Analytical Stress Calculation in Inorganic Materials: From Fundamentals to Pharmaceutical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of analytical stress calculation methodologies for inorganic materials, a critical area for ensuring the quality and stability of pharmaceuticals.

Analytical Stress Calculation in Inorganic Materials: From Fundamentals to Pharmaceutical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of analytical stress calculation methodologies for inorganic materials, a critical area for ensuring the quality and stability of pharmaceuticals. We explore the foundational principles of the elastic stiffness tensor and its derivation via Density Functional Theory (DFT), establishing a basis for understanding material behavior under stress. The scope extends to methodological applications, including high-throughput computational screening and machine-learned potentials for rapid property prediction. The article further addresses troubleshooting calculation inaccuracies and optimizing protocols for greater reliability. Finally, we cover the validation of computational results against experimental techniques like Brillouin spectroscopy and Resonant Ultrasound Spectroscopy (RUS), and discuss the crucial implications of material mechanical properties for drug development, from formulation stability to impurity control.

Understanding Stress and Elasticity: The Foundation of Material Stability

The elastic stiffness tensor, also known as the elastic modulus tensor or simply the elasticity tensor, is a fundamental fourth-rank tensor (denoted as C) that provides a complete description of the stress-strain relationship in a linear elastic material [1]. In crystalline materials, physical properties like elasticity are direction-dependent due to the anisotropic arrangement of atoms in the crystal lattice [2]. Unlike isotropic materials whose elastic properties can be described by just two independent constants (Lamé constants λ and μ), crystalline materials require a more complex description because their mechanical response varies with direction relative to the crystallographic axes [1].

The defining equation for the elasticity tensor is written as: Tᵢⱼ = CᵢⱼₖₗEₖₗ where Tᵢⱼ represents the components of the stress tensor, and Eₖₗ represents the components of the strain tensor [1]. In its most general form for a triclinic crystal, the stiffness tensor possesses 81 independent components. However, this number is significantly reduced by the intrinsic symmetries of the stress and strain tensors, as well as the point group symmetry of the crystal structure itself [3] [1].

Fundamental Theory and Mathematical Formalism

Tensor Symmetries and Neumann's Principle

The elasticity tensor is subject to several fundamental symmetries that dramatically reduce its number of independent components. The intrinsic symmetries of the tensor are:

- Cᵢⱼₖₗ = Cⱼᵢₖₗ and Cᵢⱼₖₗ = Cᵢⱼₗₖ (due to the symmetry of the stress and strain tensors)

- Cᵢⱼₖₗ = Cₖₗᵢⱼ (if the stress derives from an elastic energy potential) [1]

These intrinsic symmetries alone reduce the number of independent components from 81 to 21 for a triclinic crystal system [1]. The most important principle governing the form of the elasticity tensor for crystalline materials is Neumann's Principle, which states that: "the symmetry elements of any physical property of a crystal must include the symmetry elements of the point group of the crystal" [3]. This means that the tensors describing material properties must be invariant under all symmetry operations of the crystal's point group, imposing specific conditions on the tensor components depending on the crystal symmetry [3].

Tensor Transformation Laws

When the coordinate system is rotated, the components of the elasticity tensor transform according to the standard rule for fourth-rank tensors: C'ᵢⱼₖₗ = RᵢₚRⱼₚRₖᵣRₗₛCₚₚᵣₛ where Rᵢⱼ are the components of the rotation matrix, and C'ᵢⱼₖₗ are the components in the new coordinate system [1]. This transformation law is essential for analyzing how elastic properties appear in different coordinate systems, such as when comparing crystallographic coordinates with laboratory measurement coordinates [2].

Effects of Crystal Symmetry on the Stiffness Tensor

The specific form of the elasticity tensor is dictated by the crystal system and point group symmetry. The following table summarizes how crystal symmetry affects the number of independent components and the general form of the stiffness tensor:

Table 1: Independent Components of the Elastic Stiffness Tensor by Crystal Family

| Crystal Family | Point Group | Number of Independent Components | General Form |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triclinic | All | 21 | Full 6×6 matrix |

| Monoclinic | All | 13 | 12 non-zero components, 7 off-diagonal zeros |

| Orthorhombic | All | 9 | 9 non-zero components, 12 off-diagonal zeros |

| Tetragonal | Câ‚„, Sâ‚„, Câ‚„h | 7 | 7 non-zero components, 14 off-diagonal zeros |

| Tetragonal | Câ‚„v, Dâ‚‚d, Dâ‚„, Dâ‚„h | 6 | 6 non-zero components, 15 off-diagonal zeros |

| Rhombohedral | C₃, S₆ | 7 | 7 non-zero components, 14 off-diagonal zeros |

| Rhombohedral | C₃v, D₆, D₃d | 6 | 6 non-zero components, 15 off-diagonal zeros |

| Hexagonal | All | 5 | 5 non-zero components, 16 off-diagonal zeros |

| Cubic | All | 3 | 3 non-zero components, 18 off-diagonal zeros |

| Isotropic | - | 2 | 2 non-zero components (λ and μ) |

For cubic crystals, the elasticity tensor has components that can be expressed as: Cᵢⱼₖₗ = λgᵢⱼgₖₗ + μ(gᵢₖgⱼₗ + gᵢₗgₖⱼ) + α(aᵢaⱼaₖaₗ + bᵢbⱼbₖbₗ + cᵢcⱼcₖcₗ) where a, b, and c are the orthogonal crystal unit vectors, λ and μ are Lamé constants, and α is an additional constant required for cubic crystals [1].

For isotropic materials (a special case not belonging to any crystal system), the elasticity tensor simplifies further to: Cᵢⱼₖₗ = λδᵢⱼδₖₗ + μ(δᵢₖδⱼₗ + δᵢₗδₖⱼ) where only two independent constants (λ and μ) are needed to fully characterize the elastic response [1].

Experimental Protocols for Elastic Constant Determination

Dual-Wavelength Infrared Photoelasticity

Infrared photoelasticity has emerged as a powerful technique for determining elastic constants and analyzing stress distributions in semiconductor materials, particularly those relevant to organic electronics research [4]. The following workflow illustrates the experimental process:

Sample Preparation

- Material: Double-sided polished (111) monocrystalline silicon wafers [4]

- Dimensions: Rectangular strips (48.0 mm × 5.0 mm × 0.525 mm) or discs (diameter 10 mm, thickness 1 mm) [4]

- Preparation: Wafers are cut into specific geometries depending on the experiment type (three-point bending, four-point bending, or pressurized disc) [4]

Optical Setup Configuration

- Light Sources: Two infrared lasers with wavelengths of 980 nm and 1310 nm [4]

- Optical Components: Infrared polarizers, quarter-wave plates, and lenses specifically designed for infrared wavelengths [4]

- Detection: Infrared camera with sensitivity in the 800-1500 nm range [4]

- Configuration: Circular polariscope arrangement with rotating optical elements for phase-shifting measurements [4]

Phase-Shifting Measurement Protocol

- System Calibration: Align all optical components and ensure proper polarization state generation [4]

- Five-Step Phase-Shifting: Capture photoelastic images at five different polarization arrangements for each wavelength [4]

- Intensity Measurement: Record light intensity values for each pixel across all images [4]

- Phase Calculation: Compute isoclinic (θ) and isochromatic (δ) values using the intensity equations [4]

The basic equations for phase calculation are:

- I = I₀sin²(δ/2) for circular polariscope

- δ = (2πCₜ/λ)Δt(σ₠- σ₂) for stress-induced retardation where I is light intensity, I₀ is initial intensity, δ is phase retardation, Cₜ is stress-optic coefficient, λ is wavelength, Δt is thickness, and (σ₠- σ₂) is the principal stress difference [4].

Automatic Phase-Unwrapping

- Reference Point Identification: Locate reference points using the change rate K calculated from fifth-step images at two wavelengths [4]

- AQGPU Algorithm: Apply Adaptive Quality Map Guided Path algorithm for robust phase-unwrapping in complex stress fields [4]

- Validation: Compare results with known stress distributions from theoretical models [4]

X-Ray Diffraction Methods

X-ray diffraction provides an alternative approach for determining elastic constants through measurement of lattice strain distributions:

Experimental Setup

- X-Ray Source: Laboratory X-ray generator or synchrotron radiation source [5]

- Detector: Position-sensitive detector or area detector for diffraction pattern collection [5]

- Sample Stage: Eulerian cradle for precise orientation control [5]

Measurement Protocol

- Orientation Determination: Measure crystal orientation using electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) or X-ray diffraction [5]

- Lattice Strain Measurement: Record diffraction patterns at multiple sample orientations (sin²ψ method) [5]

- Elastic Constant Calculation: Determine X-ray elastic constants from the slope of d vs. sin²ψ plots [5]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials and Equipment for Elastic Constant Determination

| Item | Specification | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Monocrystalline Silicon Wafers | (111) orientation, double-sided polished | Primary test material for semiconductor stress analysis [4] |

| Infrared Lasers | 980 nm and 1310 nm wavelengths | Light sources for infrared photoelasticity [4] |

| Infrared Polarizers | Near-IR optimized (800-1500 nm range) | Polarization control in photoelastic setup [4] |

| Quarter-Wave Plates | Infrared wavelengths | Circular polarization generation [4] |

| Infrared Camera | 800-1500 nm sensitivity, high quantum efficiency | Detection of photoelastic fringe patterns [4] |

| X-Ray Diffractometer | With Eulerian cradle | Lattice strain measurement for elastic constant determination [5] |

| Deformation Apparatus | In-situ tensile/compressive loading | Stress application during elastic constant measurement [5] |

| Antibacterial agent 28 | Antibacterial agent 28, MF:C40H64Br2N4O4, MW:824.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| PSA1 141-150 acetate | PSA1 141-150 acetate, MF:C57H97N13O15S, MW:1236.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Stress-Optic Coefficient Calibration

The stress-optic coefficient (Cₜ) is a fundamental material parameter that must be precisely calibrated for accurate stress analysis:

Four-Point Bending Calibration

- Sample Loading: Apply known bending moment to rectangular beam specimen [4]

- Phase Measurement: Record isochromatic phase values at different load levels [4]

- Coefficient Calculation: Determine Cₜ from the slope of δ vs. applied stress plot [4]

Pressurized Disc Method

- Pressure Application: Apply known hydrostatic pressure to disc specimen [4]

- Fringe Pattern Analysis: Measure fringe order distribution across the disc [4]

- Validation: Compare with theoretical stress distribution for pressurized disc [4]

Several factors can affect the accuracy of elastic constant determination:

- Transmission Quality: Inhomogeneities in material transmission can distort photoelastic measurements [4]

- Optical Component Imperfections: Polarizability and chromatic aberration in infrared optical components affect measurement accuracy [4]

- Noise Limitations: Infrared cameras typically have lower signal-to-noise ratios compared to visible-light cameras [4]

- Calibration Accuracy: Consistent calibration of stress-optical coefficients is challenging but critical [4]

Applications in Organic Materials Research

The characterization of elastic stiffness tensors has significant implications for organic electronic and semiconductor devices:

- Residual Stress Analysis: Determining processing-induced stresses in device structures [4]

- Mechanical Reliability Assessment: Predicting device failure under mechanical loading [4]

- Interface Characterization: Analyzing stress transfer at material interfaces in multilayer devices [5]

- Process Optimization: Guiding manufacturing processes to minimize detrimental stress concentrations [4]

The relationship between crystal symmetry and elastic properties provides fundamental insights for materials design, enabling the development of organic semiconductors with tailored mechanical response for flexible electronics applications.

Linking Atomic Bonding to Macroscopic Elastic Properties

The elastic properties of a material, such as its Young's modulus, are fundamental design parameters in engineering and materials science. While these properties are measured on a macroscopic scale, their origins lie in the atomic-scale interactions between atoms. This application note details the foundational principles and practical protocols for linking the stiffness of atomic bonds to the macroscopic elastic response of inorganic materials, providing researchers with a framework for analysis and prediction within the broader context of analytical stress calculation.

Theoretical Foundation: From Atomic Bonds to Elastic Modulus

The macroscopic elastic modulus of a material is a direct manifestation of the resistance of atomic bonds to deformation.

Types of Atomic Bonds

Chemical bonding arises from electrostatic interactions, and the primary classes relevant to inorganic materials are [6]:

- Ionic Bonding: Found in materials like NaCl, where an electron is transferred from one atom to another, creating ions that attract electrostatically. The attractive force follows Coulomb's law.

- Metallic Bonding: Found in metals like iron and copper, where outer electrons are delocalized into a "sea" that binds the positively charged atomic cores.

- Covalent Bonding: Found in materials like diamond, where atoms share electrons in directional bonds, creating a region of increased electron density that attracts both nuclei.

The Bond Energy Curve

The potential energy ( U ) between two atoms varies with the separation distance ( r ). The force between atoms is the derivative of this energy, ( f = dU/dr ). At the equilibrium bond length, the net force is zero. The elastic stiffness of the bond is related to the curvature ( (d^2U/dr^2) ) of this energy function at the equilibrium point. A steeper curvature indicates a stiffer bond, which translates to a higher macroscopic elastic modulus [6].

For a perfect ionic crystal, the total electrostatic binding energy can be computed by summing the contributions from all ions in the lattice. For a sodium ion in the NaCl structure, this energy is given by ( U_{attr} = -ACe^2/r ), where ( A ) is the Madelung constant (1.747558 for NaCl), which accounts for the specific lattice geometry [6].

Quantitative Data: Correlating Bond Proportion to Modulus

The "rule of mixture" applied to atomic bonds, rather than atoms, has proven effective in predicting elastic modulus in complex systems like metallic glasses. The following table summarizes data from a molecular dynamics study on a ZrxCu100-x system, demonstrating this correlation [7].

Table 1: Elastic Modulus and Bond Proportions in Zr-Cu Metallic Glasses

| Zr Content (at%) | Young's Modulus, E (GPa) | Zr-Zr Bond Proportion | Zr-Cu Bond Proportion | Cu-Cu Bond Proportion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 96.5 | 4.8% | 31.4% | 63.8% |

| 35 | 101.2 | 13.2% | 42.6% | 44.2% |

| 50 | 105.8 | 23.8% | 48.4% | 27.8% |

| 65 | 99.3 | 37.8% | 46.2% | 16.0% |

The data shows a non-monotonic relationship between composition and modulus, which peaks near a 50:50 composition. This peak correlates with a high proportion of stiff Zr-Cu bonds, illustrating that the weighted average of the stiffness of the different bond types (Zr-Zr, Cu-Cu, and Zr-Cu) dictates the macroscopic elasticity [7].

Experimental & Computational Protocols

Protocol 1: Computational Determination of Elastic Tensor via DFT

This protocol outlines the use of Density Functional Theory (DFT) to calculate the single-crystal elastic stiffness tensor (( C_{ij} )), a fundamental property from which all other elastic moduli are derived [8].

1. Software and Functional Selection:

- Software: Employ a validated DFT code such as CASTEP [8].

- Exchange-Correlation Functional: For highest accuracy in predicting elastic properties, the meta-GGA functional RSCAN is recommended. Alternatively, the GGA functionals Wu-Chen or PBESOL are also suitable choices [8].

2. Calculation Setup:

- Plane-Wave Cutoff Energy: Set based on convergence tests for the relevant elements, typically in the range of 330 to 800 eV [8].

- Pseudopotentials: Use ultrasoft or norm-conserving pseudopotentials [8].

- k-point Mesh: Select a sufficiently dense k-point mesh for Brillouin zone sampling to ensure numerical convergence of the total energy and stresses.

3. Elastic Tensor Calculation:

- Apply a set of finite positive and negative strains to the optimized unit cell.

- For each strain configuration, calculate the resulting stress tensor using DFT.

- The elastic coefficients ( c_{ij} ) are determined from the linear relationship between the applied strain and the calculated stress [8].

4. Data Analysis:

- The calculated ( c_{ij} ) components must satisfy the mechanical stability conditions for the crystal's symmetry.

- Derive macroscopic properties like the bulk modulus (B), shear modulus (G), and Young's modulus (E) from the elastic tensor using standard homogenization schemes (e.g., Voigt-Reuss-Hill average) [8].

Protocol 2: Experimental Validation via Resonant Ultrasound Spectroscopy (RUS)

This protocol describes the use of RUS to measure the elastic tensor experimentally, providing ground-truth data for validating computational models [8].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Material: A single crystal of the inorganic material under study.

- Geometry: Prepare a sample with a regular geometry (e.g., rectangular parallelepiped) and polished surfaces. The sample must be large enough for the measurement technique, typically several millimeters in size [8].

- Orientation: The crystallographic orientation of the sample must be known.

2. Data Acquisition:

- The sample is lightly placed between two piezoelectric transducers.

- One transducer sweeps through a frequency range of ultrasound, exciting mechanical resonances in the sample. The other transducer measures the sample's response.

- A spectrum of resonant frequencies is recorded [8].

3. Data Analysis and Inversion:

- The measured resonant frequencies are compared to the frequencies predicted by an analytical model for a given set of ( c_{ij} ) values.

- An iterative inverse problem is solved to find the set of ( c_{ij} ) components that minimizes the difference between the measured and predicted resonant frequencies [8].

4. Accuracy Consideration:

- RUS is highly accurate but can have large errors for certain ( c_{ij} ) components if no resonant frequencies are sensitive to them. Cross-validation with other techniques (e.g., Brillouin spectroscopy) or DFT calculations is recommended in such cases [8].

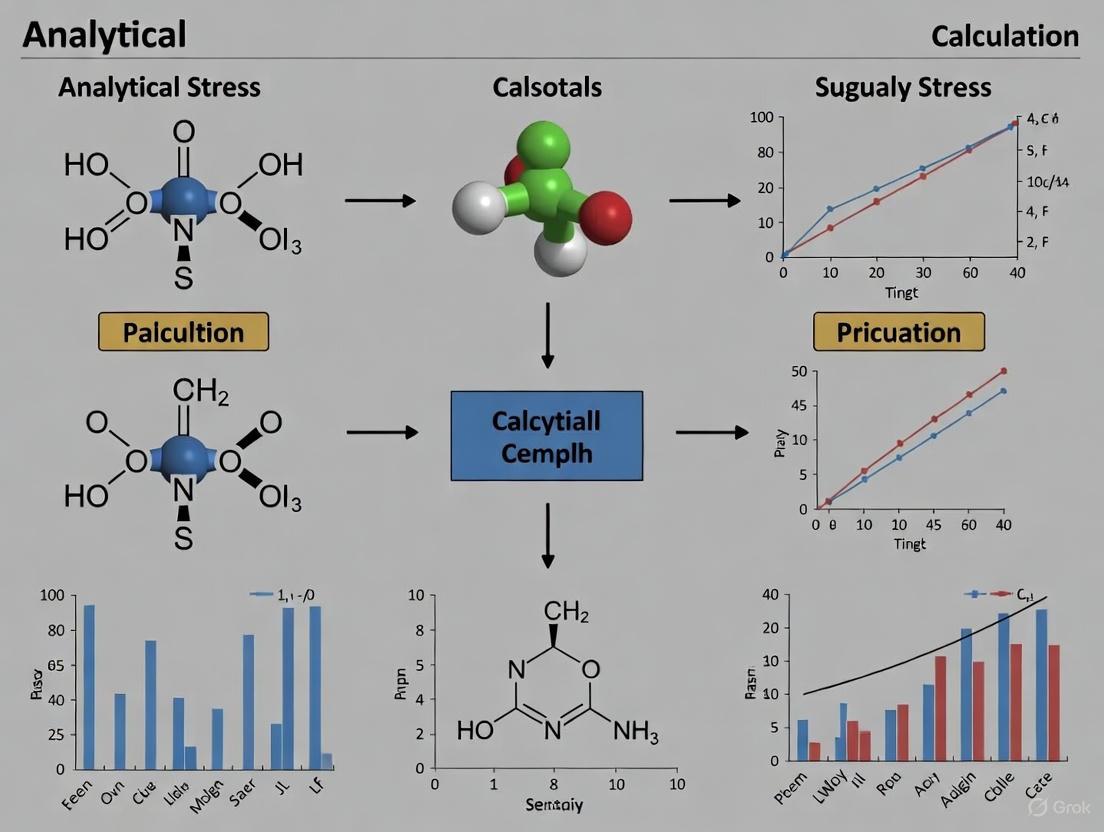

Workflow Diagram: Linking Atomic Structure to Macroscopic Properties

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow connecting computational and experimental methods to establish the structure-property relationship.

Diagram 1: Integrated workflow for determining elastic properties.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Tools for Elastic Property Research

| Item Name | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| CASTEP Software | A leading DFT code for performing first-principles quantum mechanical calculations to determine the elastic tensor and other properties from atomic structure [8]. |

| RSCAN Functional | A meta-GGA exchange-correlation functional within DFT that provides high accuracy for predicting elastic coefficients and related mechanical properties [8]. |

| Single Crystal Sample | A high-quality, oriented single crystal of the material under study is essential for experimental determination of the full elastic tensor via methods like RUS [8]. |

| Resonant Ultrasound Spectrometer | The experimental apparatus used to excite and measure the mechanical resonant frequencies of a sample, from which the complete set of ( c_{ij} ) is derived [8]. |

| Pseudopotential Library | A collection of pre-generated, validated pseudopotentials for different elements, which replace core electrons in DFT calculations to improve computational efficiency [8]. |

| 4H-3,1-Benzoxazine | 4H-3,1-Benzoxazine|High-Quality Research Chemical |

| 2-Fluoro-2-methylbutanoate | 2-Fluoro-2-methylbutanoate|High-Purity Reference Standard |

In inorganic materials research, the accurate calculation of internal stresses and the prediction of mechanical behavior hinge on a fundamental understanding of a material's elastic response. The elastic constant tensor (C~ij~) provides a complete description of how a crystalline solid deforms under applied stress within its elastic limit [9]. This tensor is not merely a set of numbers; it encodes the nature of interatomic bonding and correlates directly with macroscopic properties such as hardness, ductility, and thermal conductivity [9] [8]. For researchers engaged in analytical stress calculation, extracting meaningful physical properties—namely the bulk modulus, shear modulus, and elastic anisotropy—from the full elastic tensor is a critical procedural step. This Application Note details the protocols for deriving these key properties, their significance in materials design, and the experimental-computational frameworks used for their determination, with a specific focus on applications in inorganic materials research.

Theoretical Background and Key Definitions

The linear elastic response of a material is described by the generalized Hooke's Law, which relates the second-rank stress tensor (σ) to the second-rank strain tensor (ε) via a fourth-rank elastic stiffness tensor (C). In Voigt notation, this tensor is represented as a 6x6 symmetric matrix, reducing the maximum number of independent components from 81 to 21 for a triclinic crystal system [9] [10] [11].

- Bulk Modulus (K) is a measure of a material's resistance to uniform compression. It defines the relationship between a hydrostatic pressure and the resulting volumetric strain. A high bulk modulus indicates low compressibility, a critical property for materials subjected to high-pressure environments [11] [12].

- Shear Modulus (G) quantifies a material's resistance to shape change under shear stress. It is intimately linked to a material's hardness and its ability to resist plastic deformation [11].

- Young's Modulus (E) and Poisson's Ratio (ν) are frequently used engineering constants derived from K and G. Young's Modulus describes the stiffness in uniaxial tension, while Poisson's Ratio describes the transverse strain under axial stretch [13].

- Elastic Anisotropy describes the variation of these elastic properties with crystallographic direction. This anisotropy is a direct consequence of the crystal structure and bonding and can significantly influence micro-cracking, plastic deformation initiation, and mechanical performance in single crystals and polycrystals with texture [14] [11] [12].

Computational Protocol: Calculating Elastic Properties from First Principles

Density Functional Theory (DFT) has become the standard computational method for predicting the full elastic tensor of inorganic crystalline compounds in a high-throughput manner [9] [8]. The following protocol, as implemented by major initiatives like the Materials Project, provides a robust framework for these calculations [9] [10].

Step-by-Step Methodology

Initial Structural Relaxation: The crystal structure is first fully relaxed (including lattice parameters and internal atomic coordinates) using DFT until the forces on atoms and the components of the stress tensor are minimized to a predefined tolerance (e.g., 0.01 eV/Ã… for forces) [10] [13]. This provides the ground-state equilibrium structure.

Application of Finite Strains: The relaxed structure is subjected to a set of six independent, finite deformations, each corresponding to one of the independent components of the Green-Lagrange strain tensor [9] [10]. For each strain type, multiple magnitudes (e.g., δ = -0.01, -0.005, +0.005, +0.01) are applied to ensure robust linear fitting. The deformation gradient is applied to the lattice vectors, and for each deformed configuration, the internal ionic degrees of freedom are allowed to relax [10].

Stress Tensor Calculation: For each of the resulting deformed structures (typically 4 magnitudes × 6 independent strains = 24 structures), a single-point DFT calculation is performed to compute the full 3x3 stress tensor [9] [10].

Linear Regression for Elastic Constants: For each of the six strain types, the calculated stresses are plotted against the applied strain magnitudes. The elements of a row (and column) in the 6x6 elastic constant matrix (C~ij~) are determined from the linear fit of the stress-strain data, following the constitutive relation of linear elasticity:

[σ] = [C][ε][9].Tensor Construction and Mechanical Stability Check: The full symmetric elastic tensor is assembled from the fitted constants. The tensor must satisfy the Born-Huang mechanical stability criteria for the given crystal system (e.g., for a rhombohedral crystal like magnesite: C~44~ > 0, C~11~ > |C~12~|, etc.) [12]. A failure to meet these criteria indicates computational inaccuracies or intrinsic mechanical instability.

Derived Property Calculations

From the calculated elastic tensor, the key physical properties are derived as follows:

Bulk and Shear Modulus (Voigt-Reuss-Hill Average): The isotropic bulk (K) and shear (G) moduli for polycrystalline materials are calculated using the Voigt-Reuss-Hill (VRH) averaging scheme [10] [13] [12]. The Voigt average assumes uniform strain and provides an upper bound for the moduli, while the Reuss average assumes uniform stress and provides a lower bound. The Hill average is the arithmetic mean of the Voigt and Reuss bounds and is considered the best estimate [11].

- Voigt Bounds:

B_V = [(C~11~ + C~22~ + C~33~) + 2(C~12~ + C~13~ + C~23~)] / 9G_V = [(C~11~ + C~22~ + C~33~ - C~12~ - C~13~ - C~23~) + 3(C~44~ + C~55~ + C~66~)] / 15[12] - Reuss Bounds (using the elastic compliance tensor S~ij~):

B_R = 1 / [(S~11~ + S~22~ + S~33~) + 2(S~12~ + S~13~ + S~23~)]G_R = 15 / [4(S~11~ + S~22~ + S~33~ - S~12~ - S~13~ - S~23~) + 3(S~44~ + S~55~ + S~66~)][13] [12] - Hill Average:

K = (K_V + K_R) / 2,G = (G_V + G_R) / 2

- Voigt Bounds:

Young's Modulus and Poisson's Ratio:

E = 9KG / (3K + G),ν = (3K - 2G) / (2(3K + G))[13]Anisotropy Quantification:

- Universal Anisotropy Index (A^U):

A^U = (B_V/B_R) + 5(G_V/G_R) - 6[12]. A value of 0 indicates perfect isotropy; larger values indicate greater anisotropy. - Shear Anisotropic Factors: For crystals of different symmetries (e.g., tetragonal, hexagonal), specific factors (A~1~, A~2~, A~3~) can be calculated from combinations of elastic constants to describe anisotropy on different crystallographic planes [14].

- Universal Anisotropy Index (A^U):

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Toolkit

Table 1: Essential Software and Computational Resources for Elastic Constant Calculation.

| Item Name | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package (VASP) [9] [14] [13] | First-principles DFT calculation for energy and stress. | Projector Augmented-Wave (PAW) method; robust stress tensor calculation; high-performance computing (HPC) compatibility. |

| CASTEP [8] | First-principles DFT calculation for energy and stress. | Plane-wave basis set with pseudopotentials; integrated in Materials Studio; widely used for elastic property prediction. |

| Materials Project (MP) Database [9] [11] | Repository of pre-calculated material properties. | Provides access to calculated elastic tensors for over 13,000 inorganic compounds; REST API for data retrieval. |

| pymatgen [10] [11] | Python library for materials analysis. | Parses and analyzes elastic tensors from MP; performs symmetry analysis and property derivation (K, G, anisotropy). |

| ELATE [11] | Online elastic tensor analysis tool. | Interactive 3D visualization of elastic anisotropy; integrated with the MP database. |

| Cyclobuta[a]naphthalene | Cyclobuta[a]naphthalene | High-purity Cyclobuta[a]naphthalene for advanced organic synthesis and materials science research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 4-Ethylbenzenethiolate | 4-Ethylbenzenethiolate, MF:C8H9S-, MW:137.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Data Interpretation and Application

Quantitative Accuracy and Functional Selection

The accuracy of DFT-predicted elastic properties is highly dependent on the choice of the exchange-correlation functional. A recent benchmark study comparing functionals against reliable low-temperature experimental data provides the following guidance [8]:

Table 2: Accuracy of DFT Functionals for Predicting Elastic Properties (Based on [8]).

| Functional Type | Functional Name | Typical Error (vs. Experiment) | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meta-GGA | RSCAN | Most accurate overall | Highest accuracy requirements; systems where benchmark data exists. |

| GGA | PBESOL | Very accurate, close to RSCAN | General purpose; solid-state systems. |

| GGA | WC | Very accurate, close to RSCAN | General purpose; mechanical properties. |

| GGA | PBE | Less accurate than above | Common, but use with caution for quantitative elastic data. |

The typical spread between different experimental measurements for elastic constants can be as high as 10-20% in some cases (e.g., NiO) [9]. Well-converged DFT calculations with a recommended functional like RSCAN or PBESOL can achieve accuracy within 15% of experimental values, often with significantly less scatter than between conflicting experimental reports [9] [8].

Correlations with Macroscopic Material Behavior

The derived properties are not mere abstractions but serve as powerful predictors for material performance [9] [11]:

- Pugh's Ratio (K/G) for Ductility/Brittleness: The ratio of the bulk to shear modulus (K/G) is indicative of a material's ductile or brittle behavior. A high K/G ratio (> ~1.75) suggests greater ductility, as the material resists volumetric change more than shape change. A low ratio indicates inherent brittleness [9].

- Elastic Anisotropy and Microstructural Design: Strong elastic anisotropy implies that mechanical response (e.g., wave velocity, deformation) is direction-dependent. This is crucial for interpreting seismic data in geophysics and for designing textured polycrystalline materials where directional strength or compliance is desired [14] [12]. In materials like HfO~2~, anisotropy varies significantly between polymorphs, influencing their performance in applications like ferroelectric devices [14].

- Hardness and Thermal Properties: Empirical models often link the shear modulus to material hardness. Furthermore, the elastic constants are the primary input for calculating the Debye temperature and estimating the minimum thermal conductivity, which are vital for thermoelectric material development and thermal barrier coatings [13] [12].

The derivation of bulk modulus, shear modulus, and anisotropy from the fundamental elastic tensor is a cornerstone of analytical stress calculation and mechanical property prediction in inorganic materials research. The standardized DFT protocols, as implemented in high-throughput computational frameworks, provide a consistent and reliable source of this data, filling a critical gap where experimental measurements are scarce or challenging. By understanding and applying the methodologies outlined in this note—from the careful execution of strain-stress calculations to the insightful interpretation of derived properties like Pugh's ratio and anisotropy indices—researchers can effectively screen for materials with targeted mechanical responses, predict in-service material behavior, and drive the discovery of new materials for advanced technological applications. The integration of these computational tools with experimental validation creates a powerful feedback loop, accelerating the entire materials development cycle.

Stress calculation is a fundamental pillar in the research and development of inorganic materials, providing critical insights that bridge atomic-level structure to macroscopic mechanical performance. Accurate determination of stress and its relationship with strain enables researchers to predict material behavior under load, prevent catastrophic failure, and design materials with tailored properties such as enhanced hardness and mechanical stability. This application note details the core principles of stress-strain analysis, presents standardized protocols for experimental stress measurement, and explores the critical implications for a material's resistance to deformation and wear, providing a foundational framework for innovation in inorganic materials research.

In continuum mechanics, stress is a physical quantity that describes the internal forces that neighbouring particles of a continuous material exert on each other, with dimension of force per area (Pascals, Pa) [15]. For researchers developing new inorganic materials, from semiconductor components to structural ceramics, calculating stress is not merely an academic exercise—it is a critical determinant of practical viability. Stress analysis provides the quantitative foundation for predicting whether a material will withstand operational loads, resist permanent deformation, and maintain functional integrity over its intended lifespan. The mechanical stability of a device or component is directly governed by the stresses it experiences, while hardness, a material's resistance to localized surface deformation, is intrinsically linked to its underlying stress response [16]. This document establishes the essential principles and methodologies for accurate stress calculation, framing them within the context of analytical research aimed at advancing the frontiers of inorganic material performance.

Fundamental Principles of Stress and Strain

The relationship between stress and strain is foundational to understanding material behavior.

Stress-Strain Curve and Key Parameters

When a material is subjected to a steadily increasing axial force, the relationship between the applied stress (force per unit original area, σ = P/A₀) and the resulting strain (relative deformation, ε = ΔL/L₀) can be plotted as a stress-strain curve [17]. This curve reveals critical mechanical properties, with several points of interest [17]:

- Proportionality Limit (P): The maximum stress at which the stress-strain relationship remains linear.

- Yield Point (Y): The stress value above which the material begins to undergo plastic (permanent) deformation. The stress at this point is the yield strength (S_ty).

- Ultimate Strength (U): The maximum stress the material can withstand, also known as tensile strength (S_tu).

- Fracture Point (F): The stress and strain at which the material separates into pieces.

After yielding, many materials experience strain hardening, where the material becomes stronger through plastic deformation [17]. The strain hardening ratio (Stu / Sty), typically ranging from 1.2 to 1.4 for many metals, quantifies this phenomenon [17].

Table 1: Key Mechanical Properties Derived from Stress-Strain Analysis

| Property | Symbol | Definition | Significance in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Young's Modulus | E | Slope of the linear-elastic region of the stress-strain curve (σ = Eε) [17] | Quantifies stiffness; predicts elastic deformation under load [16] |

| Yield Strength | S_ty | Stress at which plastic deformation begins [17] | Determines the functional load limit for a component; critical for mechanical stability |

| Ultimate Tensile Strength | S_tu | Maximum stress a material can sustain [17] [16] | Defines the point of necking and maximum load-bearing capacity |

| Fracture Strength | Stress at total failure [16] | Important for analyzing brittle materials with little plastic deformation | |

| Hardness | Resistance to localized surface deformation (e.g., indentation) [16] | Correlates with strength and wear resistance; often used for non-destructive testing |

Distinguishing Strength, Stiffness, and Hardness

While related, these are distinct mechanical properties governed by stress-strain behavior [16]:

- Stiffness is an indicator of a material's tendency to return to its original form after loading, quantified by Young's Modulus (E). It is calculated as Force divided by displacement [16].

- Strength measures the stress that can be applied before permanent deformation (yield strength) or fracture (ultimate strength) occurs [16].

- Hardness is a measure of a material’s resistance to localized surface deformation, such as penetration or scratching [16]. For many metals, hardness and tensile strength are roughly proportional, making hardness tests a simple, inexpensive, and non-destructive way to estimate strength [16].

Experimental Protocols for Stress Analysis

Accurate stress calculation relies on robust, standardized experimental methods. The following protocols are essential for inorganic materials research.

Protocol 1: Uniaxial Tensile/Compression Testing for Fundamental Properties

This is the primary method for determining basic mechanical properties [17].

Objective: To generate an engineering stress-strain curve and determine key properties including Young's Modulus (E), yield strength (Sty), ultimate tensile strength (Stu), and ductility.

Materials and Equipment:

- Universal testing machine (e.g., Instron)

- Extensometer or strain gauge

- Specimen with standardized geometry (e.g., dog-bone shape)

Procedure:

- Specimen Preparation: Machine the material into a standardized test coupon with known original cross-sectional area (Aâ‚€) and gauge length (Lâ‚€).

- Mounting: Securely clamp the specimen into the testing machine's grips. Attach the extensometer to the gauge length to measure displacement accurately.

- Loading: Apply a controlled, steadily increasing axial force (tension or compression) to the specimen at a constant crosshead speed.

- Data Collection: Continuously record the applied force (P) and the corresponding change in length (ΔL) until the specimen fractures.

- Data Conversion and Analysis:

- Calculate engineering stress: σ = P / A₀ [17].

- Calculate engineering strain: ε = ΔL / L₀ [17].

- Plot the engineering stress versus engineering strain curve.

- Identify key parameters from the curve: E (slope of the initial linear region), Sty (using the 0.2% offset method if yield is not distinct), and Stu (maximum stress value) [17].

Protocol 2: Automated Stress Analysis via Dual-Wavelength Infrared Photoelasticity

This non-destructive, full-field technique is ideal for analyzing complex residual stresses in semiconductor and inorganic materials [4].

Objective: To perform automated, high-sensitivity, full-field mapping of internal stress in semiconductor structures (e.g., silicon wafers) without human intervention during phase-unwrapping.

Materials and Equipment:

- Dual-wavelength infrared photoelasticity setup (e.g., with 1200 nm and 1300 nm infrared light sources)

- Monochromatic infrared cameras

- Polarizing optical components (polarizer, quarter-wave plates, analyzer)

- Double-sided polished monocrystalline silicon wafer samples [4]

Procedure:

- Optical Setup: Align the dual-wavelength infrared light source and polarizing optics to create a circular polariscope arrangement.

- Calibration: Calibrate the stress-optical coefficients of the sample material at both wavelengths using a known stress state, such as a four-point bending experiment [4].

- Image Acquisition: For each wavelength (λ₠and λ₂), capture a series of phase-shifted photoelastic images (e.g., five-step phase-shifting) by adjusting the polarizer and analyzer axes [4].

- Automatic Phase Extraction:

- Calculate the change rate of intensity value, K, using the fifth-step images from both wavelengths [4].

- Use the K value to automatically localize reference points for phase-unwrapping, eliminating the need for manual seed-point selection [4].

- Implement an Adaptive Quality Map Guided Path (AQGPU) algorithm to perform high-accuracy, automatic unwrapping of both the isoclinic (principal stress direction) and isochromatic (principal stress difference) phase maps [4].

- Stress Calculation: Apply the stress-optical law to convert the unwrapped isochromatic phase values (δ) to the in-plane principal stress difference (σ₠- σ₂), and use the isoclinic values (θ) to determine the first principal stress direction [4].

Diagram 1: Automated infrared photoelasticity workflow for stress analysis in semiconductor materials.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful experimental stress analysis requires specialized materials and equipment.

Table 2: Essential Materials and Equipment for Stress Analysis Experiments

| Item | Function/Description | Research Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Universal Testing System | Applies controlled tensile, compressive, or cyclic loads to a specimen. | Fundamental characterization of yield strength and tensile strength via Protocol 3.1 [17]. |

| Double-Sided Polished Si Wafer | A standard semiconductor substrate with high surface flatness and specified crystallographic orientation (e.g., (111)) [4]. | Primary sample material for infrared photoelastic stress analysis (Protocol 3.2) in microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) and integrated circuit research [4]. |

| Dual-Wavelength Infrared Photoelastic Setup | Optical system with IR light sources (e.g., 1200nm, 1300nm), polarizers, and IR cameras for full-field, non-contact stress measurement [4]. | Automated internal stress mapping in semiconductor devices and inorganic flexible electronics to assess manufacturing quality and reliability [4]. |

| Strain Gauge / Extensometer | A sensor directly attached to the specimen to measure strain (deformation) under load. | Provides high-fidelity local strain measurements during uniaxial testing for accurate Young's Modulus calculation. |

| Hardness Tester (e.g., Rockwell) | Device that measures a material's resistance to penetration by a hard indenter [16]. | Rapid, non-destructive estimation of tensile strength and evaluation of wear resistance in material development and quality control [16]. |

| Pim-1 kinase inhibitor 3 | Pim-1 kinase inhibitor 3, MF:C20H25N3O2, MW:339.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2'-O-Methyl-5-Iodo-Uridine | 2'-O-Methyl-5-Iodo-Uridine, MF:C19H19FN2O7, MW:406.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Implications for Mechanical Stability and Hardness

The data derived from stress calculations directly informs critical aspects of material performance.

Ensuring Mechanical Stability

Mechanical stability requires that a material operates within its elastic limits under service conditions. Yield strength (S_ty) is the paramount property here, defining the maximum stress a material can endure without permanent deformation [17]. Designing components such that operational stresses remain below the yield strength ensures that the material will return to its original shape upon unloading, preventing cumulative damage and failure. Stress analysis also helps predict failure modes; for instance, a brittle material with little strain hardening may fracture suddenly shortly after yielding, whereas a ductile material will exhibit significant plastic deformation, providing a visual warning of impending failure [17].

Predicting and Enhancing Hardness

Hardness is a measure of a material’s resistance to localized plastic deformation, such as from an indenter, abrasion, or erosion [16]. It is intrinsically linked to the material's fundamental strength properties. For many metals, a strong, nearly proportional correlation exists between hardness and tensile strength, allowing researchers to use simple, inexpensive hardness tests as a reliable proxy for strength in quality control and initial material screening [16]. Processes like strain hardening, where plastic deformation increases a material's yield strength, also simultaneously enhance its hardness, demonstrating the direct connection between a material's bulk stress response and its surface resistance to penetration and wear [17] [16].

Diagram 2: The critical link between calculated stress data and key material performance attributes.

Computational and Analytical Methods for Stress Prediction

Density Functional Theory (DFT) has established itself as the foundational computational method for determining the elastic properties of materials from first principles. Elastic constants, which form a tensor quantifying a material's resistance to external forces, are fundamental for understanding mechanical behavior, thermodynamic stability, and anisotropic characteristics. The calculation of these properties through DFT provides a critical bridge between quantum mechanical principles and macroscopic material response, enabling researchers to screen and design materials in silico before synthesis. This application note details the methodologies, protocols, and computational tools for determining elastic constants within a broader framework of analytical stress calculation in inorganic materials research.

Theoretical Foundations

The elastic tensor C is a fourth-rank tensor that linearly relates the applied strain to the resulting stress in the Hooke's law regime. In its most general form, it possesses 21 independent components [10]. Within the framework of finite strain theory, the elastic constants are formally defined as derivatives of the free energy with respect to strain components. The second-order elastic constants (SOECs) are given by:

[C^{(2)}{\alpha{1}\alpha{2}} = \rho0 \left.\frac{\partial^2 A}{\partial\mu{\alpha{1}}\partial\mu{\alpha{2}}}\right|{\bm{0}} = \left.\frac{\partial P{\alpha{1}}(\vec{\mu})}{\partial\mu{\alpha{2}}}\right|{\bm{0}} ]

where ( \rho0 ) is the mass density in the reference state, ( A ) is the Helmholtz free energy per unit mass, ( \mu{\alphai} ) are components of the strain tensor, and ( P{\alpha_{1}} ) is a component of the stress tensor [18]. Higher-order elastic constants (third-order, TOECs; fourth-order, FOECs; etc.) capture nonlinear behavior under large deformations and are crucial for understanding anharmonic properties, thermal expansion, and mechanical instabilities [18].

DFT provides the electronic structure framework to compute the energy and stresses for a given atomic configuration. The stress tensor is directly accessible from modern DFT codes through the derivative of the energy with respect to the strain components, forming the basis for elastic constant calculations.

Computational Methodologies and Protocols

Standard Strain-Stress Approach

The most prevalent method for calculating SOECs involves applying a set of finite strain deformations to a fully relaxed structure and computing the resulting stress tensors [10]. The following protocol outlines this standard approach:

Table 1: Key Strain States for Elastic Tensor Calculation [10]

| Strain State Index | Strain Tensor (Voigt Notation) | Deformed Lattice Vectors | Independent Components Probed |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ( (\delta, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0) ) | ( ((1+\delta)a1, a2, a_3) ) | ( C{11}, C{12}, C_{13} ) |

| 2 | ( (0, \delta, 0, 0, 0, 0) ) | ( (a1, (1+\delta)a2, a_3) ) | ( C{12}, C{22}, C_{23} ) |

| 3 | ( (0, 0, \delta, 0, 0, 0) ) | ( (a1, a2, (1+\delta)a_3) ) | ( C{13}, C{23}, C_{33} ) |

| 4 | ( (0, 0, 0, 2\delta, 0, 0) ) | ( (a1, a2+\delta a3, a3+\delta a_2) ) | ( C{44}, C{14}, C{24}, C{34} ) |

| 5 | ( (0, 0, 0, 0, 2\delta, 0) ) | ( (a1+\delta a3, a2, a3+\delta a_1) ) | ( C{55}, C{15}, C{25}, C{35} ) |

| 6 | ( (0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 2\delta) ) | ( (a1+\delta a2, a2+\delta a1, a_3) ) | ( C{66}, C{16}, C{26}, C{36} ) |

- Initial Structural Relaxation: Perform a full relaxation (both ionic positions and cell vectors) of the conventional unit cell until the residual forces and stresses are below a stringent threshold (e.g., 1 meV/Ã… for forces, 0.1 GPa for stress). Using conventional rather than primitive cells often improves convergence due to higher symmetry [10].

- Strain Application: For each of the 6 independent strain states in Table 1, apply 4 different magnitudes of strain (e.g., ( \delta \in {-0.01, -0.005, +0.005, +0.01} )), generating 24 deformed structures [10].

- Stress Calculation: For each deformed structure, perform a DFT calculation with fixed lattice vectors but relaxed ionic positions. The output includes the computed stress tensor for each strain.

- Tensor Fitting: Fit the full 6x6 elastic tensor ( C_{ij} ) using a linear least-squares regression of the stress-strain data, often employing the Moore-Penrose pseudoinverse method [19].

- Validation and Standardization: Check that the resulting matrix is positive definite, ensuring mechanical stability. The tensor can be rotated to a standard IEEE coordinate system for consistent reporting across different materials [10].

Advanced Protocol for Higher-Order Elastic Constants

Calculating elastic constants beyond the second order requires a more sophisticated approach to capture nonlinear stress-strain response.

- Extended Strain Series: Apply a wider range of strain magnitudes (e.g., from -2% to +2% in more steps) to probe the nonlinear regime.

- Stress-Strain Fitting: For each strain mode, fit the stress as a polynomial function of the strain. The quadratic and higher-order coefficients are related to the TOECs and FOECs.

- Recursive Numerical Differentiation: Employ a divided-differences algorithm, homologous to polynomial interpolation, to compute higher-order derivatives of energy or stress with respect to strain recursively. This method is generalizable to any material symmetry and order of elastic constant [18].

- Validation: Validate the computed higher-order constants by using them in a continuum constitutive law to predict the stress response to large deformations (e.g., uniaxial, shear) and compare these predictions against direct DFT calculations [18].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated process for calculating both second-order and higher-order elastic constants.

Essential Computational Tools and "Reagents"

Successful DFT-based elasticity calculations require careful selection of software, functionals, and computational parameters. The following table acts as a toolkit for researchers.

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Key "Reagents" for DFT Elasticity Calculations

| Tool Category | Specific Item/Software | Function and Role | Best Practice / Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFT Codes | Quantum ESPRESSO [19], VASP | Performs core electronic structure calculations, structural relaxation, and stress computation. | Choose a code with robust stress tensor implementation. |

| Strain Generation & Analysis | pymatgen [20], AEL-ASElibraries | Automates the application of strain tensors and parses calculated stress data. | Essential for high-throughput workflows. |

| Exchange-Correlation Functional | PBE (GGA) [21], LDA, SCAN | Approximates the quantum mechanical exchange-correlation energy. | PBE is a common standard; hybrid functionals improve accuracy for insulators at greater cost. |

| Van der Waals Correction | DFT-D3, vdW-DF2 | Accounts for dispersion forces critical in layered or molecular crystals. | Crucial for organic-inorganic interfaces [21]. |

| Basis Set | Plane-waves | Expands the electronic wavefunctions. | Ensure a high kinetic energy cutoff for stress convergence. |

| Pseudopotentials/PAWs | PseudoDojo, GBRV, VASP PAWs | Represents core electrons and ionic potentials. | Use consistent and high-quality sets for accurate stresses. |

| Specialized Tools | Sim2L (nanoHUB) [19], hoecs program [18] | Provides integrated workflows for elastic constants or higher-order constants. | Reduces implementation overhead for standard protocols. |

Data Output and Derived Properties

The primary output of the calculation is the 6x6 symmetric elastic constant matrix. From this tensor, crucial isotropic aggregate properties for polycrystalline materials can be derived:

Table 3: Derived Elastic Properties from the Elastic Tensor

| Property | Symbol | Definition/Calculation | Physical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk Modulus (Voigt) | ( K_V ) | ( (C{11}+C{22}+C{33} + 2(C{12}+C{13}+C{23}))/9 ) | Upper bound for resistance to uniform compression. |

| Shear Modulus (Voigt) | ( G_V ) | ( (C{11}+C{22}+C{33} - C{12}-C{13}-C{23} + 3(C{44}+C{55}+C_{66}))/15 ) | Upper bound for resistance to shear deformation. |

| Bulk Modulus (Reuss) | ( K_R ) | ( 1/(S{11}+S{22}+S{33} + 2(S{12}+S{13}+S{23})) ) | Lower bound for resistance to uniform compression. |

| Shear Modulus (Reuss) | ( G_R ) | ( 15/(4(S{11}+S{22}+S{33}) -4(S{12}+S{13}+S{23}) + 3(S{44}+S{55}+S_{66})) ) | Lower bound for resistance to shear deformation. |

| Bulk Modulus (Hill) | ( K_H ) | ( (KV + KR)/2 ) | Arithmetic mean of Voigt and Reuss bounds. |

| Shear Modulus (Hill) | ( G_H ) | ( (GV + GR)/2 ) | Arithmetic mean of Voigt and Reuss bounds. |

| Young's Modulus | ( E ) | ( 9KHGH/(3KH + GH) ) | Stiffness in uniaxial tension. |

| Poisson's Ratio | ( \nu ) | ( (3KH - 2GH)/(2(3KH + GH)) ) | Lateral strain response to axial strain. |

Emerging Frontiers and Best Practices

The field is rapidly advancing with the integration of new computational strategies. Machine learning, particularly Crystal Graph Convolutional Neural Networks (CGCNNs), has demonstrated high accuracy in predicting shear and bulk moduli ((R^2$ close to 1), enabling the screening of vast material spaces [22]. Furthermore, Large Language Models (LLMs) fine-tuned on materials data, such as ElaTBot-DFT, show promise in directly predicting elastic tensors, reducing errors by over 33% compared to some prior models [20].

For reliable results, especially when modeling complex systems like hybrid inorganic-organic interfaces, best practices must be followed [21]:

- System Setup: Use conventional cells for higher symmetry and more robust Brillouin zone sampling.

- Functional Selection: Test the sensitivity of results to the exchange-correlation functional and van der Waals corrections.

- Convergence: Ensure absolute convergence of the self-consistent field cycle and geometry optimization with respect to k-points and plane-wave cutoff to prevent erroneous forces and stresses.

- Validation: Always check the mechanical stability criteria (e.g., positive eigenvalues of the elastic matrix) and validate predictions against known experimental or computational benchmarks where available.

The elastic constant tensor is a fundamental physical property that provides a complete description of a material's response to external stresses within the elastic limit. This tensor offers profound insight into the nature of intrinsic bonding within materials and serves as a critical indicator for predicting numerous mechanical and thermal properties [20]. In inorganic crystalline compounds, the elastic tensor correlates with properties including mechanical stability, thermal conductivity, acoustic behavior, hardness, and fracture toughness [8] [9]. Despite its fundamental importance, complete elastic tensor data remains scarce for the vast majority of known inorganic compounds due to significant experimental and computational challenges [9].

Traditional experimental methods for determining elastic constants—including Brillouin spectroscopy, resonant ultrasound spectroscopy, inelastic X-ray scattering, and impulse-stimulated light scattering—are often hindered by requirements for specific sample conditions, lengthy procedures, and specialized equipment [8]. These limitations have created a critical bottleneck in materials discovery and design workflows. High-throughput computational approaches have emerged as a transformative solution to this challenge, enabling the systematic charting of complete elastic properties across broad chemical spaces [9].

Computational Frameworks for Elastic Property Determination

Density Functional Theory (DFT) Foundations

Density functional theory calculations form the cornerstone of modern computational materials science for predicting elastic properties. DFT methods solve the quantum mechanical many-body problem to determine electronic structure and ground-state energy, providing a first-principles basis for property prediction without empirical parameters [8]. The accuracy of DFT-predicted elastic properties varies significantly based on the choice of exchange-correlation functional. Comparative studies have demonstrated that the meta-GGA functional RSCAN typically delivers the best overall performance, closely matched by the GGA functionals Wu-Chen and PBESOL [8].

The computational workflow involves applying a series of controlled deformations to a fully relaxed crystal structure and calculating the resulting stress tensors. Through systematic variation of strain components, the complete elastic constant tensor can be reconstructed via linear regression of the stress-strain response [9]. For materials containing strongly correlated electrons, such as certain transition metal oxides, the DFT+U method incorporating Hubbard parameters improves accuracy by accounting for on-site Coulomb interactions [9].

Machine Learning and Large Language Model Innovations

Recent advances in artificial intelligence have introduced novel paradigms for elastic property prediction. Specialized large language models (LLMs) such as ElaTBot demonstrate remarkable capability in predicting full elastic constant tensors directly from text-based representations of crystal structures [20]. These models leverage prompt engineering and knowledge fusion techniques to achieve multitask functionality, predicting not only elastic tensors but also generating new materials with targeted properties.

ElaTBot-DFT, a variant specialized for 0 K elastic constant prediction, reduces errors by 33.1% compared to existing domain-specific materials science LLMs when trained on identical datasets [20]. The integration of retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) further enhances predictive capabilities by enabling the model to access and incorporate information from external databases and tools without retraining [20]. This natural language-based approach significantly lowers the barrier to entry for researchers lacking extensive programming backgrounds, making advanced property prediction more accessible across the materials science community.

Table 1: Comparison of Computational Methods for Elastic Property Prediction

| Method | Key Features | Accuracy | Computational Cost | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFT (PBE Functional) | First-principles, widely adopted | Typically within 15% of experimental values [9] | High for large systems | Accuracy varies with functional choice |

| DFT (RSCAN Functional) | Meta-GGA approach | Highest overall accuracy [8] | Very high | Limited availability in codes |

| Machine-Learned Potentials | Trained on DFT data | Qualitatively and sometimes quantitatively accurate [8] | Moderate | Transferability concerns |

| Large Language Models (ElaTBot) | Text-based structural input, multi-task capability | 33.1% error reduction vs. domain-specific LLMs [20] | Low after training | Limited to training data scope |

High-Throughput Implementation Protocols

Workflow Architecture and Data Management

The high-throughput computational framework for elastic property determination follows a systematic workflow that integrates structure selection, property calculation, validation, and database storage. The Materials Project database implementation exemplifies this approach, employing automated pipelines that process thousands of compounds through standardized protocols [9]. The workflow begins with structure selection criteria focusing on metallic/small-band-gap compounds and binary oxides/semiconductors, with constraints including energy above convex hull and bandgap thresholds to ensure thermodynamic stability relevance [9].

Implementation requires robust data management systems capable of handling the substantial computational output. The JSON-based data structure developed for the Materials Project elasticity database efficiently stores the full elastic tensor, compliance tensor, and derived properties including bulk modulus (Voigt, Reuss, and VRH averages), shear modulus (Voigt, Reuss, and VRH averages), and universal elastic anisotropy [23]. This standardized format enables interoperability and facilitates data sharing across research communities.

Stress-Strain Methodology Protocol

The core computational protocol for elastic constant determination employs a stress-strain approach grounded in continuum mechanics principles. The methodology follows these specific steps:

Structure Relaxation: Fully optimize the crystal structure using DFT to minimize forces and stresses below predetermined thresholds (typically 0.01 eV/Ã… for forces and 0.1 GPa for stresses) [9].

Strain Application: Apply six independent components of the Green-Lagrange strain tensor to the relaxed structure with varying magnitudes (typically ranging from -1% to +1% deformation) [9]. Each strain component is applied independently while maintaining all other components at zero.

Stress Calculation: For each deformed structure, perform a DFT calculation with ionic position relaxation to determine the full 3×3 stress tensor. The plane-wave energy cutoff and k-point density must maintain consistency with the relaxation parameters to ensure numerical consistency [9].

Linear Regression: For each applied strain type, perform a linear regression of the calculated stresses against the applied strains to determine one row/column of the elastic constant matrix. The complete 6×6 elastic matrix is reconstructed by repeating this process for all six independent strain components [9].

Tensor Validation: Apply crystal symmetry operations to verify that the calculated elastic tensor conforms to the expected symmetry of the crystal structure. The IEEE standard is adopted for all reported tensors to maintain consistency [9].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Elasticity

| Research Tool | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| DFT Codes | Electronic structure calculation | VASP, CASTEP, ElasTool, VELAS [8] |

| Pseudopotentials | Represent core electrons | Ultrasoft pseudopotentials, PAW potentials [9] |

| Exchange-Correlation Functionals | Approximate quantum interactions | PBE, PBESOL, RSCAN, Wu-Chen [8] |

| Structure Analysis Tools | Extract structural descriptors | Pymatgen, robocrystallographer [20] |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | Property prediction and materials generation | Random Forest, Gradient Boosted Trees, ElaTBot [20] [24] |

Validation and Accuracy Assessment Protocols

Experimental-Computational Correlation

Establishing the accuracy of computed elastic properties requires rigorous validation against reliable experimental data. Comparative studies demonstrate that DFT-calculated elastic constants typically fall within 15% of experimental values, which in many cases represents a smaller variation than that observed between different experimental measurements [9]. For example, significant discrepancies (exceeding 20%) sometimes occur between bulk modulus values derived from pressure-volume equations of state versus those determined from elastic coefficients [8].

The validation protocol involves several critical steps: compilation of reliable experimental data with preference for low-temperature measurements that better correspond to 0 K computational results; statistical analysis using relative root mean square deviations (RRMS), absolute root mean square deviations (ARMS), average deviation (AD), and average absolute deviation (AAD); and systematic investigation of error sources including exchange-correlation functional choice, pseudopotential selection, and numerical convergence parameters [8].

Data Quality Metrics and Convergence Testing

Implementation of comprehensive quality control measures ensures the reliability of high-throughput elasticity data. Convergence testing protocols establish appropriate computational parameters for different material classes:

- Plane-wave cutoff energy: Determined through convergence tests for relevant chemical elements, typically ranging from 330 to 800 eV [8]

- k-point sampling: Uniform k-point density of approximately 7,000 per reciprocal atom for metallic systems and 1,000 per reciprocal atom for oxides [9]

- Numerical thresholds: Elastic constants converged to within 5% for 95% of considered systems [9]

Anomaly detection algorithms identify potential calculation failures or outliers, triggering automatic recalculation with enhanced parameters when results fall outside expected physical ranges (e.g., negative elastic constants violating mechanical stability criteria) [9].

Applications in Materials Discovery and Design

Targeted Materials Screening

The availability of comprehensive elastic property databases enables efficient screening for materials with targeted mechanical behavior. Applications include identification of compounds with specific hardness characteristics for coating applications, materials with tailored thermal expansion properties for precision instrumentation, and systems exhibiting exceptional strength-to-weight ratios for aerospace applications [9] [24].

The Pugh ratio (bulk modulus to shear modulus ratio) serves as a valuable descriptor for ductile versus brittle behavior, facilitating the discovery of ductile intermetallic compounds [9]. Similarly, elastic anisotropy measurements enable prediction of materials with direction-dependent mechanical properties valuable for specialized applications including thermal barrier coatings and wear-resistant surfaces [9].

Multi-Scale Modeling Integration

Elastic constant tensors provide essential input parameters for multi-scale modeling frameworks that bridge quantum mechanical calculations with continuum-scale simulations [8]. The complete elastic tensor for single crystals serves as fundamental input for homogenization procedures that predict the mechanical response of polycrystalline materials and composite systems [8].

In emerging applications, elastic properties inform the prediction of complex phenomena such as anisotropic negative thermal expansion in framework materials [24]. The connection between elastic anisotropy and thermal expansion behavior enables computational screening of materials with controlled thermal expansion characteristics, valuable for applications requiring exceptional dimensional stability across temperature ranges [24].

High-throughput workflows for charting complete elastic properties represent a transformative advancement in materials informatics. The integration of density functional theory, machine learning, and automated data management systems has enabled the creation of extensive databases that accelerate materials discovery and design. These computational approaches successfully address the critical data scarcity problem that has long impeded systematic exploration of structure-property relationships in mechanical behavior.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on several key areas: enhanced accuracy through advanced exchange-correlation functionals and quantum Monte Carlo methods; expanded scope encompassing temperature-dependent elastic properties and finite-strain behavior; and tighter integration with experimental characterization techniques through inverse design paradigms. As these computational protocols continue to mature, they will increasingly serve as the foundation for rational materials design across diverse technological domains including energy storage, aerospace engineering, and electronic devices.

Machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) represent a transformative advancement in computational materials science and chemistry, effectively bridging the critical gap between highly accurate but computationally expensive quantum mechanical (QM) methods and efficient but limited empirical molecular mechanics (MM) simulations [25]. By leveraging machine learning to approximate potential energy surfaces (PES) from quantum mechanical data, MLIPs achieve near-first-principles accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost, enabling previously inaccessible atomistic simulations of complex systems [26] [25]. This capability is particularly valuable for investigating inorganic materials, where understanding stress distributions, phase stability, and mechanical properties under various thermodynamic conditions is essential for materials design and discovery.

The fundamental operation of MLIPs involves mapping atomic configurations—defined by atomic positions, element types, and periodic lattice vectors—to a total potential energy, from which forces and stresses can be derived analytically [26]. This approach has dramatically expanded the scope of atomistic simulations, allowing researchers to access relevant length and time scales for studying industrially important phenomena such as catalytic reactions, defect migration, and phase transformations in inorganic material systems [27] [25]. As the field progresses, MLIPs are evolving from specialized tools for specific material systems toward universal potentials (U-MLIPs) capable of describing diverse chemical spaces across the periodic table, further enhancing their utility as foundational tools for accelerated atomistic calculations [26].

Foundational Concepts and Methodological Frameworks

Methodological Spectrum of Atomistic Simulations

The landscape of atomistic simulation methods spans a wide spectrum of physical approximation and computational efficiency, with MLIPs occupying a crucial middle ground. Table 1 summarizes the key characteristics of the main methodological approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of Atomistic Simulation Methods

| Method | Physical Approximation | Computational Efficiency | Transferability | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Mechanics (QM) [25] | First-principles, no empirical parameters | Low (e.g., O(N³) for DFT) | High (in principle) | Electronic properties, reaction mechanisms, spectroscopic properties |

| Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) [26] [25] | Learned from QM data | Medium to High | Medium to High (system-dependent) | Large-scale MD, complex systems, property prediction |

| Molecular Mechanics (MM) [25] | High (empirical force fields) | High | Low (system-specific) | Biomolecular simulations, conformational sampling |

QM methods, while physically rigorous and highly accurate, suffer from steep computational scaling that limits their application to small systems (typically a few hundred atoms) and short timescales (picoseconds) [25]. Conversely, traditional MM force fields employ simplified analytical functions with parameters often derived from experimental data, making them computationally efficient but limited in transferability and unable to describe bond formation and breaking [25]. MLIPs effectively bridge this divide by learning the complex relationship between atomic configurations and potential energies from QM data, enabling the simulation of systems containing tens of thousands of atoms over nanosecond to microsecond timescales while maintaining near-QM accuracy [26].

Key Architectural Paradigms in MLIP Development

MLIP architectures can be broadly categorized into explicit featurization approaches and graph neural network (GNN) based methods, each with distinct advantages and implementation strategies:

Explicit Featurization Approaches: Early MLIPs like the Behler-Parrinello neural network (BPNN) and Gaussian Approximation Potential (GAP) rely on manually crafted descriptors to represent atomic environments, such as atom-centered symmetry functions or smooth overlap of atomic positions (SOAP) [28] [26]. These descriptors are designed to incorporate fundamental physical symmetries, including invariance to translation, rotation, and permutation of like atoms. While effective, these approaches may lack systematic improvability and require careful selection of descriptor parameters.

Graph Neural Network Frameworks: Modern MLIPs increasingly adopt GNN architectures that implicitly learn representations from atomic structures represented as graphs, where atoms constitute nodes and interatomic connections within a cutoff radius form edges [28] [26]. Models such as NequIP, MACE, Allegro, and the recently introduced Cartesian Atomic Moment Potential (CAMP) perform message passing between atoms to iteratively refine atomic representations, effectively capturing higher-body-order interactions critical for describing complex materials [28]. The CAMP approach specifically constructs atomic moment tensors entirely in Cartesian space, bypassing the computational complexity of spherical harmonics while maintaining a complete description of local atomic environments [28].

Table 2: Prominent MLIP Architectures and Their Key Features

| MLIP Model | Architecture Type | Key Features | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAMP [28] | GNN (Cartesian) | Cartesian moment tensors, tensor products for body-order, systematic improvability | Periodic crystals, molecules, 2D materials |

| MACE [28] | GNN (Spherical) | Higher-body-order messages, equivariant representations | Materials with complex bonding |

| Allegro [26] | GNN (Equivariant) | Separable architecture, equivariance without spherical harmonics | Diverse molecular and materials systems |

| ANI (ANAKIN-ME) [26] | Neural Network | Transfer learning, optimized for organic molecules | Drug discovery, molecular energy prediction |

| ACE [28] [26] | Explicit Featurization | Atomic cluster expansion, complete body-ordered basis | High-precision materials properties |

Practical Protocols for MLIP Implementation

Workflow for Developing and Applying MLIPs

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for developing and applying machine-learned interatomic potentials in materials research, with particular emphasis on stress calculation in inorganic systems:

Diagram 1: Comprehensive workflow for MLIP development and application, highlighting key stages from data generation to property calculation, with specific emphasis on stress analysis in inorganic materials.

Data Generation and Training Protocol

Training Dataset Construction

- Reference Calculations: Perform density functional theory (DFT) calculations on diverse atomic configurations representative of the system's phase space, including bulk structures, surfaces, defects, and thermal perturbations [26]. These calculations should provide energies, forces, and stress tensors for training.

- Configuration Sampling: Employ enhanced sampling techniques such as molecular dynamics runs at various temperatures, random atomic displacements, or targeted sampling of transition states to ensure comprehensive coverage of the potential energy landscape [26].

- Active Learning Cycle: Implement an iterative active learning approach where the initially trained MLIP is used to run molecular dynamics simulations, with new configurations that exhibit high uncertainty (as determined by the model's built-in uncertainty quantification) selected for additional DFT calculations and added to the training set [26]. This process continues until the MLIP demonstrates robust performance across all relevant configurations.

Model Training Procedure

- Architecture Selection: Choose an appropriate MLIP architecture based on system requirements. For inorganic materials with complex bonding, equivariant GNN models like CAMP, MACE, or Allegro are generally recommended due to their systematic improvability and high accuracy [28] [26].

- Parameter Optimization: Utilize the model's native training framework (e.g., MACE, NequIP, or Allegro implementations) with appropriate hyperparameter tuning. Critical parameters include cutoff radius (typically 5-6 Ã…), number of message passing layers (3-6), and feature dimensions [26].

- Validation Strategy: Implement a rigorous train-test split (typically 80-20 or 90-10) with separate validation configurations not used during training. Monitor both energy and force errors during training to prevent overfitting [26].

Protocol for Analytical Stress Calculations in Inorganic Materials

The calculation of analytical stresses is crucial for studying mechanical properties, phase stability, and pressure-dependent phenomena in inorganic materials. The following protocol ensures accurate stress computation:

Stress Tensor Formulation: For a trained MLIP, the analytical stress tensor is computed as the derivative of the total energy with respect to the deformation gradient. In periodic systems, the stress tensor components are given by:

[ \sigma{\alpha\beta} = -\frac{1}{V}\sumi \frac{\partial E}{\partial \varepsilon_{\alpha\beta}} ]

where ( V ) is the cell volume, ( E ) is the total potential energy, and ( \varepsilon_{\alpha\beta} ) are strain tensor components [28].