Deep Learning for Predicting Inorganic Material Synthesizability: Models, Applications, and Future Directions

The accurate prediction of inorganic material synthesizability is a critical challenge in accelerating the discovery of new functional materials for biomedical and technological applications.

Deep Learning for Predicting Inorganic Material Synthesizability: Models, Applications, and Future Directions

Abstract

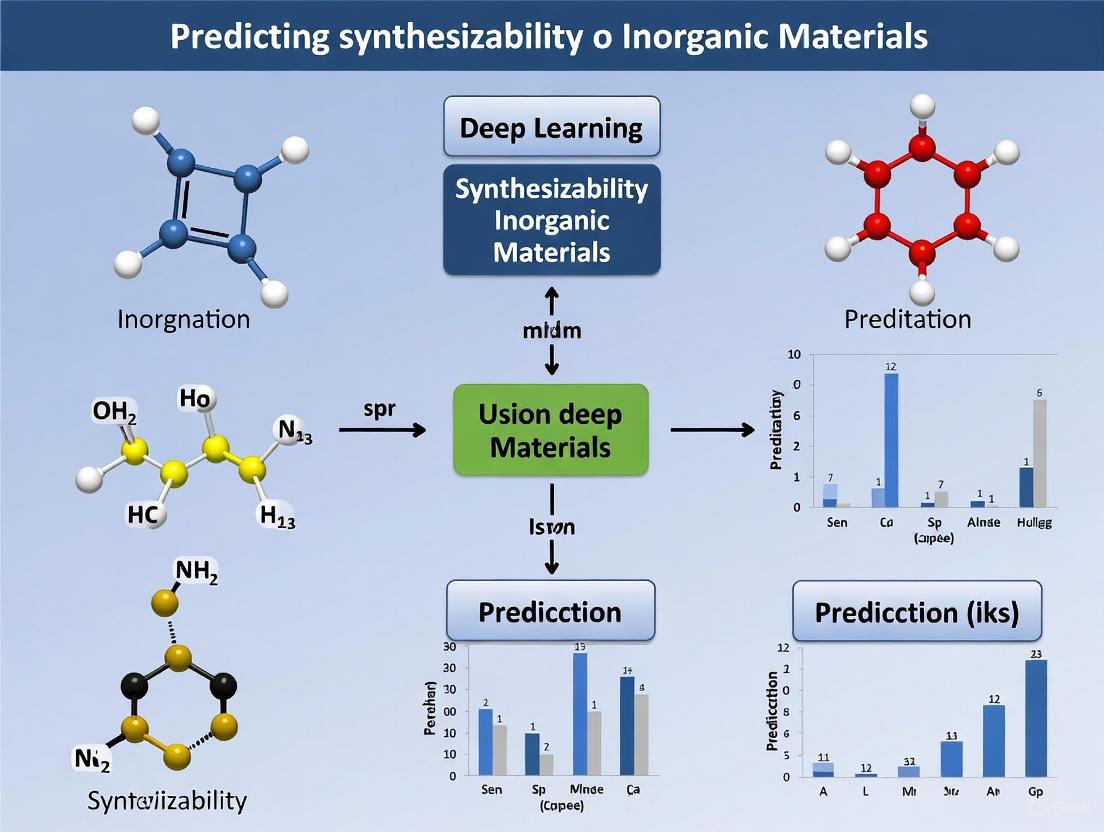

The accurate prediction of inorganic material synthesizability is a critical challenge in accelerating the discovery of new functional materials for biomedical and technological applications. This article provides a comprehensive overview of how deep learning is revolutionizing this field, moving beyond traditional thermodynamic stability metrics. We explore foundational concepts, detail state-of-the-art models like SynthNN, MatterGen, and CSLLM, and address key methodological challenges and optimization strategies. The content further examines rigorous validation frameworks and comparative performance analyses, offering researchers and drug development professionals a practical guide to integrating these powerful AI tools into their discovery pipelines to bridge the gap between computational prediction and experimental realization.

The Synthesizability Challenge: Why Traditional Methods Fall Short in Materials Discovery

The journey of materials design has evolved through four distinct paradigms, from initial trial-and-error experiments and scientific theory to computational methods and the current data-driven machine learning paradigm [1]. While computational methods and generative models have successfully identified millions of theoretically promising materials with exceptional properties, a critical challenge persists: many theoretically predicted materials with favorable formation energies have never been synthesized, while numerous metastable structures with less favorable formation energies are successfully synthesized through kinetic pathways [1]. This fundamental disconnect creates a significant bottleneck in transforming computational predictions into real-world applications.

Synthesizability extends beyond mere thermodynamic stability to encompass the complex kinetic pathways and experimental conditions required to realize a material in practice. Conventional approaches that rely solely on thermodynamic formation energies or energy above the convex hull via density functional theory (DFT) calculations struggle to identify experimentally realizable metastable materials synthesized through kinetically controlled pathways [2] [1]. Similarly, assessments of kinetic stability through computationally expensive phonon spectra analyses have limitations, as material structures with imaginary phonon frequencies can still be synthesized [1]. This gap between theoretical prediction and experimental realization represents one of the most significant challenges in modern materials science.

Defining the Synthesizability Problem

Beyond Thermodynamic and Kinetic Stability

The concept of synthesizability encompasses multiple dimensions that extend far beyond traditional stability metrics. While thermodynamic stability, typically assessed through formation energy and energy above the convex hull, indicates whether a material is stable in its final form, it provides limited insight into whether the material can actually be synthesized. Kinetic stability, evaluated through methods like phonon spectrum analysis, offers additional information but still fails to fully capture the complex reality of synthesis pathways [1].

Synthesizability is fundamentally governed by both equilibrium and out-of-equilibrium descriptors that control synthetic routes and outcomes. The key metrics include free-energy surfaces in multidimensional reaction variable space (including activation energies for nucleation and formation of stable and metastable phases), composition, size and structure of initial and emerging reactants, and various kinetic factors such as diffusion rates of reactive species and the dynamics of their collision and aggregation [3]. This complex interplay explains why materials with favorable formation energies may remain elusive in the laboratory, while metastable structures can be successfully synthesized through carefully designed kinetic pathways.

The Challenge of Metastable Materials

The synthesis of metastable materials presents particular challenges for prediction. Crystalline material growth methods—spanning from condensed matter synthesis to physical or chemical deposition from vapor—often proceed at non-equilibrium conditions, such as in highly supersaturated media, at ultra-high pressure, or at low temperature with suppressed species diffusion [3]. As illustrated in Figure 1(c) of [3], highly non-equilibrium synthetic routes are superimposed on a generalized phase diagram, highlighting the complex pathways to realizing metastable states. For example, strain engineering can stabilize metastable structures, as demonstrated by the suppression of thermodynamically favored phase separation in GaAsSb alloy through strain from a GaAs shell layer [3].

Computational Frameworks for Synthesizability Prediction

Machine Learning Approaches

Recent advances in machine learning have demonstrated promising capabilities in predicting material synthesizability. Earlier approaches include SynthNN for assessing synthesizability based on compositions [1] and positive-unlabeled (PU) learning models that treat structures with unknown synthesizability as negative samples [1]. More recent innovations include teacher-student dual neural networks that improved prediction accuracy for 3D crystals to 92.9% [1].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Synthesizability Prediction Methods

| Method | Accuracy | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Thermodynamic (Energy above hull ≥0.1 eV/atom) | 74.1% | Fails for metastable materials |

| Kinetic (Lowest phonon frequency ≥ -0.1 THz) | 82.2% | Computationally expensive |

| Positive-Unlabeled Learning [1] | 87.9% | Limited dataset scale |

| Teacher-Student Dual Neural Network [1] | 92.9% | Specific to 3D crystals |

| Crystal Synthesis Large Language Models [1] | 98.6% | Requires comprehensive training data |

Large Language Models for Synthesizability Prediction

The most recent breakthrough in synthesizability prediction comes from Large Language Models (LLMs) fine-tuned for materials science applications. The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Models (CSLLM) framework utilizes three specialized LLMs to predict synthesizability, identify synthetic methods, and suggest suitable precursors [1]. This approach represents a significant advancement over traditional methods.

The Synthesizability LLM achieves remarkable accuracy (98.6%) by leveraging a comprehensive dataset of 70,120 synthesizable crystal structures from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database and 80,000 non-synthesizable structures screened from 1,401,562 theoretical structures [1]. This performance substantially outperforms traditional thermodynamic (74.1%) and kinetic (82.2%) screening methods [1]. Furthermore, LLM-based workflows can generate human-readable explanations for synthesizability factors, extract underlying physical rules, and assess their veracity, providing valuable guidance for modifying non-synthesizable hypothetical structures [4].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Dataset Construction for ML Models

The construction of balanced and comprehensive datasets is crucial for developing robust synthesizability prediction models. The protocol established by [1] involves:

- Positive Sample Selection: Meticulously select 70,120 crystal structures from ICSD with no more than 40 atoms and seven different elements, excluding disordered structures.

- Negative Sample Identification: Employ a pre-trained PU learning model to generate CLscores for 1,401,562 theoretical structures, selecting 80,000 structures with the lowest CLscores (CLscore <0.1) as non-synthesizable examples.

- Dataset Validation: Compute CLscores for positive examples, confirming that 98.3% have CLscores greater than 0.1, validating the threshold selection.

The resulting dataset covers seven crystal systems with cubic being most prevalent, structures with 1-7 elements (predominantly 2-4 elements), and atomic numbers 1-94 from the periodic table [1]. This comprehensive coverage ensures the model encounters diverse structural chemistry during training.

Text Representation for Crystal Structures

To enable LLMs to process crystal structures, researchers have developed efficient text representations. The CIF and POSCAR formats contain redundant information or lack symmetry data [1]. The "material string" representation overcomes these limitations by integrating essential crystal information in a concise format [1]:

Where SP represents chemical symbols and proportions, a, b, c, α, β, γ are lattice parameters, AS-WS[WP-x,y,z] denotes atomic symbol, Wyckoff site symbol, and fractional coordinates, and SG is the space group [1]. This representation enables efficient LLM fine-tuning while preserving critical structural information.

The CSLLM Framework Architecture

The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Models framework employs three specialized LLMs working in concert [1]:

- Synthesizability LLM: Predicts whether a structure is synthesizable (98.6% accuracy)

- Method LLM: Classifies possible synthetic methods (91.0% accuracy)

- Precursor LLM: Identifies suitable precursors (80.2% success rate)

This integrated approach bridges the gap between theoretical prediction and practical synthesis by providing comprehensive guidance for experimental realization.

Quantitative Performance Analysis

Benchmarking Predictive Accuracy

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of Synthesizability Prediction Models

| Model/Method | Accuracy | Dataset Size | Material Scope | Additional Capabilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy above hull (≥0.1 eV/atom) [1] | 74.1% | N/A | All inorganic | Thermodynamic stability only |

| Phonon frequency (≥ -0.1 THz) [1] | 82.2% | N/A | All inorganic | Kinetic stability assessment |

| PU Learning [1] | 87.9% | ~150,000 | 3D crystals | Binary classification |

| Teacher-Student Network [1] | 92.9% | ~150,000 | 3D crystals | Improved accuracy |

| CSLLM Framework [1] | 98.6% | 150,120 | 3D crystals | Synthesis method and precursor prediction |

The exceptional performance of the CSLLM framework is further demonstrated by its generalization ability, achieving 97.9% accuracy on complex structures with large unit cells that considerably exceed the complexity of the training data [1]. This demonstrates the model's capacity to learn fundamental principles of synthesizability rather than merely memorizing training examples.

Experimental Validation and Applications

The practical utility of synthesizability prediction frameworks is validated through real-world applications. The synthesizability-driven crystal structure prediction framework successfully reproduced 13 experimentally known XSe structures and filtered 92,310 potentially synthesizable structures from 554,054 candidates predicted by GNoME [2]. Additionally, eight thermodynamically favorable Hf-X-O structures were identified, with three HfV₂O₇ candidates exhibiting high synthesizability [2].

The explainability of LLM-based approaches provides additional value by generating human-readable explanations for synthesizability decisions, helping chemists understand the factors governing synthesizability and guiding modifications to make hypothetical structures more feasible for materials design [4].

Table 3: Essential Resources for Synthesizability Prediction Research

| Resource/Reagent | Function | Specifications/Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [1] | Source of synthesizable structures | 70,120 structures with ≤40 atoms and ≤7 elements |

| Materials Project, CMD, OQMD, JARVIS [1] | Source of theoretical structures | 1.4+ million structures for negative sample selection |

| Material String Representation [1] | Text encoding for crystal structures | SP | a, b, c, α, β, γ | (AS-WS[WP-x,y,z]) | SG format |

| PU Learning Model [1] | Negative sample identification | CLscore threshold <0.1 for non-synthesizable examples |

| Fine-tuned LLMs (CSLLM) [1] | Synthesizability prediction | Three specialized models for synthesizability, methods, precursors |

| Wyckoff Position Analysis [2] | Symmetry-guided structure derivation | Identifies promising subspaces for synthesizable structures |

| Graph Neural Networks [1] | Property prediction | Predicts 23 key properties for synthesizable candidates |

The definition of synthesizability has evolved from simplistic thermodynamic stability metrics to a multifaceted concept encompassing kinetic pathways, precursor selection, and synthetic conditions. The integration of machine learning, particularly large language models, has dramatically improved our ability to predict synthesizability, with accuracy rates now exceeding 98% [1]. This breakthrough enables researchers to focus experimental efforts on theoretically predicted materials with high likelihood of successful synthesis.

Future advancements in synthesizability prediction will likely involve even closer integration of experimental synthesis, in situ monitoring, and computational design. As noted in [3], "the idea of extending computational material discovery to in silico synthesis design is still in its nascent state," but advances in modelling, in situ measurements, and increasing computational power will pave the way for it to become a reality. The development of techniques and tools to propose efficient synthetic pathways will remain one of the major challenges for predicting new material synthesizability, potentially unlocking unprecedented opportunities for the targeted discovery of novel functional materials.

The Limitations of Charge-Balancing and Formation Energy Calculations

The discovery of novel inorganic crystalline materials is a cornerstone of technological advancement. A critical first step in this process is identifying chemical compositions that are synthesizable—that is, synthetically accessible with current capabilities, regardless of whether they have been reported yet [5]. For decades, computational materials discovery has relied on two fundamental principles to predict synthesizability: charge-balancing of ionic charges and the calculation of thermodynamic formation energy. While chemically intuitive, these methods are proxy metrics that do not fully capture the complex physical and economic factors influencing synthetic feasibility. This whitepaper details the quantitative limitations of these traditional approaches and frames them within the emerging paradigm of deep learning, which learns the principles of synthesizability directly from comprehensive experimental data.

Quantitative Limitations of Traditional Methods

The following table summarizes the key performance metrics of traditional synthesizability predictors, highlighting their specific shortcomings.

Table 1: Performance and Limitations of Traditional Synthesizability Predictors

| Method | Core Principle | Reported Performance Limitation | Primary Reason for Failure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Charge-Balancing [5] | Net ionic charge must be neutral for common oxidation states. | - Identifies only 37% of known synthesized inorganic materials.- For binary cesium compounds: only 23% are charge-balanced. | Overly inflexible; cannot account for metallic, covalent, or other non-ionic bonding environments. |

| Formation Energy (DFT) [5] | Material should have no thermodynamically stable decomposition products (e.g., energy above hull ~0 eV/atom). | - Captures only ~50% of synthesized inorganic crystalline materials. | Fails to account for kinetic stabilization and non-equilibrium synthesis pathways. |

| Kinetic Stability (Phonon) [6] | Absence of imaginary phonon frequencies in the spectrum. | - Not a definitive filter; materials with imaginary frequencies can be synthesized. | Does not consider synthesis conditions that can bypass kinetic barriers. |

Detailed Examination of Charge-Balancing

The charge-balancing approach is a computationally inexpensive heuristic. It filters candidate materials by requiring that the sum of the cationic and anionic charges, based on commonly accepted oxidation states, equals zero. This principle is rooted in the chemistry of ionic solids.

Experimental Protocol for Validating Charge-Balancing

To quantitatively assess the validity of this method, one can perform the following data-mining experiment:

- Data Source: Extract the chemical formulas of all experimentally synthesized inorganic crystalline materials from a comprehensive database such as the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [5].

- Algorithm Implementation:

- For each chemical formula in the ICSD, determine the common oxidation state for each element (e.g., Na=+1, O=-2, Fe=+2/+3, etc.).

- For each combination of oxidation states, calculate the net charge for the formula unit.

- Classify a material as "charge-balanced" if any combination of common oxidation states results in a net charge of zero.

- Performance Calculation: The precision of the charge-balancing method is calculated as the percentage of materials in the ICSD that are classified as charge-balanced.

This protocol reveals that charge-balancing is an poor predictor, successfully identifying only 37% of known materials. Its failure is particularly pronounced in metallic systems and even in highly ionic binaries like cesium compounds, where only 23% are charge-balanced [5]. This indicates that synthetic chemistry often stabilizes non-stoichiometric phases or compounds with oxidation states that deviate from simple heuristic rules.

Detailed Examination of Formation Energy Calculations

Formation energy, typically calculated using Density Functional Theory (DFT), is a more sophisticated metric. It evaluates thermodynamic stability by comparing the energy of a compound to its constituent elements or competing phases.

Computational Protocol for Formation Energy

The standard workflow for calculating the formation energy of a compound, ( AlBm ), is as follows [7]:

- Reference States: Establish the total energy per atom for the elemental ground states, ( \mu^{(0)}(A) ) and ( \mu^{(0)}(B) ). For oxygen, the reference is typically the Oâ‚‚ molecule, ( \mu^{(0)}(O) = 0.5 \times E{total}(O2) ).

- DFT Calculation: Perform a converged DFT calculation to obtain the total energy of the compound, ( E{total}(AlB_m) ).

- Energy Calculation: The formation energy per formula unit is calculated as: ( E{form}(AlBm) = E{total}(AlBm) - [l \times \mu^{(0)}(A) + m \times \mu^{(0)}(B)] )

For defect formation energy calculations, the protocol is more complex, involving supercell models and accounting for the Fermi energy and charge state [8] [9]: ( \Delta E{D,q} = E{D,q} - E{H} + \sumi ni \mui + E{corr} + qEF ) where ( E{D,q} ) is the energy of the defective supercell, ( EH ) is the energy of the host (perfect) supercell, ( ni ) and ( \mui ) are the number and chemical potential of added/removed atoms, ( E{corr} ) is a correction for spurious electrostatic interactions, and ( qEF ) is the energy from electron exchange with the Fermi reservoir.

Inherent Limitations and Systematic Errors

Despite its foundational role, the formation energy approach faces several critical limitations:

- Systematic DFT Errors: (Semi-)local DFT functionals suffer from well-known issues, such as the over-binding of the Oâ‚‚ molecule, which systematically skews oxide formation energies [7]. For transition metal oxides, the self-interaction error of localized d-electrons leads to inaccurate total energies and band gaps, necessitating empirical corrections like DFT+U [7].

- Ignoring Kinetic Stabilization: Formation energy is a ground-state thermodynamic property. It cannot account for materials that are synthesized in metastable states through kinetically controlled pathways. Many successfully synthesized materials, such as certain metastable polymorphs of silicon, have positive formation energies with respect to the convex hull [6].

- Dependence on Synthesis Conditions: The stability of a phase, particularly its defect profile, depends on the chemical environment during synthesis (e.g., O-rich or O-poor conditions), which is represented by the elemental chemical potentials (( \mu_i )) in the formation energy equation [8]. A single formation energy value cannot encompass this variable experimental reality.

The Deep Learning Paradigm for Synthesizability

Deep learning models reformulate material discovery as a synthesizability classification task, learning directly from the entire landscape of known materials without relying on pre-defined physical rules [5].

Workflow of a Deep Learning Model for Synthesizability

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow for training and applying a deep learning model like SynthNN.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental workflow in this field relies on key computational "reagents" as listed below.

Table 2: Essential Resources for Synthesizability Prediction Research

| Resource Name | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [5] [6] | Materials Database | The primary source of positive data (synthesized materials) for training and benchmarking models. |

| Materials Project (MP) Database [6] [7] | Computational Materials Database | A source of calculated material properties and a pool for generating candidate structures, including those not yet synthesized. |

| atom2vec [5] | Compositional Representation | A deep learning-based featurization method that learns optimal elemental representations directly from data, avoiding manual feature engineering. |

| Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning [5] [6] | Machine Learning Framework | A semi-supervised algorithm that handles the lack of confirmed negative examples by treating un-synthesized materials as unlabeled data. |

| DFT+U & Anion Corrections [7] | Computational Chemistry Correction | Empirical methods to correct systematic errors in DFT-calculated formation energies of transition metal oxides and other challenging systems. |

Performance Comparison and Workflow Integration

Advanced deep learning models like SynthNN and the Crystal Synthesis Large Language Model (CSLLM) have demonstrated superior performance. SynthNN achieves 1.5x higher precision in discovering synthesizable materials than the best human expert and completes the task five orders of magnitude faster [5]. The CSLLM framework reports a remarkable 98.6% accuracy in classifying synthesizable crystal structures, significantly outperforming formation energy-based (74.1%) and phonon-based (82.2%) methods [6].

These models can be seamlessly integrated into computational screening workflows. As shown in the diagram below, they act as a final, intelligent filter that prioritizes candidates for experimental synthesis based on learned synthesizability, dramatically increasing the success rate of discovery campaigns [5].

Charge-balancing and formation energy calculations, while foundational to materials science, are insufficient proxies for predicting the synthesizability of inorganic crystalline materials. Quantitative analyses reveal that charge-balancing misses a majority of known compounds, while thermodynamic stability fails to capture the reality of metastable synthesis. The integration of deep learning models, which learn the complex, multi-faceted principles of synthesizability directly from experimental data, represents a paradigm shift. These models, such as SynthNN and CSLLM, have proven to outperform both traditional computational methods and human experts, offering a robust and efficient path to bridging the gap between theoretical prediction and experimental realization in materials discovery.

The Critical Gap Between Computational Prediction and Experimental Synthesis

The discovery of novel inorganic materials has been revolutionized by computational methods, particularly high-throughput density functional theory (DFT) calculations. These approaches can screen thousands of theoretical compounds to identify candidates with promising electronic, catalytic, or structural properties. However, a critical bottleneck persists: many computationally-predicted materials with excellent properties cannot be reliably synthesized in laboratory conditions. This disparity between theoretical prediction and experimental realization represents the synthesizability gap, a fundamental challenge in materials science that slows the translation of predicted materials into practical applications.

The root of this gap lies in the fundamental difference between how stability is assessed computationally versus what is required for experimental synthesis. Traditional computational screening heavily relies on thermodynamic stability, typically measured by the energy above the convex hull. While this metric identifies compounds that are thermodynamically stable, experimental synthesis often proceeds through kinetically controlled pathways that access metastable materials. Furthermore, synthesis outcomes depend on numerous difficult-to-model factors including precursor selection, reaction conditions, and activation barriers. Bridging this divide requires new approaches that move beyond purely thermodynamic considerations to develop a fundamental understanding and predictive capability for which materials can be synthesized and under what conditions.

Quantifying the Gap: Performance of Current Approaches

Traditional computational methods for assessing synthesizability show significant limitations when compared to emerging data-driven approaches. The quantitative performance gap is substantial, as illustrated by the following comparative data.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Synthesizability Prediction Methods

| Prediction Method | Key Metric | Reported Accuracy | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermodynamic (Energy Above Hull ≥0.1 eV/atom) [6] | Formation Energy | 74.1% | Fails for metastable, kinetically stabilized phases |

| Kinetic (Phonon Frequency ≥ -0.1 THz) [6] | Dynamic Stability | 82.2% | Computationally expensive; imaginary frequencies don't preclude synthesis |

| Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning [6] | CLscore | 87.9% (3D Crystals) | Relies on heuristic identification of negative examples |

| Teacher-Student Dual Neural Network [6] | Classification | 92.9% (3D Crystals) | Architecture complexity |

| Crystal Synthesis LLM (CSLLM) [6] | Classification | 98.6% | Requires extensive, balanced dataset |

The data reveals that modern machine learning methods, particularly large language models (LLMs) fine-tuned on crystal structure data, substantially outperform traditional physics-based metrics. The CSLLM framework achieves a remarkable 98.6% accuracy by leveraging a comprehensive dataset of both synthesizable and non-synthesizable structures, demonstrating the power of data-driven approaches to capture the complex factors influencing synthesizability [6].

AI-Driven Solutions for Bridging the Gap

Machine Learning with Physics-Aware Descriptors

One promising approach integrates materials science intuition with machine learning. The Materials Expert-Artificial Intelligence (ME-AI) framework translates experimental intuition into quantitative descriptors. In one implementation, researchers curated a dataset of 879 square-net compounds with 12 experimentally accessible features, including electron affinity, electronegativity, and structural parameters like the "tolerance factor" (t-factor) defined as the ratio of square lattice distance to out-of-plane nearest neighbor distance (d~sq~/d~nn~) [10]. By training a Dirichlet-based Gaussian-process model with a chemistry-aware kernel on this expert-curated data, ME-AI not only recovered the known t-factor descriptor but also identified hypervalency as a decisive chemical lever for predicting topological semimetals [10]. This demonstrates how AI can formalize and extend human expertise to create more accurate synthesizability predictors.

Large Language Models for Crystal Synthesis

The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Models (CSLLM) framework represents a breakthrough by treating synthesizability prediction as a text-based reasoning task. This approach utilizes three specialized LLMs that respectively predict: (1) whether a crystal structure is synthesizable, (2) the appropriate synthetic method (solid-state or solution), and (3) suitable precursors [6].

The key innovation lies in representing crystal structures through a text-based "material string" that encodes essential crystal information, allowing LLMs to process structural data efficiently. This system was trained on a balanced dataset of 70,120 synthesizable structures from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) and 80,000 non-synthesizable structures identified from theoretical databases using a pre-trained PU learning model [6]. Beyond just predicting synthesizability, this multi-model approach provides specific guidance on how materials should be synthesized, directly addressing the translation from prediction to experimental practice.

Multi-Agent Autonomous Systems

For end-to-end materials discovery, multi-agent AI systems like SparksMatter represent the cutting edge. These systems employ multiple specialized AI agents that collaborate to execute the full materials discovery cycle—from ideation and planning to experimentation and iterative refinement [11]. SparksMatter operates through an "ideation–planning–experimentation–expansion" pipeline where different agents interpret user queries, generate hypotheses, create detailed experimental plans, execute computations using domain-specific tools (like retrieving known materials from databases or generating novel structures with diffusion models), and synthesize comprehensive reports [11]. This approach integrates synthesizability assessment directly into the materials design process, ensuring that proposed materials are both functionally promising and experimentally realizable.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Workflow for Synthesizability-Driven Crystal Structure Prediction

Synthesizability-Driven CSP Workflow [2]

This workflow integrates computational chemistry with machine learning to prioritize synthesizable candidates:

- Symmetry-Guided Structure Derivation: Generate candidate structures by exploring different symmetry operations and Wyckoff positions within target space groups [2].

- Wyckoff Position Analysis: Encode crystal structures based on their Wyckoff representations to create features suitable for machine learning models [2].

- Machine Learning Synthesizability Evaluation: Apply a fine-tuned synthesizability model to score candidates. This model is trained on recently synthesized structures to enhance predictive accuracy for experimental feasibility [2].

- Ab Initio Calculations: Perform first-principles density functional theory (DFT) calculations on high-scoring candidates to verify thermodynamic stability and electronic properties [2].

- Candidate Filtering: Integrate synthesizability scores with thermodynamic stability to identify the most promising candidates for experimental validation [2].

This approach successfully reproduced 13 experimentally known XSe (X = Sc, Ti, Mn, Fe, Ni, Cu, Zn) structures and filtered 92,310 potentially synthesizable candidates from 554,054 initial predictions [2].

High-Throughput Experimental Validation

For organic reaction feasibility, which faces similar synthesizability challenges, researchers have developed robust Bayesian deep learning frameworks validated through high-throughput experimentation (HTE):

- Diversity-Guided Substrate Sampling: Categorize reactants (e.g., carboxylic acids and amines) based on the carbon atom attached to the reaction center. Use MaxMin sampling within categories to ensure structural diversity that represents the broader chemical space of interest [12].

- Automated HTE Platform Operation: Execute thousands of distinct reactions in parallel using automated platforms like ChemLex's Automated Synthesis Lab (CASL-V1.1). The described system conducted 11,669 distinct acid-amine coupling reactions in 156 instrument hours [12].

- Reaction Outcome Analysis: Determine reaction yields using uncalibrated ratios of ultraviolet (UV) absorbance in liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) [12].

- Bayesian Neural Network Training: Train models on HTE data to predict reaction feasibility. The described BNN model achieved 89.48% accuracy for reaction feasibility prediction [12].

- Uncertainty Analysis for Robustness: Use fine-grained uncertainty disentanglement to identify out-of-domain reactions and evaluate reaction robustness against environmental factors for scale-up [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational and Experimental Resources

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Role in Synthesizability Prediction |

|---|---|---|

| ML Frameworks | XGBoost, Gaussian Process Models, Bayesian Neural Networks [10] [13] [12] | Learn complex relationships between material features and synthesizability from data |

| Large Language Models (LLMs) | Crystal Synthesis LLM (CSLLM), SparksMatter Multi-Agent System [6] [11] | Predict synthesizability, synthetic methods, and precursors from text-based structure representations |

| Materials Databases | ICSD, Materials Project, CSD, CoRE MOF [10] [6] [14] | Provide experimental and computational data for training and validation |

| Structure Generation | MatterGen, Symmetry-Guided Derivation [2] [11] | Generate novel, chemically valid crystal structures for discovery |

| High-Throughput Experimentation | Automated Synthesis Platforms (e.g., CASL-V1.1) [12] | Rapidly generate experimental data for training and model validation |

| Domain-Specific Tools | DFT Calculators, Phonon Analysis, Phase Diagram Tools [2] [6] [11] | Provide physical constraints and validate stability |

| 3,4,4-trimethylhepta-2,5-dienoyl-CoA | 3,4,4-Trimethylhepta-2,5-dienoyl-CoA|Research Use Only | 3,4,4-Trimethylhepta-2,5-dienoyl-CoA is a multi-methyl-branched fatty acyl-CoA for metabolic disease research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Fosbretabulin Tromethamine | Fosbretabulin Tromethamine | Fosbretabulin tromethamine (CA4P) is a potent vascular disrupting agent for cancer research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Integrated Workflow for Synthesizable Materials Design

Multi-Agent Materials Design Workflow [11]

This integrated workflow demonstrates how modern AI systems address synthesizability throughout the discovery process:

- Ideation Phase: Scientist agents interpret user queries and generate innovative, testable hypotheses for materials meeting desired objectives [11].

- Planning Phase: Planner agents translate high-level ideas into structured, executable research plans with specific tasks and tool invocations [11].

- Execution Phase: Assistant agents implement the plan by generating code, interacting with domain-specific tools (database queries, structure generation, property prediction), and collecting results [11].

- Reflection Phase: The system continuously evaluates outputs, adapts plans based on new information, and ensures all necessary data is gathered to support hypotheses [11].

- Reporting Phase: A critic agent synthesizes all information into a comprehensive scientific report, identifying synthesizable candidate materials and suggesting validation steps [11].

The critical gap between computational prediction and experimental synthesis is being bridged through integrated approaches that combine data-driven methods with materials science expertise. The most promising frameworks move beyond thermodynamic stability to incorporate kinetic factors, precursor compatibility, and reaction condition optimization. Key advancements include the development of specialized LLMs for crystal synthesizability prediction, multi-agent systems for autonomous materials design, and high-throughput experimental validation that provides crucial data for model training.

Future progress will depend on expanding and curating high-quality experimental datasets, particularly including "negative" results from failed synthesis attempts. Improved text representations for crystal structures and enhanced uncertainty quantification will further increase the reliability of synthesizability predictions. As these technologies mature, they will accelerate the discovery of novel functional materials by ensuring that computationally predicted candidates are not only theoretically promising but also experimentally realizable.

The discovery of novel inorganic materials is a cornerstone of technological advancement, driving innovations in areas from clean energy to drug development. Traditionally guided by experimental intuition and trial-and-error, this process is being revolutionized by deep learning and large-scale computational screening. Central to this paradigm shift are three pivotal data resources: the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD), the Materials Project (MP), and the Alexandria database. These repositories provide the structured data essential for training deep learning models to predict material stability and, more critically, synthesizability—the probability that a computationally predicted material can be successfully realized in the laboratory. This technical guide examines the distinct roles, integration, and application of these datasets within modern deep learning frameworks for synthesizability prediction, providing researchers with a detailed overview of the data landscape and associated methodologies.

Core Dataset Landscape and Quantitative Comparison

The ecosystem of materials databases comprises both experimentally derived and computationally generated data, each serving a unique function in the machine learning pipeline. The table below provides a quantitative summary of the three core datasets.

Table 1: Key Features of Core Materials Datasets

| Dataset | Primary Content & Scope | Data Volume & Key Metrics | Primary Use in ML/DL |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICSD (Inorganic Crystal Structure Database) [15] | Experimentally determined inorganic and organometallic crystal structures; the world's largest database of its kind. | Contains over 16,000 new entries added annually; includes both experimental and theoretical structure models. | Source of ground-truth data for "synthesizable" labels; training and benchmarking models to distinguish theoretically stable from experimentally realized structures [16]. |

| Materials Project (MP) [17] [18] | A vast repository of density functional theory (DFT)-computed properties for both known and hypothetical inorganic crystals. | Provides data for hundreds of thousands of materials; a common source for stable crystal structures used in model training [17]. | Foundation for training property predictors and generative models; provides formation energies and stability metrics (e.g., energy above convex hull) for model training [18] [17]. |

| Alexandria [18] | A large-scale collection of predicted crystal structures, expanding the space of known stable materials. | Part of a combined dataset (Alex-MP-20) with over 600,000 stable structures used for training foundational models [18]. | Used to massively expand the training data and discovery space for generative models, enabling exploration of compositions with >4 unique elements [17]. |

The interoperability of these datasets is crucial for comprehensive research. Initiatives like the OPTIMADE consortium aim to address the historical fragmentation of materials databases by providing a standardized API, allowing simultaneous querying across multiple major databases, including MP, AFLOW, and the Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD) [19]. Furthermore, researchers often create consolidated datasets for specific modeling tasks. For instance, the Alex-MP-20 dataset, which unites structures from the Materials Project and Alexandria, was curated to pretrain the MatterGen generative model [18]. Similarly, the Alex-MP-ICSD dataset, which also incorporates ICSD data, serves as a broader reference for calculating convex hull stability and verifying the novelty of generated materials [18].

The Synthesizability Challenge in Materials Discovery

A fundamental challenge in computational materials discovery is the gap between thermodynamic stability and practical synthesizability. While density functional theory (DFT) can effectively identify low-energy, thermodynamically stable structures at zero Kelvin, it often overlooks finite-temperature effects, entropic factors, and kinetic barriers that govern whether a material can actually be synthesized in a laboratory [16]. This leads to a critical bottleneck: the number of predicted inorganic crystals now exceeds the number of experimentally synthesized compounds by more than an order of magnitude [16].

The primary challenge is thus to distinguish purported stable structures from truly synthesizable ones. For example, the Materials Project lists 21 SiOâ‚‚ structures very close to the convex hull in energy, yet the common cristobalite phase is not among them [16]. This highlights the pressing need for accurate synthesizability assessments to steer experimental efforts toward laboratory-accessible compounds. Synthesizability is formally defined in machine learning efforts as the probability that a compound, represented by its composition ( xc ) and crystal structure ( xs ), can be prepared in the lab using available methods, with a binary label ( y \in {0,1} ) indicating its experimental verification [16].

Methodological Framework for Synthesizability Prediction

Predicting synthesizability requires a multi-faceted approach that integrates different data types and modeling strategies. The following diagram illustrates a typical workflow for a synthesizability-guided discovery pipeline.

Synthesizability Prediction Workflow

Data Curation and Labeling

A critical first step is constructing a high-quality dataset for model training. A common methodology involves using the Materials Project as a source due to its consistency. A material's composition is labeled as synthesizable (( y=1 )) if any of its polymorphs is linked to an experimental entry in the ICSD. Conversely, a composition is labeled as unsynthesizable (( y=0 )) if all its polymorphs are flagged as theoretical [16]. This approach ensures clear supervision without the artifacts often present in raw experimental data, such as non-stoichiometry or partial occupancies. One such curated dataset contained 49,318 synthesizable and 129,306 unsynthesizable compositions [16].

Model Architectures and Training

State-of-the-art approaches use a dual-encoder architecture to integrate complementary information from a material's composition and its crystal structure [16]:

- Compositional Encoder (( f_c )): Models such as a fine-tuned MTEncoder transformer process the stoichiometry or engineered composition descriptors to output a compositional synthesizability score [16].

- Structural Encoder (( fs )): Graph neural networks (GNNs), such as models fine-tuned from the JMP architecture, operate on crystal structure graphs (( xs )) to output a structure-based score [16].

These encoders are typically pre-trained on large datasets and then fine-tuned end-to-end for the binary classification task, minimizing binary cross-entropy loss.

Ranking and Ensemble Methods

Instead of relying on raw probability thresholds, a rank-average ensemble (Borda fusion) is often used for candidate screening. The probabilities from the composition (( sc )) and structure (( ss )) models are converted to ranks. The final RankAvg score is the average of these normalized ranks, providing a robust metric for prioritizing the most promising candidates from a large pool (e.g., millions of structures) [16].

Experimental Validation and Synthesis Planning

The ultimate test of a synthesizability model is its success in guiding the experimental synthesis of new materials. After high-priority candidates are identified, the pipeline proceeds to synthesis planning and validation.

Synthesis Pathway Prediction

For the prioritized candidates, synthesis pathways must be predicted. This is often a two-stage process:

- Precursor Suggestion: Models like Retro-Rank-In are applied to produce a ranked list of viable solid-state precursors for each target material [16].

- Process Parameter Prediction: Models like SyntMTE then predict necessary conditions, such as calcination temperature, required to form the target phase. The reaction is balanced, and precursor quantities are calculated [16]. These models are typically trained on literature-mined corpora of solid-state synthesis recipes.

High-Throughput Experimental Execution

The final stage involves experimental validation in a high-throughput laboratory. Selected targets are processed in batches. Precursors are weighed, ground, and calcined in a muffle furnace. The resulting products are then characterized automatically, typically via X-ray diffraction (XRD), to verify if the synthesized product matches the target crystal structure [16]. This integrated approach has demonstrated the ability to characterize multiple samples in a matter of days, successfully synthesizing target structures that were initially identified from million-structure screening pools [16].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Experimental Validation

| Reagent / Solution | Function & Application in the Pipeline |

|---|---|

| Solid-State Precursors | The foundational chemical reagents selected by precursor-suggestion models; they are mixed and reacted to form the target inorganic material [16]. |

| SYNTHIA Retrosynthesis Software | A computational tool that uses expert-coded chemistry rules and real-world data to rapidly plan and optimize synthetic routes for proposed molecules, bridging virtual design and lab synthesis [20]. |

| AIDDISON Generative AI | A platform that employs generative AI and predictive insights to design novel molecules, often used in conjunction with SYNTHIA for an end-to-end drug design toolkit [20]. |

| Thermo Scientific Thermolyne Muffle Furnace | A key piece of laboratory equipment used for the high-temperature calcination step in solid-state synthesis, enabling the formation of the target crystalline phase from precursors [16]. |

Emerging Frontiers and Integrative Tools

The field is rapidly evolving with several key trends shaping the next generation of synthesizability prediction.

Foundational Generative Models

Models like MatterGen represent a significant advancement as foundational generative models for materials design [18]. MatterGen is a diffusion-based model that generates stable, diverse inorganic materials across the periodic table. It can be fine-tuned to steer generation toward desired chemical compositions, symmetries, and properties. Critically, structures generated by MatterGen are more than twice as likely to be stable and new compared to previous models, and the model has demonstrated the ability to rediscover thousands of experimentally verified structures from the ICSD that were not in its training data, showcasing an emergent understanding of synthesizability [18].

Specialized Synthesis Databases

The development of specialized, large-scale datasets for material synthesis is a crucial enabler for more accurate synthesis planning. The recently introduced MatSyn25 dataset is a large-scale open dataset containing 163,240 entries of synthesis process information for 2D materials, extracted from high-quality research articles [21]. Such resources are vital for training next-generation models that can predict not just if a material is synthesizable, but how.

Unified API and Standardization

Community-driven initiatives like the OPTIMADE consortium are tackling the problem of database interoperability. By providing a standardized API, OPTIMADE allows simultaneous querying across numerous major materials databases, making the fragmented landscape of computational and experimental data more accessible for large-scale analysis and model training [19].

The synergistic use of the ICSD, Materials Project, and Alexandria databases is fundamental to advancing the prediction of inorganic material synthesizability using deep learning. The ICSD provides the essential experimental ground truth, the Materials Project offers a vast corpus of consistent computational data for initial model training, and Alexandria-like resources expand the exploration space. The integration of composition and structure-based models, coupled with robust ranking methods and automated experimental validation, creates a powerful pipeline that is transforming materials discovery from a slow, intuition-guided process into a rapid, data-driven endeavor. As generative models, synthesis databases, and data infrastructure continue to mature, the ability to reliably design and realize new functional materials in the laboratory will only accelerate.

Deep Learning Architectures for Synthesizability Prediction: From Composition to Crystal Structure

The discovery of new inorganic crystalline materials is a cornerstone for technological advancements in fields ranging from renewable energy to electronics. While computational models and high-throughput density functional theory (DFT) calculations have dramatically accelerated the identification of candidate materials with promising properties, a significant bottleneck remains: predicting which of these theoretically stable compounds can be successfully synthesized in a laboratory [5]. The synthesizability of a material is influenced by a complex array of factors beyond thermodynamic stability, including kinetic barriers, precursor availability, and chosen synthesis pathways [5] [22].

Traditional proxies for synthesizability, such as formation energy and energy above the convex hull (E(_{\text{hull}})), often prove insufficient, as numerous metastable structures are synthesizable, while many thermodynamically stable structures remain elusive [1] [5]. The charge-balancing heuristic, another common filter, also shows limited effectiveness, successfully classifying only about 37% of known synthesized materials [5]. This gap between computational prediction and experimental realization has driven the development of machine learning models capable of learning the complex, implicit rules of synthesizability directly from data on known materials.

SynthNN (Synthesizability Neural Network) is a deep learning model that addresses this challenge by predicting the synthesizability of inorganic crystalline materials based solely on their chemical composition [5] [23]. By reformulating materials discovery as a synthesizability classification task, SynthNN enables the efficient screening of hypothetical compounds, prioritizing those with the highest potential for experimental realization. This guide provides a comprehensive technical overview of the SynthNN framework, its methodology, performance, and place within the broader ecosystem of synthesizability prediction tools.

Core Methodology and Architecture

Problem Formulation and Data Curation

SynthNN is designed as a composition-based classification model. Its goal is to learn a function ( f(xc) ) that maps a chemical composition ( xc ) to a synthesizability probability ( p \in [0, 1] ), where a higher value indicates a greater likelihood that the material can be synthesized [5] [23].

Constructing a robust dataset for this task is challenging because, while data on successfully synthesized materials is available, definitive data on non-synthesizable materials is scarce, as failed syntheses are rarely reported. SynthNN addresses this through a Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning approach [5].

- Positive Examples: Sourced from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD), which contains experimentally synthesized and structurally characterized crystalline materials [5] [23].

- "Unlabeled" (Negative) Examples: Artificially generated hypothetical compounds that are treated as non-synthesizable for training purposes. This set is created by enumerating plausible but unsynthesized chemical formulas [5].

The model is trained to distinguish the distribution of synthesized compositions from the distribution of artificially generated ones, thereby learning the chemical "rules" and patterns that correlate with successful synthesis [5]. The final training dataset used in the original work contained a significantly larger number of unsynthesized examples, with a ratio of approximately 20:1 unsynthesized to synthesized compositions [23].

Model Architecture: The atom2vec Framework

SynthNN leverages a specialized atom2vec representation to convert chemical compositions into a format suitable for deep learning. This approach learns an optimal, dense representation of chemical elements directly from the data, rather than relying on pre-defined features or heuristic rules [5].

The core architecture of SynthNN is a deep neural network that processes this learned representation [5]. The key components are:

- Input Layer: The chemical formula is the input.

- Atom Embedding Layer: Each element in the periodic table is assigned a trainable embedding vector. The dimensionality of this vector is a key hyperparameter optimized during training.

- Composition Encoding: The embeddings of all atoms in the formula are aggregated to form a single, fixed-length descriptor for the entire composition.

- Deep Neural Network: The composition descriptor is passed through a series of fully connected (dense) layers with non-linear activation functions.

- Output Layer: A final layer with a sigmoid activation function outputs the synthesizability probability.

A critical feature of this architecture is that the atom embedding matrix and all other network parameters are optimized jointly during training. This allows the model to discover elemental properties and interactions that are most relevant to synthesizability without human bias [5].

Training Protocol and Hyperparameters

SynthNN was trained using a semi-supervised PU learning objective. The loss function was a modified binary cross-entropy that accounted for the probabilistic nature of the "unlabeled" examples, reweighting them according to their likelihood of being synthesizable [5]. The model was trained on a dataset extracted via the ICSD API [23]. Key hyperparameters, such as the atom embedding dimension, the number and size of hidden layers, and the learning rate, were tuned for optimal performance. The model was implemented and can be retrained using Jupyter notebooks provided in the official GitHub repository [23].

Performance Evaluation and Benchmarking

Quantitative Performance Metrics

SynthNN's performance was rigorously benchmarked against traditional synthesizability heuristics. The model demonstrated a superior ability to identify synthesizable materials compared to charge-balancing and random guessing baselines [5]. The table below summarizes the precision and recall of SynthNN at various classification thresholds on a dataset with a 20:1 ratio of unsynthesized to synthesized examples, as reported in the official repository [23].

Table 1: SynthNN Performance at Different Prediction Thresholds [23]

| Threshold | Precision | Recall |

|---|---|---|

| 0.10 | 0.239 | 0.859 |

| 0.20 | 0.337 | 0.783 |

| 0.30 | 0.419 | 0.721 |

| 0.40 | 0.491 | 0.658 |

| 0.50 | 0.563 | 0.604 |

| 0.60 | 0.628 | 0.545 |

| 0.70 | 0.702 | 0.483 |

| 0.80 | 0.765 | 0.404 |

| 0.90 | 0.851 | 0.294 |

The choice of threshold allows users to balance precision and recall based on their specific needs. For instance, a threshold of 0.50 yields a model where 56.3% of materials predicted as synthesizable are correct, and it successfully identifies 60.4% of all truly synthesizable materials [23].

In a head-to-head comparison against a team of 20 expert solid-state chemists tasked with identifying synthesizable materials, SynthNN outperformed all human experts, achieving 1.5 times higher precision and completing the task five orders of magnitude faster [5].

Comparison with Traditional and Alternative Methods

Table 2: Comparison of Synthesizability Prediction Methods

| Method | Core Basis | Key Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| SynthNN [5] [23] | Composition-based deep learning (PU Learning) | High precision vs. experts; fast screening; learns chemical principles from data. | No structural input; dependent on quality of training data. |

| Thermodynamic Stability (E(_{\text{hull}})) [1] [22] | DFT-calculated energy above convex hull | Strong physical basis; widely available. | Poor correlation with synthesizability; misses metastable phases. |

| Charge Balancing [5] | Net neutral ionic charge based on common oxidation states | Simple, interpretable, computationally cheap. | Low accuracy (≈37% on known materials); inflexible. |

| CSLLM (Crystal Synthesis LLM) [1] | Fine-tuned Large Language Models on text-based crystal representations | Predicts synthesizability, synthesis methods, and precursors (>90% accuracy); uses structural data. | Requires full crystal structure input; complex multi-model framework. |

| FTCP-based Model [22] | Deep learning on Fourier-transformed crystal properties | Uses structural information; achieved 82.6% precision on ternary crystals. | Requires full crystal structure input. |

Remarkably, without any explicit programming of chemical rules, SynthNN was found to have learned fundamental chemical principles such as charge-balancing, chemical family relationships, and ionicity, demonstrating that these patterns are inherently embedded in the distribution of known synthesized materials [5].

Table 3: Essential Resources for Composition-Based Synthesizability Prediction

| Resource | Function | Relevance to SynthNN |

|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [5] [23] | Provides a comprehensive collection of experimentally synthesized crystal structures. | Primary source of positive (synthesizable) training examples. |

| Materials Project (MP) Database [16] [22] | A large open-source database of DFT-calculated material properties and structures. | Source of theoretical structures; used for benchmarking and defining synthesizability labels. |

| Atom2Vec Representation [5] | A learned, dense vector representation for each chemical element. | Core feature extraction component of the SynthNN architecture. |

| Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning [5] | A semi-supervised machine learning paradigm for datasets with only positive and unlabeled examples. | Critical training methodology to handle the lack of confirmed negative samples. |

| Official SynthNN GitHub Repository [23] | Provides code for prediction, model retraining, and figure reproduction. | Essential for practical implementation and extension of the model. |

SynthNN in the Broader Research Landscape

The development of SynthNN represents a significant step in the transition from stability-based to data-driven synthesizability assessment. Its composition-only focus makes it uniquely useful for the early stages of materials discovery, where thousands of candidate compositions are screened before the computationally intensive step of structure prediction is undertaken.

However, the field is rapidly evolving. Recent work has expanded into structure-aware models. The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Model (CSLLM) framework, for example, uses fine-tuned LLMs on a text representation of crystal structures to achieve a state-of-the-art accuracy of 98.6% in synthesizability prediction, while also recommending synthetic methods and precursors with over 90% accuracy [1]. Other approaches, like the FTCP-based model, also leverage structural features to predict synthesizability with high precision [22].

Furthermore, the ultimate goal of computational materials discovery is not just prediction but also the generation of new, viable materials. Large-scale generative efforts like the Graph Networks for Materials Exploration (GNoME) project have discovered millions of new crystal structures [17] [24]. In this context, models like SynthNN and CSLLM serve as crucial filters to identify the most promising candidates from these vast generative outputs for experimental pursuit [16]. This integrated pipeline—generation, stability validation, and synthesizability filtering—significantly accelerates the entire materials discovery workflow, bridging the gap between theoretical prediction and experimental synthesis.

The discovery of new inorganic materials with targeted properties is a cornerstone for technological progress in fields such as energy storage, catalysis, and carbon capture [18]. Traditional materials discovery has historically relied on experimental trial-and-error or computational screening of known databases, methods that are often slow, costly, and fundamentally limited to a tiny fraction of possible stable compounds [18] [25]. While generative artificial intelligence (AI) presents a paradigm shift by directly proposing novel crystal structures, the ultimate challenge lies in predicting synthesizable materials—those that can be reliably realized in a laboratory. This whitepaper examines MatterGen, a novel diffusion model developed by Microsoft Research, which generates stable, diverse inorganic materials across the periodic table [18] [26]. We analyze its technical architecture, performance, and experimental validation, framing its capabilities within the critical, unresolved challenge of synthesizability prediction in deep learning research.

Technical Architecture of MatterGen

MatterGen is a diffusion model specifically engineered for the inverse design of crystalline materials. Its architecture accounts for the unique symmetries and periodicity of crystal structures, moving beyond simple adaptations of image-based diffusion processes [18] [27].

Tailored Diffusion Process for Crystalline Materials

A crystalline material is defined by its unit cell, comprising atom types (A), fractional coordinates (X), and a periodic lattice (L). MatterGen employs a customized corruption process for each component with physically motivated limiting noise distributions [18]:

- Atom Types: Diffused in categorical space, where individual atoms are corrupted into a masked state [18].

- Fractional Coordinates: A wrapped Normal distribution respects periodic boundary conditions, approaching a uniform distribution at the noisy limit [18].

- Periodic Lattice: The diffusion process is symmetric and approaches a distribution whose mean is a cubic lattice with an average atomic density derived from training data [18].

To reverse this corruption, a learned score network outputs invariant scores for atom types and equivariant scores for coordinates and the lattice, inherently respecting the necessary symmetries without needing to learn them from data [18]. The model is built upon the GemNet architecture, which is well-suited for modeling complex atomic interactions [26].

Conditional Generation via Adapter Modules

A pivotal feature of MatterGen is its capacity for property-conditioned generation. This is achieved through a two-stage training and fine-tuning process [18] [28]:

- Pretraining: A base model is trained on a large, diverse dataset of stable inorganic crystals (Alex-MP-20, containing ~607,683 structures) to generate stable and diverse materials unconditionally [18] [26].

- Fine-tuning: For conditional generation, small "adapter modules" are injected into the layers of the pretrained base model. These tunable components alter the model's output based on a given property label. This approach is highly efficient, as it requires only a small labeled dataset for fine-tuning, which is crucial for properties with expensive computational or experimental labels [18]. During inference, the fine-tuned model is used with classifier-free guidance to steer the generation towards the user-specified property constraints [18] [29].

The following diagram illustrates the complete generation workflow, from the initial noise to a conditioned, stable crystal.

Performance and Quantitative Evaluation

MatterGen's performance has been rigorously benchmarked against both traditional discovery methods and prior generative AI models, demonstrating significant advancements in the quality and utility of generated materials.

Key Performance Metrics

Stability, novelty, and structural quality are the primary metrics for evaluating generative materials models. MatterGen was evaluated by generating structures and subsequently relaxing them using Density Functional Theory (DFT), the computational gold standard [18].

Table 1: Stability and Quality of Unconditionally Generated Structures (1,024 samples)

| Metric | Definition | MatterGen Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Stability (MP hull) | Energy < 0.1 eV/atom above convex hull | 78% of structures [18] |

| Low Energy | Energy below convex hull | 13% of structures [18] |

| Structural Quality | Avg. RMSD to DFT-relaxed structure | 0.021 Ã… (very close to local minimum) [26] |

| Novelty | Not found in reference dataset (Alex-MP-ICSD) | 61% of structures were novel [18] |

Table 2: Comparative Benchmark Against Prior Generative Models

| Model | Stable, Unique & Novel (SUN) Rate | Average RMSD to DFT Relaxation (Ã…) |

|---|---|---|

| MatterGen | 38.57% [26] | 0.021 [26] |

| CDVAE | ~15% (estimated from Fig. 2e [18]) | ~0.3 (estimated from Fig. 2f [18]) |

| DiffCSP | ~15% (estimated from Fig. 2e [18]) | ~0.3 (estimated from Fig. 2f [18]) |

MatterGen more than doubles the success rate for generating viable new materials and produces structures that are more than ten times closer to their DFT-relaxed ground state compared to previous state-of-the-art models [18].

Capabilities in Property-Conditioned Generation

After fine-tuning on specific property labels, MatterGen can perform targeted inverse design. The following table summarizes its performance on several key conditioning tasks.

Table 3: Performance on Property-Conditioned Generation Tasks

| Condition Type | Target | Generation Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical System | Well-explored systems | 83% SUN structures [26] |

| Unexplored systems | 49% SUN structures [26] | |

| Bulk Modulus | 400 GPa | 106 SUN structures obtained within a budget of 180 DFT calculations [26] |

| Magnetic Density | > 0.2 Ã…â»Â³ | 18 SUN structures complying with the condition within a budget of 180 DFT calculations [26] |

Experimental Validation and Synthesis

A critical step in validating any computational materials design model is the successful synthesis and experimental measurement of a proposed structure.

Protocol for Experimental Proof-of-Concept

As reported in the foundational Nature paper, the researchers followed a comprehensive workflow to validate MatterGen [18] [28]:

- Generation & Filtering: MatterGen generated over 8,000 candidate materials with a target bulk modulus of 200 GPa.

- Automated Screening: Candidates were automatically filtered to remove structures present in the training dataset and those predicted to be unstable.

- Manual Selection: From the remaining shortlist, four candidate structures were selected manually for further investigation.

- Synthesis & Measurement: One of these candidates was successfully synthesized in the lab. Its bulk modulus was experimentally measured to be 158 GPa.

This result, which was within 20% of the original 200 GPa target, provides critical proof-of-concept that MatterGen can design materials with real-world property values [18] [28]. The measured value differs from the target primarily because the model was conditioned on DFT-calculated properties, which can have systematic deviations from experimental values.

The Synthesis Bottleneck and Future Directions

Despite its impressive capabilities, the journey from a computationally designed material to a synthesized product remains the primary bottleneck in materials discovery [25].

The Synthesis Challenge

A fundamental limitation of current generative models, including MatterGen, is that they are primarily optimized for thermodynamic stability. However, synthesizability is a kinetic and pathway-dependent problem [25]. A material may be thermodynamically stable but impossible to synthesize because all potential reaction pathways lead to unwanted byproducts, or the necessary conditions are impractical [25]. For instance, promising materials like the multiferroic BiFeO₃ and the solid electrolyte LLZO are notoriously difficult to synthesize without impurities, despite their thermodynamic stability [25].

The Path Forward: Integrating Synthesis Prediction

Bridging the gap between stability and synthesizability requires a new class of models and data. The research community is actively exploring several approaches, one of which is an active learning framework that integrates crystal generation with iterative screening.

This framework, as explored in concurrent research, uses a loop where a generative model proposes candidates, which are then filtered through high-throughput screening (often using foundation atomic models or DFT). The validated data is fed back into the training set, progressively improving the model's accuracy, especially for extreme property targets [29]. The ultimate goal is to incorporate synthesis pathway predictors into this loop. However, this is currently hampered by a severe lack of large-scale, standardized data on both successful and failed synthesis attempts [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit

The development and application of MatterGen rely on a suite of computational and experimental resources that form the essential toolkit for modern, AI-driven materials science.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Item / Resource | Type | Function in the Discovery Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| MatterGen Model | Software | Core generative engine for proposing novel, stable crystal structures conditioned on properties [26]. |

| Materials Project (MP) | Database | Primary source of training data; provides DFT-calculated structures and properties for known materials [18] [26]. |

| Alexandria Database | Database | Source of hypothetical crystal structures, expanding the diversity and novelty of training data [18] [26]. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Computational Method | Used for training data generation, property labeling, and final validation of generated structures' stability and properties [18]. |

| Foundation Atomic Models (FAMs) | Software (e.g., MACE-MP-0) | Machine learning force fields used for fast, high-throughput property prediction and screening of generated candidates [29]. |

| Disordered Structure Matcher | Algorithm | Used to determine the novelty of a generated structure by matching it against known ordered and disordered structures in databases [18]. |

| High-Throughput Synthesis | Experimental Method | For physically validating AI-generated candidates and generating critical data on synthesis pathways and conditions [25]. |

| Dioleoylphosphatidylglycerol | Dioleoylphosphatidylglycerol, MF:C42H79O10P, MW:775 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 4-Butyl-alpha-agarofuran | 4-Butyl-alpha-agarofuran, MF:C18H30O, MW:262.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

MatterGen represents a paradigm shift in computational materials design, moving the field from database screening to active, property-driven generation of novel inorganic crystals [30]. Its tailored diffusion architecture and adapter-based fine-tuning framework enable it to generate stable, diverse materials with a higher success rate and greater structural fidelity than any prior model [18]. The experimental synthesis of one of its proposed materials confirms its potential for real-world impact [18]. Nonetheless, the broader thesis on predicting synthesizability reveals that the hardest step remains: navigating the complex kinetic landscape of chemical synthesis to reliably produce designed materials in the lab [25]. The future of the field lies in integrating powerful generators like MatterGen with active learning loops and emerging models for synthesis planning, ultimately creating a closed-loop AI system that encompasses not just design, but also the pathway to creation.

The discovery of new functional inorganic materials is a cornerstone for advancing technologies in energy storage, electronics, and catalysis. While computational models, particularly density functional theory (DFT), have successfully identified millions of candidate structures with promising properties, a significant bottleneck remains: predicting which of these theoretical structures can be successfully synthesized in a laboratory [1]. Traditional screening methods based on thermodynamic stability (e.g., energy above the convex hull) or kinetic stability (e.g., phonon spectra analyses) show limited accuracy, as they often overlook the complex, multi-faceted nature of real-world synthesis, which is influenced by precursor choice, reaction pathways, and experimental conditions [1] [16]. This gap between computational prediction and experimental realization presents a major challenge in materials discovery.

Recent advances in artificial intelligence, specifically large language models (LLMs), offer a transformative approach to this problem. LLMs, with their extensive architectures and ability to learn from vast datasets, have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in various scientific domains. The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Models (CSLLM) framework represents a groundbreaking application of this technology, utilizing specialized LLMs to accurately predict synthesizability, suggest synthetic methods, and identify suitable precursors for inorganic crystal structures [1]. This technical guide details the architecture, methodology, and experimental validation of the CSLLM framework, positioning it as a powerful tool for bridging the gap between theoretical materials design and practical synthesis.

The CSLLM Framework: Architecture and Core Components

The CSLLM framework is built upon a multi-model architecture designed to address the distinct challenges of predicting synthesis. It comprises three specialized LLMs, each fine-tuned for a specific task, working in concert to provide a comprehensive synthesis planning tool [1].

- Synthesizability LLM: This model predicts whether a given 3D crystal structure is synthesizable. It serves as the primary filter, identifying candidate structures worthy of further experimental investigation.

- Method LLM: For a structure deemed synthesizable, this model classifies the most probable synthetic pathway, such as solid-state reaction or solution-based methods [1].

- Precursor LLM: This model identifies specific chemical precursors suitable for the synthesis of the target material, a critical step for experimental planning [1].

A key innovation enabling the use of LLMs for this domain-specific task is the development of a novel text representation for crystal structures, termed the "material string" [1]. Traditional formats like CIF or POSCAR contain redundant information or lack symmetry data. The material string overcomes these limitations by providing a concise, reversible text format that integrates essential crystal information: space group, lattice parameters, and a compact representation of atomic sites using Wyckoff positions [1]. This efficient encoding allows the LLMs to process complex structural information effectively during fine-tuning.

Table 1: Core Components of the CSLLM Framework

| Component | Primary Function | Input | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synthesizability LLM | Predicts synthesizability of a crystal structure | Material String | Synthesizable / Non-Synthesizable |

| Method LLM | Recommends a synthetic route | Material String | Solid-State / Solution Method |

| Precursor LLM | Identifies suitable chemical precursors | Material String | List of Precursor Compounds |

Diagram 1: CSLLM Workflow. The diagram illustrates the sequential decision-making process of the CSLLM framework, from structural input to synthesis recommendations.

Dataset Construction and Curation

A model is only as robust as the data it is trained on. The development of CSLLM relied on the construction of a comprehensive, balanced dataset of synthesizable and non-synthesizable crystal structures [1].

- Positive Samples (Synthesizable): 70,120 experimentally confirmed synthesizable crystal structures were meticulously curated from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD). The selection criteria included structures with a maximum of 40 atoms per unit cell and no more than seven distinct elements. Disordered structures were excluded to maintain a focus on ordered crystals [1].

- Negative Samples (Non-Synthesizable): Generating reliable negative samples is a known challenge. The CSLLM team employed a pre-trained Positive-Unlabeled (PU) learning model to screen a vast pool of 1,401,562 theoretical structures from databases like the Materials Project and OQMD [1]. This model assigns a "CLscore," where a lower score indicates a higher likelihood of being non-synthesizable. The 80,000 structures with the lowest CLscores (CLscore < 0.1) were selected as negative examples, creating a balanced dataset of 150,120 structures [1].

This final dataset encompasses all seven crystal systems and elements with atomic numbers 1-94 (excluding 85 and 87), ensuring broad chemical and structural diversity [1].

Experimental Protocols and Model Training