Electron-Hole Separation in Photocatalysis: Mechanisms, Strategies, and Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the fundamental principles and advanced strategies for managing electron-hole pair separation in semiconductor photocatalysis.

Electron-Hole Separation in Photocatalysis: Mechanisms, Strategies, and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the fundamental principles and advanced strategies for managing electron-hole pair separation in semiconductor photocatalysis. Tailored for researchers and scientists in drug development and biomedical fields, it explores the critical role of charge carrier dynamics in photocatalytic efficiency. The content spans from foundational physics to cutting-edge optimization techniques, including heterojunction design, defect engineering, and cocatalyst integration. By synthesizing recent scientific breakthroughs, this review serves as a strategic guide for leveraging photocatalysis in biomedical applications such as targeted drug delivery, pollutant degradation, and antimicrobial treatments, addressing both current capabilities and future research directions.

The Physics of Electron-Hole Pairs: Fundamental Charge Carrier Dynamics in Photocatalysis

Photocatalysis is the acceleration of a photoreaction in the presence of a catalyst, where the catalyst's excited state repeatedly interacts with reaction partners to form intermediates and regenerates itself after each cycle [1]. While applicable in homogeneous systems, heterogeneous photocatalysis using semiconductors is the most prominent field, with foundational work dating back to the discovery of electrochemical photolysis of water on a titanium dioxide (TiOâ‚‚) electrode by Fujishima and Honda in 1972 [1]. This process harnesses solar energy to drive chemical reactions, offering solutions for clean energy production (e.g., hydrogen generation via water splitting) and environmental remediation (e.g., pollutant degradation) [2] [3].

The heart of this system is the photoactive semiconductor, which governs light absorption, photo-carrier transfer, and surface catalytic reactions [3]. The efficiency of converting solar energy into chemical fuels hinges on the intricate balance between the generation, separation, and recombination of photogenerated charge carriers, and their subsequent utilization in surface redox reactions [4] [5]. This guide provides an in-depth technical overview of the core processes in semiconductor photocatalysis, with a particular emphasis on the critical challenge of electron-hole pair separation.

Fundamental Principles and Key Processes

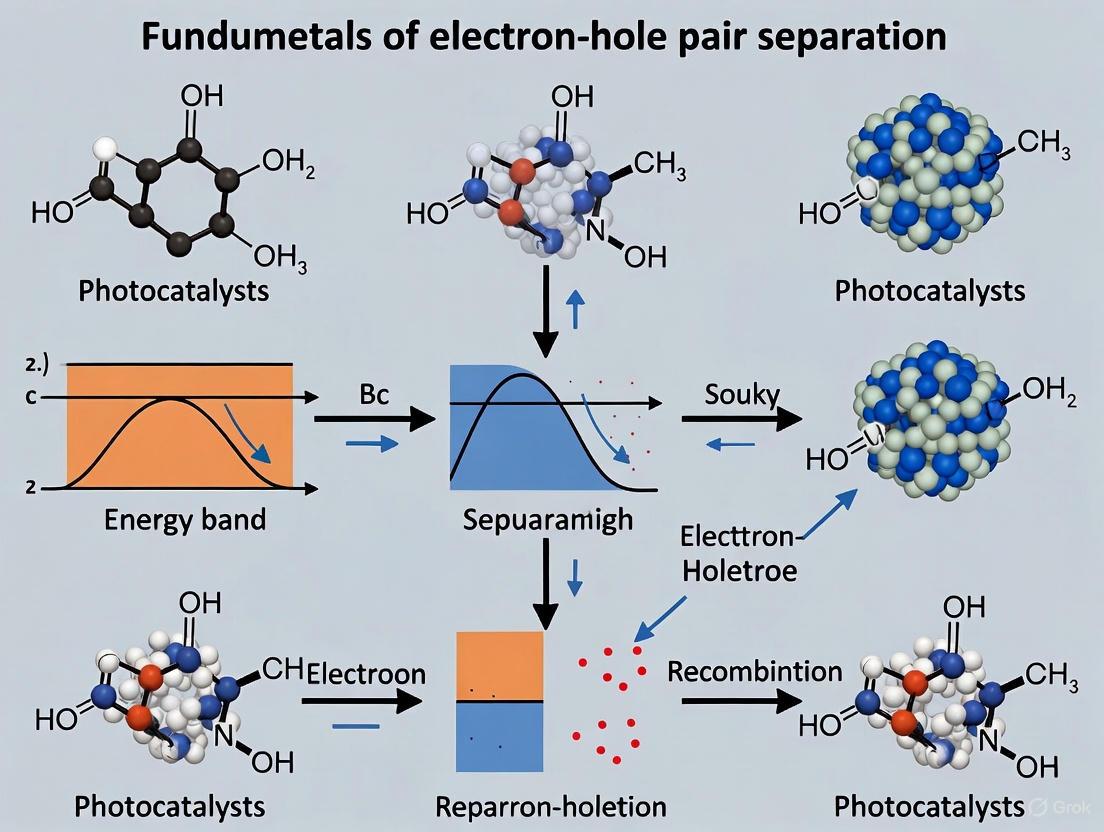

The photocatalytic process on a semiconductor can be conceptually divided into three fundamental, sequential stages, as illustrated in the diagram below.

Light Absorption and Charge Carrier Generation

The initial step involves the absorption of photons with energy (hν) equal to or greater than the semiconductor's bandgap energy (E_g) [4] [5]. This excitation promotes electrons from the filled valence band (VB) to the empty conduction band (CB), generating negatively charged electrons (eâ») in the CB and positively charged holes (hâº) in the VB [1]. This quasi-particle, an electron-hole pair, is also known as an exciton [1]. The bandgap energy is a critical material property that determines the range of the light spectrum a photocatalyst can utilize. For instance, anatase TiOâ‚‚, a widely studied photocatalyst, has a bandgap of 3.2 eV, limiting its absorption to ultraviolet light [4].

Charge Separation and Migration

Following generation, the photogenerated electrons and holes must separate and migrate to the surface of the semiconductor particle without recombining [5]. This step is arguably the most crucial for determining overall photocatalytic efficiency. The Coulombic attraction between the negatively charged electron and the positively charged hole drives recombination, which can occur in the bulk of the material or on its surface, dissipating the absorbed energy as heat or light [3] [5]. The timescales for these processes vary significantly, with charge generation occurring in femtoseconds, while productive charge transfer and surface reactions take place over microseconds to milliseconds [2]. Strategies to improve charge separation include reducing particle size to shorten migration paths, engineering defects, and creating heterojunctions [5].

Surface Redox Reactions

The final stage involves surface redox reactions of the migrated charge carriers. Thermodynamically, for a reaction to proceed, the energy level of the CB must be more negative than the reduction potential of the target species, while the VB level must be more positive than the oxidation potential [5]. For example, in photocatalytic hydrogen evolution, electrons in the CB reduce protons (Hâº) to molecular hydrogen (Hâ‚‚) [2]. Simultaneously, holes in the VB can oxidize water or other sacrificial agents (e.g., alcohols, triethanolamine), which are often added to consume holes and thereby suppress electron-hole recombination [2].

Table 1: Key Photocatalytic Processes and Their Timescales

| Process | Typical Timescale | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Light Absorption & Charge Generation | Femtoseconds (fs) | Immediate electron excitation from VB to CB upon photon absorption [2]. |

| Charge Trapping | Picoseconds to Nanoseconds (ps-ns) | Electrons and holes are trapped at surface or defect sites, influencing recombination rates [3]. |

| Charge Recombination | Nanoseconds to Microseconds (ns-μs) | Rapid recombination of bulk carriers; trapped carriers recombine more slowly [4] [3]. |

| Charge Transfer to Reactants | Microseconds to Milliseconds (μs-ms) | Successful migration of separated charges to surface sites for redox reactions [2] [3]. |

| Surface Catalytic Reaction | Milliseconds to Seconds (ms-s) | The relatively slow step where adsorbed species are reduced or oxidized by the charge carriers [3]. |

The Critical Role of Electron-Hole Separation

A central challenge in photocatalysis is that the timescale for charge carrier recombination is often much faster than that for charge transfer to surface-adsorbed species [3]. This results in most photogenerated charge carriers recombining instead of participating in useful chemistry, leading to low quantum efficiencies [4]. Therefore, the rational design of photocatalysts focuses heavily on strategies to enhance electron-hole separation.

Defect Engineering

Defects, such as oxygen vacancies and cation substitutions, play a complex dual role. They can act as recombination centers that promote energy loss, but when controlled rationally, they can also serve as active sites and facilitate charge separation [6]. Defect engineering involves creating specific vacancies or dopants that can trap one type of charge carrier (e.g., an electron), allowing its counterpart (e.g., a hole) to migrate away, thereby reducing the probability of recombination [6] [3]. The interactions via defect-strain coupling and defect-defect interactions can create conductive pathways that enhance separation [6].

Advanced Material Strategies for Enhanced Separation

Several material design strategies have been developed to create internal electric fields and pathways that drive electron-hole separation.

Table 2: Common Strategies for Enhancing Electron-Hole Separation

| Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Example Materials |

|---|---|---|

| Heterojunction Construction | Creates an internal electric field at the interface between two semiconductors to drive charge separation [7]. | ZnO/TiOâ‚‚ (Type-II), CdO/TiOâ‚‚ (Z-Scheme) [7]. |

| Schottky Barrier Formation | Using noble metal nanoparticles (e.g., Ag, Pt) as electron sinks. The metal-semiconductor interface forms a Schottky barrier that traps electrons, inhibiting recombination [7]. | Ag/TiOâ‚‚ [7]. |

| Plasmonic Enhancement | Plasmonic metal nanostructures (e.g., Au, Ag) under resonant light excitation generate "hot carriers" that can be injected into the semiconductor, enhancing local electric fields and charge separation [3]. | Au/TiOâ‚‚, Ag/TiOâ‚‚ [3]. |

| Co-catalyst Loading | Acts as a reactive site that lowers the activation energy for surface reactions and facilitates charge transfer from the semiconductor, thereby improving separation [2]. | Pt, MoSâ‚‚, single-atom catalysts, carbon materials [2]. |

Experimental Methodologies and Characterization

Advancing the field of photocatalysis requires robust experimental methods for synthesizing materials and, crucially, for characterizing the dynamics of charge carriers.

Synthesis of Photocatalytic Materials

The sol-gel process is a common wet-chemical method for fabricating semiconductor nanoparticles, including doped variants. The process typically involves dissolving a metal alkoxide precursor (e.g., titanium isopropoxide for TiOâ‚‚) and dopant precursors (e.g., silver nitrate for Ag, zinc acetate for ZnO) in a solvent [7]. Hydrolysis and condensation reactions form a colloidal suspension (sol), which evolves into a gel-like network. Subsequent drying and calcination steps yield the final crystalline, doped metal oxide nanoparticles [7].

Characterization of Charge Carrier Dynamics

Understanding the fate of photogenerated charge carriers requires techniques that can probe events across a vast range of timescales and spatial resolutions.

Table 3: Techniques for Characterizing Charge Transfer Dynamics

| Technique | Abbreviation | Key Measured Parameter(s) | Application in Photocatalysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time-Resolved Photoluminescence | TRPL | Photoluminescence lifetime | Probes the recombination kinetics of electron-hole pairs; a longer lifetime suggests better charge separation [3]. |

| Transient Absorption Spectroscopy | TAS | Carrier relaxation kinetics | Tracks the appearance and decay of photogenerated electrons and holes directly, providing insights into trapping and recombination processes [3]. |

| Intensity-Modulated Photocurrent/Voltage Spectroscopy | IMPS/IMVS | Charge transfer time constant, recombination time constant | Used in photoelectrochemical systems to deconvolute the timescales for charge transfer to the electrolyte versus recombination [3]. |

| Photoelectrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy | PEIS | Charge transfer resistance | Assesses the resistance to charge transfer at the semiconductor-electrolyte interface [3]. |

| Kelvin Probe Force Microscopy | KPFM | Surface potential, work function | Maps surface photovoltage with high spatial resolution, visualizing local charge separation and accumulation [3]. |

The following workflow outlines a typical process for developing and evaluating a new photocatalyst, from synthesis to performance testing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

This section details key materials and reagents commonly employed in photocatalytic research for hydrogen evolution, based on the search results.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Photocatalysis

| Item | Function / Role | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Semiconductor Precursors | Source of the primary photocatalyst material. | Titanium(IV) isopropoxide (for TiOâ‚‚) [7]. |

| Dopant Precursors | Introduce elements to modify band structure and suppress recombination. | Silver nitrate (Ag⺠source), Zinc acetate dihydrate (Zn²⺠source), Cadmium acetate dihydrate (Cd²⺠source) [7]. |

| Sacrificial Hole Scavengers | Irreversibly consume photogenerated holes to suppress electron-hole recombination. | Methanol, Ethanol, Triethanolamine, Sodium sulfide (Na₂S)/Sodium sulfite (Na₂SO₃ mixture) [2] [7]. |

| Co-catalysts | Provide active sites for surface reactions, facilitate charge separation. | Platinum (Pt), Gold (Au), Molybdenum sulfide (MoSâ‚‚), Metal phosphides (Niâ‚‚P), Single-atom catalysts (Ni, Co) [2]. |

| Solvents & Chemical Additives | Used in synthesis and reaction medium preparation. | Ethanol, Acetic acid, Polyvinyl pyrrolidone (PVP - capping agent) [7]. |

| 3,3-Dipropylpiperidine | 3,3-Dipropylpiperidine | High-purity 3,3-Dipropylpiperidine for pharmaceutical research. CAS 1343317-81-6. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| DBCO-PEG4-Val-Ala-PAB-PNP | DBCO-PEG4-Val-Ala-PAB-PNP, MF:C52H60N6O14, MW:993.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The journey of a photocatalyst from light absorption to surface reactions is a complex interplay of competing physical and chemical processes. While the fundamental principles of charge generation and redox reactions are well-established, the central challenge of efficient electron-hole separation remains a vibrant area of research. The continued development and application of advanced in-situ and time-resolved characterization techniques are critical for uncovering the intricate charge transfer dynamics at play. Future progress hinges on the rational design of photocatalytic materials—through defect engineering, heterostructuring, and cocatalyst integration—to master control over the fate of charge carriers. Success in this endeavor will pave the way for highly efficient solar energy conversion systems, contributing significantly to a sustainable energy future.

In the field of photocatalysis, the efficient conversion of solar energy into chemical energy, such as in hydrogen production through water splitting, is governed by the fundamental principles of semiconductor band theory. The photocatalytic process begins when a semiconductor absorbs photons with energy equal to or greater than its band gap, promoting electrons from the filled valence band to the empty conduction band. This transition creates negatively charged electrons (eâ») in the conduction band and positively charged holes (hâº) in the valence band, collectively known as electron-hole pairs [8] [9]. These photogenerated charge carriers are then responsible for driving the redox reactions essential for processes like hydrogen evolution [8].

The separation and migration efficiency of these electron-hole pairs are critical determinants of overall photocatalytic performance. Unfortunately, in most semiconductor materials, the rapid recombination of these charge carriers—occurring within nanoseconds—severely limits practical application efficiencies [8] [9]. A comprehensive understanding of the conduction band, valence band, and band gap is therefore not merely academic but fundamental to designing and engineering advanced photocatalytic materials with enhanced charge separation capabilities and improved solar energy conversion efficiencies [9].

Core Concepts and Definitions

The Valence Band (VB)

The valence band represents the highest range of electron energies where electrons are present at absolute zero temperature, and these electrons are bound to atoms within the crystal lattice [10]. In a semiconductor, the valence band is fully occupied by electrons. When an electron from this band is excited and jumps to the conduction band, it leaves behind a vacancy [11]. This vacancy, termed a hole, is not a physical particle but rather a quasiparticle—a conceptual tool that simplifies the description of the collective behavior of the remaining electrons in the nearly-full band [11]. From a practical perspective, this hole behaves as if it were a positively charged particle, and its movement through the crystal lattice constitutes an electric current [10] [11].

The Conduction Band (CB)

The conduction band is the lowest energy range of unoccupied electronic states where electrons can move freely throughout the crystal lattice, thereby conducting electricity [10]. When an electron in the valence band absorbs a photon with sufficient energy, it can overcome the energy barrier and be excited into the conduction band. Within the conduction band, these photogenerated electrons act as negative charge carriers. Their ability to move and participate in chemical reactions is crucial for reduction processes in photocatalysis, such as the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) where water is reduced to hydrogen gas [8].

The Band Gap

The band gap, also known as the energy gap, is the energy difference between the top of the valence band and the bottom of the conduction band [9]. It represents the minimum energy required to excite an electron from the valence band to the conduction band, thereby creating an electron-hole pair. The size of the band gap fundamentally determines a material's electrical conductivity and optical absorption properties.

- Insulators: Feature a large band gap (typically >5 eV), preventing significant electron excitation under normal conditions.

- Semiconductors: Possess an intermediate band gap (e.g., 1-3 eV), allowing for controllable electron excitation with external energy inputs like heat or light.

- Conductors: Have effectively no band gap, with the valence and conduction bands overlapping.

In photocatalysis, the band gap must be narrow enough to absorb visible light (which constitutes a major portion of the solar spectrum) yet wide enough to provide sufficient energy to drive the desired chemical reactions, such as water splitting which thermodynamically requires a minimum of 1.23 eV [12].

Table 1: Band Gap Properties of Selected Photocatalytic Materials

| Material | Band Gap (eV) | Light Absorption Range | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anatase TiOâ‚‚ | ~3.2 [13] | Ultraviolet | Wide bandgap; limited to UV light [14] |

| g-C₃N₄ | ~2.7 [8] | Visible Light | Metal-free polymer; suitable bandgap but high charge recombination [8] |

| Co-doped TiOâ‚‚ (N, Ta) | ~2.71 [13] | Visible Light (up to ~457 nm) | Bandgap engineered via passivated co-doping [13] |

| MNb₂O₆ family | ~2.0 - 3.0 [14] | Visible Light | Tunable band structures; promising for visible-light activity [14] |

Electron-Hole Pairs and Their Dynamics

The absorption of light with energy greater than the band gap results in the formation of an electron-hole pair. The electron is a physical particle with negative charge and negative effective mass, while the hole is a quasiparticle with positive charge and positive effective mass [11]. This distinction in their effective masses leads to a critical difference in their mobility—a measure of how quickly a charge carrier can move through a material when pulled by an electric field.

Generally, electron mobility is significantly higher than hole mobility because electrons in the conduction band are more delocalized and move freely, whereas hole movement relies on the sequential hopping of valence band electrons between atoms [10] [11]. This mobility disparity is a key consideration in semiconductor device design, including photocatalytic systems, where efficient charge separation is paramount.

Once generated, electron-hole pairs can follow several pathways, as illustrated in the diagram below. The competition between productive charge separation and undesired recombination dictates the quantum efficiency of the photocatalytic process.

Charge Carrier Dynamics: Pathway of photogenerated electron-hole pairs from excitation to recombination or productive redox reactions.

Band Engineering for Enhanced Charge Separation

A primary challenge in photocatalysis is the rapid, nanosecond-scale recombination of photogenerated electrons and holes, which drastically reduces the number of charge carriers available for surface chemical reactions [8] [9]. Band engineering encompasses a suite of strategies designed to modify the electronic band structure of semiconductors to suppress this recombination and enhance charge separation efficiency.

Doping and Co-doping

Introducing specific impurity atoms (dopants) into a semiconductor lattice can create intermediate energy levels within the band gap, effectively reducing the apparent band gap and extending light absorption into the visible region [13]. For instance, passivated co-doping—simultaneously incorporating both donor (e.g., Ta) and acceptor (e.g., N) elements—in TiO₂ has been predicted to significantly raise the valence band maximum and modestly raise the conduction band minimum. This results in a narrowed band gap of about 2.72 eV, shifting the absorption edge to 457.6 nm and thereby enhancing visible light activity [13].

Heterojunction Engineering

Coupling two or more semiconductors with different band structures can create a built-in potential at their interface that drives the spatial separation of electrons and holes. In a typical type-II heterojunction, photogenerated electrons tend to migrate to the semiconductor with the lower-lying conduction band, while holes move to the one with the higher-lying valence band. This physical separation of charge carriers across different materials significantly reduces the probability of recombination [14].

Dual-Channels Charge Separation

A particularly advanced strategy involves creating dual-channels for charge separation, which combines volume-phase and surface-phase separation mechanisms [8]. For example, in a composite material consisting of sulfur-doped hollow tubular g-C₃Nâ‚„ (S-HTCN) decorated with carbon dots (CDs), the S-atom doping modifies the electronic structure to enhance charge separation within the bulk material (volume phase), while the CDs facilitate the extraction and utilization of electrons at the surface (surface separation) [8]. This synergistic approach has been reported to achieve exceptional hydrogen production rates as high as 9284 μmol hâ»Â¹ gâ»Â¹ [8].

Table 2: Band Engineering Strategies for Improved Charge Separation

| Strategy | Mechanism | Exemplary Material | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Co-doping | Modifies band edges; introduces intra-gap states [13] | (N, Ta)-codoped TiOâ‚‚ [13] | Band gap narrowed to 2.71 eV; visible light absorption [13] |

| Heterostructure Design | Creates internal electric fields for charge separation [14] | g-C₃Nâ‚„/TiOâ‚‚, MNbâ‚‚O₆ composites [14] | Enhanced charge separation; Hâ‚‚ rates up to 146 mmol hâ»Â¹ gâ»Â¹ [14] |

| Dual-Channels Separation | Combines volume-phase and surface-phase separation [8] | CDs/S-HTCN [8] | High Hâ‚‚ production rate (9284 μmol hâ»Â¹ gâ»Â¹) [8] |

| Crystallinity & Defect Control | Reduces bulk recombination centers [8] | High-crystallinity g-C₃N₄ [8] | Improved charge transport and lifetime [8] |

Experimental Protocols for Band Structure and Charge Separation Analysis

Synthesis of Engineered Photocatalysts

Protocol 1: Hydrothermal Synthesis of Hollow Tubular g-C₃N₄ (HTCN) [8]

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve 8 g of urea and 5 g of melamine in 80 mL of deionized water. Stir the mixture for 3 hours to ensure homogeneity.

- Hydrothermal Reaction: Transfer the solution into a 100 mL Teflon-lined autoclave. Maintain the autoclave at 180°C for 20 hours to form the precursor.

- Washing and Drying: Collect the resulting precursor via centrifugation and wash it thoroughly with deionized water and ethanol to remove impurities. Dry the washed precursor in an oven.

- Thermal Polycondensation: Place the dried precursor in a muffle furnace and calcine at 550°C for 4 hours with a controlled heating ramp of 5°C per minute. This step converts the precursor into the final hollow tubular g-C₃N₄ structure.

Protocol 2: Preparation of Sulfur-Doped and Carbon Dot-Modified Composite (CDs/S-HTCN) [8]

- Sulfur Doping: Mix the as-prepared HTCN powder with trithiocyanuric acid (a sulfur source) in an agate mortar.

- Secondary Calcination: Heat the mixture to 500°C for 2 hours under a nitrogen atmosphere. During this process, the decomposition of trithiocyanuric acid releases H₂S and CS₂ gases, which facilitate sulfur doping into the HTCN framework, resulting in S-HTCN.

- Carbon Dot Modification: Disperse the S-HTCN powder in an aqueous solution containing pre-synthesized carbon dots. Subject the suspension to ultrasonic treatment for 1 hour to ensure uniform adsorption of the carbon dots onto the surface of the S-HTCN tubes.

Characterization Techniques and Methodologies

UV-Vis Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy (DRS)

- Purpose: To determine the optical absorption profile and band gap energy of the semiconductor.

- Procedure: Measure the diffuse reflectance of the powdered photocatalyst and convert the data to absorbance using the Kubelka-Munk function. The band gap energy (E₉) can be estimated by plotting (αhν)⿠versus photon energy (hν), where α is the absorption coefficient, and n depends on the nature of the optical transition (n=1/2 for direct band gaps, n=2 for indirect band gaps). The extrapolation of the linear region of the plot to the x-axis gives the band gap value [13] [14].

Transient Photovoltage (TPV) Technique

- Purpose: To directly probe the dynamics and lifetime of photogenerated charge carriers.

- Procedure: Excite the photocatalyst sample with a short-pulse laser and monitor the resulting transient photovoltage signal over time. The decay profile of this signal provides critical information about the charge separation efficiency and recombination kinetics. A longer decay lifetime indicates more effective suppression of electron-hole recombination, which is a key goal of band engineering [8].

Electrochemical and Photoelectrochemical Measurements

- Purpose: To assess charge carrier mobility, separation efficiency, and interfacial charge transfer capabilities.

- Procedures:

- Photocurrent Response: Measure the current generated under periodic light illumination. A higher and more stable photocurrent suggests better separation and transport of photoinduced charge carriers.

- Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): Analyze the semicircle in the Nyquist plot. A smaller arc radius typically indicates a lower charge transfer resistance and more efficient charge separation at the semiconductor-electrolyte interface [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Photocatalyst Development

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Exemplary Application |

|---|---|---|

| Urea | Low-cost precursor for thermal synthesis of graphitic carbon nitride (g-C₃N₄) [8]. | Serves as a primary feedstock for creating hollow tubular g-C₃N₄ structures [8]. |

| Melamine | Alternative nitrogen-rich precursor for g-C₃N₄ synthesis [8]. | Used in combination with urea to control morphology and properties of g-C₃N₄ [8]. |

| Trithiocyanuric Acid | Source of sulfur atoms for dopant incorporation into semiconductor lattices [8]. | Provides S-dopants for modifying the electronic structure of g-C₃N₄, enhancing its visible-light activity [8]. |

| Carbon Dots (CDs) | Nano-sized carbon-based co-catalysts that enhance electron capture and surface reactions [8]. | Decorated onto S-HTCN to create a dual-channel charge separation pathway, boosting Hâ‚‚ evolution [8]. |

| Niobate Salts | Precursors for synthesizing MNb₂O₆ family photocatalysts [14]. | Used in hydrothermal/solvothermal synthesis to produce visible-light-active niobate semiconductors [14]. |

| Dopant Precursors (e.g., N, Ta sources) | Introduce foreign atoms into a host semiconductor to engineer its band structure [13]. | Enable passivated co-doping of TiOâ‚‚ to narrow its band gap and improve visible light absorption [13]. |

| Methyltetrazine-PEG8-DBCO | Methyltetrazine-PEG8-DBCO, MF:C44H54N6O10, MW:826.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2,2-dichloroPropanamide | 2,2-dichloroPropanamide, MF:C3H5Cl2NO, MW:141.98 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

A deep understanding of the conduction band, valence band, and band gap is indispensable for advancing photocatalytic research, particularly for electron-hole pair separation. The band gap not only dictates the light absorption capability of a semiconductor but also the thermodynamic potential of its photogenerated charge carriers. The strategic engineering of these band structure components—through doping, heterojunction formation, and multi-channel separation strategies—provides a powerful toolkit for mitigating the pervasive challenge of charge carrier recombination. As characterization techniques like transient photovoltage continue to illuminate the complex dynamics of photoinduced charges, the rational design of high-performance photocatalysts becomes increasingly attainable. The continued refinement of these band theory principles is pivotal for developing the next generation of photocatalytic materials capable of efficient solar-driven hydrogen production and other renewable energy applications.

In photocatalytic systems, from environmental remediation to solar fuel generation, the efficient separation of photogenerated electron-hole pairs is a fundamental determinant of overall performance [4]. Upon light absorption, semiconductors generate these charge carriers, which can either recombine—dissipating their energy as heat or light—or migrate to the surface to drive crucial redox reactions [4] [15]. Electron-hole recombination is the critical competing process that severely limits the quantum efficiency of photocatalysts by reducing the number of available charge carriers for surface reactions [4] [16]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of recombination pathways, their kinetics, and advanced experimental methodologies for their characterization, framed within the essential context of optimizing charge separation for photocatalytic applications.

Fundamental Recombination Mechanisms

Photogenerated charge carriers in semiconductors can recombine through several distinct pathways, each with characteristic kinetics and energy dissipation mechanisms. Understanding these pathways is prerequisite to designing strategies to suppress them.

Radiative Recombination (Band-to-Band): This process involves the direct recombination of a conduction band electron with a valence band hole, resulting in the emission of a photon with energy approximately equal to the bandgap of the semiconductor [17] [18]. It is the dominant mechanism in direct bandgap semiconductors and is the principle behind light-emitting diodes (LEDs) [18]. The recombination rate, ( Rr ), is proportional to the product of electron and hole concentrations (( Rr = Br n p )), where ( Br ) is the radiative recombination coefficient [18].

Shockley-Read-Hall (SRH) Trap-Assisted Recombination: Defects, impurities, or surface states within the bandgap act as trapping centers, facilitating the stepwise recombination of electron-hole pairs [17] [18]. This non-radiative process dissipates energy primarily as heat (phonons) and is a major loss channel in imperfect crystals or materials with high surface-to-volume ratios [17]. The recombination rate through a single trap level depends on the density of traps and their capture cross-sections for electrons and holes.

Auger Recombination: A three-body process wherein an electron and a hole recombine, but instead of emitting a photon, the excess energy is transferred to a third charge carrier (either an electron or a hole), which is excited to a higher energy state [19] [18]. This carrier subsequently relaxes back to its ground state, releasing thermal energy. Auger recombination becomes particularly significant at high charge carrier densities [19].

Surface Recombination: Surfaces are inherently rich in dangling bonds and defects, creating a high density of trap states that promote SRH recombination [18]. This is a severe issue for nanomaterials and photocatalysts with high surface area, where a significant fraction of charge carriers are generated near the surface.

The following diagram illustrates the primary recombination pathways within a semiconductor material.

Table 1: Characteristics of Primary Recombination Mechanisms

| Mechanism | Energy Dissipation | Key Influencing Factors | Typical Time Scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radiative | Photon emission | Direct bandgap, high crystal quality | Nanoseconds to microseconds |

| SRH (Trap-Assisted) | Heat (phonons) | Defect density, impurity concentration | Picoseconds to nanoseconds |

| Auger | Heat (phonons) | Very high carrier density ((n^3) dependence) | Picoseconds to nanoseconds |

| Surface Recombination | Heat (phonons) | Surface state density, passivation | Picoseconds to nanoseconds |

Quantitative Kinetics and Key Parameters

The overall recombination dynamics are quantitatively described by the ABC model, which sums the contributions from the dominant pathways [19]. The total recombination rate, ( R ), is given by: [ R = An + Bn^2 + Cn^3 ] where ( n ) is the carrier concentration, and the coefficients ( A ), ( B ), and ( C ) represent the rates for SRH (linear in ( n )), radiative (bimolecular, ( n^2 )), and Auger (three-body, ( n^3 )) recombination, respectively [19].

The competition between recombination and the desired charge separation for surface reactions dictates the quantum efficiency (( \eta )) of a photocatalytic process. The internal quantum efficiency (IQE) for a system like a solar cell is the ratio of charge carriers collected to the number of absorbed photons, which is directly hampered by recombination losses [20]. The carrier lifetime (( \tau )) is a critical parameter that encapsulates the effect of all recombination pathways, defined as the average time a photogenerated carrier exists before recombination [18]: [ \frac{1}{\tau} = \frac{1}{\tau{r}} + \frac{1}{\tau{nr}} ] where ( \taur ) and ( \taunr ) are the radiative and non-radiative lifetimes, respectively [18]. The internal quantum efficiency can then be expressed as: [ \eta = \frac{1/\taur}{1/\taur + 1/\tau_nr} ] This relationship highlights that to achieve high quantum efficiency, the radiative lifetime must be significantly shorter than the non-radiative lifetime [18].

Table 2: Key Quantitative Parameters in Recombination Kinetics

| Parameter | Symbol | Description | Impact on Photocatalysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carrier Lifetime | ( \tau ) | Average time before carrier recombination | Longer lifetime increases probability of surface reaction. |

| Radiative Coefficient | ( B_r ) | Constant for bimolecular radiative recombination | High in direct bandgap materials (e.g., GaAs). |

| Auger Coefficient | ( C ) | Constant for three-body Auger recombination | Dominates at high illumination intensities. |

| Trap Density | ( N_t ) | Concentration of defect states in the bandgap | Directly proportional to SRH recombination rate. |

| Internal Quantum Efficiency | IQE | # of collected carriers / # of absorbed photons | Fundamental measure of charge separation success. |

Advanced Experimental Methodologies

A comprehensive understanding of recombination dynamics requires characterization across vast temporal scales, from the initial photoexcitation event to the final charge utilization. The following workflow outlines a multi-technique experimental approach to probe these processes.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (TRPL) for Carrier Lifetime Measurement

- Objective: To directly measure the radiative recombination lifetime of charge carriers.

- Methodology:

- Excitation: A pulsed laser source (e.g., a Ti:Sapphire laser producing ~100 fs pulses) is tuned to an energy above the bandgap of the photocatalyst and focused onto the sample.

- Detection: The resulting photoluminescence (PL) is collected and directed into a fast detector. For nanosecond resolutions, time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) with a microchannel plate photomultiplier tube (MCP-PMT) is standard. For faster, picosecond resolutions, a streak camera system is employed [21].

- Analysis: The decay curve of PL intensity versus time is fitted to a exponential decay model (single or multi-exponential) to extract the carrier lifetime (( \tau )). A shorter lifetime indicates more efficient recombination, either radiatively or via trapping.

Protocol 2: Femtosecond Transient Absorption Spectroscopy (fs-TAS)

- Objective: To track the ultrafast dynamics of photogenerated electrons and holes, including trapping and non-radiative recombination [21].

- Methodology:

- Pump-Probe Setup: A high-power pump pulse excites the sample, generating charge carriers. A time-delayed, broadband white light probe pulse then interrogates the sample.

- Spectral Monitoring: The differential absorption (( \Delta A )) of the probe pulse is measured as a function of wavelength and pump-probe time delay. This provides a spectral fingerprint of excited states (electrons in the CB, trapped electrons, holes in the VB) [21] [22].

- Kinetic Analysis: The decay of specific transient absorption features is tracked over time, revealing kinetics for processes such as electron trapping (often in the ps regime) and electron-hole recombination (ps to ns) [4] [22].

Protocol 3: In-situ Photoelectrochemical (PEC) and Surface Analysis

- Objective: To correlate recombination losses with interfacial charge transfer efficiency and surface chemistry under operational conditions [21].

- Methodology:

- Device Fabrication: The photocatalyst is fabricated into a photoelectrode (e.g., as a thin film on a conductive substrate).

- PEC Characterization: Transient photocurrent measurements are performed. A slow photocurrent rise indicates competition from bulk or surface recombination before charges can be collected at the interface [21].

- Surface Interrogation: Simultaneously or subsequently, techniques like in-situ X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) monitor chemical states and band bending at the surface, while Kelvin probe force microscopy (KPFM) maps surface potential variations related to charge accumulation and recombination hotspots [21].

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Recombination Studies

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Ti:Sapphire Femtosecond Laser | Provides ultrafast pump pulses for TRPL and TAS to initiate and probe carrier dynamics on their native timescales. |

| Streak Camera / TCSPC Module | Essential detector for TRPL, enabling high-time-resolution measurement of photoluminescence decay. |

| Broadband Probe Source | Generates white light continuum for TAS to monitor a wide spectral range of excited-state absorptions. |

| Electrochemical Workstation | Applies potential and measures photocurrent in PEC cells to quantify charge separation and collection efficiency. |

| Hole Scavengers (e.g., Sulfide) | In photocatalytic suspensions, sacrificially consumes holes, suppressing recombination by isolating electron kinetics [16]. |

The profound impact of electron-hole recombination on the efficiency of photocatalytic systems necessitates a deep and quantitative understanding of its pathways. By combining fundamental kinetic models like the ABC formalism with advanced, time-resolved spectroscopic and photoelectrochemical techniques, researchers can pinpoint the dominant loss mechanisms in a material. This knowledge is the cornerstone for rational design of advanced photocatalysts, guiding strategies such as defect passivation, heterojunction engineering, and surface cocatalyst modification to steer photogenerated charges toward productive reactions and away from recombination. Overcoming the critical challenge of recombination is essential for realizing the full potential of photocatalysis in sustainable energy and environmental applications.

The efficacy of photocatalytic technology is fundamentally governed by the thermodynamic landscape of the materials involved. At the heart of processes such as photocatalytic water splitting and environmental pollutant degradation lies the successful generation, separation, and utilization of electron-hole pairs. The thermodynamic driving force for these surface redox reactions is intrinsically determined by the energy band structure of the photocatalyst relative to the redox potentials of the target reactions. This technical guide delineates the critical thermodynamic requirements—specifically, the redox potential relationships—for these two pivotal applications, framing them within the broader scientific challenge of managing electron-hole pair separation to enhance photocatalytic efficiency.

Fundamental Principles and Thermodynamic Prerequisites

A photocatalyst initiates redox reactions upon absorbing photons with energy equal to or greater than its band gap, exciting electrons from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB) and creating holes in the VB [23] [24]. The resulting electron-hole pairs must then separate, migrate to the catalyst surface, and engage in chemical reactions with adsorbed species. The thermodynamic feasibility of these reactions is contingent upon the energy levels of the photocatalyst's bands [24].

Table 1: Standard Redox Potentials of Key Reactions Relevant to Water Splitting and Pollutant Degradation (vs. NHE at pH 0)

| Reaction | Equation | Standard Potential (V) |

|---|---|---|

| Water Oxidation | ( 2H2O + 4h^+ \rightarrow O2 + 4H^+ ) | +1.23 |

| Water Reduction | ( 2H^+ + 2e^- \rightarrow H_2 ) | 0.00 |

| Hydroxyl Radical Formation | ( H_2O + h^+ \rightarrow ^\bullet OH + H^+ ) | +2.27 |

| Superoxide Radical Formation | ( O2 + e^- \rightarrow O2^{\bullet -} ) | -0.33 |

For a photocatalytic reaction to proceed spontaneously, the CB potential must be more negative than the reduction potential of the target species, providing the driving force for electron transfer. Conversely, the VB potential must be more positive than the oxidation potential of the target species to enable hole transfer [24]. This fundamental thermodynamic requirement is the primary filter for selecting potential photocatalysts for a given application.

Thermodynamic Requirements for Water Splitting

Overall water splitting is a thermodynamically uphill reaction, requiring a minimum Gibbs free energy of 237 kJ/mol, which corresponds to a photon energy of 1.23 eV per electron transferred [23]. The two half-reactions are:

- Hydrogen Evolution Reaction (HER): ( 2H^+ + 2e^- \rightarrow H_2 ) ((E^o) = 0.00 V vs. NHE)

- Oxygen Evolution Reaction (OER): ( 2H2O + 4h^+ \rightarrow O2 + 4H^+ ) ((E^o) = +1.23 V vs. NHE)

To simultaneously drive both half-reactions, a photocatalyst must satisfy two key thermodynamic conditions:

- The minimum band gap energy must be ≥ 1.23 eV.

- The CB edge must be more negative than the Hâº/Hâ‚‚ redox potential (0 V vs. NHE).

- The VB edge must be more positive than the Oâ‚‚/Hâ‚‚O redox potential (+1.23 V vs. NHE) [23] [24].

Table 2: Band Edge Positions of Common Photocatalysts for Water Splitting

| Photocatalyst | Band Gap (eV) | CB Potential (V vs. NHE) | VB Potential (V vs. NHE) | Suitable for Overall Water Splitting? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiOâ‚‚ | ~3.2 | -0.5 | +2.7 | Yes, but large overpotential |

| SrTiO₃ | ~3.2 | -1.1 | +2.1 | Yes |

| BiVOâ‚„ | ~2.4 | +0.1 | +2.5 | No (CB too positive) |

| g-C₃N₄ | ~2.7 | -1.1 | +1.6 | No (VB too positive) |

| CdS | ~2.4 | -0.8 | +1.6 | No (VB too positive) |

As illustrated in Table 2, while TiO₂ and SrTiO₃ meet the thermodynamic criteria, their wide band gaps confine their light absorption to the ultraviolet region [23]. Narrower band gap materials like CdS and g-C₃N₄, though visible-light-active, possess VB or CB positions that are misaligned for overall water splitting, necessitating strategies like cocatalyst deposition or heterojunction construction to function effectively [24].

Figure 1: Schematic diagram illustrating the essential thermodynamic alignment of a photocatalyst's energy bands with the water splitting redox potentials.

Thermodynamic Requirements for Pollutant Degradation

Photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants operates on a different thermodynamic principle. The process is primarily driven by powerful oxidative radicals, notably the hydroxyl radical (•OH), which non-selectively mineralizes contaminants into CO₂ and H₂O [25]. The formation of these radicals dictates the thermodynamic requirements.

The primary oxidative species and their formation potentials are:

- Hydroxyl Radical (•OH): Considered the most potent oxidant, it can be formed via hole oxidation of H₂O or OH⻠((E^o) = +2.27 V vs. NHE for (H_2O + h^+ \rightarrow ^\bullet OH + H^+)) [24].

- Superoxide Anion Radical (O₂•â»): Formed by the reduction of dissolved oxygen by photogenerated electrons ((E^o) = -0.33 V vs. NHE for (O2 + e^- \rightarrow O2^{\bullet -})) [25] [24].

- Direct Hole Oxidation: The photogenerated hole itself must possess sufficient oxidative power to directly attack the pollutant molecule.

Consequently, for effective pollutant degradation, the VB potential must be more positive than the oxidation potential for •OH generation (+2.27 V vs. NHE) or the potential of the target pollutant itself [24]. The requirement for the CB is less stringent; it need only be more negative than the O₂/O₂•⻠potential (-0.33 V vs. NHE) to enable the reduction of oxygen, which suppresses electron-hole recombination and perpetuates the oxidative cycle.

Table 3: Suitability of Photocatalysts for Pollutant Degradation Based on Band Positions

| Photocatalyst | VB Potential (V vs. NHE) | Sufficient for •OH Generation? | Key Degradation Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| TiO₂ | +2.7 | Yes | Primary: •OH radical attack |

| g-C₃N₄ | +1.6 | No | Primary: Direct hole oxidation / O₂•⻠|

| ZnO | +2.9 | Yes | Primary: •OH radical attack |

| BiVO₄ | +2.5 | Yes (Marginal) | Mixed: •OH and direct hole oxidation |

This framework explains why TiO₂ is a dominant photocatalyst for environmental remediation, as its highly positive VB (+2.7 V) readily generates •OH radicals [25]. In contrast, the VB of g-C₃N₄ (+1.6 V) is insufficient to oxidize H₂O to •OH, limiting its degradation pathway to direct hole oxidation or other radicals, which can affect its efficiency and degradation pathway for certain pollutants [24].

Experimental Protocols for Determining Thermodynamic Viability

Validating the thermodynamic alignment of a photocatalyst requires a combination of electrochemical and spectroscopic techniques.

Protocol: Determining Flat-Band Potential and Band Edge Positions

The flat-band potential ((E_{fb})) of a semiconductor, which approximates the CB edge for n-type semiconductors, can be determined using Mott-Schottky analysis [21].

- Electrode Preparation: Fabricate a working electrode by depositing a thin film of the photocatalyst material (e.g., a slurry of TiOâ‚‚ nanoparticles) onto a conductive substrate like Fluorine-doped Tin Oxide (FTO) glass. Use a standard three-electrode electrochemical cell with the prepared electrode as the working electrode, a Pt wire as the counter electrode, and a reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl or SCE).

- Impedance Measurement: Perform electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements under dark conditions at a fixed frequency (e.g., 1 kHz) while sweeping the applied DC potential.

- Mott-Schottky Plot: Plot the data according to the Mott-Schottky equation: ( \frac{1}{C{sc}^2} = \frac{2}{\epsilon \epsilon0 q Nd}(E - E{fb} - \frac{kT}{q}) ), where (C{sc}) is the space charge layer capacitance, (E) is the applied potential, and (Nd) is the donor density.

- Data Analysis: The x-intercept of the linear region of the ( \frac{1}{C{sc}^2} ) vs. (E) plot gives the (E{fb}). Convert this value to the Normal Hydrogen Electrode (NHE) scale. For n-type semiconductors, (E{CB} \approx E{fb}). The VB potential can then be calculated using the relation: (E{VB} = E{CB} + Eg), where the band gap ((Eg)) is determined from UV-Vis diffuse reflectance spectra via a Tauc plot.

Protocol: Validating Water Splitting Activity

To experimentally confirm that a material meets the thermodynamic requirements for overall water splitting, a direct activity test is essential [23].

- Reaction Setup: Use a closed-gas-circulation reaction system, typically a top-irradiation quartz cell connected to a gas chromatography (GC) system for online analysis.

- Photocatalyst Preparation: Disperse the photocatalyst powder (e.g., 50-100 mg) in a pure water reactant solution (e.g., 100 mL) without any sacrificial agents. Sacrificial agents can mask the true thermodynamic capability by consuming only one type of charge carrier.

- Degassing: Evacuate the entire system to remove dissolved air and ensure an inert atmosphere.

- Irradiation: Irradiate the suspension with a simulated solar light source (e.g., a Xe lamp). Use appropriate cutoff filters to study UV or visible light activity separately.

- Product Analysis: Periodically sample the gas phase in the reaction system using the online GC equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD) to quantify the evolved Hâ‚‚ and Oâ‚‚.

- Success Criterion: The definitive proof of thermodynamic viability is the stoichiometric evolution of Hâ‚‚ and Oâ‚‚ in a 2:1 ratio over several hours, confirming that the photocatalyst can simultaneously drive both half-reactions using only light and water.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for Photocatalytic Research

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| TiOâ‚‚ (P25) | A benchmark photocatalyst (typically ~80% anatase, ~20% rutile) used as a reference material for comparing the activity of newly developed catalysts in both degradation and water splitting tests [25] [23]. |

| Sacrificial Reagents | Methanol/Triethanolamine: Hole scavengers used to assess the maximum reduction (H₂ evolution) capability of a photocatalyst by selectively consuming holes [23]. AgNO₃: An electron scavenger used to assess the maximum oxidation (O₂ evolution) capability of a photocatalyst. |

| Co-catalysts (Pt, NiO) | Nanoparticles loaded onto the photocatalyst surface to act as active sites for specific reactions (e.g., Pt for Hâ‚‚ evolution, NiO for Oâ‚‚ evolution), thereby reducing the activation energy (overpotential) and enhancing charge separation [23]. |

| FTO/ITO Glass | Conductive, transparent substrates essential for fabricating photoelectrodes for Mott-Schottky analysis, photoelectrochemical (PEC) characterization, and sensor development [21]. |

| Reference Electrodes (Ag/AgCl, SCE) | Crucial for calibrating and reporting electrochemical potentials in a three-electrode system, allowing for the accurate determination of band positions and conversion to the NHE scale [21]. |

| Fenoprop ethanolamine | Fenoprop Ethanolamine Salt|CAS 7374-47-2 |

| Dicumene chromium | Dicumene chromium, CAS:12001-89-7, MF:C18H24Cr, MW:292.4 g/mol |

The thermodynamic requirements for photocatalytic water splitting and pollutant degradation serve as the foundational blueprint for designing effective photocatalysts. While water splitting demands a precise straddling of the Hâº/Hâ‚‚ and Oâ‚‚/Hâ‚‚O potentials, pollutant degradation primarily necessitates a highly positive valence band for generating potent oxidizers. The persistent challenge in photocatalysis research is not only finding materials that meet these thermodynamic criteria but also engineering them to possess optimal charge separation kinetics, visible light absorption, and surface reaction rates. Overcoming the rapid recombination of photogenerated electron-hole pairs remains the central hurdle. Future advancements will likely hinge on innovative strategies such as heterojunction construction, defect engineering, and the application of external fields to dynamically control charge behavior, thereby bridging the gap between thermodynamic potential and practical photocatalytic efficiency.

In photocatalytic systems, the conversion of photon energy into chemical energy is governed by a sequence of ultrafast processes involving photogenerated charge carriers. The overall efficiency of photocatalysis is fundamentally limited by the kinetics of three critical stages: charge generation, charge separation, and charge recombination [4]. These processes occur across an extensive range of timescales, from femtoseconds to milliseconds, creating a complex kinetic landscape where productive charge separation must effectively compete with detrimental recombination pathways [21].

Understanding these temporal dynamics is crucial for advancing photocatalytic applications in fields including environmental remediation, solar fuel generation, and organic synthesis. The inherent competition between charge separation and recombination represents the primary kinetic bottleneck in photocatalysis, as the majority of photogenerated charge carriers typically recombine rather than participating in surface redox reactions [4]. This review provides a comprehensive analysis of the timescales, mechanisms, and experimental methodologies central to elucidating and overcoming these kinetic limitations in photocatalytic research.

Fundamental Processes and Characteristic Timescales

The photophysical processes in photocatalysis begin when a semiconductor absorbs photons with energy equal to or greater than its bandgap energy (Eg), generating electron-hole pairs [26]. These charge carriers then undergo various pathways with distinct characteristic timescales, which are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Characteristic Timescales of Key Charge Carrier Processes in Photocatalysis

| Process | Typical Timescale | Key Influencing Factors | Impact on Overall Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Charge Generation | Femtoseconds (fs) to picoseconds (ps) [21] | Photon energy, absorption coefficient, band structure | Determines the initial population of excited states available for subsequent processes. |

| Charge Trapping | <100 femtoseconds (fs) to picoseconds (ps) [4] | Density of surface/defect states, material crystallinity | Localizes charges, can either facilitate or hinder separation. |

| Bulk Recombination | Picoseconds (ps) to nanoseconds (ns) [4] | Crystalline quality, electronic disorder, temperature | Primary loss mechanism; most carriers recombine on this timescale. |

| Charge Separation | <100 fs to tens of picoseconds (ps) [21] [27] | Built-in electric fields, heterojunctions, entropy gain, orbital offsets | Critical step for delivering charges to the surface for reactions. |

| Surface Reaction | Microseconds (μs) to milliseconds (ms) [21] | Catalyst surface activity, concentration of reactants | Productive utilization of separated charges; slowest essential step. |

| Surface Recombination | Nanoseconds (ns) to milliseconds (ms) | Surface passivation, electrolyte composition | Loss of already-separated charges at the interface. |

The efficiency of a photocatalytic system is determined by the race between the productive separation of charges and their migration to the surface (leading to chemical reactions) versus their various recombination pathways. The disparity between the rapid recombination (ps-ns) and the relatively slow surface reactions (μs-ms) constitutes a fundamental kinetic challenge [21] [4]. Consequently, a primary goal of photocatalyst design is to engineer materials and interfaces that can extend the lifetime of separated charges long enough for the slower surface redox reactions to occur.

Experimental Methods for Probing Charge Dynamics

Investigating these ultrafast processes requires specialized spectroscopic techniques capable of temporal resolution from femtoseconds upward. The following table outlines key experimental methods used to dissect charge carrier kinetics.

Table 2: Experimental Techniques for Characterizing Charge Carrier Dynamics

| Technique | Probed Process/Timescale | Measurable Parameters | Key Applications in Kinetics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Femtosecond Transient Absorption Spectroscopy (fs-TAS) | Electron-hole pair relaxation, recombination, trapping (fs to ns) [21] | Decay kinetics of photogenerated electrons/holes | Mapping early-stage charge separation versus bulk recombination dynamics [4]. |

| Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (TRPL) | Radiative recombination of excitons (ns timescale) [21] | Photoluminescence lifetime | Assessing trap state density and non-radiative recombination pathways. |

| Transient Photocurrent/Photovoltage Measurements | Charge separation and extraction efficiency (μs to ms) [21] | Photocurrent decay, charge transfer resistance | Evaluating the efficiency of charge collection at electrodes and interfacial charge transfer. |

| Surface Photoelectrochemical Measurements (SPECMs) | Surface charge transfer and capacitance (ms to s) [21] | Localized surface redox currents | Probing the kinetics of surface reactions and surface recombination. |

| Pump-Push-Probe Spectroscopy | Dynamics of interfacial charge transfer states (ps timescale) [27] | Energetics of charge separation at interfaces | Studying the dissociation of charge-transfer states into free charges, as applied to organic heterojunctions [27]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Pump-Push-Probe Transient Absorption

This advanced technique is used to investigate the energy and dynamics of specific intermediate states, such as interfacial charge-transfer (CT) states.

Objective: To track the evolution and separation of electron-hole pairs at a donor-acceptor heterojunction by selectively exciting trapped CT states with a delayed infrared "push" pulse [27].

Materials:

- Light Source: A femtosecond laser system (e.g., Ti:Sapphire amplifier) generating a primary beam (~100 fs pulses).

- Optical Parametric Amplifiers (OPAs): To generate tunable pump and push pulses (e.g., 750 nm for excitation, 1350 nm for pushing).

- Broadband Probe Pulse: A white-light continuum for detecting absorption changes from visible to near-infrared.

- Spectrometer and Detector: A fast CCD or diode array for recording spectral changes.

- Sample: Thin-film photocatalyst or donor-acceptor blend (e.g., PIPCP:PC61BM polymer:fullerene blend) [27].

Procedure:

- Pump Excitation: The sample is excited by the "pump" pulse (e.g., 750 nm), which generates excitons.

- Exciton Dissociation: Excitons rapidly dissociate at the donor-acceptor interface, forming initially bound CT states (on a ~100-250 fs timescale).

- Push Intervention: After a controllable delay (t_push_, 0.1–15 ps), an infrared "push" pulse (e.g., 1350 nm) resonantly excites the CT states, promoting them to a higher-energy state.

- Probe Detection: A broadband "probe" pulse, delayed relative to the push pulse, measures the resulting changes in absorption (Δ(ΔT/T)).

- Data Analysis: The push-induced signal, which often contains an electroabsorption (EA) feature, is monitored. The growth of the EA signal intensity is directly correlated with the increasing distance between the separating electron-hole pair, allowing the kinetics of free charge formation to be tracked (e.g., over ~5 ps) [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Studying Charge Kinetics

| Item | Function/Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| TiOâ‚‚ (Anatase/Rutile) | Wide bandgap semiconductor (Eg ~3.2 eV); benchmark material for photocatalytic studies [1]. | Model system for probing fundamental charge dynamics and surface reactions. |

| ZnO Nanostructures | Alternative wide bandgap semiconductor; used in nanorods, nanoparticles for charge transport studies [1]. | Investigating the effect of morphology on charge separation and recombination. |

| [6,6]-Phenyl-C61-butyric acid methyl ester (PCBM) | Fullerene-based electron acceptor. | Key component in organic heterojunction studies for probing electron transfer and CT state dynamics [27]. |

| Donor Polymers (e.g., PIPCP) | Semiconducting polymer acting as an electron donor. | Used in bulk heterojunction films with PCBM to model charge separation kinetics with small energy offsets [27]. |

| Scavengers (e.g., AgNO₃, Methanol) | Chemical traps for specific charge carriers (e.g., AgNO₃ for electrons, Methanol for holes). | Used in photodeposition or reaction studies to quantify the flux and lifetime of a specific charge carrier type. |

| Electrolyte Solutions (e.g., Naâ‚‚SOâ‚„) | Inert supporting electrolyte for photoelectrochemical cells. | Enables measurement of photocurrent transients and charge transfer resistance without Faradaic reactions. |

| Tetracycline mustard | Tetracycline mustard, CAS:72-09-3, MF:C27H33Cl2N3O8, MW:598.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 7-Phenoxyquinolin-2(1H)-one | 7-Phenoxyquinolin-2(1H)-one, MF:C15H11NO2, MW:237.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Kinetic Pathways and Limiting Factors

The following diagram illustrates the sequential pathways and kinetic competition between charge generation, separation, recombination, and surface reactions.

Kinetic competition between charge separation and recombination pathways. The green pathway highlights productive charge separation leading to chemical reactions, while red pathways indicate various recombination loss mechanisms. The slow surface reaction rate is a key kinetic bottleneck.

Key Limiting Factors

Energy Offsets and Electronic Disorder: A small offset between the optical bandgap (Eg) and the energy of the interfacial CT state (ECT) reduces the driving force for charge separation. Efficient separation with low offsets (~50 meV), as demonstrated in systems like PIPCP:PCBM, is only possible with exceptionally low electronic disorder (low Urbach energy) [27]. High disorder creates tail states that act as traps, enhancing non-radiative recombination.

Timescale Mismatch: The most significant kinetic limitation is the vast difference between the speed of charge recombination (picoseconds to nanoseconds) and the slower pace of multielectron surface redox reactions (microseconds to milliseconds) [21] [4]. This mismatch means that most separated charges recombine before they can be utilized productively.

Interfacial Charge Transfer: In sensing applications, conventional surface modification with insulating biorecognition molecules (e.g., antibodies, aptamers) can suppress charge transfer, reducing sensitivity [21]. Advanced interface engineering is required to maintain efficient charge transfer while ensuring specificity.

Strategies to Overcome Kinetic Limitations

Several material and interface engineering strategies have been developed to enhance charge separation and suppress recombination:

Heterojunction Engineering: Constructing type-II band alignments or S-scheme heterojunctions can create built-in electric fields that provide a directional driving force for electron-hole separation, effectively pulling them apart before they recombine [28].

Co-catalyst Deposition: Loading noble metal nanoparticles (e.g., Pt, Au) or metal oxide clusters (e.g., IrOâ‚‚, CoOâ‚“) onto semiconductor surfaces acts as charge sinks. These co-catalysts selectively extract specific charges (electrons or holes) and provide active sites for surface reactions, thereby accelerating interfacial charge utilization and reducing surface recombination [21] [1].

Morphological Control: Designing nanostructures with high crystallinity reduces bulk defect density, while short-dimensional morphologies like nanorods or thin films minimize the distance charges must travel to reach the surface, lessening the chance of bulk recombination [4].

Doping and Defect Engineering: Strategic introduction of dopants or controlled creation of defects can modify the electronic band structure, create intermediate energy levels, or passivate harmful trap states, thereby influencing charge trapping and recombination dynamics [26].

The kinetic landscape of photocatalysis is defined by a critical race against time. While charge generation and initial separation occur on ultrafast timescales, recombination processes present a formidable efficiency barrier. The disparity between these rapid recombination events and the slower surface reactions underscores the necessity for innovative material designs that can extend charge carrier lifetimes. Advanced spectroscopic techniques and precise interface engineering continue to provide the tools and strategies needed to navigate this complex kinetic landscape, pushing the boundaries of photocatalytic efficiency for applications in energy and environmental science.

In photocatalytic research, the efficient separation of photogenerated electron-hole pairs is a cornerstone determinant of overall system performance. The journey of these charge carriers, from their initial creation upon light absorption to their eventual participation in surface redox reactions, spans a vast spatio-temporal scale—from femtoseconds to seconds and from microscopic atoms to macroscopic materials [29]. The core challenge that unites the field is that charge carrier recombination is inherently faster than the transfer processes needed for catalytic reactions; consequently, a vast majority of photogenerated carriers recombine uselessly, limiting quantum yields [4]. Therefore, precisely characterizing charge carrier behavior and lifetimes is not merely a diagnostic exercise but is fundamental to the rational design of high-efficiency photocatalytic systems for applications ranging from hydrogen production and CO₂ reduction to environmental remediation [30] [31]. This guide details the advanced experimental techniques that allow researchers to dissect and understand these critical dynamics, providing a foundational toolkit for innovation in photocatalysis.

Fundamental Principles of Charge Carrier Dynamics

The photocatalytic process begins when a semiconductor absorbs a photon with energy greater than or equal to its bandgap ((E_g)), exciting an electron ((e^-)) from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB) and leaving behind a positively charged hole ((h^+)) [4] [32]. This results in the formation of an electron-hole pair. The subsequent fates of these charge carriers follow a competitive pathway:

- Migration: The photo-generated electrons and holes can migrate, either diffusively or coherently, to the surface of the photocatalyst [4] [22].

- Recombination: Electrons can fall back into the VB, recombining with holes. This process can be radiative or non-radiative and results in the loss of the absorbed energy as heat or light. This recombination is kinetically much faster (occurring on picosecond to nanosecond timescales) than the desired charge transfer [4] [29].

- Charge Transfer and Catalysis: If the carriers successfully reach the surface without recombining, they can participate in reduction (electrons) and oxidation (holes) reactions with adsorbed species, such as water protons or COâ‚‚ molecules [31] [32].

The probability of a charge carrier participating in a chemical reaction is fundamentally governed by its lifetime—the time it exists in its excited state before recombination. Longer lifetimes statistically increase the chance of a carrier migrating to a surface active site and driving catalysis. The dynamics of these processes, including carrier diffusion, radiation recombination, and charge separation, are critical for the research and development of material properties [29]. The following diagram illustrates the fundamental pathways and key characterization windows for these processes.

Figure 1: Charge Carrier Pathways and Characterization Windows. Upon light absorption, electron-hole pairs are generated. They either recombine, losing energy, or migrate to drive surface reactions. Techniques like transient absorption and time-resolved luminescence probe different timescales of these dynamics.

Core Characterization Techniques

A suite of sophisticated characterization techniques has been developed to probe the complex lifecycle of charge carriers. The following table summarizes the primary methods, their working principles, and the specific information they yield.

Table 1: Core Techniques for Characterizing Charge Carrier Dynamics

| Technique | Fundamental Principle | Key Measurable Parameters | Temporal Resolution | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Femtosecond Transient Absorption (fs-TA) Spectroscopy [29] | A "pump" pulse excites the sample, and a delayed "probe" pulse monitors changes in absorption. The difference ((\Delta A)) reveals excited-state populations. | Carrier lifetimes, electron-hole separation efficiency, trapping rates, exciton dynamics. | Femtoseconds (fs) to milliseconds (ms) | Mapping full carrier trajectories; studying charge separation at interfaces; quantifying recombination kinetics. |

| Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (TRPL) Spectroscopy [29] [31] | Measures the time-dependent decay of light emission (fluorescence/phosphorescence) after pulsed excitation. | Radiative recombination lifetime, presence of non-radiative pathways, trap state density. | Picoseconds (ps) to nanoseconds (ns) | Probing recombination dynamics in direct-bandgap semiconductors and organic photocatalysts. |

| Time-Resolved Microwave Conductivity (TRMC) [31] | Measures the photoconductivity of a material via its microwave absorption following a laser pulse. Does not require electrical contacts. | Charge carrier mobility, yield of free (mobile) charges versus trapped charges. | Nanoseconds (ns) to microseconds (µs) | Assessing charge carrier mobility in powders and thin films; quantifying free carrier yield. |

| Transient Surface Photovoltage (TSPV) Spectroscopy | Measures the transient change in surface potential after pulsed light excitation. | Surface band bending, kinetics of charge separation and recombination at surfaces/interfaces. | Microseconds (µs) to seconds (s) | Probing interfacial charge transfer in films and devices. |

| Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) Spectroscopy [30] | Detects unpaired electrons (e.g., trapped electrons or holes) in a magnetic field under light irradiation. | Identity and concentration of paramagnetic species (charge traps, defect states, radical intermediates). | Steady-state and time-resolved modes available. | Identifying charge trapping sites; studying the role of defects; tracking radical species during reactions. |

Femtosecond Transient Absorption (fs-TA) Spectroscopy: A Gold Standard

As a powerful tool for studying electron transfer paths, fs-TA spectroscopy can track the quenching path and lifetimes of carriers on femtosecond and picosecond time scales [29]. The principle is based on a "pump-probe" method. An initial ultrafast laser "pump" pulse excites the sample, promoting electrons to create a non-equilibrium population of excited states. A second, weaker "probe" pulse (which can be white light continuum) is then delayed in time and passed through the excited sample. The measured change in optical density ((\Delta A)) of this probe pulse reveals the transient species present.

The resulting spectra typically show three types of signals [29]:

- Ground State Bleaching (GSB): A negative (\Delta A) signal caused by the depletion of the ground state, reducing its absorption.

- Stimulated Emission (SE): A positive (\Delta A) signal arising when the probe photon energy matches the emission energy of the excited state.

- Excited State Absorption (ESA): A positive (\Delta A) signal indicating that the excited state itself absorbs light and is promoted to a higher-lying excited state.

By tracking the evolution of these signals across wavelengths and delay times, a detailed picture of the charge carrier dynamics emerges, from initial exciton formation to charge separation and eventual recombination [29] [22]. The following experimental workflow outlines a typical fs-TA experiment.

Figure 2: Workflow of a Femtosecond Transient Absorption Experiment. A laser pulse is split into pump and probe paths. The pump excites the sample, and the time-delayed probe measures absorption changes, producing a ΔA(t, λ) data map.

Complementary Techniques for a Holistic View

While fs-TA provides a comprehensive view, other techniques offer unique insights:

- Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (TRPL) is exceptionally sensitive to radiative recombination events. The photoluminescence intensity attenuates exponentially with time, and the decay time directly reflects the lifetime of the molecule in the excited state, generally on the order of picoseconds to nanoseconds [29]. This makes it ideal for studying materials like organic polymers and quantum dots where luminescence is a key recombination pathway [31].

- Time-Resolved Microwave Conductivity (TRMC) is uniquely valuable as it measures photoconductivity, which is a product of the charge carrier yield and their mobility. This allows researchers to distinguish between the generation of charge carriers and their ability to move freely through the material, a critical distinction for understanding transport-limited processes [31].

Quantitative Data and Experimental Protocols

Key Kinetic Parameters from Literature

The ultimate goal of these characterization techniques is to extract quantitative kinetic parameters that can be correlated with photocatalytic performance. The following table compiles representative data from recent studies to illustrate typical findings.

Table 2: Representative Charge Carrier Lifetime Data from Photocatalytic Studies

| Photocatalytic System | Technique Used | Observed Lifetime Components | Associated Process | Reported Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| g-C3N4-based COF (CN-306) [33] | Multimodal Characterization / DFT | Enhanced separation efficiency | Suppressed electron-hole recombination due to reduced HOMO-LUMO gap. | Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ production: 5352 µmol gâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹; Quantum Efficiency: 7.27% (λ=420 nm) |

| Organic Photocatalyst Blend (T6/C₆₀) [22] | Real-time TDDFTB-OS Simulation | ~10 fs (electron-hole pair migration) | Initial hopping/delocalization of exciton to D-A interface. | Simulated current emergence supported by vibronic coupling. |

| Conjugated Organic Polymers [31] | Transient Spectroscopy (TA, TRMC) | Varies with molecular structure (ps-µs) | Charge separation vs. recombination; dependent on polymer backbone and side chains. | Hydrogen Evolution Rate correlated with long-lived mobile carriers. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Femtosecond Transient Absorption

This protocol provides a generalized methodology for conducting an fs-TA experiment on a powdered photocatalyst sample [29].

I. Sample Preparation

- Dispersed Sample: For transmission-mode measurements, disperse the photocatalyst powder in a solvent (e.g., ethanol, acetonitrile) to form a homogeneous suspension. Ultrasonicate briefly to break up aggregates.

- Solid Film: Alternatively, prepare a thin, optically dense film of the photocatalyst on a transparent substrate (e.g., quartz) by drop-casting or spin-coating.

- Optical Density: Ensure the sample's optical density at the pump wavelength is between 0.3 and 0.8 to balance signal strength and minimize inner-filter effects.

II. Instrument Setup and Data Acquisition

- Laser System: Utilize a Ti:Sapphire amplified laser system generating ~100 fs pulses at a high repetition rate (1 kHz).

- Pulse Generation: Split the fundamental beam (e.g., 800 nm). The "pump" beam is directed into an optical parametric amplifier (OPA) to tune the excitation wavelength to the desired value (e.g., 420 nm for g-C₃N₄).

- Probe Generation: The other portion of the beam is focused into a sapphire or CaFâ‚‚ crystal to generate a white light continuum probe pulse (typically from UV to NIR).

- Delay Control: Pass the probe beam through a computer-controlled mechanical delay stage that can precisely adjust the optical path length, thereby controlling the time delay between the pump and probe pulses from femtoseconds to nanoseconds.

- Detection: Focus both pulses onto the sample. After transmission, disperse the probe light with a spectrometer onto a high-sensitivity array detector (e.g., CCD or CMOS).

- Data Collection: For each delay time, record the probe spectrum with ((I{pump-on})) and without ((I{pump-off})) the pump pulse. Calculate (\Delta A(\lambda, t) = \log{10}(I{pump-off} / I_{pump-on})). Repeat this over a logarithmic time scale.

III. Data Analysis and Kinetic Modeling

- Global Analysis: Fit the entire (\Delta A(\lambda, t)) dataset to a sum of exponential decays convolved with the instrument response function. This is typically done using a model like: ( \Delta A(\lambda, t) = \sum{i=1}^{n} DADi(\lambda) \cdot \exp(-t/\taui) ) where (DADi(\lambda)) are the Decay-Associated Difference Spectra and (\tau_i) are the characteristic lifetimes.

- Target Analysis: Employ more complex kinetic models (e.g., sequential or reversible) to assign physical states (e.g., singlet exciton, charge-separated state, trapped electron) to the observed components.

- Spectral Interpretation: Identify the spectral signatures of different species (GSB, SE, ESA) and map their evolution to construct a mechanistic picture of the charge carrier journey.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents, materials, and instrumentation critical for experiments in charge carrier characterization.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Charge Carrier Dynamics Studies

| Category / Item | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Semiconductor Precursors (e.g., urea for g-C₃N₄ [33], metal salts for oxides) | Synthesis of the base photocatalyst material with defined composition and minimal impurity-induced recombination centers. | Purity >99% is often critical. Synthetic conditions (temperature, time, atmosphere) dictate final crystallinity, defect density, and morphology. |

| Functionalization Reagents (e.g., terephthalaldehyde, p-nitrobenzaldehyde [33]) | Molecular-level engineering of the electronic structure (e.g., HOMO-LUMO levels, electron cloud density) to enhance charge separation. | Electronic nature (electron-withdrawing/donating) of the substituent profoundly influences electron-hole distribution and separation efficiency. |