Autonomous Reaction Route Optimization: Accelerating Solid-State Synthesis for Advanced Materials and Drug Development

This article explores the paradigm shift in inorganic materials synthesis driven by autonomous laboratories and intelligent optimization algorithms.

Autonomous Reaction Route Optimization: Accelerating Solid-State Synthesis for Advanced Materials and Drug Development

Abstract

This article explores the paradigm shift in inorganic materials synthesis driven by autonomous laboratories and intelligent optimization algorithms. Focusing on the core methodology of Autonomous Reaction Route Optimization with Solid-State Synthesis (ARROWS3), we examine its foundational principles that integrate thermodynamics, machine learning, and robotic experimentation. The content details its application in successfully synthesizing novel and metastable materials, including pharmaceuticals and battery components, by dynamically selecting precursors to avoid kinetic traps. A comparative analysis validates its superior performance against traditional black-box optimization, requiring fewer experimental iterations. Finally, we discuss the transformative implications of these self-driving labs for accelerating drug development and advanced material discovery, addressing current challenges and future directions for the field.

The New Paradigm: Foundations of Autonomous Optimization in Solid-State Chemistry

The Limitations of Traditional One-Variable-at-a-Time Synthesis

The One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) method represents a classical approach to experimental design that has been widely employed across chemical synthesis, materials science, and pharmaceutical development. This methodology involves systematically varying a single experimental factor while maintaining all other parameters constant at fixed baseline levels [1]. The historical popularity of OFAT emerged from its intuitive simplicity and straightforward implementation, requiring minimal statistical expertise for initial adoption [1] [2]. Researchers could easily isolate the effect of individual variables without employing complex experimental designs or advanced analytical techniques, making it particularly valuable during early stages of scientific investigation when preliminary insights were prioritized over comprehensive optimization [1].

In traditional synthetic chemistry, OFAT has been extensively applied to reaction optimization, where parameters such as temperature, catalyst concentration, solvent composition, and reaction time are sequentially adjusted to improve yield or purity [3]. The method follows a sequential pathway: after selecting baseline conditions for all factors, the investigator varies one factor across different levels while holding others constant, observes the response, returns the adjusted factor to its baseline, then proceeds to investigate the next factor [1]. This cyclic process continues until all factors of interest have been individually examined, with the optimal conditions theoretically representing the combination of each factor's best-performing level [1].

Key Limitations of the OFAT Approach

Inability to Detect Interaction Effects

The most significant limitation of OFAT methodology lies in its fundamental inability to detect or quantify interaction effects between experimental factors [1] [2]. OFAT operates on the implicit assumption that factors act independently on the response variable, an assumption that frequently fails in complex chemical and biological systems where synergistic or antagonistic relationships between parameters commonly occur [1]. For example, in pharmaceutical synthesis, the relationship between temperature and catalyst concentration is often non-additive, where the optimal temperature range may shift dramatically depending on catalyst loading [1]. Without the capability to vary factors simultaneously, OFAT cannot capture these critical interactions, potentially leading researchers to suboptimal conditions and incomplete understanding of the underlying reaction dynamics [1].

Resource Inefficiency and Experimental Burden

OFAT methodologies typically require substantially more experimental runs to achieve the same precision in effect estimation compared with modern statistical design approaches [2]. This inefficiency stems from the fundamental limitation that OFAT fails to extract maximal information from each experimental trial, instead focusing on one-dimensional slices through a multidimensional experimental space [1]. For synthetic optimization problems involving numerous factors, the number of required experiments grows rapidly, consuming significant time, material resources, and analytical capacity [1]. In pharmaceutical development where novel compounds may be available in limited quantities or require complex multi-step synthesis, this resource burden can substantially impede research progress and increase development costs [4].

Limited Optimization Capabilities

The OFAT approach provides no systematic framework for true response optimization [1]. While the method can identify improved conditions for individual factors, it cannot reliably locate global optima in complex response surfaces, particularly when factor interactions are present [1]. This limitation becomes critical in synthetic chemistry where researchers aim to simultaneously maximize multiple outcomes such as yield, purity, and selectivity while minimizing cost and environmental impact [3]. The sequential nature of OFAT often leads to convergence on local optima rather than identification of the best possible combination of factors, potentially missing superior conditions that could significantly enhance process efficiency or product quality [1] [2].

By failing to account for factor interactions and exploring only a limited trajectory through the experimental space, OFAT carries an elevated risk of generating misleading or incomplete conclusions [1]. The identified "optimal" conditions may appear satisfactory within the narrow experimental pathway investigated but could be substantially inferior to unexplored regions of the parameter space [1]. Furthermore, when interaction effects are present but undetected, the individual factor effects estimated by OFAT may be inaccurate or misrepresent their true impact on the system [2]. This can lead to fragile processes highly sensitive to minor variations in uncontrolled factors and poor reproducibility across different synthetic batches or scales [1].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of OFAT versus Modern Experimental Design Approaches

| Characteristic | OFAT Approach | Modern DOE Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Ability to Detect Interactions | None | Comprehensive |

| Experimental Runs Required (for 5 factors, 3 levels) | 121+ | 25-50 |

| Optimization Capability | Local optima | Global optima |

| Region of Exploration | Limited trajectory | Comprehensive space |

| Statistical Efficiency | Low | High |

| Resource Consumption | High | Moderate |

Modern Alternatives: Design of Experiments and Autonomous Optimization

Design of Experiments (DOE) Fundamentals

Design of Experiments (DOE) represents a statistically rigorous alternative to OFAT that enables simultaneous investigation of multiple factors and their interactions [1]. Founded on three core principles—randomization, replication, and blocking—DOE provides a structured framework for efficient experimental planning, execution, and analysis [1]. Randomization ensures experimental runs are conducted in random sequence to minimize the impact of confounding variables and systematic biases [1]. Replication involves repeating experimental trials under identical conditions to estimate experimental error and enhance the precision of effect estimation [1]. Blocking techniques account for known sources of variability (e.g., different equipment, operators, or material batches) by grouping homogeneous experimental units, thereby improving the sensitivity for detecting significant factor effects [1].

Factorial designs represent a foundational DOE approach wherein factors are varied simultaneously rather than sequentially [1]. In a full factorial design, all possible combinations of factor levels are investigated, enabling comprehensive estimation of both main effects and interaction effects [1]. For synthetic optimization problems with numerous factors, fractional factorial designs can efficiently screen for significant effects using a subset of the full factorial combinations while preserving the ability to detect important interactions [1]. The statistical analysis of DOE typically employs Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to partition total variability into components attributable to main effects, interaction effects, and experimental error, facilitating rigorous hypothesis testing about factor significance [1].

Response Surface Methodology for Synthesis Optimization

Response Surface Methodology (RSM) extends basic factorial designs to model and optimize synthetic processes using empirical mathematical models [1]. When process optimization requires understanding of curvature in the response surface rather than just linear effects, RSM provides powerful tools for locating optimal conditions [1]. Central Composite Designs (CCD) and Box-Behnken Designs represent two widely employed RSM approaches that efficiently estimate quadratic response surfaces while requiring fewer experimental runs than full three-level factorial arrangements [1]. These methodologies enable researchers to model complex nonlinear relationships between synthetic parameters and outcomes, identify stationary points (maxima, minima, or saddle points), and characterize the functional landscape around optimal conditions to establish robust operational ranges [1].

Autonomous Reaction Route Optimization

Recent advances in autonomous experimentation systems have begun to transform synthetic optimization paradigms, particularly for solid-state materials synthesis [5] [6]. The ARROWS3 (Autonomous Reaction Route Optimization with Solid-State Synthesis) algorithm exemplifies this next-generation approach by integrating computational thermodynamics with experimental feedback to dynamically guide precursor selection and reaction planning [5]. This methodology addresses a fundamental challenge in solid-state synthesis: the formation of stable intermediate phases that consume thermodynamic driving force and prevent target material formation [5].

ARROWS3 employs an active learning framework that begins with precursor ranking based on calculated thermodynamic driving force (ΔG) to form the target material [5]. After experimental testing across multiple temperatures, the algorithm analyzes formed intermediates using X-ray diffraction with machine-learned analysis [5]. By identifying which pairwise reactions lead to undesirable intermediates, the system updates its precursor ranking to favor combinations that maintain maximal driving force at the target-forming step (ΔG′) [5]. This iterative process continues until the target is successfully synthesized with sufficient yield or all precursor options are exhausted [5].

The A-Lab represents a comprehensive implementation of autonomous materials synthesis, integrating robotics with computational thermodynamics, machine learning-driven data interpretation, and active learning [6]. In a landmark demonstration, this system successfully synthesized 41 of 58 novel target compounds over 17 days of continuous operation by leveraging historical literature data, ab initio computations, and real-time experimental feedback [6]. The laboratory's autonomous decision-making enabled it to propose and execute synthesis recipes, characterize products, and iteratively refine synthetic approaches based on experimental outcomes [6].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Optimization Approaches in Materials Synthesis

| Optimization Method | Success Rate | Experimental Iterations Required | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional OFAT | Variable | High | Sequential testing, no interaction detection |

| Bayesian Optimization | Moderate | Moderate | Black-box optimization, handles continuous variables |

| Genetic Algorithms | Moderate | Moderate | Population-based search, inspired by evolution |

| ARROWS3 Algorithm | High | Lower | Incorporates domain knowledge, avoids stable intermediates |

| Full Autonomous A-Lab | 71-78% | Minimal after setup | Complete integration of computation, robotics, and ML |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Traditional OFAT Optimization for Chemical Synthesis

Purpose: To systematically optimize reaction yield using One-Factor-at-a-Time approach.

Materials and Equipment:

- Reaction substrates and reagents

- Solvent selection suite

- Temperature-controlled reaction stations

- Analytical instrumentation (HPLC, GC-MS, NMR)

- Catalyst compounds

Procedure:

- Establish baseline conditions: Select starting values for all reaction parameters (temperature, catalyst concentration, solvent ratio, mixing speed, reaction time).

- Fix all but one factor: Maintain all parameters at baseline except the first factor to be investigated.

- Vary first factor: Systematically test different levels of the first factor while holding others constant.

- Analyze responses: Measure outcome variables (yield, purity, selectivity) for each level.

- Return to baseline: Reset the varied factor to its original level before proceeding.

- Iterate through factors: Repeat steps 2-5 for each additional factor.

- Combine results: Select the optimal level for each factor based on individual performances.

Data Analysis:

- Plot individual factor effects against response variables

- Identify apparent optimal level for each factor

- Implement the combination of individually optimal levels as the "optimized" protocol

Limitations Note: This approach cannot detect factor interactions and may miss globally optimal conditions [1] [2].

Protocol: Autonomous Optimization with ARROWS3 Framework

Purpose: To implement active learning for solid-state synthesis route optimization.

Materials and Equipment:

- Powder precursor libraries

- Automated weighing and dispensing system

- Robotic milling and mixing apparatus

- High-temperature furnaces with atmospheric control

- X-ray diffractometer with automated sample handling

- Computational infrastructure for DFT calculations

- Machine learning models for phase analysis

Procedure:

- Target specification: Input desired material composition and crystal structure.

- Precursor selection: Generate stoichiometrically balanced precursor sets from available compounds.

- Initial ranking: Calculate thermodynamic driving force (ΔG) for target formation using DFT-derived formation energies.

- Experimental testing:

- Automatically dispense and mix precursor powders

- Heat samples across temperature gradient (typically 4-5 temperatures)

- Cool and prepare samples for characterization

- Acquire XRD patterns and analyze using machine learning models

- Pathway analysis: Identify intermediate phases and reconstruct pairwise reaction pathways.

- Driving force calculation: Compute remaining thermodynamic driving force (ΔG′) after intermediate formation.

- Active learning: Update precursor ranking to maximize ΔG′ and avoid kinetic traps.

- Iterative refinement: Repeat steps 4-7 until target forms with >50% yield or resources exhausted.

Validation:

- Compare predicted and experimental reaction pathways

- Assess target phase purity by Rietveld refinement

- Confirm reproducibility through replicate experiments

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Autonomous Synthesis Optimization

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Diverse Precursor Libraries | Provide elemental composition for target materials | Chemical diversity enables alternative reaction pathways |

| Stoichiometric Calculators | Ensure proper elemental ratios | Automated balancing critical for high-throughput workflows |

| Thermodynamic Databases | Predict reaction energies and driving forces | Materials Project data enables initial precursor ranking [5] [6] |

| XRD Reference Patterns | Identify crystalline phases in products | Experimental and computed patterns required for novel materials |

| Machine Learning Phase Identifiers | Automate analysis of diffraction data | Enables rapid experimental feedback [5] [6] |

| Ab Initio Computation Resources | Calculate formation energies | Essential for predicting thermodynamic driving forces [5] |

Workflow Visualization

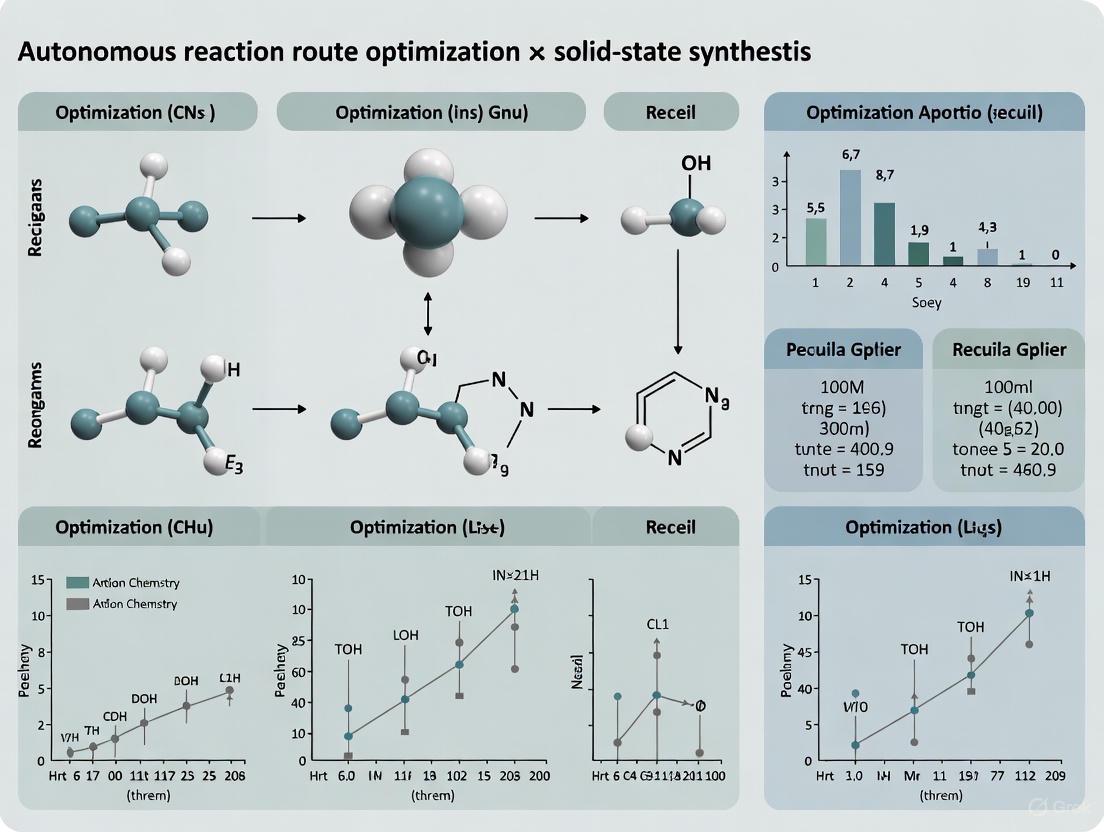

Autonomous Synthesis Workflow: This diagram illustrates the iterative active learning process implemented in systems like ARROWS3 and A-Lab, where experimental outcomes continuously inform and refine computational models to accelerate materials synthesis optimization [5] [6].

Autonomous laboratories, or self-driving labs, represent a transformative paradigm in scientific research, particularly for accelerating the discovery and synthesis of novel materials and molecules. These systems function as a continuous closed-loop cycle, seamlessly integrating artificial intelligence (AI), robotic experimentation systems, and automation technologies to execute scientific experiments with minimal human intervention [7]. In the specific context of solid-state synthesis, this approach minimizes downtime between manual operations, eliminates subjective decision points, and enables the rapid exploration of novel materials and optimization strategies that would traditionally require months of trial and error [7] [8]. The core value proposition lies in turning these slow, labor-intensive processes into routine high-throughput workflows, thereby dramatically accelerating the pace of scientific innovation.

Core Components and Their Functions

The effectiveness of an autonomous laboratory hinges on the tight integration of its three core technological pillars. The table below summarizes the primary function of each component within the closed-loop system for autonomous reaction route optimization.

Table 1: Core Components of an Autonomous Laboratory for Solid-State Synthesis

| Component | Primary Function | Key Technologies & Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Artificial Intelligence (AI) | Plans experiments, designs synthesis recipes, analyzes characterization data, and proposes optimized routes. | Machine Learning (ML), Active Learning (e.g., ARROWS3), Bayesian Optimization, Natural Language Processing (NLP) for literature mining, Large Language Models (LLMs) [7] [8]. |

| Robotics | Automates the physical execution of synthesis and characterization, including handling, dispensing, heating, and grinding. | Robotic Arms, Automated Powder Dispensing Systems, Box Furnaces, X-ray Diffraction (XRD) Sample Handling [8]. |

| Active Learning | Closes the loop by using experimental outcomes to inform and improve subsequent experiments. | Autonomous Reaction Route Optimization with Solid-State Synthesis (ARROWS3), Bayesian Optimization driven by thermodynamic data and observed reaction pathways [8]. |

Detailed Functionality of AI

AI serves as the "brain" of the autonomous laboratory, making critical decisions at multiple stages. Initially, AI models, including those trained on vast literature databases via natural language processing, generate plausible synthesis recipes and suggest reaction temperatures [8]. Following robotic execution, AI is again critical for data interpretation. For instance, machine learning models, such as convolutional neural networks, are used to identify phases and estimate their weight fractions from X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns [7] [8]. Furthermore, active learning algorithms like ARROWS3 use the experimental results—both successes and failures—to propose improved synthesis routes. This algorithm integrates ab initio computed reaction energies with observed synthesis outcomes, often prioritizing reaction pathways that avoid intermediates with a low driving force to form the final target material [8].

Detailed Functionality of Robotics

The robotics system acts as the "hands" of the lab, physically carrying out the plans devised by the AI. A representative setup, as seen in the A-Lab, involves multiple integrated stations [8]:

- Sample Preparation Station: Dispenses and mixes precursor powders before transferring them into crucibles.

- Heating Station: Features robotic arms that load crucibles into box furnaces for controlled heating.

- Characterization Station: Grinds synthesized samples into fine powders and prepares them for automated XRD measurement. This robotic integration enables 24/7 operation and ensures consistent, reproducible handling of solid-state powders, which can have diverse and challenging physical properties [8].

The Active Learning Workflow

Active learning is the adaptive process that closes the loop between AI and robotics. It doesn't just collect data; it uses it to make smarter decisions for the next experiment. The ARROWS3 algorithm, for example, leverages two key hypotheses: first, that solid-state reactions often proceed through pairwise interactions between phases, and second, that intermediates with a small driving force to form the target should be avoided [8]. As the lab conducts experiments, it builds a database of observed pairwise reactions. This knowledge allows it to eliminate redundant experiments and strategically search for synthesis routes with more favorable thermodynamics and kinetics.

Experimental Protocol: Autonomous Synthesis of Novel Inorganic Materials

This protocol details the specific methodology employed by the A-Lab for the solid-state synthesis of novel inorganic powders, as documented in Nature [8].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Autonomous Solid-State Synthesis

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Precursor Powders | Starting materials containing the necessary elements for the target compound. The selection is guided by AI models trained on literature data and thermodynamic stability [8]. |

| Alumina Crucibles | Containers for holding powder mixtures during high-temperature reactions in box furnaces. They are inert to most inorganic precursors at high temperatures [8]. |

| X-ray Diffraction (XRD) System | Primary characterization tool for identifying crystalline phases present in the synthesis product. It is essential for quantifying yield and informing the active learning cycle [8]. |

| Ab Initio Thermodynamic Data | Computed data from sources like the Materials Project. Used to assess target stability and calculate the driving force for reactions, which is a key input for the active learning algorithm [8]. |

Step-by-Step Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the continuous closed-loop workflow of an autonomous laboratory.

Figure 1: Autonomous Laboratory Closed-Loop Workflow. This diagram outlines the continuous cycle of planning, execution, analysis, and learning that enables autonomous materials discovery.

- Target Identification and Validation: The process begins with a set of target materials identified through large-scale ab initio computations (e.g., from the Materials Project or Google DeepMind). Targets are screened for predicted phase stability and air stability to ensure they are viable for synthesis in an open-air environment [8].

- AI-Driven Synthesis Planning:

- Recipe Generation: For a given target, up to five initial synthesis recipes are generated using a machine learning model. This model uses natural-language processing on a vast database of historical synthesis literature to assess "target similarity" and propose precursors and methods by analogy to known materials [8].

- Temperature Selection: A separate ML model, trained on heating data from the literature, proposes an initial synthesis temperature [8].

- Robotic Execution of Synthesis:

- Sample Preparation: Precursor powders are automatically dispensed and mixed by a robotic system at the preparation station. The mixture is transferred into an alumina crucible [8].

- Heating: A robotic arm loads the crucible into one of four box furnaces for heating according to the AI-proposed temperature profile [8].

- Cooling and Grinding: After heating, the sample is allowed to cool. Another robotic arm then transfers the sample to a station where it is ground into a fine, homogeneous powder to ensure high-quality XRD data [8].

- Automated Characterization and Analysis:

- XRD Measurement: The ground powder is automatically prepared and measured by an X-ray diffractometer [8].

- Phase Identification: The XRD pattern is analyzed by probabilistic ML models trained on experimental structures to identify crystalline phases and estimate their weight fractions. The identity and yield of the target phase are confirmed via automated Rietveld refinement [8].

- Active Learning and Optimization:

- The analyzed yield (a quantitative measure of synthesis success) is reported to the lab's management server.

- Success Criterion: If the target yield exceeds 50%, the experiment is considered a success, and the recipe is logged [8].

- Failure and Optimization: If the yield is below 50%, the active learning algorithm (ARROWS3) is engaged. This algorithm uses the observed reaction products and ab initio thermodynamic data to propose a modified synthesis recipe (e.g., different precursors or a modified temperature), which is then automatically fed back into the workflow for a new iteration [8].

Performance Data and Outcomes

The efficacy of this integrated approach is demonstrated by the real-world performance of the A-Lab. Over 17 days of continuous operation, the platform successfully synthesized 41 out of 58 targeted novel inorganic compounds, achieving a 71% success rate [8]. Further analysis suggested this rate could be improved to 78% with minor enhancements to both decision-making algorithms and computational screening techniques [8].

Table 3: Quantitative Performance of an Autonomous Laboratory (A-Lab)

| Metric | Outcome | Details / Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Operation Duration | 17 days | Continuous, minimal human intervention [8]. |

| Targets Attempted | 58 | Novel, computationally predicted inorganic materials (oxides, phosphates) [8]. |

| Successfully Synthesized | 41 compounds | Resulting in a 71% success rate [8]. |

| Initial Recipe Success | 35 compounds | Synthesized using initial literature-inspired AI proposals [8]. |

| Active Learning Success | 6 compounds | Synthesized only after optimization via the active learning loop (ARROWS3) [8]. |

| Potential Success Rate | Up to 78% | Estimated with improved computational techniques and decision algorithms [8]. |

The active learning component proved critical for targets that failed initial synthesis attempts. In one documented case, the synthesis of CaFe2P2O9 was optimized by using active learning to avoid a low-driving-force intermediate, leading to an alternative pathway and a ~70% increase in target yield [8]. This highlights the system's capability to not only execute experiments but to learn and innovate from its own results.

The selection of precursors and the prediction of reaction pathways in solid-state synthesis have long relied on empirical knowledge and extensive trial-and-error experimentation. The development of autonomous research platforms necessitates a fundamental and computable understanding of the principles governing solid-state reactions. Two such critical principles are the thermodynamic driving force and pairwise reaction analysis. The thermodynamic driving force, typically represented by the change in Gibbs free energy (∆G), dictates the inherent tendency of a reaction to occur [5] [9]. Pairwise reaction analysis provides a simplified framework for deconstructing complex solid-state reaction pathways into a series of step-by-step transformations between two phases at a time, making the analysis of intricate synthesis routes tractable [5] [10]. Together, these concepts form the cornerstone of modern, computational approaches to predicting and optimizing solid-state synthesis, enabling algorithms to autonomously navigate the complex energy landscape of materials formation.

Quantitative Frameworks and thresholds

The practical application of thermodynamics requires moving beyond qualitative principles to established quantitative thresholds. Research has validated that the initial phase formed in a solid-state reaction can be predicted by thermodynamic calculations alone when its driving force exceeds that of all other competing phases by a specific energy margin.

Table 1: Threshold for Thermodynamic Control in Solid-State Reactions

| Concept | Quantitative Threshold | Experimental Validation | Implication for Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Threshold for Thermodynamic Control | ≥60 meV/atom [9] | In-situ XRD on 37 reactant pairs [9] | The initial reaction product is predictable when its ∆G is ≥60 meV/atom more negative than competing phases. |

| Regime of Kinetic Control | ∆G difference <60 meV/atom [9] | In-situ XRD on 37 reactant pairs [9] | Reaction outcome is influenced by kinetic factors; max-∆G theory is less reliable. |

This 60 meV/atom threshold defines the regime of thermodynamic control. In this regime, the "max-∆G theory" applies, stating that the initial product formed between two reactants will be the one that leads to the largest decrease in Gibbs energy per atom, irrespective of the overall reactant stoichiometry [9]. This is justified by the localized nature of product formation at particle interfaces. Outside this threshold, in the regime of kinetic control, factors such as diffusion limitations and structural templating become decisive, and explicit modeling of these kinetics is required for accurate prediction [9].

Autonomous Optimization via the ARROWS3 Algorithm

The ARROWS3 (Autonomous Reaction Route Optimization with Solid-State Synthesis) algorithm operationalizes these concepts into a closed-loop workflow for autonomous precursor selection [5] [11]. It leverages thermodynamic data and pairwise reaction analysis to actively learn from experimental outcomes and iteratively propose improved synthesis routes.

Figure 1: ARROWS3 Autonomous Optimization Workflow

As illustrated in Figure 1, the ARROWS3 process begins by ranking all possible precursor combinations based on their calculated thermodynamic driving force (∆G) to form the target material [5] [11]. The highest-ranked precursors are then experimentally tested across a range of temperatures. When an experiment fails, X-ray diffraction (XRD) with machine-learned analysis is used to identify the intermediate phases that formed [5]. The algorithm then performs pairwise reaction analysis to determine which specific reactions between precursors or early intermediates led to the formation of these stable byproducts [5]. This knowledge is generalized to predict which other precursor sets in the search space are likely to form the same problematic intermediates. For subsequent iterations, ARROWS3 prioritizes precursor sets predicted to avoid these intermediates, thereby retaining a larger thermodynamic driving force (∆G') for the critical target-forming step [5] [11]. This closed-loop of execution, characterization, and learning allows ARROWS3 to identify effective recipes with fewer experiments than black-box optimization methods [5].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: In Situ XRD for Determining First Reaction Products

Objective: To empirically determine the first crystalline product formed in a solid-state reaction and validate computational predictions based on the max-∆G theory [9].

Materials:

- High-purity precursor powders.

- Synchrotron or laboratory X-ray diffractometer with a high-temperature reaction stage.

- Inert atmosphere sample chamber (if required).

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Mix precursor powders in a predetermined molar ratio using a mortar and pestle or ball mill. For thin samples, spread the mixture evenly in a sample holder compatible with the in-situ stage.

- Data Collection Setup: Mount the sample in the in-situ stage. Program the heating protocol (e.g., heat to 700°C at 10°C/min, then hold isothermally). Set the XRD to collect patterns at a high frequency (e.g., every 30 seconds or 1-2 scans per minute) throughout the heating and hold segments [9].

- Execution and Monitoring: Initiate the heating program and simultaneous XRD data collection. Monitor the data stream in real-time for the appearance of new diffraction peaks, which signify the crystallization of a new phase.

- Phase Identification: Analyze the sequential XRD patterns using a crystal database (e.g., ICDD PDF-4+) and phase identification software. The first new set of diffraction peaks that appear and grow in intensity corresponds to the first crystalline reaction product.

- Validation: Compare the identified first product to the phase predicted by the max-∆G theory. A successful prediction requires the driving force for the observed product to be ≥60 meV/atom more negative than that of other competing phases [9].

Protocol: Pairwise Reaction Analysis for Pathway Deconvolution

Objective: To deconstruct a complex multi-precursor reaction pathway into a sequence of simpler pairwise reactions, identifying critical intermediates that consume the driving force [5].

Materials:

- Quenched or in-situ samples from various reaction stages (time or temperature).

- X-ray diffractometer.

- Computational access to a thermochemistry database (e.g., Materials Project).

Procedure:

- Pathway Sampling: Perform synthesis experiments with the chosen precursor set, stopping the reaction at multiple stages (e.g., different temperatures or hold times). Quench the samples rapidly to preserve the phase assemblage at that snapshot.

- Phase Identification: Collect XRD patterns for each sample and identify all crystalline phases present at each stage using phase identification software and databases.

- Reaction Hypothesis: For each step where a new phase appears, list all possible chemical reactions between the phases present in the previous step that could stoichiometrically form the new phase.

- Thermodynamic Ranking: For each hypothesized pairwise reaction, calculate the reaction energy (∆G) using formation energies from a thermochemical database like the Materials Project [5] [10].

- Pathway Construction: The most likely reaction pathway is constructed by selecting the pairwise reactions with the largest (most negative) driving forces that are consistent with the observed sequence of phase appearances. This reveals which stable intermediates form early and consume the available energy, potentially hindering the target's formation [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Thermodynamic and Pathway Analysis

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Materials Project Database | Provides computed thermodynamic data (formation energies, ∆G) for thousands of compounds, enabling initial ranking of precursors and calculation of pairwise reaction energies [5] [10]. |

| Precursor Powders (e.g., Y₂O₃, BaCO₃, CuO) | High-purity, commonly available solid powders used as starting points for solid-state synthesis experiments [5]. |

| In Situ XRD Setup | A diffractometer coupled with a heating stage allows for real-time monitoring of phase formation and transformation during reactions, crucial for identifying first products and intermediates [9]. |

| Machine Learning XRD Analyzer | Software tool for automated, rapid identification of crystalline phases from XRD patterns, enabling high-throughput analysis required for autonomous loops [5]. |

| ARROWS3 Algorithm | The core algorithm that integrates thermodynamics, pairwise analysis, and active learning to autonomously guide precursor selection and optimize synthesis routes [5] [11]. |

| Acid-PEG4-S-PEG4-Acid | Acid-PEG4-S-PEG4-Acid, MF:C22H42O12S, MW:530.6 g/mol |

| Thalidomide-O-PEG4-NHS ester | Thalidomide-O-PEG4-NHS ester, MF:C28H33N3O13, MW:619.6 g/mol |

The Role of Ab Initio Data from Materials Project and DeepMind

The discovery and synthesis of novel inorganic materials are fundamental to technological advances in fields ranging from clean energy to information processing. Traditional experimental approaches, reliant on painstaking trial and error, are impractical to scale. The emergence of large-scale ab initio computational data has revolutionized this field, serving as the foundation for predictive models and autonomous synthesis platforms. This Application Note details the methodologies and protocols for leveraging ab initio data from the Materials Project (MP) and Google DeepMind's GNoME project within the research context of autonomous reaction route optimization for solid-state synthesis. We frame these resources as critical reagents in a modern computational toolkit, enabling researchers to move from target discovery to viable synthesis pathways with unprecedented speed.

The Ab Initio Data Landscape: Materials Project and GNoME

Ab initio data, particularly from Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations, provides a quantum-mechanically informed approximation of material properties, most critically stability. The Materials Project and GNoME represent two generations of scale in the generation and utilization of this data.

The following table summarizes the key quantitative aspects of these two primary data sources.

Table 1: Comparison of Ab Initio Data Resources

| Feature | Materials Project (MP) | Google DeepMind's GNoME |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | A database of DFT-calculated properties for known and predicted materials [12]. | A deep learning-driven discovery platform for novel stable crystals [13]. |

| Scale of Stable Materials | ~48,000 computationally stable materials (pre-GNoME baseline) [14]. | 381,000 novel stable materials discovered; an order-of-magnitude expansion to a total of 421,000 known stable crystals [13] [14]. |

| DFT Methodology | Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package (VASP). Uses a mix of GGA and GGA+U functionals. Calculations performed at 0 K, 0 atm with spin polarization [12]. | Uses VASP for DFT verification. Calculations use the PBE functional, with a subset validated using higher-fidelity r²SCAN [15] [14]. |

| Key Data for Synthesis | Reaction energies, thermodynamic driving force (ΔG) for precursor selection [11]. | Novel crystal structures and their predicted stability, massively expanding the space of synthetic targets [13]. |

| Molecular Data (MPcules) | Uses Q-Chem with range-separated hybrid functionals (e.g., ωB97X-V) and property-optimized basis sets (e.g., def2-TZVPPD) for molecular property calculations [16]. | Not Applicable |

Experimental Protocol: Autonomous Precursor Selection with ARROWS3

The ARROWS3 (Autonomous Reaction Route Optimization with Solid-State Synthesis) algorithm exemplifies how MP and GNoME data can be integrated into an active learning loop for optimizing solid-state synthesis precursors [11]. The protocol below details this process.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of the ARROWS3 algorithm, integrating computational data with experimental validation.

Step-by-Step Methodology

Step 1: Target and Precursor Definition

- Input: The desired composition and structure of the target material.

- Action: Define a comprehensive list of available solid powder precursors. The algorithm generates all stoichiometrically balanced precursor sets that can yield the target's composition [11].

Step 2: Initial Thermodynamic Ranking

- Action: In the absence of prior experimental data, rank all precursor sets based on the thermodynamic driving force (ΔG) to form the target. This is calculated using ab initio reaction energies from the Materials Project database [11].

- Rationale: Reactions with the largest (most negative) ΔG tend to occur most rapidly and are prioritized initially [11].

Step 3: Experimental Validation and Pathway Snapshot

- Action: Synthesize the highest-ranked precursor sets. Heat each set at a range of temperatures (e.g., 600°C, 700°C, 800°C, 900°C) to provide snapshots of the reaction pathway at different stages [11].

- Characterization: Analyze the products at each temperature using X-ray Diffraction (XRD).

- Data Processing: Use machine-learned analysis of XRD patterns to identify the crystalline intermediate phases present at each step [11].

Step 4: Algorithmic Learning and Re-Ranking

- Action: ARROWS3 analyzes the experimental results to determine which pairwise reactions led to the observed intermediates.

- Learning: The algorithm uses this information to predict which intermediates will form in precursor sets that have not yet been tested.

- Re-ranking: The precursor ranking is updated. ARROWS3 now prioritizes sets predicted to avoid highly stable intermediates that consume the driving force, thereby retaining a larger effective driving force (ΔG') for the final step of forming the target material [11].

Step 5: Iteration and Convergence

- Action: The updated ranking guides the next round of experiments (return to Step 3).

- Termination Condition: The loop continues until the target material is synthesized with sufficient yield or all viable precursor sets are exhausted [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

In autonomous materials research, computational data and algorithms function as critical reagents. The following table details key components of the modern materials informatics toolkit.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Autonomous Synthesis

| Reagent / Resource | Function in Workflow | Specifics / Examples |

|---|---|---|

| GNoME Database | Target Discovery: Provides millions of novel, predicted-stable crystal structures as synthetic targets [13] [15]. | 381,000 stable crystals on the convex hull. Data includes structures, compositions, and DFT-calculated energies [13]. |

| Materials Project API | Thermodynamic Data: Supplies critical ab initio data on reaction energies and phase stability for known and predicted materials [12] [11]. | Used for calculating the initial thermodynamic driving force (ΔG) in precursor ranking [11]. |

| ARROWS3 Algorithm | Route Optimization: An active learning algorithm that uses experimental failure to iteratively optimize precursor selection for a given target [11]. | Incorporates domain knowledge (thermodynamics, pairwise reactions) to move beyond black-box optimization. |

| VASP / Q-Chem | Ab Initio Computation: First-principles software packages used to compute the underlying ab initio data (e.g., total energy, stability) in MP and GNoME [12] [16]. | VASP for periodic solids [12]; Q-Chem for molecular properties (MPcules) [16]. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Stability Prediction: The machine learning architecture at the core of GNoME, trained on ab initio data to predict crystal stability with high accuracy [13] [14]. | GNoME models achieved a prediction error of 11 meV/atom and >80% precision in identifying stable structures [14]. |

| 5-Carboxyrhodamine 110 NHS Ester | 5-Carboxyrhodamine 110 NHS Ester | |

| DBCO-PEG4-Propionic-Val-Cit-PAB | DBCO-PEG4-Propionic-Val-Cit-PAB, MF:C46H59N7O10, MW:870.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Visualization: The GNoME Discovery Engine

The massive expansion of stable materials by GNoME is powered by a scalable, iterative discovery engine. The following diagram outlines its core components and active learning cycle.

The integration of large-scale ab initio data from the Materials Project and GNoME with active learning algorithms like ARROWS3 represents a paradigm shift in solid-state chemistry. This approach transforms the materials research and development workflow from a slow, sequential process into a high-throughput, autonomous loop. By treating these computational resources as essential reagents in the research toolkit, scientists can now navigate the vast chemical space of inorganic materials with unprecedented efficiency, dramatically accelerating the discovery and synthesis of next-generation functional materials.

Inside ARROWS3: How the Algorithm Plans and Learns from Experiments

Autonomous research platforms are transforming solid-state materials synthesis by integrating artificial intelligence, robotics, and high-throughput experimentation into a continuous closed-loop cycle. A critical component enabling this transformation is the development of sophisticated algorithms that can autonomously plan and optimize synthesis routes. This application note details the workflow of ARROWS3 (Autonomous Reaction Route Optimization with Solid-State Synthesis), an algorithm specifically designed to automate the selection of optimal precursors for solid-state materials synthesis. By actively learning from experimental outcomes, ARROWS3 dynamically identifies and avoids precursor combinations that lead to unfavorable reaction pathways, thereby accelerating the discovery of successful synthesis routes with minimal human intervention. The protocol outlined herein is framed within the broader context of developing fully autonomous research platforms for materials discovery [5] [7].

Algorithm Workflow

The ARROWS3 algorithm implements a structured workflow that transforms a target material specification into experimentally validated precursor proposals. The process integrates thermodynamic calculations, experimental validation, and machine learning in an iterative cycle that continuously refines the algorithm's predictive capabilities [5].

Workflow Diagram

Diagram 1: ARROWS3 Algorithm Workflow. The workflow progresses from target input through iterative experimental learning cycles to successful precursor proposal.

Stage Protocols

Stage 1: Target Input and Precursor Generation

Objective: Generate all chemically plausible precursor sets that can be stoichiometrically balanced to yield the target material's composition.

Procedure:

- Input Target Specification: Define the target material by its chemical composition and crystal structure.

- Query Precursor Database: Access a database of available precursor compounds with their chemical formulas and physical properties.

- Generate Combinations: Systematically enumerate precursor combinations that collectively contain the required elements in the correct stoichiometric ratios.

- Filter Implausible Sets: Apply basic chemical rules to exclude combinations with obvious reactivity conflicts or impracticality.

Technical Notes: The algorithm considers both single-source and multiple-source precursors, with the initial selection based primarily on elemental composition matching rather than anticipated reactivity [5].

Stage 2: Initial Thermodynamic Ranking

Objective: Rank generated precursor sets based on their calculated thermodynamic driving force to form the target material.

Procedure:

- Calculate Reaction Energies: For each precursor set, compute the reaction energy (ΔG) to form the target material using density functional theory (DFT) data from sources such as the Materials Project [5].

- Rank by Driving Force: Sort precursor sets from most negative (largest driving force) to least negative ΔG values.

- Establish Priority Queue: Create an experimental priority list based primarily on thermodynamic favorability.

Technical Notes: While kinetics often dominate solid-state synthesis outcomes, thermodynamic driving force provides a valuable initial screening metric. Precursor sets with highly negative ΔG values are prioritized for initial experimental testing [5].

Stage 3: Experimental Proposal and Execution

Objective: Propose and execute synthesis experiments across multiple temperature conditions to map reaction pathways.

Procedure:

- Select Top Candidates: Choose the highest-ranked precursor sets from the current priority list.

- Define Temperature Profile: For each precursor set, propose experiments across a temperature range (e.g., 600°C to 900°C in solid-state synthesis).

- Execute Robotic Synthesis: Utilize automated robotic systems to:

- Precisely weigh and mix precursor powders

- Transfer mixtures to appropriate crucibles

- Execute heating protocols with controlled ramp rates and dwell times

- Perform In Situ/Ex Situ Characterization: Analyze products using X-ray diffraction (XRD) after each thermal treatment.

Technical Notes: Testing multiple temperatures provides "snapshots" of the reaction pathway, revealing intermediate phases that form at different stages of the synthesis [5].

Stage 4: Phase Identification and Intermediate Analysis

Objective: Identify crystalline phases present in synthesis products and determine which pairwise reactions led to their formation.

Procedure:

- Collect XRD Patterns: Acquire diffraction data from synthesized samples.

- Automated Phase Identification: Utilize machine learning models (e.g., XRD-AutoAnalyzer) to identify crystalline phases present in each sample [5].

- Map Reaction Pathways: Trace the formation of intermediate phases back to specific pairwise reactions between precursors.

- Calculate Consumed Driving Force: Determine how much thermodynamic driving force was consumed by intermediate formation (ΔG').

Technical Notes: The identification of "blocking" intermediates that consume excessive driving force is crucial for understanding why certain precursor sets fail to produce the target material [5].

Stage 5: Learning and Ranking Update

Objective: Update the precursor ranking based on experimental outcomes to avoid unfavorable reaction pathways in future iterations.

Procedure:

- Analyze Failed Syntheses: For experiments that did not yield the target, identify which intermediate phases prevented target formation.

- Predict Intermediate Formation: Use information from tested precursor sets to predict which untested precursor combinations are likely to form similar problematic intermediates.

- Reprioritize Precursor Sets: Demote precursor sets predicted to form blocking intermediates and promote those with clearer pathways to the target.

- Propose New Experiments: Select the newly highest-ranked precursor sets for the next round of experimental testing.

Technical Notes: This active learning component enables ARROWS3 to become more effective with each experimental iteration, continuously refining its understanding of the synthesis landscape [5].

Experimental Validation and Performance

The ARROWS3 algorithm has been experimentally validated across multiple materials systems, demonstrating substantially improved performance compared to black-box optimization approaches.

Table 1: ARROWS3 Performance on Experimental Datasets

| Target Material | Chemical System | Total Experiments | Successful Routes Identified | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YBa₂Cu₃O₆₅ (YBCO) | Y-Ba-Cu-O | 188 | 10 | Identified all effective precursor combinations with fewer iterations than Bayesian optimization [5] |

| Naâ‚‚Te₃Mo₃Oâ‚₆ (NTMO) | Na-Te-Mo-O | Not specified | Successful synthesis | Metastable target successfully prepared despite DFT-predicted instability [5] |

| LiTiOPOâ‚„ (t-LTOPO) | Li-Ti-P-O | Not specified | Successful synthesis | Selective formation of triclinic polymorph over stable orthorhombic phase [5] |

Case Study: YBCO Synthesis Optimization

Background: The synthesis of phase-pure YBa₂Cu₃O₆₅ (YBCO) was used as a benchmark system due to its sensitivity to precursor selection and formation of intermediate compounds that can consume available reaction driving force.

Experimental Protocol:

- Precursor Selection: 47 different precursor combinations from the Y-Ba-Cu-O chemical space were tested, including oxides, carbonates, and other commonly available salts.

- Temperature Variation: Each precursor set was heated at four different temperatures (600°C, 700°C, 800°C, and 900°C) with a hold time of 4 hours.

- Phase Analysis: Products were analyzed using XRD with machine learning-assisted phase identification.

- Iterative Refinement: After each experimental batch, ARROWS3 updated its precursor rankings based on observed reaction pathways.

Results: From 188 total experiments, only 10 produced phase-pure YBCO without detectable impurities. ARROWS3 successfully identified all effective precursor combinations while requiring fewer experimental iterations than Bayesian optimization or genetic algorithms [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of autonomous synthesis workflows requires both computational and experimental components. The following table details essential materials and computational resources used in the ARROWS3 workflow.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Item Name | Type | Function/Purpose | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solid Precursor Library | Chemical Reagents | Provides elemental constituents for target material | Oxides, carbonates, and other salts covering relevant chemical space [5] |

| Robotic Synthesis Platform | Hardware | Automated weighing, mixing, and heating of samples | Custom or commercial systems for solid-state synthesis (e.g., A-Lab) [7] |

| XRD with ML Analysis | Characterization + Software | Phase identification and quantification | X-ray diffractometer coupled to machine learning models (XRD-AutoAnalyzer) [5] |

| Thermochemical Database | Computational Resource | Provides DFT-calculated reaction energies | Materials Project database for initial ΔG calculations [5] |

| Precursor Ranking Algorithm | Software | Updates precursor priorities based on experiments | ARROWS3 core algorithm implementing active learning [5] |

| 19,20-Epoxycytochalasin D | 19,20-Epoxycytochalasin D, MF:C30H37NO7, MW:523.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Boc-L-Tyr(2-azidoethyl)-OH | Boc-L-Tyr(2-azidoethyl)-OH, MF:C16H22N4O5, MW:350.37 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Integration with Autonomous Research Platforms

The ARROWS3 algorithm functions as a critical decision-making component within broader autonomous laboratory ecosystems. These integrated systems combine computational planning with robotic execution to enable continuous, closed-loop materials discovery.

Diagram 2: Autonomous Laboratory Integration. ARROWS3 serves as the optimization engine within a broader autonomous materials discovery platform.

In platforms such as A-Lab, ARROWS3 interacts with multiple specialized components:

- Target Selection: Novel materials are identified through high-throughput DFT calculations of phase stability [7]

- Recipe Generation: Natural language processing models trained on literature data propose initial synthesis procedures [7]

- Robotic Execution: Automated systems handle powder processing, mixing, and heat treatment [7]

- Phase Identification: Machine learning models analyze characterization data to identify crystalline phases [7]

This integration creates a continuous cycle where computational predictions inform experiments, and experimental outcomes refine computational models, dramatically accelerating the pace of materials discovery.

The ARROWS3 algorithm represents a significant advancement in autonomous materials synthesis by incorporating domain knowledge of solid-state reaction mechanisms into an active learning framework. Unlike black-box optimization approaches, ARROWS3 explicitly models the formation of intermediate compounds and their impact on reaction pathways, enabling more efficient identification of successful precursor combinations. The workflow detailed in this application note—from target input through iterative experimental learning to validated precursor proposal—provides researchers with a robust protocol for implementing autonomous synthesis optimization in their own laboratories. As autonomous research platforms continue to evolve, algorithms like ARROWS3 will play an increasingly critical role in accelerating the discovery and development of novel materials for energy, electronics, and pharmaceutical applications.

Autonomous laboratories represent a paradigm shift in materials science, integrating artificial intelligence, robotic experimentation, and automation technologies into continuous closed-loop cycles to accelerate scientific discovery with minimal human intervention [7]. Within this framework, initial recipe generation serves as the critical entry point for planning solid-state synthesis experiments. This process leverages natural language models (NLMs) trained on extensive historical data to propose viable synthesis procedures for target materials [7] [5].

The transformation from traditional trial-and-error approaches to AI-driven methodologies addresses fundamental challenges in navigating vast chemical spaces [17]. By interpreting and processing structured and unstructured data from scientific literature, patents, and experimental reports, NLMs enable researchers to rapidly generate potential synthesis routes that would otherwise require extensive domain expertise and manual literature review [17]. This capability is particularly valuable for solid-state synthesis, where outcomes are often difficult to predict due to the formation of inert byproducts that compete with the target material and reduce yield [5].

The integration of recipe generation into autonomous research platforms establishes a comprehensive workflow where AI models propose initial synthesis schemes, robotic systems execute experiments, and characterization data feeds back to improve subsequent predictions [7]. This closed-loop approach minimizes downtime between operations, eliminates subjective decision points, and enables rapid exploration of novel materials and optimization strategies [7]. As the field advances, the ability to accurately generate initial recipes has become increasingly critical for turning processes that once took months of trial and error into routine high-throughput workflows.

Background and Significance

Solid-state synthesis of inorganic materials has long relied on practitioner experience, literature references, and heuristic rules when selecting precursors and reaction conditions [5]. This approach presents significant limitations when targeting novel compounds, as even materials predicted to be thermodynamically stable can prove difficult to synthesize due to kinetic barriers and intermediate compound formation [5]. The expertise-dependent nature of traditional synthesis planning creates bottlenecks in materials discovery pipelines.

The emergence of large-scale chemical databases has created unprecedented opportunities for data-driven approaches to recipe generation. Platforms such as the Materials Project and Google DeepMind have provided extensive repositories of computed material properties and stability data [7], while literature extraction tools like ChemDataExtractor, ChemicalTagger, and OSCAR4 have enabled the mining of synthetic procedures from published research articles [17]. These resources collectively form the knowledge foundation upon which NLMs for recipe generation are built.

Early computational approaches to synthesis planning primarily relied on thermodynamic calculations, using density functional theory (DFT) to assess reaction energies and identify promising precursor combinations [5]. While valuable, these methods often failed to account for kinetic factors and experimental practicalities. The development of active learning algorithms marked a significant advancement, enabling systems to adapt from experimental outcomes and refine their recommendations based on both positive and negative results [5]. This iterative learning capability is essential for addressing the complex multi-parameter optimization challenges inherent to solid-state synthesis.

Table 1: Evolution of Computational Approaches to Recipe Generation

| Approach | Key Features | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Expert Heuristics | Based on experimental experience and literature precedents | Difficult to transfer and scale; limited for novel materials |

| Thermodynamic Modeling | Uses DFT calculations to predict reaction energies | Computationally intensive; overlooks kinetic factors |

| Machine Learning | Learns patterns from historical synthesis data | Requires large, high-quality datasets |

| Active Learning | Iteratively improves suggestions based on experimental feedback | Complex implementation; requires integration with robotic platforms |

Methodology

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

The development of effective recipe generation systems begins with the construction of comprehensive chemical science databases that integrate diverse data modalities [17]. These databases incorporate structured information from proprietary sources (Reaxys, SciFinder) and open-access platforms (ChEMBL, PubChem), alongside unstructured data extracted from scientific literature and patents using natural language processing (NLP) techniques [17]. This multi-source approach ensures broad coverage of known synthetic procedures and material systems.

Text mining and named entity recognition (NER) play crucial roles in converting unstructured textual information into structured, machine-readable formats [17]. Specialized toolkits such as ChemDataExtractor implement NLP pipelines that identify and extract chemical compounds, reactions, and conditions from scientific documents [17]. The extracted information is typically organized into knowledge graphs (KGs) that represent complex relationships between precursors, targets, and reaction parameters, providing a rich structured foundation for training NLMs [17].

Data standardization represents a critical preprocessing step, particularly for solid-state synthesis where ingredient formats and measurements vary considerably across literature sources [18]. The Food.com dataset preprocessing pipeline exemplifies this approach, involving extraction of recipe names, ingredients lists, and cooking instructions, followed by standardization of ingredient formats and measurements, tokenization, and creation of input-output pairs for model training [18]. Similar standardization is essential for materials synthesis data, though with additional complexity due to the three-dimensional structural considerations of solid-state systems.

Model Architectures and Training

Current approaches to recipe generation leverage a diverse range of language model architectures, from encoder-decoder transformers to decoder-only models [18]. The T5 (Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer) architecture has demonstrated particular utility for recipe generation tasks, as its text-to-text framework naturally accommodates the transformation of precursor-target pairs into detailed synthesis procedures [18]. Similarly, models based on the GPT architecture have been applied to generate coherent, multi-step recipes from minimal input specifications.

Domain adaptation through specialized training is essential for effective chemical recipe generation. The process typically involves two stages: domain pre-training using extensive chemical literature corpora, followed by instruction tuning with chemistry-focused instructions derived from chemical databases [19]. For example, ChemDFM underwent pre-training on a corpus containing 34 billion tokens extracted from over 3.8 million papers and 1,400 textbooks, followed by instruction tuning with 2.7 million chemistry-focused instructions [19]. This approach preserves the general reasoning capabilities of large language models while instilling deep chemical expertise.

Fine-tuning strategies for recipe generation models must carefully balance exposure to general textual patterns and specialized chemical knowledge. Transfer learning from models pre-trained on general corpora significantly reduces training time and computational requirements compared to training from scratch [18]. The fine-tuning process typically employs standard language modeling objectives, with models learning to predict the next token in synthesis procedures based on precursor information and target materials. For smaller models with limited parameters, techniques such as QLORA (Quantized Low-Rank Adaptation) enable efficient fine-tuning while maintaining performance [18].

Table 2: Comparison of Model Sizes and Applications in Recipe Generation

| Model | Parameters | Architecture | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| T5-small | 60 million | Encoder-decoder | Single-step recipe generation |

| SmolLM-135M | 135 million | Decoder-only | Limited-scale recipe generation |

| SmolLM-360M | 360 million | Decoder-only | Moderate-complexity synthesis |

| SmolLM-1.7B | 1.7 billion | Decoder-only | Complex multi-step recipes |

| Phi-2 | 2.7 billion | Transformer | High-precision recipe generation |

Integration with Synthesis Planning Algorithms

Effective recipe generation systems do not operate in isolation but are integrated with synthesis planning algorithms that incorporate thermodynamic principles and domain knowledge. The ARROWS3 algorithm exemplifies this approach, combining initial recipe generation with active learning based on experimental outcomes [5]. This algorithm actively learns from failed experiments to identify precursors that lead to unfavorable reactions forming highly stable intermediates, then proposes new experiments using precursors predicted to avoid such intermediates [5].

The integration between NLMs and traditional optimization algorithms creates a powerful hybrid approach to synthesis planning. While NLMs excel at generating chemically plausible recipes based on historical patterns, algorithms like Bayesian optimization and genetic algorithms provide rigorous mathematical frameworks for navigating complex parameter spaces [17]. This combination leverages both the pattern recognition capabilities of neural networks and the systematic exploration strengths of traditional optimization methods.

Retrosynthetic analysis represents another valuable integration point for recipe generation systems. Inspired by organic chemistry practices, this approach starts from the target material and works backward through stepwise decomposition until reaching available starting materials [20]. NLMs can enhance this process by evaluating potential decomposition pathways and selecting those most likely to lead to feasible synthetic routes. This strategy has proven particularly valuable for metastable materials, which require careful precursor selection to avoid thermodynamically favored byproducts [5].

Application Notes

Solid-State Synthesis of Inorganic Materials

The application of NLMs to solid-state synthesis of inorganic materials demonstrates the practical utility of recipe generation in autonomous laboratories. In the A-Lab system developed by DeepMind, NLMs trained on literature data generate initial synthesis recipes for target materials identified through computational screening [7]. This system successfully synthesized 41 of 58 target materials over 17 days of continuous operation, achieving a 71% success rate with minimal human intervention [7]. The integration of ML models for precursor selection, convolutional neural networks for XRD phase analysis, and the ARROWS3 algorithm for iterative route improvement created a comprehensive autonomous workflow.

For the synthesis of YBa₂Cu₃O₆.₅ (YBCO), a comprehensive dataset of 188 experiments testing 47 different precursor combinations across four synthesis temperatures provided valuable benchmarking data for recipe generation systems [5]. This dataset included both positive and negative outcomes, enabling the development of models that learn from failed experiments rather than being trained exclusively on successful procedures [5]. The presence of both outcome types is critical for developing robust recipe generation systems that can anticipate and avoid common failure modes.

The challenges of synthesizing metastable materials highlight the advanced capabilities of modern recipe generation systems. For targets such as Naâ‚‚Te₃Mo₃Oâ‚₆ (NTMO) and triclinic LiTiOPOâ‚„ (t-LTOPO), which are metastable with respect to decomposition into more thermodynamically favorable phases, conventional synthesis approaches often fail [5]. Recipe generation systems address this challenge by identifying precursor combinations and reaction conditions that bypass the formation of stable intermediates, leveraging both historical data and thermodynamic calculations to maintain kinetic control over the synthesis pathway [5].

Organic Synthesis Applications

In organic chemistry, specialized systems such as SynAsk demonstrate the adaptation of recipe generation principles to molecular synthesis [21]. This comprehensive organic chemistry domain-specific LLM platform integrates fine-tuned language models with a chain-of-thought approach to access knowledge bases and advanced chemistry tools in a question-and-answer format [21]. The system incorporates functionalities including molecular information retrieval, reaction performance prediction, retrosynthesis prediction, and chemical literature acquisition, providing researchers with extensive support for synthetic planning.

The ChemDFM model represents another significant advancement in organic synthesis applications, specifically designed to bridge the gap between general-purpose language models and specialized chemical knowledge [19]. Through domain pre-training and instruction tuning, ChemDFM develops the ability to understand both natural language instructions and chemical representations, serving as a collaborative research partner rather than merely a task execution tool [19]. This capability is particularly valuable for complex organic syntheses requiring multi-step strategic planning.

Steerable synthesis planning represents a cutting-edge application of NLMs in organic chemistry, allowing chemists to specify desired synthetic strategies in natural language to find routes that satisfy these constraints [20]. For example, a researcher might request routes that "construct the pyrimidine ring in early stages" or "avoid palladium-catalyzed couplings," with the NLM-guided system identifying pathways that align with these strategic preferences [20]. This approach preserves the expert intuition and strategic thinking that characterize human chemical problem-solving while leveraging the comprehensive search capabilities of computational systems.

Case Study: Wollastonite-2M Synthesis

The single-step solid-state synthesis of Wollastonite-2M (CaSiO₃) from rice husk ash (RHA) and natural limestone provides a concrete example of recipe generation applied to practical materials synthesis [22]. This eco-friendly approach utilizes RHA as a silica source, converting agricultural waste into valuable functional materials while addressing disposal challenges [22]. The development of a "single-step" protocol representing an innovation over previous multi-step methods demonstrates how recipe generation can optimize synthetic efficiency.

The successful synthesis highlights several key considerations for recipe generation systems. First, the use of alternative silica sources requires adjustments to reaction stoichiometry and conditions compared to conventional quartz-based syntheses [22]. Second, the single-step protocol eliminates intermediate processing stages such as autoclaving and multiple sintering steps, significantly streamlining the synthesis pathway [22]. These optimizations reflect the type of procedural innovations that advanced recipe generation systems can propose by identifying patterns across diverse literature sources and experimental datasets.

The economic and environmental implications of the wollastonite synthesis case study underscore the broader potential of recipe generation systems to promote sustainable materials development. By identifying pathways that utilize waste materials and minimize energy-intensive processing steps, these systems can contribute to more environmentally benign synthetic approaches [22]. This alignment with green chemistry principles represents an important secondary benefit beyond the primary goal of accelerating materials discovery.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fine-Tuning Language Models for Recipe Generation

Purpose: To adapt pre-trained language models for the specific task of generating solid-state synthesis recipes.

Materials and Software:

- Pre-trained language model (T5, GPT, or similar)

- Domain-specific dataset (e.g., extracted synthesis procedures)

- Deep learning framework (PyTorch, TensorFlow)

- High-performance computing resources (GPUs recommended)

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Collect and preprocess solid-state synthesis data from literature databases and experimental records. Standardize ingredient names, measurements, and procedural descriptions to ensure consistency [18].

- Input-Output Formatting: Structure the training data as input-output pairs where the input contains the target material and potential precursors, and the output contains the detailed synthesis procedure [18].

- Model Selection: Choose an appropriate pre-trained model architecture based on the complexity of the generation task. For limited computational resources, consider smaller models like T5-small or SmolLM-135M [18].

- Fine-Tuning: Train the selected model using the prepared dataset. For large models with limited resources, employ parameter-efficient fine-tuning methods such as QLORA with a rank of 8 [18].

- Validation: Evaluate model performance on a held-out test set using both traditional NLP metrics (BLEU, ROUGE) and domain-specific metrics (ingredient coverage, procedural coherence) [18].

- Iteration: Refine the model based on validation results, adjusting hyperparameters or incorporating additional training data as needed.

Troubleshooting:

- If the model generates chemically implausible recipes, increase the proportion of domain-specific data in training or incorporate constraint mechanisms during generation.

- If the model exhibits poor diversity in recipe generation, adjust sampling temperature or incorporate diversity-promoting training objectives.

Protocol 2: Autonomous Synthesis Using Generated Recipes

Purpose: To experimentally validate recipes generated by NLMs using an autonomous laboratory platform.

Materials and Equipment:

- Robotic synthesis platform (e.g., Chemspeed ISynth synthesizer)

- Characterization instruments (XRD, UPLC-MS, benchtop NMR)

- Mobile robots for sample transport (optional)

- Precursor materials

- Generated synthesis recipes

Procedure:

- Recipe Selection: Choose high-confidence recipes generated by the NLM for experimental validation. Consider precursor availability and safety constraints [7].

- Automated Synthesis Preparation: Program the robotic system with the selected recipe, including precise measurements, mixing sequences, and heating profiles [7].

- Reaction Execution: Initiate the automated synthesis procedure. For solid-state reactions, this typically involves precise powder handling, mixing, and calcination in controlled atmospheres [5].

- In-line Characterization: Transfer samples to analytical instruments for immediate characterization. For solid-state materials, XRD is particularly valuable for phase identification [5].

- Data Analysis: Automatically analyze characterization data to determine synthesis success. Machine learning models can assist in phase identification from XRD patterns [5].

- Feedback Integration: Record experimental outcomes and feed results back to the recipe generation system to improve future predictions [5].

Troubleshooting:

- If robotic handling of powders proves challenging, consider pelletizing precursors to improve handling reliability.

- If phase purity is insufficient, implement iterative grinding and heat treatment steps or adjust precursor selection to avoid intermediate compounds.

Protocol 3: Benchmarking Recipe Generation Performance

Purpose: To quantitatively evaluate the performance of recipe generation systems against established benchmarks.

Materials and Software:

- Benchmark dataset (e.g., YBCO synthesis dataset with 188 experiments)

- Evaluation metrics (traditional NLP and domain-specific)

- Baseline models for comparison

- Statistical analysis tools

Procedure:

- Dataset Preparation: Compile a comprehensive benchmark dataset containing both successful and failed synthesis attempts. The YBCO dataset with 47 precursor combinations across multiple temperatures provides a robust benchmark [5].

- Metric Selection: Define appropriate evaluation metrics including:

- Model Comparison: Evaluate multiple recipe generation systems on the benchmark dataset, including baseline models and newly proposed approaches.

- Statistical Analysis: Perform significance testing to determine meaningful performance differences between systems.

- Ablation Studies: Identify critical components of the recipe generation pipeline through systematic ablation experiments.

- Error Analysis: Categorize and analyze failure modes to identify areas for improvement.

Troubleshooting:

- If metrics correlate poorly with experimental success, develop additional domain-specific evaluation criteria.

- If benchmark performance saturates, create more challenging evaluation datasets targeting complex or metastable materials.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Autonomous Synthesis

| Reagent/Equipment | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|