Automated High-Throughput Synthesis of Inorganic Powders: Accelerating Discovery for Biomedicine and Beyond

This article explores the transformative impact of automated high-throughput synthesis on the development of inorganic powders and nanomaterials.

Automated High-Throughput Synthesis of Inorganic Powders: Accelerating Discovery for Biomedicine and Beyond

Abstract

This article explores the transformative impact of automated high-throughput synthesis on the development of inorganic powders and nanomaterials. It examines the foundational principles of autonomy in materials discovery, detailing the integration of robotics, artificial intelligence, and computational guidance. The scope covers advanced methodological approaches and their specific applications in creating functional materials for drug delivery, theranostics, and biomedicine. The content also addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies to overcome synthesis barriers, and provides a framework for validating and comparing outcomes against traditional methods. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes recent breakthroughs and future directions for this rapidly evolving field.

The Rise of Autonomous Labs: Foundations of Automated Inorganic Synthesis

Bridging the Gap Between Computational Prediction and Experimental Realization

The discovery and development of new inorganic materials are fundamental to technological advances in fields such as energy storage, catalysis, and electronics. Traditionally, this process has been guided by human intuition and trial-and-error, often requiring decades to move from concept to application. While computational methods, particularly density functional theory (DFT), have dramatically accelerated the identification of promising hypothetical materials from vast chemical spaces, a significant bottleneck remains: the experimental realization of these predicted structures. This gap between computational prediction and experimental synthesis hinders the pace of innovation. The emergence of automated high-throughput synthesis platforms represents a paradigm shift, offering a robust bridge across this divide. By integrating robotics, artificial intelligence (AI), and large-scale computational data, these autonomous laboratories are systematically accelerating the discovery and synthesis of novel inorganic powders, transforming the traditional materials research workflow into a closed-loop, data-rich endeavor.

The Core Challenge: From Virtual to Real

The challenge of synthesizing computationally predicted materials is multifaceted. First, the stability predicted by ab initio calculations at 0 K does not guarantee successful synthesis at experimental conditions, where kinetics, precursor selection, and reaction pathways play critical roles [1]. A human researcher's decision to, for example, "substitute a metal or cation to an existing material" is often a slow, iterative process limited to local explorations of chemical space [1]. Second, traditional solid-state synthesis is inherently labor-intensive, involving repetitive cycles of grinding, calcination, and characterization, which are difficult to scale [2].

The scale of the problem is evident in the numbers. Large-scale computational screenings, such as those by the Materials Project and Google DeepMind's GNoME model, have identified hundreds of thousands to millions of potentially stable compounds [3] [4]. In contrast, the number of known synthesized compounds is orders of magnitude smaller. For instance, in the exotic A₂BB'O₆ perovskite family, data-mining revealed only 68 known compounds out of a predicted 13,000-plus possibilities [5]. This vast unexplored territory necessitates a new, accelerated approach to experimental synthesis.

Technological Pillars of Integration

Closing the loop between prediction and synthesis rests on three interconnected technological pillars: sophisticated computational prediction, automated robotic platforms, and intelligent decision-making algorithms.

Advanced Computational Prediction and Generative Models

The starting point for accelerated discovery is the reliable computational identification of novel, stable materials. Beyond high-throughput screening of enumerated structures, generative AI models have recently emerged as a powerful tool for inverse design. These models directly generate candidate structures that satisfy specific property constraints.

A leading example is MatterGen, a diffusion-based generative model for inorganic materials. MatterGen creates crystal structures by refining atom types, coordinates, and the periodic lattice [6]. Its performance marks a significant step forward; compared to previous models, it more than doubles the percentage of generated materials that are stable, unique, and new (SUN), and the generated structures are more than ten times closer to their DFT-relaxed local energy minimum [6]. After fine-tuning, MatterGen can generate stable, new materials with desired chemistry, symmetry, and properties like magnetism, enabling true inverse design for a wide range of applications.

Automated High-Throughput Synthesis Platforms

A cornerstone of this paradigm is the development of robotic platforms capable of executing solid-state synthesis with minimal human intervention. These systems address the unique challenges of handling and characterizing solid powders, which can vary widely in density, flow behavior, and particle size [3].

- The A-Lab: Developed by DeepMind, this autonomous laboratory synthesizes inorganic powders from computed target materials. Its integrated system includes a preparation station that dispenses and mixes precursor powders, a robotic arm that loads crucibles into one of four box furnaces, and a characterization station where samples are ground and measured by X-ray diffraction (XRD) [3]. In a landmark demonstration, the A-Lab successfully synthesized 41 of 58 novel target compounds over 17 days of continuous operation.

- Slurry-Based Workflow: Researchers at the University of Liverpool developed a high-throughput sub-solidus synthesis workflow that adapts traditional ceramic processing for automation [2]. Precursor powders are wet-milled into aqueous slurries, which are then robotically dispensed and mixed using a liquid-handling station. The mixtures are dried into pellets for calcination. This method allows for the preparation of dozens of gram-scale samples per week, handling compositions beyond oxides, such as polyanion-based systems [2].

- Affordable Automated Modules: To make high-throughput strategies more accessible, systems like MAITENA (Materials Acceleration and Innovation plaTform for ENergy Applications) have been developed. These semi-automated stations integrate liquid-handling modules capable of performing sol-gel, Pechini, solid-state, and hydro/solvothermal syntheses, preparing several dozen gram-scale samples weekly with high reproducibility [7].

Intelligent Decision-Making and Active Learning

Automation alone is insufficient; autonomy requires an "AI brain" to plan experiments and interpret outcomes. These platforms use a combination of historical knowledge and active learning to guide synthesis.

- Literature-Driven Initial Recipes: The A-Lab, for example, uses natural-language models trained on vast scientific literature to propose initial synthesis recipes based on analogy to known related materials [3]. A second model suggests an appropriate synthesis temperature [3].

- Active Learning for Optimization: When initial recipes fail, active learning closes the loop. The A-Lab uses an algorithm called ARROWS³, which integrates ab initio computed reaction energies with observed experimental outcomes to predict improved solid-state reaction pathways [3]. This algorithm is grounded in two key hypotheses: 1) solid-state reactions tend to occur pairwise, and 2) intermediate phases with a small driving force to form the target should be avoided [3]. This approach successfully identified improved synthesis routes for nine targets in its initial run, six of which had zero yield from the initial recipes.

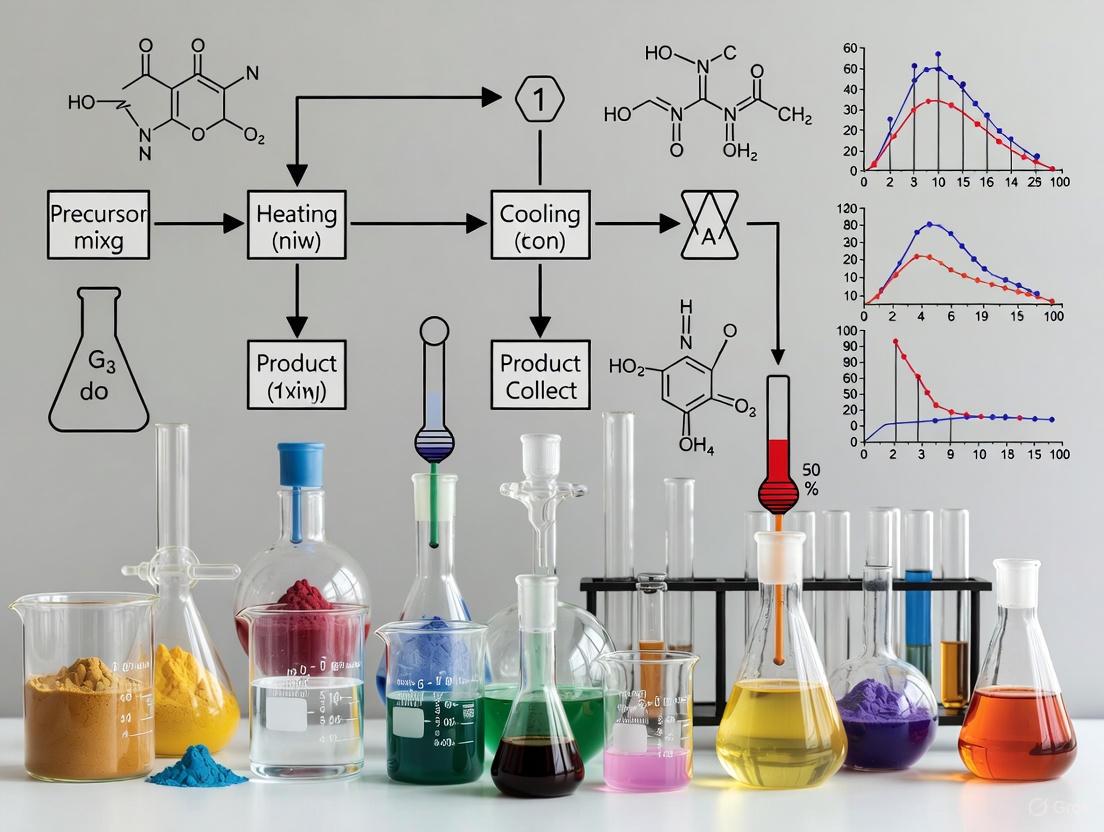

The following diagram illustrates the integrated closed-loop workflow of an autonomous laboratory.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Autonomous Workflow for Novel Powder Synthesis (A-Lab)

This protocol outlines the general procedure for the autonomous synthesis of novel inorganic powders, as demonstrated by the A-Lab [3].

- Objective: To synthesize a novel, computationally predicted inorganic material as the majority phase in a powder sample.

- Target Identification: Select targets predicted to be on or near (<10 meV per atom) the convex hull of stable phases from databases like the Materials Project. Filter for air stability.

- Precursor Selection and Recipe Generation:

- Initial Recipe: Input the target composition into a natural-language processing model trained on historical synthesis literature. The model proposes up to five precursor sets based on chemical similarity to known materials.

- Temperature Prediction: A second machine learning model, trained on literature heating data, proposes a synthesis temperature for each recipe.

- Robotic Synthesis Execution:

- Dispensing: A robotic arm dispenses and mixes the dry precursor powders in an alumina crucible.

- Heating: The crucible is automatically transferred to a box furnace and heated under static air conditions according to the proposed temperature profile.

- Cooling: The sample is allowed to cool to ambient temperature within the furnace.

- Automated Characterization and Analysis:

- Sample Preparation: A robot transfers the cooled sample to a grinding station, where it is pulverized into a fine powder.

- XRD Measurement: The powder is characterized by X-ray diffraction.

- Phase Analysis: The XRD pattern is analyzed by a machine learning model to identify phases and determine weight fractions via automated Rietveld refinement. A target yield of >50% is considered successful.

- Active Learning and Iteration:

- If Yield <50%: The active learning algorithm (ARROWS³) analyzes the reaction pathway and products.

- It uses a growing database of observed pairwise reactions and computed driving forces to propose a new precursor set or modified conditions that avoid low-driving-force intermediates.

- The loop (Synthesis → Characterization → Analysis → New Proposal) continues until success is achieved or all recipe options are exhausted.

High-Throughput Slurry-Based Synthesis of Oxides

This protocol details a complementary workflow designed for rapid screening of oxide chemical space, producing discrete pellets suitable for characterization [2].

- Objective: To explore ternary and higher-order oxide compositions and identify new multi-component phases in a high-throughput manner.

- Wet Milling of Precursors:

- Combine insoluble raw materials (oxides, carbonates, oxalates) with deionised water, zirconia milling media, an ammonium polyacrylate dispersant, and an acrylic emulsion binder in a planetary mill.

- Mill to create a homogeneous aqueous suspension with a known inorganic precursor content per unit volume.

- Verify solids content by drying and weighing a sample aliquot. Keep the suspension on a sample rotator to prevent sedimentation.

- Automated Slurry Dispensing and Mixing:

- Use an automated liquid handler (e.g., Eppendorf epMotion 5075) with a custom low-profile magnetic stirrer to keep suspensions homogeneous during aspiration.

- Aspirate calculated volumes from different precursor suspensions to achieve the target composition and dispense them into a single glass vial.

- Mix the formulation within the vial by repeated robotic aspiration and dispensing.

- Dispensing into Arrays and Drying:

- Dispense 0.2 mL aliquots of each mixture into custom vacuum-formed PET trays containing multiple wells.

- Dry the arrays of samples to form solid pellets within the wells.

- Pellet Compaction and Calcination:

- Isopress the entire tray of dried pellets to increase their density.

- Transfer the trays to a furnace for calcination at the desired temperature and atmosphere. Multiple trays can be processed simultaneously to screen different temperatures or atmospheres.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Hardware

The following table details key reagents, materials, and hardware essential for establishing automated high-throughput synthesis workflows for inorganic powders.

Table 1: Key Research Reagents and Hardware for Automated Synthesis

| Category | Item / Component | Function / Description |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Materials | Metal Oxides, Carbonates, Oxalates | High-purity, insoluble solid powders serving as the primary cation sources for solid-state reactions [2]. |

| Dispersant & Binder | Ammonium Polyacrylate, Acrylic Emulsion | Dispersant reduces suspension viscosity for handling; binder increases mechanical strength of pellets for processing [2]. |

| Automation Hardware | Robotic Liquid Handler (e.g., epMotion) | Precisely aspirates, dispenses, and mixes viscous precursor slurries [2]. |

| Robotic Arm(s) | Transfers samples and labware between stations for dispensing, heating, and characterization [3]. | |

| Automated Furnaces | Provides programmable, high-temperature heating for solid-state reactions. The A-Lab uses four box furnaces [3]. | |

| Characterization | X-Ray Diffractometer (XRD) | The primary tool for phase identification and quantification of synthesis products via Rietveld refinement [3]. |

| Software & AI | Active Learning Algorithm (e.g., ARROWS³) | Proposes improved synthesis recipes by integrating computed reaction energies and experimental outcomes [3]. |

| Generative Model (e.g., MatterGen) | Inverse-designs novel, stable crystal structures conditioned on desired properties [6]. | |

| Phoslactomycin E | Phoslactomycin E, MF:C32H50NO10P, MW:639.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| SAL-0010042 | SAL-0010042, MF:C15H15FN4O, MW:286.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Quantifying Success and Analyzing Failure

The performance of integrated computational-predictive and autonomous-experimental systems is demonstrating remarkable effectiveness. The table below summarizes quantitative outcomes from recent landmark studies.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Autonomous Discovery Platforms

| Platform / Model | Key Metric | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| A-Lab (Experimental) | Novel Targets Synthesized | 41 out of 58 (71%) | [3] |

| Success with Literature Recipes | 35 out of 41 materials | [3] | |

| Optimization via Active Learning | 9 targets (6 with initial 0% yield) | [3] | |

| MatterGen (Generative AI) | Stable, Unique, New (SUN) Materials | >2x increase vs. prior models | [6] |

| Distance to DFT Minimum (RMSD) | >10x closer vs. prior models | [6] | |

| High-Throughput Slurry Workflow | Accessible Composition Space | Quaternary oxide systems (A-B-C-O) | [2] |

Despite these successes, analysis of failures is equally informative. For the 17 targets the A-Lab did not synthesize, failure modes were categorized [3]:

- Slow Reaction Kinetics: The most common issue (affecting 11 targets), often involving reaction steps with low thermodynamic driving forces (<50 meV per atom).

- Precursor Volatility: Loss of precursor components at high temperatures, altering the reactant stoichiometry.

- Amorphization: Formation of non-crystalline products, preventing identification by XRD.

- Computational Inaccuracy: Instances where the predicted stable structure may not be the true ground state under synthesis conditions.

The field is rapidly evolving from systems that automate single tasks toward fully integrated, "self-driving" laboratories powered by large-scale intelligent models [4]. The next frontier involves moving beyond isolated platforms to create networked, cloud-based autonomous laboratories. This would enable seamless data and resource sharing across institutions, creating a collective intelligence for materials discovery [4]. Furthermore, the development of more sophisticated generative models and accurate machine-learning force fields will continue to enhance the quality of predictions and the efficiency of the experimental search.

In conclusion, the gap between computational prediction and experimental realization is being bridged by a powerful new research paradigm. The integration of high-throughput computation, AI-driven decision-making, and automated robotic synthesis forms a closed-loop system that dramatically accelerates the discovery of novel inorganic materials. This embodied intelligence approach not only validates computational predictions at an unprecedented rate but also generates the high-quality, standardized data essential for refining the underlying models. As these technologies become more accessible and widespread, they hold the promise of ushering in a new era of accelerated innovation across energy, electronics, and beyond.

The field of materials science is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by the integration of robotics, artificial intelligence (AI), and historical data. This fusion creates autonomous laboratories, or "self-driving labs," which are poised to accelerate the discovery and synthesis of novel materials, particularly inorganic powders. Traditional research paradigms, which rely heavily on manual, trial-and-error approaches, struggle to navigate the vastness of chemical space and often fail to uncover the underlying mechanisms of material formation [4]. Autonomous laboratories address this bottleneck by closing the "predict-make-measure" discovery loop, enabling the rapid and systematic exploration of complex material systems [3] [4]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to the core components that constitute these intelligent systems, framed within the context of automated high-throughput synthesis for inorganic powders.

The Pillars of Autonomous Discovery

An autonomous laboratory is an advanced robotic platform equipped with embodied intelligence, allowing it to execute experiments, interact with robotic systems, and manage data with minimal human intervention [4]. The seamless operation of such a system rests on four fundamental pillars that work in synergy.

Core Component 1: Chemical Science Databases and Historical Data

Historical and experimental data serve as the foundational knowledge base for any autonomous discovery platform.

- Function: The chemical science database is the collective memory of the system, storing and organizing diverse, multimodal chemical data [4]. It provides the essential information for AI models to design experiments, predict outcomes, and suggest synthesis routes.

- Data Acquisition and Structuring: Data resources include both structured entries from proprietary and open-access databases and unstructured data extracted from scientific literature and patents using Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques [4]. These data can be further organized into Knowledge Graphs (KGs), which provide a structured, semantic representation of relationships between entities (e.g., precursors, synthesis conditions, and resulting phases), making the knowledge computationally accessible for AI planning and reasoning [4].

Core Component 2: Large-Scale Intelligent Models and AI

AI models act as the cognitive engine of the autonomous laboratory, transforming historical data into actionable hypotheses and decisions.

- Function: These models are responsible for data processing, outcome prediction, and iterative experimental planning. They enable the system to learn from past outcomes and refine its search strategy for optimal materials.

- Key Algorithms and Models:

- Literature-Inspired Recipe Generation: Initial synthesis recipes are often proposed by machine learning models trained through natural-language processing on vast databases of historical syntheses, mimicking a human researcher's approach of using analogy to known materials [3].

- Active Learning and Optimization: When initial recipes fail, active learning algorithms take over. For instance, the A-Lab used an algorithm called ARROWS³, which integrates ab initio computed reaction energies with observed synthesis outcomes to predict improved solid-state reaction pathways [3]. Other powerful optimization algorithms include:

- Bayesian Optimization: Efficiently minimizes the number of experiments needed to converge on an optimal result by balancing exploration and exploitation [8] [4].

- Genetic Algorithms (GAs): Explore a large parameter space by iteratively selecting, combining, and mutating the best-performing experimental candidates from a "population" [4].

Core Component 3: Automated Robotic Platforms

The robotic platform is the physical embodiment of the system, responsible for the precise execution of experiments in the real world.

- Function: This component automates the entire "make" and "measure" cycle, handling solid powder precursors, conducting reactions under controlled conditions, and characterizing the products.

- System Architecture: A representative platform for inorganic powders, as demonstrated by the A-Lab, integrates several robotic stations [3]:

- Sample Preparation Station: Automatically dispenses and mixes precursor powders.

- Heating Station: Uses robotic arms to load crucibles into box furnaces for solid-state reactions.

- Characterization Station: Transfers, grinds, and analyzes synthesized powders using techniques like X-ray diffraction (XRD).

- Handling Solid Powders: A key technical challenge is the robotic handling of solid powders, which can have widely varying properties like density, flow behavior, and particle size [3]. The platform must be engineered to manage milling and mixing to ensure good reactivity between precursors.

Core Component 4: Management and Decision-Making Systems

The management system is the central nervous system that orchestrates the entire autonomous operation.

- Function: This integrated software platform controls the robotic hardware, manages the flow of data between all components, and executes the AI-driven decision-making logic to close the experimental loop.

- Operational Workflow: The system operates through a continuous "Design-Build-Test-Learn" (DBTL) cycle. After the AI proposes an experiment, the management system schedules and executes it on the robotic platform, collects the characterization data, analyzes the results (e.g., determining phase purity and yield via XRD analysis and Rietveld refinement), and then uses this new data to update the AI models and propose the next experiment [3] [8].

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of these four core components within an autonomous laboratory.

Quantitative Performance and Data

The effectiveness of this integrated approach is demonstrated by tangible results from recent implementations. The table below summarizes key performance data from two autonomous systems.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Autonomous Discovery Platforms

| System / Platform | Primary Focus | Key Performance Metric | Reported Outcome | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-Lab | Synthesis of inorganic powders | Success rate for synthesizing novel compounds | 41 of 58 target compounds successfully synthesized (71% success rate) in 17 days | [3] |

| Autonomous Enzyme Engineering Platform | Engineering enzyme activity | Improvement in specific activity | 90-fold improvement in substrate preference; 16-fold improvement in ethyltransferase activity achieved in 4 weeks | [8] |

| A-Lab | Synthesis optimization | Effectiveness of active learning | Active learning identified improved synthesis routes for 9 targets, 6 of which had zero yield from initial recipes | [3] |

Table 2: Analysis of Synthesis Failures in Autonomous Operation

| Failure Mode Category | Number of Targets Affected | Description of Challenge | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Slow Reaction Kinetics | 11 | Reaction steps with low driving forces (<50 meV per atom), hindering completion. | [3] |

| Precursor Volatility | 3 | Loss of precursor material during high-temperature reactions. | [3] |

| Amorphization | 2 | Formation of non-crystalline products instead of the desired crystalline phase. | [3] |

| Computational Inaccuracy | 1 | Inaccurate ab initio predictions of material stability. | [3] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This section outlines the standard operating procedures for an autonomous laboratory targeting the synthesis of novel inorganic powders, based on the workflow established by the A-Lab [3].

Protocol 1: AI-Driven Synthesis Planning

Purpose: To generate viable initial synthesis recipes for a target inorganic compound predicted to be stable by ab initio calculations.

Methodology:

- Target Input: The process begins with a target material, typically identified from large-scale computational screening (e.g., the Materials Project, Google DeepMind's GNoME) as being thermodynamically stable or near-stable [3] [4].

- Literature-Based Analogy:

- A natural language processing model, trained on a large corpus of extracted synthesis literature, assesses the "similarity" of the target to known compounds [3].

- Based on this similarity, the model proposes up to five initial synthesis recipes, including precursor sets, by drawing analogies to successful historical syntheses.

- Temperature Prediction: A second machine learning model, trained on heating data from the literature, proposes an initial synthesis temperature [3].

- Active Learning Backup: If literature-inspired recipes fail, an active learning algorithm (e.g., ARROWS³) is invoked. This algorithm uses a database of observed pairwise solid-state reactions and thermodynamic data from the Materials Project to propose alternative precursor sets and reaction pathways that avoid low-driving-force intermediates [3].

Protocol 2: Robotic Execution of Solid-State Synthesis

Purpose: To physically carry out the powder synthesis recipe with high precision and reproducibility.

Methodology:

- Precursor Dispensing and Mixing:

- Precursor powders are automatically dispensed by a robotic system in the calculated stoichiometric ratios.

- Powders are transferred into an alumina crucible and mixed thoroughly, often involving milling to ensure good reactivity between precursors with different physical properties [3].

- High-Temperature Reaction:

- A robotic arm loads the crucible into one of multiple box furnaces.

- The reaction is carried out at the AI-predicted temperature and for a specified duration in air (for air-stable targets) [3].

- The sample is allowed to cool after the reaction is complete.

- Product Recovery and Preparation:

- Another robotic arm transfers the cooled crucible to a characterization station.

- The synthesized powder is ground into a fine, homogeneous consistency to ensure representative analysis [3].

Protocol 3: Automated Product Characterization and Analysis

Purpose: To determine the phase composition and yield of the synthesis product, and to feed this information back to the AI planner.

Methodology:

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD):

- The ground powder is automatically placed in an X-ray diffractometer for phase analysis [3].

- A diffraction pattern is collected over a defined 2θ range.

- Machine Learning Phase Analysis:

- Probabilistic ML models, trained on experimental structures from databases like the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD), are used to identify the phases present in the product from the XRD pattern [3].

- For novel compounds with no experimental data, simulated XRD patterns derived from computationally optimized structures are used.

- Yield Quantification:

- The identified phases are confirmed, and their weight fractions are quantified using automated Rietveld refinement [3].

- A synthesis is deemed successful if the target phase is obtained as the majority phase (>50% yield).

- Data Feedback: The resulting phase identification and yield quantification are reported to the management server. If the target yield is not met, this data triggers the next iteration of the active learning cycle.

The Scientist's Toolkit

The following table details key reagents, materials, and instruments essential for the automated high-throughput synthesis of inorganic powders.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Automated Powder Synthesis

| Item Name | Function / Role in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Precursor Powders | High-purity metal oxides, carbonates, phosphates, etc., serving as the starting materials for solid-state reactions. |

| Alumina Crucibles | Chemically inert containers that hold powder samples during high-temperature reactions in furnaces. |

| Box Furnaces | Provide controlled high-temperature environments necessary for solid-state synthesis and calcination. |

| X-ray Diffractometer (XRD) | The primary characterization tool for identifying crystalline phases and quantifying yield in synthesized powders. |

| Robotic Arms and Grippers | Perform physical tasks including transferring crucibles, dispensing powders, and grinding samples. |

| High-Throughput Filtration Device | Enables parallel recovery and washing of solid reaction products from multi-well reactor blocks (e.g., 48-well format) [9]. |

| Hmgb1-IN-3 | Hmgb1-IN-3, MF:C31H46O4, MW:482.7 g/mol |

| 4-Hydroxybaumycinol A1 | 4-Hydroxybaumycinol A1, CAS:78919-31-0, MF:C33H43NO13, MW:661.7 g/mol |

The fusion of robotics, AI, and historical data represents a paradigm shift in materials research. By integrating computational screening, AI-powered planning, robotic execution, and closed-loop learning, autonomous laboratories like the A-Lab have demonstrated an unprecedented ability to rapidly discover and synthesize novel inorganic powders. This technical guide has detailed the core components and protocols that make this possible. While challenges such as sluggish kinetics and data integration remain, the continued evolution of intelligent models, robotic hardware, and collaborative platforms promises to further accelerate the design of next-generation materials, ultimately reducing the time from discovery to application from years to a matter of days.

Defining High-Throughput in Inorganic Powder Synthesis

In the realm of inorganic materials science, high-throughput synthesis represents a paradigm shift from traditional sequential experimentation to massively parallelized, automated, and computationally-guided experimentation. This approach is characterized by the integration of robotics, artificial intelligence, and sophisticated data infrastructure to dramatically accelerate the discovery and optimization of novel inorganic powders. For inorganic powder synthesis—a field critical for developing next-generation battery materials, catalysts, and electronic components—high-throughput methodologies enable researchers to navigate complex multivariate synthesis parameter spaces efficiently. The defining core of high-throughput in this context extends beyond mere automation; it encompasses an integrated workflow where computational prediction, robotic execution, and intelligent analysis form a closed-loop discovery system [3] [10]. This technical guide examines the operational principles, quantitative benchmarks, and experimental protocols that define high-throughput inorganic powder synthesis, framed within the broader thesis of advancing autonomous materials research.

Core Principles and Quantitative Benchmarks

High-throughput inorganic powder synthesis is quantitatively distinguished from traditional methods by specific metrics pertaining to throughput, success rates, and operational efficiency. These benchmarks establish a formal definition for "high-throughput" in both capability and outcome terms.

Table 1: Quantitative Benchmarks of High-Throughput Synthesis Platforms

| Metric | Traditional Synthesis | High-Throughput Platform | Exemplary Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Duration | Months to years for a campaign | Continuous 24/7 operation | 17 days of continuous operation [3] |

| Number of Targets | Single or few compounds per study | Dozens of novel compounds | 41 novel compounds from 58 targets [3] |

| Success Rate | Highly variable, often low | Quantified and optimized | 71% success rate for novel materials [3] |

| Elements & Prototypes | Limited chemical space | Broad compositional range | 33 elements and 41 structural prototypes [3] |

| Throughput Scale | Manual gram-scale reactions | Robotic, parallel synthesis | 224 reactions in weeks targeting 35 materials [11] |

The operational philosophy of high-throughput synthesis is fundamentally anchored in autonomy—defined as the system's capability to interpret experimental data and make subsequent decisions without human intervention. As demonstrated by the A-Lab, an autonomous laboratory for solid-state synthesis, this involves using computations, historical data, machine learning, and active learning to both plan and interpret experiments performed using robotics [3]. This autonomy directly addresses the critical bottleneck in materials discovery: the vast gap between computational prediction rates and experimental realization.

Furthermore, the scope of "high-throughput" extends beyond speed to encompass experimental quality and reproducibility. For instance, a new precursor selection approach based on pairwise reaction analysis achieved higher phase purity for 32 out of 35 target materials synthesized in a robotic laboratory [11]. This demonstrates that high-throughput systems are not merely executing more experiments, but generating superior outcomes through principled experimental design.

Experimental Workflows and Methodologies

Integrated Autonomous Synthesis Pipeline

The end-to-end workflow for high-throughput inorganic powder synthesis integrates computational prediction, robotic execution, and characterization with a decision-making loop. The following diagram illustrates this integrated pipeline, as implemented in state-of-the-art autonomous laboratories.

Integrated Autonomous Synthesis Workflow

This workflow begins with computational target identification using ab initio phase-stability data from sources like the Materials Project and Google DeepMind [3]. Targets are screened for air stability to ensure compatibility with synthesis conditions. The system then generates initial synthesis recipes through natural language processing models trained on historical literature data, effectively encoding human chemical intuition [3].

The robotic execution phase involves three integrated stations: (1) sample preparation for precise powder dispensing and mixing, (2) automated heating in box furnaces with robotic loading/unloading, and (3) XRD characterization where samples are automatically ground into fine powder and measured [3]. Critical to the workflow is the intelligent analysis phase, where probabilistic machine learning models extract phase and weight fractions from XRD patterns, with automated Rietveld refinement providing validation [3].

When initial recipes fail to produce >50% target yield, an active learning loop engages through the ARROWS3 algorithm, which integrates ab initio computed reaction energies with observed synthesis outcomes to predict improved solid-state reaction pathways [3]. This closed-loop autonomy enables the system to learn from failures and continuously improve its synthetic strategies.

Pairwise Precursor Selection Methodology

A recent methodological advancement in high-throughput synthesis is the pairwise precursor selection approach, which has demonstrated significantly improved phase purity outcomes. The logical framework for this methodology is detailed below.

Pairwise Precursor Selection Logic

This methodology is grounded in the discovery that reactions between pairs of precursors dominate the synthesis process in multi-element inorganic powders [11]. By carefully studying phase diagrams that map all potential precursor reactions and strategically selecting precursors to avoid unwanted pairwise reactions that form stable impurity phases, researchers have developed a new set of criteria for precursor selection.

The experimental validation of this approach exemplifies high-throughput capabilities: researchers tested 224 reactions spanning 27 elements with 28 unique precursors targeting 35 oxide materials [11]. The robotic synthesis platform enabled this extensive validation to be completed in weeks rather than the months or years typically required. The results demonstrated that for 32 of the 35 materials, precursors selected with the new pairwise criteria produced higher yields of the targeted phase than traditional precursor selection methods [11].

Data Management Infrastructure

Underpinning these experimental workflows is a robust research data infrastructure specifically designed for high-throughput experimental materials science. This infrastructure must capture, store, and process large volumes of heterogeneous data—including synthesis parameters, characterization results, and computational inputs—in standardized, machine-readable formats [12]. Systems like the High-Throughput Experimental Materials Database (HTEM-DB) provide essential data architecture that enables machine learning algorithms to ingest and learn from high-quality, large-volume experimental datasets [12].

Specialized software platforms such as phactor have been developed to facilitate the design and analysis of high-throughput experiment arrays, allowing researchers to rapidly design arrays of chemical reactions in 24, 96, 384, or 1,536 wellplates [13]. These tools interface with chemical inventories to virtually populate wells with experiments and produce instructions for manual execution or robotic liquid handling, demonstrating how digital infrastructure is integral to the high-throughput synthesis paradigm [13].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The implementation of high-throughput inorganic powder synthesis requires specialized materials and instrumentation that collectively form the "scientist's toolkit" for this advanced research paradigm.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for High-Throughput Synthesis

| Category | Specific Examples | Function in High-Throughput Context |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Powders | 28 unique precursors spanning 27 elements [11] | Raw materials with diverse physical properties (density, particle size, flow behavior) for robotic dispensing |

| Solid-State Reactors | Alumina crucibles, box furnaces [3] | Withstand repeated high-temperature processing with robotic loading/unloading |

| Characterization Standards | Reference materials for XRD calibration [3] | Ensure consistent automated phase identification across thousands of samples |

| Computational Databases | Materials Project, Google DeepMind stability data [3] | Provide ab initio phase-stability calculations for target identification and screening |

| ML Training Data | Historical synthesis data from literature [3] [10] | Train natural language processing models to propose initial synthesis recipes |

| Reaction Database | Observed pairwise reactions (88 unique reactions) [3] | Inform active learning algorithm by documenting known reaction pathways |

This toolkit extends beyond physical reagents to encompass digital resources and algorithms that are equally essential to the high-throughput workflow. The integration of computational databases with robotic experimentation creates a synergistic cycle where computational predictions guide experiments, and experimental results refine computational models.

A critical enabling technology is the application of machine learning models for data interpretation, such as probabilistic phase analysis of XRD patterns [3]. These models are trained on experimental structures from databases like the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) but must be adapted for novel materials by using simulated diffraction patterns from computed structures, corrected to reduce density functional theory errors [3].

High-throughput inorganic powder synthesis represents a transformative approach that integrates computational screening, robotic automation, and machine intelligence to accelerate materials discovery. The defining characteristics of this paradigm include: (1) operational autonomy with closed-loop decision-making; (2) data-rich experimentation with standardized data infrastructure; and (3) validated performance benchmarks demonstrating accelerated discovery timelines and improved success rates.

As these technologies mature, future developments will likely focus on increasing the level of autonomy through improved active learning algorithms, expanding the accessible chemical space through more sophisticated precursor selection strategies, and enhancing data infrastructure to enable greater cross-laboratory collaboration and data sharing. The successful demonstration of autonomous laboratories achieving 71% success rates in synthesizing novel compounds suggests that the integration of artificial intelligence with robotics will continue to redefine the possibilities for inorganic materials discovery and development.

The synthesis of novel inorganic materials is a critical bottleneck in the development of next-generation technologies, from battery cathodes to solid-state electrolytes. Traditional synthesis methods, which rely on sequential, one-variable-at-a-time (OVAT) experimentation, are poorly suited to navigating the vast, multi-dimensional parameter spaces of inorganic powder synthesis [14]. The emergence of automated high-throughput experimentation (HTE) represents a paradigm shift, transforming materials discovery from a slow, artisanal process into a rapid, data-rich science. This whitepaper details how automated HTE platforms confer key advantages in speed, reproducibility, and the exploration of complex chemical spaces, thereby accelerating the entire research-to-development pipeline for researchers and drug development professionals.

Unparalleled Speed and Throughput in Experimentation

A primary advantage of high-throughput experimentation is its dramatic acceleration of experimental timelines. By miniaturizing and parallelizing reactions, HTE allows for the simultaneous evaluation of hundreds to thousands of synthesis conditions, a process that would be prohibitively time-consuming using manual methods [14].

Quantitative Evidence of Accelerated Workflows

The following table summarizes the throughput capabilities demonstrated by recent automated synthesis platforms:

Table 1: Throughput Metrics of Automated Synthesis Platforms

| Platform / Study Focus | Throughput Capability | Experimental Scale | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Organic Chemistry HTE [14] | Evaluation of "numerous reactions at once" | Microtiter plates | Accelerated data generation for molecule access and optimization. |

| Ultra-HTE [14] | Testing of 1,536 reactions simultaneously | Microscale | Significantly broadened examination of reaction chemical space. |

| Functional Polypeptide Exploration [15] | Generation of 1,200 homopolypeptides or random heteropolypeptides (RHPs) within one day | Not specified | Rapid exploration of complex biomaterial chemical space. |

| Robotic Inorganic Materials Synthesis [16] | 224 reactions performed by a single experimentalist | 35 target quaternary oxides | High-throughput hypothesis validation over broad chemical space. |

Enabling Rapid Machine Learning Cycles

The speed of HTE is not merely for brute-force screening. It enables a powerful, iterative feedback loop with machine learning (ML) algorithms. HTE generates the large, consistent datasets required to train ML models, which can then predict promising regions of chemical space to explore next, guiding subsequent HTE campaigns [17]. This synergy between rapid experimentation and intelligent computation creates a self-improving cycle for discovery and optimization [15].

Enhanced Reproducibility and Data Quality

Reproducibility is a cornerstone of the scientific method, yet it remains a significant challenge in traditional materials synthesis. Automated HTE directly addresses this issue through standardization and precision engineering.

Standardization of Protocols and Execution

Automated platforms execute synthesis protocols with a level of precision unattainable through manual manipulation. This includes:

- Consistent Precursor Handling: Automated dispensing of solid and liquid precursors minimizes human error in weighing and mixing [16].

- Precise Environmental Control: Robotic laboratories ensure consistent control of critical parameters such as temperature, atmosphere, and mixing speed across all experiments, mitigating spatial biases that can occur in traditional furnaces or heating blocks [14].

- Uniform Workflow Application: The entire workflow—from powder precursor preparation and ball milling to oven firing and X-ray characterization—is automated, ensuring every sample is treated identically [16].

Comprehensive and FAIR Data Capture

HTE platforms are designed for comprehensive data capture, which is essential for reproducibility and ML.

- Rich, Structured Data: Modern platforms capture not only the final outcome but also all relevant metadata, including detailed precursor information, exact reaction conditions, and analytical results [17].

- Adherence to FAIR Principles: There is a growing emphasis on making HTE-generated data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable. Initiatives like the Open Reaction Database provide guidelines and repositories to ensure data is stored in a standardized, machine-readable format, overcoming the limitations of historically unstructured data in scientific publications [17] [18].

Navigating Complex Chemical and Compositional Spaces

The synthesis of multicomponent inorganic materials is often impeded by the formation of undesired by-product phases, which can kinetically trap reactions in an incomplete state. Automated HTE, guided by thermodynamic reasoning and ML, provides a systematic framework for navigating these complexities.

Thermodynamic Principles for Precursor Selection

Effective synthesis requires intelligent precursor selection to maximize driving force and avoid kinetic traps. The following principles have been validated through large-scale robotic experimentation [16]:

- Initiate with Two Precursors: Reactions should ideally begin between only two precursors to minimize simultaneous pairwise reactions that form low-energy intermediates.

- Utilize High-Energy Precursors: Starting materials should be relatively unstable to maximize the thermodynamic driving force for fast phase transformation kinetics.

- Target as Deepest Hull Point: The target material should be the lowest-energy phase in the local reaction landscape, ensuring a greater driving force for its nucleation compared to competing phases.

- Minimize Competing Phases: The compositional slice between the two precursors should intersect as few competing phases as possible.

- Maximize Inverse Hull Energy: The target should be substantially lower in energy than its neighbouring stable phases, providing a large driving force even if intermediates form.

Table 2: Thermodynamic Principles Applied to Precursor Selection for Example Materials

| Target Material | Traditional Precursors | Proposed Optimal Precursors | Guiding Principle | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiBaBO3 [16] | Li2CO3, B2O3, BaO | LiBO2, BaO | Utilize High-Energy Precursors; Initiate with Two Precursors | Higher phase purity; avoids low-energy ternary intermediates. |

| LiZnPO4 [16] | Li2O, Zn2P2O7 or Zn3(PO4)2, Li3PO4 | LiPO3, ZnO | Target as Deepest Hull Point; Maximize Inverse Hull Energy | Large driving force (-147 meV/atom) and high selectivity for the target. |

Workflow for HTE-Driven Materials Discovery

The process of discovering and optimizing inorganic materials using an automated HTE platform integrates computational design and physical experimentation, as illustrated in the following workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The implementation of a successful HTE workflow for inorganic powder synthesis relies on a suite of essential reagents and equipment.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Automated Inorganic Synthesis

| Item / Category | Function & Importance | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Compounds | High-purity, well-characterized starting materials are critical for reproducible reactions and interpreting characterization data. | Binary oxides (e.g., BaO, ZnO), carbonates (e.g., Li2CO3), custom-synthesized intermediates (e.g., LiBO2, LiPO3) [16]. |

| Microtiter Plates (MTPs) | The physical platform for parallel reaction execution. Material compatibility and well design are crucial to mitigate evaporation and spatial bias. | Plates with 96, 384, or 1536 wells; materials resistant to organic solvents and high temperatures [14]. |

| Ball Milling Media | For automated homogenization of solid powder precursors, a key step in solid-state synthesis. | Zirconia or stainless-steel milling balls used in robotic preparation stations [16]. |

| Automated Liquid & Solid Dispensers | Enable precise, miniaturized delivery of reagents, ensuring consistency and enabling the micro-scale of HTE. | Liquid handlers for solvents; automated powder dispensers for solid precursors [14]. |

| Robotic Synthesis Laboratory | Integrated system that automates the entire workflow: powder preparation, milling, furnace firing, and product handling. | Custom robotic platforms that can perform 224+ reactions with minimal human intervention [16]. |

| High-Throughput Characterization | Automated analysis tools are required to match the pace of synthesis. | Automated X-ray Diffractometry (XRD) for rapid phase identification and purity analysis [16]. |

| Anticancer agent 242 | Anticancer agent 242, MF:C59H72ClF3N6O5S2, MW:1101.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Gramicidin B | Gramicidin B, CAS:4422-52-0, MF:C97H139N19O17, MW:1843.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The integration of automation and high-throughput methodologies is fundamentally reshaping the landscape of inorganic materials synthesis. The demonstrated advantages in speed, through massive parallelization; reproducibility, via standardized robotic protocols and FAIR data practices; and the strategic exploration of complex chemical spaces, guided by thermodynamic principles and machine learning, collectively address the core bottlenecks in materials discovery. As these platforms become more accessible and their underlying algorithms more sophisticated, automated high-throughput synthesis will transition from a specialized tool to a central pillar of accelerated research and development in materials science and related fields.

Inside the Automated Workflow: Methods and Biomedical Applications of Synthesized Powders

Robotic Platforms for Solid-State Synthesis and Powder Handling

The field of materials science is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by the integration of robotics, artificial intelligence (AI), and high-throughput computation. Traditional research, which has long relied on manual, trial-and-error synthesis and human intuition, is increasingly being augmented—and in some cases replaced—by autonomous laboratories. These platforms are particularly transformative for the solid-state synthesis of inorganic powders, a core process in developing advanced materials for energy storage, catalysis, and electronics. The primary challenge has been the significant gap between the rapid rate of computational materials discovery and the slow, experimental validation of these predictions [3]. Autonomous laboratories, or "A-Labs," are designed to close this gap. They combine computations, historical data, machine learning (ML), and active learning with robotic execution to plan, perform, and interpret experiments continuously and efficiently [3] [19]. This in-depth technical guide examines the core components, workflows, and experimental protocols of these robotic platforms, framing them within the broader thesis of accelerating the high-throughput synthesis of novel inorganic materials.

Core Architectural Principles of Autonomous Platforms

The "Reading-Doing-Thinking" Framework

At the heart of modern robotic platforms is the conceptual framework of material intelligence, which mimics and extends a scientist's capabilities through interconnected cycles of "reading-doing-thinking" [19]. This framework creates a closed-loop system for autonomous discovery, moving beyond simple automation to a more intelligent and adaptive form of experimentation.

- Reading: In this initial phase, the platform ingests and processes vast amounts of existing knowledge. This includes large-scale ab initio phase-stability data from sources like the Materials Project and Google DeepMind to identify potential novel, stable compounds [3]. It also involves using natural-language models trained on the extensive scientific literature to propose initial synthesis recipes based on analogy to known materials [3].

- Doing: The "doing" phase involves the physical execution of experiments. Robotic systems handle all aspects of solid-sample preparation, including powder dispensing, weighing, mixing, and milling. They then transfer the samples to furnaces for heating under controlled conditions before finally preparing them for and conducting characterization, typically via powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) [3] [20].

- Thinking: After characterization, the platform must "think" by interpreting the results. ML models analyze the PXRD patterns to identify phases and quantify their weight fractions [3]. If the yield of the target material is insufficient, an active learning algorithm, grounded in thermodynamics, proposes improved follow-up recipes. This step often involves analyzing observed reaction pathways and using computed reaction energies to avoid intermediates with low driving forces for the target [3].

System Integration and Modularity

Successful platforms are not monolithic but are built on a modular, multi-robot paradigm that integrates specialized stations. A prominent example from the literature uses three distinct robotic units: a liquid-handling platform for crystallization, a dual-arm robot (ABB YuMi) for solid sample preparation (e.g., grinding and transferring), and a mobile manipulator (KUKA KMR iiwa) for transporting samples between stations and loading the diffractometer [20]. This modular approach offers significant flexibility and scalability, allowing different specialized processes to be linked via a central orchestration system like ARChemist [20]. The use of collaborative robots ("cobots") also enables these automated workflows to safely share laboratory space with human researchers [20].

Robotic System Architectures and Workflows

End-to-End Synthesis and Characterization: The A-Lab Workflow

The A-Lab represents a state-of-the-art integrated system specifically for the solid-state synthesis of inorganic powders. Its workflow, which led to the successful synthesis of 41 novel compounds in 17 days of continuous operation, can be broken down into several key stages [3].

Table: Key Performance Metrics of the A-Lab from a 17-Day Run [3]

| Metric | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Target Compounds | 58 | Novel oxides and phosphates predicted to be stable |

| Successfully Synthesized | 41 | Compounds obtained as majority phase (>50% yield) |

| Initial Success Rate | 71% | Overall success rate |

| Potential Success Rate | 78% | With improved computational techniques |

| Synthesis Recipes Tested | 355 | Total number of experiments performed |

| Success of Literature-Inspired Recipes | 35/41 | Number of materials obtained from initial ML-proposed recipes |

The workflow begins with a set of air-stable target materials identified through large-scale ab initio computations [3]. For each compound, the system proposes up to five initial synthesis recipes using a machine learning model that assesses "target similarity" through natural-language processing of historical synthesis data [3]. A second ML model, trained on heating data from the literature, proposes a synthesis temperature [3]. These recipes are then executed by the robotic system, which involves three integrated stations for sample preparation, heating, and characterization [3]. The products are characterized by X-ray diffraction, and the phase composition is determined by probabilistic ML models. If the target yield is below 50%, the active learning loop is engaged.

A Modular Workflow for Automated Powder X-Ray Diffraction

For characterization-centric workflows, a modular robotic setup can achieve full automation of PXRD sample preparation and data collection, a process that is typically manual and laborious. The outlined 12-step process demonstrates how a team of three heterogeneous robots collaborates to prepare crystalline samples for analysis [20].

Table: Breakdown of a 12-Step Modular Robotic PXRD Workflow [20]

| Step | Agent | Action |

|---|---|---|

| 0. Crystal Growth | Chemspeed Platform | Dispense material into solvents for evaporation. |

| 1. Sample Collection | KUKA Mobile Manipulator | Collect rack of crystal samples from Chemspeed. |

| 2. Sample Delivery | KUKA Mobile Manipulator | Deliver samples to the preparation station. |

| 3. Primary Grinding | ABB YuMi (Dual-Arm) | Transfer samples to 1st grinding station for mechanical attrition. |

| 4. Secondary Grinding & Transfer | ABB YuMi (Dual-Arm) | Invert and shake samples to transfer powder to Kapton film. |

| 5. Sample Inversion & Transfer | ABB YuMi (Dual-Arm) | Transfer samples to X-ray diffraction plate. |

| 6. Cap Removal | ABB YuMi (Dual-Arm) | Unscrew vial caps. |

| 7. Cap Placement | ABB YuMi (Dual-Arm) | Invert and place caps into PXRD plate. |

| 8. Plate Collection | KUKA Mobile Manipulator | Collect the prepared PXRD plate. |

| 9. Plate Transport | KUKA Mobile Manipulator | Transport plate to the diffractometer. |

| 10. Instrument Loading | KUKA Mobile Manipulator | Open diffractometer doors and load the plate. |

| 11. Data Collection | PXRD Instrument | Collect diffraction data for the eight samples. |

This workflow highlights the power of modularity. The entire process, from crystal growth to data collection, runs autonomously, with an estimated throughput of 168 samples per week for continuous 24/7 operation, compared to an estimated 40 samples per week for a human researcher [20]. The use of a mobile manipulator to connect fixed stations makes the workflow inherently scalable and adaptable to existing laboratory layouts [20].

Critical Technical Challenges and Solutions

The Powder Handling and Weighing Problem

The reliable robotic handling of powders remains a significant technical hurdle. Powders exhibit complex, non-linear dynamics and their properties, such as flowability, can vary dramatically between materials and are sensitive to environmental conditions like humidity [21]. This makes tasks like precise weighing particularly challenging for a general-purpose robot. To address this, the FLIP (Flowability-Informed Powder weighing) framework was developed. FLIP explicitly incorporates material properties, specifically powder flowability quantified by the Angle of Repose (AoR), into the robotic learning process [21].

The FLIP methodology involves several key steps. First, an automated system measures the AoR of real powders. This real-world flowability data is then used to optimize parameters (e.g., friction, cohesion, adhesion) in a physics-based simulation via Bayesian inference, thereby "closing the sim-to-real gap" [21]. Next, a reinforcement learning (RL) policy for powder weighing is trained in this calibrated, high-fidelity simulation. FLIP also employs a curriculum learning strategy, where the policy is first trained on easy, free-flowing powders before progressively introducing more challenging, cohesive powders [21]. When transferred to a real robot, policies trained with FLIP achieved a significantly lower dispensing error (2.12 ± 1.53 mg) compared to policies trained with standard domain randomization (6.11 ± 3.92 mg) [21].

Analysis of Synthesis Failures and Optimization

Even with advanced automation, synthesis failures provide critical learning opportunities. An analysis of the 17 unobtained targets in the A-Lab study identified four primary failure modes [3]:

- Slow Reaction Kinetics: This was the most common issue, affecting 11 of the 17 failed targets. It was often associated with reaction steps that had a low thermodynamic driving force (<50 meV per atom) [3].

- Precursor Volatility: The loss of precursor materials during heating due to evaporation.

- Amorphization: The formation of non-crystalline products instead of the desired crystalline phase.

- Computational Inaccuracy: Instances where the predicted stability of the target material was incorrect.

The A-Lab's active learning cycle, powered by the ARROWS³ algorithm, was designed to overcome some of these hurdles. It operates on two key hypotheses: that solid-state reactions tend to occur pairwise, and that intermediate phases with a small driving force to form the target should be avoided [3]. The lab continuously builds a database of observed pairwise reactions, which allows it to infer the products of some recipes without testing them, thereby reducing the experimental search space by up to 80% [3]. Furthermore, it can prioritize synthesis routes that form intermediates with a large driving force to proceed to the final target, as demonstrated in the optimized synthesis of CaFe₂P₂O₉ [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The operation of these robotic platforms relies on a suite of specialized equipment and materials that form the basic toolkit for autonomous solid-state research.

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Robotic Solid-State Synthesis

| Item | Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Powders | Raw materials for solid-state reactions. | Purity, particle size distribution, and flowability (Angle of Repose) are critical for reproducibility and robotic handling [3] [21]. |

| Robotic Platforms (e.g., Chemspeed, KUKA, ABB YuMi) | Automation of liquid dispensing, solid handling, and sample transport. | Integration requires a central orchestration system (e.g., ARChemist). Modularity and mobility are key for flexible workflows [20]. |

| Box Furnaces | High-temperature heating for solid-state reactions. | Integrated into the robotic workflow with automated loading/unloading [3]. |

| Powder X-Ray Diffractometer (PXRD) | Primary characterization method for identifying crystalline phases and quantifying yield. | Must be equipped for automated sample loading, often via a multi-well plate [3] [20]. |

| Analytical Balance | High-precision weighing of powder samples. | Provides real-time feedback for robotic powder dispensing policies [21] [22]. |

| Probabilistic ML Models for XRD Analysis | Automated phase identification and weight fraction quantification from diffraction patterns. | Trained on experimental structures (e.g., ICSD) and corrected ab initio data for novel materials [3]. |

| Angle of Repose (AoR) Measurement Kit | Quantifies powder flowability, a key physical property. | Essential for calibrating simulations (e.g., in the FLIP framework) to improve robotic handling of new materials [21]. |

| Decatromicin B | Decatromicin B, MF:C45H56Cl2N2O10, MW:855.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Cefamandole | Cefamandole, CAS:30034-03-8; 34444-01-4, MF:C18H18N6O5S2, MW:462.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Robotic platforms for solid-state synthesis and powder handling are redefining the pace and methodology of materials discovery. The integration of AI for planning and interpretation, with robust robotics for physical execution, has demonstrated a capability to autonomously discover and synthesize novel inorganic compounds at a scale and speed that was previously unattainable. As these platforms evolve, the focus will be on enhancing their material intelligence—their ability to handle an ever-wider range of complex materials, to learn more efficiently from failures, and to seamlessly integrate computational predictions with experimental reality. The convergence of accurate simulation, adaptive robot learning, and modular hardware architecture, as exemplified by the A-Lab, FLIP, and modular PXRD workflows, points toward a future where autonomous laboratories are indispensable partners in the global quest for new functional materials.

AI-Driven Precursor Selection and Reaction Planning

The accelerated discovery and synthesis of novel materials are critical for advancements in energy storage, catalysis, and pharmaceutical development. Traditional experimental approaches, which often rely on iterative, human-guided experimentation, create a significant bottleneck between computational prediction and physical realization. This whitepaper examines the transformative role of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in automating precursor selection and reaction planning, with a specific focus on the high-throughput synthesis of inorganic powders. By integrating robotics, machine learning (ML), and active learning, these autonomous systems are closing the gap between in-silico screening and laboratory synthesis, thereby revolutionizing materials development workflows [3].

Core AI Methodologies and Algorithms

The integration of AI into synthesis planning involves several sophisticated computational approaches that mimic and extend human expert knowledge.

Literature-Based Analogy and Natural Language Processing

Initial synthesis recipes are frequently generated using models trained on vast historical datasets. For instance, natural-language models process extensive synthesis literature to assess target material "similarity," thereby proposing precursor sets based on analogous known reactions [3]. This approach mimics a human chemist's intuition to base initial attempts on related successful syntheses. In one implementation, a framework powered by a large language model (LLM) employs a "Literature Scouter" agent to sift through academic databases, extract relevant synthetic methods, and summarize detailed experimental procedures, significantly accelerating the initial information gathering phase [23].

Active Learning with Thermodynamic Guidance

When initial recipes fail, active learning algorithms close the loop by proposing improved experiments. A key algorithm in this domain is Autonomous Reaction Route Optimization with Solid-State Synthesis (ARROWS3) [3] [24].

ARROWS3 leverages domain knowledge grounded in thermodynamics. Its workflow can be summarized as follows:

- Initial Ranking: Precursor sets are initially ranked by the thermodynamic driving force (ΔG) to form the target material, as calculated using data from sources like the Materials Project [24].

- Pathway Analysis: Proposed precursors are tested experimentally at multiple temperatures. Techniques like X-ray diffraction (XRD) coupled with machine-learned analysis identify the intermediate phases formed during the reaction [3] [24].

- Knowledge Integration: The algorithm identifies the specific pairwise reactions that lead to observed intermediates. It then uses this growing database of pairwise reactions to predict intermediates for untested precursor sets [3].

- Iterative Optimization: In subsequent iterations, ARROWS3 prioritizes precursor sets predicted to avoid intermediates that consume a large portion of the driving force. The goal is to select a pathway that retains a large thermodynamic driving force (ΔG') for the critical target-forming step, thereby increasing the likelihood of a high-yield synthesis [24].

This method has proven more efficient at identifying effective precursors than black-box optimization algorithms, requiring substantially fewer experimental iterations [24].

Generative Models for Inverse Materials Design

Generative models represent a paradigm shift from screening known materials to creating entirely new ones. MatterGen is a diffusion-based generative model designed specifically for inorganic materials [6]. It generates stable, diverse crystal structures by gradually refining atom types, coordinates, and the periodic lattice. A key advantage is its adaptability; the base model can be fine-tuned with adapter modules to steer the generation toward materials with user-specified properties, such as desired chemical composition, symmetry, and target electronic or magnetic properties [6]. This enables true inverse design, where materials are created from a set of property constraints.

Quantitative Performance Data

The effectiveness of autonomous laboratories is demonstrated by compelling experimental results. The table below summarizes the performance of two prominent systems, the A-Lab and MatterGen, alongside benchmarking data for the ARROWS3 algorithm.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of AI-Driven Synthesis Systems

| System / Metric | Reported Performance | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| A-Lab (Autonomous Lab) | 71% success rate (41 of 58 novel compounds synthesized) [3]. | 17 days of continuous operation targeting novel, computationally predicted inorganic powders [3]. |

| MatterGen (Generative Model) | >2x higher success rate at generating new, stable materials compared to prior models; >10x closer to DFT local energy minimum [6]. | Generation of stable, diverse inorganic materials across the periodic table for inverse design [6]. |

| ARROWS3 (Optimization Algorithm) | Identified all effective synthesis routes for a benchmark target while requiring fewer experimental iterations than Bayesian optimization or genetic algorithms [24]. | Validation on experimental datasets from over 200 synthesis procedures, including the optimization of precursors for metastable targets [24]. |

The following table provides a more granular look at the experimental outcomes from the A-Lab's operation, categorizing the results and identifying primary failure modes.

Table 2: Detailed Analysis of A-Lab Synthesis Outcomes for 58 Target Materials

| Category | Number of Targets | Key Findings & Details |

|---|---|---|

| Successfully Synthesized | 41 | 35 were made using literature-inspired recipes; 6 were optimized via active learning [3]. |

| Failed Syntheses | 17 | Primary failure modes identified: sluggish kinetics (11 targets), precursor volatility, amorphization, and computational inaccuracies [3]. |

| Active Learning Impact | 9 | Active learning identified routes with improved yield for 9 targets, 6 of which had zero initial yield [3]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear technical roadmap, this section outlines the standard protocols employed in autonomous synthesis platforms.

A-Lab Workflow for Solid-State Synthesis

The A-Lab executes a fully integrated, closed-loop workflow for synthesizing and characterizing inorganic powders [3].

- Target Identification: Air-stable target materials are selected from computational databases like the Materials Project, which provides ab initio phase-stability data [3].

- Precursor Selection and Recipe Generation: Up to five initial synthesis recipes are generated using ML models trained on literature data. A second model proposes a synthesis temperature [3].

- Robotic Execution:

- Preparation: Precursor powders are dispensed and mixed by a robotic system before being transferred into alumina crucibles [3].

- Heating: A robotic arm loads crucibles into one of four box furnaces for heating [3].

- Characterization: After cooling, samples are ground into a fine powder and analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD) [3].

- Data Analysis and Decision Making:

- Phase Identification: The XRD patterns are analyzed by probabilistic ML models to extract phase and weight fractions of the products. For novel materials, diffraction patterns are simulated from computed structures [3].

- Refinement: Phases identified by ML are confirmed with automated Rietveld refinement [3].

- Iteration: If the target yield is below a threshold (e.g., 50%), the active learning cycle (e.g., ARROWS3) is triggered to propose a new set of precursors and/or conditions, and the process repeats [3].

High-Throughput Feasibility Screening for Organic Reactions

While focused on inorganic powders, the principles of automation are transferable. A protocol for high-throughput feasibility screening of acid-amine coupling reactions demonstrates this scalability [25].

- Chemical Space Curation: Substrates (acids and amines) are down-sampled from commercially available compounds to ensure diversity and representativeness of patent data [25].

- Automated Reaction Execution: An HTE platform (e.g., ChemLex's CASL-V1.1) conducts reactions in 200–300 μL volumes. The platform automates liquid handling for 11,669 distinct reactions within 156 instrument hours [25].

- Analysis and Yield Determination: Reaction outcomes are analyzed using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS). The uncalibrated ratio of ultraviolet (UV) absorbance is used to determine yields rapidly [25].

- Model Training and Feasibility Prediction: A Bayesian neural network (BNN) is trained on the HTE data. The model achieves a feasibility prediction accuracy of 89.48%, providing a powerful oracle for ruling out non-viable reactions [25].

Workflow and System Diagrams

The logical flow of the ARROWS3 algorithm is complex. The diagram below outlines its core decision-making process for optimizing precursor selection.

The following diagram illustrates the integrated, closed-loop workflow of a fully autonomous laboratory, as exemplified by the A-Lab.

The implementation of AI-driven synthesis relies on a combination of computational resources, physical hardware, and chemical databases. The following table details key components of this ecosystem.

Table 3: Essential Resources for AI-Driven Materials Synthesis

| Resource Name | Type | Function in AI-Driven Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Materials Project [3] [6] | Computational Database | Provides ab initio calculated data on phase stability and reaction energies for initial target screening and thermodynamic guidance. |

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [3] [6] | Experimental Database | Serves as a source of known crystal structures for training machine learning models for phase identification from XRD data. |

| ARROWS3 Algorithm [3] [24] | Software Algorithm | Actively learns from experimental outcomes to optimize precursor selection by avoiding low-driving-force intermediates. |

| Autonomous Robotic Platform (e.g., A-Lab) [3] | Hardware System | Executes the physical tasks of powder dispensing, mixing, heating, and sample transfer for continuous, high-throughput experimentation. |

| MatterGen [6] | Generative Model | Acts as a foundational model for the inverse design of novel, stable inorganic crystals with targeted properties. |

| Large Language Model (e.g., GPT-4) [23] | AI Model | Powers specialized agents for literature mining, experimental design, and result interpretation, making the system accessible via natural language. |

AI-driven precursor selection and reaction planning have transitioned from theoretical concepts to powerful tools capable of accelerating materials discovery. By integrating computational thermodynamics, machine learning, and robotics, systems like the A-Lab and algorithms like ARROWS3 and MatterGen are demonstrating high success rates in synthesizing novel inorganic materials. These platforms not only enhance throughput but also codify deep chemical insights, creating a new paradigm where the synthesis loop is closed autonomously. This progression is pivotal for achieving the ultimate goal of automated high-throughput synthesis, promising to dramatically shorten development cycles in fields ranging from drug development to renewable energy.

Machine Learning for Real-Time Analysis of X-ray Diffraction Data

The integration of machine learning (ML) for the real-time analysis of X-ray diffraction (XRD) data is fundamentally transforming high-throughput research in inorganic materials. Traditional XRD analysis methods, such as Rietveld refinement, are computationally intensive and time-consuming, creating a critical bottleneck in autonomous discovery pipelines [26] [27]. This whitepaper details how convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and other ML models are being deployed to interpret XRD patterns orders of magnitude faster than conventional techniques, enabling on-the-fly phase identification and quantification during automated experiments [3] [27]. Framed within the context of automated high-throughput synthesis of inorganic powders, this document provides a technical guide to the architectures, training methodologies, and experimental protocols that make real-time, AI-driven XRD analysis a reality, thereby closing the loop in autonomous laboratories.