Autonomous Phase Identification from XRD: A Machine Learning Framework for Accelerated Materials Discovery

This article explores the transformative integration of machine learning (ML) with X-ray diffraction (XRD) for autonomous phase identification, a critical task in materials science and pharmaceutical development.

Autonomous Phase Identification from XRD: A Machine Learning Framework for Accelerated Materials Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the transformative integration of machine learning (ML) with X-ray diffraction (XRD) for autonomous phase identification, a critical task in materials science and pharmaceutical development. It covers the foundational shift from traditional, labor-intensive methods to data-driven ML frameworks, detailing core architectures like Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and their application in analyzing complex multiphase mixtures. The content addresses key challenges such as data scarcity, model interpretability, and real-world validation, providing a comparative analysis of ML approaches against conventional techniques. By synthesizing recent advances and practical validation studies, this guide serves as a roadmap for researchers and scientists to implement robust, ML-driven XRD analysis, thereby accelerating the characterization and discovery of new materials and pharmaceutical forms.

From Bragg's Law to Deep Learning: The New Foundation of XRD Analysis

X-ray diffraction (XRD) stands as a fundamental technique in materials characterization, enabling the identification of crystalline phases and determination of structural properties across diverse fields from pharmaceutical development to materials science [1]. For decades, the analytical workflow for interpreting XRD data has been dominated by two primary methodologies: Search-Match library methods and Rietveld refinement [2]. While these traditional approaches have proven invaluable for analyzing well-characterized, single-phase materials, the evolving complexity of modern materials systems has exposed significant limitations. The emergence of novel materials such as high-entropy alloys, complex multi-phase systems, and nanostructured materials has created analytical challenges that exceed the capabilities of these conventional techniques [2]. This application note examines the fundamental constraints of traditional XRD analysis methods within the context of developing machine learning frameworks for autonomous phase identification, providing researchers with a structured understanding of both the theoretical and practical limitations that next-generation solutions must overcome.

Traditional XRD Analysis Methods: Core Principles and Workflows

Search-Match Library Method

The Search-Match approach represents the most fundamental technique for phase identification in XRD analysis. This method operates on a straightforward principle: comparing measured diffraction patterns against a database of known crystalline phases, typically using the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) or other reference libraries [3] [2]. The matching process evaluates both peak positions (determined by Bragg's law) and relative intensities to identify potential phase matches [1].

The experimental protocol for traditional search-match analysis involves a standardized workflow:

- Data Collection: Acquire a powder XRD pattern from the sample using a diffractometer with monochromatic Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å) [1].

- Peak Identification: Identify peak positions (2θ angles) and calculate corresponding d-spacings using Bragg's law (nλ = 2d sin θ) [1].

- Intensity Measurement: Determine relative peak intensities, typically normalized to the most intense peak.

- Database Search: Query reference databases using the observed d-spacings and intensity ratios as search parameters.

- Pattern Matching: Evaluate potential matches based on statistical similarity metrics between observed and reference patterns.

- Validation: Manually verify the best matches by comparing the full experimental and reference patterns.

This method serves as an efficient preliminary screening tool when analyzing materials composed of well-documented phases with minimal peak overlap [2].

Rietveld Refinement Method

Rietveld refinement, developed by Hugo Rietveld in the 1960s, represents a more sophisticated full-pattern fitting approach that refines a theoretical line profile until it matches the measured experimental profile [4] [3]. Unlike the Search-Match method which focuses on individual peaks, Rietveld analysis considers the entire diffraction pattern simultaneously, using a non-linear least squares approach to minimize differences between calculated and observed patterns [4].

The technique requires a pre-existing structural model as a starting point and can extract detailed structural parameters through an iterative refinement process [4] [3]. A standard Rietveld refinement protocol involves:

- Model Selection: Obtain Crystallographic Information Files (CIFs) for suspected phases from reference databases such as the ICSD [3].

- Instrument Calibration: Collect diffraction pattern from a standard sample (e.g., Al₂O₃ or Si) to characterize and correct for instrumental broadening contributions [3].

- Initial Fitting: Define initial parameters including unit cell dimensions, atomic coordinates, thermal parameters, and peak shape functions [4].

- Background Modeling: Fit a polynomial function to estimate and subtract background scattering.

- Iterative Refinement: Sequentially refine scale factors, lattice parameters, atomic positions, thermal parameters, and peak shape parameters using least-squares minimization.

- Quality Assessment: Monitor agreement factors (R-values) including Râ‚š, Rwp, and Rexp, with goodness-of-fit (GOF) approaching 1.0 indicating an ideal refinement [3].

The refinement workflow extracts quantitative information including phase fractions, crystallite size, microstrain, and atomic displacement parameters [4] [3].

Figure 1: Traditional XRD analysis workflow demonstrating multiple points requiring expert intervention, creating bottlenecks in high-throughput environments.

Critical Limitations of Traditional Approaches

Fundamental Methodological Constraints

The transition toward complex material systems has exposed intrinsic limitations in both traditional XRD analysis methods, which manifest as critical bottlenecks in modern research and development pipelines.

Search-Match Limitations:

- Novel Phase Identification: The method fails completely when analyzing materials containing phases not previously documented in reference databases [2].

- Peak Overlap Challenges: Accuracy declines significantly in multi-phase mixtures where diffraction peaks overlap, making unambiguous identification problematic [2].

- Limited Discriminatory Power: Materials with similar crystal structures but different chemical compositions may produce nearly identical diffraction patterns, leading to false identifications [5].

- Intensity Reliability: Peak intensities are strongly influenced by preferred orientation effects in powder samples, reducing matching reliability compared to d-spacing matching alone [4].

Rietveld Refinement Limitations:

- Model Dependency: Requires pre-existing structural models and cannot identify unknown phases without substantial manual intervention [4] [3].

- Computational Intensity: The iterative least-squares refinement process becomes computationally expensive and time-consuming for complex multi-phase systems [2].

- Local Minima Trapping: The non-linear refinement algorithm may converge to false minima, requiring expert guidance to achieve physically meaningful results [4].

- Initial Parameter Sensitivity: Success heavily depends on reasonable initial approximations of structural parameters, which may not be available for novel materials [4].

Practical Challenges in Modern Applications

Beyond fundamental methodological constraints, traditional XRD techniques face implementation challenges when addressing contemporary research needs.

Throughput and Automation Barriers:

- Manual Expertise Dependency: Both methods require significant expert intervention for pattern interpretation, model selection, and validation, creating bottlenecks in high-throughput environments [2].

- Processing Speed Limitations: Traditional Rietveld refinement cannot meet the demands of real-time analysis for in situ or operando studies where rapid decision-making is essential [6].

- Scalability Issues: The manual nature of these methods makes them poorly suited for analyzing large datasets comprising thousands of diffraction patterns from combinatorial materials studies [2].

Experimental Artifact Vulnerabilities:

- Idealized Pattern Assumptions: Rietveld refinement assumes ideal diffraction conditions, making it vulnerable to real-world imperfections including strain effects, preferred orientation, and background noise [2].

- Peak Broadening Complications: Both methods struggle with nanocrystalline or partially crystalline materials where significant peak broadening occurs, distorting both database matching and refinement accuracy [2].

- Amorphous Content Blindness: Traditional methods focus exclusively on crystalline phases, providing no quantitative information about amorphous content without additional specialized analysis techniques.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Traditional XRD Methods and Their Limitations

| Analysis Criterion | Search-Match Library | Rietveld Refinement |

|---|---|---|

| Unknown Phase Identification | Fails completely with novel phases | Requires pre-existing structural model |

| Multi-Phase Capability | Limited by peak overlap | Computationally intensive for complex mixtures |

| Processing Speed | Moderate | Slow, especially for complex systems |

| Automation Potential | Limited without manual validation | Limited due to parameter sensitivity |

| Experimental Artifact Resilience | Vulnerable to peak broadening | Assumes idealized conditions |

| Quantitative Accuracy | Semi-quantitative at best | High with appropriate models |

| Data Volume Handling | Moderate, manual validation bottleneck | Low due to computational demands |

| Expert Intervention Required | High for pattern interpretation | Very high for model selection & validation |

Impact on Advanced Material Systems

The limitations of traditional XRD analysis methods become particularly pronounced when applied to advanced material systems that represent the frontier of materials science research.

Complex Multi-Phase Materials: High-entropy alloys and advanced ceramics often contain multiple phases with significant peak overlap, creating challenges for both identification and quantification [2]. The Rietveld method struggles with the computational complexity of refining numerous structural parameters simultaneously, while Search-Match libraries may not contain all relevant phases for these novel material systems.

Nanostructured and Disordered Materials: Nanocrystalline materials exhibit broadened diffraction peaks that reduce the effectiveness of both pattern matching and refinement accuracy [3] [2]. Materials with significant stacking faults, disorder, or partial crystallinity present particular challenges as they deviate from the ideal crystal models assumed by traditional methods.

Dynamic and In Situ Studies: The slow processing speed of traditional Rietveld refinement prevents real-time analysis during in situ experiments monitoring phase transformations, such as battery cycling or solid-state reactions [6]. This limitation is particularly critical for capturing transient intermediate phases that may form only briefly during reactions [6].

The Machine Learning Framework: Addressing Traditional Limitations

The emergence of machine learning (ML) frameworks for autonomous phase identification represents a paradigm shift in XRD analysis, specifically designed to overcome the limitations of traditional methods. These approaches leverage computational intelligence to create adaptive, high-throughput analytical capabilities.

ML-Driven Autonomous Workflow

Machine learning approaches fundamentally reconfigure the XRD analysis pipeline through several key technological innovations:

Adaptive Data Acquisition: ML algorithms can interface directly with diffractometers to steer measurements toward regions of maximal information content [6]. This adaptive approach begins with rapid initial scans (e.g., 2θ = 10-60°) followed by targeted high-resolution measurements in specific angular regions where phase-discriminating features reside [6].

Integrated Analysis Architecture: Unlike sequential traditional workflows, ML frameworks perform simultaneous data collection and analysis through convolutional neural networks (CNN) and related architectures that extract both local peak features and global pattern context [2]. This integrated approach enables real-time decision-making during data acquisition.

Confidence-Driven Measurement: Autonomous systems employ uncertainty quantification to determine when sufficient data has been collected, continuing measurements only until predetermined confidence thresholds (typically >50%) are achieved for phase identification [6]. This confidence-based approach optimizes the trade-off between measurement time and analytical precision.

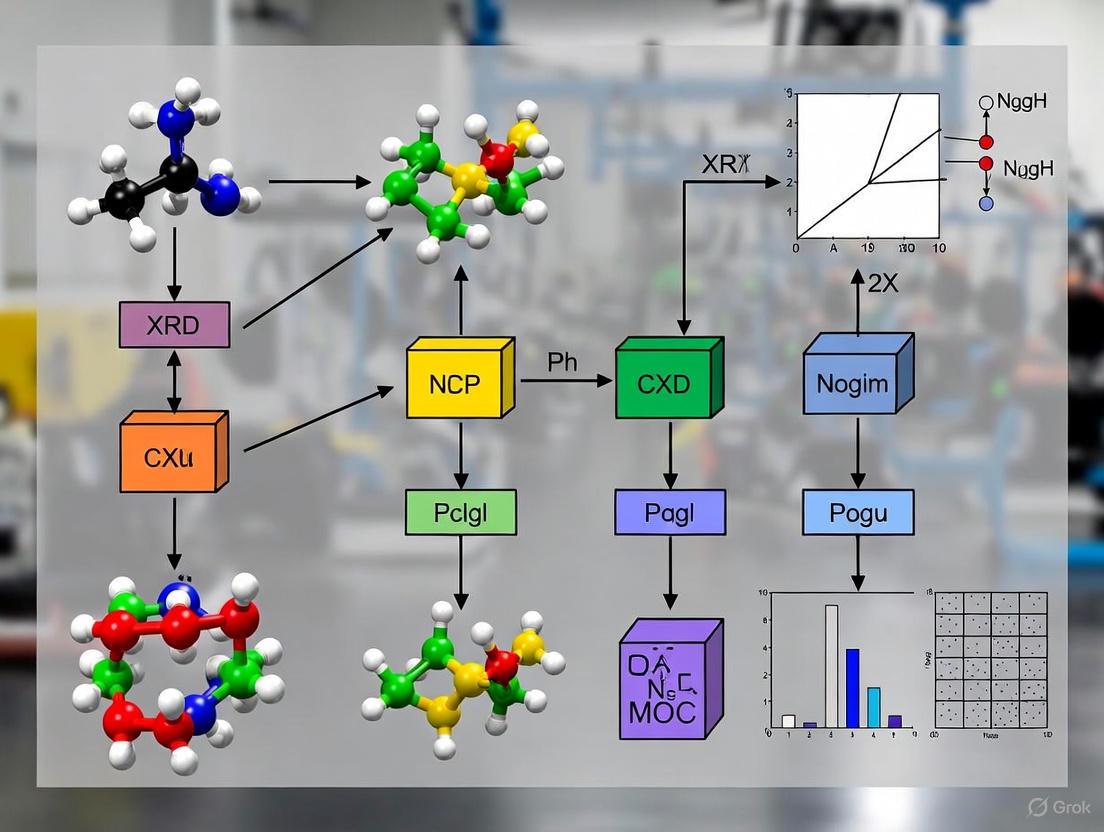

Figure 2: Machine learning-driven adaptive workflow for autonomous phase identification, featuring confidence-based measurement steering and minimal manual intervention.

Comparative Performance Advantages

ML frameworks demonstrate significant advantages over traditional methods across multiple performance metrics relevant to modern materials characterization.

Table 2: Performance Comparison Between Traditional and ML-Based XRD Analysis

| Performance Metric | Search-Match | Rietveld Refinement | ML-Based Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Processing Speed | Moderate | Slow | Fast (real-time capability) |

| Multi-Phase Handling | Low | Low to Moderate | High |

| Novel Phase Detection | None | None | Moderate (via anomalies) |

| Automation Level | Low | Low | High |

| Interpretability | Low | High (structural insights) | Black-box (with CAM guidance) |

| Scalability | Moderate | Low | High |

| Noise Resilience | Low | Moderate | High |

| Expert Intervention | High | Very High | Minimal |

Speed and Efficiency: ML models achieve phase identification orders of magnitude faster than Rietveld refinement, enabling real-time analysis capabilities essential for in situ studies of dynamic processes [2]. This speed advantage becomes particularly significant in high-throughput environments where thousands of patterns require analysis.

Complex Pattern Resolution: Convolutional Neural Networks excel at deconvoluting overlapping peaks in multi-phase samples through hierarchical feature extraction that simultaneously considers both local peak characteristics and global pattern context [2]. This capability addresses a fundamental limitation of both Search-Match and Rietveld methods.

Noise and Artifact Resilience: Through exposure to diverse training datasets, ML models develop robustness to experimental imperfections including noise, preferred orientation effects, and background variations [2]. This resilience enables reliable analysis of data collected under non-ideal conditions that would challenge traditional methods.

Implementation Protocols for ML-Driven XRD

The transition to ML-based XRD analysis requires specific methodological considerations and implementation protocols.

Data Preparation and Preprocessing:

- Training Data Curation: Assemble a comprehensive set of reference patterns from databases (ICSD, Crystallography Open Database) with appropriate data augmentation to ensure model robustness [2].

- Pattern Standardization: Implement consistent intensity normalization and angular calibration across all datasets to minimize instrumental artifacts [6].

- Feature Engineering: Extract both traditional descriptors (peak positions, intensities, widths) and learned representations through automated feature extraction [7].

Model Selection and Training:

- Architecture Selection: Choose appropriate neural network architectures based on analytical needs - CNNs for general classification, CNN-MLP hybrids for property regression, or VAEs for unsupervised exploration [2].

- Transfer Learning: Leverage pre-trained models when available, fine-tuning with domain-specific data to accelerate implementation [6].

- Validation Protocols: Implement rigorous cross-validation using holdout datasets with known phase compositions to quantify model performance and generalization capability [6].

Integration with Experimental Workflows:

- Closed-Loop Implementation: For adaptive XRD, establish bidirectional communication between the ML algorithm and diffractometer control software to enable real-time measurement steering [6].

- Confidence Thresholding: Define application-appropriate confidence thresholds for autonomous decision-making, typically starting at 50% for phase identification [6].

- Human-in-the-Loop Validation: Maintain expert oversight for critical findings while automating routine identifications, creating a hybrid workflow that balances efficiency with reliability.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of both traditional and ML-enhanced XRD analysis requires access to specific research tools and resources.

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for Advanced XRD Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Databases | ICDD PDF, ICSD, Crystallography Open Database | Reference patterns for identification & training data |

| Analysis Software | HighScore Plus, MAUD, TOPAS, GSAS-II | Traditional Rietveld refinement & pattern analysis |

| ML Frameworks | XRD-AutoAnalyzer, Bayesian FusionNet, Custom CNNs | Automated phase identification & adaptive control |

| Instrumentation | Benchtop XRD systems with programmable interfaces | Adaptive data collection & closed-loop experimentation |

| Standard Materials | NIST SRM 674a, Corundum, Silicon | Instrument calibration & line profile analysis |

| Computational Resources | GPU clusters, Cloud computing platforms | Training complex neural network models |

Traditional XRD analysis methods face fundamental limitations in addressing the complexity, scale, and pace of modern materials research. Search-Match library techniques fail with novel phases and complex mixtures, while Rietveld refinement demands excessive computational resources and expert intervention for contemporary material systems. Machine learning frameworks for autonomous phase identification represent a transformative approach that directly addresses these limitations through adaptive data acquisition, automated analysis, and robust pattern recognition capabilities. By integrating ML-driven approaches with traditional expertise, researchers can achieve unprecedented throughput, accuracy, and insight in crystalline material characterization, accelerating discovery and development across pharmaceutical, materials, and chemical sciences.

Why Machine Learning? Addressing Data Complexity and High-Throughput Demands

The discovery and development of new functional materials are fundamentally limited by the speed at which their structures can be determined and understood. X-ray diffraction (XRD) has served for decades as the primary technique for crystalline material characterization, but traditional analysis methods are no longer sufficient to handle the data volumes and complexity generated by modern high-throughput experimentation. Manual analysis of XRD patterns requires significant domain expertise in crystallography, thermodynamics, and solid-state chemistry, creating a critical bottleneck in materials development pipelines [8]. This application note examines how machine learning (ML) frameworks are being deployed to overcome these challenges, enabling autonomous phase identification and accelerating the establishment of composition-structure-property relationships.

The core challenges are twofold. First, data complexity arises because powder XRD patterns represent one-dimensional compressions of three-dimensional reciprocal space information, leading to peak overlaps and loss of directional information that complicate interpretation [9]. Second, high-throughput demands emerge from combinatorial synthesis approaches that can generate hundreds to thousands of compositionally varying samples in a single library, making manual analysis impractical and incompatible with autonomous synthesis-characterization-analysis loops [8]. Machine learning addresses both challenges by leveraging pattern recognition capabilities that can identify subtle features in complex datasets and scale to analyze massive data volumes at unprecedented speeds.

The Data Complexity Challenge in XRD Analysis

Information Compression in Powder XRD

Powder X-ray diffraction data presents unique analytical challenges because it compresses three-dimensional crystal structure information into a one-dimensional pattern. This compression leads to inevitable information loss, particularly regarding directional relationships within the crystal lattice. As a result, multiple candidate crystal structures may produce similar diffraction patterns, requiring additional constraints to identify the correct solution [9]. Traditional analysis methods struggle with this inherent ambiguity, especially when analyzing complex multi-phase systems or materials with subtle structural variations.

The complexity extends beyond simple phase identification to advanced material characteristics including lattice parameter changes, crystallographic texture, solid solution behavior, defect structures, and microstructural features [8]. Each of these characteristics influences material properties but requires sophisticated interpretation of sometimes subtle variations in diffraction patterns. For instance, intensity deviations from calculated patterns may indicate preferential orientation or polymorphic phase coexistence, while low-intensity peaks could represent minor phases or merely background noise [8].

Limitations of Traditional Analysis Methods

Conventional XRD analysis methods like Rietveld refinement, while powerful, require expert knowledge to provide reasonable initial crystal structures and refinement parameters [9]. This process demands years of experience and keen insight, creating a significant expertise barrier that limits scalability and reproducibility. Furthermore, these methods typically analyze one pattern at a time, making them incompatible with the data volumes generated by high-throughput experimentation.

Perhaps most importantly, traditional approaches struggle with the "chemical reasonableness" assessment that human experts naturally perform. Experienced specialists integrate knowledge from crystallography, thermodynamics, kinetics, and solid-state chemistry to arrive at physically plausible solutions that may not strictly minimize fitting residuals but better align with materials science principles [8]. Encoding this multifaceted domain knowledge into traditional algorithms has proven exceptionally challenging.

Table 1: Key Data Complexity Challenges in XRD Analysis

| Challenge Category | Specific Manifestations | Impact on Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Information Content | 3D to 1D data compression; peak overlap; intensity variations | Ambiguity in phase identification; multiple candidate solutions |

| Pattern Variations | Peak shifting; broadening; asymmetry; background effects | Difficulties distinguishing phases with similar structures |

| Expert Dependency | Need for "chemical reasonableness" assessment; crystallographic knowledge | Scalability limitations; subjectivity in interpretation |

| Multi-phase Complexity | Overlapping peaks from multiple phases; minor phase detection | Underestimation of phase numbers; inaccurate quantification |

High-Throughput Experimental Demands

The Combinatorial Materials Science Paradigm

Combinatorial synthesis and high-throughput characterization have emerged as powerful approaches to accelerate materials discovery by rapidly screening vast composition spaces. A single combinatorial library may contain hundreds to thousands of compositionally varying samples, enabling efficient mapping of composition-structure-property relationships [8]. This approach has been successfully applied to diverse material systems including oxides [8], metal-organic frameworks [9], and high-entropy alloys [10].

The scale of data generation in these experiments is staggering. For example, a typical combinatorial library may contain 300-500 samples [8], each requiring phase identification, quantification, and structural characterization. At manual analysis rates of even a few patterns per day, comprehensive characterization of a single library could require months of expert effort, completely negating the throughput advantages of combinatorial synthesis. This creates an critical bottleneck that impedes materials innovation across energy, electronics, and manufacturing applications [8].

Autonomous Materials Development Frameworks

The ultimate goal of high-throughput methodologies is the establishment of autonomous materials development systems that integrate synthesis, characterization, and analysis in closed-loop workflows. These systems require automated analysis capabilities that can provide rapid feedback to guide subsequent experimentation [11]. The emergence of robotic laboratories and automated synthesis platforms has further intensified the need for correspondingly automated characterization methods [12].

Recent advances have demonstrated fully autonomous platforms for mapping phase diagrams of biomolecular condensates, which integrate robotic sample production, automated characterization, and active machine learning to guide subsequent experiments [11]. Similar frameworks are being developed for crystalline materials, where the ability to rapidly analyze XRD patterns represents the critical path element in the materials discovery cycle. Without automated XRD analysis, these autonomous systems cannot function effectively.

Table 2: High-Throughput XRD Data Generation Scenarios

| Material System | Library Size | Characterization Challenges | ML Solution Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| V–Nb–Mn oxide | 317 samples | Multiple phases; solid solutions; texture | AutoMapper with thermodynamic constraints [8] |

| Bi–Cu–V oxide | 307 samples | Complex phase identification; substrate interference | Rolling ball background removal; pattern demixing [8] |

| Li–Sr–Al oxide | 50 samples | Laboratory source (unpolarized) differences | Polarization correction; composition constraints [8] |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks | 300,000+ hypothetical structures | Prediction of adsorption properties | iPXRDnet with multi-scale CNN [9] |

Machine Learning Solutions for XRD Analysis

Addressing Data Complexity Through Specialized Architectures

Machine learning approaches to XRD analysis employ specialized architectures designed to handle the particular challenges of diffraction data. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have demonstrated remarkable effectiveness in extracting relevant features from XRD patterns, with multi-scale architectures proving particularly valuable. The iPXRDnet framework employs an Inception module with parallel convolutional kernels of sizes 1, 5, and 23 to extract information at different scales - from individual diffraction points to peak combinations [9]. This multi-scale approach enables the model to capture both fine-grained details and broader pattern characteristics that are essential for accurate phase identification and property prediction.

For enhanced interpretability and uncertainty quantification, Bayesian deep learning approaches are being integrated into XRD analysis pipelines. The Bayesian-VGGNet model incorporates variational inference, Laplace approximation, and Monte Carlo dropout to provide confidence estimates alongside predictions [13]. This is particularly valuable for real-world applications where understanding prediction reliability is as important as the predictions themselves. These models can achieve 84% accuracy on simulated spectra and 75% on external experimental data while simultaneously estimating prediction uncertainty [13].

Scaling Analysis Through Transfer Learning and Data Augmentation

The limited availability of large, labeled experimental XRD datasets has prompted the development of innovative data augmentation and transfer learning strategies. Template Element Replacement (TER) generates virtual structures within known chemical spaces, creating physically-informed training data that enhances model understanding of XRD-structure relationships [13]. This approach has been shown to improve classification accuracy by approximately 5% while providing insights into how models learn spectrum-structure mappings.

Transferability - the ability of models trained on specific data types to generalize to new contexts - represents both a challenge and opportunity for ML-enabled XRD analysis. Research has demonstrated that models trained on single-crystal XRD data can transfer effectively to polycrystalline analysis when trained on multiple orientations [14]. This capability is essential for practical applications where training comprehensive models on every possible material system and experimental condition is infeasible.

Autonomous XRD Analysis Workflow: Integrated machine learning pipeline for high-throughput phase identification.

Experimental Protocols for ML-Enabled XRD Analysis

Automated Phase Mapping Protocol

Purpose: To automatically identify constituent phases and their fractions in high-throughput XRD datasets of combinatorial libraries.

Materials:

- High-throughput XRD dataset with associated composition information

- Candidate phase database (ICDD, ICSD, or Materials Project)

- Computational resources for neural network optimization

Procedure:

- Candidate Phase Identification:

- Collect all relevant candidate phases from crystallographic databases

- Filter entries by chemistry (e.g., oxides for oxide systems)

- Group identical or very similar structures as single candidates

- Eliminate thermodynamically unstable phases (e.g., energy above hull >100 meV/atom)

Data Preprocessing:

- Apply background removal using rolling ball algorithm [8]

- Retain substrate peaks during solving process (do not subtract)

- Normalize patterns to maximum intensity

- Account for X-ray source polarization (synchrotron vs. laboratory)

Optimization-Based Solving:

- Define loss function as weighted sum of XRD fitting quality (Rwp), composition consistency, and entropy regularization [8]

- Use encoder-decoder structure to solve phase fractions and peak shifts

- Incorporate thermodynamic data as constraints

- Implement iterative fitting considering compositionally similar samples

Solution Validation:

- Assess physical reasonableness of solutions

- Verify consistency with phase rule constraints

- Evaluate texture information for major phases

Troubleshooting:

- For difficult multi-phase samples: Use solutions from simpler compositions as initial guesses

- For poor convergence: Adjust weighting factors in loss function

- For physically implausible results: Strengthen thermodynamic constraints

Deep Learning Model Training Protocol

Purpose: To train deep learning models for crystal structure classification from XRD patterns.

Materials:

- SIMPOD dataset or similar XRD database [15]

- Computational resources with GPU acceleration

- Deep learning framework (PyTorch or TensorFlow)

Procedure:

- Data Preparation:

Model Architecture Selection:

Model Training:

- Initialize with pretrained weights when available

- Use cross-validation with multiple folds

- Monitor performance on validation set to prevent overfitting

- Employ learning rate scheduling and early stopping

Model Evaluation:

- Test on held-out experimental data

- Assess uncertainty calibration and confidence estimates

- Perform SHAP analysis for interpretability [13]

Validation:

- Benchmark against traditional methods (Rietveld refinement)

- Test transferability to related material systems [14]

- Verify physical reasonableness of predictions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources for ML-Enabled XRD Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Solutions | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Frameworks | AutoMapper [8]; iPXRDnet [9]; B-VGGNet [13] | Specialized ML architectures for XRD pattern analysis |

| Data Resources | SIMPOD [15]; ICSD; COD; Materials Project | Training data and reference patterns for phase identification |

| Preprocessing Tools | Rolling ball algorithm [8]; min-max scaling [16] | Background correction and data normalization |

| Domain Knowledge Databases | Thermodynamic data [8]; crystallographic constraints | Ensuring physically reasonable solutions |

| Validation Resources | SHAP analysis [13]; uncertainty quantification | Model interpretability and confidence assessment |

Machine learning has transitioned from a promising approach to an essential technology for addressing the intertwined challenges of data complexity and high-throughput demands in XRD analysis. By combining sophisticated neural network architectures with domain-specific knowledge constraints, ML frameworks can now provide automated, physically reasonable phase identification that scales to accommodate combinatorial materials discovery pipelines. The protocols and resources outlined in this application note provide researchers with practical pathways to implement these powerful approaches in their own work, potentially accelerating materials development across diverse technological domains from energy storage to pharmaceutical development. As these methods continue to mature, they promise to unlock increasingly autonomous materials discovery systems that can navigate complex composition spaces with minimal human intervention.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) is a foundational technique in materials science, chemistry, and pharmaceutical development for determining the atomic-scale structure of crystalline materials. The core principle involves illuminating a sample with X-rays and analyzing the resulting diffraction pattern, which serves as a unique fingerprint of the material's crystal structure. For decades, the analysis of these patterns has relied on physics-based models and refinement techniques, such as Rietveld refinement [12]. However, the advent of high-throughput synthesis and characterization has led to an explosion in the volume of XRD data, creating a critical need for faster, more automated analysis methods [12] [17].

Machine learning (ML) now offers a paradigm shift, moving from traditional physics-based analysis to a data-driven approach. Instead of explicitly modeling the physics of diffraction, ML models learn to map the complex features within an XRD pattern directly to material properties, such as phase identity, crystal structure, or microstructural descriptors [18] [14]. This document outlines the core concepts of how ML models interpret XRD patterns, providing application notes and protocols for researchers aiming to integrate these techniques into an autonomous phase identification framework.

From Physics-Based Analysis to Data-Driven Feature Extraction

The Traditional Paradigm of XRD Analysis

Traditional XRD analysis is governed by well-established physical laws. Bragg's Law ((nλ = 2d \sinθ)) defines the relationship between the diffraction angle (θ), the X-ray wavelength (λ), and the spacing between atomic planes (d) [12] [17]. Techniques like Rietveld refinement use these principles to iteratively adjust a theoretical model until it matches the experimental pattern [12]. While powerful, this process is computationally intensive, requires significant expert knowledge, and can be challenging for complex, multi-phase mixtures [18].

The Machine Learning Paradigm

In contrast, ML models treat an XRD pattern primarily as a one-dimensional image or a vector of intensity values [18]. The model's objective is to learn the underlying statistical relationships and patterns within this data that correlate with specific material characteristics. This process can be visualized as a fundamental shift in approach, as shown in the diagram below.

Key Machine Learning Approaches and Their Applications

ML models for XRD analysis can be broadly categorized by their learning approach and primary function. The table below summarizes the predominant methodologies, their key techniques, and applications.

Table 1: Machine Learning Approaches for XRD Data Analysis

| Methodology | Key Techniques | Primary Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supervised Learning | Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [6] [18], Gradient Boosting [19], Ensemble Models [8] | Phase identification & classification [18], Quantifying phase fractions [18], Predicting microstructural descriptors (dislocation density, phase fractions) [14] | Requires large, labeled datasets; Performance depends on data quality and diversity [14]. |

| Unsupervised & Optimization-Based | Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF) [8], Uniform Manifold Approximation (UMAP) [20], Autoencoders [19] | Automated phase mapping [8], Dimensionality reduction, Pattern clustering & visualization [20] | No labeled data needed; Useful for exploring unknown systems; Results may require expert validation. |

| Adaptive & Autonomous Workflows | Integration of CNNs with Class Activation Maps (CAMs) [6], Uncertainty Quantification [6] | Autonomous experiment steering [6], Real-time phase identification in dynamic processes (e.g., battery cycling, solid-state reactions) [6] | Closes the loop between measurement and analysis; optimizes data collection for maximal information gain. |

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Implementing ML for XRD analysis requires a suite of data, software, and computational resources. The following table details the key components of the modern researcher's toolkit.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for ML-Driven XRD Analysis

| Item Name | Type | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Crystallography Open Database (COD) | Data | Open-access repository of crystal structures for generating simulated XRD patterns for model training [12]. |

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) | Data | Comprehensive database of inorganic crystal structures used to curate candidate phases for identification [12] [8]. |

| Pydidas | Software | Python-based tool for automated XRD data processing and analysis, featuring a user-friendly GUI and modular workflow design [21]. |

| GSAS-II | Software | Crystallography software suite used for Rietveld refinement and, in ML contexts, for generating ground-truth labels and identifying artifacts [19]. |

| PyFAI | Software | Core Python library used by many tools (including Pydidas) for high-performance calibration and azimuthal integration of 2D XRD images to 1D patterns [21]. |

| Synthetic XRD Datasets | Data | Large-scale, computer-generated datasets of mixed-phase XRD patterns, crucial for training robust deep learning models for phase identification [18]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Autonomous and Adaptive Phase Identification

This protocol, adapted from the work of Vallon et al., describes a closed-loop system for autonomously identifying phases and steering XRD measurements in real-time, ideal for capturing transient phases in in situ experiments [6].

1. Initialization:

- Equipment Setup: Couple a diffractometer (in-house or synchrotron) to a computing system running an ML model (e.g., XRD-AutoAnalyzer [6]).

- Model Loading: Load a pre-trained CNN model calibrated for the relevant chemical space (e.g., Li-La-Zr-O for battery materials).

2. Rapid Initial Scan:

- Perform a fast, low-resolution XRD scan over a limited angular range (e.g., 2θ = 10° to 60°).

- Feed the acquired pattern directly into the ML model.

3. Confidence Assessment & Decision Loop:

- The model outputs phase predictions with associated confidence scores (0-100%).

- IF confidence for all suspected phases is >50%: Proceed to final reporting.

- IF confidence is <50%: Initiate adaptive rescanning.

- Resampling: Use Class Activation Maps (CAMs) to identify 2θ regions where the diffraction features of the top candidate phases differ most. Rescan these regions with higher resolution (slower scan rate).

- Range Expansion: If ambiguity persists, expand the scan range beyond the initial 60° limit in +10° increments to capture additional distinguishing peaks.

- Iterate this process until the confidence threshold is met or a maximum scan angle (e.g., 140°) is reached.

4. Final Reporting:

- The system outputs the final identified phases and their confidence scores.

The following diagram illustrates this adaptive workflow.

Protocol: Automated Phase Mapping of Combinatorial Libraries

This protocol, based on the "AutoMapper" workflow, is designed for high-throughput analysis of combinatorial XRD datasets to construct phase diagrams [8].

1. Preprocessing of XRD Patterns:

- Input: Collect raw XRD patterns from a combinatorial library (e.g., 300+ samples).

- Background Removal: Process raw data using a rolling ball algorithm or similar, rather than relying on pre-subtracted data, to preserve real experimental features [8].

- Data Scaling: Apply min-max scaling per sample to preserve the relative intensity trends, which are critical for accurate mineral and phase analysis [16].

2. Candidate Phase Identification:

- Database Query: Collect all known phases in the relevant chemical system from databases (ICSD, ICDD).

- Thermodynamic Filtering: Prune the candidate list by removing phases calculated to be highly thermodynamically unstable (e.g., energy above hull >100 meV/atom) to ensure "chemical reasonableness" [8].

3. Optimization-Based Solving:

- Encoder-Decoder Fitting: Use a neural network with an encoder-decoder structure to fit the experimental patterns using the simulated patterns of the candidate phases.

- Loss Function Minimization: The solver minimizes a custom loss function that combines:

- LXRD: The weighted profile R-factor (Rwp) for diffraction pattern fit.

- Lcomp: A constraint ensuring reconstructed phase fractions match the known sample composition.

- Lentropy: An entropy term to prevent overfitting.

- Iterative Refinement: Begin with "easy" samples (1-2 phases) to initialize the model, then solve "difficult" multi-phase boundary samples, using solutions from similar compositions to avoid local minima [8].

4. Output:

- The solver outputs the number, identity, and fraction of phases for each sample in the library, effectively constructing a phase map.

Critical Considerations for Model Implementation

Data Quality and Preprocessing

The performance of ML models is profoundly sensitive to data quality. Inappropriate preprocessing, such as scaling each intensity feature independently, can destroy the relative intensity information that is crucial for phase identification, leading to a 41% increase in prediction error [16]. Correct, sample-wise preprocessing is therefore non-negotiable.

Integration of Domain Knowledge

Purely data-driven models can produce physically unreasonable results. Encoding domain knowledge—such as crystallographic constraints, thermodynamic stability, and composition rules—directly into the model's loss function or candidate selection process is essential for generating trustworthy solutions that experts would accept [12] [8].

Model Transferability and Robustness

A model trained on XRD data from one specific condition (e.g., a single crystal orientation) may not generalize well to new conditions (e.g., a different orientation or polycrystalline sample) [14]. Ensuring model robustness requires training on diverse datasets that encompass a wide range of material states, crystallographic orientations, and potential artifacts (e.g., textured rings or single-crystal spots) [14] [19].

The Essential Role of Crystallographic Databases (ICSD, COD, MP) for Training

In the field of machine learning (ML) for autonomous phase identification from X-ray diffraction (XRD) data, crystallographic databases form the essential foundation upon which all models are built. These databases provide the large-scale, structured data required to train, validate, and test ML algorithms to recognize the intricate relationship between diffraction patterns and crystal structures [12]. The shift from traditional analysis methods, such as Rietveld refinement, to data-driven approaches has been catalyzed by an explosion in available crystal structure data, driven by high-throughput synthesis and characterization methodologies [12]. This application note details the critical role of major databases—specifically the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD), Crystallography Open Database (COD), and Materials Project (MP)—in developing robust ML frameworks, providing researchers with protocols for their effective utilization and quantitative comparisons of their distinctive characteristics.

Compendium of Key Crystallographic Databases

The landscape of crystallographic databases is diverse, with each major repository offering distinct advantages for ML training. The selection of an appropriate database directly influences model performance, generalizability, and applicability to specific research domains such as inorganic materials or metal-organic frameworks.

Table 1: Key Crystallographic Databases for ML Training

| Database | Primary Content Focus | Total Structures | Data Source & Curation | Access Model | Notable ML Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) | Inorganic compounds, ceramics, minerals, metals, intermetallics [22] [23] | >240,000 (2021) [23] | Expert-curated experimental & theoretical data; quality-checked since 1913 [22] [24] | Licensed access [25] | High-quality, critically-evaluated data; symmetry-based descriptors for ML [24] |

| Crystallography Open Database (COD) | Organic, inorganic, metal-organic compounds & minerals [25] [26] | >376,000 [25] | Community-driven; experimental structures from various sources & digitization [25] | Open access [25] | Diverse data types (X-rays, electrons, neutrons); uses standard CIF format [25] |

| Materials Project (MP) | Theoretical inorganic crystal structures & calculated properties [27] | Not explicitly stated | High-throughput computational calculations based on density functional theory (DFT) [27] | Open access | Consistent, theoretically calculated properties; large volume of uniform data |

The Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) is recognized for its high-quality, critically-evaluated data, with its first records dating back to 1913 [22] [23]. It specializes in completely identified inorganic crystal structures and includes over 240,000 structures as of 2021, with approximately 12,000 new entries added annually [22] [23]. Its rigorous quality control makes it a trusted resource for training ML models requiring high-fidelity data [27].

The Crystallography Open Database (COD) is a community-built, open-access resource containing over 376,000 entries [25]. Its strength lies in its diversity, encompassing organic, metal-organic, and inorganic compounds, and collecting results from various diffraction experiments (X-rays, electrons, neutrons) [25]. This heterogeneity can be advantageous for training more generalizable models.

The Materials Project (MP) is a database of computed materials properties and crystal structures, generating data through high-throughput computational methods [27]. It provides a large, consistent dataset of theoretical structures and properties, which is valuable for screening materials and training models where uniform computational data is preferable to heterogeneous experimental data.

Quantitative Database Comparison for ML Suitability

Selecting a database for ML requires considering statistical factors beyond simple entry counts. The distribution of data across crystal classes and the balance of the dataset significantly impact model performance.

Table 2: Statistical Analysis of Database Composition for ML Training

| Database | Temporal Coverage | Growth Rate (Structures/Year) | Notable Compositional Biases | Reported ML Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICSD | 1913 to present [23] | ~12,000 [22] | Heavy skew toward heavily populated space groups; more balanced class distribution than COD [27] | Superior for space group prediction due to balanced distributions [27] |

| COD | 1915 to present [25] | Not explicitly stated | Less balanced space group distribution vs. ICSD, affecting generalizability [27] | Models can be outperformed by those trained on more balanced databases [27] |

| Materials Project | Contemporary | Not explicitly stated | Contains theoretical structures; data distribution not explicitly detailed | Good performance for space group prediction, generally behind ICSD [27] |

A critical study comparing databases for space group prediction via composition-based classifiers found that data-abundant repositories like COD do not necessarily provide the best models, even for heavily populated space groups [27]. Instead, classification models trained on databases with more balanced distributions of representative classes, such as ICSD and the Pearson Crystal Database, generally outperform their data-richer counterparts [27]. This highlights that data quality and balance are as important as data quantity for effective ML model training.

Experimental Protocols for ML Model Development

Protocol A: Phase Identification in Multiphase Inorganic Compounds

This protocol, adapted from a study published in Nature Communications, details the use of a deep convolutional neural network (CNN) for identifying constituent phases in complex mixtures [18].

Key Research Reagents & Data Solutions:

- ICSD Data: Source for 170 inorganic compounds within the Sr-Li-Al-O quaternary system to simulate reference XRD patterns [18].

- Synthetic XRD Dataset: A combinatorially mixed dataset of 1,785,405 synthetic powder XRD patterns generated from the 170 base compounds [18].

- Deep Learning Framework: TensorFlow or PyTorch for building the CNN model.

- Experimental Validation Set: 100 real experimental XRD patterns measured in the laboratory for Li₂O-SrO-Al₂O₃ and SrAl₂O₄-SrO-Al₂O₃ ternary mixtures [18].

Procedure:

- Dataset Generation: Simulate powder XRD patterns for each of the 170 candidate compounds from the ICSD. Subsequently, create a massive training dataset by combinatorially mixing these simulated patterns to generate synthetic XRD patterns for multiphase mixtures [18].

- Model Architecture Selection: Build a CNN model. The referenced study employed architectures with two (CNN2) and three (CNN3) convolutional layers, using hyperparameters determined on a trial-and-error basis [18].

- Model Training: Train the CNN model on the large synthetic dataset. The study reported a validation accuracy reaching nearly 100% [18].

- Model Testing: Evaluate the trained model using a hold-out test set of synthetic patterns (100,000 patterns) and a separate set of real experimental XRD patterns (100 patterns) [18].

- Performance Assessment: The model achieved nearly perfect test accuracy (~99.6% - 100%) on synthetic data and 97.33% - 100% on real experimental data, correctly identifying phases in milliseconds—a task that takes hours via traditional Rietveld refinement [18].

Protocol B: Crystal System Classification via CrystalMELA

This protocol utilizes the open-access Crystallography Open Database (COD) to train a versatile ML platform for crystal system classification [26].

Key Research Reagents & Data Solutions:

- POW_COD Database: An SQLite relational database containing entries generated from the CIF files in the COD, used as the source of crystal structures [26].

- CrystalMELA Platform: A web-based ML platform supporting multiple models (Random Forest, Convolutional Neural Network, Extremely Randomized Trees) [26].

- Synthetic PXRD Patterns: Over 280,000 theoretical powder XRD patterns computed from the crystal structures in POW_COD [26].

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Extract crystal structures from the POW_COD database, which is derived from the COD. Compute theoretical PXRD patterns for these structures to create a large training set [26].

- Model Training and Cross-Validation: Train multiple ML models (RF, CNN, ExRT) available on the CrystalMELA platform using the simulated PXRD data. Perform tenfold cross-validation to assess performance [26].

- Performance Benchmarking: The platform achieved a crystal system classification accuracy of approximately 70%, which improved to over 90% when considering the Top-2 prediction accuracy [26].

- Independent Validation: Test the trained models on an independent set of experimental data from 110 previously published crystal structures, confirming the model's robustness and practical utility [26].

Workflow Visualization: From Databases to Autonomous Identification

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for developing an ML framework for autonomous phase identification, synthesizing the protocols above.

Crystallographic databases are indispensable for advancing machine learning in autonomous XRD analysis. The ICSD provides high-quality, curated data ideal for robust model development, the COD offers vast, diverse, and open data for generalizable applications, and the Materials Project contributes consistent computational data for theoretical studies. The experimental protocols demonstrate that the strategic use of these databases, whether for building complex deep learning models for phase identification or multi-model platforms for crystal system classification, can achieve high accuracy and drastically reduce analysis time. Future development will likely focus on improving data quality and availability, enhancing model interpretability, and integrating more domain knowledge and physical constraints into ML models to further accelerate the discovery and characterization of novel materials [17].

Architectures in Action: Implementing ML Models for Phase Identification

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for End-to-End Phase Classification

Within the broader framework of developing a machine learning system for autonomous phase identification from X-ray diffraction (XRD) data, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have emerged as a powerful tool for end-to-end phase classification. Traditional XRD analysis, including Rietveld refinement, requires significant expert intervention, is time-consuming, and struggles to scale with the high-throughput data generated by modern synchrotron facilities and automated synthesis laboratories [12] [28] [29]. CNNs address these limitations by learning directly from XRD patterns, treating them as one-dimensional images to automatically identify constituent phases in multiphase mixtures with minimal human input [18] [17]. This capability is pivotal for accelerating the establishment of composition-structure-property relationships in materials science and drug development.

CNN Performance in Phase Classification: Quantitative Benchmarks

CNNs trained on synthetic XRD data demonstrate high accuracy in classifying crystal structures and identifying phases in complex mixtures, with performance validated against experimental data. The following table summarizes key quantitative results from recent studies.

Table 1: Performance of CNN Models for XRD Phase Classification and Related Tasks

| Study Focus | Dataset Description | Model Architecture | Key Results and Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiphase Identification [18] | 1.78 million synthetic patterns; 170 inorganic compounds in Sr-Li-Al-O system. | Custom CNN (CNN2, CNN3) | - ~100% accuracy on simulated test data.- ~100% accuracy on real experimental ternary mixtures. |

| Crystal System & Space Group Classification [28] | 1.2 million synthetic patterns from ICSD; evaluated on experimental RRUFF data. | Generalized Deep Learning Model (CNN-based) | - 86.9% accuracy for crystal system on RRUFF data.- 75.6% accuracy for space group on RRUFF data. |

| Space Group Classification [13] | Virtual & real structure data (e.g., perovskites); 30 structure types. | Bayesian-VGGNet | - 84% accuracy on simulated spectra.- 75% accuracy on external experimental data. |

| End-to-End Crystal Structure Determination [30] | MP-20 dataset (inorganic materials). | PXRDGen (Integration of CNN/XRD Encoder) | - 96% matching rate for crystal structures (with 20 samples).- RMSE approaches Rietveld refinement precision limits. |

| Phase Quantification [29] | Synthetic data for multi-mineral systems (e.g., calcite, gibbsite). | Custom CNN with Dirichlet loss | - 0.5% mean error on synthetic test sets.- 6% mean error on experimental data for 4-phase mixtures. |

Experimental Protocols for CNN-Based Phase Classification

Protocol 1: Phase Identification in Multiphase Inorganic Compounds

This protocol, adapted from a study achieving near-perfect accuracy, details the procedure for identifying constituent phases in multiphase inorganic powder samples [18].

- Objective: To train a CNN model for the identification of constituent phases in unknown multiphase mixtures within a specific compositional pool (e.g., Sr-Li-Al-O).

- Materials and Data Preparation:

- Candidate Phase Selection: Identify all known inorganic compounds within the target quaternary system from crystallographic databases (e.g., ICSD, COD).

- Synthetic XRD Pattern Generation: Simulate powder XRD patterns for each of the 170 candidate phases. Parameters: Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å), 2θ range from 5° to 90°.

- Combinatorial Mixing: Generate a large-scale training dataset (e.g., ~1.78 million patterns) by combinatorically mixing the simulated patterns of the 170 pure phases to create virtual multiphase mixtures.

- CNN Model Training:

- Architecture: Implement a deep CNN with multiple convolutional layers for feature extraction, followed by fully connected layers for classification.

- Hyperparameters: Use a dropout rate of 50% to prevent overfitting. Determine optimal kernel size and pooling strategy empirically.

- Training: Train the model on the synthetic dataset, using a hold-out validation set to monitor loss and accuracy.

- Validation with Experimental Data:

- Prepare real powder samples of ternary mixtures (e.g., Li₂O-SrO-Al₂O₃) with known compositions.

- Acquire experimental XRD patterns of these validation samples.

- Feed the experimental patterns into the fully trained CNN model and analyze the output phase predictions.

- Expected Outcomes: The trained model should achieve high accuracy (>99%) on synthetic test data and nearly perfect accuracy on well-prepared real experimental mixtures, correctly identifying all constituent phases in seconds [18].

Protocol 2: Generalized Crystal System and Space Group Classification

This protocol outlines a method for building a robust and generalizable CNN model for classifying crystal systems and space groups from diverse XRD patterns, including experimental data [28].

- Objective: To develop a generalized CNN model for classifying the crystal system (7-class) and space group (230-class) of a material from its XRD pattern, with high accuracy on both synthetic and experimental data.

- Materials and Data Preparation:

- Data Sourcing: Retrieve a large number of Crystallographic Information Files (CIFs) from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD). Filter out incomplete or duplicated structures.

- Synthetic Data Generation with Augmentation:

- Use the CIF files to generate synthetic XRD patterns.

- Create multiple synthetic datasets by varying instrumental parameters (e.g., Caglioti parameters to model peak broadening) and implementing different noise profiles.

- Combine these datasets to create a large, augmented training dataset (e.g., 1.2 million patterns) that mimics the variability in real experimental data.

- CNN Model Training and Optimization:

- Architecture Design: Design a CNN architecture whose components are optimized to learn physics-based features, such as relative peak locations and intensities informed by Bragg's law.

- Expedited Learning: Employ transfer learning or fine-tuning techniques to further adapt the model's expertise to specific experimental conditions.

- Evaluation on Unseen Data:

- Test the model's performance on three distinct evaluation datasets:

- Experimental RRUFF dataset: Contains high-quality experimental patterns from minerals.

- Materials Project (MP) dataset: Contains synthetic patterns of materials with enhanced electromagnetic properties, not seen during training.

- Lattice Augmentation dataset: Contains synthetic cubic patterns with artificially altered lattice constants to test the model's reliance on relative peak positions rather than absolute values.

- Test the model's performance on three distinct evaluation datasets:

- Expected Outcomes: A highly generalized model achieving >85% accuracy on crystal system classification and >75% accuracy on space group classification for experimental XRD patterns from the RRUFF database [28].

Table 2: Key Resources for CNN-Based XRD Phase Classification

| Resource Name/Type | Function in the Workflow | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Crystallographic Databases | Source of ground-truth crystal structures for simulating training data. | Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [28], Crystallography Open Database (COD) [15], Materials Project (MP) [13]. |

| XRD Simulation Software | Generates synthetic powder XRD patterns from CIF files. | Dans Diffraction Python package [15], proprietary software integrated with databases. |

| Public XRD Datasets | Provide benchmarks for training and testing model generalizability. | SIMPOD (Simulated Powder X-ray Diffraction Open Database) [15], RRUFF experimental dataset [28]. |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | Provide the programming environment to build, train, and validate CNN models. | PyTorch [15], TensorFlow. |

| Automated Synthesis & Characterization | Generates high-throughput experimental data for validation and closed-loop discovery. | Robotic laboratories for solution processing [12], composition-graded thin-film libraries via co-sputtering [12]. |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for autonomous phase classification, from data generation to model application, as described in the protocols.

Figure 1: End-to-End CNN Workflow for XRD Phase Classification

The workflow for applying machine learning to XRD phase mapping involves integrating synthetic data generation with model training and experimental validation. The following diagram details the data flow within a specific automated phase mapping solver, "AutoMapper," which incorporates domain knowledge.

Figure 2: Automated Phase Mapping Solver Logic

The accurate and rapid identification of crystalline phases from X-ray diffraction (XRD) data is a cornerstone of materials science research and drug development. Traditional methods, such as Search/Match versus reference libraries and Rietveld refinement, are increasingly challenged by modern complex materials, including multi-phase samples, high-entropy alloys, and nanostructured systems [2]. These conventional approaches often struggle with peak overlap, experimental noise, and the computational burden of analyzing large datasets, creating a critical need for more advanced analytical frameworks [2].

Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a transformative solution to these challenges. While Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have shown significant promise in analyzing XRD patterns, the field is rapidly advancing beyond these architectures. This document details the application of three sophisticated ML frameworks—Transformer Encoders, Hybrid CNN-Multilayer Perceptron (CNN-MLP) models, and Variational Autoencoders (VAE)—for autonomous phase identification. These frameworks enable researchers to overcome specific limitations of traditional methods and CNNs, facilitating high-throughput screening and the discovery of novel materials [2].

Comparative Analysis of ML Architectures for XRD

Selecting the appropriate machine learning architecture is paramount for the success of an autonomous phase identification project. The table below provides a comparative analysis of traditional and advanced ML methods across key performance criteria relevant to high-throughput materials discovery.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Traditional and Machine Learning-Based Methods for XRD Analysis [2]

| Method | Technique | Time | Multi-Phase Handling | Interpretation | Scalability | Highlight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Rietveld | Physical Model Fitting | Slow | Low | Structural insights | Low | Highly reliable for detailed crystallographic analysis when time permits. |

| Search/Match Libraries | Database Matching | Moderate | Low | Low interpretability | Moderate | Fast phase identification for well-documented materials; limited for novel or complex systems. |

| CNN / Deep Learning | Feature Learning | Fast | High | Black-box | High | Excels at deconvoluting overlapping peaks and handling noise—ideal for high-throughput screening. |

| T-encoder | Self-Attention | Moderate | Moderate | Black-box | Moderate | Captures global contextual relationships via self-attention but demands large training sets. |

| CNN–MLP | Hybrid Learning | Fast | High | Black-box | High | Integrates XRD features with compositional data for accurate property regression and classification. |

| Variational Autoencoder (VAE) | Unsupervised Learning | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate (latent insights) | High | Provides dimensionality reduction and clustering to explore latent structural trends and novel phases. |

Architectural Deep Dive and Protocols

Transformer Encoders (T-encoder)

Concept and Workflow: Transformer Encoders adapt the self-attention mechanism, renowned in natural language processing, to the domain of XRD analysis [2]. This architecture treats an XRD pattern not just as a sequence of intensities, but as a set of interrelated features. The pattern is first segmented into patches or individual data points. The self-attention mechanism then computes attention scores between all patches, allowing the model to learn long-range dependencies and global context within the diffraction pattern [2]. This is particularly advantageous for identifying complex relationships between distant peaks that may be diagnostically important for phase identification but are often missed by models with a more localized receptive field.

Diagram 1: Transformer Encoder Workflow for XRD Analysis

Experimental Protocol:

Data Preparation:

- Source: Curate a dataset of XRD patterns (1D arrays of intensity vs. 2θ) with corresponding phase labels. Datasets can be theoretical (from crystallographic databases like the ICDD PDF-5+, which contains over 1.1 million entries [31]) or experimental.

- Preprocessing: Apply standard preprocessing steps: background subtraction, normalization to a maximum intensity of 1, and interpolation to a common 2θ axis.

- Patching: Segment the preprocessed 1D pattern into a sequence of overlapping or non-overlapping patches. Each patch represents a local region of the diffraction pattern.

Model Training:

- Architecture: Implement a Transformer Encoder model. The input is the sequence of embedded patches. The core of the model consists of multiple multi-head self-attention layers and feed-forward layers.

- Hyperparameters: This architecture requires careful tuning. Key parameters include the number of encoder layers (e.g., 6-12), the number of attention heads (e.g., 8-12), and the dimensionality of the model.

- Training: Use a cross-entropy loss function and an Adam optimizer. Due to the high data demand of Transformers, ensure a large and diverse training dataset (tens of thousands of patterns) to prevent overfitting [2].

Validation:

- Evaluate the model on a held-out test set of experimental patterns not seen during training.

- Report standard metrics: Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-score for multi-phase identification.

Hybrid CNN-MLP for Property Regression

Concept and Workflow: The Hybrid CNN-MLP architecture is designed for tasks that require integrating structural information from XRD patterns with non-structural, vector-based data, such as chemical composition [2]. This model synergistically combines the strengths of two neural networks: a CNN that excels at extracting hierarchical spatial features from the full-profile XRD pattern, and an MLP that is well-suited for processing tabular data. By merging these feature streams, the model can establish powerful correlations between the microstructural signatures in the diffraction data and macroscopic material properties, such as bandgap energy or formation energy [2].

Diagram 2: Hybrid CNN-MLP Architecture for Joint XRD and Compositional Analysis

Experimental Protocol:

Data Preparation:

- XRD Data: Follow the preprocessing steps outlined in Section 3.1.

- Compositional Data: Encode the chemical composition of each sample as a vector. One-hot encoding of elements is a common and effective approach [32].

Model Training:

- Architecture:

- CNN Branch: Design a 1D CNN to process the XRD pattern. This typically includes convolutional layers (with ReLU activation), max-pooling layers, and a final flattening layer.

- MLP Branch: Design a separate MLP to process the one-hot encoded composition vector.

- Fusion: Concatenate the output feature vectors from the CNN and MLP branches. Feed this combined vector into a final MLP (the fusion network) for the regression or classification task.

- Training: Use a Mean Squared Error (MSE) loss for regression tasks or cross-entropy for classification, with an Adam optimizer.

- Architecture:

Validation:

- Validate the model's ability to predict material properties on a held-out test set. Report metrics like R² score and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for regression tasks.

Variational Autoencoders (VAE)

Concept and Workflow: Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) provide an unsupervised learning approach for analyzing XRD data [2]. A VAE learns to compress high-dimensional XRD patterns into a low-dimensional, continuous latent space and then reconstruct the original input from this compressed representation. The key differentiator from a standard autoencoder is that the VAE learns the parameters (mean and variance) of a probability distribution in the latent space. This forces the latent space to be structured and continuous, which enables powerful operations like generating new, plausible XRD patterns and smoothly interpolating between different phases. In the context of phase identification, the latent space can be clustered to reveal hidden patterns, identify novel phases, or detect anomalies [2].

Diagram 3: Variational Autoencoder (VAE) Framework for Unsupervised XRD Exploration

Experimental Protocol:

Data Preparation:

- Use a large collection of XRD patterns, which do not necessarily require phase labels. This makes VAEs particularly useful for exploring unlabeled data.

- Apply standard preprocessing (background subtraction, normalization).

Model Training:

- Architecture: The VAE consists of an encoder and a decoder network, typically implemented with fully connected or 1D convolutional layers.

- Loss Function: The training objective is to minimize a combined loss function: the reconstruction loss (e.g., Mean Squared Error between input and output) and the KL divergence loss, which regularizes the latent space to approximate a standard normal distribution.

- Training: Use an Adam optimizer, carefully balancing the two loss components with a weighting factor (β) if necessary.

Analysis and Application:

- Dimensionality Reduction: Once trained, the encoder can be used to project any XRD pattern into the low-dimensional latent space (e.g., 2D or 3D for visualization).

- Clustering: Apply clustering algorithms (e.g., k-means, DBSCAN) to the latent vectors to identify groups of patterns corresponding to distinct phases.

- Anomaly Detection: Patterns with a high reconstruction error or that lie in sparse regions of the latent space can be flagged as potential anomalies or novel phases.

Successful implementation of the ML frameworks described above relies on both software tools and data resources. The following table details key components of the research toolkit.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for ML-Based XRD Analysis

| Item Name | Type | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| ICDD PDF-5+ Database [31] | Reference Database | Provides over 1.1 million reference patterns for phase identification and serves as a critical source for generating theoretical training data for ML models. |

| JADE Pro Software [31] | Analysis Software | A comprehensive XRD analysis platform useful for data preprocessing, traditional Search/Match, Rietveld refinement, and pattern visualization, which can complement ML workflows. |

| XRDanalysis Software [33] | Analysis Software | A next-generation software package featuring automated workflow creation, batch processing, and Rietveld analysis, facilitating the preparation of large datasets for ML. |

| Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) Framework [32] | ML Model | An alternative graph-based ML approach that represents XRD patterns as graphs of interconnected peaks, showing high precision (0.990) in phase identification tasks. |

| Stacked Ensemble Classifier [34] | ML Model | A robust ML methodology that combines multiple models (e.g., a meta-classifier like Gradient Boosting) to improve predictive accuracy and generalization, achieving up to 99.04% accuracy in classification tasks. |

| Theoretical XRD Pattern Simulator | Computational Tool | Software (e.g., within JADE or VESTA) that generates theoretical diffraction patterns from CIF files, enabling massive-scale synthetic dataset generation for training data-hungry models like Transformers. |

| One-Hot Encoded Composition Vectors [32] | Data Preprocessing | A method for representing material composition as a binary vector, enabling the Hybrid CNN-MLP model to effectively learn from both structural and chemical information. |

Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) is a fundamental technique for determining the crystal structure of crystalline materials. However, the identification and quantification of constituent phases in multiphasic inorganic compounds remain a significant challenge [12]. Conventional methods, such as Rietveld refinement, require extensive expert intervention, are time-consuming, and lack the throughput required for modern materials discovery pipelines [28] [29].

The advent of deep learning (DL) offers a paradigm shift, enabling automated, rapid, and accurate analysis of XRD patterns. This case study explores a specific deep-learning protocol for multiphase identification, detailing its methodology, performance, and practical implementation. This protocol is situated within a broader machine-learning framework for autonomous materials characterization, demonstrating how data-driven approaches can accelerate research and development in fields ranging from solid-state chemistry to pharmaceutical development [18] [35].

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Core Deep-Learning Protocol

The featured protocol employs a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) trained predominantly on synthetic data to identify phases in multiphase inorganic compounds [18] [36].

- Data Generation: The foundation of this approach is the creation of a massive, labeled dataset of synthetic XRD patterns.

- Reference Crystal Structures: The process begins with 170 inorganic compounds from the Sr-Li-Al-O quaternary system, selected from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [18].

- Pattern Simulation: The powder XRD pattern for each pure compound is simulated.

- Combinatorial Mixing: To create multiphase mixtures, the simulated patterns of the 170 single phases are combinatorically mixed. This process generated a final dataset of 1,785,405 synthetic XRD patterns, each representing a unique multiphase mixture [18].

- Data Augmentation and Variability: To ensure model robustness, the synthetic data incorporates variations in experimental conditions. This includes applying different Caglioti parameters (affecting peak shape) and adding noise to better mimic real-world data [28].

- Model Architecture and Training: A convolutional neural network (CNN) is designed to process the 1D XRD patterns. The model is trained on the synthetic dataset, learning to map the complex features of an XRD pattern to its constituent phases. The training uses a hold-out validation set to monitor performance and prevent overfitting [18].

The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end workflow for the deep-learning-based phase identification protocol.

Application to Experimental Data