Advanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Pollutants in Wastewater: Mechanisms, Materials, and Biomedical Applications

This comprehensive review explores photocatalytic degradation as a sustainable advanced oxidation process for eliminating persistent organic pollutants from wastewater, with particular relevance for pharmaceutical and biomedical research.

Advanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Pollutants in Wastewater: Mechanisms, Materials, and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores photocatalytic degradation as a sustainable advanced oxidation process for eliminating persistent organic pollutants from wastewater, with particular relevance for pharmaceutical and biomedical research. The article covers fundamental mechanisms involving reactive oxygen species generation, examines innovative catalyst designs like heterojunctions and doped semiconductors, and details methodological approaches for optimizing degradation efficiency of drugs and dyes. It further provides troubleshooting guidance for operational challenges, presents validation protocols through kinetic and toxicity analyses, and discusses the direct implications for reducing pharmaceutical contamination in water systems, thereby supporting drug development and environmental safety.

Fundamental Principles and Emerging Photocatalyst Materials for Wastewater Remediation

Photocatalysis has emerged as a promising advanced oxidation process (AOP) for addressing the critical challenge of organic pollutant removal from wastewater. This technology leverages light-activated catalysts to generate highly reactive species that can degrade recalcitrant compounds which conventional treatment methods cannot effectively remove [1]. The process is particularly valued for its environmental friendliness, sustainability, and energy efficiency, as it primarily requires only light and semiconductors to drive the degradation of pollutants with low biodegradability and high complexity [2]. Understanding the fundamental mechanism—from initial photon absorption to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)—is essential for optimizing these systems for applications ranging from industrial wastewater treatment to the removal of pharmaceuticals and agricultural chemicals [3] [2]. This document details the core principles and experimental approaches for investigating this mechanism, providing a framework for researchers and scientists working in environmental remediation and related fields.

The Photocatalytic Mechanism: A Step-by-Step Analysis

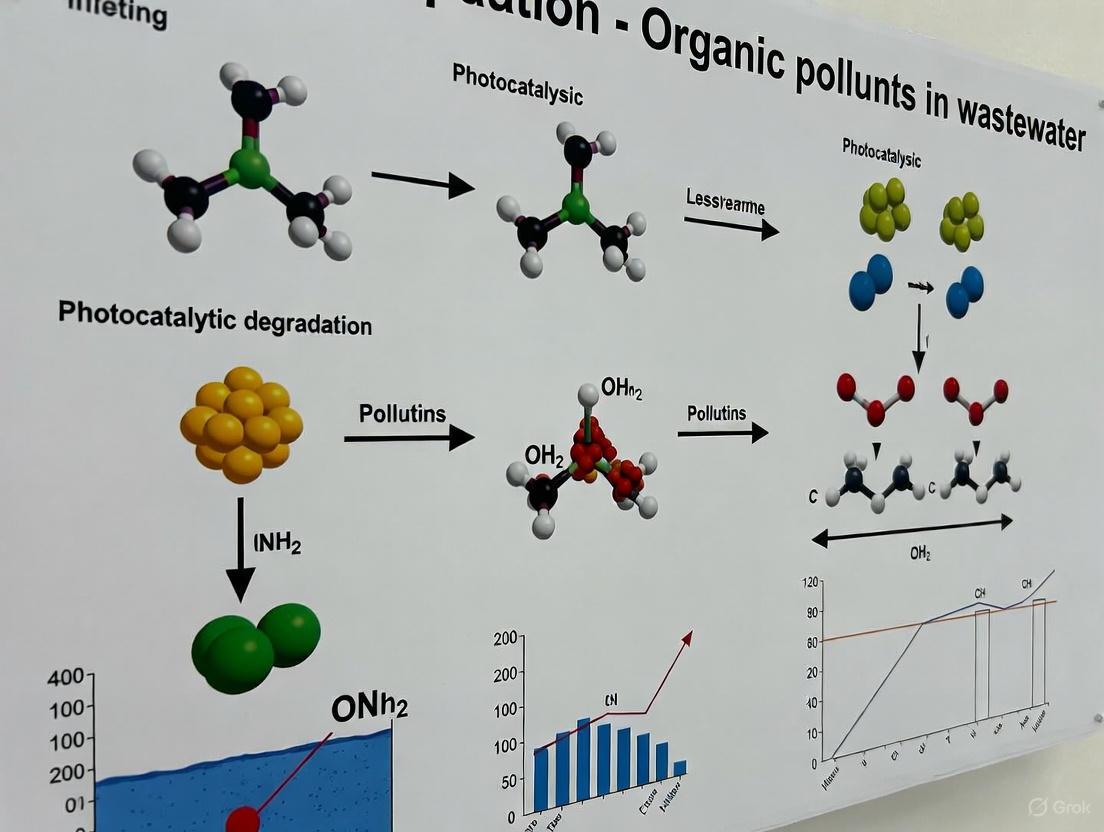

The photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants is a complex process initiated by light absorption and culminating in the mineralization of contaminants. The mechanism can be broken down into five sequential stages, as illustrated in the following diagram and elaborated in the subsequent analysis.

Diagram 1: The sequential mechanism of photocatalysis, from light absorption to pollutant degradation.

The process begins when a semiconductor photocatalyst, such as TiOâ‚‚ or ZnO, absorbs photons with energy equal to or greater than its band gap energy (E_g). This absorption promotes an electron (eâ») from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB), creating a positively charged hole (hâº) in the valence band. This results in the formation of an electron-hole (eâ»/hâº) pair [1]. A narrower band gap facilitates this electron-hole pair generation by enabling the use of lower-energy photons, such as those in the visible light spectrum [1]. For instance, while pure TiOâ‚‚ is primarily UV-active, green-synthesized ZnO nanoparticles have been reported with a band gap of 2.92 eV, allowing for more efficient utilization of visible light [2].

Charge Carrier Separation and Migration

The photogenerated electrons and holes must then separate and migrate to the surface of the photocatalyst without recombining. Recombination is a competitive process that reduces photocatalytic efficiency. Strategies to minimize recombination include doping with foreign elements, creating surface defects, forming heterojunctions with other semiconductors, and using co-catalysts [1]. For example, coupling TiOâ‚‚ with clay to form a nanocomposite not only prevents TiOâ‚‚ aggregation but also enhances charge separation, thereby improving the overall photocatalytic activity [3]. The successful migration of these charge carriers to the catalyst surface is critical for the subsequent redox reactions.

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Generation

Once on the surface, the electrons and holes drive a series of redox reactions with surrounding molecules:

- Hole Reactions: The photogenerated holes (hâº) can oxidize water molecules (Hâ‚‚O) or hydroxide ions (OHâ») to produce powerful hydroxyl radicals (•OH) [3] [1].

- Electron Reactions: The excited electrons (eâ») in the conduction band can reduce molecular oxygen (Oâ‚‚) adsorbed on the catalyst surface to generate superoxide anion radicals (O₂•â»), which can further protonate to form hydroperoxyl radicals (•OOH) and eventually hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚), leading to more •OH radicals [1].

Among these, hydroxyl radicals (•OH) are often the primary oxidative species due to their high reactivity, as confirmed by both radical scavenger experiments and Density Functional Theory (DFT) predictions [3].

Pollutant Adsorption and Oxidative Degradation

The final stage involves the adsorption of organic pollutant molecules onto the photocatalyst surface and their subsequent oxidation. The adsorption is influenced by the surface charge of the catalyst, which is determined by the solution pH relative to the catalyst's point of zero charge (PZC) [3] [1]. Once adsorbed, the generated ROS (e.g., •OH and O₂•â») attack the pollutant molecules, breaking them down into smaller, less harmful intermediates and ultimately mineralizing them into COâ‚‚, Hâ‚‚O, and inorganic ions [3] [1]. The degradation pathway can be complex; for the dye BR46, GC-MS analysis verified its breakdown into non-toxic intermediates [3].

Quantitative Performance Data

The efficiency of photocatalysis is quantified using several key metrics. The tables below summarize performance data from recent studies and the figures of merit used for evaluation.

Table 1: Photocatalytic Performance in Pollutant Degradation

| Photocatalyst | Target Pollutant(s) | Light Source | Optimal Catalyst Loading | Degradation Efficiency | Key Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiO₂–clay nanocomposite [3] | Basic Red 46 (BR46) dye | UV-C lamp (8 W) | Immobilized bed | 98% dye removal, 92% TOC reduction | Pseudo-first-order rate constant: 0.0158 minâ»Â¹ |

| ZnO (N-gZnOw) [2] | Clomazone, Tembotrione, Ciprofloxacin, Zearalenone | Sunlight | 0.5 mg/cm³ | 98.2%, 95.8%, 96.2%, 96.6% removal, respectively | Band gap: 2.92 eV; Particle size: 14.9 nm |

Table 2: Figures of Merit (FOM) in Photocatalysis [4]

| Figure of Merit | Description | Utility & Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction Rate (r) | The speed of the photocatalytic reaction (e.g., pollutant degradation or Hâ‚‚ production). | A fundamental metric, but depends on experimental conditions like catalyst mass and light intensity. |

| Apparent Quantum Yield (AQY) | The ratio of the reaction rate to the incident photon flux. | Accounts for light absorption but does not fully consider scattering and reflection. |

| Photocatalytic Space Time Yield (PSTY) | The reaction rate per unit volume of the reactor. | Useful for evaluating reactor efficiency and scalability. |

| Turnover Number (TON) & Turnover Frequency (TOF) | TON: moles of product per mole of catalytic sites. TOF: TON per unit time. | Requires knowledge of active sites, which can be obscured in semiconductors. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Photocatalytic Degradation of a Model Dye Using an Immobilized Nanocomposite

This protocol outlines the procedure for degrading organic dyes using a TiOâ‚‚-clay nanocomposite in a rotary photoreactor, based on a study that achieved 98% removal of Basic Red 46 [3].

I. Materials and Reagents

- Photocatalyst: TiOâ‚‚-P25 (Degussa).

- Support Material: Industrial clay powder.

- Immobilization Agent: Silicone adhesive.

- Model Pollutant: Basic Red 46 (BR46, Câ‚₈Hâ‚‚â‚BrN₆) or similar.

- Solvent: Distilled water.

- Substrate: Flexible plastic (talc) sheets (17 cm x 35 cm).

II. Nanocomposite Synthesis and Immobilization

- Weighing: Precisely combine 0.7 g of TiOâ‚‚ and 0.3 g of clay powder in a beaker (70:30 ratio).

- Mixing: Add 5-10 mL of distilled water and stir continuously with a magnetic stirrer for 4 hours at room temperature.

- Drying: Transfer the mixture to an oven and dry at 60°C for 6 hours.

- Grinding: Grind the dried product into a fine powder using a mortar and pestle.

- Immobilization:

- Apply a thin, uniform layer of silicone adhesive to the plastic substrate.

- Uniformly sieve the TiOâ‚‚-clay powder onto the adhesive-coated substrate.

- Allow the coated substrate to dry at ambient temperature for 24 hours.

III. Photocatalytic Reactor Setup and Operation

- Reactor Assembly: The rotary photoreactor consists of:

- A water tank (500 mL capacity).

- An electric motor to drive a PVC cylinder (17 cm length, 11 cm diameter).

- A quartz cylindrical tube placed inside the rotating cylinder to house an 8-watt UV-C lamp.

- Experimental Run:

- Prepare an aqueous solution of BR46 dye at the desired initial concentration (e.g., 20 mg/L).

- Pour the solution into the reactor tank.

- Set the rotational speed of the cylinder (e.g., 5.5 rpm) and turn on the UV lamp.

- Conduct experiments for a specified duration (e.g., 90 min), taking samples at regular intervals.

IV. Analysis and Quantification

- Dye Concentration: Monitor the degradation by measuring the absorbance of the dye solution using UV-Vis spectrophotometry.

- Mineralization Efficiency: Use a Total Organic Carbon (TOC) analyzer to quantify the reduction in organic carbon content.

- Degradation By-products: Identify intermediates using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS).

- Reactive Species Identification: Perform radical scavenger tests to identify the primary ROS involved (e.g., using isopropanol for •OH quenching).

Protocol: Synthesis of Green ZnO Nanoparticles for Solar-Driven Degradation

This protocol describes an eco-friendly synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles for the degradation of various organic pollutants under sunlight [2].

I. Green Synthesis of ZnO Nanoparticles

- Extract Preparation: Prepare an extract using green tea leaves and water.

- Precursor Solution: Use a zinc nitrate solution as a precursor.

- Synthesis: Mix the precursor with the plant extract in an aqueous medium to form the nanoparticles.

- Characterization: Characterize the synthesized nanoparticles (N-gZnOw) using:

- X-Ray Diffraction (XRD): For crystallinity and phase structure.

- SEM: For morphological analysis.

- UV-Vis Spectroscopy: To determine the band gap energy.

- Zeta Potential Measurements: To find the isoelectric point.

II. Photocatalytic Testing

- Pollutant Selection: Use pollutants like clomazone (herbicide), ciprofloxacin (antibiotic), or zearalenone (mycotoxin).

- Reaction Conditions:

- Use an optimal catalyst loading of 0.5 mg/cm³.

- Perform reactions under natural sunlight or a solar simulator.

- Efficiency Analysis: Use Liquid Chromatography-Electrospray Ionization-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-ESI-MS/MS) to confirm pollutant degradation and identify intermediates.

The workflow for these experimental processes is visualized below.

Diagram 2: A generalized workflow for photocatalytic degradation experiments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Photocatalysis Research

| Material/Reagent | Function & Role in Photocatalysis | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Semiconductor Photocatalysts | The primary light-absorbing material that generates electron-hole pairs. | TiO₂-P25 [3], ZnO nanoparticles [2], NaTaO₃ [4]. |

| Support Materials & Composites | Enhance surface area, prevent aggregation, and adsorb pollutants for closer contact with ROS. | Clay in TiOâ‚‚-clay composites [3], Graphene derivatives (rGO) [3]. |

| Model Organic Pollutants | Representative compounds used to benchmark and study photocatalytic efficiency. | Basic Red 46 (azo dye) [3], Clomazone (herbicide) [2], Ciprofloxacin (antibiotic) [2]. |

| Radical Scavengers | Chemical compounds used to quench specific ROS and elucidate the degradation mechanism. | Isopropanol (for •OH), p-benzoquinone (for O₂•â»), EDTA (for hâº) [3]. |

| Immobilization Agents | Used to fix catalyst particles onto solid supports for easy separation and reusability. | Silicone adhesive [3]. |

| Characterization Tools | Instruments for analyzing the physical, chemical, and optical properties of photocatalysts. | XRD, FE-SEM, UV-Vis DRS, BET surface area analyzer [3]. |

| Benzo(b)triphenylen-10-ol | Benzo(b)triphenylen-10-ol|High Purity|C22H14O | Buy Benzo(b)triphenylen-10-ol , a research-grade PAH for biochemical studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 5-Hydroxyheptan-2-one | 5-Hydroxyheptan-2-one|C7H14O2 | 5-Hydroxyheptan-2-one (C7H14O2) is a hydroxy ketone for research. This product is for laboratory research use only and is not intended for personal use. |

The photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants presents a promising advanced oxidation process (AOP) for addressing the persistent challenge of wastewater treatment. Semiconductor-based photocatalysis utilizes light energy to generate electron-hole pairs that form highly reactive species capable of mineralizing complex organic contaminants into harmless compounds like CO₂ and H₂O [5]. This technology has gained significant research attention due to its potential to utilize solar energy, operate at ambient temperatures, and achieve complete mineralization without generating secondary pollution [6] [7]. Among various semiconductors, titanium dioxide (TiO₂), zinc oxide (ZnO), and graphitic carbon nitride (g-C₃N₄) have emerged as particularly promising materials due to their unique properties, though each presents distinct challenges that band gap engineering strategies seek to overcome.

Fundamental Properties and Band Gap Characteristics

The photocatalytic activity of semiconductors originates from their electronic structure, particularly the energy separation between the valence band (VB) and conduction band (CB) known as the band gap. When photons with energy equal to or greater than this band gap strike the semiconductor, electrons are excited from the VB to the CB, leaving holes in the VB and creating electron-hole pairs that drive redox reactions [5]. The efficiency of this process depends critically on the band gap energy, which determines the range of utilizable light, and the positions of the VB and CB, which govern the redox potential of the generated charge carriers.

Table 1: Fundamental Properties of Key Semiconductor Photocatalysts

| Semiconductor | Band Gap (eV) | Light Absorption Range | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiO₂ | 3.0–3.2 [6] | UV | Excellent photostability, non-toxicity, low cost [8] | Limited visible light utilization [6] |

| ZnO | ~3.37 [8] | UV | High photocatalytic efficiency, inexpensive [8] | Photo-corrosion, rapid charge recombination |

| g-C₃N₄ | 2.7–2.8 [6] | Visible | Visible light activity, thermal/chemical stability, metal-free [8] [9] | Fast electron-hole recombination, low surface area [9] [6] |

Band Gap Engineering Strategies

Heterojunction Construction

Creating interfaces between different semiconductors represents one of the most effective approaches to enhance charge separation and extend light absorption. The TiO₂-ZnO/g-C₃N4 nanocomposite demonstrates this principle, where the combined system shows enhanced performance for dye removal and hydrogen generation compared to individual components [8]. Similarly, TiO₂/g-C₃N₄ heterojunctions have proven highly effective for degrading persistent pollutants like monochlorophenols (MCPs), achieving removal efficiencies of 87% for 2-chlorophenol compared to less than 50% with either component alone [9]. The heterojunction between TiO₂ and g-C₃N₄ improves charge separation through transfer of photogenerated electrons from g-C₃N₄ to TiO₂, reducing recombination rates and enhancing photocatalytic activity [6].

Metal and Non-Metal Doping

Incorporating metal elements into semiconductor structures can modify their electronic properties and enhance visible light absorption. Noble metals like gold (Au) act as electron mediators when deposited on semiconductor heterostructures, promoting charge carrier transfer due to localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) effects [10]. In the TiO₂@Au/g-C₃N₄ system, Au nanoparticles accumulate and transfer photo-stimulated electrons from TiO₂ to g-C₃N₄, creating an efficient Z-scheme photocatalytic mechanism that preserves strong redox capabilities [10].

Nanocomposite Formation with Supporting Materials

Combining semiconductors with supporting materials like clay can enhance surface area and stability. The TiO₂-clay nanocomposite demonstrates this advantage, exhibiting an increased BET surface area of 65.35 m²/g compared to 52.12 m²/g for pure TiO₂ [3]. The clay acts as a supportive matrix that prevents TiO₂ aggregation while providing additional adsorption sites for pollutants, creating a synergistic system that achieves 98% dye removal and 92% total organic carbon reduction under optimal conditions [3].

Application Notes: Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Synthesis of TiO₂-ZnO/g-C₃N₄ Nanocomposite

Purpose: To create an efficient heterostructured photocatalyst for dye degradation and hydrogen generation [8].

Materials: Titanium dioxide (TiOâ‚‚), zinc oxide (ZnO), urea, methylene orange (MO), rhodamine B (RhB), methanol, ascorbic acid, citric acid, hydrochloric acid, sodium hydroxide.

Procedure:

- g-C₃N₄ Preparation: Heat urea powder in a muffle furnace at a heating rate of 10°C/min to 600°C and maintain at this temperature for 4 hours. After cooling to room temperature, collect the resulting bulk g-C₃N₄ [9].

- Nanocomposite Formation: Combine TiO₂ and ZnO precursors with the synthesized g-C₃N₄ using chemical reduction method.

- Characterization: Analyze the crystallinity and phase structure by X-ray diffraction (XRD). Examine surface morphology and elemental composition using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Determine optical properties through UV-Vis spectroscopy and photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy [8].

Protocol 2: Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of g-C₃N₄/TiO₂ Heterostructures

Purpose: To rapidly produce visible-light-activated photocatalysts for degradation of recalcitrant azo dyes [6].

Materials: Pre-synthesized g-C₃N₄ nanosheets, titanium precursor, methyl orange (MO), urea.

Procedure:

- g-C₃N₄ Preparation: Thermal polycondensation of urea at 500-600°C for several hours [6].

- Heterostructure Formation: Mix different weight ratios of g-C₃N₄ (15, 30, and 45 wt.%) with TiO₂ precursor. Subject the mixture to microwave irradiation for 1 hour.

- Characterization: Analyze phase structure by XRD, examine morphology through SEM and STEM, determine chemical states via XPS, and evaluate optical properties using UV-Vis absorption spectroscopy [6].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Engineered Photocatalysts

| Photocatalyst | Target Pollutant | Experimental Conditions | Removal Efficiency | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiO₂-ZnO/g-C₃N₄ [8] | Methylene Orange, Rhodamine B | Sunlight irradiation | High degradation rate | Bimetallic structure with g-C₃N₄ enhanced charge separation |

| 40TiO₂/g-C₃N₄ [9] | Monochlorophenols (2-CP, 3-CP, 4-CP) | UV-Vis light, 25 ppm, 1 g/L catalyst | 87% (2-CP), 64% (4-CP) | Superior to individual components (<50%) |

| 30% g-C₃N₄/TiO₂ [6] | Methyl Orange (MO) | Solar simulator, 4 hours | 85% | 2× and 10× more efficient than pure TiO₂ and g-C₃N₄ |

| TiO₂-clay [3] | Basic Red 46 (BR46) | UV light, 20 mg/L, 90 min | 98% | Enhanced surface area (65.35 m²/g) and stability |

Protocol 3: Evaluation of Photocatalytic Performance

Purpose: To assess the degradation efficiency of synthesized photocatalysts for organic pollutants [9] [3].

Materials: Photocatalyst, target pollutant (dye or phenolic compound), radical scavengers (e.g., ammonium oxalate, benzoquinone, isopropyl alcohol), UV-Vis spectrophotometer, TOC analyzer.

Procedure:

- Photocatalytic Testing: Prepare pollutant solution at specific concentration (e.g., 10-25 mg/L). Add photocatalyst (0.2-1 g/L) and maintain suspension under continuous stirring. Irradiate with appropriate light source (UV, visible, or solar simulator). Withdraw samples at regular intervals.

- Analysis: Measure pollutant concentration by UV-Vis spectroscopy. Evaluate mineralization efficiency through total organic carbon (TOC) analysis.

- Reactive Species Identification: Conduct radical scavenging experiments using specific quenchers—ammonium oxalate for holes, benzoquinone for superoxide radicals, and isopropyl alcohol for hydroxyl radicals [9] [3].

- Byproduct Identification: Analyze degradation intermediates using GC-MS with HP-5MS UI column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 µm) [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Photocatalyst Development and Evaluation

| Reagent/Chemical | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Titanium Dioxide (TiOâ‚‚-P25) [3] | Benchmark photocatalyst | Mixed-phase (anatase/rutile), band gap ~3.2 eV |

| Urea [9] [6] | g-C₃N₄ precursor | Nitrogen-rich, thermal polycondensation at 500-600°C |

| Hydrofluoric Acid (HF) [10] | Morphology control for TiOâ‚‚ | Exposes high-energy (001) facets |

| Tetrabutyl Titinate [10] | TiOâ‚‚ precursor | Hydrolyzes to form anatase phase |

| Methylene Orange (MO) [8] [6] | Model azo dye pollutant | Recalcitrant, visible chromophore for degradation monitoring |

| Rhodamine B (RhB) [8] [10] | Model cationic dye | Fluorescent, used for photocatalytic activity assessment |

| Monochlorophenols (MCPs) [9] | Model persistent organic pollutants | EPA-priority contaminants, low biodegradability |

| Ammonium Oxalate [9] | Hole (hâº) scavenger | Identifies role of holes in degradation mechanism |

| Benzoquinone [9] | Superoxide (Oâ‚‚â») scavenger | Determines contribution of superoxide radicals |

| Isopropyl Alcohol [9] | Hydroxyl radical (•OH) scavenger | Evaluates role of hydroxyl radicals in degradation |

| 2-Methyl-1-phenylguanidine | 2-Methyl-1-phenylguanidine|Research Chemical | 2-Methyl-1-phenylguanidine for research. Investigating its potential as a 5-HT3 receptor ligand. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 4,4'-Dichlormethyl-bibenzyl | 4,4'-Dichlormethyl-bibenzyl|High-Purity|RUO |

Reaction Mechanisms and Pathways

The enhanced photocatalytic activity of engineered semiconductors stems from improved charge separation and tailored reaction pathways. In Z-scheme systems like TiOâ‚‚@Au/g-C₃Nâ‚„, Au nanoparticles serve as electron mediators that transfer photoexcited electrons from the TiOâ‚‚ conduction band to the g-C₃Nâ‚„ valence band, effectively separating the reduction and oxidation reactions while preserving strong redox potentials [10]. This mechanism enhances the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), particularly superoxide radicals (Oâ‚‚â») and hydroxyl radicals (•OH), which play pivotal roles in degrading organic pollutants.

Radical trapping experiments have demonstrated that different reactive species dominate in various systems. For g-C₃N₄/TiO₂ heterostructures, superoxide radicals were identified as the primary species responsible for methyl orange degradation, with minimal involvement of hydroxyl radicals, suggesting a type-II heterojunction mechanism [6]. In contrast, hydroxyl radicals were determined to be the main oxidative species in TiO₂-clay systems for BR46 dye degradation [3]. Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations support these experimental findings, predicting favorable attack sites on dye molecules and confirming the degradation pathways [3].

Band gap engineering through heterojunction construction, elemental doping, and nanocomposite formation has significantly advanced the photocatalytic performance of TiO₂, ZnO, and g-C₃N₄ for wastewater treatment. The strategic combination of these materials creates synergistic systems that enhance light absorption, improve charge separation, and provide abundant active sites for pollutant degradation. The experimental protocols and application notes presented herein provide researchers with practical methodologies for developing and evaluating advanced photocatalytic systems. Future research directions should focus on targeting emerging contaminants with environmental persistence, such as perfluorinated compounds and pharmaceuticals, while improving catalyst efficiency in real water matrices with multicomponent interfering ions [5]. The development of conducting polymer-based nanocomposites also represents a promising but underexplored area for future photocatalyst design [7].

Application Notes

The photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants in wastewater represents a promising advanced oxidation process for addressing water contamination challenges. Recent research has focused on developing next-generation photocatalytic materials that enhance visible light absorption, improve charge separation efficiency, and increase stability for practical applications. Three primary material classes have emerged as particularly effective: Z-scheme heterojunctions, doped semiconductors, and carbon-based composites.

Z-Scheme Heterojunction Photocatalysts

Z-scheme heterojunctions represent a significant advancement over traditional heterojunction systems by mimicking natural photosynthesis and enabling more efficient charge separation while maintaining strong redox potential [11]. These systems typically combine two semiconductor materials with staggered band structures, connected through an electron mediator or direct interface, to create a vectorial charge transfer pathway.

Recent studies have demonstrated the exceptional performance of 2D/2D Z-scheme WO₃/g-C₃N₄ heterojunctions for environmental applications [12]. These materials exhibit considerable photocatalytic performance for degrading various organic pollutants without requiring cocatalysts. The 40%WO₃/g-C₃N₄ composite showed exceptional degradation efficiency for multiple organic dyes, achieving nearly complete degradation of rhodamine B (RhB) within 20 minutes under visible light irradiation [12]. The same system also demonstrated applications in nitrogen fixation, simultaneously achieving photocatalytic nitrogen reduction reaction (NRR) and nitrogen oxidation reaction (NOR) to produce NH₄⺠and NO₃⻠using air as a nitrogen source [12].

Another study on g-C₃Nâ‚„/WO₃ Z-scheme heterojunctions reported a 97.9% degradation efficiency for RhB within 15 minutes and 93.3% for tetracycline hydrochloride (TC-HCl) within 180 minutes under visible light [13]. The system maintained 97.8% efficiency after four cycles, demonstrating excellent stability and reusability. Radical trapping experiments confirmed that holes (hâº) and superoxide radicals (·Oâ‚‚â») served as the primary reactive species in the degradation mechanism [13].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Representative Z-Scheme Heterojunction Photocatalysts

| Photocatalyst System | Target Pollutant | Degradation Efficiency | Time Required | Light Source | Stability Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40%WO₃/g-C₃N₄ [12] | Rhodamine B (RhB) | ~100% | 20 min | Visible light | High recyclability |

| g-C₃N₄/WO₃ [13] | RhB | 97.9% | 15 min | Visible light | 97.8% after 4 cycles |

| g-C₃N₄/WO₃ [13] | TC-HCl | 93.3% | 180 min | Visible light | Maintained high efficiency |

| 40%WO₃/g-C₃N₄ [12] | Tetracycline-HCl | Significant degradation | Not specified | Visible light | Good photocatalytic stability |

Doped Semiconductor Photocatalysts

Doping represents a strategic approach to enhance the performance of semiconductor photocatalysts by modifying their electronic properties, reducing band gaps, and minimizing electron-hole recombination [14]. Metal oxide semiconductors including TiO₂, ZnO, CeO₂, WO₃, and ZrO₂ have been extensively explored as photocatalysts due to their high stability across wide pH ranges, low toxicity, and strong oxidizing capabilities [14]. However, these materials face limitations including wide band gaps (primarily activating under UV light) and rapid recombination of photogenerated electron-hole pairs [14] [15].

Doping with rare-earth elements has proven particularly effective due to their ability to interact quickly with functional groups through 4f empty orbitals [14]. For WO₃, which has a narrower band gap (2.7-2.8 eV) than TiO₂, doping further enhances visible light absorption and charge separation efficiency [15]. Similarly, graphitic carbon nitride (g-C₃N₄), with a bandgap of approximately 2.7 eV and absorption edge at 450-470 nm, benefits from doping to reduce its inherent limitations of serious photo-induced electron-hole recombination and narrow visible light absorption range [13] [15].

Table 2: Comparison of Key Semiconductor Photocatalysts for Wastewater Treatment

| Semiconductor | Band Gap (eV) | Primary Activation Range | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiOâ‚‚ [15] | 3.0-3.2 | Ultraviolet (λ ≤ 390 nm) | High activity, well-studied, stable | Limited visible light absorption, rapid eâ»/h⺠recombination |

| WO₃ [15] | 2.7-2.8 | Visible light | Good visible light absorption, stable, non-toxic | Low conduction band position, recombination issues |

| g-C₃Nâ‚„ [15] | ~2.7 | Visible light (up to 470 nm) | Metal-free, easy synthesis, tunable | High eâ»/h⺠recombination, limited oxidation potential |

| Doped Variants [14] | Reduced | Extended visible light | Enhanced visible light response, reduced recombination | Synthesis complexity, potential cost increase |

Carbon-Based Composite Photocatalysts

Carbon-based materials have emerged as promising components in photocatalytic composites due to their exceptional electrical conductivity, tunable surface properties, structural diversity, and environmental compatibility [16]. Carbon nanostructures including graphene, carbon nanotubes, carbon dots, graphitic carbon nitride, and fullerenes offer unique advantages for enhancing photocatalytic performance through improved charge separation and transport [16].

The integration of carbon materials with metal nanoparticles creates synergistic effects that significantly boost photocatalytic activity. Gold (Au) and Silver (Ag) nanoparticles on graphene sheets have demonstrated enhanced photocatalytic performance, serving dual functions as both light absorbers and catalytic centers [16]. These carbon-metal nanocomposites facilitate rapid electron transfer during redox reactions while minimizing charge recombination, addressing critical limitations of standalone semiconductor photocatalysts [16].

Carbon-based composites have shown particular effectiveness for diverse environmental applications including degradation of organic dyes, hydrogen production through water splitting, and carbon dioxide reduction [16]. Their hydrophobic nature, chemical stability across acidic and basic conditions, thermal stability, and potential for low-cost production make them attractive for scalable wastewater treatment applications [16].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Synthesis of 2D/2D Z-Scheme WO₃/g-C₃N₄ Heterojunctions

Principle: This protocol describes the preparation of 2D/2D Z-scheme WO₃/g-C₃N₄ heterojunctions through a facile rapid calcination method, creating an efficient photocatalytic system for organic pollutant degradation and nitrogen fixation [12].

Materials:

- Sodium tungstate dihydrate (Na₂WO₄·2H₂O)

- Graphitic carbon nitride (g-C₃N₄)

- Deionized water

- Hydrochloric acid (HCl)

Procedure:

- Begin with pre-synthesized g-C₃N₄ powder, which can be prepared through thermal polymerization of nitrogen-rich precursors such as melamine at 550°C for 4 hours [13].

- Prepare a homogeneous dispersion by adding 4g of g-C₃N₄ to 25mL deionized water with ultrasonic treatment for 1 hour [13].

- Add 0.584g NaCl and 1.65g Na₂WO₄·2H₂O to the dispersion under constant stirring.

- Gradually introduce 5mL hydrochloric acid to the solution while continuing stirring for 3 hours until a yellow precipitate forms.

- Transfer the suspension to a Teflon-lined autoclave and maintain at 160°C for 12 hours.

- After cooling to room temperature, filter the product and rinse thoroughly with deionized water to remove impurities.

- Dry the obtained sample in an oven at 80°C for 8 hours.

- Finally, calcine the powder at 450°C for 3 hours with a heating rate of 5°C/min to obtain the crystalline WO₃/g-C₃N₄ composite.

- For optimization, prepare composites with different WO₃ loading percentages (e.g., 20%, 40%, 60%) by varying the precursor ratios [12].

Characterization:

- Analyze crystal structure using X-ray diffraction (XRD)

- Examine morphology and interface structure with transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

- Determine chemical states and composition via X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS)

- Assess optical properties with UV-Vis diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (DRS)

Protocol 2: Photocatalytic Degradation Assessment of Organic Pollutants

Principle: This protocol evaluates the photocatalytic performance of synthesized materials for degrading organic pollutants under visible light irradiation, quantifying degradation efficiency and identifying reactive species [13].

Materials:

- Target pollutants (RhB, TC-HCl, MB, MO, etc.)

- Photocatalyst powder

- Scavengers: Ammonium oxalate (AO, h⺠scavenger), Benzoquinone (BQ, ·O₂⻠scavenger), Isopropyl alcohol (IPA, ·OH scavenger)

- 300W Xe lamp with 400nm filter

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer

Procedure:

- Prepare pollutant solutions at specific concentrations (e.g., 20mg/L RhB, 30mg/L TC-HCl) using deionized water.

- In a standard reaction setup, disperse 0.1g photocatalyst in 100mL pollutant solution.

- Sonicate the suspension for 5 minutes to ensure uniform dispersion.

- Pre-adsorption phase: Stir the suspension magnetically in darkness for 30 minutes to establish adsorption-desorption equilibrium.

- Initiate irradiation using a 300W Xe lamp equipped with a 400nm filter to provide visible light.

- At predetermined time intervals (e.g., every 5 minutes for RhB, longer intervals for TC-HCl), withdraw 4mL aliquots.

- Immediately filter the aliquots to remove catalyst particles.

- Analyze the filtrate using UV-Vis spectrophotometry to determine residual pollutant concentration.

- Calculate degradation efficiency using the formula: Efficiency (%) = [(C₀ - Cₜ)/C₀] × 100, where C₀ is initial concentration and Cₜ is concentration at time t.

Reactive Species Identification:

- For radical trapping experiments, introduce specific scavengers before irradiation:

- 1mM ammonium oxalate (AO) for holes (hâº)

- 2mM benzoquinone (BQ) for superoxide radicals (·Oâ‚‚â»)

- 10mM isopropyl alcohol (IPA) for hydroxyl radicals (·OH)

- Compare degradation efficiency with and without scavengers to identify primary reactive species.

- For enhanced verification, perform electron spin resonance (ESR) spectroscopy with DMPO as spin trapping agent to directly detect ·OH and ·O₂⻠radicals.

Protocol 3: Synthesis of Carbon-Based Composite Photocatalysts

Principle: This protocol outlines the preparation of carbon nanostructure-metal nanocomposites for enhanced photocatalytic activity, leveraging the synergistic effects between carbon materials and metal nanoparticles [16].

Materials:

- Carbon support material (graphene oxide, carbon nanotubes, etc.)

- Metal precursors (HAuCl₄, AgNO₃, etc.)

- Reducing agents (sodium borohydride, hydrazine hydrate, etc.)

- Solvents (deionized water, ethanol)

Procedure:

- Prepare a homogeneous dispersion of carbon support material in appropriate solvent using prolonged sonication (1-2 hours).

- Add metal precursor solution to the carbon dispersion under vigorous stirring.

- Adjust pH as needed to optimize metal ion adsorption onto carbon surface.

- Slowly add reducing agent to convert metal ions to nanoparticles anchored on carbon support.

- Continue stirring for 2-4 hours to ensure complete reduction and uniform distribution.

- Recover the composite material through centrifugation or filtration.

- Wash thoroughly with deionized water and ethanol to remove unreacted precursors.

- Dry under vacuum at 60°C for 12 hours.

- For thermal treatments, calcine under inert atmosphere at optimized temperatures.

Characterization:

- Analyze metal nanoparticle size and distribution using TEM

- Determine chemical states and interfacial interactions through XPS

- Assess crystallinity with XRD

- Evaluate specific surface area and porosity through BET measurements

- Confirm optical properties via UV-Vis DRS

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Photocatalyst Development and Testing

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tungsten Trioxide (WO₃) [15] | Visible-light-driven photocatalyst | Bandgap ~2.7-2.8 eV, good stability, non-toxic | WO₃ nanoparticles, WO₃ nanorods |

| Graphitic Carbon Nitride (g-C₃N₄) [15] | Metal-free semiconductor photocatalyst | Bandgap ~2.7 eV, visible light response, easily synthesized | Bulk g-C₃N₄, exfoliated g-C₃N₄ nanosheets |

| Sodium Tungstate Dihydrate [13] | WO₃ precursor in synthesis | Provides tungsten source, water-soluble | Na₂WO₄·2H₂O for hydrothermal synthesis |

| Melamine [13] | g-C₃N₄ precursor | Nitrogen-rich organic compound, thermal polymerization | C₃H₆N₆ for g-C₃N₄ synthesis |

| Ammonium Oxalate (AO) [13] | Hole (hâº) scavenger in mechanistic studies | Selective trapping of photogenerated holes | 1mM solution for radical identification |

| Benzoquinone (BQ) [13] | Superoxide radical (·Oâ‚‚â») scavenger | Selective trapping of superoxide radicals | 2mM solution for radical identification |

| Isopropyl Alcohol (IPA) [13] | Hydroxyl radical (·OH) scavenger | Selective trapping of hydroxyl radicals | 10mM solution for radical identification |

| DMPO [13] | Spin trap for ESR spectroscopy | Forms stable adducts with radicals for detection | 5,5-Dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide |

| Carbon Nanostructures [16] | Catalyst supports and composites | High conductivity, tunable surface properties | Graphene, carbon nanotubes, carbon dots |

| 2,6-Dibenzylcyclohexanone | cis-2,6-Dibenzylcyclohexanone | cis-2,6-Dibenzylcyclohexanone is a synthetic intermediate used in medicinal chemistry research. This product is for research use only and not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

| 4-Hydroxydecan-2-one | 4-Hydroxydecan-2-one | 4-Hydroxydecan-2-one is a ketone reagent for organic synthesis and pharmaceutical research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

The pervasive discharge of pharmaceutical pollutants and industrial dyes into water systems presents a critical environmental challenge worldwide. These contaminants, originating from medical use, industrial effluents, and improper disposal, demonstrate persistence, toxicity, and resistance to conventional treatment methods, leading to bioaccumulation and potential health risks including antibiotic resistance and ecosystem disruption [17] [18]. The textile industry alone contributes approximately 20% of global water pollution, releasing complex organic dyes with over 1,900 chemicals involved in production [17]. Similarly, active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) increasingly detected in aquatic environments pose significant concerns due to their biological activity at low concentrations and inadequate removal by conventional wastewater treatment plants [19].

Within this context, photocatalytic degradation has emerged as a promising advanced oxidation process (AOP) that utilizes semiconductor materials to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) under light irradiation, effectively breaking down persistent organic pollutants into harmless end products like carbon dioxide and water [17] [18]. This application note explores recent advances in photocatalytic technologies for degrading pharmaceutical contaminants and organic dyes, providing structured experimental protocols, performance comparisons, and mechanistic insights to support researchers and scientists in developing effective water remediation strategies.

Current Research and Performance Data

Recent investigations have focused on developing innovative photocatalysts with enhanced efficiency under solar or visible light irradiation. The following tables summarize key performance data from recent studies for quantitative comparison of various photocatalytic systems.

Table 1: Performance of Photocatalysts in Degrading Organic Dyes

| Photocatalyst | Target Pollutant | Experimental Conditions | Degradation Efficiency | Time Required | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CoS nanoparticles | Methylene Blue (MB) | 0.33 g/L catalyst, 20 ppm MB, visible light | 97.7% | 90 min | [20] |

| CoS nanoparticles | Methyl Red (MR) | 0.33 g/L catalyst, 20 ppm MR, visible light | 75.3% | 90 min | [20] |

| Cu(I) CP1 (Iodide) | Methylene Blue (MB) | Minimal catalyst, Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚, sunlight | 96% | 15 min | [21] |

| TiOâ‚‚-clay nanocomposite | Basic Red 46 (BR46) | 20 mg/L dye, 5.5 rpm rotation, UV light | 98% | 90 min | [3] |

| Bismuth titanate (Biâ‚„Ti₃Oâ‚â‚‚) | Organic Dyes | Visible LED irradiation | ~98% | 60 min | [22] |

Table 2: Performance of Photocatalysts in Degrading Pharmaceutical Compounds

| Photocatalyst | Target Pollutant | Experimental Conditions | Degradation Efficiency | Time Required | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co-doped ZnFeâ‚‚Oâ‚„ (ZC20) | Acetaminophen | 0.1 g/L catalyst, 30 mg/L drug, 100W LED | 85% | 180 min | [23] |

| Pure ZnFeâ‚‚Oâ‚„ (ZC0) | Acetaminophen | 0.1 g/L catalyst, 30 mg/L drug, 100W LED | 35% | 180 min | [23] |

| Bismuth titanate (Biâ‚„Ti₃Oâ‚â‚‚) | Cefdinir | 0.05 g/L catalyst, 50 µg/mL drug, pH 5, LED | ~98% | 60 min | [22] |

| BaTiO₃ with polymers | Various APIs | Visible light irradiation | Varies by polymer & API | Dependent on system | [19] |

| TiOâ‚‚ on aluminum sludge | Ciprofloxacin | Photocatalysis with hydrodynamic cavitation | High efficiency reported | Not specified | [24] |

The data reveals that novel material engineering approaches, including doping, composite formation, and nanostructuring, significantly enhance photocatalytic performance. For instance, cobalt doping in zinc ferrite (ZC20) dramatically improved acetaminophen degradation compared to undoped ZnFeâ‚‚Oâ‚„ (85% vs. 35%) [23]. Similarly, coordination polymers like Cu(I)-CP1 achieved remarkable dye degradation within just 15 minutes, highlighting the potential for rapid treatment solutions [21].

Experimental Protocols

Synthesis of Cobalt-Doped Zinc Ferrite (ZC20) for Pharmaceutical Degradation

Application: This protocol describes the hydrothermal synthesis of cobalt-doped ZnFeâ‚‚Oâ‚„ spinel photocatalysts for efficient degradation of pharmaceutical compounds like acetaminophen [23].

Materials:

- Iron(III) nitrate nonahydrate (Fe(NO₃)₃·9H₂O), 98%

- Zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O), 98%

- Cobalt(II) nitrate hexahydrate (Co(NO₃)₂·6H₂O), 98%

- Urea (≥99%)

- Ascorbic acid (≥99%)

- Deionized water

- Ethanol (absolute)

Procedure:

- Precursor Solution Preparation: Dissolve 3.3 g of urea and 3.17 g of ascorbic acid in 40 mL deionized water under magnetic stirring until a uniform solution forms.

- Metal Ion Incorporation: Gradually add the urea-ascorbic acid solution to a mixture containing 1.3 g of zinc nitrate hexahydrate, 3.24 g of iron(III) nitrate nonahydrate, and the appropriate amount of cobalt nitrate hexahydrate (20 wt% relative to zinc) in a 100 mL beaker.

- Hydrothermal Reaction: Transfer the final mixture to a 50 mL Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave and maintain at 160°C for 6 hours in a forced-air oven.

- Product Recovery: After natural cooling to room temperature, collect the precipitate by centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 10 minutes.

- Washing and Drying: Wash the product sequentially three times with deionized water and absolute ethanol, then dry at 60°C for 12 hours in a vacuum oven.

- Calcination: Heat the dried powder at 500°C for 2 hours in a muffle furnace to obtain crystalline ZC20 photocatalyst.

Characterization: Perform XRD analysis to confirm spinel structure, FESEM to examine flower-like microsphere morphology (approximately 1 μm diameter), UV-Vis spectroscopy to determine band gap, and BET analysis for surface area measurement [23].

Photocatalytic Degradation Assessment Protocol

Application: Standardized procedure for evaluating photocatalytic performance in degrading organic pollutants under visible light irradiation [23].

Materials:

- Synthesized photocatalyst (ZC20 or other)

- Target pollutant (acetaminophen, dyes, or antibiotics)

- LED light source (50W or 100W)

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer

- Magnetic stirrer

- Centrifuge

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare aqueous solution of target pollutant at desired concentration (10-50 mg/L for pharmaceuticals).

- Adsorption-Desorption Equilibrium: Add catalyst (0.05-0.3 g/L) to 60 mL pollutant solution and stir in darkness for 60 minutes to establish equilibrium.

- Photocatalytic Reaction: Expose the mixture to visible light from LED source (10 cm distance) with continuous stirring.

- Sampling and Analysis: Withdraw 3 mL aliquots at regular time intervals (20 min). Centrifuge at 8000 rpm for 5 minutes to separate catalyst.

- Concentration Measurement: Analyze supernatant using UV-Vis spectrophotometer at characteristic wavelength (243 nm for acetaminophen).

- Efficiency Calculation: Determine degradation percentage using the formula:

( R(\%) = \frac{(A0 - At)}{A_0} \times 100 )

Where (A0) is initial absorbance after dark adsorption and (At) is absorbance at time t.

Optimization: Systematically vary parameters including catalyst dosage, pollutant concentration, pH, and light intensity to optimize degradation efficiency [23].

Synthesis of CoS Nanoparticles for Dye Degradation

Application: Simple precipitation method for preparing cost-effective cobalt sulfide photocatalysts effective for both cationic and anionic dye removal [20].

Materials:

- Cobalt chloride (CoClâ‚‚)

- Sodium sulfide nonahydrate (Na₂S·9H₂O)

- Deionized water

- Ethanol (100%)

Procedure:

- Dissolve 2.6 g of CoClâ‚‚ in 100 mL deionized water with magnetic stirring.

- Separately dissolve 2.8 g of Na₂S·9H₂O in 100 mL deionized water.

- Combine both solutions slowly in a 250 mL flask and stir continuously for 1 hour.

- Collect the resulting black precipitate by centrifugation at 1100 rpm for 25 minutes.

- Wash thoroughly three times each with ethanol and deionized water.

- Dry the final product at room temperature overnight.

- Characterize using XRD, HR-TEM, and BET analysis (expected surface area: ~33.6 m²/g) [20].

Mechanisms and Pathways

The photocatalytic degradation process follows a well-established mechanism involving multiple reactive species and degradation pathways, culminating in mineralization of organic pollutants.

Diagram 1: Photocatalytic Degradation Mechanism

The fundamental mechanism begins with photoexcitation of semiconductor catalysts upon light absorption, generating electron-hole (eâ»/hâº) pairs. These charge carriers migrate to the catalyst surface where they participate in redox reactions: holes oxidize water or hydroxide ions to produce hydroxyl radicals (•OH), while electrons reduce molecular oxygen to form superoxide radicals (Oâ‚‚â»â€¢) [17] [3]. These reactive oxygen species then attack organic pollutant molecules, breaking them down through a series of reactions into progressively smaller intermediates, ultimately mineralizing them to carbon dioxide and water [18].

Advanced analytical techniques including GC-MS, HPLC, and TOC analysis have revealed specific degradation pathways for various pollutants. For azo dyes like Basic Red 46, hydroxyl radicals initially attack the azo bond (-N=N-), the most reactive site, leading to decolorization followed by aromatic ring cleavage and formation of organic acids before complete mineralization [3]. Pharmaceutical compounds like acetaminophen undergo deacetylation, hydroxylation, and ring-opening reactions facilitated by the dominant oxidative species [23].

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Photocatalytic Studies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Photocatalytic Degradation Research

| Material/Chemical | Function/Application | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Semiconductor Catalysts | Light absorption and ROS generation | TiOâ‚‚-P25 (standard reference), ZnO, Biâ‚„Ti₃Oâ‚â‚‚, CoS, ZnFeâ‚‚Oâ‚„ |

| Dopants | Enhance visible light absorption and reduce charge recombination | Cobalt (Co), silver (Ag), nitrogen (N) |

| Support Materials | Increase surface area and prevent aggregation | Clay, graphene oxide (GO), activated carbon, polymers |

| Target Pollutants | Model compounds for degradation studies | Methylene Blue, Methyl Red, Acetaminophen, Cefdinir, Basic Red 46 |

| Oxidant Additives | Enhance ROS generation and degradation rates | Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚, peroxymonosulfate (PMS), sodium borohydride (NaBHâ‚„) |

| Characterization Tools | Material properties and performance analysis | XRD (crystallinity), BET (surface area), SEM/TEM (morphology), UV-Vis DRS (band gap) |

| Analytical Instruments | Degradation monitoring and byproduct identification | UV-Vis spectrophotometer, HPLC, GC-MS, TOC analyzer |

| 2,3,4,5-Tetrabromophenol | 2,3,4,5-Tetrabromophenol, CAS:36313-15-2, MF:C6H2Br4O, MW:409.69 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2-Hydroxy-3-methoxyxanthone | 2-Hydroxy-3-methoxyxanthone |

Photocatalytic degradation represents a highly promising technology for addressing the critical challenge of pharmaceutical pollutants and organic dyes in water systems. Recent advances in catalyst design, including doping strategies, composite materials, and nanostructuring, have significantly improved degradation efficiencies under visible and solar light, enhancing the practicality and sustainability of this approach. The integration of experimental research with theoretical calculations, particularly density functional theory (DFT), provides deeper mechanistic insights and enables rational catalyst design [3] [20].

For researchers pursuing this field, future directions should focus on developing visible-light-active photocatalysts to maximize solar energy utilization, improving catalyst stability and reusability for practical applications, addressing complex real wastewater matrices with multiple contaminants, and exploring synergistic combinations with other treatment technologies like hydrodynamic cavitation [24] or membrane filtration. Additionally, the application of machine learning in optimizing photocatalytic processes presents an emerging opportunity to accelerate catalyst discovery and system optimization [17]. Standardized protocols for performance evaluation and comprehensive analysis of degradation intermediates will be crucial for advancing these technologies from laboratory research to practical implementation in wastewater treatment systems.

Experimental Approaches and Catalyst Application Strategies for Efficient Pollutant Degradation

The removal of persistent organic pollutants from wastewater is a critical environmental challenge, and photocatalytic degradation has emerged as a powerful advanced oxidation process for addressing this issue [25]. The efficacy of this technology fundamentally depends on the properties of the semiconductor photocatalysts employed, which are in turn dictated by their synthesis methods [26]. This article examines three prominent synthesis techniques—hydrothermal methods, thermal condensation, and co-precipitation—within the context of photocatalytic materials development for environmental remediation.

Hydrothermal synthesis utilizes elevated temperatures and pressures in aqueous solutions to crystallize materials directly from solution, enabling control over morphology, crystallinity, and particle size [27] [28]. Thermal condensation involves high-temperature treatment of molecular precursors in the solid state to form extended polymeric networks, typically producing graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) structures [26]. Co-precipitation employs simultaneous precipitation of multiple metal ions from solution to form composite materials, offering advantages of simplicity, scalability, and homogeneous mixing at the molecular level [29] [30]. Each method presents distinct advantages for creating photocatalysts with specific structural features and photocatalytic performances, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Photocatalyst Synthesis Techniques

| Synthesis Method | Key Structural Features | Photocatalytic Performance | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrothermal | Tunable morphologies (nanoplates, nanorods, nanobelts); controlled crystallinity; defect engineering | ZnO-6h: k=0.017 minâ»Â¹ for dye degradation [28]; MoO₃-triazole: 60% RhB removal in 5h [27] | Morphology control; high crystallinity; relatively environmentally friendly | High pressure/temperature requirements; longer synthesis times |

| Thermal Condensation | Layered graphitic structures; adjustable surface area; tunable electronic properties | g-C₃Nâ‚„ HCN-II: k=0.01156 minâ»Â¹ for gallic acid degradation; ~80% removal in 180 min [26] | Simple equipment; metal-free catalysts; excellent stability | Limited structural control; possible irregular agglomerates |

| Co-precipitation | Spherical morphologies; nanocomposite structures; homogeneous mixing | CaO/TiO₂/γ-Al₂O₃: 98% MB degradation in 200 min [29] [30]; CuZnAl hydrotalcite: >90% phenol red degradation [31] | Scalability; cost-effectiveness; uniform composition; low temperature processing | Possible impurity incorporation; challenges in stoichiometry control |

Hydrothermal Synthesis

Principle and Applications

Hydrothermal synthesis occurs in aqueous solutions at elevated temperatures (typically 100-250°C) and pressures, facilitating the crystallization of materials through dissolution and reprecipitation processes [27]. This method enables exquisite control over morphological features including nanoplates, nanorods, nanobelts, and microfibers, which significantly impact photocatalytic performance by affecting surface area, active site availability, and charge carrier pathways [27] [28]. The extended synthesis duration allows for Ostwald ripening, where smaller particles dissolve and reprecipitate onto larger ones, resulting in improved crystallinity with reduced defects [28].

Hydrothermally synthesized photocatalysts have demonstrated remarkable efficiency in degrading various organic pollutants. For instance, triazole-modified molybdenum oxide (MoO₃) achieved 60% degradation of Rhodamine B dye after 5 hours under UV irradiation [27]. Similarly, ZnO nanoparticles synthesized hydrothermally for 6 hours exhibited the highest photocatalytic rate constant (k=0.017 minâ»Â¹) for organic pollutant degradation, outperforming samples prepared for shorter (4h) or longer (8h) durations [28]. This performance optimization highlights the importance of balancing crystallinity, morphology, and defect structure through precise control of hydrothermal parameters.

Experimental Protocol: Hydrothermal Synthesis of Triazole-Modified Molybdenum Oxide

Table 2: Key Reagents for Hydrothermal Synthesis

| Reagent | Function | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| H₃PMoâ‚â‚‚O₄₀·xHâ‚‚O | Molybdenum source | 99.9% purity |

| 1,2,4-Triazol (C₂H₃N₃) | Organic modifier & structure director | 98% purity |

| Distilled Water | Reaction solvent & medium | N/A |

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve 0.270 g of 1,2,4-triazole (Htrz) and 1.825 g of phosphomolybdic acid (H₃PMoâ‚â‚‚Oâ‚„â‚€) in 10 mL of distilled water [27].

- Reaction Setup: Transfer the solution to a Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave, ensuring the vessel is filled to approximately 70-80% of its capacity to maintain appropriate pressure during heating [27].

- Hydrothermal Treatment: Seal the autoclave and heat at 180°C for 5 days without agitation [27].

- Product Recovery: After cooling to room temperature, collect the resulting precipitate by filtration or centrifugation.

- Purification: Wash the product sequentially with distilled water and ethanol to remove any unreacted precursors or impurities.

- Drying: Dry the purified product at 60-80°C in an oven overnight to obtain the final [MoO₃(Htrz)₀.₅] hybrid compound [27].

Characterization:

- Structural Analysis: Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) confirms crystallinity and phase purity. The material should exhibit an orthorhombic structure (space group Pbcm) with lattice parameters a = 3.933(1) Ã…, b = 13.856(1) Ã…, c = 13.367(4) Ã… [27].

- Morphological Examination: Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) reveals the two-dimensional layered structure constructed from corner-sharing {MoO₆} octahedra [27].

- Optical Properties: UV-Vis diffuse reflectance spectroscopy determines the band gap energy, which is approximately 2.85 eV for the triazole-modified MoO₃ compound [27].

Diagram 1: Hydrothermal synthesis workflow (76 characters)

Thermal Condensation

Principle and Applications

Thermal condensation involves the high-temperature treatment of nitrogen-rich organic precursors (typically melamine, urea, or thiourea) to form graphitic carbon nitride (g-C₃N₄) through polycondensation reactions [26]. This process creates extended π-conjugated polymeric networks characterized by strong covalent carbon-nitrogen bonds arranged in layered structures resembling graphite. The method yields a metal-free semiconductor photocatalyst with visible-light responsiveness (band gap ~2.7 eV), excellent thermal and chemical stability, and non-toxic properties [26].

Recent advances have demonstrated that modified thermal approaches, including thermal exfoliation and supramolecular pre-organization, can significantly enhance the photocatalytic performance of g-C₃N₄. Thermal exfoliation produces thinner nanosheets with increased specific surface area, while supramolecular hydrothermal synthesis creates polyhedral-nanosheet hybrid architectures with internal channels that facilitate mass transport [26]. These structural modifications lead to improved charge carrier separation and enhanced accessibility to active sites.

In application studies, g-C₃Nâ‚„ synthesized via supramolecular assembly followed by thermal condensation (HCN-II) achieved approximately 80% degradation of gallic acid within 180 minutes under visible-light irradiation, with a superior apparent rate constant (k=0.01156 minâ»Â¹) compared to thermally exfoliated samples (CN-E) [26]. Radical trapping experiments identified superoxide radicals (O₂•â») and holes (hâº) as the primary reactive species responsible for pollutant degradation.

Experimental Protocol: Supramolecular Hydrothermal Synthesis of g-C₃N₄ (HCN-II)

Procedure:

- Supramolecular Precursor Assembly: Dissolve appropriate precursors (e.g., melamine-cyanuric acid complexes) in deionized water with controlled acid addition (e.g., HCl or acetic acid) to facilitate hydrogen bonding and self-assembly [26].

- Hydrothermal Pre-organization: Transfer the solution to a Teflon-lined autoclave and heat at 120-180°C for 4-12 hours to form supramolecular aggregates with defined morphology [26].

- Recovery and Drying: Collect the resulting precipitate by filtration, wash with water and ethanol, and dry at 60°C.

- Thermal Polycondensation: Place the dried supramolecular precursor in a covered crucible and heat in a muffle furnace at 500-600°C for 2-4 hours with a ramp rate of 2-5°C/min to convert the organic precursor to g-C₃N₄ through thermal condensation [26].

- Product Collection: After natural cooling to room temperature, collect the resulting yellow g-C₃N₄ product and gently grind it into a fine powder.

Characterization:

- Structural Analysis: XRD patterns show characteristic peaks at 13.1° (100 plane) and 27.4° (002 plane) confirming the graphitic structure [26].

- Morphological Examination: SEM reveals the polyhedral-nanosheet hybrid architecture with internal channels distinctive of the HCN-II material [26].

- Textural Properties: N₂ adsorption-desorption measurements determine surface area and pore structure, with HCN-II exhibiting enhanced surface area compared to conventional g-C₃N₄ [26].

Diagram 2: Thermal condensation synthesis workflow (76 characters)

Co-precipitation

Principle and Applications

Co-precipitation is a solution-based process where multiple metal ions simultaneously precipitate from a common solution to form homogeneous composite materials [29] [30]. This method leverages the controlled addition of precipitating agents (typically hydroxides or carbonates) to initiate nucleation and growth of composite nanoparticles. The technique is particularly valuable for creating heterostructured photocatalysts with intimate contact between different semiconductor components, facilitating efficient charge separation and transfer across interfaces [29] [31].

The photocatalytic performance of co-precipitated composites has demonstrated remarkable efficiency in wastewater treatment applications. CaO/TiO₂/γ-Al₂O₃ nanocomposites prepared via one-step co-precipitation achieved 98% degradation of methylene blue dye under UV irradiation within 200 minutes, significantly outperforming individual components (γ-Al₂O₃ NPs: 45%; TiO₂/γ-Al₂O₃ NCs: 79%) [29] [30]. Similarly, CuZnAl hydrotalcite synthesized by co-precipitation showed over 90% degradation efficiency for phenol red dye under LED light irradiation when combined with H₂O₂ as an oxidant [31]. These enhancements are attributed to improved charge separation, increased surface area, and synergistic effects between the composite components.

Experimental Protocol: One-Step Co-precipitation of CaO/TiO₂/γ-Al₂O₃ Nanocomposites

Table 3: Key Reagents for Co-precipitation Synthesis

| Reagent | Function | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| γ-Al₂O₃ NPs | Support matrix & photocatalyst | 99.95% purity |

| Titanium(IV) butoxide | TiOâ‚‚ precursor | Precursor for TiOâ‚‚ nanoparticles |

| Calcium nitrate tetrahydrate | CaO precursor | Source of Ca²⺠ions |

| Sodium hydroxide | Precipitating agent | Provides OHâ» ions for precipitation |

| Ethanol | Solvent | For titanium precursor dissolution |

| Distilled Water | Solvent | Reaction medium |

Procedure:

- Suspension Preparation: Disperse 0.07 mol of γ-Al₂O₃ nanoparticles in 30 mL of distilled water in a 250 mL round-bottom flask under magnetic stirring [30].

- Titanium Precursor Addition: Mix 0.015 mol of titanium(IV) butoxide with 10 mL of ethanol and add this solution to the γ-Al₂O₃ suspension under continuous stirring [30].

- Calcium Incorporation: Add 0.015 mol of calcium nitrate tetrahydrate to the mixture and continue stirring for 1 hour to ensure homogeneous mixing [30].

- Precipitation: Slowly add 0.031 mol of sodium hydroxide dissolved in 15 mL of distilled water to the mixture while maintaining stirring at 65°C for 5 hours to facilitate complete precipitation [30].

- Product Recovery: Filter the resulting precipitate and wash repeatedly with ethanol and distilled water to remove residual ions and byproducts.

- Drying and Calcination: Dry the purified product at 60°C for 24 hours, then calcine at 500°C in air for 4 hours to obtain the final CaO/TiO₂/γ-Al₂O₃ nanocomposite [30].

Characterization:

- Structural Analysis: XRD confirms improved crystallinity and phase purity after composite formation, with characteristic peaks corresponding to γ-Al₂O₃, TiO₂ (anatase), and CaO phases [30].

- Morphological Examination: TEM and SEM analyses reveal spherical morphology with reduced particle size (8.21 ± 2.1 nm for NCs vs. 9.50 ± 1.2 nm for pure γ-Al₂O³) [30].

- Optical Properties: Photoluminescence spectroscopy shows reduced recombination of electron-hole pairs, while UV-Vis spectroscopy confirms optical absorption characteristics [30].

Diagram 3: Co-precipitation synthesis workflow (76 characters)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Photocatalyst Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Synthesis | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| H₃PMoâ‚â‚‚O₄₀·xHâ‚‚O | Mo source for hybrid oxides | Hydrothermal synthesis of MoO₃-based hybrids [27] |

| 1,2,4-Triazole | Structure-directing ligand | Forms organic-inorganic hybrid architectures [27] |

| Melamine/Cyanuric Acid | g-C₃N₄ precursors | Thermal condensation of carbon nitride [26] |

| Titanium(IV) Butoxide | TiOâ‚‚ precursor | Co-precipitation of TiOâ‚‚-containing composites [30] |

| γ-Al₂O₃ Nanoparticles | Support matrix | Enhances surface area and stability in nanocomposites [30] |

| Calcium Nitrate | CaO precursor | Alkaline component in composite photocatalysts [30] |

| Zinc Nitrate | Zn source in LDHs | Formation of ZnAl hydrotalcite-type materials [31] |

| Copper Nitrate | Cu dopant source | Enhances visible light absorption in composites [31] |

| Sodium Hydroxide | Precipitating agent | pH control and hydroxide formation in co-precipitation [30] |

| Hydrogen Peroxide | Oxidizing agent | Enhances photocatalytic degradation in application testing [31] |

| Amidodiphosphoric acid(9CI) | Amidodiphosphoric acid(9CI), CAS:27713-27-5, MF:H5NO6P2, MW:176.99 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Dipentyl phosphoramidate | Dipentyl Phosphoramidate|C10H24NO3P|305764 | Dipentyl phosphoramidate is a research chemical. It is For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

The selection of appropriate synthesis methods—hydrothermal, thermal condensation, or co-precipitation—fundamentally governs the structural, morphological, and optical properties of photocatalysts for wastewater treatment applications. Each technique offers distinct advantages: hydrothermal methods enable exquisite morphological control, thermal condensation provides access to metal-free polymeric semiconductors, and co-precipitation allows scalable production of composite materials with synergistic effects.

Recent research demonstrates that modified approaches, such as supramolecular pre-organization before thermal condensation or one-step co-precipitation of multi-component composites, yield materials with enhanced photocatalytic activities. These advances in synthesis methodology directly contribute to improved charge separation, increased surface area, and optimized reaction pathways—collectively leading to superior degradation efficiency for persistent organic pollutants in wastewater.

Future developments in photocatalytic materials will likely involve hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of multiple synthesis techniques, along with more precise control over hierarchical structures and active site engineering. Such advances will further establish photocatalysis as a viable, efficient technology for addressing the pressing global challenge of water pollution.

Application Notes

Advanced characterization techniques are pivotal in developing and optimizing photocatalysts for wastewater remediation. These tools provide critical insights into the material's crystal structure, morphology, surface properties, and optical characteristics, which collectively determine photocatalytic efficiency. The following data, synthesized from recent research, illustrates how these techniques are applied to understand and improve photocatalytic systems.

Table 1: Summary of Characterization Data from Recent Photocatalytic Studies

| Photocatalyst | XRD: Primary Crystallite Phase & Size (nm) | FESEM/TEM: Morphology | BET: Surface Area (m²/g) | UV-Vis DRS: Band Gap (eV) | Photocatalytic Performance (Degradation Efficiency) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZnS | Zinc Blende/Wurtzite [32] | Porous Nanoparticles [32] | 165 [32] | 3.3 [32] | 88% (Methylene Blue under LED) [32] |

| ZnS-ZnO nanocomposite | Mixed ZnS & ZnO phases [32] | Porous Heterostructure [32] | 35 [32] | Information missing | 55% (Methylene Blue under LED) [32] |

| ZnO (from ZnS) | Wurtzite [32] | Porous Particles [32] | 10 [32] | Information missing | 43% (Methylene Blue under LED) [32] |

| Co0.5Zn0.5Al2O4 | Spinel Oxide [33] | Information missing | Information missing | Information missing | 98.2% (Methyl Orange under UV, 50 min) [33] |

| TiO2-Clay Nanocomposite | Anatase/Rutile (P25) [3] | Information missing | 65.35 [3] | Information missing | 98% (BR46 dye under UV, 90 min) [3] |

| α-Fe2O3 (Hematite) | Rhombohedral (JCPDS 79-1741) [34] | Layered structure with Rhombohedral Nanorods [34] | Information missing | 2.3 [34] | 53% (Rhodamine 6G under Sunlight, 60 min) [34] |

| N-gZnOw (Green-synthesized ZnO) | Wurtzite [2] | Nanoparticles (Avg. size: 14.9 nm) [2] | Information missing | 2.92 [2] | 98.2% (Clomazone under Sunlight) [2] |

The data in Table 1 reveals key structure-property-performance relationships. For instance, the superior performance of porous ZnS over its ZnO and ZnS-ZnO counterparts, despite a wider band gap, underscores the decisive role of a high surface area (165 m²/g) in providing more active sites for reactions [32]. Similarly, the high efficiency of the TiO2-clay nanocomposite is linked to its increased surface area compared to pure TiO2, which enhances pollutant adsorption [3]. Band gap engineering is another critical strategy, as seen with green-synthesized ZnO (N-gZnOw) and α-Fe2O3, which have band gaps of 2.92 eV and 2.3 eV, respectively, allowing for efficient utilization of visible and solar light [34] [2].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis

Purpose: To determine the crystallographic phase, purity, and crystallite size of the photocatalyst.

Materials:

- Synthesized photocatalyst powder

- XRD instrument (e.g., Bruker D8 Advance) with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å)

- Sample holder

Method:

- Sample Preparation: Finely grind the photocatalyst powder using a mortar and pestle to ensure a homogeneous sample. Pack the powder uniformly into the sample holder to minimize preferred orientation.

- Instrument Setup: Set up the XRD instrument with the following typical parameters:

- Data Collection: Load the sample and initiate the scan. The instrument will generate a plot of intensity (counts) versus 2θ.

- Data Analysis:

- Phase Identification: Compare the obtained diffraction pattern with standard reference patterns from the International Centre for Diffraction Data (ICDD) database (e.g., JCPDS cards) [34].

- Crystallite Size Estimation: Use the Scherrer equation: ( D = (K \lambda) / (\beta \cos\theta) ), where ( D ) is the crystallite size, ( K ) is the Scherrer constant (~0.9), ( \lambda ) is the X-ray wavelength, ( \beta ) is the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the diffraction peak in radians, and ( \theta ) is the Bragg angle [32].

Protocol for Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FESEM) Analysis

Purpose: To examine the surface morphology, particle size, and architecture of the photocatalyst at the micro- and nano-scale.

Materials:

- Synthesized photocatalyst powder

- FESEM instrument (e.g., KYKY EM8000F)

- Conductive adhesive tape

- Sputter coater for gold or carbon coating

Method:

- Sample Preparation: Adhere a small amount of the photocatalyst powder onto a sample stub using conductive carbon tape. To ensure conductivity for non-metallic samples, sputter-coat the sample with a thin layer (a few nanometers) of gold or carbon [3].

- Instrument Setup: Load the sample into the FESEM chamber and evacuate to high vacuum. Select an appropriate accelerating voltage (e.g., 5-15 kV) based on the sample.

- Imaging: Navigate the stage to areas of interest and capture secondary electron (SE) images at various magnifications to assess morphology, porosity, and particle size distribution [32]. For elemental composition, energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) analysis can be performed simultaneously [33].

Protocol for BET Surface Area Analysis

Purpose: To determine the specific surface area and pore characteristics of the photocatalyst via nitrogen physisorption.

Materials:

- Synthesized photocatalyst powder

- BET surface area analyzer (e.g., Belsorp Mini II)

- Nitrogen gas (high purity)

- Sample tube

Method:

- Sample Pre-treatment: Weigh an appropriate amount of photocatalyst (typically 50-200 mg) and load it into a sample tube. Degas the sample under vacuum or flowing inert gas at an elevated temperature (e.g., 150-300°C) for several hours (e.g., 3-6 hours) to remove any adsorbed moisture and contaminants [3].

- Analysis: Transfer the degassed sample tube to the analysis port. The instrument will automatically cool the sample (usually to liquid nitrogen temperature, -196°C) and measure the volume of nitrogen gas adsorbed and desorbed at a series of relative pressures (P/P₀).

- Data Analysis:

- Surface Area: Apply the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) theory to the adsorption data in the relative pressure range of 0.05-0.3 P/Pâ‚€ to calculate the specific surface area [3] [32].

- Pore Characteristics: Use the Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) method on the desorption branch of the isotherm to determine the pore size distribution and total pore volume.

Protocol for UV-Vis Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy (UV-Vis DRS) Analysis

Purpose: To determine the optical absorption properties and band gap energy of the semiconductor photocatalyst.

Materials:

- Synthesized photocatalyst powder

- UV-Vis DRS spectrometer (e.g., Shimadzu UV-3600) equipped with an integrating sphere

- Barium sulfate (BaSOâ‚„) or Spectralon as a non-absorbing reference standard

Method:

- Sample Preparation: Pack the photocatalyst powder uniformly into a holder. For a reference measurement, fill an identical holder with the standard reference material (BaSOâ‚„).

- Baseline Correction: Place the reference standard in the sample beam and record a baseline spectrum over the desired wavelength range (e.g., 200-800 nm) [34].

- Sample Measurement: Replace the reference with the sample and record the diffuse reflectance spectrum (R).

- Data Analysis:

- Band Gap Calculation: Convert the reflectance data to the Kubelka-Munk function: ( F(R) = (1 - R)^2 / 2R ). Plot ( [F(R)h\nu]^{1/n} ) versus photon energy (hν), where ( n ) is 2 for a direct band gap semiconductor and 1/2 for an indirect one. The band gap energy (Eg) is determined by extrapolating the linear portion of the plot to the x-axis where ( [F(R)h\nu]^{1/n} = 0 ) [34] [2].

Visualization Diagrams

Char Workflow

Prop Relat

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Photocatalyst Synthesis and Characterization

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example from Context |

|---|---|---|

| Titanium Dioxide (TiOâ‚‚-P25) | Benchmark photocatalyst; often used as a base material or reference due to its mixed-phase (anatase/rutile) composition and high activity. | Used as a precursor in TiOâ‚‚-clay nanocomposites [3]. |

| Zinc Nitrate Hexahydrate | A common metal salt precursor for the synthesis of zinc-based semiconductors like ZnO and ZnS. | Zinc precursor for porous ZnS, ZnO, and ZnS-ZnO synthesis [32]. |

| Sodium Sulfide Pentahydrate | Sulfur precursor for the synthesis of metal sulfide semiconductors (e.g., ZnS). | Sulfur source for porous ZnS synthesis [32]. |

| Ferric Nitrate Nonahydrate | Iron precursor for synthesizing iron oxide photocatalysts (e.g., α-Fe₂O₃ hematite). | Iron source for α-Fe₂O₃ via sol-gel autocombustion [34]. |

| Citric Acid | Fuel in combustion synthesis methods and a common chelating/capping agent in sol-gel processes. | Used as a fuel/chelating agent in α-Fe₂O₃ synthesis [34]. |

| Clay Powder | A low-cost, natural support material that enhances adsorption and prevents nanoparticle aggregation. | Component of TiOâ‚‚-clay nanocomposite to increase surface area [3]. |

| Silicone Adhesive | Used for immobilizing photocatalyst powders onto substrates to create fixed-bed reactors for continuous flow systems. | Immobilization of TiOâ‚‚-clay composite on a plastic substrate [3]. |

| Green Tea Leaf Extract | A natural, eco-friendly source of polyphenols used as a reducing and capping agent for green synthesis of nanoparticles. | Used for the green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles [2]. |

| Dimethyl cyclohexylboronate | Dimethyl cyclohexylboronate||RUO | |

| 2-Methoxy-1,3-dithiane | 2-Methoxy-1,3-dithiane|For Research Use |