Ab Initio Computations for Inorganic Synthesis: A Practical Guide to Target Screening and Materials Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the application of ab initio computations for screening and discovering inorganic materials.

Ab Initio Computations for Inorganic Synthesis: A Practical Guide to Target Screening and Materials Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the application of ab initio computations for screening and discovering inorganic materials. Covering foundational quantum chemistry principles to advanced generative AI techniques, it explores key methodologies like Density Functional Theory (DFT) and ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) for predicting structural, electronic, and thermodynamic properties. The content addresses critical challenges such as computational scaling and configurational space exploration, while highlighting optimization strategies and validation frameworks through case studies in crystal structure prediction and industrial materials engineering. Aimed at researchers and scientists, this guide synthesizes current best practices and future directions for integrating computational screening into the inorganic synthesis pipeline.

Quantum Foundations: The Principles of Ab Initio Methods in Materials Science

Ab initio quantum chemistry methods are a class of computational techniques designed to solve the electronic Schrödinger equation from first principles, using only fundamental physical constants and the positions and number of electrons in the system as input [1]. This approach contrasts with empirical methods that rely on parameterized approximations, instead seeking to compute molecular properties directly from quantum mechanical principles. The term "ab initio" literally means "from the beginning" in Latin, reflecting the fundamental nature of these calculations. The ability to run these calculations has enabled theoretical chemists to solve a wide range of chemical problems, with their significance highlighted by the awarding of the 1998 Nobel Prize in Chemistry to John Pople and Walter Kohn for their pioneering work in this field [1].

In the context of inorganic synthesis target screening, ab initio methods provide a powerful framework for predicting material properties and stability before undertaking costly experimental synthesis. These methods can accurately predict various chemical properties including electron densities, energies, and molecular structures, making them invaluable for modern materials design and drug development research [1]. The fundamental challenge these methods address is solving the non-relativistic electronic Schrödinger equation within the Born-Oppenheimer approximation to obtain the many-electron wavefunction, which contains all information about the electronic structure of a molecular system [1].

Theoretical Foundation

The Electronic Schrödinger Equation

At the core of ab initio methods lies the time-independent, non-relativistic electronic Schrödinger equation, which for a fixed nuclear configuration takes the form:

ĤΨ = EΨ

Where Ĥ is the electronic Hamiltonian operator, Ψ is the many-electron wavefunction, and E is the total electronic energy. The Hamiltonian consists of several key terms representing the kinetic energy of electrons and the various potential energy contributions from electron-electron and electron-nuclear interactions.

The exact solution of this equation for systems with more than one electron is computationally intractable due to the correlated motion of electrons. Ab initio methods address this challenge through a systematic approach: the many-electron wavefunction is typically expressed as a linear combination of many simpler electron functions, with the dominant function being the Hartree-Fock wavefunction [1]. Each of these simpler functions is then approximated using one-electron functions (orbitals), which are in turn expanded as a linear combination of a finite set of basis functions [1].

The Hartree-Fock Method

The Hartree-Fock (HF) method represents the simplest type of ab initio electronic structure calculation [1]. In this approach, the instantaneous Coulombic electron-electron repulsion is not specifically taken into account; only its average effect (mean field) is included in the calculation [1]. The HF method is a variational procedure, meaning the obtained approximate energies are always equal to or greater than the exact energy, approaching a limiting value called the Hartree-Fock limit as the basis set size increases [1].

The key limitation of the Hartree-Fock method is its treatment of electron correlation. Because it models electrons as moving in an average field rather than instantaneously responding to each other's positions, it necessarily omits electron correlation effects. This correlation energy, typically representing 0.3-1.0% of the total energy, is nevertheless crucial for accurate prediction of many chemical properties, including reaction barriers, binding energies, and electronic excitations.

Computational Methodologies

Hierarchy ofAb InitioMethods

Ab initio methods can be organized into a systematic hierarchy based on their treatment of electron correlation and computational cost:

Hartree-Fock Methods form the foundation, providing an approximate solution that serves as the reference for more accurate methods. The HF method scales nominally as Nâ´, where N represents system size, though in practice it often scales closer to N³ through identification and neglect of extremely small integrals [1].

Post-Hartree-Fock Methods introduce increasingly sophisticated treatments of electron correlation:

- Møller-Plesset Perturbation Theory: A hierarchical approach where MP2 scales as Nâ´, MP3 as Nâ¶, and MP4 as Nâ· [1]

- Coupled Cluster Methods: CCSD scales as Nâ¶, while CCSD(T) adds non-iterative triple excitations scaling as Nâ· [1]

- Configuration Interaction: Approaches the exact solution with Full CI but becomes computationally prohibitive for all but the smallest systems

Multi-Reference Methods address cases where a single determinant reference is inadequate, such as bond breaking processes, using multi-configurational self-consistent field (MCSCF) approaches as starting points for correlation treatments [1].

Accuracy and Computational Scaling

The computational cost of ab initio methods is a critical consideration when selecting an appropriate method for a given problem. The table below summarizes the scaling behavior and typical applications of major ab initio methods:

Table 1: Computational Scaling and Applications of Ab Initio Methods

| Method | Computational Scaling | Accuracy | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hartree-Fock | N³ - Nⴠ| Qualitative | Initial geometry optimization, basis for correlated methods |

| MP2 | Nâµ | Semi-quantitative | Non-covalent interactions, preliminary screening |

| CCSD | Nⶠ| Quantitative | Accurate energy calculations, molecular properties |

| CCSD(T) | Nâ· | Near-chemical accuracy | Benchmark calculations, final property evaluation |

| Full CI | Factorial | Exact (within basis) | Benchmarking, very small systems |

For context, doubling the system size leads to a 16-fold increase in computation time for HF methods, and a 128-fold increase for CCSD(T) calculations. This scaling behavior presents significant challenges for applying high-accuracy methods to large systems, though modern advances in computer science and technology are gradually alleviating these constraints [1].

Advanced Applications in Materials Design

Generative Models for Inverse Materials Design

Recent advances have integrated ab initio methods with machine learning approaches for inverse materials design. MatterGen, a diffusion-based generative model, represents a significant advancement in this area, capable of generating stable, diverse inorganic materials across the periodic table that can be fine-tuned toward specific property constraints [2]. This approach addresses the fundamental limitation of traditional screening methods, which are constrained by the number of known materials in databases.

Unlike traditional forward approaches that screen existing materials databases, generative models like MatterGen directly propose new stable crystals with desired properties. The model employs a customized diffusion process that generates crystal structures by gradually refining atom types, coordinates, and the periodic lattice, respecting the unique symmetries and periodic nature of crystalline materials [2]. After fine-tuning, MatterGen can successfully generate stable, novel materials with desired chemistry, symmetry, and target mechanical, electronic, and magnetic properties [2].

Performance and Validation

In benchmark tests, structures produced by MatterGen demonstrated substantial improvements over previous generative models:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Generative Materials Design Models

| Performance Metric | Previous State-of-the-Art | MatterGen | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| New and stable materials | Baseline | >2× higher likelihood | >2× |

| Distance to local energy minimum | Baseline | >10× closer | >10× |

| Structure uniqueness | Varies by method | 52-100% | Significant improvement |

| Rediscovery of experimental structures | Limited | >2,000 verified ICSD structures | Substantial increase |

As proof of concept, one generated structure was synthesized experimentally, with measured property values within 20% of the target [2]. This validation underscores the potential of combining ab initio methods with generative models to accelerate materials discovery for applications in energy storage, catalysis, carbon capture, and other technologically critical areas [2].

Practical Implementation and Protocols

Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Materials Screening

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Ab Initio Materials Screening

| Research Reagent | Function | Application in Materials Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Computes electronic structure using functionals for exchange-correlation energy | Primary workhorse for geometry optimization and property prediction |

| Machine Learning Force Fields (MLFFs) | Accelerates molecular dynamics simulations using ML-predicted energies/forces | Extended timescale simulations beyond DFT limitations |

| Coupled Cluster Methods | High-accuracy treatment of electron correlation | Benchmark calculations and final validation of promising candidates |

| Materials Databases (MP, ICSD, Alexandria) | Curated repositories of computed and experimental structures | Training data for ML models and validation of generated structures |

| Structure Matchers | Algorithmic comparison of crystal structures | Identification of novel materials and detection of duplicates |

Workflow for Inorganic Synthesis Target Screening

A robust computational workflow for inorganic synthesis target screening integrates multiple ab initio approaches:

Step 1: Initial Generation - Employ generative models (e.g., MatterGen) or traditional methods (random structure search, substitution) to create candidate structures with desired chemical composition and symmetry constraints [2].

Step 2: Stability Assessment - Perform DFT calculations to evaluate formation energy and distance to convex hull, with structures within 0.1 eV per atom considered promising candidates [2].

Step 3: Property Evaluation - Compute target properties (mechanical, electronic, magnetic) using appropriate levels of theory, with higher-level methods (CCSD(T), QMC) reserved for final candidates.

Step 4: Synthesizability Analysis - Compare predicted structures with experimental databases (ICSD) to identify analogous synthetic routes and assess feasibility [2].

This integrated approach enables researchers to efficiently navigate the vast chemical space of potential inorganic materials, focusing experimental resources on the most promising candidates predicted to exhibit target properties while maintaining stability.

Ab initio quantum chemistry methods provide a fundamental framework for solving the electronic Schrödinger equation from first principles, enabling the prediction of molecular and materials properties with increasing accuracy. The systematic hierarchy of methods—from Hartree-Fock to coupled cluster theory—offers a balanced approach to navigating the trade-off between computational cost and accuracy. Recent integrations with generative models represent a paradigm shift in materials design, moving beyond database screening to direct generation of novel materials with targeted properties. As computational power continues to grow and algorithms become more sophisticated, these approaches will play an increasingly crucial role in accelerating the discovery and development of advanced materials for energy, electronics, and pharmaceutical applications. The successful experimental validation of computationally predicted structures underscores the maturity of these methods and their growing impact on materials science and drug development research.

Ab initio computational methods are indispensable in modern materials science and drug development, providing a quantum mechanical framework for predicting the properties and synthesizability of novel compounds. For research focused on inorganic synthesis target screening, three methodological classes form the foundational toolkit: Hartree-Fock (HF), Post-Hartree-Fock, and Density Functional Theory (DFT). The Hartree-Fock method offers a fundamental starting point by approximating the many-electron wave function, but neglects electron correlation effects crucial for accurate predictions. Post-Hartree-Fock methods systematically correct this limitation, while DFT approaches the electron correlation problem through electron density functionals, offering a different balance of accuracy and computational cost. Understanding the capabilities, limitations, and appropriate application domains of each class is essential for designing efficient computational screening pipelines that reliably identify synthetically accessible inorganic materials. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of these core methodologies, with specific emphasis on their implementation and performance in predicting stability and synthesizability for inorganic compounds.

Theoretical Foundations

Hartree-Fock Method

The Hartree-Fock method represents the historical cornerstone of quantum chemistry, providing both a conceptual framework and practical algorithm for approximating solutions to the many-electron Schrödinger equation. The fundamental approximation in HF theory is that the complex N-electron wavefunction can be represented by a single Slater determinant of one-electron wavefunctions (spin-orbitals) [3] [4]. This antisymmetrized product automatically satisfies the Pauli exclusion principle and incorporates exchange correlation between electrons of parallel spin, but treats electrons as moving independently in an average field, neglecting dynamic electron correlation effects [4].

The HF approach employs the variational principle to optimize these orbitals, leading to the derivation of the Fock operator, an effective one-electron Hamiltonian [3]. The nonlinear nature of these equations necessitates an iterative solution, giving rise to the alternative name Self-Consistent Field (SCF) method [3] [4]. In this procedure, an initial guess at the molecular orbitals is used to construct the Fock operator, whose eigenfunctions then become improved orbitals for the next iteration. This cycle continues until convergence criteria are satisfied, indicating a self-consistent solution has been reached [4].

The HF method makes several critical simplifying assumptions [3]:

- The Born-Oppenheimer approximation is inherently assumed, separating electronic and nuclear motions.

- Relativistic effects are typically completely neglected.

- The solution is expanded in a finite basis set of orthogonal functions.

- The mean-field approximation is applied, replacing instantaneous electron-electron repulsions with an average interaction.

While HF typically recovers 99% of the total energy, the missing electron correlation energy (often 1% of total energy but potentially large relative to chemical bonding energies) severely limits its predictive accuracy for molecular properties, reaction energies, and bonding descriptions [5]. This limitation motivates the development of more advanced methods.

Post-Hartree-Fock Methods

Post-Hartree-Fock methods comprise a family of electronic structure techniques designed to recover the electron correlation energy missing in the Hartree-Fock approximation. These methods can be broadly categorized into two philosophical approaches: those based on wavefunction expansion and those employing many-body perturbation theory [6].

Configuration Interaction (CI) methods expand the exact wavefunction as a linear combination of Slater determinants, including excited configurations beyond the HF reference [5]:

[

\Psi{\text{CI}} = c0 \Psi0 + \sum{i,a}ci^a \Psii^a + \sum{i

where (\Psi0) is the HF reference determinant, (\Psii^a) are singly-excited determinants, (\Psi_{ij}^{ab}) are doubly-excited determinants, etc. While conceptually straightforward and variational, CI methods suffer from size-inconsistency when truncated, meaning they do not scale properly with system size [5].

Møller-Plesset Perturbation Theory treats electron correlation as a perturbation to the HF Hamiltonian. The second-order correction (MP2) provides the most popular variant, capturing substantial correlation energy at relatively low computational cost [6]. MP methods are size-consistent but non-variational.

Coupled Cluster (CC) methods employ an exponential ansatz for the wavefunction ((\Psi{\text{CC}} = e^T \Psi0)) that ensures size-consistency [5]. The cluster operator (T) generates all excitations from the reference determinant. The CCSD(T) method, which includes singles, doubles, and a perturbative treatment of triples, is often called the "gold standard" of quantum chemistry for its exceptional accuracy, though it comes with high computational cost.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Post-Hartree-Fock Methods

| Method | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations | Scaling |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MP2 | 2nd-order perturbation theory | Size-consistent, relatively inexpensive | Can overestimate correlation; poor for open-shell systems | O(Nâµ) |

| CISD | Configuration Interaction with Singles/Doubles | Variational, improves upon HF | Not size-consistent | O(Nâ¶) |

| CCSD | Coupled Cluster Singles/Doubles | Size-consistent, high accuracy | Non-variational, expensive | O(Nâ¶) |

| CCSD(T) | CCSD with perturbative Triples | "Gold standard" accuracy | Very expensive | O(Nâ·) |

| CASSCF | Multiconfigurational self-consistent field | Handles static correlation | Choice of active space is non-trivial | Depends on active space |

Density Functional Theory

Density Functional Theory represents a paradigm shift from wavefunction-based methods, using the electron density as the fundamental variable rather than the many-electron wavefunction [7]. The theoretical foundation rests on the Hohenberg-Kohn theorems, which establish that [7]:

- The ground-state electron density uniquely determines the external potential and thus all properties of the system.

- A universal functional for the energy exists, and the exact ground-state density minimizes this functional.

The practical implementation of DFT is primarily achieved through the Kohn-Sham scheme, which introduces a fictitious system of non-interacting electrons that reproduces the same density as the real interacting system [7]. This approach decomposes the total energy as:

[ E{\text{DFT}} = EN + ET + EV + E{\text{Coul}} + E{\text{XC}} ]

where (EN) is nuclear-nuclear repulsion, (ET) is the kinetic energy of non-interacting electrons, (EV) is nuclear-electron attraction, (E{\text{Coul}}) is classical electron-electron repulsion, and (E_{\text{XC}}) is the exchange-correlation energy that contains all quantum mechanical and non-classical effects [8].

The accuracy of DFT calculations depends almost entirely on the approximation used for the exchange-correlation functional. These approximations form a hierarchy of increasing complexity and accuracy [8]:

- Local Density Approximation (LDA): Uses only the local electron density, derived from the uniform electron gas.

- Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA): Incorporates both the density and its gradient (e.g., PBE, BLYP).

- Meta-GGA: Adds the kinetic energy density for improved accuracy.

- Hybrid Functionals: Mix exact Hartree-Fock exchange with DFT exchange-correlation (e.g., B3LYP, PBE0).

Table 2: Common DFT Functionals and Their Components

| Functional | Type | Exchange | Correlation | HF Mixing | Typical Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SVWN | LDA | Slater | VWN | 0% | Solid state physics |

| BLYP | GGA | Becke88 | LYP | 0% | Molecular properties |

| PBE | GGA | PBE | PBE | 0% | Materials science |

| B3LYP | Hybrid | Becke88 + Slater | LYP + VWN | 20% | General purpose chemistry |

| PBE0 | Hybrid | PBE | PBE | 25% | Solid state & molecular |

| HSE | Hybrid | Screened PBE | PBE | 25% (short-range) | Band gaps, periodic systems |

Computational Workflow in Inorganic Synthesis Screening

The application of ab initio methods to inorganic synthesis screening follows a systematic workflow that integrates computational predictions with experimental validation. This pipeline has been successfully implemented in autonomous materials discovery platforms such as the A-Lab [9].

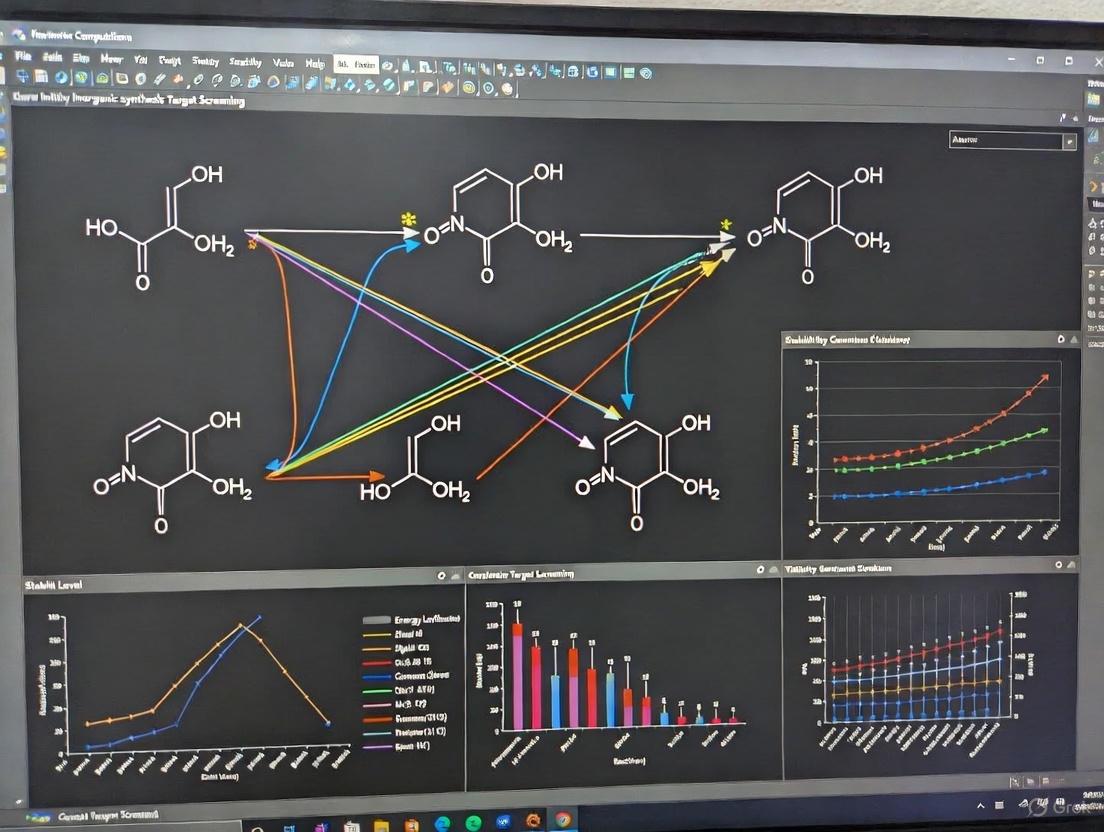

Diagram 1: Materials Discovery Workflow

The screening process begins with large-scale ab initio phase-stability calculations from resources like the Materials Project, which employs DFT to identify potentially stable compounds [9]. These computational predictions provide the initial target list, but thermodynamic stability alone is insufficient to guarantee synthesizability. For example, the A-Lab successfully realized 41 of 58 target compounds identified through such computational screening, with the failures attributed to kinetic barriers, precursor volatility, and other non-thermodynamic factors [9].

Machine learning models like SynthNN have been developed specifically to address the synthesizability prediction challenge [10]. These models leverage the entire space of known inorganic compositions and can achieve 7× higher precision in identifying synthesizable materials compared to using DFT-calculated formation energies alone [10]. Remarkably, without explicit programming of chemical principles, such models learn concepts of charge-balancing, chemical family relationships, and ionicity directly from the data distribution of known materials [10].

When initial synthesis attempts fail, active learning closes the loop by proposing improved recipes. The ARROWS3 algorithm integrates ab initio computed reaction energies with observed synthesis outcomes to predict optimal solid-state reaction pathways, avoiding intermediates with small driving forces to form the target material [9].

Comparative Analysis of Methodological Performance

Accuracy and Computational Cost

The choice between methodological classes involves balancing accuracy requirements against computational constraints, particularly important for high-throughput screening where thousands of compounds may need evaluation.

Table 3: Methodological Comparison for Synthesis Screening

| Method | Electron Correlation Treatment | Typical Formation Energy Error | Scalability | Synthesizability Prediction Utility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hartree-Fock | Exchange only (neglects correlation) | 50-100% (large overestimation) | O(N³-Nâ´) | Limited - misses key stabilization energies |

| DFT (GGA) | Approximate exchange-correlation functional | 5-15% (under/overestimation) | O(N³) | Good - balances accuracy and speed for screening |

| DFT (Hybrid) | Mixed exact exchange + DFT correlation | 3-10% (generally improved) | O(Nâ´) | Very good - improved thermodynamic accuracy |

| MP2 | Perturbative treatment of correlation | 2-5% (can overbind) | O(Nâµ) | Limited use - scaling prohibitive for solids |

| CCSD(T) | Nearly exact for given basis set | ~1% (chemical accuracy) | O(Nâ·) | Reference values only - not for screening |

Hartree-Fock severely overestimates formation energies due to its incomplete treatment of electron correlation, making it poorly suited for quantitative synthesis prediction [5]. However, its qualitative descriptions and relatively low computational cost maintain its utility for initial assessments and as a starting point for more accurate methods.

Standard DFT functionals (GGA) provide the best balance for initial high-throughput screening, recovering most correlation energy at reasonable computational expense. The typical errors of 5-15% in formation energies are often acceptable for identifying promising candidates from large chemical spaces [7] [8].

Hybrid functionals like B3LYP and PBE0 offer improved accuracy by incorporating exact HF exchange, correcting DFT's tendency to over-delocalize electrons. However, their increased computational cost (typically 3-5× standard DFT) limits application in the highest-throughput screening scenarios [8].

Wavefunction-based post-HF methods, while potentially highly accurate, have computational scaling that prohibits application to large systems or high-throughput screening. Their primary role in synthesis research is providing benchmark accuracy for smaller model systems to validate and develop more efficient methods [5].

Practical Considerations for Inorganic Materials

The performance of these methodological classes shows significant dependence on the specific class of inorganic material under investigation. Strongly correlated systems, including transition metal oxides and f-electron materials, present particular challenges for standard DFT functionals [7]. These systems often require advanced functionals (e.g., DFT+U) or multiconfigurational wavefunction methods for proper description.

For solid-state materials screening, the choice of basis set differs from molecular calculations. Plane-wave basis sets are typically employed for periodic systems, with kinetic energy cutoffs determining quality. Pseudopotentials replace core electrons to improve efficiency, with the projector augmented-wave (PAW) method providing high accuracy [7].

The A-Lab's demonstration that 71% of computationally predicted stable compounds could be synthesized validates the DFT-based screening approach, while the 29% failure rate highlights the role of kinetic factors not captured by thermodynamic calculations [9]. This underscores the importance of integrating computational stability assessments with data-driven synthesizability models and experimental validation.

Experimental Protocols & Research Toolkit

High-Throughput Screening Protocol

A robust computational screening protocol for inorganic synthesis targets involves multiple methodological stages:

Initial Phase Stability Screening

- Method: DFT with GGA functional (PBE)

- Basis: Plane-wave with medium cutoff (500 eV)

- Software: VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, ABINIT

- Data Source: Materials Project formation energies

- Success Criteria: Formation energy < 0 meV/atom (stable) or < 50 meV/atom (metastable)

Synthesizability Assessment

- Input: Chemical composition only (no structure required)

- Model: SynthNN or similar ML classifier

- Training Data: ICSD known materials + generated negatives

- Threshold: >0.5 probability of synthesizability [10]

Refined Stability & Property Assessment

- Method: Hybrid DFT (PBE0, HSE06)

- Focus: Electronic structure, band gaps, defect energetics

- Validation: Comparison to available experimental data

Synthesis Route Planning

- Precursor Selection: Natural language processing of literature data

- Temperature Prediction: ML models trained on historical synthesis data

- Pathway Optimization: Active learning with thermodynamic constraints [9]

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Computational Research Toolkit for Inorganic Synthesis Screening

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| VASP | Software | DFT with PAW pseudopotentials | Phase stability, electronic structure |

| Gaussian | Software | Molecular & solid-state DFT/HF | Molecular precursors, clusters |

| Materials Project | Database | DFT-calculated material properties | Initial target identification |

| ICSD | Database | Experimental crystal structures | Training synthesizability models |

| AFLOW | Database | High-throughput computational data | Structure-property relationships |

| SynthNN | ML Model | Synthesizability prediction | Filtering likely accessible materials |

| atom2vec | Algorithm | Composition representation learning | Feature generation for ML models |

| ARROWS3 | Algorithm | Reaction pathway optimization | Proposing improved synthesis recipes |

| Phenylephrone hydrochloride | Phenylephrone hydrochloride, CAS:94240-17-2, MF:C9H12ClNO2, MW:201.65 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Fraxiresinol 1-O-glucoside | Fraxiresinol 1-O-glucoside, MF:C27H34O13, MW:566.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Hartree-Fock, Post-Hartree-Fock, and Density Functional Theory represent complementary methodological approaches with distinct roles in computational screening for inorganic synthesis. HF provides the conceptual foundation but limited quantitative accuracy. Post-HF methods offer high accuracy but prohibitive computational cost for materials-scale screening. DFT occupies the practical middle ground, enabling high-throughput thermodynamic assessment when appropriately employed with understanding of its limitations and systematic errors.

The most effective screening strategies integrate these electronic structure methods with machine learning synthesizability predictors and automated experimental validation. The demonstrated success of autonomous laboratories like the A-Lab, achieving 71% synthesis success rates for computationally predicted targets, validates this integrated approach [9]. Future advancements will likely focus on improving DFT functionals for challenging materials classes, developing more accurate synthesizability predictors, and further closing the loop between computation and automated synthesis. For researchers engaged in inorganic materials discovery, a sophisticated understanding of each methodological class's capabilities, appropriate application domains, and limitations remains essential for designing efficient and successful screening pipelines.

The pursuit of novel inorganic materials for applications ranging from drug development to energy storage hinges on computational screening to identify promising synthetic targets. This process relies on electronic structure methods to predict properties from first principles, yet researchers face a fundamental trilemma: a delicate balance between computational cost, system size, and accuracy. Traditional quantum chemistry methods exhibit steep computational scaling, creating a persistent tension between the need for high precision in predicting molecular properties and the practical constraints of finite computational resources [11]. For decades, this tension has limited the application of high-accuracy methods to small model systems, creating a critical bottleneck in the reliable prediction of functional materials.

The emergence of machine learning (ML) and generative artificial intelligence promises to reshape this landscape by offering pathways to circumvent traditional scaling limitations [12]. However, these new approaches introduce their own challenges regarding data requirements, transferability, and integration with physical principles. This technical guide examines the current state of computational scaling and accuracy, providing researchers with a framework for selecting appropriate methodologies for inorganic synthesis target screening within a broader thesis on ab initio computations.

Fundamental Accuracy Hierarchies in Electronic Structure Methods

The Quantum Chemical Accuracy Landscape

Electronic structure methods form a hierarchical landscape where increasing accuracy typically comes at the cost of exponentially growing computational demands. Understanding this hierarchy is essential for making informed methodological choices in screening pipelines.

Table: Accuracy and Scaling of Electronic Structure Methods

| Method | Theoretical Foundation | Computational Scaling | Typical Accuracy (Energy Error) | Applicable System Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schrödinger Equation | First Principles | Exponential | Exact (Theoretical) | Few electrons [13] |

| Coupled Cluster (CCSD(T)) | Wavefunction Theory | O(Nâ·) | < 1 kJ/mol ("Gold Standard") [13] | ~10 atoms [11] |

| Density Functional Theory | Electron Density | O(N³) | 3-30 kcal/mol (Varies by functional) [14] | Hundreds of atoms [11] |

| Machine Learning Potentials | Learned Representations | ~O(N) | Can approach CCSD(T) with sufficient data [11] | Thousands of atoms [11] |

The Coupled Cluster (CCSD(T)) method, often considered the "gold standard" of quantum chemistry, provides exceptional accuracy but with prohibitive O(Nâ·) scaling, where N represents system size [11]. This effectively limits its direct application to systems of approximately 10 atoms, far smaller than most biologically relevant molecules or inorganic synthesis targets. In contrast, Density Functional Theory (DFT) offers more favorable O(N³) scaling, enabling the study of hundreds of atoms, but its accuracy is fundamentally limited by the approximate nature of exchange-correlation functionals [14]. The error range of 3-30 kcal/mol for most DFT functionals frequently exceeds the threshold for reliable predictions in areas such as binding affinity, where errors of just 1 kcal/mol can lead to erroneous conclusions about relative binding affinities [15].

Accuracy Benchmarks for Critical Systems

Robust benchmarking is essential for establishing the reliability of computational methods, particularly for systems mimicking real-world applications. The QUID (QUantum Interacting Dimer) benchmark framework addresses this need by providing high-accuracy interaction energies for 170 non-covalent systems modeling ligand-pocket motifs [15]. By establishing agreement of 0.5 kcal/mol between complementary Coupled Cluster and Quantum Monte Carlo methods—creating a "platinum standard"—QUID enables rigorous assessment of approximate methods for biologically relevant interactions [15].

For inorganic materials discovery, thermodynamic stability alone proves insufficient for predicting synthesizability. Traditional approaches using formation energy (within 0.1 eV/atom of the convex hull) achieve only 74.1% accuracy in synthesizability prediction, while kinetic stability assessments via phonon spectrum analysis reach approximately 82.2% accuracy [16]. These limitations highlight the critical need for methods that incorporate synthetic feasibility directly into the screening pipeline.

Machine Learning Approaches for Scaling High-Accuracy Methods

Neural Network Architectures for Electronic Structure

Machine learning offers promising pathways to transcend traditional accuracy-scaling tradeoffs by learning complex relationships from high-quality reference data. Several innovative architectures demonstrate the potential to preserve accuracy while dramatically improving computational efficiency:

MEHnet (Multi-task Electronic Hamiltonian network): This neural network architecture utilizes an E(3)-equivariant graph neural network where nodes represent atoms and edges represent bonds. After training on CCSD(T) data, MEHnet can predict multiple electronic properties—including dipole moments, electronic polarizability, and optical excitation gaps—from a single model while maintaining CCSD(T)-level accuracy [11].

Lookahead Variational Algorithm (LAVA): This optimization approach systematically translates increased model size and computational resources into improved energy accuracy for neural network wavefunctions. LAVA has demonstrated the ability to achieve sub-chemical accuracy (1 kJ/mol) across a broad range of molecules, including challenging systems like the nitrogen dimer potential energy curve [13].

Skala Functional: A machine-learned density functional that employs meta-GGA ingredients combined with learned nonlocal features of the electron density. Skala reaches hybrid-DFT level accuracy while maintaining computational costs significantly lower than standard hybrid functionals (approximately 10% of the cost) [14].

Generative Models for Inverse Materials Design

Generative models represent a paradigm shift in materials discovery by directly proposing novel structures that satisfy property constraints, moving beyond traditional screening approaches:

MatterGen: A diffusion-based generative model that creates stable, diverse inorganic materials across the periodic table. MatterGen more than doubles the percentage of generated stable, unique, and new materials compared to previous approaches and generates structures that are more than ten times closer to their DFT-relaxed structures [2].

Crystal Synthesis Large Language Models (CSLLM): This framework utilizes three specialized LLMs to predict synthesizability (98.6% accuracy), synthetic methods (91.0% accuracy), and suitable precursors for 3D crystal structures, significantly outperforming traditional thermodynamic and kinetic stability assessments [16].

Table: Performance Comparison of Generative Materials Design Approaches

| Method | Type | Stability Rate | Novelty Rate | Property Conditioning | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MatterGen [2] | Diffusion Model | 78% (within 0.1 eV/atom of hull) | 61% new structures | Chemistry, symmetry, mechanical/electronic/magnetic properties | Unified generation of atom types, coordinates, and lattice |

| CSLLM [16] | Large Language Model | 98.6% synthesizability accuracy | N/A (synthesizability prediction) | Synthetic method, precursors | Text representation of crystal structures |

| CDVAE [2] | Variational Autoencoder | Lower than MatterGen | Lower than MatterGen | Limited property set | Previous state-of-the-art |

| Random Enumeration [17] | Baseline | Lower stability | Lower novelty | Limited | Traditional baseline |

| Ion Exchange [17] | Data-driven | High stability | Lower novelty (resembles known compounds) | Limited | Traditional baseline |

Experimental Protocols for High-Accuracy Computational Screening

Multi-Task Electronic Structure Learning Protocol

The MEHnet framework demonstrates a protocol for extending CCSD(T) accuracy to larger systems [11]:

Reference Data Generation: Perform CCSD(T) calculations on diverse small molecules (typically 10-20 atoms) to create training data. This initial step is computationally expensive but provides the essential accuracy foundation.

Architecture Selection: Implement an E(3)-equivariant graph neural network that respects physical symmetries. The graph structure should represent atoms as nodes and bonds as edges, with customized algorithms that incorporate physics principles directly into the model.

Multi-Task Training: Train a single model to predict multiple electronic properties simultaneously, including total energy, dipole and quadrupole moments, electronic polarizability, and optical excitation gaps. This approach maximizes information extraction from limited training data.

Generalization Testing: Evaluate the trained model on progressively larger molecules than those included in the training set, assessing both stability of predictions and retention of accuracy across system sizes.

Property Prediction: Deploy the trained model to predict properties of hypothetical materials or previously uncharacterized molecules, enabling high-throughput screening with CCSD(T)-level accuracy.

Generative Materials Design and Validation Workflow

The MatterGen pipeline provides a robust protocol for inverse design of inorganic materials [2]:

Dataset Curation: Compile a diverse set of stable crystal structures (e.g., 607,683 structures from Materials Project and Alexandria datasets) with consistent DFT calculations.

Diffusion Process: Implement a customized diffusion process that separately corrupts and refines atom types, coordinates, and periodic lattice, with physically motivated noise distributions for each component.

Base Model Pretraining: Train the diffusion model to generate stable, diverse materials without specific property constraints, focusing on structural stability and diversity.

Adapter Fine-tuning: Introduce tunable adapter modules for specific property constraints (chemical composition, symmetry, electronic properties), enabling efficient adaptation to multiple design objectives without retraining the entire model.

Stability Validation: Assess generated structures through DFT relaxation, evaluating energy above the convex hull (targeting <0.1 eV/atom) and structural match to relaxed configurations (RMSD <0.076 Ã…).

Synthesizability Assessment: Apply specialized models (e.g., CSLLM) to predict synthesizability and appropriate synthetic routes for the most promising candidates [16].

Workflow Visualization

The diagram above illustrates the integrated computational screening workflow, highlighting how different methodological approaches combine to form a comprehensive pipeline for materials discovery. The process begins with reference data generation using high-accuracy methods, proceeds through model training and structure generation, and culminates in property prediction and stability assessment before experimental validation.

Critical Limitations and Failure Modes

Despite promising advances, significant limitations and failure modes persist in computational approaches, necessitating careful methodological validation.

Neural Scaling Law Limitations

Recent research challenges the assumption that scaling model size and training data alone will yield universal accuracy in quantum chemistry. Studies demonstrate that neural network models trained exclusively on stable molecular structures fail dramatically to reproduce bond dissociation curves, even for simple diatomic molecules like Hâ‚‚ [18] [19]. Crucially, even the largest foundation models trained on datasets exceeding 101 million structures fail to reproduce the trivial repulsive energy curve of two bare protons, revealing a fundamental failure to learn basic Coulomb's law [18]. These results suggest that current large-scale models function primarily as data-driven interpolators rather than achieving true physical generalization.

Data Diversity and Representation Challenges

The performance of machine learning approaches remains heavily dependent on the diversity and quality of training data. Models trained on equilibrium geometries show limited transferability to non-equilibrium configurations, such as those encountered in transition states or dissociation pathways [18]. Additionally, representing crystalline materials for machine learning presents unique challenges compared to molecular systems, with available data (10âµ-10ⶠstructures) being substantially smaller than for organic molecules (10â¸-10â¹) [16]. Developing effective text representations for crystal structures, analogous to SMILES notation for molecules, remains an active research area critical for leveraging large language models in materials science [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for Electronic Structure Research

| Tool/Category | Function | Key Features | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Accuracy Reference Methods | Generate training data and benchmarks | Near-exact solutions to Schrödinger equation | CCSD(T) [11], Quantum Monte Carlo [15], LAVA [13] |

| Machine-Learned Force Fields | Accelerate molecular dynamics and property prediction | Near-quantum accuracy with molecular mechanics cost | MEHnet [11], Universal interatomic potentials [17] |

| Generative Models | Inverse design of novel materials | Direct generation of structures satisfying property constraints | MatterGen [2], CDVAE [2], DiffCSP [2] |

| Synthesizability Predictors | Assess synthetic feasibility of predicted structures | Predict synthesis routes and precursors beyond thermodynamic stability | CSLLM [16], SynthNN [16] |

| Benchmark Datasets | Method validation and comparison | High-quality reference data for diverse chemical systems | QUID [15], W4-17 [14], Alex-MP-20 [2] |

| 13,14-Dihydro-15-keto-PGE2 | 13,14-Dihydro-15-keto-PGE2|High Purity | Explore 13,14-Dihydro-15-keto-PGE2, a key PGE2 metabolite for GI and cancer research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Acth (1-17) tfa | Acth (1-17) tfa, MF:C97H146F3N29O25S, MW:2207.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The field of computational materials discovery stands at an inflection point, with machine learning approaches beginning to transcend traditional accuracy-cost tradeoffs. The integration of high-accuracy quantum chemistry with scalable neural network architectures now enables the targeting of CCSD(T)-level accuracy for systems of thousands of atoms [11], while generative models dramatically expand the explorable materials space beyond known compounds [2]. However, persistent challenges in generalization, physical consistency, and synthesizability prediction necessitate careful methodology selection and validation.

For research focused on ab initio computations for inorganic synthesis target screening, a hybrid approach emerges as most promising: leveraging machine learning potentials trained on high-accuracy reference data for property prediction, complemented by generative models for structural discovery and specialized synthesizability predictors to prioritize experimental targets. This integrated framework promises to accelerate the discovery of functional inorganic materials while ensuring computational predictions remain grounded in physical reality and synthetic feasibility.

As the field advances, the development of more robust benchmarks—particularly for challenging scenarios like bond dissociation, transition states, and non-equilibrium configurations—will be essential for validating new methodologies. The ultimate goal remains a comprehensive computational framework that seamlessly integrates accuracy, scalability, and synthetic accessibility to transform materials discovery from serendipitous observation to predictive design.

Linear Scaling Approaches and Density Fitting for Large System Analysis

The discovery and synthesis of novel inorganic materials represent a cornerstone for advancements in various technological domains. Modern approaches leverage ab initio computations—quantum chemical methods based on first principles—to screen for promising candidates with targeted properties before experimental realization [1]. These computations use only fundamental physical constants and the positions of atoms and electrons as input, enabling the prediction of material stability, electronic structure, and functional properties with high accuracy. However, conventional ab initio methods, such as those employing plane-wave bases, typically exhibit a computational scaling of O(N³) with system size (N), rendering the direct simulation of large or complex systems prohibitively expensive [20]. This presents a significant bottleneck for the high-throughput screening required for effective materials discovery, as seen in research targeting novel dielectrics and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) [21] [22].

To overcome this barrier, linear scaling approaches [O(N)] and density fitting (also known as resolution-of-the-identity) techniques have been developed. These methods exploit the "nearsightedness" of electronic interactions in many physical systems—the principle that the electronic properties at one point depend primarily on the immediate environment in insulating and metallic systems at finite temperatures [20]. By focusing on localized electronic descriptors and approximating electron interaction integrals, these strategies drastically reduce the computational cost of ab initio calculations, enabling the treatment of systems containing hundreds of atoms or thousands of basis functions on modest computational hardware [23]. Their integration is crucial for bridging the gap between computational prediction and experimental synthesis, as powerfully demonstrated by autonomous research platforms like the A-Lab, which successfully synthesized 41 novel inorganic compounds over 17 days by leveraging computations, historical data, and active learning [9].

Theoretical Foundations of Linear Scaling and Density Fitting

The Principle of "Nearsightedness" and its Implications

The theoretical justification for linear scaling methods rests on the concept of "nearsightedness" in quantum mechanics. Introduced by Kohn, this principle posits that in many-electron systems at finite temperatures, and particularly in insulators, local electronic properties—such as the density matrix—decay exponentially with distance [20]. This physical insight means that the electronic structure in one region of a large system is largely independent of the distant environment. Consequently, it is possible to partition the problem into smaller, computationally manageable segments that can be solved with near-independence. This locality is rigorously established for insulators, where the Wannier functions (the Fourier transforms of Bloch functions) are exponentially localized [20]. In metals, achieving strict locality is more challenging due to the presence of delocalized states at the Fermi surface; however, at non-zero temperatures, the smearing of the Fermi surface restores exponential decay to the density matrix, making linear scaling approaches feasible [20].

Fundamental Algorithmic Shifts

Conventional O(N³) scaling methods directly compute the delocalized eigenstates of the Hamiltonian, requiring each state to be orthogonal to all others—an operation whose cost scales cubically with system size. Linear scaling methods bypass this by reformulating the problem in terms of localized functions or the density matrix directly.

- Density Matrix Minimization: Instead of solving for eigenstates, these methods directly minimize the total energy with respect to the density matrix. Because the density matrix in real space is sparse for insulating systems, operations like matrix multiplication and trace evaluation can be performed in O(N) time [20].

- Localized Wannier Orbital Methods: These approaches perform unitary transformations on the occupied eigenstates to generate a set of localized, Wannier-like functions. The equations defining each function are local to a specific region, and the functions themselves are optimized subject to local constraints [20].

- Divide and Conquer Method: This technique physically divides the large system into smaller, overlapping subsystems. The electronic structure is solved self-consistently for each subsystem, and the results are patched together to reconstruct the total electron density and energy of the full system [20].

Density Fitting as a Rank-Reduction Technique

Density fitting (DF) is a powerful companion technique that reduces the formal scaling of integral evaluation. It addresses the computational bottleneck associated with the electron repulsion integrals (ERIs)—four-index tensors that describe the Coulomb interaction between electron densities. The storage and manipulation of these integrals formally scale as O(Nâ´). DF, also known as the resolution-of-the-identity approximation, reduces this burden by expressing the product of two basis functions (an "orbital pair density") as a linear combination of auxiliary basis functions [23]. This casts the four-index ERI tensor into a product of two- and three-index tensors, dramatically reducing the number of integrals and the required storage. The new rate-limiting steps become efficient, highly parallelizable matrix multiplications [23]. When combined with local correlation methods, DF leads to algorithms denoted by prefixes like "df-" (e.g., df-MP2) and "L" (e.g., LMP2), and their combination (df-LMP2) [1].

Key Methodologies and Implementation

The practical implementation of linear scaling and density fitting methods involves specific algorithms and workflows. The diagram below illustrates the core logical relationship between the fundamental principles and the resulting methodologies.

Density Matrix and Wannier Function Methods

A prominent class of linear scaling algorithms focuses on the direct optimization of the density matrix or the use of localized Wannier functions. The core workflow involves:

- Initialization: An initial guess for the density matrix or a set of localized orbitals is generated.

- Iterative Optimization: The total energy is minimized with respect to these localized quantities using techniques like unconstrained minimization or the method of Lagrange multipliers to enforce electron number conservation. Key algorithms include those by Li, Nunes, and Vanderbilt (density matrix) and by Ordejón, Artacho, and Soler (localized orbitals) [20].

- Sparse Algebra: Throughout the process, the sparsity of the density matrix or orbital coefficients in real space is exploited. Elements beyond a predetermined cutoff distance are neglected, and all matrix operations are performed using sparse linear algebra routines, which scale linearly with system size [20].

- Convergence: The self-consistent field procedure is iterated until the energy or density matrix converges within a specified threshold.

Integrated Density Fitting Workflow

Density fitting is integrated into the quantum chemistry computation as a preprocessing step for integral handling. The workflow for a typical mean-field theory computation (like Hartree-Fock) enhanced with DF is as follows:

- Auxiliary Basis Selection: A suitable auxiliary basis set is chosen for expanding the electron density.

- Integral Transformation: The four-index electron repulsion integrals (ERIs) are computed and factorized into two- and three-index tensors. For example, the ERI

(μν|λσ)is approximated as∑_P (μν|P) (J^{-1})_{PQ} (Q|λσ), whereμ, ν, λ, σare orbital basis functions,P, Qare auxiliary basis functions, andJis the Coulomb metric matrix [23]. - Modified Algorithm Steps: The steps of the underlying electronic structure method (e.g., building the Fock matrix in HF) are re-derived to use these low-rank tensors. This replaces the O(Nâ´) integral manipulation with a series of O(N³) or better matrix multiplications.

- Execution: The modified algorithm is executed, yielding the same final properties (energy, forces) as the conventional method but with a significantly reduced computational cost and memory footprint. As noted by Parrish et al., this enables routine computations on systems with "hundreds of atoms and thousands of basis functions" on modest workstations [23].

Application in Solid-State DFT Codes

In periodic plane-wave codes commonly used for materials screening, such as those used in high-throughput dielectric screening [21], linear scaling is achieved through a different but conceptually similar set of techniques:

- Orbital Localization: The Kohn-Sham orbitals are first localized in real space.

- Projection and Green's Function Methods: Algorithms then solve for the localized orbitals or the density matrix directly within a "localization region" for each orbital. Methods such as the finite-temperature projection algorithm by Goedecker and Colombo are examples of this approach [20].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Linear Scaling and Density Fitting Methodologies

| Method Category | Key References | Fundamental Principle | Typical System Suitability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density Matrix | Li, Nunes & Vanderbilt [20] | Direct minimization of the density matrix, exploiting its sparsity in real space. | Insulators and large-gap semiconductors. |

| Localized Orbitals | Ordejón, Artacho & Soler [20] | Use of localized Wannier-like functions as the fundamental computational unit. | Insulators, suitable for molecular and periodic systems. |

| Divide and Conquer | Yang [20] | Physical partitioning of the global system into smaller, manageable subsystems. | Very large systems, including biomolecules. |

| Density Fitting | Parrish [23] | Rank-reduction of the 4-index electron repulsion integral tensor. | All systems, universally applied to reduce integral cost. |

Practical Protocols for Materials Screening

The power of these computational efficiencies is realized in their application to large-scale materials screening. The following workflow diagram outlines a generalized protocol for ab initio screening of inorganic compounds, integrating the computational methods discussed.

Protocol for High-Throughput Dielectric Screening

This protocol, based on the work of Petousis et al. [21], details the steps for screening thousands of inorganic compounds for dielectric and optical properties.

- Candidate Structure Acquisition: Obtain crystal structures from a reliable database such as the Materials Project. The initial set in the cited study comprised over 1,000 inorganic compounds [21].

- Pre-Screening Filtering: Apply selection criteria to ensure computational feasibility and relevance. Petousis et al. used:

- Stability: Hull energy ≤ 50 meV/atom (or similar threshold) from the Materials Project.

- Band Gap: DFT band gap > 0.1 eV to focus on non-metals.

- Structural Quality: Interatomic forces in the starting structure < 0.05 eV/Ã… to ensure a well-relaxed geometry [21].

- DFPT Calculation with Efficiency Measures: Perform first-principles calculations using Density Functional Perturbation Theory (DFPT).

- Software: Use a code like VASP.

- Functional: Employ the GGA/PBE+U exchange-correlation functional.

- Efficiency: Leverage inherent efficiencies of DFPT and, where possible, integrated density fitting and localized basis sets to handle the large number of compounds.

- k-point density: Set to ~3,000 k-points per reciprocal atom.

- Plane-wave cut-off: Set to 600 eV [21].

- Post-Processing and Validation:

- Compute the static dielectric tensor, separating the ionic (

ε₀) and electronic (ε∞) contributions. - Estimate the polycrystalline dielectric constant (

ε_poly) by averaging the eigenvalues of the total dielectric tensor. - Calculate the refractive index (

n) asn = √(ε_poly∞). - Validate calculations by ensuring the dielectric tensor respects crystal symmetry and that acoustic phonon modes have near-zero energy at the Gamma point [21].

- Compute the static dielectric tensor, separating the ionic (

- Data Publication and Ranking: Integrate results into a public database (e.g., Materials Project) for querying. Rank candidates based on the target properties (e.g., very high or very low

ε_poly) for further investigation.

Protocol for Crystal Structure Prediction and Validation

This protocol, used for the ab initio discovery of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) [24], demonstrates the application of these methods to complex, previously unknown solids.

- Target Definition: Define the chemical composition of the target material, e.g., Cu(AIm)â‚‚ for a hypergolic copper-based zeolitic imidazolate framework (ZIF) [24].

- Structure Generation: Use a crystal structure prediction (CSP) algorithm like the ab initio random structure search (AIRSS), potentially combined with symmetry-enhancing methods like the Wyckoff Alignment of Molecules (WAM) procedure to reduce computational cost. Generate thousands of trial structures with varying unit cell parameters and atomic positions [24].

- Energy Minimization with Accurate DFT: Optimize all generated structures using periodic DFT.

- Software: Use a plane-wave code like CASTEP.

- Functional: Use the PBE functional with a many-body dispersion correction (MBD*).

- Efficiency: The WAM procedure, by enforcing symmetry, significantly reduces the number of unique degrees of freedom, acting as a form of system size reduction [24].

- Landscape Analysis and Ranking: Cluster the optimized structures to remove duplicates. Rank the unique structures by their calculated lattice energy to generate a crystal energy landscape. Analyze the low-energy structures for promising topology, density, and coordination geometry [24].

- Property Prediction and Experimental Targeting: Calculate relevant functional properties (e.g., volumetric energy density for hypergolic materials) from the predicted structures. Select the most promising candidates (e.g., the global minimum or low-energy polymorphs with desirable properties) as targets for synthesis [24].

- Experimental Validation: Synthesize the targeted compounds, as demonstrated by the perfect match between the predicted

dia-Cu(AIm)â‚‚structure and the experimentally synthesized material [24].

Applications in Inorganic Synthesis and Materials Discovery

The integration of efficient ab initio computations has fundamentally accelerated the cycle of materials discovery, from initial prediction to final synthesis.

Bridging the Gap Between Computation and Experiment

The most profound impact of these methods is their role in bridging the gap between high-throughput computation and slow, costly experimentation. The A-Lab provides a seminal example of this integration. This autonomous laboratory uses computations from the Materials Project and Google DeepMind to identify novel, air-stable inorganic targets [9]. For each target, it employs machine learning models, trained on text-mined historical literature, to propose initial solid-state synthesis recipes. When these recipes fail, an active learning cycle (ARROWS³) uses ab initio computed reaction energies from databases to propose new precursor combinations and reaction pathways, avoiding intermediates with low driving forces to form the target [9]. This closed-loop process, powered by the efficient data from large-scale computations, successfully synthesized 41 of 58 novel target compounds, demonstrating a potent synergy between computation and robotics.

Discovery of Functional Materials

Linear scaling and high-throughput screening have enabled the discovery of materials with tailored properties across multiple domains.

- Dielectric and Optical Materials: The screening of 1,056 compounds by Petousis et al. [21] created the largest database of its kind, identifying candidates for applications in electronics (e.g., DRAM, CPUs) where high-k dielectrics enable greater charge storage and low-k materials reduce cross-talk. The computed refractive indices also provide a direct guide for optical material design.

- Energy Materials: Large-scale screening of hypothetical MOFs for carbon capture has identified structures with exceptional low-pressure COâ‚‚ adsorption properties [22]. The use of ab initio-derived atomic charges (e.g., from the REPEAT method) is critical for accurately simulating adsorption performance in thousands of potential structures, guiding synthetic efforts toward the most promising targets.

- Specialized Functional Materials: CSP was used to discover novel copper(II)-based ZIFs predicted to be hypergolic fuels [24]. The computation accurately predicted the structure of

Cu(AIm)â‚‚and its high volumetric energy density (33.3 kJ cmâ»Â³) prior to its successful synthesis and validation, showcasing the predictive power of this approach for designing materials with specific, application-ready properties.

Table 2: Key Computational and Experimental Reagents for Accelerated Materials Discovery

| Category | Tool / Reagent | Function in Research | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Resources | Ab Initio Databases (e.g., Materials Project) | Provides pre-computed stability and property data for 100,000s of compounds, enabling rapid initial screening. | Screening for stable, novel dielectrics [21] and synthesis targets for A-Lab [9]. |

| Density Functional Perturbation Theory (DFPT) | Calculates response properties (dielectric tensor, phonon spectra) efficiently for large sets of compounds. | High-throughput dielectric constant screening [21]. | |

| Crystal Structure Prediction (CSP) | Predicts stable crystal structures from first principles for a given chemical composition, enabling discovery. | Prediction of novel hypergolic MOFs [24]. | |

| Experimental Resources | Autonomous Laboratory (A-Lab) | Integrates robotics with AI to execute and interpret synthesis experiments 24/7, validating computations. | Synthesis of 41 novel inorganic compounds [9]. |

| Precursor Powders | Raw materials for solid-state synthesis of inorganic powders. | Used by A-Lab's robotic preparation station [9]. | |

| X-ray Diffraction (XRD) | The primary characterization technique for identifying crystalline phases and quantifying yield in synthesis. | Used by A-Lab for automated phase analysis [9]. |

Linear scaling approaches and density fitting techniques have evolved from theoretical concepts into indispensable tools for computational materials science. By directly addressing the O(N³) bottleneck of conventional quantum chemistry methods, they have unlocked the potential for true large-scale, ab initio screening of inorganic compounds. Their integration into high-throughput workflows, as exemplified by the massive screening for dielectrics and the predictive discovery of MOFs, has dramatically accelerated the identification of promising functional materials. Furthermore, the successful coupling of these computational predictions with autonomous experimental platforms like the A-Lab represents a paradigm shift in materials research. This synergy creates a virtuous cycle where computations guide experiments, and experimental data refines computational models, thereby closing the gap between prediction and synthesis. As these efficient algorithms continue to develop and computational resources grow, their role in the targeted design and discovery of next-generation inorganic materials will only become more central and transformative.

Practical Applications: Implementing Ab Initio Methods for Property Prediction and Screening

Density Functional Theory (DFT) for Predicting Electronic and Structural Properties

Density Functional Theory (DFT) represents a computational quantum mechanical modelling method widely used in physics, chemistry, and materials science to investigate the electronic structure of many-body systems, particularly atoms, molecules, and condensed phases [7]. This approach determines properties of many-electron systems using functionals—functions that accept another function as input and output a single real number—specifically functionals of the spatially dependent electron density [7]. Within the context of ab initio computations for inorganic synthesis target screening, DFT provides a critical bridge between predicted material properties and experimental synthesis planning, enabling researchers to prioritize promising candidate materials before embarking on resource-intensive laboratory synthesis.

The theoretical foundation of DFT rests on the pioneering work of Hohenberg and Kohn, which established two fundamental theorems [7]. The first Hohenberg-Kohn theorem demonstrates that the ground-state properties of a many-electron system are uniquely determined by its electron density, a function of only three spatial coordinates. This revolutionary insight reduced the many-body problem of N electrons with 3N spatial coordinates to a problem dependent on just three coordinates through density functionals [7]. The second Hohenberg-Kohn theorem defines an energy functional for the system and proves that the correct ground-state electron density minimizes this energy functional. These theorems were further developed by Kohn and Sham to produce Kohn-Sham DFT (KS DFT), which reduces the intractable many-body problem of interacting electrons to a tractable problem of noninteracting electrons moving in an effective potential [7].

The Kohn-Sham equations form the practical basis for most DFT calculations and are expressed as a set of single-electron Schrödinger-like equations [7]:

[ \hat{H}^{\text{KS}} \psii(\mathbf{r}) = \left[ -\frac{\hbar^2}{2m} \nabla^2 + V{\text{eff}}(\mathbf{r}) \right] \psii(\mathbf{r}) = \epsiloni \psi_i(\mathbf{r}) ]

where ( \psii(\mathbf{r}) ) are the Kohn-Sham orbitals, ( \epsiloni ) are the corresponding eigenvalues, and ( V_{\text{eff}}(\mathbf{r}) ) is the effective potential. This potential is defined as:

[ V{\text{eff}}(\mathbf{r}) = V{\text{ext}}(\mathbf{r}) + \int \frac{n(\mathbf{r}')}{|\mathbf{r}-\mathbf{r}'|} d\mathbf{r}' + V_{\text{XC}}(\mathbf{r}) ]

where ( V{\text{ext}}(\mathbf{r}) ) is the external potential, the second term is the Hartree potential describing electron-electron repulsion, and ( V{\text{XC}}(\mathbf{r}) ) is the exchange-correlation potential that encompasses all non-trivial many-body effects [7].

Computational Methodology and Exchange-Correlation Functionals

DFT Practical Workflow

The standard DFT computational workflow begins with specifying the atomic structure and positions, followed by constructing the Kohn-Sham equations with an initial guess for the electron density. These equations are then solved self-consistently: the Kohn-Sham orbitals are used to compute a new electron density, which updates the effective potential, iterating until convergence is achieved in both the density and total energy [7]. From the converged results, various material properties—including structural, electronic, mechanical, and thermal characteristics—can be derived.

A critical consideration in this process is the treatment of the exchange-correlation functional (( E{\text{XC}}[n] ) and its potential ( V{\text{XC}}[n] )), which remains unknown and must be approximated [7]. The accuracy of DFT calculations depends almost entirely on the quality of this approximation, leading to the development of numerous functionals with varying computational costs and applicability.

Hierarchy of Exchange-Correlation Functionals

Table: Common Types of Exchange-Correlation Functionals in DFT

| Functional Type | Description | Key Features | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local Density Approximation (LDA) | Based on the uniform electron gas model; depends locally on density ( n(\mathbf{r}) ) [7]. | Computationally efficient; good for metallic systems with slowly varying densities. | Tends to overbind, resulting in underestimated lattice parameters and overestimated binding energies. |

| Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) | Extends LDA by including the density gradient ( \nabla n(\mathbf{r}) ); examples include PBE [25]. | Improved lattice parameters and energies compared to LDA; widely used in materials science. | Can struggle with dispersion forces and strongly correlated systems. |

| Meta-GGA | Incorporates additional ingredients like the kinetic energy density. | Better accuracy for diverse properties without significant computational cost increase. | Implementation can be more complex than GGA. |

| Hybrid Functionals | Mixes Hartree-Fock exchange with DFT exchange-correlation; e.g., B3LYP [26]. | Improved band gaps and reaction energies; popular in quantum chemistry. | Computationally expensive due to exact exchange requirement. |

| DFT+U | Adds Hubbard parameter to treat strongly correlated electrons. | Better description of localized d and f electrons. | Requires empirical parameter U. |

| Van der Waals Functionals | Specifically designed to include dispersion interactions. | Captures weak interactions crucial for molecular crystals and layered materials. | Can be empirically parameterized. |

For inorganic solid-state materials, GGAs like the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional have proven particularly effective for predicting structural and mechanical properties [25]. In high-throughput screening for inorganic synthesis, the selection of an appropriate functional involves balancing computational efficiency with the required accuracy for target properties.

Case Study: DFT Analysis of MAX-Phase Cr₃AlC₂

Structural and Electronic Properties

The application of DFT to predict properties of the MAX-phase material Cr₃AlC₂ demonstrates the methodology's practical utility in inorganic materials research. This compound adopts a hexagonal crystal structure with space group P6₃/mmc, and DFT calculations accurately determine its lattice parameters through total energy minimization [25]. The refined lattice parameters at 0 GPa pressure are a = 2.8699 Å and c = 17.3922 Å, showing excellent agreement (within 0.69%) with theoretical references [25].

Electronic structure analysis reveals Cr₃AlC₂'s metallic character, evidenced by the overlap of conduction and valence bands at the Fermi energy level (EF) [25]. The density of states (DOS) decompositions shows the valence band divided into two primary sub-bands: the lower valence band (-15.0 to -10 eV) dominated by C-s states with minor contributions from Cr-s and Cr-p states, and the upper valence band (-10 to 0.0 eV) characterized by significant hybridization between Cr-d and C-p states [25]. Charge density mapping further illuminates bonding characteristics, indicating stronger Cr-C bonds compared to Al-C bonds, with applied pressure enhancing charge density at specific locations and strengthening Cr-C bonding [25].

Mechanical and Thermal Properties

DFT predictions of elastic constants (( C{ij} )) provide crucial insights into mechanical stability and behavior. For Cr₃AlC₂, the calculated elastic constants at 0 GPa satisfy the Born criteria for mechanical stability: ( C{44} > 0 ); ( C{11} + C{12} - 2C{13}^2/C{33} > 0 ); and ( C{11} - C{12} > 0 ) [25]. These calculations validate the compound's mechanical stability across various pressures.

Table: DFT-Predicted Mechanical Properties of Cr₃AlC₂ at Different Pressures [25]

| Pressure (GPa) | Bulk Modulus, B (GPa) | Shear Modulus, G (GPa) | Young's Modulus, E (GPa) | Pugh's Ratio (B/G) | Poisson's Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 207.0 | 118.6 | 298.8 | 1.75 | 0.260 |

| 10 | 242.1 | 137.0 | 345.8 | 1.77 | 0.262 |

| 20 | 274.6 | 149.8 | 380.3 | 1.83 | 0.269 |

| 30 | 305.8 | 160.2 | 409.2 | 1.91 | 0.277 |

| 40 | 338.0 | 170.3 | 437.5 | 1.98 | 0.284 |

| 50 | 365.2 | 178.6 | 460.8 | 2.04 | 0.290 |

Pugh's ratio (B/G) and Poisson's ratio values indicate that Cr₃AlC₂ exhibits ductile behavior across all pressure ranges studied, with increasing pressure further enhancing ductility [25]. Beyond mechanical properties, DFT enables prediction of thermal characteristics including the Grüneisen parameter, Debye temperature, thermal conductivity, melting point, heat capacity, and vibrational properties via phonon dispersion spectra, which confirm dynamic stability [25].

DFT Computational Workflow

Integration with Inorganic Synthesis Screening

The predictive power of DFT becomes particularly valuable when integrated with inorganic synthesis screening pipelines. While high-throughput computations have accelerated materials discovery, the development of synthesis routes represents a significant innovation bottleneck [27]. Bridging this gap requires combining DFT-predicted material properties with synthesis knowledge extracted from experimental literature.

Recent advances in text mining and natural language processing (NLP) have enabled the creation of structured databases from unstructured synthesis literature. One such dataset automatically extracted 19,488 synthesis entries from 53,538 solid-state synthesis paragraphs, containing information about target materials, starting compounds, operations, conditions, and balanced chemical equations [27]. This synthesis database provides a critical resource for linking DFT-predicted materials with potential synthesis pathways.

For inorganic synthesis target screening, the integrated workflow involves:

- Using DFT to predict stability and properties of hypothetical compounds

- Screening for desired functional characteristics

- Matching promising candidates with similar compounds in synthesis databases

- Proposing feasible synthesis routes based on analogous preparations

- Experimental validation of predictions

This approach is particularly valuable for identifying novel materials within known families, such as MAX-phase compounds, where DFT can accurately predict stability and properties before synthesis is attempted [25].

Advanced Techniques and Machine Learning Advances

Machine Learning Accelerated DFT

Traditional DFT calculations scale cubically with system size (~N³), limiting routine applications to systems of a few hundred atoms [28]. Recent machine learning (ML) approaches circumvent this limitation by learning the mapping between atomic environments and electronic structure properties. The Materials Learning Algorithms (MALA) package implements one such framework, using bispectrum coefficients as descriptors that encode atomic positions relative to points in real space, and neural networks to predict the local density of states (LDOS) [28].