Automated SCF Convergence for Robust Geometry Optimization in Computational Drug Discovery

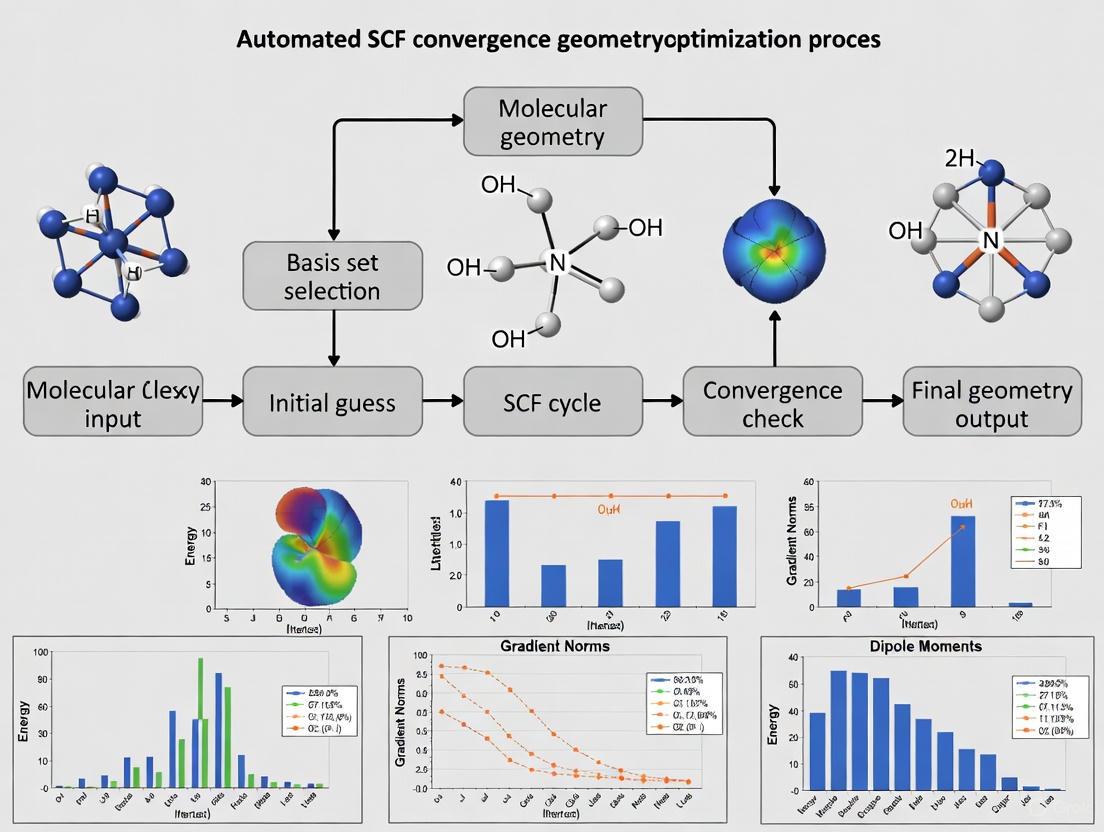

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on automating Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence to achieve reliable and efficient molecular geometry optimization.

Automated SCF Convergence for Robust Geometry Optimization in Computational Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on automating Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence to achieve reliable and efficient molecular geometry optimization. It covers foundational SCF principles and common convergence challenges, explores advanced algorithms and their implementation in major quantum chemistry packages, details systematic troubleshooting protocols for difficult systems, and establishes validation frameworks for benchmarking performance. By integrating these strategies, scientists can enhance the accuracy and throughput of computational workflows critical for biomolecular modeling, ligand-receptor interaction studies, and materials design.

Understanding SCF Convergence: The Engine of Quantum Chemical Geometry Optimization

The Critical Role of SCF Convergence in Determining Molecular Structure and Energetics

Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence is a foundational step in quantum chemical calculations, directly determining the accuracy and reliability of computed molecular structures and energies. Failure to achieve convergence halts workflows and jeopardizes research outcomes. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting strategies, framed within automated SCF convergence research, to help scientists efficiently resolve these critical computational challenges.

Understanding SCF Convergence: Core Concepts and FAQs

What is SCF Convergence and Why is it Critical?

The SCF procedure iteratively solves for the electronic structure of a molecule until the energy and electron density stop changing significantly. Successful convergence is the prerequisite for any subsequent calculation of molecular properties, reaction pathways, or spectroscopic predictions. Within automated workflows, robust convergence is essential for high-throughput screening and machine learning potential generation, where thousands of calculations must run without manual intervention [1].

What Are the Physical Reasons for SCF Non-Convergence?

Several physical scenarios in a molecular system can prevent the SCF procedure from converging [2]:

- Small HOMO-LUMO Gap: When the highest occupied and lowest unoccupied molecular orbitals are close in energy, even small changes in the electron density can cause electrons to "slosh" back and forth between them, leading to oscillatory behavior [2].

- Charge Sloshing: In systems with high polarizability (often related to a small HOMO-LUMO gap), a small error in the Kohn-Sham potential can cause a large distortion in the electron density. This can create a feedback loop where the potential becomes increasingly erroneous, leading to divergence [2].

- Incorrect Initial Electron Density Guess: A poor starting point for the electron density can lead the optimization down a path to divergence, especially for systems with unusual charge/spin states or metal centers [2].

- Incorrect Symmetry: Imposing artificially high symmetry on a molecule can sometimes force a degenerate electronic state with a zero HOMO-LUMO gap, making convergence impossible [2].

Troubleshooting Guide: A Structured Approach

Adopt a step-by-step methodology to diagnose and resolve SCF convergence issues. The following workflow provides a logical escalation path.

Step 1: Fundamental Checks

Before adjusting complex parameters, verify the basics.

- Inspect Molecular Geometry: Ensure interatomic distances and angles are chemically sensible. Geometries with nearly dissociated atoms or severely strained bonds are challenging to converge [3].

- Verify Charge and Multiplicity: An incorrect spin state can prevent convergence, especially for transition metal complexes [2].

Step 2: Improve the Initial Electron Density Guess

A high-quality initial guess can dramatically improve SCF stability.

- Use Advanced Guess Methods: Switch from the default core Hamiltonian to extended Hückel (

guess=huckel), SAD (Superposition of Atomic Densities), or fragment-based guesses if available in your software [4]. - Reuse Converged Wavefunctions: Perform a quick calculation with a simpler method or basis set, then use the resulting wavefunction as the initial guess (

guess=read) for the target calculation [4]. - Leverage Machine Learning: Emerging ML models can predict accurate initial electron densities, significantly reducing SCF cycles [5].

Step 3: Adjust SCF Algorithm Parameters

Tweak the SCF solver's behavior to stabilize convergence.

- Apply Level Shifting: Artificially increase the energy of virtual orbitals to reduce mixing with occupied orbitals. For example, in Gaussian, use

SCF=vshift=300(values of 300-500 are common). This affects only the convergence process, not the final results [4]. - Modify Electron Density Mixing: Reduce the mixing parameter (

AMIXandBMIXin VASP;Mixingin BAND) for a more conservative, stable update of the density between cycles [6]. - Change the Algorithm: Switch between DIIS, QC (Quadratic Converger), or the MultiSecant method. If DIIS causes oscillations, try

SCF=NoDIISorSCF=QC[4] [6].

Step 4: Increase Numerical Accuracy

Inaccurate numerical evaluation of integrals can cause noise that prevents convergence.

- Use a Finer Integration Grid: For DFT calculations, specify a finer numerical integration grid (e.g.,

int=ultrafinein Gaussian). This is particularly important for meta-GGA and hybrid functionals, and for systems with diffuse functions [4]. - Tighten SCF Convergence Criterion: Counter-intuitively, using a tighter convergence criterion (e.g.,

SCF%Convergence 1e-7or1e-8) can sometimes help avoid oscillations near the solution by providing a more consistent gradient [7]. - Improve Basis Set Quality: Increase the basis set numerical quality (e.g., to

GoodorVeryGood), which often improves the accuracy of computed forces and the stability of the SCF procedure [7].

Step 5: Advanced System-Specific Strategies

- Use Fermi Broadening: Applying a finite electronic temperature (

SCF=Fermi) can occasionally help by smearing orbital occupations [4]. Be aware this moves the calculation away from the pure ground state. - Two-Step Optimization for Challenging Systems: For difficult systems like magnetic metals or those requiring meta-GGA functionals, a multi-step approach is effective [8]:

- Converge with a simpler functional (e.g., PBE).

- Restart using the resulting wavefunction with a more advanced functional (e.g., MBJ) and a conservative solver setting (

ALGO=Allin VASP,TIME=0.1).

Specialized Protocols for Challenging Systems

Protocol for Systems with a Small HOMO-LUMO Gap

Systems with small gaps (e.g., transition metal complexes, open-shell species, or distorted geometries) are prone to charge sloshing and orbital flipping [2].

Detailed Methodology:

- Diagnose: Check the HOMO-LUMO gap after the first SCF cycle. If it is less than ~0.5 eV, the system is in the high-risk category.

- Apply Level Shifting: This is the most direct remedy. Use

SCF=vshift=500in Gaussian or an equivalent keyword to increase the HOMO-LUMO gap artificially during the convergence process [4]. - Use Fermi Smearing or Fractional Occupations: Set

ISMEAR = -1(VASP) orSCF=Fermi(Gaussian) to assign fractional occupations to orbitals near the Fermi level, which can dampen oscillations [8]. - Lock Occupations: If oscillations are due to electrons flipping between specific orbitals, use the

OCCUPATIONSblock (ADF) or the Maximum Overlap Method (MOM) to freeze the occupation pattern [7] [5].

Protocol for Excited State and Solvation Calculations

Calculations involving excited states (e.g., ΔSCF) or implicit solvation models are inherently less stable [3] [5].

Detailed Methodology:

- Converge in Gas Phase First: Perform a single-point energy calculation in the gas phase for the target electronic state. For excited states, this may require specialized algorithms like MOM or cDFT [5].

- Use the Gas-Phase Wavefunction as a Guess: Read the converged gas-phase wavefunction as the initial guess for the solvated or excited-state calculation (

guess=read) [4]. - Tighten SCF and Grid Settings: When using a Polarizable Continuum Model (PCM), combine it with a finer integration grid (

int=ultrafine) to minimize numerical noise that can disrupt convergence [4].

Protocol for Magnetic Systems (LDA+U)

Magnetic systems, particularly with LDA+U, are prone to convergence issues due to delicate energy balances between spin configurations [8].

Detailed Methodology:

- Step 1 - Preliminary Spin-Polarized Calculation: Run a spin-polarized calculation without LDA+U (

ICHARG=12,ALGO=Normal) to get a reasonable initial spin density. - Step 2 - Stable Solver with Reduced Time Step: Restart from Step 1's output, switching to a more stable solver (

ALGO=Allin VASP) and reducing the effective time step (TIME=0.05). - Step 3 - Introduce LDA+U: Restart again from Step 2's output, now adding the LDA+U parameters while keeping the stable solver and small time step [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

The table below catalogs key "research reagents" – computational parameters and tools – used to troubleshoot SCF convergence.

| Research Reagent | Function & Purpose | Example Usage / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Level Shift | Increases virtual orbital energies, widening the HOMO-LUMO gap to prevent oscillation. | SCF=vshift=400 (Gaussian). A primary tool for small-gap systems [4]. |

| Fermi Smearing | Smears electron occupation, stabilizing metallic and small-gap systems. | ISMEAR = -1 (VASP), SCF=Fermi (Gaussian). Introduces small entropy term [8]. |

| DIIS/QC Algorithm | DIIS accelerates convergence; QC is slower but more robust for difficult cases. | Switch to SCF=QC if SCF=DIIS fails [4]. |

| Fine Integration Grid | Increases accuracy of numerical integrals, reducing noise. | int=ultrafine (Gaussian). Critical for DFT with diffuse functions [4]. |

| Density Mixing Parameters | Controls how the new Fock matrix is mixed with the old. Reducing mixing stabilizes convergence. | AMIX = 0.02 (VASP), SCF{Mixing 0.05} (BAND) for conservative updates [6]. |

| Advanced Initial Guess | Provides a better starting electron density, reducing SCF cycles. | guess=huckel, or guess=read from a simpler calculation [4]. |

| Solvation Model | Mimics solvent effects but can introduce convergence instability. | Converge in gas phase first, then use guess=read for PCM calculation [4]. |

| GTP-gamma-S 4Li | GTP-gamma-S 4Li, MF:C10H12Li4N5O13P3S, MW:563.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| N-Acetyl-N-methyl-L-leucine | N-Acetyl-N-methyl-L-leucine|C9H17NO3|187.24 g/mol |

Advanced Diagnostics and Automation

Interpreting SCF Output for Diagnostics

Automated scripts can parse SCF output logs to classify the failure mode and suggest remedies.

- Oscillatory Behavior: If the energy difference between cycles alternates in sign with a large amplitude (>1x10â»Â³ Hartree), it suggests a small HOMO-LUMO gap or charge sloshing. Prescription: Apply level shifting or reduce density mixing [2] [4].

- Steady Drift: If the energy decreases/increases steadily over many cycles, the initial geometry may be far from equilibrium or the initial guess is very poor. Prescription: Check geometry, improve the initial guess, or simply allow more cycles [7].

- Trailing Convergence: The energy change is consistently small but just above the convergence threshold. This is often due to numerical noise. Prescription: Tighten the integration grid or SCF convergence criteria [5] [2].

Towards Full Automation: Adaptive SCF Protocols

For fully automated workflows (e.g., in high-throughput virtual screening), adaptive protocols that modify parameters on-the-fly are essential. The logic for such a system can be visualized as follows:

This automated troubleshooting guide provides a systematic framework for researchers to diagnose and resolve SCF convergence issues, enhancing the reliability of automated computational workflows in drug development and materials science.

Troubleshooting Guides

How can I resolve SCF energy oscillations?

SCF energy oscillations, where the total energy jumps between two or more values instead of converging, indicate that the iterative process is trapped in a limit cycle [9]. This is a non-linear phenomenon common in systems with complex electronic structures, such as open-shell transition metal compounds or metallic systems [10] [6].

Diagnosis and Resolution Protocol:

- Diagnose the Pattern: First, examine the last ten or more SCF iterations. Oscillations are confirmed if the energy jumps back and forth between distinct values around a specific point, while the energy gradient shows little change [7].

- Apply Damping: Use more conservative settings to dampen the oscillations. This can be achieved by decreasing the SCF mixing parameter or using dedicated keywords like

SlowConvorVerySlowConv[10] [6]. - Change the SCF Algorithm: If the default DIIS method is oscillating, switch to a more robust algorithm. Geometric Direct Minimization (GDM) is highly recommended as a fallback, as it properly accounts for the geometry of the orbital rotation space [11]. Alternatively, second-order convergence methods like the Trust Radius Augmented Hessian (TRAH) can be employed [10].

- Adjust DIIS Parameters: For pathological cases, increasing the number of Fock matrices stored in the DIIS subspace (

DIISMaxEq) can improve extrapolation. For very difficult systems, values between 15 and 40 (default is 5) may be necessary [10]. - Improve Numerical Accuracy: Increase the grid quality for numerical integration and tighten the SCF convergence criterion to reduce numerical noise that can hinder convergence [7] [10].

Table: Resolution Strategies for SCF Oscillations

| Strategy | Specific Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Algorithm Change | Switch from DIIS to GDM or TRAH [11] [10]. | More stable, monotonic convergence. |

| Damping | Use ! SlowConv or reduce SCF%Mixing to 0.05 [10] [6]. |

Reduced energy jumps between cycles. |

| DIIS Enhancement | Increase DIISMaxEq to 15-40 and/or set directresetfreq to 1 [10]. |

Improved extrapolation and removal of numerical noise. |

| Guess Improvement | Use MORead to import orbitals from a converged, simpler calculation (e.g., BP86/def2-SVP) [10]. |

A starting point closer to the solution, reducing initial instability. |

The following workflow provides a systematic method for diagnosing and resolving SCF oscillations:

How do I stabilize SCF convergence for systems with small HOMO-LUMO gaps?

Systems with small or vanishing HOMO-LUMO gaps, such as metals or diradicals, are prone to SCF convergence issues because tiny changes in geometry can cause significant changes in the electronic structure (orbital repopulation) [7].

Diagnosis and Resolution Protocol:

- Verify the Ground State: Perform a single-point calculation and check that you have the correct electronic ground state. Confirm that the spin polarization value is correct. For open-shell systems, try calculating high-spin states to see if they are lower in energy [7].

- Increase SCF Accuracy: Tighten the SCF convergence criterion (e.g., to

1e-8) and increase the numerical quality (e.g., to "Good") to ensure forces and energies are calculated with high precision [7]. - Lock Orbital Occupations: If electronic structure changes between steps are the problem, manually freeze the number of electrons per irreducible representation using an

OCCUPATIONSblock. This prevents orbital repopulation that disrupts convergence [7]. - Use Finite Electronic Temperature: In geometry optimizations, applying a small finite electronic temperature (e.g.,

Convergence%ElectronicTemperature) can smear orbital occupations, making the initial SCF cycles easier. This temperature can be automated to decrease as the optimization proceeds and the geometry nears convergence [6]. - Employ Robust Algorithms: Use second-order convergence algorithms like TRAH or GDM, which are designed to handle difficult convergence landscapes [10] [11].

Table: Strategies for Small HOMO-LUMO Gap Systems

| Strategy | Specific Action | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Increase Precision | Set NumericalQuality Good and SCF converge 1e-8 [7]. |

Ensures accurate gradients despite near-degeneracy. |

| Control Occupations | Use an OCCUPATIONS block to freeze electrons per symmetry [7]. |

Prevents erratic orbital flipping during optimization. |

| Smear Occupations | Use Convergence%ElectronicTemperature (e.g., 0.01 Hartree) [6]. |

Stabilizes initial SCF cycles by damping occupation changes. |

| Advanced Algorithms | Enable AutoTRAH or use SCF_ALGORITHM GDM [10] [11]. |

Provides stronger convergence for near-degenerate systems. |

What are the best practices for modeling charge-transfer systems?

Charge-transfer (CT) systems, characterized by donor-bridge-acceptor (D-σ-A) architectures, require careful treatment to accurately model their electronic and optical properties, which are highly sensitive to geometry and external fields [12].

Modeling and Optimization Protocol:

- Thorough Initial Optimization: Optimize molecular structures to a minimum on the potential energy surface for multiple spin states (closed-shell singlet, open-shell singlet, triplet). This ensures the correct electronic state is identified [12].

- Investigate Electric Field Response: CT systems are used in devices under electric fields. Re-optimize geometries under an applied electric field (e.g., from -0.30 V/Ã… to 0.50 V/Ã…) to study the response of the HOMO-LUMO gap, orbital energies, and total dipole moment [12].

- Analyze Frontier Orbitals: Calculate the HOMO-LUMO gap and inspect the spatial distribution of these orbitals. In a proper CT system, HOMO should be localized on the donor and LUMO on the acceptor moiety [12].

- Ensure Method Consistency: Use the same functional and basis set across all calculations for a given system to ensure result comparability. For example, employ the B3LYP functional with the 6-31G(d) basis set for geometry optimization and subsequent property calculations [12].

Table: Key Properties to Calculate for Charge-Transfer Systems

| Property | Calculation Method | Significance in CT Systems |

|---|---|---|

| HOMO-LUMO Gap | DFT single-point energy calculation on optimized geometry [12]. | Indicates intrinsic conductivity; a small gap facilitates charge transfer. |

| Orbital Localization | Visualize HOMO and LUMO isosurfaces [12]. | Confirms charge-transfer character (HOMO on donor, LUMO on acceptor). |

| Dipole Moment | Calculate from electron density [12]. | Measures molecular polarity; can be strongly affected by an external field. |

| Field-Dependent Gap | Re-optimize geometry under a range of electric fields [12]. | Models device operation; gap narrowing under field indicates improved conduction. |

The following workflow outlines the key steps for modeling charge-transfer systems, from setup to analysis:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My geometry optimization does not converge, but the SCF seems fine. What should I check? A1: If the SCF is converging but the geometry optimization is stuck, the problem likely lies in the accuracy of the calculated energy gradients (forces). To improve gradient accuracy, you can:

- Increase the numerical quality (e.g.,

NumericalQuality Good). - Use an exact density keyword or select "Exact" for the density in the XC-potential.

- Tighten the SCF convergence criteria [7]. Additionally, check if constraints are breaking the molecular symmetry and consider switching to delocalized internal coordinates, which often converge faster than Cartesian coordinates [7].

Q2: Why are my optimized bond lengths significantly too short? A2: Excessively short bond lengths, particularly for heavy elements, often indicate a basis set problem. Two common causes are:

- Onset of Pauli variational collapse: This can occur when using the Pauli relativistic method with small frozen cores and large basis sets.

- Overlapping frozen cores: As atoms approach, overlapping frozen cores cause missing repulsive terms, leading to spurious "core collapse." The best solution is to abandon the Pauli method and use the ZORA relativistic approach instead. If you must use Pauli, apply larger frozen cores or reduce the flexibility of the basis set's s- and p-functions [7].

Q3: What should I do if my SCF calculation converges to the wrong state? A3: This can happen with a poor initial guess. To guide the calculation to the desired state:

- Use the Maximum Overlap Method (MOM), which enforces occupation of a continuous set of orbitals to prevent flipping between different states [11].

- Manually construct a guess by converging a closed-shell, oxidized, or reduced state of the system, and then use those orbitals (

MORead) as the starting point for the target calculation [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for SCF and Geometry Optimization Research

| Tool / 'Reagent' | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| GDM Algorithm | A robust geometric direct minimization SCF algorithm [11]. | Primary algorithm for restricted open-shell systems or fallback when DIIS fails. |

| TRAH-SCF | A robust second-order SCF converger (Trust Radius Augmented Hessian) [10]. | Automated fallback for difficult systems (e.g., open-shell transition metals). |

| DIISMaxEq | Input parameter controlling the number of Fock matrices in DIIS extrapolation [10]. | Set to 15-40 for pathological cases to improve convergence stability. |

| Finite Electronic Temperature | Smears orbital occupations via an electronic temperature (kT in Hartree) [6]. | Stabilizing initial SCF cycles in geometry optimizations of metallic systems. |

| OCCUPATIONS Block | Input block to manually fix orbital occupations [7]. | Preventing unwanted orbital repopulation in systems with small HOMO-LUMO gaps. |

| B3LYP/6-31G(d) | A standard DFT functional and basis set combination [12]. | Benchmark studies and geometry optimization of organic charge-transfer systems. |

| Fmoc-N-Me-D-Glu-OH | Fmoc-N-Me-D-Glu-OH, MF:C21H21NO6, MW:383.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 5-azido-2H-1,3-benzodioxole | 5-azido-2H-1,3-benzodioxole, MF:C7H5N3O2, MW:163.13 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the primary advantage of using a Superposition of Atomic Densities (SAD) guess over a Core Hamiltonian guess? The SAD guess is typically much better than starting from a core Hamiltonian. It is often easier to implement and provides a superior starting point for the SCF procedure, leading to faster and more reliable convergence, especially for open-shell systems. [13]

Q2: My SCF calculation fails to converge, even with a SAD guess. What are the next steps? When facing persistent convergence issues, you can:

- Use more conservative SCF settings, such as decreasing the mixing parameter or reducing the DIIS subspace size. [6]

- Try an alternative algorithm like the MultiSecant method, which has a similar cost per iteration to DIIS, or the LISTi method. [6]

- Improve numerical accuracy by increasing the integration grid quality or improving the density-fitting precision, as poor numerical quality can cause convergence failure. [6]

Q3: Can a good initial guess reduce computational time in geometry optimizations? Yes, significantly. A high-quality initial guess can lead to faster SCF convergence in each geometry step. Furthermore, within a geometry optimization, you can use automations to start with a looser SCF convergence criterion and a higher electronic temperature when the nuclear gradients are large, tightening these parameters as the geometry approaches its minimum. [6]

Q4: How can machine learning models contribute to initial guess generation? Machine learning models, such as the SchNOrb framework, can be trained to predict the Hamiltonian matrix in an atomic orbital basis. This predicted Hamiltonian can then be used to generate molecular orbitals, providing an excellent starting point for the SCF procedure and drastically reducing the number of SCF iterations required. [14]

Q5: Are there open-source libraries available to help with SCF convergence? Yes. Libraries like OpenOrbitalOptimizer provide reusable, state-of-the-art SCF solvers, implementing various convergence accelerators like DIIS, EDIIS, ADIIS, and the Optimal Damping Algorithm (ODA). These can be integrated into existing quantum chemistry codes to improve robustness. [15]

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: SCF Calculation Fails to Converge

Issue: The self-consistent field procedure oscillates or diverges, failing to find a solution.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

- Step 1: Check the Initial Guess

- Symptom: Large initial energy error or erratic behavior from the first iteration.

- Action: Switch from the core Hamiltonian guess to a Superposition of Atomic Densities (SAD). [13] For systems with heavy elements, ensure the frozen core approximation is not hindering convergence; using a small or no frozen core may help. [6]

Step 2: Adjust SCF Algorithm Parameters

- Symptom: Convergence stalls after initial improvement or oscillates.

- Action: Tighten the SCF convergence parameters. Implement more robust algorithms via input settings, for example:

Alternatively, switch to a different algorithm like

SCF%Method MultiSecant. [6]

Step 3: Improve Numerical Precision

- Symptom: Many iterations occur after the calculation is "halfway" converged.

- Action: Increase the

NumericalQualitysetting. For systems with heavy elements, ensure the Becke integration grid quality is sufficient. Using only one k-point can also be a source of problems in periodic systems. [6]

Step 4: For Geometry Optimizations - Use Adaptive Settings

- Symptom: SCF convergence is problematic during the early stages of a geometry optimization when the nuclear gradients are still large.

- Action: Use engine automations to dynamically adjust SCF parameters based on the optimization progress. This allows for a higher electronic temperature and looser SCF convergence at the start, refining them as the geometry converges. [6] Example automation block:

Problem: Geometry Optimization Does Not Converge

Issue: The geometry optimization exceeds the maximum number of steps without meeting the convergence criteria.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

- Prerequisite: Ensure the SCF convergence is robust at each geometry step. Unstable SCF can cause noisy gradients that prevent geometry convergence. [6]

- Improve Gradient Accuracy: If SCF is stable but geometry is not, the gradients may be numerically inaccurate. Increase the basis set integration quality (e.g.,

RadialDefaults%NR 10000) and setNumericalQuality Good. [6] - Check for Saddle Points: The optimization may have converged to a transition state instead of a minimum. Enable

Properties%PESPointCharacter Trueand setGeometryOptimization%MaxRestartsto a value >0 (e.g., 5) withUseSymmetry False. This allows the optimizer to automatically detect saddle points and restart with a displacement along the imaginary mode to find the minimum. [16]

Comparison of Initial Guess Methodologies

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of different initial guess methods.

| Method | Core Principle | Typical Use Case | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core Hamiltonian | Neglects electron-electron interactions, using only the one-electron part of the Hamiltonian. | Simple systems, default fallback. | Simple to compute. | Often a poor guess, can lead to slow SCF convergence or failure. [13] |

| Superposition of Atomic Densities (SAD) | Sums pre-computed atomic electron densities to form the initial molecular density. | General purpose for both closed-shell and open-shell systems. | More physically realistic than core Hamiltonian, easier and often better than a minimal basis calculation. [13] | Effectiveness can depend on the atomic configurations and potentials used. [17] |

| Machine Learning (e.g., SchNOrb) | A deep neural network predicts the Hamiltonian matrix in an atomic orbital basis from the molecular structure. | Suitable for organic molecules; promising for inverse design and property-focused optimization. | Provides a near-quantitative guess, can speed up SCF by orders of magnitude; gives access to electronic properties. [14] | Requires training data and model; performance may vary for molecules far from training set. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a SAD Guess with Fitted Potentials

This methodology outlines an efficient approach to implement the SAD guess in Gaussian-basis codes using error function fits to fully numerical atomic radial potentials. [17]

- Atomic Potential Calculation: For each element, perform fully numerical density functional calculations (e.g., at the exchange-only LDA level on top of Hartree-Fock densities) to obtain spherically symmetric atomic potentials.

- Potential Fitting: Fit the fully numerical radial potentials using a linear combination of error functions. This allows the potential to be expressed in a form compatible with Gaussian-basis integral evaluation.

- Integration: Precompute and report the fitting coefficients for the entire periodic table. These coefficients can be used in any quantum chemistry code to construct the initial guess Fock matrix in terms of standard two-electron integrals.

- Application: For a new molecule, the initial guess is formed by summing the fitted atomic potentials for all atoms in the system.

Protocol 2: Using a Machine-Learned Hamiltonian as an Initial Guess

This protocol uses the SchNOrb deep learning framework to generate a high-quality initial guess for the SCF calculation. [14]

- Model Training:

- Data Generation: Create a dataset of organic molecules with pre-computed quantum chemical properties (Hamiltonian and overlap matrices) at a chosen level of theory.

- Architecture: Employ the SchNOrb architecture, which extends an atomistic neural network (SchNet) to represent the electronic Hamiltonian.

- Feature Construction: Build symmetry-adapted pairwise features for atom pairs to represent the Hamiltonian matrix blocks, ensuring rotational invariance and covariance.

- Prediction:

- Input: The 3D molecular structure is fed into the trained SchNOrb model.

- Output: The model predicts the full Hamiltonian matrix (H) in the local atomic orbital basis.

- SCF Restart:

- The predicted Hamiltonian matrix is used to solve the generalized eigenvalue equation (Hc = εSc) to obtain an initial set of molecular orbitals and eigenvalues.

- This ML-predicted wavefunction is then used as the starting point for the conventional SCF procedure, significantly reducing the number of iterations required to reach convergence.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for selecting and applying an initial guess methodology within an automated SCF convergence framework.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key software and algorithmic "reagents" essential for experiments in automated SCF convergence.

| Item | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| LibXC | A library of exchange-correlation functionals. | Provides standardized, portable implementations of density functionals for DFT calculations, "unbundling" DFT development. [5] |

| OpenOrbitalOptimizer | A reusable open-source C++ library for SCF solvers. | Implements standard algorithms (DIIS, EDIIS, ADIIS, ODA) to accelerate SCF convergence; can be integrated into legacy codes. [15] |

| SchNOrb | A deep neural network for predicting molecular wavefunctions. | Generates a quantum-mechanically informed initial guess for the Hamiltonian, drastically reducing SCF iterations and enabling inverse design. [14] |

| Superposition of Atomic Potentials (SAP) | An efficient method for generating initial guesses via fitted atomic potentials. | Provides a robust and systematically improvable starting density for SCF calculations in Gaussian-basis codes. [17] |

| Engine Automations (AMS) | Dynamically adjusts SCF parameters during a geometry optimization. | Maintains SCF stability by using looser criteria at the start of an optimization and tighter criteria near convergence. [6] |

| N3-methylbutane-1,3-diamine | N3-Methylbutane-1,3-diamine | N3-Methylbutane-1,3-diamine (CAS 41434-26-8) is a chemical compound for research use only. It is not for human or animal consumption. |

| N-Acetyl-3-hydroxy-L-valine | N-Acetyl-3-hydroxy-L-valine |

The Direct Inversion in the Iterative Subspace (DIIS) algorithm, developed by Peter Pulay, is one of the most successful and widely used convergence acceleration techniques in electronic structure calculations [18] [11] [19]. Within the context of automated Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence for geometry optimization research, DIIS addresses a fundamental challenge: the slow convergence or outright failure of traditional SCF iterative methods, particularly for chemically complex systems like transition metal complexes or molecules with small HOMO-LUMO gaps [10] [20]. The core innovation of DIIS lies in its approach to extrapolation. Instead of using only the most recent Fock matrix to generate the next guess, DIIS constructs a new Fock matrix as a linear combination of all previous Fock matrices in the current iterative subspace [18] [21]. The coefficients for this linear combination are chosen not arbitrarily, but through a constrained minimization procedure that aims to produce an extrapolated Fock matrix with the smallest possible error, thereby driving the SCF procedure toward convergence more rapidly and reliably than simple iteration [11] [19]. This makes it an indispensable component in automated workflows seeking to minimize user intervention and maximize computational efficiency in quantum chemistry studies relevant to drug development.

Mathematical Foundation of DIIS

The DIIS algorithm is built upon a key property of the exact SCF solution: at convergence, the density matrix (P) and the Fock matrix (F) must commute with the overlap matrix (S). This commutator relationship defines the fundamental error metric for the procedure [18] [11].

The Error Vector and Extrapolation

During the SCF cycles, before self-consistency is achieved, a non-zero error vector, ei, can be defined for each iteration _i [18]: ei = S**PiFi - FiP_iS

The central idea of DIIS is to generate an improved guess for the next Fock matrix, F*, as a linear combination of m previous Fock matrices [18] [21]: F* = Σ cj Fj

The coefficients cj_ are determined by minimizing the norm of the corresponding extrapolated error vector, ⟨e*|e*⟩, under the constraint that the coefficients sum to unity (Σ c_j = 1) [18] [21]. This ensures the conservation of the total number of electrons [21].

The DIIS System of Equations

The minimization problem leads to a system of linear equations that can be represented in matrix form [18] [21]:

Where B is a symmetric matrix with elements Bij = ⟨ei | ej⟩, c is the vector of coefficients, and λ is the Lagrange multiplier associated with the constraint Σ cj = 1 [21]. This system is solved using standard linear algebra techniques, such as the LAPACK DGESV routine, to obtain the coefficients _cj_ [21].

DIIS Workflow and Implementation

The DIIS algorithm integrates into the SCF procedure as a sophisticated extrapolation step. The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and decision points within a typical DIIS-accelerated SCF cycle.

SCF Cycle with DIIS Acceleration

Step-by-Step Protocol

- Initialization: Begin standard SCF iterations. For the first few cycles (e.g., 2-5), proceed without DIIS to build an initial set of Fock and error vectors [20].

- Error Vector Calculation: For iteration i, after constructing the Fock matrix Fi and density matrix Pi, compute the error vector ei = S**PiFi - FiP_iS [18] [21].

- Vector Storage: Store the current Fi and ei. Most implementations limit the number of stored vectors (e.g., 5-15) to manage memory and avoid ill-conditioning of the B matrix. When the subspace is full, older vectors are typically replaced, either by the oldest vector or the one with the largest error norm [18] [21].

- DIIS Extrapolation: Once a sufficient number of vectors (e.g., m ≥ 2) are stored, construct the B matrix and solve the DIIS linear equations to obtain the coefficients cj_ [21].

- Fock Matrix Generation: Form the extrapolated Fock matrix F* = Σ cj Fj [21].

- Orbital Update: Diagonalize F* to obtain a new coefficient matrix, construct a new density matrix, and continue the SCF cycle [21].

- Convergence Check: The SCF procedure is considered converged when the largest element of the latest error vector falls below a predefined cutoff threshold [18].

Convergence Criteria and Thresholds

Convergence in SCF calculations is assessed using multiple criteria to ensure the wavefunction is stable and self-consistent. Different quantum chemistry packages offer predefined levels of convergence stringency, which internally set a group of individual thresholds.

Standard SCF Convergence Criteria

Table 1: Standard SCF convergence criteria and their meanings.

| Criterion | Description | Typical Default Value (Single Point) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TolE / SCF_CONVERGENCE | Change in total energy between iterations [11] [22]. | 10â»âµ to 10â»â¶ E_h [11] [22] | ||||

| TolErr / DIIS Error | Maximum element of the DIIS error vector ( | e | ) [18] [22]. | 10â»âµ a.u. [18] | ||

| TolMaxP | Maximum change in density matrix elements [22]. | 10â»âµ to 10â»â¶ [22] | ||||

| TolRMSP | Root-mean-square change in density matrix elements [22]. | 10â»â¶ to 10â»â· [22] |

Predefined Convergence Settings in ORCA

Table 2: Comparison of selected convergence criteria (TolE in E_h) for different predefined settings in ORCA [22].

| Setting | TolE | TolMaxP | TolRMSP | TolErr | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loose | 1 × 10â»âµ | 1 × 10â»Â³ | 1 × 10â»â´ | 5 × 10â»â´ | Initial geometry steps, large systems |

| Medium | 1 × 10â»â¶ | 1 × 10â»âµ | 1 × 10â»â¶ | 1 × 10â»âµ | Standard single-point energies |

| Tight | 1 × 10â»â¸ | 1 × 10â»â· | 5 × 10â»â¹ | 5 × 10â»â· | Geometry optimizations, frequency analysis [18] [11] |

| Extreme | 1 × 10â»Â¹â´ | 1 × 10â»Â¹â´ | 1 × 10â»Â¹â´ | 1 × 10â»Â¹â´ | Benchmarking, high-precision work |

For geometry optimizations and subsequent frequency calculations, tighter convergence thresholds (e.g., TightSCF in ORCA or SCF_CONVERGENCE=8 in Q-Chem) are mandatory to ensure accurate and reliable forces and second derivatives [18] [11] [22].

Troubleshooting DIIS Convergence Failures

Despite its power, DIIS can fail or converge slowly. The following table outlines common issues, their diagnostic signatures, and recommended solutions.

Common DIIS Problems and Solutions

Table 3: Troubleshooting guide for DIIS convergence failures in automated SCF protocols.

| Problem | Diagnostic Signs | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Slow Convergence | Steady but very slow decrease in energy and error. | Increase DIIS_SUBSPACE_SIZE (e.g., from 15 to 25-40) [18] [10]. Use a more robust algorithm like Geometric Direct Minimization (GDM) or TRAH as a fallback [11] [10]. |

| Oscillations | Energy and error norms cycle between values without improving. | Use damping (SlowConv in ORCA) [10]. Reduce the DIIS mixing parameter [6] [20]. Employ level-shifting to separate occupied and virtual orbital energies [10] [19]. |

| Ill-Conditioning | DIIS procedure produces unreasonable coefficients or crashes. | Reset the DIIS subspace (often automatic) [18] [11]. Replace the oldest vector or the vector with the largest error [21]. |

| False Convergence | DIIS error is small, but energy is not converged (e.g., due to error vector cancellation in unrestricted calculations). | Use DIIS_SEPARATE_ERRVEC = TRUE (Q-Chem) to handle alpha and beta error vectors separately [18]. Tighten the energy-based convergence criterion TolE [22]. |

| Pathological Systems | Failure on systems like open-shell transition metals, large clusters, or systems with diffuse basis sets. | Combine SlowConv with a large MaxIter and increased DIISMaxEq [10]. Use electron smearing to treat near-degenerate states [20]. Read in orbitals from a converged, simpler calculation (MORead) [10]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Computational Reagents

This section details essential "research reagents" – the key input parameters and algorithms – used to control and fine-tune the DIIS process in automated SCF research.

Essential DIIS Control Parameters

Table 4: Key parameters for controlling DIIS performance in automated SCF convergence.

| Parameter/Reagent | Function | Typical Default & Range |

|---|---|---|

| DIISSUBSPACESIZE (Q-Chem) / DIISMaxEq (ORCA) | Controls the number of previous Fock/error vectors used for extrapolation [18] [10]. | Default: 5-15. Range: 10-40 for difficult cases [18] [10]. |

| Mixing / DIIS%DiMix (ADF/BAND) | The fraction of the new, extrapolated Fock matrix used to update the density for the next cycle. Lower values are more stable [6] [20]. | Default: ~0.1-0.2. Range: 0.01-0.3 [6] [20]. |

| SCF_CONVERGENCE (Q-Chem) / TolErr (ORCA) | The convergence threshold for the maximum element of the DIIS error vector [18] [22]. | Default (SP): 10â»âµ a.u. Tight: 10â»â· to 10â»â¸ a.u. [18] [22]. |

| LevelShift | Artificially raises the energy of virtual orbitals to reduce occupied-virtual mixing, stabilizing convergence [10] [19]. | Value: 0.1 - 0.5 E_h [10]. |

| 2-Bromoethane-1-sulfonamide | 2-Bromoethane-1-sulfonamide|C2H6BrNO2S | 2-Bromoethane-1-sulfonamide (C2H6BrNO2S). A versatile alkyl halide and sulfonamide building block for research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 4-(Quinazolin-2-yl)phenol | 4-(Quinazolin-2-yl)phenol, MF:C14H10N2O, MW:222.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: Why does DIIS sometimes converge to a lower energy than expected, and is this desirable? DIIS has a noted tendency to "tunnel" through barriers in wavefunction space, often leading it to the global minimum energy solution rather than a local minimum. This occurs because the density matrix during DIIS iterations is not strictly idempotent until convergence. For most purposes, finding the global minimum is highly desirable, but researchers should be aware that this might bypass a physically expected local minimum [18] [11].

Q2: In an automated geometry optimization, how should SCF convergence criteria be managed?

It is often efficient to use a dual-level strategy. In the initial optimization steps, when geometries are poor and forces are large, looser SCF convergence (e.g., LooseSCF) can be used to save time. As the optimization approaches the minimum and forces become small, the criteria should be tightened (e.g., TightSCF) to ensure accurate gradients and a reliable final geometry [22] [6]. Some codes allow this automation within the optimization block [6].

Q3: My calculation is oscillating wildly in the first few iterations. Should I use DIIS immediately?

No. Starting DIIS too early can exacerbate initial instabilities. It is recommended to perform a number of initial iterations (e.g., 5-30, controlled by Cyc in ADF) using simple damping or without any acceleration to allow the wavefunction to equilibrate before activating the more aggressive DIIS extrapolation [10] [20].

Q4: What are the main alternatives if DIIS fails completely? Robust fallback algorithms are crucial for automated workflows. Geometric Direct Minimization (GDM) is a highly recommended option that respects the curved geometry of the orbital rotation space [11]. Trust-Region Augmented Hessian (TRAH) or other second-order methods are powerful but more computationally expensive alternatives that can converge pathological cases where DIIS fails [10]. Many modern codes like ORCA can automatically switch to these methods when DIIS struggles [10].

Impact of SCF Stability on Geometry Optimization Pathways and Final Results

This guide examines the critical relationship between Self-Consistent Field (SCF) stability and geometry optimization outcomes. When the SCF procedure fails to converge or produces unstable solutions, it directly compromises the accuracy of calculated energy gradients, leading to flawed optimization pathways and physically meaningless final geometries. Understanding this interplay is fundamental for reliable computational research in drug development and materials science.

Troubleshooting Guides

SCF Convergence Failure: Diagnosis and Solutions

Problem: The SCF procedure fails to converge within the default number of cycles, preventing geometry optimization from proceeding or producing invalid results.

Diagnosis Checklist:

- Monitor Energy Behavior: Examine how the energy changes over the latest iterations. Consistent energy changes in one direction suggest the optimization is progressing but needs more time, while oscillations indicate underlying stability issues [7].

- Check HOMO-LUMO Gap: A small HOMO-LUMO gap (often <0.05 eV) is a primary physical cause of convergence problems, leading to orbital occupation switching or "charge sloshing" [2].

- Verify Initial Guess Quality: Poor initial density guesses, particularly for systems with unusual charge/spin states or metal centers, can prevent convergence [2].

- Inspect Geometry Changes: During optimization, check if bonds are elongating or breaking abnormally, which creates challenging SCF problems [3].

Solution Strategies:

Table: SCF Convergence Solutions and Their Applications

| Solution Method | Typical Settings/Values | Applicable Scenarios | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level Shifting [4] | SCF=vshift=300~500 |

Small HOMO-LUMO gaps (e.g., transition metal complexes) | Increases virtual orbital energy; doesn't affect final results. |

| Improved Mixing [6] | SCF%Mixing 0.05, DIIS%Dimix 0.1 |

Metallic systems, slabs, difficult convergence cases | More conservative mixing stabilizes convergence. |

| Alternative Algorithms [6] | SCF%Method MultiSecant, DIIS%Variant LISTi |

When standard DIIS fails | Different convergence characteristics. |

| Fermi Broadening [4] | SCF=Fermi |

Systems with small band gaps, metallic character | Introduces finite electronic temperature. |

| Tightened Integration [4] | int=ultrafine, acc2e=12 |

Calculations with diffuse functions, Minnesota functionals | Higher numerical accuracy at increased computational cost. |

| Initial Guess Improvement [4] | guess=huckel, guess=read |

Problematic initial guesses (e.g., for open-shell systems) | Calculate cation/closed-shell system first for difficult anions/open-shell systems. |

Advanced Protocol: For challenging optimizations where the system evolves from a poor to a refined geometry, implement engine automations that dynamically adjust SCF parameters [6]:

This protocol starts with a higher electronic temperature and looser SCF criteria when gradients are large (initial optimization), then tightens them as the geometry approaches convergence.

Geometry Optimization Failure Due to SCF Instability

Problem: Geometry optimization fails to converge or converges to unrealistic structures with artificially short bonds, distorted angles, or incorrect symmetry due to underlying SCF instabilities.

Diagnosis Checklist:

- Verify Gradient Accuracy: Inaccurate forces/energy gradients from poorly converged SCF lead optimization astray [6].

- Check for Numerical Issues: Insufficient integration grids or basis set problems cause numerical noise that corrupts gradients [7] [2].

- Identify Basis Set Problems: Too diffuse basis functions can cause linear dependence; too large frozen cores can cause unrealistically short bonds ("core collapse") [7].

- Monitor Dihedral Angles: Near-180° angles can cause optimizer instability if they develop during optimization (rather than being present initially) [7].

Solution Strategies:

Table: Geometry Optimization Solutions for SCF-Induced Problems

| Solution Approach | Implementation Examples | Targeted Problem |

|---|---|---|

| Increase Gradient Accuracy [7] [6] | NumericalQuality Good, RadialDefaults NR 10000, SCF converge 1e-8 |

Noisy gradients from SCF instability |

| Coordinate System Change [23] | coordsys cartesian (instead of default redundant internals) |

Failed optimizations in internal coordinates |

| Improved Initial Hessian [23] | InHess Almloef, InHess Read (from lower-level calculation) |

Poor optimization steps from bad initial guess |

| Constraint Management [7] | Remove unnecessary constraints or restart optimization | Constraint-induced symmetry breaking |

| Basis Set Adjustment [7] | Use smaller frozen cores, add confinement, switch to ZORA (relativistic) | Core overlap issues, variational collapse |

Advanced Protocol for Organometallic Systems: For period 5/6 metal complexes exhibiting SCF/optimization failures [24]:

- First attempt optimization in gas phase without solvation

- Use smaller basis sets for initial optimization, then

guess=readfor final calculation [4] - For solvated systems, gradually introduce solvent model after initial gas-phase optimization

- Consider alternative functionals less prone to convergence issues

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My geometry optimization oscillates between two energy values without converging. What does this indicate about SCF stability?

This typically indicates a small HOMO-LUMO gap causing orbital occupation switching [2]. The SCF oscillates between two different orbital occupation patterns, producing different energy landscapes at each geometry step. Solutions include applying level shifting (SCF=vshift=400), using Fermi broadening, or verifying the correct spin state and electronic configuration.

Q2: Why does my optimized structure show unrealistically short bond lengths?

Artificially short bonds often indicate basis set problems exacerbated by SCF issues [7]. With Pauli relativistic methods, this may signal variational collapse (solved by switching to ZORA). Alternatively, large frozen cores that overlap at short distances miss repulsive terms, causing "core collapse." Use smaller frozen cores and ensure sufficient basis set quality.

Q3: How can I distinguish between SCF convergence problems and genuine geometry optimization failures?

Monitor the SCF energy behavior at fixed geometry. If single-point calculations at the current geometry fail to converge, the problem is primarily SCF-related. If SCF converges properly but optimization still fails, examine optimization parameters (coordinate system, constraints, initial Hessian). The workflow below illustrates this diagnostic process.

Q4: My optimization fails specifically when using solvation models. Is this SCF-related?

Yes, solvation models significantly affect the SCF potential [3] [24]. Try converging the SCF in gas phase first, then reading the wavefunction as initial guess for solvated calculation (guess=read) [4]. For PCM calculations, ensure sufficient integration grid quality and verify the solute cavity definition doesn't create numerical instability.

Q5: What SCF stabilization methods are safe for geometry optimization without affecting final results?

Level shifting (SCF=vshift) only affects convergence by raising virtual orbital energies and doesn't alter final converged results [4]. Fermi broadening/finite electronic temperature can be automated to decrease during optimization [6]. Improved initial guesses (guess=read) from simpler calculations provide stability without bias.

Workflow: SCF Stability Management in Geometry Optimization

The following diagram illustrates the systematic approach to diagnosing and resolving SCF-related geometry optimization failures:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Computational Reagents

Table: Key Computational Parameters for Stable SCF-Driven Geometry Optimizations

| Computational 'Reagent' | Function/Purpose | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Level Shifters | Increases HOMO-LUMO gap during SCF to prevent oscillation | SCF=vshift=400 (Gaussian) [4]Electronic temperature automation [6] |

| Alternative Mixers | Replaces default DIIS for problematic systems | SCF%Method MultiSecant [6]SCF=QC (Quadratic Convergence) [4] |

| Numerical Stabilizers | Improves integration accuracy for gradients and energy | NumericalQuality Good [7]int=ultrafine [4] |

| Basis Set Sanitizers | Prevents linear dependence and core overlap issues | Confinement for diffuse functions [6]Smaller frozen cores [7] |

| Coordinate Transformers | Alternative coordinate systems for stable optimization | coordsys redundant (default) [23]coordsys cartesian (fallback) [23] |

| Hessian Initializers | Provides better initial optimization direction | InHess Almloef [23]InHess Read (from semiempirical) [23] |

| Solvation Handlers | Manages solvent model introduction | Gas-phase initial guess → guess=read with solvation [4]Automated convergence criteria [6] |

| 2-Ethoxyoctan-1-amine | 2-Ethoxyoctan-1-amine|High-Purity Research Chemical | |

| Cyclobutene, 1-methyl- | Cyclobutene, 1-methyl-, CAS:1489-60-7, MF:C5H8, MW:68.12 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The interdependence between SCF stability and geometry optimization reliability presents both a challenge and opportunity for automated computational research. By implementing the diagnostic strategies and solution protocols outlined here, researchers can develop more robust computational workflows. Future directions in automated SCF convergence should focus on dynamic parameter adjustment, intelligent fallback strategies, and machine learning-based prediction of optimal method combinations for specific chemical systems.

Advanced Algorithms and Implementation for Automated SCF Workflows

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: How do I select the right SCF algorithm for my system?

The optimal SCF algorithm depends heavily on your molecular system and the specific convergence issues you encounter. The table below summarizes the primary characteristics and recommended use cases for each major algorithm.

Table 1: SCF Algorithm Selection Guide

| Algorithm | Full Name | Key Principle | Best For | Fallback When |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIIS [11] [25] | Direct Inversion in the Iterative Subspace | Extrapolates new Fock matrices by minimizing the error vector norm ([\mathbf{F}, \mathbf{PS}]) [11]. | Default calculations, closed-shell systems [11] [26]. | It fails to converge in initial cycles; then try RCA_DIIS or DIIS_GDM [11]. |

| GDM [11] | Geometric Direct Minimization | Takes steps in orbital rotation space that account for its spherical geometry [11]. | Restricted open-shell (ROHF) calculations; fallback when DIIS fails [11]. | DIIS is oscillating or converging to a high-energy state [11]. |

| SOSCF [25] [26] | Second-Order SCF | Uses an approximate orbital Hessian to achieve superlinear or quadratic convergence [26]. | Systems with small HOMO-LUMO gaps, difficult open-shell transition metal complexes [25] [26]. | DIIS or GDM are slow or fail to converge tightly. |

| ADIIS [11] [27] | Accelerated DIIS | An accelerated variant of DIIS; functionally similar to EDIIS for Hartree-Fock [27]. | Similar use cases as DIIS; performance can be system-dependent [11] [27]. | Standard DIIS is not efficient enough. |

The following workflow provides a logical decision path for selecting and troubleshooting SCF algorithms:

FAQ: My calculation involves a transition metal complex. Why does the SCF keep oscillating or diverging?

This is a common problem. Open-shell systems like transition metal complexes have challenging electronic structures with near-degenerate orbitals, which can cause oscillations between different orbital occupancies [26] [22].

Recommended Protocol:

- Initial Guess: Use a better initial guess than the core Hamiltonian. Superposition of Atomic Densities (SAD) or reading orbitals from a previous calculation (

init_guess = chkfilein PySCF) can provide a more stable starting point [25]. - Algorithm: Start with GDM (the default for ROHF in Q-Chem) or SOSCF [11] [26]. These methods are more robust for such difficult cases. In ORCA, the

TRAH(trust-region augmented Hessian) algorithm is a powerful second-order method [22]. - Advanced Techniques: If oscillations persist, employ the Maximum Overlap Method (MOM). MOM ensures that the calculation occupies a continuous set of orbitals by tracking the overlap with the previous iteration's orbitals, preventing "root flipping" [11].

- Convergence Criteria: For transition metals, using tighter convergence criteria (e.g.,

!TightSCFin ORCA) is often necessary for accurate geometry optimization and vibrational analysis [11] [22].

FAQ: The SCF energy is changing very slowly in the final cycles and won't meet the convergence threshold. What can I do?

This "trailing convergence" is a common impediment to high-throughput workflows [5].

Recommended Protocol:

- Algorithm Switching: Use a hybrid approach. In Q-Chem, specify

SCF_ALGORITHM = DIIS_GDM. This uses the fast DIIS extrapolation initially and switches to the robust Geometric Direct Minimization in later iterations to finalize convergence [11]. - Second-Order Methods: Decorate your SCF object with a second-order solver. In PySCF, this is done with

mf = scf.RHF(mol).newton(), which uses the co-iterative augmented hessian (CIAH) method to achieve quadratic convergence near the solution [25]. - Level Shifting: Apply a level shift to increase the energy gap between occupied and virtual orbitals. This stabilizes the SCF procedure. In PySCF, this is controlled by setting the

level_shiftattribute [25].

FAQ: What are the standard convergence criteria, and when should I tighten them?

SCF convergence is judged based on multiple criteria. The following table outlines standard and tight values, commonly used in programs like ORCA [22].

Table 2: SCF Convergence Criteria Comparison

| Criterion | Description | Standard / 'Medium' Value | Tight / 'TightSCF' Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| TolE | Change in total energy between cycles | 1e-6 a.u. [22] | 1e-8 a.u. [22] |

| TolRMSP | Root-mean-square change in density matrix | 1e-6 [22] | 5e-9 [22] |

| TolMaxP | Maximum change in density matrix | 1e-5 [22] | 1e-7 [22] |

| TolErr | DIIS error (maximum element of error vector) | 1e-5 a.u. [22] | 5e-7 a.u. [22] |

| TolG | Orbital gradient norm | 5e-5 [22] | 1e-5 [22] |

When to use Tight Criteria:

- Geometry Optimizations and Frequency Calculations: These require tighter thresholds (e.g.,

SCF_CONVERGENCE = 7in Q-Chem) to ensure accurate forces and vibrational frequencies [11]. - Transition Metal Complexes: Their complex electronic structure often requires

!TightSCF[22]. - Single-Point Energies for High Accuracy: For final energy evaluations, tighter criteria provide more significant figures [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit

This table details key computational "reagents" and their functions in SCF calculations.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for SCF Calculations

| Item / Software Feature | Function in Experiment | Example Commands / Usage |

|---|---|---|

| DIIS Subspace Size [11] | Controls the number of previous Fock matrices used for extrapolation. A larger subspace can speed up convergence but may become ill-conditioned. | DIIS_SUBSPACE_SIZE = 15 (Q-Chem default) [11] |

| Level Shifter [25] | Artificially increases the energy gap between occupied and virtual orbitals to stabilize the SCF procedure, useful for systems with small HOMO-LUMO gaps. | mf.level_shift = 0.5 (PySCF) [25] |

| Damping [25] [28] | Mixes a fraction of the Fock matrix from the previous iteration with the new one to prevent large oscillations in early cycles. | mf.damp = 0.5 mf.diis_start_cycle = 2 (PySCF) [25] |

| Maximum Overlap Method (MOM) [11] | Prevents oscillations in orbital occupancy by selecting orbitals with the greatest overlap with those from the previous iteration. | MOM is invoked via the STABLE keyword in ORCA or relevant $rem in Q-Chem [11]. |

| Quadratic Converger (QC) [28] | A robust, quadratically convergent algorithm that is slower per cycle but highly reliable for difficult cases. Not available for ROHF. | SCF=QC (Gaussian) [28] |

| Initial Guess: SAD / 'minao' [25] | Generates the initial density matrix via a superposition of atomic densities, often superior to the core Hamiltonian guess. | mf.init_guess = 'minao' (PySCF default) [25] |

| Initial Guess: Fragment / 'chk' [25] | Uses the wavefunction from a previous calculation (often a smaller basis set or similar molecule) as a starting point. | mf.init_guess = 'chkfile' mf.chkfile = '/path/to/file' (PySCF) [25] |

| 2,4-Dimethyl-1h-pyrrol-3-ol | 2,4-Dimethyl-1H-pyrrol-3-ol | Get 2,4-Dimethyl-1H-pyrrol-3-ol (CAS 1081853-61-3) for your research. This pyrrole building block is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 2,3-Dimethylbut-3-enal | 2,3-Dimethylbut-3-enal, CAS:80719-79-5, MF:C6H10O, MW:98.14 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

What is the fundamental principle behind hybrid DIIS-GDM algorithms?

The hybrid DIIS-Geometric Direct Minimization (GDM) algorithm is designed to combine the unique strengths of two powerful Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence methods. DIIS (Direct Inversion in the Iterative Subspace) excels at rapidly approaching the global SCF minimum during early iterations, efficiently recovering from initial guesses that may not be close to the final solution [29] [30]. However, DIIS can sometimes struggle to achieve final convergence, particularly when the local energy surface topology becomes challenging [30].

Geometric Direct Minimization (GDM) operates by taking steps in orbital rotation space that properly respect the hyperspherical geometry of the manifold of allowed SCF solutions [29] [31]. Unlike simpler methods that treat this space as flat, GDM accounts for its curved nature, much like how airplanes follow great circle routes rather than straight lines on a map [31]. This geometrical awareness makes GDM extremely robust for final convergence, even if it's slightly less efficient than DIIS for initial steps [29].

The hybrid approach strategically employs DIIS initially to benefit from its rapid approach to the solution basin, then automatically switches to GDM to robustly converge to the precise local minimum [29] [30]. This combination has proven particularly valuable for challenging systems including open-shell molecules and transition metal complexes [30].

Technical Implementation

What are the key control parameters for implementing DIIS-GDM in computational chemistry software?

Successful implementation of the DIIS-GDM hybrid algorithm requires careful configuration of several control parameters. The most critical parameters are summarized in the table below:

Table 1: Key Control Parameters for DIIS-GDM Implementation

| Parameter | Default Value | Function | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

SCF_ALGORITHM |

DIIS (varies by package) | Selects the convergence algorithm | Set to DIIS_GDM or DIIS_DM for hybrid approach [29] [30] |

MAX_DIIS_CYCLES |

50 | Maximum DIIS iterations before switching to GDM [29] | Set to 1 for minimal DIIS; higher values (10-30) for difficult cases [29] |

THRESH_DIIS_SWITCH |

2 | Error threshold (10â»â¿) for switching from DIIS to GDM [29] | Values of 2-4 provide balanced performance [29] |

SCF_CONVERGENCE |

5 (single point), 7 (optimizations) | Convergence criterion (10â»â¿) [30] | Tighter values (7-8) for geometry optimizations [30] |

DIIS_SUBSPACE_SIZE |

15 | Number of previous Fock matrices in DIIS extrapolation [30] | Increase to 25-40 for difficult systems [10] |

The switching mechanism between the two algorithms can be triggered by either the DIIS error threshold (THRESH_DIIS_SWITCH) or the maximum number of DIIS cycles (MAX_DIIS_CYCLES), whichever condition is met first [29]. For systems where preserving the initial guess is crucial, setting MAX_DIIS_CYCLES=1 ensures only a single Roothaan step occurs before GDM takes over, providing proper orbital orthogonalization with minimal disturbance to the initial guess [29] [31].

Table 2: Complementary SCF Convergence Parameters

| Parameter | Function | Usage Notes |

|---|---|---|

MAX_SCF_CYCLES |

Maximum total SCF iterations permitted [30] | Increase to 200-500 for slowly converging systems [10] |

DIIS_ERR_RMS |

Switches from maximum to RMS error for DIIS [30] | Maximum error typically provides more reliable convergence [30] |

Shift / LevelShift |

Artificially raises virtual orbital energies [20] | Helps overcome convergence issues but affects properties involving virtual orbitals [20] |

Workflow and Process Visualization

What is the complete workflow for the hybrid DIIS-GDM convergence process?

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and decision points in the hybrid DIIS-GDM convergence strategy:

The workflow begins with initial guess generation, which is critical for the overall convergence process. The SAD (Superposition of Atomic Densities) guess is compatible with the DIIS_GDM approach, while pure GDM requires an initial guess set of orbitals [29] [31]. The algorithm then proceeds through the DIIS phase, which efficiently reduces the initial large errors and heads toward the solution basin.

The switching condition is continuously monitored during the DIIS phase. When either the DIIS error falls below the threshold defined by THRESH_DIIS_SWITCH (typically 10â»Â² to 10â»â´) or the number of DIIS cycles reaches MAX_DIIS_CYCLES, the algorithm transitions to the GDM phase [29]. This transition captures the optimal balance between DIIS's efficiency in the initial search and GDM's robustness for final convergence.

Research Reagent Solutions

What essential computational "reagents" are required for implementing hybrid convergence strategies?

Implementing effective hybrid convergence strategies requires both algorithmic components and system-specific adjustments. The table below details key "research reagents" - essential materials and parameters - for successful implementation:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Hybrid Convergence

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Algorithms | DIIS (Pulay), GDM, DM, QC [28] | Primary convergence engines | DIIS for initial convergence; GDM for final convergence [29] |

| Initial Guess Methods | SAD, Core Hamiltonian, Hückel, PModel [10] | Starting point for SCF iterations | SAD guess compatible with DIIS_GDM [29] |

| Convergence Accelerators | Damping, Level Shifting, Fermi Smearing [20] [28] | Stabilize early SCF iterations | Electron smearing helpful for small HOMO-LUMO gaps [20] |

| Fallback Strategies | RCA, MOM, TRAH [30] [22] | Alternative approaches when DIIS-GDM struggles | MOM maintains orbital continuity; RCA guarantees energy decrease [30] |

| System-Specific Templates | SlowConv, VerySlowConv (ORCA) [10] | Pre-configured parameter sets | Transition metal complexes, open-shell systems [10] |

These computational reagents must be selected and combined according to the specific chemical system under investigation. For instance, transition metal complexes with localized d-electrons often benefit from stronger damping parameters and delayed second-order convergence steps [10], while systems with very small HOMO-LUMO gaps may require electron smearing to achieve convergence [20].

Troubleshooting Guide

What specific troubleshooting strategies address common DIIS-GDM convergence failures?

Scenario 1: DIIS phase shows wild oscillations or uncontrolled error growth

Problem Identification: The DIIS error (as measured by the commutator ||FD - DF||) fluctuates wildly without establishing a consistent downward trend [20] [10].

Recommended Solutions:

- Implement damping: Reduce the mixing parameter to 0.015-0.09 range to stabilize early iterations [20]

- Increase DIIS subspace size: Expand

DIIS_SUBSPACE_SIZEfrom default 15 to 25-40 to improve extrapolation stability [30] [10] - Delay DIIS start: Set initial equilibration cycles (

Cycparameter) to 20-30 before DIIS activation [20] - Switch to RCA initializer: Use

RCA_DIISalgorithm for severely problematic cases [30]

Scenario 2: Successful DIIS phase but GDM fails to achieve final convergence

Problem Identification: DIIS reduces error to intermediate levels (10â»Â²-10â»Â³) but GDM cannot reach tight convergence (10â»â¶-10â»â¸).

Recommended Solutions:

- Adjust switch timing: Modify

THRESH_DIIS_SWITCHto ensure DIIS doesn't hand over to GDM too early or too late [29] - Increase maximum iterations: Set

MAX_SCF_CYCLESto 200-500 for slowly converging systems [10] - Verify integral accuracy: Ensure integral threshold (

THRESH) is 3-5 orders tighter thanSCF_CONVERGENCE[30] - Enable full Fock rebuilds: Set

directresetfreq = 1to eliminate numerical noise in difficult cases [10]

Scenario 3: Convergence to unphysical or incorrect electronic state

Problem Identification: The algorithm converges efficiently but to an electronic state with incorrect symmetry, occupation, or energy.

Recommended Solutions:

- Verify initial guess and symmetry: Use

Guess = PModelorHCorealternatives and disable symmetry if problematic [10] [32] - Employ Maximum Overlap Method (MOM): Enforce orbital continuity to prevent root flipping [30]

- Converge alternative oxidation state: First converge a closed-shell oxidized/reduced state, then read orbitals as guess [10]

- Perform stability analysis: Check if converged solution represents true minimum or saddle point [22]

Advanced Methodologies

What specialized methodologies exist for pathological cases in automated convergence protocols?

For truly pathological systems that resist standard DIIS-GDM approaches, several advanced methodologies have been developed:

Second-Order Convergence Methods: The Trust Radius Augmented Hessian (TRAH) approach provides robust second-order convergence but at increased computational cost [22]. This method is particularly valuable for systems with multiple nearly-degenerate states. Implementation typically involves automatic activation when standard methods struggle, with control parameters such as AutoTRAHTOl and AutoTRAHIter fine-tuning the activation criteria [22].

Aggressive Damping Protocols: For systems with severe convergence issues, such as metal clusters or complex open-shell species, specialized damping protocols can be implemented:

This configuration, combined with keywords like SlowConv or VerySlowConv in ORCA, provides the heavy damping necessary for pathological cases [10].

Multi-Layer Hybrid Approaches: The most challenging cases may benefit from three-stage convergence strategies:

- Initial stabilization: Heavy damping and delayed DIIS (20-30 cycles)

- Intermediate acceleration: Standard DIIS with expanded subspace (15-25 vectors)

- Final convergence: GDM or quadratically convergent (QC) methods [28]

This multi-stage approach systematically addresses different convergence challenges at appropriate stages of the SCF process.

Frequently Asked Questions

How does the performance of DIIS-GDM compare to other convergence algorithms for transition metal complexes?

For transition metal complexes, particularly open-shell systems, DIIS-GDM typically outperforms pure DIIS while remaining more efficient than pure second-order methods. DIIS alone often struggles with the challenging potential energy surfaces and near-degeneracies common in transition metal systems [10]. Pure GDM, while robust, may require more iterations to approach the solution basin from poor initial guesses [29]. The hybrid approach leverages DIIS to rapidly locate the correct region of the solution space, then employs GDM to reliably converge to the precise minimum, making it particularly well-suited for these chemically important but computationally challenging systems [30].

What are the compatibility constraints between DIIS-GDM and initial guess methods?

The DIIS_GDM hybrid algorithm is compatible with the SAD (Superposition of Atomic Densities) initial guess, while pure GDM requires an initial guess set of orbitals [29] [31]. This compatibility makes the hybrid approach particularly valuable for automated workflows, as it can begin from standard atomic initial guesses without requiring pre-converged orbitals. For difficult cases, initial guesses from lower-level calculations (e.g., BP86/def2-SVP) can be read via MORead functionality to provide improved starting points [10].

How can researchers determine optimal switching parameters between DIIS and GDM?

Optimal switching parameters are system-dependent but can be determined through systematic investigation:

- Begin with defaults:

THRESH_DIIS_SWITCH=2andMAX_DIIS_CYCLES=50[29] - Monitor DIIS error progression - switch should occur when error reduction plateaus

- For difficult metals: Use more aggressive DIIS (

MAX_DIIS_CYCLES=30-40) before switching - For stable organic systems: Early switch (

MAX_DIIS_CYCLES=10-20) may improve efficiency - Conservative approach: Set

THRESH_DIIS_SWITCH=3for more DIIS refinement before GDM

What diagnostic tools are available to analyze convergence problems in hybrid algorithms?

Modern computational chemistry packages provide several diagnostic tools:

- SCF iteration reports: Monitor energy changes, density changes, and DIIS error norms [30]

- Orbital gradient analysis: Identify specific orbital pairs causing convergence issues [22]

- Stability analysis: Determine if converged solution represents true minimum [22]

- Density matrix examination: Check for idempotency violations and symmetry breaking [30]

- Convergence threshold monitoring: ORCA's

ConvCheckModeprovides flexible convergence criteria assessment [22]

These diagnostics enable researchers to identify whether convergence failures occur in the DIIS or GDM phase and apply appropriate corrective strategies.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the most common causes of SCF convergence failure?

SCF convergence failures typically stem from a few common issues:

- Problematic Molecular Systems: Open-shell systems, transition metal complexes, and diradicals have near-degenerate orbitals that cause charge sloshing [10].

- Inadequate Initial Guess: A poor starting point for the molecular orbitals can lead the SCF procedure down a path to divergence [25].

- Basis Sets with Diffuse Functions: Basis sets like aug-cc-pVDZ can introduce linear dependence in the atomic orbital basis, especially for larger molecules [33].

- Small HOMO-LUMO Gap: Systems with a small energy gap between the highest occupied and lowest unoccupied molecular orbitals are inherently difficult to converge [4] [34].

My calculation converged in one software but not another. Why?

Different quantum chemistry packages often have default settings for SCF convergence algorithms, integration grids, and handling of numerical issues. For instance:

- Linear Dependency Thresholds: The default threshold for removing linearly dependent basis functions varies. Q-Chem and Gaussian use 1e-6, while ORCA uses a tighter 1e-7, which can lead to different behavior with diffuse basis sets [33].

- Default SCF Algorithms: PySCF and ORCA default to DIIS, but ORCA can automatically switch to a more robust Trust Radius Augmented Hessian (TRAH) algorithm if DIIS struggles [10]. Gaussian offers the

SCF=QC(quadratic convergence) algorithm as an alternative [4]. - Initial Guesses: The default strategies for generating an initial guess (e.g.,

'minao'in PySCF,PModelin ORCA, or core Hamiltonian in Gaussian) can lead the SCF to different solutions or convergence behavior [25] [10].

When should I relax the SCF convergence criteria, and what are the risks?

Relaxing the convergence criteria (e.g., using SCF=conver=6 in Gaussian) can be useful for preliminary geometry optimization steps or single-point energy calculations where high precision in the density matrix is not critical [4].

However, you should avoid relaxed criteria for:

- Final energy calculations where high precision is required.

- Frequency calculations, as the numerical differentiation of gradients is highly sensitive to incomplete SCF convergence and can produce meaningless results [4].

- Property calculations that depend on the virtual orbitals (e.g., excitation energies) if level-shifting techniques are used, as level shifting artificially changes orbital energies [34].

How can I transfer orbitals between calculations to improve convergence?