Geometry Optimization of Inorganic Compounds: From Foundational Theory to Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of geometry optimization techniques specifically for inorganic and organometallic compounds, a critical yet challenging area in computational chemistry and drug design.

Geometry Optimization of Inorganic Compounds: From Foundational Theory to Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of geometry optimization techniques specifically for inorganic and organometallic compounds, a critical yet challenging area in computational chemistry and drug design. It explores the foundational principles distinguishing inorganic compound optimization from organic molecules, details advanced methodological approaches including DFT and emerging machine learning potentials, and offers practical troubleshooting strategies for convergence and accuracy. Furthermore, it examines rigorous validation protocols and comparative analyses of different methods. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current best practices and innovative trends to enhance the reliability of computational predictions for biomedical applications, facilitating more efficient discovery of novel therapeutics.

Understanding the Fundamentals: What Makes Inorganic Compound Geometry Optimization Unique?

Defining Geometry Optimization for Inorganic Systems

Geometry optimization is a fundamental computational procedure in quantum chemistry and materials science that determines the equilibrium structure of a molecule or material by finding the atomic arrangement that corresponds to the minimum potential energy on the energy surface. For inorganic compounds, which often contain transition metals, lanthanides, actinides, and complex coordination geometries, this process presents unique challenges compared to organic systems. These challenges arise from the presence of d- and f-electrons, greater relativistic effects, more complex electronic configurations, and a wider variety of possible coordination environments [1]. In the context of drug development, geometry optimization of inorganic systems is particularly relevant for metallodrugs, MRI contrast agents, and catalytic systems used in pharmaceutical synthesis.

The accuracy of geometry optimization directly impacts the reliability of subsequent property calculations, including spectroscopic parameters, reaction energies, and electronic properties. As noted in research on metal-radical systems, "An accurate molecular geometry is of major importance for the calculation of the electronic structures and spectroscopic properties" [1]. This is especially critical for inorganic compounds in pharmaceutical applications, where precise geometry affects binding affinity, reactivity, and toxicity profiles.

Fundamental Concepts and Methodologies

Theoretical Foundations

Geometry optimization algorithms iteratively adjust nuclear coordinates until the molecular geometry reaches a stationary point on the potential energy surface, where the root-mean-square (RMS) gradient and maximum gradient component fall below specified thresholds. For inorganic systems, this process must account for open-shell configurations, spin states, and symmetry breaking that commonly occur with transition metal complexes [1].

The optimization process can be expressed mathematically as finding the molecular geometry where the forces on all atoms vanish:

fi = -∂E/∂qi = 0

where E is the total energy and qi are the nuclear coordinates [2]. For complex inorganic systems, this energy minimization must consider multiple potential energy surfaces corresponding to different spin states and electronic configurations.

Computational Workflows

A robust geometry optimization workflow for inorganic systems typically follows these stages:

Table: Stages in Geometry Optimization Workflows for Inorganic Systems

| Stage | Purpose | Recommended Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Structure Preparation | Generate reasonable starting geometry | Molecular mechanics, crystallographic data, chemical intuition |

| Preliminary Optimization | Rough optimization to remove severe strains | Semi-empirical methods, molecular mechanics, or low-level DFT with small basis sets |

| Intermediate Optimization | Refine geometry with better electronic structure treatment | DFT with double-zeta basis sets, accounting for solvation effects |

| Final Optimization | High-accuracy optimization for precise geometry | DFT with triple-zeta basis sets, hybrid functionals, relativistic corrections |

| Validation | Confirm stationary point character | Frequency calculations (no imaginary frequencies for minima, one for transition states) |

The multi-step approach is particularly valuable for challenging inorganic systems, as noted in ORCA documentation: "Depending on the size of your molecule, geometry optimization can be performed in a single submission if the molecule is small or it may require several calculation submissions, moving up through basis sets, if the molecule is large" [3].

Essential Computational Tools and Methods

Density Functional Theory for Inorganic Systems

Density Functional Theory (DFT) has become the predominant method for geometry optimization of inorganic compounds due to its favorable balance between computational cost and accuracy. However, the choice of exchange-correlation functional is critical for inorganic systems, particularly those containing transition metals:

"Pure density functionals, for example, BP86, PBE, TPSS, may take advantage of the use of density fitting to speed up the calculation, which is particularly efficient for the geometry optimizations. However, one has to use them with some caution as they are known to overestimate the covalency of chemical bonds and tend to display a bias toward low-spin states. Hybrid functionals include a fraction of Hartree-Fock (HF) exchange, which strongly favors high-spin states. Hence, these functionals benefit from this error compensation and yield more reliable spin-state energetics" [1].

For specific inorganic elements, specialized functionals may be required. For instance, in cesium-containing compounds, "rev-vdW-DF2 and PBEsol+D3 [were identified] as leading candidates for these systems, in particular with respect to geometry and chemical shifts" [4].

Basis Sets and Relativistic Effects

Basis set selection is crucial for accurate geometry optimization of inorganic compounds:

"In general, DFT calculations are known to converge fast with the size of the basis set. Although polarized double-zeta basis sets are a minimum requirement, polarized triple-zeta basis sets are recommended to obtain more reliable results, especially for the transition metals. In addition, relativistic effects can become important for first row transition metals and heavier elements so that at least scalar relativistic effects should be included in the calculations" [1].

The use of effective core potentials (ECPs) is common for heavier elements, but they have limitations: "ECPs have several limitations and have often been shown to yield less than optimal results for the calculation of spin-state energetics and magnetic properties. Besides, explicit treatment of all electrons is imperative for the determination of spectroscopic parameters and any other properties that require a correct description of the electronic density" [1].

Table: Essential Tools for Geometry Optimization of Inorganic Systems

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application in Inorganic Systems |

|---|---|---|

| DFT Functionals (PBE, BP86, TPSS, B3LYP, PBE0, TPSSh) | Calculate electronic energy and forces | PBE, BP86 for initial optimization; hybrid functionals (B3LYP, PBE0) for final optimization |

| Basis Sets (def2-SVP, def2-TZVP, cc-pVDZ, cc-pVTZ) | Describe atomic orbitals | Double-zeta for preliminary work; triple-zeta for final optimization |

| Effective Core Potentials (ECPs) | Replace core electrons with potentials | Heavier elements (transition metals, lanthanides, actinides) |

| Relativistic Methods (ZORA, DKH) | Account for relativistic effects | Essential for 4d/5d transition metals, lanthanides, actinides |

| Solvation Models (CPCM, COSMO) | Include solvent effects | Crucial for modeling solution-phase chemistry and biological environments |

| Force Fields (UFF, MMFF) | Preliminary optimization | UFF for inorganic elements; MMFF for organometallic systems |

Troubleshooting Common Issues in Geometry Optimization

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My geometry optimization for a transition metal complex fails to converge. What are the most common causes and solutions?

A1: Non-convergence in transition metal complexes often stems from several sources:

- Insufficient SCF convergence: Increase SCF maximum iterations (MaxIter 500-1000) and consider using SCF convergence accelerators (DIIS, KDIIS) [3].

- Poor initial geometry: Use molecular mechanics or semi-empirical methods to generate a better starting structure before DFT optimization [2].

- Inappropriate functional or basis set: Switch to a functional better suited for transition metals (e.g., PBE0, TPSSh, or range-separated hybrids) and ensure adequate basis set size [1].

- Flat potential energy surface: Use tighter convergence criteria or calculate the exact Hessian at the beginning of the optimization [3].

Q2: How can I determine if my optimized structure represents a true minimum or a transition state?

A2: After geometry optimization, perform a frequency calculation:

- True minimum: All vibrational frequencies are real (no imaginary frequencies) [3].

- Transition state: Exactly one imaginary frequency corresponding to the reaction coordinate [5] [6].

- For inorganic systems, particularly those with multiple spin states, verify that you have located the correct minimum on the appropriate spin surface.

Q3: What special considerations are needed for optimizing structures containing heavy elements like cesium, lanthanides, or actinides?

A3: Heavy elements require additional physical considerations:

- Relativistic effects: Use scalar relativistic methods like ZORA or DKH2 [1].

- Dispersion interactions: Include dispersion corrections (D3, D4) as these can be significant for heavy elements [4].

- Basis set selection: Use appropriately large basis sets that account for core-valence correlation or employ ECPs specifically parameterized for heavy elements [1].

- Spin-orbit coupling: For accurate spectroscopy of open-shell heavy element systems, include spin-orbit coupling in single-point calculations after geometry optimization.

Q4: How do I handle multiple possible spin states in transition metal complex optimization?

A4: Transition metal complexes often have multiple accessible spin states:

- Perform separate optimizations for each possible spin state, then compare energies to identify the ground state [1].

- Use broken-symmetry approaches for systems with potential antiferromagnetic coupling.

- Consider functional selection carefully: Pure functionals tend to favor low-spin states, while hybrid functionals with exact exchange favor high-spin states [1].

- Verify spin contamination during optimization by monitoring the 〈S²〉 expectation value.

Q5: What are the best practices for constraining certain coordinates during optimization of inorganic clusters?

A5: Most computational packages allow constrained optimizations:

- In ORCA, use the

Constraintsblock within%geomto fix bonds, angles, or dihedrals [5]. - In PySCF with geomeTRIC, define constraints in a text file specifying fixed distances, angles, or dihedrals [6].

- For inorganic clusters, consider constraining ligand-metal distances when exploring rotational conformers of ligands.

- Use Cartesian constraints when preserving symmetry elements in symmetric inorganic complexes.

Q6: My frequency calculation shows small imaginary frequencies (<50 cmâ»Â¹). Should I be concerned?

A6: Small imaginary frequencies may indicate:

- Numerical artifacts: Particularly in large, floppy systems or with numerical precision issues.

- Insufficient optimization convergence: Try continuing the optimization with tighter convergence criteria [3].

- True transition state: If the imaginary frequency corresponds to a chemically meaningful motion, you may have located a transition state instead of a minimum.

- For values <20 cmâ»Â¹, these are often considered "numerical noise" and can be disregarded, but larger values should be investigated.

Advanced Applications and Emerging Methods

Machine Learning Approaches

Recent advances in machine learning (ML) have created new opportunities for accelerating geometry optimization of inorganic systems:

"Machine-learning (ML) models offer the potential to rapidly evaluate the vast inorganic crystalline materials space to efficiently find materials with properties that meet the challenges of our time. Current ML models require optimized equilibrium structures to attain accurate predictions of formation energies. However, equilibrium structures are generally not known for new materials and must be obtained through computationally expensive optimization, bottlenecking ML-based material screening" [7].

ML-based optimizers show particular promise for high-throughput screening of inorganic materials: "Our ML model can optimize the distorted materials from an initial distortion with a DFT energy of 4.4 down to 0.63 eV/atom" [7].

Transition State Optimization

Locating transition states is particularly important for understanding reaction mechanisms in inorganic and organometallic catalysis. Specialized methods are required:

"In geomeTRIC to search transition state, you can simply add the keyword transition in geomeTRIC input configuration to trigger the TS search module" [6].

For challenging transition state optimizations, more sophisticated approaches may be necessary: "The exact Hessian at the start of the optimization may help. Depending on whether an analytical Hessian is available, one can always use a numerical substitution" [3].

Solid-State and Periodic Systems

For extended inorganic solids, periodic boundary conditions must be employed:

"Geometry optimization by plane wave density function theory with Grimme dispersion correction... In order to obtain a good accuracy on the interatomic distances, you should do a convergence test with respect the cutoff energy and a convergence study associated with the sampling of the Brillouin zone" [2].

Table: Convergence Criteria for Geometry Optimization in Different Codes

| Software | Energy Tolerance (Eh) | Gradient Tolerance (Eh/Bohr) | Displacement Tolerance (Ã…) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ORCA (Normal) | 5e-6 | RMS: 1e-4, Max: 3e-4 | RMS: 2e-3, Max: 4e-3 [5] |

| ORCA (Tight) | More stringent than normal settings | Tighter than normal settings | Tighter than normal settings [3] |

| PySCF (geomeTRIC) | 1e-6 | RMS: 3e-4, Max: 4.5e-4 | RMS: 1.2e-3, Max: 1.8e-3 [6] |

| PySCF (PyBerny) | - | RMS: 1.5e-4, Max: 4.5e-4 | RMS: 1.2e-3, Max: 1.8e-3 [6] |

Geometry optimization for inorganic systems remains a challenging but essential computational task with significant implications for materials science and drug development. The unique electronic structure of inorganic compounds demands careful attention to methodological details, including functional selection, treatment of relativistic effects, and appropriate convergence criteria. Emerging methods, particularly machine learning approaches, show great promise for accelerating the optimization process and enabling high-throughput screening of inorganic materials.

As computational resources continue to grow and methods improve, geometry optimization will play an increasingly important role in the design and discovery of new inorganic compounds with tailored properties for pharmaceutical and technological applications. The development of more efficient optimizers and better physical models will further enhance our ability to predict and understand the structure and behavior of complex inorganic systems.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why does my geometry optimization calculation fail to converge for transition metal complexes with open-shell ligands?

Failed optimizations are often due to the complex electronic structure and challenging potential energy surfaces. Redox-active ligands, such as verdazyls, can have frontier orbitals with energies similar to the metal's d orbitals, leading to delicate electronic states that are difficult to converge [8] [9]. To resolve this, use a multi-step optimization protocol. Start with a robust but computationally inexpensive method (e.g., wB97X-D3 with def2-SVP basis set) to get a rough geometry. Use the resulting orbitals and Hessian (force constants) as starting points for subsequent optimizations with more accurate methods and larger basis sets (e.g., def2-TZVP) [3].

FAQ 2: How does the oxidation state of a redox-active ligand affect the metal-ligand bond and overall geometry?

Oxidation of the ligand can significantly alter its electronic character, which in turn affects the metal-ligand interaction and the ligand field splitting. For instance, in a neutral complex like Ni(dipyvd)â‚‚, oxidation of the dipyvd ligand transforms it from a localized, antiaromatic anion to a planar, delocalized radical. This change increases the ligand's Ï€-acceptor character, which is experimentally observed as an increase in the octahedral ligand field splitting parameter (Δₒ) from approximately 10,500 cmâ»Â¹ to 13,000 cmâ»Â¹ [9]. This change in electronic structure can lead to geometric distortions, necessitating careful optimization.

FAQ 3: What should I do if my frequency calculation reveals imaginary frequencies after optimization?

A single imaginary frequency indicates a transition state, while multiple suggest an optimization failure. First, try restarting the optimization with tighter convergence criteria (e.g., TightOpt in ORCA) [3]. If the issue persists, the structure is likely trapped on a saddle point. Use a utility like orca_pltvib to visualize the vibrational mode corresponding to the imaginary frequency. Manually displace the geometry along this mode and use this new structure as the input for a new, multi-step optimization routine that includes an initial frequency calculation to generate a good starting Hessian [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inaccurate Electronic Energy Due to Poor Geometry

Description The optimized geometry does not represent a true minimum on the potential energy surface, leading to incorrect energies, properties, and vibrational spectra.

Solution A stepwise optimization strategy ensures the structure is at a minimum before advancing to higher levels of theory.

Step-by-Step Instructions:

- Initial Rough Optimization: Perform the first optimization with a fast functional and a small basis set (e.g.,

! wb97X-D3 def2-SVP Opt NumFreq). This provides a reasonable starting structure [3]. - Solvent Introduction: Use the output files (

.gbwfor orbitals,.hessfor Hessian,.xyzfor coordinates) from the first step as inputs for a second optimization that includes the solvent model (e.g.,! CPCM(water)) [3]. - Final High-Accuracy Optimization: Use the outputs from the solvated calculation as the starting point for a final optimization with a larger basis set and a finer integration grid (e.g.,

! wb97X-D3 def2-TZVP Opt NumFreq Grid4) [3]. - Frequency Verification: After each step, confirm the structure is a minimum by checking for the absence of imaginary frequencies in the frequency calculation output.

Problem: Handling Complex Metal-Ligand Orbital Interactions

Description In complexes with redox-active or "non-innocent" ligands, metal and ligand orbitals can mix significantly, making it difficult to assign oxidation states and achieve a stable SCF convergence during optimization.

Solution Employ computational techniques that can accurately describe near-degenerate electronic states and provide a good initial guess for the wavefunction.

Step-by-Step Instructions:

- Stable Wavefunction Check: After an initial SCF calculation, run a stability analysis to check if the wavefunction corresponds to a true minimum or if a lower-energy state exists with a different spin or spatial symmetry.

- Forced Orbital Mixing: If the wavefunction is unstable, use the

! Allowkeyword in ORCA (e.g.,! Allow Occand! Allow Virt) to relax the orbital constraints and achieve a stable solution. - Broken-Symmetry Approach: For systems with potential antiferromagnetic coupling between metal and ligand radicals, use a broken-symmetry (BS) DFT approach to approximate the open-shell singlet state.

- Multi-Reference Methods: For particularly challenging cases where single-reference DFT fails, consider using multi-reference methods like CASSCF/NEVPT2, though these are computationally very demanding.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Experimental Electrochemical and Spectroscopic Data for [M(dipyvd)â‚‚] Complexes

This table summarizes key experimental findings for complexes with the redox-active verdazyl ligand, highlighting ligand-based oxidation and its effects [9].

| Metal Ion | Oxidation Potentials (V vs Fc/Fcâº) | Ligand Field Splitting (Δₒ in cmâ»Â¹) | Electronic Structure Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zinc (Zn²âº) | -0.28 V, -0.12 V | ~10,500 (neutral) | Oxidation is ligand-based, not metal-based [9]. |

| Nickel (Ni²âº) | -0.32 V, -0.15 V | ~10,500 (neutral) ~13,000 (oxidized) | Strong magnetic exchange; oxidation increases Ï€-acceptor character of the ligand [9]. |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Complex Inorganic Synthesis

Essential materials and their functions for synthesizing and studying complexes with redox-active ligands, based on cited experimental work [9].

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Tridentate Leucoverdazyl Ligand (dipyvdH) | Acts as a redox-active, "non-innocent" ligand that can participate in electron transfer processes and tune metal properties [9]. |

| Metal Triflates (e.g., Ni, Zn) | Used as metal precursors for coordination chemistry synthesis [9]. |

| Triethylamine | A base used in the synthesis to deprotonate the ligand and facilitate the formation of neutral coordination compounds [9]. |

| Acetonitrile / Dichloromethane | Common solvents for synthesis, electrochemical studies, and UV-Vis spectroscopy [9]. |

| Platinum Electrode | Working electrode for cyclic voltammetry experiments to study redox behavior [9]. |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology: Synthesis of M(dipyvd)â‚‚ Complexes

This protocol is adapted from procedures for synthesizing neutral coordination compounds with the tridentate leucoverdazyl ligand [9].

- Reaction Setup: In a suitable vessel, combine the ligand

dipyvdHand the metal triflate (e.g., Ni or Zn) in a molar ratio of approximately 2:1 in acetonitrile. Stir until solids are completely dissolved, forming an orange-red solution [9]. - Evaporation: Remove the solvent by evaporation to yield an orange-red solid.

- Deprotonation and Coordination: Re-dissolve the solid in methanol. Add triethylamine dropwise (e.g., 10 drops) to this clear red solution to act as a base, deprotonating the ligand and promoting coordination to the metal center. A precipitate will form.

- Isolation: Isolate the product by vacuum filtration, washing with cold methanol, to obtain the final complex as a colored powder (e.g., red for Zn).

Detailed Methodology: Electrochemical Characterization

This protocol describes how to obtain the oxidation potentials cited in Table 1 [9].

- Instrument Setup: Perform cyclic voltammetry using a standard three-electrode configuration: a platinum disk working electrode, a platinum wire counter electrode, and a silver/silver chloride (Ag/AgCl) pseudo-reference electrode.

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a solution of the complex (e.g.,

Zn(dipyvd)â‚‚orNi(dipyvd)â‚‚) in acetonitrile with a supporting electrolyte (e.g., 0.1 M tetrabutylammonium hexafluorophosphate, TBAPF₆). - Calibration: Add a small amount of ferrocene as an internal standard. All reported potentials should be referenced to the ferrocene/ferrocenium (Fc/Fcâº) couple.

- Measurement: Run the voltammetry experiment and record the oxidation potentials. The observation of two one-electron oxidation waves is characteristic of ligand-based oxidation in these systems [9].

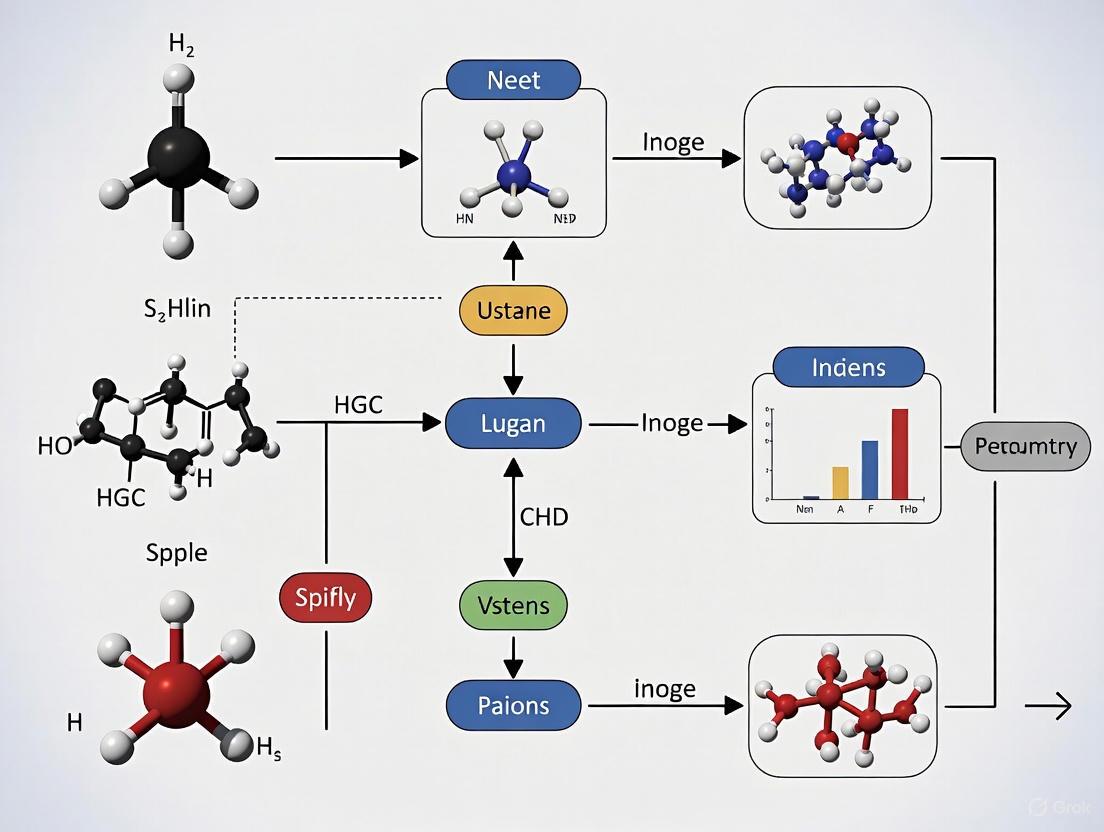

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

Diagram 1: Multi-step geometry optimization and troubleshooting workflow.

Diagram 2: Metal-ligand orbital interactions and electronic effects.

Critical Differences from Organic Compound Optimization

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why do my geometry optimization calculations for inorganic complexes fail to converge?

Inorganic complexes, particularly those containing transition metals, often exhibit complex electronic structures with multiple low-lying spin states, which can cause convergence failures in geometry optimization [1]. This is a critical difference from organic compounds, which typically have well-defined, singlet ground states. Failure often stems from an incorrect initial guess of the spin state or the use of an inappropriate functional. To troubleshoot, first verify the expected spin state of your metal center. Use a stable, pure functional like PBE or TPSS for initial optimizations, as hybrid functionals with Hartree-Fock exchange can sometimes exacerbate convergence issues in challenging cases. Ensure your basis set is adequate; a polarized triple-zeta basis set is recommended for transition metals [1].

Q2: How should I account for relativistic effects in heavy inorganic elements?

Relativistic effects become critically important for elements beyond the first row of transition metals and are a key differentiator from organic compound optimization [1]. These effects significantly impact geometries, bond energies, and spectroscopic properties. For geometry optimization, the recommended approach is to use scalar relativistic all-electron methods, such as the Zeroth-Order Regular Approximation (ZORA) [1]. While Effective Core Potentials (ECPs) offer an alternative by replacing core electrons, they can be less optimal for calculating spin-state energetics and magnetic properties and are generally not recommended for properties that depend critically on the electronic density.

Q3: What is the best DFT functional for optimizing geometries of inorganic compounds?

Selecting a density functional is a nuanced decision for inorganic compounds. While "pure" functionals (e.g., BP86, PBE) are computationally efficient and can be accelerated with density fitting, they may overestimate covalency and exhibit a bias toward low-spin states [1]. Hybrid functionals like B3LYP, which include a portion of Hartree-Fock exchange, often provide better error compensation and more reliable spin-state energetics, making them a popular choice [1]. Other hybrids like PBE0 and TPSSh are also excellent alternatives. The optimal choice may depend on the specific metal and its coordination environment, and testing multiple functionals is advised.

Q4: My synthesized inorganic nanomaterial has poor batch-to-batch reproducibility. What automated solutions can help?

Poor reproducibility in inorganic nanomaterial synthesis, such as for quantum dots or gold nanoparticles, is a common issue arising from the difficulty in manually controlling complex, interrelated reaction parameters [10] [11]. Implementing an automated closed-loop synthesis system can directly address this. These systems integrate automated hardware (e.g., microfluidic reactors or robotic arms) with real-time monitoring (e.g., in-situ UV-Vis spectroscopy) and software algorithms that use machine learning to autonomously optimize process parameters [10] [11]. This "intelligent synthesis" paradigm moves away from traditional trial-and-error, enhancing efficiency, stability, and reproducibility [10] [11].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent Particle Size and Morphology in Nanoparticle Synthesis

- Issue: The synthesized nanoparticles (e.g., AuNPs, SiOâ‚‚) show a wide size distribution or irregular shapes.

- Solution:

- Implement Microfluidics: Utilize an automated microfluidic platform for high-throughput synthesis. This technology provides superior control over mixing and reaction conditions on a microscopic scale, leading to more uniform nucleation and growth [10] [11].

- Real-time Monitoring: Integrate an online optical detection system (e.g., UV-Vis absorption spectroscopy) to monitor the reaction progress and quality of nanoparticles in real-time, allowing for immediate parameter adjustments [10] [11].

- Adopt a Robotic System: A dual-arm robotic system can execute a traditional manual synthesis protocol with higher precision and consistency, significantly reducing human error and improving reproducibility [11].

Problem: Difficulty Scaling Up a Promising Laboratory Synthesis

- Issue: A synthesis procedure that works well on a small, benchtop scale fails when attempting to produce larger quantities, often due to heat and mass transfer limitations.

- Solution:

- Scale-out with Parallel Reactors: Instead of using a single large reactor, employ a millifluidic reactor system capable of gram-scale, high-throughput preparation [10] [11]. This approach maintains the controlled environment of the small-scale synthesis.

- Data-Driven Optimization: Use machine learning algorithms to model the complex, multi-variable relationships between synthesis parameters and product quality. These models can identify optimal conditions for scale-up that may not be intuitive [10] [12].

Quantitative Data for Method Selection

Table 1: Comparison of DFT Functionals for Inorganic Compound Geometry Optimization

| Functional | Type | HF Exchange | Recommended Use Cases | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBE [1] | Pure (GGA) | 0% | Initial geometry scans; large systems (>200 atoms). | Computationally efficient; may overestimate covalency, bias toward low-spin. |

| B3LYP [1] | Hybrid | 20-25% | General-purpose optimization; spin-state energetics. | Good balance of accuracy and cost; widely used and validated. |

| PBE0 [1] | Hybrid | 25% | High-accuracy geometry and property calculations. | Similar to B3LYP, often provides excellent results. |

| TPSSh [1] | Meta-hybrid | ~10% | Systems where standard hybrids fail. | A good alternative when other hybrids struggle with convergence. |

Table 2: Automated Synthesis Hardware for Inorganic Nanomaterials

| System Type | Key Feature | Example Application | Throughput | Reproducibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microfluidic Reactor [10] [11] | Precise control on micro-scale; low reagent consumption. | Synthesis and screening of Quantum Dots (QDs). | High | Excellent |

| Millifluidic Reactor [10] [11] | Gram-scale preparation; integrated real-time characterization. | Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) and nanorods. | Medium-High | Very Good |

| Dual-Arm Robot [11] | Modular; automates standard lab steps (mixing, centrifugation). | Reproducible synthesis of SiOâ‚‚ nanoparticles. | Medium | Excellent |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Geometry Optimization of a Transition Metal Complex Using DFT

This protocol outlines the steps for optimizing the geometry of a metal-radical system, a common challenge in inorganic chemistry [1].

- Initial Structure Setup: Build a reasonable 3D model of the complex using a molecular builder, ensuring correct coordination geometry around the metal center.

- Method and Basis Set Selection:

- Functional: Select a hybrid functional like B3LYP or TPSSh for reliable spin-state energetics [1].

- Basis Set: Use a polarized triple-zeta basis set for all atoms. For transition metals, ensure the basis set is designed for all-electron relativistic calculations [1].

- Relativistic Treatment: Apply a scalar relativistic method, specifically the Zeroth-Order Regular Approximation (ZORA), for any element heavier than the first-row transition metals [1].

- Spin State Definition: Correctly specify the multiplicity (e.g., 2S+1) corresponding to the desired spin state of the system.

- Geometry Optimization Run: Execute the optimization. For systems with 100-200 atoms, this can be computationally demanding but is feasible with modern resources [1].

- Convergence Check: Verify that the optimization has converged for both the geometry and the electronic structure. Analyze the resulting geometry (bond lengths, angles) and vibrational frequencies to confirm it is a minimum (no imaginary frequencies).

Protocol 2: Autonomous Optimization of Quantum Dot Synthesis via Closed-Loop System

This protocol describes an "intelligent synthesis" workflow for optimizing the synthesis of quantum dots, leveraging automation and machine learning [10] [11].

- System Setup: Configure an automated synthesis platform. This typically consists of a microfluidic reactor, programmable syringe pumps for reagent delivery, and an in-line spectrophotometer for real-time optical characterization of the product.

- Define Objective: Quantify the target material property. For QDs, this could be the position of the absorption peak (which correlates with particle size) or the photoluminescence intensity.

- High-Throughput Parameter Screening: Use the platform to automatically perform a series of reactions, varying key synthesis parameters (e.g., precursor concentration, temperature, reaction time) according to a design-of-experiments plan.

- Data Collection and Model Training: For each experiment, record the synthesis parameters and the resulting material properties. Use this dataset to train a machine learning model (e.g., a neural network) to predict material outcomes from synthesis inputs.

- Closed-Loop Optimization: The machine learning model suggests new synthesis parameters expected to yield a product closer to the target. The automated system executes these suggestions, characterizes the new product, and feeds the results back to update the model. This autonomous cycle repeats until the optimal product is achieved.

Research Workflow and Signaling Pathways

Diagram: Intelligent Synthesis Closed-Loop Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for an Automated Inorganic Nanomaterial Synthesis System

| Item | Function | Example in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Microfluidic/Millifluidic Reactor [10] [11] | Provides a controlled environment for reproducible, high-throughput nanomaterial synthesis. | Core component for synthesizing QDs and AuNPs with consistent size and morphology. |

| Programmable Syringe Pumps | Enables precise, automated delivery of liquid precursors with accurate control over flow rates and ratios. | Used to inject precursor solutions into the microfluidic reactor. |

| In-situ Spectrophotometer [10] [11] | Allows for real-time, non-destructive monitoring of the synthesis reaction and product quality (e.g., particle size, concentration). | Integrated into the flow system to monitor QD growth kinetics and AuNP formation. |

| Robotic Manipulator Arm [11] | Automates manual tasks such as mixing, centrifugation, and sample transfer between different stations in a workflow. | Used in a dual-arm setup to automate the entire synthesis protocol for SiOâ‚‚ nanoparticles. |

| Machine Learning Software Platform [10] [12] | Analyzes high-throughput experimental data, builds predictive models, and autonomously decides the next set of experiments to perform. | The "brain" of the closed-loop system that optimizes synthesis parameters for the target nanomaterial. |

| 20-Tetracosene-1,18-diol | 20-Tetracosene-1,18-diol|C24H48O2|RUO | |

| Plumbanone--cadmium (1/1) | Plumbanone--cadmium (1/1), CAS:174539-64-1, MF:CdOPb, MW:335 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is a Potential Energy Surface (PES) and why is it fundamental to computational chemistry?

A Potential Energy Surface (PES) is a multidimensional function that describes the energy of a molecular system as a function of the relative positions of its atomic nuclei. [13] [14] It is a foundational concept in computational chemistry because it provides the "landscape" upon which all molecular geometries and chemical reactions are mapped. [13] [15] By analyzing this landscape, researchers can predict stable molecular structures (minima), identify transition states (saddle points) for chemical reactions, and understand reaction mechanisms and thermodynamics. [13] [16] The PES is inherently based on the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, which assumes that the motion of atomic nuclei and electrons can be separated, allowing the energy to be calculated for fixed nuclear positions. [17] [14]

FAQ 2: What are stationary points on a PES, and how are they classified?

Stationary points are specific geometries on the PES where the energy gradient (the first derivative of energy with respect to nuclear coordinates) is zero. [13] [17] [14] They are critical because they correspond to physically meaningful structures. Stationary points are classified by the curvature of the PES around them, which is determined by the second derivatives. [14]

The two most important types of stationary points are:

- Minima: At a minimum, the curvature is positive in all directions. This corresponds to a stable or metastable molecular structure, such as a reactant, product, or reaction intermediate. [17] [18] A molecule at a minimum will vibrate but will not spontaneously change its geometry.

- Saddle Points (Transition States): A first-order saddle point is characterized by negative curvature in exactly one direction (the reaction coordinate) and positive curvature in all other directions. This represents the highest-energy point on the lowest-energy pathway connecting two minima and corresponds to a transition state in a chemical reaction. [13] [14]

FAQ 3: What is the relationship between a PES and geometry optimization?

Geometry optimization is the computational process of finding a local minimum on the PES. [19] [17] It is an iterative algorithm that starts from an initial guessed molecular structure and then "walks" downhill on the energy landscape until a point with a negligible gradient is found, indicating a stationary point. [17] This optimized geometry represents the most stable structure of the molecule under the given computational model. Most quantum chemical calculations, such as those predicting molecular properties or spectra, must be performed on optimized geometries to yield meaningful and representative results. [17]

FAQ 4: What are internal coordinates and why are they used in geometry optimization?

Internal coordinates describe the molecular geometry in terms of inherent structural parameters such as bond lengths, bond angles, and dihedral angles. [17] This is in contrast to Cartesian coordinates, which define the absolute position of each atom in space.

Using internal coordinates (3N-6 for non-linear molecules, where N is the number of atoms) offers significant advantages for geometry optimization. [17] [18] [15]

- Efficiency: They automatically eliminate the three translational and three rotational degrees of freedom of the entire molecule, which do not affect the energy. [17] This reduces the number of variables the optimizer must handle.

- Chemical Intuition: The optimization process follows chemically meaningful directions (e.g., shortening a bond, bending an angle) rather than arbitrary Cartesian movements, which often leads to faster convergence. [17]

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Geometry Optimization Problems and Solutions

Table: Troubleshooting Common Geometry Optimization Issues

| Problem Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Optimization fails to converge [19] | Poor initial guess for the molecular geometry. [19] | Re-generate the initial molecular structure using a molecular builder or a known crystal structure. |

| Inadequate convergence criteria. [19] | Tighten the convergence thresholds for energy, gradient, and displacement changes. | |

| The algorithm is stuck in a region with a complex PES. | Use a more robust optimization algorithm, such as a Hessian-based method. [19] | |

| Optimization converges to an unexpected structure | The initial geometry was in the vicinity of a different local minimum than the one targeted. | Apply constraints to specific bonds or angles to guide the optimization, or try a different initial geometry. |

| Imaginary frequencies in the results | The located stationary point is a saddle point (transition state), not a minimum. | Verify the nature of the stationary point with a frequency calculation. To find a minimum, follow the normal mode of the imaginary frequency downhill. |

Step-by-Step Protocol for a Successful Geometry Optimization

The following workflow outlines the standard procedure for performing a geometry optimization calculation in computational chemistry software packages.

Protocol Steps:

- Initial Geometry: Obtain a reasonable starting structure for your inorganic compound from databases, crystallographic data, or molecular modeling software. [19]

- Computational Method: Select an appropriate level of theory (e.g., a Density Functional Theory functional) and basis set for your system. [19] [16]

- Run Optimization: Submit the optimization job using the chosen software. The algorithm will iteratively update the geometry to minimize the energy. [17]

- Check Convergence: Verify that the calculation converged by checking the output log for messages confirming that the specified thresholds for energy, gradient, and displacement were met. [19]

- Frequency Calculation: This is a critical and mandatory step. Run a frequency calculation on the optimized geometry. A true minimum will have no imaginary (negative) frequencies. The presence of one imaginary frequency indicates a transition state, while more than one suggests the optimization failed to find a valid stationary point. [14]

Table: Essential Computational Tools for PES Exploration

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Software(e.g., Gaussian, ORCA, GAMESS, xtb) | Software packages that perform the core calculations to compute the energy and gradient for a given molecular geometry, enabling geometry optimization and PES mapping. [17] |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | A computational method that offers a good balance of accuracy and computational cost, making it a popular choice for studying inorganic complexes and their PES. [16] |

| Basis Set | A set of mathematical functions used to represent the molecular orbitals of electrons. The choice of basis set (e.g., 6-31G, cc-pVDZ) impacts the accuracy and cost of the calculation. [19] [16] |

| Solvation Model | A model that accounts for the effects of a solvent environment on the molecular PES, which is crucial for modeling reactions in solution. [17] |

| Visualization Software(e.g., GaussView, Avogadro, VMD) | Tools used to build initial molecular structures, visualize optimized geometries, and analyze computational results. |

Advanced PES Analysis: Reaction Coordinates and Saddle Points

For inorganic chemistry research, especially in catalysis, understanding the pathway of a reaction is as important as knowing the stable intermediates. The reaction coordinate is the lowest-energy path on the PES connecting reactants to products. [13] [18] The highest point on this path is the transition state (a first-order saddle point). The energy difference between the reactants and the transition state is the activation energy, which determines the reaction rate.

The diagram below illustrates the key concepts of a PES for a simple reaction, showing the relationship between minima, the transition state, and the reaction coordinate.

The Crucial Link Between Accurate Geometry and Predictive Property Calculations

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Geometry Optimization

This technical support center provides solutions for researchers facing challenges in geometry optimization of inorganic compounds, a foundational step for obtaining accurate predictive property calculations in fields like materials science and drug development [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Imaginary Frequencies in Vibrational Analysis

- Problem: After a successful geometry optimization, the subsequent frequency calculation yields one or more imaginary frequencies (negative values in cmâ»Â¹), indicating a transition state rather than the desired energy minimum [3].

- Diagnosis: An imaginary frequency typically means the structure is stuck on a saddle point of the potential energy surface. The optimization has found a stationary point where the gradient is zero, but the curvature is negative along at least one vibrational mode [20].

- Solution: A multi-step procedure is recommended to guide the structure to the nearest local minimum [3].

- Tighten Convergence: First, attempt a re-optimization using tighter convergence criteria (e.g.,

TightOptin ORCA) [3] [5]. - Structural Deformation: If the imaginary frequency persists, deform the molecular structure along the imaginary vibrational mode.

- Hessian Recalculation: For stubborn cases, recalculate the Hessian (force constant matrix) more frequently during the optimization. This is computationally expensive but can be necessary for flat potential energy surfaces [3].

- Tighten Convergence: First, attempt a re-optimization using tighter convergence criteria (e.g.,

Guide 2: Addressing Slow or Failed Optimization Convergence

- Problem: The geometry optimization cycle exceeds the maximum number of steps without converging or progresses extremely slowly [19].

- Diagnosis: This can be caused by a poor initial geometry, an inadequate level of theory, or a very flat potential energy surface [19] [20].

- Solution:

- Improve Initial Guess: Always start with the best possible initial structure, obtained from experimental data or a cheaper computational method (e.g., molecular mechanics or semi-empirical) [20].

- Multi-Step Strategy: For large or complex systems (e.g., transition metal complexes), use a multi-step approach [3]:

- Step 1: Optimize with a fast, lower-level method (e.g., semi-empirical PM6 or DFT with a small basis set like def2-SVP).

- Step 2: Use the optimized geometry, orbitals (

.gbwfile), and Hessian (.hessfile) from the first step as the starting point for a higher-level calculation (e.g., DFT with a larger basis set like def2-TZVP) [3]. - This provides a better starting Hessian, reducing the number of steps needed in the expensive final optimization [3].

- Adjust Optimization Parameters: Loosen convergence criteria (

Convergence loose) [5] or increase the maximum number of iterations (MaxIter) [5] for difficult cases. For systems with flat potential energy surfaces, using a Hessian-based optimizer can be more efficient [19].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is geometry optimization a critical step before calculating properties like NMR or vibrational spectra? Geometry optimization finds the minimum energy configuration of a molecule [19] [20]. Molecular properties are highly dependent on this structure. Calculating properties on an unoptimized or transition-state geometry will yield incorrect results because the electronic structure is not representative of the stable molecule. The vibrational frequencies, for instance, are only physically meaningful at a true energy minimum (no imaginary frequencies) [3].

FAQ 2: How does the choice of functional and basis set impact geometry optimization for inorganic compounds? The functional and basis set define the accuracy and computational cost of the calculation [19].

- Functional: For inorganic compounds, particularly those with transition metals, hybrid functionals (e.g., B3LYP, PBE0) or modern meta-GGA functionals (e.g., M06-L, M06-2X) are often necessary to adequately describe electron correlation [19]. Dispersion corrections (e.g., -D3) are crucial for capturing weak intermolecular forces [3].

- Basis Set: Larger basis sets (e.g., def2-TZVP) provide higher accuracy but at greater cost. A common strategy is to optimize with a moderate basis set (e.g., def2-SVP) and perform a single-point energy calculation with a larger basis set [3] [19]. For heavy elements, effective core potentials (ECPs) are often used.

FAQ 3: What is the role of symmetry and constraints in geometry optimization? Using symmetry can significantly reduce computational cost by decreasing the number of degrees of freedom that need to be optimized [20]. Constraints are used to freeze specific coordinates (e.g., a bond length, angle, or dihedral) during an optimization. This is useful for scanning a potential energy surface or studying a part of a molecule while keeping the rest fixed [5]. However, improper use of constraints can prevent the molecule from reaching its true minimum.

FAQ 4: How is machine learning (ML) being used to address challenges in geometry optimization? ML offers a paradigm shift for high-throughput screening. Traditional ab initio optimization is too slow for searching vast material spaces [7]. ML models, particularly graph neural networks, can be trained on existing density functional theory (DFT) data to predict energies and forces [21] [7]. They can act as ultra-fast "force fields" to optimize structures before more accurate DFT calculations, dramatically accelerating the discovery of new materials and catalysts [7]. For example, one ML-based optimizer reduced the mean absolute error in formation energy predictions for distorted structures from 0.48 eV/atom to 0.12 eV/atom [7].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Methodology: Multi-Step DFT Geometry Optimization

This protocol details a robust multi-step geometry optimization for an inorganic compound using the ORCA software package, moving from a lower-level to a higher-level of theory to ensure convergence [3].

Workflow: Multi-Step Geometry Optimization

Step-by-Step Instructions:

- Initial Setup: Generate a reasonable 3D structure using a molecular builder like Avogadro and export it as a

.xyzfile [3]. - Step 1 - Low-Level Optimization:

- Purpose: A cheap pre-optimization to get close to the minimum.

- Input:

- Output:

first.xyz,first.gbw(orbitals),first.hess(Hessian).

- Step 2 - Medium-Level Optimization (with Solvent):

- Purpose: Refine the geometry with a solvent model.

- Input:

- Output:

second.xyz,second.gbw,second.hess.

- Step 3 - High-Level Optimization:

- Purpose: Final optimization with a larger basis set and finer integration grid.

- Input:

- Validation: After each step, run a frequency calculation (

NumFreq). The final structure is valid only if the frequency calculation shows no imaginary frequencies, confirming a true energy minimum has been found [3].

Quantitative Data on Geometry Optimization Impact

The accuracy of the initial geometry has a direct and quantifiable impact on the prediction of material properties. The following table summarizes data from a study on machine-learning-based optimization, demonstrating how structural optimization improves the prediction of key properties [7].

Table 1: Impact of Structural Optimization on ML Property Prediction Accuracy

| Material Property | Input Structure Type | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | Root-Mean-Squared Error (RMSE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formation Energy (eV/atom) | Distorted Structure | 0.48 | 0.60 |

| ML-Optimized Structure | 0.12 | 0.22 | |

| True Ground-State (DFT) | 0.09 | 0.16 | |

| Band Gap (eV) | Distorted Structure | 0.72 | 0.97 |

| ML-Optimized Structure | 0.41 | 0.57 | |

| True Ground-State (DFT) | 0.34 | 0.48 |

Source: Adapted from data in [7].

Table 2: Typical Accuracy of QSPR-Based Property Prediction for Organic Compounds

| Property | Units | Typical Error |

|---|---|---|

| Boiling Point | K | 15 K |

| Melting Point | K | 35 K |

| Enthalpy of Fusion | kJ/mol | 4 kJ/mol |

| Liquid Density | kg/L | Uses Molar Vol. |

| Solubility Parameter | (cal/cm³)^0.5 | 0.7 |

Source: Data from [22]. Note: Accuracy decreases for molecules outside the model's training domain, such as many inorganic compounds.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for Geometry Optimization and Property Prediction

| Tool Name / "Reagent" | Type | Primary Function in Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| ORCA | Software Suite | A comprehensive quantum chemistry package capable of running DFT, post-Hartree-Fock, and semi-empirical calculations for geometry optimization and frequency analysis [3] [5]. |

| Density Functional Theory | Method | A quantum mechanical method used to calculate electronic structure. It offers a good balance of accuracy and computational cost, making it the workhorse for optimizing inorganic compounds [23] [19]. |

| Basis Set (e.g., def2-SVP, def2-TZVP) | Mathematical Basis | A set of functions used to represent molecular orbitals. Larger basis sets (def2-TZVP) are more accurate but more costly than smaller ones (def2-SVP) [3] [19]. |

| Solvation Model (e.g., CPCM) | Model | Implicitly models the effect of a solvent (e.g., water) on the molecular structure and energy, which is critical for simulating realistic conditions [3]. |

| Avogadro | Software | A molecular editor and visualizer used for constructing initial molecular geometries and visualizing optimized structures or vibrational modes [3]. |

| Crystal Graph Convolutional Neural Network | Machine Learning Model | A graph neural network designed for crystalline materials that can predict material properties and, with augmented training, be used for geometry optimization [7]. |

| Aceanthrylen-8-amine | Aceanthrylen-8-amine|High Purity|RUO | Aceanthrylen-8-amine is a high-purity PAH amine for materials science research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 1,3-Diazido-2-methylbenzene | 1,3-Diazido-2-methylbenzene|High Purity | 1,3-Diazido-2-methylbenzene for research applications. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for diagnostic, therapeutic, or personal use. |

Methodologies in Action: DFT, Machine Learning, and Practical Workflows

Troubleshooting Guides

Geometry Optimization Non-Convergence

Problem: Your geometry optimization calculation fails to converge within the specified number of steps.

Solutions: Table 1: Troubleshooting Steps for Optimization Non-Convergence

| Step | Action | Rationale | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Check initial geometry | A poor initial guess can prevent convergence [19]. | Removes steric clashes or unphysical bonds. |

| 2 | Loosen convergence criteria | Overly tight criteria (e.g., Max force < 10^-6) may be unnecessary [19]. |

Faster convergence for initial scans. |

| 3 | Switch optimization algorithm | Use Quasi-Newton (BFGS) for simple, Hessian-based for complex systems [19]. | More efficient convergence pathway. |

| 4 | Verify basis set/functional | Inadequate choices (e.g., small basis set) are a common pitfall [19]. | Improved accuracy and convergence behavior. |

Unrealistic Interaction Energies in DFT

Problem: Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations yield intermolecular interaction energies that seem too large or too small compared to expected values or benchmark data.

Solutions: Table 2: Troubleshooting Unrealistic DFT Interaction Energies

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Overestimated attraction | Excessive charge transfer contribution from certain functionals (e.g., PW91) [24] [25]. | Switch to a hybrid functional (e.g., B3LYP) and compare results. |

| Underestimated attraction | Poor description of dispersion forces (van der Waals interactions). | Employ a functional with dispersion corrections (e.g., DFT-D3). |

| Inconsistent trends | Inadequate functional choice for the specific system [19]. | Consult literature for functionals known to perform well for similar inorganic complexes. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: When should I use Hartree-Fock (HF) over DFT for my inorganic complex?

A1: Hartree-Fock is often suitable for initial scans or pre-optimizations due to its speed, especially for large systems. However, for final, accurate results on inorganic compounds—which often contain transition metals with significant electron correlation—DFT is generally necessary. HF fails to describe electron correlation, which is crucial for realistic interaction energies and properties like dispersion [24] [19].

Q2: My system is too large for a full QM treatment. What are my options?

A2: For large systems like proteins or materials with thousands of atoms, Molecular Mechanics (MM) is the primary practical method. You can derive accurate, system-specific MM parameters by fitting them to quantum mechanical (QM) data using automated tools like ParaMol [26] or iterative parameterization protocols [27]. This ensures the MM force field closely mimics the QM potential energy surface.

Q3: How do I choose a functional for my transition metal complex geometry optimization?

A3: The choice depends on the system, but some general guidelines exist [19]:

- GGA functionals (e.g., PBE): Often a good starting point for systems with delocalized electrons.

- Hybrid functionals (e.g., B3LYP, PBE0): Preferred for systems where electron correlation is important, as they mix in a portion of HF exchange. They are widely used for transition metal complexes [19].

- Meta-GGA functionals (e.g., M06-L, M06-2X): Can offer higher accuracy for diverse properties, including transition metals.

Q4: What is a critical pitfall in comparing HF and DFT interaction energies?

A4: A key difference lies in the charge transfer contribution. Studies using the Constrained Space Orbital Variation (CSOV) method have shown that the charge transfer contribution in DFT can be up to twice as large as in HF [24] [25]. This can lead to DFT overestimating the stability of certain complexes if the functional is not carefully chosen.

Method Selection Workflow

Use the following diagram to guide your choice of computational method. The workflow is based on system size, accuracy requirements, and key considerations from computational research [28] [19] [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Geometry Optimization

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| xTB/DFT Workflow [28] | Software Methodology | Rapid geometry optimization and stability evaluation of complex isomers (e.g., Ga-HBED complexes). |

| Constrained Space Orbital Variation (CSOV) [24] [25] | Analysis Technique | Decomposes interaction energies to understand differences between HF and DFT results, highlighting charge transfer effects. |

| ParaMol [26] | Software Package | Automates parameterization of Molecular Mechanics force fields by fitting to ab initio data for drug-like molecules. |

| Iterative Parameterization [27] | Computational Protocol | Automates force field fitting via cycles of QM calculation and MM parameter optimization, improving accuracy and preventing overfitting. |

| Basis Sets (e.g., cc-pVTZ, 6-311G) [19] | Mathematical Basis | Set of functions to describe molecular orbitals; choice balances computational cost and accuracy. |

| Hybrid Functionals (e.g., B3LYP) [19] | DFT Functional | Includes a mix of HF and DFT exchange, often providing superior accuracy for inorganic systems with electron correlation. |

| 2'-Methyl-2,3'-bipyridine | 2'-Methyl-2,3'-bipyridine, CAS:646534-79-4, MF:C11H10N2, MW:170.21 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 11H-Benzo[a]fluoren-3-amine | 11H-Benzo[a]fluoren-3-amine|Research Chemical |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common DFT Issues for Inorganic Systems

This section addresses frequent challenges encountered during geometry optimization of inorganic compounds.

How do I resolve errors that my pseudopotential or atom type is not recognized?

Problem: The calculation fails because the Hubbard atom or element is not recognized by the code [29].

Solution:

- Check Element Validity: Confirm your element is conventional for Hubbard terms. Most transition metals (e.g., Ti-Zn, Zr-Cd, Hf-Hg), rare earths, and light elements like H, C, N, O are often included by default. If your element is not listed, you may need to manually add it to the code's source files (e.g.,

set_hubbard_l.f90) [29]. - Inspect Pseudopotential Header: Verify the

PP_HEADERin your pseudopotential file correctly specifies the element, as this is how the code identifies it [29]. - Verify Species Ordering: Ensure the

Hubbard_U(n)parameter is assigned to the correct speciesnas listed in theATOMIC_SPECIESnamelist, not the order inATOMIC_POSITIONS[29].

Why does my occupation matrix show unexpected values (e.g., >1, NaN)?

Problem: The occupation matrix, which should ideally have maximum values around 1, shows non-normalized occupations (e.g., ~1.03 to 2.5) or NaN values [29].

Solution:

- Test Single Atom: Calculate the energy and occupation matrix of a single atom with symmetry turned off to test the pseudopotential [29].

- Change Projection Type: For non-normalized occupations, switch the

U_projection_typetonorm_atomic. Note that this may prevent force and stress calculations without further fixes [29]. - Check Compiler/Libraries: For NaN results, investigate potential issues with your compiler or mathematical library versions, as these can be the source of the problem [29].

The geometry changes dramatically after applying a +U term. What is wrong?

Problem: DFT+U, especially with large U values, can over-elongate bonds, causing optimized structures to differ significantly from DFT structures [29].

Solution:

- Achieve Structural Consistency: Implement a structurally consistent U procedure. Calculate U at the DFT level, relax the structure with that U value, then recompute U on the new structure, iterating until convergence [29].

- Consider Covalency with +V: For systems with significant covalency (e.g., metal oxides), use DFT+U+V, which includes an intersite interaction term (

V) to better handle electron delocalization [29]. - Constraint Methods: As a diagnostic, constrain metal-ligand bond lengths to their DFT-optimized values and observe the angular dependence to see if the correct potential energy surface is recovered [29].

How can I avoid spurious low-frequency modes and entropy errors?

Problem: Incorrectly treated low-frequency vibrational modes can lead to explosions in entropic corrections, skewing predictions of reaction barriers and selectivity [30]. Neglecting molecular symmetry numbers also introduces error [30].

Solution:

- Apply Frequency Cutoff: Use the recommended Cramer-Truhlar correction by raising all non-transition-state vibrational modes below 100 cmâ»Â¹ to 100 cmâ»Â¹ for entropy calculations [30].

- Account for Symmetry: Always include the correct symmetry number for each species. The symmetry number is automatically detected and applied by modern software like the

pymsymlibrary [30]. For example, the deprotonation of water (symmetry number σ=2) to hydroxide (σ=1) requires a free energy correction of ( RT\,ln(2) ), which is 0.41 kcal/mol at room temperature [30].

What are the best practices for SCF convergence and integration grids?

Problem: The Self-Consistent Field (SCF) procedure fails to converge, or energies and free energies exhibit unexpected oscillations or dependence on molecular orientation [30].

Solution:

- Use Larger Integration Grids: Modern functionals (especially mGGAs like M06 and SCAN, or B97-based ones like wB97M-V) are sensitive to grid size. Avoid small default grids. A (99,590) grid or its equivalent is recommended for all types of calculations to ensure rotational invariance and accuracy, particularly for free energies [30].

- Employ Robust SCF Algorithms: Use a hybrid DIIS/ADIIS strategy, apply a default level shift (e.g., 0.1 Hartree), and use tight two-electron integral tolerances (e.g., 10â»Â¹â´) to improve convergence [30].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the best functional and basis set for inorganic complex geometry optimization?

The "best" choice balances accuracy, robustness, and computational cost. Outdated defaults like B3LYP/6-31G* are known to perform poorly due to missing dispersion interactions and significant basis set superposition error (BSSE) [31]. Modern, more robust alternatives are recommended.

The table below summarizes recommended method combinations for different tasks.

Table 1: Recommended DFT Protocols for Inorganic Systems

| Task | Recommended Functional | Recommended Basis Set / Composite Method | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Geometry Optimizations | B97M-V [31], r²SCAN-3c [31] | def2-SVPD [31] (for B97M-V), implicit in r²SCAN-3c | Include dispersion corrections (D3, D4); r²SCAN-3c is a good composite method. |

| Geometry Optimizations (Lanthanoids) | GFN-xTB (low-cost pre-optimization) [32] | GFN-xTB [32] | Fast, reasonable structures for conformational search; benchmarked on 80 Ln complexes. |

| Single-Point Energies | Double-hybrid functionals (e.g., DLPNO-CCSD(T) as high-level alternative) [31] | def2-TZVP, def2-QZVP [31] | Use on optimized geometries for higher accuracy in energy evaluation. |

My system has open-shell transition metals. How do I handle multi-reference character?

While most closed-shell molecules are single-reference, open-shell systems like radicals or some transition-metal complexes can have multi-reference character [31].

- Check for Low-Lying States: Perform an unrestricted broken-symmetry DFT calculation to check for low-lying triplet or other electronic states [31].

- Converge Multiple States: Be aware that different values of the Hubbard U parameter can stabilize different electronic solutions. Always attempt to converge to the lowest-energy electronic state at your geometry [31].

Can I compare total energies from calculations using different U values?

No, not directly. Standard DFT+U implementations make total energies from calculations with different U values incomparable due to energy shifts [29].

- Compare at Average U: The recommended practice is to compare different structures at a single, average value of U [29].

- Advanced Methods: Research into "DFT+U(R)" methods that incorporate variation of U with atomic position is ongoing, which aims to address this issue directly [29].

How can I efficiently get optimized structures for machine learning screening?

Machine learning (ML) models for material properties require optimized structures, but DFT relaxation is a bottleneck [7].

- ML-Based Optimizer: Use an ML-based geometry optimizer. Models trained on both ground-state and strained structures can predict energy changes and optimize atomic positions via a Monte-Carlo search, reducing the need for full DFT relaxations [7].

- Improved Predictions: Using ML-optimized structures before property prediction can reduce the mean absolute error (MAE) in formation energy from 0.48 eV/atom (distorted input) to 0.12 eV/atom, a 4x improvement [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Computational Reagents

Table 2: Key Software and Method Components

| Item | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Dispersion Correction (D3, D4) | Accounts for long-range van der Waals interactions, critical for structure and binding energy. | Modeling adsorption on surfaces or supramolecular interactions. |

| Pseudopotential (PP) | Represents core electrons, reducing computational cost for heavy elements. | Calculations on 4d/5d transition metals or lanthanides. |

| Hubbard U Parameter | Corrects for self-interaction error in localized d/f-electron states. | Modeling electronic structure of metal oxides (e.g., NiO). |

| Solvation Model | Implicitly models solvent effects (SMD, COSMO). | Calculating redox potentials or reaction energies in solution. |

| GFN-xTB Method | A fast, semi-empirical tight-binding method for large systems. | Conformational searching of large lanthanide complexes [32]. |

| 15-Methylpentacosanal | 15-Methylpentacosanal|High-Purity Reference Standard | High-purity 15-Methylpentacosanal for research use only (RUO). Explore this certified reference standard for your lipidomics and chemical studies. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| C19H16Cl2N2O5 | C19H16Cl2N2O5|High-Purity Reference Standard|RUO | C19H16Cl2N2O5: A high-purity chemical reagent for research applications. For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic, therapeutic, or personal use. |

Workflow and Protocol Visualization

Geometry Optimization Workflow

The following diagram outlines a robust decision-making workflow for the geometry optimization of inorganic compounds, incorporating checks and best practices.

Functional Selection Logic

This diagram provides a logical guide for selecting an appropriate density functional based on the system composition and target property.

The Rise of Machine Learning Potentials like ANI-2x

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Reproducing Published ANI-2x Benchmark Results

Problem: Inability to reproduce published RMSE values (e.g., ~38.6 meV for energies, ~84.4 meV/Ã… for forces on a 300K test set) when evaluating the ANI-2x potential [33].

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Verify Input Data Integrity

- Action: Ensure you are using the exact same dataset as the original publication.

- Check: Use checksums to confirm files have not been corrupted during download. Validate that molecular geometries and reference energies/forces match the benchmark's source.

Inspect the Potential Implementation

- Action: Compare your implementation against the official code from the Roitberg group.

- Check: If using a custom implementation, scrutinize the code for errors in the potential function, unit conversions, and the application of cutoffs or smoothing functions [33].

Review the Evaluation Procedure

- Action: Ensure your RMSE calculation methodology matches the benchmark.

- Check: Confirm you are using the same weighting scheme, and averaging over the identical set of molecules and configurations [33].

Audit Your Software Environment

- Action: Document and compare versions of key software libraries.

- Check: Incompatibilities between different versions of the ANI toolkit, PyTorch, or other dependencies can lead to divergent results. Using a virtual environment is recommended [33].

Guide 2: Addressing Geometry Optimization Convergence Failures

Problem: Geometry optimization calculations using ANI-2x fail to converge to a minimum energy structure.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Improve the Initial Geometry

- Action: Provide a better initial guess for the molecular structure.

- Check: Avoid high-energy, strained conformations as starting points. Pre-optimization with a fast, low-level method can help [19].

Select a Robust Optimization Algorithm

- Action: Use an algorithm designed for machine learning potentials.

- Check: The Conjugate Gradient with Backtracking Line Search (CG-BS) algorithm has been shown to work effectively with the ANI-2x potential, helping to navigate its potential energy surface [34].

Tighten Convergence Criteria

- Action: Use stricter thresholds for energy, gradient, and displacement changes.

- Check: Standard criteria include energy change (ΔE < 10â»â¶ Hartree), gradient norm (||g|| < 10â»â´ Hartree/Bohr), and displacement (||d|| < 10â»Â³ Bohr) [19].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What do I do if my ANI-2x results do not match published benchmarks? A: Follow a systematic checklist [33]:

- Data: Verify the integrity and correctness of your input dataset.

- Code: Meticulously review your implementation of the potential against the official version.

- Method: Ensure your evaluation metrics (e.g., RMSE formula, weighting) are identical.

- Community: Consult the original publication's supplementary materials and consider contacting the authors or seeking help on dedicated computational chemistry forums.

Q2: How can I assess the reliability of an ANI-2x energy prediction? A: The ANI-2x potential uses an ensemble of 8 neural networks. The standard deviation of the predictions from these networks serves as an uncertainty metric. A small standard deviation indicates the molecule is likely similar to those in the training set, suggesting higher reliability. A large standard deviation is a warning that the prediction may be less trustworthy [35].

Q3: What are the best practices for ensuring geometry optimization converges successfully? A: Key practices include [19]:

- Initial Guess: Start with a reasonable, low-energy molecular geometry.

- Algorithm Choice: Select an optimization algorithm suited to your system; for ANI-2x, CG-BS is recommended [34].

- Convergence Settings: Apply appropriate convergence thresholds for energy, gradient, and displacement.

Q4: For which chemical systems is ANI-2x applicable? A: The ANI-2x potential is parameterized for organic molecules containing the elements Hydrogen (H), Carbon (C), Nitrogen (N), Oxygen (O), Sulfur (S), Fluorine (F), and Chlorine (Cl). Predictions for molecules containing atoms outside this set will be unreliable [34].

Experimental Data and Protocols

Key Performance Metrics of ML Potentials

The following table summarizes quantitative data related to the performance and application of machine learning potentials like ANI-2x.

Table 1: Performance Metrics and Computational Results

| Potential / Model | Target System | Key Metric | Reported Value | Reference / Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANI-2x | 300K Test Set (Organic Molecules) | Energy RMSE | ~38.6 meV | [33] |

| ANI-2x | 300K Test Set (Organic Molecules) | Force RMSE | ~84.4 meV/Ã… | [33] |

| ANI-1ccx | Isomerization Reaction (e14.xyz → p14.xyz) | Reaction Energy | +6.9 kcal/mol | Compared to CCSD(T) reference of +5.30 kcal/mol [35] |

| State-of-the-Art uMLIPs | Mixed Dimensionality Systems | Avg. Energy Error | < 10 meV/atom | [36] |

| State-of-the-Art uMLIPs | Mixed Dimensionality Systems | Avg. Position Error | 0.01–0.02 Å | [36] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Calculating Reaction Energies with ANI-1ccx

This protocol outlines the steps to calculate a gas-phase reaction energy using the ANI-1ccx potential, which is closely related to ANI-2x but fitted to high-level CCSD(T) reference data [35].

1. System Setup and Calculation Initialization

- Start your computational environment (e.g., AMSinput).

- Set the calculation Task to

Single Point. - Set the computational engine to

ML Potentialand select ModelANI-1ccx.

2. Molecular Structure Input

- Import the 3D coordinates for the reactant molecule (e.g.,

e_14.xyz). - Save the job (e.g., as

mol1_singlepoint.ams) and run it. - Repeat the process for the product molecule (e.g.,

p_14.xyz).

3. Energy Extraction and Analysis

- Upon job completion, open the output file.

- Locate the

Energyin theCALCULATION RESULTSsection for both reactant and product. - Calculate the reaction energy:

ΔE = E_product - E_reactant. - Convert the energy difference from Hartree to your desired unit (e.g., kcal/mol). 1 Hartree ≈ 627.5 kcal/mol.

Example Python Script using PLAMS:

Workflow Visualization

ANI-2x Geometry Optimization Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the iterative process of geometry optimization using the ANI-2x potential, which is crucial for tasks like binding pose refinement in drug discovery [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Relevance to Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| ANI-2x Potential | A machine learning potential that provides DFT-level (wB97X/6-31G(d)) accuracy for molecules containing H, C, N, O, S, F, Cl at a fraction of the cost. | Primary engine for energy and force calculations in geometry optimization and molecular dynamics [34]. |

| ANI-1ccx Potential | An ML potential fitted to high-level CCSD(T)*/CBS reference data; a subset of the broader ANI ecosystem. | Used for highly accurate thermochemical calculations, such as reaction energies [35]. |

| CG-BS Optimizer | Conjugate Gradient with Backtracking Line Search, a geometry optimization algorithm. | Specially designed to work efficiently with the ANI potential, improving convergence on its potential energy surface [34]. |

| ANI-1/ANI-1x/ANI-2x Datasets | Large, curated datasets of organic molecular conformations and their quantum mechanical energies. | Used for training, validating, and benchmarking ML potentials like ANI-2x [37]. |

| Uncertainty Quantification (Std. Dev.) | The standard deviation of predictions from the 8-network ensemble in ANI-2x. | Critical for estimating the reliability of a given prediction; high values signal extrapolation [35]. |

| C15H13FN4O3 | C15H13FN4O3, MF:C15H13FN4O3, MW:316.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| C21H21BrN6O | C21H21BrN6O, MF:C21H21BrN6O, MW:453.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |