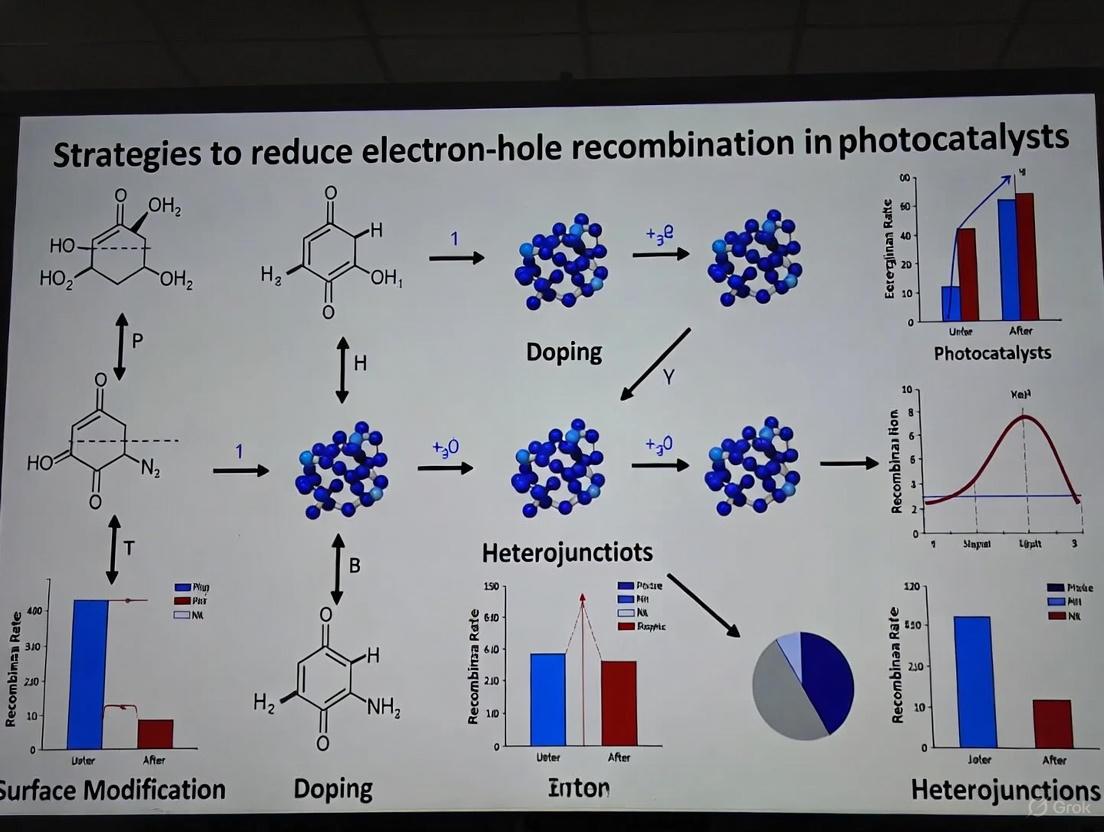

Advanced Strategies to Suppress Electron-Hole Recombination in Photocatalysts: From Mechanisms to Applications

Electron-hole recombination is a fundamental challenge that severely limits the efficiency of semiconductor photocatalysts.

Advanced Strategies to Suppress Electron-Hole Recombination in Photocatalysts: From Mechanisms to Applications

Abstract

Electron-hole recombination is a fundamental challenge that severely limits the efficiency of semiconductor photocatalysts. This article provides a comprehensive analysis of advanced strategies to suppress charge carrier recombination, a critical barrier in photocatalytic applications ranging from environmental remediation to energy conversion. We explore the foundational mechanisms of recombination, detail cutting-edge engineering methodologies like heterojunction construction and defect engineering, and discuss optimization techniques for real-world systems. The review also covers rigorous validation protocols and comparative performance analysis of emerging materials, offering researchers a structured framework to design high-performance, next-generation photocatalytic systems.

Understanding Electron-Hole Recombination: The Fundamental Bottleneck in Photocatalysis

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary fates of photogenerated electron-hole pairs in a semiconductor? When a semiconductor absorbs light with energy equal to or greater than its bandgap, electrons are excited from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB), creating electron-hole (e--h+) pairs [1] [2]. These charge carriers have three main possible fates [2]:

- Productive Separation and Transfer: The electrons and holes migrate to the catalyst surface without recombining and initiate reduction and oxidation reactions, respectively [1].

- Recombination: The electrons fall back into the holes, annihilating the pair. This can occur radiatively (emitting light/heat) or non-radiatively within the bulk or on the surface of the material, and it is the primary cause of low photocatalytic efficiency [2].

- Trapping: Electrons or holes can be temporarily captured by surface states or defect sites, which can sometimes delay recombination and facilitate interfacial charge transfer [2].

Q2: What is the "ABC model" and how does it describe recombination?

The ABC model is a common framework used to quantify recombination rates in semiconductors, particularly in devices like LEDs. It expresses the total recombination rate (R) as a function of the carrier concentration (n), breaking it down into three main contributions [3]:

R = An + Bn² + Cn³

- A - Shockley-Read-Hall (SRH) Coefficient: Represents linear, non-radiative recombination at defect sites or traps.

- B - Radiative Coefficient: Represents bimolecular radiative recombination, which has a quadratic dependence on carrier concentration.

- C - Auger Coefficient: Represents three-body non-radiative Auger recombination, which becomes dominant at very high carrier concentrations [3]. Advanced versions of this model also include an

f(n)term to account for carrier leakage outside the active region [3].

Q3: What are common material defects that act as non-radiative recombination centers? Defects in the crystal structure, particularly at the surface, create energy levels within the bandgap that act as efficient traps for charge carriers, promoting non-radiative recombination. Common defects include [3] [4]:

- Oxygen Vacancies: Common in metal oxides; they can sometimes be beneficial by creating active sites, but often act as recombination centers.

- Surface Epoxide and Carboxylic Groups: In carbon-based dots, these groups can act as centers for non-radiative electron-hole recombination, lowering photoluminescence quantum yield [3].

- Impurity Ions: Ions from the solution or synthesis process, such as O and OH radical species, can form traps [3].

Q4: What experimental techniques can diagnose charge carrier recombination? Several photoelectrochemical and spectroscopic techniques are used to probe recombination:

- Transient Absorption Spectroscopy (TAS): Directly monitors the decay kinetics of photogenerated charge carriers, allowing researchers to measure their recombination lifetimes [2].

- Photoluminescence (PL) Spectroscopy: The intensity of photoluminescence is inversely related to the recombination rate. A strong PL signal often indicates high radiative recombination, while quenching of PL suggests the presence of non-radiative pathways or effective charge separation [3] [4].

- Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): Provides information on charge transfer resistance at the semiconductor-electrolyte interface. A smaller semicircle in a Nyquist plot typically indicates lower resistance and more efficient charge separation [4].

- Mott-Schottky Analysis: Used to determine the flat-band potential and carrier density of a semiconductor, which are related to the space charge layer and its ability to separate electron-hole pairs.

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Photocatalytic Efficiency Due to Rapid Recombination

Problem: Your photocatalyst shows poor activity for reactions like dye degradation or water splitting, primarily because photogenerated electrons and holes recombine too quickly.

Investigation & Solution Strategy:

| Investigation Step | Observation / Technique | Suggested Cause | Potential Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analyze Recombination Kinetics | Perform Transient Absorption Spectroscopy or PL Spectroscopy. Observe rapid decay of signal [2]. | High density of bulk or surface defects acting as recombination centers. | • Improve crystallinity: Use high-temperature annealing to repair defects. • Surface passivation: Use chemical agents to cap dangling bonds [3]. |

| Check Charge Separation | Perform EIS. Observe a large semicircle, indicating high charge transfer resistance [4]. | Poor separation and migration of charges to the surface. | • Construct a heterojunction: Couple with another semiconductor to create an internal electric field [5]. • Facet engineering: Utilize natural charge separation between different crystal facets [6]. • Apply a co-catalyst: Use Pt or CoFeOx as an electron sink to extract charges [5] [6]. |

| Evaluate Defect States | Perform X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS). Analyze the presence of impurity atoms or unusual oxidation states [4]. | Unintentional defects or impurities introduced during synthesis. | • Refine synthesis parameters: Optimize precursor concentration, pH, and temperature. • Introduce beneficial defects: Controlled creation of oxygen vacancies can sometimes improve activity [4]. |

Inconsistency Between Experimental Data and the ABC Model

Problem: The efficiency versus carrier concentration curve of your device (e.g., an LED) is heavily skewed and does not match the symmetric curve predicted by the standard ABC model.

Investigation & Solution Strategy:

- Potential Cause: The standard ABC model only considers recombination inside the active region and may fail to account for carrier leakage or injection inefficiencies [3].

- Solution: Employ an extended ABC + f(n) model. The

f(n)term describes carriers that recombine outside the active region and can be expressed as a power series (e.g.,f(n) = an + bn² + cn³ + ...). Using this model with higher-order terms can more accurately explain the skewed experimental efficiency curves observed in real devices [3].

Quantitative Data on Recombination and Performance

Table 1: Common Recombination Pathways and Their Characteristics

| Recombination Type | Rate Dependence | Primary Cause | Typical Impact on Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shockley-Read-Hall (SRH) | Linear (An) [3] | Defects, impurities | Dominant at low carrier densities; significantly reduces low-current efficiency [3]. |

| Radiative | Quadratic (Bn²) [3] | Intrinsic band-to-band recombination | Fundamental limit; dominant in high-quality materials at intermediate currents [3]. |

| Auger | Cubic (Cn³) [3] | Three-particle collision | Dominant at very high carrier densities; causes efficiency droop at high currents [3]. |

| Carrier Leakage | Polynomial (f(n)) [3] | Injection inefficiency, overflow | Becomes significant at high currents; explained by extended ABC+f(n) model [3]. |

Table 2: Performance Improvement via Specific Strategies (Experimental Examples)

| Photocatalyst System | Strategy Employed | Key Metric & Improvement | Reference Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laâ‚‚TiOâ‚…-400 (Reduced) | Defect density modulation (Oxygen vacancies) [4] | Nâ‚‚ fixation yield: 158.13 μmol·gâ»Â¹Â·hâ»Â¹ [4] | [4] |

| BiVOâ‚„:Mo(NaOH)/CoFeOx | Electron Transfer Layer & Inter-facet junction [6] | Charge Separation Efficiency: >90% at 420 nm [6] | [6] |

| Ag/TiOâ‚‚/CNT | Co-catalyst & Carbon-based support [1] | Stability: Enhanced activity over 5 consecutive cycles [1] | [1] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Characterization Techniques

Protocol: Photoluminescence (PL) Spectroscopy for Recombination Assessment

Objective: To evaluate the relative rate of charge carrier recombination and assess the effectiveness of passivation or modification strategies.

Materials:

- Spectrofluorometer

- Solid sample holder or quartz cuvette (for powders or dispersions)

- Your photocatalyst powder or film

- Reference sample (e.g., unmodified catalyst for comparison)

Method:

- Sample Preparation: For powder samples, ensure a uniform thin layer in the solid holder. For dispersions, prepare a stable, sonicated colloidal solution in a quartz cuvette.

- Instrument Setup: Set the excitation wavelength to an energy above the bandgap of your material (e.g., 300-400 nm for TiOâ‚‚ or ZnO). Choose an appropriate excitation and emission slit width to achieve a strong signal without saturation.

- Measurement:

- Run an excitation-emission scan to find the optimal wavelengths, or

- Set a fixed excitation wavelength and acquire the emission spectrum.

- Perform the same measurement on your modified and unmodified samples under identical conditions.

- Data Analysis:

- Compare the peak intensity and peak shape. A significant quenching of the PL intensity in the modified sample indicates a reduction in radiative recombination, often due to improved charge separation or the introduction of non-radiative pathways that outcompete recombination [3] [4].

- Analyze the peak shift, which can provide information on changes in surface states or band structure.

Protocol: Probing Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) for Mechanistic Insight

Objective: To identify and confirm the primary reactive species involved in the photocatalytic degradation process, which indirectly informs on the success of charge separation.

Materials:

- Photoreactor with light source

- Scavengers: Isopropanol (for â—OH), p-benzoquinone (for â—Oâ‚‚â»), EDTA-2Na (for hâº), etc.

- Target pollutant (e.g., Methylene Blue solution)

- Your photocatalyst

Method:

- Baseline Reaction: Conduct a standard photocatalytic degradation experiment with your catalyst and the pollutant solution without any scavenger. Monitor the degradation rate (e.g., via UV-Vis spectroscopy).

- Scavenging Experiments: Repeat the baseline experiment, but in each run, add a small, controlled amount (e.g., 1 mM) of a specific scavenger to the reaction mixture.

- Data Analysis:

- Compare the degradation rates of all experiments.

- A significant decrease in the degradation rate in the presence of a particular scavenger indicates that the corresponding reactive species (e.g., â—OH, â—Oâ‚‚â», hâº) plays a crucial role in the mechanism [1].

- This confirms that the photogenerated charges are successfully separated and transferred to surface reactants to form ROS.

Visualization of Processes and Strategies

Photocatalytic Process and Recombination Pathways

Diagram Title: Photocatalytic charge generation and fate pathways.

Advanced Strategy: Intensified Inter-Facet Charge Separation

Diagram Title: ETL and inter-facet junction enhance charge separation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Photocatalyst Development

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) | Surface Etching & Defect Creation: Selectively dissolves atoms (e.g., V in BiVOâ‚„) to create oxygen vacancies and incorporate modifiers (Na) [4] [6]. | Concentration, temperature, and etching time must be optimized to avoid structural collapse. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Surface Passivation Agent: Binds to surface dangling bonds, reducing non-radiative recombination pathways and increasing photoluminescence quantum yield [3]. | Molecular weight and functional end groups influence passivation effectiveness. |

| Platinum (Pt) Precursors | Co-catalyst / Electron Sink: Deposited as nanoparticles to form a Schottky barrier, effectively trapping electrons and suppressing eâ»-h⺠recombination [5] [2]. | Loading amount and dispersion are critical; high loadings can block active sites. |

| Scavenger Compounds | Mechanistic Probes: Used in trapping experiments to identify the primary reactive species (e.g., Isopropanol for â—OH, p-Benzoquinone for â—Oâ‚‚â») [1]. | Must be used at appropriate concentrations to ensure specificity for the target species. |

| Cobalt-Iron (CoFeOx) Precursors | Oxidation Co-catalyst: Specifically extracts and utilizes photogenerated holes for oxidation reactions, enhancing spatial charge separation [6]. | Synergistic effect between Co and Fe improves Oâ‚‚ evolution activity. |

| Reducing Agents (NaBHâ‚„, etc.) | Defect Engineering: Used in post-synthetic reduction treatments to create oxygen vacancies, modulating defect density and electronic structure [4]. | Reduction temperature and atmosphere are key parameters controlling vacancy concentration. |

| 3PO | 3PO, CAS:13309-08-5, MF:C13H10N2O, MW:210.23 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 1233B | 1233B, MF:C18H30O6, MW:342.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic Recombination Pathways

FAQ: Understanding Recombination in Photocatalysts

What are electron-hole pairs and why is their recombination a problem? When a photocatalyst absorbs light with energy equal to or greater than its band gap, electrons ((e^-)) are excited from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB), leaving positively charged holes ((h^+)) in the VB. These are called electron-hole pairs, and they are the primary drivers of photocatalytic reactions [7] [8]. Recombination is the process where these photo-generated electrons and holes annihilate each other before they can participate in surface redox reactions [9]. This process wastes the absorbed light energy, typically converting it to heat or light, and significantly reduces the efficiency of photocatalytic processes such as pollutant degradation or hydrogen production [10] [7].

What is the fundamental difference between intrinsic and extrinsic recombination? The fundamental difference lies in their origin. Intrinsic recombination is an inherent property of the pure semiconductor material and cannot be completely eliminated. Extrinsic recombination is caused by defects or impurities in the crystal structure, which introduce trapping sites for charge carriers [9]. Therefore, strategies to mitigate intrinsic recombination focus on material design to alter the fundamental path of the charges, while strategies to reduce extrinsic recombination focus on improving material synthesis and processing to minimize defects.

How can I quickly diagnose if recombination is the main issue in my photocatalytic system? A significant indicator of severe recombination is low photocatalytic activity despite confirmed strong light absorption by your material. Advanced characterizations can provide definitive evidence:

- Photoluminescence (PL) Spectroscopy: A high-intensity PL signal often indicates efficient radiative recombination of electrons and holes. A decrease in PL intensity after modifying a catalyst suggests suppressed recombination [11].

- Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): A smaller arc radius in a Nyquist plot typically signifies lower charge transfer resistance and more efficient separation of photo-generated charges, implying reduced recombination [11].

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Mitigating Recombination

This guide helps diagnose the dominant recombination type in your experiments and provides targeted solutions.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Recombination Pathways

| Observed Problem | Likely Primary Cause | Recommended Solution | Experimental Protocol to Verify |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low efficiency despite high light absorption; performance is independent of defect engineering. | Intrinsic Recombination (Radiative or Auger) [9] | Create heterojunctions (e.g., Z-scheme) to spatially separate electrons and holes [11] [8]. | Perform PL spectroscopy: Compare intensity of pristine and composite catalyst. A significant decrease in composite confirms suppressed recombination [11]. |

| Performance degrades with increased crystallinity or is highly sensitive to synthesis temperature/conditions. | Extrinsic Recombination (Shockley-Read-Hall) via defects [9] | Optimize synthesis to reduce crystal defects; use surface passivation; control doping levels to avoid introducing trap states [9] [8]. | Conduct EIS measurements: A smaller arc radius in the composite versus the pristine material indicates improved charge separation and reduced trapping [11]. |

| Rapid performance loss under prolonged illumination (photocorrosion). | Extrinsic Recombination activated by surface defects acting as recombination centers. | Use co-catalysts or form protective layers (e.g., oxide shells) to stabilize surface sites [8]. | Test photostability over multiple cycles (e.g., 3-5 cycles). Stable performance suggests mitigated surface degradation [11] [8]. |

| Poor performance under high-intensity light or in highly doped materials. | Auger Recombination (an intrinsic process) [9] | Modify the light intensity or adjust the dopant concentration to levels where Auger recombination is not the dominant loss mechanism [9]. | Model recombination rates using established parameterisations for Auger coefficients to identify critical injection/doping levels [9]. |

Experimental Protocols for Recombination Analysis

Protocol 1: Probing Reduction via Photoluminescence (PL) Spectroscopy

This protocol is based on the characterization of ZIF-11/g-C3N4 composites [11].

- Sample Preparation: Dilute your photocatalyst powder in a non-absorbing solvent (e.g., ethanol) to form a slurry. Deposit the slurry onto a substrate and dry to form a thin, uniform film for analysis.

- Measurement: Use a PL spectrometer with a fixed excitation wavelength. Scan the emission wavelengths to obtain the PL spectrum.

- Analysis: Compare the PL intensity of your modified photocatalyst (e.g., a composite or doped sample) with the pristine material. A lower PL intensity in the modified sample indicates a reduction in the radiative recombination of charge carriers, confirming the success of your strategy [11].

Protocol 2: Validating Charge Separation with Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS)

This protocol is adapted from the evaluation of the ZIF-11/g-C3N4 nanostructure [11].

- Electrode Preparation: Fabricate a working electrode by drop-casting a dispersion of your photocatalyst material onto a conductive substrate (e.g., FTO glass).

- Measurement Setup: Use a standard three-electrode electrochemical cell (working electrode, platinum counter electrode, and reference electrode) filled with an electrolyte solution (e.g., 0.1 M Naâ‚‚SOâ‚„). The measurement is often conducted under light illumination.

- Data Acquisition: Measure the impedance over a frequency range (e.g., from 100,000 Hz to 0.1 Hz) at the open-circuit potential.

- Analysis: Plot the data on a Nyquist plot ( -Z'' vs. Z'). A smaller semicircle (arc radius) for your modified photocatalyst compared to the pristine material indicates a lower charge transfer resistance, demonstrating more efficient charge separation and reduced recombination [11].

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the competitive pathways that photo-generated charge carriers can take, leading to either productive reactions or energy-wasting recombination.

Charge Carrier Pathways in Photocatalysis

This workflow outlines the key experimental steps for diagnosing recombination issues and validating mitigation strategies.

Recombination Diagnosis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Photocatalyst Synthesis and Modification

| Material / Reagent | Function in Recombination Mitigation | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Urea | A common, low-cost precursor for the thermal synthesis of graphitic carbon nitride (g-C₃N₄), a metal-free polymer semiconductor used to form heterojunctions [11]. | Used to synthesize g-C₃N₄ for the Z-scheme ZIF-11/g-C₃N₄ composite, which demonstrated reduced electron/hole recombination [11]. |

| Zinc Acetate Dihydrate | A metal source for the synthesis of zinc-based frameworks and semiconductors like Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks (ZIFs) and ZnO [11]. | Served as the zinc source for synthesizing ZIF-11 in the ZIF-11/g-C₃N₄ composite [11]. |

| Benzimidazole | An organic linker molecule used in the construction of ZIFs. It coordinates with metal ions to form porous crystalline structures with high surface areas [11]. | Used as the imidazolate linker to form the ZIF-11 structure in the composite photocatalyst [11]. |

| Precursor for Dopants (e.g., Metal Salts) | Introducing controlled impurities (doping) to create p-type or n-type semiconductors. This can create internal fields that help separate charges and reduce recombination [8]. | Doping with foreign elements is a common strategy to introduce point defects that alter electronic properties and suppress recombination [8]. |

| 3-AQC | 3-AQC Reagent | |

| AG311 | AG311|Complex I Inhibitor|HIF-1α Stabilization Blocker | AG311 is a small molecule inhibitor of mitochondrial complex I and hypoxia-induced HIF-1α stabilization. For research use only. Not for human consumption. |

Impact of Recombination on Photocatalytic Efficiency and Quantum Yield

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the fundamental reason that electron-hole recombination limits photocatalytic efficiency? Recombination is a primary energy loss pathway. When photogenerated electrons and holes recombine, often on picosecond to nanosecond timescales, the absorbed light energy is converted to heat or emitted as light instead of driving the desired surface redox reactions. This drastically reduces the number of available charge carriers, lowering the overall quantum yield and photocatalytic performance [12].

Q2: My photocatalyst absorbs visible light well but shows very low activity. Could recombination be the issue? Yes, this is a common symptom. A narrow bandgap material absorbs visible light well, generating abundant charge carriers. However, these materials often suffer from rapid charge recombination and may have insufficient redox potential. Strategies like constructing heterojunctions can help separate charges and improve efficiency despite the narrow bandgap [12].

Q3: What is "cage escape" and why is it critical for quantum yield? Cage escape is the process where the primary quenching products—the reduced photocatalyst and the oxidized donor—diffuse away from the solvent cage they are embedded in after photoinduced electron transfer. Successful cage escape prevents a spontaneous, unproductive thermal reverse electron transfer within the cage. The cage escape quantum yield (ФCE) directly governs the number of charge carriers available for onward reaction and is a decisive factor in determining the overall reaction rate and quantum yield [13].

Q4: I am using a noble metal-modified photocatalyst. How does this help reduce recombination? Loading noble metals (e.g., Pt) on a photocatalyst surface creates a Schottky barrier at the metal-semiconductor interface. This junction acts as an efficient electron trap, capturing photogenerated electrons from the semiconductor. This spatial separation significantly delays the recombination of electrons and holes, increasing their lifetime and the probability they will participate in surface reactions [5].

Q5: How can I experimentally confirm that my material modification has successfully reduced charge recombination? Several characterization techniques can provide evidence:

- Photoluminescence (PL) Spectroscopy: A decrease in PL intensity indicates a lower rate of radiative electron-hole recombination.

- Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): A smaller arc radius in the Nyquist plot suggests lower charge transfer resistance and more efficient charge separation.

- Transient Absorption Spectroscopy: Allows direct tracking of charge carrier lifetimes. For example, one study confirmed reduced recombination in a ZIF-11/g-C3N4 composite using both PL and EIS analyses [11].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Problems

Problem: Low quantum yield despite using an efficient photocatalyst system.

- Potential Cause: Low cage escape yield. The photocatalyst itself may govern the achievable magnitude of ФCE by dictating the rate of unwanted charge recombination within the solvent cage [13].

- Solution: Consider switching the photocatalyst. For instance, a study found that the cage escape quantum yields (ФCE) for a [Ru(bpz)3]2+-based system were substantially higher than for a [Cr(dqp)2]3+-based system across a range of electron donors, leading to better performance [13].

Problem: Poor photocatalytic performance in a composite photocatalyst.

- Potential Cause: Incorrect charge transfer mechanism (e.g., Type-II heterojunction) which may still involve some Coulombic attraction between separated charges, leading to potential recombination.

- Solution: Design a direct Z-scheme or S-scheme heterojunction. These mechanisms not only achieve spatial charge separation but also preserve the strongest redox abilities of the system, often leading to higher activity. The Z-scheme in a ZIF-11/g-C3N4 composite effectively reduced recombination, as confirmed by characterization [11].

Problem: Rapid deactivation of the photocatalyst over multiple cycles.

- Potential Cause: Structural instability or the recombination centers acting as degradation sites over time.

- Solution: Focus on creating stable defect structures. For example, a defect-engineered La2TiO5 catalyst (LTO-400) demonstrated good cycle stability alongside its high nitrogen fixation rate, indicating that the introduced defects were stable and did not promote deactivation [4].

Quantitative Data on Recombination Reduction Strategies

The following table summarizes quantitative data from recent studies on different strategies to suppress electron-hole recombination.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Recombination Suppression Strategies

| Strategy | Photocatalyst System | Key Performance Metric | Reported Improvement / Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Defect Engineering | Laâ‚‚TiOâ‚… with oxygen vacancies (LTO-400) | Nitrogen Fixation Rate | 158.13 μmol·gâ»Â¹Â·hâ»Â¹; Defects inhibited charge recombination and improved visible light absorption. [4] | [4] |

| Z-Scheme Heterojunction | ZIF-11/g-C₃N₄ | Methylene Blue Degradation | 72.7% degradation in 60 min; PL and EIS confirmed reduced electron/hole recombination. [11] | [11] |

| Cage Escape Engineering | [Ru(bpz)₃]²⺠with TAA-OMe donor | Cage Escape Quantum Yield (ФCE) | ФCE = 58%; A higher ФCE directly correlated with faster product formation rates in benchmark reactions. [13] | [13] |

| S-Scheme Heterojunction | (Concept from review) | Overall System Capability | Resolves trade-off between light absorption & redox potential; enables both broad absorption and strong redox power for high STH efficiency. [12] | [12] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Techniques

Protocol 1: Constructing a Z-Scheme Heterojunction Photocatalyst

This protocol is adapted from the synthesis of ZIF-11/g-C₃N₄ nanocomposites [11].

Objective: To fabricate a Z-scheme heterojunction that minimizes electron-hole recombination while preserving strong redox ability.

Materials:

- Precursors: Zinc acetate dihydrate (Câ‚„Hâ‚â‚€O₆Zn·2Hâ‚‚O), Benzimidazole (C₇H₆Nâ‚‚), Urea (CHâ‚„Nâ‚‚O).

- Solvents: Methanol (CH₃OH), Toluene (C₆H₅CH₃).

- Other Chemicals: Ammonium hydroxide (NHâ‚„OH).

Procedure:

- Synthesis of g-C₃N₄: Place 16 g of urea in a covered alumina crucible. Heat in a muffle furnace to 550 °C at a ramp rate of 2 °C/min and hold for 4 hours. After cooling to room temperature, collect the resulting light-yellow g-C₃N₄ powder.

- Preparation of Solution A: Disperse a specific amount (e.g., 0.3 g) of the synthesized g-C₃N₄ in 6.1 mL of methanol. Stir for 150 minutes to achieve a homogeneous dispersion.

- Preparation of Solution B: In a separate container, dissolve 0.12 g of benzimidazole in a mixture of 6.1 mL methanol, 5.3 mL toluene, and 0.8 mL ammonia. Subsequently, add 0.11 g of zinc acetate to this solution and stir until dissolved.

- Combination and Reaction: Slowly add Solution A to Solution B under continuous stirring. Allow the reaction to proceed at room temperature for 3 hours with constant stirring.

- Product Isolation: Separate the solid product by filtration or centrifugation. Wash the solid three times with methanol to remove any residual toluene or unreacted precursors.

- Drying: Dry the final product (ZIF-11/g-C₃N₄) at room temperature for 3 hours.

Characterization to Verify Reduced Recombination:

- Use Photoluminescence (PL) Spectroscopy. A significant decrease in the PL emission intensity of the composite compared to pure g-C₃N₄ indicates suppressed radiative recombination.

- Perform Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS). A smaller arc radius in the Nyquist plot for the composite suggests lower charge transfer resistance and more efficient charge separation [11].

Protocol 2: Introducing Oxygen Vacancies via Thermal Reduction

This protocol is based on the defect density modulation of Laâ‚‚TiOâ‚… (LTO) [4].

Objective: To create oxygen vacancies in a metal oxide photocatalyst, which can act as electron traps and active sites, thereby reducing bulk recombination.

Materials:

- Precursor: Pre-synthesized Laâ‚‚TiOâ‚… (LTO) nanoparticles (e.g., synthesized via a sol-gel method).

- Equipment: Tube furnace, controlled atmosphere gas supply (e.g., 5% Hâ‚‚/Ar mixture or vacuum).

Procedure:

- Preparation: Place the as-synthesized LTO powder in a ceramic boat.

- Reduction Process: Insert the boat into a tube furnace. Flush the tube with an inert gas (e.g., Argon) to remove air.

- Thermal Treatment: Heat the furnace to a controlled reduction temperature (e.g., 400 °C) under a reducing atmosphere (e.g., a flow of 5% H₂/Ar mixture). Maintain the temperature for a set duration (e.g., 1-2 hours).

- Cooling: After the reduction time, allow the furnace to cool to room temperature under the same gas flow. The resulting sample can be labeled as R-LTO (e.g., LTO-400 for reduction at 400°C).

Characterization of Defects:

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Analyze the O 1s spectrum. A shoulder or peak at a lower binding energy can confirm the presence of oxygen vacancies [4].

- UV-Vis Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy (DRS): Measure the absorption spectrum. An enhanced absorption tail extending into the visible region (red-shift) indicates the successful introduction of defect levels within the bandgap [4].

Visualization of Mechanisms and Workflows

Z-Scheme Charge Transfer Mechanism

Diagram Title: Z-Scheme charge transfer and internal recombination

Cage Escape and Recombination Pathways

Diagram Title: Cage escape versus recombination in photoredox catalysis

Experimental Workflow for Photocatalyst Synthesis

Diagram Title: Photocatalyst development and characterization workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Their Functions in Recombination Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Characteristics & Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| g-C₃N₄ (Graphitic Carbon Nitride) | Metal-free semiconductor; base component in Z-scheme heterojunctions. | Visible light response, suitable band gap, high chemical stability. Provides a platform for constructing composites that suppress recombination. [11] |

| ZIF-11 (Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework-11) | MOF-based semiconductor; paired with g-C₃N₄ to form a heterojunction. | High surface area, unique porous structure. Acts as the second component in a Z-scheme system to facilitate directional charge transfer. [11] |

| Laâ‚‚TiOâ‚… (LTO) Precursors | Perovskite oxide photocatalyst for defect engineering studies. | Typical perovskite structure, wide bandgap. Serves as a model material for introducing oxygen vacancies to trap electrons and reduce recombination. [4] |

| [Ru(bpz)₃]²⺠Complex | Molecular photocatalyst for fundamental cage escape studies. | High cage escape quantum yield (ФCE). Used as a benchmark to study and quantify the role of cage escape in minimizing geminate recombination. [13] |

| Triarylamine (TAA) Donors | Electron donors in photoredox catalysis quenching experiments. | Reversible electron transfer. Used to quantitatively measure cage escape yields and study the parameters affecting charge separation efficiency. [13] |

| Aphos | Aphos, CAS:74548-80-4, MF:C16H14Cl3O5P, MW:423.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| AT-61 | AT-61, CAS:300669-68-5, MF:C21H21ClN2O2, MW:368.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

In photocatalyst research, the rapid recombination of photogenerated electron-hole pairs is a primary factor limiting efficiency. Advanced characterization techniques are critical for directly observing and quantifying these recombination dynamics to develop effective suppression strategies. This guide details the application of Photoluminescence (PL), Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (TRPL), and Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) for troubleshooting recombination issues, providing researchers with practical methodologies to diagnose loss mechanisms and validate material optimizations.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can I quickly determine if my new photocatalyst material has a high electron-hole recombination rate?

A1: A preliminary steady-state PL spectrum is the most direct tool for an initial assessment. A high-intensity PL peak typically indicates strong radiative recombination, which, while easy to measure, often competes with non-radiative pathways. In many photocatalyst systems, the goal is to minimize overall PL intensity, as this suggests that non-radiative pathways (like charge separation and transport) are being favored over direct band-to-band recombination. For example, in the development of a ZIF-11/g-C3N4 Z-scheme heterostructure, a significant reduction in PL intensity was a key indicator of suppressed charge recombination [11].

Q2: My steady-state PL shows low intensity, suggesting low recombination. Why is my photocatalytic performance still poor?

A2: Low PL intensity can be misleading. It can indicate either successful charge separation or the presence of numerous defects or traps that quench luminescence through fast, non-radiative pathways. To distinguish between these scenarios, you need Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (TRPL). TRPL measures the photoluminescence decay lifetime after pulsed excitation. A short lifetime, even with low PL intensity, points to defect-dominated non-radiative recombination, which is detrimental to performance. A longer lifetime is generally indicative of high material quality and more efficient charge carrier utilization [14].

Q3: What does a multi-exponential decay curve in my TRPL data mean, and how should I interpret it?

A3: A multi-exponential decay is common in complex materials and reveals the presence of multiple, concurrent recombination pathways. When fitting your decay curve with multiple lifetimes (e.g., Ï„1, Ï„2, Ï„3), each component can be attributed to a specific process:

- Ï„1 (Fast component): Often related to non-radiative recombination at surface or bulk defects.

- Ï„2 (Medium component): Can be associated with trap-assisted recombination.

- Ï„3 (Slow component): Typically attributed to radiative band-to-band recombination.

The amplitude-weighted average lifetime can provide a single metric for comparing different samples. The presence of a strong slow component after a material modification (e.g., passivation or heterojunction formation) is a positive sign of suppressed non-radiative recombination [14].

Q4: How does EIS complement the information I get from PL and TRPL?

A4: While PL and TRPL directly probe the recombination kinetics of photoexcited charges, EIS investigates the charge transfer resistance and conductivity within the material or at its interface. PL/TRPL tells you about the fate of electrons and holes, whereas EIS reveals how easily the separated charges can move. A smaller semicircle in a Nyquist plot under illumination indicates a lower charge transfer resistance, which is often a consequence of reduced recombination and more efficient charge separation, as demonstrated in Z-scheme heterostructures [11].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Diagnosing Electron-Hole Recombination with Steady-State PL

Problem: Unclear how to interpret steady-state PL spectra to identify recombination types.

Solution: Follow this diagnostic workflow to correlate spectral features with material properties.

Guide: Resolving Common TRPL Experimental Challenges

Problem: Poor signal-to-noise ratio, instrument response function (IRF) broadening, or difficulty interpreting decay curves.

Solution: Address these common issues with the following corrective actions.

| Challenge | Root Cause | Corrective Action & Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Weak luminescence, low photon count, or detector inefficiency. | Increase laser power (avoiding sample damage), use a higher repetition rate, employ a detector with higher quantum efficiency (e.g., SNSPD), and extend data acquisition time. |

| Broadened IRF | High timing jitter from laser, detector, or electronics [14]. | Use a picosecond or femtosecond pulsed laser; ensure detectors (e.g., SPAD) and timing electronics (e.g., Time Tagger with <2 ps jitter) are optimized for low jitter [14]. |

| Multi-Exponential Decay Fitting Issues | Overfitting, incorrect model selection. | Validate the need for a multi-exponential fit by comparing the quality of fit (χ²) for different models. Correlate lifetime components with physical processes based on sample treatment. |

Guide: Integrating PL, TRPL, and EIS for a Comprehensive View

Problem: Isolated data from one technique provides an incomplete picture of recombination and charge transfer.

Solution: Strategically combine all three techniques to dissect the photocatalyst's workflow.

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Protocol: Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (TRPL) Measurement

Objective: To measure the time decay of photoluminescence and extract carrier recombination lifetimes.

Materials and Setup:

- Pulsed Laser: Picosecond or femtosecond laser source (e.g., Ti:Sapphire). Wavelength selected based on material bandgap [14] [15].

- Detection System: Single-photon avalanche diode (SPAD) or photomultiplier tube (PMT).

- Timing Electronics: Time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) module or a high-resolution time tagger (e.g., with picosecond jitter) [14].

- Optics: Beam splitter (to generate trigger), focusing lenses, collection objective, and spectral filters (to isolate emission from laser scatter).

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Alignment: Align the laser beam to focus on the sample. Ensure the collection path is optimized to gather the maximum emitted light onto the detector.

- Spectral Filtering: Place a long-pass or band-pass filter in the collection path to completely block the scattered laser light while transmitting the photoluminescence.

- Trigger Setup: Use a fast photodiode or the laser's sync output to generate a "start" trigger signal for each laser pulse.

- Photon Counting: For each detected photon ("stop" signal), the timing electronics record the time difference between the "start" and "stop" [14]. Ensure the count rate is kept below 1-5% of the laser repetition rate to avoid pulse pile-up distortion.

- Data Acquisition: Accumulate photons over several minutes to build a histogram of arrival times, which represents the PL decay curve.

- Lifetime Fitting: Fit the decay curve with appropriate exponential models (e.g., single, bi-exponential) using software, extracting the lifetime components (Ï„) and their amplitudes (A).

- Equation: ( I(t) = \sum Ai \cdot \exp(-t/\taui) )

- The average lifetime can be calculated as ( \langle \tau \rangle = \frac{\sum Ai \taui^2}{\sum Ai \taui} ).

Detailed Protocol: Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) for Photocatalysts

Objective: To characterize the charge transfer resistance and semiconductor properties of the photocatalyst.

Materials and Setup:

- Potentiostat/Galvanostat with EIS capability.

- Three-Electrode Electrochemical Cell:

- Working Electrode: Photocatalyst material deposited on a conductive substrate (e.g., FTO, ITO).

- Counter Electrode: Platinum wire or mesh.

- Reference Electrode: Ag/AgCl or Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE).

- Electrolyte: Aqueous solution (e.g., 0.5 M Naâ‚‚SOâ‚„) or other relevant supporting electrolyte.

- Light Source: LED or laser matching the catalyst's absorption profile.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Electrode Preparation: Disperse the photocatalyst powder in a solvent with a binder (e.g., Nafion) and drop-cast onto the conductive substrate. Dry thoroughly.

- Cell Assembly: Immerse the three electrodes in the electrolyte, ensuring no air bubbles are trapped.

- Setup Parameters:

- Set the DC bias potential, often the open circuit potential (OCP).

- Set the AC voltage amplitude (typically 5-10 mV RMS).

- Define the frequency range (e.g., from 100 kHz to 0.1 Hz).

- Measurement:

- First, measure the impedance in the dark.

- Then, illuminate the working electrode with the light source and measure the impedance under steady-state illumination.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot the data as Nyquist plots (-Z'' vs Z').

- Fit the data to an equivalent circuit model (e.g., a modified Randles circuit with a constant phase element). The key parameter is the charge transfer resistance (Râ‚â‚œ), which should decrease under illumination for a good photocatalyst [11].

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

Table: Key materials for characterizing recombination dynamics in photocatalyst systems.

| Material / Reagent | Function / Role in Characterization | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Pulsed Laser System (e.g., Ti:Sapphire) | Provides ultrafast excitation pulses for TRPL; wavelength tunability is key for probing different materials [14] [15]. | Used in trARPES and TRPL for pump-probe experiments with femtosecond resolution [15]. |

| Single-Photon Avalanche Diode (SPAD) | High-sensitivity detector for time-resolved single-photon counting in TRPL; offers low jitter [14]. | Critical for high-time-resolution TRPL setups to minimize instrument response function [14]. |

| Graphitic Carbon Nitride (g-C₃N₄) | A metal-free polymer semiconductor used as a base photocatalyst or component in Z-scheme heterostructures [11]. | Combined with ZIF-11 to form a Z-scheme heterojunction, reducing recombination as confirmed by PL and EIS [11]. |

| Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks (ZIFs) | Provides a porous crystalline structure to form composite heterostructures, facilitating charge separation [11]. | ZIF-11 was composited with g-C₃N₄, leading to a Z-scheme system with reduced electron-hole recombination [11]. |

| Supporting Electrolyte (e.g., Naâ‚‚SOâ‚„) | Provides ionic conductivity in an electrochemical cell for EIS measurements, without participating in reactions. | Used in standard three-electrode setups to measure the charge transfer resistance of photocatalysts. |

Engineering Solutions: Proven Strategies to Minimize Charge Recombination

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary function of a heterojunction in photocatalysis? A1: The primary function is to enhance the spatial separation of photogenerated electron-hole pairs, thereby suppressing their recombination and increasing the efficiency of photocatalytic reactions. This is achieved by creating an interface between two semiconductors with different electronic structures, which facilitates the directional movement of charge carriers across the interface [16] [17].

Q2: Why are conventional Type-I and Type-II heterojunctions sometimes insufficient? A2: While conventional heterojunctions improve charge separation, they often do so at the expense of redox potential. In a typical Type-II system, electrons accumulate on the semiconductor with the lower conduction band (less negative potential), and holes accumulate on the semiconductor with the lower valence band (less positive potential). This spatial separation reduces recombination but also weakens the reducing power of the electrons and the oxidizing power of the holes, impairing the driving force for demanding reactions like water splitting and CO2 reduction [16].

Q3: How do S-scheme heterojunctions overcome the limitations of Type-II systems? A3: S-scheme heterojunctions are designed to simultaneously achieve efficient charge separation and preserve strong redox potentials. In an S-scheme system, useless electrons and holes recombine at the interface, while the most useful electrons (those with the highest reduction potential) remain in one semiconductor and the most useful holes (those with the highest oxidation potential) remain in the other. This maximizes the available energy for catalytic reactions [18].

Q4: What experimental evidence confirms an S-scheme charge transfer mechanism? A4: Multiple characterization techniques can provide evidence:

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Can detect shifts in the binding energy of core elements upon heterojunction formation, indicating electron transfer between semiconductors and the formation of an internal electric field (IEF) [18].

- Radical Scavenging Experiments: Can identify which reactive species (e.g., •OH, •O₂–, hâº) are active in the system, helping to trace the origin of electrons and holes [18].

- Electron Spin Resonance (ESR): Can directly detect and track the generation of radical species, providing further proof of the charge transfer pathway.

Q5: What is the role of the Internal Electric Field (IEF) in heterojunctions? A5: The IEF is a critical driving force for charge separation in heterojunctions, particularly in S-scheme and advanced Type-II systems. It forms at the interface due to the difference in Fermi levels (Ef) between the two semiconductors. Electrons flow from the semiconductor with the higher Ef to the one with the lower Ef until their Fermi levels equilibrate. This process creates a built-in electric field that promotes the desired migration of photoinduced carriers and inhibits their recombination [18] [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Charge Separation Despite Heterojunction Formation

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Incorrect Band Alignment. The selected semiconductors do not have the required straddling of band edges to facilitate the intended charge transfer (Type-II, Z-scheme, or S-scheme).

- Cause 2: Low Quality of the Interface. A poor physical interface between the two semiconductors can hinder electron transfer.

- Cause 3: High Defect Density. Defects at the interface or within the semiconductors can act as recombination centers.

- Solution: Control synthesis conditions to minimize defects. Post-synthesis annealing can sometimes help, but the temperature must be optimized to avoid damaging the heterojunction structure.

Problem: Low Quantum Efficiency and Catalytic Performance

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Severe Charge Recombination.

- Solution: Introduce a cocatalyst (e.g., Pt for reduction, CoOx for oxidation) onto the heterojunction surface. The cocatalyst provides active sites and can further extract specific charge carriers, reducing recombination [16].

- Cause 2: Inefficient Utilization of Visible Light.

- Solution: Combine a wide-bandgap semiconductor (e.g., CeOâ‚‚, TiOâ‚‚) with a narrow-bandgap, visible-light-responsive material (e.g., CuInSâ‚‚). The narrow-bandgap semiconductor acts as a sensitizer, expanding the light absorption range of the composite [18].

- Cause 3: Unoptimized Mass Ratio of Components.

Problem: Photocorrosion or Instability of the Heterojunction

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Oxidation or Reduction of the Photocatalyst Itself. This is common in sulfide-based materials or those susceptible to reactions with photogenerated holes.

- Solution: For S-scheme systems, the recombination of less useful charges at the interface can protect the individual semiconductors from corrosion. Alternatively, consider using more chemically stable metal oxides as one component of the heterojunction or conducting reactions under controlled conditions [18].

Quantitative Performance Data

The following table summarizes performance metrics for selected heterojunction systems as reported in the literature, highlighting their efficacy in various applications.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Heterojunction Photocatalysts

| Heterojunction System | Type | Application | Performance Metric | Reported Efficiency | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CuInSâ‚‚/CeOâ‚‚ | S-scheme | Ciprofloxacin (CIP) Degradation | Degradation after specified time | ~90% (vs. 60% for CeOâ‚‚, 12% for CuInSâ‚‚) | [18] |

| Ag₂CO₃/Bi₂WO₆ (AB-9) | Type-II–II | Levofloxacin (LEV) Degradation | Degradation after specified time | 85.4% (1.38x Bi₂WO₆, 1.39x Ag₂CO₃) | [19] |

| BiOI/Bi₂WO₆ | Type-II | Methylene Blue (MB) Degradation | Degradation after specified time | 99% (30% improvement over Bi₂WO₆) | [19] |

| Bi₂WO₆/BiOCl | Type-II | Rhodamine B Degradation | Degradation after specified time | 93.3% (33% improvement over Bi₂WO₆) | [19] |

| g-Câ‚â‚‚N₇H₃ (predicted) | - | Water Splitting | Band Gap (HSE06 functional) | 3.24 eV | [20] |

Table 2: Key Redox Potentials for Photocatalytic Reactions (vs. NHE)

| Reaction | Equation | Redox Potential (V) |

|---|---|---|

| Water Oxidation | 2H₂O + 4h⺠→ O₂ + 4H⺠| +1.23 |

| Water Reduction | 2H⺠+ 2e⻠→ H₂ | 0.00 |

| Hydrogen Peroxide Formation | O₂ + 2H⺠+ 2e⻠→ H₂O₂ | +0.68 |

| Superoxide Radical Formation | O₂ + e⻠→ •O₂⻠| -0.33 |

| Hydroxyl Radical Formation | OH⻠+ h⺠→ •OH | +1.99 |

| Carbon Dioxide Reduction to CO | CO₂ + 2H⺠+ 2e⻠→ CO + H₂O | -0.53 |

| Carbon Dioxide Reduction to CH₃OH | CO₂ + 6H⺠+ 6e⻠→ CH₃OH + H₂O | -0.38 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Synthesis of an S-Scheme Heterojunction (CuInSâ‚‚/CeOâ‚‚)

This protocol is adapted from the solvothermal synthesis of CuInSâ‚‚/CeOâ‚‚ for antibiotic degradation [18].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Cerium Precursor: Cerium nitrate hexahydrate (Ce(NO₃)₃·3H₂O)

- Structure-Directing Agent: Sodium hydroxide (NaOH)

- Copper Source: Copper chloride (CuClâ‚‚)

- Indium Source: Indium chloride (InCl₃)

- Sulfur Source: Thioacetamide (Câ‚‚Hâ‚…NS)

- Solvent: N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF)

- Target Pollutant: Ciprofloxacin (CIP)

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Synthesis of CeO₂ Nanorods: a. Dissolve 1 g of Ce(NO₃)₃·3H₂O in 50 mL of deionized water. b. Add this solution to a stirred solution of 9.2 g of NaOH in 100 mL of deionized water. c. Transfer the mixture to a Teflon-lined autoclave and maintain at 100 °C for 24 h. d. Wash the resulting product thoroughly with deionized water and dry at 70 °C for 24 h.

- Synthesis of CuInS₂/CeO₂ Heterojunction: a. Disperse 0.2 g of the as-synthesized CeO₂ in DMF and stir for 15 minutes. b. Add stoichiometric amounts of copper chloride (1 mmol), indium chloride (1 mmol), and thioacetamide (2 mmol) to the suspension. Stir for an additional 30 minutes. c. Transfer the final mixture to an autoclave and heat at 180 °C for 12 h. d. After the reaction, wash the product thoroughly with deionized water and dry overnight at 70 °C. e. Label the heterojunction based on the mole ratio of CuInS₂ to CeO₂ (e.g., 1.0CuInS₂/CeO₂ for a 10% mole ratio).

Characterization and Validation:

- Use XRD to confirm the crystal structure and successful formation of the composite.

- Use UV-Vis spectroscopy to analyze the light absorption properties.

- Use XPS to investigate electron transfer and the potential formation of an internal electric field, which is key evidence for an S-scheme mechanism.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Photocatalytic Degradation Activity

This general protocol can be used to test the efficiency of synthesized heterojunctions for pollutant degradation [18] [19].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Catalyst: The synthesized heterojunction powder.

- Target Pollutant: e.g., Ciprofloxacin (CIP), Levofloxacin (LEV), or a model dye.

- Radical Scavengers: Isopropanol (for •OH), p-benzoquinone (for •Oâ‚‚â»), EDTA (for hâº).

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Adsorption-Desorption Equilibrium: Disperse 30 mg of the photocatalyst in 50 mL of an aqueous solution of the pollutant (e.g., 5 mg/L concentration). Stir the suspension in darkness for 30 minutes.

- Photocatalytic Reaction: Illuminate the mixture using a simulated solar light source (e.g., a 100 W Xenon lamp). Position the lamp at a fixed distance (e.g., 10 cm) above the solution surface.

- Sampling: At specific time intervals (e.g., 0, 10, 20, 30, 60 min), withdraw 3 mL aliquots of the suspension.

- Analysis: Centrifuge the samples to remove catalyst particles. Analyze the clear supernatant using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer to determine the remaining concentration of the pollutant. The degradation efficiency can be calculated as: Efficiency (%) = [(C₀ - Cₜ) / C₀] × 100, where C₀ and Cₜ are the initial concentration and concentration at time t, respectively.

- Mechanism Investigation (Radical Trapping): Repeat the experiment by adding different scavengers to the reaction mixture before illumination. A significant decrease in activity upon the addition of a specific scavenger indicates the corresponding species is a primary active radical in the process.

Schematic Diagrams

Diagram 1: Charge Transfer Mechanisms in Heterojunctions

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Heterojunction Synthesis & Testing

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents for Heterojunction Photocatalyst Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Cerium Nitrate Hexahydrate | Precursor for synthesizing CeOâ‚‚, a wide-bandgap metal oxide semiconductor. | Used as a base material in CuInSâ‚‚/CeOâ‚‚ S-scheme heterojunctions [18]. |

| Bismuth Nitrate Pentahydrate | Precursor for bismuth-based semiconductors (e.g., Bi₂WO₆, BiOI). | Used in the synthesis of Bi₂WO₆ for constructing Type-II heterojunctions with Ag₂CO₃ [19]. |

| Thioacetamide | Sulfur source for the synthesis of metal sulfide semiconductors. | Used to incorporate sulfur during the solvothermal synthesis of CuInSâ‚‚ [18]. |

| Silver Nitrate | Precursor for silver-based semiconductors (e.g., Ag₂CO₃, Ag₃PO₄). | Combined with Bi₂WO₆ to form a Type-II-II heterojunction for antibiotic degradation [19]. |

| p-Benzoquinone | Scavenger of superoxide radicals (•Oâ‚‚â») in mechanism studies. | Used in radical trapping experiments to identify the role of •Oâ‚‚â» in the degradation process [19]. |

| Isopropanol (IPA) | Scavenger of hydroxyl radicals (•OH) in mechanism studies. | Used to quench •OH radicals and determine their contribution to photocatalytic activity [19]. |

| EDTA | Scavenger of photogenerated holes (hâº) in mechanism studies. | Used to confirm the involvement of holes in the oxidation reaction [19]. |

| BMH-9 | BMH-9, CAS:457937-39-2, MF:C19H27N3O2, MW:329.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| BPTU | BPTU, MF:C23H22F3N3O3, MW:445.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Hub

This section addresses common experimental challenges in defect engineering for photocatalysis, providing targeted solutions to improve research outcomes.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does my defect-engineered photocatalyst show increased light absorption but no improvement in photocatalytic activity? This typically indicates that the introduced defects, while improving light absorption, are acting as recombination centers rather than effective electron traps. To resolve this:

- Verify Defect Type and Concentration: Use techniques like Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) to confirm you have created the intended defects (e.g., oxygen vacancies) and not other detrimental defect types. Excess defect concentration can form recombination hubs.

- Check Charge Carrier Dynamics: Perform photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy or electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). A decreased PL intensity and reduced arc radius in EIS Nyquist plots for your modified sample confirm suppressed electron-hole recombination [11].

- Optimize Synthesis Conditions: Defect formation is highly sensitive to synthesis environment. For oxides like SrTiO₃, annealing under oxygen-poor conditions promotes oxygen vacancy formation, but the precise chemical potential must be controlled to avoid creating neutral or clustered vacancies that are ineffective [21].

Q2: How can I ensure that oxygen vacancies act as electron traps instead of recombination centers? The key is to prevent the in-gap states associated with vacancies from becoming deep traps. This can be achieved through defect passivation:

- Co-doping Strategy: Introduce a lower-valency dopant adjacent to the vacancy. For example, in SrTiO₃, Al³⺠doping at Tiâ´âº sites adjacent to an oxygen vacancy forms a [VO-AlTi] defect complex. This complex deactivates the deep Ti³+ trap state by breaking the Ti 3d–Ti 3d interaction across the vacancy, effectively eliminating the recombination channel [21].

- Select Dopants with No Valence d Orbitals: The absence of valence d orbitals in dopants like Al³⺠is crucial for successfully passivating the oxygen vacancy in-gap state [21].

Q3: My defect-engineered material performs well in the lab but deactivates quickly during prolonged use. How can I improve its stability? This often results from the instability or gradual healing of the defects under operational conditions.

- Stabilize Defects with a Heterostructure: Construct a Z-scheme heterojunction. In a system like UiO-66-NHâ‚‚@ZnInâ‚‚Sâ‚„, the Z-scheme mechanism effectively separates photogenerated electrons and holes, suppressing the photo-corrosion that typically degrades the catalyst (like ZnInâ‚‚Sâ‚„) [22].

- Modulate the Microenvironment: In the UiO-66-NHâ‚‚@ZnInâ‚‚Sâ‚„ example, the metal-organic framework (MOF) provides a porous structure with abundant channels. This not only facilitates mass transfer but may also help stabilize the sulfur vacancies in ZnInâ‚‚Sâ‚„, contributing to a system that demonstrated stable performance for over 200 hours [22].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Setbacks

Problem: Inconsistent photocatalytic performance between different batches of the same defect-engineered material.

- Solution: Strictly control the precursor ratios and atmospheric conditions during synthesis. For sol-gel processes, ensure precise stoichiometry and drying/calcination temperatures. Using a robust structure-searching method during computational modeling can help identify the true ground-state defect configuration, guiding more reproducible synthesis [21].

Problem: Low selectivity for the desired reaction pathway (e.g., 2-electron oxygen reduction).

- Solution: Engineer defects to control adsorption configuration. Sulfur vacancies in ZnInâ‚‚Sâ‚„ modulate Oâ‚‚ adsorption from a Yeager-type (side-on) configuration to a Pauling-type (end-on) configuration. The Pauling-type favors the formation of the *OOH intermediate and suppresses O-O bond cleavage, thereby highly selectively steering the reaction toward Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ production [22].

Quantitative Performance Data

The following table summarizes key performance metrics from recent studies, highlighting the efficacy of different defect engineering strategies.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Defect-Engineered Photocatalysts

| Material System | Defect / Engineering Strategy | Primary Application | Performance Metric | Reported Value | Key Improvement Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UiO-66-NHâ‚‚@ZnInâ‚‚Sâ‚„ (Z-scheme) [22] | Sulfur Vacancies in ZIS | Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ Production | Production Rate: 3200 µmol gâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹Selectivity: 94.3% | Promotes Pauling-type Oâ‚‚ adsorption for efficient 2e ORR; Z-scheme enhances charge separation. | |

| SrTiO₃:Al [21] | Al³⺠Doping passivating Oxygen Vacancies | Water Splitting | Quantum Efficiency: >90% | Eliminates deep trap states (Ti³+) from oxygen vacancies, drastically reducing recombination. | |

| ZIF-11/g-C₃N₄ [11] | Z-scheme Heterojunction | Dye Degradation (Methylene Blue) | Degradation Efficiency: 72.7% (in 60 min)TOC Removal: 66.5% (in 5 hr) | Z-scheme mechanism effectively separates electrons and holes, reducing recombination. | |

| Ag,CdO,ZnO/TiOâ‚‚ [23] | Ternary Doping (Schottky, Z-scheme, Type II) | Water Splitting (Hâ‚‚ Production) | High Hâ‚‚ Production Rate (departure from Arrhenius behavior) | Synergistic effects create multiple pathways for charge separation, overcoming recombination. |

Standardized Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Creating and Passivating Oxygen Vacancies in SrTiO₃ via Al Doping

This protocol is adapted from studies achieving high quantum efficiency in water splitting [21].

Objective: To synthesize Al-doped SrTiO₃ where Al³⺠ions passivate the in-gap states of oxygen vacancies, thereby suppressing charge carrier recombination.

Materials:

- Precursors: Strontium salt (e.g., Sr(NO₃)₂), Titanium precursor (e.g., Ti-isopropoxide), Aluminum precursor (e.g., Al(NO₃)₃).

- Solvent: Deionized water or ethanol.

- Flux agent: SrClâ‚‚ (for flux-assisted synthesis).

- Equipment: High-temperature muffle furnace, alumina crucibles, magnetic stirrer, drying oven.

Methodology:

- Precursor Solution Preparation: Dissolve the Sr, Ti, and Al precursors in the solvent according to the desired stoichiometric ratio (e.g., SrTiâ‚â‚‹â‚“Alâ‚“O₃). Stir vigorously for 2 hours to obtain a homogeneous solution.

- Drying: Evaporate the solvent slowly at 80°C to form a dry gel.

- Calcination (Flux Method):

- Mix the dried precursor powder with SrClâ‚‚ flux in a defined weight ratio.

- Place the mixture in an alumina crucible and calcine in a muffle furnace at 1423 K (1150°C) for 4-6 hours under an air atmosphere. The high temperature and flux promote crystal growth and defect formation.

- Critical Step: The "oxygen-poor" condition during crystal growth is intrinsic to this high-temperature process in a closed crucible, favoring the formation of oxygen vacancies [21].

- Post-processing: After cooling to room temperature, wash the resulting product repeatedly with deionized water to completely remove the SrCl₂ flux. Dry the final powder at 100°C overnight.

Validation Techniques:

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): To confirm the presence of Al and analyze the Ti³+/Tiâ´+ ratio. A successful passivation will show a suppression of Ti³+ signals [21].

- Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR): To detect and quantify paramagnetic defect states like unpassivated oxygen vacancies before and after doping.

- Photoluminescence (PL) Spectroscopy: A significant quenching of PL emission in the Al-doped sample indicates a reduction in electron-hole recombination.

Protocol 2: Constructing a Z-scheme Heterojunction with Defect-Modulated Surface (UiO-66-NHâ‚‚@ZIS)

This protocol is based on a system for highly selective Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ production [22].

Objective: To in-situ grow sulfur-deficient ZnInâ‚‚Sâ‚„ (ZIS) nanosheets on UiO-66-NHâ‚‚ MOF crystals to form a Z-scheme heterojunction where sulfur vacancies optimize Oâ‚‚ adsorption.

Materials:

- UiO-66-NHâ‚‚ crystals (synthesized separately via solvothermal method).

- Precursors: Zinc acetate (Zn(CH₃COO)₂), Indium chloride (InCl₃), Thioacetamide (C₂H₅NS).

- Solvents: Methanol, Dimethylformamide (DMF).

Methodology:

- Dispersion of MOF: Disperse a known quantity of pre-synthesized UiO-66-NHâ‚‚ crystals in methanol using ultrasonication for 30 minutes.

- In-situ Growth of ZIS:

- Add Zinc acetate and Indium chloride to the above dispersion. Stir for 30 minutes to allow adsorption of metal ions onto the MOF surface.

- Add a controlled amount of Thioacetamide (the sulfur source) to the mixture.

- Heat the reaction mixture at 60-70°C for several hours under continuous stirring. The controlled decomposition of thioacetamide and the limited sulfur source lead to the in-situ growth of ZIS nanosheets with inherent sulfur vacancies on the UiO-66-NH₂ surface [22].

- Isolation and Washing: Collect the solid product by centrifugation. Wash thoroughly with methanol and ethanol to remove unreacted precursors.

- Drying: Dry the final U6N@ZIS composite at 60°C in a vacuum oven.

Validation Techniques:

- High-Angle Annular Dark-Field STEM (HAADF-STEM) and EDS Mapping: To confirm the core-shell structure and uniform distribution of elements.

- X-ray Absorption Fine Structure (XAFS): Analyze the Zn K-edge to detect the negative shift and reduced coordination number, providing direct evidence for sulfur vacancies [22].

- Photocatalytic Test: Evaluate Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ production in pure water under visible light. A high production rate and selectivity confirm the successful synergy between the Z-scheme charge transfer and defect-modulated surface reaction.

Mechanism and Workflow Visualizations

Defect Passivation Resolves Recombination

Z-Scheme Heterojunction with Defect Engineering Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Defect-Engineered Photocatalyst Synthesis

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Strontium Nitrate (Sr(NO₃)₂) | Sr precursor for perovskite oxides (e.g., SrTiO₃). | Synthesis of SrTiO₃ photocatalyst [21]. |

| Titanium Isopropoxide (Câ‚â‚‚H₂₈Oâ‚„Ti) | Ti precursor for TiOâ‚‚ and titanate-based photocatalysts. | Synthesis of TiOâ‚‚ and SrTiO₃ [23] [21]. |

| Aluminum Nitrate (Al(NO₃)₃·9H₂O) | Al³⺠dopant source for passivating oxygen vacancies. | Passivation of deep traps in SrTiO₃ [21]. |

| Zinc Acetate (Zn(CH₃COO)₂) | Zn²⺠precursor for chalcogenide semiconductors. | Synthesis of ZnIn₂S₄ and ZnO-based photocatalysts [22] [23]. |

| Thioacetamide (Câ‚‚Hâ‚…NS) | Sulfur source. Controlled use can introduce sulfur vacancies. | Creating S-deficient ZnInâ‚‚Sâ‚„ [22]. |

| Zirconium Chloride (ZrClâ‚„) | Metal cluster precursor for Zr-based MOFs (e.g., UiO-66). | Synthesis of UiO-66-NHâ‚‚ MOF support [22]. |

| 2-Aminoterephthalic Acid | Organic linker for constructing functionalized MOFs (UiO-66-NHâ‚‚). | Provides NHâ‚‚ groups for heterojunction formation in UiO-66-NHâ‚‚ [22]. |

| B 746 | B 746, CAS:103051-26-9, MF:C26H20Cl2N4, MW:459.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| iMAC2 | iMAC2, CAS:335166-36-4, MF:C19H20Br2FN3, MW:469.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Morphological Control and Nanostructuring for Shortened Charge Migration Paths

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQ on Nanostructuring for Charge Carrier Management

This guide addresses common challenges researchers face when designing photocatalysts with optimized charge carrier pathways to reduce electron-hole recombination.

FAQ 1: Why does my synthesized hollow nanostructure show lower photocatalytic activity than expected, despite a high surface area?

- Potential Cause: Incomplete or collapsed hollow structures can hinder mass transport and charge carrier migration, while poor interfacial contact in composite materials can lead to high charge transfer resistance.

- Solution:

- Verify the integrity of the hollow structure using techniques like TEM and SEM. A successful hollow shell nanostructure should show a distinct void space and a well-defined shell [24].

- For composite hollow structures (e.g., MOF-derived materials), ensure a coherent interface between components. Techniques like HRTEM can confirm this. In the TiOâ‚‚@ZrBTB hollow shell nanostructure, the in situ self-sacrificial template method was key to forming a well-integrated heterostructure with a well-defined hollow morphology [24].

- Use a structure-directing agent, like Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) in the synthesis of TiOâ‚‚@ZrBTB, to control the growth and etching processes for a uniform hollow architecture [24].

FAQ 2: My heterojunction photocatalyst absorbs light but shows poor charge separation. What is wrong?

- Potential Cause: The problem often lies in the band alignment between the semiconductors. A simple physical mixture without intimate contact or an incorrect band alignment (e.g., Type-I) does not create the internal electric field needed for effective charge separation.

- Solution:

- Design an S-scheme or Z-scheme heterojunction. These systems not only enhance charge separation but also preserve the strongest redox abilities of the constituent semiconductors [25] [26]. For instance, the GaP-TiOâ‚‚ S-scheme heterojunction was confirmed to significantly enhance carrier separation and boost hydrogen production [27].

- Perform characterization like XPS to verify the presence of an internal electric field and the desired charge migration pathway [28] [25].

- Ensure synthesis methods (e.g., in-situ growth, calcination) create close interfacial contact rather than just mixing pre-formed components.

FAQ 3: The charge carrier lifetime in my one-dimensional (1D) nanofiber photocatalyst is still insufficient. How can I further improve it?

- Potential Cause: While 1D structures provide a direct path for electron travel, recombination can still occur rapidly if electron extraction and hole scavenging are not simultaneous.

- Solution:

- Implement a multichannel charge transfer system. This involves integrating multiple functional components into a single structure. A proven design is a Z-scheme heterostructure (e.g., TiO₂/WO₃) decorated with dual cocatalysts.

- Use a noble metal with low overpotential, like Platinum (Pt), as an electron collector to facilitate the reduction reaction.

- Simultaneously, use a semiconductor like Tungsten Trioxide (WO₃) as a hole collector. This creates multiple, parallel pathways for electrons and holes, drastically reducing their chance of recombination and directly evidenced by improved photocurrent and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) results [29].

FAQ 4: How can I accurately confirm the charge transfer mechanism in my novel S-scheme homojunction?

- Potential Cause: Relying solely on indirect performance metrics is insufficient; direct evidence of the charge transfer pathway is needed.

- Solution:

- Use in-situ spectroscopic techniques to track electron flow under actual working conditions.

- A highly effective method is to deposit bimetallic cocatalysts (e.g., Pt and Au oxide) as redox probes on different components of the homojunction. Subsequent analysis with in-situ XPS can track electron transfer between the constituents (e.g., from C₃N₅ to C₃N₄), providing direct verification of the S-scheme mechanism [28].

- Femtosecond transient absorption spectroscopy (fs-TAS) can further provide deep insights into the ultrafast charge transfer dynamics [28].

Performance Data of Nanostructured Photocatalysts

The following table summarizes quantitative data from recent studies on various nanostructuring strategies for improving charge migration.

Table 1: Performance of Photocatalysts with Engineered Charge Migration Paths

| Material System | Nanostructure / Strategy | Application | Key Performance Metric | Reference / Model System |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C₃Nâ‚…/C₃Nâ‚„ | Polymeric S-scheme Homojunction | Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ Production | 8.78 mmol gâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹ (visible light) | [28] |

| TiOâ‚‚@ZrBTB | Hollow Shell Nanostructure | Tetracycline Degradation | Enhanced degradation rate vs. precursors | [24] |

| GaP-TiOâ‚‚ | S-scheme Heterojunction | Hâ‚‚ Production | 12-fold enhancement vs. pristine catalyst | [27] |

| Au/Pt/WO₃/TiO₂ | 1D Nanofibers, Z-scheme, Multichannel | H₂ Evolution | Greatly enhanced rate vs. single components | [29] |

| MOFs (General) | Multiscale Structural Regulation | Various (Energy/Environment) | Enhanced efficiency via synergistic structural effects | [30] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Synthesis of a Hollow Shell Nanostructure via In Situ Self-Sacrificial Template

This protocol is adapted from the synthesis of TiOâ‚‚@ZrBTB for photocatalytic degradation [24].

- Objective: To fabricate a hollow shell heterostructure that shortens charge migration distances and provides separate reaction zones.

- Materials:

- Precursor MOF (e.g., NHâ‚‚-MIL-125(Ti))

- Zirconium-based salt (e.g., ZrClâ‚„)

- Organic linker (e.g., H₃BTB - 1,3,5-Tris(4-carboxyphenyl)benzene)

- Structure-directing agent (e.g., PVP - Polyvinylpyrrolidone)

- Solvents: Dimethylformamide (DMF), Methanol

- Procedure:

- Synthesize the sacrificial template: First, prepare NH₂-MIL-125(Ti) crystals using a solvothermal method (e.g., 150°C for 8 hours) [24].

- Pretreatment: Disperse the pre-formed NHâ‚‚-MIL-125(Ti) in a solution containing PVP to modify its surface [24].

- In-situ growth and etching: Combine the PVP-pretreated precursor with the ZrBTB synthesis reagents (Zr salt and H₃BTB linker) in a binary solvent system (DMF/Methanol). Transfer the mixture to a Teflon-lined autoclave.

- Hydrothermal reaction: Maintain the reactor at the required temperature (e.g., 150°C). The reaction time is critical:

- A shorter duration (e.g., 12 hours) may yield a core-shell intermediate (NHâ‚‚-MIL-125(Ti)@ZrBTB).

- Extending the time (e.g., 48 hours) allows the acidic conditions and hydrothermal environment to in-situ etch and convert the NHâ‚‚-MIL-125(Ti) core, ultimately forming the hollow-shell TiOâ‚‚@ZrBTB nanostructure [24].

- Purification: After cooling, collect the product by centrifugation and wash thoroughly with DMF and ethanol to remove unreacted precursors and PVP.

Experimental Workflow for Hollow Shell Synthesis

Protocol 2: Constructing a Multichannel Charge Transfer System in 1D Nanofibers

This protocol is based on the fabrication of Au/Pt/WO₃/TiO₂ nanofibers for enhanced H₂ evolution [29].

- Objective: To create a 1D Z-scheme heterostructure with dual cocatalysts for simultaneous electron and hole extraction.

- Materials:

- Titanium precursor (e.g., Titanium(IV) isopropoxide)

- Tungsten precursor (e.g., Ammonium metatungstate)

- Polymeric matrix (e.g., PVP for electrospinning)

- Solvent (e.g., Ethanol, Acetic acid)

- Metal salts (Chloroauric acid, Chloroplatinic acid)

- Procedure:

- Electrospinning precursor solution: Prepare a homogeneous solution containing the Ti and W precursors within the polymeric matrix. Load the solution into a syringe for electrospinning.

- Electrospinning: Use a high voltage to draw fibers from the solution, collecting them on a rotating drum to form a non-woven mat.

- Calcination: Subject the collected fiber mat to a controlled calcination process in air. This step removes the polymer and crystallizes the metal oxides, forming WO₃/TiO₂ composite nanofibers [29].

- Photodeposition of cocatalysts: Disperse the calcined nanofibers in an aqueous solution containing methanol (as a sacrificial agent).

- Add a gold salt (e.g., HAuClâ‚„) and irradiate with UV-Vis light to photodeposit Au nanoparticles.

- Similarly, add a platinum salt (e.g., H₂PtCl₆) to photodeposit Pt nanoparticles.

- The final product is Au/Pt/WO₃/TiO₂ nanofibers, where the 1D structure provides a direct path, the Z-scheme between TiO₂ and WO₃ enhances separation, and Au/Ps serve as electron collectors and plasmonic sensitizers [29].

Multichannel Charge Transfer Pathways in a 1D Z-Scheme System

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Nanostructuring and Charge Carrier Management

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Key Characteristic / Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| PVP (Polyvinylpyrrolidone) | Structure-directing agent and stabilizer. | Controls the growth kinetics and morphology during nanostructure synthesis, crucial for forming hollow architectures [24]. |

| NHâ‚‚-MIL-125(Ti) | Sacrificial template and Ti precursor. | A titanium-based MOF that can be controllably etched or converted to form defined TiOâ‚‚-containing heterostructures [24]. |