AI vs. Human Experts in Materials Discovery: A New Paradigm for Scientific Breakthroughs

This article explores the evolving synergy between artificial intelligence and human expertise in accelerating materials discovery, with a focus on applications in biomedical and clinical research.

AI vs. Human Experts in Materials Discovery: A New Paradigm for Scientific Breakthroughs

Abstract

This article explores the evolving synergy between artificial intelligence and human expertise in accelerating materials discovery, with a focus on applications in biomedical and clinical research. We examine foundational concepts where AI 'bottles' human intuition, methodological advances in autonomous experimentation, and strategies for overcoming computational and reproducibility challenges. Through comparative analysis of real-world platforms and case studies, we provide a framework for researchers to integrate AI tools effectively, balancing unprecedented speed with the irreplaceable value of scientific creativity and oversight to fast-track the development of novel therapeutics and materials.

The New Frontier: How AI is Augmenting Human Intelligence in Materials Science

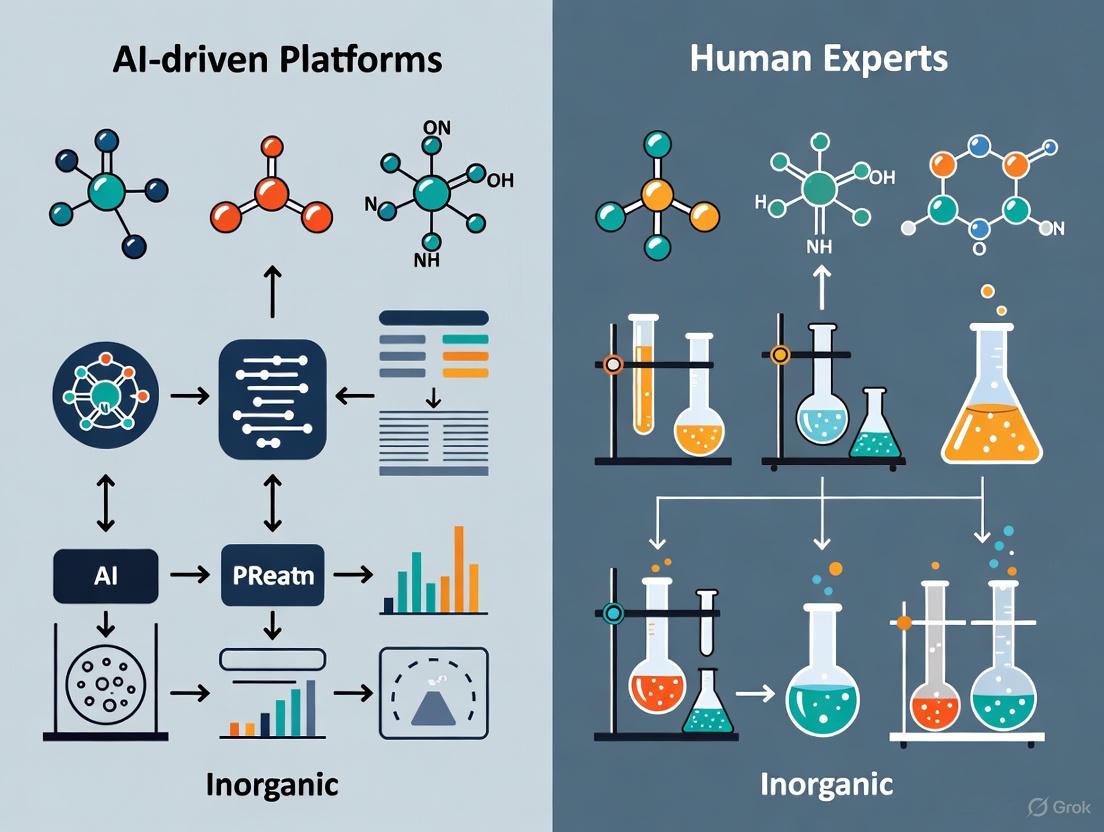

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into scientific discovery is creating a new paradigm for research. Frameworks like Materials Expert-Artificial Intelligence (ME-AI) are being developed not to replace human scientists, but to capture and quantify their expert intuition, creating collaborative systems that accelerate discovery. This guide compares the performance of such AI-driven platforms against human experts in materials discovery, focusing on their respective strengths and the experimental data that benchmark their capabilities.

The Rise of AI Collaboration in Scientific Discovery

Traditional materials discovery has often been a slow process, relying on a combination of theoretical models, trial-and-error experimentation, and the invaluable, yet hard-to-define, intuition of experienced researchers [1]. This intuition is built from years of hands-on work and deep domain knowledge. The challenge has been to translate this qualitative "gut feeling" into a quantitative, scalable framework [2].

AI-driven platforms are now being designed to meet this challenge. Their primary goal is to bottle the insights latent in the expert growers' human intellect [3]. This is achieved by having the AI learn from data that has been carefully curated and labeled by human experts, allowing the machine to uncover the underlying descriptors and rules that the expert may use subconsciously [2]. This approach represents a significant shift from purely data-driven AI to a human-in-the-loop model where domain expertise guides and informs the computational process.

Comparative Analysis: AI-Driven Platforms vs. Human Experts

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of AI-driven platforms and human experts, highlighting their complementary roles in the modern research workflow.

| Feature | AI-Driven Platforms (e.g., ME-AI, CRESt) | Human Experts |

|---|---|---|

| Core Strength | Rapid, systematic exploration of high-dimensional parameter spaces; quantitative descriptor identification [3] [4]. | Creative, divergent thinking; intuitive leaps based on deep domain knowledge and experience [4]. |

| Knowledge Processing | Learns from expert-curated data to reproduce and extend human insight; can articulate its reasoning process [3] [2]. | Integrates knowledge from diverse sources (literature, experiments, collegial input) and personal intuition, which can be difficult to articulate [2] [5]. |

| Exploration Scope | Efficiently screens thousands of possibilities based on learned criteria; excels at "in-the-box" search within a defined space [4] [5]. | Capable of "outside-the-box" thinking; can make unexpected connections beyond the immediate data, leading to novel pathways [4]. |

| Scalability & Speed | Highly scalable and fast; can run high-throughput computations and robotic experiments 24/7 [5]. | Limited by human speed and endurance; the discovery process can be painstakingly long [1]. |

| Typical Role | A powerful assistant that augments human capability; handles data-heavy lifting and optimization [5]. | The domain expert who defines the problem, curates data, and provides the foundational intuition for the AI to learn from [3]. |

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

The following table presents experimental data from studies that directly or indirectly compare the output of AI systems and human researchers in discovery-oriented tasks.

| Experiment Task | AI Platform / Method | Human Expert / Control | Key Performance Results | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lubricant Molecule Discovery | State-of-the-art AI system | Teams of human participants | AI Average Performance: Significantly better molecules on average.Human Peak Performance: The single best molecule was found by a human participant. | [4] |

| Fuel Cell Catalyst Discovery | CRESt Platform (Multimodal AI) | Traditional research methods | Discovery Speed: Explored 900+ chemistries, conducted 3,500 tests in 3 months.Performance: Achieved a 9.3-fold improvement in power density per dollar over a pure palladium catalyst. | [5] |

| Identification of Topological Materials | ME-AI (Gaussian Process Model) | Expert-derived "tolerance factor" rule | Validation: ME-AI successfully reproduced the expert's known structural descriptor.Expansion: Identified new, emergent descriptors (e.g., hypervalency) and demonstrated transferability to different material families. | [3] [2] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To understand the benchmarks above, it is essential to examine the methodologies behind the key experiments.

The ME-AI Workflow for Quantum Materials Discovery

The ME-AI framework was developed specifically to translate a materials expert's intuition into quantitative, actionable descriptors [3] [2]. Its application to identifying topological semimetals (TSMs) in square-net compounds follows a rigorous protocol:

- Expert-Led Data Curation: A human expert (e.g., a materials chemist) curates a dataset of 879 square-net compounds from a structural database. The expert selects 12 primary features (PFs)—including atomistic properties like electronegativity and valence electron count, and structural distances—based on chemical intuition and domain knowledge [3].

- Expert Labeling: Each compound in the dataset is labeled as a TSM or a trivial material. This is a critical step where expert insight is transferred to the dataset. Labeling is done through:

- Direct experimental or computational band structure analysis (56% of the database).

- Chemical logic and analogy for alloys and related compounds (44% of the database) [3].

- Model Training: A Dirichlet-based Gaussian process model with a chemistry-aware kernel is trained on this curated and labeled dataset. The model's task is not just classification, but to discover the effective descriptors that predict the TSM property from the PFs [3].

- Descriptor Extraction and Validation: The trained model is analyzed to reveal the combinations of primary features that serve as the most potent descriptors. The model successfully recovered the "tolerance factor," a known expert-derived rule, and identified new descriptors like hypervalency. The model's generalizability was tested and confirmed by accurately predicting topological insulators in a different crystal structure family (rocksalt) [3].

The CRESt Platform for High-Throughput Materials Discovery

MIT's CRESt (Copilot for Real-world Experimental Scientists) platform represents a broader, multimodal approach to AI-driven discovery, integrating diverse data sources and robotic experimentation [5].

- Multimodal Knowledge Integration: The system begins by ingesting information from diverse sources, including scientific literature, existing databases, chemical compositions, and microstructural images. This creates a rich "knowledge embedding space" [5].

- Search Space Definition and Active Learning: Principal component analysis is performed on the knowledge space to define a reduced, efficient search space. Bayesian optimization is then used within this space to design the next best experiment [5].

- Robotic Execution and Analysis: CRESt's robotic systems—including liquid-handling robots and automated electrochemical workstations—synthesize and test the proposed material recipes. Characterization equipment, like electron microscopes, provides immediate feedback on the results [5].

- Iterative Loop with Human Feedback: The results from the experiments, along with human researcher observations, are fed back into the large language model to update the knowledge base and refine the search space for the next iteration. The system can use computer vision to monitor experiments and suggest corrections for reproducibility issues [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

The following table details key resources and their functions that are central to conducting research in this field, from computational tools to physical laboratory components.

| Research Reagent / Solution | Function in AI-Driven Materials Discovery |

|---|---|

| Curated Experimental Datasets | The foundational resource on which AI models like ME-AI are trained. Requires expert labeling to embed human intuition into quantitative data [3] [2]. |

| Gaussian Process Models | A class of ML models ideal for working with smaller datasets; they are interpretable and can provide uncertainty estimates, making them well-suited for scientific discovery tasks [3]. |

| Liquid-Handling Robots | Automated laboratory hardware that enables high-throughput synthesis of material recipes proposed by the AI, drastically accelerating the experimental cycle [5]. |

| Automated Electrochemical Workstations | Robotic testing equipment that rapidly characterizes the functional performance (e.g., catalytic activity) of newly synthesized materials, providing critical feedback data for the AI [5]. |

| Multimodal Knowledge Bases | Integrated databases that combine scientific literature, structural data, and experimental results, allowing AI systems like CRESt to make informed predictions based on a wide context [5]. |

| Dirichlet-based Kernels | A type of function used in Gaussian process models that can be designed to be "chemistry-aware," allowing the model to respect known chemical relationships or periodic trends while learning [3]. |

| 3,6-Diamino-9(10H)-acridone | 3,6-Diamino-9(10H)-acridone, CAS:42832-87-1, MF:C13H11N3O, MW:225.25 g/mol |

| (+)-5-trans Cloprostenol | D-Cloprostenol|High-Purity Research Compound |

The evolving narrative in materials discovery is not a competition but a collaboration. Frameworks like ME-AI and CRESt demonstrate that the most powerful approach combines the quantitative, scalable pattern recognition of AI with the qualitative, creative intuition of the human expert [3] [4] [5]. AI excels at efficiently searching vast, complex spaces defined by expert-curated data, while humans provide the foundational insights, define the problems, and make the creative leaps that can lead to true breakthroughs. The future of accelerated discovery lies in this synergistic partnership, where AI serves as a powerful copilot, bottling intuition to guide the scientific journey.

For decades, scientific advancement in materials science and drug discovery has relied heavily on serendipitous discovery and laborious trial-and-error methodologies. Human experts, drawing upon deep intuition honed through years of experience, have traditionally navigated vast chemical spaces with incremental progress. Today, a profound shift is underway: artificial intelligence (AI) is transforming this landscape into a targeted, accelerated search process. This guide provides an objective comparison between established human-expert workflows and emerging AI-driven platforms, focusing on their performance in real-world discovery tasks. We frame this analysis within the broader thesis of how AI is augmenting and, in some cases, transforming the role of human researchers by leveraging massive datasets, predictive modeling, and robotic automation to guide exploration with unprecedented efficiency.

The following analysis synthesizes experimental data and performance metrics from recent peer-reviewed literature and commercial platforms to offer a clear, evidence-based comparison. We examine specific case studies across materials science and drug discovery, detailing methodologies, quantitative outcomes, and the essential tools that enable this new paradigm.

Comparative Analysis: AI Platforms vs. Human Experts

The table below summarizes key performance metrics from recent studies and platforms, directly comparing the output of AI-guided systems with traditional human-led discovery.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of AI-Guided Discovery vs. Traditional Methods

| Metric | AI-Guided Discovery | Traditional Human-Led Discovery | Source/Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discovery Speed | 18 months from target to Phase I trials (drug discovery) [6]; 3 months to explore >900 chemistries (materials) [5] | ~5 years for discovery and preclinical work (drug discovery) [6] | Insilico Medicine (AI); Industry Standard (Traditional) |

| Experimental Efficiency | 70% faster design cycles; 10x fewer compounds synthesized [6] | Requires synthesis and testing of thousands of compounds [6] | Exscientia Platform Data |

| Chemical Space Explored | 1 million electrolytes screened from 58 data points [7]; 900+ chemistries tested [5] | Limited by cost, time, and human bias toward known chemical spaces [7] | University of Chicago Study; MIT CRESt System |

| Success in Identifying High-Performing Candidates | Discovery of a catalyst with 9.3x improvement in power density per dollar [5]; 4 novel high-performing battery electrolytes identified [7] | Relies on incremental improvement and expert intuition [3] | MIT CRESt System; University of Chicago Study |

| Data Utilization | Multimodal: Literature, experimental data, microstructural images, intuition [5] | Primarily experimental results and personal experience/intuition [5] | MIT CRESt System Description |

Inside the AI-Guided Workflow: Protocols and Platforms

To understand the performance metrics above, it is essential to examine the experimental protocols and technological architectures that enable AI-driven discovery. The following workflows are representative of the state-of-the-art.

The CRESt Platform for Materials Discovery

The Copilot for Real-world Experimental Scientists (CRESt) platform, developed by MIT researchers, exemplifies the integrated AI-guided approach [5].

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- Natural Language Input: A researcher converses with the CRESt system in natural language to define the objective (e.g., "find a high-activity, low-cost fuel cell catalyst").

- Multimodal Data Integration: The system's large multimodal model ingests diverse information, including scientific literature, known chemical compositions, and microstructural images, creating a knowledge embedding space.

- Search Space Reduction: Principal component analysis (PCA) is performed on this high-dimensional knowledge space to define a reduced, focused search space that captures most performance variability.

- Bayesian Optimization: An active learning loop using Bayesian optimization designs the next experiment within this reduced space.

- Robotic Execution: Robotic equipment, including liquid-handling robots and automated electrochemical workstations, synthesizes and tests the proposed material recipe.

- Analysis and Feedback: The results from characterization (e.g., automated electron microscopy) and performance testing are fed back into the model. The system can also use computer vision to monitor experiments and suggest corrections for reproducibility issues.

- Iterative Learning: The newly acquired data and human feedback are used to augment the knowledge base and redefine the search space for the next cycle [5].

ME-AI: Bottling Expert Intuition

The Materials Expert-Artificial Intelligence (ME-AI) framework takes a distinct approach by quantifying human expert intuition [3].

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- Expert Curation: A materials expert curates a refined dataset of 879 square-net compounds, selecting 12 experimentally accessible primary features (PFs) based on deep domain knowledge. These PFs include atomistic features (e.g., electronegativity, electron affinity) and structural features (e.g., square-net distance).

- Expert Labeling: The expert labels each compound in the database, for instance, classifying it as a topological semimetal (TSM) or a trivial material. This labeling uses available band structure data and, crucially, chemical logic for related compounds where direct data is absent.

- Model Training: A Dirichlet-based Gaussian-process model with a chemistry-aware kernel is trained on this curated dataset. Its mission is to learn emergent descriptors that predict the expert-classified properties from the primary features.

- Descriptor Discovery: The model successfully recovers the known "tolerance factor" descriptor and identifies new, interpretable emergent descriptors, such as one related to chemical hypervalency.

- Prediction and Validation: The trained model can then predict the properties of new, unknown compounds. Remarkably, the model demonstrated transferability by accurately classifying topological insulators in a different crystal structure (rocksalt) despite being trained only on square-net compounds [3].

AI-Driven Drug Discovery Platforms

In drug discovery, platforms from companies like Exscientia and Insilico Medicine have established robust AI-driven protocols [6].

Detailed Experimental Protocol (Exscientia's Centaur Chemist):

- Target Product Profile Definition: Precise criteria for the drug candidate (potency, selectivity, ADME properties) are defined.

- Generative AI Design: Deep learning models trained on vast chemical and experimental data propose novel molecular structures that satisfy the target profile.

- Patient-First Validation: AI-designed compounds are tested on patient-derived biological samples (e.g., tumor samples) in high-content phenotypic screens to ensure translational relevance.

- Iterative Design-Make-Test-Learn Cycle: The results from biological testing are fed back to the AI models to refine the next round of compound design, drastically compressing the cycle time [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details key reagents, software, and hardware solutions that form the foundation of modern AI-guided discovery platforms.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for AI-Guided Discovery

| Item Name | Type | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid-Handling Robot | Hardware | Automates precise dispensing of precursor chemicals in synthesis, enabling high-throughput experimentation [5]. |

| Automated Electrochemical Workstation | Hardware | Performs consistent, high-volume testing of material performance (e.g., catalyst activity, battery cycle life) [5] [7]. |

| Carbothermal Shock System | Hardware | Enables rapid synthesis of materials by quickly heating precursors to high temperatures [5]. |

| Automated Electron Microscope | Hardware | Provides high-throughput microstructural imaging for characterization; data is used for AI model feedback [5]. |

| Generative AI Design Software (e.g., Exscientia's DesignStudio) | Software | Proposes novel molecular structures that satisfy multi-parameter target product profiles [6]. |

| Active Learning Model | Software/Algorithm | Efficiently explores vast chemical spaces by selecting the most informative next experiments, minimizing the number of trials needed [7]. |

| Curated Experimental Materials Database (e.g., ICSD) | Data | Provides the structured, measurement-based data required to train and validate physics-aware ML models like ME-AI [3]. |

| High-Content Phenotypic Screening Platform | Assay/Technology | Tests AI-designed compounds on patient-derived samples to validate efficacy in biologically relevant models early in the discovery process [6]. |

| Aripiprazole (1,1,2,2,3,3,4,4-d8) | Aripiprazole-d8 (butyl-d8)|Deuterated Internal Standard | Aripiprazole-d8 (butyl-d8) is a deuterated internal standard for LC-MS/MS analysis of aripiprazole in biological samples. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 3-Bromopyridin-2-ol | 3-Bromo-2-hydroxypyridine | CAS 13466-43-8 | RUO | High-purity 3-Bromo-2-hydroxypyridine for pharmaceutical & organic synthesis research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

The evidence from cutting-edge research platforms indicates that the shift from serendipitous discovery to AI-guided targeted search is not only real but is also producing quantifiable advances in efficiency and outcomes. AI platforms demonstrate the ability to dramatically accelerate discovery timelines, explore broader chemical spaces, and identify high-performing candidates with fewer resources than traditional methods. However, the role of the human expert remains indispensable. The most successful frameworks, such as ME-AI and CRESt, are not replacements for researchers but rather powerful copilots. They excel at bottling expert intuition, handling multimodal data, and executing repetitive tasks, thereby augmenting human creativity and strategic thinking. The future of scientific discovery lies in this synergistic partnership, where AI handles the scale and speed of search, and human experts provide the domain knowledge, intuition, and ultimate scientific judgment.

The field of materials discovery stands at a pivotal juncture, where artificial intelligence promises to revolutionize traditional research methodologies. However, contrary to fears of wholesale automation, a new paradigm is emerging: human-AI collaboration. This approach, often termed "human-in-the-loop," strategically leverages the complementary strengths of both human researchers and AI systems to accelerate scientific discovery while maintaining the crucial role of human expertise. Within materials science and drug development, this collaborative model demonstrates that AI serves not as a replacement for researchers, but as a powerful assistant that amplifies human capabilities.

The fundamental premise of this paradigm recognizes that humans and AI systems possess distinct and complementary capabilities. While AI excels at processing vast datasets, identifying complex patterns, and performing high-throughput computations, human researchers provide irreplaceable qualities such as scientific intuition, creative problem-solving, and ethical judgment. Research from MIT Sloan School of Management formalizes this concept through the EPOCH framework, which categorizes essential human capabilities that remain difficult to automate: Empathy and Emotional Intelligence, Presence, Networking, and Connectedness, Opinion, Judgment, and Ethics, Creativity and Imagination, and Hope, Vision, and Leadership [8]. This framework provides a theoretical foundation for understanding why certain research functions remain firmly in the human domain, even as AI capabilities advance.

Quantitative Comparison: AI-Augmented vs. Traditional Research Workflows

The effectiveness of the human-in-the-loop approach is demonstrated through measurable improvements in research outcomes across multiple institutions. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from documented implementations:

| Research Institution | Application Focus | Key Performance Metrics | Human Researcher's Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carnegie Mellon University & University of North Carolina [9] | Development of strong yet flexible polymers | AI suggested experiments; humans provided feedback and adjustments in an iterative loop. | Dynamic guidance and expert interpretation |

| MIT (CRESt Platform) [5] | Discovery of fuel cell catalyst materials | Explored 900+ chemistries; conducted 3,500 tests; achieved a 9.3-fold improvement in power density per dollar versus pure palladium. | Natural language interaction, debugging, and final analysis |

| University of Washington Foster School of Business [10] | Evaluation of health equity proposals | AI helped non-experts match expert-level assessments, but experts spent more time scrutinizing AI suggestions. | Critical evaluation and nuanced judgment |

| SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory [11] | Particle accelerator operation | Humans managed complex, rare, or unexpected situations where AI systems struggle due to limited data. | Experience-based reasoning in high-stakes, uncertain environments |

The data consistently reveals a common theme: AI dramatically accelerates the process of data generation and initial analysis, while human researchers provide the critical strategic direction, contextual understanding, and validation necessary for transformative discoveries. As noted by researchers at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), the true potential of autonomous science lies not merely in speeding up discovery but in "completely reshaping the path from idea to impact" [12]. This synergy allows research teams to navigate the long-standing "valley of death" where promising laboratory discoveries fail to become viable products.

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Human-AI Collaboration

Case Study 1: Polymer Development at CMU/UNC

The collaborative development of advanced polymers illustrates a tightly integrated human-AI workflow. The experimental protocol followed a structured, iterative cycle [9]:

- Initialization: Researchers defined the target properties for the polymer, primarily seeking to overcome the typical trade-off between strength and flexibility.

- AI Suggestion: A machine-learning model analyzed the input parameters and suggested a specific series of chemical experiments.

- Human Execution & Feedback: Chemists at UNC-Chapel Hill conducted the suggested experiments using automated science tools.

- Measurement & Iteration: The produced materials were tested, and the resulting property data was fed back to the AI model, which then made adjustments for the next cycle.

Professor Frank Leibfarth from UNC-Chapel Hill emphasized that this was not a passive process for the human researchers: "In our human-augmented approach, we were interacting with the model, not just taking directions" [9]. This active collaboration combined the best of human intuition and machine efficiency, leading to the creation of novel polymers with excellent properties that could be used in applications from running shoes to medical devices.

Case Study 2: Catalyst Discovery via the MIT CRESt Platform

The CRESt (Copilot for Real-world Experimental Scientists) platform developed at MIT represents a more advanced implementation of the human-in-the-loop paradigm, incorporating robotic equipment and multimodal data processing. Its experimental methodology is comprehensive [5]:

- Natural Language Tasking: Human researchers converse with the CRESt system in natural language, specifying the goal to find promising material recipes for a specific project, such as a fuel-cell catalyst.

- Knowledge Integration: The system's models search through scientific literature and databases to create representations of potential recipes based on existing knowledge.

- Automated Experimentation: The system orchestrates a robotic workflow for sample preparation, characterization (including automated electron microscopy), and electrochemical testing.

- Active Learning & Optimization: Experimental results are used to train active learning models. These models use both literature knowledge and new data to suggest subsequent experiments, efficiently navigating the search space.

- Human Oversight & Debugging: The system uses cameras and vision models to monitor experiments, detect issues, and suggest solutions to human researchers via text and voice.

A critical finding from this research was the indispensability of the human researcher for ensuring reproducibility. As the MIT team noted, "CREST is an assistant, not a replacement, for human researchers. Human researchers are still indispensable" [5]. This protocol led to the discovery of a novel, multi-element catalyst that delivered record power density while using only one-fourth of the precious metals of previous designs.

Visualizing the Workflow: Human-AI Collaboration in Materials Discovery

The following diagram illustrates the integrated, cyclical workflow of a human-in-the-loop research paradigm, synthesizing the key stages from the documented case studies:

This workflow highlights the critical interaction points where human expertise guides the AI system, creating a continuous feedback loop that is more efficient and insightful than either could achieve independently.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The experiments cited rely on a range of specialized materials and reagents that form the foundation of materials discovery research. The table below details key components and their functions in the development of advanced materials, from polymers to energy solutions.

| Material/Reagent | Function in Research | Example Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Palladium / Platinum [5] | Serves as a catalytic component, often as a baseline or key element in catalyst formulations. | Fuel cell catalyst research (e.g., in the MIT CRESt project). |

| Formate Salt [5] | Acts as a fuel source for testing certain types of fuel cells. | Direct formate fuel cell performance testing. |

| Phase-Change Materials (e.g., paraffin wax, salt hydrates) [13] | Store and release thermal energy during phase transitions, used for testing thermal regulation. | Thermal energy storage systems for building decarbonization. |

| Electrochromic Materials (e.g., Tungsten trioxide) [13] | Change optical properties (e.g., tint) in response to an electrical stimulus. | Smart window technologies for energy-efficient buildings. |

| Bamboo Fiber Composites [13] | Provide a sustainable, high-strength reinforcement material for biopolymer composites. | Sustainable packaging and consumer product development. |

| Aerogels (Silica, Polymer-based) [13] | Provide ultra-lightweight, highly porous structures for insulation and energy storage. | Advanced applications in energy storage and biomedical engineering. |

| Metamaterials (Engineered composites) [13] | Exhibit properties not found in naturally occurring materials, like manipulating electromagnetic waves. | Improving 5G antennas, medical imaging, and seismic protection. |

| Co 101244 hydrochloride | Co 101244 hydrochloride | RUO Kinase Inhibitor | Co 101244 hydrochloride is a potent and selective research chemical. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Dimethyl-bisphenol A | Dimethyl-bisphenol A, CAS:1568-83-8, MF:C17H20O2, MW:256.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The evidence from leading research institutions confirms that the most productive path forward in materials science and drug development is one of collaboration, not replacement. AI systems excel as powerful assistants that can manage massive datasets, propose novel experiment candidates, and operate robotic labs at unprecedented scale. However, they fundamentally lack the EPOCH capabilities—the empathy, judgment, creativity, and vision—that human scientists bring to the research process [8]. The future of discovery lies not in choosing between human expertise and artificial intelligence, but in strategically integrating both to create research teams that are "stronger together than either one alone" [11]. This human-in-the-loop paradigm ensures that the acceleration of discovery is guided by the wisdom, ethical considerations, and creative insight that remain the hallmark of human intellect.

The discovery of new quantum materials, which exhibit exotic properties governed by quantum mechanics, has traditionally relied on a slow, iterative process combining theoretical modeling, serendipitous discovery, and the deep-seated intuition of experienced researchers [14] [2]. This "gut feeling" of human experts, developed through years of specialized research, allows them to make insightful leaps that are often inscrutable and impossible to quantify. However, this intuitive process is difficult to scale or replicate, creating a significant bottleneck in the search for next-generation materials for quantum computing, energy, and other advanced technologies [14].

The rise of Artificial Intelligence (AI) promises to accelerate materials discovery by rapidly screening vast chemical spaces. Yet, purely data-driven AI models often struggle where human experts excel: in understanding complex, qualitative properties of quantum materials that are beyond the reach of quantitative modeling [2]. This case study examines a groundbreaking approach that bridges this gap—the Materials Expert-AI (ME-AI) framework developed by researchers from Cornell and Princeton Universities. We will objectively compare this human-in-the-loop AI strategy against both conventional human-led research and purely data-driven AI platforms, analyzing its effectiveness in reproducing and articulating a researcher's intuition for discovering new quantum materials.

Experimental Comparison: ME-AI vs. Alternative Discovery Methods

The following analysis compares three distinct paradigms in quantum materials discovery: the novel ME-AI framework, traditional expert-led research, and fully automated AI-driven platforms.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Quantum Material Discovery Methodologies

| Feature | ME-AI Framework [2] | Traditional Expert-Led Research | Purely Data-Driven AI Platforms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Approach | Hybrid human-AI collaboration; expert-curated data and features inform machine learning. | Relies on researcher experience, reasoning, and serendipitous discovery. | Indiscriminate analysis of large datasets without expert guidance. |

| Role of Intuition | Expert intuition is "bottled" into quantifiable descriptors for the model. | Central, but implicit and difficult to articulate or transfer. | Not incorporated; operates as a "black box" based on statistical correlations. |

| Scalability | High potential; expert reasoning is captured and can be applied to larger datasets. | Inherently low; limited by the individual researcher's time and cognitive capacity. | Very high; can process massive volumes of data rapidly. |

| Articulation of Insight | High; machine explains its reasoning, making the expert's implicit process apparent. | Low; intuitive leaps are often described as a "gut feeling" that is hard to formalize. | Variable; some models offer explainability, but insights may lack physical meaning. |

| Key Limitation | Dependent on quality and scope of expert-curated initial data. | A non-replicable, scarce resource that is difficult to scale. | Prone to generating misleading correlations from poorly curated data [2]. |

Table 2: Performance Metrics in a Model Discovery Problem

| Metric | ME-AI Framework Performance [2] | Estimated Human Expert Baseline | Estimated Pure AI Baseline |

|---|---|---|---|

| Problem Scope | 879 materials screened for a specific desirable characteristic. | Manual review of a limited subset due to time constraints. | Could screen all 879, but with risk of false positives/negatives. |

| Accuracy in Reproducing Expert Insight | Successfully reproduced the expert's intuition and expanded upon it. | N/A (Establishes the benchmark) | Unpredictable; may miss criteria important to domain experts. |

| Generalization Ability | Demonstrated exciting generalization by predicting similar materials in a different set of compounds. | High, but slow and labor-intensive. | Can be high, but is highly dependent on data quality and model design. |

| Interpretability of Output | Model provided reasoning that the expert found logical and insightful. | Intuitive but difficult to articulate fully. | Often low; results can be a "black box" without clear physical rationale. |

Experimental Protocol: The ME-AI Methodology

The ME-AI framework was implemented through a structured, collaborative protocol between machine learning specialists and a domain expert, in this case, Professor Leslie Schoop and her research group at Princeton University, who study quantum materials [2].

Step-by-Step Workflow

The experimental workflow is designed to systematically encode human expertise into a machine-learning model.

ME-AI Workflow for Material Discovery

Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The following table details the essential "research reagents"—both data and software components—used in the ME-AI experiment.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for the ME-AI Framework

| Research Reagent | Type | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Expert-Curated Material Set | Data | A labeled dataset of 879 materials, curated and classified by a domain expert, serving as the ground truth for model training. |

| Human Expert Intuition | Knowledge | The implicit reasoning and "gut feeling" of the researcher, which the model aims to quantify and replicate. |

| Machine Learning Model | Software | The core algorithm that learns the mapping between material descriptors and the target property from the expert-curated data. |

| Material Descriptors | Data Features | Quantifiable parameters (e.g., structural, electronic) that the model uses to understand and predict material properties. |

| Validation Dataset | Data | A separate set of compounds, distinct from the training set, used to test the model's ability to generalize its learned intuition. |

Results and Interpretation: Quantifying the Gut Feeling

The outcome of the ME-AI experiment demonstrated a successful transfer and augmentation of human expertise. The model did not merely mimic the expert's prior classifications; it produced a generalized insight that the expert recognized as valid and insightful. As Professor Schoop noted upon reviewing the model's output, "Oh, that makes a lot of sense," indicating that the AI had captured the underlying logic of her thought process [2].

A key advantage of the ME-AI framework is its ability to articulate the intuitive process. As lead researcher Professor Eun-Ah Kim explained, "When a human has a gut feeling, it happens too quickly for them to spell it out. They know it's right, but they wouldn't necessarily articulate their process. In contrast, a machine is very good at explaining how it's reached a conclusion" [2]. This creates a powerful feedback loop where the machine makes the expert's implicit reasoning explicit, potentially leading to new scientific understanding.

This case study demonstrates that the most promising path for AI in complex scientific fields like quantum materials discovery is not to replace human experts, but to collaborate with them. The ME-AI framework provides a structured methodology to "bottle" invaluable human intuition, creating scalable, articulate, and insightful AI partners. This hybrid approach leverages the unique strengths of both humans and machines: the pattern-recognition and processing power of AI, and the contextual, conceptual understanding of the human researcher. As these collaborative tools mature, they promise to significantly accelerate the discovery of the quantum materials that will underpin future technological revolutions.

AI in Action: Platforms, Workflows, and Real-World Breakthroughs

The Experimental Workhorse: Core Components of an Autonomous Lab

The following diagram illustrates the integrated, closed-loop workflow of a multimodal AI system like CRESt, which combines computational planning with robotic execution to accelerate discovery.

The experimental realization of systems like CRESt relies on specific, high-purity materials and advanced robotic equipment. The table below details key research reagents and their functions in the discovery of advanced electrocatalysts, as demonstrated in CRESt's fuel cell research [5] [15] [16].

| Research Reagent / Equipment | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Palladium & Platinum Precursors | Served as primary catalytic elements in the search for efficient fuel cell catalysts [5]. |

| Base Metal Precursors (Cu, Au, Ir, etc.) | Formed multi-element catalysts to reduce precious metal content and optimize the coordination environment [5]. |

| Formate Salt Solution | Used as the fuel source during electrochemical testing to evaluate catalyst performance in direct formate fuel cells [15]. |

| Liquid-Handling Robot | Automated the precise dispensing and mixing of up to 20 precursor molecules to create numerous material recipes [5]. |

| Carbothermal Shock System | Enabled rapid synthesis of materials, including high-entropy alloys, by subjecting precursors to extreme temperatures [15]. |

| Automated Electrochemical Workstation | Performed high-throughput testing (e.g., 3,500 tests) to characterize catalyst performance metrics like power density [5]. |

| Automated Electron Microscope | Provided microstructural imaging and characterization of synthesized materials, with data fed back to the AI model [5]. |

Experimental Protocols & Performance Benchmarking

Detailed Experimental Methodology

The following diagram specifics the iterative "active learning" cycle that enables AI platforms like CRESt to efficiently optimize materials through sequential rounds of computation and experimentation.

In a landmark study, CRESt's protocol was applied to discover a high-performance, low-cost electrocatalyst for direct formate fuel cells, a technology with potential for clean energy generation [15]. The core objective was to identify a multi-element catalyst that would minimize the use of precious metals like palladium while maximizing power density.

Key Experimental Parameters & Analysis Methods:

- Synthesis: The system employed a carbothermal shock method for rapid synthesis of nanoparticle catalysts, allowing for quick iteration of over 900 distinct material chemistries [5] [15].

- Performance Testing: An automated electrochemical workstation conducted 3,500 tests to measure critical performance indicators, most notably the power density of the catalysts in a working fuel cell [5].

- Characterization: Automated electron microscopy and X-ray diffraction (XRD) were used for microstructural imaging and phase identification, providing visual data on the synthesized materials [5].

- Anomaly Detection: Computer vision models monitored experiments in real-time, detecting issues such as pipette misplacements or sample deviations that could affect reproducibility [16].

Quantitative Performance: AI vs. Human-Led Research

The true measure of an experimental system lies in its results. The table below provides a quantitative comparison of the performance of the CRESt platform against traditional, human-led research methodologies, based on its documented success in electrocatalyst discovery [5] [15] [16].

| Metric | CRESt AI Platform | Traditional Human-Led Research |

|---|---|---|

| Experiment Duration | ~3 months [5] [16] | Typically years for similar complexity [17] [18] |

| Experiments/Compositions Tested | 900+ chemistries, 3,500 electrochemical tests [15] | Limited by manual synthesis and testing capabilities [18] |

| Search Space Complexity | Optimized in octonary (8-element) space [15] | Often limited to ternary or quaternary spaces due to complexity [19] |

| Key Discovery | Pd-Pt-Cu-Au-Ir-Ce-Nb-Cr catalyst [15] | Typically focuses on simpler compositions [19] |

| Performance Improvement | 9.3x power density per dollar vs. pure Pd [5] [16] | Incremental improvements are more common [17] |

| Precious Metal Content | 1/4 of previous devices [5] | Often relies on higher precious metal loading [5] |

| Data Integration | Multimodal: literature, images, experimental data [5] [15] | Primarily experimental data, with limited literature integration |

Discussion: The Evolving Roles of AI and Human Expertise

The emergence of platforms like CRESt does not render human researchers obsolete but rather redefines their role in the discovery process. As noted by MIT's Ju Li, "CRESt is an assistant, not a replacement, for human researchers" [5] [16]. The system excels at executing and optimizing within a defined framework, but human scientists remain indispensable for setting strategic research goals, providing critical domain knowledge, and interpreting complex, unexpected results.

This human-AI collaboration is key to overcoming a major challenge in materials science: the "valley of death" where promising lab discoveries fail to become viable products [12]. By integrating considerations of cost, scalability, and performance from the earliest stages of research, autonomous platforms can help ensure new materials are "born qualified" for real-world application [12].

The future of materials discovery lies not in a choice between human expertise and artificial intelligence, but in a synergistic partnership that leverages the strengths of both.

The discovery and synthesis of novel materials are critical for advancing technologies in energy storage, quantum computing, and sustainable chemistry. Traditional research, reliant on human intuition and manual experimentation, often requires over a decade to move from conceptualization to practical application [20] [21]. Autonomous laboratories represent a transformative shift, integrating artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, and high-throughput computation to accelerate this process dramatically. This guide provides an objective comparison of two leading approaches: the A-Lab, an autonomous system for inorganic powder synthesis, and the ME-AI framework, which codifies human expert intuition. The core distinction lies in their operational paradigm; A-Lab focuses on robotic execution of synthesis and characterization, while ME-AI enhances human decision-making by uncovering deep material descriptors. Performance data indicates that these AI-driven platforms can achieve a 10-100x faster discovery rate compared to traditional methods, potentially reducing development cycles from years to months [20] [22]. This analysis examines their experimental protocols, quantitative performance, and respective roles within the research ecosystem, providing researchers with a clear framework for evaluation and adoption.

This section details the core architectures and measurable outputs of the A-Lab and ME-AI platforms, with comparative data presented in Table 1.

The A-Lab: An Autonomous Synthesis Platform The A-Lab, developed by researchers at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, is a fully integrated robotic system designed for the solid-state synthesis of novel inorganic materials [23] [24]. Its operation is a closed-loop process: given a target material, AI models propose synthesis recipes, robotic arms execute the powder handling and heating, and X-ray diffraction (XRD) characterizes the products. Machine learning then analyzes the results, and an active learning algorithm, ARROWS3, proposes improved follow-up recipes without human intervention [23]. This system operates 24/7 in a 600-square-foot lab, capable of processing 100-200 samples per day and testing 50-100 times more samples than a human researcher [24]. In its inaugural demonstration, the A-Lab successfully synthesized 41 out of 58 novel, computationally predicted compounds over 17 days, achieving a 71% success rate [23].

The ME-AI Framework: Augmenting Human Expertise In contrast, the Materials Expert-Artificial Intelligence (ME-AI) framework does not perform physical experiments. Instead, it is a machine-learning tool designed to "bottle" the intuition of expert materials scientists [3]. ME-AI learns from expertly curated, experimental data to identify quantitative descriptors that predict material properties. In one application focused on identifying topological semimetals (TSMs) within square-net compounds, ME-AI was trained on a set of 879 compounds described by 12 experimental features. It successfully recovered a known expert-derived structural descriptor (the "tolerance factor") and identified new ones, including a purely atomistic descriptor related to hypervalency [3]. Its key achievement is transferability; a model trained solely on square-net TSM data correctly classified topological insulators in rocksalt structures, demonstrating an ability to generalize learned principles beyond its initial training set [3].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of AI-Driven Platforms vs. Human Experts

| Feature | A-Lab (Autonomous Robotics) | ME-AI (Expert-Augmentation) | Traditional Human-Led Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Fully autonomous synthesis & characterization [23] | Discovering predictive material descriptors [3] | Manual experimentation and analysis |

| Throughput | 100-200 samples per day [24] | Analysis of 879+ compounds in a single study [3] | Limited by manual processes and speed |

| Success Metric | 71% (41/58) novel compounds synthesized [23] | Identified new descriptors; demonstrated model transferability [3] | Highly variable; discovery can take a decade [21] |

| Key Strength | Closed-loop, rapid iteration from prediction to synthesis [23] [20] | Embeds deep chemical intuition; highly interpretable results [3] | Leverages broad, creative scientific insight |

| Experimental Role | Replaces human in manual tasks and initial decision-making | Augments and explicates human expert intuition | Direct, hands-on involvement in all stages |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Understanding the precise methodologies of these platforms is crucial for evaluating their capabilities and limitations.

A-Lab's Autonomous Synthesis and Optimization Protocol

The A-Lab's workflow for synthesizing a novel inorganic powder involves a multi-stage, iterative protocol as shown in Figure 1.

- Target Identification and Validation: Targets are selected from computational databases like the Materials Project, focusing on compounds predicted to be thermodynamically stable (on the convex hull) and air-stable [23].

- Literature-Inspired Recipe Generation: For each new compound, the system uses natural-language models trained on historical synthesis literature to propose initial precursor sets and a heating temperature [23].

- Robotic Execution:

- Preparation: Precursor powders are automatically dispensed and mixed by a robotic arm before being transferred into an alumina crucible.

- Heating: A second robotic arm loads the crucible into one of four available box furnaces for heating.

- Characterization: After cooling, the sample is ground into a fine powder and its X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern is measured [23].

- Automated Data Analysis: The XRD pattern is analyzed by probabilistic machine learning models to identify phases and their weight fractions. This is followed by automated Rietveld refinement to confirm the results [23].

- Active Learning Loop: If the target yield is below 50%, the active learning algorithm (ARROWS3) takes over. It uses a growing database of observed pairwise solid-state reactions and ab initio reaction energies to propose alternative synthesis routes with a higher driving force to form the target, avoiding kinetic traps [23]. The loop continues until a high-yield recipe is found or all options are exhausted.

Figure 1: The A-Lab's closed-loop, autonomous workflow for materials synthesis and optimization.

ME-AI's Descriptor Discovery Protocol

The ME-AI framework follows a distinct, data-centric protocol to uncover the hidden rules experts use to identify promising materials, as shown in Figure 2.

- Expert-Led Data Curation: A materials expert (ME) assembles a refined dataset focused on a specific class of materials (e.g., square-net compounds). The MEs define the primary features (PFs), which are basic atomistic or structural properties like electronegativity, electron affinity, and specific crystallographic distances [3].

- Expert Labeling: Each compound in the dataset is labeled by the expert based on the target property. This is done through direct band structure analysis when available, or by applying chemical logic and analogy for related compounds or alloys [3]. This step encodes human intuition into the dataset.

- Model Training and Descriptor Discovery: A Dirichlet-based Gaussian-process model with a chemistry-aware kernel is trained on this curated dataset. The model's mission is not just to classify materials, but to learn the emergent descriptors—combinations of the primary features—that are predictive of the target property [3].

- Validation and Interpretation: The resulting model is interpreted to articulate the discovered descriptors. Its performance and, crucially, its transferability to other material families (e.g., applying a model trained on square-nets to rocksalt structures) are rigorously tested [3].

Figure 2: The ME-AI workflow for translating expert intuition into quantitative, actionable material descriptors.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The effectiveness of autonomous platforms depends on specialized materials, software, and hardware. Table 2 lists key components cited in the experimental results.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Autonomous Materials Discovery

| Item | Function in the Experiment | Source / Example |

|---|---|---|

| Solid-State Precursor Powders | Starting ingredients for solid-state synthesis of inorganic powders. The A-Lab's library contains ~200 different precursors [24]. | Various commercial chemical suppliers |

| Alumina Crucibles | Containers for holding powder samples during high-temperature reactions in box furnaces [23]. | Laboratory equipment suppliers |

| Ab Initio Computational Databases | Sources of predicted stable materials used as synthesis targets and for calculating thermodynamic driving forces [23]. | The Materials Project [23], Google DeepMind GNoME [21] |

| Historical Synthesis Data | Training data for natural-language models that propose initial, literature-inspired synthesis recipes [23]. | Text-mined from scientific literature [23] |

| Experimental Crystal Structure Database | Source of experimental structures for training ML models that analyze and identify phases from XRD patterns [23]. | Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [23] |

| Structural Constraint Software | Software tools that steer generative AI models to create materials with specific geometric patterns associated with quantum properties [25]. | SCIGEN (Structural Constraint Integration in GENerative model) [25] |

| Anisoin | Anisoin, CAS:119-52-8, MF:C16H16O4, MW:272.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2-Hydroxypropyl stearate | Propylene Glycol Monostearate for Research | Research-grade Propylene Glycol Monostearate (PGMS) for scientific study. Applications include food science and pharmaceuticals. For Research Use Only. |

The comparison reveals that the choice between autonomous platforms depends on the research goal. The A-Lab excels in rapid, high-volume validation of computationally predicted materials, physically generating samples and iterating recipes with superhuman endurance. Its performance demonstrates that the integration of computation, historical data, and robotics can successfully close the loop on materials synthesis [23]. In contrast, ME-AI aims to deepen fundamental understanding, providing interpretable descriptors that capture the nuanced intuition of expert researchers, with a proven ability to generalize across material classes [3].

Rather than a simple replacement narrative, the future of materials discovery lies in synergistic collaboration between human and artificial intelligence. AI-driven robotic systems like A-Lab and tools like SCIGEN [25] can shoulder the burden of repetitive tasks and vast exploration, freeing human researchers to formulate deeper hypotheses, design more creative experiments, and interpret complex results. As these technologies mature, they promise to form an integrated ecosystem where AI handles high-throughput experimentation and initial screening, while scientists focus on high-level strategy and tackling the most profound scientific challenges. This partnership will be crucial for addressing urgent global needs in clean energy and sustainable technology development.

The discovery of new functional materials, crucial for technologies from renewable energy to next-generation displays, has traditionally been a slow and labor-intensive process guided by human intuition and experimentation. However, a transformative shift is underway with the emergence of GPU-accelerated AI platforms that can evaluate millions of molecular candidates orders of magnitude faster than conventional methods. This guide objectively compares the capabilities of these AI-driven platforms against traditional expert-led approaches, examining their performance, methodologies, and practical applications in discovering advanced catalysts and OLED materials. By synthesizing data from recent implementations, we provide researchers with a comprehensive framework for selecting and implementing these technologies, with a particular focus on their integration into existing scientific workflows and their profound impact on accelerating the materials discovery pipeline.

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Analysis of Screening Platforms

The transition to AI-driven discovery platforms represents not merely an incremental improvement but a fundamental shift in materials research scalability. The table below summarizes key performance metrics documented from recent implementations.

Table 1: Documented Performance Metrics of AI Platforms vs. Traditional Methods

| Platform/Method | Application Area | Screening Scale | Speed Improvement | Key Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NVIDIA ALCHEMI NIM [26] | OLED Materials Discovery | Billions of candidates | 10,000x faster | Evaluation of billions of molecules in seconds instead of days [27] |

| NVIDIA ALCHEMI NIM [26] | Catalyst Discovery | 10M cooling fluid & 100M catalyst candidates | 10x more candidates in same timeframe | Evaluation completed within weeks [26] |

| ME-AI Framework [3] | Topological Materials | 879 square-net compounds | Not specified | Transferability to new material classes (rocksalt structures) |

| OpenVS Platform [28] | Drug Discovery | Multi-billion compound libraries | 7 days for full screening | 14-44% hit rates for target proteins |

These performance gains stem from fundamental architectural advantages. GPU-accelerated platforms leverage parallel processing to evaluate thousands to millions of candidates simultaneously, while AI models learn underlying patterns to prioritize promising candidates, dramatically reducing the need for exhaustive physical simulations [26] [27]. This represents a paradigm shift from the traditional sequential experimentation and computation that has constrained materials discovery for decades.

Table 2: Qualitative Comparison of Discovery Approaches

| Feature | AI-Driven Platforms | Traditional Expert-Led Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Screening Throughput | Billions of candidates feasible | Limited to hundreds/thousands of candidates |

| Speed | Days to weeks for massive libraries | Months to years for similar scope |

| Basis for Discovery | Pattern recognition in high-dimensional data | Chemical intuition & incremental modification |

| Scalability | Highly scalable with computational resources | Limited by human resources & equipment |

| Interpretability | Varies (can be "black box") | High (based on established principles) |

| Data Requirements | Requires substantial training data | Leverages existing knowledge & expertise |

Platform-Specific Experimental Protocols and Workflows

NVIDIA ALCHEMI for Energy and Display Materials

The NVIDIA ALCHEMI platform employs a structured computational workflow that has demonstrated significant success in industrial applications. For ENEOS's catalyst discovery program, the workflow consists of several critical stages [26]:

- Candidate Generation: Computational creation of molecular structures based on chemical rules and prior knowledge.

- Batched Conformer Search: Using ALCHEMI NIM microservices to identify low-energy molecular shapes across thousands of candidates simultaneously.

- Batched Molecular Dynamics: Simulation of molecular behavior and properties under specified conditions.

- Prescreening Analysis: Computational ranking of candidates based on target properties, with only the most promising advancing to physical testing.

This workflow enabled ENEOS to evaluate approximately 10 million liquid-immersion cooling candidates and 100 million oxygen evolution reaction candidates within weeks—a tenfold increase over previous methods. A company representative noted, "We hadn't considered running searches at the 10-100 million scale before, but NVIDIA ALCHEMI made it surprisingly easy to sample extensively" [26].

Similarly, Universal Display Corporation applied ALCHEMI to OLED material discovery through a specialized protocol [26] [29]:

- Universe Definition: Acknowledging a search space of approximately 10^100 possible OLED molecules.

- AI-Accelerated Conformer Search: Using ALCHEMI to evaluate billions of candidate molecules up to 10,000× faster than traditional computational methods.

- Stability Simulation: Construction of simulation cells for each conformer to assess thermal processing stability.

- Parallel Molecular Dynamics: Running simulations across multiple NVIDIA GPUs in parallel, reducing simulation time from days to seconds.

UDC's leadership reported that this approach "completely change[s] the scale and speed of discovery" and enables researchers to "uncover opportunities and fast-track new materials quicker than we ever could before" [26].

ME-AI Framework for Topological Materials

The Materials Expert-Artificial Intelligence (ME-AI) framework represents a distinctive approach that specifically incorporates human expertise into the AI discovery process. Its experimental protocol includes [3]:

- Expert Curation: Compilation of 879 square-net compounds with 12 experimental features guided by materials expert intuition.

- Feature Selection: Focus on chemically meaningful atomistic and structural features including electron affinity, electronegativity, valence electron count, and structural distances.

- Expert Labeling: Manual classification of materials as topological semimetals through band structure analysis and chemical logic.

- Model Training: Implementation of a Dirichlet-based Gaussian-process model with a chemistry-aware kernel to learn descriptors.

- Validation: Testing transferability by applying the model to unrelated material families (rocksalt structures).

This hybrid approach successfully reproduced established expert rules for identifying topological semimetals while revealing hypervalency as a decisive chemical descriptor, demonstrating how AI can formalize and extend human intuition [3].

OpenVS Platform for Drug Discovery

The OpenVS platform employs a multi-stage filtering approach for virtual screening in drug discovery [28]:

- Library Preparation: Compilation of multi-billion compound libraries from available chemical databases.

- Active Learning Integration: Training target-specific neural networks during docking computations to triage promising compounds.

- Two-Stage Docking: Initial screening with Virtual Screening Express (VSX) mode followed by high-precision assessment with Virtual Screening High-precision (VSH) mode with full receptor flexibility.

- Binding Affinity Prediction: Use of improved RosettaGenFF-VS scoring function combining enthalpy calculations with entropy estimates.

- Experimental Validation: Synthesis and testing of top-ranking compounds, with structural validation via X-ray crystallography.

This protocol enabled the discovery of hit compounds for two unrelated targets (KLHDC2 and NaV1.7) with 14% and 44% hit rates respectively, completing screening in less than seven days using a high-performance computing cluster [28].

Workflow Visualization: AI-Driven Materials Discovery

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for AI-accelerated materials discovery, synthesizing common elements across the platforms discussed:

AI-Driven Materials Discovery Workflow

This workflow highlights the iterative filtering process where AI systems rapidly narrow billions of possibilities to tens of laboratory-testable candidates, with human expertise integrated at critical decision points to guide the discovery process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of accelerated screening platforms requires both computational and experimental components. The table below details essential "research reagent solutions" - key resources and their functions in the discovery pipeline.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Accelerated Materials Discovery

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in Discovery Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| GPU-Accelerated Computing Platforms | NVIDIA ALCHEMI NIM Microservices [26] | Provides batched conformer search and molecular dynamics for high-throughput screening |

| AI/ML Frameworks | ME-AI Gaussian-process model [3], OpenVS active learning [28] | Learns from expert-curated data to identify promising candidates and reduce search space |

| Specialized Instrumentation | Brookhaven's National Synchrotron Light Source II with Holoscan [26] | Enables real-time nanoscale imaging with sub-10 nanometer resolution for experimental validation |

| Data Management Systems | Materials data repositories with FAIR principles [30] | Ensures standardized, findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable data for AI training |

| Experimental Validation Platforms | Self-driving labs (SDLs) with defined autonomy metrics [31] | Automates physical synthesis and testing with minimal human intervention for rapid iteration |

| D-erythro-Ritalinic acid-d10 | Ritalinic Acid Reference Standard|CAS 19395-41-6 | Ritalinic acid is the primary metabolite of methylphenidate. This product is for research use only, such as analytical testing. It is not for human consumption. |

| (2-Chlorophenyl)(phenyl)methanone | (2-Chlorophenyl)(phenyl)methanone, CAS:5162-03-8, MF:C13H9ClO, MW:216.66 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

These resources collectively enable the seamless transition from computational prediction to experimentally verified materials, addressing the critical "last mile" of materials discovery that has traditionally represented the greatest timeline bottleneck.

The evidence from multiple implementations demonstrates that GPU-powered AI platforms fundamentally transform materials discovery by evaluating candidate spaces of unprecedented scale at speeds orders of magnitude beyond traditional approaches. These platforms do not render human experts obsolete but rather amplify their impact by handling computationally intensive screening tasks, allowing researchers to focus on higher-level strategy, interpretation, and validation. The most successful implementations create a synergistic relationship between artificial and human intelligence, combining the scalability of AI with the chemical intuition and contextual understanding of experienced scientists.

As these technologies continue evolving, their integration into materials research workflows will become increasingly seamless, with self-driving labs potentially closing the loop between prediction and validation. However, the critical role of researchers will shift from manual candidate selection to designing discovery frameworks, interpreting AI outputs, and integrating multidisciplinary knowledge. This transformation promises to accelerate the development of critically needed materials for energy, healthcare, and electronics, potentially reducing discovery timelines from years to weeks while exploring chemical spaces that were previously beyond practical consideration.

The field of materials science is undergoing a profound transformation as artificial intelligence transitions from a theoretical tool to an experimental partner. This shift represents a fundamental reimagining of the scientific method, where AI-generated hypotheses are systematically bridged with physical validation in self-optimizing research ecosystems. The integration of AI into materials discovery has created a new paradigm characterized by accelerated iteration cycles, reduced resource consumption, and enhanced exploration of chemical space. As research and development organizations increasingly adopt these technologies, understanding the comparative performance between AI-driven platforms and human expertise becomes critical for optimizing scientific workflows. Recent assessments indicate that materials R&D has reached an inflection point, with 46% of all simulation workloads now utilizing AI or machine-learning methods, signaling a mainstream adoption that demands rigorous performance comparison [32].

This comparative analysis examines the evolving relationship between computational prediction and experimental validation across multiple dimensions of materials research. By synthesizing data from recent studies, we quantify the performance differentials between AI-assisted and traditional human-expert approaches in key metrics including discovery rates, resource efficiency, and innovation quality. The findings reveal a complex landscape where AI systems demonstrate remarkable capabilities in specific domains while human expertise remains indispensable for contextual reasoning and strategic oversight. As the field progresses toward fully autonomous research systems, the optimal framework appears to be a synergistic partnership that leverages the respective strengths of computational and human intelligence.

Performance Metrics: Quantitative Comparison of AI vs. Human Experts

Rigorous evaluation of AI systems against human experts requires multidimensional assessment across discovery efficiency, resource utilization, and innovation quality. The following comparative analysis synthesizes data from recent studies and industrial implementations to provide a comprehensive performance benchmark.

Table 1: Comparative Performance Metrics for Materials Discovery

| Performance Metric | AI-Assisted Research | Traditional Human Research | Improvement Factor | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discovery Rate | 44% more materials discovered | Baseline | 1.44x | Industrial R&D Lab Study [33] |

| Patent Output | 39% more patents filed | Baseline | 1.39x | Industrial R&D Lab Study [33] |

| Prototype Development | 17% more product prototypes | Baseline | 1.17x | Industrial R&D Lab Study [33] |

| Research Efficiency | 13-15% overall R&D efficiency improvement | Baseline | 1.14x | Industrial R&D Lab Study [33] |

| Data Acquisition | 10x more data points collected | Steady-state sampling | 10x | Self-Driving Lab Implementation [34] |

| Project Cost | ~$100,000 savings per project | Traditional experimental costs | Significant reduction | Industry Survey [32] |

| Idea Generation | 57% automated | Manual design processes | N/A | Industrial R&D Lab Study [33] |

Beyond these quantitative metrics, the qualitative aspects of research output demonstrate significant differences between AI-assisted and traditional approaches. The same industrial study revealed that AI-enabled researchers produced discoveries with superior quality (as assessed by similarity to desired properties) and demonstrated greater novelty both structurally and in downstream patents. Patents filed by AI-assisted scientists used more novel technical terminology, an early marker of transformative innovation [33]. This suggests that AI assistance enables researchers to escape local optima and explore more diverse regions of materials space rather than simply accelerating incremental improvements.

The temporal dimension of research acceleration reveals interesting patterns across different stages of the discovery pipeline. AI adoption produced a clear step change in materials discovery and patent filings after approximately six months, while the increase in product prototypes took over a year to materialize. This progression aligns with the natural technology readiness level advancement, where fundamental discoveries must mature through development stages before manifesting as tangible prototypes [33]. The delayed prototype impact underscores that AI acceleration affects different research phases variably rather than producing uniform acceleration across the entire pipeline.

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for AI-Human Comparison

Industrial-Scale AI Implementation Study

The most comprehensive comparison of AI-assisted versus human-expert materials discovery comes from a large-scale industrial implementation study conducted across 1,018 scientists at a major U.S. industrial R&D lab. The study employed a wave rollout methodology that allowed for controlled comparison between treatment and control groups over nearly two years. Researchers implemented a graph neural network (GNN)-based diffusion model trained to generate candidate materials predicted to have specific properties through inverse design—where researchers provided target features and received plausible structures in return [33].

The experimental protocol involved several key phases: First, researchers established baseline productivity metrics for all participants over an initial observation period. The AI tool was then introduced to successive waves of researchers while maintaining a control group, enabling rigorous measurement of the tool's causal impact. Throughout the study period, researchers maintained detailed activity logs that captured time allocation across different research tasks. The validation mechanism included both quantitative output metrics (materials discovered, patents filed, prototypes developed) and qualitative assessments of novelty and quality through expert evaluation and analysis of patent terminology [33].

Autonomous Discovery with CRESt Platform

The Copilot for Real-world Experimental Scientists (CRESt) platform developed by MIT researchers represents a more integrated approach to AI-human collaboration. This system combines multimodal feedback incorporating information from scientific literature, chemical compositions, microstructural images, and human input to design and execute experiments. The platform employs robotic equipment including liquid-handling robots, carbothermal shock systems for rapid materials synthesis, automated electrochemical workstations, and characterization equipment including automated electron microscopy [5].

In a demonstration application, CRESt explored more than 900 chemistries and conducted 3,500 electrochemical tests over three months to develop an electrode material for direct formate fuel cells. The experimental protocol employed Bayesian optimization enhanced with literature knowledge embedding, where the system created representations of each recipe based on previous knowledge before conducting experiments. The system performed principal component analysis in this knowledge embedding space to obtain a reduced search space capturing most performance variability, then used Bayesian optimization in this reduced space to design new experiments [5]. After each experiment, newly acquired multimodal experimental data and human feedback were fed into a large language model to augment the knowledge base and redefine the search space, creating a continuous learning loop.

Dynamic Flow Experimentation for Inorganic Materials

A groundbreaking methodology for accelerating autonomous materials discovery comes from North Carolina State University's development of dynamic flow experiments within self-driving laboratories. This approach fundamentally redefines data utilization by continuously varying chemical mixtures through microfluidic systems and monitoring them in real-time, rather than waiting for steady-state conditions. Where traditional self-driving labs using steady-state flow experiments might generate a single data point after 10 seconds of reaction time, the dynamic flow system captures up to 20 data points at half-second intervals during the same period [34].

The experimental protocol employs microfluidic principles and real-time, in situ characterization to map transient reaction conditions to steady-state equivalents. Applied to CdSe colloidal quantum dots as a testbed, this approach demonstrated an order-of-magnitude improvement in data acquisition efficiency while reducing both time and chemical consumption compared to state-of-the-art self-driving fluidic laboratories. The continuous data stream enables machine learning algorithms to make smarter, faster decisions about subsequent experiments, honing in on optimal materials and processes in a fraction of the time required by traditional methods [34].

Workflow Visualization: AI-Human Collaboration Frameworks

The integration of AI into materials discovery has generated distinct workflow architectures that define the interaction patterns between computational and human intelligence. The following diagrams illustrate the primary frameworks emerging from recent research implementations.

AI-Human Collaborative Research Workflow: This diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of the CRESt platform, demonstrating how human expertise and AI systems interact throughout the discovery process. The framework highlights the continuous feedback loops between computational prediction and experimental validation, with human oversight maintaining strategic direction while AI optimizes tactical execution [5].