Harnessing Inorganic Photocatalysts for Advanced Sterilization: Mechanisms, Applications, and Future Frontiers in Biomedicine

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of photocatalytic sterilization using inorganic compounds, a promising green technology for combating pathogenic microorganisms.

Harnessing Inorganic Photocatalysts for Advanced Sterilization: Mechanisms, Applications, and Future Frontiers in Biomedicine

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of photocatalytic sterilization using inorganic compounds, a promising green technology for combating pathogenic microorganisms. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental mechanisms of reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and microbial inactivation. The scope extends to the design of advanced photocatalysts like TiO2 and silver composites, their application in water disinfection and surface sterilization, and the critical parameters for optimizing performance. The review also covers advanced validation techniques and comparative analyses with conventional methods, concluding with future directions for clinical translation and the development of novel, visible-light-activated materials to address current commercialization challenges.

The Fundamental Principles of Photocatalytic Sterilization

Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

Photocatalytic sterilization represents an advanced oxidation process (AOP) that utilizes light-activated semiconductor materials to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) capable of inactivating microorganisms and degrading organic pollutants. This process operates under mild conditions and can utilize natural sunlight, making it an energy-efficient and cost-effective approach for disinfection applications [1].

The fundamental mechanism begins when a photocatalyst, typically a semiconductor, absorbs photons with energy equal to or greater than its band gap (Eg). This absorption excites an electron (e-) from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB), creating a positively charged hole (h+) in the valence band. The narrowness of the band gap directly influences the generation of these electron-hole pairs [1].

For effective sterilization, the recombination of these electron-hole pairs must be minimized through strategies such as doping, introducing surface defects, or coupling with other catalysts. The excited electrons in the conduction band act as reductants, while the holes in the valence band facilitate oxidation. These species then react with water and oxygen to generate ROS, including hydroxyl radicals (•OH) and superoxide anions (O2•-), which drive the degradation of microbial cellular components and organic pollutants [1].

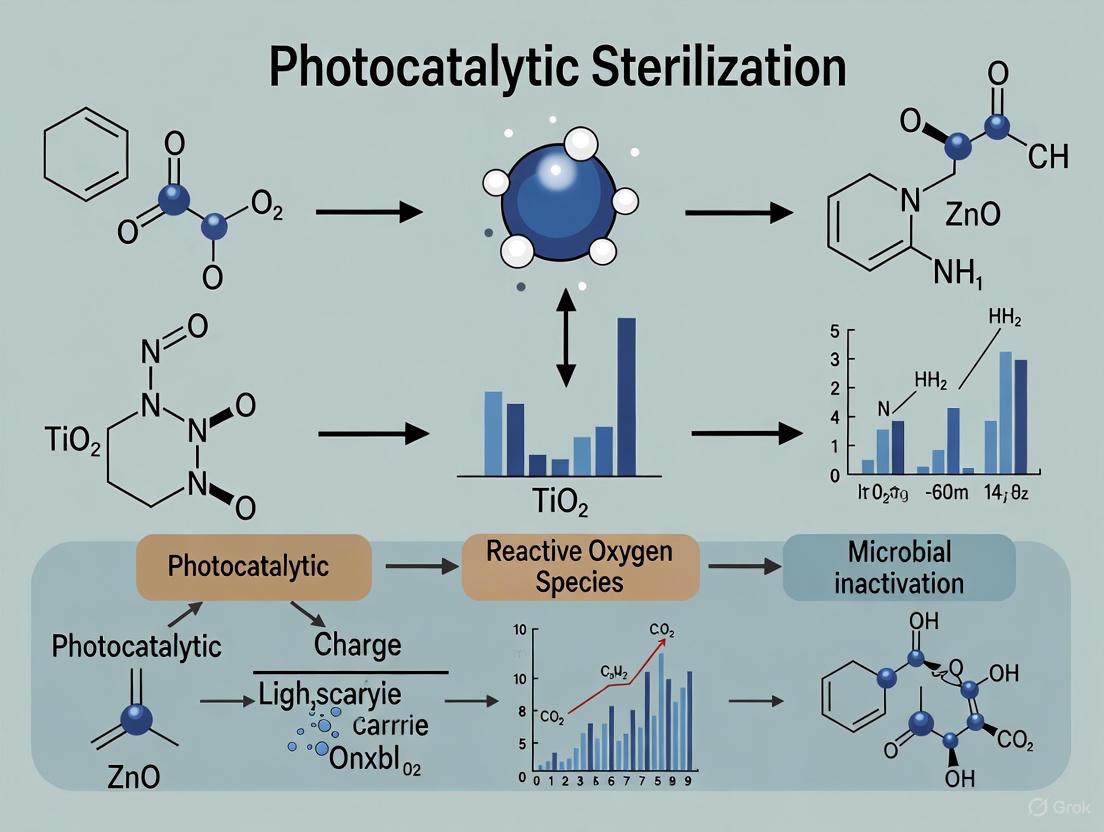

Figure 1: Photocatalytic sterilization mechanism showing ROS generation.

Current Market Landscape and Applications

The global market for photocatalytic technologies demonstrates robust growth, reflecting increasing adoption across multiple sectors. The photocatalytic sterilization module market specifically was valued at $8.79 billion in 2025 and is projected to reach $19.11 billion by 2033, growing at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 13.82% [2]. Similarly, the broader photocatalysts market shows parallel expansion, expected to grow from $3.0 billion in 2025 to $5.9 billion by 2032 at a CAGR of 10.1% [3].

| Market Segment | 2025 Value (USD Billion) | Projected 2032/2033 Value (USD Billion) | CAGR (%) | Dominant Region/Share |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Photocatalytic Sterilization Module [2] | 8.79 | 19.11 (2033) | 13.82 | Asia Pacific (65%) |

| Photocatalysts (Overall Market) [3] | 3.0 | 5.9 (2032) | 10.1 | Asia Pacific (65%) |

Regional adoption patterns highlight Asia Pacific as the dominant market, accounting for approximately 65% of global photocatalyst consumption [3]. This leadership is driven by rapid industrialization, urbanization, and strong governmental support for environmental technologies, particularly in Japan, China, and South Korea [2] [3]. North America represents the fastest-growing regional market, supported by $71 billion in clean energy investments and stringent environmental regulations [3].

Application diversity continues to expand across sectors. The building materials segment leads with a 58% market share, incorporating self-cleaning and air-purifying functionalities [3]. The automotive sector demonstrates the fastest growth, integrating photocatalytic air purification systems to meet emission regulations and consumer demands for improved cabin air quality [3]. Healthcare, water treatment, and air purification constitute other significant application areas [2] [1].

Key Operational Parameters and Optimization

Photocatalytic sterilization efficiency depends critically on several operational parameters that must be optimized for maximum performance:

- Contact Time and Catalyst Dose: Longer exposure enhances pollutant removal until saturation, while excessive catalyst loading can reduce efficiency due to light scattering and particle aggregation [1].

- Light Intensity and Wavelength: While UV light is most commonly used, recent research focuses on developing visible-light-active catalysts to reduce energy costs. Visible light activation significantly enhances practical applicability [1] [3].

- Solution pH: The pH affects the photocatalyst surface charge and degradation pathways. When pH is below the point of zero charge (PZC), the surface becomes positively charged, attracting anionic pollutants, while pH above PZC creates a negative surface that attracts cationic pollutants [1].

- Temperature: Most reactions occur at room temperature, but temperatures below 0°C slow reaction rates, while excessively high temperatures can degrade the photocatalyst. Moderate temperatures generally accelerate reaction kinetics [1].

- Oxidizing Agents: These can improve degradation by promoting ROS formation but require careful concentration control as excessive amounts could break down the catalyst [1].

- Inorganic Ions and Pollutant Concentration: In real wastewater systems, inorganic ions may interfere by scavenging reactive species or occupying active sites. Higher pollutant concentrations typically hinder degradation due to reduced light penetration [1].

Table 2: Key Parameters Affecting Photocatalytic Efficiency

| Parameter | Optimal Condition | Effect on Process | Considerations for Scaling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Type | Modified TiOâ‚‚ (visible light) | Band gap determines activation energy; doping reduces recombination | Cost, stability, and reusability are critical |

| Light Source | Visible spectrum (sunlight) | UV: higher energy but costly; Visible: sustainable but lower energy | Solar irradiation maximizes economic viability |

| pH Level | Dependent on pollutant & catalyst PZC | Affects catalyst surface charge and pollutant adsorption | Requires adjustment for different wastewater streams |

| Catalyst Loading | System-dependent optimum | Excess causes light scattering & reduced penetration | Optimization needed for each reactor configuration |

| Temperature | Room to moderate (e.g., 20-40°C) | Higher temperatures enhance kinetics but may destabilize catalyst | Often controlled by ambient conditions in large-scale applications |

| Reaction Time | Contaminant-dependent | Longer times increase degradation but reduce throughput | Balance between efficiency and processing capacity |

Experimental Protocols for Photocatalytic Sterilization

Protocol 1: Standard Laboratory-Scale Bacterial Inactivation Assay

Objective: To evaluate the efficacy of a photocatalyst in inactivating model microorganisms (e.g., Escherichia coli) under controlled illumination.

Materials:

- Photocatalyst powder (e.g., TiOâ‚‚ P25, ZnO, or modified visible-light catalyst)

- Bacterial suspension (e.g., E. coli ATCC 25922 in nutrient broth, mid-log phase)

- Photoreactor system with light source (e.g., Xenon lamp with appropriate filters)

- Magnetic stirrer

- Serial dilution apparatus and nutrient agar plates

- Colony counter

Methodology:

- Catalyst Preparation: Prepare a suspension of the photocatalyst in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at a concentration of 0.1-1.0 g/L. Sonicate for 15 minutes to ensure dispersion.

- Microbial Inoculation: Add the bacterial suspension to the catalyst suspension to achieve an initial concentration of approximately 10ⶠCFU/mL.

- Dark Adsorption Phase: Place the mixture in the photoreactor and stir in darkness for 30 minutes to establish adsorption-desorption equilibrium.

- Illumination Phase: Turn on the light source while maintaining continuous stirring. Withdraw aliquots (1 mL) at predetermined time intervals (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 60, 120 minutes).

- Sample Analysis: Serially dilute aliquots, plate on nutrient agar, and incubate at 37°C for 24 hours. Count viable colonies and calculate log reduction.

- Control Experiments: Perform identical tests with (a) no catalyst, (b) no light, and (c) both catalyst and light to confirm photocatalytic effect.

Protocol 2: Advanced Visible-Light Photocatalyst Performance Evaluation

Objective: To assess the sterilization performance of a novel visible-light-active photocatalyst and identify optimal operational parameters.

Materials:

- Visible-light-active photocatalyst (e.g., nitrogen-doped TiOâ‚‚, composite material)

- Simulated wastewater containing target pollutants and inorganic ions

- LED light source (wavelength > 420 nm) with calibrated irradiance

- Spectrophotometer or HPLC for pollutant concentration analysis

- Reactive oxygen species detection probes (e.g., nitroblue tetrazolium for O₂•â», terephthalic acid for •OH)

Methodology:

- Experimental Matrix Setup: Design a multifactorial experiment varying catalyst loading (0.1-1.0 g/L), pH (5-9), and light intensity.

- ROS Detection: Incorporate specific scavengers (e.g., isopropanol for •OH, benzoquinone for O₂•â») to identify the primary reactive species responsible for inactivation.

- Kinetic Analysis: Monitor microbial inactivation and pollutant degradation kinetics. Fit data to appropriate models (e.g., pseudo-first-order kinetics).

- Catalyst Reusability: After each experiment, recover the catalyst through centrifugation, wash thoroughly, and test for five consecutive cycles to assess stability.

- Characterization: Analyze fresh and used catalysts using XRD, SEM, and BET surface area analysis to correlate performance with structural properties.

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for photocatalytic sterilization assays.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful photocatalytic sterilization research requires carefully selected materials and characterization tools. The selection of appropriate photocatalysts, microorganisms, and analytical methods is crucial for generating reliable, reproducible data.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Photocatalytic Sterilization

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Semiconductor Photocatalysts | Primary light-activated material generating ROS | TiO₂ (P25 Degussa), ZnO, WO₃, g-C₃N₄; particle size <100 nm preferred |

| Dopants/Co-catalysts | Enhance visible light absorption and reduce charge recombination | Nitrogen, sulfur, graphene, noble metals (Pt, Ag) |

| Model Microorganisms | Standardized strains for evaluating biocidal efficacy | E. coli (ATCC 25922), S. aureus (ATCC 25923), B. subtilis (spores) |

| Culture Media | Microbial propagation and viability assessment | Nutrient broth/agar, LB medium; prepared per manufacturer specifications |

| ROS Detection Probes | Identify and quantify reactive oxygen species | Nitroblue tetrazolium (O₂•â»), terephthalic acid (•OH), DPBF (singlet oxygen) |

| Analytical Instruments | Quantify microbial inactivation and pollutant degradation | UV-Vis spectrophotometer, HPLC, colony counter, fluorescence microscope |

| Light Sources | Provide controlled irradiation for photoactivation | Xenon lamp (solar simulator), LED arrays (specific wavelengths), UV lamps |

Titanium dioxide (TiOâ‚‚) continues to dominate research applications with over 80% market share in the photocatalysts product segment due to its proven effectiveness, chemical stability, and extensive commercial validation [3]. Recent innovations focus on modified TiOâ‚‚ formulations that operate under fluorescent and natural lighting conditions, improving performance by up to 30% according to studies cited in the Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering [3].

The incorporation of nanotechnology through materials such as graphene and nanoscale TiOâ‚‚ has dramatically improved photocatalytic performance and enabled new applications. Japanese companies like TOTO Ltd. and Ishihara Sangyo Kaisha have pioneered breakthrough technologies with products demonstrating significant antiviral and antibacterial activity under indoor lighting conditions, revolutionizing applications in healthcare facilities and public spaces [3].

Semiconductor-based photocatalytic sterilization represents a promising green technology for microbial inactivation. The core mechanism initiates with photoexcitation, where semiconductors absorb photons with energy equal to or greater than their bandgap energy, prompting electron (eâ») transitions from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB). This process generates positively charged holes (hâº) in the valence band, creating electron-hole pairs [4].

The resulting charge carriers undergo separation and migration to the semiconductor surface, where they participate in redox reactions. The holes are powerful oxidants that can directly attack microbial cells or react with water or hydroxide ions to generate hydroxyl radicals (·OH). Simultaneously, the electrons typically reduce molecular oxygen (Oâ‚‚) adsorbed on the surface, forming superoxide anion radicals (·Oâ‚‚â») and other reactive oxygen species (ROS) [4]. These highly reactive oxygen species are primarily responsible for the oxidative destruction of microbial components, including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, leading to effective sterilization [5] [4].

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Generation Pathways

The generation of various Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) is critical to the efficacy of photocatalytic sterilization. Table 1 summarizes the primary ROS, their formation pathways, and oxidative potentials.

Table 1: Primary Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in Photocatalysis

| ROS Species | Formation Pathway | Oxidative Potential (V vs. NHE) | Role in Sterilization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxyl Radical (·OH) | h⺠+ H₂O/OH⻠→ ·OH | +2.8 [6] | Non-selectively oxidizes cell membranes, proteins, and DNA [4]. |

| Superoxide Anion (·Oâ‚‚â») | eâ» + Oâ‚‚ → ·Oâ‚‚â» | -0.33 [7] | Initiates destructive chain reactions within microbial cells [7]. |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) | ·O₂⻠+ 2H⺠+ e⻠→ H₂O₂ 2h⺠+ 2H₂O → H₂O₂ [7] | +1.78 | Acts as a stable precursor for other ROS, penetrating and damaging cells. |

| Singlet Oxygen (¹O₂) | Energy transfer to O₂ [7] | +1.48 | Selective oxidation of biomolecules, contributes to toxin degradation [7]. |

The following diagram illustrates the sequential pathways of ROS generation following semiconductor photoexcitation:

Quantitative Analysis of Key Photocatalytic Semiconductors

The performance of a semiconductor in photocatalytic sterilization is governed by its intrinsic electronic and structural properties. Table 2 compares key parameters of several prominent inorganic semiconductors, including traditional and emerging bismuth-based materials known for their visible-light activity.

Table 2: Properties of Key Inorganic Semiconductor Photocatalysts

| Semiconductor | Bandgap (eV) | Light Response Range | Key ROS Generated | Reported Antimicrobial Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiOâ‚‚ (Anatase) | 3.2 [5] | Ultraviolet | ·OH, ·Oâ‚‚â», Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ | Effective against >20 Gram-± bacteria, viruses, fungi [5] |

| Bi₂O₃ | 2.0 - 3.96 [5] | Visible Light | ·OH, ·O₂⻠| Promising performance in visible-light antifouling coatings [5] |

| WO₃ | ~2.7 | Visible Light | ·OH, ·O₂⻠| Enhanced activity via oxygen vacancy engineering [8] |

| g-C₃Nâ‚„ | ~2.7 [9] | Visible Light | ·OH, ·Oâ‚‚â», Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ | High compatibility for heterojunctions; COâ‚‚ reduction [9] |

| CdS | ~2.4 | Visible Light | ·OH, ·O₂⻠| Suffers from photo-corrosion (Cd-O bond formation) [9] |

Experimental Protocol: Quantifying Hydroxyl Radicals via Electrochemical Detection

Accurately quantifying ROS generation is essential for evaluating and developing efficient photocatalysts. The following protocol details a modern electrochemical method for in-situ monitoring of hydroxyl radicals (·OH) using coumarin as a probe molecule, addressing limitations of traditional fluorescence techniques [6].

Principle

Coumarin reacts with photogenerated ·OH radicals to form various mono-hydroxylated products (e.g., 7-hydroxycoumarin, 6-hydroxycoumarin). An electrochemical method detects all main mono-hydroxylated products, providing a more comprehensive and representative quantification of ·OH yield compared to fluorescence spectroscopy, which only detects fluorescent products like 7-hydroxycoumarin [6].

Materials and Reagents

- Photocatalyst: e.g., TiOâ‚‚ P25 (Evonik Degussa) [6].

- Probe Molecule: Coumarin (≥99% purity) [6].

- Solvent: Phosphate Buffer (1.0 M, pH ~7), prepared from potassium phosphate salts [6].

- Hydroxylated Coumarin Standards: 3-, 4-, 5-, 6-, 7-, 8-hydroxycoumarin for calibration [6].

- Equipment: Electrochemical workstation, three-electrode system (working, counter, reference), photocatalytic reactor, UV-LED light source (365-370 nm), magnetic stirrer [6].

Procedure

- Reaction Setup: In a borosilicate glass beaker, add 100 mL of phosphate buffer, coumarin (typical concentration 100-1000 μM), and 50 mg of photocatalyst [6].

- Adsorption Equilibrium: Stir the suspension in the dark for 30-60 minutes to establish adsorption-desorption equilibrium.

- Photocatalytic Reaction: Initiate irradiation with the UV-LED strip while maintaining constant stirring.

- In-Situ Electrochemical Monitoring:

- Immerse the electrochemical cell electrodes directly into the reacting suspension.

- Apply a potential scan (e.g., Differential Pulse Voltammetry) from 0.3 V to 1.1 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) to oxidize the hydroxylated coumarin products.

- Record voltammograms at regular time intervals (e.g., every 5-10 minutes). The cumulative peak area of the oxidation signals corresponds to the total concentration of mono-hydroxylated products, which is proportional to the ·OH generated [6].

- Data Analysis: Quantify the total ·OH radical yield using a calibration curve constructed from the hydroxycoumarin standards.

The workflow for this protocol is visualized below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Successful research into photocatalytic sterilization requires specific reagents and materials for synthesizing catalysts, conducting experiments, and analyzing results. The following table outlines essential components of the researcher's toolkit.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Photocatalytic Sterilization Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Model Photocatalysts | Benchmarking activity and understanding fundamental mechanisms. | TiO₂ P25 [6]; Bi₂O₃ for visible-light studies [5]. |

| Chemical Probe: Coumarin | Trapping and indirect quantification of hydroxyl radicals (·OH). | Requires high purity (≥99%); forms multiple hydroxycoumarins upon ·OH attack [6]. |

| Hydroxylated Coumarin Standards | Calibration for accurate quantification of ·OH yield. | 3-, 4-, 5-, 6-, 7-, 8-hydroxycoumarin [6]. |

| Characterization Tools | In-situ monitoring of catalyst dynamics and surface reactions. | In-situ XPS, XAS (valence state) [9]; FTIR, Raman (surface intermediates) [9]; EPR (ROS/Oxygen vacancies) [9]. |

| Microbial Strains | Evaluating biocidal efficacy across different organisms. | Gram-negative (e.g., E. coli), Gram-positive (e.g., S. aureus), fungal species [5]. |

| CFI02 | CFI02 | CFI02 is a potent, selective inhibitor of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) glycoprotein B-mediated fusion. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| CBD-1 | CBD-1 Reagent|Cannabidiol for Research Use |

Photocatalytic sterilization using inorganic compounds represents a promising advanced oxidation process for addressing the challenge of microbial resistance. This application note delineates the primary microbial inactivation pathways initiated by photocatalysts, focusing on the sequence of events from initial cell wall damage to pervasive intracellular oxidative stress. The protocols and data presented herein are designed to support researchers and scientists in developing effective photocatalytic antimicrobial strategies.

Fundamental Mechanism of Photocatalytic Microbial Inactivation

The antimicrobial efficacy of photocatalysts arises from their ability to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) upon light irradiation. When a photocatalyst absorbs photons with energy equal to or greater than its bandgap energy, electrons ((e^-)) are promoted from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB), creating positively charged holes ((h^+)) in the VB [10] [11]. These photogenerated charge carriers then migrate to the catalyst surface and react with adsorbed water and oxygen molecules, yielding powerful ROS including hydroxyl radicals ((\bullet OH)), superoxide anions ((O2^{ \bullet - })), hydrogen peroxide ((H2O2)), and singlet oxygen ((^1O2)) [12] [13].

The resulting ROS collectively initiate a cascade of oxidative damage events on microbial cells, beginning with the external cell structures and progressing to intracellular components, ultimately leading to complete cell inactivation and mineralization [10] [13].

Figure 1: Microbial Inactivation Pathway by Photocatalysts. This diagram illustrates the sequential mechanism from photon absorption to complete cell mineralization.

Quantitative Efficacy of Photocatalytic Materials

The antimicrobial performance of various photocatalytic materials has been quantitatively demonstrated against multiple pathogenic microorganisms. The following table summarizes efficacy data from recent studies:

Table 1: Antimicrobial Efficacy of Photocatalytic Materials

| Photocatalyst Material | Microorganism | Experimental Conditions | Reduction Efficiency | Time | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiOâ‚‚/Agâ‚‚O/Auâ° NTs | S. aureus (MSSA) | Visible light | Complete inactivation | 60 min | [14] |

| TiOâ‚‚/Agâ‚‚O/PtOâ‚“ NTs | E. coli | Visible light | Complete inactivation | 60 min | [15] |

| TiOâ‚‚/Cuâ‚‚O/Auâ° NTs | Clostridium sp. | Visible light | Complete inactivation | 60 min | [14] |

| Ag₃PO₄/P25 | E. faecalis VRE 037 | Visible light | 100% eradication (6 log reduction) | 60 min | [16] |

| Ag₃PO₄/HA | S. aureus USA 300 | Visible light | 100% eradication (6 log reduction) | 60 min | [16] |

| TiOâ‚‚/Agâ‚‚O/PtOâ‚“ NTs | K. oxytoca (ESBL) | Visible light | Complete inactivation | 60 min | [15] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Synthesis of Ternary Photocatalytic Nanotubes via Anodic Oxidation

This protocol describes the fabrication of visible-light-active nanotube arrays through one-step anodic oxidation of titanium-based alloys, adapted from studies demonstrating high antimicrobial activity [14] [15].

Materials and Equipment

- Substrate Material: Titanium-based alloy foils (Ti94Ag5Au1, Ti94Cu5Pt1, Ti94Cu5Au1, Ti94Ag5Pt1 composition)

- Chemicals: Ethylene glycol (98%), ammonium fluoride (NH₄F, ≥99%), acetone, isopropanol, methanol

- Equipment: DC power supply, platinum mesh cathode, ultrasonic bath, furnace, two-electrode electrochemical cell

Procedure

Substrate Preparation:

- Cut alloy foils into 2.5 cm × 2.5 cm pieces

- Clean sequentially in ultrasonic bath: 10 min acetone → 10 min isopropanol → 10 min methanol → 10 min deionized water

- Dry thoroughly with air stream

Electrolyte Preparation:

- Prepare 150 mL of electrolyte containing:

- Ethylene glycol (98 vol%)

- Deionized water (2 vol%)

- NHâ‚„F (0.09 M)

- Stir at 500 rpm to ensure complete dissolution

- Prepare 150 mL of electrolyte containing:

Anodization Process:

- Set up electrochemical cell with alloy sample as anode and platinum mesh as cathode (2 cm distance)

- Apply constant voltage of 30 V (current density will decrease from ~25 mA/cm² to ~2 mA/cm²)

- Maintain reaction for 60-90 minutes under continuous stirring

- Monitor temperature to maintain at 20-25°C

Post-treatment:

- Sonicate samples in deionized water to remove surface debris

- Dry in air stream at 80°C for 24 hours

- Calcinate in furnace at 450°C for 1 hour with heating rate of 2°C/min

Quality Control

- Characterize nanotube morphology by SEM: Inner diameter should be 54-65 nm, length 2.3-2.6 μm

- Verify composition by XPS and phase composition by XRD

- Confirm presence of metal/metal oxide nanoparticles on surface and inside nanotube walls

Protocol 2: Photocatalytic Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

This protocol standardizes the evaluation of photocatalytic materials against pathogenic bacteria, incorporating methodology from recent studies [16] [15].

Materials and Equipment

- Test Organisms: Methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA), E. coli, Clostridium sp., ESBL K. oxytoca

- Culture Media: Appropriate broth and agar for each bacterial strain

- Photocatalyst Samples: Ternary nanotubes or composite powders

- Equipment: Visible light source (λ ≥ 400 nm, 300 W Xe lamp with UV filter), shaking incubator, colony counter

Procedure

Bacterial Culture Preparation:

- Inoculate single colonies in appropriate broth

- Incubate overnight at optimal temperature with shaking

- Harvest cells in mid-logarithmic phase (OD₆₀₀ ≈ 0.4-0.6)

- Centrifuge, wash, and resuspend in physiological saline to ~10ⶠCFU/mL

Photocatalytic Inactivation Assay:

- For suspended powders: Add photocatalyst (750-1500 μg/mL) to bacterial suspension

- For nanotube films: Place films in sterile containers with bacterial suspension

- Maintain dark control (catalyst + bacteria, no light) and light control (bacteria + light, no catalyst)

- Expose to visible light irradiation with continuous shaking

- Sample at intervals (0, 30, 60 minutes)

Viability Assessment:

- Serially dilute samples in physiological saline

- Spread plate appropriate dilutions on agar plates

- Incubate at optimal temperature for 24-48 hours

- Count colonies and calculate Logâ‚â‚€ reduction: Log(Nâ‚€/N)

- Nâ‚€ = initial viable count (CFU/mL)

- N = viable count after treatment (CFU/mL)

Mechanistic Studies

ROS Detection:

- Use fluorescent probes (DCFH-DA for intracellular ROS, HPF for •OH)

- Monitor fluorescence intensity by spectrofluorometry

Cell Membrane Integrity:

- Assess potassium ion leakage using atomic absorption spectroscopy

- Measure metabolite release by monitoring 260 nm absorbance

Morphological Analysis:

- Fix samples with glutaraldehyde (2.5%) and osmium tetroxide (1%)

- Dehydrate through ethanol series, critical point dry

- Examine by TEM/SEM for structural damage

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Photocatalytic Antimicrobial Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Ternary Alloy Substrates | Source for nanotube fabrication via anodization | Ti94Ag5Au1, Ti94Cu5Pt1 (94% Ti, 5% Ag/Cu, 1% Au/Pt) |

| Ethylene Glycol Electrolyte | Medium for electrochemical anodization | 98% ethylene glycol, 2% Hâ‚‚O, 0.09M NHâ‚„F |

| Ag₃PO₄-Based Composites | Visible-light-active photocatalysts | Ag₃PO₄/P25, Ag₃PO₄/HA (hydroxyapatite) |

| ROS Detection Probes | Detection of reactive oxygen species | DCFH-DA (intracellular ROS), HPF (hydroxyl radicals) |

| Pathogenic Bacterial Strains | Model organisms for efficacy testing | S. aureus MSSA, E. coli, E. faecalis VRE, Clostridium sp. |

| Visible Light Source | Activation of photocatalysts | 300W Xe lamp with 400nm cutoff filter |

| OdD1 | OdD1 | Chemical Reagent |

| YS-49 | YS-49, CAS:132836-42-1, MF:C20H20BrNO2, MW:386.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The sequential microbial inactivation pathway initiated by photocatalytic materials provides a comprehensive mechanism for effective sterilization. Beginning with ROS-mediated cell wall damage and progressing through membrane disruption to intracellular oxidative stress, this cascade ultimately leads to complete cell mineralization. The experimental protocols and research tools detailed in this application note provide researchers with standardized methodologies for developing and evaluating novel photocatalytic antimicrobial systems for healthcare, water purification, and surface sterilization applications.

Photocatalytic sterilization using inorganic semiconductors presents a sustainable and effective strategy for combating microbial contamination and addressing the challenge of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). This process leverages light energy to generate highly reactive oxygen species (ROS) on the catalyst's surface, which inactivate microbial species through oxidative damage to cell membranes, proteins, and nucleic acids [13]. Titanium Dioxide (TiOâ‚‚), Silver Composites (Ag), and Zinc Oxide (ZnO) stand as the most prominent photocatalysts for these applications, each offering a unique combination of potent antimicrobial activity, environmental friendliness, and material stability [13] [17] [18]. Their ability to simultaneously degrade organic pollutants and inactivate pathogens makes them particularly valuable for environmental remediation and biomedical applications, from water purification to self-disinfecting surfaces [13] [17].

Catalyst Mechanisms and Antibacterial Activity

Fundamental Photocatalytic Mechanism

The antimicrobial action of these inorganic photocatalysts originates from a light-induced redox reaction. Upon irradiation with light of energy greater than the material's bandgap, electrons (eâ») are promoted from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB), creating electron-hole (eâ»/hâº) pairs [13]. These charge carriers migrate to the catalyst surface and react with adsorbed water and oxygen, generating a suite of reactive oxygen species (ROS), including the hydroxyl radical (•OH), superoxide radical anion (O₂•â»), and hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) [13] [19]. The resulting ROS inflict comprehensive damage to microbial cells, leading to cell death.

- Primary Oxidative Damage: The hydroxyl radical (•OH), one of the most potent oxidizers, and other ROS cause peroxidation of lipids, oxidation of proteins, and disruption of essential cellular enzymes [13].

- Cell Membrane Disruption: ROS attack and degrade the bacterial cell wall and cytoplasmic membrane, compromising structural integrity and increasing permeability. This can lead to leakage of intracellular components and eventual cell lysis [13] [18]. Silver composites exert an additional mechanism where nanoparticles interact directly with and disrupt microbial membranes [18].

- Intracellular and Genetic Damage: After membrane compromise, ROS and, in some cases, a fraction of nanoparticles can penetrate the cytoplasm. This causes oxidative damage to chromosomal and plasmid DNA, resulting in strand breaks, cross-links, and base oxidation, which prevents replication and transcription [13]. This dual action of microbial inactivation and genetic material degradation highlights the potential of photocatalysis to also reduce the spread of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) [13].

The diagram below illustrates this sequential process of photocatalytic bacterial inactivation.

Comparative Antibacterial Performance

The antibacterial efficacy of TiOâ‚‚, Ag composites, and ZnO varies based on their intrinsic properties and the target microorganisms. Gram-negative bacteria (e.g., E. coli), with their thinner peptidoglycan layer and outer membrane rich in lipopolysaccharides, are generally more susceptible to photocatalytic inactivation than Gram-positive bacteria (e.g., S. aureus), which have a thicker peptidoglycan layer [13]. Furthermore, bacterial species with higher inherent superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity can better mitigate oxidative stress, contributing to variations in susceptibility [13].

Table 1: Comparative Antibacterial Performance of Key Photocatalysts

| Photocatalyst | Key Antibacterial Mechanisms | Advantages for Sterilization | Limitations & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Titanium Dioxide (TiOâ‚‚) | Primary: ROS-induced oxidative damage [13]. | High oxidative power, chemical stability, non-toxicity, eco-friendly, can degrade antibiotic resistance genes [13]. | Limited to UV activation (pristine TiOâ‚‚), electron-hole recombination reduces efficiency [13] [20]. |

| Silver Composites (Ag) | 1. Release of bactericidal Ag⺠ions [18].2. ROS generation [18].3. Direct membrane disruption [18]. | Broad-spectrum activity, multiple simultaneous mechanisms, effective at low concentrations, suitable for coatings [21] [18]. | Potential environmental toxicity, cost, aggregation can reduce efficacy [13] [21]. |

| Zinc Oxide (ZnO) | 1. ROS-induced oxidative damage [17].2. Release of Zn²⺠ions [17]. | High photocatalytic efficiency, low cost, biocompatibility, piezoelectric properties [22] [17]. | Photocorrosion in aqueous environments can limit reusability; bandgap similar to TiO₂ [17]. |

Quantitative Performance Data in Applications

The performance of photocatalysts is quantified in various applications, including dye degradation in wastewater and direct bacterial inactivation. The following table summarizes key metrics reported in recent studies.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of Photocatalysts in Key Applications

| Photocatalyst | Application/Test | Experimental Conditions | Reported Efficiency / Result | Source Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZnO (Sol-Gel with Ethanol) | Methylene Blue (MB) dye degradation | 0.1 g catalyst, 5 mg/L MB, 100 mL, UV light [22]. | 98% degradation achieved [22]. | [22] |

| TiOâ‚‚/CuO Composite | Herbicide (Imazapyr) degradation | UV illumination [20]. | Highest photonic efficiency among TiOâ‚‚ composites tested [20]. | [20] |

| Biosynthesized AgNPs | Antibacterial activity & Methylene Blue (MB) dye degradation | Synthesized using L. rhamnosus; AgNP characteristics: 199.7 nm avg. size, -36.3 mV zeta potential [21]. | Strong antibacterial activity & high photocatalytic efficiency reported [21]. | [21] |

| TiOâ‚‚ (General) | Photocatalytic bacterial inactivation | UV light, close contact with bacterial cells required [13]. | Efficiency depends on material modification, ROS generation kinetics, and bacterial species [13]. | [13] |

Synthesis and Experimental Protocols

Modified Sol-Gel Synthesis of ZnO Nanoparticles

This protocol describes a sol-gel method for synthesizing ZnO nanoparticles, adapted from a study investigating the effect of solvent choice (ethanol, 1-propanol, 1,4-butanediol) on photocatalytic performance [22]. Ethanol was found to produce ZnO with superior activity, achieving 98% degradation of Methylene Blue dye in a short duration [22].

Principle: Zinc acetate dihydrate reacts with oxalic acid dihydrate in a solvent to form a zinc oxalate precursor, which upon calcination, decomposes to phase-pure ZnO nanoparticles [22].

Materials:

- Zinc Acetate Dihydrate (Zn(CH₃COO)₂·2H₂O): Metal ion precursor.

- Oxalic Acid Dihydrate ((COOH)₂·2H₂O): Precipitating and complexing agent.

- Solvents (Ethanol, 1-Propanol, 1,4-Butanediol): Reaction medium; influences particle morphology and size.

- Deionized Water: For washing and purification.

Procedure:

- Solution A: Dissolve a measured amount of zinc acetate dihydrate in 50 mL of ethanol using a magnetic stirrer at 50°C for 30 minutes [22].

- Solution B: Dissolve an equimolar amount of oxalic acid dihydrate in 25 mL of ethanol at room temperature [22].

- Gel Formation: Slowly add Solution B to Solution A with continuous stirring. Heat the mixture to 70°C with constant stirring until a viscous white gel forms [22].

- Drying: Transfer the gel to an oven and dry at 80°C overnight to remove residual solvents [22].

- Calcination: Place the dried precursor in a furnace and calcine at 600°C for 4 hours (240 minutes) to thermally decompose zinc oxalate into ZnO nanoparticles [22].

- Milling: Gently crush the resulting powder using an agate mortar and pestle to obtain a fine, homogeneous ZnO nanopowder [22].

The workflow for this synthesis is summarized below.

Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs) Using Probiotics

This protocol outlines a green synthesis method for AgNPs using the probiotic strain Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus, which acts as both a reducing and a stabilizing agent, producing stable nanoparticles with antibacterial and photocatalytic properties [21].

Principle: Metabolic enzymes and biomolecules in the bacterial extracellular extract facilitate the reduction of silver ions (Agâº) to elemental silver (Agâ°), forming nanoparticles capped by biological molecules that prevent aggregation [21].

Materials:

- Probiotic Strain: Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus (e.g., BCRC16000).

- Silver Nitrate (AgNO₃) Solution: Source of Ag⺠ions.

- Growth Medium (e.g., MRS Broth): For culturing the probiotic strain.

- Centrifuge and Filtration Units: For cell separation.

Procedure:

- Culture Preparation: Inoculate L. rhamnosus in a suitable growth medium and incubate under optimal conditions (e.g., 37°C for 24-48 hours) to obtain a stationary-phase culture [21].

- Cell-Free Supernatant: Centrifuge the culture (e.g., at 10,000 rpm for 10 minutes) to pellet the bacterial cells. Filter the supernatant through a 0.22 µm membrane filter to obtain a clear, cell-free extract [21].

- Reaction Mixture: Add a predetermined volume of aqueous AgNO₃ solution (e.g., 1-10 mM final concentration) to the cell-free supernatant. The mixture should turn from pale yellow to deep brown, indicating AgNP formation [21].

- Incubation and Synthesis: Incubate the reaction mixture in the dark at room temperature with gentle stirring for 24-48 hours to allow complete reduction [21].

- Purification: Centrifuge the AgNP suspension at high speed (e.g., 15,000 rpm for 30 minutes) to pellet the nanoparticles. Discard the supernatant and resuspend the pellet in deionized water. Repeat this washing step 2-3 times to remove residual ions and biomolecules [21].

- Characterization: Redisperse the purified AgNPs in water and characterize using UV-Vis spectroscopy (peak ~443 nm), DLS (for size distribution), and SEM [21].

Protocol for Evaluating Photocatalytic Antibacterial Activity

A standard procedure for assessing the efficacy of a photocatalyst in inactivating bacteria.

Principle: A bacterial suspension is exposed to the photocatalyst under controlled light irradiation. Samples are taken at intervals, and the number of viable cells is determined via serial dilution and plating, allowing for the quantification of inactivation kinetics [13].

Materials:

- Test Microorganism: e.g., Escherichia coli (Gram-negative) or Staphylococcus aureus (Gram-positive).

- Photocatalyst: TiOâ‚‚, ZnO, or AgNP powder/suspension.

- Light Source: UV lamp (e.g., Philips TL 8W BLB) or simulated solar light with appropriate filters.

- Nutrient Broth/Agar: For bacterial culture and viability assessment.

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS): For serial dilutions.

Procedure:

- Catalyst Dispersion: Disperse a known concentration of the photocatalyst (e.g., 0.1 mg/mL) in a saline solution or minimal medium within a reaction vessel. Ensure homogeneity using a magnetic stirrer or sonication [13] [22].

- Bacterial Inoculation: Introduce a standardized inoculum of mid-log phase bacteria to the catalyst suspension to achieve a initial concentration of ~10â¶-10â· CFU/mL.

- Dark Adsorption Control: Keep the mixture in the dark for 30 minutes with stirring to establish adsorption-desorption equilibrium between the bacteria and catalyst [13].

- Light Irradiation: Expose the mixture to light irradiation under continuous stirring. Maintain constant temperature (e.g., 25°C) using a water bath if necessary.

- Sampling: At predetermined time intervals (e.g., 0, 15, 30, 60, 120 min), withdraw aliquots from the reaction mixture.

- Serial Dilution and Plating: Perform serial 10-fold dilutions of each aliquot in PBS. Spread plate appropriate dilutions onto nutrient agar plates in duplicate.

- Viability Count: Incubate the plates at 37°C for 24-48 hours. Count the formed colonies and calculate the viable bacterial concentration (CFU/mL) for each time point.

- Control Experiments: Perform simultaneous control experiments: (a) catalyst in dark, (b) light without catalyst, (c) neither light nor catalyst.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Photocatalyst Research and Application

| Item Name | Function/Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Titanium Dioxide (Hombikat UV-100) | A common commercial TiOâ‚‚ benchmark photocatalyst (primarily anatase) used for performance comparison in degradation and antibacterial studies [20]. |

| Zinc Acetate Dihydrate | A common, soluble zinc salt precursor used in the sol-gel synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles [22]. |

| Silver Nitrate (AgNO₃) | The standard source of silver ions (Agâº) for the synthesis of various silver-based nanoparticles and composites [21]. |

| Methylene Blue (MB) | A standard organic dye used as a model pollutant for quantifying the photocatalytic degradation efficiency of catalysts under UV/visible light [22] [21]. |

| Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Probes | Chemical probes (e.g., for detecting •OH, O₂•â») used to confirm and quantify the generation of reactive species during photocatalysis, linking to the mechanism of action [13]. |

| Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus | A probiotic bacterial strain that can be used as a sustainable, biological agent for the green synthesis of stable silver nanoparticles [21]. |

| ACES | ACES, CAS:7365-82-4, MF:C4H10N2O4S, MW:182.20 g/mol |

| RD162 | RD162, CAS:915087-27-3, MF:C22H16F4N4O2S, MW:476.4 g/mol |

Titanium dioxide (TiO2) is a cornerstone semiconductor photocatalyst for environmental purification and sterilization applications, valued for its strong photocatalytic activity, chemical stability, and non-toxicity [23] [24]. Its efficacy is profoundly influenced by intrinsic structural properties, primarily its crystal phase, particle size, and specific surface area. TiO2 exists predominantly in three crystalline polymorphs: anatase, rutile, and brookite [25]. Among these, anatase is generally recognized for its superior photocatalytic activity, while rutile and brookite have distinct electronic properties that can be harnessed in composite systems [24] [26]. The photocatalytic process is initiated by the absorption of a photon with energy greater than the material's band gap, promoting an electron (eâ») from the valence band to the conduction band, thereby generating a hole (hâº) [24]. These charge carriers then migrate to the catalyst surface to drive redox reactions, generating Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) such as hydroxyl radicals (•OH) and superoxide anions (O₂•â»), which are responsible for the oxidative destruction of microbial cells [23] [24]. This application note delineates the structural factors governing TiO2 efficiency and provides detailed protocols for material evaluation and application in photocatalytic sterilization, framed within research on inorganic compounds.

Comparative Analysis of TiO2 Polymorphs

Fundamental Properties and Photocatalytic Mechanisms

The three main TiO2 polymorphs—anatase, rutile, and brookite—differ in their crystal lattice arrangements, which directly dictates their electronic properties and photocatalytic performance [25].

- Anatase possesses a tetragonal structure characterized by octahedra that share four edges, leading to a slightly larger band gap (~3.2 eV) compared to rutile [27] [25]. This larger band gap provides a higher redox potential, particularly for hole-driven oxidation reactions, increasing the "power" of the generated radicals [27]. A critical factor behind its high activity is its indirect band gap, which results in longer charge carrier lifetimes compared to the direct band gap of rutile, giving electrons and holes more time to reach the surface and participate in reactions [27] [26]. Furthermore, studies on epitaxial films have demonstrated that anatase exhibits a longer effective charge carrier diffusion length (~5 nm) than rutile (~2.5 nm), meaning charge carriers excited deeper in the bulk can contribute to surface reactions [27].

- Rutile, the thermodynamically most stable phase, also has a tetragonal structure but is composed of octahedra that share two edges, with a narrower band gap of ~3.0 eV [27] [25]. This allows it to absorb a broader spectrum of light, including a small portion of visible light. However, rutile suffers from a significantly higher rate of charge carrier recombination, which is often attributed to deeper electron traps that prevent electrons from participating in surface reactions [26].

- Brookite, an orthorhombic phase, is less studied. Its structure involves octahedra sharing three edges [25]. Recent evidence suggests that the presence of shallow electron traps in brookite can effectively extend the lifetime of photogenerated holes, making it a potent photocatalyst, especially when synthesized with a high surface area [26].

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of these polymorphs.

Table 1: Structural and Electronic Properties of TiO2 Polymorphs

| Property | Anatase | Rutile | Brookite |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crystal Structure | Tetragonal | Tetragonal | Orthorhombic |

| Band Gap (eV) | ~3.2 [27] | ~3.0 [27] | ~3.1-3.4 [25] |

| Band Gap Type | Indirect [27] | Direct [27] | - |

| Charge Carrier Lifetime | Longer [27] [26] | Shorter [26] | Intermediate (long hole lifetime) [26] |

| Relative Photocatalytic Activity | Generally Highest [27] [24] | Lower [27] [24] | Can be comparable to anatase with high SSA [26] |

| Key Advantage | High charge carrier mobility & lifetime [27] | Broader UV absorption [28] | Shallow electron traps [26] |

The Synergistic "Mixed-Phase" Effect

While anatase often demonstrates superior performance alone, a synergistic effect is famously observed in mixed-phase catalysts, such as the commercial benchmark Evonik AEROXIDE P25 (approximately 80% anatase, 20% rutile) [28] [24]. This enhanced activity is attributed to efficient charge separation at the interfaces between the two phases. The prevailing model suggests that photoexcited electrons tend to accumulate in the anatase conduction band, while holes migrate to the rutile phase, thereby reducing the bulk recombination of electron-hole pairs and increasing the number of charge carriers available for surface reactions [28].

Mechanism of Photocatalytic Sterilization

The antimicrobial action of TiO2 is a direct consequence of the redox reactions initiated by the photogenerated charge carriers on its surface. The following diagram illustrates the sequential mechanism of photocatalytic disinfection.

Diagram 1: Mechanism of Photocatalytic Disinfection. The process begins with light absorption and culminates in microbial cell destruction via ROS-induced oxidative damage.

The primary ROS, the hydroxyl radical (•OH), possesses a reaction energy (120 kcal molâ»Â¹) higher than the bond energies of key organic molecules (e.g., C-C, C-H, C-O), enabling it to efficiently decompose lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids that constitute microbial cells [23]. This multi-target oxidative assault leads to extensive damage to the cell structure, causing leakage of cellular contents and ultimately resulting in cell lysis and complete mineralization [24].

Quantitative Data on Structural Influences

The Interplay of Particle Size and Surface Area

The physical dimensions of TiO2 particles are intrinsically linked to their specific surface area (SSA), which is a critical parameter determining the density of available active sites for reactant adsorption and surface reactions [29]. A systematic study on anatase TiO2 with varying primary particle sizes revealed a clear trend: as the primary particle size increases, the SSA decreases [29]. For instance, 6 nm anatase particles had an SSA of 253.9 m²/g, while 104 nm particles had an SSA of only 15.0 m²/g [29]. This relationship directly impacts photocatalytic efficiency, as a higher SSA generally promotes higher activity by providing more reaction sites. However, the effect of particle size is complex and can be phase-dependent. For anatase, an increase in crystallite size (from 10 nm to 20 nm) was found to compensate for the negative effect of a decreasing SSA (from 129.5 m²/g to 65.0 m²/g), likely due to improved crystallinity reducing bulk recombination [26]. In contrast, for brookite, photocatalytic activity dropped sharply with decreasing SSA (from 17.2 m²/g to 3.0 m²/g) while the crystallite size was held constant, indicating a more direct dependence on surface area for this phase [26].

Table 2: Effect of Anatase Primary Particle Size and Specific Surface Area on Dispersion Properties in Deionized Water [29]

| Primary Particle Size (nm) | Specific Surface Area (m²/g) | Hydrodynamic Size (nm) | Isoelectric Point (IEP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 253.9 | ~200 | 6.0 |

| 16 | 102.1 | ~250 | 5.2 |

| 26 | 61.5 | ~300 | 4.8 |

| 38 | 41.2 | ~400 | 4.5 |

| 53 | 29.7 | ~500 | 4.2 |

| 104 | 15.0 | >1000 | 3.8 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Evaluating Photocatalytic Disinfection Activity

This protocol details a standard procedure for assessing the sterilization efficiency of TiO2 photocatalysts against model microorganisms like Escherichia coli.

1. Reagent and Material Preparation:

- Photocatalyst: Weigh a precise mass (e.g., 5-50 mg) of the TiO2 sample (powder or immobilized on a substrate).

- Bacterial Suspension: Prepare a suspension of the target microorganism (e.g., E. coli at ~10ⶠCFU/mL) in a sterile physiological solution (e.g., 0.85% NaCl) or a nutrient-poor buffer.

- Reaction Vessel: Use a sterile beaker or quartz reactor. For powder catalysts, magnetic stirring is essential to maintain suspension.

2. Adsorption-Desorption Equilibrium:

- Add the catalyst to the bacterial suspension in the reactor.

- Place the reactor in the dark with continuous stirring for a predetermined period (typically 30-60 minutes). This step ensures that the decrease in viable cells upon illumination is due to photocatalysis and not simple adsorption or dark inactivation.

- Take a 1 mL sample at the end of the dark period for the "time zero" (tâ‚€) bacterial count.

3. Photocatalytic Reaction:

- Initiate illumination using a light source with appropriate wavelength and intensity (e.g., UVA lamp, 365 nm, 1-10 mW/cm²). A cut-off filter (<385 nm) may be used to ensure only UV light activates the catalyst if studying pure phase TiO2.

- Maintain constant stirring and temperature (e.g., 25°C) throughout the experiment.

- Withdraw aliquots (e.g., 1 mL) at regular time intervals (e.g., 0, 15, 30, 60, 120 min).

4. Analysis and Quantification:

- Viable Cell Count: Serially dilute the withdrawn samples in a sterile diluent. Spread plate appropriate dilutions onto nutrient agar plates in duplicate. Incubate the plates at 37°C for 24-48 hours, then enumerate the colony-forming units (CFU). The disinfection efficiency can be calculated as log reduction: Logâ‚â‚€(Nâ‚€/N), where Nâ‚€ and N are the viable cell counts at tâ‚€ and time t, respectively.

- Control Experiments: Conduct mandatory control experiments:

- Light Control: Bacteria + Light, without catalyst.

- Dark Control: Bacteria + Catalyst, in the dark.

Protocol: Assessing Charge Carrier Dynamics via Dye Degradation

The photocatalytic activity can also be probed by monitoring the degradation of a model organic dye, such as Methyl Orange (MO), under UV or visible light.

1. Standard Reaction Setup:

- Prepare an aqueous MO solution (e.g., 20 µM).

- Disperse a known mass of TiO2 powder (e.g., 5 mg) in a known volume of MO solution (e.g., 50 mL) in a quartz reactor.

- Place the mixture in the dark with stirring for 30-60 minutes to establish adsorption-desorption equilibrium.

2. Photocatalytic Degradation:

- Start illumination under stirring. Use a UVA or simulated solar light source.

- Withdraw samples (e.g., 3-4 mL) at regular intervals.

- Immediately centrifuge the samples (or filter through a 0.22 µm membrane) to remove catalyst particles.

3. Quantitative Analysis:

- Measure the absorbance of the clear supernatant at the characteristic maximum absorption wavelength of MO (e.g., 464 nm) using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer.

- The degradation efficiency is calculated as (C₀ - C)/C₀ × 100%, where C₀ is the initial concentration of MO after the dark period, and C is the concentration at time t. The apparent rate constant (k) can be determined by fitting the concentration-time data to a pseudo-first-order kinetic model: ln(C₀/C) = kt.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Photocatalytic Sterilization Research

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Evonik AEROXIDE P25 | Benchmark mixed-phase (80/20 anatase/rutile) TiO2 photocatalyst; used for comparative activity studies. | Positive control in dye degradation and disinfection experiments [28] [24]. |

| Anatase & Rutile TiO2 Nanopowders | High-purity, single-phase catalysts for structure-activity relationship studies. | Synthesized via sol-gel or flame aerosol methods to investigate polymorph-specific efficacy [27] [29]. |

| Methyl Orange (MO) | Azo dye used as a model organic pollutant for quantifying photocatalytic oxidation efficiency. | Probe for hydroxyl radical activity under UV light; measurement via UV-Vis spectrophotometry [28]. |

| Escherichia coli (E. coli) K-12 | Gram-negative bacterium, commonly used as a model organism for photocatalytic disinfection assays. | Assessing bactericidal activity via standard plate count method (CFU enumeration) [23] [24]. |

| UVA Light Source (e.g., 365 nm LED/Lamp) | Provides photons with energy exceeding the band gap of TiO2 to initiate photocatalysis. | Primary activation source for pure and modified TiO2 in sterilization and degradation protocols. |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) Zetasizer | Instrument for characterizing hydrodynamic size and zeta potential of nanoparticle dispersions. | Evaluating colloidal stability and agglomeration state of TiO2 in aqueous suspensions [29]. |

| ML268 | ML268 TRPML3 Agonist| Available|RUO | |

| ML186 | ML186|GPR55 Agonist|For Research Use Only | ML186 is a potent and selective GPR55 agonist for research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

Designing and Applying Advanced Photocatalytic Systems

The development of advanced inorganic photocatalysts for sterilization applications hinges on precise control over material synthesis and structure. Sol-gel methods, hydrolysis, and nanostructuring have emerged as cornerstone techniques for fabricating semiconductor photocatalysts with enhanced activity against microbial pathogens. These processes enable fine-tuning of critical parameters including crystal phase, band gap energy, surface area, and particle morphology, which collectively determine photocatalytic efficiency. Within the context of photocatalytic sterilization, materials such as TiO₂, Fe₂O₃, and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) like ZIF-8 are synthesized and modified to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) under light irradiation, leading to microbial inactivation. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for synthesizing and evaluating such photocatalysts, framed within a research thesis on photocatalytic sterilization using inorganic compounds.

Synthesis Methods and Comparative Analysis

The sol-gel process is a versatile wet-chemical technique enabling the fabrication of metal oxides with high purity and homogeneity at relatively low temperatures [30]. Concurrently, controlled hydrolysis routes are pivotal for structuring materials like MOFs. The table below summarizes key synthesis strategies for prominent photocatalytic materials.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Photocatalyst Synthesis Strategies

| Material System | Synthesis Method | Key Structural Features | Band Gap Energy (eV) | Primary Antimicrobial Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiOâ‚‚-Based (e.g., Feâ‚‚O₃-doped) | Acid-catalyzed sol-gel [30] [31] | Anatase/rutile phase mixture, high surface area, nanoscale particles | ~3.0 (bare TiOâ‚‚); reduces with doping [32] [31] | ROS generation (•OH, •Oâ‚‚â») causing protein oxidation and cell membrane disruption [33] |

| Hydrolyzed ZIF-8/ZnS Composite | Aqueous reflux hydrolysis [34] | Z-scheme heterojunction, improved aqueous stability, fused crystallite topology | Not specified | Enhanced charge separation, ROS production via Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚-assisted Advanced Oxidation Process (AOP) [34] |

| Nanostructured TiOâ‚‚ | Sol-gel in Spinning Disc Reactor (SDR) [32] | Controlled particle size (e.g., ~40 nm), tunable anatase/rutile ratio | 3.00; 2.53 (Cu-doped) [32] | Not specifically studied for disinfection, but mechanism presumed via ROS generation. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Sol-Gel Synthesis of TiO₂-Fe₂O₃/PVP Hybrid Powders

This protocol describes the synthesis of ternary hybrid powders for the photocatalytic degradation of tetracycline hydrochloride, with relevance to antibacterial activity [31].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Sol-Gel Synthesis of TiO₂-Fe₂O₃/PVP

| Reagent | Function/Role | Specifications/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Titanium(IV) tetrabutoxide (Ti(OBu)₄) | Primary TiO₂ precursor | Reagent grade, ≥97%. Handle under inert atmosphere if necessary. |

| Iron(III) nitrate nonahydrate (Fe(NO₃)₃·9H₂O) | Fe₂O₃ dopant precursor | p.a. (pro analysis) grade. |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | Capping agent, polymer matrix | Mr 24,000. Prevents particle agglomeration and controls growth. |

| Ethanol (Câ‚‚Hâ‚…OH) | Solvent | 96% purity. |

| Deionized Water | Hydrolysis agent | Acidified to pH 1 for controlled reaction. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Preparation of Solution A: Dissolve 10 mmol of Ti(OBu)â‚„ in 20 mL of absolute ethanol under vigorous magnetic stirring (400-500 rpm) at room temperature for 10 minutes.

- Preparation of Solution B: Dissolve PVP, Fe(NO₃)₃·9H₂O (to achieve 10 or 20 wt% Fe₂O₃), and acidified water (pH 1) in a mass ratio of PVP/Fe₂O₃/H₂O = 3:1:1 in 20 mL of ethanol. Stir until complete dissolution.

- Mixing and Gelation: Slowly add Solution B to Solution A under continuous stirring. The gelation occurs immediately.

- Aging: Allow the resulting gel to age in air at room temperature for 72 hours to complete the hydrolysis and condensation reactions.

- Drying and Calcination: Dry the aged gel at 80°C for 12 hours. For subsequent thermal treatment, calcine the powder in a muffle furnace at 500°C for 2 hours in air to induce crystallization.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the sol-gel synthesis process:

Protocol 2: Hydrolyzed Mo@h-ZIF-8/ZnS Composite via Reflux

This protocol outlines a green synthesis for a water-stable, hydrolyzed MOF-based photocatalyst effective against various dyes, demonstrating potential for water disinfection [34].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Synthesis of Mo@h-ZIF-8/ZnS Composite

| Reagent | Function/Role | Specifications/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Zinc Nitrate Hexahydrate [Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O] | Zn source for ZnS and ZIF-8 | 99% purity. |

| Sodium Sulfide Flakes [Na₂S·9H₂O] | Sulfur source for ZnS | 98% purity. |

| 2-Methylimidazole [Hmim] | Organic linker for ZIF-8 | >97% purity. |

| Ammonium Heptamolybdate [(NH₄)₆Mo₇O₂₄·4H₂O] | Molybdenum dopant source | 99% purity. Enhances charge separation. |

| Cetyltrimethylammonium Bromide (CTAB) | Surfactant and capping agent for ZnS | 99% purity. Controls particle size and morphology. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Synthesis of ZnS Substrate:

- Dissolve 1 g of Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O and 0.02 g of CTAB in 40 mL of distilled water. Stir for 1 hour.

- Separately, dissolve 0.806 g of Na₂S·9H₂O in a minimal volume of water.

- Add the Naâ‚‚S solution dropwise to the Zn/CTAB solution under continuous stirring.

- Stir the mixture for 3 hours at room temperature.

- Centrifuge the greyish-white precipitate, wash with distilled water and ethanol, and dry at 50°C overnight.

Synthesis of Hydrolyzed ZIF-8 (h-Z8):

- Dissolve 1 g of Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O and 2.4 g of 2-methylimidazole separately in 50 mL of distilled water each.

- Slowly add the zinc solution to the ligand solution with stirring to form a cloudy mixture.

- Transfer the mixture to a round-bottom flask and reflux at 90°C for 12 hours with magnetic stirring.

- Collect the white h-Z8 precipitate by centrifugation, wash, and dry at 50°C overnight.

Fabrication of Mo@h-ZIF-8/ZnS Composite:

- Disperse 200 mg of the as-synthesized ZnS in 50 mL of distilled water.

- In a separate container, dissolve the molybdenum precursor and combine with the h-Z8 suspension.

- Add this mixture to the dispersed ZnS and subject the final mixture to reflux condensation to form the composite catalyst.

Material Characterization and Photocatalytic Testing

Key Characterization Techniques

Rigorous characterization is essential to correlate synthesis parameters with photocatalytic performance.

- X-Ray Diffraction (XRD): Determines crystal phase composition (e.g., anatase/rutile ratio), crystallite size, and unit cell parameters via Rietveld refinement [31].

- UV-Vis Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy: Measures optical absorption and determines band gap energy using Tauc plots [32] [31].

- Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM): Images particle morphology, size, and surface topography [31].

- Surface Area Analysis (BET): Quantifies specific surface area via low-temperature nitrogen adsorption, a critical factor for pollutant adsorption and ROS generation sites [31].

- Infrared (IR) Spectroscopy: Identifies functional groups and confirms the presence of polymers like PVP in hybrids [31].

Photocatalytic Activity and Antibacterial Assessment

Degradation of Organic Pollutants

- Setup: A slurry reactor with the photocatalyst dispersed in a model pollutant solution (e.g., 10 ppm Tetracycline Hydrochloride or Malachite Green). The light source (e.g., UV blacklight, simulated solar light, or natural sunlight) is positioned at a fixed distance (e.g., 7 cm) above the solution [31] [34].

- Procedure: The suspension is stirred in the dark initially to establish adsorption-desorption equilibrium. After turning on the light, aliquots are taken at regular intervals, centrifuged to remove catalyst particles, and analyzed by UV-Vis spectroscopy or High-Resolution Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (HR-LCMS) to monitor degradation and identify intermediates [31] [34].

- Data Analysis: Degradation efficiency is calculated from the decrease in characteristic absorption peak intensity. Response Surface Methodology (RSM) can optimize parameters like catalyst loading, pollutant concentration, and irradiation time [34].

Antibacterial Activity Testing

- Model Organism: E. coli ATCC 25922 is a commonly used gram-negative bacterial model [31].

- Procedure: The catalyst is tested against bacterial suspensions in the presence of light (e.g., UVA). Antibacterial action is assessed by monitoring bacterial growth inhibition, often via colony counting methods, and is attributed to ROS-induced oxidative stress and cell membrane disruption [33] [31].

The following diagram illustrates the photocatalytic mechanism for sterilization:

Performance Data from Case Studies

The table below summarizes quantitative performance data from the cited research, providing benchmarks for expected outcomes.

Table 4: Photocatalytic Performance of Synthesized Materials

| Photocatalyst | Application/Target | Optimal Conditions | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 90TiO₂-10Fe₂O₃/PVP (sol-gel, calcined) [31] | Degradation of Tetracycline Hydrochloride (TCH) | UV or solar light, 10 ppm TCH | Exhibited the best photocatalytic efficiency among tested hybrids. |

| Mo@h-ZIF-8/ZnS (hydrolysis) [34] | Degradation of Malachite Green (MG) dye | 0.05 mM Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚, 6.5 mg catalyst, 66.5 ppm MG, 50-53 min sunlight | 99.14% degradation (predicted), 98.95% (experimental). >80% efficiency for multiple dyes. |

| Nanostructured TiOâ‚‚ (SDR, Cu-doped) [32] | COâ‚‚ Reduction to Formate | 0.5 g Lâ»Â¹ loading, 4 mL minâ»Â¹ flow rate, UV (254 nm) | Formate production rate: 500 μmol gâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹ (bare); enhanced with Cu-doping. |

| Pt/C-TiO(B)-650 [35] | Methanol dehydrogenative coupling | Pt-loaded catalyst, 55°C, UV light (320-400 nm) | Turnover Frequency: 2754 hâ»Â¹; Accumulated TON: 120,000 in 130 h. |

The synthesized materials demonstrate high efficacy in photocatalytic reactions, which is directly translatable to sterilization applications. The ROS generated to degrade organic dyes are the same species that inactivate microorganisms by damaging their cell walls, proteins, and genetic material [33].

For researchers aiming to employ these protocols for sterilization studies, the following points are critical:

- Material Selection: TiO₂-based systems are excellent for UV light sources, while composites like Fe₂O₃/TiO₂ and hydrolyzed MOFs can leverage visible/solar light, enhancing practical applicability [30] [34].

- Process Optimization: Use statistical tools like RSM to efficiently determine the optimal combination of catalyst dose, light intensity, and treatment time for specific bacterial targets [34].

- Stability and Reusability: Always assess catalyst stability and reusability over multiple cycles. As demonstrated by the Mo@h-ZIF-8/ZnS composite, a robust catalyst can retain over 76% efficiency after six cycles [34].

These synthesis strategies provide a solid foundation for developing advanced photocatalytic materials tailored for effective and sustainable sterilization technologies.

Application Notes

The integration of plasmonic silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs) with graphitic carbon nitride (g-C₃N₄) and the strategic doping of semiconductors represent a significant advancement in the field of photocatalytic sterilization. These material innovations enhance the efficiency of visible-light-driven photocatalysis, addressing critical challenges in environmental remediation and water disinfection.

Plasmonic Silver and g-C₃N₄ Composites

The combination of plasmonic Ag NPs with g-C₃N₄ creates composite materials that exhibit significantly enhanced photocatalytic activity under visible light. The primary mechanism for this enhancement is the Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) effect of metallic silver, which increases the absorption of visible light and promotes the generation of photoinduced charge carriers [36]. Furthermore, the formation of a Schottky barrier at the metal-semiconductor interface acts as an efficient electron trap, preventing the recombination of electron-hole pairs and thereby increasing the availability of charge carriers for redox reactions [37] [38].

These composites have demonstrated high efficacy in both pollutant degradation and microbial inactivation. For instance, a composite membrane integrating g-C₃N₄ and Ag₂C₂O₄ achieved a remarkable 7.48 and 7.70 log inactivation of E. coli and S. aureus, respectively, within 80 minutes of visible light irradiation [38].

Doped Semiconductors for Enhanced Performance

Doping is a powerful strategy to modulate the electronic structure of semiconductors, thereby improving their visible-light response and charge separation efficiency.

- Metal Doping: Introducing transition metals like Mn, Co, or Cu into g-C₃N₄ creates mid-gap states that enhance visible-light absorption and serve as active sites for the generation of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS). Mn-doped g-C₃N₄ has been shown to achieve complete inactivation of E. coli (a 6-log reduction) within 6 hours [39].

- Non-Metal Doping: Doping TiOâ‚‚ with non-metal elements like Nitrogen (N) is an effective method to reduce its bandgap, extending its photocatalytic activity from the UV into the visible light region [23].

Ternary Hybrid Photocatalysts

Constructing ternary hybrids, such as Ag/AgBr/g-C₃N₄, combines the advantages of multiple components. In this system, the synergistic effect between Ag/AgBr and g-C₃N₄, coupled with the SPR of Ag NPs, results in a multifaceted improvement: enhanced light absorption, efficient charge separation, and strong redox ability [40]. One study reported that such a ternary hybrid exhibited a hydrogen evolution rate 27 times higher than that of pristine g-C₃N₄ [40].

Table 1: Performance Summary of Selected Photocatalytic Materials

| Material | Application | Performance Metric | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0 wt% Ag/g-C₃Nâ‚„ | MO Degradation | Reaction Rate Constant | 0.0294 minâ»Â¹ (2.3x > pure g-C₃Nâ‚„) | [36] |

| 1.0 wt% Ag/g-C₃N₄ | H₂ Evolution | Hydrogen Production | 20 µmol in 12 h | [36] |

| 5 wt% Ag/exfoliated g-C₃N₄ | MB Degradation | Dye Removal | 94% in 180 min | [37] |

| g-C₃N₄/Ag₂C₂O₄ Membrane | Water Disinfection | Bacterial Inactivation (E. coli / S. aureus) | 7.48 / 7.70 log in 80 min | [38] |

| 18%Ag/AgBr/g-C₃N₄ | H₂ Evolution | Hydrogen Production | 27x > pure g-C₃N₄ | [40] |

| Mn-doped g-C₃N₄ | Water Disinfection | E. coli Inactivation | 6-log reduction in 6 h | [39] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Synthesis of Plasmonic Ag/g-C₃N₄ Nanocomposite

This protocol outlines the preparation of silver nanoparticle-decorated graphitic carbon nitride via a thermal polymerization and chemical reduction method [37].

Materials

- Precursor: Dicyandiamide (Câ‚‚Hâ‚„Nâ‚„)

- Silver Source: Silver nitrate (AgNO₃)

- Reducing Agent: Sodium borohydride (NaBHâ‚„)

Procedure

- Synthesis of Bulk g-C₃Nâ‚„: Place 10g of dicyandiamide in a covered alumina crucible. Heat in a muffle furnace to 500°C for 2 hours using a heating ramp of 4°C minâ»Â¹. Allow to cool to room temperature to obtain bulk g-C₃Nâ‚„ as a yellow solid [37].

- Thermal Exfoliation: Subject the bulk g-C₃Nâ‚„ to a second calcination step at 500°C for 2 hours (ramp: 4°C minâ»Â¹) to obtain exfoliated g-C₃Nâ‚„ nanosheets with a high surface area [37].

- Deposition of Silver Nanoparticles: a. Suspend 500 mg of exfoliated g-C₃N₄ in 100 mL deionized water and stir for 30 minutes. b. Add an aqueous solution of AgNO₃ to achieve the desired Ag loading (e.g., 1-15 wt.%). c. Stir the mixture for an additional 5 minutes. d. Reduce the silver ions by adding a NaBH₄ aqueous solution (Ag/NaBH₄ molar ratio of 1/5) under constant stirring. e. Rinse the resulting solid profusely with deionized water, collect by centrifugation, and dry at 80°C [37].

- Labeling: The final product is labeled as xAg/g-C₃N₄, where x indicates the weight percentage of Ag.

Protocol 2: Evaluation of Photocatalytic Disinfection Activity

This protocol describes a standard procedure for assessing the bactericidal efficacy of the synthesized photocatalysts against model microorganisms like Escherichia coli [39].

Materials

- Test Organism: Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922 or equivalent)

- Culture Media: Luria-Bertani (LB) Broth and LB Agar

- Photocatalyst: The material to be tested (e.g., Ag/g-C₃N₄, doped g-C₃N₄)

- Light Source: Visible light source (e.g., 300 W Xe lamp with a 420 nm cut-off filter)

- Equipment: Serial dilution tubes, colony counter

Procedure

- Bacterial Culture: Inoculate E. coli in LB broth and incubate at 37°C overnight with shaking (150 rpm) to reach the mid-exponential growth phase.

- Cell Harvesting: Centrifuge the bacterial culture, discard the supernatant, and resuspend the pellet in sterile saline solution (0.9% NaCl) to achieve a concentration of approximately 10⸠CFU/mL.

- Photocatalytic Reaction: In a sterile reactor, mix 100 mL of the bacterial suspension with the photocatalyst at a typical concentration of 0.1-1.0 mg/mL. Keep the suspension under constant stirring.

- Dark Adsorption: Prior to illumination, keep the mixture in the dark for 30 minutes to establish adsorption-desorption equilibrium.

- Illumination: Expose the reactor to the visible light source under continuous stirring. Maintain the temperature at 25±2°C using a water-cooling system.

- Sampling and Analysis: a. At predetermined time intervals (e.g., 0, 20, 40, 60, 80 min), withdraw 1 mL aliquots. b. Perform serial dilutions in sterile saline. c. Plate 100 µL of appropriate dilutions onto LB agar plates in duplicate. d. Incubate the plates at 37°C for 24 hours and count the viable colonies.

- Control Experiments: Run two control experiments in parallel: a) with light but no photocatalyst, and b) with photocatalyst but in the dark.

Data Analysis

Calculate the bacterial inactivation using the formula: Inactivation (log CFU/mL) = log(Nâ‚€/N) Where Nâ‚€ is the initial viable cell count (CFU/mL) and N is the viable cell count at time t.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Dicyandiamide | Precursor for g-C₃N₄ synthesis | Thermal condensation temperature (450-600°C) critically affects crystallinity and bandgap [39]. |

| Silver Nitrate (AgNO₃) | Source of Ag⺠ions for nanoparticle formation | Concentration controls Ag loading %; affects SPR intensity and electron trapping [37]. |

| Sodium Borohydride (NaBH₄) | Reducing agent for Ag⺠to AgⰠ| A molar ratio of Ag/NaBH₄ = 1/5 is recommended for complete reduction [37]. |

| Urea | Alternative precursor for g-C₃N₄ | Can yield a more porous structure compared to dicyandiamide [39]. |

| Transition Metal Salts | Precursors for doping (e.g., Mn, Co, Cu) | Introduces mid-gap states, modulating ROS generation pathways and enhancing disinfection [39]. |

Signaling Pathways and Workflow

The photocatalytic sterilization process involves the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that fatally damage bacterial cells. The following diagram illustrates this mechanism and a generalized experimental workflow.

Photocatalytic Sterilization Mechanism and Workflow

This diagram integrates the photocatalytic mechanism with a practical research workflow. The process begins when visible light excites the Ag/g-C₃Nâ‚„ composite, generating electron-hole pairs. The Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) from Ag NPs enhances this light absorption, while the metal-semiconductor interface suppresses charge recombination [36] [37]. The electrons (eâ») reduce surface oxygen to form superoxide radicals (O₂•â»), and holes (hâº) oxidize water to form hydroxyl radicals (•OH) [23]. These highly reactive ROS then attack bacterial cells, causing extensive damage to the cell membrane, intracellular enzymes, and DNA, ultimately leading to cell death [23] [38]. The experimental workflow, from catalyst synthesis to performance evaluation, provides a roadmap for researchers to develop and test new photocatalytic materials.

Photocatalytic disinfection has emerged as a sustainable and efficient advanced oxidation process (AOP) for addressing microbial contamination in water. This technology utilizes semiconductor materials to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) under light irradiation, effectively inactivating a broad spectrum of pathogenic microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, and fungi [41]. Unlike conventional disinfection methods that often involve toxic chemicals, produce harmful by-products, or face issues with microbial resistance, photocatalysis offers an environmentally friendly alternative capable of achieving complete microbial inactivation through redox reactions [41] [42]. The process operates under mild conditions and can be driven by solar energy, making it particularly promising for applications in diverse settings, from centralized water treatment facilities to decentralized systems in resource-limited areas [42] [43].

The fundamental advantage of photocatalytic disinfection lies in its broad-spectrum activity and minimal risk of promoting antimicrobial resistance. As microbial contamination continues to threaten water security globally—with waterborne pathogens causing diseases such as cholera, diarrhea, dysentery, and typhoid—the development of robust, sustainable disinfection technologies becomes increasingly critical [41]. Photocatalysis addresses these challenges by generating powerful, non-selective oxidants that target essential microbial structures and functions, effectively neutralizing diverse pathogens without contributing to the selection of resistant strains [24].

Mechanisms of Microbial Inactivation

Fundamental Photocatalytic Process