxide photocatalysts. Several experimental techniques have been developed to measure this critical parameter:

UV-Vis Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy (DRS): This is the most widely used technique for determining the band gap energy of powder semiconductor samples. The experimental protocol involves:

- Grinding the metal oxide sample to a fine powder to ensure consistent reflectance

- Loading the powder into a sample holder with a transparent window

- Collecting reflectance spectra in the 200-800 nm range using an integrating sphere attachment

- Converting reflectance data to the Kubelka-Munk function: F(R) = (1-R)²/2R, where R is the reflectance

- Plotting [F(R)hv]â¿ versus photon energy (hv), where n = 1/2 for indirect band gaps and n = 2 for direct band gaps

- Extrapolating the linear portion of the plot to [F(R)hv]â¿ = 0 to determine the band gap energy

Photoluminescence (PL) Spectroscopy: This technique provides information about charge carrier recombination processes and defect states within the band gap. The standard protocol includes:

- Exciting the sample with a laser source at energy greater than the band gap

- Collecting the emitted radiation at right angles to the excitation source

- Analyzing the emission spectrum to identify band-to-band transitions and defect-related emissions

- Calculating the Stokes shift between absorption and emission maxima

Photoelectrochemical Measurements: These methods provide both band gap information and insight into charge carrier dynamics:

- Preparing working electrodes by depositing metal oxide films on conducting substrates

- Performing Mott-Schottky analysis at the semiconductor-electrolyte interface

- Determining the flat band potential from the x-intercept of the Mott-Schottky plot

- Calculating the conduction band position from the flat band potential

Advanced Characterization Techniques

For comprehensive understanding of band structure in metal oxide photocatalysts, researchers employ several sophisticated characterization methods:

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): This technique provides information about elemental composition, chemical state, and valence band maximum position. The experimental workflow involves:

- Mounting powder samples on conductive tape or pellets

- Acquiring high-resolution spectra of relevant core levels and valence band region

- Calibrating binding energy scale using carbon 1s peak at 284.8 eV

- Extrapolating the valence band spectrum to determine the valence band maximum

Electron Energy Loss Spectroscopy (EELS): When coupled with transmission electron microscopy, EELS provides band gap information with high spatial resolution, enabling the analysis of individual nanoparticles and heterojunctions.

Ultraviolet Photoelectron Spectroscopy (UPS): This method directly measures the valence band structure and work function of materials, offering crucial information for understanding electron transfer processes in photocatalytic systems.

Table 3: Experimental Techniques for Band Structure Analysis

| Technique | Information Obtained | Sample Requirements | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis DRS | Band gap energy, Absorption edge | Powder or thin film | Indirect measurement, Requires extrapolation |

| Photoluminescence | Recombination processes, Defect states | Solid samples | Surface-sensitive, Complex interpretation |

| XPS/UPS | Valence band maximum, Chemical states | Ultra-high vacuum compatible | Surface contamination issues |

| Mott-Schottky | Flat band potential, Carrier density | Electrode in electrolyte | Limited to electrolyte-compatible materials |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The experimental investigation of band structures in metal oxide photocatalysts requires specific materials and analytical tools. The following table details essential research reagents and their functions in band structure analysis and photocatalyst development.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Band Structure Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Titanium Dioxide (TiOâ‚‚) | Reference photocatalyst with well-characterized band structure (Eg = 3.0-3.2 eV) [2] | Benchmarking new materials, UV-driven photocatalysis |

| Zinc Oxide (ZnO) | Wide band gap semiconductor with good electron mobility [2] | Sensor development, Transparent conductive oxides |

| Tungsten Trioxide (WO₃) | Visible-light-responsive semiconductor (Eg = 2.6-2.8 eV) [2] | Photoelectrochemical water splitting, Smart windows |

| Bismuth Vanadate (BiVO₄) | Promising visible-light photocatalyst (Eg ≈ 2.4 eV) [2] | Solar water oxidation, Environmental remediation |

| Nitrogen Doping Agents (e.g., urea, NH₃) | Anion doping to reduce band gap via band narrowing [4] | Enhancing visible light absorption of wide band gap oxides |

| Transition Metal Dopants (Fe, Cu, Mn) | Cation doping to create intra-band gap states [4] | Extending light absorption range, Reducing recombination |

| Carbon-based Materials (graphene, CNTs) | Electron acceptors and conductive supports [4] | Enhancing charge separation in composite photocatalysts |

| Platinum/Noble Metal Cocatalysts | Electron sinks for enhanced charge separation [4] | Improving hydrogen evolution in photocatalytic water splitting |

| 2-Iodo-5-nitrosobenzamide | 2-Iodo-5-nitrosobenzamide | High-purity 2-Iodo-5-nitrosobenzamide for research. Explore its potential as a synthetic intermediate. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| Dichapetalin I | Dichapetalin I | Dichapetalin I is a cytotoxic merotriterpenoid for cancer research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Band Structure Analysis - This workflow outlines the comprehensive methodology for characterizing the band structure of metal oxide photocatalysts, from sample preparation through structural, optical, and electronic characterization to performance evaluation.

The fundamental principles of band theory—encompassing the valence band, conduction band, and the crucial bandgap—provide the essential theoretical framework for understanding and engineering metal oxide photocatalysts. The precise arrangement of these electronic bands determines a material's capacity to absorb light, generate charge carriers, and drive photocatalytic reactions for environmental remediation and renewable energy production. Current research continues to focus on band gap engineering strategies, including doping, heterojunction formation, nanostructuring, and composite development, to enhance the visible light absorption and charge separation efficiency of metal oxide photocatalysts. As characterization techniques advance and our understanding of charge carrier dynamics deepens, the rational design of photocatalysts with optimized band structures will play an increasingly vital role in addressing global energy and environmental challenges through solar-driven chemical transformations.

Photocatalysis represents a promising technology that harnesses light energy to drive chemical reactions, offering significant potential for addressing environmental and energy challenges [12]. In metal oxide photocatalysts, this process initiates when photons are absorbed, generating electron-hole pairs that subsequently enable a cascade of redox reactions at the catalyst surface [1]. This technical guide examines the fundamental principles and mechanisms of the photocatalytic cycle, with particular emphasis on reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation within the context of light absorption mechanisms in metal oxide research. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these processes is crucial for designing efficient photocatalytic systems for applications ranging from environmental remediation to advanced oxidation therapies.

The photocatalytic activity of metal oxides depends critically on their electronic structure, morphological characteristics, and surface properties [1]. Titanium dioxide (TiO₂), zinc oxide (ZnO), iron oxide (Fe₂O₃), and tungsten oxide (WO₃) are among the most studied metal oxides, each exhibiting distinct band gap energies, charge carrier dynamics, and stability profiles that dictate their photocatalytic performance [1]. This review systematically explores the photophysical and photochemical processes in these materials, from initial photon absorption to the formation of highly reactive oxygen species, with supporting quantitative data and experimental methodologies relevant to current research practices.

Fundamental Principles of Photocatalysis in Metal Oxides

Band Structure and Photon Absorption

Metal oxide photocatalysts are semiconducting materials characterized by their electronic band structure, consisting of a valence band (VB) filled with electrons and a conduction band (CB) that is generally empty, separated by a forbidden energy range known as the band gap [1] [13]. The photocatalytic process initiates when a photon with energy equal to or greater than the material's band gap is absorbed, promoting an electron (eâ») from the valence band to the conduction band, thereby creating a positively charged hole (hâº) in the valence band [1]. This electron-hole pair, termed an exciton, represents the primary photo-generated charge carriers that drive subsequent photocatalytic reactions.

The band gap energy fundamentally determines the light absorption capabilities of a photocatalyst. Metal oxides exhibit a range of band gap energies, which correspondingly dictate the wavelengths of light they can utilize [1]. For instance, titanium dioxide (TiO₂) possesses a wide band gap (~3.2 eV for anatase phase), requiring UV light for activation, while iron oxide (Fe₂O₃) has a narrower band gap (<2.1 eV), enabling visible light absorption [1]. The band structure must also align thermodynamically with the desired redox reactions; specifically, the conduction band minimum must be more negative than the reduction potential of target electron acceptors, while the valence band maximum must be more positive than the oxidation potential of electron donors [1].

Table 1: Band Gap Energies and Light Absorption Characteristics of Common Metal Oxide Photocatalysts

| Metal Oxide | Band Gap (eV) | Primary Absorption Range | Light Absorption Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|

| TiOâ‚‚ (Anatase) | ~3.2 | UV | High UV absorption |

| ZnO | ~3.3 | UV | High UV absorption |

| Fe₂O₃ | <2.1 | Visible | Extensive visible light absorption |

| WO₃ | ~2.8 | Visible | Visible-light sensitive |

| SnOâ‚‚ | ~3.6 | UV | Activation at ~350 nm |

Charge Carrier Dynamics

Following photon absorption and exciton formation, the photogenerated electrons and holes undergo several competing processes: (1) migration to the catalyst surface to participate in redox reactions, (2) recombination in the bulk, or (3) trapping at surface states [1] [14]. The efficiency of photocatalysis depends critically on the successful separation and migration of charge carriers to surface reaction sites before recombination occurs [1].

Nanoscale metal oxide particles significantly enhance photocatalytic performance by reducing the distance charge carriers must travel to reach the surface, thereby diminishing recombination probabilities [1]. Quantum size effects in nanomaterials also cause the conduction and valence bands to become discrete energy levels, increasing the redox potential of photogenerated electrons and holes and consequently enhancing their reactivity [1]. Surface area optimization represents another crucial factor, as higher specific surface areas provide more active sites for reactant adsorption and surface reactions [1].

The Photocatalytic Mechanism: From Charge Separation to ROS Generation

Initial Charge Separation and Migration

The photocatalytic mechanism begins with charge separation and the migration of photogenerated carriers to the catalyst surface. The following diagram illustrates this fundamental process in a metal oxide semiconductor nanoparticle:

Upon reaching the surface, these charge carriers initiate various redox reactions with adsorbed species. The holes exhibit strong oxidizing potential, while the electrons possess reducing capability, enabling them to participate in the formation of reactive oxygen species [1].

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Generation Pathways

The generation of reactive oxygen species occurs through well-defined electron transfer pathways involving oxygen and water molecules adsorbed on the catalyst surface. The primary ROS generation mechanisms include:

1. Superoxide Anion Formation: Conduction band electrons reduce molecular oxygen to form superoxide anion radicals [15]: [ O2 + e^- \rightarrow \bullet O2^- ]

2. Hydroxyl Radical Formation: Valence band holes oxidize water or hydroxide ions to generate hydroxyl radicals [1] [15]: [ H_2O + h^+ \rightarrow \bullet OH + H^+ ] [ OH^- + h^+ \rightarrow \bullet OH ]

3. Hydrogen Peroxide Formation: Superoxide anions can undergo further reduction and protonation to form hydrogen peroxide [15]: [ \bullet O2^- + e^- + 2H^+ \rightarrow H2O2 ] Alternatively, hydrogen peroxide can form through hydroxyl radical recombination: [ \bullet OH + \bullet OH \rightarrow H2O_2 ]

4. Singlet Oxygen Formation: Energy transfer from the excited photocatalyst to molecular oxygen can produce singlet oxygen, though this pathway is less common in metal oxide photocatalysis [15].

The following diagram illustrates the complete photocatalytic cycle, integrating photon absorption, charge separation, and ROS generation pathways:

Table 2: Characteristics of Primary Reactive Oxygen Species in Photocatalysis

| ROS Species | Formation Pathway | Redox Potential (V) | Primary Reactivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxyl Radical (•OH) | H₂O/OH⻠oxidation by h⺠| +2.8 | Non-selective, highly reactive oxidation |

| Superoxide Anion (•Oâ‚‚â») | Oâ‚‚ reduction by eâ» | -0.33 | Selective reduction, protonation to Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) | •O₂⻠reduction or •OH recombination | +1.78 | Oxidizing agent, precursor to •OH |

| Singlet Oxygen (¹O₂) | Energy transfer to O₂ | +0.65 | Selective oxidation of organics |

Thermodynamics and Energetic Considerations

The thermodynamic feasibility of ROS generation depends critically on the band edge positions of the metal oxide relative to the redox potentials of the relevant species. For instance, the conduction band must be more negative than the Oâ‚‚/•Oâ‚‚â» redox potential (-0.33 V vs. NHE) for superoxide formation to occur, while the valence band must be more positive than the OHâ»/•OH potential (+1.99 V vs. NHE) for hydroxyl radical generation [1] [15].

Computational studies using Møller-Plesset second-order perturbation theory (MP2) have provided quantitative insights into the thermochemical properties of ROS formation [15]. These calculations reveal that the transformation from triplet oxygen to singlet oxygen requires significant energy (ΔG = 126 kJ molâ»Â¹), while the reduction of oxygen to superoxide anion is energetically favorable (ΔG = -281 kJ molâ»Â¹) [15]. Such theoretical approaches complement experimental observations in understanding the relative stability and reactivity of different ROS in photocatalytic systems.

Advanced Computational Methods in Photocatalysis Research

Theoretical Modeling Approaches

Computational methods have become indispensable tools for elucidating photocatalytic mechanisms at the molecular level. Density Functional Theory (DFT) and time-dependent DFT (TDDFT) calculations provide insights into electronic structures, band gaps, and reaction pathways [16] [13]. Hybrid functionals such as HSE06 offer improved accuracy over standard local functionals by including a portion of exact Hartree-Fock exchange, better reproducing band gaps and excited-state properties [16].

Linear response time-dependent density functional theory (LR-TDDFT) has emerged as a particularly valuable method for investigating excited-state processes in photocatalytic systems [16]. For instance, LR-TDDFT simulations of water oxidation on rutile TiOâ‚‚ surfaces have revealed that Oâ‚‚ formation follows a thermocatalytic pathway occurring at room temperature, while Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ desorption is photocatalytic, requiring light to overcome a high-energy barrier [16]. This explains the experimental observation that Oâ‚‚ formation is typically more favorable in TiOâ‚‚ photocatalysis.

Advanced quantum chemical methods, including Møller-Plesset second-order perturbation theory (MP2), provide accurate thermochemical data for ROS formation pathways and stability [15]. These computational approaches enable researchers to map energetic profiles and predict favorable reaction pathways under various conditions.

Multiscale Modeling and Machine Learning

Multiscale modeling approaches integrate quantum mechanical calculations with kinetic models and macroscopic transport phenomena, providing a comprehensive understanding of photocatalytic processes across different length and time scales [13]. This hierarchical strategy optimizes resource distribution by applying appropriate computational methods to each scale of the problem.

Machine learning (ML) techniques are increasingly employed to accelerate photocatalyst discovery and optimization [13]. ML models can predict material properties, identify key performance descriptors, and guide the design of novel metal oxide compositions with enhanced photocatalytic activity. Quantum computing represents another emerging frontier, offering potential breakthroughs in solving complex quantum mechanical equations governing electronic and optical properties of photocatalytic materials [13].

Experimental Methodologies and Characterization

Quantum Efficiency Determination

Quantum efficiency represents a fundamental property of photocatalytic processes, defined as the number of target molecules converted per photon absorbed [17]. Accurate determination of quantum efficiency requires simultaneous solution of mass balance (to quantify reactant conversion) and radiation balance (to quantify photon absorption) within the reactor system [17].

Monte Carlo simulation methods have been developed to model the local volumetric rate of photon absorption (LVRPA) in photocatalytic reactors [17]. This approach tracks the trajectory of a statistically significant number of photons inside the reactor until they are either absorbed or scattered, recording the spatial location of absorbed photons. The method provides highly accurate results without introducing major simplifications, though it is computationally intensive [17].

Experimental protocols for quantum efficiency measurements typically involve:

- Synthesis and characterization of metal oxide photocatalysts with controlled properties

- Establishment of adsorption-desorption equilibrium in target compounds before irradiation

- Controlled irradiation with characterized light sources (UVA, visible, etc.)

- Sampling and analysis of reaction progress (e.g., via UV-Vis spectroscopy, TOC measurements)

- Photon flux determination using chemical actinometers (e.g., ferrioxalate actinometer)

- Calculation of quantum efficiency based on reactant conversion and absorbed photons [17]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Photocatalytic ROS Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Oxide Photocatalysts | Light absorption, charge generation, surface reactions | TiO₂ (P25), ZnO, Fe₂O₃, WO₃ nanoparticles [1] |

| Target Probe Compounds | ROS detection and quantification | Formic acid (minimal adsorption), Salicylic acid (strong adsorption) [17] |

| Sacrificial Reagents | Enhanced charge separation, increased photo-efficiency | Methanol, Naâ‚‚S, ethanol, Naâ‚‚SOâ‚„ [1] |

| Actinometers | Photon flux quantification | Ferrioxalate actinometer for light source characterization [17] |

| pH Modifiers | Reaction condition control, ROS speciation influence | Acids/bases for pH adjustment [15] |

| Dopants/Cocatalysts | Band gap engineering, charge separation enhancement | Transition metals, noble metals, graphite, graphene [1] |

| 7-Acetyl-5-fluoro-1H-indole | 7-Acetyl-5-fluoro-1H-indole | 7-Acetyl-5-fluoro-1H-indole (CAS 1221684-52-1) is a fluorinated indole building block for research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO) and not for human or veterinary use. |

| 1-(P-Tolyl)hex-5-EN-1-one | 1-(P-Tolyl)hex-5-EN-1-one, MF:C13H16O, MW:188.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Applications and Future Perspectives

The photocatalytic generation of ROS has enabled diverse applications in environmental remediation, energy production, and biomedical fields. In environmental contexts, ROS-driven oxidation processes effectively degrade organic pollutants, pesticides, and inorganic contaminants in wastewater [1] [18]. The strong oxidizing power of hydroxyl radicals, in particular, enables mineralization of persistent organic pollutants to COâ‚‚ and Hâ‚‚O.

Photocatalytic water splitting represents another significant application, where photogenerated electrons reduce H⺠to H₂ while corresponding holes oxidize H₂O to O₂ [1]. This process requires careful catalyst design to mitigate electron-hole recombination issues, often addressed through doping, heterojunction formation, or addition of sacrificial reagents [1].

Emerging applications include ROS-based therapies in biomedicine, where nanoplatforms generating controlled oxidative stress show promise for cancer treatment [15] [18]. The selective cytotoxicity of ROS enables targeted apoptosis of cancer cells while minimizing damage to healthy tissue.

Future research directions should address critical challenges in photocatalyst stability, scalability, and environmental compatibility [18]. The development of standardized ROS quantification protocols, computation-assisted material design, and large-scale fabrication methods will accelerate the translation of photocatalytic technologies from laboratory demonstrations to practical implementations [18]. Additionally, fundamental studies exploring the intricate relationships between metal oxide structure, surface properties, and ROS generation mechanisms will continue to drive innovation in this field.

Metal oxide semiconductors represent a cornerstone of modern photocatalytic research, driving advancements in environmental remediation, renewable energy, and sustainable chemistry. The efficacy of these materials is fundamentally governed by their intrinsic electronic structures and optical properties, particularly their bandgap energies, which determine the portion of the solar spectrum they can harness. Among the numerous metal oxides investigated, titanium dioxide (TiO₂), zinc oxide (ZnO), iron (III) oxide (Fe₂O₃), and tungsten trioxide (WO₃) have emerged as key players due to their favorable charge transport characteristics, tunable surface properties, and exceptional chemical stability.

This technical guide provides a systematic examination of these four pivotal metal oxides, framing their characteristics within the context of light absorption mechanisms crucial for photocatalytic applications. We present a detailed analysis of their crystal structures, intrinsic bandgap energies, and band edge positions, supplemented with experimentally-verified methodologies for their synthesis and characterization. The information herein is designed to serve researchers and scientists engaged in the rational design of photocatalytic systems, particularly those working at the intersection of materials science and environmental technology.

Fundamental Properties of Key Metal Oxides

Table 1: Fundamental Structural and Electronic Properties of Key Metal Oxides

| Material | Primary Crystal Structure(s) | Intrinsic Bandgap (eV) | Bandgap Nature | Key Characteristics & Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiOâ‚‚ | Anatase, Rutile, Brookite (Tetragonal) | 3.2 (Anatase), 3.0 (Rutile) [19] | Indirect (Anatase) | Highly stable, non-toxic, but rapid electron-hole recombination limits efficiency [20] [19]. |

| ZnO | Wurtzite (Hexagonal) | ~3.37 [21] [22] | Direct | Large exciton binding energy (~60 meV), but optical absorption is restricted to UV light [21] [22]. |

| Fe₂O₃ | Hematite (Rhombohedral) | 1.9 - 2.2 [22] | Indirect | Visible light absorption, widespread availability, but suffers from low electronic conductivity [22]. |

| WO₃ | Perovskite-like (Monoclinic) | 2.4 - 2.8 [23] | Indirect | Strong visible and near-infrared absorption, high photoconductivity, suitable for electrochromic devices [23]. |

The bandgap values for Fe₂O₃ and WO₃ are presented as ranges, reflecting the variability reported in the literature due to differences in synthesis methods, crystallinity, and nanoscale effects [23] [22]. The crystal structure directly influences charge carrier mobility and surface reactivity, making polymorph control a critical aspect of material synthesis.

Bandgap Engineering and Enhanced Photocatalytic Performance

A significant challenge with pristine metal oxides is their limited visible-light absorption. Bandgap engineering through doping and composite formation is a primary strategy to enhance their photocatalytic activity.

Table 2: Bandgap Modulation via Doping and Composite Formation

| Material | Engineering Strategy | Specific Example | Resulting Bandgap | Performance Enhancement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiOâ‚‚ | Co-doping with metals and non-metals | Al³âº/Al²⺠(2%) and Sâ¶âº (8%) co-doping [20] | 1.98 eV (from 3.23 eV) | 96.4% MB degradation in 150 min vs. 15% for pure TiOâ‚‚ [20]. |

| TiOâ‚‚ | Non-metal/Metal tri-doping | C, N, and Ni tri-doping (Computational) [19] | Significant reduction predicted | Emergence of mid-gap states, enhanced optical absorption in visible region [19]. |

| ZnO | Rare-earth ion doping | Eu³âº-doped ZnO Quantum Dots [24] | Tunable emission | Enhanced red emission; energy transfer from ZnO host to Eu³⺠ions [24]. |

| ZnO | Composite with narrow bandgap semiconductor | ZnO/Feâ‚‚O₃ nanocomposites [22] | N/A (Composite) | Superior photocatalytic and antimicrobial efficacy; efficient eâ»/h⺠separation [22]. |

| WO₃ | Doping and nanostructuring | Cr, Sn, Fe, S doping & nanostructure engineering [23] | Tunable within 2.4-2.8 eV range | Enhanced performance for water splitting, sensing, and electrochromic devices [23]. |

These strategies demonstrate that the optical absorption and, consequently, the photocatalytic efficiency of metal oxides can be profoundly altered through deliberate material design, pushing their functional boundaries into the visible light spectrum.

Experimental Protocols for Synthesis and Characterization

Detailed Synthesis Protocol: Hydrothermal Synthesis of Al/S Co-doped TiOâ‚‚ Nanoparticles

The following methodology is adapted from a documented procedure for enhanced visible-light photocatalysis [20].

Objective: To synthesize Al³âº/Al²⺠and Sâ¶âº co-doped TiOâ‚‚ nanoparticles with a modulated bandgap for improved photocatalytic degradation under visible light.

Materials (Research Reagent Solutions):

- Titanium Precursor: Titanium (III) chloride hexahydrate (TiCl₃·6H₂O), 99.999%.

- Dopant Sources: Aluminum (III) chloride hexahydrate (AlCl₃·6H₂O, 99.999%) and Thiourea (SC(NH₂)₂, 99.9%).

- Precipitation Agent: Sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 99.999%).

- Solvent: De-ionized water.

Procedure:

- Precursor Preparation: Dissolve 2 g of TiCl₃·6H₂O in 50 mL of deionized water using a magnetic stirrer for 30 minutes to ensure a homogeneous solution.

- NaOH Solution Preparation: Dissolve 0.5 g of NaOH in 20 mL of deionized water with stirring for 20 minutes.

- Co-precipitation: Add the NaOH solution dropwise to the TiCl₃ solution using a pipette. Allow the mixture to stand for 10 minutes at room temperature before resuming vigorous magnetic stirring for 50 minutes.

- Dopant Incorporation: For doped samples, add stoichiometric amounts of Aluminum nitrate nonahydrate (Al(NO₃)₃·9H₂O) and sodium sulfate (Na₂SO₄) to the Ti precursor solution. Adjust the pH of the final mixture to approximately 9 using ammonium hydroxide to facilitate uniform precipitation.

- Hydrothermal Reaction: Transfer the resulting solution into a 100 mL Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave. Heat the autoclave in an oven at 150°C for 24 hours, ensuring a controlled heating rate (e.g., 5°C/min).

- Post-processing:

- After reaction, cool the autoclave to room temperature.

- Centrifuge the resultant product and wash repeatedly with deionized water until the supernatant reaches a neutral pH of 7.

- Transfer the washed precipitate to a beaker and dry in an oven at 60°C for 24 hours.

- For crystallinity and dopant inclusion, calcine the dried powder at 500°C for 3 hours in air.

Key Characterization Workflow

The properties of synthesized metal oxides are typically validated through a series of characterization techniques. The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow from synthesis to functional assessment.

Diagram 1: Experimental characterization workflow for metal oxide photocatalysts.

Key Techniques:

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD): Determines crystalline phase, estimates crystallite size via Scherrer's equation, and detects lattice strain induced by dopants [20] [21].

- Raman Spectroscopy: Probes phase purity and lattice vibrations; peak shifts and broadening confirm successful dopant incorporation and resultant strain [20] [24].

- UV-Vis Spectroscopy: Measures the optical absorption edge. The bandgap is calculated using Tauc plots from the absorption data [20] [23].

- Photoluminescence (PL) Spectroscopy: Reveals information about charge carrier recombination dynamics. A reduction in PL intensity often indicates suppressed electron-hole recombination [20] [24].

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Confirms elemental composition, chemical states, and the successful incorporation of dopants into the host lattice [22] [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Metal Oxide Synthesis and Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Titanium (III) Chloride Hexahydrate (TiCl₃·6H₂O) | Precursor for TiO₂ synthesis, providing titanium ions. | Hydrothermal synthesis of TiO₂ nanoparticles [20]. |

| Zinc Acetate Dihydrate (Zn(CH₃COO)₂·2H₂O) | Common zinc precursor for wet-chemical synthesis of ZnO. | Synthesis of ZnO quantum dots and nanoparticles [24]. |

| Thiourea (SC(NHâ‚‚)â‚‚) | Source of sulfur (Sâ¶âº) for non-metal doping. | Co-doping of TiOâ‚‚ to create oxygen vacancies and reduce bandgap [20]. |

| Ammonium Hydroxide (NHâ‚„OH) | pH regulator in precipitation and hydrothermal synthesis. | Used to adjust pH to ~9 for uniform precipitation during doping [20]. |

| Oleylamine (Câ‚₈H₃₇N) | Surfactant and stabilizing agent in nanomaterial synthesis. | Used in the synthesis of Eu³âº-doped ZnO QDs to control growth and prevent aggregation [24]. |

| Methylene Blue (Câ‚₆Hâ‚₈ClN₃S) | Model organic pollutant for evaluating photocatalytic activity. | Standard dye for testing degradation efficiency under visible light [20] [22]. |

| (S)-2-Isobutylsuccinic acid | (S)-2-Isobutylsuccinic acid, CAS:63163-11-1, MF:C8H14O4, MW:174.19 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| N-Formyl tranexamic acid | N-Formyl Tranexamic Acid|CAS 1599413-49-6|RUO | N-Formyl Tranexamic Acid, a Tranexamic Acid impurity (CAS 1599413-49-6). For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

TiO₂, ZnO, Fe₂O₃, and WO₃ form a versatile portfolio of metal oxide semiconductors, each with distinct structural and electronic properties that dictate their applicability in photochemical processes. While their intrinsic wide bandgaps pose a limitation, the strategic implementation of doping and composite formation provides a powerful pathway for bandgap modulation and functional enhancement. The experimental protocols and characterization workflows outlined in this guide provide a foundational framework for researchers to synthesize, modify, and validate these materials. The ongoing research, as evidenced by the latest studies, continues to refine these strategies, pushing the boundaries toward highly efficient, visible-light-driven photocatalytic systems for a sustainable future.

The efficiency of photocatalytic processes in transition metal oxides (TMOs)—ranging from pollutant degradation and CO₂ reduction to renewable energy generation—is fundamentally governed by their electronic transition characteristics. When photon energy interacts with a photocatalytic material, electrons undergo transitions between different energy states, primarily through two distinct mechanisms: charge-transfer (CT) transitions and d-d transitions. These transitions dictate how effectively a material harnesses solar energy, particularly in metal oxide systems where the interplay between metal centers and ligand environments creates unique optical properties. Understanding these electronic transitions is crucial for designing advanced photocatalytic systems that optimize solar energy conversion across the electromagnetic spectrum, from ultraviolet to infrared regions.

The strategic engineering of these transitions enables researchers to overcome inherent limitations in classic TMOs such as TiO₂, ZnO, and WO₃, which typically suffer from wide bandgaps restricting light absorption to ultraviolet regions, rapid charge carrier recombination, and poor electrical conductivity. Recent advances demonstrate that manipulation of charge transfer pathways and d-d transition characteristics can significantly enhance photocatalytic performance, providing a foundation for next-generation environmental and energy technologies.

Fundamental Concepts of Electronic Transitions

d-d Transitions

d-d transitions represent electronic excitations between molecular orbitals that are predominantly metal in character—specifically, between the crystal field-split d-orbitals of a transition metal ion in a coordination complex. These transitions occur when an electron moves from one d-orbital to another within the same metal center, typically in octahedral or tetrahedral coordination environments. For instance, in octahedral complexes, d-d transitions occur between the tâ‚‚g and e_g orbitals across the crystal field splitting energy (Δ). A crucial characteristic of d-d transitions is that they are only possible in metal ions with partially filled d-orbitals (d¹ to dâ¹ configurations); they cannot occur in systems with completely empty (dâ°) or completely full (d¹â°) d-orbitals [25].

These transitions are classified as "parity-forbidden" due to the same angular momentum quantum number of the initial and final orbitals, resulting in relatively weak absorption bands with molar extinction coefficients (ε) typically below 1,000 Mâ»Â¹cmâ»Â¹ [25]. However, in certain coordination environments where strong p-d orbital coupling occurs between metal centers and coordinating groups—such as in hydrotalcite-like hydroxy salts—this forbidden character can be partially lifted, enabling d-d transitions to contribute significantly to light absorption, even in the infrared region [26].

Charge-Transfer Transitions

In contrast to d-d transitions, charge-transfer (CT) transitions involve electron movement between orbitals that are predominantly localized on different chemical species—typically from ligand to metal or metal to ligand. These transitions are classified into two primary categories [27] [25]:

Ligand-to-Metal Charge Transfer (LMCT): Electrons transition from molecular orbitals primarily associated with ligands to those primarily associated with the metal center. This occurs most readily when metals are in high oxidation states with low-energy empty d-orbitals, combined with ligands possessing high-energy filled orbitals (e.g., π-donor ligands like oxo or halo ligands) [27].

Metal-to-Ligand Charge Transfer (MLCT): Electrons transition from molecular orbitals primarily associated with the metal center to those primarily associated with the ligands. This is favored when metals are in low oxidation states with high-energy filled d-orbitals, combined with ligands possessing low-energy empty π* orbitals [27] [25].

Charge-transfer transitions are both spin- and Laporte-allowed, resulting in intense absorption bands with extinction coefficients (ε) typically much greater than 1,000 Mâ»Â¹cmâ»Â¹â€”often orders of magnitude stronger than d-d transitions [27] [25]. These transitions are frequently responsible for the intense colors observed in many coordination compounds and play a crucial role in photocatalytic applications by facilitating efficient light harvesting and charge separation.

Table 1: Comparative Characteristics of d-d and Charge-Transfer Transitions

| Characteristic | d-d Transitions | Charge-Transfer Transitions |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Nature | Within metal-centered d-orbitals | Between ligand and metal orbitals |

| Spectral Intensity | Weak (ε < 1,000 Mâ»Â¹cmâ»Â¹) | Strong (ε > 1,000 Mâ»Â¹cmâ»Â¹) |

| Selection Rules | Parity-forbidden | Spin- and Laporte-allowed |

| Metal Requirements | Partially filled d-orbitals (d¹-dâ¹) | Dependent on oxidation state and ligand type |

| Spectral Range | Often visible region | UV to visible region |

| Ligand Dependence | Dependent on field strength | Dependent on π-donor/acceptor properties |

| Solvent Effects | Generally minimal | Often solvatochromic |

Experimental Characterization Methodologies

Spectroscopic Techniques

The characterization of electronic transitions in photocatalytic materials employs several sophisticated spectroscopic techniques that provide insights into both thermodynamic and kinetic aspects of electron transfer processes.

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) Spectroscopy serves as the fundamental tool for identifying electronic transitions through absorption measurements. This technique enables researchers to determine bandgap energies via Tauc plot analysis and distinguish between d-d and CT transitions based on their characteristic intensities and spectral positions. CT transitions typically manifest as intense, broad bands in the UV-visible region, while d-d transitions appear as weaker features, often in the visible region [27] [28]. For metal oxides, diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (DRS) is particularly valuable for powdered samples, allowing bandgap determination for photocatalytic suitability assessment.

Femtosecond Transient Absorption (fs-TA) Spectroscopy represents a more advanced approach for investigating the dynamics of photogenerated charge carriers. This pump-probe technique employs ultrafast laser pulses to trigger electronic transitions with a pump beam and subsequently probes the excited state dynamics with a time-delayed probe beam [29]. The methodology involves:

Sample Excitation: A femtosecond pump pulse (typically visible light) excites the sample, promoting electrons to higher energy states.

Time-Delayed Probing: A delayed probe pulse (visible, near-infrared, mid-infrared, or terahertz) monitors absorption changes as a function of time delay.

Signal Detection: The absorption difference (ΔA) between pumped and unpumped conditions is measured: ΔA = Apump-on − Apump-off = lg(Ipump-off/Ipump-on), where Ipump-on and Ipump-off represent detected light intensities with and without pump excitation [29].

Kinetic Analysis: Characteristic signals including Ground State Bleaching (GSB), Stimulated Emission (SE), and Excited State Absorption (ESA) are analyzed to extract kinetic information about charge separation, recombination, and transfer processes across femtosecond to second timescales [29].

This technique has proven invaluable for studying carrier dynamics in semiconductor photocatalysts such as CdS, TiO₂, g-C₃N₄, BiVO₄, perovskites, and metal-organic framework (MOF) composites, providing direct insight into the charge separation efficiencies that ultimately determine photocatalytic performance [29].

X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy techniques, including X-ray Absorption Near Edge Structure (XANES) and Extended X-ray Absorption Fine Structure (EXAFS), provide element-specific information about oxidation states and local coordination environments around metal centers. These methods are particularly useful for characterizing the active sites in transition metal oxide catalysts and monitoring their evolution during catalytic processes [26].

Theoretical Modeling Approaches

Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations provide complementary theoretical insights into electronic structure and transition mechanisms. DFT enables the prediction of density of states (DOS), band structures, and optical absorption spectra, facilitating the interpretation of experimental observations. For example, DFT simulations of two-dimensional hydrotalcite-like hydroxy salts have revealed splitting d orbitals within band gaps that enable normally parity-forbidden d-d transitions under infrared light irradiation [26]. These calculations typically involve:

- Model Construction: Building atomic-scale models of photocatalytic materials, often with specific surface terminations.

- Electronic Structure Calculation: Determining band structures, density of states, and projected density of states.

- Optical Property Prediction: Computing theoretical absorption spectra and transition probabilities.

- Reaction Pathway Modeling: Calculating Gibbs free energy diagrams for catalytic processes.

Table 2: Key Experimental Techniques for Studying Electronic Transitions

| Technique | Information Obtained | Applications in Photocatalysis Research |

|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis Spectroscopy | Bandgap energy, transition energies and intensities | Initial material screening, bandgap engineering studies |

| Femtosecond Transient Absorption | Charge carrier dynamics, recombination rates, lifetimes | Mechanism elucidation, material optimization |

| X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy | Oxidation states, local coordination environments | Active site characterization, structural evolution |

| Photoluminescence Spectroscopy | Charge recombination processes, defect states | Quality assessment, recombination center identification |

| DFT Calculations | Electronic structure, theoretical spectra, transition pathways | Mechanism verification, material design |

Electronic Transitions in Metal Oxide Photocatalysts: Mechanisms and Applications

Charge Transfer Transitions in Photocatalytic Systems

Charge transfer transitions play a pivotal role in enhancing the photocatalytic performance of metal oxide systems by improving light absorption and facilitating charge separation. In transition metal oxide/graphene oxide (TMO/GO) nanocomposites, CT transitions between the TMO and GO components significantly enhance charge separation efficiency, thereby improving photocatalytic dye degradation and energy storage capabilities [30]. For instance, Fe-doped Co₃O4/GO composites exhibit enhanced visible-light absorption through CT transitions, leading to improved photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants.

In metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), strategic introduction of cluster-to-metal charge transfer transitions has been employed to enhance photocatalytic performance. For example, transition metal-modified UiO-66-NH₂ MOFs exhibit significantly enhanced photocatalytic degradation of bisphenol A in the presence of peroxymonosulfate under visible light irradiation [31]. Embedding Fe ions into UiO-66-NH₂ not only modifies the band structure but also dramatically boosts visible light absorption through enhanced charge transfer characteristics. The resulting materials demonstrate exceptional photocatalytic activity, achieving complete degradation of bisphenol A within 60 minutes—significantly outperforming unmodified counterparts.

Two-dimensional transition metal oxides (2D TMOs) leverage their unique electronic structures to facilitate efficient charge transfer processes. Materials such as WO₃, MoO₃, and V₂O₅ exhibit bandgap energies between 2.6 and 3.0 eV, enabling better visible light absorption compared to conventional TiO₂ and ZnO [32]. The 2D planar configuration of these materials promotes dominant exposure of specific crystal facets with distinct atomic arrangements that enhance charge separation and utilization of photons through optimized band bending at the catalyst-electrolyte interface [32].

d-d Transitions in Photocatalytic Applications

While traditionally considered less efficient for photocatalysis due to their forbidden nature, d-d transitions have recently been exploited in innovative photocatalytic systems. In ultrathin Cu-based hydrotalcite-like hydroxy salts, strong p-d orbital coupling between coordinating groups and metal ions leads to degeneracy of valence band d orbitals, creating empty d orbitals within the band gap that serve as "cushion steps" for sequential d-d transitions [26]. This mechanism enables unexpected photocatalytic activity under infrared light irradiation, which normally possesses insufficient energy for direct bandgap excitation.

For example, Cuâ‚„(SOâ‚„)(OH)₆ nanosheets exhibit excellent activity for IR light-driven COâ‚‚ reduction, with production rates of 21.95 μmol gâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹ for CO and 4.11 μmol gâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹ for CHâ‚„, surpassing most reported catalysts under similar conditions [26]. This exceptional performance is achieved through a cascaded electron transfer process based on d-d orbital transitions, where electrons first transition from filled to empty d orbitals using IR photons, then subsequently absorb additional IR photons to reach the conduction band and participate in reduction reactions. Similar behavior has been observed in related Cu-based systems including Cuâ‚‚(NO₃)(OH)₃, Cu₃(POâ‚„)(OH)₃, and Cuâ‚‚(CO₃)(OH)â‚‚ nanosheets, demonstrating the generality of this approach for accessing normally inaccessible regions of the solar spectrum.

Synergistic Effects in Advanced Photocatalytic Systems

Advanced photocatalytic materials often exploit both charge-transfer and d-d transitions to achieve broad-spectrum solar energy harvesting. In multifunctional transition metal oxide/graphene oxide nanocomposites, synergistic effects between these transition mechanisms enable simultaneous photocatalytic dye degradation and energy storage applications [30]. For example, Fe-doped Co₃Oâ‚„ systems leverage both the Co²âº/Co³⺠and Fe³⺠redox couples through charge transfer processes while simultaneously benefiting from d-d transitions that enhance visible light absorption.

Heterojunction engineering represents another strategic approach for optimizing electronic transitions in photocatalytic systems. By constructing interfaces between different semiconductors with aligned band structures, researchers can create internal electric fields that enhance charge separation while maintaining efficient light absorption through both CT and d-d transitions. For instance, Co₃O₄-coated TiO₂ core-shell structures establish p-n junctions that improve charge separation while maintaining UV-driven photocatalytic activity, achieving nearly 100% degradation of methylene blue within 1.5 hours compared to 80% for unmodified TiO₂ [30].

Table 3: Performance of Selected Photocatalytic Systems Leveraging Different Electronic Transitions

| Photocatalytic System | Primary Transition Mechanism | Application | Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fe-UiO-66-NHâ‚‚ | Cluster-to-metal charge transfer | Bisphenol A degradation | Complete degradation in 60 min [31] |

| Cuâ‚„(SOâ‚„)(OH)₆ nanosheets | d-d transitions | IR-driven COâ‚‚ reduction | 21.95 μmol gâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹ CO, 4.11 μmol gâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹ CHâ‚„ [26] |

| Co₃O₄/TiO₂ core-shell | Charge transfer + heterojunction | Methylene blue degradation | ~100% degradation in 1.5 h (vs. 80% for TiO₂) [30] |

| Fe-doped Co₃Oâ‚„/GO | Charge transfer + d-d transitions | Dye degradation + supercapacitors | Specific capacitance: 588.5 F gâ»Â¹ [30] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The investigation and optimization of electronic transitions in photocatalytic metal oxides requires specialized reagents and materials tailored to specific synthetic and characterization needs. The following table summarizes key research reagents and their functions in studying charge-transfer and d-d transitions.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Electronic Transition Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Transition Metal Salts (e.g., FeCl₃·6H₂O, CoCl₂·6H₂O, NiCl₂·6H₂O) | Metal ion precursors for catalyst synthesis | Modifying UiO-66-NH₂ to enhance cluster-to-metal charge transfer [31] |

| Peroxymonosulfate (PMS) | Oxidant for sulfate radical-based advanced oxidation processes | Studying charge transfer-enhanced pollutant degradation [31] |

| N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) | Solvent for solvothermal synthesis | MOF synthesis and transition metal modification [31] |

| 2-Aminoterephthalic Acid | Organic linker for MOF synthesis | Constructing UiO-66-NHâ‚‚ frameworks [31] |

| Graphene Oxide | Support material for nanocomposites | Enhancing charge separation in TMO/GO systems [30] |

| Isopropyl Alcohol (IPA) | Hydroxyl radical scavenger | Mechanistic studies of radical species in photocatalysis [31] |

| tert-Butyl Alcohol (TBA) | Hydroxyl and sulfate radical scavenger | Probing reaction mechanisms in SR-AOPs [31] |

| Ethylene Diamine Tetraacetic Acid (EDTA) | Hole scavenger | Investigating hole-mediated oxidation pathways [31] |

| AgNO₃ | Electron scavenger | Studying electron transfer pathways [31] |

| (3-iodopropoxy)Benzene | (3-iodopropoxy)Benzene, MF:C9H11IO, MW:262.09 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 8-Methylnona-1,7-dien-5-yne | 8-Methylnona-1,7-dien-5-yne|C10H14|CAS 89454-85-3 | 8-Methylnona-1,7-dien-5-yne (C10H14) is a high-purity reference standard for research. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO) and is not intended for personal use. |

The strategic manipulation of charge-transfer and d-d transitions represents a powerful approach for enhancing the photocatalytic performance of transition metal oxide materials. While charge-transfer transitions offer intense, allowed transitions that efficiently harvest light and facilitate charge separation, d-d transitions—though inherently weaker—provide opportunities for exploiting otherwise inaccessible regions of the solar spectrum, particularly in the infrared region. The continued development of advanced characterization techniques, particularly femtosecond transient absorption spectroscopy, enables unprecedented insights into the ultrafast dynamics of these electronic processes, guiding rational material design.

Future research directions will likely focus on the precise engineering of electronic structures through defect control, heterojunction formation, and molecular-level integration of complementary components to optimize both charge-transfer and d-d transition characteristics. Additionally, the exploration of novel material systems such as two-dimensional hydrotalcite-like hydroxy salts and multivariate MOFs presents exciting opportunities for achieving unprecedented control over electronic transitions. As our fundamental understanding of these processes deepens, we can anticipate the development of increasingly efficient photocatalytic systems that maximize solar energy utilization across the entire spectral range, addressing critical challenges in environmental remediation and renewable energy generation.

Engineering Light Absorption: Strategic Design and Synthesis for Enhanced Performance